1. Introduction

On December 31, 2019, Wuhan city in China reported an outbreak of COVID-19 due to a new Coronavirus, later named SARS-CoV-2 [

1,

2]. This latter has quickly spread worldwide and led the WHO to declare the Covid-19 as a pandemic in March 2020 [

3]. Due to important number of cases recorded worldwide, tremendous challenges arose regarding diagnostic tools availability, accessibility, and distribution. If the Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) is still the reference standard for SARS-CoV-2, tool’s high cost, technical requirements, and low availability hinders its use in poor resource settings such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) [

4,

5,

6].

At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, only three provinces—Kinshasa, Haut-Katanga, and Nord-Kivu— had molecular testing capacity in DRC. However, this laboratory capacity was quickly overloaded by massive influx of samples coming from either unserved provinces or numerous health facilities in Kinshasa. The oversaturation of testing capacity, especially in Kinshasa, the epicenter of the outbreak has led the Covid-19 response leadership to envision using alternative and/or complementary methods such as rapid antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Indeed, rapid antigen tests are cheaper, easy to handle, do not require sophisticated technical equipment, and reduces the turn-around time for results delivery to <30 minutes [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. They can alleviate the workload in the laboratories, allow quick decision-making and facilitate a large-scale testing, especially in remote areas [

12,

13,

14].

Over the course of the pandemic, the DRC Covid-19 response leadership has decentralized the diagnosis, including the use of RATs across different provinces, including in remote areas [

15]. However, the real impact of RATs use on health system and community has not yet been broadly evaluated, and their potential contribution to the SARS-CoV-2 epidemiological surveillance remains poorly documented to date in DRC.

Evaluating the contribution of RATs in strengthening the diagnosis and surveillance of active SARS-CoV-2 infection during the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to guide public health decision-making and inform response strategies, especially in resource-limited settings.

This study aims to describe the epidemiological and operational contribution of RATs in the management of COVID-19 cases in Kinshasa and to explore the associations between clinical symptoms or exposure factors and RATs positivity

The study is not comparative with RT-PCR data, although RATs were used in addition to this reference test during this period. Furthermore, evaluating diagnostic performance was not among the objectives of this work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Settings and Design

This cross-sectional and retrospective observational study was conducted in Kinshasa, the epicenter of Covid-19 pandemic in the DRC, from January 2021 to December 2022. This study was jointly implemented by the Kinshasa Health District Office and the Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale (INRB) as a part of the national epidemiological surveillance of SARS-CoV-2.

2.2. Population and Selection Criteria

We included consenting individuals temporarily or permanently living in Kinshasa who met following criteria: 1) responding to the WHO case definition for Covid-19 [

16], 2) having a close contact with a suspected case and/or confirmed case, 3) staying in a high-risk transmission area, and 4) providing biological sample for RAT analysis. We excluded any subject who did not either consent or provide a biological specimen.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Sociodemographic, clinical and epidemiological data were collected with EWARS® (Early Warning, Alert, and Response system) software based on the national case investigation form. Data were exported to Microsoft Excel 2016® (Microsoft, Redmon, WA, USA) for cleaning, and subsequently analyzed with STATA version 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas 77845 USA (IBM, New York, USA).

For descriptive analysis, we summarized sociodemographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics using frequency and percentages for categorial variables and means ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Epidemiological weeks were grouped by quarters to explore patterns.

In addition to the descriptive analyses, bivariate analysis using the Chi-square (χ²) test, with a p-value < 0.05 as statistically significant, were performed to assess the association between sociodemographic or clinical variables and RATs positivity. These analyses were not intended for comparative evaluation between diagnostic method (RAT and RT-PCR).

