1. Introduction

The remarkable success of deep learning in computer vision has been largely propelled by supervised learning paradigms, which depend on vast datasets annotated with manually curated labels [

1]. While effective, this reliance on large-scale human supervision presents a significant bottleneck, incurring substantial costs and limiting scalability to new domains where labeled data is scarce. This challenge has catalyzed the exploration of Self-Supervised Learning (SSL), a paradigm that aims to learn rich visual representations from unlabeled data by solving auxiliary, or "pretext," tasks.

Prevailing SSL methodologies have predominantly converged on two successful approaches. The first,

contrastive learning, as exemplified by SimCLR [

2] and MoCo [

3], trains a model to pull representations of augmented views of the same image (positives) closer, while pushing them away from representations of other images (negatives). While these methods excel at linear classification by learning invariance to data augmentations, they often discard fine-grained visual details that do not aid in instance discrimination. The second,

masked image modeling, championed by models like MAE [

4] and BEiT [

5], involves masking portions of an input and training the model to reconstruct the missing content.

While these methods have achieved state-of-the-art results, their success is predicated on sophisticated, heuristic-driven pretext tasks. Contrastive methods are often sensitive to the choice of data augmentations and the strategy for sampling negative pairs, while masking approaches are architecturally tied to patch-based models like Vision Transformers [

6]. This reliance on intricate heuristics motivates a foundational question: can we formulate a more universal and principled objective for self-supervised learning?

In this work, we propose a return to first principles, arguing that the

Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle [

7] offers a more fundamental foundation for SSL. The MDL principle posits that the optimal model for a set of data is the one that achieves the greatest compression of that data. We hypothesize that a model optimized for this single, elegant goal of compression will, as a necessary byproduct, learn the most salient and generalizable features of the visual world.

To operationalize this, we introduce the

MDL-Autoencoder (MDL-AE), a framework based on the Vector-Quantized Variational Autoencoder (VQ-VAE) [

8]. The MDL-AE learns a discrete codebook of "visual words" and an encoder that tokenizes images into sequences of these words. Through a rigorous series of experiments, we demonstrate that this compression-driven objective is highly effective at learning a rich vocabulary of local visual concepts. However, our investigation uncovers a critical and non-obvious architectural challenge: the very nature of the learned representations, which we identify as holistic object parts rather than generic primitives, dictates the appropriate choice of downstream architecture. We show that for such representations, a simple linear probe can outperform a sophisticated Vision Transformer head, revealing a crucial interplay between the SSL objective and the downstream evaluation protocol. Our contribution is twofold: first, we present a principled SSL framework and use it to uncover a critical architectural mismatch between holistic tokenizers and sophisticated aggregators. Second, we propose and validate a solution to this mismatch, demonstrating that a targeted self-supervised alignment task can successfully teach a Vision Transformer the ’grammar’ of these holistic tokens, bridging the performance gap. This provides a valuable, end-to-end lesson for the co-design of future representation learning systems. Third, we quantify the trade-off between compression (MDL) and discrimination (Contrastive Learning), showing that while MDL yields richer visual vocabularies, it requires specific architectural alignment to unlock its semantic potential.

2. Related Work

Our research is situated at the intersection of self-supervised representation learning and discrete representation learning. We contextualize our contribution by reviewing the dominant paradigms in SSL and the foundational work on vector quantization that our method extends.

2.1. Contrastive Learning

A significant portion of recent progress in SSL has been driven by contrastive learning. These methods operate on the principle of instance discrimination, where the goal is to learn an embedding space in which different augmented views of the same image are pulled together, while views from different images are pushed apart. Early methods required complex memory banks [

9] or momentum encoders [

3] to maintain a large set of negative samples. SimCLR [

2] simplified this by demonstrating that large batch sizes, combined with strong data augmentation and a learnable projection head, could achieve state-of-the-art results without these components. Subsequent works like BYOL [

10] and SimSiam [

11] further evolved the paradigm by showing that negative samples are not strictly necessary, instead relying on architectural asymmetries like stop-gradients and predictor networks to prevent representation collapse.

Our MDL-AE framework fundamentally differs from contrastive methods. Instead of defining a heuristic objective based on sample similarity, our objective is derived from the first principle of data compression. We require no data augmentation, no explicit negative pairs, and no architectural tricks like momentum encoders or asymmetric networks to prevent collapse. Our regularization is implicitly provided by the information bottleneck of the discrete codebook.

2.2. Masked Image Modeling

Inspired by the success of Masked Language Modeling in NLP, particularly BERT [

12], Masked Image Modeling (MIM) has recently emerged as a highly effective SSL paradigm for Vision Transformers (ViTs). BEiT [

5] was a pioneering work in this area, which involved tokenizing an image into discrete visual tokens using a pre-trained d-VAE [

13] and then training a ViT to predict the original tokens for masked patches. Masked Autoencoders (MAE) [

4] presented a significant simplification, demonstrating that predicting raw pixel values in the latent space of a ViT is a powerful and scalable objective. The core idea of MAE is an asymmetric encoder-decoder architecture where the encoder only operates on the visible patches, making pre-training highly efficient.

