Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Clinical Condition and Data Recovery

2.3. Treatment

2.4. TSQM-9 Questionnaire

2.5. PASI, DLQI and PGA Assessments

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Follow-Up and Treatments

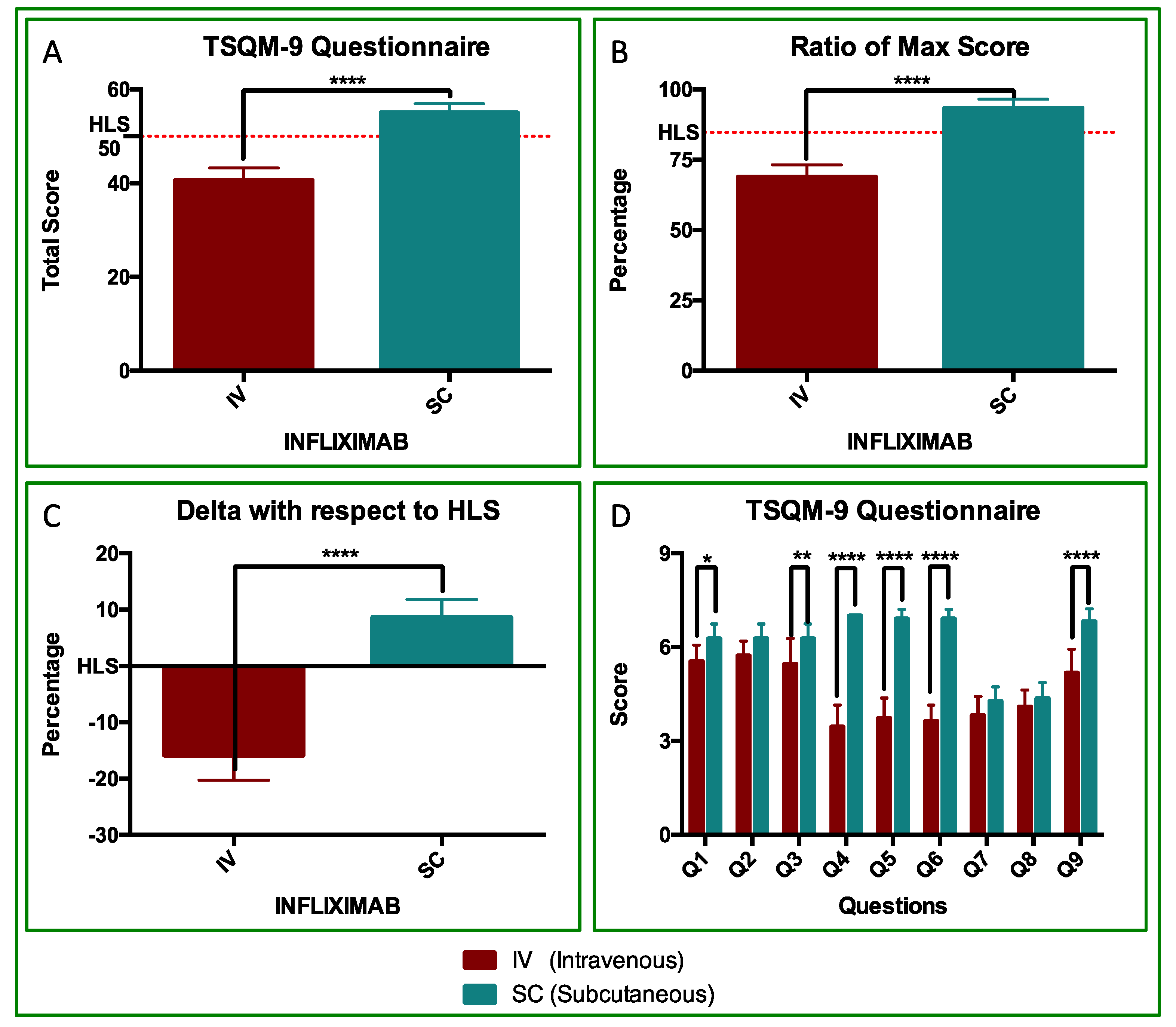

3.2. TSQM Analyses

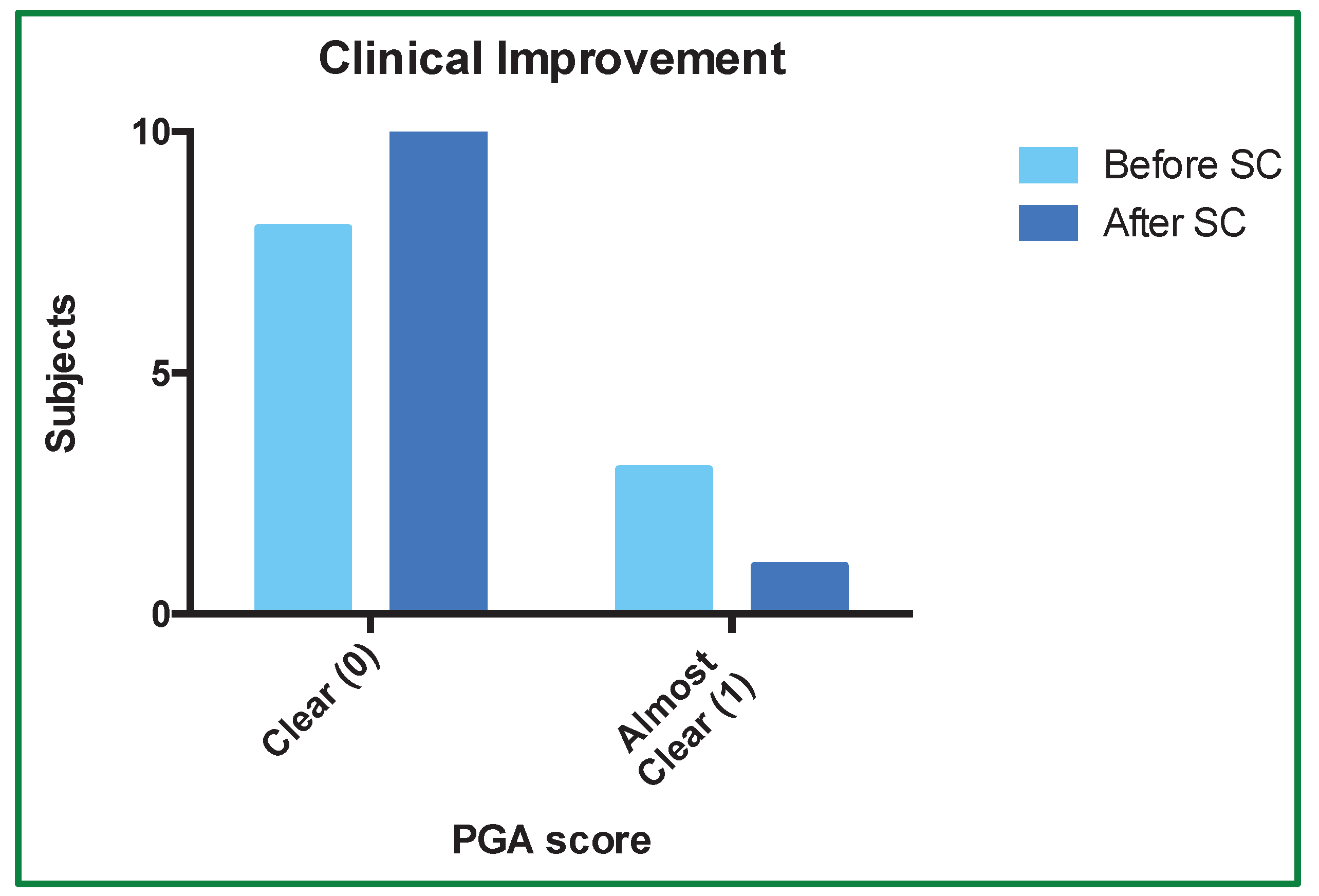

3.3. PGA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raharja, A.; Mahil, S.K.; Barker, J.N. Psoriasis: A Brief Overview. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, R.; Iskandar, I.Y.K.; Kontopantelis, E.; Augustin, M.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Ashcroft, D.M. National, Regional, and Worldwide Epidemiology of Psoriasis: Systematic Analysis and Modelling Study. BMJ 2020, m1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowietz, U.; Lauffer, F.; Sondermann, W.; Gerdes, S.; Sewerin, P. Psoriasis as a Systemic Disease. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Read, C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieminska, I.; Pieniawska, M.; Grzywa, T.M. The Immunology of Psoriasis—Current Concepts in Pathogenesis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 66, 164–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greb, J.E.; Goldminz, A.M.; Elder, J.T.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Gladman, D.D.; Wu, J.J.; Mehta, N.N.; Finlay, A.Y.; Gottlieb, A.B. Psoriasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2016, 2, 16082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, J.; Grewal, S.; Langan, S.M.; Mehta, N.N.; Ogdie, A.; Van Voorhees, A.S.; Gelfand, J.M. Psoriasis and Comorbid Diseases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsmond, A.; Bereza-Malcolm, L.; Lynch, T.; March, L.; Xue, M. Skin Barrier Dysregulation in Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.J.; Kavanaugh, A.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Gniadecki, R.; Merola, J.F. Psoriasis and Metabolic Syndrome: Implications for the Management and Treatment of Psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, R.G.; Cano, A.; Ortiz, A.; Espina, M.; Prat, J.; Muñoz, M.; Severino, P.; Souto, E.B.; García, M.L.; Pujol, M.; et al. Psoriasis: From Pathogenesis to Pharmacological and Nano-Technological-Based Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuyama, M.; Mabuchi, T. New Treatment Addressing the Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiya, E.; Tominaga, M.; Kamata, Y.; Suga, Y.; Takamori, K. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Itch in Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, H.; Lin, W.; Lu, L.; Su, J.; Chen, X. Signaling Pathways and Targeted Therapies for Psoriasis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendon, A.; Schäkel, K. Psoriasis Pathogenesis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, A.; Siewert, K.; Stöhr, J.; Besgen, P.; Kim, S.-M.; Rühl, G.; Nickel, J.; Vollmer, S.; Thomas, P.; Krebs, S.; et al. Melanocyte Antigen Triggers Autoimmunity in Human Psoriasis. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, D.; Chamilos, G.; Lande, R.; Gregorio, J.; Meller, S.; Facchinetti, V.; Homey, B.; Barrat, F.J.; Zal, T.; Gilliet, M. Self-RNA–Antimicrobial Peptide Complexes Activate Human Dendritic Cells through TLR7 and TLR8. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, A.S.; Cohen, J.; Fei, J.; Zaba, L.C.; Cardinale, I.; Toyoko, K.; Ott, J.; Krueger, J.G. Insights into Gene Modulation by Therapeutic TNF and IFNγ Antibodies: TNF Regulates IFNγ Production by T Cells and TNF-Regulated Genes Linked to Psoriasis Transcriptome. