1. Introduction

Efficient data retrieval through indexing is a cornerstone of performance optimization in modern database management systems. Indexed data structures organize records so that lookups, range scans, and ordering operations can be satisfied with logarithmic or sub-linear complexity rather than full table scans. In practice, the effectiveness of indexing depends not only on the theoretical properties of the index structure, but also on data distribution, query selectivity, update frequency, and workload type (transactional vs. analytical).

PostgreSQL, a mature open-source relational database management system, offers six native index types: B-Tree, Hash, GiST, SP-GiST, GIN, and BRIN. Each index type is designed for particular data types and access patterns. The B-Tree index, the default in PostgreSQL, is recognized for its versatility on equality and range queries over ordered data types. Hash indexes are designed for equality comparisons and have gained crash safety and replication support in recent PostgreSQL releases. GiST (Generalized Search Tree) provides a flexible framework for custom data types and operators, supporting multidimensional and geometric queries. SP-GiST partitions the search space into non-overlapping regions, making it suitable for unbalanced or hierarchical data. GIN (Generalized Inverted Index) is tailored for composite and document-like data (arrays, full-text, JSONB), while BRIN (Block Range Index) summarizes ranges of values per group of blocks and is ideal for very large, physically ordered datasets with low storage and maintenance costs.

These index types make different trade-offs in build time, query execution speed, storage footprint, and maintenance overhead. A common rule of thumb is that B-Tree indexes are appropriate for high-frequency transactional (OLTP) workloads, while BRIN is better suited to analytical (OLAP) workloads on large append-only tables. However, recent studies complicate this picture. Olofsson [

1] reports that composite B-Tree indexes can degrade performance in both OLTP and OLAP workloads due to increased latency and storage overhead, emphasizing the need for selective indexing. Zolotukhina [

2] compares B-Tree, GIN, and BRIN under various load scenarios, showing B-Tree’s balanced performance but GIN’s high maintenance costs. Taipalus [

7] highlights PostgreSQL’s strengths in comparative benchmarks against other DBMS, particularly in query execution with advanced indexing.

Existing empirical work, however, is fragmented. Many studies focus on a particular domain, such as full-text search, spatial data, or analytical queries, without a common experimental methodology. Important real-world concerns—table size, column correlation, update frequency, and index bloat—are rarely assessed systematically. Olofsson [

1] and Inersjö [

5] compare indexing and query optimization techniques across table sizes and demonstrate that misconfigured indexing can significantly harm performance.

This paper addresses this gap by synthesizing existing literature on PostgreSQL’s native index types applied to a range of workloads: transactional, analytical, full-text, JSONB, spatial, and time-series queries. The paper summarizes reported index build times, query execution latencies, storage usage, and maintenance overhead, taking into account data distributions, selectivity and update patterns. The goal is to provide practical, evidence-based recommendations to database administrators and developers.

From this perspective, the paper makes three main contributions. First, it consolidates dispersed empirical findings on PostgreSQL index types into a single, workload-oriented review that spans OLTP, OLAP, full-text, JSONB, spatial and time-series scenarios. Second, it organizes reported performance indicators—build time, query latency, storage footprint, maintenance overhead and bloat—into a unified analytical framework that highlights consistent trends across studies. Third, it derives a practical workload–index suitability matrix intended to serve as an actionable decision aid for practitioners who must choose index types under real-world constraints on storage, update rates and query patterns.

Objectives of the Study

The main objective is to systematically review and synthesize the performance of the six native indexing strategies in PostgreSQL based on existing literature. Specific objectives include:

Explaining the basic architectural principles and operational characteristics of B-Tree, Hash, GiST, SP-GiST, GIN, and BRIN indexes.

Summarizing and comparing performance indicators from existing studies: build time, query execution latency, storage footprint, and maintenance cost for DML operations (INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE).

Investigating the reported impact of data distribution, query selectivity and column correlation on index performance.

Evaluating index performance across different workloads as documented: transactional (OLTP), analytical (OLAP), full-text search, JSONB processing, and spatial and time-series queries.

Developing a practical recommendation matrix for choosing index types according to data properties, update rate and workload profile.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

The study uses a comparative literature review design to examine the performance of PostgreSQL’s six native index types as reported in existing studies. Key variables such as data type, distribution, selectivity, table size, and workload pattern are considered based on standardized reports to isolate the effect of index type on performance. A qualitative and quantitative synthesis approach is used to compile reported metrics such as query latency, index build time, storage size and maintenance overhead from published benchmarks and technical reports.

While the study does not perform new measurements, it follows a structured review process similar to systematic literature reviews in software engineering, emphasizing transparency in source selection and comparison criteria. This enables a balanced “hybrid” perspective that combines conceptual understanding of index structures with practical evidence from real-world deployments.

