1. Introduction

As a core mechanism in spatial governance during the stock era, urban renewal has become central to territorial spatial planning, aiming to optimize urban space and promote sustainable development [

1,

2]. The exploration of stock development in China began in Shenzhen, where the paradigm shifted from incremental expansion to stock optimization, forming a consensus among governments, markets, and society [

3,

4]. Innovative practices integrating intelligent interactions between land resources and planning systems are essential for revitalizing inefficient land and fostering resilient cities [

5].

Identifying inefficient stock land is fundamental to urban renewal, enabling spatial structure optimization and improved land-use efficiency. Internationally, the concept derives from Brownfield studies on abandoned or underutilized land [

6,

7,

8]. In China, the definition has evolved across regions: Guangzhou proposed “legacy redevelopment zones,” Shanghai and Shenzhen adopted “urban renewal units,” while other cities used “urban inefficient land redevelopment.” The 2013 Guidance by the Ministry of Natural Resources defined inefficient land as scattered, extensively utilized, and unreasonably used urban land, later expanded in 2023 to include both urban and rural construction land—marking a transition from fragmented redevelopment to systematic spatial optimization.

Existing studies mainly address land-use efficiency evaluation and optimization [

9,

10,

11,

12]. International research emphasizes remote sensing and rating-based assessments [

13,

14], while domestic studies focus on governance mechanisms [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], identification and causation [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], redevelopment potential [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], and renewal strategies [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Case studies in cities such as Beijing [

36], Shenzhen [

3,

18], Guangzhou [

21], Zhuhai [

37], Chengdu [

22,

38], Nanjing [

26,

27], Suzhou [

25], and Changzhou [

39] focus primarily on residential [

40,

41] and industrial land [

30,

34,

42], yet comprehensive analyses across land-use types remain limited.

Despite these contributions, three main gaps persist. First, most studies are city-specific and indicator-driven, lacking a unified framework that bridges multiple land-use types and scales. Second, temporal evolution and spatial clustering mechanisms of inefficient land remain insufficiently explored, particularly the marginal aggregation and functional transition patterns in rapidly urbanizing cities like Shenzhen. Third, evaluation systems often rely on static or expert-weighted indices, limiting adaptability to dynamic data. Hence, a scalable, data-driven method integrating multisource geospatial and socioeconomic information is needed to uncover spatial regularities and transformation potentials of inefficient land.

Technologically, territorial spatial planning initiatives have advanced the evaluation of inefficient land. Drone mapping, oblique photogrammetry, and remote sensing support high-resolution spatial data acquisition [

43,

44,

45]. GIS-based databases enable efficiency evaluation by functional attributes [

46,

47,

48], while machine learning, particularly CNN-based image recognition, assists spatial function classification and land-use performance assessment [

49,

50,

51,

52]. Multidimensional urban health assessments combine social, economic, and environmental indicators [

32], with AHP and Delphi methods commonly used for weighting [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. However, existing approaches remain limited by subjective index selection, intensive fieldwork, and weak temporal continuity [

37,

58].

To address these challenges, this study proposes a spatiotemporal big data–driven framework for identifying inefficient stock land. By integrating social, economic, and ecological indicators, it constructs an adaptive evaluation system with entropy-based weighting and GIS-based multi-criteria analysis for spatial classification. Using Shenzhen as a case, the study reveals an edge aggregation pattern, where inefficient land clusters along urban peripheries and transition zones, reflecting the dynamics of spatial restructuring under the stock-oriented paradigm. The framework enables rapid, large-scale, and low-cost identification of inefficient land, generating a comprehensive database that supports redevelopment planning and spatial optimization in megacities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

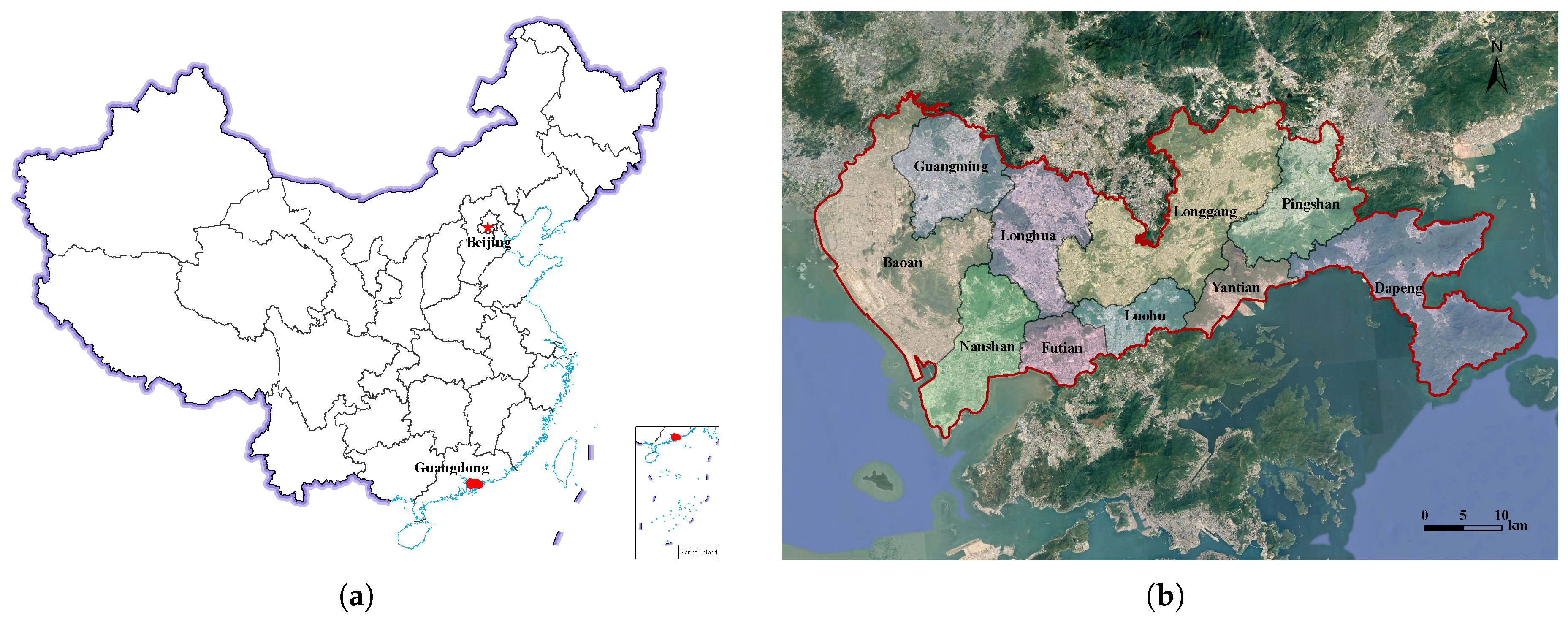

Shenzhen, located in southern China, covers a total area of 1,997.47 km². According to the city’s official statistics, it had a permanent population of 17.10 million at the end of 2019, with an urbanization rate of 99.81%, ranking first among Chinese cities[

3]. As the first city in China to enter the era of urban stock renewal, Shenzhen provides a valuable case for studying spatial restructuring and redevelopment strategies. By 2019, its total construction land area had reached 940.00 km² , making the efficient use of existing land a critical issue. In 2023, projects such as the Yuanfen New Village renewal and the Maozhou River ecological restoration were selected as exemplary cases in the first batch of national urban renewal demonstrations, reflecting the city’s ongoing transition from incremental expansion to high-quality stock optimization.