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowes, M.A.; Chamian, F.; Abello, M.V.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Lin, S.-L.; Nussbaum, R.; Novitskaya, I.; Carbonaro, H.; Cardinale, I.; Kikuchi, T.; et al. Increase in TNF-α and Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase-Expressing Dendritic Cells in Psoriasis and Reduction with Efalizumab (Anti-CD11a). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 19057–19062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.N.; Teague, H.L.; Swindell, W.R.; Baumer, Y.; Ward, N.L.; Xing, X.; Baugous, B.; Johnston, A.; Joshi, A.A.; Silverman, J.; et al. IFN-γ and TNF-α Synergism May Provide a Link between Psoriasis and Inflammatory Atherogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiricozzi, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Nograles, K.E.; Tian, S.; Cardinale, I.; Chimenti, S.; Krueger, J.G. Integrative Responses to IL-17 and TNF-α in Human Keratinocytes Account for Key Inflammatory Pathogenic Circuits in Psoriasis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.E.M.; Strober, B.E.; Van De Kerkhof, P.; Ho, V.; Fidelus-Gort, R.; Yeilding, N.; Guzzo, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, B.; Li, S.; et al. Comparison of Ustekinumab and Etanercept for Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, R.G.; Elewski, B.E.; Lebwohl, M.; Reich, K.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Papp, K.; Puig, L.; Nakagawa, H.; Spelman, L.; Sigurgeirsson, B.; et al. Secukinumab in Plaque Psoriasis — Results of Two Phase 3 Trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cargill, M.; Schrodi, S.J.; Chang, M.; Garcia, V.E.; Brandon, R.; Callis, K.P.; Matsunami, N.; Ardlie, K.G.; Civello, D.; Catanese, J.J.; et al. A Large-Scale Genetic Association Study Confirms IL12B and Leads to the Identification of IL23R as Psoriasis-Risk Genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 80, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, K.; Nestle, F.O.; Papp, K.; Ortonne, J.-P.; Evans, R.; Guzzo, C.; Li, S.; Dooley, L.T.; Griffiths, C.E.M. ; EXPRESS study investigators Infliximab Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis: A Phase III, Multicentre, Double-Blind Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2005, 366, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, C.L.; Powers, J.L.; Matheson, R.T.; Goffe, B.S.; Zitnik, R.; Wang, A.; Gottlieb, A.B. ; Etanercept Psoriasis Study Group Etanercept as Monotherapy in Patients with Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2014–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, C.L.; Kimball, A.B.; Papp, K.A.; Yeilding, N.; Guzzo, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Dooley, L.T.; Gordon, K.B. ; PHOENIX 1 study investigators Efficacy and Safety of Ustekinumab, a Human Interleukin-12/23 Monoclonal Antibody, in Patients with Psoriasis: 76-Week Results from a Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet Lond. Engl. 2008, 371, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, K.; Armstrong, A.W.; Langley, R.G.; Flavin, S.; Randazzo, B.; Li, S.; Hsu, M.