Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 68V20

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Morse-Kelley Axiomatic Set Theory

- Parameter Class :Type.

- Parameter In : Class -> Class -> Prop.

- Notation "x ∈ y" := (In x y) (at level 10).

- Parameter Classifier : (Class -> Prop) -> Class.

- Notation "\{ P \}" := (Classifier P) (at level 0).

- Definition Ensemble (s :Class) = ∃ C, s ∈ C.

- Axiom AxiomI : ∀ x y, x = y <-> (∀ z, z ∈ x <-> z ∈ y).

- Axiom AxiomII : ∀ b P, b ∈ \{ P \} <-> Ensemble b /\ (P b).

- Axiom AxiomIII : ∀ {x}, Ensemble x -> ∃ y, Ensemble y /\ (∀ z, z ⊂ x -> z ∈ y).

- Axiom AxiomIV : ∀ {x y}, Ensemble x -> Ensemble y -> Ensemble (x∪y).

- Axiom AxiomV : ∀ {f}, Function f -> Ensemble dom(f) -> Ensemble ran(f).

- Axiom AxiomVI : ∀ x, Ensemble x -> Ensemble (∪ x).

- Axiom AxiomVII : ∀ x, x ≠ Ø -> ∃ y, y ∈ x /\ x ∩ y = Ø.

- Axiom AxiomVIII : ∃ y, Ensemble y /\ Ø ∈ y /\ (∀ x, x ∈ y -> x∪[x] ∈ y).

- Axiom AxiomIX : ∃ c, ChoiceFunction c /\ dom(c) = μ ̃ [Ø].

3.1. Optimization and Automation

- (* Simplification for existential quantifier in the hypothesis *)

- Ltac deHex1 :=

- match goal with

- H: ∃ x, ?P

- |- _ => destruct H as []

- end.

- Ltac rdeHex := repeat deHex1; deand.

- (* Simplification for empty-class *)

- Ltac eqext := apply AxiomI; split; intros.

- (* Simplification for classification axiom-scheme *)

- Ltac appA2G := apply AxiomII; split; eauto.

- Ltac appA2H H := apply AxiomII in H as [].

- Ltac PP H a b := apply AxiomII in H as [? [a [b []]]]; subst.

- Ltac appoA2G := apply AxiomII’; split; eauto.

- Ltac appoA2H H := apply AxiomII’ in H as [].

- (* Simplification for intersection and union *)

- Ltac deHun :=

- match goal with

- | H: ?c ∈ ?a ∪ ?b

- |- _ => apply MKT4 in H as [] ; deHun

- | _ => idtac

- end.

- Ltac deGun :=

- match goal with

- | |- ?c ∈ ?a∪?b => apply MKT4 ; deGun

- | _ => idtac

- end.

- Ltac deHin :=

- match goal with

- | H: ?c ∈ ?a ∩ ?b

- |- _ => apply MKT4’ in H as []; deHin

- | _ => idtac

- end.

- Ltac deGin :=

- match goal with

- | |- ?c ∈ ?a ∩ ?b => apply MKT4’; split; deGin

- | _ => idtac

- end.

- (* Simplification for empty-class *)

- Ltac emf :=

- match goal with

- H: ?a ∈ Ø

- |- _ => destruct (MKT16 H)

- end.

- Ltac eqE := eqext; try emf; auto.

- Ltac feine z := destruct (@ MKT16 z).

- Ltac NEele H := apply NEexE in H as [].

- (* Simplification for ordered pair *)

- Ltac ope1 :=

- match goal with

- H: Ensemble ([?x,?y])

- |- Ensemble ?x => eapply MKT49c1; eauto

- end.

- Ltac ope2 :=

- match goal with

- H: Ensemble ([?x,?y])

- |- Ensemble ?y => eapply MKT49c2; eauto

- end.

- Ltac ope3 :=

- match goal with

- H: [?x,?y] ∈ ?z

- |- Ensemble ?x => eapply MKT49c1; eauto

- end.

- Ltac ope4 :=

- match goal with

- H: [?x,?y] ∈ ?z

- |- Ensemble ?y => eapply MKT49c2; eauto

- end.

- Ltac ope := try ope1; try ope2; try ope3; try ope4.

- Ltac xo :=

- match goal with

- |- Ensemble ([?a, ?b]) => try apply MKT49a

- end.

- Ltac rxo := eauto; repeat xo; eauto.

- (* Simplification for mathematical induction *)

- Ltac MI x := apply Mathematical_Induction with (n:=x); auto; intros.

3.2. Classification Axiom-Scheme for Ordered Pair

- Parameter Classifier_P : (Class -> Class -> Prop) -> Class.

- Notation "\{\ P \}\" := (Classifier_P P) (at level 0).

- Axiom AxiomII_P : ∀ a b P, [a, b] ∈ \{\ P \}\ <-> Ensemble [a, b] /\ (P a b).

