1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of autonomous computational systems has generated significant interest in developing intelligent agents capable of operating effectively in complex, dynamic environments [

9]. Such systems must demonstrate robust problem-solving capabilities, particularly when confronted with logic-intensive challenges that require multistep reasoning and adaptive decision-making [

11]. The field of autonomous agent research has evolved substantially, with recent work focusing on architectures that can generalize across domains without extensive task-specific training [

2].

Security-oriented environments present particularly challenging testbeds for autonomous agents due to their inherent complexity and the need for sophisticated reasoning capabilities [

3]. Capture The Flag (CTF) competitions, which simulate real-world cybersecurity scenarios, provide standardized frameworks for evaluating agent performance in realistic conditions [

10]. Previous research has demonstrated varying levels of success with different agent architectures, though many approaches have struggled to achieve consistent high performance across diverse challenge categories [

5].

This research addresses critical gaps in autonomous agent evaluation by systematically analyzing multiple architectural approaches within standardized security challenge environments. Our work builds upon existing frameworks while introducing novel methodological improvements that enhance agent performance and reliability. Through comprehensive experimentation, we demonstrate that carefully designed reasoning architectures can significantly outperform previous implementations, achieving state-of-theart results on established benchmarks [

1].

The primary contributions of this work include: (1) development and evaluation of multiple agent architectures for complex task environments; (2) systematic analysis of performance across different challenge categories; (3) identification of key architectural components that contribute to successful task completion; and (4) establishment of new performance benchmarks for autonomous agent systems in security-oriented contexts. Our findings provide valuable insights for future research in autonomous systems and computational intelligence.

2. Related Work

Research in autonomous computational agents has progressed significantly in recent years, with numerous studies exploring different architectural approaches and evaluation methodologies [

9]. Early work in this domain focused primarily on rule-based systems and predefined behavior patterns, which demonstrated limited adaptability in complex environments [

4]. More recent approaches have leveraged advances in machine learning and reasoning algorithms to create more flexible and capable agent architectures [

12].

The evaluation of computational agents in security contexts has emerged as an important research direction, with several benchmark frameworks developed to standardize performance assessment [

3]. InterCode-CTF represents one such framework, providing a collection of security challenges adapted from real-world scenarios [

10]. Previous studies utilizing this benchmark have reported varying success rates, with earlier implementations achieving approximately 29-40% task completion rates [

5]. These results highlighted the challenges inherent in developing agents capable of handling diverse security tasks.

Recent work by Abramovich et al. introduced the EnIGMA framework, which achieved improved performance through enhanced interactive tools and specialized agent design [

1]. Their approach demonstrated the potential of sophisticated tool integration and interactive capabilities, reaching 72% success on InterCode-CTF challenges. However, the complexity of their implementation raised questions about the scalability and generalizability of such approaches across different environments and task types.

Parallel research efforts have explored reasoning architectures for autonomous agents, with ReAct (Reasoning + Action) emerging as a promising framework for combining cognitive processes with environmental interactions [

11]. This approach enables agents to generate explicit reasoning steps before executing actions, potentially improving decision quality and task performance. Similarly, Tree of Thoughts methodologies have been proposed to enhance problemsolving capabilities through parallel exploration of multiple solution paths [

12].

The concept of “unhobbling” agents, as discussed by Aschenbrenner, emphasizes the importance of providing appropriate tools and capabilities to enable effective performance [

2]. This perspective aligns with findings from Project Naptime, which demonstrated significant performance improvements through careful environmental design and capability provisioning [

6]. Our work builds upon these insights while maintaining architectural simplicity and generalizability.

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Framework

Our research employed the InterCode-CTF benchmark as the primary evaluation framework, comprising 100 security challenges across multiple categories including General Skills, Reverse Engineering, Cryptography, Forensics, Binary Exploitation, and Web Exploitation [

10]. This benchmark provides standardized task specifications and evaluation metrics, enabling consistent comparison across different agent architectures and implementations. The environment simulates real-world computational systems, requiring agents to interact through command-line interfaces and interpret textual feedback to progress through challenges.

We implemented several modifications to the original InterCode-CTF framework to address technical limitations and ensure experimental validity. Specifically, we excluded tasks requiring external internet access or visual processing capabilities, resulting in a refined dataset of 85 evaluable challenges. Additionally, we corrected inconsistencies in flag formats and task specifications to maintain standardization across all experiments. These adjustments ensured that performance measurements accurately reflected agent capabilities rather than environmental artifacts.

