Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

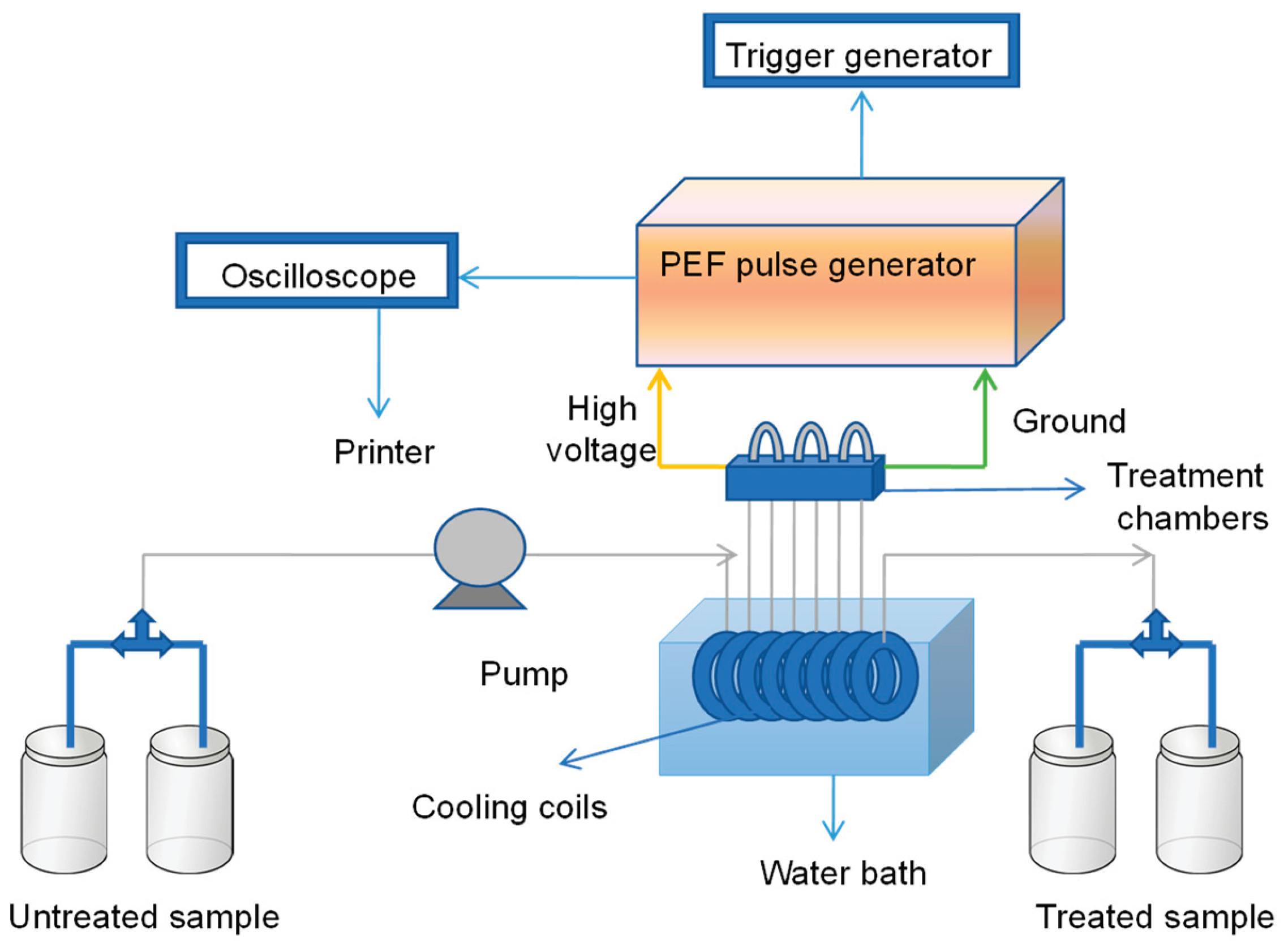

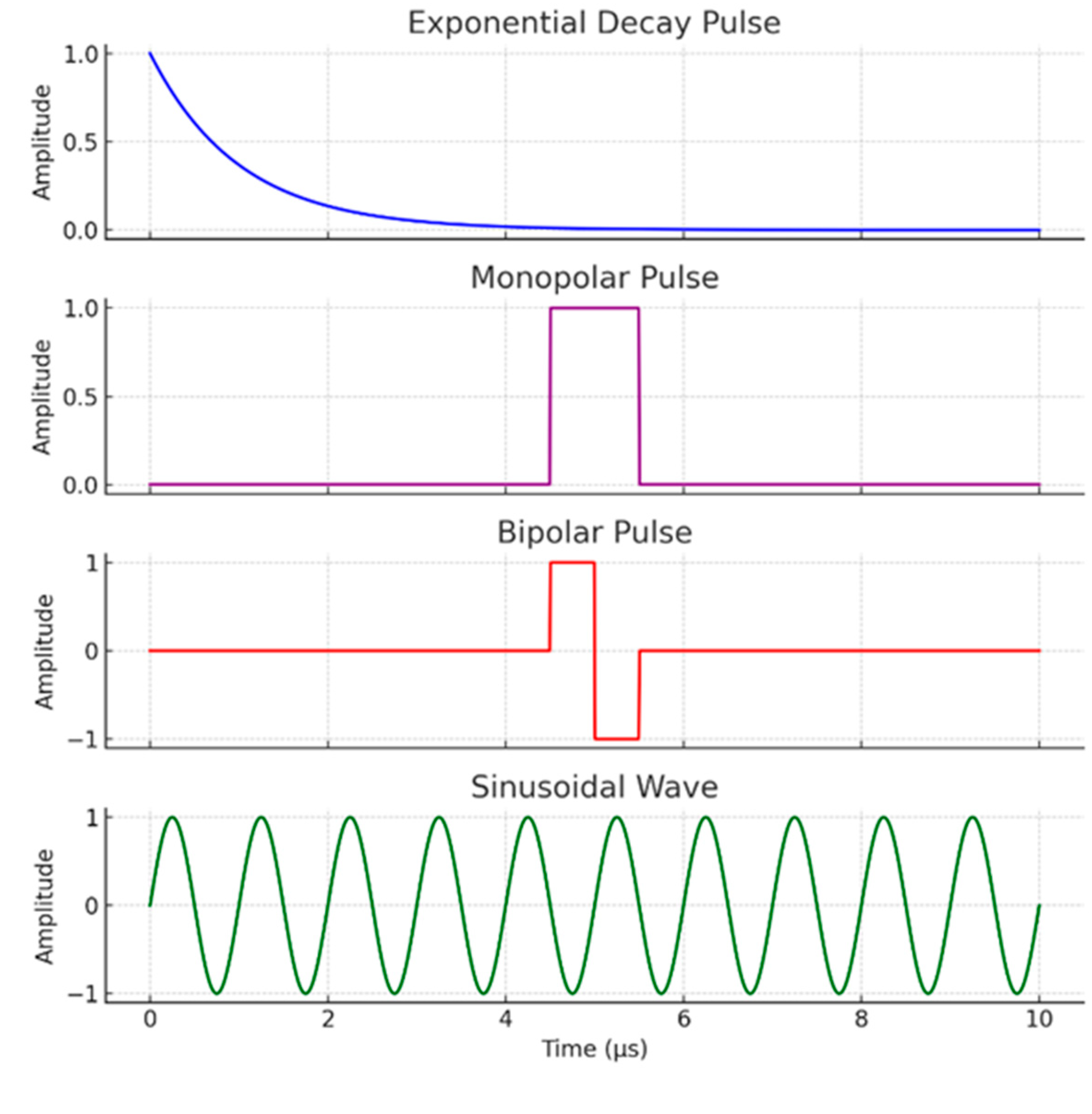

2. Mechanism of Pulsed Electric Fields: Electroporation, Dielectric Breakdown, and Detailed Cellular Effects

2.1. The Biophysical Interaction: Cell Membrane as a Capacitor and Dielectric Breakdown

2.2. Detailed Cellular Effects: A Sequential Process of Permeabilization

2.2.1. Rapid Membrane Charging and Transmembrane Potential Generation

2.2.2. Electrostatic Stress and Mechanical Compression

2.2.3. Nucleation and Formation of Hydrophilic Pores

2.2.4. Enhanced Molecular Transport

3. How PEF-Induced Electroporation Enhances Extraction

3.1. Increased Mass Transfer Rate

3.2. Improved Solvent Penetration

3.3. Reduced Processing Time and Energy Consumption

3.4. Preservation of Thermolabile Compounds

3.5. Higher Yields and Purity

3.6. Reduced Solvent Use and Environmental Impact

