Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- the number of spectral components increases the complexity of data processing during preparation, training, and inference [5],

- high correlation between the individual bands and added redundancy [17],

- limited number of benchmark ground truth labeled datasets for monitoring sustainable and regenerative agriculture practices, and

- limited ability of the models to generalize to small plot sizes or new regions or new classes or new context different from training.

1.1. Problem Formulation

1.2. Notation Conventions

- Scalars: regular italic (e.g., x, )

- Vectors: bold lowercase (e.g., , )

- Matrices: bold uppercase (e.g., , )

- Sets: calligraphic uppercase (e.g., , )

- Tensors: bold sans-serif (e.g., )

1.3. Contributions

- A lightweight framework that introduces a tunable balance between spectral similarity and spatial nearness, with minimal computational overhead.

- An efficient weighting mechanism requiring the tuning of at most two dataset-specific parameters (C, ) while maintaining four fixed parameters (r, , , ) transferable across domains, allowing training with only labeled data. Specifically, only C (SVM regularization) requires dataset-specific tuning, with optionally fine-tuned for improved accuracy as demonstrated in Section 3.3.

- The pixel-based classifier with neighborhood has no patch-based processing, hence applicable to small landholding farm sizes.

- Demonstration of domain generalization capabilities by training on one benchmark dataset (Indian Pines) and successfully inferring on three different datasets viz. the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), Hyperion Botswana and Salinas-A, without retraining.

