Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

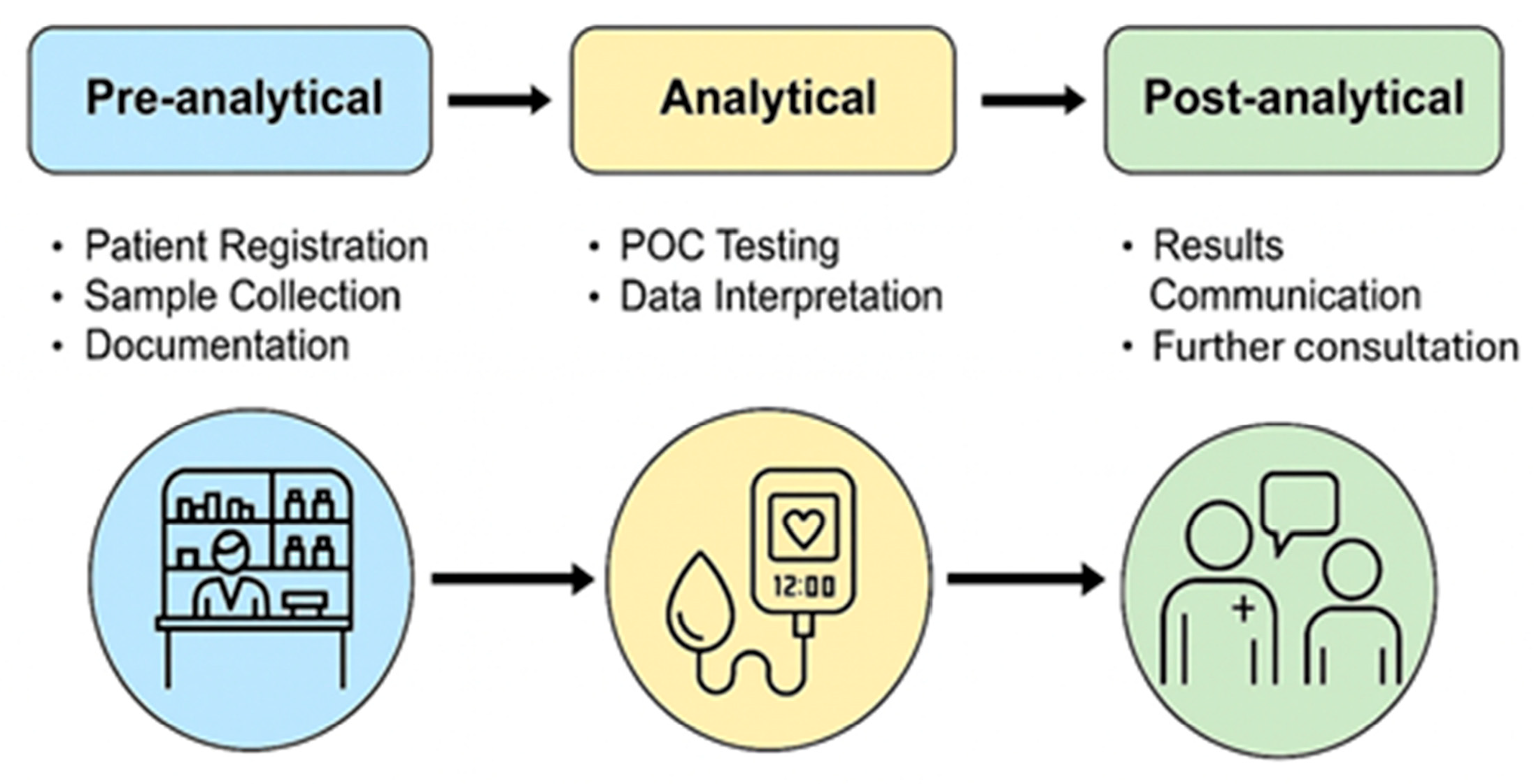

1. Introduction to Point-of-Care Services in Pharmacies

2. Evolution and Regulatory Context of Pharmacy-Based Point-of-Care Services

2.1. The Regulatory Landscape

| Test category | Target application | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Lateral flow immunoassay | Group A Streptococcus Influenza A & B COVID-19 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Helicobacter pylori Mononucleosis Syphilis |

[21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] |

| Molecular-based | Chlamydia Gonorrhea Trichomonas Group A Streptococcus Influenza A & B COVID-19 Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) |

[29] [29] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] |

- Analytical validation – verification of calibration linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ) and coefficient of variation (CV %) against reference laboratory methods [34].

- External quality assessment (EQA) – participation in proficiency-testing schemes organized by accredited laboratories [35].

- Internal quality control (IQC) – routine checks using control materials of known concentration; statistical monitoring via Levey-Jennings plots [36].

- Documentation and traceability – use of barcode-encoded reagents and electronic result logging compliant with data-protection legislation [37].