While our MDL-AE also involves a reconstruction objective, its mechanism is distinct from MIM. MIM methods operate by corrupting the input (masking patches) and reconstructing it. Our method operates on the full, uncorrupted input and enforces a representational bottleneck via vector quantization. Furthermore, our primary goal is to learn a powerful tokenizer and analyze its representations, whereas the primary goal of MAE is to pre-train the ViT encoder itself.

2.3. Discrete Representation Learning

The concept of learning discrete representations is not new. The Vector-Quantized Variational Autoencoder (VQ-VAE) [

8] is the foundational work upon which our MDL-AE is built. The VQ-VAE introduced the vector quantization layer and the straight-through estimator to enable the learning of a discrete latent codebook through a standard autoencoder framework. The primary motivation for VQ-VAE and its successors, such as VQ-VAE-2 [

14] and VQ-GAN [

15], was for high-fidelity, large-scale

generative modeling. These models excel at producing realistic images and audio by training powerful autoregressive priors (e.g., PixelCNN) or Transformers on the learned discrete codes.

Our work represents a significant repurposing of the VQ-VAE machinery. While we adopt its core training objective, our goal is not generation. Instead, we frame this objective as a direct implementation of the MDL principle for the purpose of learning high-quality discriminative representations. We are the first, to our knowledge, to systematically ablate this VQ-based objective as a standalone SSL method and analyze the unique nature of the "holistic" features it learns, in contrast to the features learned by contrastive or masking approaches. Our contribution lies in shifting the focus from the generative capabilities of discrete codes to their properties as self-supervised feature extractors.

3. Methodology

Our research is predicated on the hypothesis that the principle of Minimum Description Length (MDL) offers a more fundamental objective for self-supervised representation learning than prevailing heuristic-based methods. To operationalize this principle, we introduce the MDL-Autoencoder (MDL-AE), a framework designed to learn a compressed, discrete representation of the visual world. This section details the theoretical underpinnings, the model architecture, the mathematical formulation of our training objective, and the protocols for downstream evaluation.

3.1. A Principled Objective: The Minimum Description Length

The MDL principle, rooted in information theory, states that the best model to describe a dataset is the one that permits the greatest compression of the data. This is formally expressed as a two-part code:

where

is the total description length (in bits) of the data

D,

is the description length of the model

M itself (its complexity), and

is the description length of the data encoded with the help of the model (the reconstruction error). Our entire framework is an endeavor to minimize this objective function, where the "model" is our learned discrete codebook and the encoder that uses it.

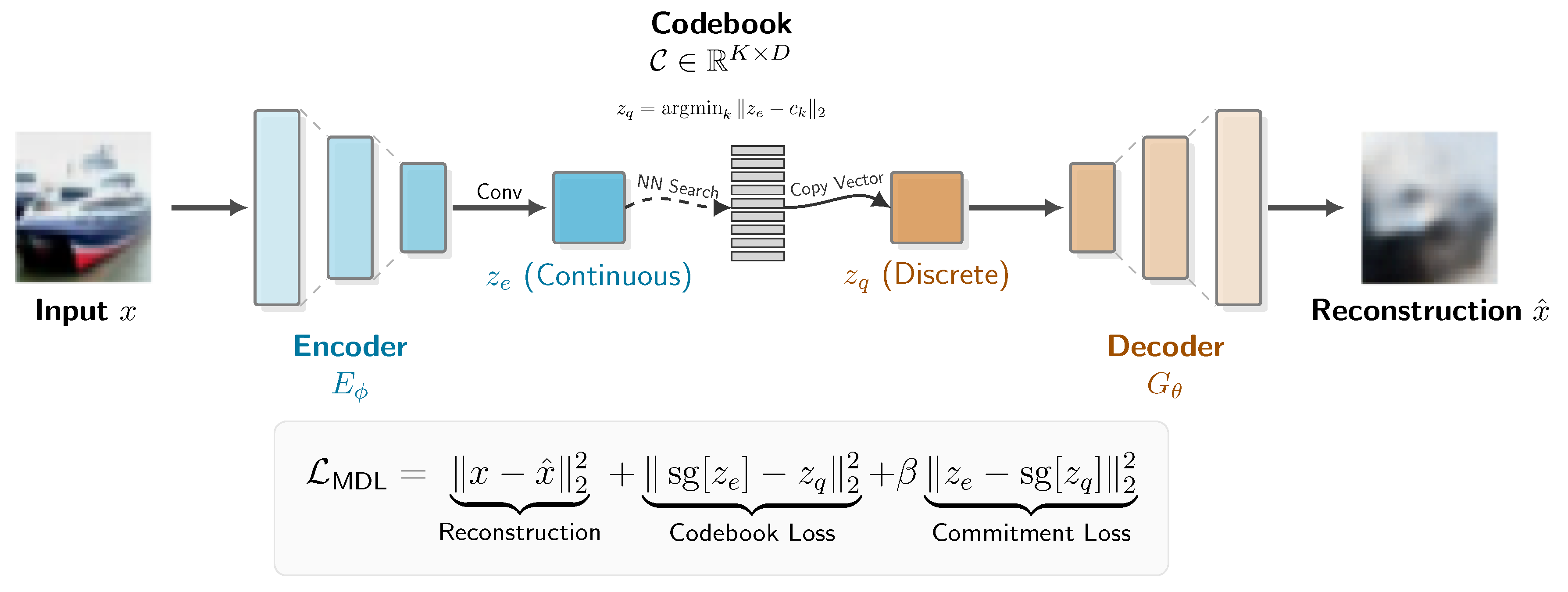

3.2. The MDL-Autoencoder (MDL-AE) Architecture

To instantiate the MDL principle, we designed the MDL-AE, a neural architecture composed of three primary components, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