This study selects 2019 as the reference year for identifying inefficient stock land. The year serves as a temporal benchmark that precedes major policy shifts and disruptions in urban construction, ensuring data stability and comparability. Most datasets—including land-use, population, and economic indicators—were derived from official 2019 statistical and spatial records, representing the latest period with complete and consistent cross-sectoral data.

Cross-year information (e.g., 2023 demonstration projects) is used only for interpretative validation, to contextualize subsequent planning practices rather than for direct quantitative analysis. In cases where auxiliary datasets span multiple years (e.g., remote sensing or socio-economic data from 2018–2020), spatial normalization and temporal interpolation were applied to maintain consistency with the 2019 baseline. This ensures that the spatial patterns of inefficient land identified in the study remain methodologically consistent and temporally comparable.

Figure 1 shows the administrative divisions of Shenzhen in 2019, with an inset locating the city within southern China. This provides the necessary regional context for subsequent spatial analyses while maintaining a focus on the urban administrative scope.

2.2. Data Sources and Data Processing

The year 2019 serves as the key temporal reference for this study. To ensure methodological rigor and facilitate cross-domain applicability, the selection of spa-tio-temporal big data adhered strictly to criteria of verifiability, accessibility, compara-bility, and computability. The utilized datasets encompass building data, land use data, population data, transportation data, economic statistics, and air quality data. Specifi-cally, building data and Point of Interest (POI) data are sourced from the Baidu API, while traffic flow (Origin-Destination, OD) data are obtained from the Amap API. Population and GDP data with a 1 km spatial resolution are provided by the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Land use classification data are sourced from the Shenzhen Planning and Natural Re-sources Bureau, and CO

Data are obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center. Detailed data sources and descriptions are shown in

Table 1.

Population and GDP data reflect regional economic vitality. Remote sensing images are used to acquire various land use types, such as farmland, forest land, and urban construction land, which serve as the fundamental units for Habitat Quality calculations. Additionally, CO2 concentration data is integrated to assess the ecological environment.

Transportation OD and POI data are spatially processed for mapping and spatial analysis. Traffic coverage is calculated based on POI transportation facilities, referencing the Design Code for Urban Road and Transportation Planning, which considers a reasonable distance of 800 meters for bus stops and 1500 meters for subway stations when analyzing transportation accessibility.

The acquired multi-source data undergoes deduplication, missing value interpolation, and outlier removal. Non-spatial data is rasterized, and a GIS-based database is established. Spatial data undergoes coordinate projection transformation and geospatial registration. The registered data is clipped using the shapefile of Shenzhen for subsequent spatial overlay analysis. Finally, ArcMap 10.5 is used to integrate multi-source geographic data through a combination of GIS spatial analysis tools.

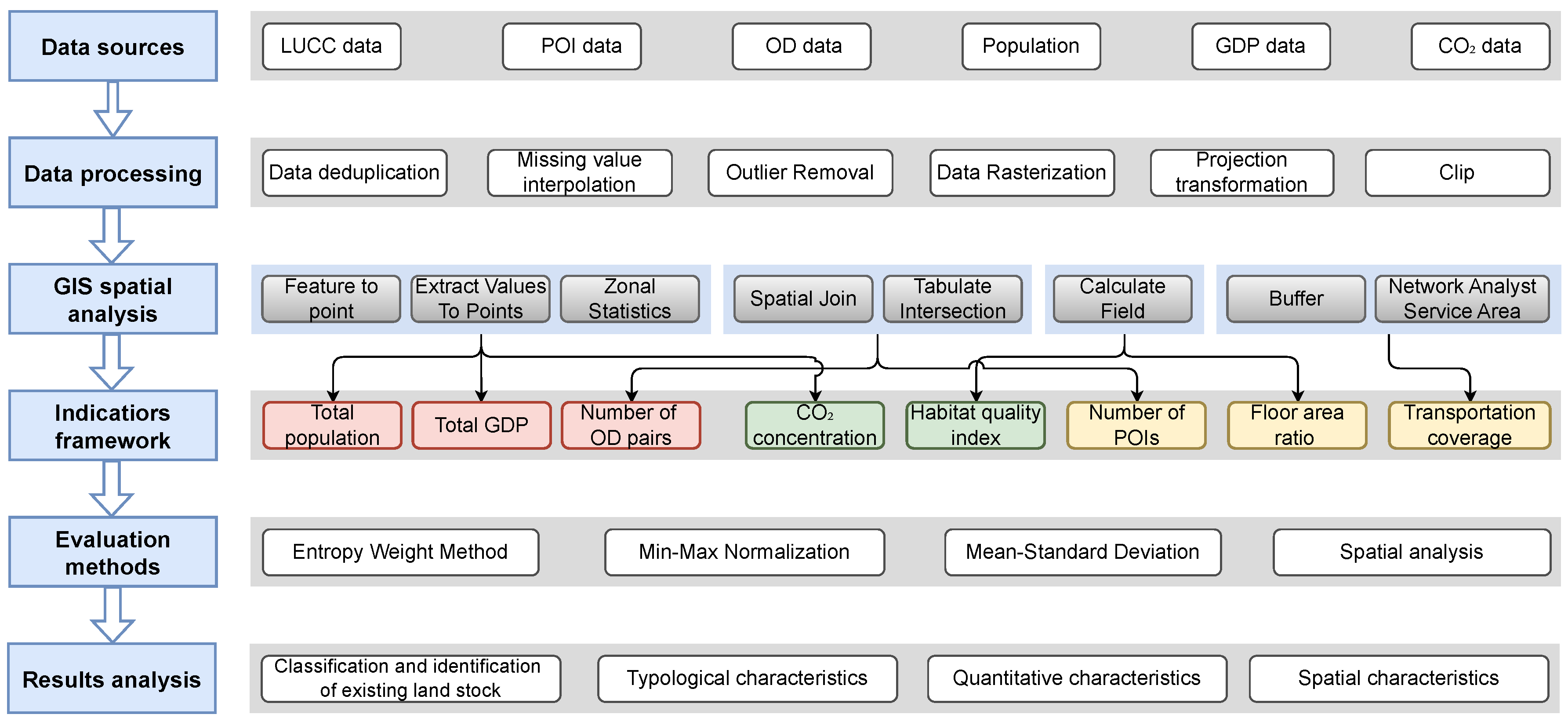

2.3. Methods

The study employs GIS spatial analysis techniques to quantify indicators and conduct weighted overlay analysis for identifying inefficient stock land. The technical framework is illustrated in

Figure 2. Drawing on previous research and standards, and considering Shenzhen’s regional characteristics, the study selects appropriate indicators from social, economic, and ecological dimensions to construct an indicator system for identifying inefficient stock land. The entropy weight method is used to determine indicator weights, and GIS spatial analysis is utilized for multi-indicator comprehensive evaluation. The results are classified using the mean–standard deviation method, with the first-level results serving as the identification criteria for inefficient stock land. Further analysis is conducted on its quantity and spatial variation characteristics.