- Axiom Property_P : ∀ z P, z ∈ \{\ P \}\ -> (∃ a b, z = [a, b]) /\ z ∈ \{\ P \}\.

- Notation "\{\ P \}\" := \{ λ z, ∃ x y, z = [x, y] /\ P x y \}(at level 0).

- Fact AxiomII’ : ∀ a b P, [a, b] ∈ \{\ P \}\ <-> Ensemble [a, b] /\ (P a b).

3.3. Essential Content for Analysis

| Rocq Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| a is an element of the class A | |

| Ensemble A | A is a set |

| or | |

| and | |

| and | |

| ∅ | empty class |

| proper class | |

| A is a subclass of B | |

| ordered pair | |

| Function f | f is a function |

| dom(f) | domain of f |

| ran(f) | range of f |

| value of f at a | |

| Oridinal r | r is an ordinal |

| R | class of all ordinal numbers |

| Oridinal_Number r | r is an ordinal number |

| restriction of f on x | |

| OnTo F A B | function F is from A to B |

| PlusOne n | successor of n |

| W | class of all integer numbers |

- Definition Ø := \{λ x, x ≠ x \}.

- Definition μ := \{λ x, x = x \}.

- Definition Relation r := ∀ z, z ∈ r -> ∃ x y, z = [x, y].

- Definition Function f :=

- Relation f /\ (∀ x y z, [x, y] ∈ f -> [x, z] ∈ f -> y = z).

- Definition Domain f := \{ λ x, ∃ y, [x,y] ∈ f \}.

- Notation "dom( f )" := (Domain f)(at level 5).

- Definition Range f := \{ λ y, ∃ x, [x,y] ∈ f \}.

- Notation "ran( f )" := (Range f)(at level 5).

- Definition Value f x := ∩ \{ λ y, [x,y] ∈ f \}.

- Notation "f [ x ]" := (Value f x)(at level 5).

- Definition Connect r x :=

- ∀ u v, u ∈ x -> v ∈ x -> (u ∈ v) \/ (v ∈ u) \/ (u = v).

- Definition full x := ∀ m, m ∈ x -> m ⊂ x.

- Definition Ordinal x := Connect E x /\ full x.

- Definition Ordinal_Number x := x ∈ R.

- Definition Restriction f x := f ∩ (x × μ).

- Notation "f | ( x )" := (Restriction f x)(at level 30).

- Definition OnTo F A B := Function F /\ dom(F) = A /\ ran(F) ⊂ B.

- Definition PlusOne n := n ∪ [n].

4. Key Theorems

4.1. Preliminary Property

- Property MKT107 : ∀ x, Ordinal x -> WellOrdered E x.

- Property MKT113 : Ordinal R /\ ̃ Ensemble R.

- Property MKT114 : ∀ x, Section x E R -> Ordinal x.

- Property MKT127 : ∀ {f h g},

- Function f -> Ordinal dom(f) -> (∀ u, u ∈ dom(f) -> f[u] = g[f|(u)]) ->

- Function h -> Ordinal dom(h) -> (∀ u, u ∈ dom(h) -> h[u] = g[h|(u)]) ->

- h ⊂ f \/ f ⊂ h.