-

The Encoder (): A neural network, parameterized by , that maps an input image to a continuous intermediate representation . This representation is a spatial feature map. We experimented with two encoder architectures to study the effect of model capacity:

A Simple CNN, consisting of a stack of three strided convolutional layers.

A modified ResNet-18, where the initial convolution is adapted for 32x32 inputs and the final fully-connected layer is replaced with a 1x1 convolutional projection to produce an output with D channels.

The Codebook (C): A learnable embedding layer that serves as our discrete vocabulary of "visual words." The codebook is a matrix , where K is the number of codebook vectors (a hyperparameter, NUM_EMBEDDINGS) and D is the dimensionality of each vector (EMBEDDING_DIM).

The Decoder (): A neural network, parameterized by , that is symmetric to the encoder. It takes a quantized representation and reconstructs the original image .

The core operation of the model is Vector Quantization. For each spatial vector

in the encoder’s output map, we find its nearest neighbor in the codebook

C by Euclidean distance. This produces the quantized map

:

Since the

argmin operation is non-differentiable, we employ the Straight-Through Estimator, detailed in

Section 3.4.

3.3. The Training Objective: Operationalizing MDL

The total loss function

is a carefully designed sum of three terms that directly correspond to the two-part MDL objective.

Reconstruction Loss (

): This term corresponds to

, the cost of encoding the data given the model. It is the squared L2-norm between the original input image and its reconstruction from the quantized representation. Minimizing this term ensures that our discrete codebook is expressive enough to capture the essential information in the image.

-

Codebook Loss (

): This term, along with the commitment loss, corresponds to

, the cost of describing the model itself. It aims to make the "model" (our codebook) as efficient as possible by moving the codebook vectors

closer to the encoder outputs that are mapped to them. This is achieved using a stop-gradient operator

to ensure gradients only update the codebook embeddings.

Here, the gradient from is blocked, so the loss only serves to pull the chosen vector from the codebook towards the encoder’s output .

-

Commitment Loss (

): This is the complementary term that regularizes the encoder. It forces the encoder’s output

to "commit" to its chosen codebook vector, preventing it from growing arbitrarily large. The hyperparameter

controls the strength of this regularization. Again, a stop-gradient is used, but this time to ensure gradients only update the encoder parameters

.

In this term, the gradient from is blocked. The loss penalizes the encoder if its output is far from the codebook vector it was mapped to, encouraging the latent space to align with the learned discrete vocabulary.

3.4. The Straight-Through Estimator

To enable end-to-end training across the non-differentiable quantization step, we utilize the Straight-Through Estimator (STE). In the forward pass, we compute the quantized vector

as described. However, in the backward pass, the gradient from the decoder is passed directly to the encoder’s output

unmodified. This is elegantly implemented as:

This formulation allows the decoder to provide a direct gradient signal to the encoder, as if the quantization step were an identity function, while still using the true quantized values

for reconstruction.

3.5. Downstream Evaluation Protocols

After self-supervised pre-training, we discard the decoder and use the frozen encoder (and in some cases, the frozen codebook C) as a feature extractor. We systematically evaluated the quality of the learned representations using three distinct protocols to probe the nature of the learned features:

Linear Probe on Flattened Features: The encoder produces a spatial feature map . We flatten this map into a single vector of dimension for each image. A single linear layer is then trained on top of these frozen, flattened features to perform 10-way classification.

Linear Probe on Globally Pooled Features: To test for spatial invariance, we apply an AdaptiveAvgPool2d layer to the encoder’s feature map , reducing it to a representation in . This is flattened to a vector of dimension . A linear layer is then trained on these global features.

Vision Transformer (ViT) Head: To evaluate the features as a sequence of tokens, we designed a more sophisticated head. The frozen encoder and VQ layer act as a "tokenizer," producing a sequence of 16 discrete "visual word" vectors for each image. This sequence is prepended with a learnable [CLS] token, augmented with positional embeddings, and fed into a small Transformer encoder. A final linear layer is trained on the output [CLS] token’s representation. In this protocol, only the parameters of the Transformer and the final linear layer are updated.

MAE-Aligned Vision Transformer Head: To test our hypothesis that the architectural mismatch can be resolved, we introduce a two-stage protocol. First, the ViT head is pre-trained on a self-supervised Masked Autoencoding (MAE) task. Given the sequence of 16 discrete tokens from the frozen tokenizer, we mask 75% of them and train the ViT head to predict the original token IDs of the masked positions. After this alignment phase, the masking is removed, and a final linear layer is trained on the output [CLS] token for the downstream classification task, following the same protocol as (3).