2.3.1. Indicator System Based on a Multi-Factor Comprehensive Evaluation Method

This study is based on the intrinsic attributes of land resources, taking a comprehensive approach that balances social, economic, and ecological value orientations. Referring to the

Standard for Evaluation of Saving and Intensive Use of Construction Land, an indicator system for identifying inefficient stock land was established through expert consultation, literature review, standard inquiries, and factor selection methods. From a social perspective, residents’ quality of life, transportation accessibility, and public service facilities are essential aspects of measuring social benefits. The study selects three indicators—floor area ratio (FAR), transportation facility coverage (TFC), and living convenience (LC)—to quantify the contribution of land resources to social development. To assess economic benefits, indicators such as population size (POP), economic vitality (GDP), and human activity index (HAI) are used to reflect the role of different land use types in economic performance. For environmental benefits, ecological quality and pollutant emissions serve as key indicators of whether land development and utilization align with sustainability principles. Therefore, this study adopts the habitat quality index (HQ) and air quality index (AQ) as two indicators to represent environmental benefits. In summary, considering factors such as representativeness, suitability, dominance, and data availability, the study establishes a set of eight universal indicators across three dimensions. Detailed descriptions and calculation formulas are provided in

Table 2.

2.3.2. Indicator Weights Determination

In this study, the entropy weight method is employed to calculate the weights of each indicator factor. The entropy weight method is an objective weighting technique based on information entropy theory, which determines indicator weights according to the degree of variation in the data [

15]. It primarily consists of three steps: indicator normalization, entropy value calculation, and entropy weight determination. Compared to other weighting methods—such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (subjective weighting), CRITIC method (based on correlation and standard deviation), and Principal Component Analysis (dimensionality reduction)—the entropy weight method effectively reflects the relative importance of indicators without subjective bias.

Indicator normalization eliminates the influence of different units and scales using the min–max normalization method (Equation

1). The entropy value quantifies the information content of each indicator (Equation

3), and the final weights are derived from the normalized difference coefficients (Equations

2 and

4).

Here, denotes the original value of the j-th indicator for the i-th spatial unit; is the normalized value; and are the minimum and maximum values of the j-th indicator across all n spatial units; represents the proportion of the i-th unit in the j-th indicator; is the entropy value of the j-th indicator (); and is the final weight assigned to the j-th indicator. Note that if (i.e., no variation), the indicator is excluded from weighting as it provides no discriminative information.For the three dimensions—social, economic, and ecological—the dimension-level weight is computed as the sum of the weights of its constituent sub-indicators.

2.3.3. Mean-Standard Deviation Classification

The Mean–Standard Deviation method is a well-established data classification technique [

16]. This study combines multi-objective weighted evaluation results with standard deviation thresholds to classify land into six levels (

Table 3). The results of the first level are taken as the basis for the selection of inefficient stock land. Here,

represents the comprehensive evaluation result, which is the weighted sum of the weights of each indicator and the indicator factors;

represents the average value of the comprehensive evaluation results; and

represents the standard deviation of the comprehensive evaluation.

2.3.4. Local Moran’s I

Local Moran’s I is a method for assessing the local spatial autocorrelation of spatial data [

17] (Equation

5). By calculating the weights of each spatial unit and its adjacent spatial units, it verifies the spatial clustering and spatial heterogeneity of the region. A positive value indicates that a certain geographical feature and its neighboring units share similar high or low values, suggesting a clustered distribution of this feature; a negative value denotes values with distinct attribute characteristics, identifying them as outliers. When passing the

p-test (

), the clustered distribution and outliers hold statistical significance.

Here, represents the attribute of element i, is the global mean of the attribute across all n spatial elements (not just adjacent ones), is the spatial weight between element i and element j (commonly defined by distance or contiguity), and n is the total number of spatial units in the study area.

3. Results

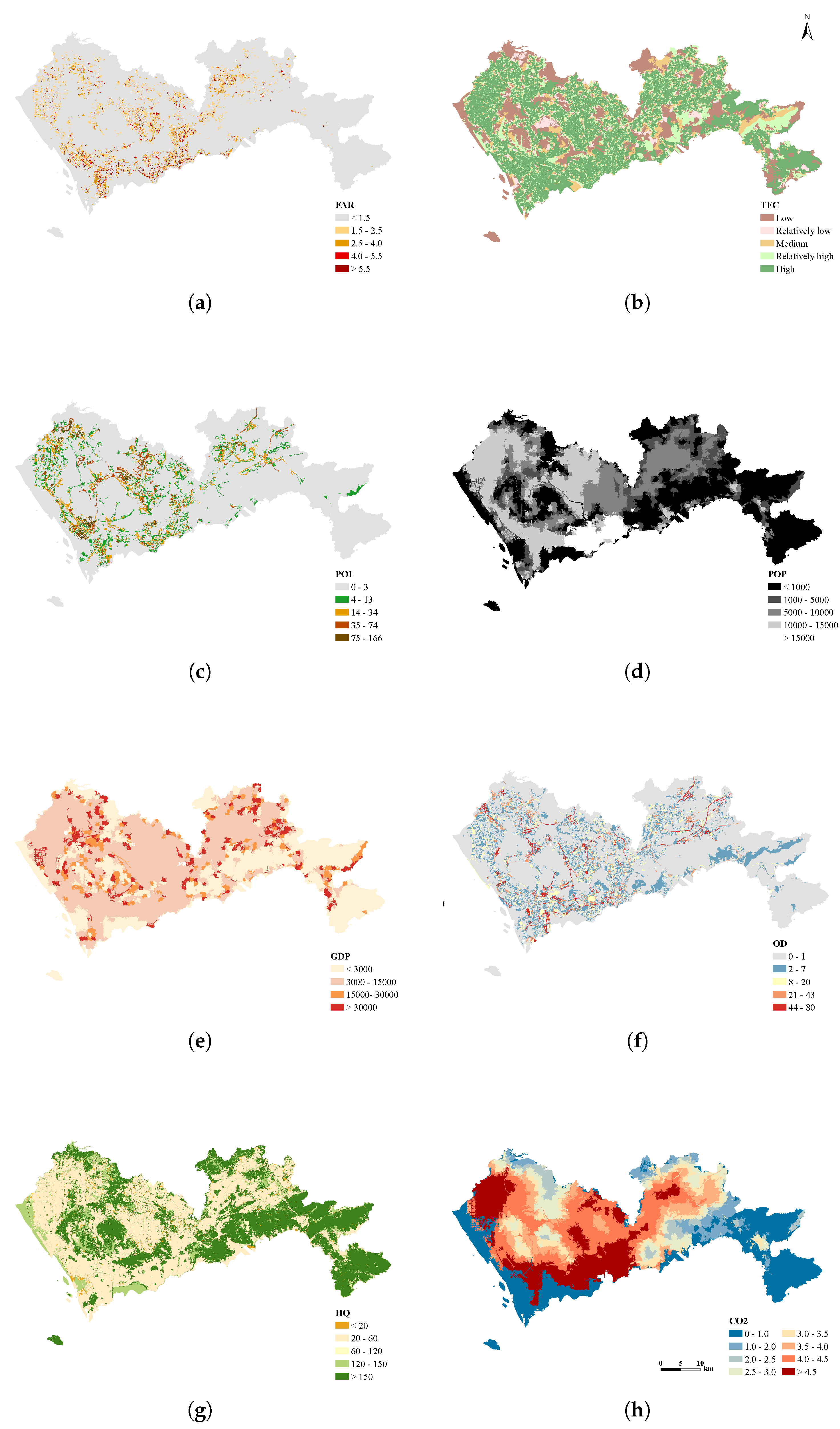

3.1. Spatial Heterogeneity Characteristics of Indicators

Based on the theoretical framework of geographical spatial heterogeneity, this study applied the Natural Breaks Classification method to categorize eight core indicators into five levels and visualize their spatial patterns (