4. How PEF Effects on Cell Membrane Aid Drying and Dehydration

Improved Product Quality

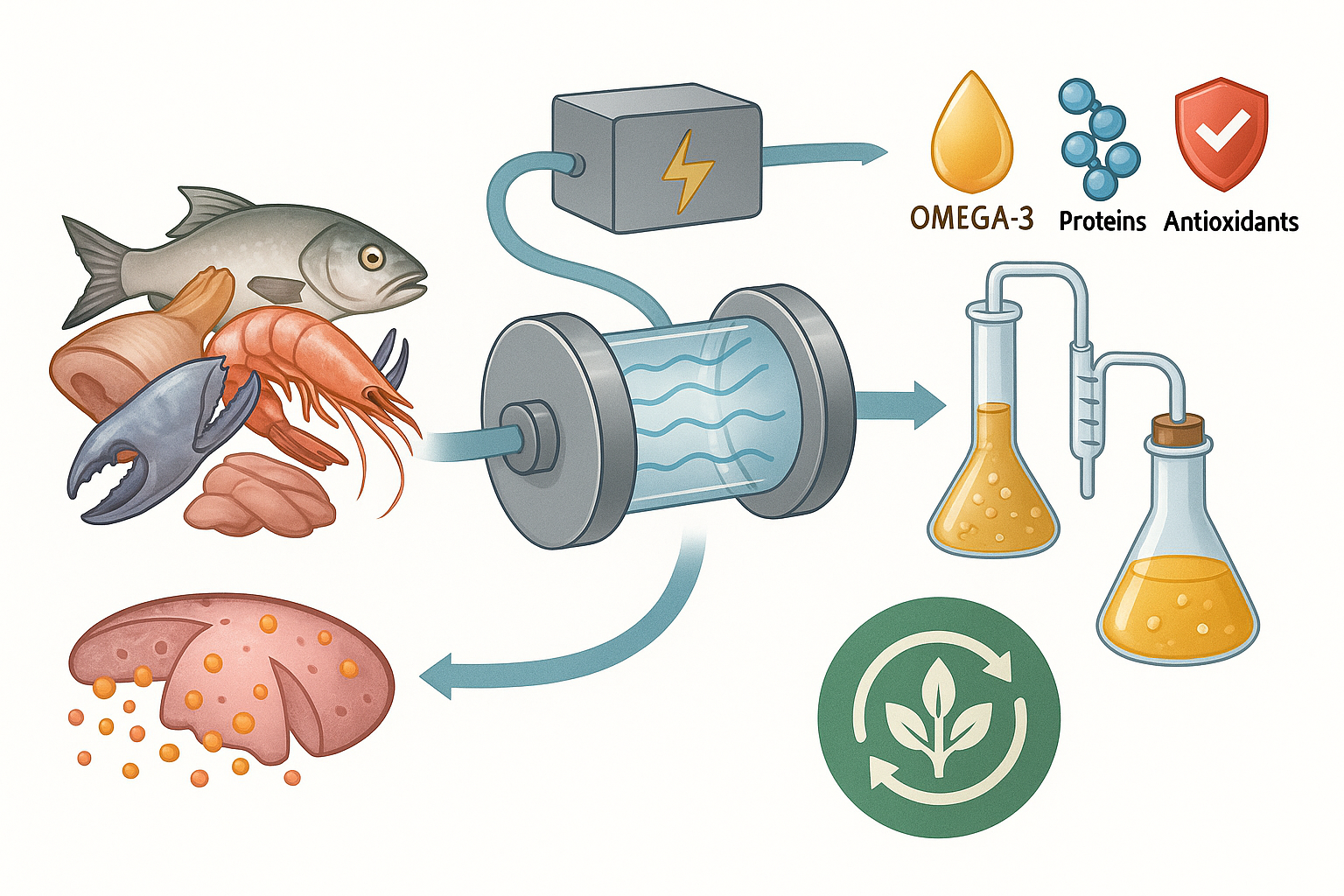

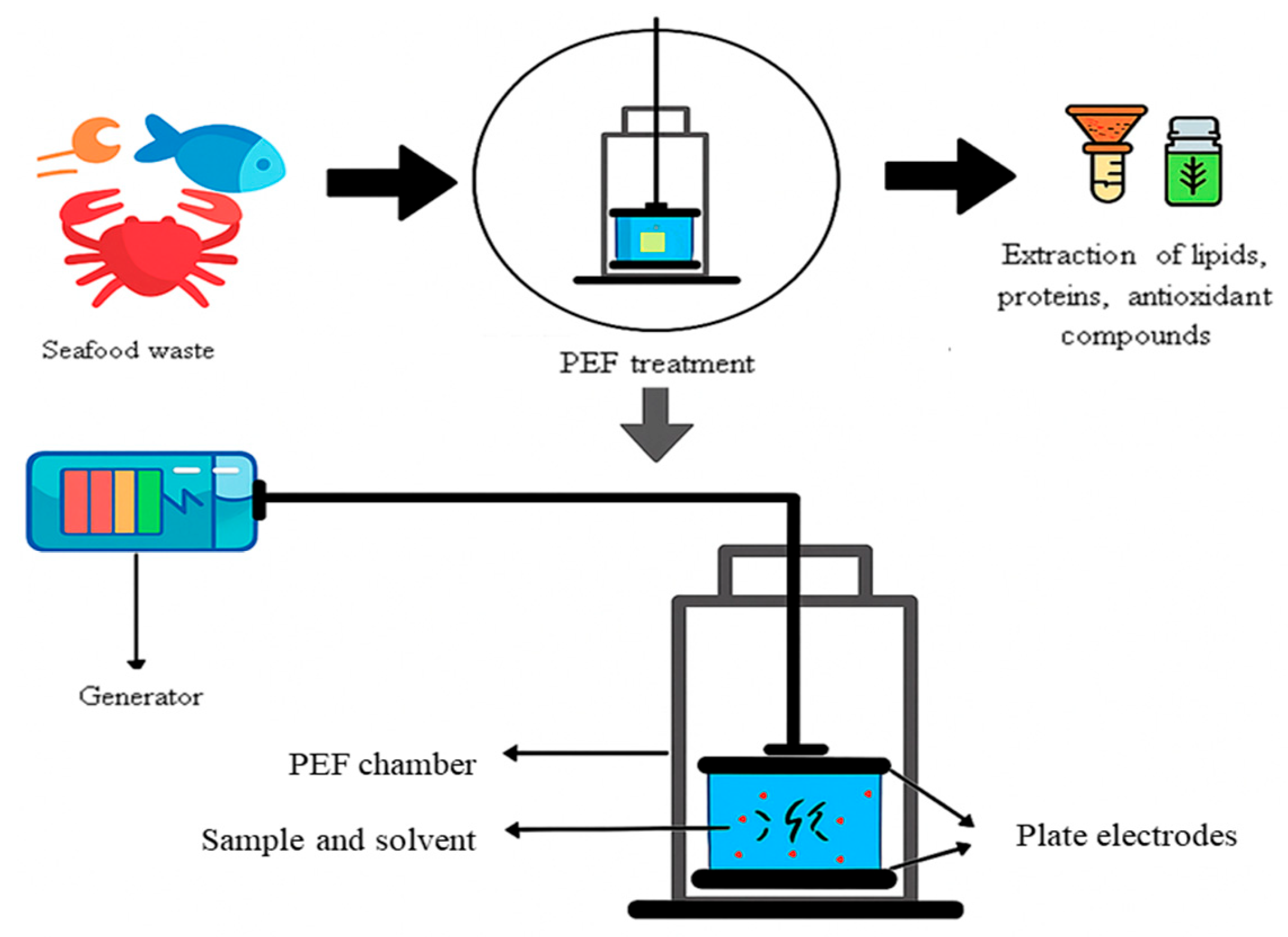

5. Fish By-Products: From Waste to High-Value Resources

6. Protein Recovery and Functionality by Pulsed Electric Fields

7. Antioxidant Recovery Using Pulsed Electric Field Technology

8. Lipid Extraction Using Pulsed Electric Field Technology

9. Comparison of PEF with Alternative Extraction Technologies

10. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 | FAO n.d. https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1696402/ (accessed June 26, 2025). 26 June.

- Venugopal V. Green processing of seafood waste biomass towards blue economy. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 2022;4:100164. [CrossRef]

- Arvanitoyannis IS, Kassaveti A. Fish industry waste: treatments, environmental impacts, current and potential uses. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2008;43:726–45. [CrossRef]

- Brooks MS RV. Fish Processing Wastes as a Potential Source of Proteins, Amino Acids and Oils: A Critical Review. Microb Biochem Technol 2013;05. [CrossRef]

- Ferraro V, Cruz IB, Jorge RF, Malcata FX, Pintado ME, Castro PML. Valorisation of natural extracts from marine source focused on marine by-products: A review. Food Research International 2010;43:2221–33. [CrossRef]

- Rustad T, Storrø I, Slizyte R. Possibilities for the utilisation of marine by-products. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2011;46:2001–14. [CrossRef]

- Dewapriya P, Kim S. Marine microorganisms: An emerging avenue in modern nutraceuticals and functional foods. Food Research International 2014;56:115–25. [CrossRef]

- Kristinsson HG, and Rasco BA. Fish Protein Hydrolysates: Production, Biochemical, and Functional Properties. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2000;40:43–81. [CrossRef]