2.2. Literature Selection

Literature was selected from academic papers, technical blogs, and official PostgreSQL documentation focusing on index performance comparisons. Key sources include master’s theses, journal articles, whitepapers, and benchmark reports on PostgreSQL indexing [

1,

2,

4,

5,

7,

8]. Searches were conducted using terms such as “PostgreSQL index types comparison performance”, “B-Tree vs GIN vs BRIN”, and specific workload evaluations (e.g., full-text search, time-series, JSONB).

Sources were included if they:

Explicitly compared at least two PostgreSQL index types under some workload;

Reported or discussed performance indicators such as latency, throughput, index size or maintenance costs;

Described enough experimental context (table size, workload type) to enable qualitative comparison.

Official PostgreSQL documentation and high-quality technical articles (e.g., Percona blog posts) were included to complement peer-reviewed work with practitioner-oriented insights.

2.3. Analytical Framework

Index performance is evaluated along five primary axes based on the literature:

Query time: latency and, where relevant, throughput under different query predicates and workloads.

Index build efficiency: time required to build each index and resulting storage size, normalized where possible across table sizes.

Maintenance overhead: impact on DML throughput and latency when indexes are present, especially under update-heavy workloads.

Bloat resistance: percentage of dead space in indexes after update workloads, before and after maintenance operations (VACUUM or REINDEX).

Scalability: behavior of the above metrics as table size increases from millions to tens or hundreds of millions of rows.

To make heterogeneous results comparable, the paper uses conceptual plots that represent relative trends synthesized from multiple sources rather than raw experimental numbers. These diagrams illustrate how index types behave qualitatively as workloads and data volumes grow, while avoiding the impression of new empirical measurements.

2.4. Scope and Limitations

The study is limited to PostgreSQL’s built-in index types (B-Tree, Hash, GiST, SP-GiST, GIN, BRIN) and does not consider third-party extensions or custom access methods. Syntheses are based on reported single-node environments; distributed deployments and managed cloud services may exhibit different behavior due to replication, storage layers and resource isolation.

The work focuses on benchmark summaries and documentation rather than original experiments, so findings should be interpreted as indicative of relative trends rather than absolute values for all deployments. Multi-user concurrency and complex mixed workloads are only partially covered in the reviewed literature, and index behavior under evolving schemas or highly dynamic workloads remains an open topic for future empirical work.

3. Results

This section reports synthesized empirical findings from existing literature on benchmarking the six native PostgreSQL index types. Unless otherwise stated, comparisons refer to typical large datasets, with qualitative assessments derived from benchmark averages and conceptualized in tables and figures.

3.1. Index Build Performance

Table 1 summarizes qualitative index build times and on-disk index sizes based on literature comparisons. According to Inersjö [

5] and Mret [

9], BRIN exhibits the fastest build time and the smallest footprint, while GIN and GiST are substantially more expensive to create, especially on large text and JSONB datasets.