Figure 3). The classification, which minimizes intra-class variance while maximizing inter-class differentiation, objectively identifies the spatial heterogeneity of each indicator across Shenzhen.

The analysis is based on multi-source geospatial data from 2019, representing the most recent period of stable urban development before subsequent socio-economic fluctuations. This dataset therefore provides a consistent and representative baseline for analyzing spatial structures and urban dynamics in Shenzhen.

The spatial visualization results reveal several key patterns. First, the transportation network shows extensive coverage and a relatively homogeneous distribution. The Floor Area Ratio (FAR) forms a dense, continuous belt along the urban corridor from Luohu to Nanshan near the Shenzhen–Hong Kong boundary, displaying a pronounced distance-decay gradient from the urban core outward. The high-value clusters of population and GDP exhibit a westward shift, with the Bao’an Central Area and Qianhai Cooperation Zone emerging as new growth poles alongside the traditional CBD. Both static POI and dynamic OD data confirm that Shenzhen’s urban vitality hotspots follow an agglomeration–diffusion pattern centered on major commercial clusters such as Coastal City, the Convention and Exhibition Center, the Science and Technology Park, and MixC World.

Furthermore, ecological indicators show a strong spatial coupling between habitat quality and the distribution of forests, wetlands, and water systems within the ecological control boundary, underscoring the regulating functions of key ecological nodes. The CO2 concentration displays a typical “low–high–low” concentric gradient: lower in western coastal and eastern Dapeng areas, peaking in the dense urban core, and gradually decreasing toward peripheral ecological zones. This pattern aligns with Shenzhen’s polycentric urban form, reflecting the spatial concentration of anthropogenic emissions in high-density development areas.

3.2. Multidimensional Indicators Weight Analysis

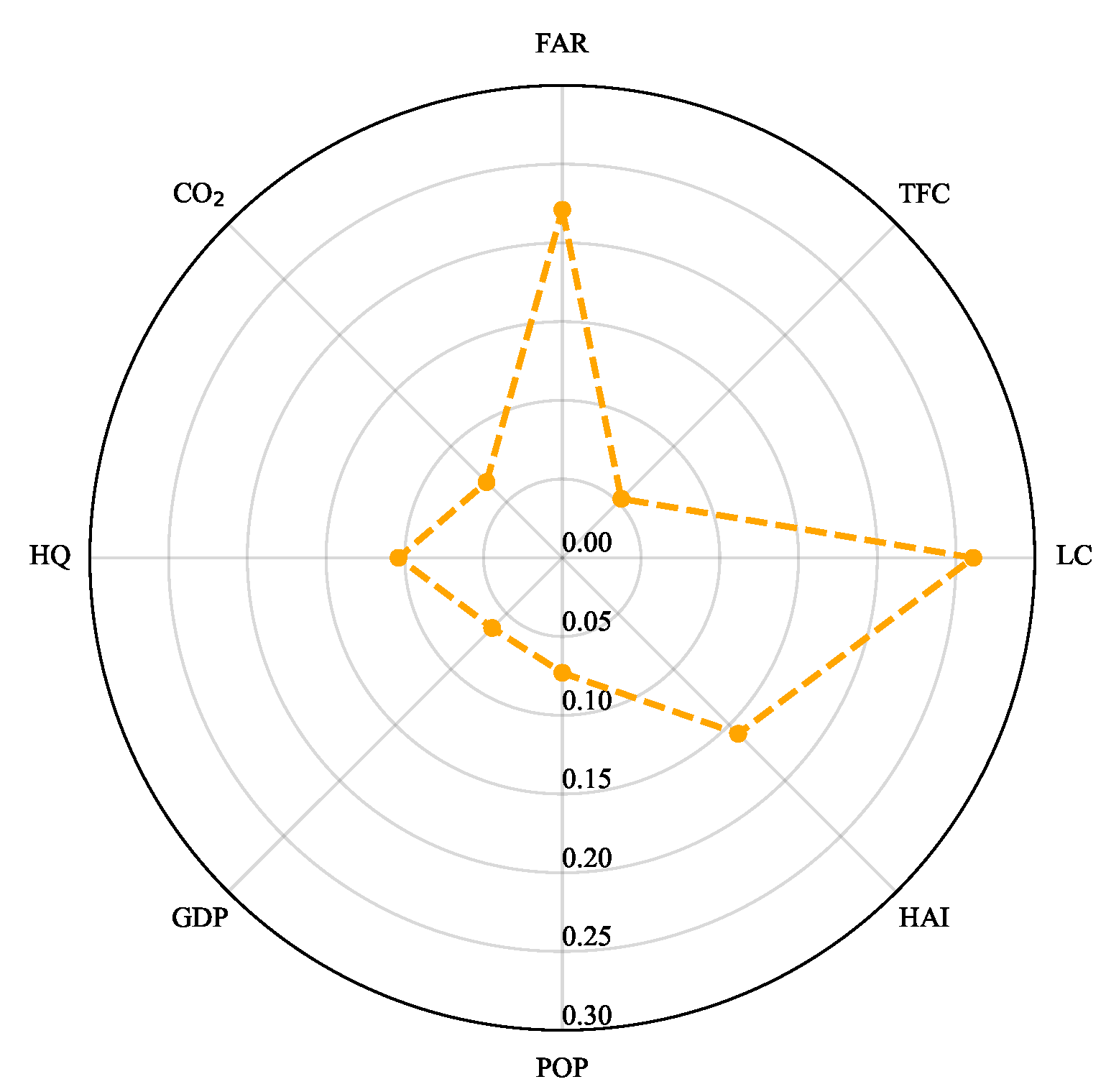

The indicator weight system constructed based on information entropy theory (

Figure 4) reveals the heterogeneous characteristics of factors influencing urban spatial efficiency. The entropy weight method calculation results, as illustrated in the radar chart (

Table 4), indicate that LC (0.261) and FAR (0.221) constitute the core driving factors, with a cumulative contribution rate of 48.2%, underscoring the dominant role of urban functional mix and spatial intensity in the evaluation of existing land use. In contrast, transportation facility coverage (0.053) exhibits the lowest weight, which aligns with the relatively balanced distribution of transportation facilities in Shenzhen, as shown in

Figure 3. The homogeneous distribution of infrastructure results in significantly lower information entropy for this indicator compared to others. The convergence of weights for total population (0.073), CO

2 concentration (0.068), and GDP (0.063) warrants attention, with a possible explanation being the reduced sensitivity of these indicators due to the 1 km × 1 km spatial resolution limitation.