The experimental infrastructure utilized Docker containers to provide isolated execution environments for each task attempt. Agents interacted with these environments through a structured interface that captured commands and observations while maintaining state between interactions. This setup enabled comprehensive logging of agent behavior and decision processes, facilitating detailed analysis of performance characteristics and failure modes across different architectural approaches.

3.2. Agent Architectures

We designed and implemented four distinct agent architectures to evaluate different approaches to autonomous task solving:

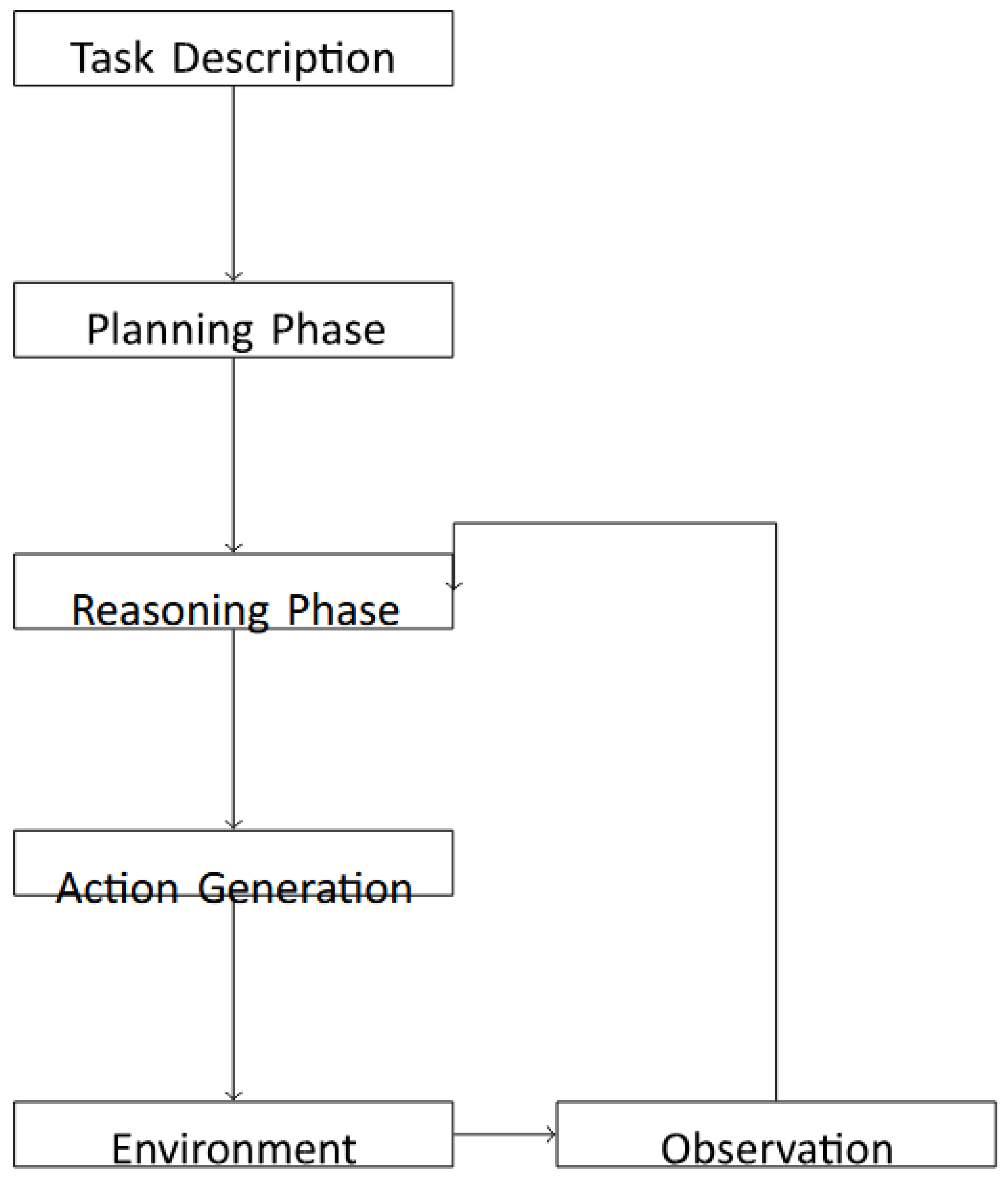

Figure 1.