2.2. Internal and External Quality Control

2.3. Regional Implementation Models

Europe

North America

Asia-Pacific

2.4. Risk Management and Chemical Safety

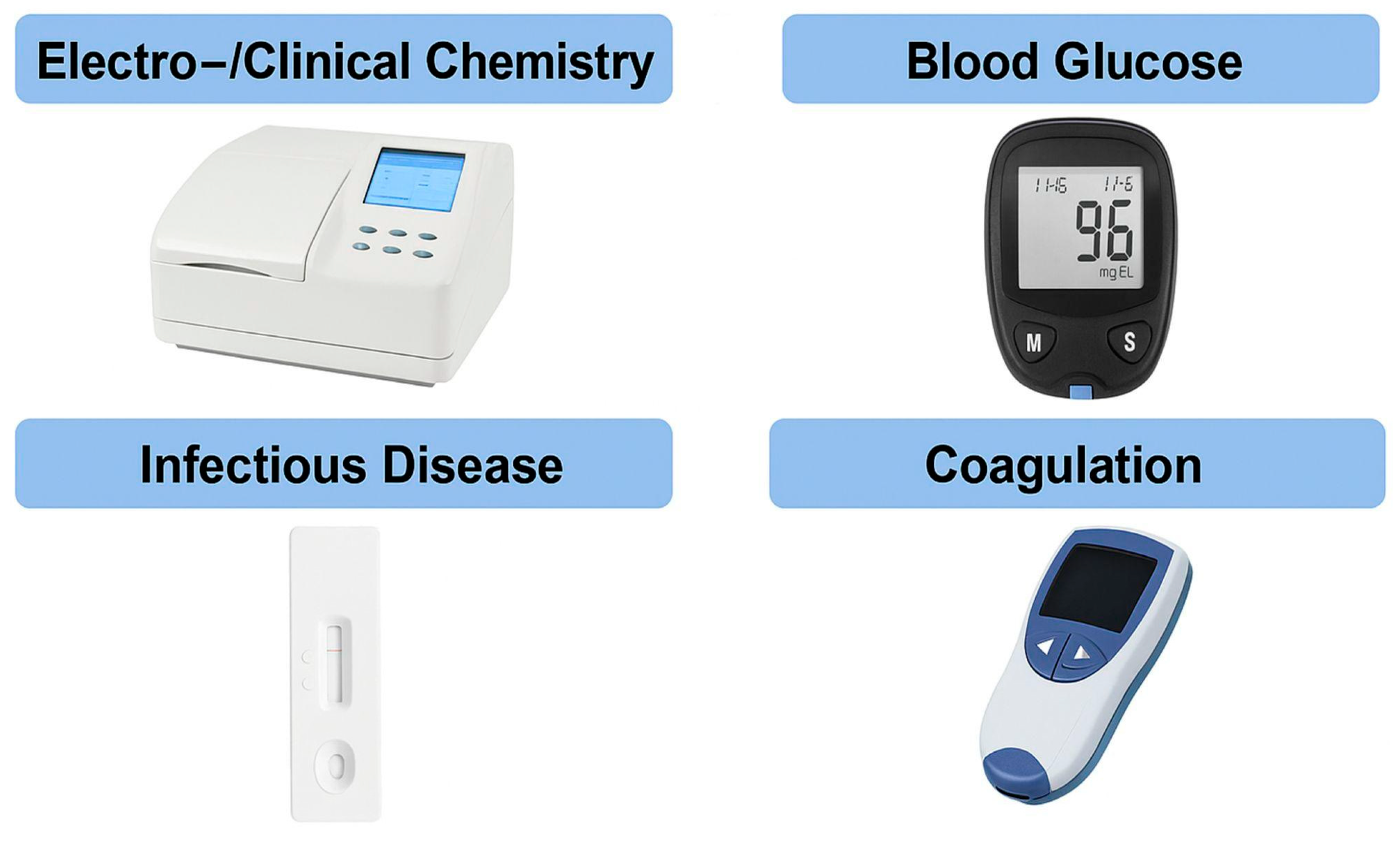

3. Biosensor Technologies and Diagnostic Integration

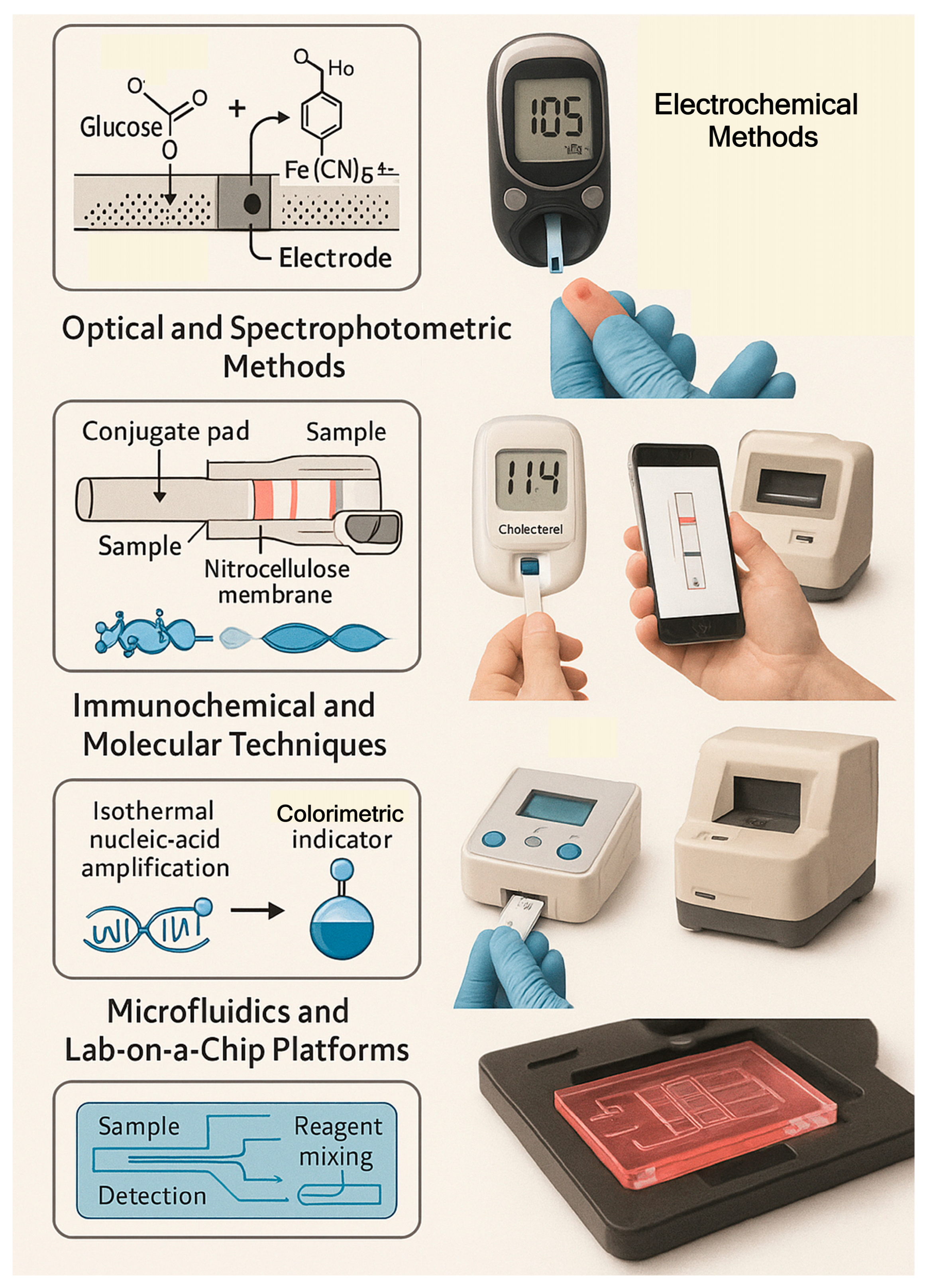

3.1. Electrochemical Systems

3.2. Optical and Spectrophotometric Methods

3.3. Immunochemical and Molecular Techniques

3.4. Microfluidics and Lab-on-a-Chip Platforms

3.5. Integration, Data Handling and Chemometrics

- -

- Sensitivity (S) = ΔSignal/ΔConcentration

- -

- Limit of Detection (LOD) = 3σ / S

- -

- Selectivity determined by cross-reactivity studies with structurally related analytes

- -

- Repeatability and Reproducibility expressed as intra- and inter-assay CVs

- -

- Analytical recovery using spiked control materials

4. Benefits, Challenges and Economic Considerations of Point-of-Care Services in Pharmacies

4.1. Benefits and Challenges

4.2. Economic, Policy and Sustainability Considerations

5. Pharmacist Training and Education for POCT Services

- Analytical Chemistry Core – stoichiometry of assays, Beer–Lambert law, electrochemical potentials and reaction equilibria.

- Instrumental Analysis – calibration curves, signal processing, blank subtraction and sensitivity calculation.

- Bioanalytical Techniques – enzyme kinetics, antibody–antigen binding thermodynamics (Ka, Kd) and enzyme-linked detection.

- Quality Management – statistical process control, uncertainty estimation and ISO 15189 principles.

- Clinical Correlation – translation of numerical results to therapeutic decisions.