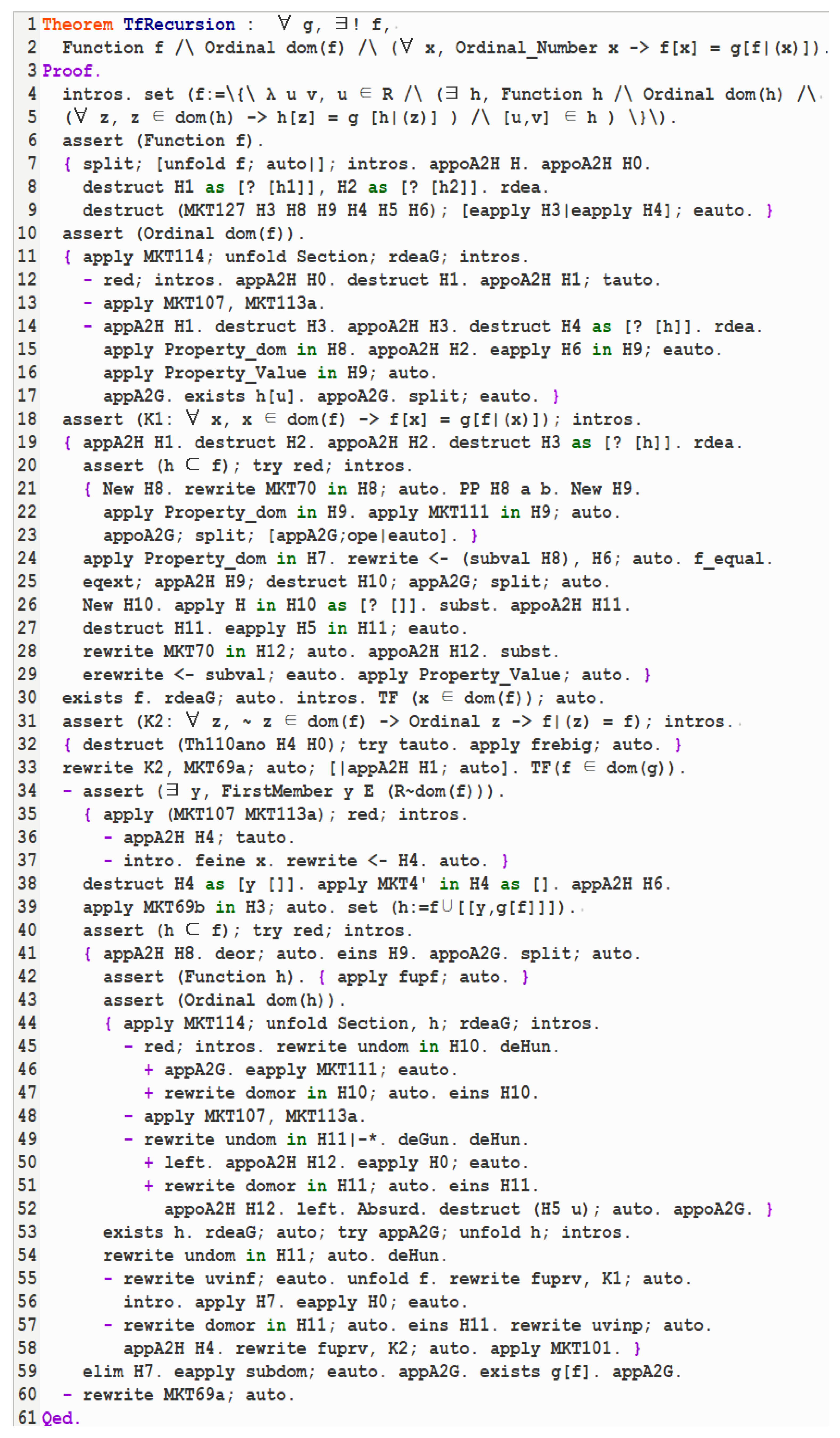

4.2. Transfinite Recursion Theorem

- Theorem TfRecursion : ∀ g, ∃! f,

- Function f /\ Ordinal dom(f) /\ (∀ x, Ordinal_Number x -> f[x] = g[f|(x)]).

