Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Analytical Approach

- Historical database including: archival documents, such as those collected and published in the catalogue of strong earthquake in Italy and in the Mediterranean area CFTI5Med [28], as well as Alfano's 1930 report [29], and detailed monographs published in recent years by Galli and Gizzi on the 1930 earthquake [30,31,32]; administrative records containing historical details on reconstruction in Irpinia, such as Mazzoleni and Sepe 's book [10], as well as the acts of the parliamentary commission of inquiry [33], and the documented reconstruction of administrative acts of the municipality of Bisaccia (1980-1996) published in 2020 by an administrator from the time of the 1980 earthquake [34]; historical photographs documenting past earthquakes and reconstruction phases, including images of the reconstruction in Irpinia [10], and the most recent images of the reconstruction in Irpinia, photographs taken after the 1980 earthquake until a few years ago by Spiga and Porfido [20,21,24,35],

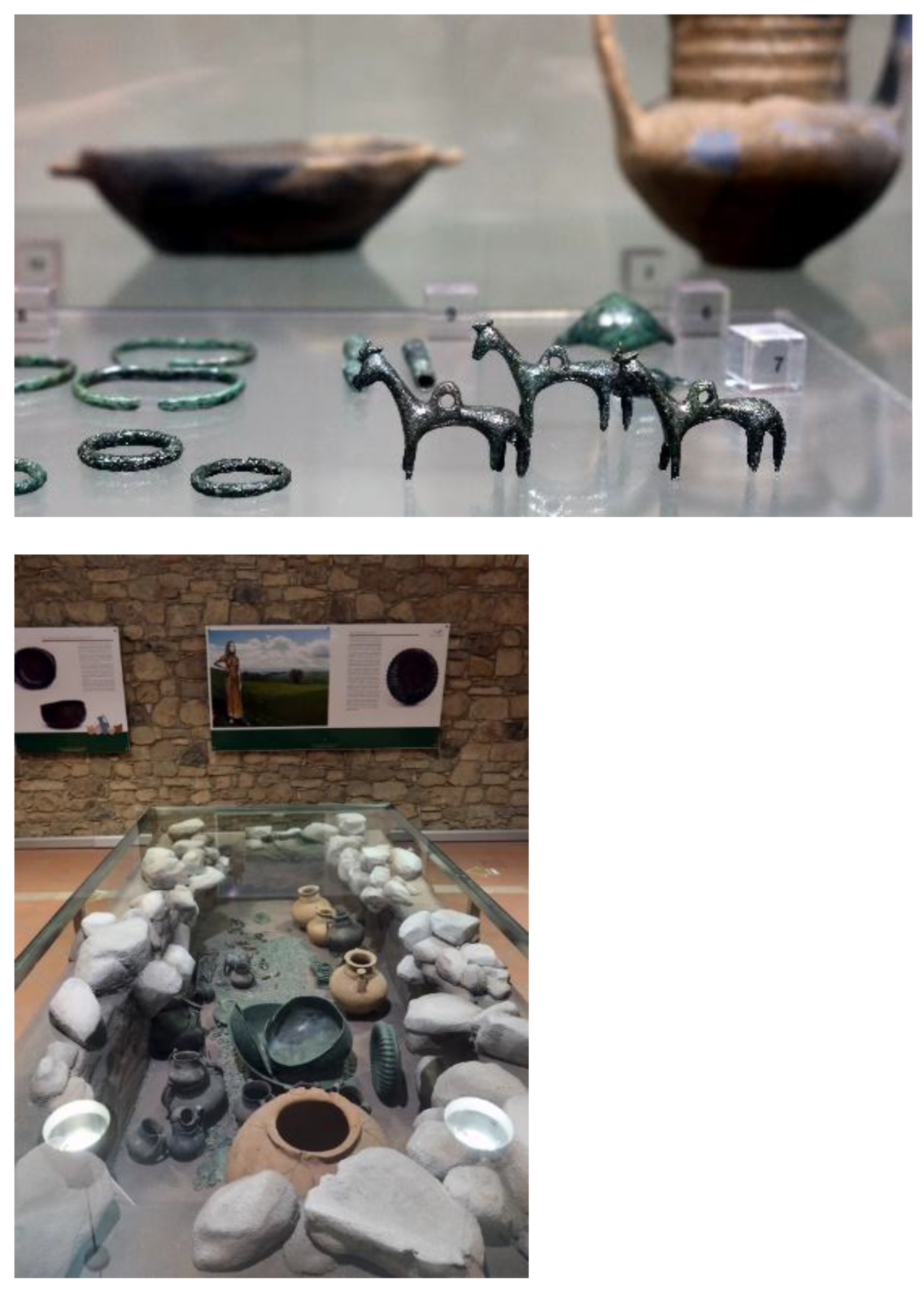

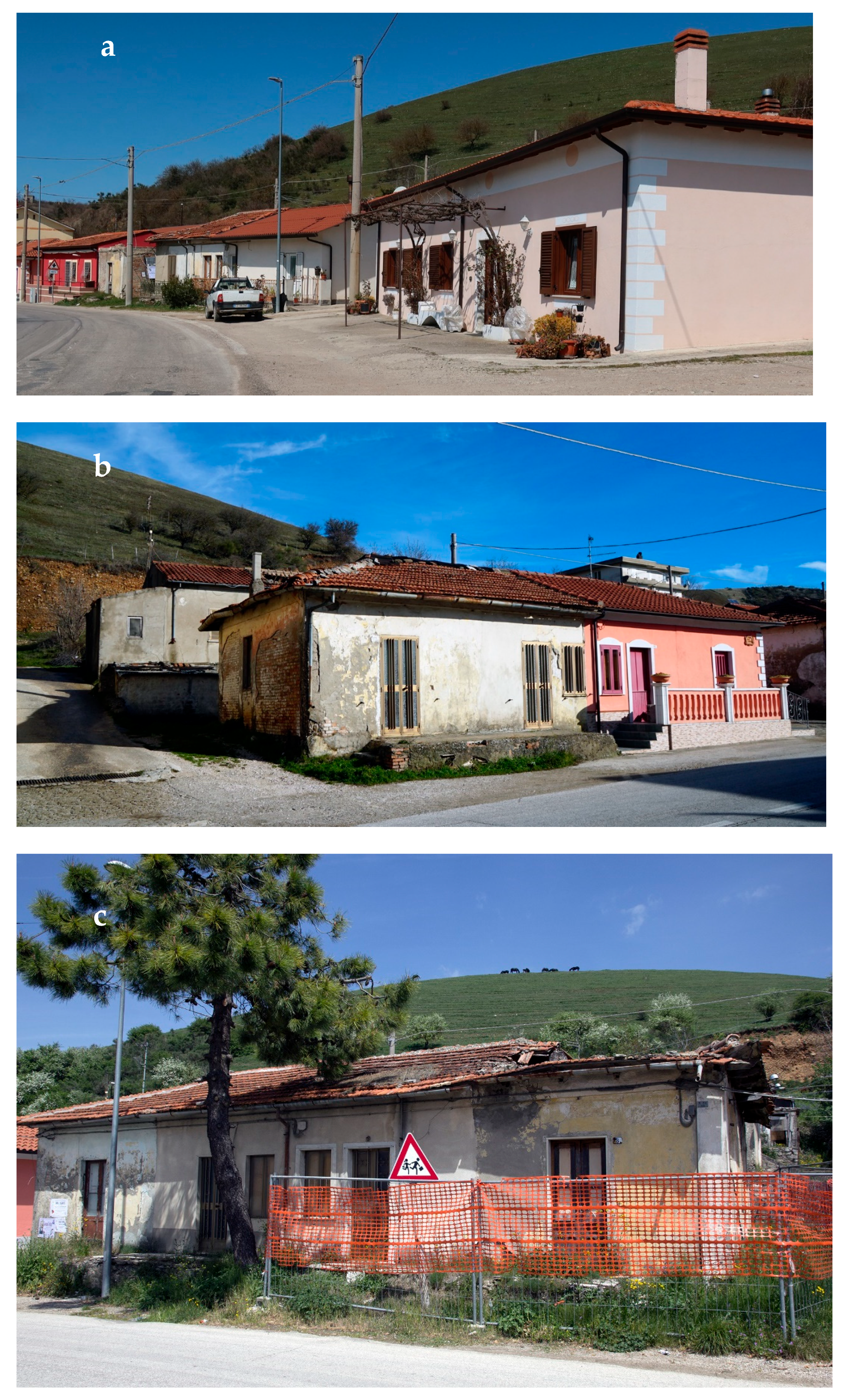

- Seismological and geological databases including: the seismic history of Bisaccia analyzed by Rovida et al. 2022 in the seismic catalogue CPTI15 [6] and by Guidoboni et al., 2019 in CFTI15med catalogue [28], as well as from the analysis of detailed historical monographs [29,30,31,39] for the 1930 earthquake and from detailed scientific studies relating to the 1980 earthquake [25,40,41,42]; numerous scientific papers detailing geological and geomorphological setting with particular focus on landslide phenomena triggered by earthquakes in the Bisaccia area [38,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Additionally, we analysed data from field surveys and documentation of both the “old” and “new” townscapes [24,49].

