1. Introduction

Latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) represents a major reservoir for future cases of active tuberculosis (TB), posing a significant challenge to global TB elimination strategies [

1]. Although individuals with LTBI do not present symptoms and are not infectious, they harbor viable

Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli, which can reactivate under immune-compromising conditions [

2,

3,

4]. Globally, approximately one-quarter of the population is estimated to have latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI), with disproportionately high prevalence in high-burden settings and among vulnerable populations such as incarcerated individuals and prison staff [

1]. Brazil is classified by the World Health Organization as one of the 30 high-burden countries, which highlights the need for targeted surveillance and prevention strategies in these high-risk groups [

1].

Prison environments are recognized as high-risk settings for TB transmission due to overcrowding, poor ventilation, and insufficient exposure to natural light [

5]. While most research has historically focused on inmates, prison staff are also exposed to these risk factors and remain a critically understudied population. In Brazil, recent studies have shown elevated rates of LTBI among prison employees, with variation according to the type of correctional unit [

6,

7].

Beyond infectious risk, prison staff are frequently affected by psychological stressors inherent to their work environment. Chronic stress, burnout, and symptoms of depression and anxiety are reported at higher rates among correctional officers compared to other professions [

8,

9]. These psychological disturbances may not only impair quality of life and job performance but also influence immune system functioning.

In this context, growing evidence supports the notion that psychosocial factors can modulate immune responses, potentially affecting susceptibility to infections such as TB [

10,

11]. Chronic psychological distress has been associated with alterations in cytokine profiles, including increased pro-inflammatory mediators [

12,

13,

14]. However, the interplay between mental health, immune markers, and LTBI status remains insufficiently explored, particularly in high-risk occupational settings.

Interleukin-22 (IL-22) is produced by innate and adaptive immune cells and plays a key role in maintaining epithelial barrier integrity, promoting tissue regeneration, and modulating inflammatory responses, which contributes to protective immunity against different bacterial and viral infections [

15]. IL-22 enhances antimicrobial responses at mucosal surfaces, thereby inducing protection against

M. tuberculosis in the lungs [

16] and prevent disturbances in the gut microbiome, a mechanism that has been associated with protection against mental health alterations [

17,

18]. Nonetheless, its precise function in LTBI remains unclear, especially in human populations with concurrent psychological burden.

Despite advances in understanding immune responses to TB, studies integrating both immunological and psychological variables in prison staff are lacking. In particular, the role of IL-22 in the context of LTBI and mental health has not been previously examined. This exploratory cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the associations between LTBI, serum IL-22 levels, and psychological distress among prison staff from São Paulo State, Brazil. By integrating immunological and mental health data, the study seeks to contribute to a better understanding of immune-psychological interactions in high-risk occupational environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspects

All participants were informed about the study and signed a free and informed consent form. The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of University of Western São Paulo (protocol No. 12874819.3.0000.5515) and is in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Study Population

This study evaluated 79 correctional officers from the Junqueirópolis Penitentiary Unit, located in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, conducted in 2019. The study population consisted of 24 females and 55 males, with mean age of 45.09 years (range: 19-66 years), with no prior history of tuberculosis or other infectious diseases at the time of interview and biological sample collection.

2.3. LTBI Investigation

The assessment of LTBI was performed using the QuantiFERON®-TB Gold PLUS in Tube test (QFT-Plus), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Peripheral blood samples (4 ml) were collected from each participant and distributed as follows: 1 ml was transferred into the Nil tube (negative control), 1 ml into the TB1 antigen tube (designed to detect CD4+ T-cell response), 1 ml into the TB2 antigen tube (designed to detect both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses), and 1 ml into the Mitogen tube (positive control). The measurement of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) levels was performed using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique. The interpretation of results was conducted according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, and the outcomes were classified as positive, negative, or indeterminate.

2.4. Psychological Distress

To assess psychological distress the translated and validated version of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale - 21 Items (DASS-21) was used [

19] This scale evaluated the participants’ levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. It is important to highlight that the methodology adopted in this study did not provide a formal diagnosis for each condition. Its objective was to identify symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. This instrument can be administered by non-psychiatric health professionals, facilitating early detection and referral [

19].