-C.; Branigan, P.; Blauvelt, A. Guselkumab versus Secukinumab for the Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis (ECLIPSE): Results from a Phase 3, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2019, 394, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.B.; Blauvelt, A.; Papp, K.A.; Langley, R.G.; Luger, T.; Ohtsuki, M.; Reich, K.; Amato, D.; Ball, S.G.; Braun, D.K.; et al. Phase 3 Trials of Ixekizumab in Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Kim, M. Challenges and Future Trends in the Treatment of Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiricozzi, A.; Pimpinelli, N.; Ricceri, F.; Bagnoni, G.; Bartoli, L.; Bellini, M.; Brandini, L.; Caproni, M.; Castelli, A.; Fimiani, M.; et al. Treatment of Psoriasis with Topical Agents: Recommendations from a Tuscany Consensus. Dermatol. Ther. 2017, 30, e12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidemeyer, K.; Kulac, M.; Sechi, A.; Cazzaniga, S.; Naldi, L. Lasers for the Treatment of Psoriasis: A Systematic Review. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 19, 717–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sofi, R.F.; Bergmann, M.S.; Nielsen, C.H.; Andersen, V.; Skov, L.; Loft, N. The Association between Genetics and Response to Treatment with Biologics in Patients with Psoriasis, Psoriatic Arthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatore, F.; Villani, A. --P.; Tauber, M.; Viguier, M.; Guillot, B.; the Psoriasis Research Group of the French Society of Dermatology (Groupe de Recherche sur le Psoriasis de la Société Française de Dermatologie) French Guidelines on the Use of Systemic Treatments for Moderate--to--severe Psoriasis in Adults. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskins, M.; Dressler, C.; Werner, R.N.; Nast, A. Methods Report: Update of the German S3 Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriasis Vulgaris. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2018, 16, ddg.13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisondi, P.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Amerio, P.; Argenziano, G.; Bardazzi, F.; Bianchi, L.; Chiricozzi, A.; Conti, A.; Corazza, M.; Costanzo, A.; et al. Italian Adaptation of EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the Systemic Treatment of Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. Ital. J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nast, A.; Smith, C.; Spuls, P.I.; Avila Valle, G.; Bata--Csörgö, Z.; Boonen, H.; De Jong, E.; Garcia--Doval, I.; Gisondi, P.; Kaur--Knudsen, D.; et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis Vulgaris – Part 1: Treatment and Monitoring Recommendations. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2461–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nast, A.; Smith, C.; Spuls, P.I.; Avila Valle, G.; Bata--Csörgö, Z.; Boonen, H.; De Jong, E.; Garcia--Doval, I.; Gisondi, P.; Kaur--Knudsen, D.; et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis Vulgaris – Part 2: Specific Clinical and Comorbid Situations. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 281–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oon, H.H.; Tan, C.; Aw, D.C.W.; Chong, W.-S.; Koh, H.Y.; Leung, Y.-Y.; Lim, K.S.; Pan, J.Y.; Tan, E.S.-T.; Tan, K.W.; et al. 2023 Guidelines on the Management of Psoriasis by the Dermatological Society of Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore 2024, 53, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.A.; Guyatt, G.; Ogdie, A.; Gladman, D.D.; Deal, C.; Deodhar, A.; Dubreuil, M.; Dunham, J.; Husni, M.E.; Kenny, S.; et al. 