3. Results

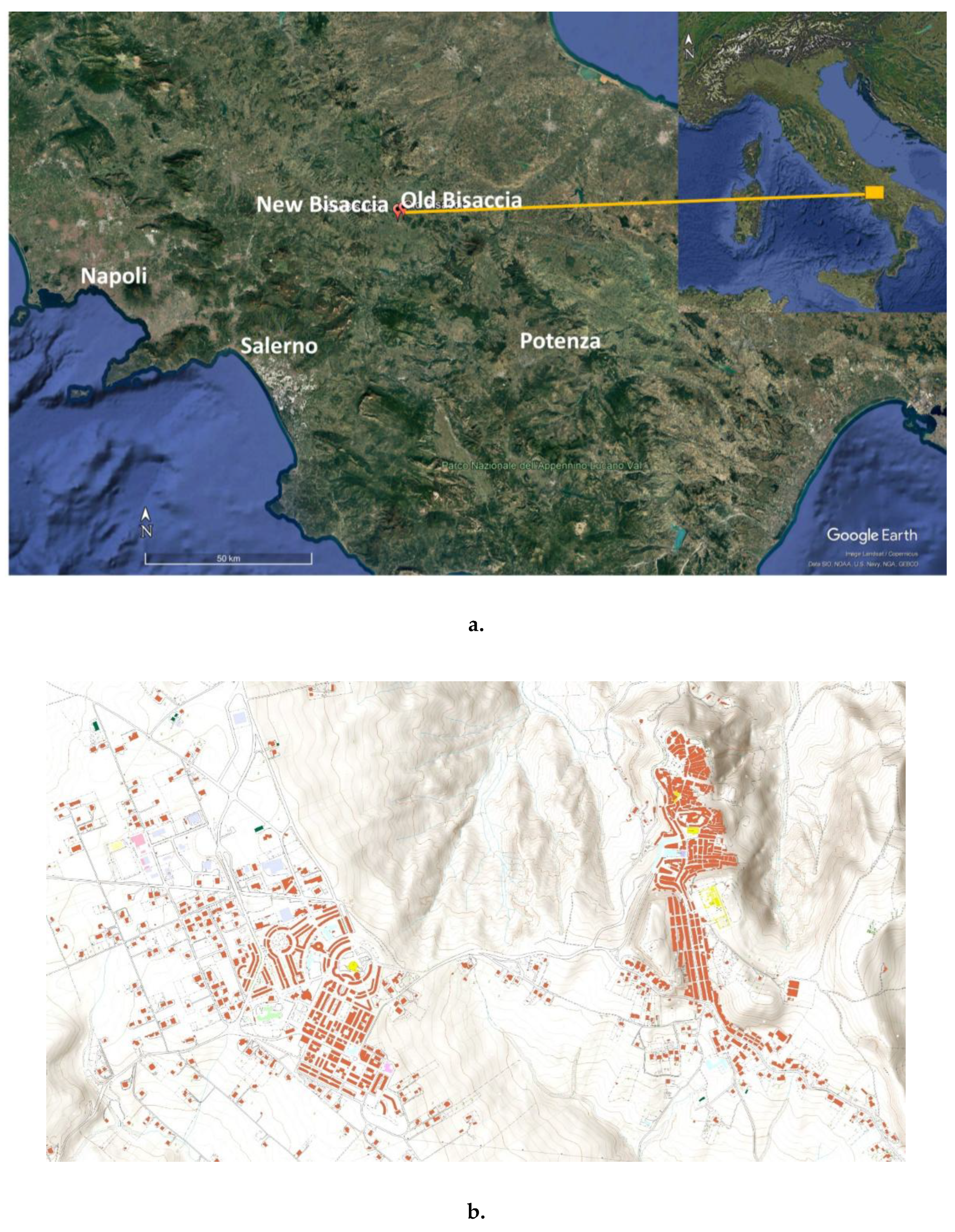

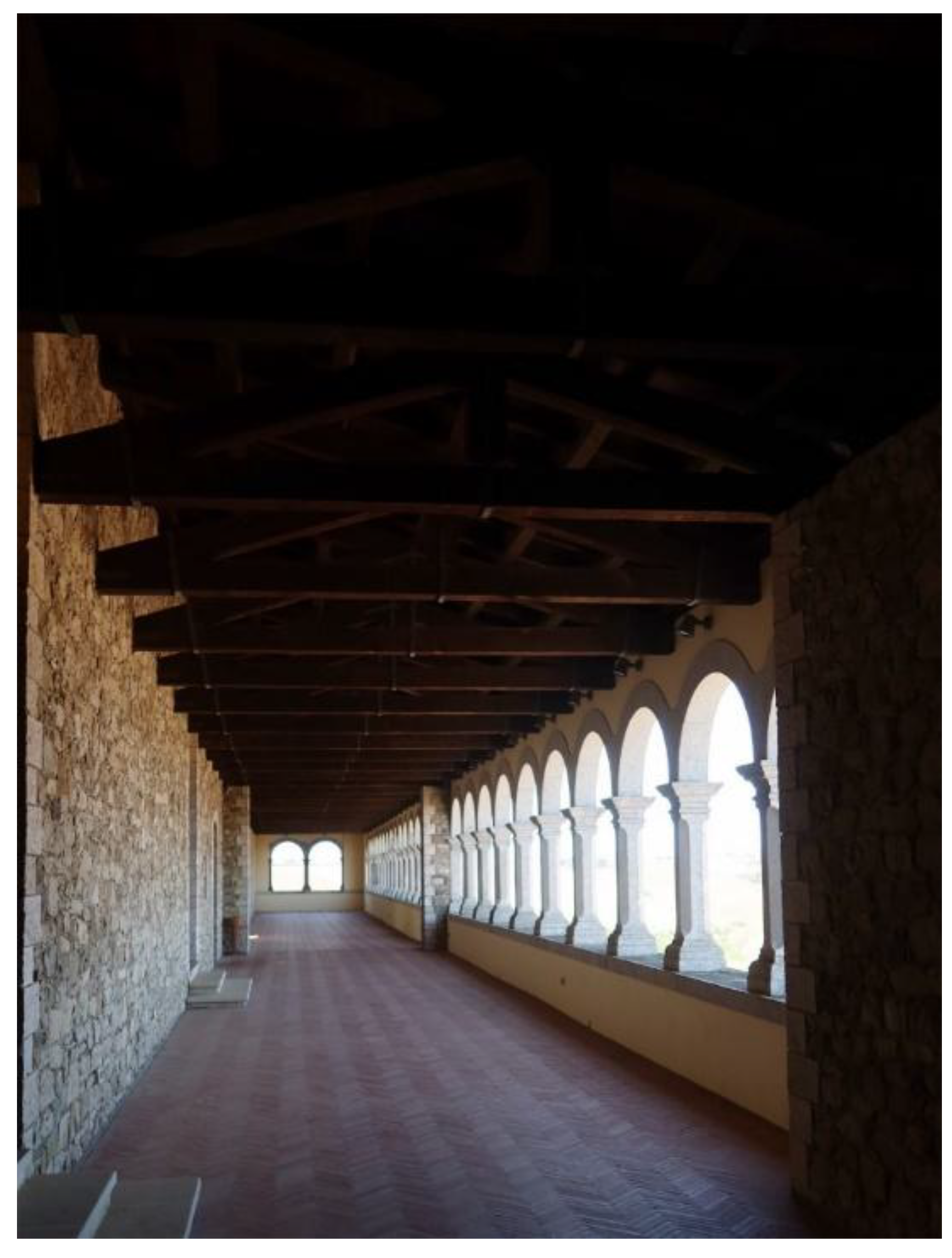

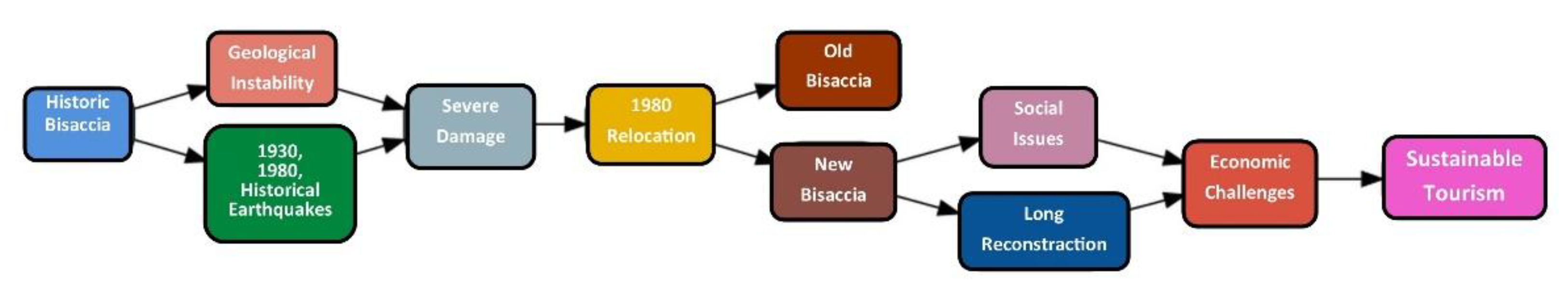

3.1. Two villages called Bisaccia

3.2. Bisaccia between hydrogeological instability and earthquakes

4. Discussion

5. Final Remarks

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lizarralde, G.; Johnson, C.; Davidson, C. Rebuilding after disasters: from emergency to sustainability. Taylor & Francis Group, 2010, pg. 296, ISBN 9780415472548.

- Clemente, M.; Salvati, L. Interrupted’ Landscapes: Post-Earthquake Reconstruction in between Urban Renewal and Social Identity of Local Communities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2015. [CrossRef]

- 005 Rivista monografica online ISBN 978-88-7603-096-3 INU Edizioni- http://www.urbanisticainformazioni.it/IMG/pdf/ud005.pdf.

- Caramaschi, S. and Coppola, A. Post-Disaster Ruins: the old, the new and the temporary. In O’Callaghan, C. 2021. ISBN 978-1447356875.

- Westaway, R. Seismic moment summation for historical earthquakes in Italy: Tectonic implications, J. Geophys. Res., 97, 1992, 15,437–15,464.

- Rovida, A.; Locati, M.; Camassi, R.; Lolli, B.; Gasperini, P.; Antonucci, A. Catalogo Parametrico dei Terremoti Italiani (CPTI15), versione 4.0. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Allen, G. and Unwin, London J. Chubb, Three earthquakes: political response. Reconstruction and the institutions: Belice (1968), Friuli (1976), Irpinia (1980), in Disastro! Disasters in Italy since 1860: culture, politics, society, ed. J. Dickie, J. Foot, F.M. Snowden, Basingstoke 2002, pp. 186-233.

