1. Introduction

Quality assurance is critical in aluminum die casting because internal porosity—such as gas and shrinkage pores—can compromise structural integrity and significantly shorten component lifetime. X-ray inspection is therefore a cornerstone of non-destructive testing (NDT), enabling the identification of defective parts before machining or assembly, thereby preventing costly rework, recalls, and downstream failures.

Currently, inspection remains largely manual. Visual judgment is highly dependent on operator experience and fatigue, making subtle porosity patterns easy to overlook. This variability leads to inconsistent decision-making, increased scrap rates, and higher production costs. Recent advances in deep learning (DL) offer a promising solution: convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and modern one-stage object detectors achieve high accuracy in industrial imaging with low inference latency. State-of-the-art studies report detection accuracies of up to 95.9% on specific datasets, with multiple works demonstrating that DL-based approaches outperform classical image processing methods in complex defect scenarios [

3,

4,

5].

Economic pressures further underscore the need for robust and efficient inspection. The global market for X-ray inspection systems is expanding rapidly, while energy prices remain high for German industry—amplifying the financial and environmental cost of scrap in energy-intensive die casting processes. Reducing false negatives and rework not only improves profitability but also contributes directly to sustainability goals. For context, the market for X-ray inspection systems is estimated at USD 2.50 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 3.85 billion by 2032 [

6]; in Germany, electricity prices for industrial consumers averaged approximately 0.178 €/kWh in 2025 [

10].

This study develops and evaluates a deep learning-based object detection system for automated porosity detection in X-ray images of aluminum die-cast components. The solution is specifically tailored to project requirements at Hengst SE, Germany: real-time processing (< 2 s per image) on a standard industrial PC without a discrete GPU, and seamless integration into the existing X-ray inspection workflow. The approach is validated in a real-world industrial case study under actual production conditions, and the methodology and results are detailed in

Section 2 and

Section 3, respectively.

This study addresses the following research questions:

(RQ1) Can a one-stage deep learning detector meet real-time constraints (< 2 s) on standard industrial hardware without a discrete GPU?

(RQ2) How does input resolution affect detection accuracy for small porosity defects in aluminum die-cast X-ray images?

(RQ3) Does model granularity (position-specific vs. part-level) impact detection performance and generalization in real-world production conditions?

Based on these questions, we formulate the following hypotheses:

(H1) A one-stage detector (e.g., YOLOv5) will satisfy real-time constraints, while a two-stage detector (e.g., Faster R-CNN) will not.

(H2) Preserving native image resolution (2016 × 2016) will significantly improve detection accuracy compared to downscaling.

(H3) Position-specific models will outperform a Part-Level model in localization accuracy, but the Part-Level model may generalize better across inspection positions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 details the industrial context, dataset curation, and methodological framework, including model preselection, hyperparameter optimization, and evaluation protocol.

Section 3 presents the quantitative and qualitative results, including runtime performance, F1-scores, and live test outcomes.

Section 4 discusses the implications of the findings for industrial practice, limitations, and future work. Finally,

Section 5 concludes with practical recommendations for deploying AI in industrial inspection workflows.

2. Methodology: A Four-Stage Framework for Deployable Defect Detection

2.1. Industrial Context and Equipment

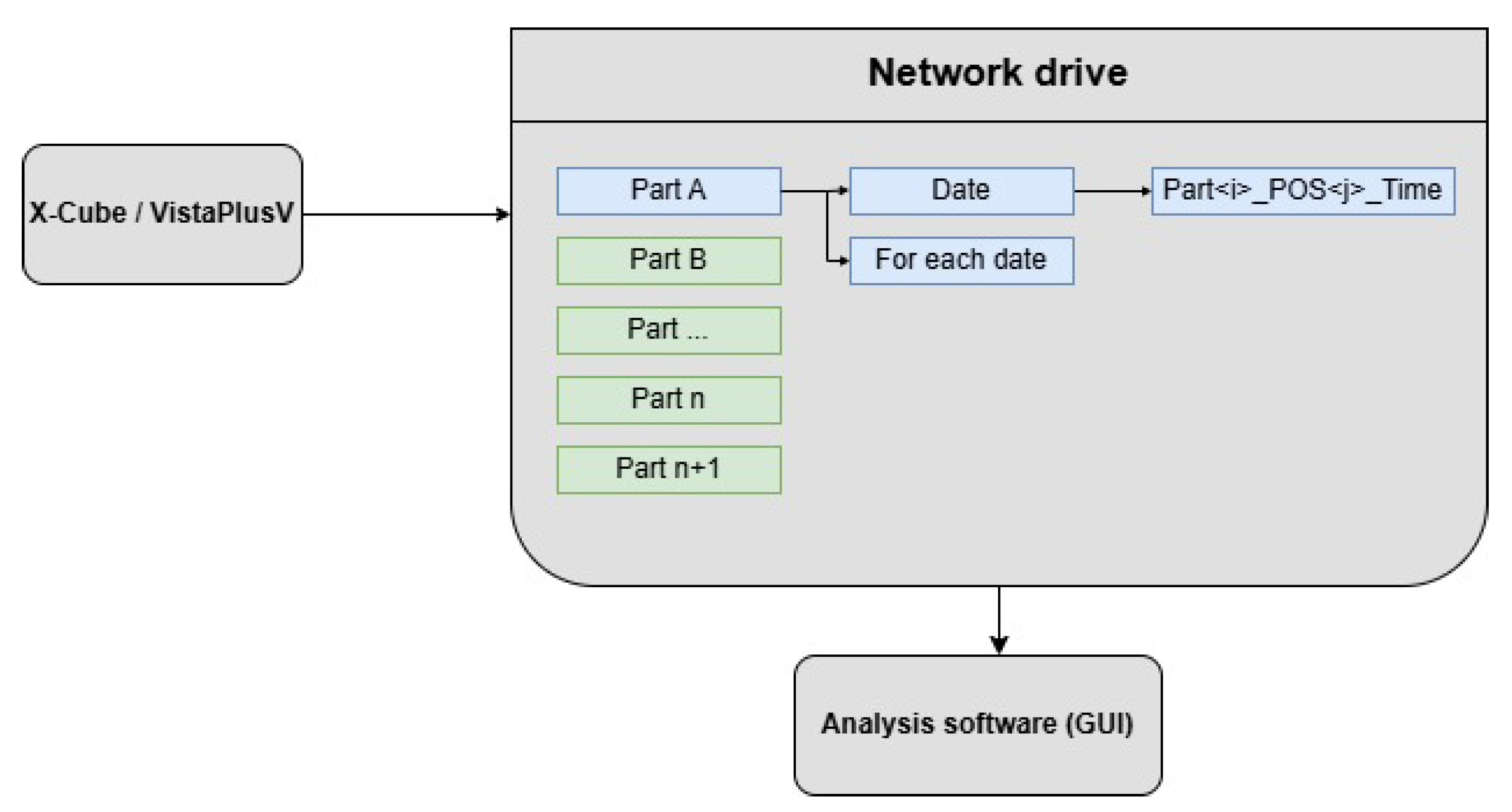

The study was conducted in a production X-ray inspection cell at Hengst SE (Nordwalde, Germany). The system comprises an X-Cube Compact X-ray cabinet (maximum tube voltage 225 kV) and the vendor’s inspection software VistaPlusV for image acquisition and operator viewing. Components are mounted in a dedicated production clamping fixture (workholding fixture) that enforces a highly repeatable pose for series inspection. Each part is examined according to predefined routines with a fixed number of inspection positions (views). For every unit under test, the same set of positions is acquired in the same order; images are 2D radiographs (no CT) captured using site-standard exposure recipes.

2.2. Dataset Curation and Annotation

We collected production radiographs for two aluminum die-cast components, hereafter

Part A and

Part B. Part A is inspected in nine predefined positions (POS1–POS9) with 300 images per position, totaling 2,700 images and 12,960 porosity annotations. Part B is inspected in eighteen positions (POS1–POS18) with 150 images per position, totaling 2,700 images and 27,443 annotations. Images were acquired during regular shifts and exported by

VistaPlusV to a network share using a minimal filename scheme

PartA_POS<k> or

PartB_POS<k>. Invalid images (e.g., misclamping, severe rotation/vertical offset, non-representative machining states) were removed before labeling. Porosity defects were annotated as

bounding boxes (single class

porosity) using LabelImg [

9]; labels store normalized coordinates

per image.

For each part and position, the dataset was split into

70% training and

30% validation with no separate test set; the fixed split was reused across all experiments without leakage.

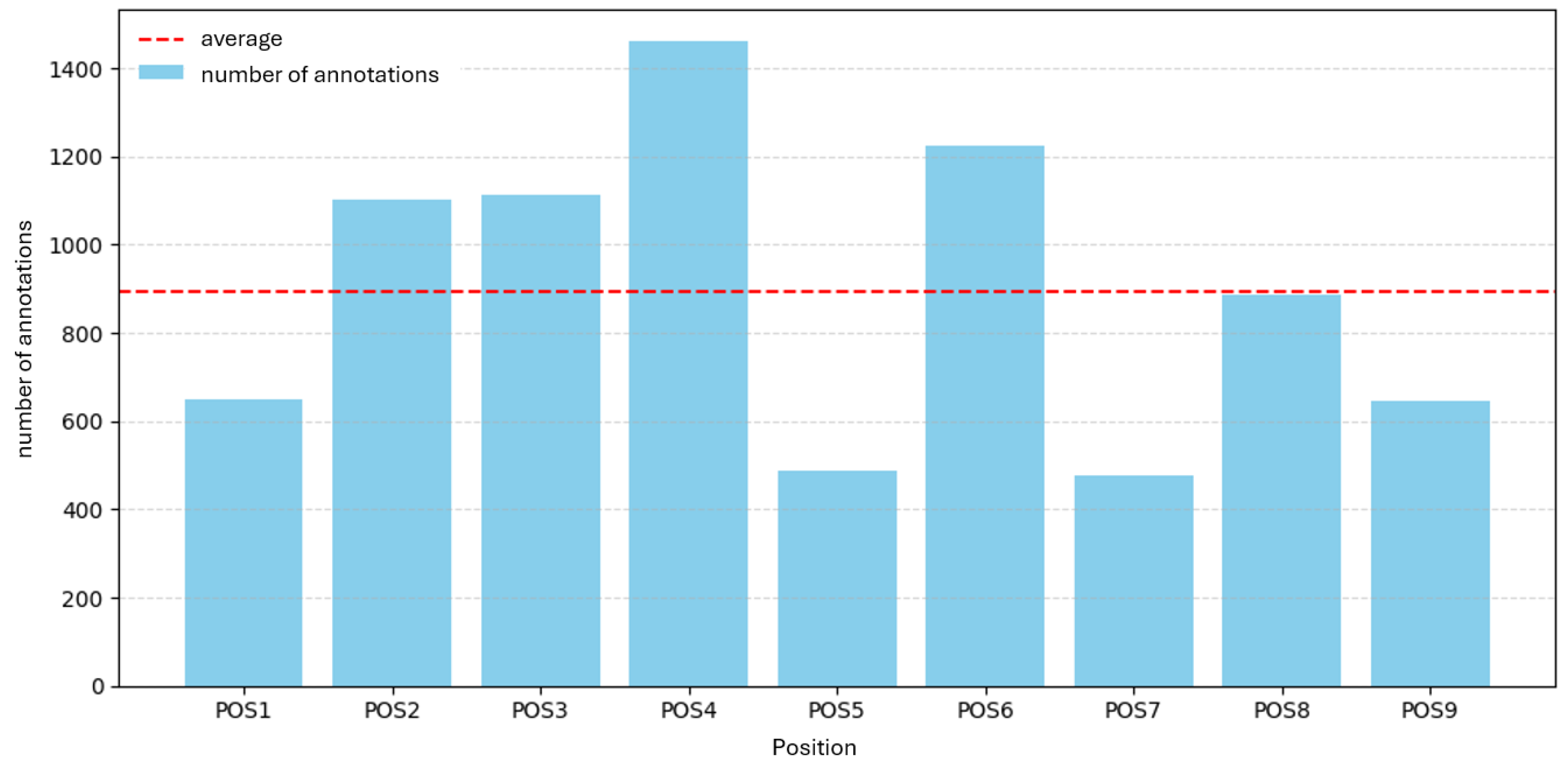

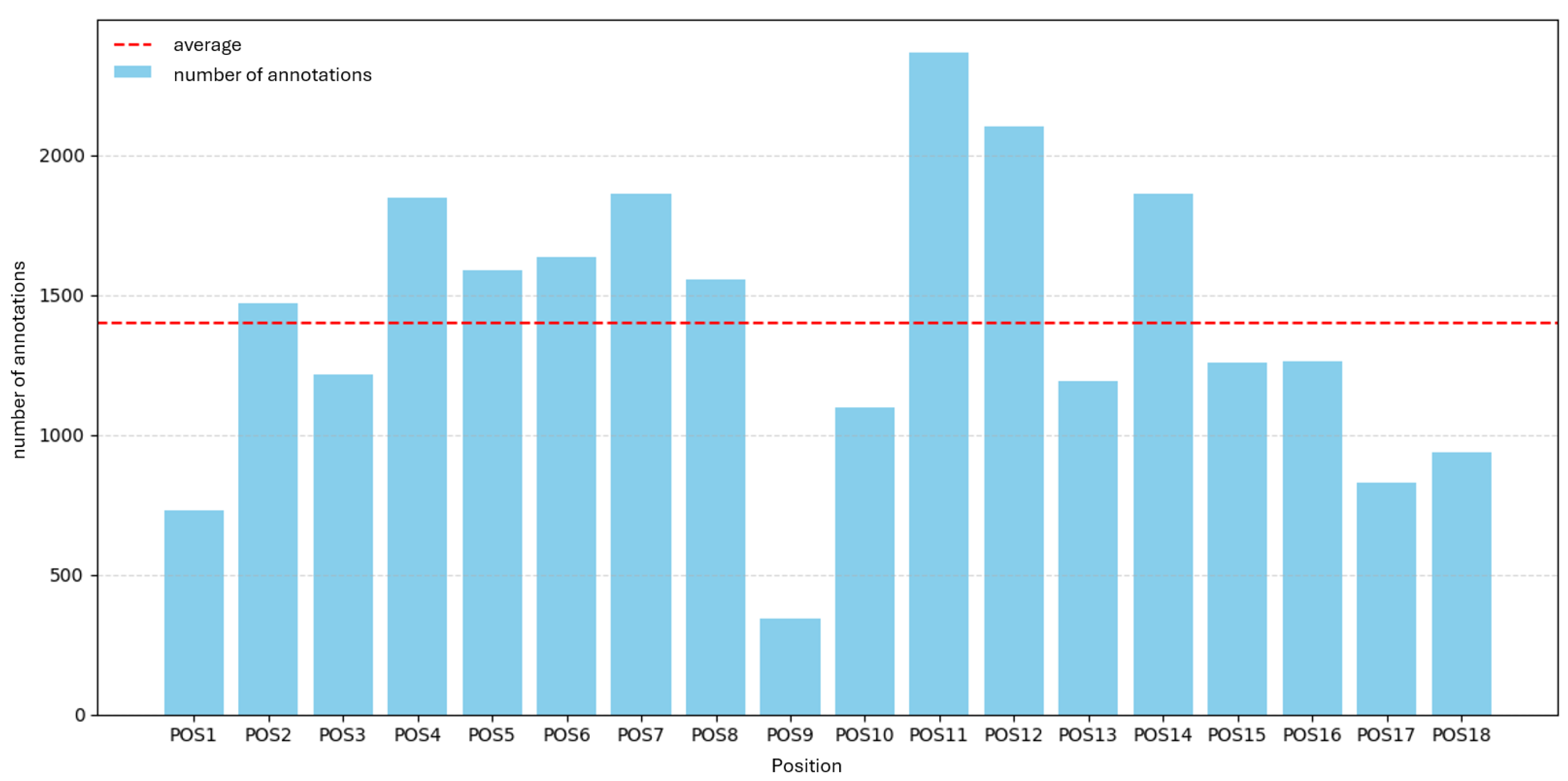

Table 1 summarizes the aggregate image and annotation counts per component;

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 visualize the distribution of annotations per inspection position for Part A and Part B, respectively, with the

mean indicated as a dashed reference line.

As shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, annotation counts vary strongly across inspection positions. For

Part A (9 positions), counts range from

477 (POS5) to

1,460 (POS4), with a mean of

894 and a total of

12,960 annotations. For

Part B (18 positions), counts range from

346 (POS9) to

2,367 (POS11), with a mean of

1,398 and a total of

27,443 annotations.

2.3. Model Preselection and CPU Runtime Benchmark

To identify a detector family that satisfies the project-specific real-time constraint ( s per image on a CPU-only industrial PC), we conducted a runtime-only preselection comparing a modern one-stage DL detector (YOLOv5) with a two-stage baseline (Faster R-CNN). We used publicly available pretrained weights without additional training or fine-tuning and evaluated end-to-end latency per image. Accuracy was intentionally not compared at this stage; accuracy-focused experiments follow later.

2.3.1. Rationale for Candidate Selection

YOLOv5 and Faster R-CNN represent the two dominant paradigms in object detection (one-stage vs. two-stage) and are widely proven across diverse applications [

1,

2]. This pairing aligns with deployment constraints: Windows-based

CPU-only execution on shop-floor hardware, strict endpoint security, limited admin rights, and packaging as a self-contained executable. YOLOv5 offers low-latency inference and mature export/packaging paths; Faster R-CNN provides a strong accuracy-oriented baseline for runtime comparison. Heavier alternatives (e.g., transformer/anchor-free stacks) were out of scope for the runtime preselection.

2.3.2. Execution Environment and Packaging

Benchmarks ran on the target industrial workstation (CPU-only); inference was wrapped in a lightweight PyQt UI and packaged with PyInstaller as a

single-file executable (

onefile) to mirror deployment conditions (deterministic dependencies; endpoint security active; no Python environment management). As the benchmark target, the shop-floor hardware and OS are listed in

Table 2.

2.3.3. Benchmark Protocol

We measured wall-clock latency per image (batch size 1) on CPU, including model load, preprocessing, inference, postprocessing (NMS), and overlay rendering. To account for warm-up, the first run was recorded separately; subsequent runs were repeated

times and summarized by mean, minimum, and maximum. Radiographs were 8-bit grayscale at native resolution 2016×2016, resized per framework to a fixed model input of 640×640 (YOLOv5: square resize; Faster R-CNN: shorter-side resize to 640 with aspect preserved). We report the resulting CPU latencies in

Table 3.

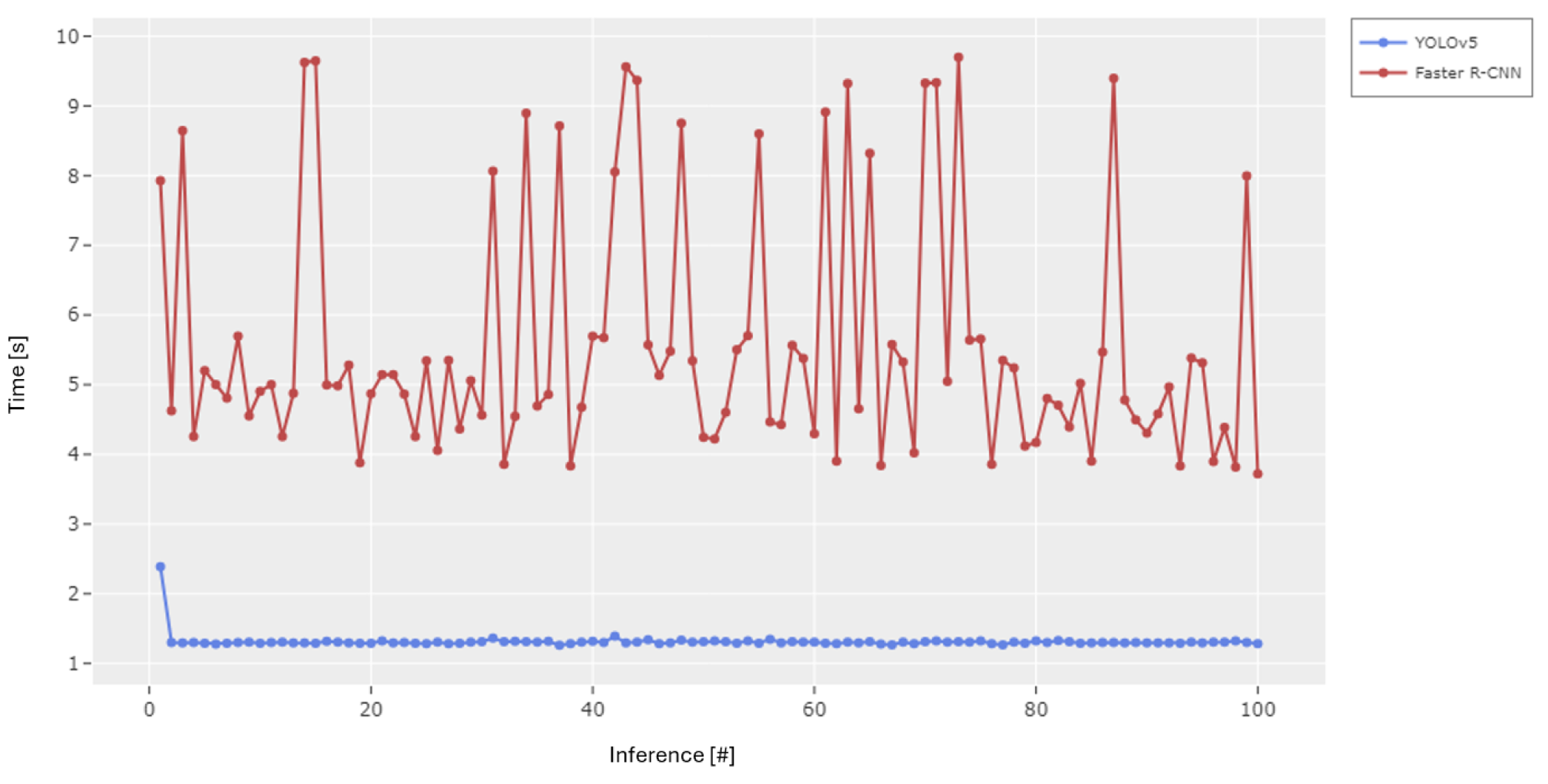

2.3.4. Results and Decision

YOLOv5 met the

s CPU target after warm-up. Its minimum latency was

1.261 s, mean

1.33 s, and maximum

2.39 s, where the maximum corresponds to the first, initialization run. Faster R-CNN failed the target with higher variability: minimum

3.718 s, mean

5.59 s, and maximum

9.698 s. We therefore selected the one-stage family for full training and tuning.

Figure 3.

CPU-only inference latency on the industrial PC over 100 runs (batch size 1). The first-run warm-up outlier is visible for YOLOv5; subsequent runs stabilize well below the 2 s target.

Figure 3.

CPU-only inference latency on the industrial PC over 100 runs (batch size 1). The first-run warm-up outlier is visible for YOLOv5; subsequent runs stabilize well below the 2 s target.

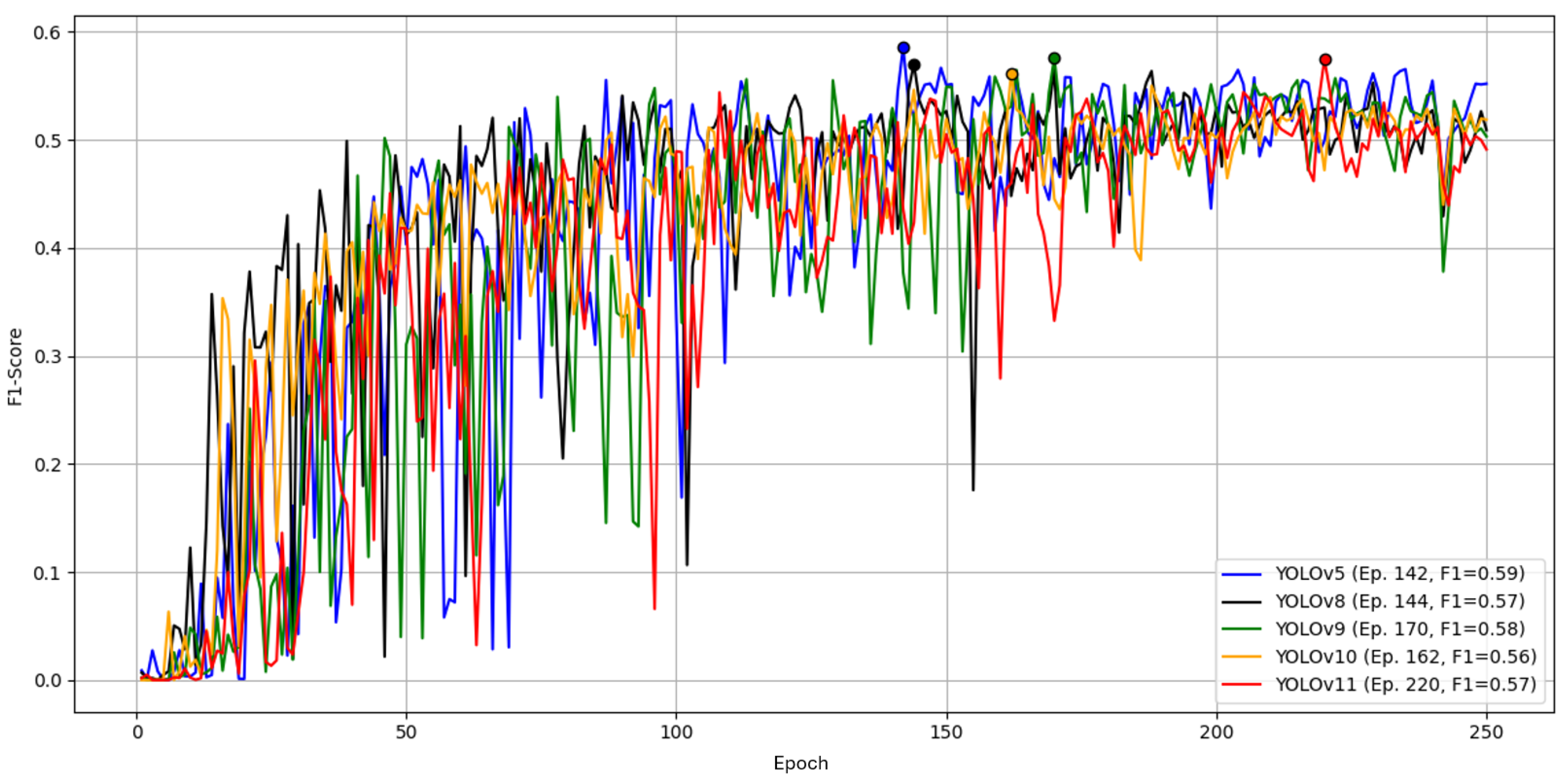

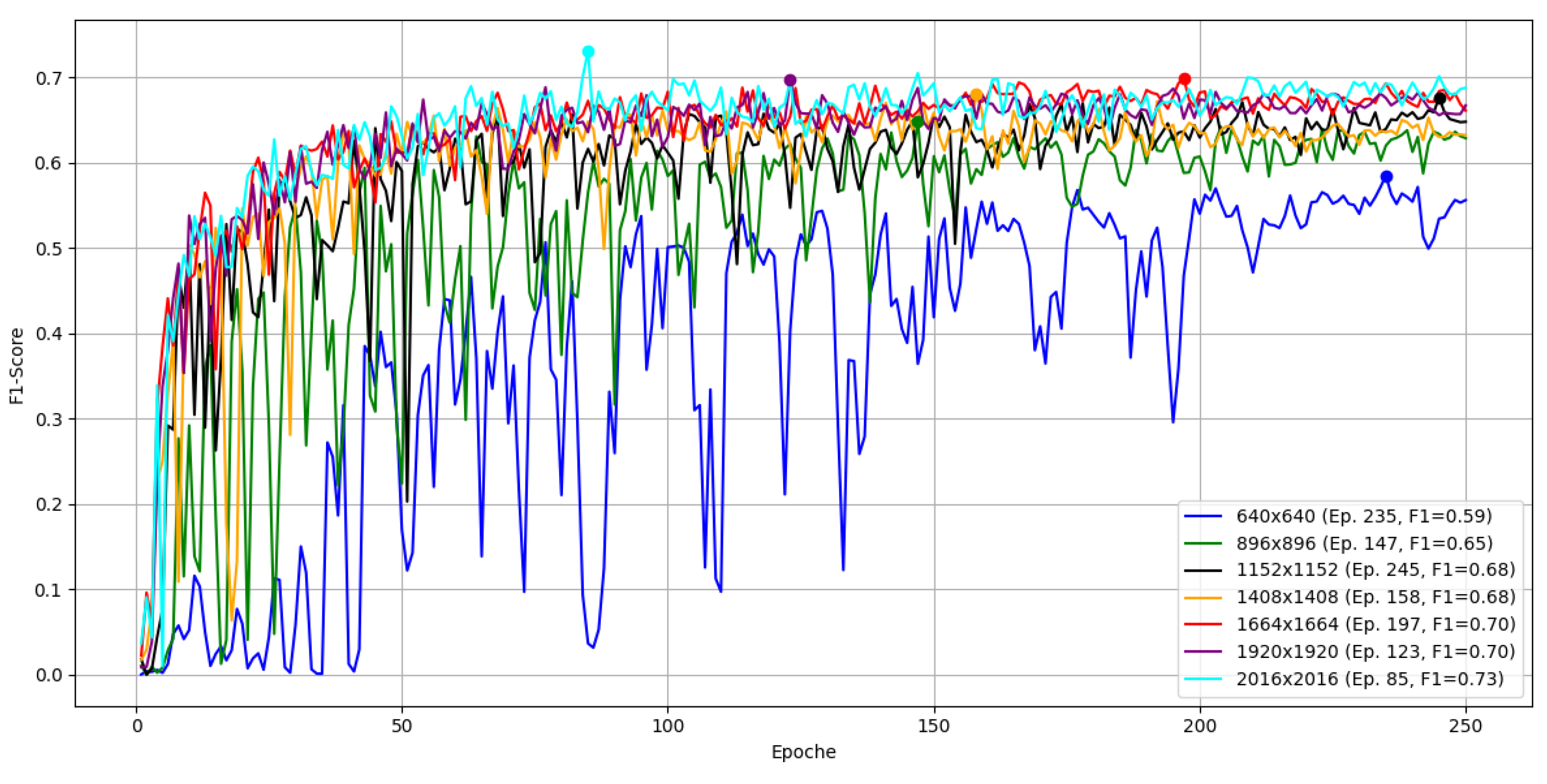

2.4. Baseline Benchmark for YOLO Variant Selection

We compared YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, and YOLOv11 under identical inputs using the Ultralytics framework. Specifically, we used the dataset of Part A, position 2, with 300 images and 1,100 annotations (single class). Training ran for 250 epochs with default hyperparameters, and performance was measured by the F1-Score.