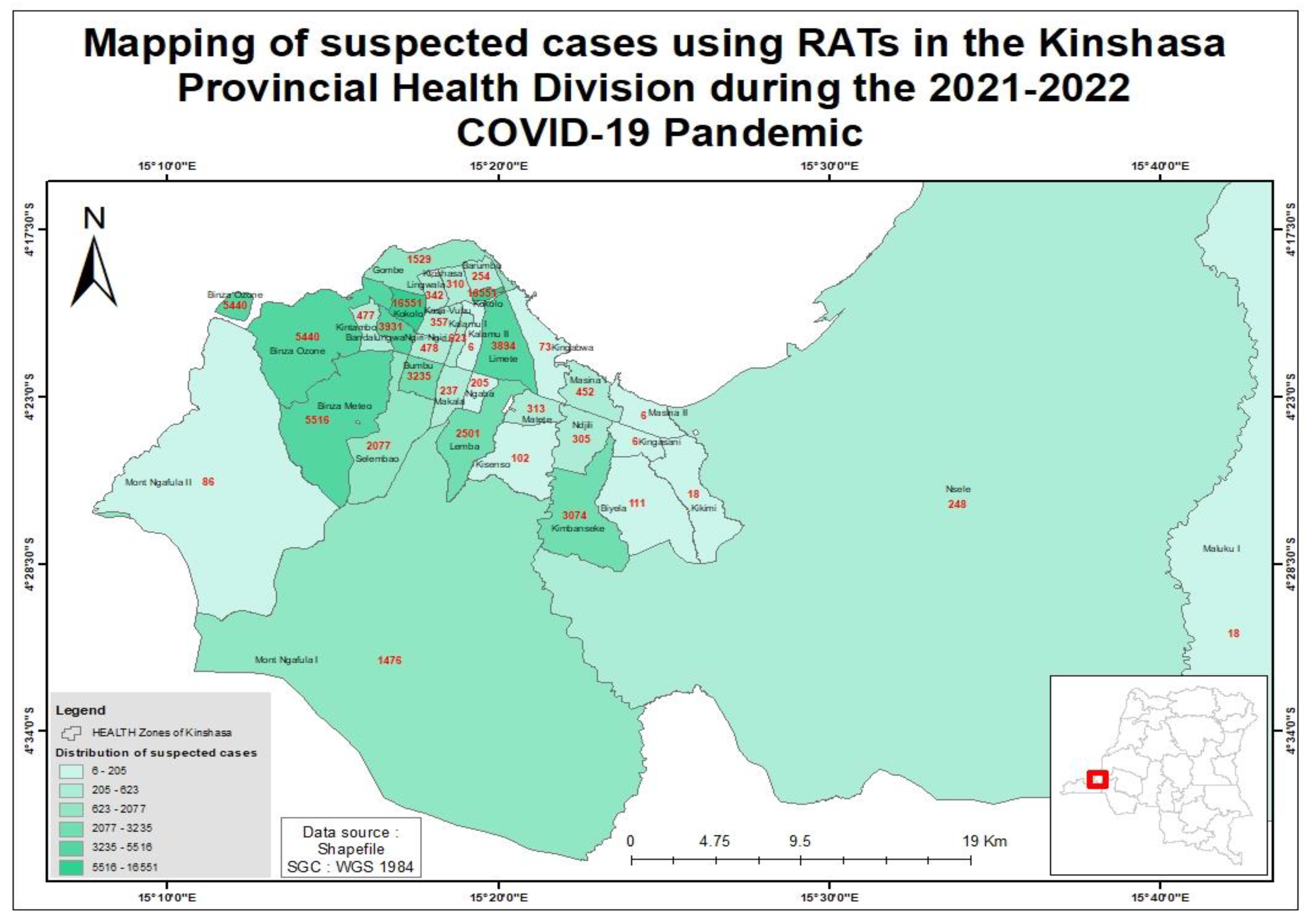

For the spatial analysis, the mapping of suspected cases and the implementation of RATs in Health Zones was performed using QGIS software (Quantum Geographic Information System, version 3.30).

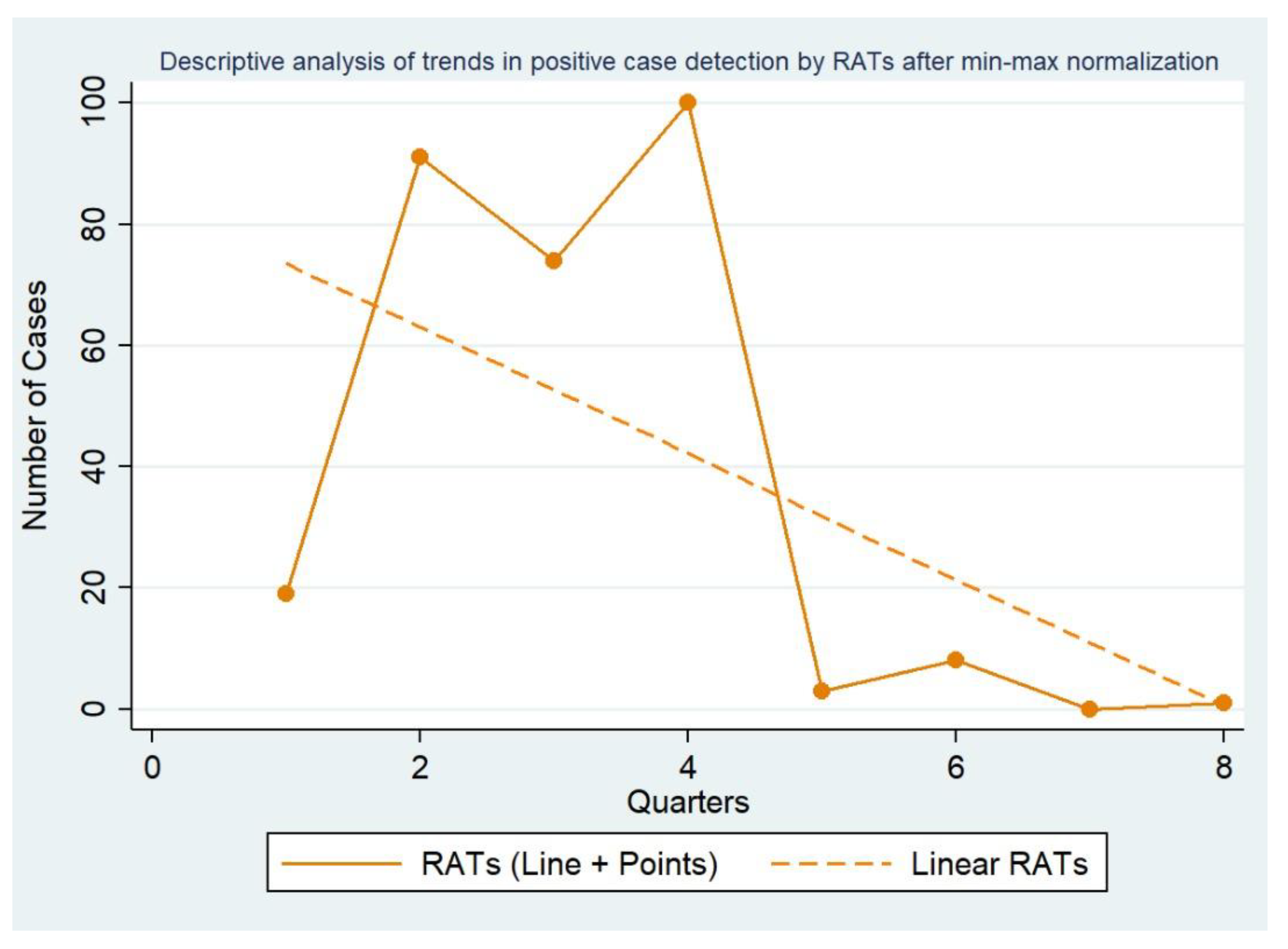

To facilitate the visualization of temporal patterns in RAT-based case detection across quarters, a linear multiplicative Min–Max scaling was applied to the quarterly RAT values. The Min–Max scaler rescaled each quarterly RAT value to the [0,1] interval using the formula :

This normalization was used excvlusively for graphical representation, given the large amplitude of raw values over time. Raw values remained the only source for descriptive summaries, and no inferential comparative or cross-modality analysis was conducted using normalized data.