From a systemic dimension analysis, the weights of social indicators (0.534), economic indicators (0.294), and ecological indicators (0.172) exhibit structural coupling with Shenzhen’s polycentric axial expansion urban spatial morphology. The dominant weights of the first two categories reflect the synergistic development of “scale–efficiency” in high-density built-up areas, while stable pattern of ecological indicators reduces their decision-making weight, scientifically validating the effectiveness of Shenzhen’s ecological control line policy.

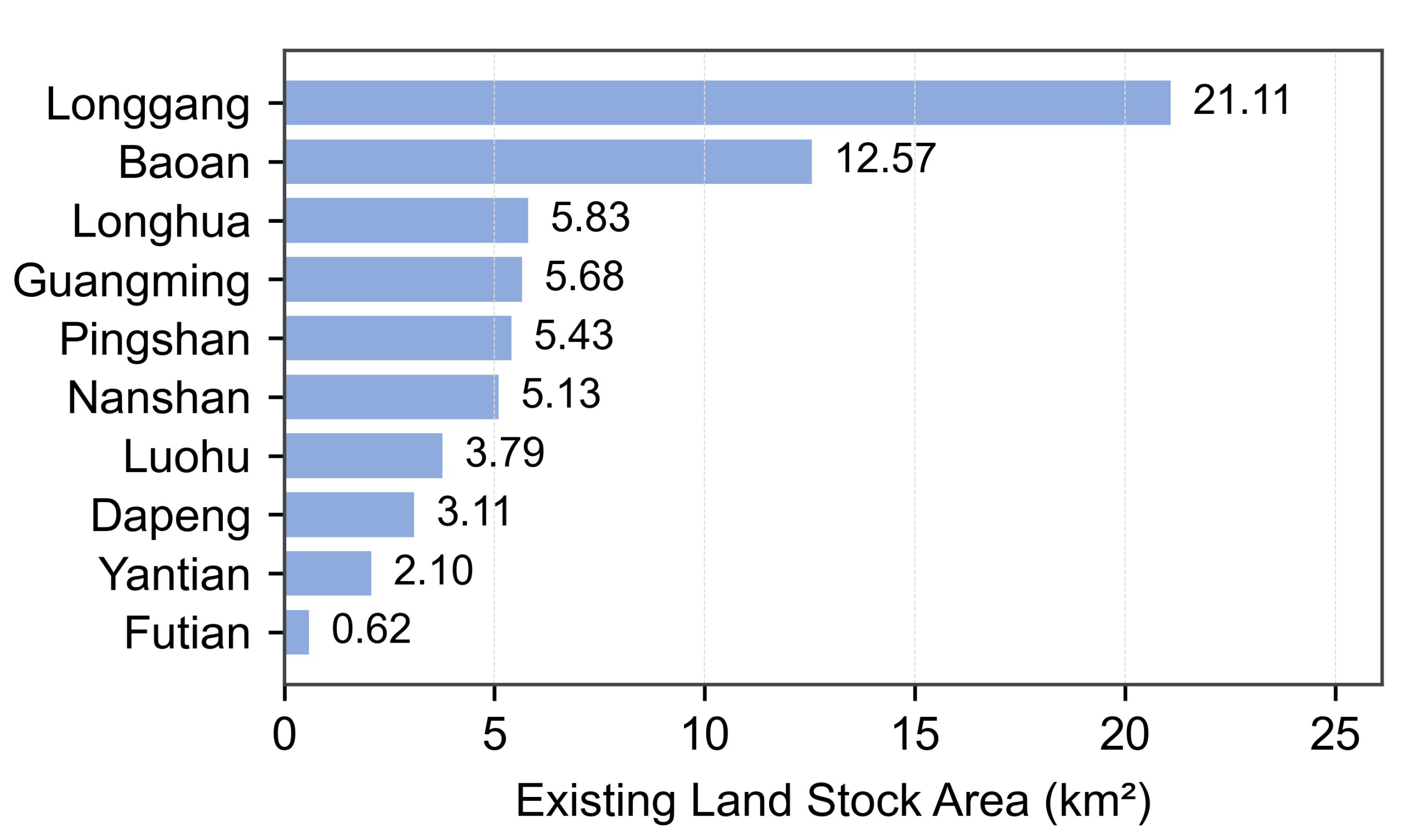

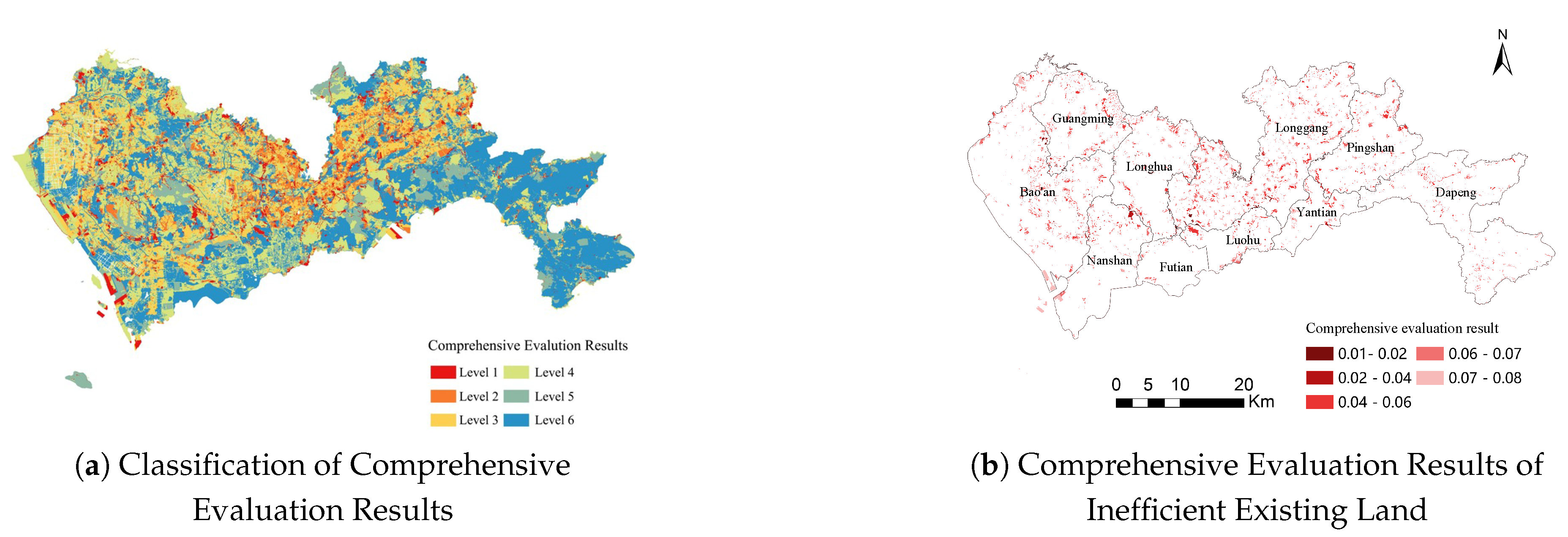

3.3. Identification Results of Existing Land Stock Area

Using spatial weighted overlay analysis and a mean–standard deviation classification model, areas with comprehensive evaluation scores below one standard deviation from the mean (i.e., the lowest grade in the evaluation results) were identified as inefficient existing land area (