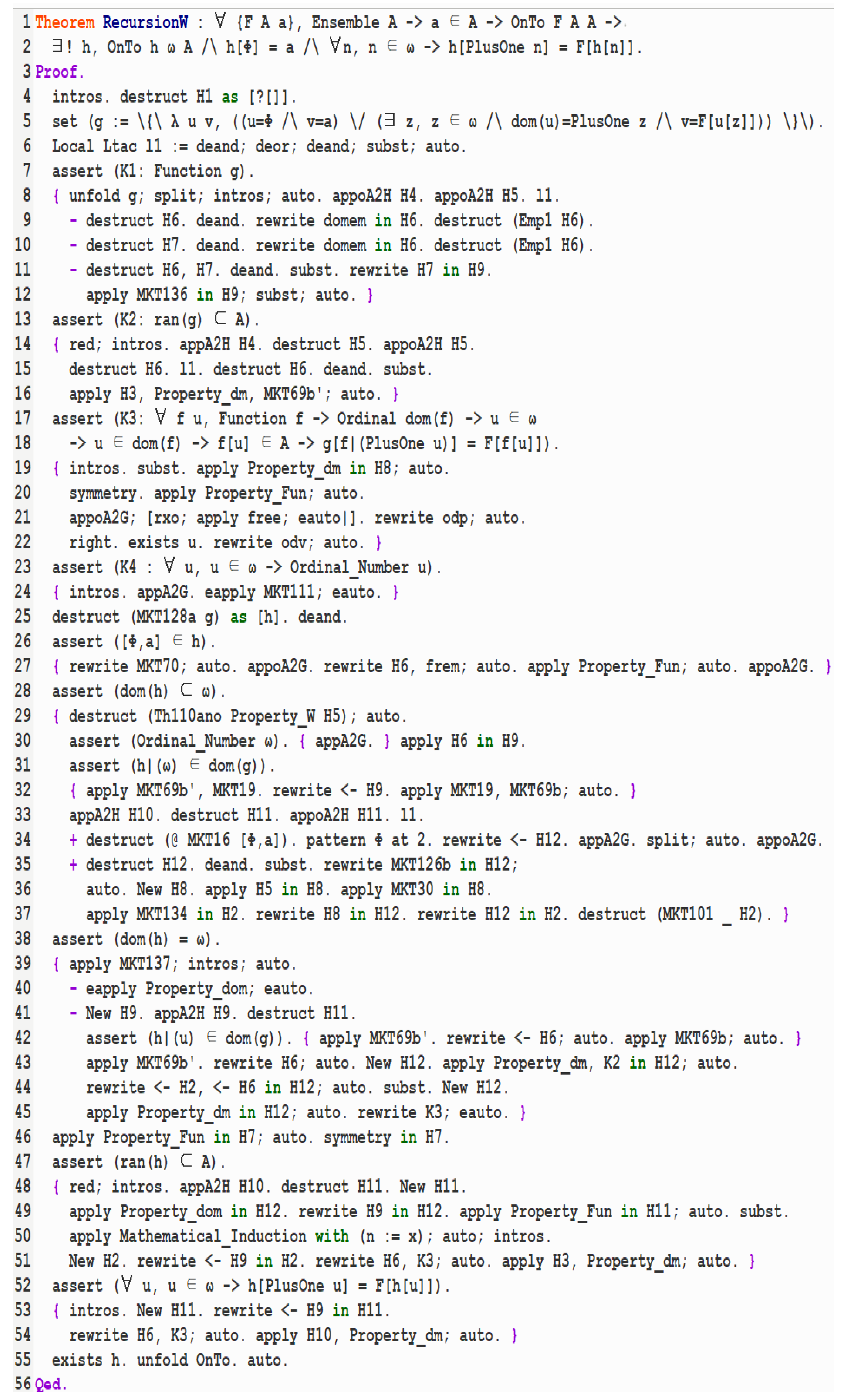

4.3. Recursion Theorem on Natural Numbers

- Theorem RecursionW: ∀ F A a, Ensemble A -> a ∈ A -> OnTo F A A ->

- ∃! h, OnTo h W A /\ h[Ø] = a /\ ∀n, n ∈ W -> h[PlusOne n] = F[h[n]].

5. Machine Proof System of Analysis

5.1. Natural Nnumbers

- Definition One := PlusOne Ø.

- Definition Nat := W ̃ [Ø].

- Definition Nsuc := \{\ λ u v, u ∈ Nat /\ v = PlusOne u \}\.

- Notation " x+ " := Nsuc[x](at level 0).

- Theorem MathInd : ∀ P : Class -> Prop,

- P One -> (∀ k, k ∈ Nat -> P k -> P k+) -> (∀ n, n ∈ Nat -> P n).

- Theorem RecursionNex : {F A a}, Ensemble A -> a ∈ A -> OnTo F A A ->

- ∃ h, OnTo h Nat A /\ h[One] = a /\ ∀ n, n ∈ Nat -> h[n+] = F[h[n]].

- Theorem RecursionNun : ∀ h1 h2 F A a,

- OnTo h1 Nat A -> h1[One] = a -> (∀ n, n ∈ Nat -> h1[n+] = F[h1[n]]) ->

- OnTo h2 Nat A -> h2[One] = a -> (∀ n, n ∈ Nat -> h2[n+] = F[h2[n]]) -> h1 = h2.

- Definition NArith F a :=

- ∩ \{ λ h, OnTo h Nat Nat /\ h[One] = a /\ ∀ n, n ∈ Nat -> h[n+] = F[h[n]] \}.

- Theorem FAA1 : One ∈ Nat.

- Theorem FAA2 : ∀ x y, x ∈ Nat -> y ∈ Nat -> x = y -> x+ = y+.

- Theorem FAA3 : ∀ x, x ∈ Nat -> x+ <> One.

- Theorem FAA4 : ∀ x y, x ∈ Nat -> y ∈ Nat -> x+ = y+ -> x = y.

- Theorem FAA5 : ∀ M, M ⊂ Nat -> One ∈ M -> (∀ u, u ∈ M -> u+ ∈ M) -> M = Nat.

- Definition addN := λ m, NArith Nsuc m+.

- Notation " x + y " := (addN x)[y].

- Fact addnT : ∀ {n}, n ∈ Nat ->

- OnTo (addN n) Nat Nat /\ n + One = n+ /\ ∀ m, m ∈ Nat -> n + m+ = (n + m)+.

- Definition minN x y := ∩ \{ λ z, z ∈ Nat /\ x = y + z \}.

- Notation " x - y " := (minN x y).

- Fact MinNUn : ∀ {x y z}, x ∈ Nat -> y ∈ Nat -> z ∈ Nat -> x + y = z -> y = z - x.

- Fact MinNEx : ∀ {x y}, y > x -> x ∈ Nat -> y ∈ Nat -> x + (y - x) = y.

- Definition mulN := λ m, NArith (addN m) m.

- Notation " x · y " := (mulN x)[y](at level 40).