Figure 4.

Comparison of YOLO architectures over 250 epochs by F1 score on the reference dataset. Early oscillations up to ∼100 epochs diminish over time.

Figure 4.

Comparison of YOLO architectures over 250 epochs by F1 score on the reference dataset. Early oscillations up to ∼100 epochs diminish over time.

2.4.1. Results

YOLOv5 achieved the highest peak F1 with at epoch 142, followed by YOLOv9 with at epoch 170. YOLOv8 and YOLOv11 both reached . These differences are small.

As shown in

Table 4, YOLOv9 had the shortest total time (18.60 min) but reached its best F1 later (12.45 min). YOLOv5 reached its best F1 fastest (10.20 min) with a similar total time, while YOLOv10 was markedly slower without better F1. Given near-equal peak F1 but faster convergence to the best F1, and low total training time, we select

YOLOv5 for subsequent experiments on Parts A and B.

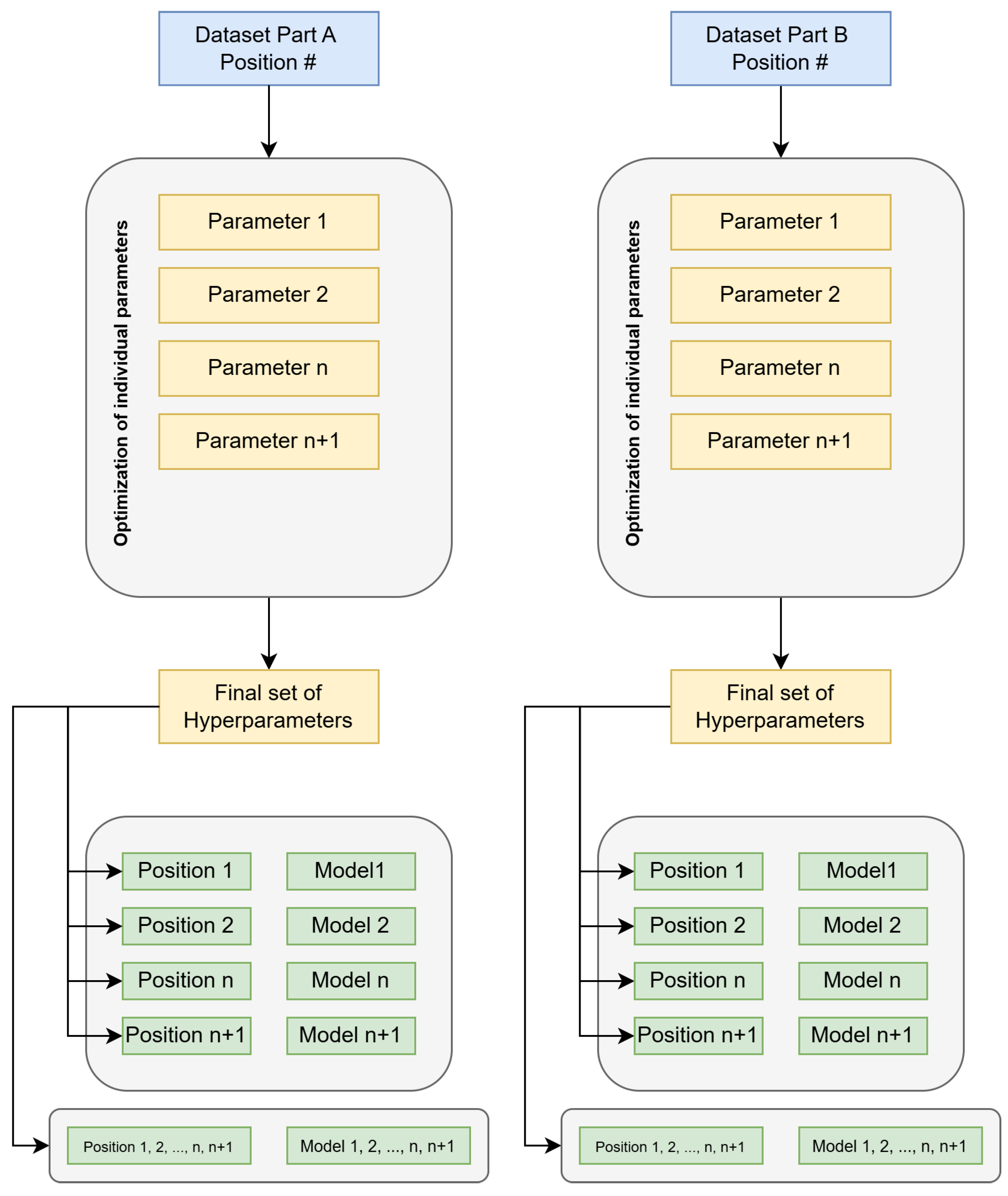

2.5. Hyperparameter Optimization Strategy

Due to long training times and large data volume, hyperparameter optimization was restricted to one position per part and limited to deterministic parameters only to ensure reproducibility, excluding randomness-dependent settings (e.g., initializations, dropout). We optimized on

Part A (H183H) position 1 and

Part B (H530H) position 6. For each position, we applied a sequential, one-at-a-time procedure: vary a single hyperparameter while keeping others fixed at a baseline, select the best value after several runs, fix it, then proceed to the next hyperparameter until all targeted parameters were adjusted. The resulting per-part parameter set was then transferred to the remaining positions of the same part. In addition, we trained a joint model on a combined dataset of all positions using the same optimal hyperparameters and compared its performance with the average of the position-specific models. The overall procedure is summarized in

Figure 5.

2.6. Hyperparameter Optimization on Part A

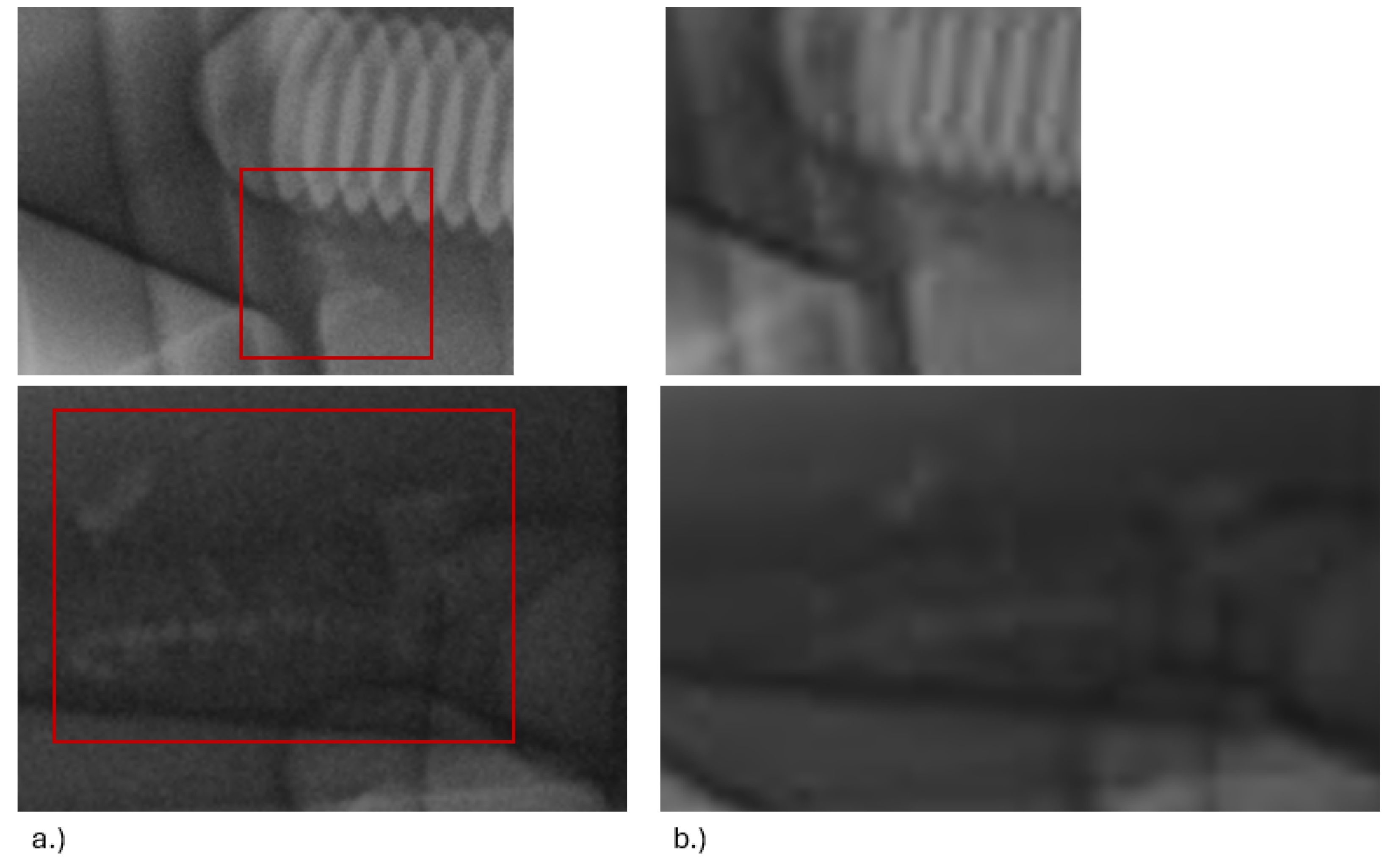

This section presents an example optimization of YOLOv5 hyperparameters. We start from the YOLOv5 default settings as provided by Ultralytics v8.3.94 (full list in digital Appendix D). By default, training images are resized to

pixels. This strongly reduces input size but may hide small casting defects at very high native resolution (

).

Figure 6 shows identical defects at native resolution and after downscaling, illustrating the loss of fine detail at

.

When salient details disappear in the inputs but remain referenced in the ground truth, the model is forced to learn from visually ambiguous or invisible cues. Downscaling may eliminate fine defect structures that remain visible only at native resolution and can induce unstable gradients during training [

3]. This behavior explains the sensitivity of recall to input size.

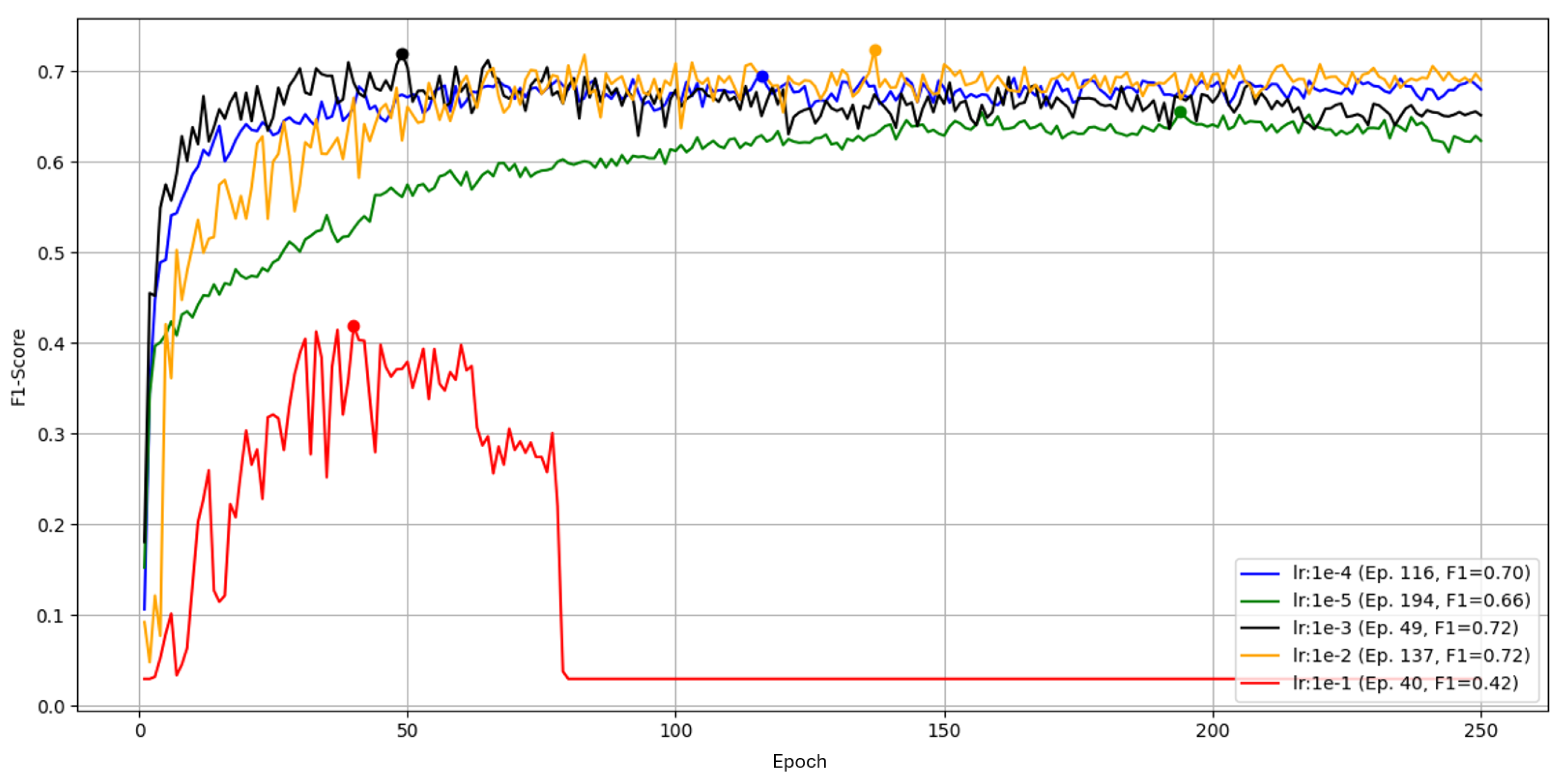

Learning Rate

We next varied the learning rate while keeping all other settings fixed and the resolution increased from 640 to 2016. The default is

. The sweep covered

to

.

Figure 8.

Learning -rate sweep for YOLOv5 over 250 epochs on Part A, position 1, measured by F1.

Figure 8.

Learning -rate sweep for YOLOv5 over 250 epochs on Part A, position 1, measured by F1.

The largest rate, , peaks at F1 then diverges after epoch 83 (F1 drops to 0/NaN). The default reaches a transient peak of at epoch 137 but is unstable and otherwise plateaus near . A rate of yields the best balance with a stable peak of by epoch 49; behaves similarly but tops out at . The smallest rate, , is stable but underfits and remains . We therefore proceed with for this configuration.