Architecture of the ReAct&Plan hybrid agent showing the integration of planning and reasoning phases with environmental interactions.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the ReAct&Plan hybrid agent showing the integration of planning and reasoning phases with environmental interactions.

Baseline Architecture: Our baseline implementation followed the original InterCode design with minor modifications, providing agents with up to 10 actions per task, access to task descriptions, and limited history of previous interactions. This architecture served as a reference point for evaluating the performance improvements achieved through more sophisticated designs.

Plan&Solve Architecture: This architecture incorporated explicit planning phases where agents generated multi-step strategies before beginning task execution. The planning process considered both the task description and available environmental resources, enabling more systematic approaches to challenge solving. Agents could replan during execution based on intermediate observations, adapting their strategies as new information became available.

ReAct Architecture: Implementing the Reasoning + Action paradigm [

11], this architecture required agents to generate explicit reasoning steps before each action. The reasoning process integrated task objectives, environmental observations, and historical context to determine appropriate next steps. This approach promoted more deliberate decisionmaking and improved the interpretability of agent behavior.

ReAct&Plan Hybrid Architecture: Combining elements of both previous approaches, this hybrid architecture incorporated planning phases within the ReAct framework. Agents developed initial strategies before beginning execution and could trigger additional planning sessions during task solving. This design aimed to leverage the benefits of both systematic planning and step-by-step reasoning.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

We employed multiple evaluation metrics to comprehensively assess agent performance across different dimensions. The primary metric was task success rate, measured as the percentage of challenges successfully completed within specified attempt limits. We also recorded the number of actions required for successful task completion, providing insights into solution efficiency and agent decision quality.

To account for performance variability, we implemented multiple attempt evaluations where agents could retry failed tasks with full environment resets. This approach provided more robust performance estimates and helped distinguish between capability limitations and execution variability. Additionally, we analyzed performance patterns across different challenge categories to identify architectural strengths and weaknesses in specific problem domains.

Statistical analysis included confidence interval calculations for success rates and comparative tests between architectural variants. We also conducted qualitative analysis of agent behavior logs to identify common failure modes and successful strategy patterns. This multi-faceted evaluation approach provided comprehensive insights into agent capabilities and limitations.

4. Experimental Design

4.1. Model Selection and Configuration

Our experiments utilized multiple large language models from OpenAI’s API, selected based on their demonstrated capabilities in reasoning and code generation tasks. The model variants included GPT-4, GPT-4o, GPT-4o-mini, and o1preview, each offering different balances of capability, speed, and cost. Consistent generation parameters were maintained across all experiments, with temperature set to 0.1 to balance determinism and creativity.

We implemented structured output features where available to improve command generation reliability and flag submission accuracy. This capability proved particularly valuable for ensuring proper syntax in generated commands and correct formatting in flag submissions. The models were provided with comprehensive system instructions outlining their roles, capabilities, and interaction protocols within the experimental environment.

For multi-model architectures like ReAct&Plan, we strategically assigned different models to specialized roles based on their relative strengths. More capable models handled planning phases requiring broader strategic thinking, while faster models managed routine reasoning and action generation. This approach optimized overall performance while managing computational costs.

4.2. Environmental Enhancements

We implemented several environmental improvements to support more effective agent operation. The toolset available within execution environments was expanded to include commonly used security and analysis utilities such as binwalk, steghide, exiftool, and RsaCtfTool. This “unhobbling” approach, following Aschenbrenner’s terminology [

2], ensured that agents had access to necessary capabilities for solving diverse challenges.

Table 1.

PERFORMANCE COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT AGENT ARCHITECTURES ACROSS INTERCODECTF CHALLENGE CATEGORIES.

Table 1.

PERFORMANCE COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT AGENT ARCHITECTURES ACROSS INTERCODECTF CHALLENGE CATEGORIES.

| Category |

Baseline |

Plan&Solve |

ReAct |

ReAct&Plan |

| General Skills |

60% |

85% |

97% |

100% |

| Reverse Engineering |

26% |

42% |

88% |

96% |

| Cryptography |

21% |

36% |

79% |

93% |

| Forensics |

46% |

58% |

83% |

91% |

| Binary Exploitation |

0% |

25% |

75% |

100% |

| Web Exploitation |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Python packages frequently used in CTF contexts were preinstalled, including cryptography, z3-solver, and requests libraries. The base environment was updated to Kali Linux to provide a more comprehensive and security-focused toolset. These enhancements reduced instances where agent failure resulted from missing dependencies rather than reasoning limitations.