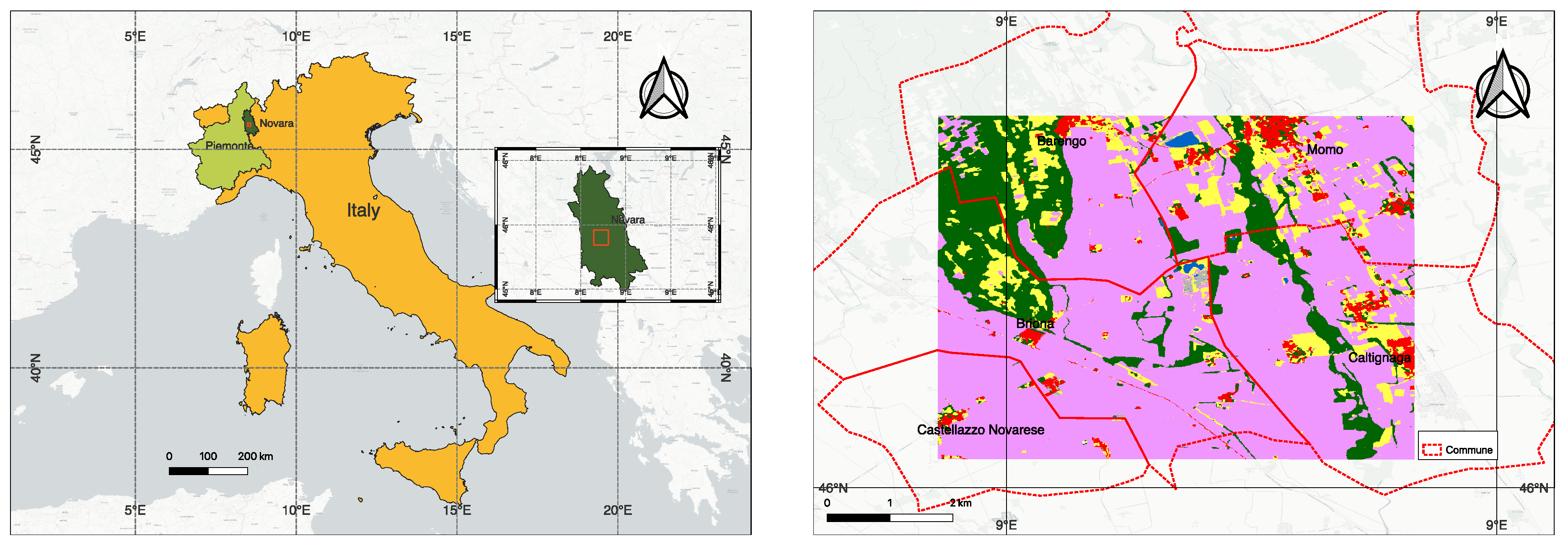

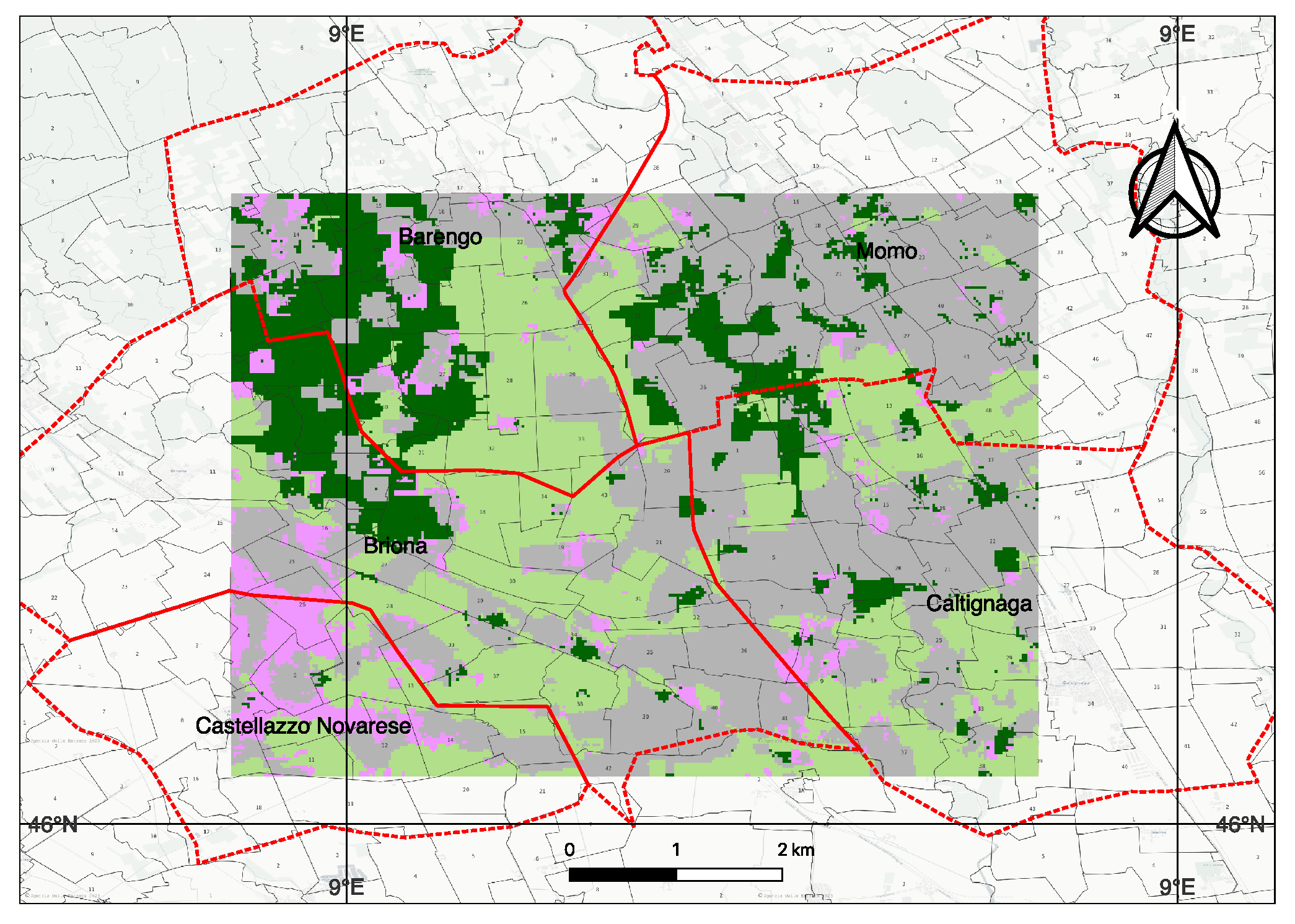

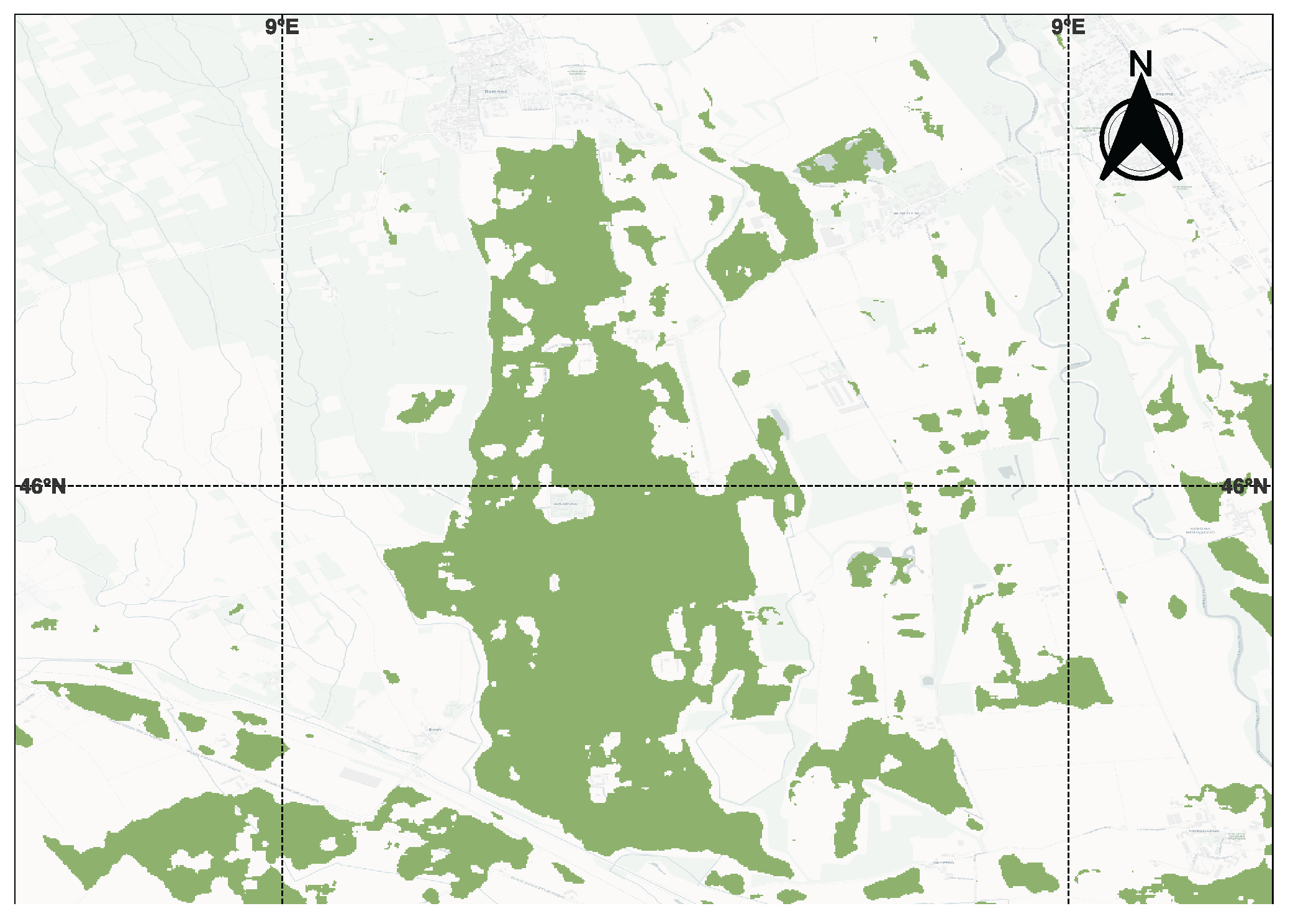

- Extension to real-world agricultural settings (e.g. ASI PRISMA imagery over Italy), showcasing transferability to unseen crops and regions with minimal supervision.

- Comparative performance approaching state-of-the-art transformer-based models (e.g. MASSFormer with training samples and ours with training samples in Salinas) in terms of accuracy, while requiring fewer parameters.

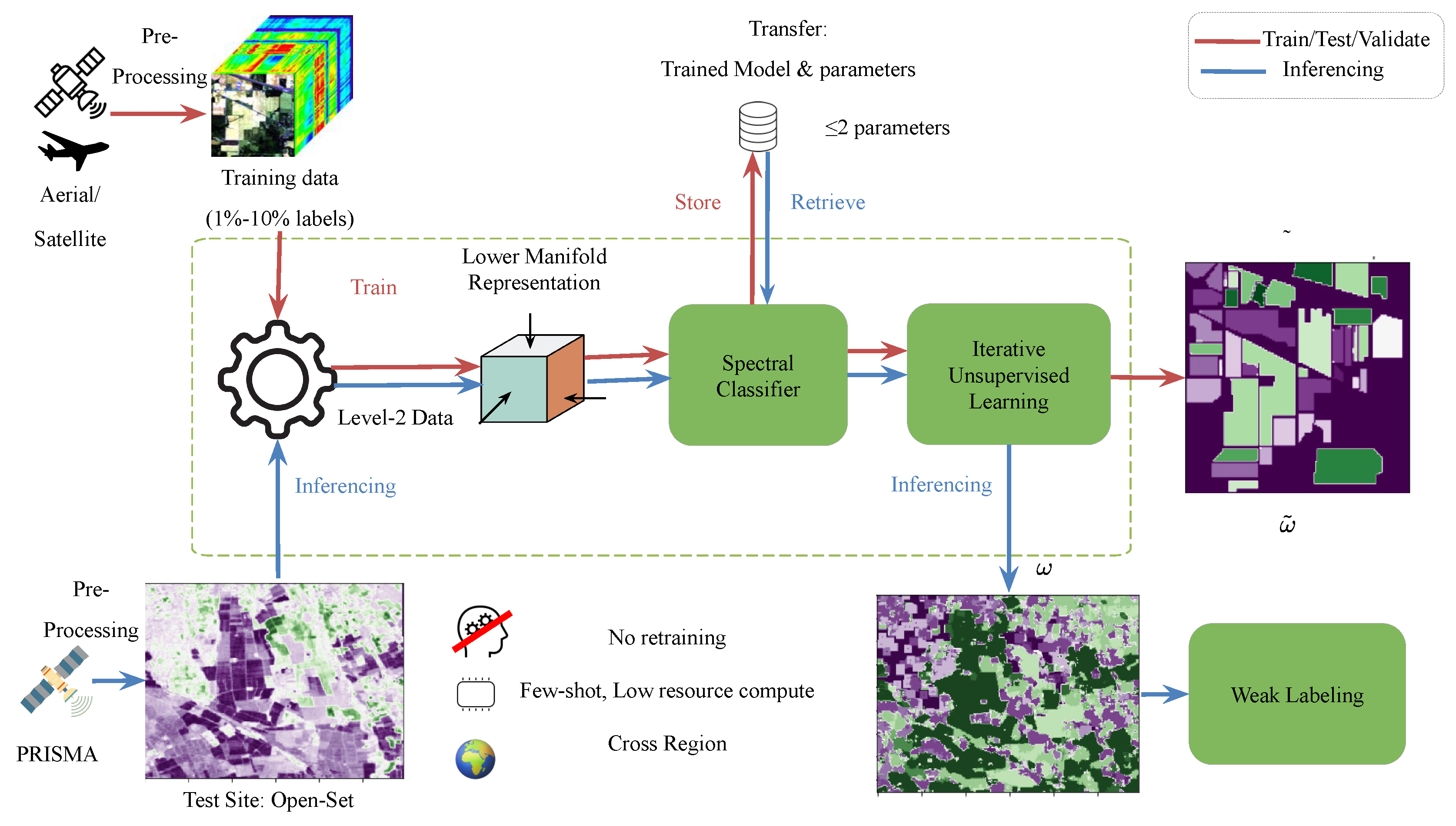

2. Learning Approach

- Map the analysis-ready data to a lower dimension representation in the space , reducing along the spectral features (either linearly or non-linearly)

- Supervised pixel-wise classification on K classes on the new representation,

- Construct the class probability map based on the pixel-wise classifier and use it as initial seed

- Iterative unsupervised learning using weighted trade-off between spatial nearness and spectral similarity measures,

- An optional ensembling of the different models from random batch of training samples and majority voting can improve reliability,

- Final assignment of the class using weak labeling.

2.1. Class Separability

2.2. Construction of Initial Classification Probability Map

2.3. The Model

2.3.1. Spatial Nearness Kernel

2.3.2. Spectral Similarity Kernel

2.3.3. Boundary Condition Handling

- Symmetric Padding: The input image is padded to by reflecting the values of the pixels at the borders. This ensures that every pixel has a complete neighborhood and is better than truncation.

- Small Memory Overhead: For , padding increases only fractionally the memory footprint () and is negligible for modern hardware.

2.3.4. Attention as Generalized Weighting

2.3.5. Unsupervised Learning

- Spectral term (): Rewards assignments agree with spectrally similar neighbors’ SVM predictions.

- Spatial term (): Encourages spatially coherent labeling while penalizing disagreement with nearby pixels.

- Trade-off parameter (): Controls relative importance. Low trusts the spectral evidence; high enforces spatial smoothness.

2.4. Ensemble Voting

- Step 1: The features are divided into 4 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive subsets using random sampling.

- Step 2: The proposed model is built on all the subsets individually and the classification map is obtained for every single model.

- Step 3: The classification maps from Step 2 are stacked and the final classification map is obtained by voting for the majority class.