- Fact mulNT : ∀ {n}, n ∈ Nat ->

- OnTo (mulN n) Nat Nat /\ n · One = n /\ ∀ m, m ∈ Nat -> n · m+ = (n · m) + n.

5.2. Fractions and Rational Numbers

- (* Fractions set, Numerator and Denominator *)

- Definition FC := Nat × Nat.

- Notation " p 1 " := (First p)(at level 0) : FC_scope.

- Notation " p 2 " := (Second p)(at level 0) : FC_scope.

- (* Relation(~,>,<) *)

- Definition eqv f1 f2 := (f11 · f22)%Nat = (f21 · f12)%Nat.

- Notation " f1 ̃ f2 " := (eqv f1 f2): FC_scope.

- Definition gtf f1 f2 := (f11 · f22 > f21 · f12)%Nat.

- Notation " x > y " := (gtf x y) : FC_scope.

- Definition ltf f1 f2 := (f11 · f22 < f21 · f12)%Nat.

- Notation " x < y " := (ltf x y) : FC_scope.

- (* Operation(+,-,·,÷) *)

- Definition addF f1 f2 := [f11 · f22 + f21 · f12, f12 · f22]%Nat.

- Notation "f1 + f2" := (addF f1 f2) : FC_scope.

- Definition minF f1 f2 := [(f11 · f22) - (f21 · f12), f12 · f22]%Nat.

- Notation "f1 - f2" := (minF f1 f2) : FC_scope.

- Definition mulF f1 f2 := [f11 · f21, f12 · f22]%Nat.

- Notation " f1 · f2 " := (mulF f1 f2)(at level 40) : FC_scope.

- Definition divF f1 f2 := f1 · ([f22, f21]).

- Notation "f1 / f2" := (divF f1 f2) : FC_scope.

- (* Rational Numbers *)

- Definition rC := \{λ S, ∃ F, F ∈ FC /\ S = \{λ f, f ∈ FC /\ f ̃ F \} \}%FC.

- (* Relation(>,<) *)

- Definition gtr r1 r2 := ∀ f1 f2, f1 ∈ r2 -> f2 ∈ r1 -> (f2 > f1)%FC.

- Notation " x > y " := (gtr x y) : rC_scope.

- Definition ltr r1 r2 := ∀ f1 f2, f1 ∈ r1 -> f2 ∈ r2 -> (f1 < f2)%FC.

- Notation " x < y " := (ltr x y) : rC_scope.

- (* Operation(+,-,·,÷) *)

- Definition addr r1 r2 :=

- \{ λ f, f ∈ FC /\ ∃ f1 f2, f1 ∈ r1 /\ f2 ∈ r2 /\ f ̃ (f1 + f2) \}%FC.

- Notation "r1 + r2" := (addr r1 r2) : rC_scope.

- Definition minr r1 r2 :=

- \{ λ f, f ∈ FC /\ ∃ f1 f2, f1 ∈ r1 /\ f2 ∈ r2 /\ f ̃ (f1 - f2) \}%FC.

- Notation " r1 - r2 " := (minr r1 r2) : rC_scope.

- Definition mulr r1 r2 :=

- \{ λ f, f ∈ FC /\ ∃ f1 f2, f1 ∈ r1 /\ f2 ∈ r2 /\ f ̃ (f1 · f2) \}%FC.

- Notation " r1 · r2 " := (mulr r1 r2)(at level 40) : rC_scope.

- Definition divr r1 r2 :=

- \{ λ f, f ∈ FC /\ ∃ f1 f2, f1 ∈ r1 /\ f2 ∈ r2 /\ f ̃ (f1 / f2) \}%FC.

- Notation " r1 / r2 " := (divr r1 r2)(at level 40) : rC_scope.

5.3. Cuts

- (* Cuts, Lower Number and Upper Number *)

- Definition CC := \{λ S, S ⊂ rC /\ (S <> Ø /\ ∃ r, r ∈ rC /\ ̃ r ∈ S) /\

- (∀ r1 r2, r1 ∈ S -> r2 ∈ rC -> r2 < r1 -> r2 ∈ S) /\

- (∀ r1, r1 ∈ S -> ∃ r2, r2 ∈ S /\ r1 < r2) \}%rC.

- Definition Num_L r c := r ∈ c.

- Definition Num_U r c := ̃ r ∈ c.

- (* Relation(>,<) *)

- Definition gtc c1 c2 := ∃ r, Num_L r c1 /\ Num_U r c2.

- Notation " x > y " := (gtc x y) : CC_scope.

- Definition ltc c1 c2 := ∃ r, Num_L r c2 /\ Num_U r c1.

- Notation " x < y " := (ltc x y) : CC_scope.