2.4. Sample Collection and Laboratory Procedures

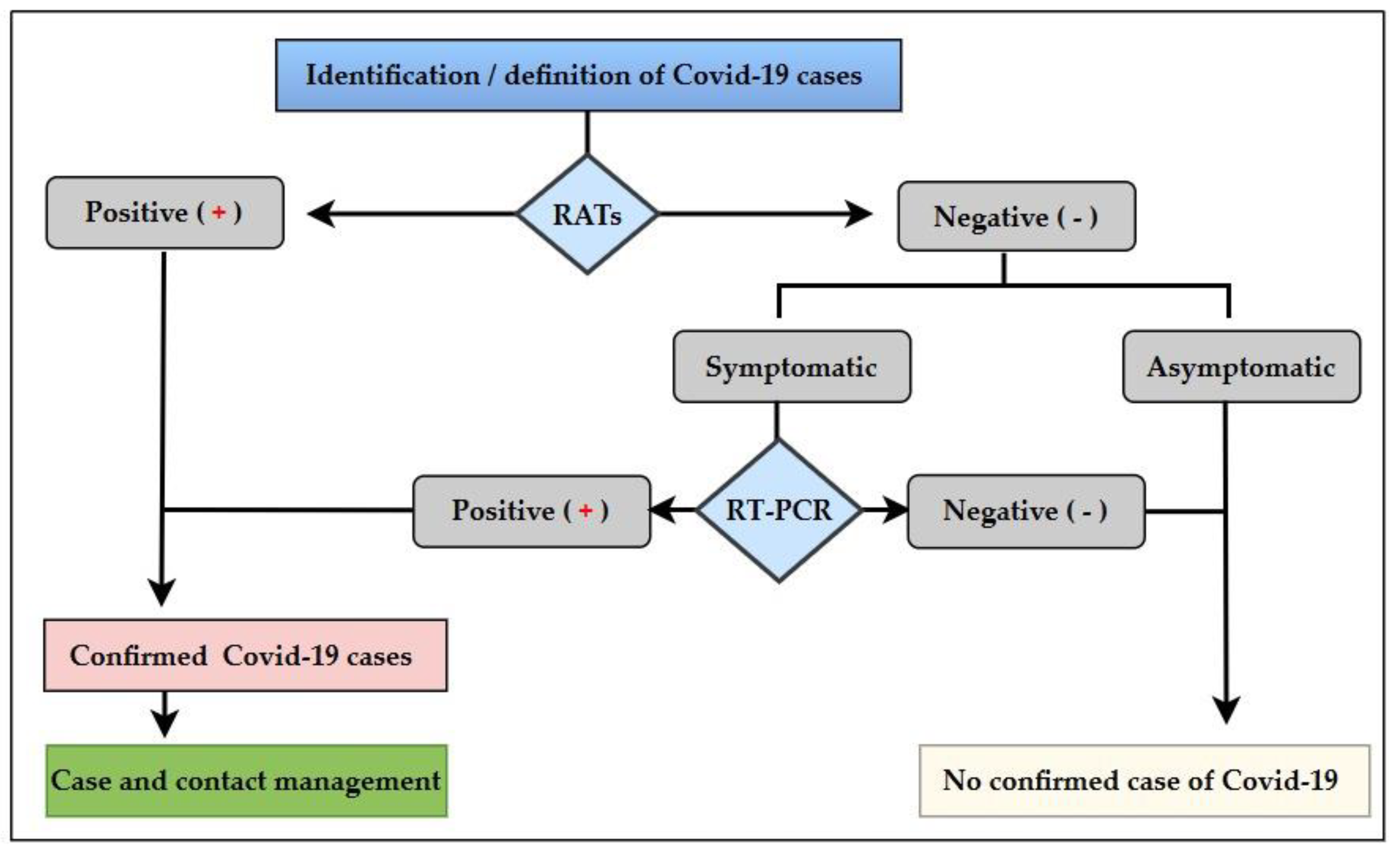

Before sample collection, healthcare workers from participating facilities received standardized training covering COVID-19 basics, nasopharyngeal sampling, packinging, storage, transportation, personal protective equipment(PPE) use, RATs procedure and result reporting through EWARS software (See

Figure 1).

Quality control was systematically performed for each kit batch using the positive and negative controls before field use, to ensure the reliability of the results.

Two nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at the healthcare facilities or mobile sampling sites. The first swab was used immediately onsite for RATs analysis and discarded. The second swab was placed into a 3 ml viral transport medium tube (MTV), temporarily stored at +4°C and transported to the INRB for molecular analysis within a maximum of 72 hours. We used two lateral flow assays for the qualitative detection of the SARS-CoV-2, the Panbio COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device

® (Abbott, Illinois, USA) and Standard Q COVID-19 Ag Test

® (SD Biosensor, Republic of Korea). Both RATs had previously been approved by the WHO, then validated for use at the country level [

17,

18,

19,

20].

The analysis and interpretation were in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The interpretation included individual's clinical picture, medical history, recent exposure, and RATs read.

The test was positive whenever two red bands appeared, one in the test zone (T) and the other in the control zone (C). The test was negative if a single red band appears in the control zone (C). The test was invalid if the control band was absent. Invalid tests were repeated within 30 minutes; samples with repeated invalid results were reported as invalid.

Symptomatic individuals with more than seven days of symptoms and a negative RAT result were referred for confirmatory RT-PCR. In our decision-making, we considered that a negative result did not rule out a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Therefore, RT-PCR was used as the gold standard, especially for suspect-cases with a negative RAT.

However, samples collected directly at RT-PCR testing sites were analyzed by RT-PCR without prior RAT.

For RT-PCR, viral RNA was extracted using the DaAnGene RNA/DNA Purification kit (DaAnGene Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, China). SARS-CoV detection targeted the Nucleic acid amplification and ORF1ab genes using the DaAnGene Detection kit for 2019-nCoV (PCR-Fluorescence)

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted as a part of the national Covid-19 response coordinated by the Secrétariat Technique du Comité Multisectoriel de Lutte contre la Covid-19. As such, formal ethical approval was not required; however, a formal letter of authorization was issued by the Health District Office (DPS) N°SM-700/CBCD/SEC/NM//037BCD/2023 and the Covid-19 response Incident Manager. Verbal informed consent and assent when applicable was obtained from for all participants’ prior for testing. Data were handheld in accordance with the national confidentiality and data protection regulations.