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2019, 71, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balato, A.; Burlando, M.; Campanati, A.; Costanzo, A.; Chiricozzi, A.; Gisondi, P.; Malagoli, P.; Micali, G. ; the Psoriasis Working Group; Astrua, C.; et al. Strategies for Optimal Use of Biological Therapies in Managing Psoriasis: Focus on Secukinumab. Dermatol. Ther. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, M.; Vastarella, M.G.; Sullo, M.G.; Scavone, C.; Riccardi, C.; Campitiello, M.R.; Sportiello, L.; Rafaniello, C. Pregnancy Recommendations Solely Based on Preclinical Evidence Should Be Integrated with Real-World Evidence: A Disproportionality Analysis of Certolizumab and Other TNF-Alpha Inhibitors Used in Pregnant Patients with Psoriasis. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamrawi, R.I.; Ghiam, N.; Wu, J.J. Comparison of Psoriasis Guidelines for Use of IL-23 Inhibitors in the United States and United Kingdom: A Critical Appraisal and Comprehensive Review. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 1252–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, W.; Abarca, Y.A.; Ahmadi, Y.; Menon, V.B.; Zumárraga, D.A.; Rojas Gomez, M.C.; Basri, A.; Madala, R.S.; Girgis, P.; Nazir, Z. Shared Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Psoriasis: Unraveling the Connection. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.D.; Jo, H.; Cho, H.; Jang, W.; Park, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, K.; Oh, J.; Wen, X.; et al. Biologics Use for Psoriasis during Pregnancy and Its Related Adverse Outcomes in Pregnant Women and Newborns: Findings from WHO Pharmacovigilance Study. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.H.A.; Essam, M.; Anwar, I.; Shehab, H.; Komy, M.E. Psoriasis Paradox—Infliximab-Induced Psoriasis in a Patient with Crohn’s Disease: A Case Report and Mini-Review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 03000605231200270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dand, N.; Duckworth, M.; Baudry, D.; Russell, A.; Curtis, C.J.; Lee, S.H.; Evans, I.; Mason, K.J.; Alsharqi, A.; Becher, G.; et al. HLA-C*06:02 Genotype Is a Predictive Biomarker of Biologic Treatment Response in Psoriasis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 2120–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, A.; Nishikawa, K.; Yamada, F.; Yamanaka, K.; Nakajima, H.; Ohtsuki, M. Safety, Efficacy, and Drug Survival of the Infliximab Biosimilar CT--P13 in Post--marketing Surveillance of Japanese Patients with Psoriasis. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraliakos, X.; Tsiami, S.; Vijayan, S.; Jung, H.; Barkham, N. Real--world Evidence for Subcutaneous Infliximab (CT--P13 SC) Treatment in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis during the Coronavirus Disease (COVID--19) Pandemic: A Case Series. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e05205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, L.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Bossa, F.; Guerra, M.; Annese, M.; Manta, R.; Armandi, A.; Caviglia, G.P.; Todeschini, A.; Variola, A. When to Switch to Subcutaneous Infliximab? The RE-WATCH Multicenter Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, izaf172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, A.; Nachury, M.; Bazoge, M.; Yzet, C.; Wils, P.; Dodel, M.; Coban, D.; Pereira, B.; Fumery, M. Long--term Effectiveness and Acceptability of Switching from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated with Intensified Doses: The REMSWITCH--LT Study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisson, A.; Nachury, M.; Reymond, M.; Yzet, C.; Wils, P.; Payen, L.; Laugie, M.; Manlay, L.; Mathieu, N.; Pereira, B.; et al. Effectiveness of Switching From Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: The REMSWITCH Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2338–2346.