1. Introduction

The fundamental need of humans is water, and groundwater is the major source for drinking (He et al., 2015; Morris, 2003). Control over the water resources has remained central all rulers globally (Zakir-Hassan, Allan, et al., 2023). It is considered a major source of drinking water due to its purified nature in soil column which is approximately half of the drinking water supply globally (Olufemi, 2010; Snousy et al., 2021). About one-third of global irrigation requirements are met by groundwater. The mainstay of 50% of world’s population for the drinking and irrigation is groundwater by consuming 30% of freshwater reserves of the world (Siebert et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2020; Snousy et al., 2021; Zektsar, 2013) while the remaining 70% is in the form of the ice caps, glaciers, and the other water bodies i.e., rivers and streams (Chandnani et al., 2022; Punthakey et al., 2021). About 2.2 billion people depends solely on groundwater to fulfil their basic water needs and supply of good quality drinking water (Adimalla and Qian, 2019; Chique et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2017). Groundwater underpins global food security as about 40% of global food is produced from groundwater (Leslie et al., 2022). Recent infrastructure developments and global population increase has significantly increased the groundwater consumption. In under-developing countries like Pakistan, people in rural and urban areas use groundwater for irrigation and drinking. Over 70% of Pakistan’s rural population has no access to safe drinking water. Groundwater is being extensively consumed in the country due to the availability of cheap technologies of groundwater extraction and better quality than surface water (Shaji et al., 2021). Further floods are a source of aquifer recharge and improved groundwater quality (Zakir-Hassan et al., 2021).

The direct and indirect disposal of industrial wastes and effluents into the environment and water bodies has significantly deteriorated the groundwater quality in the last few decades (Karangoda and Nanayakkara, 2023). Consuming polluted water is a severe concern to human health, and reclaiming the aquifer is difficult. (Gao et al., 2020; Vaithyanathan and Ravichandran, 2017). About 39,00,0 children die every year due to waterborne diseases (Solangi et al., 2019; Vaithyanathan and Ravichandran, 2017). It is a basic right for everyone to get the good quality of water for essential of their natural life (Saha et al., 2018; WHO, 2011). Multiple organizations have developed their standards based on chemical, physical and biological properties to evaluate the suitability of water, the most followed standards are of World Health Organization (WHO, 2011; Adimalla and Qian, 2019; Norouzi and Moghaddam, 2020). Knowledge of irrigation water quality is critical to understand management for long-term productivity.

In arid/semi-arid regions of the world, water quality has deteriorated due to increase in salinity problems in large aquifers of coastal areas impacted by sea water intrusion (Bahir et al., 2017; Bahir et al., 2018; El Mountassir et al., 2020; Jalali, 2007). Extra exploitation of groundwater has resulted in movement of saline water in to aquifer (Adimalla and Qian, 2019). Groundwater quality also depends upon topography, precipitation and natural minerals in lithology of the area (Aly, 2015; El Mountassir et al., 2020; Emenike et al., 2017; Sappa et al., 2015). Once the contaminants are leached down in the aquifer, their impacts on groundwater quality depend upon its chemical and biological properties, structure and other soil/rock properties (Custodio, 2012). Since a single element cannot depict the overall water quality therefore multiple parameters are brought under analysis i.e., pathogens, fluorides, nitrate, arsenic, chlorine, other metals.

Water Quality Index (WQI) explains a comprehensive picture of water quality of a specific region. Numerous researchers have used the WQI theory to obtain a single indicator and developed WQIs for irrigation and drinking (Kachroud et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2013; Swaroop Bhargava, 1983; Tiwari et al., 2017; Tyagi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2015). Water quality index parameter initially developed by Horton in 1965 has been used by different researchers (Adimalla and Taloor, 2020; Palit et al., 2018; Saleem et al., 2016) and different approaches have been used to calculate WQI (Gidey, 2018; Mutasher et al., 2021; Nisa, 2018; Prabowo et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021; Srinidhi et al., 2021).Different numerical indices, graphics, plots, diagrams have also been developed in the field of hydro geochemistry to interpret the suitability of groundwater for different uses. MAR is the process under which surplus water is stored underground for future use. Its benefits include improving groundwater quality and level. A comprehensive review of water quality monitoring and assessment in Pakistan has been carried out by (Kumar et al 2023); which revealed that tremendous rise in population, industrialization and agricultural activities are major threats for degradation of both surface and groundwater quality.