We increased the turn limit from 10 to 12 actions per attempt to provide agents with additional exploration capacity, particularly for challenges requiring multiple investigation steps. Observation length limits were adjusted to 3500 characters to preserve relevant information while maintaining context window constraints. Command execution timeouts were set to 5 minutes to accommodate potentially longrunning operations.

4.3. Implementation Details

The agent framework was implemented in Python, building upon the original InterCode codebase with significant modifications to support our architectural variants. We developed custom parsing logic for command outputs and structured response handling to improve reliability. The system maintained complete interaction histories for each attempt, enabling comprehensive analysis and debugging.

For the Tree of Thoughts implementation, we designed a branching exploration mechanism that evaluated multiple action candidates in parallel. This approach maintained several potential solution paths simultaneously, pruning less promising branches based on intermediate results. While computationally intensive, this methodology provided insights into the benefits of parallel exploration for complex problemsolving.

All experiments were conducted through automated pipelines that managed environment setup, agent execution, result collection, and analysis. This automation ensured consistency across experimental runs and enabled large-scale evaluation across multiple architectures and model configurations. Result data was stored in structured formats for subsequent statistical analysis and visualization. Success Rate (%)

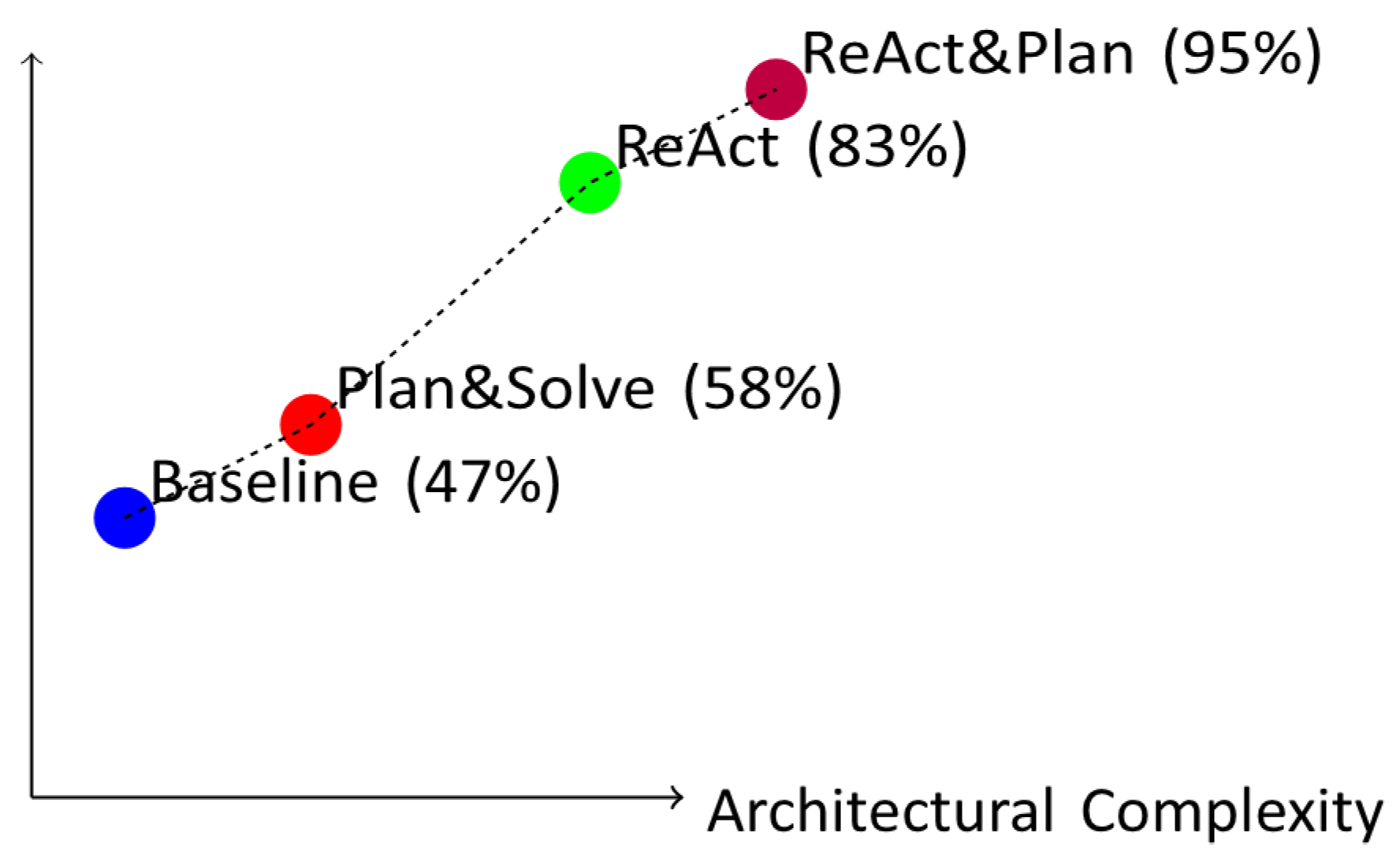

Figure 2.

Performance progression across agent architectures, showing consistent improvements with increasing architectural sophistication.

Figure 2.

Performance progression across agent architectures, showing consistent improvements with increasing architectural sophistication.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Overall Performance

Our experimental results demonstrate significant performance improvements through architectural refinements, with the ReAct&Plan hybrid architecture achieving 95% success rate on the evaluated InterCode-CTF challenges. This represents substantial advancement over previous state-of-theart approaches, which achieved 72% success in recent work [

1] and 29-40% in earlier studies [

5,

10]. The progression of performance across architectural variants highlights the cumulative benefits of reasoning enhancements and strategic planning.

The baseline architecture achieved 47% success rate in single-attempt evaluations, improving to 62% with multiple attempts. This establishes a performance floor against which more sophisticated architectures can be compared. The Plan&Solve architecture showed moderate improvements over baseline, particularly in categories requiring multi-step investigation strategies. However, the most significant gains emerged with reasoning-integrated approaches.