3. Evaluation

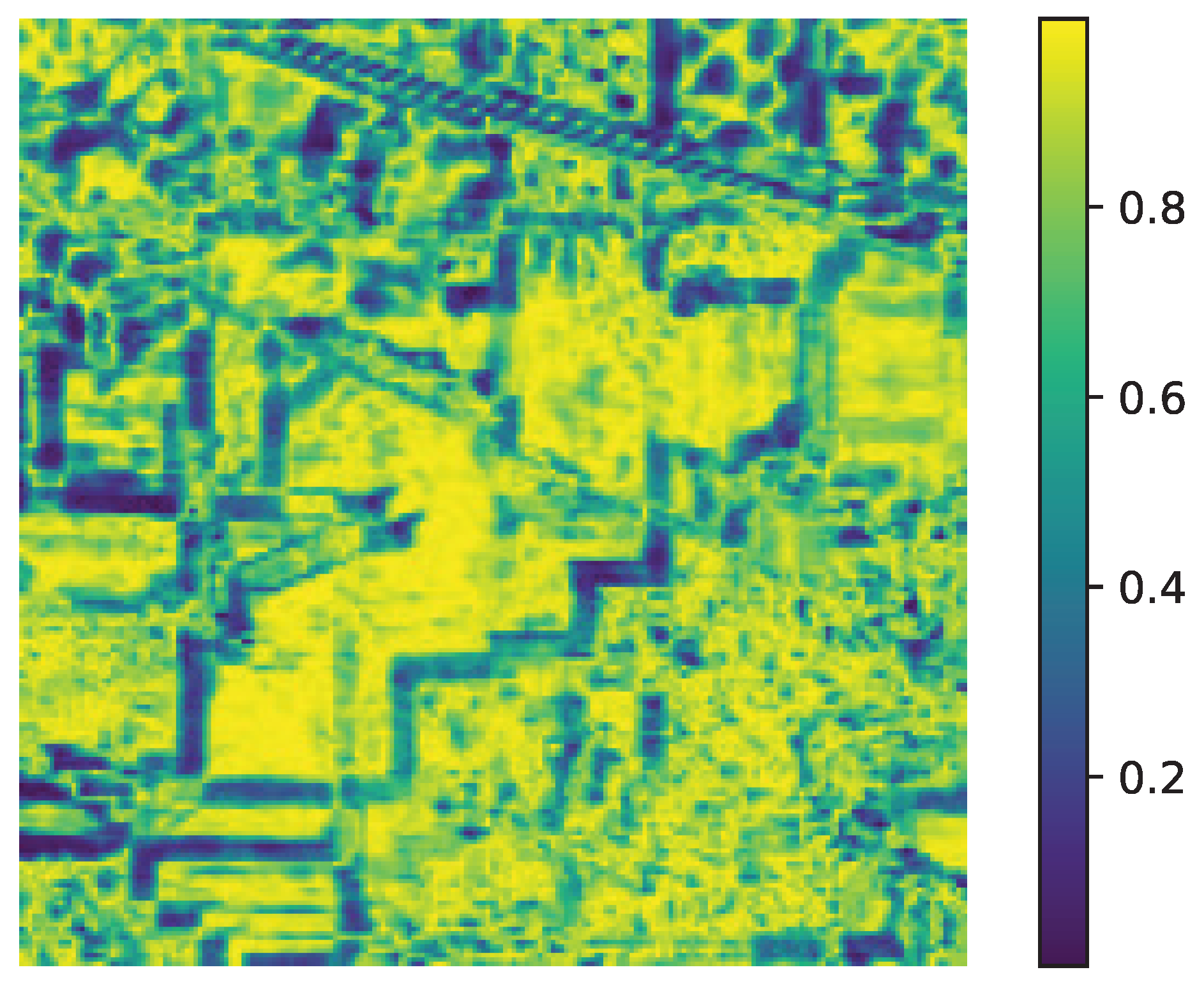

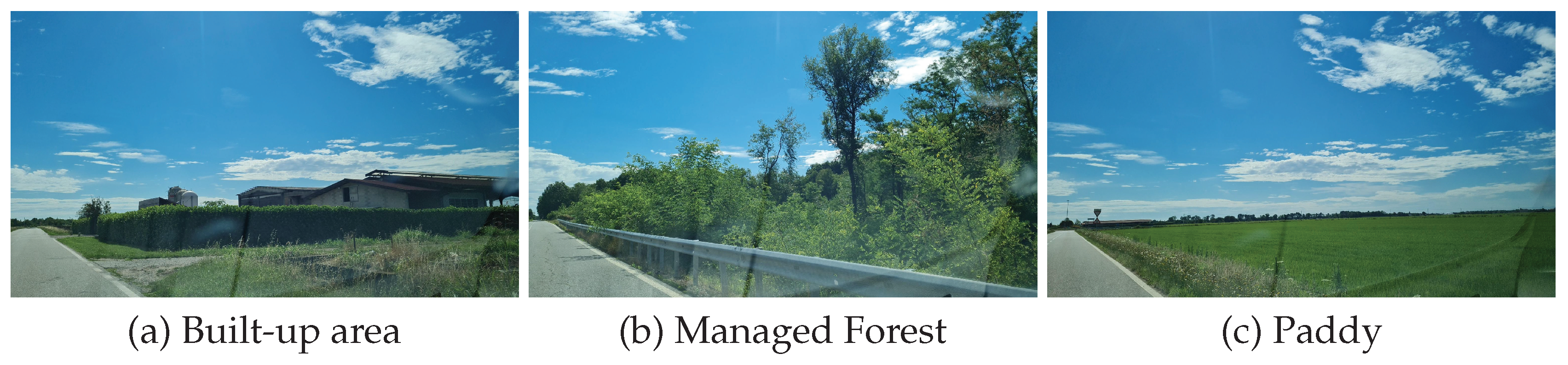

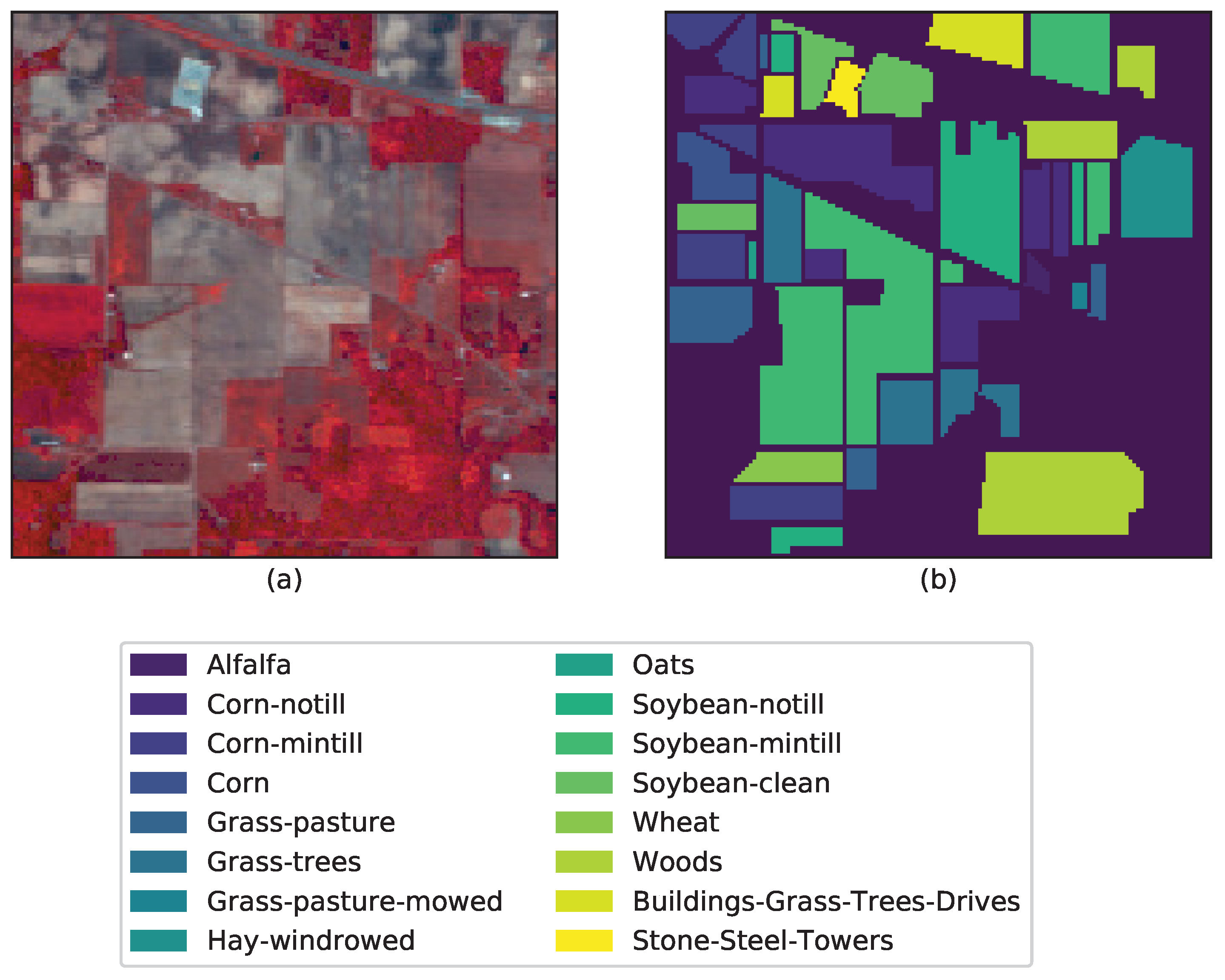

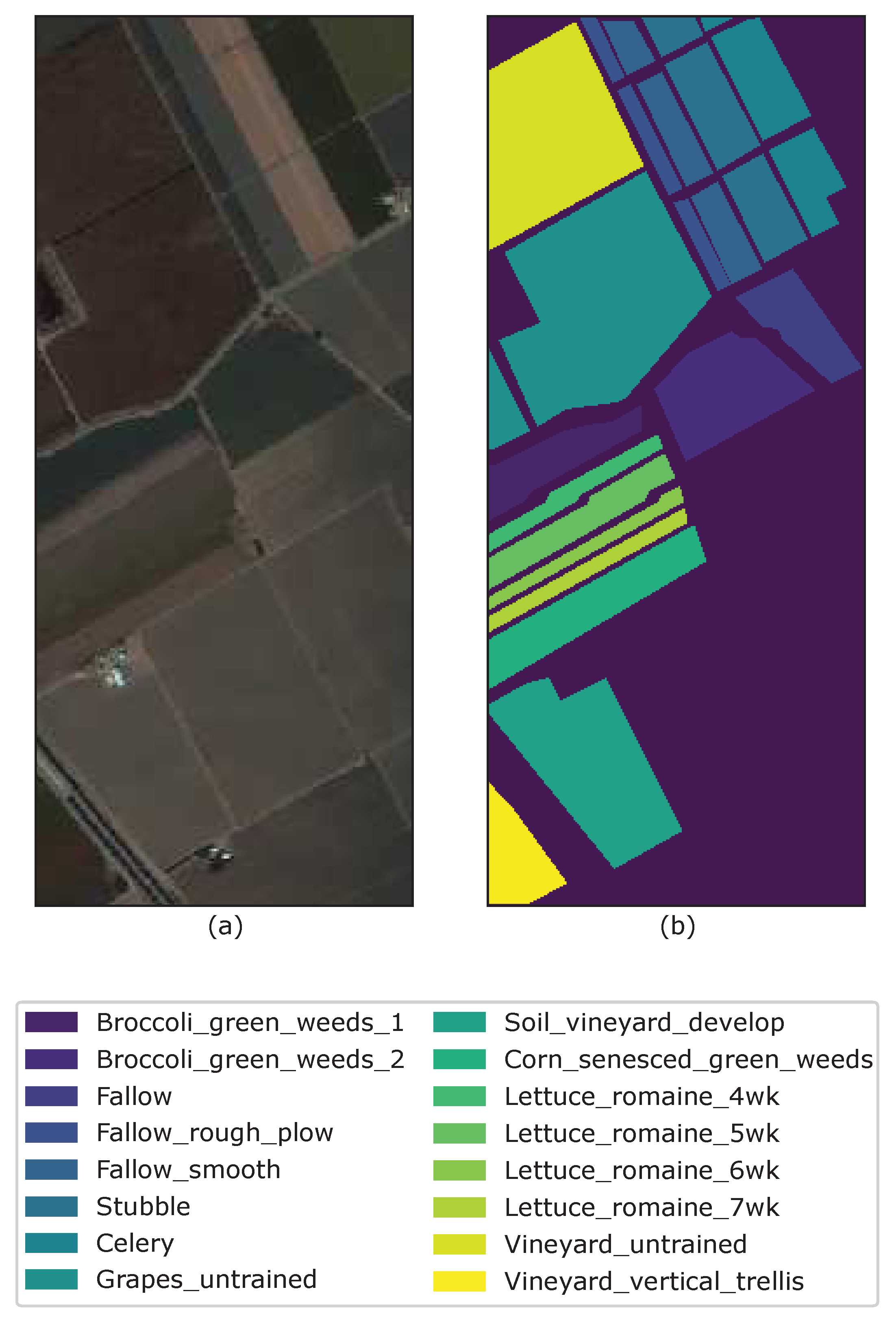

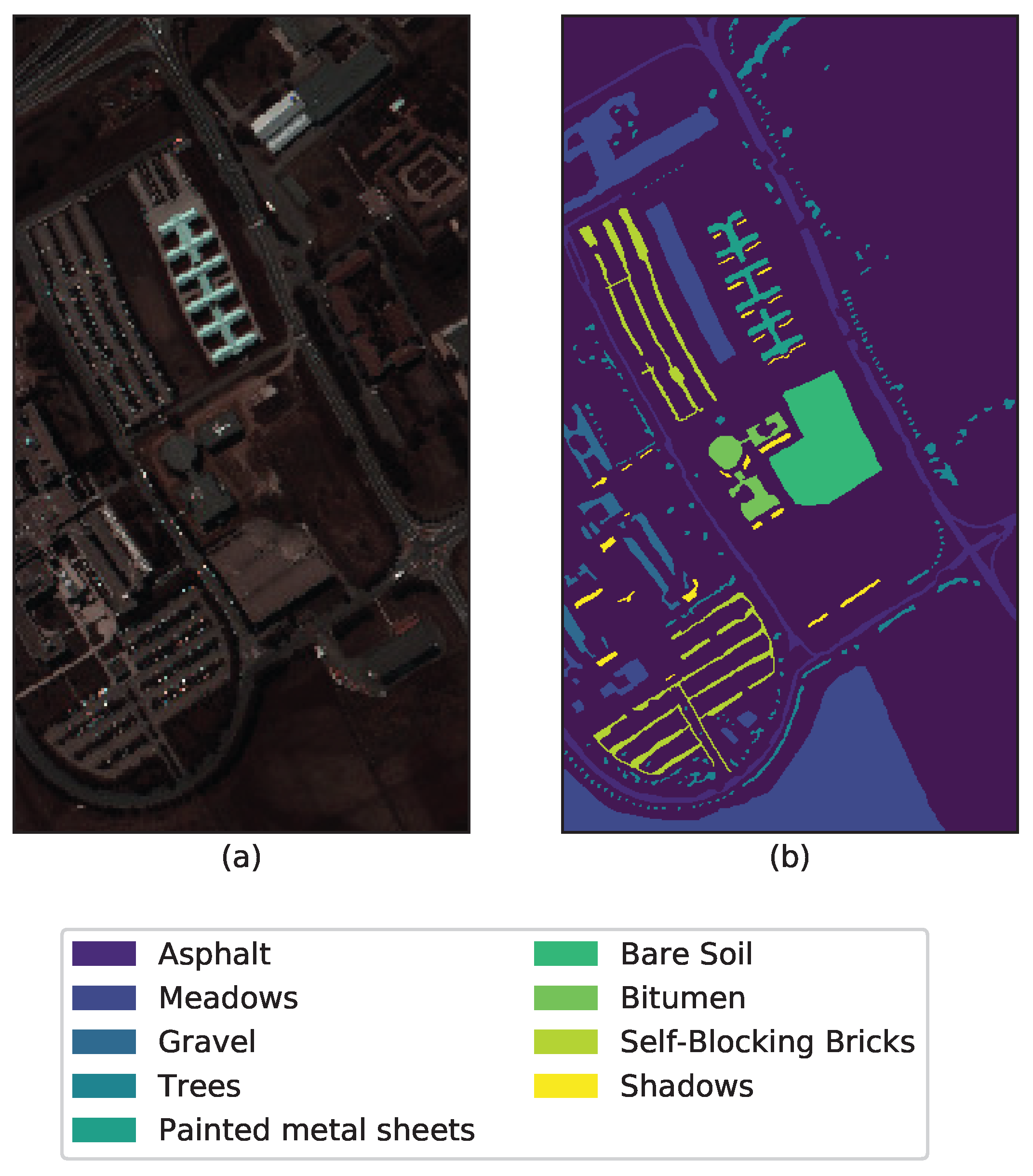

3.1. Benchmark Data for Training and Testing, and Open-Set Data for Inference

3.2. Performance Metrics

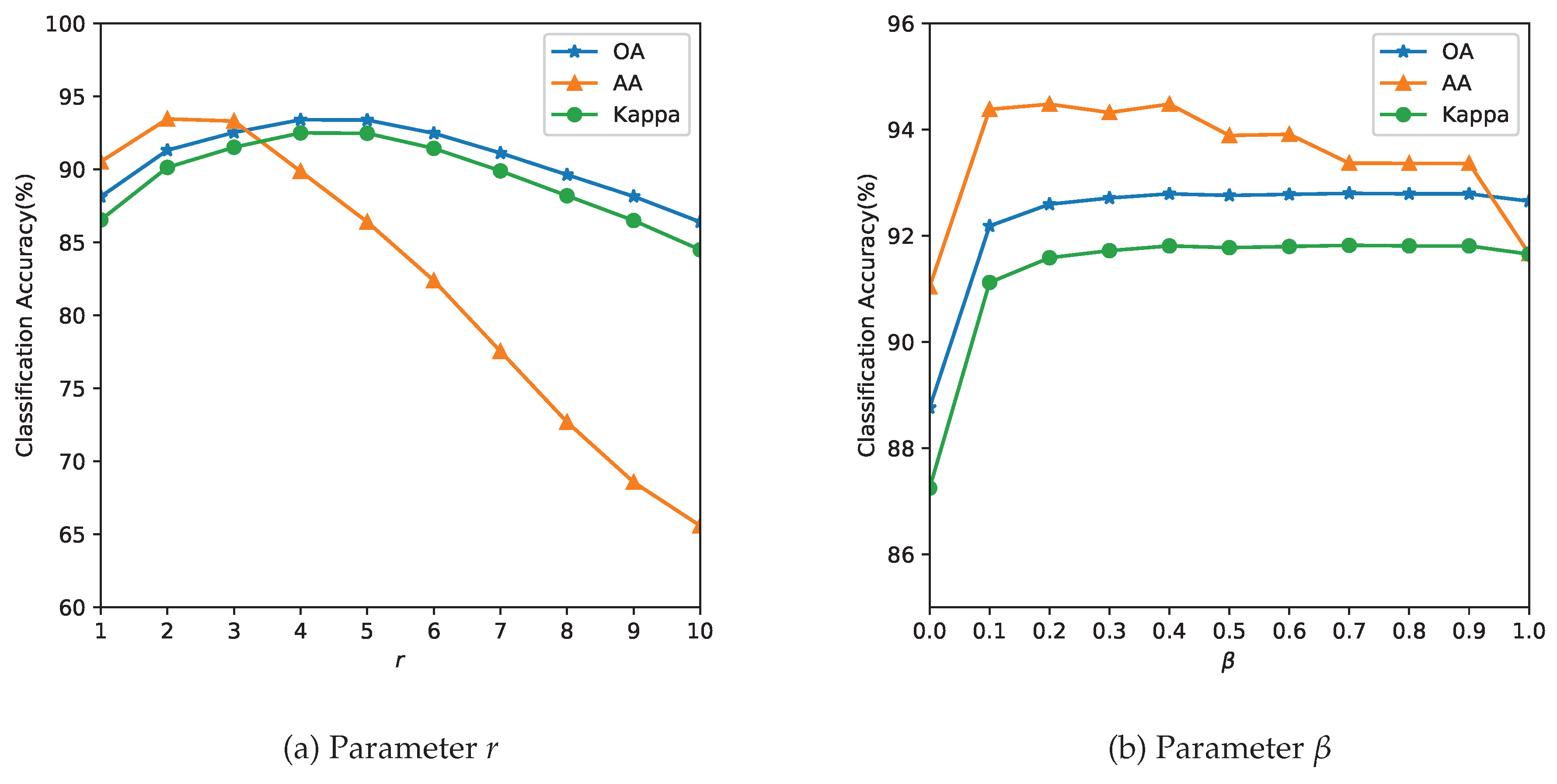

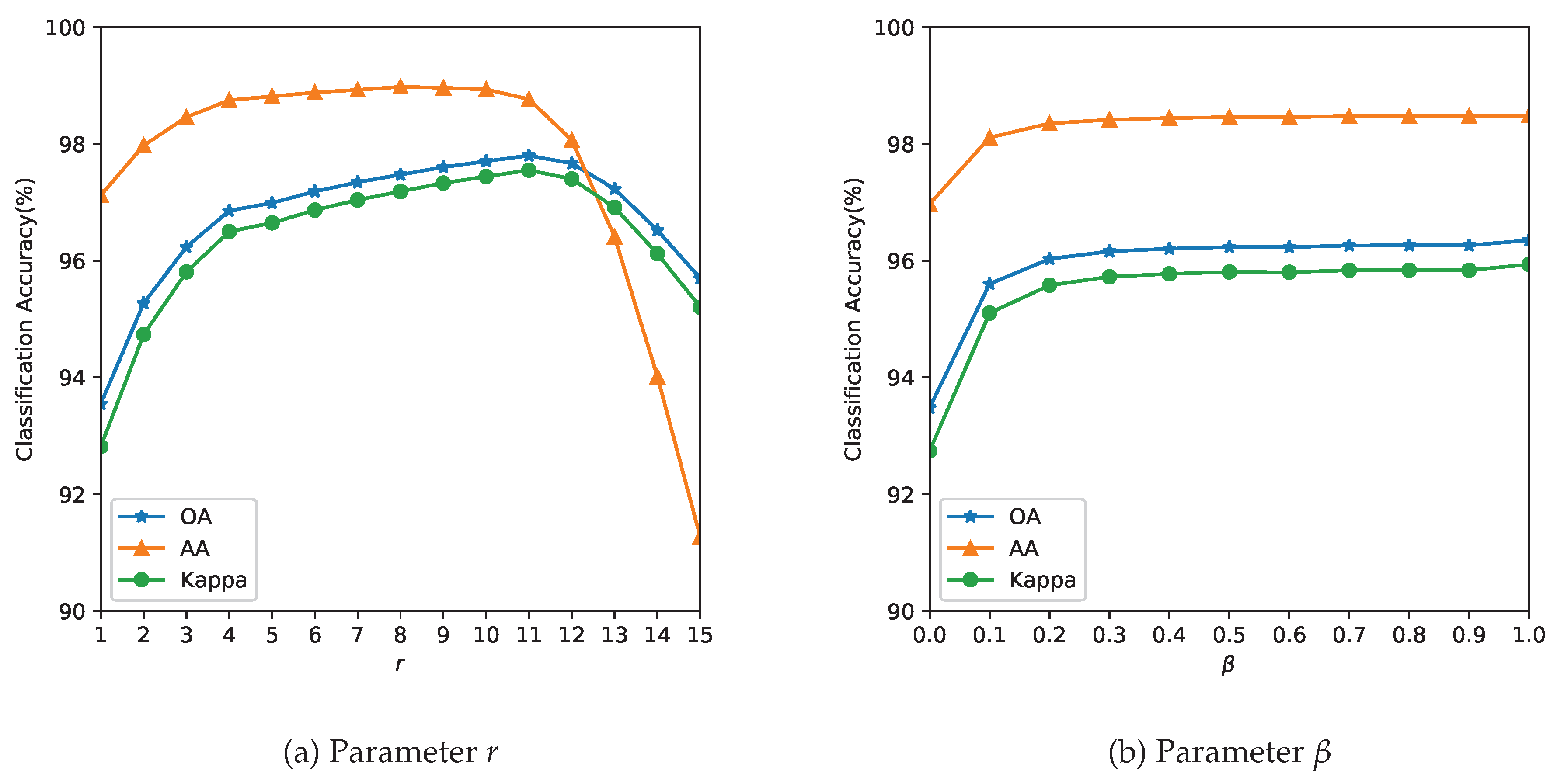

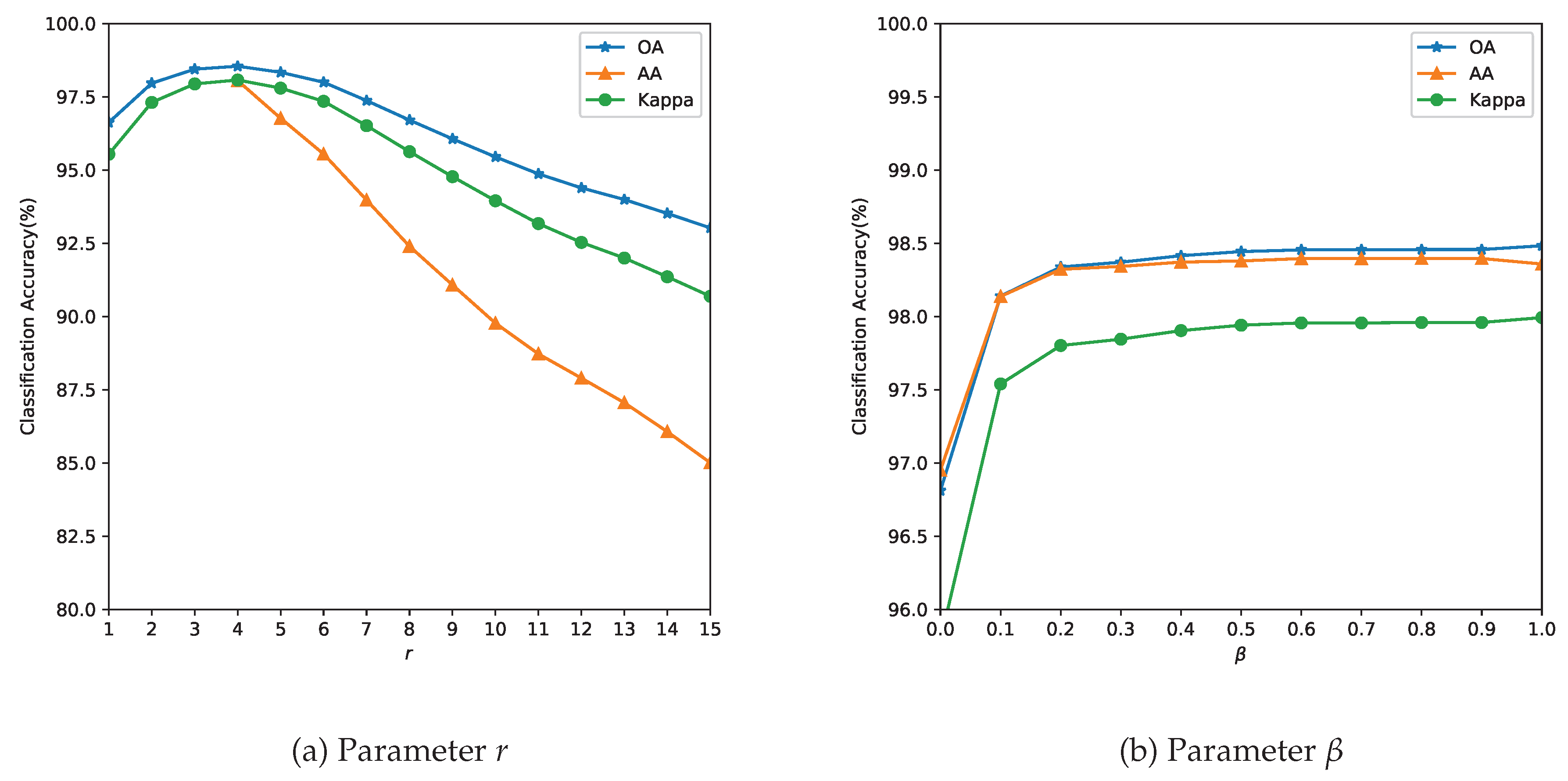

3.3. Analysis of Parameters

- Parameter Selection for PCA: We fixed the PCA parameters, viz. the explained ratio, to for all images, and the optimal number of principal components can be automatically calculated from that threshold. The cumulative explained variance ratio curves reached saturation after the first 30 main principal components. However, cross-validation (CV) did not show gains in the accuracies beyond the first 18 principal components.

- Spectral classifier parameter tuning: We used SVM [33] with the RBF kernel as a spectral classifier due to its relatively higher accuracy compared to other classifiers. We observed that spatial adjacency is maintained better by SVM’s pixel-level class label assignment than by using tree-based classifiers. As the number of parameters of the SVM (C and ) is small, these are estimated using an exhaustive grid search algorithm [41,42] within a specified coarse bound using a 5-fold CV. Finer grid search for the parameter is computationally feasible and can be parallelized [41] but at the risk of overfitting to the data.