MAR and water banking are significantly important for water resources management (Hossain et al., 2019; Sherif et al., 2023). (Dillon et al., 2009; Page et al., 2010; Zakir-Hassan, 2023) define MAR as ‘‘purposeful recharge of water to aquifers for subsequent recovery or environmental benefit”. MAR can be used to buffer against drought and changing or variable climate, as well as provide water to meet growing demands. Groundwater quality cannot be ignored during MAR for sustainable groundwater management (Barry et al., 2017; Ross, 2022; Vanderzalm et al., 2015). During MAR, river water, rainwater or wastewater can be used a source (EPA_Victoria, 2009; Vanderzalm et al., 2015) for transferring to the aquifer (sink) through some managed techniques. Soils and water get contaminated by using the wastewater for irrigation of vegetable and other crops in urban areas which can be hazardous for the MAR schemes (Natasha et al., 2022; Zakir-Hassan, Punthakey, Hassan, Shabir, et al., 2022). During this whole process of MAR, it is imperative that quality of waters of both the source and the sink must be suitable for the intended purpose of the MAR (Leslie et al., 2022; Page et al., 2010; Pavelic et al., 2022). Due to high importance of irrigation water supplies and drinking water quality, there is a dire need to check the different water quality parameters for its better utilization, management, protection, and sustainable development (Zakir-Hassan, Punthakey, Hassan, & Shabir, 2022). This study has been performed to evaluate the current status of groundwater quality for its proper management, and to establish baseline data for a managed aquifer recharge project in the study area. Drainage effluents also pose adverse impacts on groundwater (Zakir-Hassan, Hassan, et al., 2022).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