- (* Operation(+,-,·,1,÷,√) *)

- Definition addc c1 c2 :=

- \{λ c, ∃ r1 r2, Num_L r1 c1 /\ Num_L r2 c2 /\ c = (r1 + r2) \}%rC.

- Notation "c1 + c2" := (addc c1 c2) : CC_scope.

- Definition minc c1 c2 := \{λ r, ∃ r1 r2,

- Num_L r1 c1 /\ r2 ∈ rC /\ Num_U r2 c2 /\ r2 < r1 /\ r = (r1 - r2) \}%rC.

- Notation " x - y " := (minc x y) : CC_scope.

- Definition mulc c1 c2 :=

- \{λ c, ∃ r1 r2, Num_L r1 c1 /\ Num_L r2 c2 /\ c = (r1 · r2)%rC \}.

- Notation " c1 · c2 " := (mulc c1 c2)(at level 40) : CC_scope.

- Definition recC c := \{ λ r, r ∈ rC /\

- ∃ r0, r0 ∈ rC /\ Num_U r0 c /\ (~ LNU r0 c) /\ r = (Ntor One) / r0) \}.

- Notation " c1 / c2 " := c1 · (recC c2).(at level 40) : CC_scope.

- Definition Sqrt_C c := \{ λ r, r ∈ rC /\ (rtoC r) · (rtoC r) < c \}.

- Notation " √ c " := (Sqrt_C c)(at level 0) : CC_scope.

5.4. Real Numbers

- (* 0, positive, negative, real numbers class and value of real numbers *)

- Definition zero := Ø.

- Notation " 0 " := zero : RC_scope.

- Definition PRC := \{\ λ u v, u ∈ CC /\ v = 0 \}\.

- Definition NRC := \{\ λ u v, u = 0 /\ v ∈ CC \}\.

- Definition RC := PRC ∪ [0] ∪ NRC.

- Notation " p 1 " := (First p)(at level 0) : RC_scope.

- Notation " p 2 " := (Second p)(at level 0) : RC_scope.

- (* Relation(>,<) *)

- Definition gtR r1 r2 := (r2 ∈ PRC /\ r1 ∈ PRC /\ (r21 < r11)%CC) \/

- (r2 = 0 /\ r1 ∈ PRC) \/ (r2 ∈ NRC /\ r1 ∈ PRC) \/

- (r2 ∈ NRC /\ r1 = 0) \/ (r2 ∈ NRC /\ r1 ∈ NRC /\ (r12 < r22)%CC).

- Notation " x > y " := (gtR x y) : RC_scope.

- Definition ltR r1 r2 := (r1 ∈ PRC /\ r2 ∈ PRC /\ (r11 < r21)%CC) \/

- (r1 = 0 /\ r2 ∈ PRC) \/ (r1 ∈ NRC /\ r2 ∈ PRC) \/

- (r1 ∈ NRC /\ r2 = 0) \/ (r1 ∈ NRC /\ r2 ∈ NRC /\ (r22 < r12)%CC).

- Notation " x < y " := (ltR x y) : RC_scope.

- (* Operation(||,+,-,·,÷,√) *)

- Definition AbsR := \{\ λ r z, r ∈ RC /\

- (r ∈ NRC -> z = [r2,0]) /\ (r ∈ PRC -> z = r) /\ (r = 0 -> z = 0) \}\.

- Notation " | X | " := (AbsR[X])(at level 10) : RC_scope.

- Definition addR a := \{\ λ b c, b ∈ RC /\

- (a ∈ PRC -> b ∈ PRC -> c = [a1 + b1,0]) /\

- (a ∈ NRC -> b ∈ NRC -> c = [0, a2 + b2]) /\ (a = 0 -> c = b) /\

- (b = 0 -> c = a) /\ (a ∈ PRC -> b ∈ NRC -> (a1 = b2 -> c = 0) /\

- (gtc a1 b2 -> c = [a1 - b2,0]) /\ (ltc a1 b2 -> c = [0,b2 - a1])) /\

- (a ∈ NRC -> b ∈ PRC -> (a2 = b1 -> c = 0) /\

- (gtc a2 b1 -> c = [0,a2 - b1]) /\ (ltc a2 b1 -> c = [b1 - a2,0])) \}\.

- Notation "x + y" := ((addR x) [y]) : RC_scope.

- Definition minR := \{\ λ a b, a ∈ RC /\

- (a ∈ PRC -> b = [0,a1]) /\ (a ∈ NRC -> b = [a2,0]) /\ (a = 0 -> b = 0) \}\.

- Notation "- x" := (minR[x]) : RC_scope.

- Definition MinR x y := x + (-y).

- Notation "x - y" := MinR x y : RC_scope.