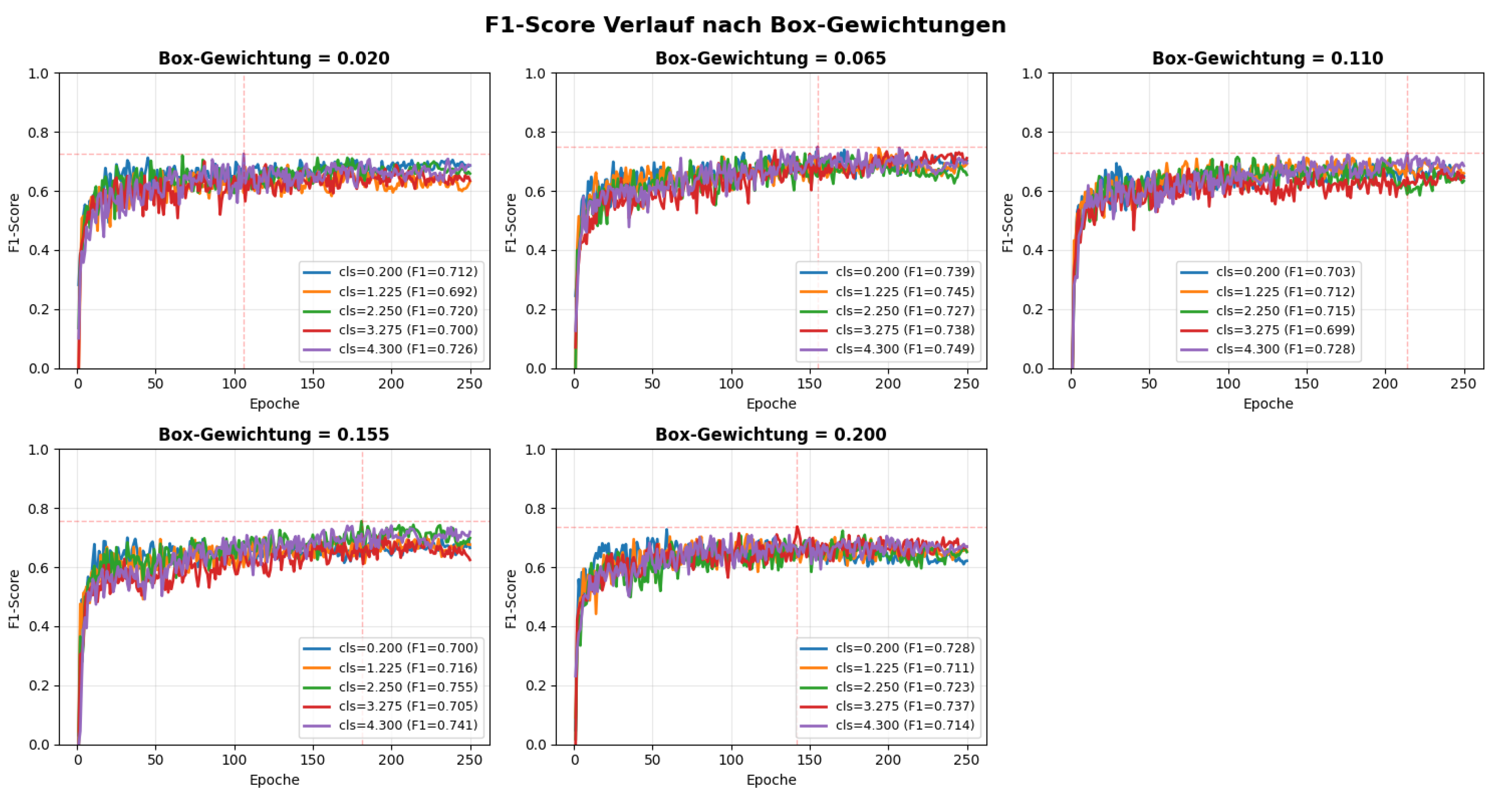

Loss Weights (box and class)

We tuned the loss-component gains for box and class. Five evenly spaced values were used per axis, producing

runs (

Table 6) and the corresponding F1 curves in

Figure 9.

Performance varies noticeably with the weighting. The global best within this grid is box=0.155 with class=2.250 (F1

at epoch 181), closely followed by box=0.065 with class=4.300 (F1

). With low box loss (

), higher class loss helps; with high box loss (

), F1 declines. Very low class loss (

) underperforms (F1

, stagnating by epoch 59). The top configurations are summarized in

Table 7.

Summary for Part A

Relative to the baseline F1 of at , increasing the input to raised F1 to . Learning-rate tuning showed that extreme values are harmful or unstable, while provided the best stability-speed trade-off for this setup. Finally, adjusting box/class loss gains increased F1 further to .

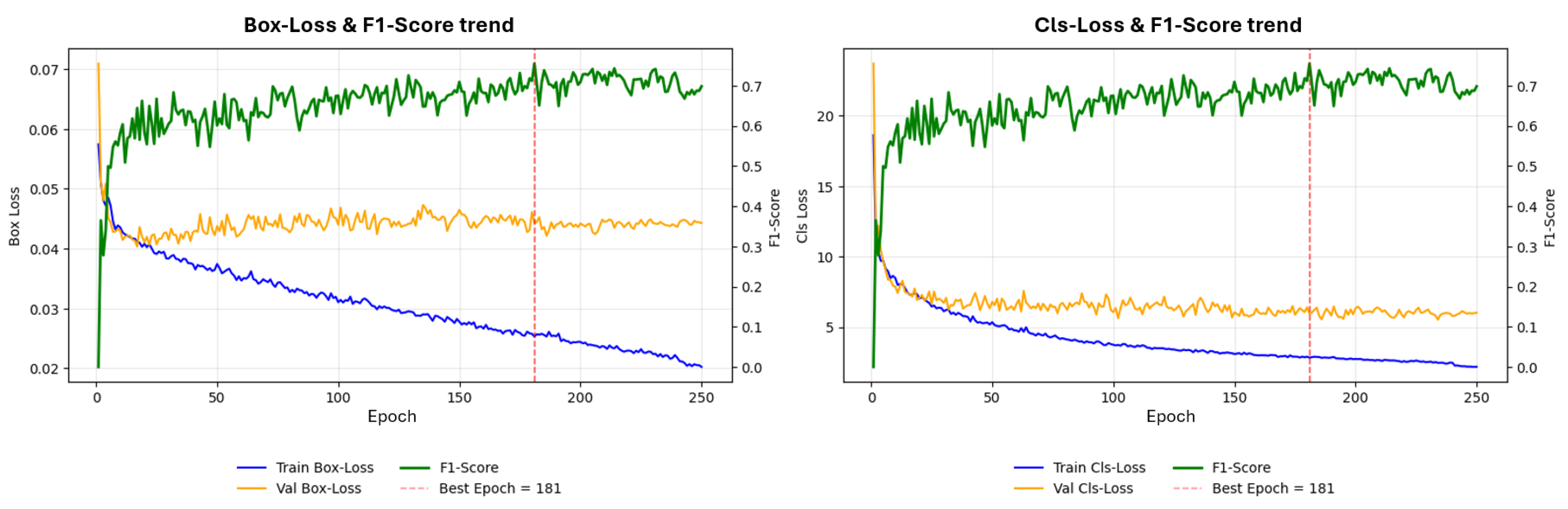

To assess overfitting,

Figure 10 plots training and validation losses; the vertical line marks the epoch of peak F1. Training losses decrease steadily, but the validation box loss rises after epoch 45, indicating the onset of overfitting despite a continued slight decrease of validation class loss. This supports monitoring beyond a single F1 peak.

The final setting used in subsequent runs is listed in

Table 8.

2.6.1. Results on Part A

Using the settings from

Table 8, we trained one model per position and one joint model on all positions.

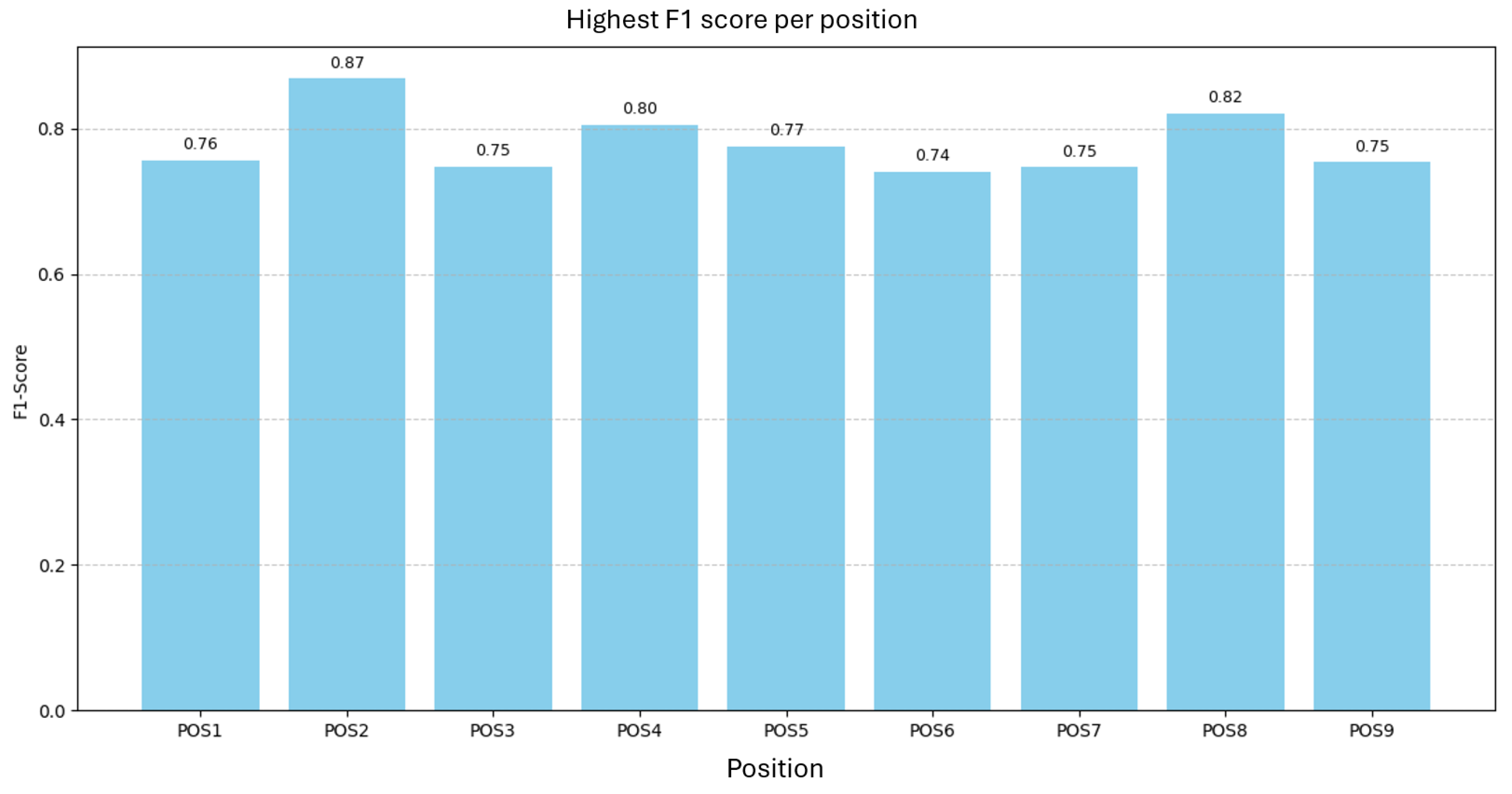

Figure 11 shows the best F1 per position; scores range from

(POS6) to

(POS2), mean

with a span of

.

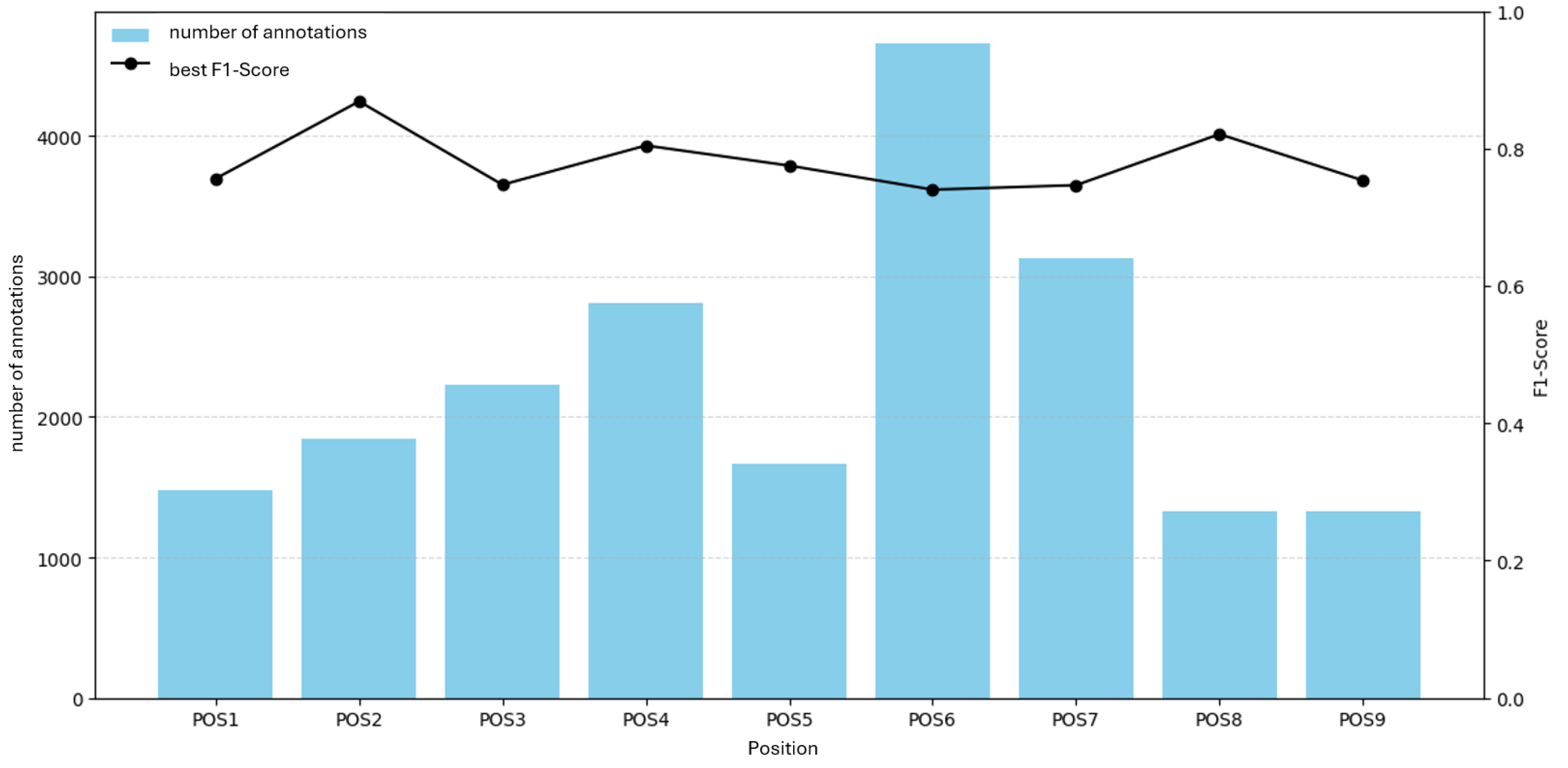

Figure 12 relates F1 to the number of annotations per position. No linear relationship is evident; positions with more annotations do not necessarily achieve higher F1, and the position with the most annotations shows the lowest F1.