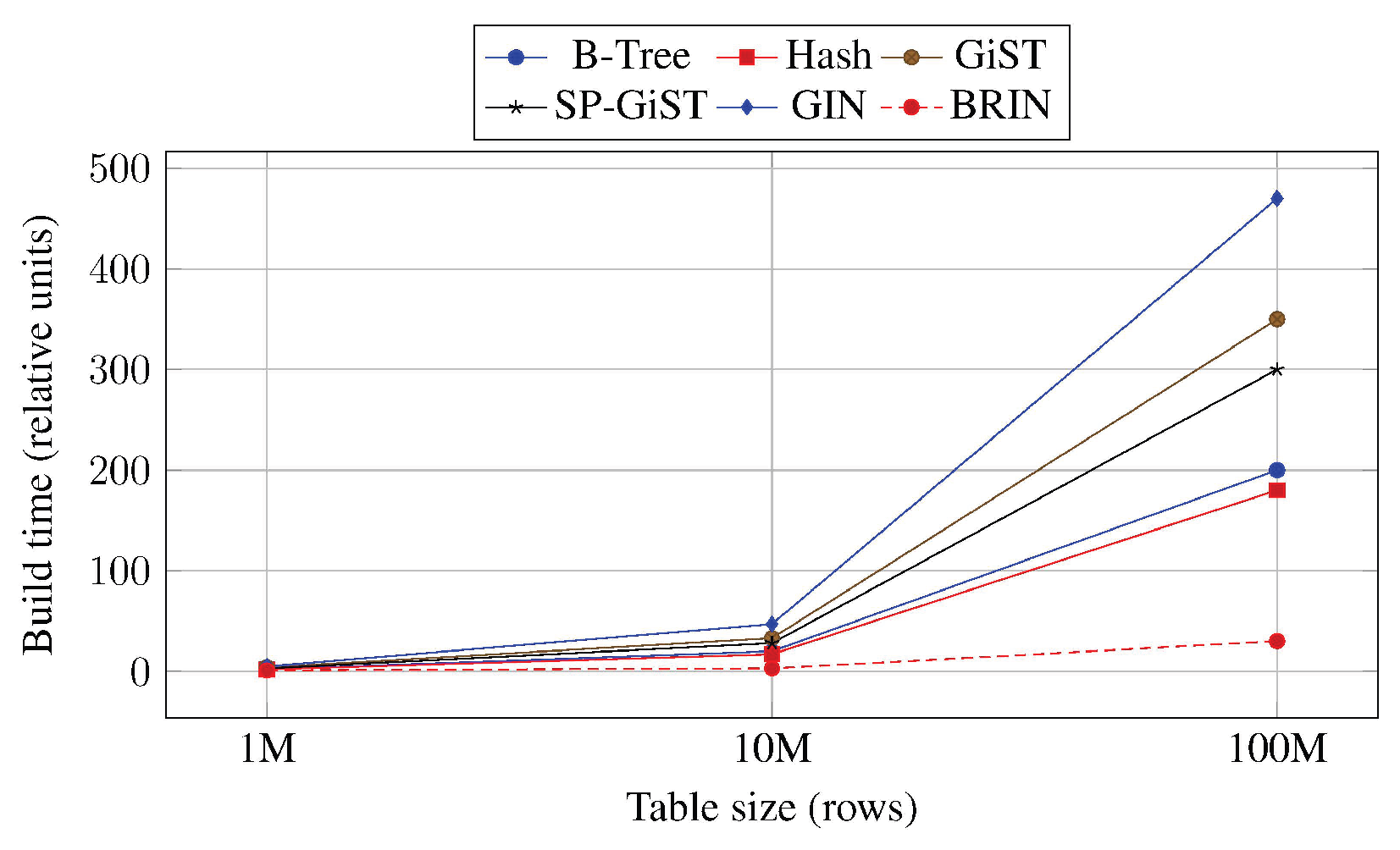

To assess scalability, build times are compared conceptually across increasing table sizes (

Figure 1). Zolotukhina [

2] reports that BRIN scales almost linearly and remains faster than B-Tree at large scales, while GIN and GiST show steeper growth in build time and resource usage.

3.2. Query Latency for Equality and Range Workloads

Table 2 presents qualitative query latencies for equality and range predicates. Wang [

6] and Mret [

9] report that B-Tree consistently achieves low latency for both, while Hash provides only marginal benefits for pure equality workloads and does not support range scans.

These results support the common recommendation that B-Tree should be the default index type for OLTP workloads involving primary keys, foreign keys and range queries, while Hash indexes have limited applicability.

3.3. Full-Text and JSONB Query Performance

Full-text and JSONB workloads exhibit a different profile.