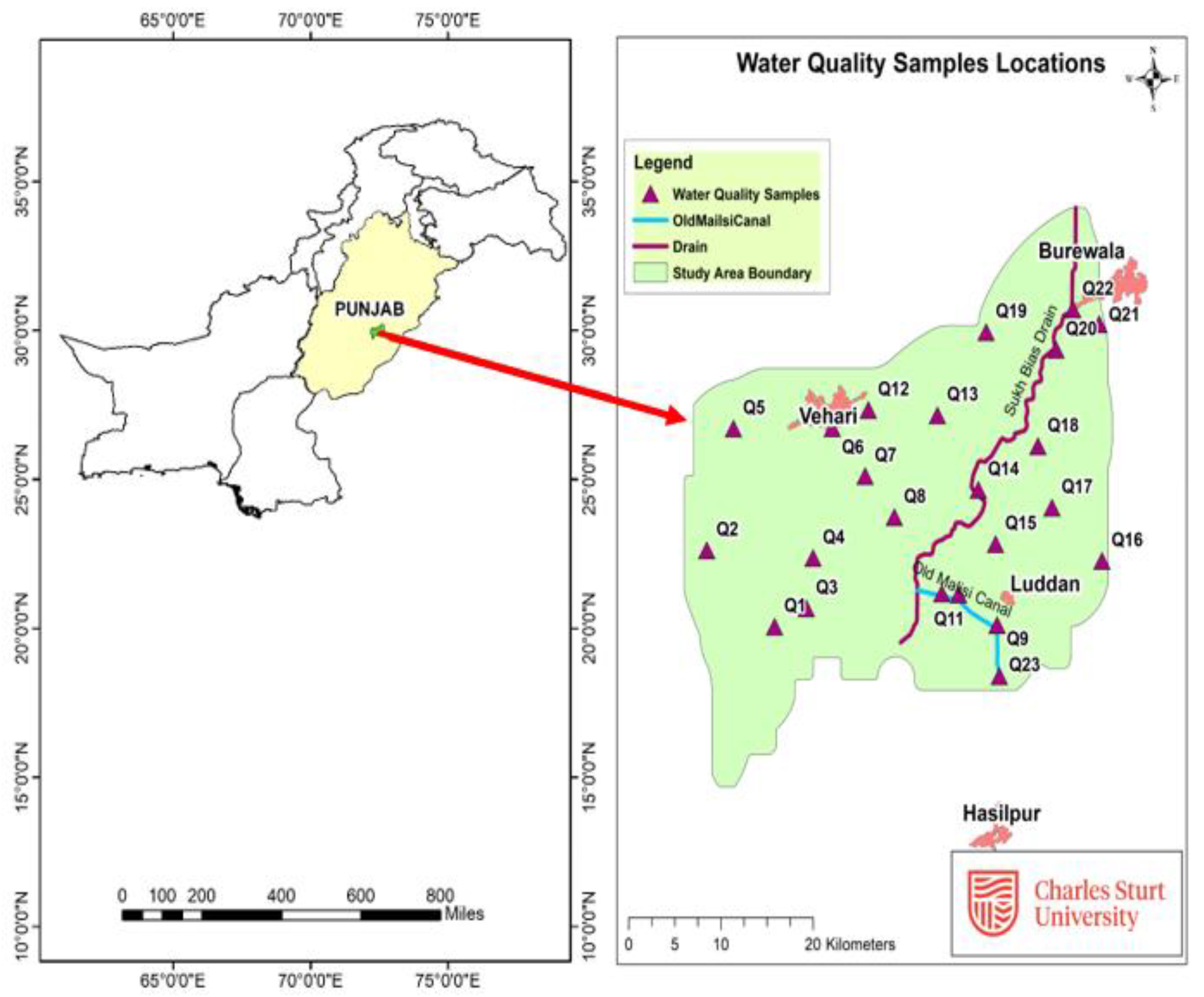

The study was carried out in Vehari district of Punjab, Pakistan located at 29.9719 °N, longitude 72.4258 °E with an area of 1371 km

2 bounded with Pakpattan Islam Link Canal, Sindhnai Mailsi Bahawal Link (SMB-link) Canal, Pakpattan Upper Canal, and River Sutlej on Eastern, Western, Northern and Southern sides, respectively. Canal network in Indus River Basin is a major source of water supply for irrigation as well for recharging the large aquifer (Zakir-Hassan, Kahlown

, et al., 2023)The area is around 140 m above mean sea level and comprises rural and urban localities. The population of district Vehari is about 2.9 million with growth rate of 2.23%, and the majority of people are linked with agriculture for their livelihood (GOP, 2018; Sindhu, 2010). Vehari is food basket for the province as well as being called the city of cotton. Groundwater levels have fallen down to 15 to 25 m below the land surface and there is sufficient potential for storage of floodwater (Zakir-Hassan et al., 2024). In addition to groundwater, canal water is also supplied through a network of canals. Map of study area with sampling locations is shown in

Figure 1. Primarily, groundwater is used for irrigation in the study area as canal water is not sufficient to meet the irrigation and drinking requirements. Managed aquifer recharge is dire need of the study area for sustainable use of groundwater (Zakir-Hassan et al., 2025).