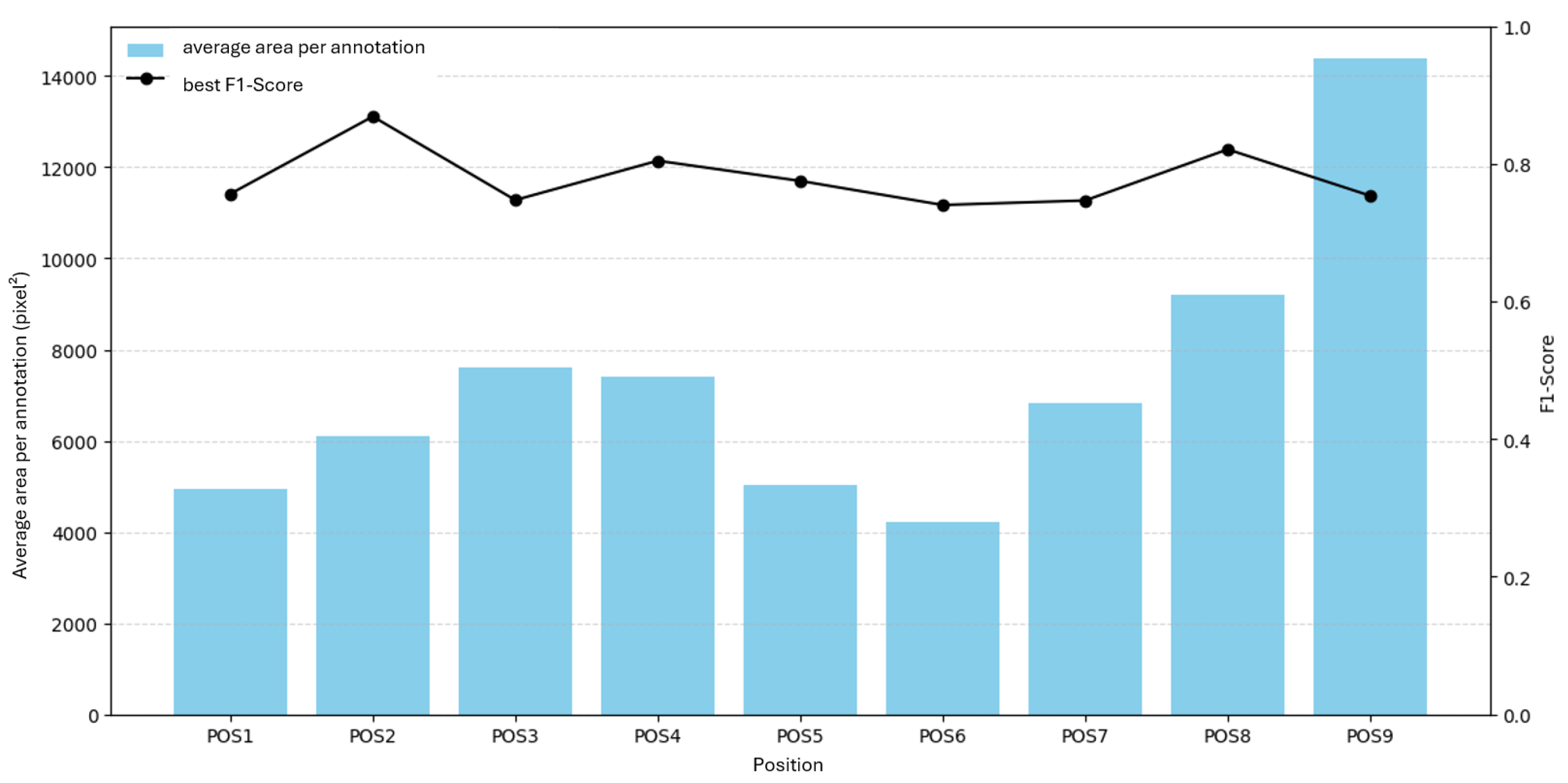

Figure 13 relates F1 to average annotation area. Again, no clear relationship appears; F1 varies despite increasing average area for several positions. Thus, neither count nor area alone explains the F1 variability.

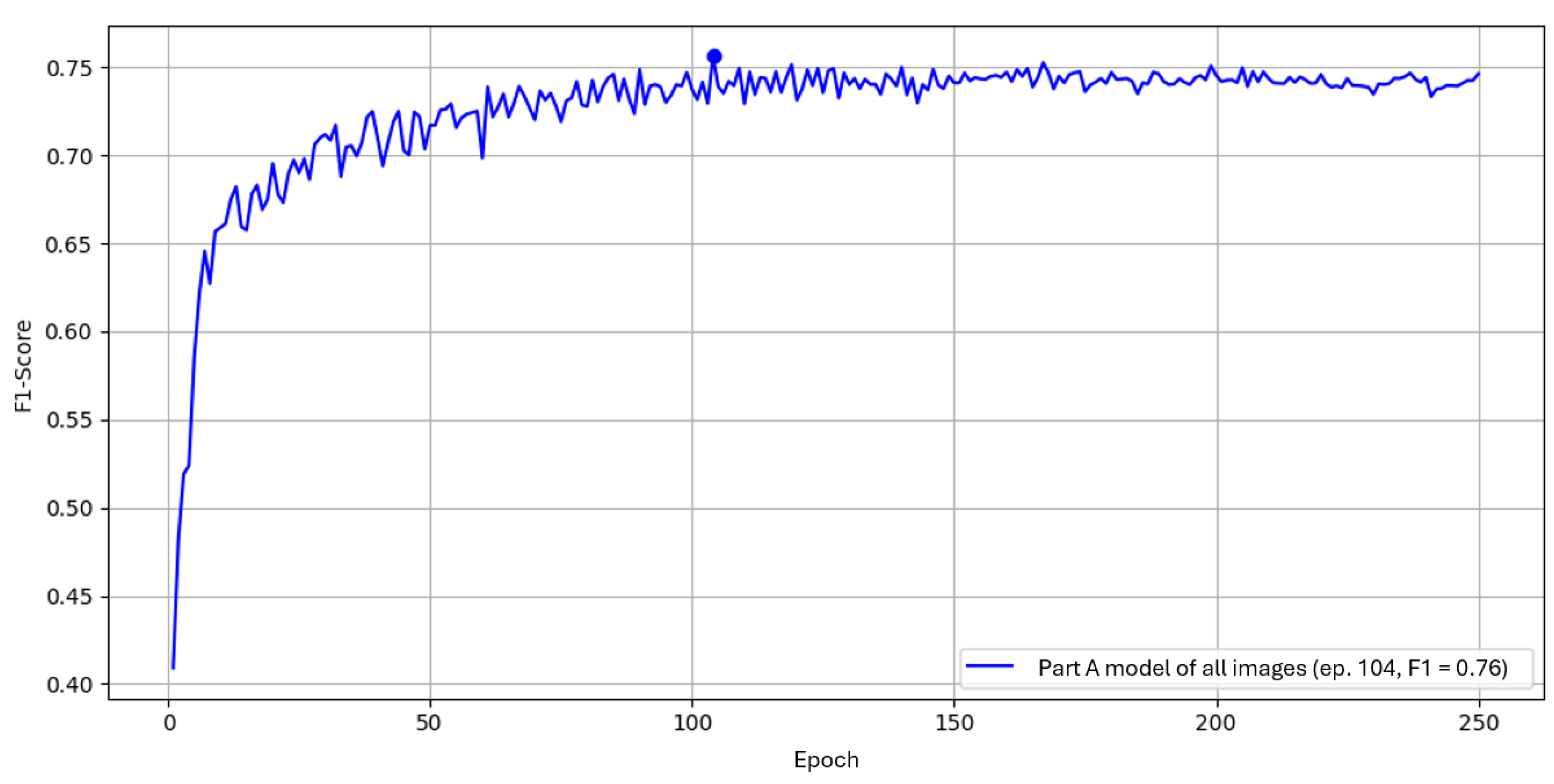

The joint model trained on all positions reaches a maximum F1 of

, which is

below the mean of the nine position-specific models (

Figure 14). While the joint model sees more variability during training, it may generalize better to unseen defect patterns. A further fine-tuning in the joint setting could improve results, but was not feasible here due to training time constraints.

In the practical evaluation, we compare both approaches qualitatively on example images.

2.7. Hyperparameter Optimization on Part B

The optimization approach used for Part A was transferred to

Part B (H530H). The dataset used was

position 6 with

150 images and

∼1700 annotations. We first varied the input resolution; results are shown in

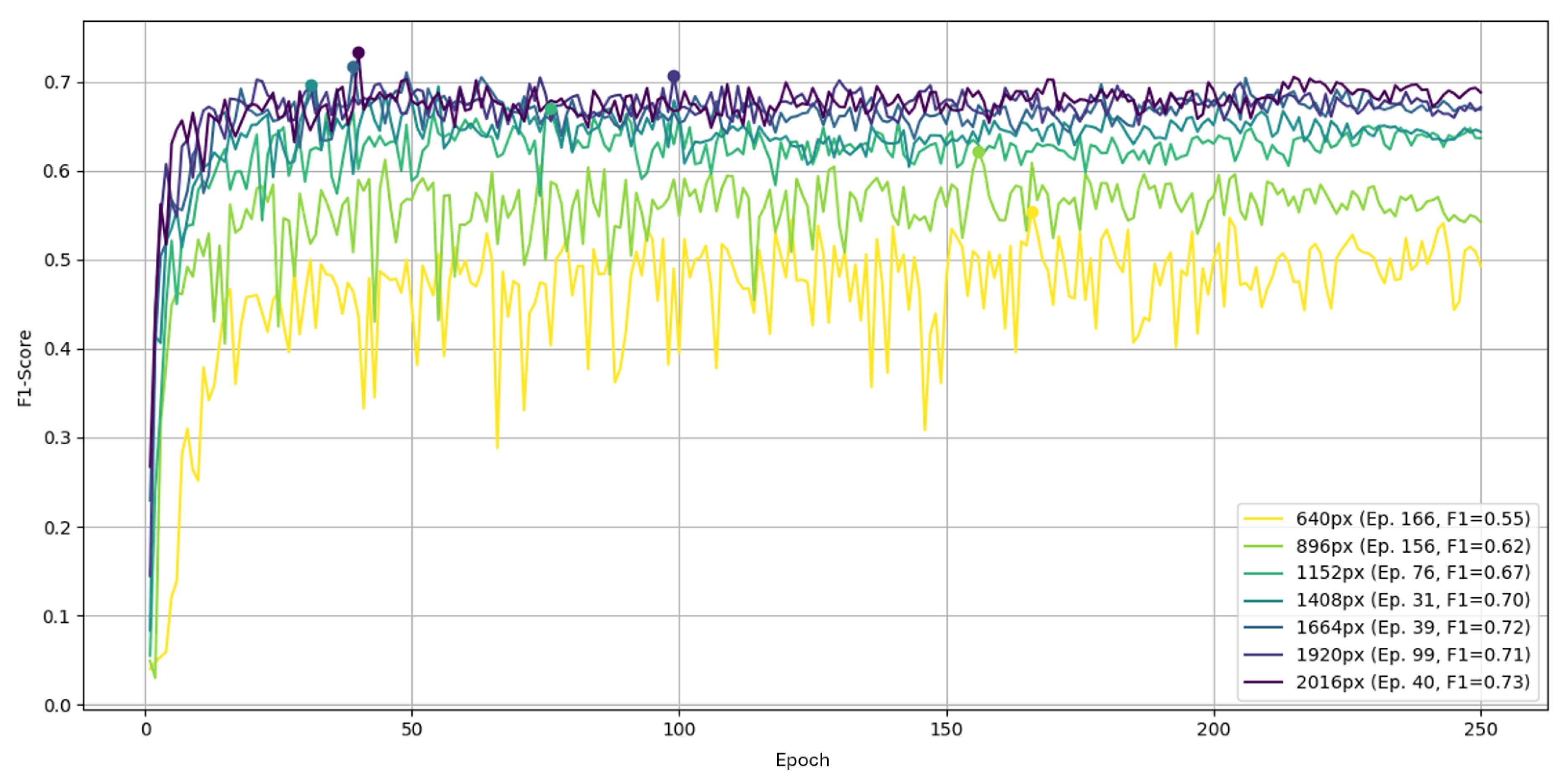

Figure 15.

As with Part A, the native resolution yields the highest F1, ranging from 0.55 up to 0.73. At the default the curves fluctuate less than in Part A; differences appear mainly as a vertical shift relative to higher resolutions.

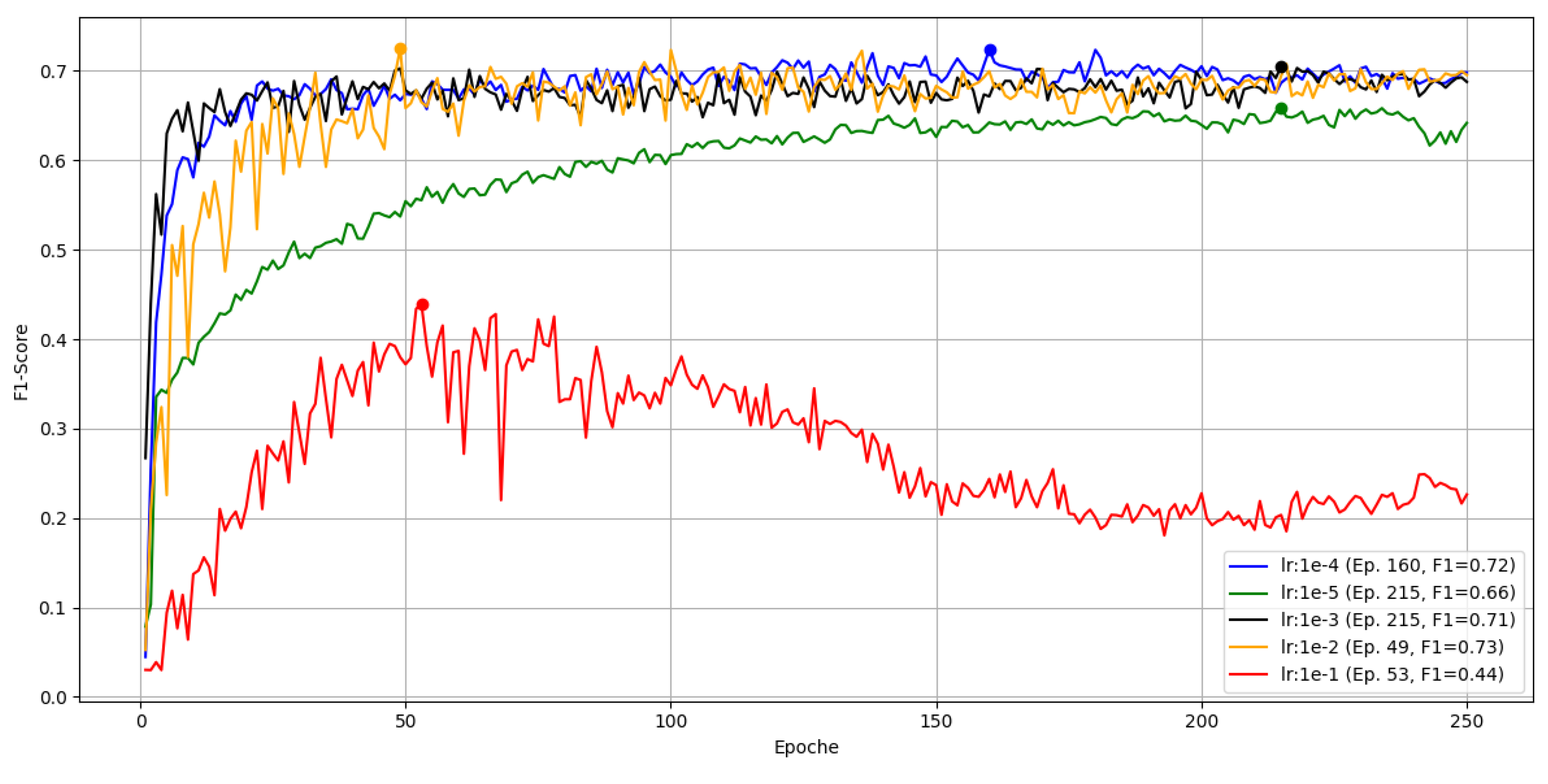

Learning Rate

With the input fixed at

, the learning rate was swept over the same interval as in Part A.