- Nghia ND. Seafood By-Products in Applications of Biomedicine and Cosmeticuals. Food Processing By-Products and their Utilization, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017, p. 437–70. [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek G. Chapter 14 - Pulsed electric field processing: food pasteurization, tissue treatment, and seed disinfection. In: Jaiswal AK, Shankar S, editors. Food Packaging and Preservation, Academic Press; 2024, p. 259–73. [CrossRef]

- Barba FJ, Parniakov O, Pereira SA, Wiktor A, Grimi N, Boussetta N, et al. Current applications and new opportunities for the use of pulsed electric fields in food science and industry. Food Research International 2015;77:773–98. [CrossRef]

- Yarmush ML, Golberg A, Serša G, Kotnik T, Miklavčič D. Electroporation-Based Technologies for Medicine: Principles, Applications, and Challenges. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 2014;16:295–320. [CrossRef]

- Chatzimitakos T, Athanasiadis V, Kalompatsios D, Mantiniotou M, Bozinou E, Lalas SI. Pulsed Electric Field Applications for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Food Waste and By-Products: A Critical Review. Biomass 2023;3:367–401. [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek G. Pulsed Electric Field Processing of Red Wine: Effect on Wine Quality and Microbial Inactivation. Beverages 2022;8:78. [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek G, Atmaca B, Bulut N, Uzuner S. Development of pulsed electric fields treatment unit to treat wheat grains: Improvement of seed vigour and stress tolerance. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021;185:106129. [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek G, Atmaca B, Bulut N, Uzuner S. Development of pulsed electric fields treatment unit to treat wheat grains: Improvement of seed vigour and stress tolerance. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021;185:106129. [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek G, Hitit Özkan B. Pulsed electric field processing of fruit juices with inactivation of enzymes with new inactivation kinetic model and determination of changes in quality parameters. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2024;94:103678. [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek G. Pulsed electric field treatment for beverage production and preservation. Springer International Publishing; 2017. [CrossRef]

- Akdemir Evrendilek G, Tanasov I. Configuring pulsed electric fields to treat seeds: an innovative method of seed disinfection. Seed Science and Technology 2017;45:72–80. [CrossRef]

- Lebovka N, Vorobiev E, Chemat F. Enhancing Extraction Processes in the Food Industry. CRC Press; 2016.

- Toepfl S, Heinz V, Knorr D. Applications of Pulsed Electric Fields Technology for the Food Industry. In: Raso J, Heinz V, editors. Pulsed Electric Fields Technology for the Food Industry: Fundamentals and Applications, Boston, MA: Springer US; 2006, p. 197–221. [CrossRef]

- Ganjeh AM, Saraiva JA, Pinto CA, Casal S, Silva AMS. Emergent technologies to improve protein extraction from fish and seafood by-products: An overview. Applied Food Research 2023;3:100339. [CrossRef]

- He G, Yan X, Wang X, Wang Y. Extraction and structural characterization of collagen from fishbone by high intensity pulsed electric fields. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2019;42:e13214. [CrossRef]

- Sarangapani C, Patange A, Bourke P, Keener K, Cullen PJ. Recent Advances in the Application of Cold Plasma Technology in Foods. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 2018;9:609–29. [CrossRef]

- Azelee NIW, Dahiya D, Ayothiraman S, Noor NM, Rasid ZIA, Ramli ANM, et al. Sustainable valorization approaches on crustacean wastes for the extraction of chitin, bioactive compounds and their applications - A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023;253:126492. [CrossRef]

- López N, Puértolas E, Condón S, Raso J, Alvarez I. Enhancement of the extraction of betanine from red beetroot by pulsed electric fields. Journal of Food Engineering 2009;90:60–6. [CrossRef]

- López N, Puértolas E, Condón S, Álvarez I, Raso J. Effects of pulsed electric fields on the extraction of phenolic compounds during the fermentation of must of Tempranillo grapes. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2008;9:477–82. [CrossRef]

- Choton S, Bandral JD, Sood M, Gupta N, Singh J, Langeh A, et al. Green Extraction Technology and Its Application in Food Industry 2023.

- Matos GS, Pereira SG, Genisheva ZA, Gomes AM, Teixeira JA, Rocha CMR. Advances in Extraction Methods to Recover Added-Value Compounds from Seaweeds: Sustainability and Functionality. Foods 2021;10:516. [CrossRef]

- Wen L, Zhang ,Zhihang, Sun ,Da-Wen, Sivagnanam ,Saravana Periaswamy, and Tiwari BK. Combination of emerging technologies for the extraction of bioactive compounds. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020;60:1826–41. [CrossRef]

- Naliyadhara N, Kumar A, Girisa S, Daimary UD, Hegde M, Kunnumakkara AB. Pulsed electric field (PEF): Avant-garde extraction escalation technology in food industry. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022;122:238–55. [CrossRef]

- Yan B, Li ,Jian, Liang ,Qi-Chun, Huang ,Yanyan, Cao ,Shi-Lin, Wang ,Lang-Hong, et al. From Laboratory to Industry: The Evolution and Impact of Pulsed Electric Field Technology in Food Processing. Food Reviews International 2025;41:373–98. [CrossRef]

- Barba FJ, Saraiva JMA, Cravotto G, Lorenzo JM. Innovative Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing, Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds. Woodhead Publishing; 2019.

- Vorobiev E, Lebovka N. Processing of Foods and Biomass Feedstocks by Pulsed Electric Energy. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Seyedi M. Biological cell response to electric field: a review of equivalent circuit models and future challenges. Biomed Phys Eng Express 2025;11:022001. [CrossRef]

- Bidirectional Modulation on Electroporation Induced by Membrane Tension Under the Electric Field | ACS Omega n.d. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acsomega.4c07396 (accessed June 26, 2025). 26 June.