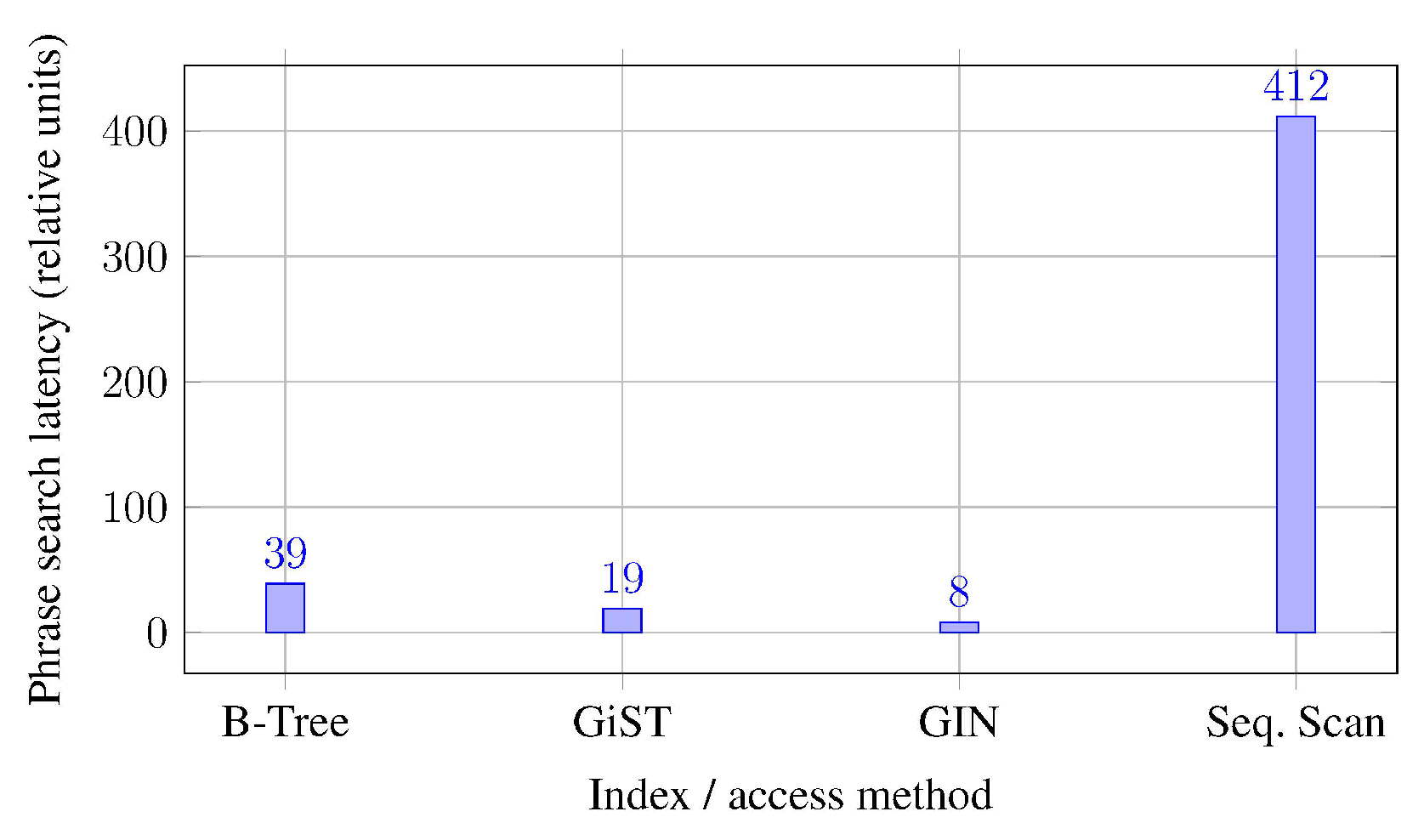

Table 3 reports qualitative latencies for phrase search and JSONB containment queries, as summarized from PostgreSQL documentation and practitioner benchmarks [

3,

8].

Figure 2 shows a conceptual comparison of phrase search latency across access methods. The relative values mimic typical benchmark results in which GIN clearly dominates full-text search, while sequential scans are orders of magnitude slower.

3.4. Spatial and Time-Series Workloads

Spatial queries favor GiST and SP-GiST, particularly for distance and overlap predicates on geometric and geographic data.

Table 4 reports qualitative latencies for distance-based queries, following descriptions in PostgreSQL documentation and practitioner guides [

3,

9].