Figure 16.

Learning-rate sweep for YOLOv5 over 250 epochs on Part B, position 6, measured by F1.

Figure 16.

Learning-rate sweep for YOLOv5 over 250 epochs on Part B, position 6, measured by F1.

The largest rate gives the worst convergence. It does not crash but declines after a peak near epoch 53. The smallest rate behaves like in Part A and appears stuck in a local minimum. The remaining three rates are similar; the best peak F1 of 0.73 occurs with around epoch 49.

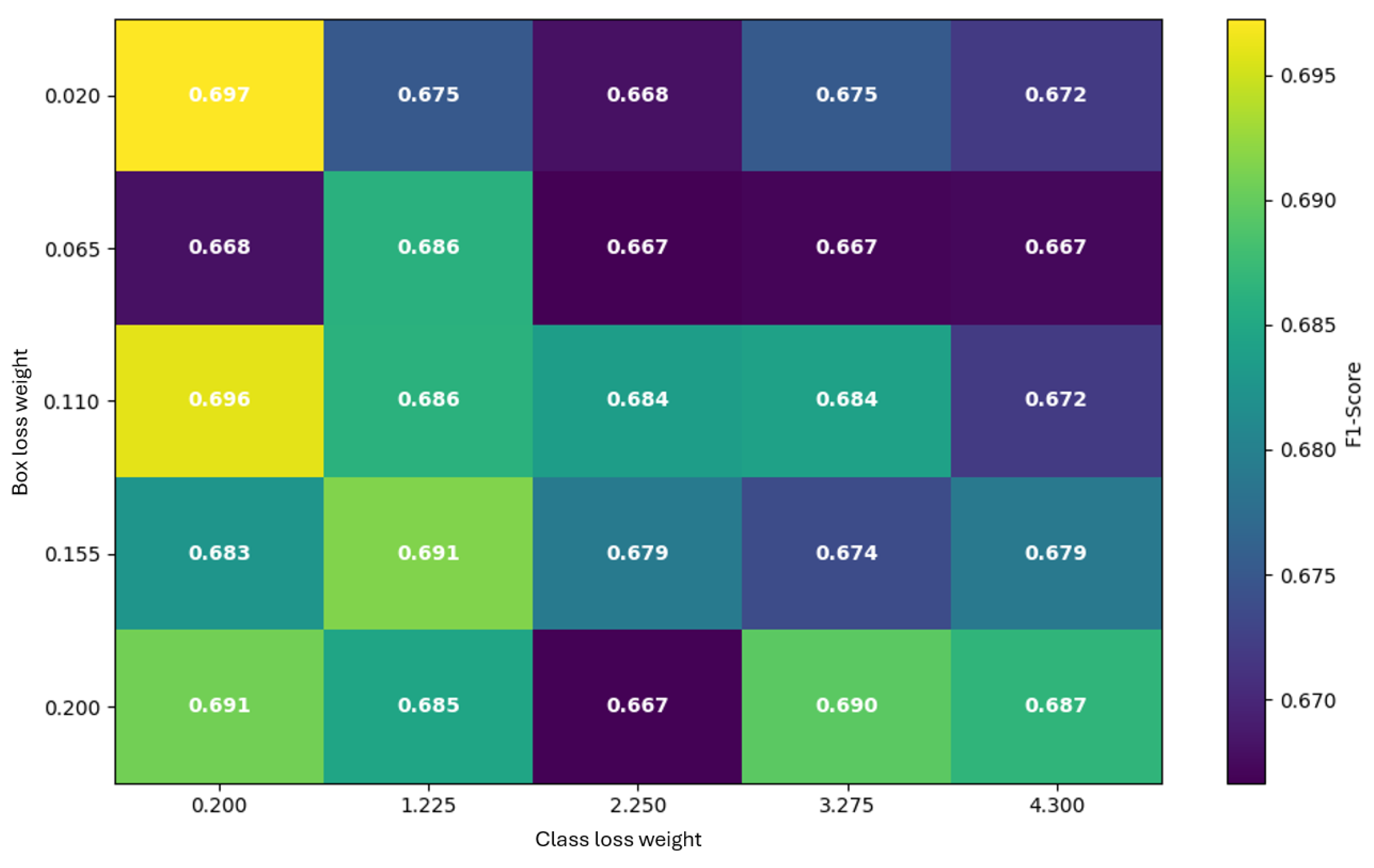

Loss Weights (box and class)

Box and class loss gains were tuned over 25 combinations;

Figure 17 shows the best F1 per pair.

Overall peak F1 is 0.697 at , , reaching its maximum by epoch 45. With no further improvement is observed (best , F1 , epoch 116). With , the second-best result is F1 at by epoch 24, while higher class weights reduce performance (e.g., 0.672 at 4.300, epoch 130). With , the best is F1 at by epoch 93; very high class weight underperforms (0.679 at 4.300, epoch 182). With , the best is F1 at by epoch 37; larger class weights again degrade results.

None of the loss-weight combinations surpassed the F1 from the learning-rate optimization; the top loss-weight result is about 3% lower than the LR peak (cf.

Figure 16). A check of defaults showed the library’s box loss gain set near

, while the documented tuning range here was

–

. Despite being only suggested ranges, the default is orders of magnitude higher than the explored grid.

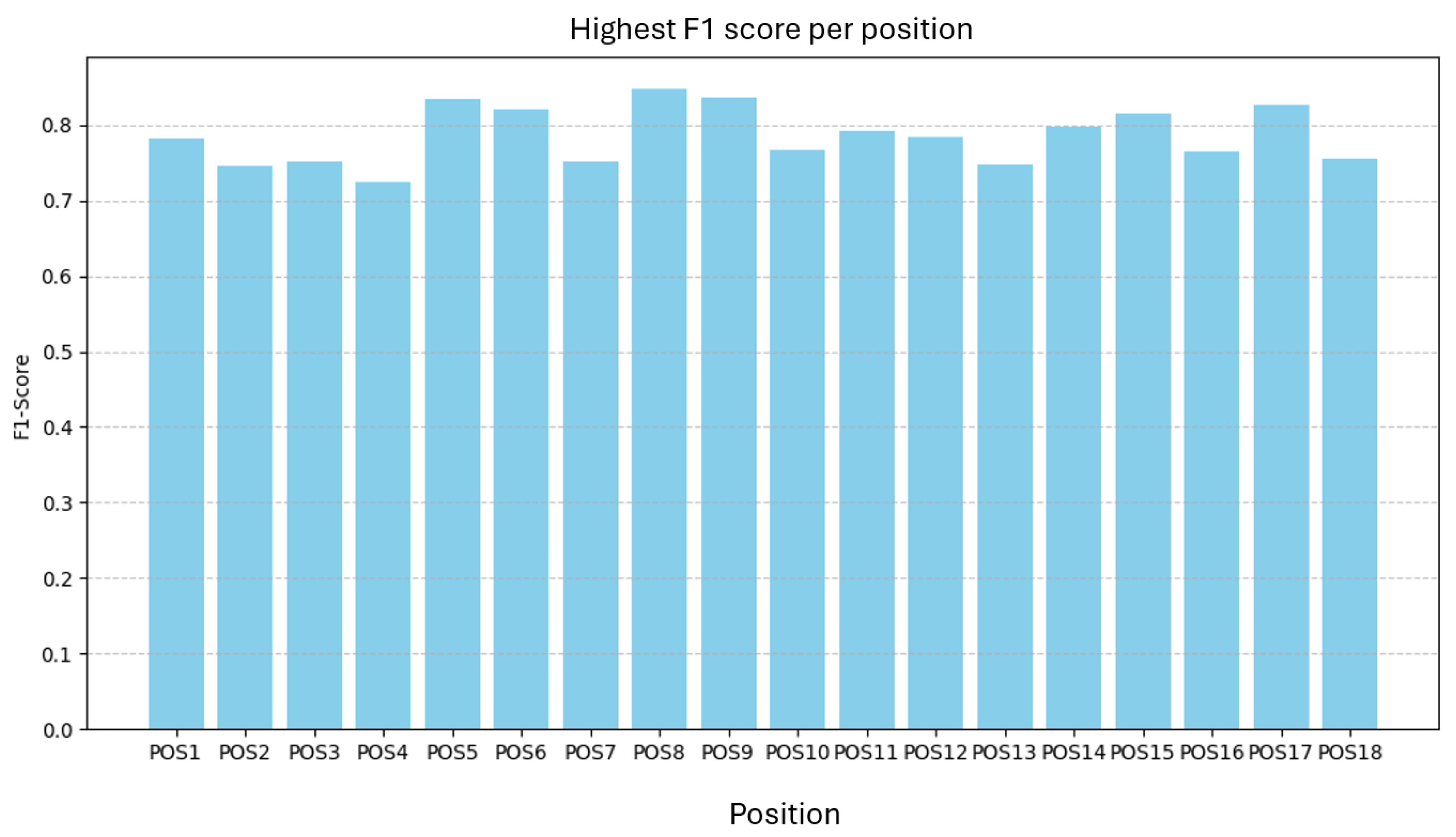

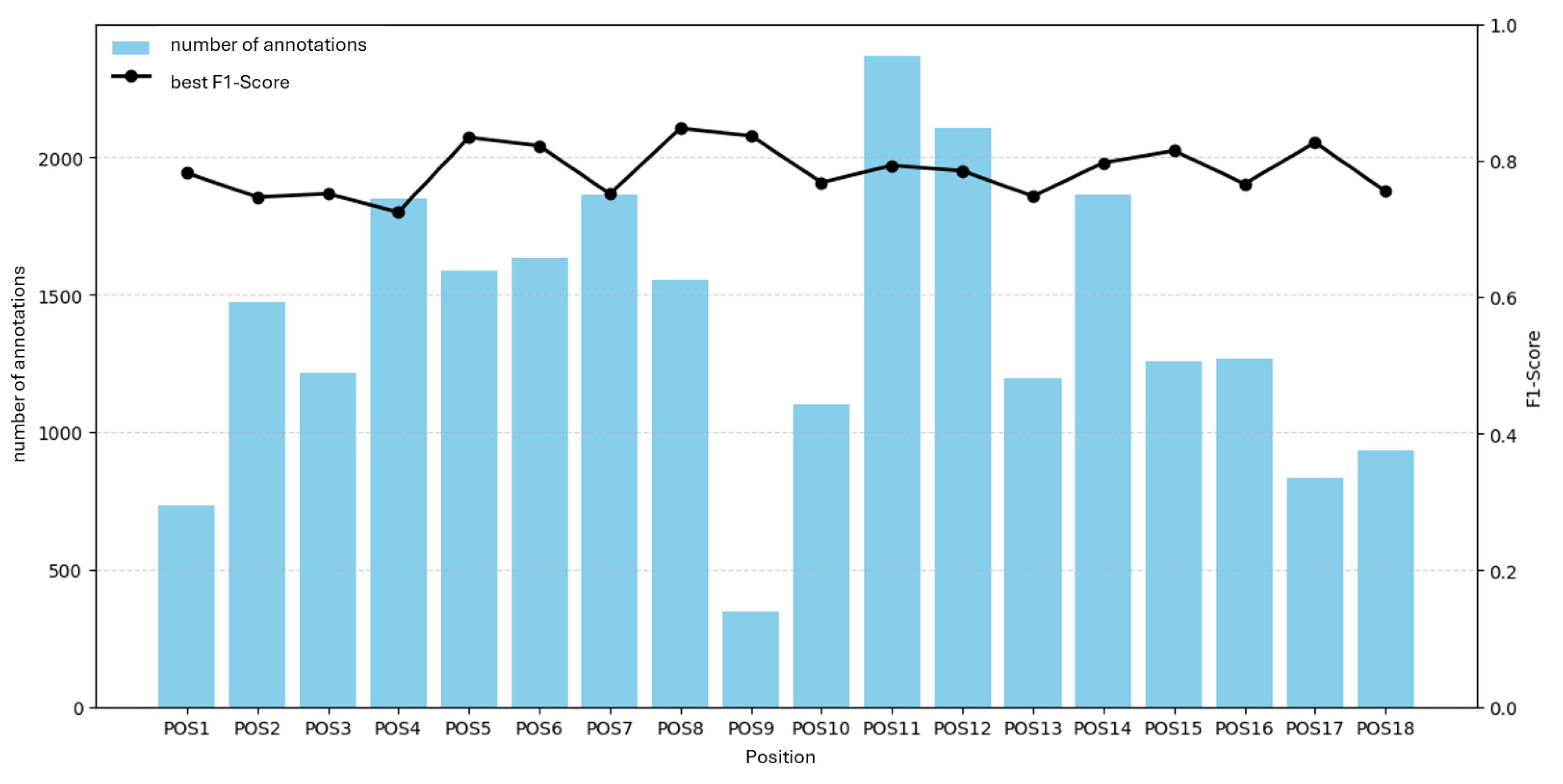

2.7.1. Results on H530H (Part B)

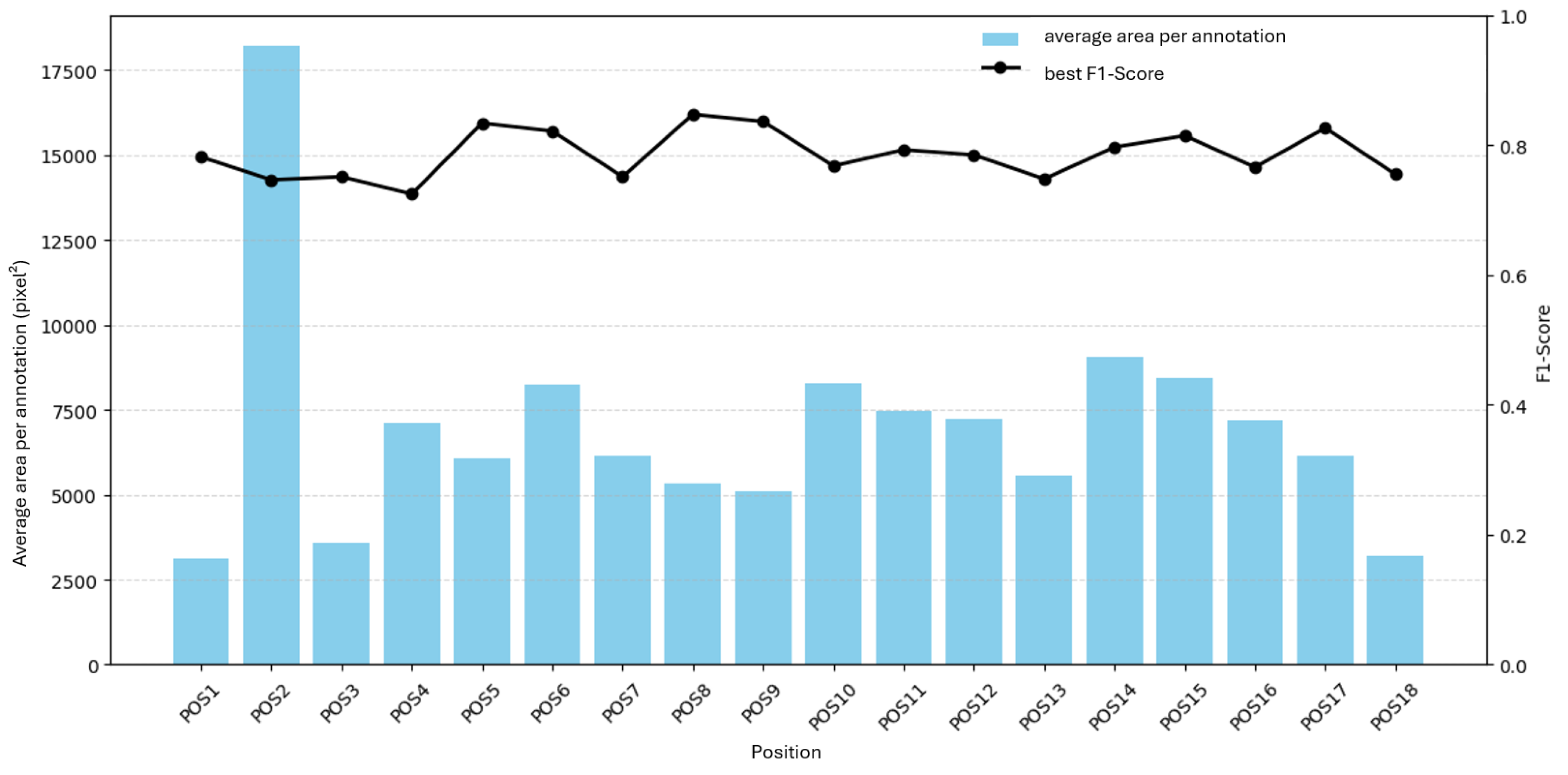

As in Part A, we trained one model per position and one joint model on all positions, each with the best tested hyperparameters for Part B. The best F1 per position is shown in

Figure 18.