- Ellappan P, Sundararajan R. A simulation study of the electrical model of a biological cell. Journal of Electrostatics 2005;63:297–307. [CrossRef]

- Weaver JC. Electroporation of biological membranes from multicellular to nano scales. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2003;10:754–68. [CrossRef]

- Weaver JC, Chizmadzhev YuA. Theory of electroporation: A review. Bioelectrochemistry and Bioenergetics 1996;41:135–60. [CrossRef]

- Ye P, Huang L, Zhao K. Bidirectional Modulation on Electroporation Induced by Membrane Tension Under the Electric Field. ACS Omega 2024;9:50458–6. [CrossRef]

- Marín-Sánchez J, Berzosa A, Álvarez I, Raso J, Sánchez-Gimeno C. Yeast protein extraction assisted by Pulsed Electric Fields: Balancing electroporation and recovery. Food Hydrocolloids 2025;168:111527. [CrossRef]

- Chang D. Guide to Electroporation and Electrofusion. Academic Press; 1991.

- Chang L, Li L, Shi J, Sheng Y, Lu W, Gallego-Perez D, et al. Micro-/nanoscale electroporation. Lab Chip 2016;16:4047–62. [CrossRef]

- Saulis, G. Electroporation of Cell Membranes: The Fundamental Effects of Pulsed Electric Fields in Food Processing. Food Eng Rev 2010;2:52–73. [CrossRef]

- Kotnik T, Rems L, Tarek M, Miklavčič D. Membrane Electroporation and Electropermeabilization: Mechanisms and Models. Annual Review of Biophysics 2019;48:63–91. [CrossRef]

- Esser AT, Smith KC, Gowrishankar TR, Vasilkoski Z, Weaver JC. Mechanisms for the Intracellular Manipulation of Organelles by Conventional Electroporation. Biophysical Journal 2010;98:2506–14. [CrossRef]

- Son RS, Smith KC, Gowrishankar TR, Vernier PT, Weaver JC. Basic Features of a Cell Electroporation Model: Illustrative Behavior for Two Very Different Pulses. J Membrane Biol 2014;247:1209–28. [CrossRef]

- Ranjha MMAN, Kanwal R, Shafique B, Arshad RN, Irfan S, Kieliszek M, et al. A Critical Review on Pulsed Electric Field: A Novel Technology for the Extraction of Phytoconstituents. Molecules 2021;26:4893. [CrossRef]

- Franco D, Munekata PES, Agregán R, Bermúdez R, López-Pedrouso M, Pateiro M, et al. Application of Pulsed Electric Fields for Obtaining Antioxidant Extracts from Fish Residues. Antioxidants 2020;9:90. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Gu X, Xu G, Fu X. Improving the lipid extraction yield from Chlorella based on the controllable electroporation of cell membrane by pulsed electric field. Bioresource Technology 2021;330:124933. [CrossRef]

- Hai A, AlYammahi J, Bharath G, Rambabu K, Hasan SW, Banat F. Extraction of nutritious sugar by cell membrane permeabilization and electroporation of biomass using a moderate electric field: parametric optimization and kinetic modeling. Biomass Conv Bioref 2024;14:19187–202. [CrossRef]

- Zhao F, Wang Z, Huang H. Physical Cell Disruption Technologies for Intracellular Compound Extraction from Microorganisms. Processes 2024;12:2059. [CrossRef]

- Yudhister, Shams R, Dash KK. Valorization of Food Waste Using Pulsed Electric Fields: Applications in Diverse Food Categories. Food Bioprocess Technol 2025;18:2218–35. [CrossRef]

- Bao G, Tian Y, Wang K, Chang Z, Jiang Y, Wang J. Mechanistic understanding of the improved drying characteristics and quality attributes of lily (Lilium lancifolium Thunb.) by modified microstructure after pulsed electric field (PEF) pretreatment. Food Research International 2024;190:114660. [CrossRef]

- Rahaman A, Mishra AK, Kumari A, Farooq MA, Alee M, Khalifa I, et al. Impact of pulsed electric fields on membrane disintegration, drying, and osmotic dehydration of foods. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2024;47:e14552. [CrossRef]

- Jeong S-H, Lee H-B, Park G-S, Shahbaz HM, Lee D-U. Effects of pulsed electric field (PEF) treatment on the mass transfer of NaCl and moisture in radish tissues (Raphanus sativus L.): Accelerating diffusion rates while maintaining intact microstructure 2024. [CrossRef]

- Llavata B, Collazos-Escobar GA, García-Pérez JV, Cárcel JA. PEF pre-treatment and ultrasound-assisted drying at different temperatures as a stabilizing method for the up-cycling of kiwifruit: Effect on drying kinetics and final quality. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2024;92:103591. [CrossRef]

- Giancaterino M, Werl C, Jaeger H. Evaluation of the quality and stability of freeze-dried fruits and vegetables pre-treated by pulsed electric fields (PEF). LWT 2024;191:11565. [CrossRef]

- Nowacka M, Tappi S, Wiktor A, Rybak K, Miszczykowska A, Czyzewski J, et al. The Impact of Pulsed Electric Field on the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Beetroot. Foods 2019;8:244. [CrossRef]

- Gao X, Wang,Zichen, Sun,Guoxiu, Zhao,Yuting, Tang,Shuwei, Zhu,Hongguang, et al. Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Technology for Preserving Fruits and Vegetables: Applications, Benefits, and Comparisons. Food Reviews International n.d.:1–26. [CrossRef]

- Masztalerz K, Lech K, Dróżdż T, Figiel A, Pratap-Singh A. Effect of electric and electromagnetic fields on energy consumption, texture, and microstructure of dried black garlic. Journal of Food Engineering 2024;375:112056. [CrossRef]

- Papachristou I, Nazarova N, Wüstner R, Lina R, Frey W, Silve A. Biphasic lipid extraction from microalgae after PEF-treatment reduces the energy demand of the downstream process. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod 2025;18:12. [CrossRef]

- Drudi F, Oey I, Leong SY, King J, Sutton K, Tylewicz U. New opportunity of using pulsed electric field (PEF) technology to produce texture-modified chickpea flour-based gels for people with dysphagia. Food Hydrocolloids 2025;168:111575. [CrossRef]