- Definition mulR a := \{\ λ b c, b ∈ RC /\ (a ∈ PRC -> b ∈ PRC -> c = [a1·b1,0]) /\

- (a ∈ NRC -> b ∈ NRC -> c = [a2·b2,0]) /\ (a ∈ PRC -> b ∈ NRC -> c = [a1·b2,0]) /\

- (a ∈ NRC -> b ∈ PRC -> c = [a2·b1,0]) /\ (a = 0 -> c = 0) /\ (b = 0 -> c = 0) \}\.

- Notation " x · y " := ((mulR x) [y])(at level 40) : RC_scope.

- Definition divR a := \{\ λ b c, b ∈ RC /\ b <> 0 /\

- (b ∈ PRC -> c = a · [(recC b1),0]) /\ (b ∈ NRC -> c = a · [0,(recC b2)]) \}\.

- Notation " x / y " := ((divR x) [y]) : RC_scope.

- Definition Sqrt_R := \{\ λ a b, a ∈ RC /\ ̃ a ∈ NRC /\

- (a ∈ PRC -> b = [(√ (a1))%CC, 0]) /\ (a = 0 -> b= 0) \}\.

- Notation " √ a " := (Sqrt_R [a])(at level 0): RC_scope.

5.5. Complex Numbers

- (* Complex numbers set, Real part and Imaginary part *)

- Definition cC := RC × RC.

- Notation " p 1 " := (First p)(at level 0) : cC_scope_.

- Notation " p 2 " := (Second p)(at level 0) : cC_scope.

- (* Operation(+,-,·,÷,¯,||) *)

- Definition addC x y := [x1 + y1, x2 + y2]%RC.

- Notation "x + y" := (addC x y) : cC_scope.

- Definition minC x y := [x1 - y1, x2 - y2]%RC.

- Notation " x - y " := (minC x y) : cC_scope.

- Definition mulC x y := [x1 · y1 - x2 · y2, x1 · y2 + x2 · y1]%RC.

- Notation " x · y " := (mulC x y) : cC_scope.

- Definition Out_1 x := ((x1) / (Square_cC x))%RC.

- Definition Out_2 x := (- ((x2) / (Square_cC x)))%RC.

- Definition DivC x y:= [(y1) / (Square_cC y), (-x2)/ (Square_cC x)] · x.

- Notation " x / y " := (DivC x y) : cC_scope.

- Definition Conj x := [x1, (-x2)]%RC.

- Notation " x $^{-}$ " := (Conj x)(at level 0) : cC_scope.

- Definition Abs_cC x := √((x1 · x1) + (x2 · x2)).

- Notation " | x | " := (Abs_cC x) : cC_scope.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

Appendix B.

References

- Beeson, M. Mixing computations and proofs. J. Formaliz. Reason. 2016, 9, 71–99.

- Van Benthem Jutting, L.S. Checking Landau’s "Grundlagen" in the AUTOMATH System. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 1977.

- Bertot, Y.; Castéran, P. Interactive Theorem Proving and Program Development. Coq’Art: The Calculus of Inductive Constructions; Texts in Theoretical Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004.

- Bernays, P.; Fraenkel, A. A. Axiomatic Set Theory. North Holland Publishing Company:Amsterdam, Netherlandish, 1958.

- Boldo, S.; Lelay, C.; Melquiond, G. Coquelicot: A User-Friendly Library of Real Analysis. Math. Comput. Sci. 2015, 9, 41–62.

- Brown, C.E. Faithful Reproductions of the Automath Landau Formalization. Technical Report. 2011. Available online: https://www.ps.uni-saarland.de/Publications/documents/Brown2011b.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- Chlipala, A. Certified Programming with Dependent Types: A Pragmatic Introduction to the Coq Proof Assistant; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013.

- The Coq Development Team. The Coq Proof Assistant Reference Manual (Version 8.9.1). 2019. Available online: https://coq.inria.fr/distrib/8.9.1/refman/ (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- Courant, R.; John, F.; Blank, A. A., et al. Introduction to Calculus and Analysis; Interscience Publishers: New York, USA, 1965.

- Coquand, T.; Paulin, C. Inductively Defined Types. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Logic (COLOG 1988), 12–16 December 1988; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; Volume 417, pp. 50–66.

- Coquand, T.; Huet, G. The calculus of constructions. Inf. Comput. 1988, 76, 95–120.

- Cruz-Filipe, L.; Marques-Silva, J.; Schneider-Kamp, P. Formally verifying the solution to the Boolean Pythagorean triples problem. J. Autom. Reason. 2019, 63, 695–722.

- Fu, Y.; Yu, W. A Formalization of Properties of Continuous Functions on Closed Intervals. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the International Congress on Mathematical Software(ICMS 2020), Braunschweig, Germany, 13–16 July 2020; Bigatti A., Carette J.,Joswig M., de Wolff T., Eds; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12097, pp. 272–280.

- Fu, Y.; Yu, W. Formalizing equivalence between real number completeness and intermediate value theorem. China Automation Congress(CAC 2021), Beijing, China, 22–24 October 2021; Volume 12097, pp. 5337–5340.