3. Results

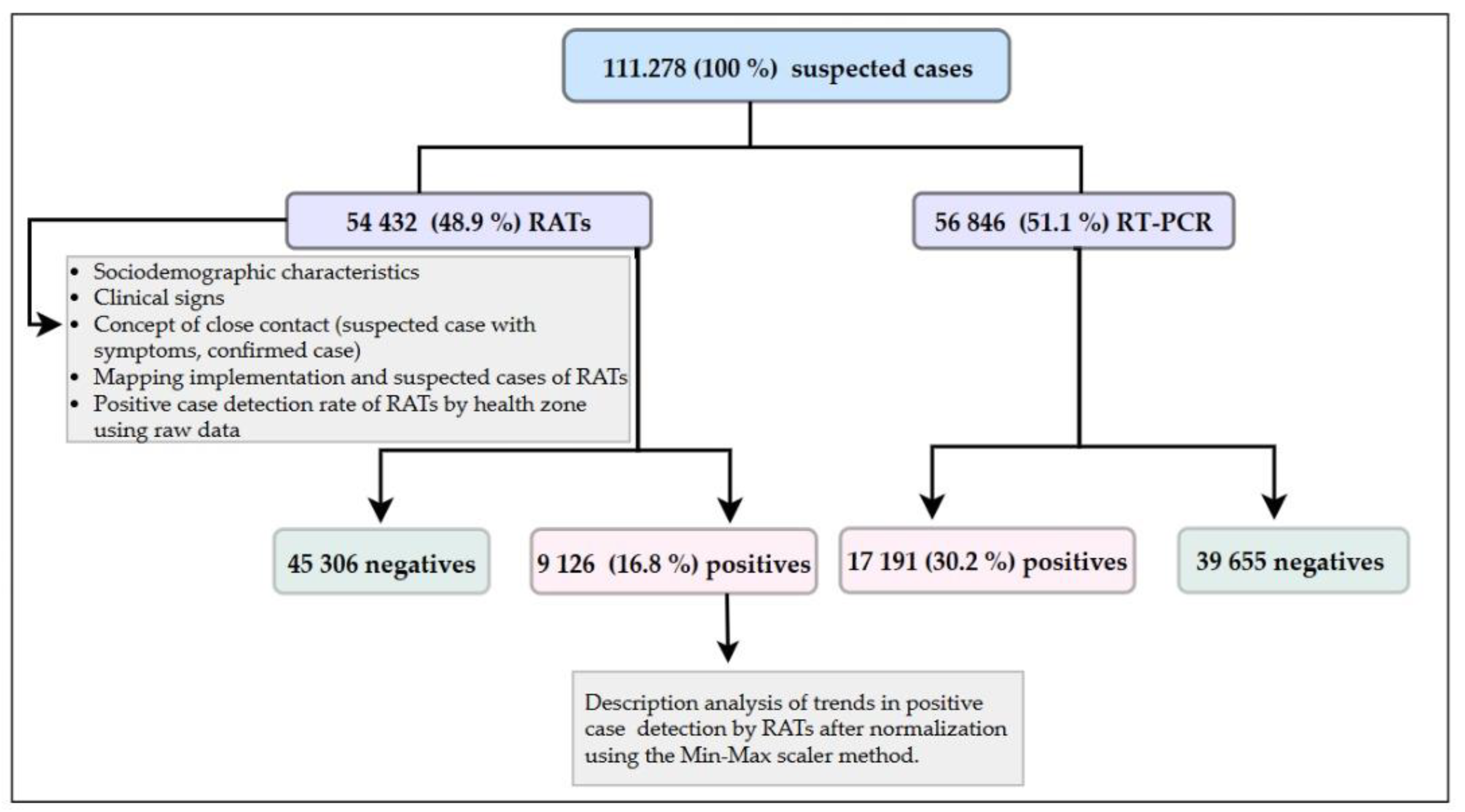

We tested 111 278 suspect-cases, among which 56 846 (51.1%) diagnosed by RT-PCR with a positivity rate of 30.2% (n=17,191); while 54 432 (48.9%) were tested by RATs, for a positivity rate of 16.8% (n=9 126) (

Figure 2). Of the 26 317 SARS-CoV-2 positive cases identified, 34.7% were detected by RATs and 65.3% by RT-PCR. Males represented 59 780 (53,7%) and females 51 498 (46,3%) of suspected cases. The estimated mean age was 36.9 15.9 years.

Among the 54 432 individuals testing using RATs, the 21–40 years’ age group was the most represented (n=27 221; 50%), followed by 41–60 years (n = 16 056; 29.5%), ≤ 21 years (n = 6 143; 11.3%), and ≥ 60 years (n = 5 012; 9.2%). The positivity rate decreased progressively with age, ranging from 19.1% in individuals ≤ 21 years to 13.8% in those ≥ 60 years.

Men represented 54,8% (n = 29 842), of those tested by RATs while women accounted for 45.2% (n=24 600). The positivity rate was 17.1% among women and 16.5% men, compared with women (45,2%). (

Table 1).