-

When training, we randomly choose a few pixels from each class label. For training data partition, we deliberately used smaller training fractions than conventional literature splits. This choice simulates real-world data-scarce agricultural conditions and reflects our operational experience. The ground truth collection requires expensive field campaigns with multiple seasonal visits. The minor crops often have minimal representation in the training data, and climate variability causes crop rotation between seasons, necessitating re-labeling. Some authors have estimated that their algorithm gave the best OA when of data was used for training for the Indian Pines, for the Salinas and for the Pavia respectively [43]. In real-world scenarios, ground truth is sparse and expensive. We used smaller training fractions than conventional splits for these benchmark datasets to highlight low-label scenarios. Thus, to reduce efforts in manual ground truth data collection and annotation, our objective towards model building was to use as few training samples as possible or low-resource conditions. Our objective is to demonstrate that the proposed method maintains competitive accuracy even under extreme label scarcity (), whereas deep models typically require much higher data for stable training.Table 1. Training data partition comparison between our study and literature.

Dataset Literature Our Study Rationale Indian Pines Maintained for comparison Salinas 4–10% Sparse-label stress test Pavia Univ Extreme low-resource scenario - Parameter tuning: The parameter r determines the size of the neighborhood around the reference pixel, the parameters and control the degree of spatial nearness and spectral similarity Gaussian kernel, respectively. The parameter , with , specifies the relative importance between the two terms in Equation (11). Because spatial and spectral kernels operate within a radial neighborhood of r, we restrict and to values proportional to r. This is also expected behavior, as the value of the parameter r is linked to spatial resolution. In missions with lower resolution acquisitions, to avoid smoothing, a lower value of r is required. The spatial resolution and the choice of the neighborhood are also closely linked to the type of farm holding size. It is likely that for smaller landholding sizes ( acres or 6400 or Ha), the performance of the method could be affected. The performance of the model is evaluated with respect to the three quality indexes mentioned in Section 3.2 and the results are summarized in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