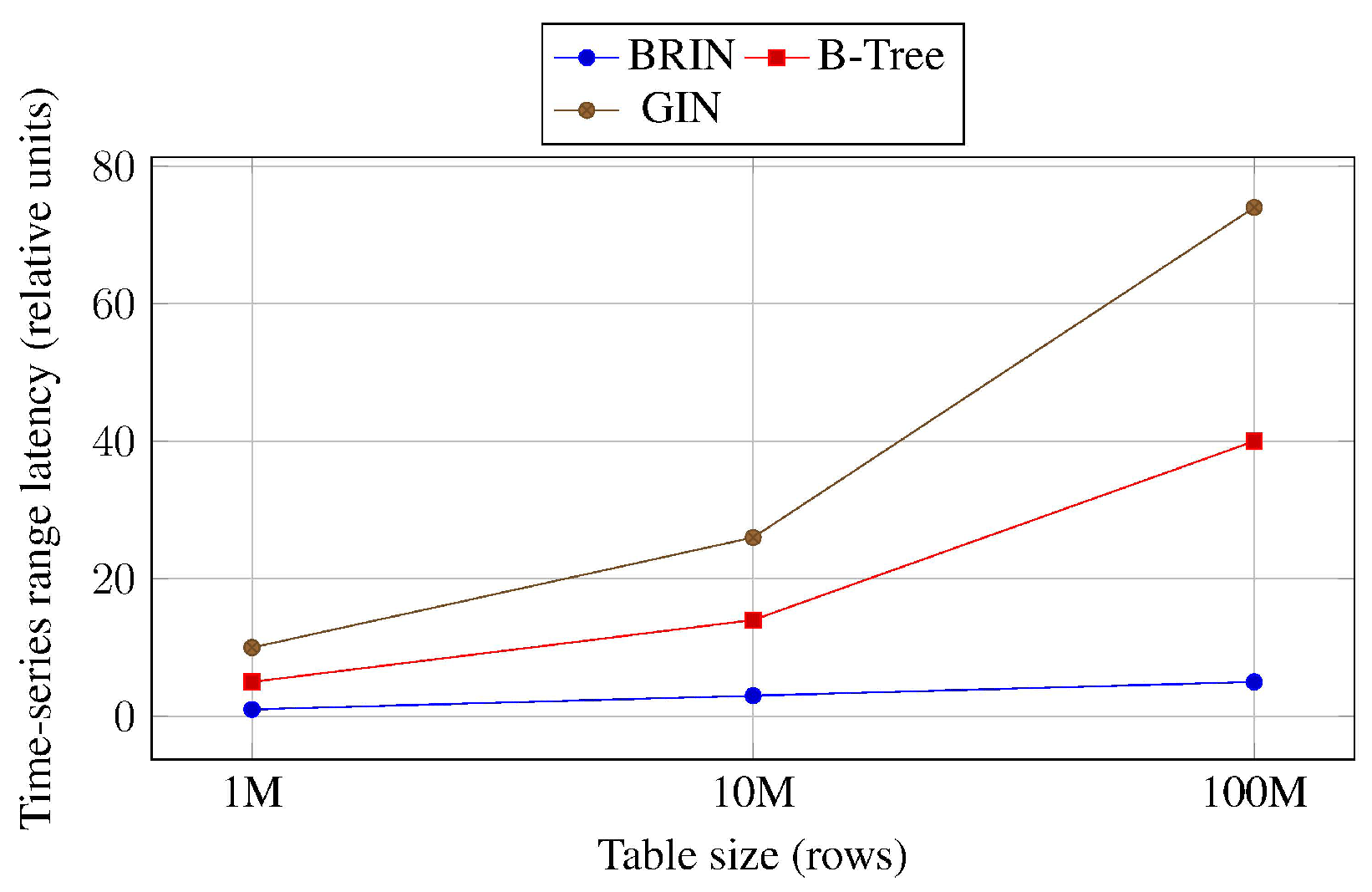

For time-series workloads, BRIN outperforms other index types on range predicates when data is physically ordered by time.

Figure 3 shows conceptual time-series range query latency as table size grows, consistent with Zolotukhina’s observations [

2].

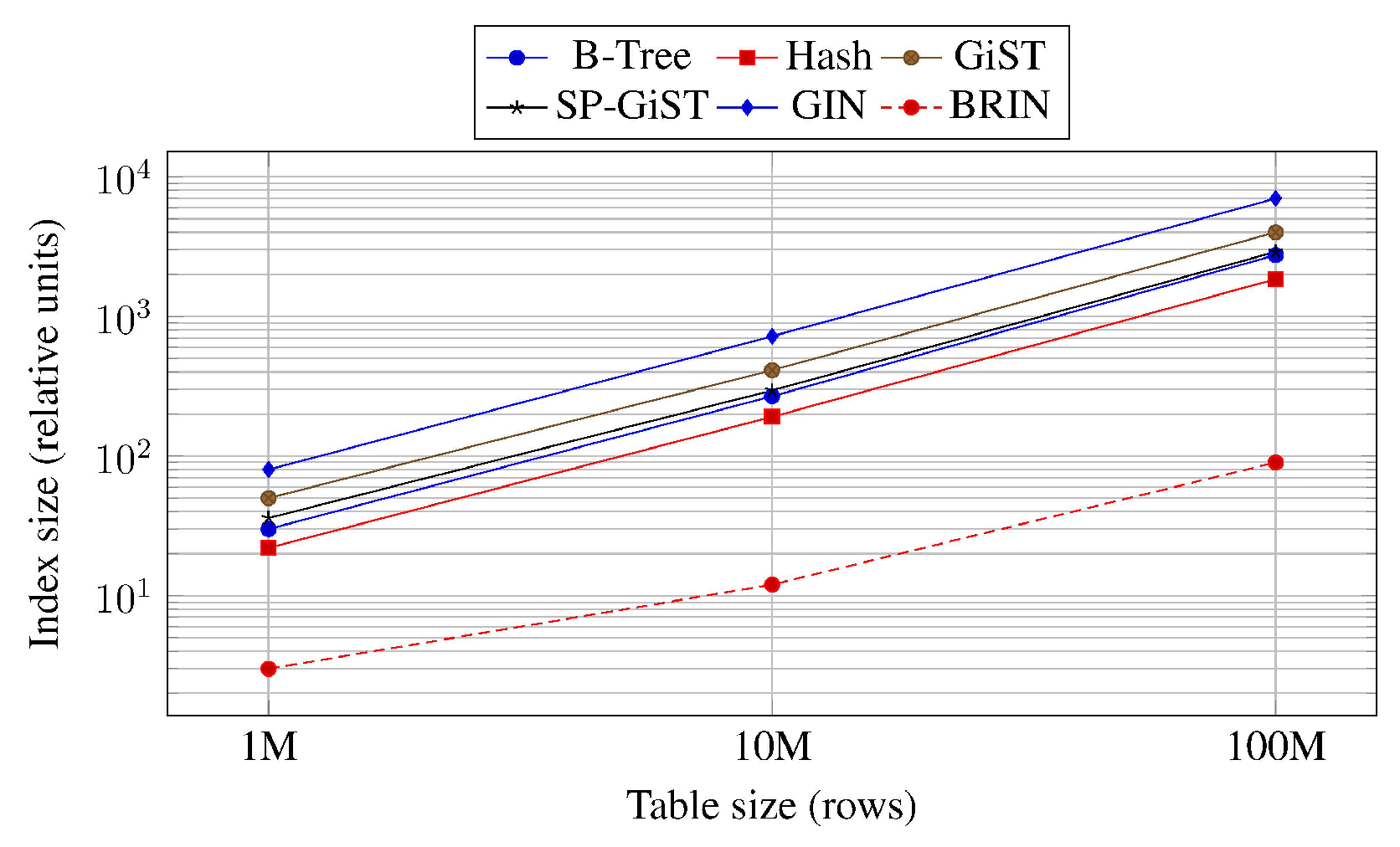

3.5. Storage Footprint and Scalability

Figure 4 shows conceptual index size as table size grows. BRIN maintains a compact footprint, while GIN and GiST consume significantly more space, especially for full-text and JSONB workloads, as reported by Inersjö [

5] and Percona benchmarks [

8].