The DASS-21 consisted of 21 items, divided into three subscales of seven items each, designed to assess emotional states related to depression, anxiety, and stress. Participants indicated the degree to which they had experienced each symptom listed in the questionnaire during the week prior to the assessment, using a 4-point Likert-type scale. The total score for depression, anxiety, and stress was calculated by summing the scores of all 21 items. The final score obtained from the DASS-21 was multiplied by two to determine the final score and apply the established severity cut-off [

19].

2.5. IL-22 Levels

Serum IL-22 levels were measured using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique (Abokine, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The minimum detection limit for IL-22 was 8 pg/mL. All samples were analyzed in duplicate.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v. 8.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA). Categorical data were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between groups were made using the Mann–Whitney U test. The correlations between the QFT-Plus IFN-γ, IL-22 levels and DASS-21 scores were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Psychological Distress According to LTBI Status

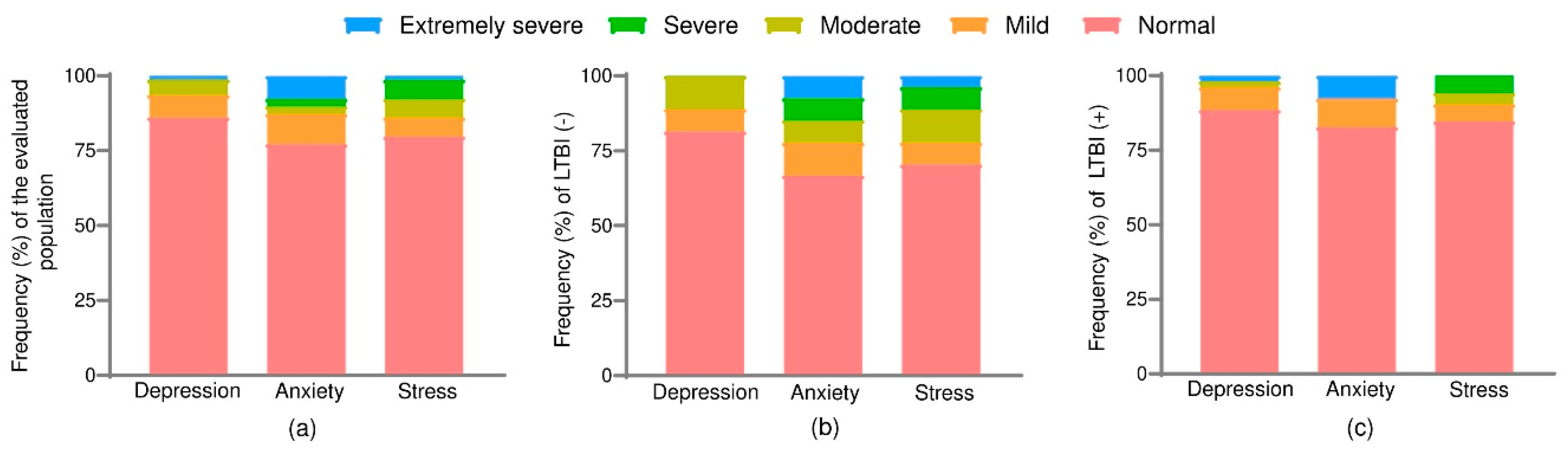

The overall prevalence of LTBI in the study population was 34.18% (n = 27). Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress were present in 13.92%, 22.78%, and 20.25% of participants, respectively. (

Figure 1a;

Table S1).

When stratified by LTBI status, LTBI-negative participants showed slightly higher proportions of “normal” scores, particularly for depression (88.46%) and anxiety (82.69%). Severe and extremely severe anxiety appeared in 7.69%, and moderate levels of stress were reported by 3.85% of this group (

Figure 1b).

Among LTBI-positive individuals, there was a higher proportion of moderate and severe symptoms, particularly for anxiety and stress. Specifically, 7.41% of LTBI-positive participants reported severe anxiety, while 11.11% reported moderate depression and stress. Furthermore, 3.70% experienced extremely severe stress, a finding absent in the LTBI-negative group (

Figure 1c;

Table S1).

Despite these differences in the distribution of severity levels, no statistically significant differences were observed in DASS-21 composite scores between LTBI-positive and negative groups (p > 0.05). These non-significant trends may indicate a potential psychosocial vulnerability among LTBI-positive staff that warrants further longitudinal investigation.