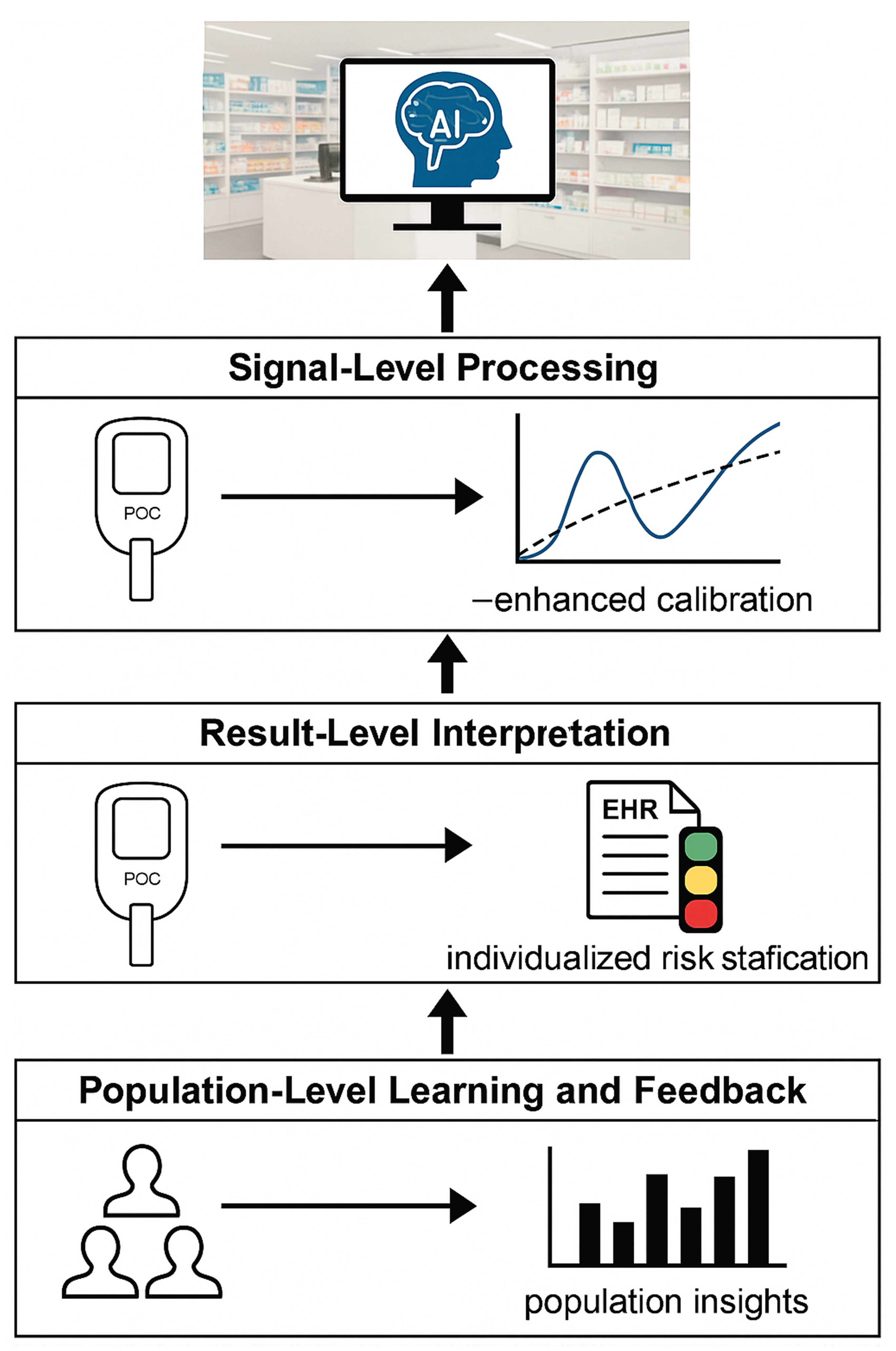

6. Integration of Digital Technologies, Mobile Health (mHealth) and Artificial Intelligence in Point-of-Care Services

6.1. Integration with Telepharmacy and Remote Supervision

6.2. Artificial Intelligence and Decision Support for Pharmacy-Based Point-of-Care Testing

6.3. Population-Level Learning and Continuous Performance Optimization

7. Future Directions, Implementation Barriers and Opportunities for Pharmacies in Point-of-Care Services

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI ANNs CLIA CMS CLIA CDSS CV % CNNs CPT CPAR CRP EHR EQA GDPR Hba1c HIPAA HIV HCV IQC IVDR JCTLM LOD LOQ ML μTAS mHealth NAB NAATs PLS POC POCT PCA QC QMS RSV SVR TGA VOI |

Artificial Intelligence Artificial Neural Networks Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments Centers For Medicare & Medicaid Services Chemiluminescent Immunoassays Clinical Decision-Support System Coefficient Of Variation Convolutional Neural Networks Cost-Per-Test Cost-Per-Accurate-Result C-Reactive Protein Electronic Health Record External Quality Assessment General Data Protection Regulation Glycated Hemoglobin Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Human Immunodeficiency Virus Hepatitis C Virus Internal Quality Control In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation Joint Committee For Traceability In Laboratory Medicine Limit Of Detection Limit Of Quantification Machine Learning Micro-Total-Analysis Systems Mobile Health Net Analytical Benefit Nucleic Acid Amplification Technologies Partial-Least-Squares Regression Point-Of-Care Point-Of-Care Testing Principal-Component Analysis Quality Control Quality Management System Respiratory Syncytial Virus Support-Vector Regression Therapeutic Goods Administration Value-Of-Information |

References

- Chan, J.T.N.; Nguyen, V.; Tran, T.N.; Nguyen, N.V.; Do, N.T.T.; van Doorn, H.R.; Lewycka, S. Point-of-care testing in private pharmacy and drug retail settings: A narrative review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, C.R.; de Oliveira, M.G.G.; Camargo, M.S.; Moreira, P.M.B.; de Castro, P.R.; Aguiar, E.C.; Mistro, S. Improving pharmaceutical practice in diabetes care using point-of-care glycated haemoglobin testing in the community pharmacy. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 32, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihekoronye, R.M.; Akande, O.-O.D.; Osemene, K.P. Management of Point-of-Care Testing (POCT) Services by Community Pharmacists in Osun State Nigeria. Innov. Pharm. 2023, 14, 5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueira, I.; Teixeira, I.; Rodrigues, A.T.; Gama, A.; Dias, S. Point-of-care HIV and hepatitis screening in community pharmacies: A quantitative and qualitative study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widayanti, A.W.; Haulaini, S.; Kristina, S.A. Pharmacists’ roles and practices in pharmaceutical services during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Indones. J. Pharm. 2022, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoti, K.; Jakupi, A.; Hetemi, D.; Raka, D.; Hughes, J.; Desselle, S. Provision of community pharmacy services during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study of community pharmacists’ experiences with preventative measures and sources of information. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierba, A.L.; Pedone, T.; Patel, M.K.; Ciolek, A.; Mehta, M.; Berger, K.; Ramos, L.G.; Patel, V.D.; Littlefield, A.; Chuich, T.; et al. Rethinking the Drug Distribution and Medication Management Model: How a New York City Hospital Pharmacy Department Responded to COVID-19. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepser, D.G.; Klepser, N.S.; Adams, J.L.; Adams, A.J.; Klepser, M.E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on addressing common barriers to pharmacy-based point-of-care testing. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 21, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvet, A.; Espitalier, F.; Grammatico-Guillon, L.; Nay, M.A.; Elaroussi, D.; Laffon, M.; Andres, C.R.; Legras, A.; Ehrmann, S.; Dequin, P.F.; et al. Preanalytical conditions of point-of-care testing in the intensive care unit are decisive for analysis reliability. Ann. Intensive Care 2016, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Blumenfeld, N.R.; Laksanasopin, T.; Sia, S.K. Point-of-care diagnostics: Recent developments in a connected age. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitzbleck, M.; Gervais, L.; Delamarche, E. Controlled release of reagents in capillary-driven microfluidics using reagent integrators. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 2680–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha Leal, M.L.G.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Bell, V.; Forrester, M. Exploring the evolving role of pharmaceutical services in community pharmacies: Insights from the USA, England, and Portugal. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Policarpo, V.; Romano, S.; António, J.H.C.; et al. A new model for pharmacies? Insights from a quantitative study regarding the public’s perceptions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghetti, P.; Pantano, D.; Gennari, C.G.; Casiraghi, A. Regulatory framework of pharmaceutical compounding and actual developments of legislation in Europe. Health Policy 2014, 117, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olczuk, D.; Priefer, R. A history of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) in self-monitoring of blood glucose. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2223. [Google Scholar]