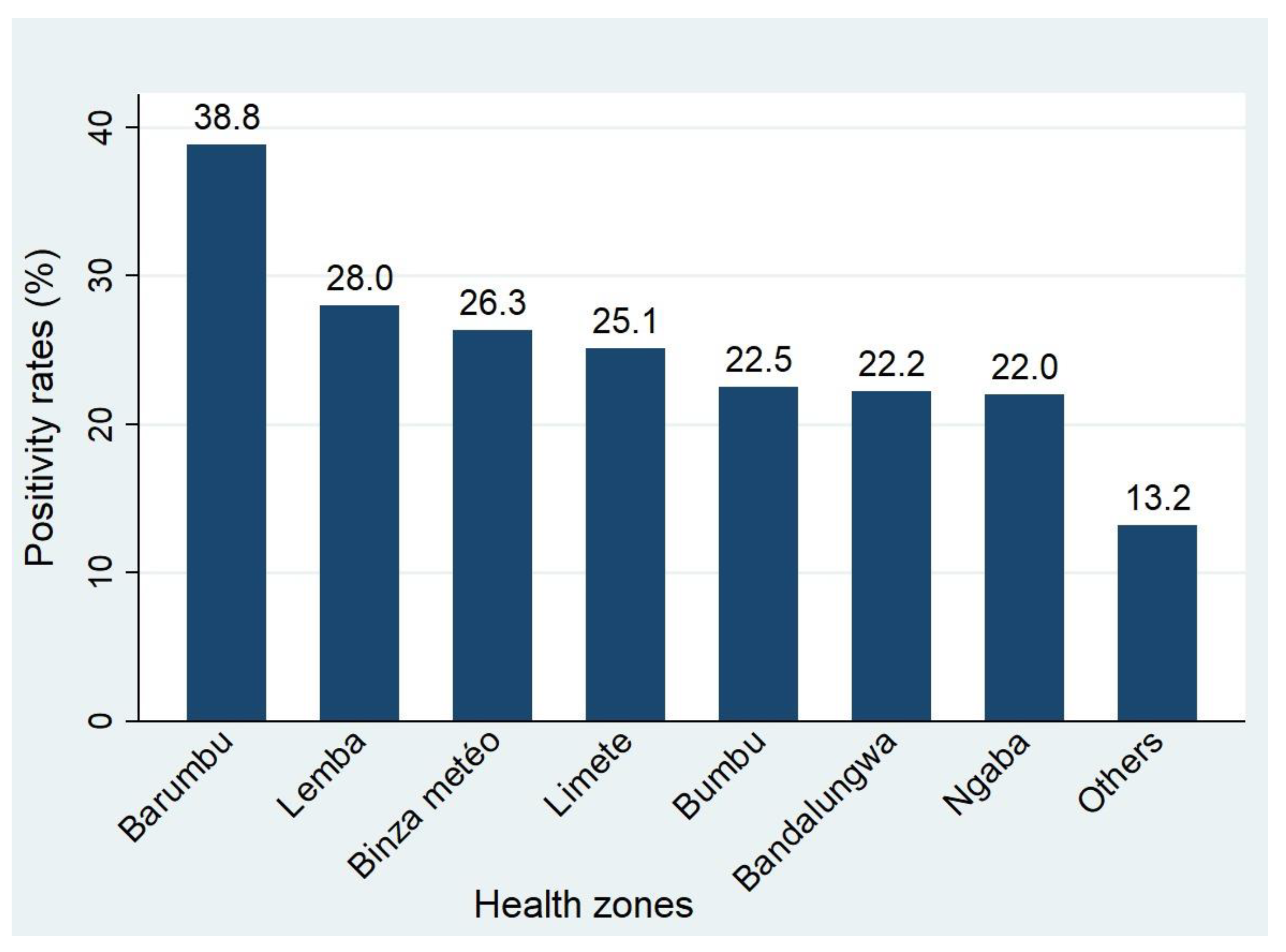

Most Health Zones in Kinshasa actively used RATs for SARS-CoV-2 screening. The RATs positivity rate considerably varied between Health Zones (

Figure 3 &

Figure 4). Health Zones reporting highest positivity rate were Barumbu (37.8%), Lemba (28.0%), Binza Météo (26.3%), Limete (25.1%), Bumbu (22.5%), Bandalungwa (22.2%) and Ngaba (22.0%) (

Figure 4).