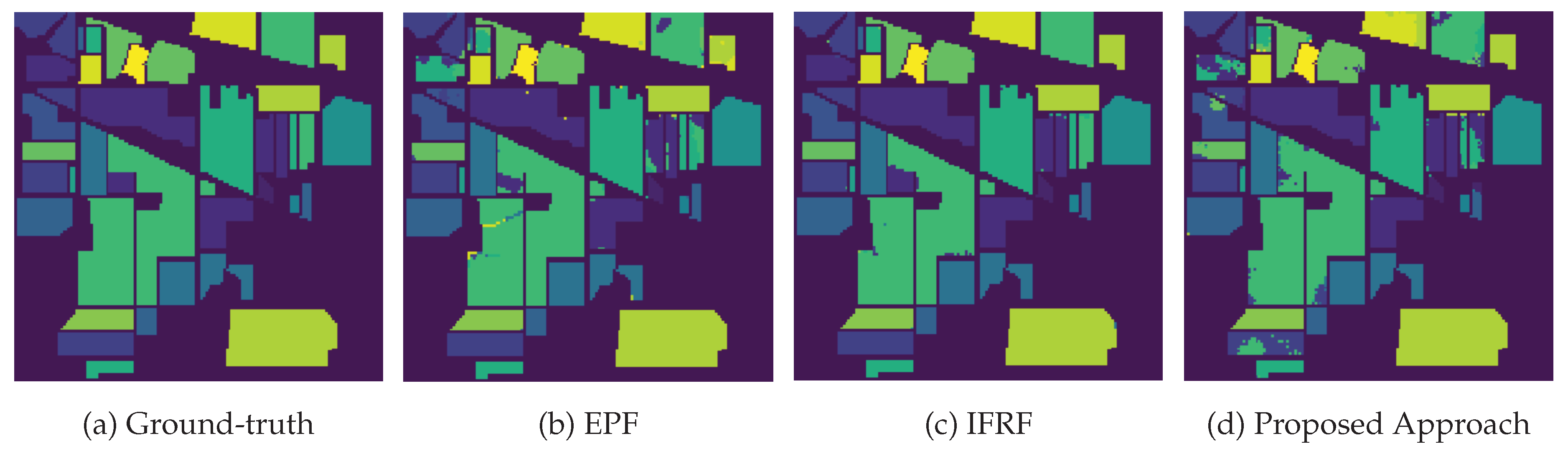

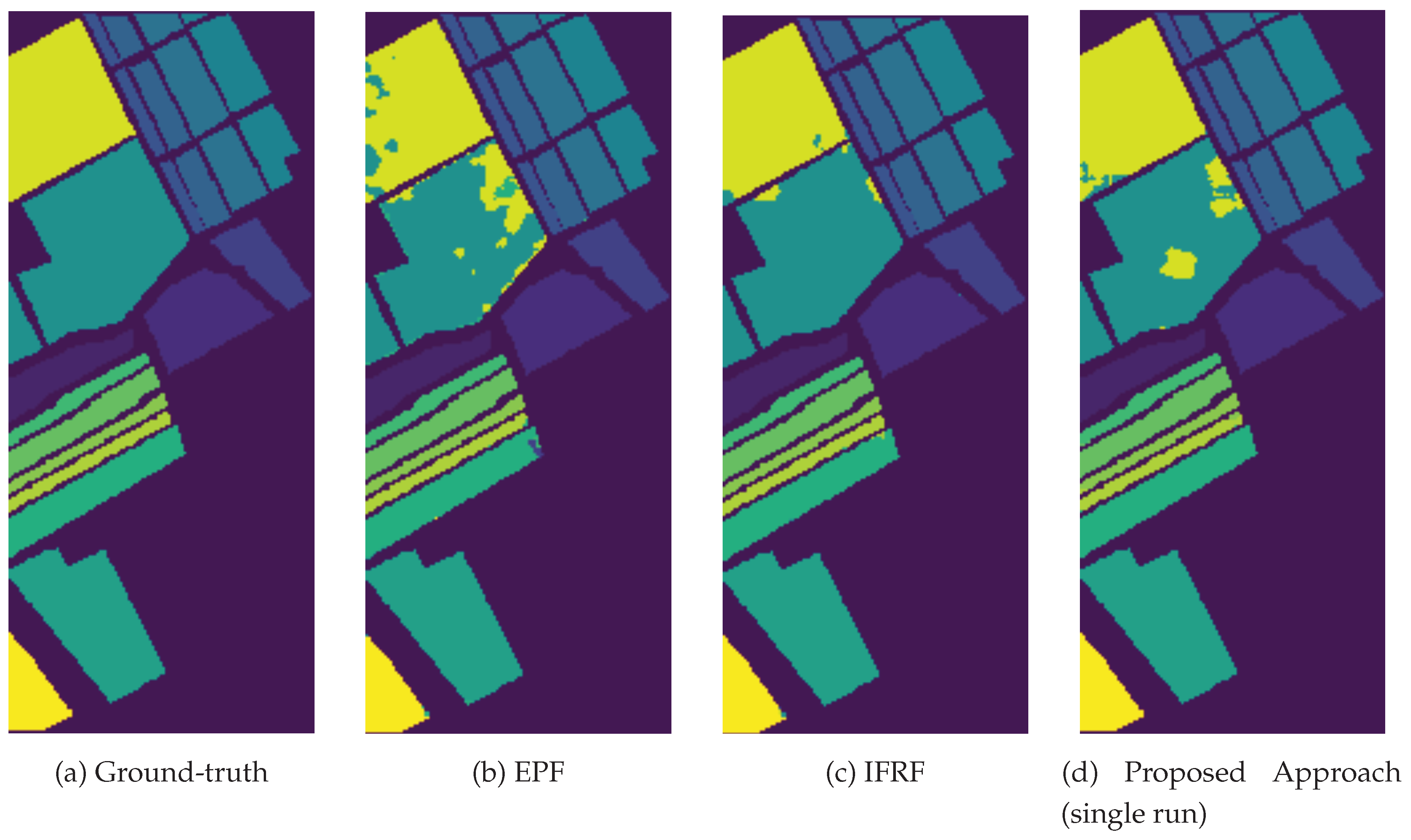

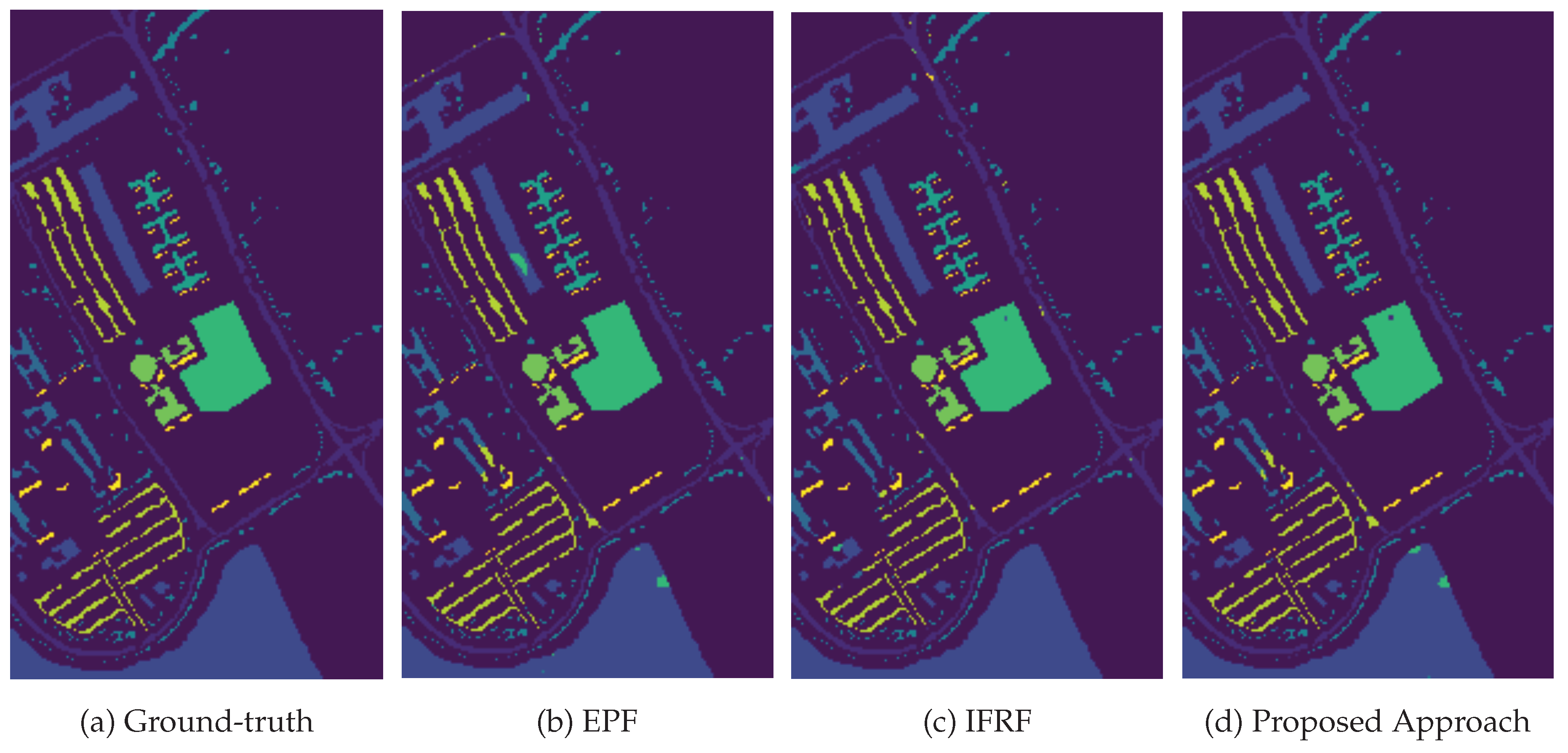

3.4. Classification Results and Model Transferability

3.5. Ablation Studies

- a pixel-wise classifier based on SVM,

- the SVM classifier followed by CRF-based regularization, and

- the full pipeline integrating model transfer, iterative unsupervised learning with refinement and weak labeling.

- Purely pixel-wise classification is insufficient for open-set agricultural scenarios due to high within-class variability and due to minimal/no class overlap with training data.

- Adding spatial regularization using CRF improves the homogeneity of the predictions, but can also decrease the performance if the initial labeling is wrong. Regularization cannot handle unknown classes.

- The full model makes use of both spatial proximity and spectral similarity. So, even if the initial mapping is mislabeled, iteratively it is refined. It is also effective in handling unseen or under-represented classes, demonstrating robustness to domain transfer with limited training labels.