- Geipel, R. Disaster and Reconstruction: The Friuli (Italy) Earthquakes of 1976, Taylor and Francis, London, 1982 ISBN 0-04-904006-5.

- Alexander, D. Housing crisis after natural disasters: the aftermath of the November 1980 southern Italian earthquake. Geoforum, 1984, Elsevier, 15 pp 489–516.

- Mazzoleni. D., Sepe M., (a cura di), (2005), Rischio sismico, paesaggio, architettura: l’Irpinia, contributi per un progetto, CRdC AMRA, Napoli.

- Gribaudi, G.; Mastroberti, F.; Senatore, F. Il Terremoto del 23 novembre 1980. Luoghi e memorie. Napoli, Editoriale Scientifica, 2021. ISBN: 9791259761392.

- Caporale, R. Toward a Cultural-Systemic Theory of Natural Disasters: The Case of the Italian Earthquakes of 1968 in Belice, 1976 in Friuli and 1980 in Campania-Basilicata. In: Quarantelli and Pelanda (eds.) 1989, Preparations for, Response to, and Recovery from Major Community Disasters, pp. 253–271.

- Amodio, T., « Territories at risk of abandonment in Italy and hypothesis of repopulation », Belgeo [Enligne], 4 | 2022, mis en ligne le 06 février 2023, consulté le 23 octobre 2025. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/belgeo/57229. [CrossRef]

- Battaglini, E. “The sustainable territorial innovation of inner peripheries. The Lazio region (Italy) case, International Studies Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal, 19, 1, pp. 87-102, 2017, DOI : 10.1515/ipcj-2017-0006.

- De Rossi, A. Riabitare l’Italia. Le aree interne tra abbandoni e riconquiste, Roma, 2018, Donzelli.