3.6. Implementation Details

All models were trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Input images were resized to 32x32 pixels and normalized to a range of [-1, 1]. Our implementation is based on the PyTorch framework. The Simple CNN encoder consists of three strided convolutional layers (kernel size 4, stride 2, padding 1) that map the input from 3 to 64 channels, followed by a final 1x1 convolution. The modified ResNet-18 backbone was adapted for 32x32 inputs by changing the initial convolutional layer to have a kernel size of 3 and a stride of 1, and replacing the final fully-connected layer with a 1x1 convolution to produce a spatial feature map. For the self-supervised pre-training of the MDL-AE, all models were trained using the Adam optimizer. For the downstream evaluation, the encoder was frozen, and a single linear layer was trained on top of the extracted features, again using the Adam optimizer. Specific hyperparameters for both stages are detailed in

Table 1.

4. Results and Discussion

To evaluate our MDL-AE framework, we conducted a systematic series of experiments on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Our investigation was designed not only to measure final classification performance but, more critically, to deconstruct the nature of the learned representations. We demonstrate that while the MDL objective consistently produces high-fidelity tokenizers, the downstream utility of these representations is critically dependent on an architectural match between the learned tokens and the chosen aggregation head. All performance is reported as top-1 linear probe accuracy on the test set.

4.1. The MDL-AE as a High-Fidelity Tokenizer

Our first objective was to validate that the MDL objective could train a powerful visual tokenizer. Across all experiments, regardless of encoder capacity or training duration, the models demonstrated a strong capacity for low-error image compression, indicating the successful learning of a rich visual vocabulary.

Quantitative Evidence

Our baseline Simple CNN model, after 50 epochs, achieved a final reconstruction loss of 0.0495 and a VQ loss of 0.0828. Upgrading the encoder to a ResNet-18 backbone further improved compression, reducing the reconstruction loss to 0.0473 and stabilizing the VQ loss at 0.1251. These consistently low reconstruction errors serve as quantitative proof that the self-supervised task was successful. The encoder and codebook learned a descriptive and efficient discrete representation of the dataset. The problem, as we will show, does not lie in the quality of this tokenizer.