- Adusumalli, R.; Banala, R.R. Advancements in prenatal diagnostics and the effects of EU regulatory frameworks, including the IVDR and MDR: A systematic review. Egypt J. Med. Hum. Genet. 2025, 26, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepser, M.; Koski, R.R. Molecular point-of-care testing in the community pharmacy setting: Current status and future prospects. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.J.; Klepser, D.G.; Klepser, M.E.; Adams, J.L. Pharmacy-based point-of-care testing: How a “standard of care” approach can facilitate sustainability. Innov. Pharm. 2021, 12, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, P.A.; Dobalian, A.; Germinario, F.A. A review and analysis of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988: Compliance plans and enforcement policy. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahles, A.; Goldschmid, H.; Volckmar, A.L.; Ploeger, C.; Kazdal, D.; Penzel, R.; Budczies, J.; Flechtenmacher, C.; Gassner, U.M.; Brüggemann, M.; et al. Regulation (EU) 2017/746 (IVDR): Practical implementation of Annex I in pathology. Pathologie 2023, 44, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, H.; Gallacher, D.; Achana, F.; et al. Rapid antigen detection and molecular tests for group A streptococcal infections: Systematic reviews and economic evaluation. Health Technol. Assess. 2020, 24, 1–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damhorst, G.L.; Lam, W.A. Point-of-care and home-use influenza diagnostics for advancing therapeutic and public health strategies. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 232, S314–S326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goux, H.; Green, J.; Wilson, A.; Sozhamannan, S.; Richard, S.A.; Colombo, R.; Lindholm, D.A.; Jones, M.U.; Agan, B.K.; Larson, D.; et al. Performance of rapid antigen tests to detect SARS-CoV-2 variant diversity and correlation with viral culture positivity. mBio 2024, 15, e02737–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, D.R.; Vrana, C.J.; Dlin, R.E.; Korte, J.E. A global review of HIV self-testing: Themes and implications. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, M.; Khan, M.; Usman, M.A.; Mehmood, Q.; Mehdi, A.M. OraQuick hepatitis C virus self-test: A new frontier in hepatitis C screening. World J. Virol. 2025, 14, 109614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.Y.; Evans, D.J., Jr.; Peacock, J.; Baker, J.T.; Schrier, W.H. Comparison of rapid serological tests with ELISA for detection of Helicobacter pylori. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1996, 91, 942–948. [Google Scholar]

- Kiiskinen, S.J.; Luomala, O.; Häkkinen, T.; Lukinmaa-Åberg, S.; Siitonen, A. Evaluation of serological point-of-care testing of infectious mononucleosis by external quality samples. Microbiol. Insights 2020, 13, 1178636120977481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goza, M.; Kulwicki, B.; Akers, J.M.; Klepser, M.E. Syphilis screening: A review of the Syphilis Health Check rapid immunochromatographic test. J. Pharm. Technol. 2017, 33, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.; Hao, J.; Sigcu, N.; Govindasami, M.; Matswake, N.; Jiane, B.; et al. Validation of rapid point-of-care STI diagnostic tests for self-testing among adolescent girls and young women. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touitou, R.; Bidet, P.; Dubois, C.; Partouche, H.; Bonacorsi, S.; Jung, C.; Cohen, R.; Levy, C.; Cohen, J.F. Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid nucleic acid test for group A streptococcal pharyngitis using saliva samples: Protocol for a multicenter study in primary care. Diagn. Progn. Res. 2023, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, N.; Michael, J.; Doran, K.; Montgomery, E.; Selvarangan, R. Comparison of the ID Now Influenza A & B 2, Cobas Influenza A/B, and Xpert Xpress Flu Point-of-Care Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests for Influenza A/B Virus Detection in Children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01611–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bruijns, B.; Folkertsma, L.; Tiggelaar, R. FDA-authorized molecular point-of-care SARS-CoV-2 tests: A critical review on principles, systems, and clinical performances. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2022, 11, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.B.; Schneider, U.V.; Madsen, T.V.; Nielsen, X.C.; Ma, C.M.G.; Severinsen, J.K.; Hoegh, A.M.; Botnen, A.B.; Trebbien, R.; Lisby, J.G. Evaluation of the analytical and clinical performance of two RT-PCR based point-of-care tests; Cepheid Xpert® Xpress CoV-2/Flu/RSV plus and SD BioSensor STANDARD™ M10 Flu/RSV/SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Virol. 2024, 172, 105674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, A. Methods for the determination of limit of detection and limit of quantitation of analytical methods. Chron. Young Sci. 2011, 2, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudus, N.; Nijs, L.; Nauwelaers, I.; Dequeker, E.M.C. The significance of external quality assessment schemes for molecular testing in clinical laboratories. Cancers 2022, 14, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, L.; Hausch, A.; Mueller, T. Internal quality controls in the medical laboratory: A narrative review of the basic principles of an appropriate quality control plan. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chiron, S.; Tyree, R.; Carson, K.; Raber, L.; Ramadass, K.; Gao, C.; Kim, M.E.; Zuo, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Enhancing clinical data management through barcode integration and REDCap: A scalable and adaptable implementation study. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuluza, F.; Chiumia, F.K.; Nyirongo, H.M.; Kateka, C.; Hosea, R.A.; Mkwate, W. Temperature variations in pharmaceutical storage facilities and knowledge, attitudes, and practices of personnel on proper storage conditions for medicines in southern Malawi. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1209903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbé, B.; Gillet, P.; Beelaert, G.; Fransen, K.; Jacobs, J. Assessment of desiccants and their instructions for use in rapid diagnostic tests. Malar. J. 2012, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoffe, A.; Liu, J.; Smith, G.; Chisholm, O. Regulatory reform outcomes and accelerated regulatory pathways for new prescription medicines in Australia. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2023, 57, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardjadj, M. Regulatory approved point-of-care diagnostics (FDA & Health Canada): A comprehensive framework for analytical validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility in medical devices. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2025, 10, 1622–1637. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Padmore, R.; Petersen, K.; Campbell, C.; Chennette, M.; Sabourin, A.; Shaw, J. Practical application of mathematical calculations and statistical methods for the routine haematology laboratory. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2022, 44, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristelli, L.; Occhipinti, F.; Tumiatti, D.; Antonia, L.; Jani, E.; Daves, M. Implementation of new Westgard rules suggested by the Westgard Advisor software for five immunological parameters. Biochem. Med. 2025, 35, 010701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vierbaum, L.; Kaiser, P.; Spannagl, M.; Wenzel, F.; Thevis, M.; Schellenberg, I. Experiences and challenges for EQA providers in assessing the commutability of control materials in accuracy-based EQA programs. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1416642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haliassos, A. Inter-Laboratory Comparisons and EQA in the Mediterranean Area. EJIFCC 2018, 29, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Gimah, M.; Eli, L.; Johnson, E. Towards seamless data integration: A comparative study of HL7, FHIR, and LOINC in SaaS laboratory systems. Preprint, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster, D.; Miller, R.R. The Joint Committee for Traceability in Laboratory Medicine (JCTLM): A global approach to promote the standardisation of clinical laboratory test results. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2007, 28, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England; NHS Improvement. Point of Care Testing in Community Pharmacies: Guidance for Commissioners and Community Pharmacies Delivering NHS Services; NHS Publications: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesärztekammer. Richtlinie der Bundesärztekammer zur Qualitätssicherung in medizinischen Laboratorien (Rili-BÄK); German Medical Association, 2021.