- Golini, A.; Lo Prete, M.C. Italiani poca gente. Il Paese ai tempi del malessere demografico, Roma, 2019, LUISS University Press.

- Rossi Doria, M. (2005), La polpa e l’osso. Agricoltura risorse naturali e ambiente, Napoli, L’Ancora del Mediterraneo.

- Nesticò, A.; Fiore, P.; D’Andria, E. Enhancement of Small Towns in Inland Areas. A Novel Indicators Dataset to Evaluate Sustainable Plans. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6359. [CrossRef]

- Labor Est Città Metropolitane, Aree Interne, N. 26/Giugno 2023 Iscr. Trib. di Reggio Cal. n. 12/05 ISSN 1973-7688- ISSN online 2421-3187.

- Porfido, S.; Spiga, E. Ricostruzione 1980-2020, Vol. I; Blurb: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-71-571504-5.

- Porfido, S.; Spiga, E. Ricostruzione 1980-2020; vol II, Blurb: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-71-572142-8.

- Festa, G.; Iuliano, G.; Saggese, P. Irpinia-1980–2020; Delta 3 Edizioni: Italy, p. 312, ISBN 978-88-6436-860-3.

- Comune di Bisaccia. Available online: http://bisaccia.asmenet.it/index.php?action=index&p=10208 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Spiga, E.; Porfido, S. Bisaccia Piano di Zona; Blurb ed.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-71-555296-1.

- Gizzi, F.T.; Potenza, M.R. The Scientific Landscape of November 23rd, 1980 Irpinia-Basilicata Earthquake: Taking Stock of (Almost) 40 Years of Studies. Geosciences 2020, 10, 482.

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P., and Lucatelli, S. Sommario. Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne: definizione, obiettivi, strumenti e governance (pp. 1-68). Materiali UVAL, 2014. http://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it.

- Matarazzo, N. Le aree interne della Campania: spazi e nuove tendenze del popolamento. Il caso dell’Irpinia, in «Studi e Ricerche socio-territoriali», 2019, 9, pp. 3-50.

- Guidoboni E., Ferrari G., Tarabusi G., Sgattoni G., Comastri A., Mariotti D., Ciuccarelli C., Bianchi M.G., Valensise G., CFTI5Med, the new release of the catalogue of strong earthquakes in Italy and in the Mediterranean area, Scientific Data, 2019, 6, n. 80.

- Alfano, G.B. Il terremoto irpino del 23 luglio 1930. Pubblicazione dell’Osservatorio di Pompei: Pompei, Italy, 1931.

- Galli, P.; Molin, D.; Galadini, F.; Giaccio, B. Aspetti sismotettonici del terremoto irpino del 1930. In: Castanetto, S.; Seba-stiano, M., Eds.; Il "terremoto del Vulture" 23 luglio 1930, VIII dell'Era fascista; Roma, 2002; pp. 217–262.

- Gizzi, F.T.; Masini, N. Dalle fonti all'evento. Percorsi, strumenti e metodi per l'analisi del terremoto del 23 luglio 1930 nell'area del Vulture; ESI: Napoli, Italy, 2011; ISBN 8849520506.

- Ministero lavori pubblici, Direzione Generale dei Servizi Speciali (1932) L'azione del governo fascista per la ricostruzione delle zone danneggiate da calamità. Roma. 346 pp.

- Commissione Parlamentare D’Inchiesta. Relazione Conclusiva e Propositiva, Vol. I, Tomo I. 1991. Available online: http://www.senato.it/leg/10/BGT/Schede/docnonleg/30412.htm (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Delli Bove, G. Atti fatti e altre parole - Bisaccia; stampato in proprio, 2020.

- Spiga, E.; Porfido, S. Iconografia di una ricostruzione: l’esempio di Bisaccia (Avellino) dopo il terremoto del 23 novembre 1980. In Atti del Conv. LA GEOLOGIA AMBIENTALE AL SERVIZIO DEL PAESE, 2023. Available online: https://sigea-aps.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/GDA_3-2023_supp_WEB_DEF.pdf.

- Regione Campania. Carta Tecnica Regionale (1:5000) - Aggiornamento 2020. Available online: https://geomaps.regione.campania.it/portal/apps/experiencebuilder/experience/?id=c011ae74c0484d4fa296c59de67365d1.

- Regio Decreto-Legge 30.12.1923, n.3267.

- ISPRA. Idrogeo. Available online: https://idrogeo.isprambiente.it/app/ (accessed on January 2023).

- Castanetto, S.; Sebastiano, M., Eds. Il "terremoto del Vulture" 23 luglio 1930, VIII dell'Era fascista; Roma, 2002.

- Postpischl, D.; Branno, A.; Esposito, E.; Ferrari, G.; Marturano, A.; Porfido, S.; Rinaldis, V.; Stucchi, M. The Irpinia ear-thquake of November 23, 1980. In Atlas of Isoseismal Maps of Italian Earthquakes; Bologna, Italy, 1985; 1, 114, 2A, pp. 152–157.

- Porfido, S.; Alessio, G.; Gaudiosi, G.; Nappi, R.; Michetti, A.M.; Spiga, E. Photographic Reportage on the Rebuilding after the Irpinia-Basilicata 1980 Earthquake (Southern Italy). Geosciences 2021, 11(6). [CrossRef]

- Porfido, S.; Alessio, G.; Gaudiosi, G.; Nappi, R.; Michetti, A.M. The November 23rd, 1980 Irpinia-Lucania, Southern Italy Earthquake: Insights and Reviews 40 Years Later; Porfido, S., Alessio, G., Gaudiosi, G., Eds.; MDPI AG: Basel, Swi-tzerland, 2023.