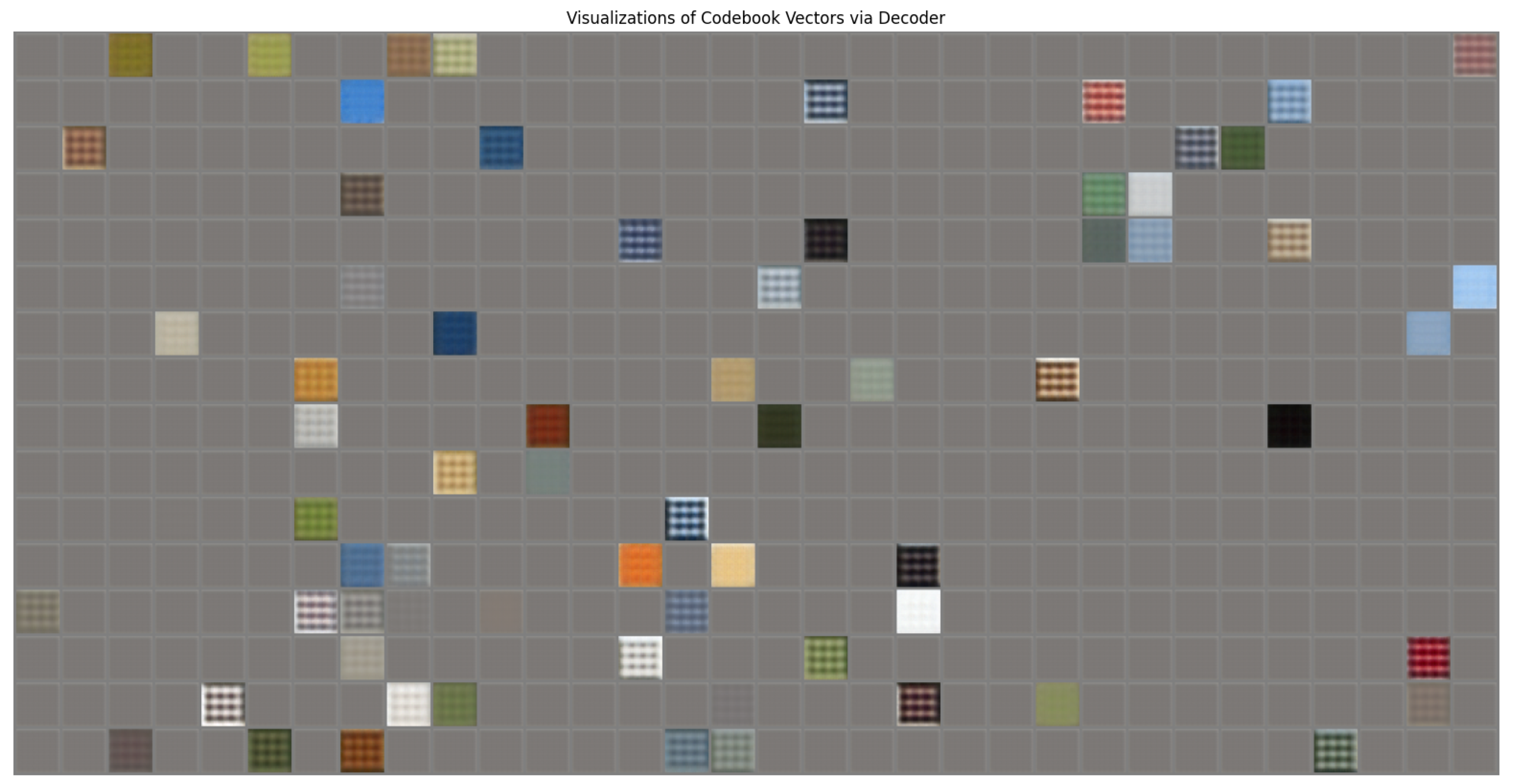

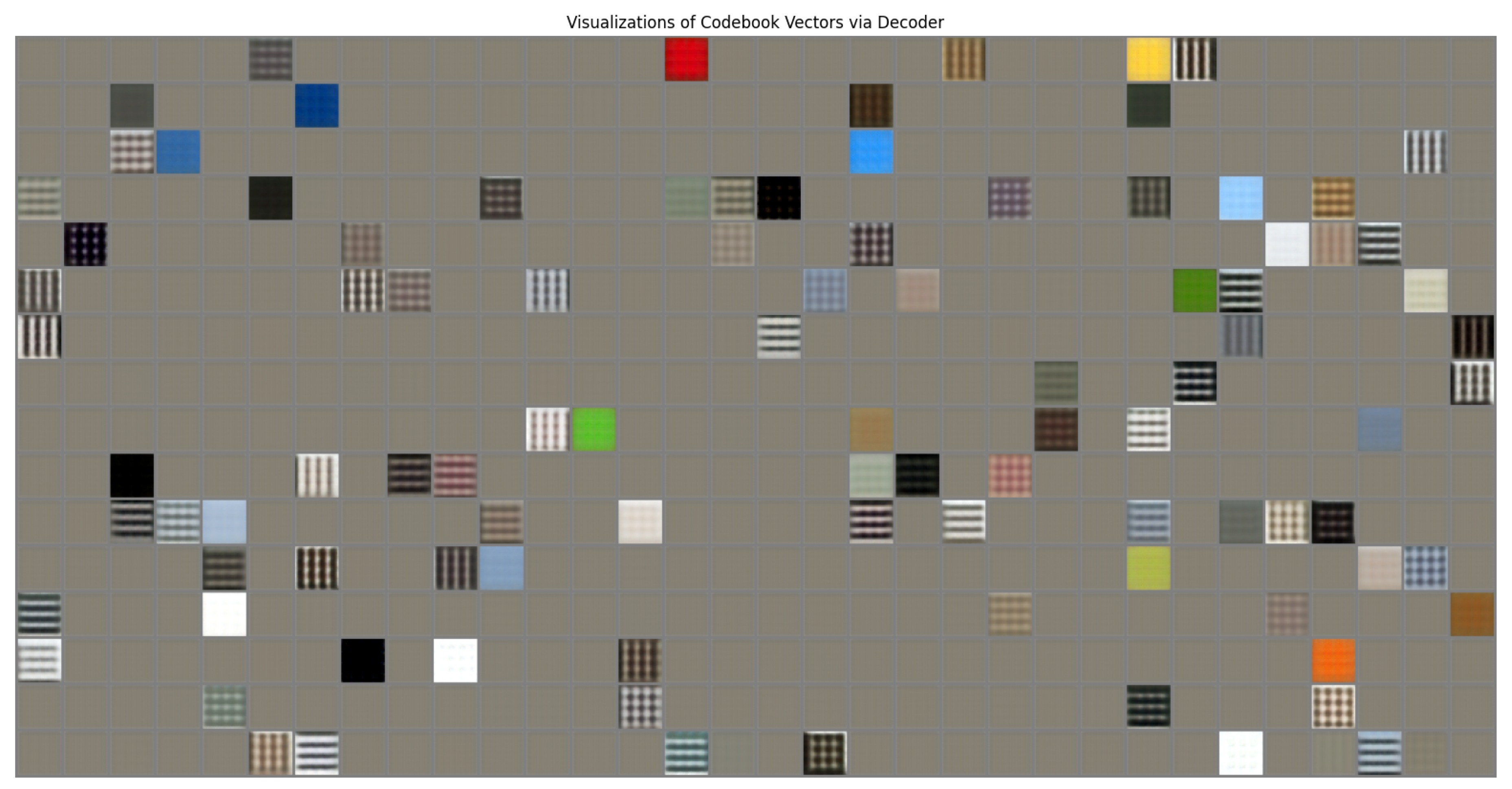

Qualitative Evidence and Codebook Sparsity

The nature of the learned representations is best understood by visualizing the discrete codebooks themselves. A key observation across all experiments was consistent sparsity, a phenomenon where a significant portion of the codebook remains unused. We posit that this is not a failure, but crucial evidence: a model learning generic, reusable primitives (e.g., edges) would utilize its full capacity, whereas our model’s preference for sparsity suggests it is learning a "greatest hits" of more complex, holistic concepts. This is clearly visible in the codebook learned by the Simple CNN (

Figure 2. The utilized vectors consist of a basic vocabulary of flat colors and simple textures. In contrast, the more powerful ResNet-18 encoder learns a visibly richer and more descriptive vocabulary (

Figure 3). Its learned concepts are more intricate, representing complex textures and multi-toned patches that carry significantly more information. This direct comparison of the learned vocabularies provides powerful qualitative proof that the ResNet-18 is a superior tokenizer, corroborating its lower reconstruction loss (

Table 2) and higher-fidelity image reconstructions (

Figure 4). Having established that the ResNet-18 model is demonstrably better at the self-supervised task of compression, we now turn to the paradoxical results of its downstream performance.