3.2. Serum IL-22 Levels in Relation to LTBI and Psychological Distress

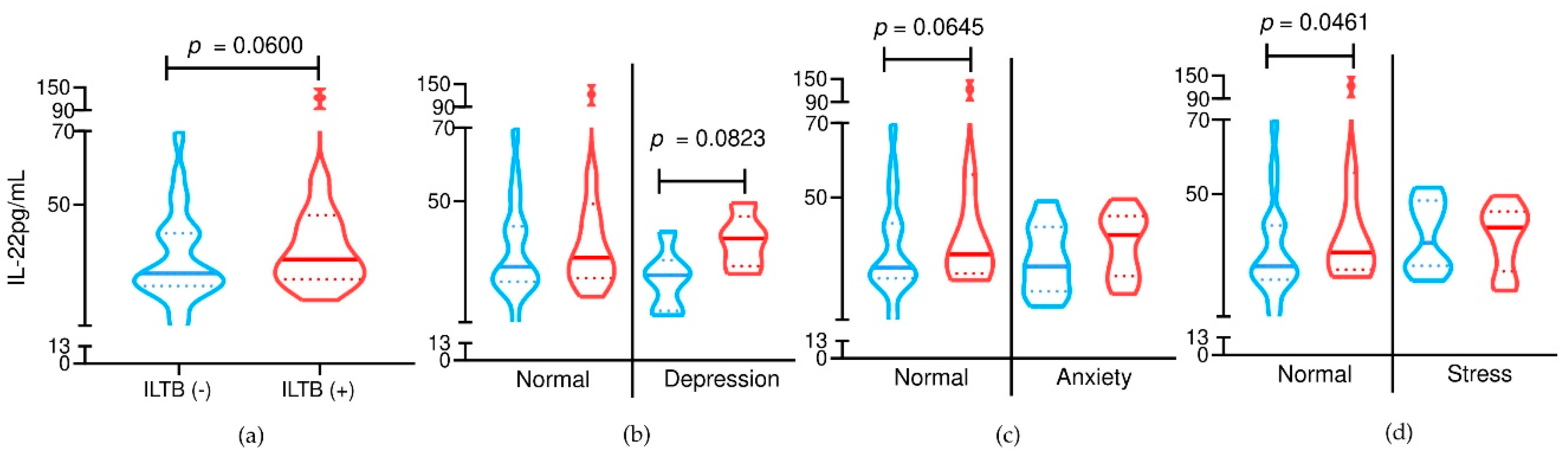

Serum IL-22 concentrations were compared across LTBI status and psychological distress subgroups (

Figure 2). Participants with LTBI tended to present higher IL-22 levels than LTBI-negative individuals, with a trend toward statistical significance (

p = 0.0600), suggesting a possible immune response modulation associated with latent infection.

In the subgroup analysis, no statistically significant differences were observed between LTBI-positive and LTBI-negative participants with symptoms of depression, anxiety, or stress. However, among participants with normal anxiety scores, IL-22 levels showed a non-significant trend toward being higher in the LTBI-positive group (p = 0.0823), whereas no such trend was observed in those with anxiety symptoms.

For stress, a statistically significant difference in IL-22 levels was observed only among participants without stress symptoms, in which LTBI-positive individuals had significantly higher IL-22 levels compared to LTBI-negative ones (p = 0.0461). No significant difference was found among participants reporting stress symptoms.

These findings suggest that the immunological behavior of IL-22 in LTBI may be more pronounced in individuals without concurrent psychological distress, potentially indicating an early or independent immunomodulatory signal in response to latent infection.

Additionally, when psychological distress was analyzed independently of LTBI status, no statistically significant differences in IL-22 levels were found between participants with and without symptoms of depression, anxiety, or stress (p > 0.05 for all comparisons). These results reinforce the hypothesis that IL-22 variations are more strongly influenced by LTBI status than by psychological symptoms alone.