- Chakravarthy, S.N.; Ramanathan, S.; S.S.; Nallathambi, T.; S.M. EP15A3-based precision and trueness verification of the VITROS HbA1c immunoassay. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2019, 34, 89–94.

- Hutchings, L.; Shiamptanis, A. Evaluation of point-of-care testing in pharmacy to inform policy writing by the New Brunswick College of Pharmacists. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirimacco, R. Evolution of point-of-care testing in Australia. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2010, 31, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, K.; Kushida, K.; Okada, H.; Moles, R.J.; Chen, T.F. Developing and testing quality indicators for pharmacist home-visit services: A mixed methods study in Japan. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 1940–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, L.C.; Lunn, G.; Coico, R. Biosafety: Guidelines for working with pathogenic and infectious microorganisms. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2009, 1, Unit 1A.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Ma, B.; Ju, H. Device integration of electrochemical biosensors. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2023, 1, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, M.N.S.K.S.; Thankappan, S.X. Sensing the future—Frontiers in biosensors: Classifications, principles, and recent advances. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 48918–48987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Qin, W.; Hou, Y.; Xiao, K.; Yan, W. The application of lateral flow immunoassay in point-of-care testing: A review. Nano Biomed. Eng. 2016, 8, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, E.; Şahin, E.A.; Tunçcan, Ö.G.; Yıldız, Ş.; Özkurt, Z.N.; Yeğin, Z.A.; Kalkancı, A. Comparative analysis of chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA)-based tests in diagnosing invasive aspergillosis in hematologic malignancies. Mycoses 2025, 68, e70064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Prasad, D. Isothermal nucleic acid amplification and its uses in modern diagnostic technologies. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Carvalho, V.; Ribeiro, J.; Lima, R.A.; Teixeira, S.; Pinho, D. Advances in microfluidic systems and numerical modeling in biomedical applications: A review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlanda, S.F.; Breitfeld, M.; Dietsche, C.L.; Dittrich, P.S. Recent advances in microfluidic technology for bioanalysis and diagnostics. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, P.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Sanjust, E. Agarose and its derivatives as supports for enzyme immobilization. Molecules 2016, 21, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goicoechea, H.C.; Collado, M.S.; Satuf, M.L.; Olivieri, A.C. Complementary use of partial least-squares and artificial neural networks for non-linear spectrophotometric analysis of pharmaceutical samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 374, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macovei, D.-G.; Irimes, M.; Hosu, O.; Cristea, C.; Tertis, M. Point-of-care electrochemical testing of biomarkers involved in inflammatory and inflammation-associated medical conditions. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshorman, K.; Hussain, R. Community pharmacy-led point-of-care testing (POCT): Expanding roles and strengthening health systems in low- and middle-income countries. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2025, 18, 2578803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, R.; Endalamaw, A.; Erku, D.; Wolka, E.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Assefa, Y. Continuity and care coordination of primary health care: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilka, M.; Duarte, A.; Lábaj, M. Entry and competition of retail pharmacies: A case study of OTC drugs sales and ownership deregulation. Ceska Slov. Farm. 2023, 72, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Serrano, L.P.; Maita, K.C.; Avila, F.R.; Torres-Guzman, R.A.; Garcia, J.P.; Eldaly, A.S.; Haider, C.R.; Felton, C.L.; Paulson, M.R.; Maniaci, M.J.; et al. Benefits and challenges of remote patient monitoring as perceived by health care practitioners: A systematic review. Perm. J. 2023, 27, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakma, N.; Ali, S.B.; Islam, M.S.; Momtaz, T.; Farzana, N.; Amzad, R.; Khan, S.I.; Khan, M.I.H.; Azad, A.K.; Babar, Z.-U.-D.; et al. Exploration of challenges and opportunities for good pharmacy practices in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, M. Challenges and opportunities in pharmacy-based test-and-treat models for infectious diseases: A framework for future implementation. Preprint 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Albasri, A.; Van den Bruel, A.; Hayward, G.; McManus, R.J.; Sheppard, J.P.; Verbakel, J.Y.J. Impact of point-of-care tests in community pharmacies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallimore, C.E.; Porter, A.L.; Barnett, S.G.; Portillo, E.; Zorek, J.A. A state-level needs analysis of community pharmacy point-of-care testing. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, e93–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.; Despotis, G.; Scott, M. Point-of-care testing: Cost issues and impact on hospital operations. Clin. Lab. Med. 2001, 21, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosanchuk, J.S.; Keefner, R. Cost analysis of point-of-care laboratory testing in a community hospital. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1995, 103, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Pharmacy-Based Point-of-Care Testing: A Global Intelligence Report. FIP Self-Care; The Hague, The Netherlands, 2023.