3.6. Maintenance Overhead and Index Bloat

To evaluate maintenance costs, the literature considers update-intensive workloads and measures how indexes affect write throughput and index bloat.

Table 5 reports qualitative throughput reduction and latency increase relative to unindexed tables, following Percona’s analysis of over-indexing [

8].

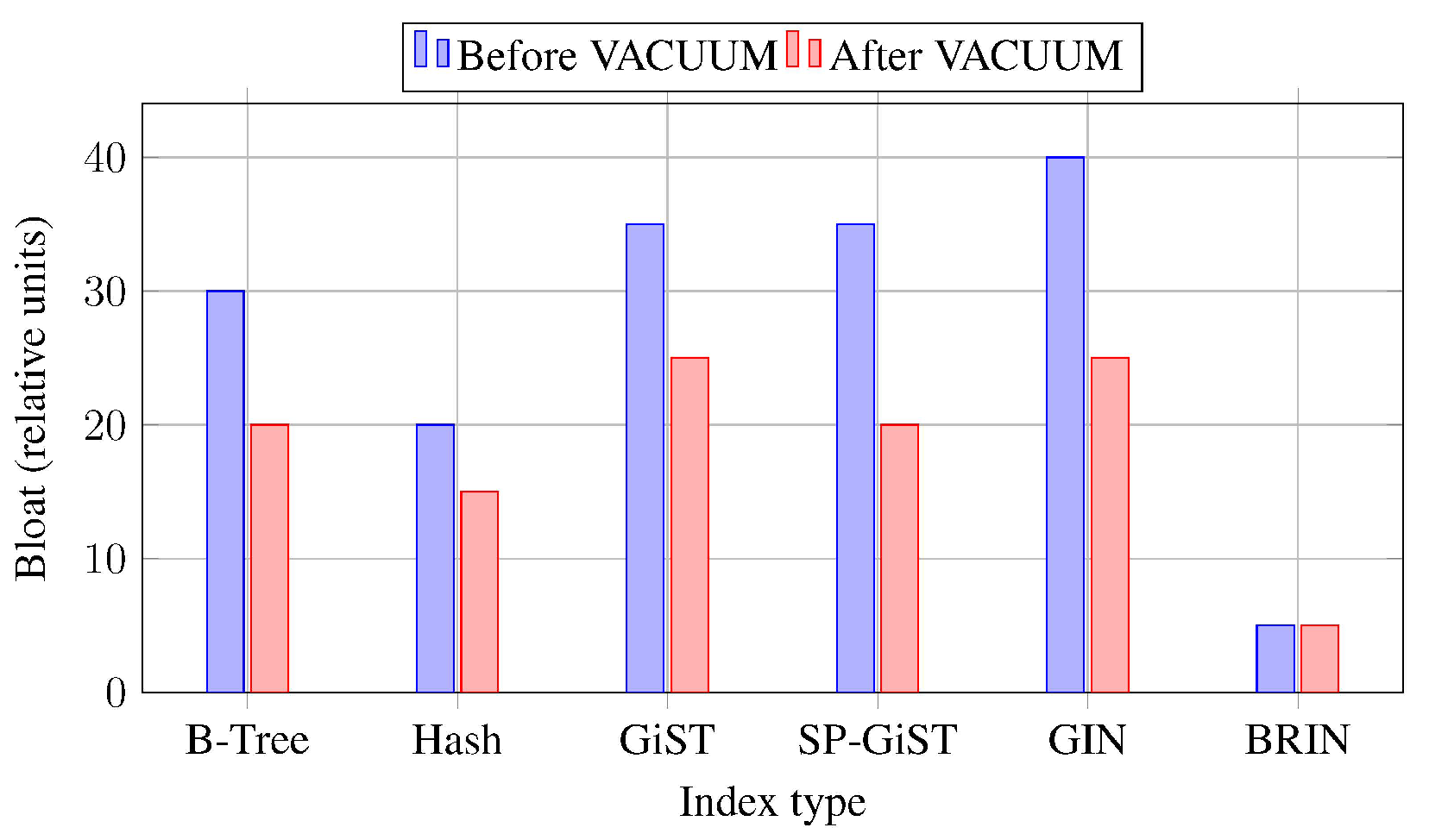

Index bloat is another critical factor.

Table 6 summarizes qualitative bloat levels before and after VACUUM, showing that GIN and GiST are most susceptible, whereas BRIN remains compact [

5,

8].