- Genovese J, Rocculi P, Miklavčič D, Mahnič-Kalamiza S. The forgotten method? Pulsed electric field thresholds from the perspective of texture analysis. Food Research International 2024;176:113869. [CrossRef]

- Gao X, Wang, Z, Sun G, Zhao Y, Tang S, Zhu H, Li Z. Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Technology for Preserving Fruits and Vegetables: Applications, Benefits, and Comparisons. Food Reviews International n.d.;0:1–26. [CrossRef]

- Aspevik T, Oterhals Å, Rønning SB, Altintzoglou T, Wubshet SG, Gildberg A, et al. Valorization of Proteins from Co- and By-Products from the Fish and Meat Industry. In: Lin CSK, editor. Chemistry and Chemical Technologies in Waste Valorization, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018, p. 123–50. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan SR, Jeong C-R, Park J-W, Cho S-S, Kim S-J. A review on the processing of functional proteins or peptides derived from fish by-products and their industrial applications. Heliyon 2023;9. [CrossRef]

- Action, SI. World fisheries and aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organization 2020;2020:1–244.

- Karayannakidis PD, Zotos A. Fish Processing By-Products as a Potential Source of Gelatin: A Review. Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology 2016;25:65–92. [CrossRef]

- Sampantamit T, Ho L, Lachat C, Hanley-Cook G, Goethals P. The Contribution of Thai Fisheries to Sustainable Seafood Consumption: National Trends and Future Projections. Foods 2021;10:880. [CrossRef]

- Benjakul S, Yarnpakdee S, Senphan T, Halldorsdottir SM, Kristinsson HG. Fish protein hydrolysates. Antioxidants and Functional Components in Aquatic Foods, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014, p. 237–81. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Peraza RS, Osuna-Ruiz I, Lugo-Sánchez ME, Pacheco-Aguilar R, Ramírez-Suárez JC, Burgos-Hernández A, et al. Structural and biological properties of protein hydrolysates from seafood by-products: a review focused on fishery effluents. Food Sci Technol 2020;40:1–5. [CrossRef]

- Nikoo M, Regenstein JM, Yasemi M. Protein Hydrolysates from Fishery Processing By-Products: Production, Characteristics, Food Applications, and Challenges. Foods 2023;12:4470. [CrossRef]

- Sila A, Bougatef A. Antioxidant peptides from marine by-products: Isolation, identification and application in food systems. A review. Journal of Functional Foods 2016;21:10–26. [CrossRef]

- Al Khawli F, Pateiro M, Domínguez R, Lorenzo JM, Gullón P, Kousoulaki K, et al. Innovative Green Technologies of Intensification for Valorization of Seafood and Their By-Products. Marine Drugs 2019;17:689. [CrossRef]

- Ghalamara S, Silva S, Brazinha C, Pintado M. Valorization of Fish by-Products: Purification of Bioactive Peptides from Codfish Blood and Sardine Cooking Wastewaters by Membrane Processing. Membranes 2020;10:44. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente B, Pallarés N, Berrada H, Barba FJ. Salmon (Salmo salar) Side Streams as a Bioresource to Obtain Potential Antioxidant Peptides after Applying Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE). Marine Drugs 2021;19:323. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente B, Pallarés N, Berrada H, Barba FJ. Development of Antioxidant Protein Extracts from Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata) Side Streams Assisted by Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE). Marine Drugs 2021;19:199. [CrossRef]

- Ghaly AE, Ramakrishnan VV, Brooks MS, Budge SM, Dave D. Fish Processing Wastes as a Potential Source of Proteins, Amino Acids and Oils: A Critical Review. Journal of Microbial & Biochemical Technology 2013;5:107–29. [CrossRef]

- Ganeva V, Galutzov B, Teissié J. High yield electroextraction of proteins from yeast by a flow process. Analytical Biochemistry 2003;315:77–84. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Lin J, Chen J, Fang T. Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction of Protein from Abalone (Haliotis Discus Hannai Ino) Viscera. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2016;39:702–10. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Canovas GV, Pierson MD, Zhang QH, Schaffner DW. Pulsed Electric Fields. Journal of Food Science 2000;65:65–79. [CrossRef]

- Grimi N, Dubois A, Marchal L, Jubeau S, Lebovka NI, Vorobiev E. Selective extraction from microalgae Nannochloropsis sp. using different methods of cell disruption. Bioresource Technology 2014;153:254–9. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Berrada H, Wang M, Zhou J, Kousoulaki K, Barba FJ, et al. Is Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) a Useful Tool for the Valorization of Solid and Liquid Sea Bass Side Streams?: Evaluation of Nutrients and Contaminants. Food Bioprocess Technol 2025;18:1873–92. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Chen Z, Mo H. Effects of pulsed electric fields on physicochemical properties of soybean protein isolates. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2007;40:1167–75. [CrossRef]

- Mingyuan, L. Optimization of extraction parameters for protein from beer waste brewing yeast treated by pulsed electric fields (PEF). Afr J Microbiol Res 2012;6. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Gouyo T, Grimi N, Bals O, Vorobiev E. Pulsed electric field pretreatment of rapeseed green biomass (stems) to enhance pressing and extractives recovery. Bioresource Technology 2016;199:194–201. [CrossRef]

- Sarkis JR, Boussetta N, Blouet C, Tessaro IC, Marczak LDF, Vorobiev E. Effect of pulsed electric fields and high voltage electrical discharges on polyphenol and protein extraction from sesame cake. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2015;29:170–7. [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke DP, Mercali GD, Marczak LDF, Müller G, Frey W, Gusbeth C. Extraction of valuable compounds from Arthrospira platensis using pulsed electric field treatment. Bioresource Technology 2019;283:207–12. [CrossRef]

- Sampedro F, Rodrigo D, Martínez A, Barbosa-Cánovas GV, Rodrigo M. Review: Application of Pulsed Electric Fields in Egg and Egg Derivatives. Food Sci Technol Int 2006;12:397–405. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh S, Gillis A, Sheviryov J, Levkov K, Golberg A. Towards waste meat biorefinery: Extraction of proteins from waste chicken meat with non-thermal pulsed electric fields and mechanical pressing. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019;208:220–31. [CrossRef]