3.3. IL-22 and Psychological Symptoms in Relation to IFN-γ Responses: A Correlation Analysis

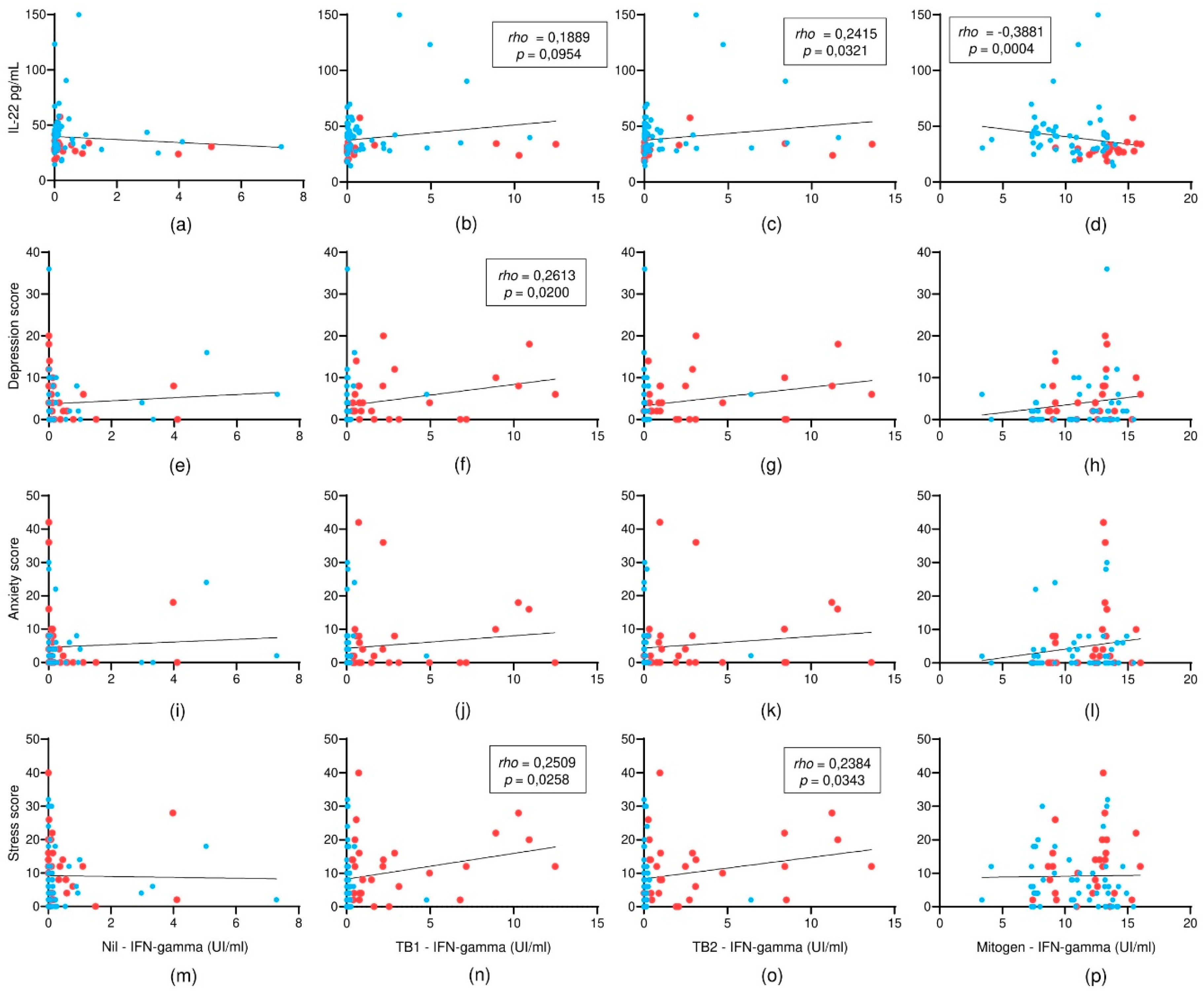

Spearman correlation analyses were conducted to explore the relationships among serum IL-22 levels, psychological distress scores, and IFN-γ responses obtained through the QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus assay (

Figure 3). IL-22 levels were positively correlated with IFN-γ concentrations in response to TB2 antigens (

rho = 0.26;

p = 0.0321), suggesting a potential role for IL-22 in enhancing pathogen-specific immune responses. In contrast, an inverse correlation was observed between IL-22 levels and Mitogen-stimulated IFN-γ responses (

rho = –0.38;

p = 0.0004), indicating a possible selective immunomodulatory effect.