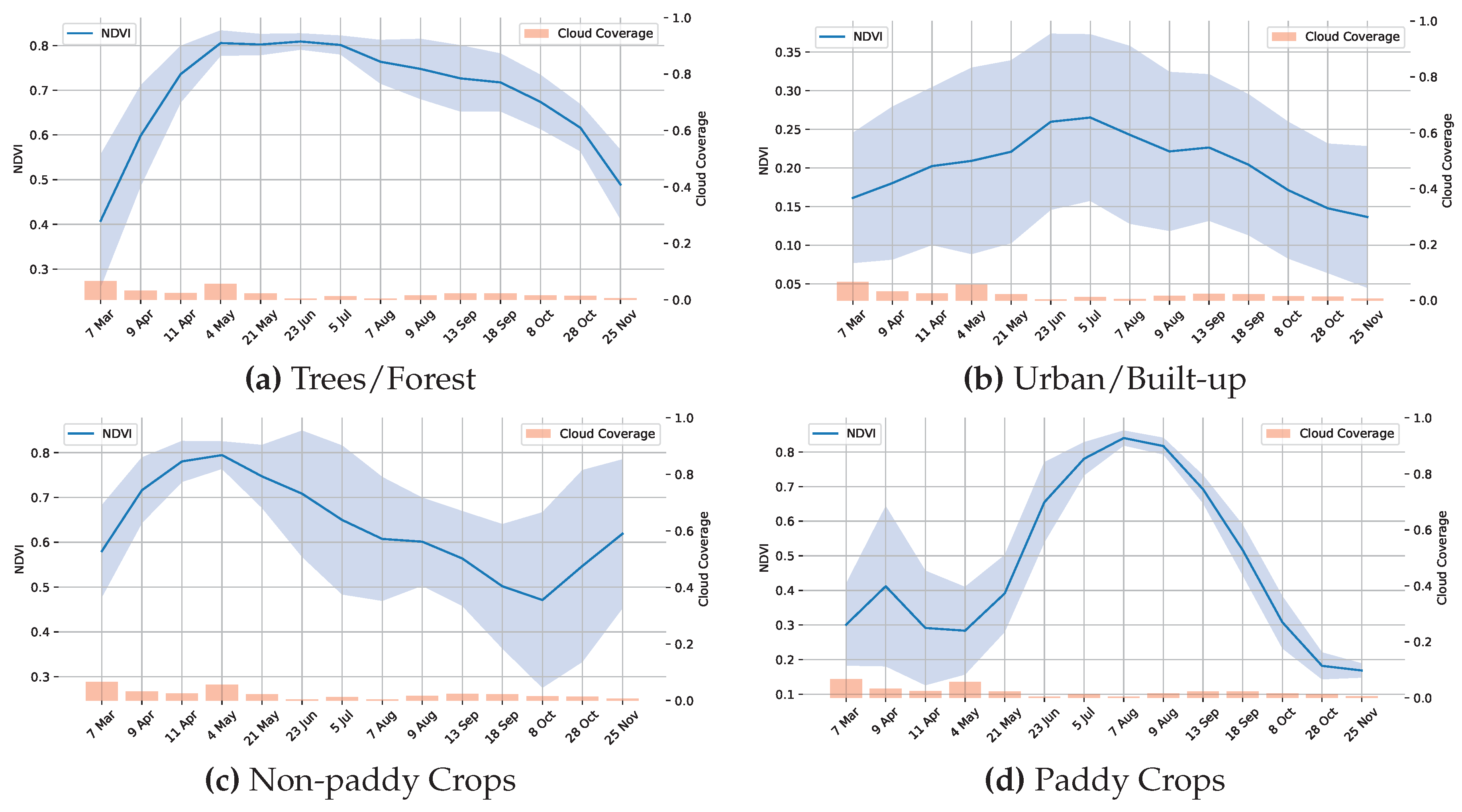

3.6. Testing on New Region and Crop-Zero Shot Conditions

3.7. Limitations

- Spectral Confusion: The model confuses between spectrally similar crops or the same crop with different management practices, and is typical of single temporal snapshot-based analysis. Multi-temporal analysis might resolve this confusion.

- Phenology Sensitivity: The model is sensitive to the phenological stage, and the accuracy is highest during the maturity stage of the crop,

- Validation Constraints: The absence of field campaigns for the PRISMA dataset means that the methodology uses proxy validation through multi-sensor cross-checking rather than actual field campaign data. While we observed that the inter-method agreement was high, having ground-truth field campaigns could also give accuracy statistics.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Notations and Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| AA | Average Accuracy |

| AVIRIS | Airborne Visible/Infrared |

| Imaging Spectrometer | |

| HSI | Hyperspectral Image |

| CNN | Convolution Neural Network |

| CV | Cross Validation |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| EPF | Edge Preserving Filter |

| GHG | Green House Gas |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HCO | Co-registered Hypercube |

| ICM | Iterative Conditional Model |

| IFRF | Image Fusion and Recursive Filtering |

| kNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| KPCA | Kernel PCA |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NIR | Near Infrared |

| OA | Overall Accuracy |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PRISMA | Hyperspectral Precursor of the Application Mission |

| RGB | Red-Green-Blue |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| RMG | Random Multi-graph |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SWIR | Short-Wave Infrared |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| VNIR | Visible and Near-Infrared |

References

- Weiss, M.; Jacob, F.; Duveiller, G. Remote sensing for agricultural applications: A meta-review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adão, T.; Hruška, J.; Pádua, L.; Bessa, J.; Peres, E.; Morais, R.; Sousa, J. Hyperspectral Imaging: A Review on UAV-Based Sensors, Data Processing and Applications for Agriculture and Forestry. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Cerro, J.; Cruz Ulloa, C.; Barrientos, A.; de León Rivas, J. Unmanned aerial vehicles in agriculture: A survey. Agronomy 2021, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, C.R.; Serbina, L.O.; Miller, H.M. Landsat and agriculture—Case studies on the uses and benefits of Landsat imagery in agricultural monitoring and production. Technical report, US Geological Survey, 2017.

- Lu, B.; Dao, P.D.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Shang, J. Recent advances of hyperspectral imaging technology and applications in agriculture. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar]

- Thenkabail, P.S.; Smith, R.B.; Pauw, E.D. Hyperspectral Vegetation Indices and Their Relationships with Agricultural Crop Characteristics. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 71, 158–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apan, A.; Held, A.; Phinn, S.; Markley, J. Detecting sugarcane ‘orange rust’ disease using EO-1 Hyperion hyperspectral imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, P.; Tansey, K.; Balzter, H.; Boyd, D.S. Detecting the effects of hydrocarbon pollution in the Amazon forest using hyperspectral satellite images. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 205, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Verrelst, J.; Féret, J.B.; Wang, Z.; Wocher, M.; Strathmann, M.; Danner, M.; Mauser, W.; Hank, T. Crop nitrogen monitoring: Recent progress and principal developments in the context of imaging spectroscopy missions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 242, 111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persello, C.; Wegner, J.D.; Hänsch, R.; Tuia, D.; Ghamisi, P.; Koeva, M.; Camps-Valls, G. Deep learning and earth observation to support the sustainable development goals: Current approaches, open challenges, and future opportunities. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 172–200. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.J.; Khan, H.S.; Yousaf, A.; Khurshid, K.; Abbas, A. Modern Trends in Hyperspectral Image Analysis: A Review. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 14118–14129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signoroni, A.; Savardi, M.; Baronio, A.; Benini, S. Deep Learning Meets Hyperspectral Image Analysis: A Multidisciplinary Review. J. Imaging 2019, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audebert, N.; Le Saux, B.; Lefevre, S. Deep Learning for Classification of Hyperspectral Data: A Comparative Review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2019, 7, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jia, X. Spectral–Spatial Classification of Hyperspectral Data Based on Deep Belief Network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Li, J.; Luo, Z.; Chapman, M. Spectral–Spatial Residual Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification: A 3-D Deep Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, H. MASSFormer: Memory-Augmented Spectral-Spatial Transformer for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidici, D.; Clark, M. One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network Land-Cover Classification of Multi-Seasonal Hyperspectral Imagery in the San Francisco Bay Area, California. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, S.; Binder, A.; Montavon, G.; Klauschen, F.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. On Pixel-Wise Explanations for Non-Linear Classifier Decisions by Layer-Wise Relevance Propagation. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0130140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montavon, G.; Lapuschkin, S.; Binder, A.; Samek, W.; Müller, K.R. Explaining nonlinear classification decisions with deep Taylor decomposition. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 65, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Bahrudeen, A.; Rahim, A. Spectral Fidelity and Spatial Enhancement: An Assessment and Cascading of Pan-Sharpening Techniques for Satellite Imagery. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.18900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alparone, L.; Arienzo, A.; Garzelli, A. Spatial Resolution Enhancement of Satellite Hyperspectral Data via Nested Hypersharpening With Sentinel-2 Multispectral Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 10956–10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wu, J.; Biao, W.; Liao, Y.; Gu, D. SpectralMAE: Spectral Masked Autoencoder for Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Image Reconstruction. Sensors 2023, 23, 3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Yan, Q.; Zhao, F.; Liang, M. Hyperspectral Image Classification with Dynamic Spatial-Spectral Attention Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 13th Workshop on Hyperspectral Imaging and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing (WHISPERS), Athens, Greece, 31 October–2 November 2023; 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Z. Hyperspectral Image Classification Using Spectral–Spatial Double-Branch Attention Mechanism. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Distefano, S.; Khan, A.M.; Mazzara, M.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Aryal, J.; Ding, Y.; Vivone, G.; Hong, D. A comprehensive survey for Hyperspectral Image Classification: The evolution from conventional to transformers and Mamba models. Neurocomputing 2025, 644, 130428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Song, M.; Gong, K.; Peng, Y.; Hou, J.; Jiang, T. Hyperspectral open set classification with unknown classes rejection towards deep networks. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 6355–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Fang, L.; He, M. Spectral-spatial latent reconstruction for open-set hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 5227–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, A. PCA, Kernel PCA and Dimensionality Reduction in Hyperspectral Images. In Advances in Principal Component Analysis: Research and Development; Naik, G.R., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Esbensen, K.; Geladi, P. Principal component analysis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 1987, 2, 37–52, Proceedings of the Multivariate StatisticalWorkshop for Geologists and Geochemists. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardi, G.; Marpu, P.R.; Chanussot, J.; Benediktsson, J.A. Linear Versus Nonlinear PCA for the Classification of Hyperspectral Data Based on the Extended Morphological Profiles. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2012, 9, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Krishna, G.; Dubey, S.R.; Chaudhuri, B. HybridSN: Exploring 3-D-2-D CNN Feature Hierarchy for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 17, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, L.; Frieauff, D.; Puzicha, J.; Buhmann, J.M. Support vector machines for land usage classification in Landsat TM imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE 1999 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. IGARSS’99 (Cat. No.99CH36293), Hamburg, Germany, 28 June–2 July 1999; Volume 1, pp. 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgani, F.; Bruzzone, L. Classification of hyperspectral remote sensing images with support vector machines. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2004, 42, 1778–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Shi, J.; Li, Q.; He, B.; Chen, J. ThunderSVM: A Fast SVM Library on GPUs and CPUs. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2018, 19, 797–801. [Google Scholar]