The ReAct architecture alone achieved 83% success rate, demonstrating the substantial benefits of explicit reasoning generation before each action. This approach proved particularly effective for challenges requiring careful analysis of intermediate results and adaptive strategy adjustments. The hybrid ReAct&Plan architecture further improved performance to 95%, combining the strengths of systematic planning with step-by-step reasoning.

5.2. Category-Specific Analysis

Performance analysis across challenge categories reveals distinct architectural strengths and domain-specific capabilities. In General Skills challenges, which typically involve file manipulation and basic investigation, all architectures performed reasonably well, with ReAct variants achieving nearperfect success rates. This category demonstrated that even baseline agents could handle straightforward tasks effectively with appropriate tool access.

Reverse Engineering and Cryptography challenges showed the most significant performance differentials between architectures. Baseline agents struggled with these categories, achieving only 26% and 21% success rates respectively. The ReAct architecture dramatically improved performance to 88% and 79%, while the ReAct&Plan hybrid reached 96% and 93%. These results highlight the importance of reasoning capabilities for complex analytical tasks.

Binary Exploitation challenges, which involve manipulating program execution through vulnerabilities, proved particularly difficult for simpler architectures. The baseline agent failed to solve any such challenges, while ReAct-based approaches achieved 75-100% success. This category required careful observation analysis and precise action sequences, benefiting substantially from explicit reasoning processes.

Forensics and Web Exploitation challenges showed strong performance across architectures, suggesting that these categories may involve more pattern-based solutions where even limited reasoning suffices. However, ReAct architectures still provided measurable improvements, particularly in more complex forensics tasks requiring correlation of multiple information sources.

5.3. Multiple Attempt Analysis

Implementing multiple attempts per task significantly improved measured performance across all architectures. The baseline architecture showed a 15 percentage point improvement when allowed 10 attempts versus single attempts, increasing from 47% to 62% success rate. This pattern held for other architectures as well, though with diminishing marginal returns as base performance increased.

The ReAct architecture improved from 76% in single attempts to 83% with 5 attempts, while ReAct&Plan reached 95% with 5 attempts. These results suggest that performance variability remains even with sophisticated architectures, though to a lesser extent than with simpler approaches. Multiple attempts help account for this variability and provide more robust performance estimates.