F1 ranges from 0.72 to 0.85 with a mean of 0.79, a span of

.

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 show F1 versus annotation count and average annotation area. No clear relationship is evident.

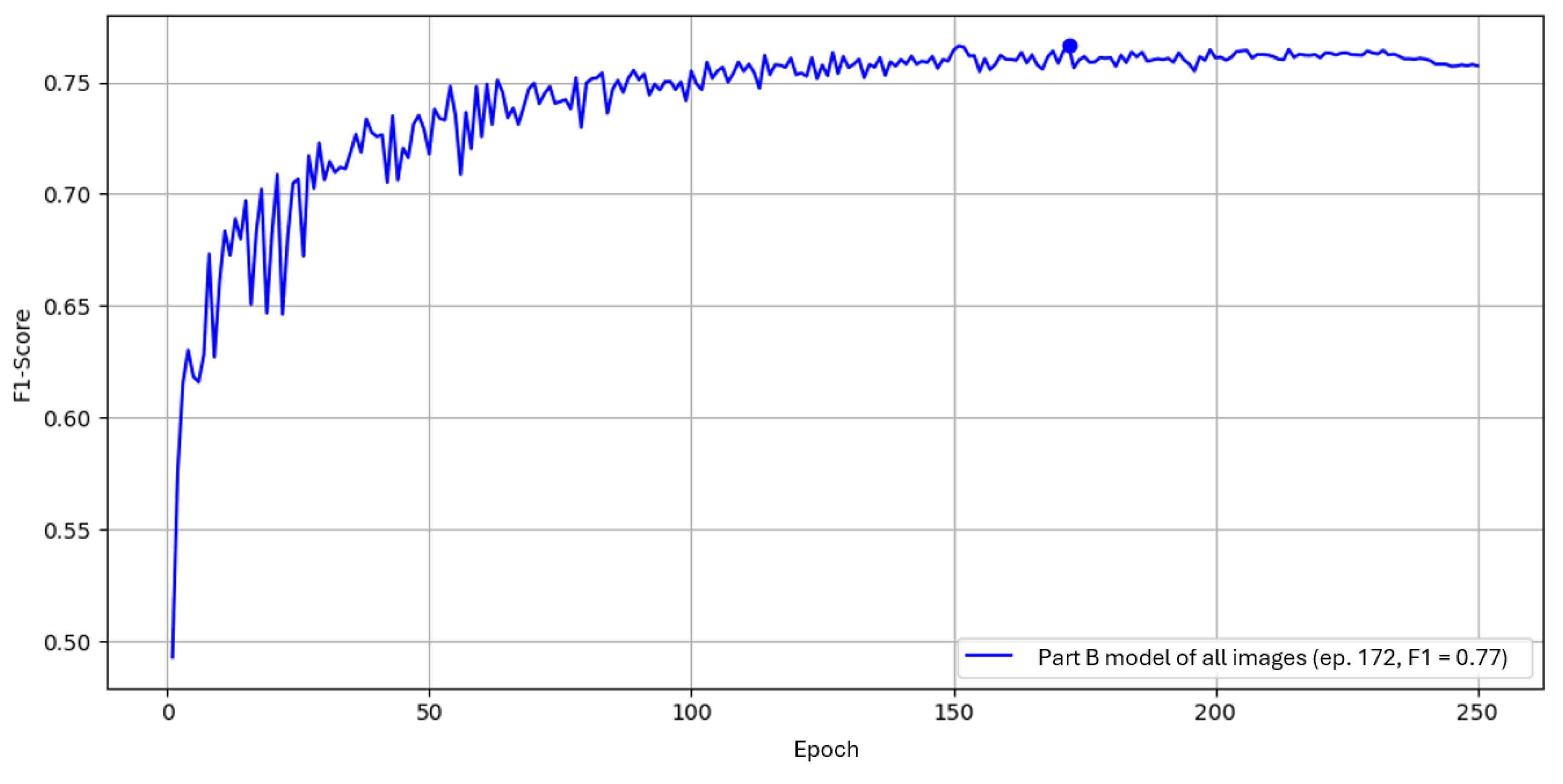

A joint model trained on the full H530H dataset is shown in

Figure 21. Its peak F1 is again about 0.02 below the mean of the position-specific models. As with Part A, practical tests compare both approaches on example images to assess generalization to previously unseen defects.

2.8. Practical Live Test

The purpose was to validate shop-floor readiness on legacy X-ray equipment and benchmark the system against certified inspectors with emphasis on critical defects. The test spanned two calendar weeks. During this period, all sampled images deemed critical were stored and included in the evaluation; in addition, 10 randomly selected images per part were added for a complete comparison. A blind, paired evaluation was conducted: for each part, the system and the inspectors reviewed exactly the same image set. Both model types were tested in parallel: a position-specific model (trained per position) and a part-level model (trained on all positions of the part). For critical defects, the check was limited to whether the model detected the same findings that the materials inspector reported. Images were frozen before the test; no retraining was performed. The operating point was fixed from validation, and disagreements were adjudicated to form ground truth.

2.8.1. Metrics

Per-class Precision, Recall, and F1 were reported. False-positive rate and review time per image were recorded where applicable. Throughput and latency were not measured in this test.

2.8.2. Connection Between GUI and X-Ray System

As outlined in Section Industrial Context and Equipment, the cell uses VistaPlusV for acquisition and viewing, which exposes no API. To enable automated ingestion by the evaluation software, the vendor’s user-defined processing scripts are extended to save each acquired image using:

Images are written to a predefined base path on an internal network share; with a daily subfolder created automatically. The evaluation software watches this share, parses

PartName and

Position, and triggers the corresponding model.

Figure 22.

Connection between GUI and X-ray System

Figure 22.

Connection between GUI and X-ray System

This file-based bridge is robust and non-invasive; no changes to VistaPlusV or the X-ray hardware are required.

2.8.3. Review of Critical Defects

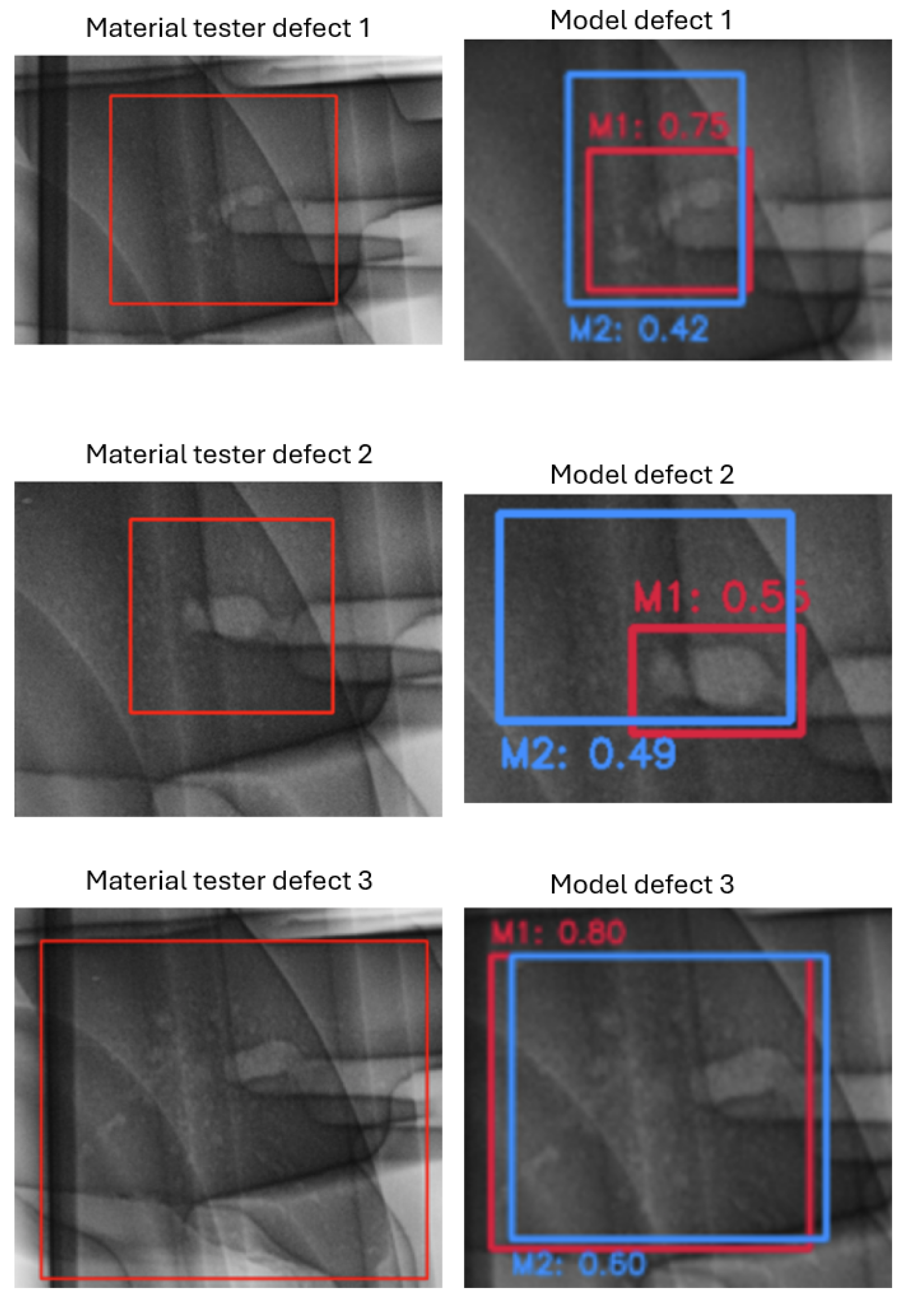

Part A (H183H). Seven images were flagged as critical (n.i.O.) by inspectors. Both models were tested: the position-specific model detected 7/7 critical findings; the part-level model detected 6/7.

Qualitative finding (Part A).

Both models correctly locate the defect; the position-specific model produces higher confidence than the part-level model.

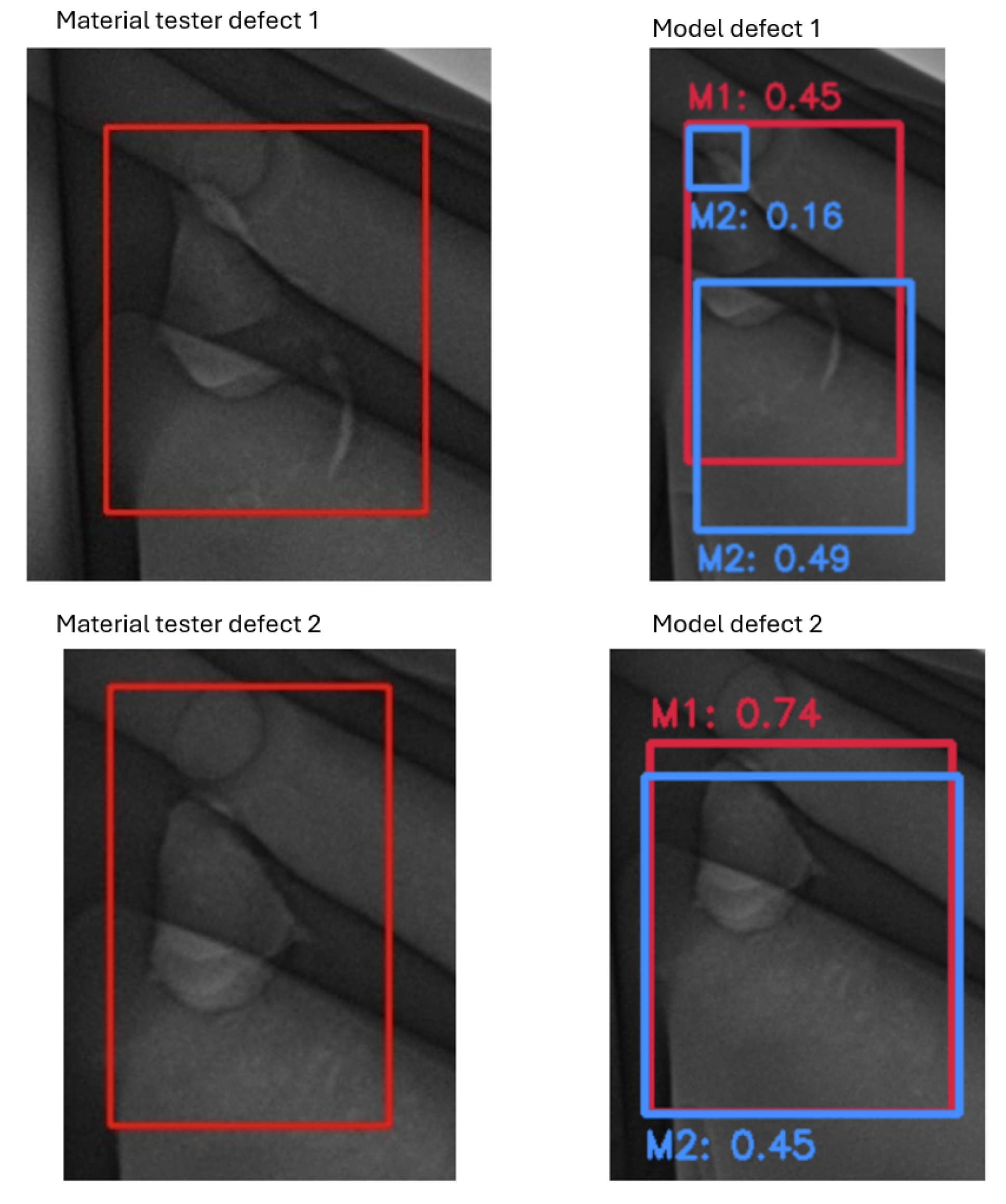

Part B (H530H). Eleven images were flagged as critical. Both models were tested and detected all relevant critical findings; the position-specific model produced tighter boxes.

Qualitative finding (Part B).

The part-level model undersegments and assigns lower confidence than the position-specific model.

2.8.4. Review of All Defects (10 Random Images per Part)

Ground truth considerations.

There is no universal ground truth for non-critical defects. All comparisons are relative between the system and certified inspectors on the same images. Disagreements were adjudicated. To avoid over-counting, split detections that referred to one physical defect were merged (“cleaning”), so each defect is counted once.

Part A (H183H).