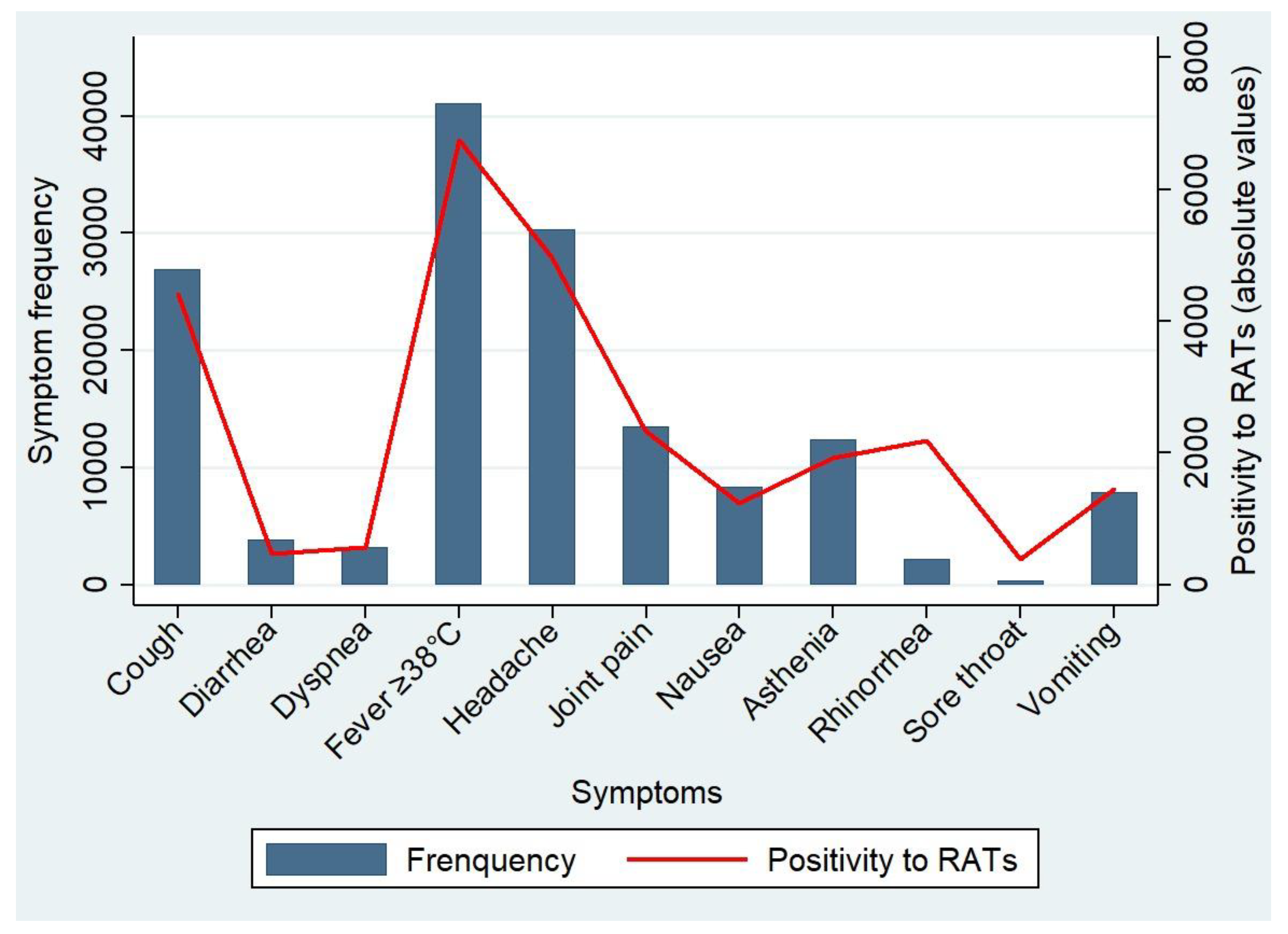

Symptoms frequently reported included fever (41,079, %), headache (30,307, %) and cough (26,931, %), with 6,759 (%), 4,959 (%), and 4,412 (%) of positives, respectively (

Figure 5).

The most frequently reported symptoms among RAT-tested individuals were fever (41 079 cases), headache (30 307 cases) and cough (26 931 cases). (

Figure 5).

Chi-square analyses demonstrated significant between several symptoms and RAT positivity (

Table 2).

Rhinorrhea was strongly associate with a positive RAT result (p = 0.001). In contrast dyspnea (χ² = 3.178; p = 0.075) were not significantly associated with positivity. Other symptoms, such as cough, sore throat, physical asthenia, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, join pain and fever, were significantly associated with positive tests (all p < 0.05).

Exposure history, whether contact with a symptomatic individual or with a confirmed COVID-19 case, was strongly associated with test positivity in our population (p < 0.001).

Individuals with a reported exposure showed COVID-19 positivity rates approximately two to three times higher than those without exposure, and this association was consistent across both sexes (

Table 2).

Quarterly trends RAT-based detection were visualized after Min–Max normalization, applied exclusively to facilitate graphical interpretation (

Figure 6). The normalized showed substantial fluctuations during the first four quarters, with notable peaks in the second and fourth quarters. These peaks align with the third and fourth waves of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the country. A pronounced and sustained decline was observed from the fifth quarter onward, with normalized values remaining consistently low through the eighth quarter, corresponding to the end of the epidemic period. The fitted linear trend demonstrates an overall downward trajectory in relative detection levels over time. Additionally, the residuals showed a progressive decrease across the observation sequence, indicating that the data are consistent with a decreasing linear multiplicative pattern. (

Figure 6). No statistical comparison or quantitative inference was performed on normalized data.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the operational and epidemiological contribution of RATs in decentralization of COVID-19 diagnosis in Kinshasa.

It did not assess diagnostic performance, making its data not directly comparable.The study also presents certain methodological limitations and biases that may have influenced the interpretation of the results.

Indeed, several confounding factors and selection biases were considered when analyzing data from the rapid antigen tests (RATs). Since most of the included subjects were symptomatic or identified as contacts of suspected or confirmed cases, the apparent sensitivity of rapid tests may have been overestimated, as viral load is generally higher in this population.

Conversely, the low proportion of asymptomatic individuals—particularly in areas with limited testing coverage—combined with logistical disparities between health zones and periodic stock shortages, limits the generalizability of the findings to the entire population of Kinshasa.

In addition, the successive emergence of different variants (Alpha, Delta, Omicron) represents another confounding factor influencing the average viral load. Individual clinical characteristics, such as age, vaccination status, and comorbidities, may also modulate viral load and, consequently, the likelihood of antigen detection.

Finally, the operational conditions at testing sites — including staff training, sample quality, and adherence to testing procedures — may have contributed to the variability observed in the results.It should also be noted that the study does not provide separate data on negative RAT results obtained from symptomatic COVID-19 cases that were referred for RT-PCR confirmation.

Most subjects tested were in the 21–40 age group. The highest positivity rate was observed in those aged ≤21 (19.1%), despite their low representation. This trend could be explained by high social mobility and lower compliance with preventive measures among young people, who are often asymptomatic but highly exposed. This highlights the importance of active inclusion of youth in testing strategy to curb transmission. Our trends are in line with most African studies, in which the population was young [

21].

We found more males in our study, although positivity rate was slightly higher in females. This finding could be explained by the role played by immunity (higher production of type 1 interferon and T lymphocytes), hormones (the protective role of oestradiol), and genetic (the double X chromosome) encoding for the SARS-CoV-2 S protein [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Symptoms frequently associated with a positive RATs included fever ≥ 38°C, headache, sore throat, rhinorrhea and asthenia. Several studies have also reported fever ≥ 38°C as the dominant symptom, followed by cough [

26,

27,

28]. Rhinorrhea showed a strong correlation with positivity of RATs. This could probably be linked to the disruption of the nasal microbiota induced by the virus [

29].

In contrast, dyspnea was not statistically associated with positivity, suggesting their lack of sensitivity for SARS-CoV-2 prediction. Of note, other chronic or acute respiratory affections could have also induced this symptom. Our results are consistent with findings from Nkwembe et al. [

30], who showed that SARS-CoV-2 accounted for only 19.2% of respiratory viruses detected during the pandemic, suggesting a possible underestimation of other respiratory aetiologies.

The use of RATs has become widespread in almost all health zones (HZ) in Kinshasa. This large-scale use testifies the extent of the decentralization strategy for Covid-19 diagnosis, which has 1) brought the diagnostic tool close to the community, 2) decreased the workload on reference laboratories, and 3) prompted the rapid implementation of medical countermeasures in line with WHO recommendations [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. This strategy has also improved the quality and completeness of surveillance data, thereby limiting the risks of under-detection and the spread of the virus. Indeed, each undiagnosed case can lead to several infections in the absence of adequate countermeasures [

31,

32,

33].