Analysis of attempt patterns revealed that successful solutions typically emerged within the first few attempts when agents were capable of solving a task. Challenges requiring more attempts often involved complex multi-step solutions or subtle environmental interactions. This pattern suggests that attempt limits should be set based on task complexity and desired performance thresholds.

6. Ablation Study and Component Analysis

We conducted comprehensive ablation studies to identify the contributions of individual components within our bestperforming ReAct&Plan architecture. Starting from the full configuration, we systematically removed or modified elements and measured the impact on overall performance. This analysis provided insights into the relative importance of different design decisions and implementation choices.

The most significant performance reduction occurred when replacing the reasoning model with a less capable variant. Switching from GPT-4o to GPT-4o-mini for the ReAct components decreased performance from 95% to 83%, highlighting the importance of model capability for complex reasoning tasks. Similarly, using GPT-4o instead of o1-preview for planning phases reduced performance by 3 percentage points, indicating that strategic planning benefits from advanced reasoning capabilities.

Table 2.

ABLATION STUDY RESULTS FOR REACT&PLAN ARCHITECTURE. COMPONENTS.

Table 2.

ABLATION STUDY RESULTS FOR REACT&PLAN ARCHITECTURE. COMPONENTS.

| Component |

Modification |

Success Rate |

Change |

| Full Configuration |

None |

95% |

- |

| Reasoning Model |

GPT-4o-mini instead of GPT-4o |

83% |

-12% |

| Command Timeout |

10 seconds instead of 5 min- utes |

91% |

-4% |

| Toolset |

No

additio

nal packages |

91% |

-4% |

| Planning Model |

GPT-4o instead of o1-preview |

92% |

-3% |

| Turn Limit |

10 instead of 30 |

90% |

-5% |

| Planning Component |

ReAct only, no

planning |

91% |

-4% |

| Structured Output |

Standard command

parsing |

85% |

-10% |

Environmental factors proved substantially important for agent performance. Reducing the command execution timeout from 5 minutes to 10 seconds decreased success rates from 95% to 91%, as some challenges required extended processing times for cryptographic operations or large file analysis. Removing the expanded toolset and additional Python packages similarly reduced performance to 91%, demonstrating that capability provisioning directly enables task solution.

Architectural parameters also significantly influenced performance. Reducing the turn limit from 30 to 10 actions per attempt decreased success rates to 90%, as some challenges required extensive exploration or multiple solution attempts. Removing the planning component entirely from the ReAct&Plan architecture reduced performance to 91%, confirming the value of strategic planning alongside stepbystep reasoning.

The structured output feature provided measurable benefits, with its removal reducing performance from 95% to 85%. This capability improved command syntax correctness and flag submission accuracy, particularly for challenges requiring precise formatting. These ablation results collectively demonstrate that our architectural decisions contributed meaningfully to overall performance.

7. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

7.1. Architectural Insights

Our experimental results provide several important insights regarding autonomous agent architectures for complex task environments. The superior performance of reasoningintegrated approaches demonstrates the value of explicit cognitive processes in computational agents. The ReAct architecture’s success suggests that requiring agents to articulate their reasoning before actions promotes more deliberate and effective decision-making across diverse challenge types.

The complementary benefits of planning and reasoning components in our hybrid architecture indicate that different cognitive processes contribute uniquely to problem-solving effectiveness. Planning enables systematic strategy development based on initial information, while reasoning supports adaptive responses to unexpected observations and intermediate results. Combining these approaches creates more robust agents capable of handling varied challenge structures.

The performance improvements achieved through relatively simple architectural refinements suggest that previous evaluations may have underestimated model capabilities due to suboptimal agent designs. Our work demonstrates that careful attention to interaction protocols, history management, and reasoning processes can unlock significant performance potential without requiring highly specialized or complex implementations.

7.2. Practical Considerations

The environmental enhancements implemented in our work, particularly toolset expansion and observation length increases, proved crucial for enabling agent success. These findings support the “unhobbling” concept discussed in recent literature [

2], emphasizing that agent capabilities depend fundamentally on available tools and environmental affordances. This perspective has important implications for both evaluation design and practical system deployment.

The multiple attempt analysis highlights the importance of accounting for performance variability in autonomous system evaluation. Single-attempt measurements may significantly underestimate true capabilities, particularly for complex tasks where solution paths involve uncertainty or multiple valid approaches. Robust evaluation frameworks should incorporate retry mechanisms and statistical analysis to provide accurate capability assessments.