2.2. Water Samples Collection and Lab Analysis

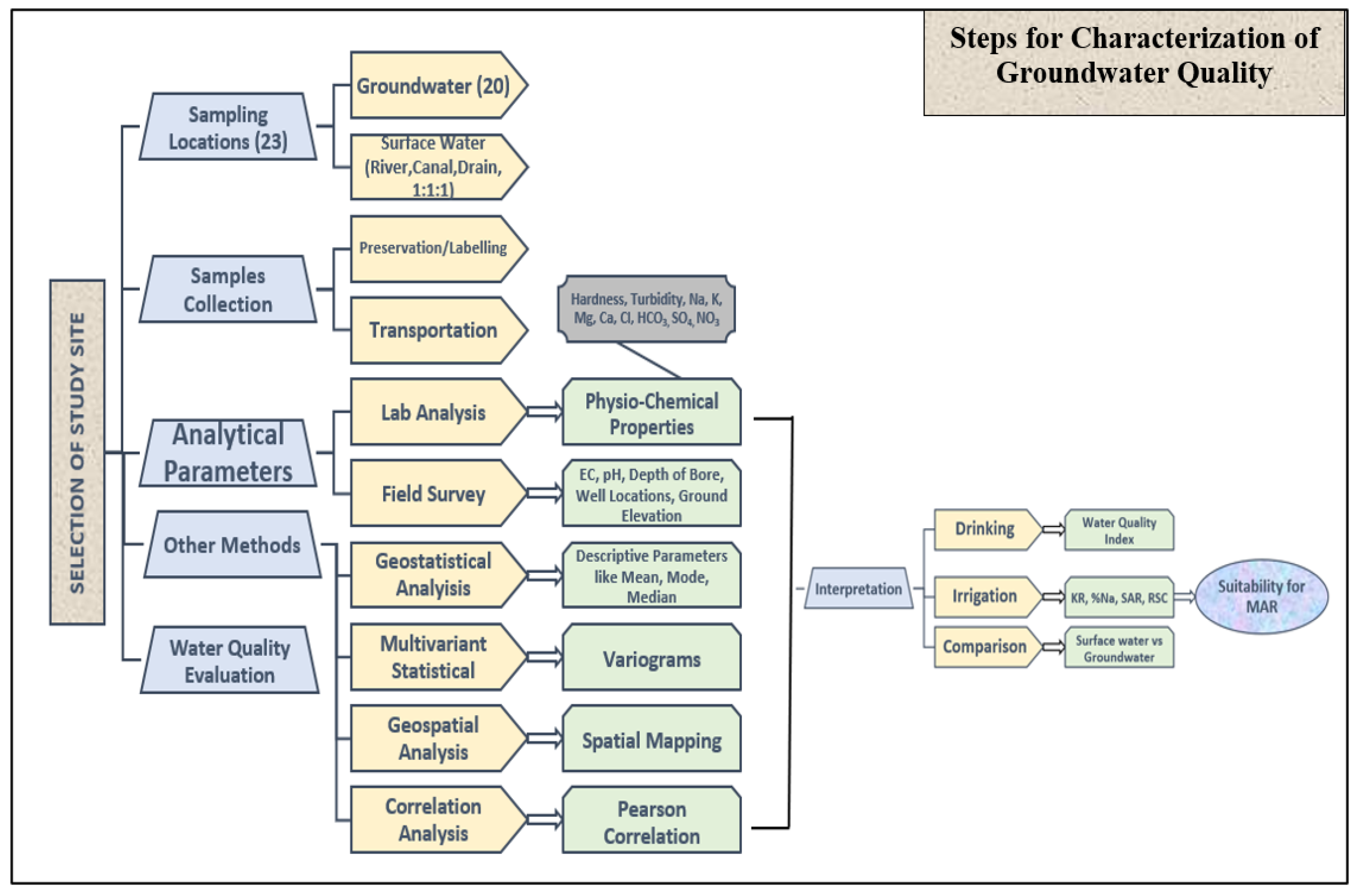

Sampling is a process to collect a portion of material small enough in volume to be transported and large enough for analysis (APHA, 2021). Total 23 water samples were collected from field during May and June 2021 as per standard procedures and methods prescribed by American Public Health Association (APHA, 2021). Some of the parameters like temperature, EC, TDS, pH, depth of bore, well locations, ground elevations, static water levels, source of water sampling (like tube wells, drain, canal, river) were collected in field during sampling using portable multi-parameter devices. These devices were calibrated as per prescribed standards before use in field. Samples were collected, sealed at site, packed in containers and transported to lab(Zakir-Hassan, 2023) . It was ensured that samples are kept at cool place (4

0C) until transportation to lab. Most of the groundwater samples have been taken from tube wells or turbines from a depth varying from 70 to 140 m with an average of 96 m. Equipment/ materials used in the field sampling were sampling bottles with lids, waterproof marker-pen for writing, labels for coding the samples, EC, pH and temperature portable meters, PPEs (gloves, field shoes, hats, drinking water), Sample containers for stacking samples, sealing tapes, field umbrella, PC tablet and field notebook/performa for recording codes and other details of samples. Samples were analyzed at laboratories of Irrigation Research Institute (IRI) and Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) as per stanadrd procedures enlisted in Table S1 in supplementary information. The overall methodology for groundwater quality analysis is depicted in

Figure 2.