Figure 5). The study identified a total of 65.37 km

2 of inefficient existing land in Shenzhen, accounting for approximately 7% of the city’s construction land in 2019. This result is consistent with publicly reported figures indicating that Shenzhen’s stock residential land area reached approximately 1000 hectares (10 km

2) in 2019, with residential land accounting for approximately 15–20% of the total inefficient existing land. Clusters mainly appear in the northwestern part of the city, including administrative boundary zones and urban fringe areas, exhibiting a notably homogeneous spatial distribution pattern. After overlaying land use data and excluding non-target plots such as scenic spots within the ecological control line and major infrastructure sites (e.g., airports, ports), the identified inefficient land (

Figure 5b) serves as the result for Shenzhen’s inefficient existing land in 2019.

Spatial statistical analysis indicates a significant negative correlation between the scale of inefficient land and the level of regional development. The inefficient existing land in Shenzhen is primarily distributed in the northwestern part of the city, including administrative boundary zones and urban fringe areas. Specifically, Longgang District (21.11 km2) and Baoan District (12.57 km2) collectively contribute 51.5% of the inefficient land, which is directly related to their “urban–rural intertwined” spatial morphology. In contrast, the low value in Futian Central District (0.62 km2) confirms the saturation of land use in high-intensity development zones. The inefficient land in Nanshan District (5.13 km2) is mainly concentrated around Xili University Town, reflecting the lag in functional replacement of educational and scientific land in response to the city’s innovation-driven development strategy. Dapeng New District (3.11 km2), as an ecotourism-dominated area, has inefficient land primarily due to development control of unused coastal land. Notably, Longhua (5.83 km2), Guangming (5.68 km2), Pingshan (5.43 km2), Nanshan (5.13 km2), and Luohu (3.79 km2) exhibit similar scales of inefficient existing land, forming a medium-gradient cluster. The structured differences in land use efficiency among administrative units spatially correspond to Shenzhen’s polycentric networked urban spatial structure.

Figure 6.

Area of Inefficient Existing Land in Shenzhen’s Administrative Districts (2019).

Figure 6.

Area of Inefficient Existing Land in Shenzhen’s Administrative Districts (2019).

3.4. Spatial Patterns and Driving Forces of Inefficient Land Stock

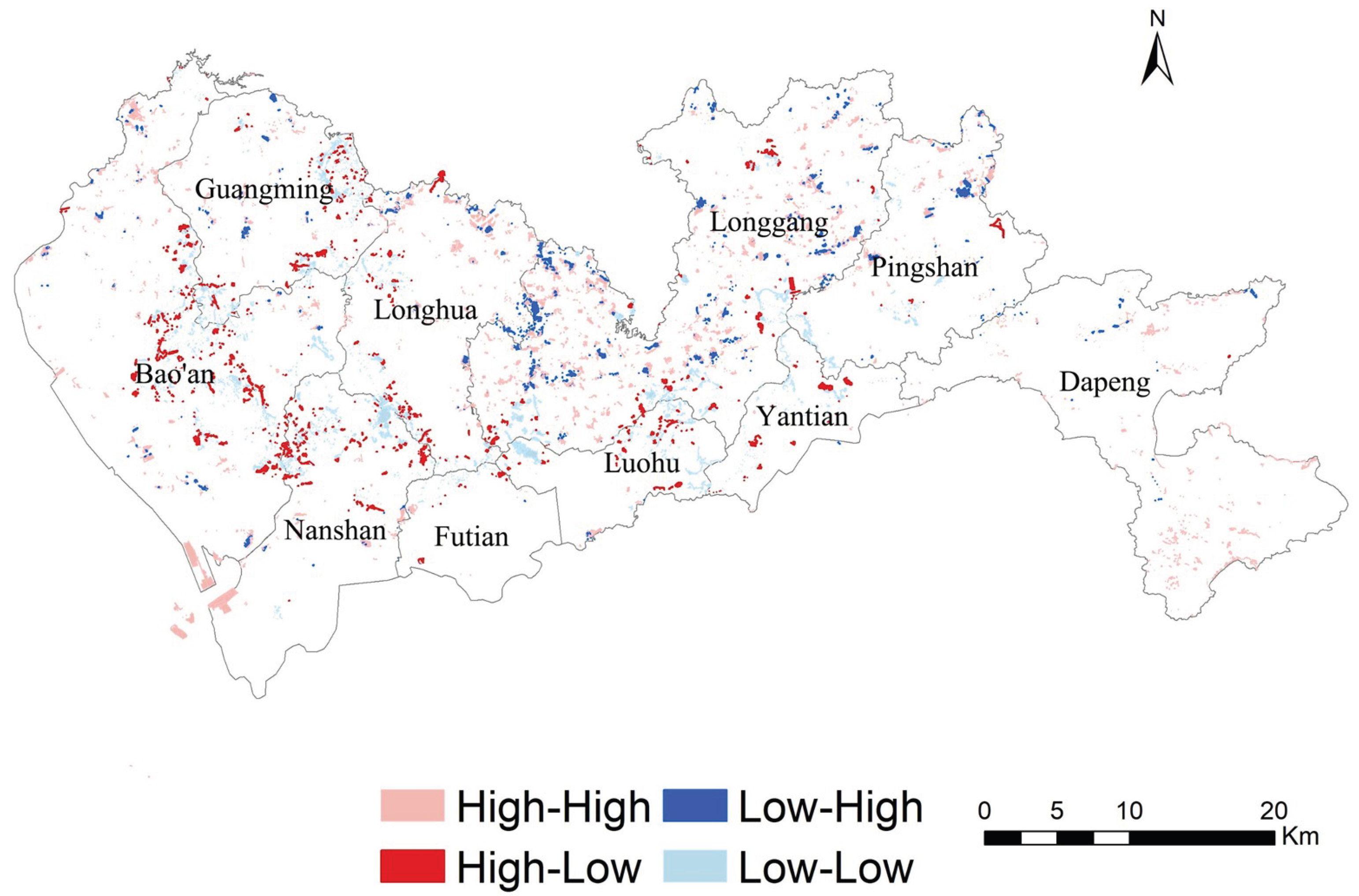

Utilizing local spatial autocorrelation analysis, this study reveals significant spatial clustering characteristics of inefficient existing land in Shenzhen (

), which is crucial for understanding the interrelationships among inefficient land data and regional disparities. The results (

Figure 7) indicate that high–high (H–H) clustering units are uniformly distributed within Longgang District and Nanao Subdistrict (in Dapeng New District). High–low (H–L) and low–low (L–L) heterogeneous clustering zones form gradient transition belts along administrative boundaries, with H–L types concentrated in contiguous hotspot areas such as Buji, Qingshuihe, Minzhi, Xili, and Xixiang subdistricts, as well as the eastern part of Guangming District. Low–high (L–H) clustering units are densely distributed in the transitional zone between Longhua and Longgang Districts, where spatial gradient variations are most pronounced in typical areas such as Fukang, Shuijing, Shangmugu, and Fucheng’ao. This highlights the discontinuity in land use efficiency between urban core areas and peripheral expansion zones.