The Barumbu health zone recorded the highest positivity rate with RATs (37.8%). This situation could be explained by its proximity to the Gombe township, the initial epicenter of the pandemic in Kinshasa, from where transmission has spread to adjacent areas.

Our data showed that 54,432 suspected cases (48.9%) were tested with RATs. Our RATs use rate is close to that observed in France in 2021 (49%) during the initial rollout of these tests, before reaching 61% in 2022 due to the intensification of screening [

34]. This proportion reflects the significant augmentation of screening access, especially in a limited resources setting.

Their use as a first-line test has enabled rapid detection, quick public-health decision making to streamline response actions, including in remote areas. Our findings support that RATs can be useful as a screening tool in facilities without RT-PCR capacity. However, their poor performance suggests that they should be used as a complementary tool to the RT-PCR, particularly to confirm negative cases during outbreak context. This strategy clearly ensures the reliability of the diagnosis and reduces the risk of false negatives.

The analysis of the temporal and spatial trends in SARS-CoV-2 positive case detection after normalization of quarterly data demonstrated the significant contribution of RATs to epidemiological surveillance, particulary during the third and fourth waves of the epidemic. They remained active until the end of the epidemic in our country.

Our findings are consistent with Jeanne-Marie Dozol data, in which large-scale testing showed high effectiveness of RATs [

34].

Nonetheless, non-pharmaceutical and pharmaceutical measures (masks, social distancing, hand hygiene, limiting gatherings, vaccination) also played a crucial role in the disease control, as shown in several studies [

35,

36,

37].

However, due to its originality, this research work has several strengths that automatically make it indisputably strong.

It covers a broad geographical area, within a relatively long timeframe, and over several Covid-19 waves. Therefore, our findings reinforce the study representativeness and robustness. This study has highlighted the role played by field data collected in real time to support the implementation of RATs. It also provides accurate operational characteristics of RATs use in outbreak settings, with highly valuable data generated to guide decision-making during emergencies. This study provides essential information for limited resources settings in support to the decentralization of diagnostic tools. Study findings can also guide future screening strategies during outbreaks and other emergencies.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated broad geographical and temporal coverage of RATs in all health zones under the jurisdiction of the Kinshasa Provincial Health Department (DPS), and spanned a long period covering several successive epidemic waves.

It accurately reflects not only operational practices in a health crisis context, but also the diagnostic value of taking into account symptoms and contact tracing. This makes its results extremely valuable in guiding public health policy decisions in emergency situations, with a view to breaking the chain of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 or other exponentially spreading diseases.

The evaluation of the strategy of decentralizing diagnosis through the use of RATs has provided concrete data that can be transposed to other contexts facing similar difficulties in accessing RT-PCR. It thus helps to guide future testing strategies in the event of a resurgence of COVID-19 or the emergence of new respiratory threats for countries with limited resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Boniface Kaputa Kabala, Steve Ahuka Mundeke and Edith Nkwembe Ngabana; Methodology: Boniface Kaputa Kabala, Daniel Mukadi Bamuleka, Julien Neze Sebakunzi, Arthur Tshimuanga Kabuamba and Edith Nkwembe Ngabana; Formal analysis: Boniface Kaputa Kabala, Julien Neze Sebakunzi, Steve Ahuka Mundeke and Edith Nkwembe Ngabana; Investigation: Boniface Kaputa Kabala, Fiston Mboma Matalampaka, Delphine Mbonga Mande, Lisa Lebo Nsimba, Youdhie Ituneme N’kaflabo, François Kahwata Mawika; Resources: Boniface Kaputa Kabala, Steve Ahuka Mundeke and Edith Nkwembe Ngabana; Writing original draft preparation: Boniface Kaputa Kabala and Edith Nkwembe Ngabana; Data curation: Boniface Kaputa Kabala and Edith Nkwembe Ngabana; Writing review & editing: Daniel Mukadi Bamuleka, Julien Neze Sebakunzi, Arthur Tshimuanga Kabuamba, Trésor Kabeya Mampuela, Jean Paul Kompany Kisenzele, Juslin Ntambwe Kaneyi, Steve Ahuka Mundeke, Edith Nkwembe Ngabana; Visualization: Boniface Kaputa Kabala; Administration of the response: Secrétariat du Comité Multisectoriel de la Riposte contre la Covid-19 and Health District Office (DPS) of Kinshasa; Supervision: Steve Ahuka Mundeke and Edith Nkwembe Ngabana. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the International Research Platform on Global Health DR CONGO (PRISME/DRC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted as a part of the Covid-19 response led by the Secrétariat Technique du Comité Multisectoriel de la Riposte contre la Covid-19. Therefore, it did not require an ethical approval, though a formal letter of authorization was issued by the Health District Office (DPS) of Kinshasa and the Incident Manager of the Covid-19 response.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent and assent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors. However, additional questions relating to the data can be addressed to us if necessary.