4.2. Deconstructing Performance: The Architectural Mismatch

Having established the success of our model in its self-supervised task, we turned to the downstream classification performance, which revealed a series of surprising architectural mismatches.

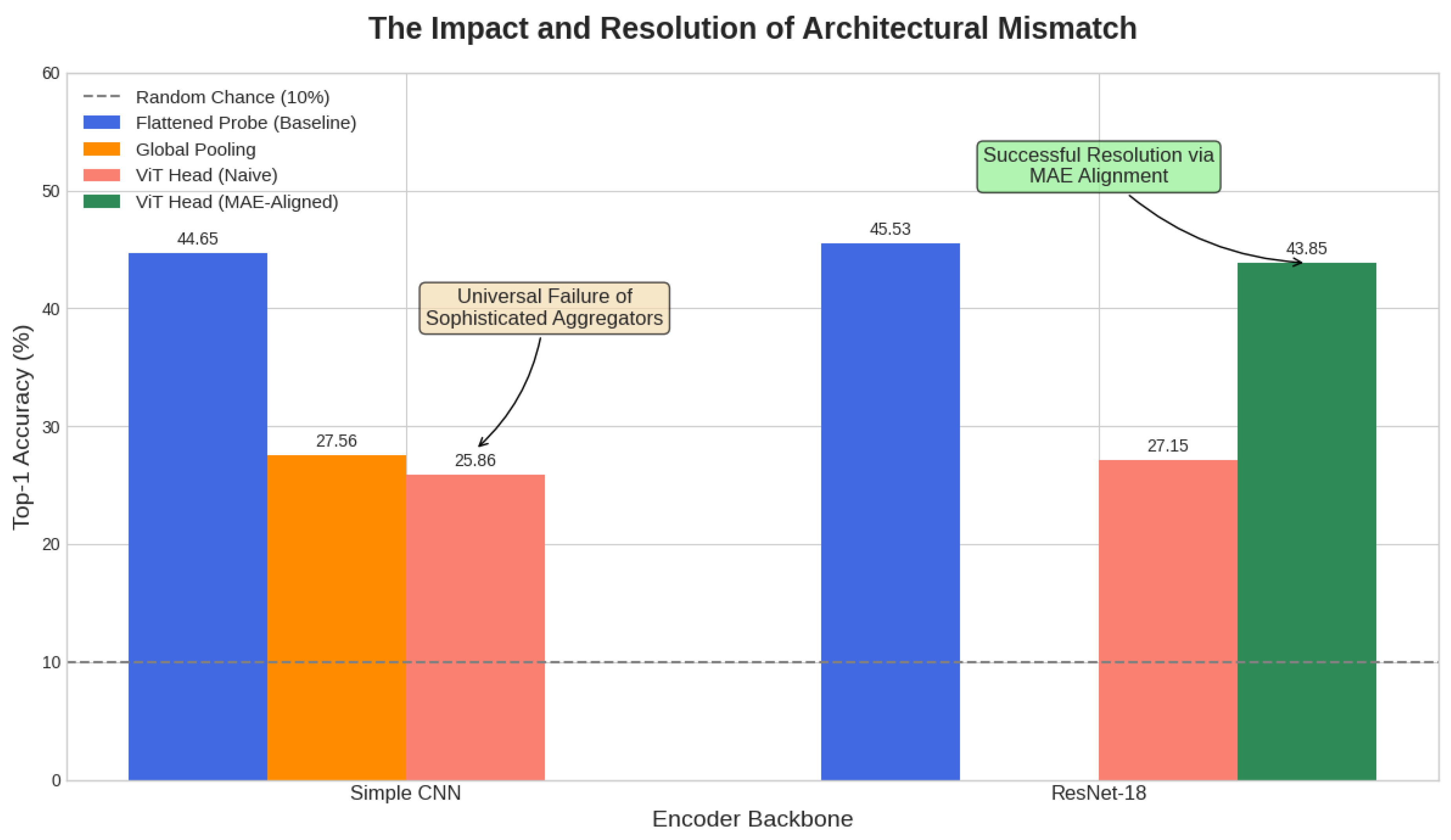

Figure 5.

The Impact and Resolution of Architectural Mismatch. The chart summarizes top-1 accuracy on CIFAR-10. Naively applying sophisticated aggregators (Global Pooling, ViT Head) results in a universal performance collapse. However, the final bar demonstrates a resolution: after a targeted Masked Autoencoding (MAE) alignment task, the ViT Head’s performance dramatically recovers from 27.15% to 43.85%, nearly matching the simple Flattened Probe baseline. This confirms the problem is a solvable mismatch, not an inherent flaw in the representations.