GIS spatial adjacency analysis further reveals that some inefficient existing land is adjacent to ecological spaces (e.g., woodlands and water bodies), with notable concentrations along the edges of ecological corridors such as Tanglang Mountain and Yinhu Mountain. This spatial coupling phenomenon can be attributed to the restrictive effects of ecological management policies on the development intensity of adjacent areas, leading to a lag in land functional replacement relative to urban expansion demands. From a spatial econometric perspective, the research findings validate the synergistic influence of the dual driving factors—“edge effects” and “ecological constraints”—on the formation of inefficient land.

4. Discussion

This study develops a multidimensional “social–economic–ecological” framework to identify inefficient existing land by integrating multi-source spatiotemporal data. Using entropy weighting and spatial autocorrelation, we find that Shenzhen’s inefficient land in 2019 covers 65.37 km²—about 7% of construction land—mainly clustering in peripheral areas such as Longgang and Bao’an and along ecological corridors, reflecting the city’s transition from rapid expansion to boundary infill under fragmented ownership and ecological constraints. The multi-source fusion approach overcomes the limitations of manual surveys and single-source remote sensing [

21,

46], combining mobility trajectories, POI distributions, and ecological indicators to validate human activity intensity, land-use compatibility, and environmental quality [

14]. Compared with fixed-weight models [

27], entropy-based weighting captures spatial heterogeneity and enhances model adaptability, while the framework can be further extended with machine learning or deep learning to automate detection and reveal latent spatial dependencies, addressing methodological innovation concerns.

The 1 km analytical grid balances computational efficiency and cross-domain comparability but may obscure intra-block variations; higher-resolution grids (e.g., 100 m) or parcel-level units, supported by street-view imagery and semantic segmentation, could refine future identification [

49]. For smaller or data-sparse cities, proxies such as nighttime light intensity provide effective substitutes [

17,

32]. Spatial econometric analysis indicates that nearly one-quarter of inefficient parcels abut ecological control lines, highlighting edge effects and policy inertia. Extending the analytical unit from planar grids to a three-dimensional PSR or DPSIR framework can capture vertical density efficiency and interactions between built and ecological systems, advancing the “renewal unit” concept and enabling multi-level spatial evaluation. Differentiated renewal strategies—coordinated village-based redevelopment, eco-oriented renewal, and transit-oriented intensification or underground space utilization—emerge from these mechanistic insights [

18,

20]. Overall, identifying inefficient land is not merely diagnostic but strategic, providing a transferable paradigm for adaptive, equitable, and resilient urban transformation.

5. Conclusions

Using Shenzhen as a case study, this research constructs a multi-source spatiotemporal framework for identifying and characterizing inefficient existing land. The Entropy Weight–Mean-Standard Deviation model enables automated, city-wide land-use efficiency assessment, offering both methodological innovation and practical guidance for spatial renewal in high-density urban contexts. Results show an “edge aggregation and corridor extension” spatial pattern, shaped by historical development, ecological policies, and urban structure, and validated against field surveys and official land data in typical zones such as Buji-Bantian (Longgang) and Songgang-Shajing (Bao’an).