- Shotton, J.; Winn, J.M.; Rother, C.; Criminisi, A. TextonBoost for Image Understanding: Multi-Class Object Recognition and Segmentation by Jointly Modeling Texture, Layout, and Context. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2009, 81, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krähenbühl, P.; Koltun, V. Efficient Inference in Fully Connected CRFs with Gaussian Edge Potentials. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2011, 24, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Li, M. MRF and CRF Based Image Denoising and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 5th International Conference on Digital Home, Guangzhou, China, 28–30 November 2014; pp. 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemker, R.; Salvaggio, C.; Kanan, C. Algorithms for semantic segmentation of multispectral remote sensing imagery using deep learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 145, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Hyperspectral Dataset, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Baumgardner, M.F.; Biehl, L.L.; Landgrebe, D.A. 220 Band AVIRIS Hyperspectral Image Data Set: June 12, 1992 Indian Pine Test Site 3, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.W.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, C.J. A Practical Guide to Support Vector Classification. Technical report, National Taiwan University, 2003.

- Ben-Hur, A.; Weston, J. A user’s guide to support vector machines. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 609, 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, X.; Li, S.; Benediktsson, J.A. Feature Extraction of Hyperspectral Images With Image Fusion and Recursive Filtering. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 3742–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapelle, O.; Vapnik, V.; Bousquet, O.; Mukherjee, S. Choosing Multiple Parameters for Support Vector Machines. Mach. Learn. 2002, 46, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Li, S.; Benediktsson, J.A. Spectral-Spatial Hyperspectral Image Classification With Edge-Preserving Filtering. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 2666–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Wang, Q.; Dong, J.; Xu, Q. Spectral and Spatial Classification of Hyperspectral Images Based on Random Multi-Graphs. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Di, L.; Zhang, C.; Guo, L. Transfer Learning for Crop classification with Cropland Data Layer data (CDL) as training samples. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 733, 138869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, F. An unsupervised domain adaptation deep learning method for spatial and temporal transferable crop type mapping using Sentinel-2 imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 199, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Zhu, X.; Huang, S.; Linquist, B.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wassmann, R.; Minamikawa, K.; Martinez-Eixarch, M.; Yan, X.; Zhou, F.; et al. Greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation in rice agriculture. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, L.; Formaro, R.; Guarini, R.; Loizzo, R.; Longo, F.; Varacalli, G. The PRISMA mission. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Beijing, China, 10–15 July 2016; pp. 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaga, D.; Van De Kerchove, R.; De Keersmaecker, W.; Souverijns, N.; Brockmann, C.; Quast, R.; Wevers, J.; Grosu, A.; Paccini, A.; Vergnaud, S.; et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2020 v100, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Büttner, G. CORINE Land Cover and Land Cover Change Products. In Land Use and Land Cover Mapping in Europe: Practices & Trends; Manakos, I., Braun, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, M.; Dong, J.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, X. High resolution paddy rice maps in cloud-prone Bangladesh and Northeast India using Sentinel-1 data. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Khan, A.M.; Mazzara, M.; Distefano, S.; Ali, M.; Sarfraz, M.S. A Fast and Compact 3-D CNN for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data/Parameters | C | r | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indian Pines | 35 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Salinas | 43 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 1 | |

| Pavia University | 34 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Optimal Parameter | Dataset specific | 7 | 4 |

| Class | Train | Test | SVM | EPF [45] | IFRF [43] | RMG [46] | Proposed (single run) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfalfa | 20 | 26 | 93.48 | 97.83 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 97.83 |

| Corn-notill | 143 | 1285 | 77.31 | 84.45 | 99.44 | 95.33 | 88.17 |

| Corn-mintill | 83 | 747 | 73.61 | 91.454 | 99.76 | 98.20 | 91.08 |

| Corn | 24 | 213 | 54.85 | 100.00 | 99.58 | 97.86 | 91.14 |

| Grass-pasture | 48 | 435 | 89.71 | 97.10 | 100.00 | 95.17 | 92.96 |

| Grass-trees | 73 | 657 | 96.57 | 99.73 | 100.00 | 98.80 | 100.00 |

| Grass-pasture-mowed | 14 | 14 | 96.43 | 96.43 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Hay-windrowed | 48 | 430 | 94.98 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Oats | 10 | 10 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 95.00 |

| Soybean-notill | 97 | 875 | 79.22 | 98.35 | 94.69 | 98.24 | 94.03 |

| Soybean-mintill | 217 | 2238 | 70.06 | 93.24 | 98.37 | 98.58 | 88.64 |

| Soybean-clean | 59 | 534 | 65.77 | 97.98 | 99.66 | 98.53 | 95.28 |

| Wheat | 21 | 184 | 98.54 | 99.51 | 99.51 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Woods | 119 | 1146 | 96.52 | 97.94 | 99.76 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Building-grass-trees-drives | 39 | 347 | 57.25 | 98.96 | 99.74 | 99.74 | 81.09 |

| Stone-steel-towers | 9 | 84 | 79.57 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 98.95 | 97.85 |

| OA (%) | 79.30 | 94.77 | 99.40 | 98.23 | 92.78 | ||

| AA (%) | 82.80 | 97.06 | 99.72 | 98.71 | 94.57 | ||

| Kappa | 76.50 | 94.06 | 99.32 | 97.99 | 91.78 | ||

| Class | Train | Test | SVM | EPF [45] | IFRF [43] | RMG [46] | Proposed (single run) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broccoli-green-weeds-1 | 67 | 1942 | 99.75 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Broccoli-green-weeds-2 | 67 | 3659 | 99.62 | 100.00 | 99.95 | 99.87 | 100.00 |

| Fallow | 67 | 1909 | 96.91 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.34 | 100.00 |

| Fallow-rough-plow | 69 | 1325 | 99.71 | 99.93 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 98.85 |

| Fallow-smooth | 67 | 2611 | 96.23 | 99.29 | 99.40 | 98.62 | 99.63 |

| Stubble | 67 | 3892 | 99.82 | 100.00 | 99.82 | 99.77 | 100.00 |

| Celery | 68 | 3511 | 99.72 | 99.92 | 99.83 | 99.66 | 99.86 |

| Grapes-untrained | 69 | 11102 | 63.72 | 84.74 | 98.16 | 98.70 | 91.78 |

| Soil-vineyard-develop | 68 | 6135 | 99.69 | 99.84 | 99.98 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Corn-senesced-green-weeds | 68 | 3210 | 91.31 | 96.55 | 99.15 | 98.84 | 99.97 |

| Lettuce-romaine-4wk | 68 | 1000 | 96.72 | 99.72 | 100.00 | 99.81 | 99.16 |

| Lettuce-romaine-5wk | 67 | 1860 | 99.69 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 98.44 | 100.00 |

| Lettuce-romaine-6wk | 67 | 849 | 98.47 | 99.13 | 99.67 | 99.34 | 98.80 |

| Lettuce-romaine-7wk | 67 | 1003 | 94.86 | 98.60 | 99.81 | 99.16 | 97.01 |

| Vineyard-untrained | 70 | 7198 | 72.76 | 93.02 | 98.18 | 96.82 | 96.68 |

| Vineyard-vertical-trellis | 67 | 1740 | 98.67 | 99.23 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| OA(%) | 87.61 | 95.54 | 99.22 | 99.01 | 97.69 | ||

| AA(%) | 94.23 | 98.12 | 99.56 | 99.27 | 98.86 | ||

| Kappa | 86.25 | 95.05 | 99.13 | 98.89 | 97.43 | ||

| Class | Train | Test | SVM | EPF [45] | IFRF [43] | RMG [46] | Our Approach (single run) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asphalt | 20 | 26 | 88.36 | 97.19 | 97.21 | 99.76 | 97.48 |

| Meadows | 143 | 1285 | 93.43 | 98.46 | 99.49 | 99.95 | 98.6 |

| Gravel | 83 | 747 | 85.23 | 91.42 | 98.52 | 99.86 | 94.85 |

| Trees | 24 | 213 | 96.15 | 95.50 | 97.42 | 97.75 | 97.29 |

| Painted-metal-sheets | 48 | 435 | 99.55 | 100.00 | 99.63 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Bare-soil | 73 | 657 | 92.19 | 100.00 | 99.92 | 100.00 | 99.54 |

| Bitumen | 14 | 14 | 94.66 | 99.92 | 99.40 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Self-blocking-bricks | 48 | 430 | 88.27 | 99.00 | 96.66 | 100.00 | 96.99 |

| Shadows | 10 | 10 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.47 | 100.00 | 95.46 |

| OA(%) | 92.22 | 98.06 | 98.75 | 99.77 | 98.14 | ||

| AA(%) | 93.08 | 97.94 | 98.64 | 99.70 | 97.81 | ||

| Kappa | 89.79 | 97.44 | 98.34 | 99.70 | 97.55 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).