Table 1. Parameters estimation (Chin, 2013; Davis, 2010).

2.3. Methods of Interpretation of Water Quality

General descriptive analysis was performed to calculate mean, standard error, standard deviation, coefficient of variance, minimum and maximum values using MS Excel (Solangi et al., 2019). Charge balance error (CBE) was calculated using Equation 1 (Adimalla & Qian, 2019; Adimalla & Taloor, 2020; Snousy et al., 2021).

Where, concentrations of all cations (Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) and anions (Cl−, HCO3−, SO4 2−, and NO3−) are in milliequivalent per liter (meq/l). CBE for all samples have been plotted in Figure S1. All values - except one value - fall within ±5% which are within permissible limit (Adimalla, 2021; Gao et al., 2020). One value which exceeds ±5%, is within the acceptable limit of ±10% (Adimalla & Qian, 2019; Mohan & Krishnakumar, 2021). This indicates the accuracy of lab analysis and reliability of results.

GS+ software was used to determine the variogram models, which is generally used to depict the variability between the spatially distributed data points. All the semi variogram models were analyzed and best fit semi variograms model were selected among spherical, exponential, Gaussian, and linear models. Pearson’s correlation analysis has been performed to estimate correlation coefficients which show the dependency of each parameter with the other parameters. This p-value test was done using the Stistica-10 at 0.01, 0.05 and 0.001 significant levels. Generally Inverse Distance Weighted Interpolation (IDWI) technique is used to spatially plot the hydro-chemical parameters of groundwater (Mohan & Krishnakumar, 2021). Standards prescribed by WHO & PID were employed to check the suitability of the water quality (Zakir-Hassan, 2023) and (WHO, 2011).

Water quality index (WQI) is considered one of the best methods to analyze and depict the quality of water, which can be used by policy and decision makers for both surface and groundwater (Adimalla & Qian, 2019; Saleem et al., 2016; Srinidhi et al., 2021). This index gives rating of water quality ranging from 0 to 100 and takes into account different parameters of a water samples and reflects the combined effect of large number of water quality parameters into a single value (Saleem et al., 2016). Equations by using the weighted arithmetical index method for calculation of WQI (Nisa, 2018; Ruhela et al., 2021; Saleem et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2021) are as under.

where, w

n is unit weight factor, S

n is standard desirable value of nth parameter, Q

n is sub-index, V

n is the mean concentration of nth parameter, V

o is the actual value of parameters in pure water (V

0 = 0 mostly), and WQI is the water quality index.

2.4. Suitability of Groundwater for Irrigation

Multiple parameters like %Sodium, (%Na), Kelly Ratio (KR), Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR), and Residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC) were calculated to evaluate the suitability of groundwater for irrigation. The evaluated parameters were plotted using ArcGIS 10.6. Sodium percentage (Na %) was calculated by the following formula (Adimalla, 2020; Wilcox, 1955):

All concentrations are in meq/l. This percentage indicates the Sodium hazard in the water, if found excessive it reduces the soil permeability. If this percentage is less than 20, water is excellent for irrigation use, up to 40 it is good, 40-60 permissible and more than 60 is doubtful.

Kelley in 1963 proposed a relation between sodium and alkaline earths (Adimalla, 2020). It is calculated using following equation: -

If KR> 1, water is safe for irrigation and if KR< 1, water is not safe for irrigation (Adimalla, 2020).

Residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC) is used to predict the additional sodium hazard associated with CaCO

3 participation and is another alternative measure of the sodium contents in relation with calcium and magnesium. This can be calculated as:

where, all concentrations are in parts per million (ppm).

Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) is an easily measured property that gives information on the comparative concentrations of sodium, calcium and magnesium (Hopkins et al., 2007). The SAR can be calculated as:

where, all concentrations are in mill equivalent per liter (meq/l)

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Geo-Statistical Analysis

The results of various parameters of descriptive analysis are presented in

Table 1. Measurements of various parameters exhibited tolerable variation among sites although there was a great variation in total dissolved solids. Only descriptive statistics relevant to sample size, mean and standard error are presented to give an indication of sampling intensity and variation of observations. Singh et al., (2022) has provided an indication of geostatistical analysis in groundwater interpretation. It analyzes the spatial patterns of values associated with different locations in a landscape.

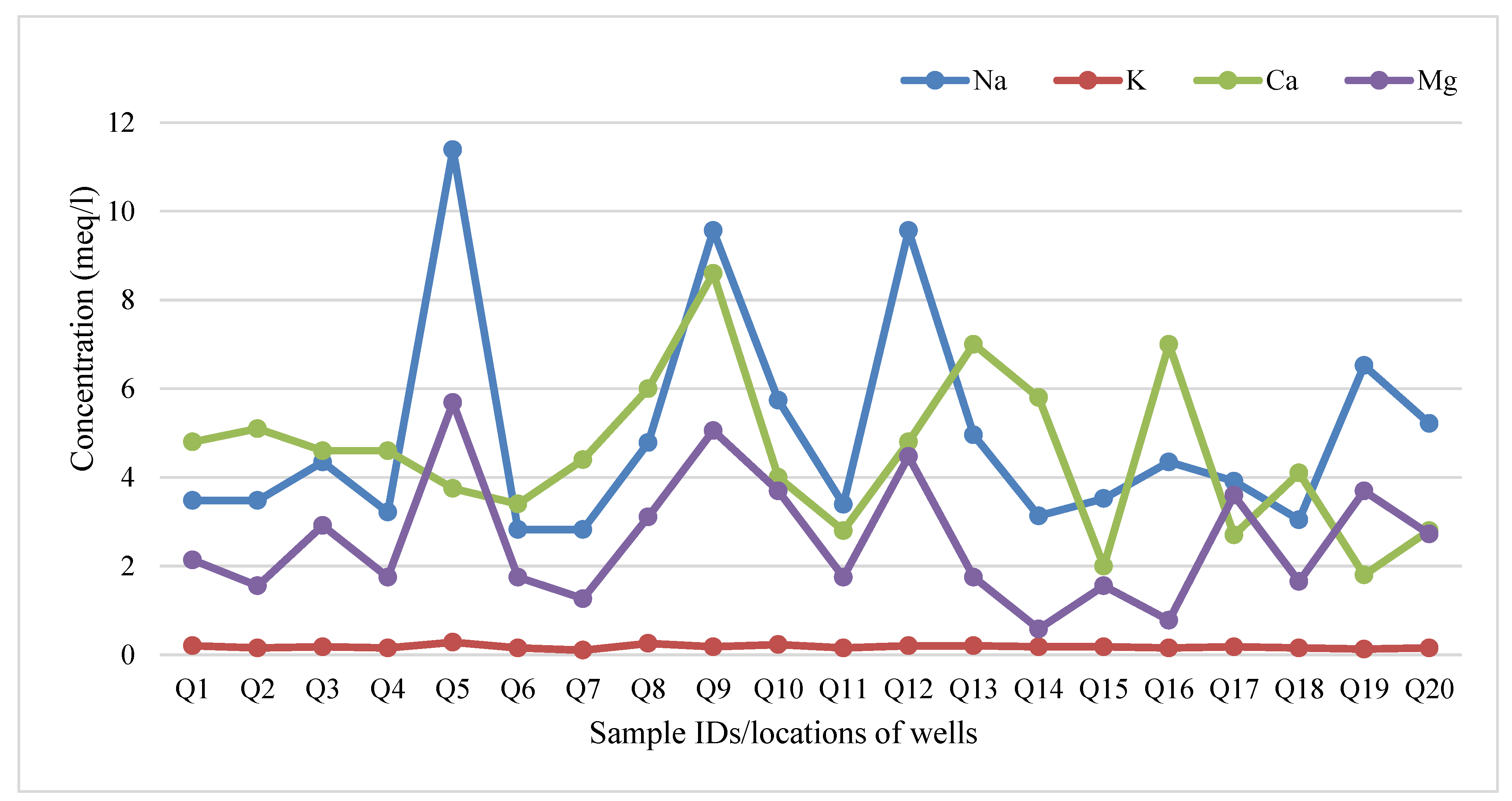

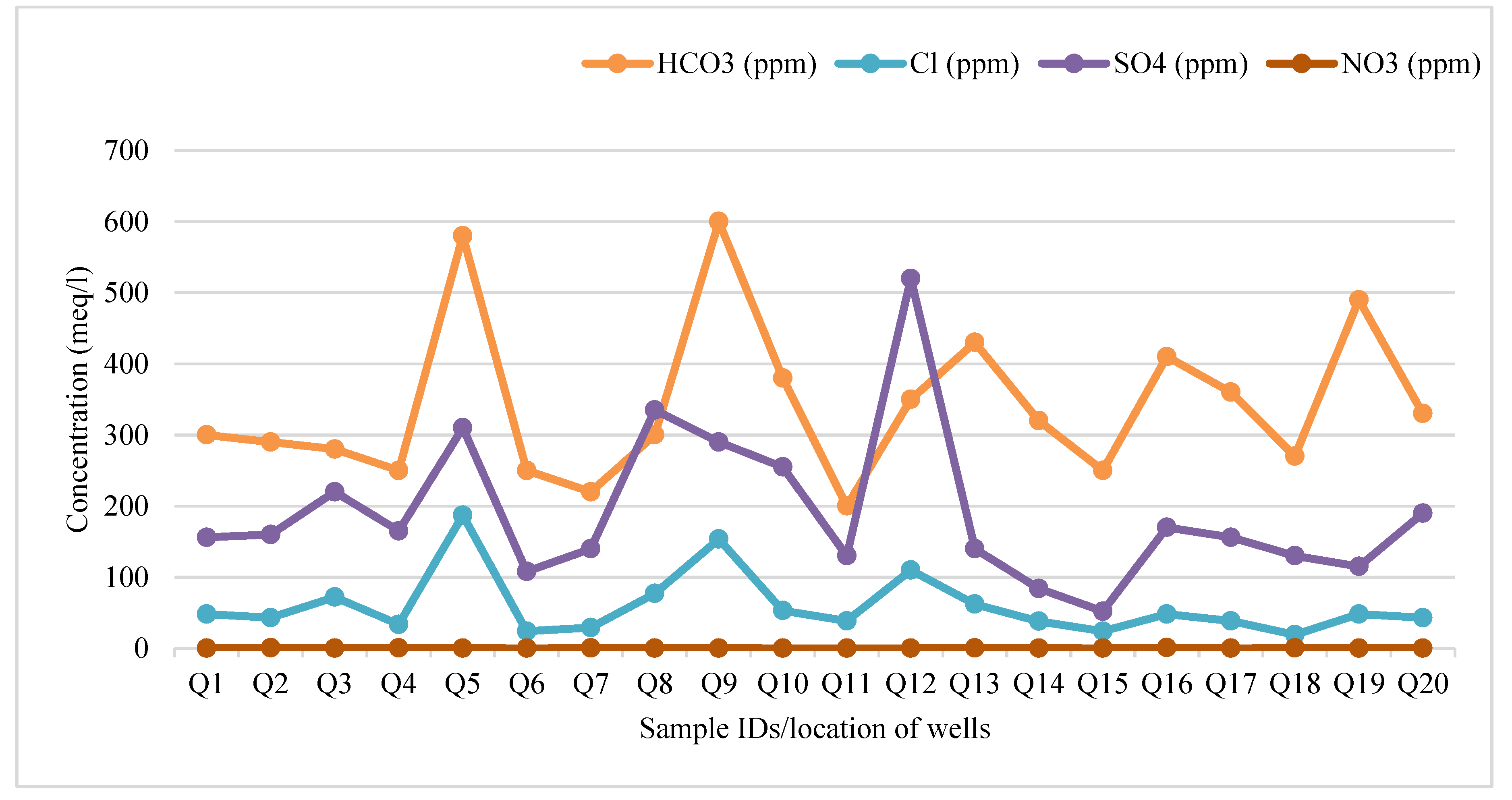

Major cations and anions in groundwater samples have been plotted to show their abundance in

