Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

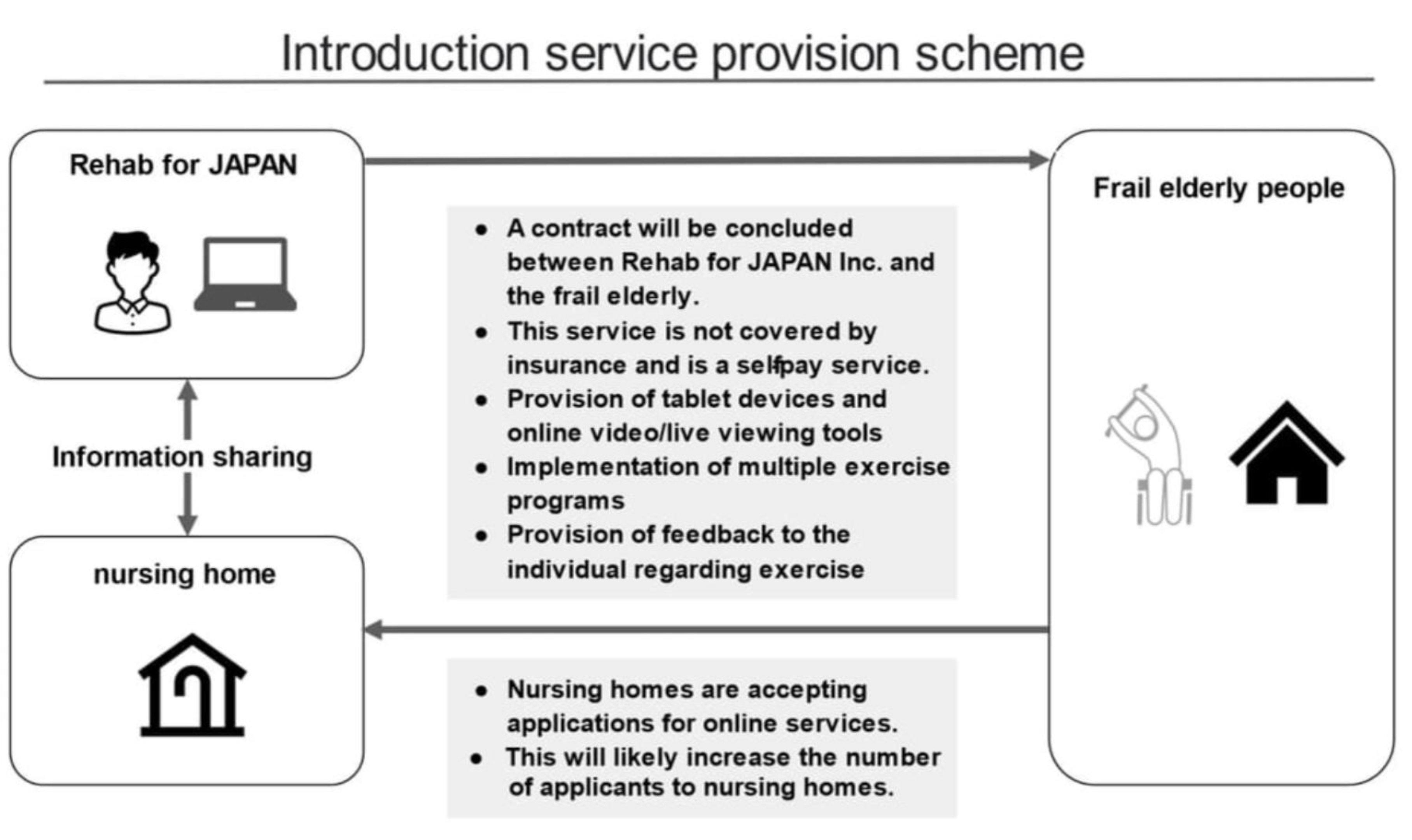

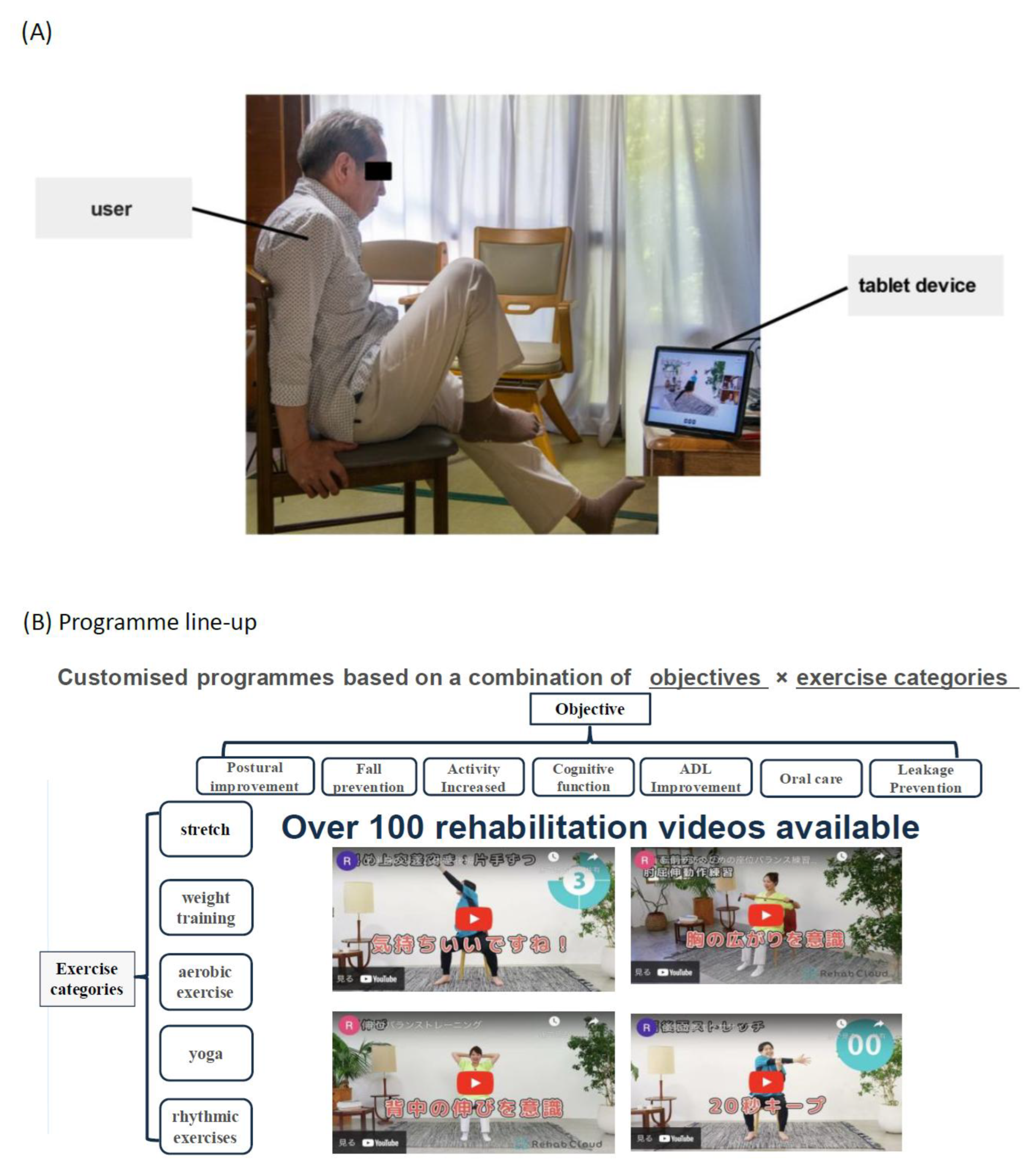

1.1. Development of Interventions

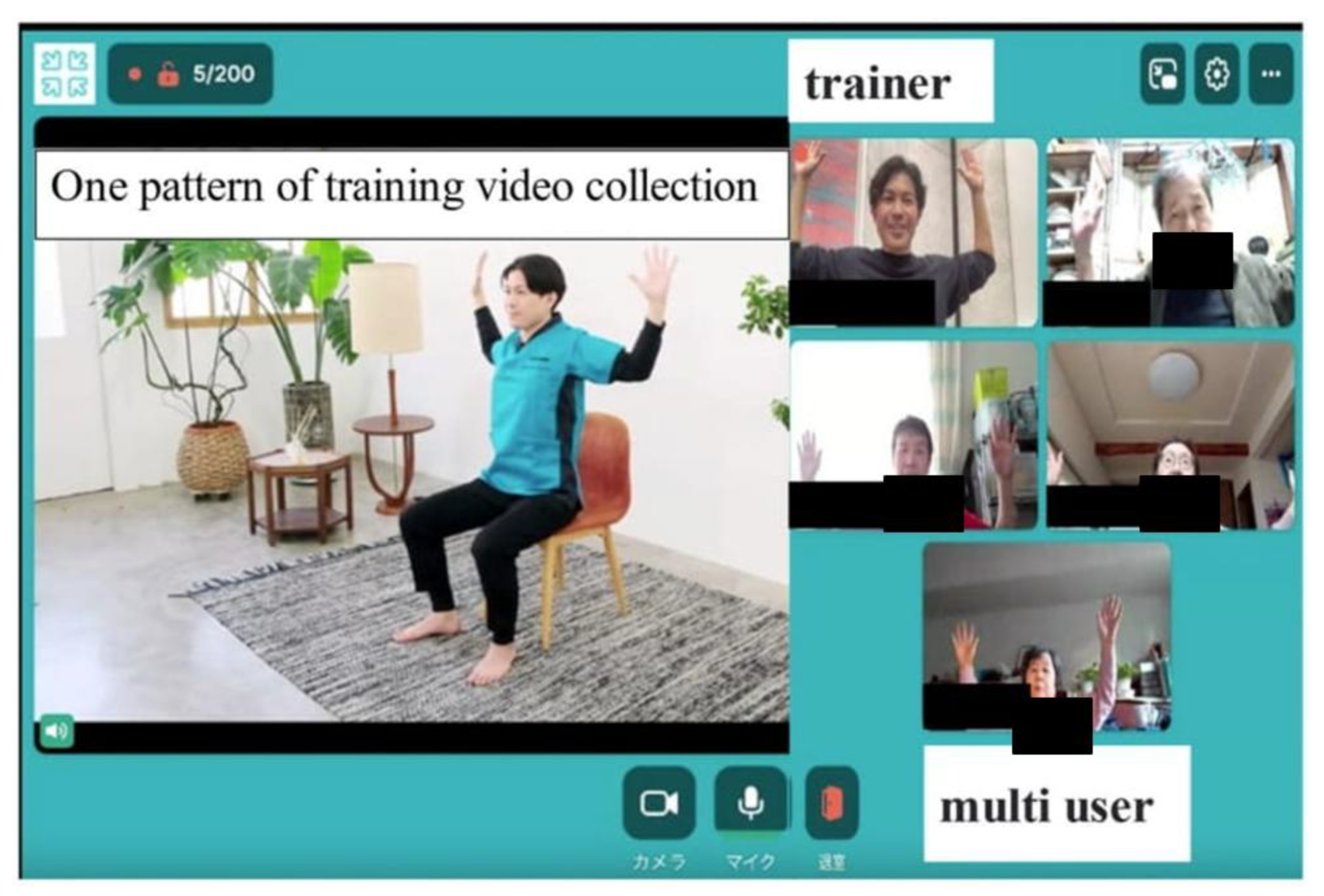

1.2. Pilot Test of Rehab Studio

2. Methods

2.1. Evaluation of the Intervention

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Clinical Significance

4.2. Social Engagement and Multiuser Format

4.3. Technological Accessibility

4.4. Exercise and Frailty Management

4.5. Healthcare Delivery Context

4.6. Study Limitations

4.7. Future Research and Clinical Implications