- Lingervelder, D.; Koffijberg, H.; Kusters, R.; IJzerman, M.J. Health economic evidence of point-of-care testing: A systematic review. Pharmacoecon. Open 2021, 5, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St John, A.; Price, C.P. Economic evidence and point-of-care testing. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2013, 34, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alsetohy, W.; El-Fass, K.; Hadidi, S.; Zaitoun, M.F.; Badary, O.; Ali, K.; Ezz-Elden, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Makhlouf, B.; Hamdy, A.; et al. Economic impact and clinical benefits of clinical pharmacy interventions: A six-year multicenter study using an innovative medication management tool. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0311707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindels, J.; Ramaekers, B.; Ramos, I.C.; Mohseninejad, L.; Knies, S.; Grutters, J.; Postma, M.; Al, M.; Feenstra, T.; Joore, M. Use of value-of-information in healthcare decision-making: Exploring multiple perspectives. Pharmacoeconomics 2016, 34, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wong, N.C.B.; Wang, Y.; Zemlyanska, Y.; Butani, D.; Virabhak, S.; Matchar, D.B.; Prapinvanich, T.; Teerawattananon, Y. Mapping the value for money of precision medicine: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1151504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennello, G.; Pantoja-Galicia, N.; Evans, S. Comparing diagnostic tests on benefit-risk. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2016, 26, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Economics of Diagnostic Safety: Setting the Scene. OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024.

- Hirst, J.A.; McLellan, J.H.; Price, C.P.; English, E.; Feakins, B.G.; Stevens, R.J.; Farmer, A.J. Performance of point-of-care HbA1c test devices: Implications for use in clinical practice—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2017, 55, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourdes, R.; Gayle, T.; Chong, Z.; Saminathan, T.; Abd Hamid, H.A.; Rifin, H.M.; Wan, K.S.; Majid, N.L.B.; Ratnam, K.; Riyadzi, M.R.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the CardioChek PA point-of-care testing analyser with a 3-in-1 lipid panel for epidemiological surveys. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 2702. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González, N.A.; Keizer, E.; Plate, A.; Coenen, S.; Valeri, F.; Verbakel, J.Y.J.; Rosemann, T.; Neuner-Jehle, S.; Senn, O. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to reduce antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozucelik, Y.; Collins, J.; Pace, J. Identifying the educational needs of pharmacists engaging in professional development: A global systematic review. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2025, 65, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, H.; Scahill, S.; Kim, J.; Moyaen, R.; Natarajan, D.; Soga, A.; Wong, M.; Martini, N. Pharmacist perceptions and future scope of telepharmacy in New Zealand: A qualitative exploration. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2024, 2024, 2667732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderbush, R.; Anderson, H.; Fant, W.; Fujisaki, B.; Malone, P.; Price, P.; Pruchnicki, M.; Sterling, T.; Weatherman, K.; Williams, K. Implementing pharmacy informatics in college curricula. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2007, 71, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehrer, J.; James, D. The role of pharmacists and pharmacy education in point-of-care testing. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Tallawy, S.N.; Pergolizzi, J.V.; Vasiliu-Feltes, I.; Ahmed, R.S.; LeQuang, J.K.; Alzahrani, T.; Varrassi, G.; Awaleh, F.I.; Alsubaie, A.T.; Nagiub, M.S. Innovative applications of telemedicine and other digital health solutions in pain management: A literature review. Pain Ther. 2024, 13, 791–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.; Suman, R. Medical 4.0 technologies for healthcare: Features, capabilities, and applications. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2022, 2, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasmita, M.A.; Sudarma, I.W.; Jaya, M.K.A.; Irham, L.M.; Susanty, S. Telepharmacy implementation to support pharmaceutical care services during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2024, 77, e3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, A.; Barmpakos, D.; Mavrikou, S.; Papaioannou, G.M.; Tsekouras, V.; Hatziagapiou, K.; et al. System for classifying antibody concentration against SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike antigen with automatic QR code generation for integration with health passports. Explor. Digit. Health Technol. 2024, 2, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoutakou, M.; Kintzios, S. Point-of-care testing (POCT) for cancer and chronic disease management in the workplace: Opportunities and challenges in the era of digital health passports. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatife, O.E.; Makowsky, M.J. Factors influencing implementation of point-of-care testing for acute respiratory infectious diseases in community pharmacies: A scoping review using the CFIR framework. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2024, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanosi, S.M.; Padmanabhan, S. Potential applications of artificial intelligence (AI) in managing polypharmacy in Saudi Arabia: A narrative review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awala, E.; Olutimehin, D. Revolutionizing remote patient care: The role of machine learning and AI in enhancing telepharmacy services. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.D.; Chang, D. Artificial intelligence in point-of-care biosensing: Challenges and opportunities. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, B.; Zhu, Z.; Merkurjev, E.; Ke, L.; Chen, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Wei, G.W. Machine learning methods for small data challenges in molecular science. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 8736–8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta-Velázquez, A.; Arce, F.; Rodríguez-Sevilla, E.; Morales-Narváez, E. Toward smart diagnostics via AI-assisted surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 169, 117378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Guo, Y. Applications and challenges of biomarker-based predictive models in proactive health management. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1633487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, N.A.H. Advancing pharmacy practice: The role of intelligence-driven pharmacy practice and the emergence of pharmacointelligence. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2024, 13, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacharodi, A.; Singh, P.; Meenatchi, R.; Tawfeeq Ahmed, Z.H.; Kumar, R.R.S.; V. N.; Kavish, S.; Maqbool, M.; Hassan, S. Revolutionizing healthcare and medicine: The impact of modern technologies for a healthier future—A comprehensive review. Health Care Sci. 2024, 3, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabiyi, W.; Clark, J.; Bliss, M. Predictive analytics for disease outbreaks: Using artificial intelligence to analyze patterns in health data for early detection of outbreaks. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway, H.; Feder, G.S.; Fitzpatrick, N.K.; Denaxas, S.; Shah, A.D.; Timmis, A.D. Using nationwide ‘big data’ from linked electronic health records to help improve outcomes in cardiovascular disease: 33 studies from the CALIBER programme. Health Technol. Assess. 2017, 21, 1–200. [Google Scholar]