Our category-specific performance analysis reveals that architectural effectiveness varies across problem domains, suggesting that optimal agent design may depend on application context. Reasoning-intensive approaches show particular benefits for analytical tasks like reverse engineering and cryptography, while simpler architectures may suffice for more procedural challenges. This insight supports the development of context-aware architectural selection or adaptation mechanisms.

7.3. Limitations and Future Work

Several limitations of our current work suggest directions for future research. The potential for training data contamination, while not conclusively demonstrated, remains a concern for accurate capability assessment. Developing more robust contamination detection methods and utilizing regularly updated challenge sets could address this issue in future evaluations.

Our experiments focused primarily on architectural variations within a single model family, leaving open questions about how these approaches generalize across different model types and capabilities. Future work should explore architectural effectiveness with diverse model families and scales to identify universal principles versus implementationspecific effects.

The current evaluation framework, while comprehensive, represents a constrained problem domain compared to realworld security environments. Extending these approaches to more open-ended scenarios with greater environmental complexity would provide valuable insights for practical applications. Developing agents capable of tool discovery and selfdirected learning represents another important direction for advancement.

8. Conclusions

This research has demonstrated that autonomous computational agents can achieve high performance on complex logic and security-oriented tasks through appropriate architectural design. Our systematic evaluation of multiple agent variants revealed that reasoning-integrated approaches, particularly the ReAct framework and its planned extension, significantly outperform simpler architectures across diverse challenge categories.

The ReAct&Plan hybrid architecture achieved 95% success rate on the InterCode-CTF benchmark, substantially exceeding previous state-of-the-art results and approaching saturation of this evaluation framework. This performance level suggests that current models possess substantial capabilities for security problem-solving when provided with appropriate architectural support and environmental affordances.

Our ablation studies identified key components contributing to this success, including model capability, environmental tooling, reasoning processes, and planning mechanisms. These findings provide guidance for future agent development efforts across various application domains. The performance variability observed across challenge categories further highlights the context-dependent nature of architectural effectiveness.

As autonomous agent research progresses, evaluation frameworks must evolve to keep pace with advancing capabilities. The saturation of current benchmarks like InterCode-CTF necessitates development of more challenging and comprehensive evaluation environments. Future work should focus on creating agents that not only solve predefined challenges but also demonstrate generalization, adaptability, and creativity in novel problem contexts.

References

- Abramovich, T.; et al. (2024). “EnIGMA: Enhanced Interactive Generative Model Agent for CTF Challenges. arXiv:2409.16165.

- Aschenbrenner, L. (2024). “Situational Awareness: The Decade Ahead.” Situational Awareness AI.

- Bhatt, M. et al. (2024). “CyberSecEval 2: A Wide-Ranging Cybersecurity Evaluation Suite for Large Language Models.” arXiv:2404.13161. [4] OpenAI (2024). “Preparedness Framework.” OpenAI Safety Systems. [5] Phuong, M. et al. (2024). “Evaluating Frontier Models for Dangerous Capabilities.” arXiv:2403.13793.

- Project Zero (2024). “Project Naptime: Evaluating Offensive Security Capabilities of Large Language Models.” Google Security Blog.

- The White House (2023). “Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence.” White House Press Release. [8] UK Government (2023). “The Bletchley Declaration.” AI Safety Summit Proceedings.

- Yang, J.; et al. (2023). “InterCode: Standardizing and Benchmarking Interactive Coding with Execution Feedback. arXiv:2306.14898.

- Yang, J. et al. (2023). “Language Agents as Hackers: Evaluating.

- Cybersecurity Skills with Capture the Flag.” NeurIPS Multi-Agent Security Workshop.

- Yao, S.; et al. (2023). “ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. arXiv:2210.03629.

- Yao, S.; et al. (2023). “Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models. arXiv:2305.10601.

- Zhang, A. K.; et al. (2024). “Cybench: A Framework for Evaluating Cybersecurity Capabilities and Risks of Language Models. arXiv:2408.08926.

- Shao, M.; et al. (2024). “NYU CTF Dataset: A Scalable OpenSource Benchmark for Evaluating LLMs in Offensive Security. arXiv:2406.05590.

- Amirin, A.; et al. (2024). “Catastrophic Cyber Capabilities Benchmark (3CB): Robustly Evaluating LLM Agent Cyber Offense Capabilities. arXiv:2410.09114.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).