| Study | Country | Subject No. | older adult, frail/ other | telehealth/ mHealth | multiuser/ group | QOL outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsai et al., 20177 | Australia | 36 | yes, with COPD | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bernocchi et al., 201821 | Italy | 112 | yes, with heart failure and COPD | Yes | No | Yes |

| Lin et al., 201414 | Taiwan | 43 | yes, stroke | Yes | Yes | not evident |

| Kwan et al., 202016 | China | 99 | yes, cognitive frailty | Yes | Yes | not evident |

| Murukesu et al., 202122 | Malaysia | 42 | yes, cognitive frailty | No | Yes | Yes |

| Oursler et al., 202215 | USA | 80 | yes, with HIV | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Daniel, 201223 | USA | 23 | yes, prefrail | No | Yes | not evident |

| Cabrita et al., 201724 | the Netherlands | 10 | yes (not frail-specific, but frailty assessed) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zengin Alpozgen et al., 202217 | Turkey | 30 | yes (not frail-specific, with no other conditions specified) | Yes | No | Yes |

| Geraedts et al., 202125 | the Netherlands | 40 | yes, prefrail | Yes | Yes | not evident |

| Dekker-van Weering et al., 201726 | the Netherlands | 37 | yes, prefrail | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Li et al., 202027 | USA | 8 | yes, cognitively intact | Yes | Yes | not evident |