- Fiorillo, F.; Parise, M.; Wasowski, J. Slope instability in the Bisaccia area (Southern Apennines, Italy). In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Landslides, Trondheim, 1996; 2, 965–970.

- Parise, M.; Wasowski, J. Landslide Activity Maps for Landslide Hazard Evaluation: Three Case Studies from Southern Italy. Natural Hazards 1999, 20, 159–183. [CrossRef]

- Serva, L.; Esposito, E.; Guerrieri, L.; Porfido, S.; Vittori, E.; Comerci, V. Environmental Effects from some historical earthquakes in Southern Apennines (Italy) and macroseismic intensity assessment. Contribution to INQUA EEE scale project. Quaternary International 2007, 173–174, 30–44.

- Fenelli, G.B.; Picarelli, L.; Silvestri, F. Deformation process of a hill shaken by the Irpinia earthquake in 1980. In- Slope stability in seismic areas, Proc. French-Italian conf. 12–14 May, Faccioli, A.; Pecker, A., Eds.; Bordighera, 1992; pp. 47–62.

- Porfido, S.; Esposito, E.; Vittori, E.; Tranfaglia, G.; Guarrieri, L.; Pece, R. Seismically Induced Ground Effects of the 1805, 1930 and 1980 Earthquakes in the Southern Apennines, Italy. Ital, J. Geosci. 2007, 126, 333–346.

- Pizza, M.; Ferrario, M.F.; Michetti, A.L.; Nappi, R.; Velázquez-Bucio, M.M.; Lacan, P.; Porfido, S. Environmental effects caused by the Mw 6.9 23 November 1980 Irpinia-Basilicata Earthquake, Italy. Zenodo 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/10277164 (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Porfido, S.; Spiga, E. The Bisaccia IACP; Blurb: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; ISBN 979-8-1-21-063153-4.

- IACPAV. Relazione sintetica descrittiva Programma Riqualificazione Bisaccia. Available online: http://www.iapav.it/upload/progint/25052009132123Relazione%20sintetica%20descrittiva%20Programma%20Riqualificazione%20Bisaccia.pdf.

- Anonimo. Distinta relazione del danno cagionato dal tremuoto del dì 29. novembre 1732. Napoli, 1733. Decreto Giunta Regionale Campania n. 5447 del 7.11.2002.

- Porfido, S.; Esposito, E.; Luongo, G.; Marturano, A. I terremoti del XIX secolo dell'Appennino Campano-Lucano. Mem. Soc. Geol. It. 1988, 41(2), 1105–1116.

- 1930; 53. Gazzetta Ufficiale del Regno d’Italia (1930).

- Bellomo, M., D’agostino, A. I centri minori tra identità e sviluppo green. Il caso di Aquilonia, in «Upland, Jurnal of urban planning, landscape e enviromental design», 2017, vol. 2, n.1, pp. 165-186.

- Spiga, E.; Porfido, S. Via Casette asismiche; Blurb ed.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-71-463873-4.

- Sistema Irpinia. Available online: https://sistemairpinia.provincia.avellino.it/index.php/it/eventi/aquilonia-palazzine-bene-comune-le-casette-asismiche-di-aquilonia-da-residuo-urbano.

- Crescenti, U.; Nanni, T.; Praturlon, A.; Tomassoni, D. (Institute of Applied Geology of Ancona, Ancona, Italy). Geological Report for the municipality of Bisaccia, 30 December 1980.