- Fu, Y.; Yu, W. Formalizing Calculus without Limit Theory in Coq. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1377, . [CrossRef]

- Gonthier, G.; Asperti, A.; Avigad, J.; Bertot, Y.; Cohen, C.; Garillot, F.; Roux, S.L.; Mahboubi, A.; O’Connor, R.; Biha, S.O.; et al. Machine-checked proof of the Odd Order Theorem. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the Interactive Theorem Proving 2013 (ITP 2013), Rennes, France, 22–26 July 2013; Blazy, S., Paulin-Mohring, C., Pichardie, D., Eds; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7998, pp. 163–179.

- Geuvers, H.; Niqui, M. Constructive reals in Coq: Axioms and categoricity. Types for Proofs and Programs(TYPES 2000), Durham, UK, 8-12 December, 2000; Goos, G., Hartmanis, J., van Leeuwen, J., Eds; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, Volume 2277, pp. 79–95.

- Gonthier, G. Formal proof—The Four Color Theorem. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 2008, 55, 1382–1393.

- Grabiner, J.V. Who gave you the epsilon? Cauchy and the origins of rigorous calculus. Am. Math. Mon. 1983, 90, 185–194.

- Grimm, J. Implementation of Bourbaki’s mathematics in Coq: Part two, from natural to real numbers. Journal of Formalized Reasoning. 1983, 90, 185–194.

- Gu, R.; Shao, Z.; Chen, H., et al. CertiKOS: An Extensible Architecture for Building Certified Concurrent OS Kernels. Proc of the USENIX Symp. Operating Syst. Design Implement,Savannah, GA, USA, 2-4 November,2016, USENIX Association: Berkeley, USA, 2016; pp. 653–669.

- Guidi, F. Verified Representations of Landau’s "Grundlagen" in the lambda-delta Family and in the Calculus of Constructions. J. Formaliz. Reason. 2016, 8, 93–116.

- Halmos, P. R. Naive Set Theory. Springer-Verlag: New York, USA, 1974.

- Hales, T. Formal proof. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 2008, 55, 1370–1380.

- Hales, T.; Adams, M.; Bauer, G.; Dang, T.D. A Formal Proof of the Kepler Conjecture. Forum of Mathematics, Pi; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; Volume 5, pp. 1–29.

- Harrision, J. Formal proof—Theory and practice. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 2008, 55, 1395–1406.

- Heijenoort J. V. From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic. Harvard University Press : Cambridge, UK, 1967.

- Heule, M.; Kullmann, O.; Marek, V. Solving and Verifying the Boolean Pythagorean Triples Problem via Cube-and-Conquer. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing 2016(SAT 2016), Bordeaux, France, 5–8 July 2016; Creignou, N., Le Berre, D., Eds; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9710, pp. 228–245.

- Harrison, J.; Urban, J.; Wiedijk, F. History of Interactive Theorem Proving. Handbook of the History of Logic: Computational Logic. 2014, 9, 135–214.

- Jiang, N.; Li, Q; Wang, L; et al. Overview on Mechanized Theorem Proving. Journal of software 2020, 31(1), 82–112.

- Kelley, J. L. General Topology. Springer-Verlag: New York, USA, 1955.

- Kirst, D.; Smolka, G. Categoricity Results for Second-Order ZF in Dependent Type Theory. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the Interactive Theorem Proving 2017 (ITP 2017), Brasília, Brazil, September 26–29, 2017; Ayala-Rincón, M., Muñoz, C.A., Eds; Springer: Cham, 2017; Volume 10499, pp. 304–318.

- Landau, E. Foundations of Analysis: The Arithmetic of Whole, Rational, Irrational, and Complex Numbers; Chelsea Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1966.

- Luo, Z. ECC, an extended calculus of constructions. In Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Symposium on Logic in Computer Science, California, USA, 5–8 June 1989; IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 386–395.

- Morse, A. P. A Theory of Sets. Academic: New York, USA, 1965.

- Vivant, C. Thèoréme Vivamt; Grasset: Prais, France, 2012.

- Voevodsky, V. Univalent Foundations of Mathematics; Beklemishev, L., De Queiroz, R., Eds; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6642, p. 4.

- Wiedijk, F. Formal proof—Getting started. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 2008, 55, 1408–1414.

- Wang, J.; Zhan, N; Feng, X; et al. Overview of Formal Methods. Journal of software 2019, 30(1), 33–61.

- Yu, W.; Sun, T.; Fu, Y. Machine Proof System of Axiomatic Set Theory; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Yu, W.; Fu, Y.; Guo. L. Machine Proof System of Analysis of foundatios; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Zorich, V. A.; Paniagua, O. Mathematical analysis; Springer: New York, USA, 2016.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).