| Osuka et al., 202228 | Japan | 58 | yes, frail | Partly | Yes | Yes |

| Tekin, 202229 | Turkey | 255 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Tosi et al., 202130 | Brazil | 43 | yes, frail | Partly | No | not evident |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cordeiro ALL, da Silva Miranda A, de Almeida HM, et al. Quality of life in patients with heart failure assisted by telerehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Telerehabil 2022, 14, e6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arian M, Valinejadi A, Soleimani M. Quality of life in heart patients receiving telerehabilitation: An overview with meta-analyses. Iran J Public Health 2022, 51, 2388–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini S, Coraci D, Loreti C, et al. Prehabilitation and heart failure: main outcomes in the COVID-19 era. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022, 26, 4131–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike A, Sobue Y, Kawai M, et al. Safety and feasibility of a telemonitoring-guided exercise program in patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2022, 27, e12926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowicz E, Mierzyńska A, Jaworska I, et al. Relationship between physical capacity and depression in heart failure patients undergoing hybrid comprehensive telerehabilitation vs. usual care: Subanalysis from the TELEREH-HF Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2022, 21, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov Schacksen C, Dyrvig AK, Henneberg NC, et al. Patient-reported outcomes from patients with heart failure participating in the future patient telerehabilitation program: Data from the intervention arm of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Cardio 2021, 5, e26544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai LL, McNamara RJ, Moddel C, et al. Home-based telerehabilitation via real-time videoconferencing improves endurance exercise capacity in patients with COPD: The randomized controlled TeleR Study. Respirology 2017, 22, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayati F, Ayatollahi H, Hemmat M. A systematic review of the effectiveness of telerehabilitation interventions for therapeutic purposes in the elderly. Methods Inf Med 2020, 59, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saare M, Hussain, A, Seng Yue W. Investigating the effectiveness of mobile peer support to enhance the quality of life of older adults: a systematic literature review. Int J Interact Mob Technol 2019, 13, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam AS, van Leunen S, Aslam S, et al. A systematic review on the use of mHealth to increase physical activity in older people. Clinical eHealth 2020, 3, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam ACY, Chan AWY, Cheung DSK, et al. The effects of interventions to enhance cognitive and physical functions in older people with cognitive frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2022, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Md Fadzil NH, Shahar S, Rajikan R, et al. A scoping review for usage of telerehabilitation among older adults with mild cognitive impairment or cognitive frailty. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn N, Goetzinger C, Regnaux JP, et al. Digital health interventions among people living with frailty: a scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021, 22, 1802–1812.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin KH, Chen CH, Chen YY, et al. Bidirectional and multi-user telerehabilitation system: clinical effect on balance, functional activity, and satisfaction in patients with chronic stroke living in long-term care facilities. Sensors 2014, 14, 12451–12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oursler KK, Marconi VC, Briggs BC, et al. Telehealth exercise intervention in older adults with HIV: protocol of a multisite randomized trial. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2022, 33, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan RY, Lee D, Lee PH, et al. Effects of an mHealth brisk walking intervention on increasing physical activity in older people with cognitive frailty: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e16596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin Alpozgen A, Kardes K, Acikbas E, et al. The effectiveness of synchronous tele-exercise to maintain the physical fitness, quality of life, and mood of older people - A randomized and controlled study. Eur Geriatr Med 2022, 13, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vorst A, Zijlstra GAR, De Witte N, et al. Explaining discrepancies in self-reported quality of life in frail older people: a mixed-methods study. BMC Geriatr 2017, 17, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Arnal JF, et al. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcif Tissue Int 2013, 93, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraković S, Baraković Husić J, van Hoof J, et al. Quality of life framework for personalised ageing: a systematic review of ICT solutions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernocchi P, Vitacca M, La Rovere MT, et al. Home-based telerehabilitation in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murukesu RR, Singh DKA, Shahar S, et al. Physical activity patterns, psychosocial well-being and coping strategies among older persons with cognitive frailty of the "WE-RISE" trial throughout the COVID-19 movement control order. Clin Interv Aging 2021, 16, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, K. Wii-hab for pre-frail older adults. Rehabil Nurs 2012, 37, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrita M, Lousberg R, Tabak M, et al. An exploratory study on the impact of daily activities on the pleasure and physical activity of older adults. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraedts HAE, Dijkstra H, Zhang W, et al. Effectiveness of an individually tailored home-based exercise programme for pre-frail older adults, driven by a tablet application and mobility monitoring: A pilot study. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2021, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker-van Weering M, Jansen-Kosterink S, Frazer S, et al. User experience, actual use, and effectiveness of an information communication technology-supported home exercise program for pre-frail older adults. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017, 4, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li J, Hodgson N, Lyons MM, et al. A personalized behavioral intervention implementing mHealth technologies for older adults: a pilot feasibility study. Geriatr Nurs 2020, 41, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuka Y, Sasai H, Kojima N, et al. Adherence, safety and potential effectiveness of a home-based Radio-Taiso exercise program in older adults with frailty: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2023, 23, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin F, Nilufer CK. Effectiveness of a telerehabilitative home exercise program on elder adults' physical performance, depression and fear of falling. Percept Mot Skills 2022, 129, 714–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi FC, Lin SM, Gomes GC, et al. A multidimensional program including standing exercises, health education, and telephone support to reduce sedentary behavior in frail older adults: Randomized clinical trial. Exp Gerontol 2021, 153, 111472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res 2005, 14, 1523–1532.

- Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res 2013, 22, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013, 381, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. Physical frailty: ICFSR international clinical practice guidelines for identification and management. J Nutr Health Aging 2019, 23, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110, 5797–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale CR, Westbury L, Cooper C. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for the progression of frailty: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk EO, Suanet B, Dent E, et al. Adverse effects of frailty on social functioning in older adults: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Maturitas 2016, 83, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll-Planas L, Nyqvist F, Puig T, et al. Social capital interventions targeting older people and their impact on health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017, 71, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja SJ, Boot WR, Charness N, et al. Improving social support for older adults through technology: findings from the PRISM randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi NG, Dinitto DM. The digital divide among low-income homebound older adults: internet use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward computer/internet use. J Med Internet Res 2013, 15, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nymberg VM, Bolmsjö BB, Wolff M, et al. 'Having to learn this so late in our lives...' Swedish elderly patients' beliefs, experiences, attitudes and expectations of e-health in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2019, 37, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildenbos GA, Peute L, Jaspers M. Aging barriers influencing mobile health usability for older adults: a literature based framework (MOLD-US). Int J Med Inform 2018, 114, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse C, Fohn J, Wilson N, et al. Utilization barriers and medical outcomes commensurate with the use of telehealth among older adults: systematic review. JMIR Med Inform 2020, 8, e20359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Houwelingen CT, Ettema RG, Antonietti MG, et al. Understanding older people's readiness for receiving telehealth: mixed-method study. J Med Internet Res 2018, 20, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Labra C, Guimaraes-Pinheiro C, Maseda A, et al. Effects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatr 2015, 15, 154. [Google Scholar]

- Apóstolo J, Cooke R, Bobrowicz-Campos E, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent pre-frailty and frailty progression in older adults: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2018, 16, 140–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puts MTE, Toubasi S, Andrew MK, et al. Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review of the literature and international policies. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrington C, Michaleff ZA, Fairhall N, et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2017, 51, 1750–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari M, Vellas B, Hsu FC, et al. A physical activity intervention to treat the frailty syndrome in older persons—results from the LIFE-P study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015, 70, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1679–1681.

- Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL, et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare 2020, 26, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed T, Vafaei A, Belanger E, et al. Trajectories of limitations in activities of daily living among older adults in the International Mobility in Aging Study: persistence, recovery, and mortality. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 939–945. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Annual health, labour and welfare report 2019-2020. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2020.

- Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber J, Fonseca LM. How sample size influences research outcomes. Dental Press J Orthod 2014, 19, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332.

- Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simek EM, McPhate L, Haines TP. Adherence to and efficacy of home exercise programs to prevent falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of exercise program characteristics. Prev Med 2012, 55, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman RK, Buckworth J. Increasing physical activity: a quantitative synthesis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996, 28, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J Clin Epidemiol 2014, 67, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994, 49, M85–M94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon RW, Wang YC, Gershon RC. Two-minute walk test performance by adults 18 to 85 years: normative values, reliability, and responsiveness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015, 96, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essery R, Geraghty AW, Kirby S, et al. Predictors of adherence to home-based physical therapies: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2017, 39, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Smith BR, et al. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions for chronic disease management. Telemed J E Health 2014, 20, 769–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, et al. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, et al. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res 2017, 19, e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012, 345, e5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 2008, 337, a2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013, 158, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007, 39, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007, 55, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ 2013, 346, f1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiya N, Noguchi H, Nishi A, et al. Population ageing and wellbeing: lessons from Japan's long-term care insurance policy. Lancet 2011, 378, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell UA, Chebli PG, Ruggiero L, et al. The digital divide in health-related technology use: the significance of race/ethnicity. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell MA, Galea OA, O'Leary SP, et al. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2017, 31, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 67 | 82 | 80 | 80 | 82 | 81 |

| Sex | Male | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female |

| Disease name | OPLL, LDH | Hip osteoarthritis | LDH, DM | SAH | LCS, Lumbar Kyphosis | Lumbar compression fracture |

| Nursing care certification | Needs level 2 support | Needs level 2 support | Needs level 2 support | Needs level 1 support | Needs level 2 support | Needs level 2 support |

| EQ-5D-5L score pre-intervention | 0.55 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.82 | 0.66 |

| EQ-5D-5L score post-intervention | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).