Figure 5.

The Impact and Resolution of Architectural Mismatch. The chart summarizes top-1 accuracy on CIFAR-10. Naively applying sophisticated aggregators (Global Pooling, ViT Head) results in a universal performance collapse. However, the final bar demonstrates a resolution: after a targeted Masked Autoencoding (MAE) alignment task, the ViT Head’s performance dramatically recovers from 27.15% to 43.85%, nearly matching the simple Flattened Probe baseline. This confirms the problem is a solvable mismatch, not an inherent flaw in the representations.

The Paradox of Capacity

Our initial ResNet-18 experiment yielded a profound paradox, which is best illustrated by the qualitative results in

Figure 4. The figure visually demonstrates that the more powerful ResNet-18 encoder (bottom row) produces qualitatively superior reconstructions compared to the Simple CNN (middle row), capturing object silhouettes with higher fidelity. This visual improvement is quantitatively corroborated by its superior compression, evidenced by a lower final reconstruction loss (0.0473 vs. 0.0484,

Table 2). Despite this clear and demonstrable superiority in the self-supervised task, the ResNet-18 model achieved a linear probe accuracy of 45.53% on flattened features, statistically indistinguishable from the 44.65% achieved by the much simpler CNN. This reveals a crucial disconnect: the additional representational detail learned by the better tokenizer, which leads to better reconstructions, is completely lost on the downstream evaluation protocol. A more powerful tokenizer does not guarantee better performance if the tool used to interpret its features is not matched to their nature

The Failure of Aggregation

We hypothesized that a global aggregation mechanism was the missing link. This hypothesis was decisively falsified. Applying Global Average Pooling to the simple CNN’s features caused accuracy to plummet to 27.56%. This proved the features were strongly position-dependent, and that averaging destroyed critical spatial information. More strikingly, employing a sophisticated Vision Transformer (ViT) Head, a state-of-the-art aggregator—also failed. With the Simple CNN tokenizer, it yielded 25.86%, and even when provided with the far superior, higher-fidelity tokens from the ResNet-18 encoder, its performance remained catastrophically low at 27.15%. This consistent failure, regardless of the tokenizer’s quality, points to a fundamental incompatibility between the aggregator and the nature of the learned representations.

4.3. Comparison with Discriminative Baselines

To contextualize the performance of the MDL-AE, we compare our approach against established self-supervised baselines. It is crucial to note that methods like SimCLR [

2] and BYOL [

10] are explicitly designed for discriminative invariance, they are trained to ignore local details (like color or exact texture) to maximize similarity between augmented views. In contrast, our MDL-AE is driven by compression fidelity, requiring the retention of all visual information necessary for reconstruction.

As observed in

Table 3, there remains a performance gap between compression-based objectives (MDL-AE) and invariance-based objectives (SimCLR). This confirms a fundamental trade-off in representation learning:

Discriminative models (SimCLR) learn to discard information (e.g., exact orientation, background color) to achieve high classification accuracy.

Generative/Compression models (MDL-AE) must preserve this information to satisfy the reconstruction bottleneck.

While SimCLR achieves superior linear probing accuracy (88.20%), it produces representations that are "lossy" regarding the visual details of the input. The MDL-AE, achieving 45.53%, lags in linear separability but, as shown in

Figure 4, generates a high-fidelity visual vocabulary. This suggests that pure compression, while satisfying the MDL principle, does not automatically yield linearly separable semantics without an additional mechanism to filter out "nuisance" variables which is a finding that opens critical avenues for future MDL-based research.

4.4. Resolving the Mismatch: Self-Supervised Alignment of the ViT Head

Our central thesis posits that the consistent failure of the ViT head is due to a fundamental architectural mismatch. To validate this and explore a potential solution, we conducted a final experiment based on the "co-design" principle. We hypothesized that the ViT head could be "aligned" to the grammar of our holistic tokens through a targeted self-supervised pre-training task. We froze our best ResNet-18 tokenizer and used it to generate sequences of 16 discrete visual tokens for each image. A small, randomly-initialized ViT head was then pre-trained on a Masked Autoencoding (MAE) objective: given a sequence where 75% of the tokens were masked, it had to predict the original token IDs of the masked positions. This task forces the ViT to learn the spatial and semantic relationships between the holistic concepts learned by the MDL-AE. The results, presented in

Table 2(Exp. 3d), were definitive. After this MAE alignment phase, the ViT head’s accuracy surged from a catastrophic 27.15% to 43.85%. This dramatic recovery of +16.7 percentage points confirms that the ViT’s initial failure was not due to a lack of capacity, but a lack of alignment with the nature of the input representations. This successful intervention strongly validates our core finding: sophisticated architectures require careful co-design with the self-supervised objectives that produce their input representations.

4.5. Synthesis: The Holistic Tokenizer and the Tyranny of the Tool

The complete experimental arc, from the high-fidelity reconstructions seen in

Figure 4 to the consistent failure of sophisticated aggregation, converges on a single, powerful conclusion: the MDL-AE learns as a Holistic Tokenize.