The study demonstrates the technical advantage of spatiotemporal big data for delineating urban renewal units and informs adaptive planning strategies. Future work should focus on: (1) constructing multi-scale dynamic monitoring integrating satellite nighttime lights and mobile signaling to link city- and plot-level analyses; (2) introducing reinforcement learning models to simulate policy-response mechanisms; and (3) comparative studies across the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area to examine spatial spillovers and support coordinated regional development. With continued digitalization in territorial spatial governance, the proposed framework can evolve into a standard module for urban spatial health assessment, providing a scalable benchmark for optimizing existing land nationwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Minmin Li, Ding Ma, and Ye Zheng; methodology, Wei Zhu and Yebin Chen; formal analysis, Wei Zhu and Yafei Wang; data curation, Wei Zhu; writing—original draft preparation, Minmin Li, Wei Zhu, Yafei Wang, and Shilong Wei; writing—review and editing, Wei Zhu, Minmin Li, Yafei Wang, Ye Zheng, Xiaoming Li, and Shilong Wei; funding acquisition, Minmin Li and Xiaoming Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Urban Land Resources Monitoring and Simulation, Ministry of Natural Resources (KF-2023-08-17), the Open Fund of Information Center of Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China (2025-76-B2461-02), and National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3804800).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Implementation Mechanisms for the Renewal and Renovation of Aging Residential Communities in Urban Areas. Urban Plan. J. 2021, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zheng, W.; Hong, J.; et al. Paths and strategies for sustainable urban renewal at the neighborhood level: A framework for decision-making. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 55, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B. From Physical Expansion to Built-up Area Improvement: Shenzhen Master Plan Transition Forces And Paths. Planner 2013, 29, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Yao, Z.; Yu, J.; et al. Evolution and Transition of Urban Renewal Planning in China: An Analytical Framework of State-Market-Society Relationship. Planner 2024, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, G.; Liu, R.; Peng, Q. A Study on Methods for Identifying Renewal Targets in the Context of National Land Space—A Case Study of Zoucheng. In Proceedings of the China Urban Planning Annual Conference, Wuhan, Hubei, China; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yount, K. R.; Meyer, P. B. Project Scale and Private Sector Environmental Decision Making: Factors Affecting Investments in Small- and Large-Scale Brownfield Projects. Urban Ecosyst. 1999, 3, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glumac, B.; Han, Q.; Schaefer, W.; et al. Negotiation Issues in Forming Public–Private Partnerships for Brownfield Redevelopment: Applying a Game Theoretical Experiment. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Campbell, D. The Determinants of Brownfields Redevelopment in England. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 67, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, T. Major Issues in Indonesia’s Urban Land Development. Land Use Policy 2004, 21, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, S. B.; Al-Mubaiyedh, S. An Assessment Framework for Public Urban Land Management Intervention. Land Use Policy 1999, 16, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T. L. Evaluating Predictors for Brownfield Redevelopment. Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose, A.; Kull, A.; Gauk, M.; et al. Land Use Policy Shocks in the Post-Communist Urban Fringe: A Case Study of Estonia. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, P.; Dhakal, S.; Shrestha, S.; et al. Land Use Land Cover Changes in the Major Cities of Nepal from 1990 to 2020. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 2023, 17, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Pinto, M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Chandrabose, M.; et al. Planning Ecologically Just Cities: A Framework to Assess Ecological Injustice Hotspots for Targeted Urban Design and Planning of Nature-Based Solutions. Urban Policy and Research 2022, 40, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, X. Comparative Study on the Policy Mechanism of Urban Renewal Life Cycle Management. Urban and Rural Construction 2023, 2, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Zeng, P. Evolution of Value-Added Revenue Distribution Mechanism for the Renewal of Stock Industrial Land in Beijing. Urban Planning Journal 2023, 1, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Ye, Q.; Zhao, Y. The Evolutionary Context of Policies, Theories and Practices for the Utilization of Stock Construction Space in China. Economic Geography 2022, 42, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, M.; Li, Q.; et al. A New Model of Existing Land Stock Development: The Research of Land Readjustment Planning and Policy Mechanism in Shenzhen. Urban and Rural Planning 2022, 3, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, Y.; Xia, H.; et al. From Separation to Integration: Policy Reflections and Suggestions on the Development of Existing Land Stock in Shenzhen. Urban Planning Journal 2020, 2, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Sun, Y.; Qin, Q. Integrated Development of the Stock Land and Urban Rail Transit in Shenzhen. Urban Transport 2023, 21, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S. Research on Recognition Methods of Inefficient Construction Land Based on Remote Sensing and Open Data in Baiyun District of Guangzhou City. Master’s Thesis, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Li, C.; Yao, N.; et al. Exploration of Identification Methods for Inefficient Urban Land Use Under the National Spatial Planning Framework: A Case Study of Chengdu’s Downtown Area. Sichuan Environment 2020, 39, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Identification of Low-Utility Land in Urban Centers Using Entropy Weight-BP Neural Network. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Hao, R.; et al. Study on the Identification and Redevelopment Path of Urban Low-Utility Land: Taking the Central City of Hohhot as an Example. Journal of Northeast Normal University (Natural Science Edition) 2023, 55, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Study on the Identification of Inefficient Residential Land in the Ancient City of Suzhou from the Perspective of System Theory. Urban Architecture 2024, 21, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Research on the Identification and Redevelopment Potential of Low-Efficiency Industrial Land in Downtown Areas: A Case Study of Two Districts in Nanjing. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Jiang, L. Research on the Potential Evaluation Method of Stock Land Based on GIS: A Case Study of Gulou District, Nanjing. Urban Housing 2019, 26, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Li, Y. Analysis of the Current Situation and Potential Evaluation of Inefficient Urban Land in Anyang City. Land Resources Informatization 2020, 2, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, M. Research on the Identification and Redevelopment Potential of Inefficient Industrial Land under the Background of Inventory Planning. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. Potential Evaluation of Urban Low-Efficiency Industrial Land Redevelopment Based on Scenario Planning. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Study on Identification and Redevelopment of Inefficient Land in Kaifeng City. Master’s Thesis, Henan University, Kaifeng, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, Z. Research Progress of Urban Land Redevelopment in China. Land and Natural Resources Research 2022, 6, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. Research on Identification and Redevelopment Strategy of Inefficient Land Use in Suichuan County Based on “Pressure-State-Response” Model. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. Research on the Construction of Low-Efficiency Industrial Land Evaluation Index System and Countermeasures: A Case Study of Guangxi Development Zone. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y. Survey Methods and Development Strategies for Inefficient Urban Land. Real Estate World 2024, 18, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, P.; Hao, J.; Zhou, N.; et al. Research on Evaluation of Industrial Land Intensive Use in the Context of New Urbanization: A Case Study in Yizhuang New Town. China Land Science 2014, 28, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S. Identification and Redevelopment of Inefficient Industrial Land in Zhuhai Based on Performance Evaluation. Urban Architectural Space 2023, 30, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liang, R.; Liu, T. Practice and Reflection on the "Mapping and Storage" Work of Inefficient Urban Land Redevelopment in Chengdu. Resources and Human Settlements 2024, 7, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D. Evaluation of Industrial Land and Redevelopment of Inefficient Land in Xinbei District of Changzhou. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Research on Low-Efficiency Land Use Identification of Urban Housing Based on AMM Model Theory Price: A Case of Ulanhot Urban Area. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Research on Inefficient Residential Land Identification Method Based on Multi-Source Data: A Case Study of Wan-quan Urban District, Zhangjiakou City. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Architecture, Zhangjiakou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Chen, B.; Zhang, S. Research Progress and Hotspot Analysis of Stock Planning in China Based on CiteSpace. In Proceedings of the Annual National Urban Planning Conference, Wuhan, China; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Pan, X. Survey and Research on Urban Inefficient Land Redevelopment Based on UAV Tilt Photogrammetry Technology. Jiangxi Build. Mater. 2019, 12, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Application of Aerial Imagery in Urban Land Surveys. Beijing Surv. Map. 2005, 4, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, B.; et al. Study on Extracting Building Density and Floor Area Ratio Based on High Resolution Image. Remote Sens. Technol. Appl. 2007, 3, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Xue, Y.; Xu, C.; et al. Multi-criteria Evaluation on the Inefficiency of Urban Land Use Based on the Major Function Oriented Zone: A Case of Xuzhou City. Land Nat. Resour. Res. 2018, 3, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y. Identification and Optimization Strategy for Inefficient Industrial Land in Urban Built-up Area of Shrinking City: A Case Study of Qiqihar. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Li, H.; Wu, Y. Investigation of Inefficient Land Using 3D Modeling Based on Urban Cadastral Database. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2020, 41, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Measuring Physical Disorder in Urban Street Spaces: A Large-Scale Analysis Using Street View Images and Deep Learning. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2023, 113, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Winter, S.; Khoshelham, K. Forecasting Fine-Grained Sensing Coverage in Opportunistic Vehicular Sensing. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2023, 100, 101939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laport-López, F.; Serrano, E.; Bajo, J.; et al. A Review of Mobile Sensing Systems, Applications, and Opportunities. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2020, 62, 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, X.; Wang, C.; et al. Identification of Inefficient Spaces in Resource-Depleted Cities: A Case Study of Hegang City. Resour. Sci. 2024, 46, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Bi, R.; Chen, L.; et al. Identification and Inquiry of Urban Inefficient Industrial Land Based on Multi-Level Indicator System: A Case Study of Yushe County, Shanxi Province. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2019, 40, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J. Research on Recognition and Synergy Strategies of Inefficient Industrial Land: A Case Study of Dongcheng Park in Jieshou High-Tech Zone, Fuyang, Anhui. Urban Hous. 2019, 26, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Guo, Q.; Chen, Z.; et al. Identification and Redevelopment Strategy of Underused Urban Land in Underdeveloped Counties Using System Theory. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; et al. The Spatial Reconstruction of Inefficient Land Redevelopment under Ecological-Economic Competition and Cooperation: A Case Study of Urban District in Zhanjiang. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Wang, C.; Gao, L. The Urban Inefficient Industrial Land Evaluation Based on the Principle of Land-Saving: Taking Hailing District of Taizhou, Jiangsu Province as an Example. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Current Identification and Redevelopment Practices of Inefficient Land. China Bidding 2024, 8, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenzhen Stock Residential Land Information (as of March 31, 2024): Location Map of Shenzhen Stock Residential Land. Available online: https://pnr.sz.gov.cn/xxgk/ztzl/rdzt/clzzyd/content/post_11251635.html (accessed on April 19, 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).