Before cleaning, inspectors lead on F1 with strong recall; both models show high precision but lower recall (

Table 9). After cleaning (

Table 10), the picture tightens: inspectors drop slightly, while both models gain recall and F1 because merged splits reduce missed counts relative to correct counts. Net: inspectors remain best on Part A, but the position-specific model closes much of the gap; the part-level model improves yet remains behind.

Interpretation (Part A). Cleaning reduces inflated counts from fine splits. Inspector F1 drops slightly (0.916 → 0.904). The position-specific model gains recall (0.716 → 0.814) and F1 (0.830 → 0.892) at constant precision; the part-level model improves to 0.849 F1.

Part B (H530H).

Before cleaning, precision is near-perfect for all cohorts; recall drives differences (

Table 11). After cleaning (

Table 12), both models gain evidently because merged splits convert multiple near-duplicates into single correct detections, increasing recall without harming precision. Net: on Part B both models surpass inspectors on F1, with a slight edge for the part-level model.

Interpretation (Part B). Cleaning lowers inspector F1 (0.843 → 0.806) as close marks are merged; both models improve recall and F1 (position-specific 0.821 → 0.891; part-level 0.837 → 0.904).

Overall outcome.

Cleaning aligns evaluation with physical defects and rewards detectors that produce consolidated boxes rather than many small splits. After cleaning, the position-specific model remains competitive and nearly closes the gap to inspectors on Part A, while on Part B both models exceed inspector performance with high precision and improved recall.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that a one-stage detector can satisfy stringent shop-floor constraints for porosity detection in aluminum die-cast radiographs while achieving competitive accuracy relative to certified inspectors. The three central outcomes—real-time CPU feasibility, strong resolution sensitivity, and the granularity trade-off between position-specific and part-level models—directly address RQ1–RQ3. Under CPU-only deployment, YOLOv5 met the

s latency target, whereas the two-stage baseline did not, aligning with prior findings that one-stage architectures provide superior throughput on non-GPU hardware [

4,

5]. Maintaining the native spatial resolution (

) delivered the largest accuracy gains, confirming that small, low-contrast porosity signatures require high-resolution inputs [

3]. Model granularity shaped performance: position-specific models yielded sharper localization at the trained pose, while the part-level model generalized better across poses and slightly exceeded inspectors on one part.

Comparable patterns are reported in other industrial and medical DL applications. In industrial surface-inspection systems, Lu and Lee demonstrate real-time defect detection using a lightweight YOLO-based network, though their deployment relies on GPU acceleration, highlighting that many industrial workflows meet throughput requirements via dedicated hardware rather than CPU-only execution [

11]. In medical imaging, by contrast, object-detection models such as Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet, or YOLOv5 are commonly used in offline diagnostic pipelines, where inference times of several seconds are acceptable and accuracy is prioritized over strict latency constraints, as reviewed by Elhanashi et al. [

12]. These cross-domain observations emphasize that the

s requirement addressed in this study is domain-specific and significantly stricter than typical inspection or diagnostic settings.

4.1. Interpretation Relative to Hypotheses and Prior Work

The results support all hypotheses without requiring restatement of the findings. H1 is validated by the clear latency separation between one-stage and two-stage models, consistent with analyses attributing throughput advantages to shared backbone computation and simplified detection heads. H2 is supported by the strong dependency of detection quality on input resolution, extending prior work by demonstrating that this effect persists under strict CPU-only deployment constraints. H3 is reflected in the observed trade-off between specialization and generalization: view-specific training sharpens decision boundaries but reduces robustness, whereas pooled training broadens coverage at the cost of localization precision. These interpretations position the present findings as aligned with, and extending, established theoretical and empirical work in industrial vision.

4.2. Implications for Industrial Practice.

For safety-critical inspection, the live-test analysis indicates that the risk of missing critical defects can be controlled with a CPU-feasible pipeline when the operating point is fixed from validation and when high-resolution inputs are used. Counting rules materially affect perceived performance. Merging split detections into single physical defects (“cleaning”) produced a modest decrease in inspector F1 and a concomitant increase in model recall and F1, suggesting that detectors tend to fragment extended porous regions. Consequently, operational KPIs should be reported on physical defects rather than raw mark counts to avoid bias against automated systems that intentionally over-segment for safety.

4.3. Limitations.

The study analyzes two parts in one production cell and one defect class (porosity) on 2D radiographs; external validity to other parts, exposure recipes, or CT data remains untested. The live-test samples for critical defects were small, so uncertainty is non-negligible. For non-critical findings, ground truth required adjudication and thus retains residual subjectivity. Finally, throughput and latency were not instrumented during the live test; only qualitative real-time behavior was observed.

4.4. Future Directions.

Three extensions are immediate. First, broader prospective studies with instrumented logging should quantify end-to-end latency, cold-start effects, and operator interaction time. Second, small-budget automated tuning constrained to deterministic hyperparameters may reduce calibration effort across parts and positions. Third, post-processing that learns to consolidate neighboring boxes could reduce split detections without degrading recall. Additional opportunities include calibrated uncertainty for triage, periodic active learning from adjudicated disagreements, and evaluation on multi-class defect scenarios and CT volumes.

5. Conclusions

A deployable, CPU-only pipeline for automated porosity detection in production radiographs is feasible on legacy X-ray equipment using a non-invasive, file-based interface. Among evaluated detectors, the one-stage family met strict latency targets; with native-resolution inputs and modest deterministic tuning, YOLOv5 achieved competitive accuracy. In live operation, all critical defects were detected on one part and nearly all on the other, meeting the primary acceptance focus. When evaluation counts are aligned to physical defects, automated models match or exceed inspector performance in representative settings.

For practice, position-specific models are preferable where tight localization at a fixed pose is paramount; part-level models are advantageous when cross-position generalization and workflow simplicity are prioritized. Adoption should fix the operating point, retain high-resolution inputs when computation permits, and report KPIs after consolidating split detections. Under these conditions, AI-assisted inspection can improve consistency and reduce the risk of missed critical defects in aluminum die casting while operating within existing IT and hardware constraints.

Figure 1.

Annotations per inspection position for Part A (POS1–POS9). Bars show total porosity annotations per position; dashed line indicates the median across positions.

Figure 1.

Annotations per inspection position for Part A (POS1–POS9). Bars show total porosity annotations per position; dashed line indicates the median across positions.

Figure 2.

Annotations per inspection position for Part B (POS1–POS18). Bars show total porosity annotations per position; dashed line indicates the median across positions.

Figure 2.

Annotations per inspection position for Part B (POS1–POS18). Bars show total porosity annotations per position; dashed line indicates the median across positions.

Figure 5.

Procedure for model training and hyperparameter optimization.

Figure 5.

Procedure for model training and hyperparameter optimization.

Figure 6.

Identical defects in the microstructure: a) original resolution (), b) downscaled ().

Figure 6.

Identical defects in the microstructure: a) original resolution (), b) downscaled ().

Figure 7.

YOLOv5 across input resolutions over 250 epochs on Part A, position 1, measured by F1.

Figure 7.

YOLOv5 across input resolutions over 250 epochs on Part A, position 1, measured by F1.

Figure 9.

F1 over 250 epochs for combinations of box and class loss gains.

Figure 9.

F1 over 250 epochs for combinations of box and class loss gains.

Figure 10.

Training and validation losses over time. Vertical line: epoch of peak F1.

Figure 10.

Training and validation losses over time. Vertical line: epoch of peak F1.

Figure 11.

Best F1 per position for H183H (Part A).

Figure 11.

Best F1 per position for H183H (Part A).

Figure 12.

F1 versus number of annotations per position for H183H.

Figure 12.

F1 versus number of annotations per position for H183H.

Figure 13.

F1 versus average annotation area per position for H183H.

Figure 13.

F1 versus average annotation area per position for H183H.

Figure 14.

F1 over epochs using the full H183H dataset (joint model).

Figure 14.

F1 over epochs using the full H183H dataset (joint model).

Figure 15.

YOLOv5 across input resolutions over 250 epochs on Part B, position 6, measured by F1.

Figure 15.

YOLOv5 across input resolutions over 250 epochs on Part B, position 6, measured by F1.

Figure 17.

Heatmap of peak F1 across box and class loss gains on Part B over 250 epochs.

Figure 17.

Heatmap of peak F1 across box and class loss gains on Part B over 250 epochs.

Figure 18.

Best F1 per position for H530H (Part B).

Figure 18.

Best F1 per position for H530H (Part B).

Figure 19.

F1 versus number of annotations per position for H530H.

Figure 19.

F1 versus number of annotations per position for H530H.

Figure 20.

F1 versus average annotation area per position for H530H.

Figure 20.

F1 versus average annotation area per position for H530H.

Figure 21.

F1 over epochs using the full H530H dataset (joint model).

Figure 21.

F1 over epochs using the full H530H dataset (joint model).

Figure 23.

Critical example for Part A: M1 (position-specific) vs. M2 (part-level). Both detect the defect, with M1 assigning higher confidence; confidence values indicate detector certainty but are not used in the evaluation.

Figure 23.

Critical example for Part A: M1 (position-specific) vs. M2 (part-level). Both detect the defect, with M1 assigning higher confidence; confidence values indicate detector certainty but are not used in the evaluation.

Figure 24.

Critical example for Part B: M1 (position-specific) vs. M2 (part-level). M2 localizes the defect only partially and at lower confidence; M1 provides fuller coverage with higher confidence.

Figure 24.

Critical example for Part B: M1 (position-specific) vs. M2 (part-level). M2 localizes the defect only partially and at lower confidence; M1 provides fuller coverage with higher confidence.

Table 1.

Aggregate dataset summary for anonymized components.

Table 1.

Aggregate dataset summary for anonymized components.

| Component |

#Positions |

Images (total) |

Annotations (total) |

Images/Position (median) |

| Part A |

9 |

2,700 |

12,960 |

300 |

| Part B |

18 |

2,700 |

27,443 |

150 |

Table 2.

Industrial PC (inference target) hardware and OS.

Table 2.

Industrial PC (inference target) hardware and OS.

| Component |

Specification |

Notes |

| CPU |

Intel Core i5-13500 |

14 cores / 20 threads (6P + 8E), CPU-only |

| RAM |

16 GB |

|

| GPU |

— |

No discrete GPU |

| Storage |

SSD (industrial grade) |

|

| OS |

Windows 11 Enterprise |

Endpoint security active |

| Runtime |

Single-file EXE (PyInstaller) |

No Python env on host |

Table 3.

CPU runtime preselection on the industrial PC (batch size 1; timed runs; first run discarded from the mean).

Table 3.

CPU runtime preselection on the industrial PC (batch size 1; timed runs; first run discarded from the mean).

| Framework |

Source image (px) |

Model input (px) |

Mean [s] |

Min / Max [s] |

| YOLOv5 (pretrained) |

2016×2016 |

640×640 |

1.33 |

1.261 / 2.39 |

| Faster R-CNN (pretrained) |

2016×2016 |

640×640 |

5.59 |

3.718 / 9.698 |

Table 4.

Training times for YOLO variants over 250 epochs.

Table 4.

Training times for YOLO variants over 250 epochs.

| Model |

Total time [min] |

Time to best F1 [min] |

Avg. time / epoch [min] |

| YOLOv5 |

19.08 |

10.20 |

0.08 |

| YOLOv8 |

19.39 |

10.83 |

0.08 |

| YOLOv9 |

18.60 |

12.45 |

0.07 |

| YOLOv10 |

32.16 |

20.42 |

0.13 |

| YOLOv11 |

21.47 |

18.32 |

0.09 |

Table 5.

Training time versus input resolution

Table 5.

Training time versus input resolution

| Resolution |

Total (min) |

Time to best F1 (min) |

Avg/epoch (min) |

| 640x640 |

19.20 |

17.30 |

0.08 |

| 896x896 |

31.95 |

18.57 |

0.13 |

| 1152x1152 |

48.61 |

47.69 |

0.19 |

| 1408x1408 |

69.46 |

43.54 |

0.28 |

| 1664x1664 |

96.84 |

75.89 |

0.39 |

| 1920x1920 |

125.71 |

61.67 |

0.50 |

| 2016x2016 |

146.56 |

49.83 |

0.59 |

Table 6.

Grid of box and class loss weights

Table 6.

Grid of box and class loss weights

| Box loss / Class loss |

0.200 |

1.225 |

2.250 |

3.275 |

4.300 |

| 0.020 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| 0.065 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| 0.110 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| 0.155 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

| 0.200 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

Table 7.

Effect of box and class loss weights on performance (sorted by F1)

Table 7.

Effect of box and class loss weights on performance (sorted by F1)

| Box |

Class |

F1 |

Epoch |

| 0.155 |

2.25 |

0.755 |

181 |

| 0.065 |

4.30 |

0.749 |

132 |

| 0.155 |

4.30 |

0.741 |

190 |

| 0.200 |

3.28 |

0.737 |

142 |

| 0.110 |

4.30 |

0.728 |

214 |

| 0.020 |

4.30 |

0.726 |

106 |

| 0.200 |

0.20 |

0.690 |

59 |

Table 8.

Best parameter set within the tested search space

Table 8.

Best parameter set within the tested search space

| Parameter |

Value |

| Input resolution |

2016 |

| Learning rate |

|

| Class loss gain |

2.250 |

| Box loss gain |

0.155 |

Table 9.

All defects on Part A (as read, before cleaning): per-cohort counts and metrics

Table 9.

All defects on Part A (as read, before cleaning): per-cohort counts and metrics

| Cohort |

TP (Correct) |

FP (False) |

FN (Missed) |

Precision / Recall / F1 |

| Inspector |

103 |

2 |

17 |

0.981 / 0.858 / 0.916 |

| Position-specific |

83 |

1 |

33 |

0.988 / 0.716 / 0.830 |

| Part-level |

79 |

2 |

40 |

0.975 / 0.664 / 0.790 |

Table 10.

All defects on Part A (cleaned by merging split marks): per-cohort counts and metrics

Table 10.

All defects on Part A (cleaned by merging split marks): per-cohort counts and metrics

| Cohort |

TP (Correct) |

FP (False) |

FN (Missed) |

Precision / Recall / F1 |

| Inspector |

89 |

2 |

17 |

0.978 / 0.840 / 0.904 |

| Position-specific |

83 |

1 |

19 |

0.988 / 0.814 / 0.892 |

| Part-level |

79 |

2 |

26 |

0.975 / 0.752 / 0.849 |

Table 11.

All defects on Part B (as read, before cleaning): per-cohort counts and macro-averaged metrics

Table 11.

All defects on Part B (as read, before cleaning): per-cohort counts and macro-averaged metrics

| Cohort |

TP (Correct) |

FP (False) |

FN (Missed) |

Precision / Recall / F1 |

| Inspector |

91 |

0 |

37 |

1.000 / 0.746 / 0.843 |

| Position-specific |

90 |

1 |

38 |

0.996 / 0.712 / 0.821 |

| Part-level |

94 |

0 |

35 |

1.000 / 0.742 / 0.837 |

Table 12.

All defects on Part B (cleaned by merging split marks): per-cohort counts and macro-averaged metrics

Table 12.

All defects on Part B (cleaned by merging split marks): per-cohort counts and macro-averaged metrics

| Cohort |

TP (Correct) |

FP (False) |

FN (Missed) |

Precision / Recall / F1 |

| Inspector |

75 |

0 |

36 |

1.000 / 0.676 / 0.806 |

| Position-specific |

90 |

1 |

21 |

0.989 / 0.811 / 0.891 |

| Part-level |

94 |

0 |

20 |

1.000 / 0.825 / 0.904 |