- Madathil, N.T.; Dankar, F.K.; Gergely, M.; Belkacem, A.N.; Alrabaee, S. Revolutionizing healthcare data analytics with federated learning: A comprehensive survey of applications, systems, and future directions. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 28, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.; Joyce, S.; Schembri, R.; Swain, J.; Turiano, R.; Glass, B.D. Transforming care: Exploring consumer and pharmacist perceptions of expanded pharmacy practice in rural and remote communities. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberto, J. Challenges and opportunities of local pharmacies in Talavera, Nueva Ecija: A basis for an operational plan. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenert, A.C.; Bertsche, T. Implementation, barriers, solving strategies and future perspectives of reimbursed community pharmacy services: A nationwide survey in Germany. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppa, P.B.; Müller, C.; Schlichtiger, A.; Schlebusch, H. Point-of-care testing (POCT): Current techniques and future perspectives. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2011, 30, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalupski, B.; Elroumi, Z.; Klepser, D.G.; Klepser, N.S.; Adams, A.J.; Klepser, M.E. Pharmacy-based CLIA-waived testing in the United States: Trends, impact, and the road ahead. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2024, 20, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingwoke, J.; Onuzulike, I.; Egwu, K.; Duru, P.; Ezeanolue, C.; Onyekwere, F.; Agu, P.; Nweke, G.; Onyia, E.; Ajibo, O.; et al. Implementation of point-of-care testing in community pharmacies in Enugu State, Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. Pharm. Educ. 2025, 25, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortblad, K.F.; Kuo, A.P.; Mogere, P.; Roche, S.D.; Kiptinness, C.; Wairimu, N.; Gakuo, S.; Baeten, J.M.; Ngure, K. Low selection of HIV PrEP refills at private pharmacies among clients who initiated PrEP at public clinics: A mixed-methods study in Kenya. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.; Vieira, I.; Pedro, M.I.; Caldas, P.; Varela, M. Patient satisfaction with healthcare services and techniques used for its assessment: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Bista, D.; Kc, B. Patients’ perceptions on community pharmacy services in Kathmandu Metropolitan. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, S.; Lorenzoni, L.; Marino, A.; Murtin, F. The impact of decentralization on the performance of healthcare systems: A nonlinear relationship. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIsaac, M.; Buchan, J.; Abu-Agla, A.; et al. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030—A Five-Year Check-In. Hum. Resour. Health 2022, 20, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare system | Reduced hospital burden; faster diagnosis | Variable reimbursement; policy gaps |

| Pharmacy sector | Diversified revenue; enhanced visibility | Infrastructure investment |

| Patients | Convenience; improved adherence | Perception of test reliability |

| Society | Better disease control; antimicrobial stewardship | Need for regulation and data protection |

| Cost category | Cost (in €) |

|---|---|

| Equipment (read-out device) | 2000-6000 |

| Quality control | 300/year |

| Test reagents | 1-2/test |

| Software licence & update, IoT connectivity | 200/year |

| Analyte | Device Type | Analytical R² vs Laboratory | Clinical Outcome Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | Optical photometry | 0.97–0.99 | Same-visit HbA1c testing improved diabetes control; ~7–10% more patients reached target HbA1c | [83] |

| Total Cholesterol | Electrochemical | 0.95–0.98 | Immediate lipid results increased statin treatment adherence by ~10–15% | [84] |

| CRP | Lateral-flow immunoassay | 0.93–0.97 | Reduced unnecessary antibiotic prescribing in respiratory infections | [85] |

| Category | Key Competencies | Common Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical interpretation | Result analysis, referral decisions | Lack of training, time constraints |

| Technical skills | Device operation, QC procedures | Cost of equipment, maintenance |

| Communication | Counseling, confidentiality | Space limitations, privacy issues |

| Management | Record keeping, workflow integration | Inconsistent reimbursement |

| Region | Reimbursement Mechanism | Policy Instruments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | National health service contracts | Standardized accreditation, IVDR 2017/746 | [110] |

| North America | Insurance & Medicare billing codes | CLIA-waived classification; collaborative practice | [111] |

| Asia-Pacific | Mixed private/public schemes | Pharmacy-led screening programs, national POCT standards | [112] |

| Africa | NGO & donor support | Capacity-building projects, malaria/HIV POCT policies | [113] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).