Regarding psychological variables, no significant correlations were found between IL-22 levels and depression, anxiety, or stress scores (p > 0.05 for all comparisons). However, significant positive correlations were observed between IFN-γ responses to TB1 antigens and depression scores (rho = 0.27; p = 0.0200), as well as between IFN-γ responses to TB1 and TB2 antigens and stress scores (rho = 0.26; p = 0.0258 and rho = 0.25; p = 0.0343, respectively). These findings suggest that TB-specific immune activation, as reflected by IFN-γ levels, may be associated with higher levels of psychological stress and depressive symptoms in prison staff.

Overall, the results indicate a complex interplay between immune responses and psychological state, with IL-22 selectively modulating IFN-γ responses depending on the type of stimulus, while IFN-γ itself appears to correlate with dimensions of mental distress.

4. Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the immuno-psychological landscape of prison staff, a vulnerable occupational group in a high TB burden country. We found that the prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) among prison staff in São Paulo State, Brazil, was 34.2%, consistent with previous estimates in similar settings. Symptoms of psychological distress, including anxiety, stress and depression, were also observed, although no statistically significant differences in DASS-21 scores were found between LTBI-positive and negative individuals. Notably, IL-22 serum levels tended to be higher in LTBI-positive participants and showed a positive correlation with IFN-γ responses to TB-specific antigens, while being inversely associated with mitogen-stimulated responses. These findings suggest a potential immunomodulatory role for IL-22 in selectively enhancing pathogen-specific immunity while dampening generalized immune activation. Furthermore, depression and stress scores demonstrated a positive association with IFN-γ responses, suggesting a possible interaction between psychological stress and immune reactivity.

The observed LTBI prevalence of 34.2% among prison staff aligns with previous studies in Brazilian correctional facilities, which have reported LTBI rates ranging from 22.6% to over 50%, depending on regional and occupational factors [

6,

7]. Our findings reinforce the notion that prison workers face substantial exposure risks in the carceral environment. In terms of psychological distress, the presence of symptoms such as anxiety and stress was notable, in agreement with other Brazilian studies involving prison officers, which reported 33.5% of common mental disorders and 30.4% of minor psychiatric disorders [

20,

21]. Our study did not find significant differences in the prevalence of psychological distress between LTBI-positive and negative individuals, associations not evaluated by other studies.

Regarding IL-22, our results showed that LTBI-positive individuals tended to present elevated levels of this cytokine, which is consistent with previous findings. He et al. [

22] demonstrated the presence of IL-22–producing CD4

+ T cells in LTBI-positive individuals, with increased IL-22 levels compared to LTBI-negative individuals. Similarly, Bunjun et al. [

23] reported high frequencies of Th22 cells derived from PBMCs after 12 hours of stimulation and elevated IL-22 levels in whole blood after 24 hours, both using Mycobacterium-specific antigens in LTBI-positive participants. Collectively, these findings support the potential of IL-22 as a promising biomarker for LTBI diagnosis.

Interestingly, the inverse association observed between IL-22 levels and mitogen-stimulated IFN-γ responses may reflect a regulatory function of IL-22 in the immune system. This cytokine appears to modulate generalized immune activation by downregulating nonspecific inflammatory responses, an effect that aligns with its known role in maintaining epithelial integrity and limiting tissue damage during chronic infections. Such immunomodulation may be particularly relevant in individuals experiencing sustained antigenic exposure, such as correctional facility staff, by helping to prevent immune exhaustion and preserve functional immune surveillance mechanisms [

15].