Acknowledgments

We would like to wholeheartedly thank the authorities of the Kinshasa Provincial Health Division for agreeing to grant us permission to conduct our study within its jurisdiction. To the incident manager of the Multisectoral Covid-19 Response Committee and its Committee for granting us access to the database. To the Microbiology Department of the Kinshasa University Clinics and Dr. Nestor Mukinay Dizal for their scientific advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otshudiema, J.O.; Folefack, G.L.T.; Nsio, J.M.; Mbala-Kingebeni, P.; Kakema, C.H.; Kosianza, J.B.; et al. Epidemiological Comparison of Four COVID-19 Waves in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, March 2020–January 2022. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansourabadi, A.H.; Sadeghalvad, M.; Mohammadi-Motlagh, H.R.; Amirzargar, A. Serological and Molecular Tests for COVID-19: a recent update. Iran. J. Immunol. 2021, 18, 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jayamohan, H.; Lambert, C.J.; Sant, H.J.; Jafek, A.; Patel, D.; Feng, H.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: a review of molecular diagnostic tools including sample collection and commercial response with associated advantages and limitations. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Tests diagnostiques pour le dépistage du SARS-CoV-2 : Orientations provisoires 11 septembre 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/335724 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Détection des antigènes à l’aide de tests immunologiques rapides pour le diagnostic de l’infection à SARS-CoV-2, Orientations provisoires 11 septembre 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/antigen-detection-in-the-diagnosis-of-sars-cov-2infection-using-rapid-immunoassays (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Antigen Detection in the Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 Infection; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clop, G. Impact du test antigénique de dépistage rapide du SARS-CoV2 sur le temps de passage des patients atteints de Covid-19 dans un service d’urgence. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 2022; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mukadi-Bamuleka, D.; Bulabula-Penge, J.; Jacobs, B.K.M.; De Weggheleire, A.; Edidi-Atani, F.; Mambu-Mbika, F.; et al. Head-to-head comparison of diagnostic accuracy of four Ebola virus disease rapid diagnostic tests versus GeneXpert® in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo outbreaks: a prospective observational study. EBioMedicine 2023, 91, 104568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadi-Bamuleka, D.; Bulabula-Penge, J.; De Weggheleire, A.; Jacobs, B.K.M.; Edidi-Atani, F.; Mambu-Mbika, F.; et al. Field performance of three Ebola rapid diagnostic tests used during the 2018–20 outbreak in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo: a retrospective, multicenter observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Orientations pour la lutte anti-infectieuse dans les établissements de soins de longue durée dans le contexte de la COVID-19, Orientations provisoires 21 mars 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331642/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC_long_term_care-2020.1-fre.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Orientations pour la lutte anti-infectieuse dans les établissements de soins de longue durée dans le contexte de la Covid-19, orientations provisoires 8 janvier 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/338935 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Prevention, Identification and Management of Health Worker Infection in the Context of COVID-19; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-336265 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- République Démocratique du Congo, Ministère de la Santé, Hygiène et Prévoyance sociale, Comité Multisectoriel de la lutte contre la COVID-19 RDC. Procédures opérationnelles de la Surveillance Épidémiologique de la COVID-19 centrée sur la Recherche active des cas, de la détection précoce des alertes et des cas suspects, à l’isolement et prise en charge médicale rapide des cas confirmés et au suivi des contacts, Décembre 2020; Ministère de la Santé: Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 Case Definition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-Surveillance_Case_Definition-2020.2 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Agulló, V.; Fernandez-González, M.; Ortiz de la Tabla, V.; Gonzalo-Jiménez, N.; García, J.A.; Masiá, M.; Gutiérrez, F. Evaluation of the rapid antigen test Panbio COVID-19 in saliva and nasal swabs in a population-based point-of-care study. J. Infect. 2020, 82, 186–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, A.; Baró, B.; Ouchi, D.; Rodó, P.; Ubals, M.; Corbacho-Monné, M.; et al. Analytical and clinical performance of the panbio COVID-19 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic test. J. Infect. 2021, 82, 186–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Revue rapide sur les tests de détection antigénique du virus SARS-CoV-2; Haute Autorité de Santé: Saint-Denis, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Évaluation de l’intérêt des tests antigéniques rapides sur le prélèvement nasal pour la détection du virus SARS-CoV-2 (Méta-analyse); Haute Autorité de Santé: Saint-Denis, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Hardy, É.J.L.; Flori, P. Spécificités épidémiologiques de la COVID-19 en Afrique : préoccupation de santé publique actuelle ou future ? Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2020, 79, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pison, G.; Meslé, F. La Covid-19 plus meurtrière pour les hommes que pour les femmes. Popul. Sociétés 2022, 598, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornfleth, I.; Kutschka, A.; Gardemann, B.; Isermann, B.; Goette, A. Protective regulation of the ACE2/ACE gene expression by estrogen in human atrial tissue from elderly men. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhard, C.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Neuhauser, H.K.; Morgan, R.; Klein, S.L. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaçais, L.; Richier, Q. COVID-19 : caractéristiques cliniques, biologiques et radiologiques chez l’adulte, la femme enceinte et l’enfant. Une mise au point de la pandémie. Rev. Med. Interne 2020, 41, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.J.; Schwartz, N.G.; Tobolowsky, F.A.; et al. Symptom Screening at Illness Onset of Health Care Personnel With SARS-CoV-2 Infection in King County, Washington. JAMA 2020, 323, 2087–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yombi, J.C.; De Greef, J.; Marsin, A.S.; Simon, A.; Rodriguez-Villalobos, H.; Penaloza, A.; Belkhir, L. Symptom-based screening for COVID-19 in healthcare workers: the importance of fever. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 428–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Goncalves, P.; Charbit, B.; Grzelak, L.; Beretta, M.; Planchais, C.; et al. Distinct systemic and mucosal immune responses during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 1428–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwembe, E.N.; Ituneme, Y.N.; Mufwaya, G.M.; Lebo, L.N.; Matondo, M.K.; Yalungu, H.M.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the Circulation of Respiratory Viruses in Kinshasa: Analysis of the Prevalence and Viral Etiologies of Acute Respiratory Infections. Open J. Epidemiol. 2024, 14, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gayle, A.A.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Rocklöv, J. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, M.A.; Miah, M.M.; Khan, M.N. Reproductive number of coronavirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on global level evidence. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, N.T.; Tran, G.T.H.; Dang, A.H.; Cao, P.T.B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, H.T.L.; Vu, T.T.T.; Dong, H.V.; Huynh, L.T.M. Comparison of the Basic Reproduction Numbers for COVID-19 through Four Waves of the Pandemic in Vietnam. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozol, J.-M. Place des tests antigéniques dans le dépistage et la stratégie diagnostique de la COVID-19 : retour d’expérience de pharmaciens d’officine de la Région SUD. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 2025. Available online: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-04957403. Available online: https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-04957403 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Ganser, I.; Buckeridge, D.L.; Heffernan, J.; Prague, M.; Thiébaut, R. Estimating the population effectiveness of interventions against COVID-19 in France: A modelling study. Epidemics 2024, 46, 100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, K.; Feng, K.; Lin, X.; Lv, W.; Chen, K.; Wang, F. Impact of temperature and relative humidity on the transmission of COVID-19: a modelling study in China and the United States. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Shao, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 114, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).