- Bhat ZF, Morton JD, Mason SL, Bekhit AE-DA. Pulsed electric field operates enzymatically by causing early activation of calpains in beef during ageing. Meat Science 2019;153:144–51. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, He Q, Zhou D. Optimization Extraction of Protein from Mussel by High-Intensity Pulsed Electric Fields. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2017;41:e12962. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Zhan N, Zhang M, Wang S. Optimization of extraction process of taurine from mussel meat with pulsed electric field assisted enzymatic hydrolysis. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2021;45:e15715. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Zhou J, Collado MC, Barba FJ. Accelerated Solvent Extraction and Pulsed Electric Fields for Valorization of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and Sole (Dover sole) By-Products: Protein Content, Molecular Weight Distribution and Antioxidant Potential of the Extracts. Marine Drugs 2021;19:207. [CrossRef]

- Hermawan N, Akdemir Evrendilek G, Dantzer W r., Zhang Q h., Richter E r. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment of Liquid Whole Egg Inoculated with Salmonella Enteritidis. Journal of Food Safety 2004;24:71–85. [CrossRef]

- Coustets M, Joubert-Durigneux V, Hérault J, Schoefs B, Blanckaert V, Garnier J-P, et al. Optimization of protein electroextraction from microalgae by a flow process. Bioelectrochemistry 2015;103:74–81. [CrossRef]

- Coustets M, Al-Karablieh N, Thomsen C, Teissié J. Flow Process for Electroextraction of Total Proteins from Microalgae. J Membrane Biol 2013;246:751–60. [CrossRef]

- Luengo E, Martínez JM, Álvarez I, Raso J. Effects of millisecond and microsecond pulsed electric fields on red beet cell disintegration and extraction of betanines. Industrial Crops and Products 2016;84:28–33. [CrossRef]

- Parniakov O, Barba FJ, Grimi N, Marchal L, Jubeau S, Lebovka N, et al. Pulsed electric field and pH assisted selective extraction of intracellular components from microalgae Nannochloropsis. Algal Research 2015;8:128–34. [CrossRef]

- Batista AP, Gouveia L, Bandarra NM, Franco JM, Raymundo A. Comparison of microalgal biomass profiles as novel functional ingredient for food products. Algal Research 2013;2:164–73. [CrossRef]

- Postma PR, Pataro G, Capitoli M, Barbosa MJ, Wijffels RH, Eppink MHM, et al. Selective extraction of intracellular components from the microalga Chlorella vulgaris by combined pulsed electric field–temperature treatment. Bioresource Technology 2016;203:80–8. [CrossRef]

- Lam GP‘t, van der Kolk JA, Chordia A, Vermuë MH, Olivieri G, Eppink MHM, et al. Mild and Selective Protein Release of Cell Wall Deficient Microalgae with Pulsed Electric Field. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng 2017;5:6046–53. [CrossRef]

- Parniakov O, Barba FJ, Grimi N, Lebovka N, Vorobiev E. Impact of pulsed electric fields and high voltage electrical discharges on extraction of high-added value compounds from papaya peels. Food Research International 2014;65:337–43. [CrossRef]

- Selvamuthukumaran M, Shi J. Recent advances in extraction of antioxidants from plant by-products processing industries. Food Quality and Safety 2017;1:61–81. [CrossRef]

- Grigorakis, K. Compositional and organoleptic quality of farmed and wild gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) and sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and factors affecting it: A review. Aquaculture 2007;272:55–75. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Martínez AJ, Mandić AI, Bantis F, Böhm V, Borge GIA., Brnčić M, et al. A comprehensive review on carotenoids in foods and feeds: status quo, applications, patents, and research needs. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022;62:1999–2049. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Martínez AJ, Böhm V, Borge GIA, Cano MP, Fikselová M, Gruskiene R, et al. Carotenoids: Considerations for Their Use in Functional Foods, Nutraceuticals, Nutricosmetics, Supplements, Botanicals, and Novel Foods in the Context of Sustainability, Circular Economy, and Climate Change. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 2021;12:433–60. [CrossRef]

- De Aguiar Saldanha Pinheiro AC, Martí-Quijal FJ, Barba FJ, Benítez-González AM, Meléndez-Martínez AJ, Castagnini JM, et al. Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) and Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) for Valorization of Red (Aristeus antennatus) and Camarote (Melicertus kerathurus) Shrimp Side Streams: Antioxidant and HPLC Evaluation of the Carotenoid Astaxanthin Recovery. Antioxidants 2023;12:406. [CrossRef]

- Gulzar S, Raju N, Chandragiri Nagarajarao R, Benjakul S. Oil and pigments from shrimp processing by-products: Extraction, composition, bioactivities and its application- A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2020;100:307–19. [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud Amiguet V, Kramp KL, Mao J, McRae C, Goulah A, Kimpe LE, et al. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of polyunsaturated fatty acids from Northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis Kreyer) processing by-products. Food Chemistry 2012;130:853–8. [CrossRef]

- Naguib YMA. Antioxidant Activities of Astaxanthin and Related Carotenoids. J Agric Food Chem 2000;48:1150–4. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Estaca J, Calvo MM, Álvarez-Acero I, Montero P, Gómez-Guillén MC. Characterization and storage stability of astaxanthin esters, fatty acid profile and α-tocopherol of lipid extract from shrimp (L. vannamei) waste with potential applications as food ingredient. Food Chemistry 2017;216:37–44. [CrossRef]

- Golberg A, Sack M, Teissie J, Pataro G, Pliquett U, Saulis G, et al. Energy-efficient biomass processing with pulsed electric fields for bioeconomy and sustainable development. Biotechnol Biofuels 2016;9:94. [CrossRef]

- Eing C, Goettel M, Straessner R, Gusbeth C, Frey W. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment of Microalgae—Benefits for Microalgae Biomass Processing. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2013;41:2901–7. [CrossRef]

