Background

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is no longer viewed simply as a problem of will-power. Brain-imaging and spectroscopy studies point to a stubborn loop linking the prefrontal cortex to the striatum, driven largely by glutamate. When that loop gets "stuck," urges to hunt for food and the emotions that follow—guilt, shame, numbness—tend to feed on one another (1).

Unfortunately, the tools we usually reach for—cognitive-behavioural therapy, an SSRI, maybe lisdexamfetamine—often move that loop only slowly, especially in teenagers who are also juggling depression or social isolation. Over the past decade, however, researchers have noticed that medicines able to kick-start glutamatergic plasticity can loosen these circuits in a matter of hours or days rather than months.

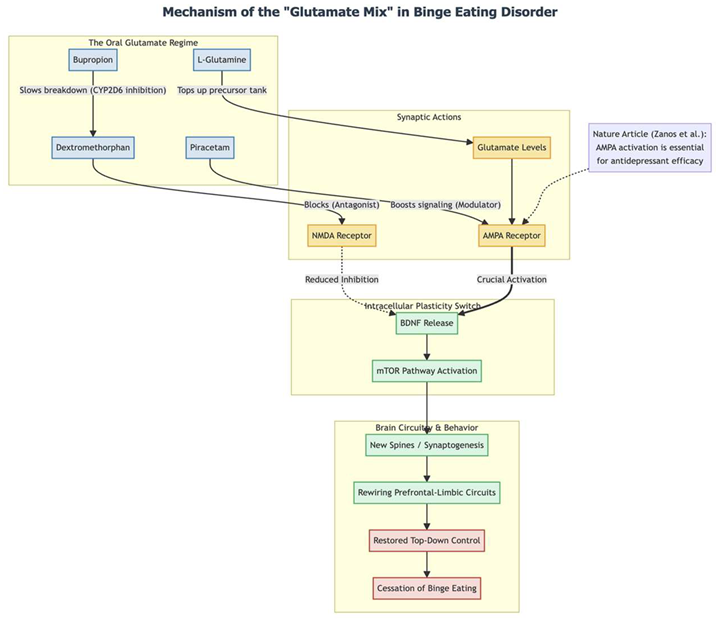

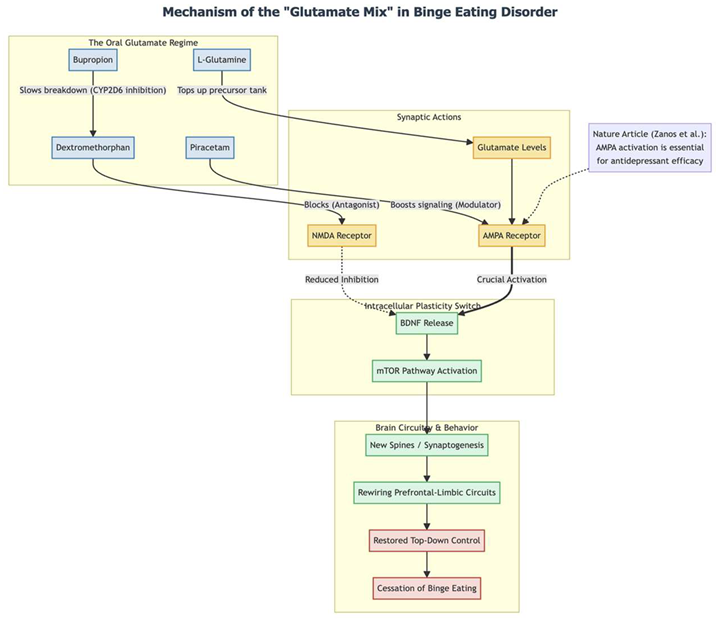

Ketamine is the poster child for this effect. At sub-anaesthetic doses it blocks NMDA receptors on inhibitory interneurons, unleashing a brief glutamate wave that slams AMPA receptors, releases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), flips the mTOR switch, and sprouts new dendritic spines—all within the same afternoon (2, 3, 4). Small clinical series have reported dramatic drops in binge–purge episodes and body-image obsession after one or two ketamine sessions in otherwise treatment-resistant anorexia, bulimia, and BED (5, 6, 7, 8).

Slower-acting glutamate modulators point in the same direction. Topiramate, memantine, and the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine have all cut binge frequency, though patients wait weeks to feel the change (9, 10). Taken together, these findings beg an obvious question: could we recreate ketamine’s rapid "reset" with an inexpensive oral cocktail that hits NMDA, boosts AMPA, and restocks presynaptic glutamate—without IV drips or monitoring suites?