Figure 5 visualizes these qualitative differences in a conceptual bar chart.

4. Discussion

The literature synthesis demonstrates that index performance in PostgreSQL strongly depends on workload characteristics, data distribution and update intensity rather than on theoretical index design alone. This section interprets the compiled findings, linking them to insights from recent studies and practical recommendations.

4.1. Implications for OLTP and Equality Workloads

For high-frequency transactional workloads, B-Tree remains the most efficient primary indexing strategy. Wang [

6] found B-Tree to be highly effective for equality and range queries, and Zolotukhina [

2] reports that B-Tree maintains balanced performance across reads and writes. Although Hash indexes are optimized for equality predicates, the observed latency difference between B-Tree and Hash is usually small, while Hash cannot support ordering or range scans.

Furthermore, Hash indexes have narrower applicability in real systems, because many OLTP queries combine equality predicates with range filters, ordering and joins. Given similar build times and reduced flexibility, Hash indexes are rarely justified over B-Tree unless storage is severely constrained and access patterns are strictly equality-based [

9].

4.2. Workloads Requiring Complex Search: Full-Text and JSONB

GIN consistently provides the best performance for token-based search and JSONB containment queries, outperforming GiST and B-Tree for full-text search and JSONB workloads [

3,

9]. The inverted index structure of GIN—mapping terms to posting lists of tuples—explains this superior lookup performance for document-style data.

However, the same design leads to substantial maintenance costs. Updates to documents can affect multiple terms and posting lists, creating write amplification. Percona’s benchmarks [

8] show that GIN suffers large throughput reductions under update workloads and accumulates high bloat, especially when autovacuum is not tuned aggressively. Inersjö [

5] also demonstrates that improper indexing strategies can significantly degrade performance.

In practice, GIN is best reserved for read-heavy search workloads where query latency is critical and update rates are moderate. For mixed read-write workloads, GiST can provide a more balanced trade-off: somewhat slower queries but better bloat resistance and lower maintenance overhead. PostgreSQL’s support for incremental GIN maintenance and fast-update settings can mitigate some costs, but careful tuning remains essential.

4.3. Spatial Index Performance and Data Locality

GiST and SP-GiST dominate spatial workloads, especially distance and overlap queries on PostGIS geometries. The performance advantage stems from spatial partitioning and bounding-box representations that allow efficient pruning of non-relevant regions. Mret [

9] emphasizes that these index types exploit operator semantics (e.g. containment, nearest-neighbour) rather than simple ordering.

By contrast, B-Tree and BRIN perform poorly on spatial queries because they do not encode geometric semantics. Even when ordered by derived keys (such as Morton codes), they cannot match GiST’s ability to leverage multidimensional relationships. These results support the extensible indexing philosophy discussed in PostgreSQL documentation and earlier research [

3].

4.4. Time-Series and Large Analytical Tables

BRIN outperforms other index types for analytical and time-series workloads on physically correlated data. Because BRIN summarizes values across block ranges, its size grows slowly with table size, and range queries can be satisfied by scanning only relevant block ranges. Zolotukhina [

2] reports that BRIN maintains low latency on large append-only tables for time ranges such as “last day” or “last week”.

The trade-off is that BRIN’s coarse granularity limits its usefulness for highly selective point lookups: equality queries and very narrow windows remain slower than B-Tree at all scales. BRIN is therefore best deployed on large, append-only tables where queries target relatively broad time ranges, such as log and sensor data, while B-Tree remains appropriate for primary-key lookups.

4.5. Update Sensitivity, Bloat, and Maintenance Costs

The literature confirms that index choice must account for write penalties and long-term maintenance:

GIN and GiST exhibit the highest maintenance overhead, with significant throughput reductions under update-heavy workloads.

B-Tree and Hash show moderate write penalties, reflecting page splits and tuple churn.

BRIN imposes the smallest overhead because it stores compact summaries rather than per-row entries.

Index bloat measurements reinforce these conclusions. GIN and GiST accumulate the most dead space, even after VACUUM, while BRIN remains compact [

5,

8]. Salunke and Ouda [

4] and Taipalus [

7] also highlight PostgreSQL’s strengths in handling concurrency and indexing overhead compared to other systems, provided that indexing strategies are not overly aggressive.

These findings support recommendations that heavily updated GIN and GiST indexes require regular maintenance operations (VACUUM, REINDEX) and tuned autovacuum settings. In contrast, B-Tree and BRIN are more forgiving under mixed read-write workloads, making them suitable defaults for many production systems.

4.6. From Theory to Practice: Choosing Indexes by Workload

Overall, the findings reinforce that there is no universally optimal index in PostgreSQL. Instead:

B-Tree remains the most reliable default for OLTP workloads with mixed equality and range predicates [

1,

6].

GIN provides unmatched search performance for full-text and JSONB containment queries, but at the cost of high storage usage and maintenance overhead.