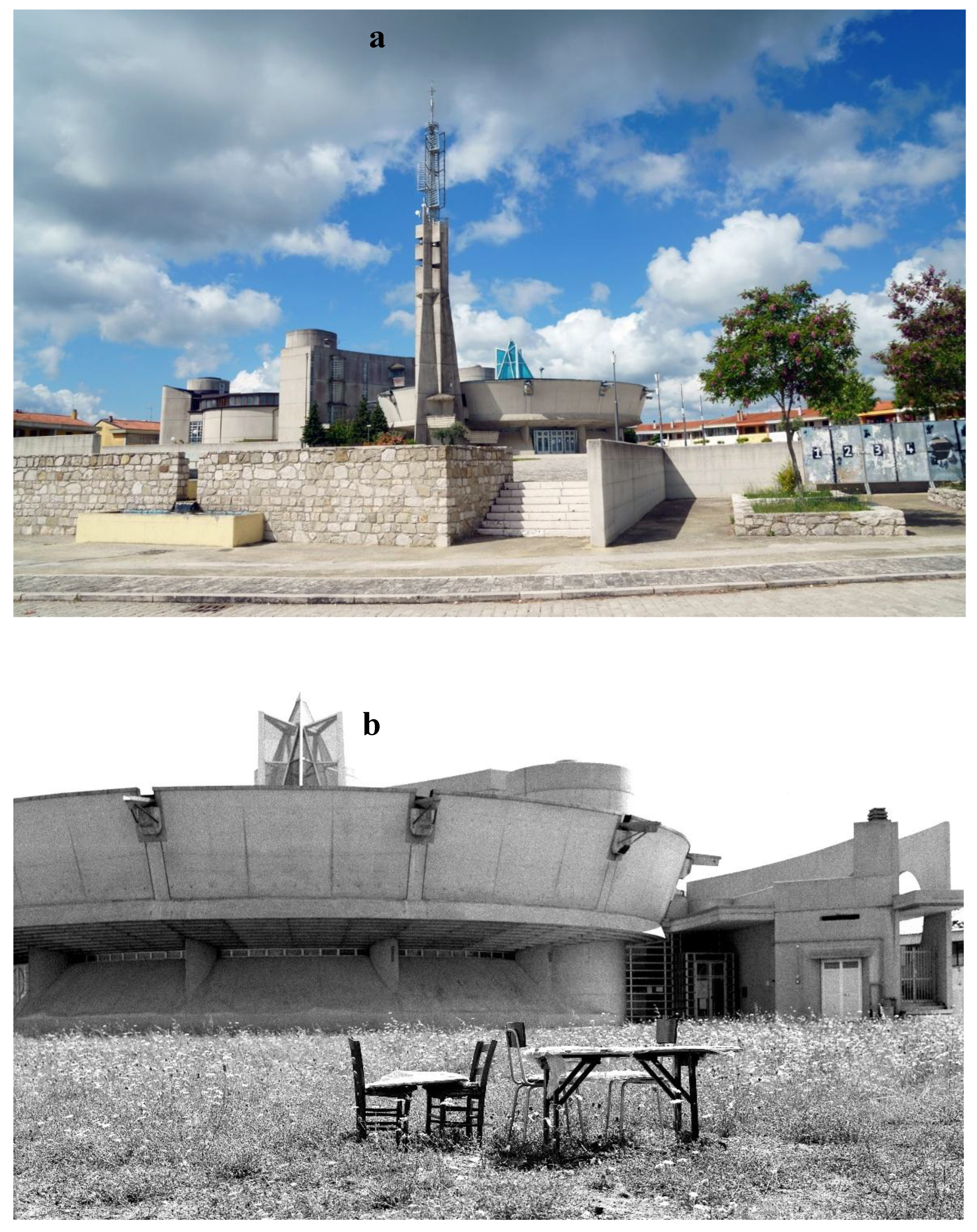

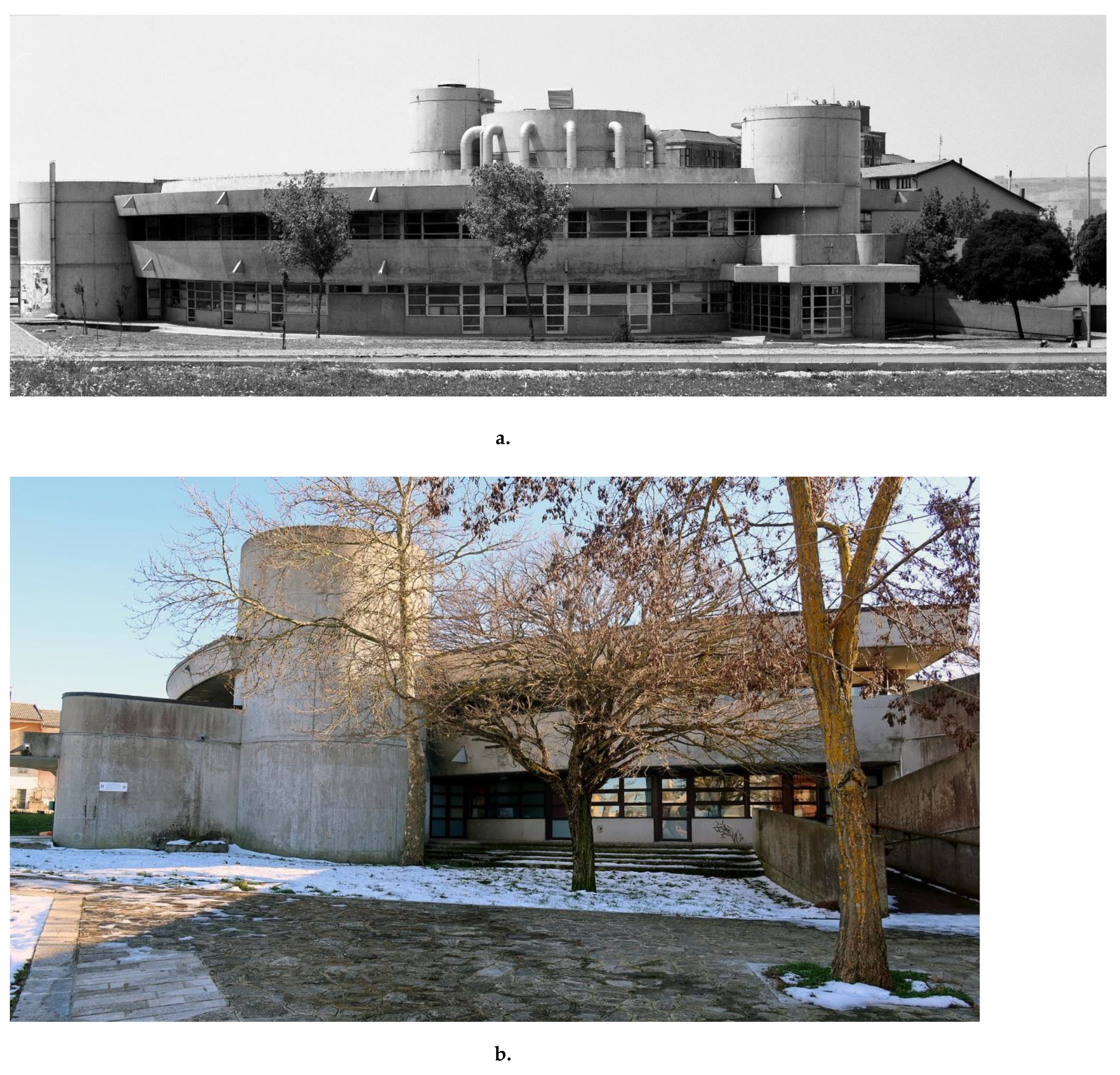

- 58.. Locci, M., Aldo Loris Rossi. La concretezza dell'utopia. Torino, br., pp. 96, 1997, collana: Universale di Architettura. ISBN: 88-86498-18-7.