- Lai YS, Parameswaran P, Li A, Baez M, Rittmann BE. Effects of pulsed electric field treatment on enhancing lipid recovery from the microalga, Scenedesmus. Bioresource Technology 2014;173:457–61. [CrossRef]

- Carullo D, Abera BD, Scognamiglio M, Donsì F, Ferrari G, Pataro G. Application of Pulsed Electric Fields and High-Pressure Homogenization in Biorefinery Cascade of C. vulgaris Microalgae. Foods 2022;11:471. [CrossRef]

- Einarsdóttir R, Þórarinsdóttir KA, Aðalbjörnsson BV, Guðmundsson M, Marteinsdóttir G, Kristbergsson K. Extraction of bioactive compounds from Alaria esculenta with pulsed electric field. J Appl Phycol 2022;34:597–608. [CrossRef]

- Einarsdóttir R, Þórarinsdóttir KA, Aðalbjörnsson BV, Guðmundsson M, Marteinsdóttir G, Kristbergsson K. The effect of pulsed electric field-assisted treatment parameters on crude aqueous extraction of Laminaria digitata. J Appl Phycol 2021;33:3287–96. [CrossRef]

- Käferböck A, Smetana S, de Vos R, Schwarz C, Toepfl S, Parniakov O. Sustainable extraction of valuable components from Spirulina assisted by pulsed electric fields technology. Algal Research 2020;48:101914. [CrossRef]

- Kokkali M, Martí-Quijal FJ, Taroncher M, Ruiz M-J, Kousoulaki K, Barba FJ. Improved Extraction Efficiency of Antioxidant Bioactive Compounds from Tetraselmis chuii and Phaedoactylum tricornutum Using Pulsed Electric Fields. Molecules 2020;25:3921. [CrossRef]

- Goettel M, Eing C, Gusbeth C, Straessner R, Frey W. Pulsed electric field assisted extraction of intracellular valuables from microalgae. Algal Research 2013;2:401–8. [CrossRef]

- Kotnik T, Frey W, Sack M, Meglič SH, Peterka M, Miklavčič D. Electroporation-based applications in biotechnology. Trends in Biotechnology 2015;33:480–8. [CrossRef]

- Zbinden MDA, Sturm BSM, Nord RD, Carey WJ, Moore D, Shinogle H, et al. Pulsed electric field (PEF) as an intensification pretreatment for greener solvent lipid extraction from microalgae. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2013;110:1605–15. [CrossRef]

- Perez B, Weber N, Haberkorn I, Mathys A. Reversible electropermeabilization of Auxenochlorella protothecoides microalgae: tracking mass transfer and membrane resealing dynamics induced by pulsed electric fields. Algal Research 2025;90:104125. [CrossRef]

- Majid I, Nayik GA, Nanda V. Ultrasonication and food technology: A review. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2015;1:1071022. [CrossRef]

- Yusaf T, Al-Juboori RA. Alternative methods of microorganism disruption for agricultural applications. Applied Energy 2014;114:909–23. [CrossRef]

- Reddy AVB, Moniruzzaman M, Madhavi V, Jaafar J. Chapter 8 - Recent improvements in the extraction, cleanup and quantification of bioactive flavonoids. In: Atta-ur-Rahman, editor. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, vol. 66, Elsevier; 2020, p. 197–223. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Weller CL. Recent advances in extraction of nutraceuticals from plants. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2006;17:300–12. [CrossRef]

- Puri M, Sharma D, Barrow CJ. Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactives from plants. Trends in Biotechnology 2012;30:37–44. [CrossRef]

- Boussetta N, Soichi E, Lanoisellé J-L, Vorobiev E. Valorization of oilseed residues: Extraction of polyphenols from flaxseed hulls by pulsed electric fields. Industrial Crops and Products 2014;52:347–53. [CrossRef]

- Lončarić A, Celeiro M, Jozinović A, Jelinić J, Kovač T, Jokić S, et al. Green Extraction Methods for Extraction of Polyphenolic Compounds from Blueberry Pomace. Foods 2020;9:1521. [CrossRef]

- Schilling S, Alber T, Toepfl S, Neidhart S, Knorr D, Schieber A, et al. Effects of pulsed electric field treatment of apple mash on juice yield and quality attributes of apple juices. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2007;8:127–34. [CrossRef]

- Teh S-S, Niven BE, Bekhit AE-DA, Carne A, Birch J. Optimization of polyphenol extraction and antioxidant activities of extracts from defatted flax seed cake (Linum usitatissimum L.) using microwave-assisted and pulsed electric field (PEF) technologies with response surface methodology. Food Sci Biotechnol 2015;24:1649–59. [CrossRef]

- Hou J, He S, Ling M, Li W, Dong R, Pan Y, et al. A method of extracting ginsenosides from Panax ginseng by pulsed electric field. Journal of Separation Science 2010;33:2707–13. [CrossRef]

- Martínez JM, Gojkovic Z, Ferro L, Maza M, Álvarez I, Raso J, et al. Use of pulsed electric field permeabilization to extract astaxanthin from the Nordic microalga Haematococcus pluvialis. Bioresour Technol 2019;289:121694. [CrossRef]

- Girisa S, Kumar A, Rana V, Parama D, Daimary UD, Warnakulasuriya S, et al. From Simple Mouth Cavities to Complex Oral Mucosal Disorders—Curcuminoids as a Promising Therapeutic Approach. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2021;4:647–65. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Tomar M, Punia S, Amarowicz R, Kaur C. Evaluation of Cellulolytic Enzyme-Assisted Microwave Extraction of Punica granatum Peel Phenolics and Antioxidant Activity. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2020;75:614–20. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Rawson A, Kumar A, Ck S, Vignesh S, Venkatachalapathy N. Lycopene extraction from industrial tomato processing waste using emerging technologies, and its application in enriched beverage development. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2023;58:2141–50. [CrossRef]

- Le-Tan H, Fauster T, Vladic J, Gerhardt T, Haas K, Jaeger H. Application of Emerging Cell Disintegration Techniques for the Accelerated Recovery of Curcuminoids from Curcuma longa. Applied Sciences 2021;11:8238. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).