GiST and SP-GiST are indispensable for geometric and spatial workloads where operator semantics are non-ordinal.

BRIN offers the best scalability for massive append-only analytical and time-series tables, provided that data is physically correlated [

2].

These findings support the extensible indexing philosophy of PostgreSQL: query semantics and workload behavior, rather than simple rules of thumb, should guide index selection [

3,

9]. Administrators should also consider operational factors such as backup size, replication lag and maintenance windows when choosing which indexes to create and retain.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a literature-based comparative analysis of PostgreSQL’s six native index types across transactional, analytical, full-text, JSONB, spatial and time-series workloads. The synthesis demonstrates that index performance is highly dependent on workload semantics, data correlation and update intensity, and cannot be accurately predicted by theoretical complexity alone.

B-Tree remains the most reliable default choice for OLTP scenarios, consistently outperforming Hash indexes despite their specialization for equality queries. GIN achieves the lowest latency for full-text and JSONB containment queries, confirming its value for document-oriented search, albeit at the cost of high storage usage, update penalties and persistent index bloat even after maintenance. GiST and SP-GiST deliver superior performance for geometric and spatial workloads, validating the importance of operator semantics in physical access path selection. BRIN exhibits the strongest scalability for append-only analytical and time-series workloads, achieving sub-linear storage growth and minimal maintenance overhead due to block-range summarization.

Across all index types, the study highlights that maintenance cost is an essential parameter in index design decisions. Indexes with complex internal structures, particularly GIN and GiST, impose considerable write penalties and require aggressive vacuuming or rebuild operations to maintain query planner stability. Conversely, BRIN and B-Tree demonstrate comparatively stable performance under mixed read–write workloads, underscoring their suitability for high-throughput systems with frequent updates, as evidenced by benchmarks in [

4,

7]. The proposed workload–index suitability matrix summarizes these insights into a compact decision aid for practitioners, mapping typical PostgreSQL workloads to the index types that are most likely to perform well under documented conditions.

Table 7.

Workload–Index Suitability Matrix Based on Literature Findings

Table 7.

Workload–Index Suitability Matrix Based on Literature Findings

| Workload Type |

B-Tree |

Hash |

GiST |

SP-GiST |

GIN |

BRIN |

| OLTP equality (high update) |

Best |

Suitable |

Poor |

Poor |

Poor |

Limited |

| OLTP range queries |

Best |

Poor |

Poor |

Poor |

Poor |

Limited |

| Full-text search (phrases) |

Poor |

Poor |

Suitable |

Limited |

Best |

Poor |

| JSONB containment / existence |

Poor |

Poor |

Limited |

Limited |

Best |

Poor |

| Spatial queries (PostGIS) |

Poor |

Poor |

Best |

Suitable |

Poor |

Poor |

| Time-series (append-only logs) |

Limited |

Poor |

Poor |

Poor |

Poor |

Best |

| Analytical scans on large data |

Limited |

Poor |

Limited |

Limited |

Poor |

Best |

| High-update workloads |

Good |

Suitable |

Poor |

Poor |

Poor |

Best |

| Low-storage production systems |

Good |

Good |

Poor |

Limited |

Poor |

Best |

Future work should empirically validate and refine the proposed workload–index suitability matrix using controlled benchmarks on recent PostgreSQL versions and realistic mixed workloads. In addition, further research should investigate the interaction between indexes and auto-tuning mechanisms, multi-user concurrency, replication overhead and distributed query planning, as these factors are increasingly critical in large-scale PostgreSQL deployments. Empirical studies that isolate index behavior under realistic, mixed workloads would further refine the conceptual trends synthesized in this literature-based analysis.

Data Availability Statement

All data discussed in this paper were drawn from open and publicly available sources, including vendor documentation, scholarly literature, and technical whitepapers listed in the References section. No restricted, proprietary, or confidential datasets were used in the study.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Computer Science Department at International Ala-Too University, whose academic supervision and access to institutional research resources made this work possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author states that there are no conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

References

- Olofsson, E. To Index or Not to Index: Evaluating Composite B-tree Indexing in PostgreSQL OLTP and OLAP Workloads. Master’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhina, D. Comparative analysis of indexing strategies in PostgreSQL under various load scenarios. Aurora Journals 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indexes in PostgreSQL. ResearchGate publication, 2017.

- Salunke, S. V.; Ouda, A. A Performance Benchmark for the PostgreSQL and MySQL Databases. Future Internet 2025, 16, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inersjö, E. Comparing database optimisation techniques in PostgreSQL. Master’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. PostgreSQL database performance optimization. Master’s thesis, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taipalus, T. Database management system performance comparisons: A systematic literature review. 2023.

- Percona. Benchmarking PostgreSQL: The Hidden Cost of Over-Indexing. Percona Blog, 2025.

- R. Mret. Understanding Index Types in PostgreSQL: A Guide to Optimized Query Performance. Medium, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).