From a psychosocial perspective, the positive association observed between IFN-γ responses and psychological distress, particularly stress and depression, aligns with emerging evidence that psychological stress modulates immune pathways, especially those related to Th1 responses. Chronic stress has been shown to influence cytokine profiles, contributing to increased IFN-γ secretion and altered immune surveillance [

12,

13,

14]. The current study did not demonstrate a significant relationship between IL-22 levels and symptoms of depression, anxiety, or stress, emerging hypotheses suggest that IL-22 may participate in neuroimmune interactions relevant to psychiatric conditions. A recent review proposed a unifying hypothesis in which IL-22 may serve as a peripheral immune signal that contributes to central nervous system (CNS) dysregulation, particularly in disorders such as schizophrenia [

18]. Notably, stress-induced immune activation has been linked to the mobilization of Th17 cells and IL-22 release, as described by Xia et al. [

24], suggesting that IL-22 may play a dual role in both regulating immune responses and mitigating the neurobehavioral impact of stress. However, to date, no studies have specifically investigated the relationship between Th22 cell profiles and mental health conditions, highlighting a gap in current psychoneuroimmunology literature.

Taken together, our findings suggest that IL-22 may occupy a central position linking LTBI, immune regulation, and psychological distress. The observed elevation of IL-22 levels among LTBI-positive individuals, along with its positive association with TB-specific IFN-γ responses, supports the notion that IL-22 contributes to pathogen-directed immunity in early or contained stages of infection. At the same time, the inverse association with mitogen-stimulated responses indicates that IL-22 may help limit nonspecific immune activation, thereby acting as a regulator of systemic inflammatory tone. Although no direct relationship was observed between IL-22 levels and psychological symptoms, growing evidence suggests that IL-22 can interface with neuroimmune pathways, particularly under conditions of chronic stress or epithelial barrier disruption. In this context, IL-22 may represent a biological link between psychosocial stressors and immune homeostasis, potentially influencing both infection control and broader physiological resilience. These integrated mechanisms warrant further investigation in longitudinal designs that capture dynamic interactions between immunity, psychological distress, and TB latency.

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences between immune markers and psychological distress. Second, the relatively small sample size may have limited statistical power to detect subtle associations, particularly in subgroup analyses. Third, the sample size also prevented the use of multivariable models, limiting our ability to adjust for potential confounders; as a result, residual confounding cannot be excluded. Fourth, other important confounders such as previous mental health diagnoses and medication use were not assessed. Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable preliminary data on the interplay between immune response and psychological status in a vulnerable occupational group within a high TB burden setting.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that IL-22 may act as a selective immunomodulator, enhancing TB-specific immune responses (as reflected by IFN-γ release to mycobacterial antigens) while potentially dampening generalized immune activation (e.g., responses to mitogens). This nuanced role supports the hypothesis of IL-22 functioning not only in pathogen control but also in maintaining immune homeostasis during latent infection.

Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to explore causal links and cytokine fluctuations over time, especially across LTBI progression or reactivation. Comparative studies including non-prison staff populations, as well as more comprehensive psychosocial assessments, could help clarify the biological and behavioral factors influencing immune regulation. Mechanistic studies focusing on IL-22’s role in latent infection, immune balance, and potential neuroimmune effects are particularly warranted.

In conclusion, our results advocate for integrated approaches to tuberculosis control that incorporate both immunological and mental health surveillance, especially in structurally vulnerable environments. IL-22 emerges as a promising biomarker deserving of further exploration in the intersection between immunity, mental health, and TB latency.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: Distribution of psychological distress levels (DASS-21) among all participants and stratified by LTBI status.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P.L. and F.N.G.B.; methodology, E.P.L., F.N.G.B, C.E.S. and A.A.S.A.; formal analysis, E.P.L. and F.N.G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.P.L. and F.N.G.B.; writing—review and editing, E.P.L., F.N.G.B, L.R.T.V., J.G.A.M. and D.V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Associação Prudentina de Educação e Cultura - Apec, grant number 5615. This study also received support from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) through a Scientific Initiation Scholarship awarded to F.N.G.B., grant number 2019/15559-0.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (protocol 5615) and Ethics Committee (protocol 12874819.3.0000.5515) of Universidade do Oeste Paulista – Unoeste, on July 5th of 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions involving correctional officers. Data can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with appropriate institutional approval.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT by OpenAI for the purposes of assisting with English language editing and improvement of textual fluency. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CD4+ |

Cluster of Differentiation 4 positive (T helper cells) |

| CD8+ |

Cluster of Differentiation 8 positive (Cytotoxic T cells) |

| CNS |

Central Nervous System |

| DASS-21 |

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon-gamma |

| IL-22 |

Interleukin-22 |

| LTBI |

Latent Tuberculosis Infection |

| M. tuberculosis

|

Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| QFT-Plus |

QuantiFERON®-TB Gold PLUS in Tube test |

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2025 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Kumar, N.; Babu, S. Impact of diabetes mellitus on immunity to latent tuberculosis infection. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 2023, 4, 1095467. [CrossRef]