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.N.; Hye Song, J.; Jin Kim, S.; Ha Park, Y.; Wan Choi, C.; Eun Kim, J.; Ran Kim, E.; Kyung Chang, D.; Kim, Y.-H. One-Year Clinical Outcomes of Subcutaneous Infliximab Maintenance Therapy Compared With Intravenous Infliximab Maintenance Therapy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, A. Safety and Efficacy of Transitioning Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab: A Single-Center Real-World Experience. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J.; Critchley, L.; Storey, D.; Gregg, B.; Stenson, J.; Kneebone, A.; Rimmer, T.; Burke, S.; Hussain, S.; Yi Teoh, W.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Elective Switching from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab [CT-P13]: A Multicentre Cohort Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viazis, N.; Karamanakos, A.; Mousourakis, K.; Christidou, A.; Fousekis, F.; Mpakogiannis, K.; Koukoudis, A.; Katsanos, K.; Christodoulou, D.; Cheila, M.; et al. Switching from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab in Patients with Immune Mediated Diseases in Clinical Remission. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1583401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditto, M.C.; Parisi, S.; Cotugno, V.; Barila, D.A.; Sardo, L.L.; Cattel, F.; Fusaro, E. Subcutaneous Infliximab CT-P13 without Intravenous Induction in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Case Report and Pharmacokinetic Considerations. Int J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 62, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imafuku, S.; Ohata, C.; Okubo, Y.; Tobita, R.; Saeki, H.; Mabuchi, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Murotani, K.; Kitabayashi, H.; Kanai, Y. Effectiveness of Brodalumab in Achieving Treatment Satisfaction for Patients with Plaque Psoriasis: The ProLOGUE Study. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2022, 105, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharmal, M.; Payne, K.; Atkinson, M.J.; Desrosiers, M.-P.; Morisky, D.E.; Gemmen, E. Validation of an Abbreviated Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM-9) among Patients on Antihypertensive Medications. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korman, N.J. Management of Psoriasis as a Systemic Disease: What Is the Evidence? Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetwood, J.D.; Arzivian, A.; Tran, Y.; Paramsothy, S.; Leong, R.W. Meta--Analysis: Intravenous Versus Subcutaneous Infliximab in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 62, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonaitis, L.; Marković, S.; Farkas, K.; Gheorghe, L.; Krznarić, Ž.; Salupere, R.; Mokricka, V.; Spassova, Z.; Gatev, D.; Grosu, I.; et al. Intravenous versus Subcutaneous Delivery of Biotherapeutics in IBD: An Expert’s and Patient’s Perspective. BMC Proc. 2021, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score | Category | Description |