The following case describes a 16-year-old girl whose severe, newly emergent BED—and accompanying depression and school refusal—resolved within days of starting such a regimen: dextromethorphan for NMDA blockade, bupropion to slow its metabolism, piracetam to amplify AMPA signalling, and L-glutamine to keep the glutamate supply topped up (11). Her experience adds a small but provocative data point to the growing evidence that ketamine-style neuroplasticity might be achievable in an ordinary outpatient setting.

Methods

Between mid-October and late November 2025 we followed a single adolescent at Cheung Ngo Medical, a private outpatient psychiatry practice in Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong. The patient was seen, prescribed medication, and monitored exclusively by the author (Dr Cheung).

On 14 October 2025 we began an oral protocol designed to boost rapid glutamatergic plasticity. The daily schedule was dextromethorphan hydrobromide 30 mg twice daily (total 60 mg), bupropion XL 150 mg each morning to slow dextromethorphan metabolism via CYP2D6 inhibition, piracetam 600 mg twice daily (total 1 200 mg), and L-glutamine 1 000 mg once daily. Throughout the six-week observation window these four agents and their doses stayed the same; only a later add-on of low-dose pregabalin and propranolol addressed residual somatic anxiety.

At each visit we combined structured rating scales with an open clinical interview. Depression was tracked with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and anxiety with the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). During the interview we documented mood, school attendance, social supports, eating patterns, and the frequency of any binge-purge behaviour.

Follow-up appointments were scheduled two weeks after starting medication (28 October 2025) and again at six weeks (25 November 2025). No other therapeutic interventions—psychotherapy, dietetic input, or school accommodations—were introduced during this initial period so that medication effects could be observed in relative isolation.

The patient and her legal guardian supplied written informed consent for the anonymous use of her clinical information, and the adolescent provided written assent. All potentially identifying details have been removed in keeping with ethical standards for case reports.

Results

In October 2025 a 16-year-old secondary-school student walked into clinic looking defeated. For the previous six weeks her life had been shrinking: she stayed home instead of going to class, could not find the energy to text friends, and spent whole evenings in bed scrolling aimlessly. Her parents worked abroad, so she was living by herself in Hong Kong; the one friend who had shared the apartment had recently moved out, leaving the flat—and her—uncomfortably quiet.

Loneliness quickly turned into something more concrete. Whenever she found herself alone, an almost irresistible wave of hunger crashed over her. She would raid the kitchen, eat until she felt sick, sometimes purge, then sit with crushing guilt. These binges happened two or three times at nearly every meal. A year earlier she had lurched to the opposite extreme, surviving on one meal a week and dropping 10–20 kg, but this new cycle felt even more out of control.

During the initial visit she was tearful, spoke in a whisper, and struggled to keep her thoughts on track. She described "blanking out" during tests even though she knew the material. Nights were broken by long stretches of wakefulness. On screening she scored 17 on the PHQ-9 (moderately severe depression) and 9 on the GAD-7 (moderate anxiety).

Because her main complaint was the overpowering urge to binge, we decided to try a medication combination aimed at rapidly resetting glutamate signalling—the same pathway targeted by ketamine but in oral form. On 14 October 2025 she started dextromethorphan 30 mg twice daily, bupropion XL 150 mg each morning (to slow DXM’s breakdown), piracetam 600 mg twice daily, and L-glutamine 1 g daily. No therapy sessions or dietary rules were added; we wanted to see what the biology alone could do.

Two weeks later she bounded into the office, almost unrecognisable. "The urge is just…gone," she told me, a little shocked. Within the first week the binges had stopped entirely; she was eating three ordinary meals without losing control. Her mood had lightened, she was back in school every day, and had even re-joined handball practice. Concentration was returning, and her PHQ-9 had fallen to 12. She still felt flickers of anxiety—brief heart flutters, a tight chest—so we later added a small dose of pregabalin.

At the six-week mark (25 November 2025) her progress had held steady. Not a single binge or purge episode had returned, even on weekends spent alone. "Food isn’t an emotional thing anymore," she said. Being alone no longer triggered panic or cravings. Her PHQ-9 had drifted down to 8, below the threshold for clinical depression, and the earlier somatic anxiety had disappeared. She remained on the same four-drug regimen, reporting only mild early restlessness that had faded on its own.