- Rangaraj, S.; Agarwal, A.; Banerjee, S. Bird’s Eye View on Mycobacterium tuberculosis–HIV Coinfection: Understanding the Molecular Synergism, Challenges, and New Approaches to Therapeutics. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Kakadiya, R.; Sharma, A.; Naidu, S.; De, D.; Sharma, V. Assessment and management for latent tuberculosis before advanced therapies for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A comprehensive review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Manual de Recomendações para o Controle da Tuberculose no Brasil; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2019.

- Nogueira, P.A.; Abrahão, R.M.C.M.; Galesi, V.M.N.; López, R.V.M. Tuberculosis and latent infection in employees of different types of prison units. Rev. Saúde Pública 2018, 52, 13. [CrossRef]

- Trevisol, M.; Moreira, T.; Sanvezzo, G.; Guedes, S.; Da Silva, D.; Wendt, G.; Coelho, H.; Ferreto, L. Latent Tuberculosis Infection Diagnosis Using QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus Kit Among Correctional Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study in Francisco Beltrão-PR, Brazil. J. Community Health 2023. [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Monteiro, S.; Cunha, A.; Pereira, H.; Esgalhado, G. Job stress and burnout among prison staff: a systematic literature review. J. Crim. Psychol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W.; Ricciardeli, R. Correctional officers and the ongoing health implications of prison work. Health Justice 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Espinosa, J.; Hernández-Pando, R. Psychiatric Problems in Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Depression and Anxiety. J. Tuberc. Res. 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bai, X.; Ren, R.; Tan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, H.; Yang, Q.; He, J.; Tang, X. Association between depression or anxiety symptoms and immune-inflammatory characteristics in in-patients with tuberculosis: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Won, E.; Kim, Y. Neuroinflammation-Associated Alterations of the Brain as Potential Neural Biomarkers in Anxiety Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Alotiby, A. Immunology of Stress: A Review Article. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Lin, J.; Deng, Y.; Ji, Y.; Liang, C.; Wei, S.; Jing, X.; Yan, F. The immunological perspective of major depressive disorder: unveiling the interactions between central and peripheral immune mechanisms. J. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 22. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, L.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, M.; Liang, C. Current Knowledge of Th22 Cell and IL-22 Functions in Infectious Diseases. Pathogens 2023, 12, 176. [CrossRef]

- Ronacher, K.; Sinha, R.; Cestari, M. IL-22: An Underestimated Player in Natural Resistance to Tuberculosis? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Barichello, T. The role of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) in mental health. Discov. Ment. Health 2022, 2. [CrossRef]

- Sfera, A.; Thomas, K.; Anton, J. Cytokines and Madness: A Unifying Hypothesis of Schizophrenia Involving Interleukin-22. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Vignola, R.C.B.; Tucci, A.M. Adaptation and validation of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) to Brazilian Portuguese. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 155, 104–109. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, D.; Gonçalves, S.; Girotto, E.; González, A.; Melanda, F.; Rodrigues, R.; Mesas, A. Working conditions and common mental disorders in prison officers in the inland region of the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pauli, F.; Follador, F.; Wendt, G.; Lucio, L.; Pascotto, C.; Ferreto, L. Working Conditions and Health of Prison Officers in Paraná (Brazil). Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penitenciaria 2022, 24. [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Fan, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. Characterization of cytokine profile to distinguish latent tuberculosis from active tuberculosis and healthy controls. Cytokine 2020, 135, 155218. [CrossRef]

- Bunjun, R.; Omondi, F.M.A.; Makatsa, M.S.; et al. Th22 Cells Are a Major Contributor to the Mycobacterial CD4+ T Cell Response and Are Depleted During HIV Infection. J. Immunol. 2021, 207, 1239–1249. [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Lu, J.; Lan, J.; et al. Elevated IL-22 as a result of stress-induced gut leakage suppresses septal neuron activation to ameliorate anxiety-like behavior. Immunity 2025, 58, 218–231.e12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).