| 0 | Clear | No sign of plaque psoriasis |

| 1 | Almost clear | Just perceptible erythema and just perceptible scaling |

| 2 | Mild | Light pink erythema with minimal scaling with or without pustules |

| 3 | Moderate | Dull red, clearly distinguishable erythema with diffusing scaling, some thickening of the skin, with or without fissures, with of without pustule formation |

| 4 | Severe | Deep, dark red erythema with obvious and diffuse scaling and thickening as well as numerous fissures with of without pustule formation |

| PT ID | Demographics | Diagnosis | Infliximab IV Treatment | Infliximab SC Treatment | TTT | |||||

| Age | Gender | Months | PASI | DLQI | Months | PASI | DLQI | |||

| 1 | 23 | F | Plaque Psoriasis | 38 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| 2 | 54 | F | Plaque Psoriasis | 16 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 28 |

| 3 | 47 | M | Plaque Psoriasis | 9 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| 4 | 49 | F | Plaque Psoriasis | 12 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 24 |

| 5 | 66 | M | Plaque Psoriasis | 11 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 23 |

| 6 | 52 | M | Plaque Psoriasis | 28 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| 7 | 22 | F | Plaque Psoriasis | 19 | 0 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

| 8 | 42 | M | Plaque Psoriasis | 30 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 42 |

| 9 | 32 | F | Plaque Psoriasis | 16 | 0 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 28 |

| 10 | 81 | M | Plaque Psoriasis | 22 | 0 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 34 |

| 11 | 32 | F | Plaque Psoriasis | 22 | 0 | 8 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| Mean | 45.5 | 20.27 | 0.91 | 4.27 | 12 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 32.36 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).