- Reccia, I., Tesi di laurea Magistrale “Aldo Loris Rossi: l’utopia circolare. Il caso studio di Bisaccia Nuova. Relatore Castagnaro A, Correlatore A. Terminio, Anno 2022-2023. Università degli studi di Napoli “FEDERICO II”- Dipartimento di Aarchitettura.

- Capozzoli A., Paoletti V., Porfido S., Michetti A. M., And Nappi R. The 1688 Sannio–Matese Earthquake: A Dataset of Environmental Effects Based on the ESI-07 Scale, Data, 2025, 10, n. 39.

- De Silva, F.; Antoniciello, M. Sulle Macerie di un’idea di città: una proposta per la rigenerazione urbana a Bisaccia, LaborEst Città Metropolitane, Aree Interne, N. 26/Giugno 2023 Iscr. Trib. di Reggio Cal. n. 12/05- ISSN 1973-7688- ISSN online 2421-3187.

- Picone, G. Paesaggio Con Rovine; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, p. 226, ISBN 978-88-04-72480-3.

- Lombardi, G. Irpinia Earthquake and History: A Nexus as a Problem. Geosciences 2021, 11, 50. [CrossRef]

- Rossi-Doria, M. Scritti sul Mezzogiorno, (riedizione 2003) L'Ancora del Mediterraneo Editor, ISBN-10. 8883250796.

- Ricciardi, T. Spopolamento e desertificazione nell'Appennino meridionale: il caso dell'Alta Irpinia in: Territori spezzati. Spopolamento e abbandono nelle aree interne dell'Italia contemporanea, CISGE, 2019, ISBN: 978-88-940516-5-0.

- Lucatelli, S.; Luisi, D.; Tantillo, F. L'Italia lontana. Una politica per le aree interne, Donzelli Editore, 2022, ISBN: 9788855223386.

- Piano Strategico Nazionale delle Aree Interne 2021-2027 (PSNAI) https://politichecoesione.governo.it/it/documenti-ed-esiti-istituzionali/documenti-strategici-di-inquadramento/programmazione-2021-2027/piano-strategico-nazionale-delle-aree-interne-2021-2027-psnai-e-allegati/.

- Mostra-Convegno “Aldo Loris Rossi a Bisaccia. Visione e concretezza, tra architettura e natura” al Castello Ducale di Bisaccia, sabato 10 maggio 2025.//www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=991705813171117&set=pb.100069951214487.-2207520000.

- Sannazzaro, A.; Del Lungo, S.; Potenza, M. R. and Gizzi, F. T. Revitalizing Inner Areas Through Thematic Cultural Routes an Multifaceted Tourism Experiences. Sustainability, 2025, 17(10), 4701. [CrossRef]

- Hokudan Earthquake Memorial Park. Available online: https://www.japan-experience.com/all-about-japan/kobe/attractions-and-excursions/hokudan-earthquake-memorial-park.

- 921 Earthquake Museum of Taiwan. https://www.reddit.com/r/geology/comments/1n3zcn5/chelungpu_fault_preservation_park_and_921/).

- Mattia, M.; Napoli, M.D.; Scalia, S., Eds. Belìce punto zero; INGV, 2020–2021; ISBN: 9791280282019.

- Petino, G.; Napoli, M.D.; Mattia, M. Landscape, Memory, and Adverse Shocks: The 1968 Earthquake in Belìce Valley (Sicily, Italy): A Case Study. Land 2022, 11, 754. [CrossRef]

- Pianificazione nazionale di emergenza per il rischio vulcanico per i Campi Flegrei (https://www.regione.campania.it/regione/it/campi-flegrei/pianificazione-nazionale-di-emergenza-per-il-rischio-vulcanico-per-i-campi-flegrei).

- Teti, V. La restanza, 2022, Einaudi ed. pp. 168, ISBN 9788806251222.

- Alexander, D. (2013). Natural Disasters (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Dell’Aquila, V. The reconstruction of Gibellina: spatial and social fragmentation in post-earthquake urban plan-ning. Urban Studies Journal, 2017, 54(2), 452-468.

- Cutter, S. L.; Burton, C. G., and Emrich, C. T. Disaster resilience indicators for benchmarking baseline conditions. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 2016, 7(1), 1-22.

- Berti, M., and Simoni, S. Integrating geological and urban planning data to manage hydrogeological and seismic hazards in inner areas. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 389, 121911.

- Lindell, M. K. Disaster Studies. In S. G. Hanson (Ed.), Handbook of Disaster Research, 2013, pp. 9-28, Springer.

- Paton, D. and Johnston, D. (2017). Disaster Resilience: An Integrated Approach. In Community Disaster Resilience (pp. 11-33). Taylor & Francis.

- Lhomme, S.; Serre, D. and Le Coze, J. C. (2015). Resilience and disruption: Lessons from post-disaster urban reconstruction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14, 68-76.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).