In just six weeks this teenager moved from daily, guilt-soaked binges and school refusal to stable mood, full attendance, and a peaceful relationship with food. The shift began within days of starting the oral glutamatergic protocol—suggesting that, at least for her, recalibrating synapses opened the door to recovery.

Conclusion

The way this teenager’s binge eating vanished almost overnight is striking. Within a few days of starting the four-drug "glutamate mix," the binges stopped and never returned during the six-week follow-up. That pace of change is rarely seen in adolescent binge-eating disorder, a condition that usually shrugs off CBT, SSRIs, or stimulants for months at a time. Because she was not receiving any formal therapy when the urges disappeared, the timing points to the medication itself rather than a placebo lift or a lucky spontaneous remission.

Mechanistically, the pill combination seems to mimic ketamine’s rapid-plasticity switch but in oral form. Dextromethorphan briefly blocks NMDA receptors; bupropion slows its breakdown; piracetam boosts AMPA signaling; and L-glutamine tops up the presynaptic glutamate tank (11). Animal and human work suggests that this one-two-three punch—NMDA block, glutamate burst, AMPA push—releases BDNF and flips the mTOR pathway, sprouting new spines in prefrontal-limbic circuits (13, 3, 4, 14). For someone whose reward circuits scream for food whenever she’s alone, a fast rebuild of top-down control could explain why the urge simply "switched off."

Her brighter mood, steadier school attendance, and sharper focus fit the same story. Frontostriatal and prefrontal networks are disrupted in both mood and eating disorders; when those circuits regain flexibility, depression and inattention often improve as well (15). Adult data back this up: topiramate, another glutamate modulator, cuts binge frequency (9), and the dextromethorphan-bupropion pill (Auvelity) delivers a rapid antidepressant lift (12). Our case suggests that stacking several glutamatergic levers at once—NMDA, AMPA, and glutamine supply—may accelerate and deepen the effect, even in adolescents.

One case, of course, cannot settle questions of safety, ideal dosing, or durability. Still, it offers real-world evidence that a low-cost, all-oral "glutamate cocktail" might deliver ketamine-like circuit rewiring without an IV line. Carefully controlled trials are now needed to see whether this rapid, complete response can be replicated—and, if so, how best to harness it for the many teens and adults still trapped in the binge cycle.

Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding Statement

None declared.

References

- McGrath T, Baskerville R, Rogero M, et al. Emerging Evidence for the Widespread Role of Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Nutrients. 2022;14(5):917.

- Autry AE, Adachi M, Nosyreva E, et al. NMDA receptor blockade at rest triggers rapid behavioural antidepressant responses. Nature. 2011;475(7354):91–95. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, et al. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science. 2010;329(5994):959–964. [CrossRef]

- Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature. 2016;533(7604):481–486. [CrossRef]

- Mills IH, Park GR, Manara AR, et al. Treatment of compulsive behaviour in eating disorders with intermittent ketamine infusions. QJM. 1998;91(7):493–503. [CrossRef]

- Ragnhildstveit A, Jackson LK, Cunningham S, et al. Case Report: Unexpected Remission From Extreme and Enduring Bulimia Nervosa With Repeated Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:764112. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz T, Trunko ME, Feifel D, et al. A longitudinal case series of IM ketamine for patients with severe and enduring eating disorders and comorbid treatment-resistant depression. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(5):e03869. [CrossRef]

- Robison R, Lafrance A, Brendle M, et al. A case series of group-based ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for patients in residential treatment for eating disorders with comorbid depression and anxiety disorders. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):65. [CrossRef]

- McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(2):255–261. [CrossRef]

- Bisaga A, Danysz W, Foltin RW. Antagonism of glutamatergic NMDA and mGluR5 receptors decreases consumption of food in baboon model of binge-eating disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(11):794–802. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. DXM, CYP2D6-Inhibiting Antidepressants, Piracetam, and Glutamine: Proposing a Ketamine-Class Antidepressant Regimen with Existing Drugs. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy B, Bunn H, Santalucia M, et al. Dextromethorphan-bupropion (Auvelity) for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2023;21(4):609–616.

- Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338(6103):68–72. [CrossRef]

- Son H, Baek JH, Go BS, et al. Glutamine has antidepressive effects through increments of glutamate and glutamine levels and glutamatergic activity in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2018;143:143–152. [CrossRef]

- Guardia D, Rolland B, Karila L, et al. GABAergic and glutamatergic modulation in binge eating: therapeutic approach. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(14):1396–1409. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).