The model’s objective is to reconstruct images from a limited vocabulary. On an object-centric dataset like CIFAR-10, the most efficient way to do this is to learn tokens that represent entire object parts (`a_car’s_wheel`, `a_patch_of_a_horse’s_coat`). These tokens are inherently context-rich and semantically loaded.

This insight explains our full suite of results:

Why the Flattened Probe is the "Least Bad" Option: This protocol functions as a simple "bag-of-object-parts" detector. A linear layer can learn the simple correlation: "if the highly informative `horse_coat_token` is present anywhere in the flattened 1024-dimensional input, the image is likely a horse." It relies on token presence, not relationships.

Why the Transformer Fails: A Transformer is a powerful grammatical tool designed to find complex relationships between generic tokens to build meaning. Our holistic tokens, however, already contain the meaning. Asking a Transformer to find the "grammar" between ’a_car_wheel_token’ and ’a_car_window_token’ is a fundamentally mismatched task. Our results demonstrate this unequivocally: the Transformer’s performance is disastrous regardless of the quality of the holistic tokens. Whether they are the simpler tokens from the CNN or the richer, higher-fidelity tokens from the ResNet, the Transformer is unable to leverage them. Its complexity becomes a liability, as it is the wrong tool for the job of simple "token detection."

In conclusion, our work demonstrates that a self-supervised objective grounded in the MDL principle is highly effective at learning a powerful, discrete visual vocabulary. However, the reconstructive nature of this task biases the model towards learning holistic, position-dependent tokens. This creates a critical architectural challenge for downstream tasks, where sophisticated, relationship-seeking models like Transformers can be demonstrably inferior to simpler linear probes. This finding underscores a crucial principle for future research: self-supervised objectives and downstream architectures must be co-designed, as the very nature of the learned representation dictates the appropriate tool for its interpretation.

5. Conclusion and Future Work

Conclusion:

In this work, we proposed and investigated a self-supervised learning framework, the MDL-AE, grounded in the first principles of Minimum Description Length. Our central thesis was that optimizing for the most efficient, compressed representation of visual data would yield powerful, high-fidelity features. While purely discriminative baselines like SimCLR currently hold the edge in linear separability, our work highlights that compression-based models capture a distinct, holistic set of features that require co-designed aggregators to be effective. Through a rigorous experimental process, we have demonstrated that the MDL-AE is highly effective at its self-supervised task, learning a rich, discrete vocabulary of visual concepts that allow for high-fidelity image reconstruction. However, our most significant contribution stems from the surprising downstream evaluation results. We uncovered a critical architectural mismatch: our reconstructive objective biases the model towards learning holistic, context-rich tokens rather than generic, composable primitives. This finding led to our main conclusion: the nature of the learned representation dictates the optimal downstream architecture. We have shown that for a ’Holistic Tokenizer’ like the MDL-AE, a naively applied Vision Transformer is demonstrably inferior to a simple linear probe. However, our most significant contribution is demonstrating that this is a solvable problem. Through a targeted self-supervised alignment task (MAE), we successfully ’taught’ the Transformer the grammar of these holistic tokens, dramatically recovering the lost performance. This confirms our central thesis: the success of modern architectures is contingent on a fundamental alignment between the types of features learned and the mechanism used to interpret them, underscoring the critical need for deliberate co-design.

Future Work:

This research opens up several exciting avenues. Investigating the behavior of the MDL-AE on datasets with different statistical properties (e.g., scene-based datasets vs. object-centric ones) could provide deeper insights into how the data distribution influences the generic vs. holistic nature of learned representations. Ultimately, our work calls for a more deliberate co-design of self-supervised objectives and their downstream architectures, moving beyond a "one-size-fits-all" approach to representation learning.

References

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. Ieee; 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 9729–9738.

- He, K.; Chen, X.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 16000–16009.

- Bao, H.; Dong, L.; Piao, S.; Wei, F. Beit: Bert pre-training of image transformers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen, J. Modeling by shortest data description. Automatica 1978, 14, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Oord, A.; Vinyals, O.; et al. Neural discrete representation learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, Vol. 30. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Yu, S.X.; Lin, D. Unsupervised feature learning via non-parametric instance discrimination. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 3733–3742.

- Grill, J.B.; Strub, F.; Altché, F.; Tallec, C.; Richemond, P.H.; Buchatskaya, E.; Doersch, C.; Pires, B.A.; Guo, Z.D.; Azar, M.G.; et al. Bootstrap your own latent-a new approach to self-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 21271–21284.

- Chen, X.; He, K. Exploring simple siamese representation learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2021; pp. 15750–15758. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Ramesh, A.; Pavlov, M.; Goh, G.; Gray, S.; Voss, C.; Radford, A.; Chen, M.; Sutskever, I. Zero-shot text-to-image generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2021; pp. 8821–8831. [Google Scholar]

- Razavi, A.; van den Oord, A.; Vinyals, O. Generating diverse high-fidelity images with vq-vae-2. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019, Vol. 32.

- Esser, P.; Rombach, R.; Ommer, B. Taming transformers for high-resolution image synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 12873–12883.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).