Figure 3 &

Figure 4 which indicates the dominant cations are Na and Ca, while dominant anions are HCO

3 and SO

4.

It was revealed from the results of 20 water quality samples that point 5 and 12 are highly contaminated with Na. It was further observed that these points were located near Vehari City which is a source of domestic and industrial effluents. Descriptive analysis has indicated that the abundance of cations based on their mean values in ppm, both in surface as well as groundwater samples are in the order: Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+ > K+. It indicates Na is dominant salt in water samples in the study area.

It was noticed that point 5 and 9 are highly dominated with HCO

3 concentrations while point 12 was dominant in SO

4. It indicates that Vehari city (Urban Centre) is a source of contamination for groundwater and after that poor results were obtained near Ludden (thickly populated town). Descriptive analysis has indicated that the abundance of anions based on their mean values in ppm, both in surface as well as groundwater samples are in the order; HCO

3− > SO4

2− > Cl−NO

3 – respectively.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7

Lithological and anthropogenic activities are the main sources of presence of Na in water. Nominal amount of Na is suitable for blood circulation and muscles but excessive intakes have reported death cases (Malik & Sugandh, 2022). The average Na concentration of 20 water samples in study area was measured as 136.3 ppm which lies within the permissible limits set by PID. Similarly, presence of Ca in water is due to dissolution of dolomite, marble and gypsum. Limited quantity of Ca in water is helpful for muscles and bones. The average Ca concentration in the study area was calculated as 95.7 ppm which was slightly higher than the recommended or suitable range and lies in marginal category. Also, the concentration of Mg and K were slightly higher than the recommended levels as the mean values were 36.3 and 7.3 ppm as compared to standards limits i.e., 30 and 7 ppm respectively.

Bicarbonate (HCO3) is mainly responsible for reducing/neutralizing pH of water. Areas rich in limestone have excessive HCO3 in their waters. The average concentration of HCO3 in study area was 341.9 ppm which was a bit higher than the standard level of 200 ppm (WHO 2011). Generally the atmospheric deposition and sulphate dissolution are the main source of presence of sulphate in water sample (Wang & Zhang, 2019). The average SO4 concentration in study area was 245 ppm which was again a bit higher than the recommended level of 200 ppm. The concentrations of Cl and NO3 were found under the standard limit.

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

To depict and analyze the spatial correlation among various parameters, variogram analysis was performed. Results showing type, statistical parameters, and spatial class for the best fitted variogram models for each physiochemical parameter are tabulated in

Table 2. Results indicate that there is no spatial correlation for turbidity and potassium; for alkalinity and bicarbonate there is random correlation among the sampling points, but for other elements there is evidence of non-random correlation among the parameters.

3.3. Pearson Correlation Analysis

Pearson’s correlation factor (r) is a factor which associates the strength of correlation between two parameters. It has the value equal to 1, when a parameter is compared with itself, it shows perfect correlation – r = 1. Values of r > 0.7 or −0.7 indicate that the parameters are vigorously correlated, while values of the r from 0.5 to 0.7 or −0.5 to −0.7 depict reasonable correlation (Mohan & Krishnakumar, 2021). Results are presented in a tabular form called Correlation Matrix shown in

Table 3. Values of positive correlation indicated the shared origin between the parameters and negative correlation indicated the diverse sources of origin (Mohan & Krishnakumar, 2021). According to p-value we can find the significance between different parameters. If the p-value is less than or equal to 0.001 and 0.01 then the co-relation is significant. If the p-value is greater than 0.05 then it is considered that there is no co-relation.

As shown in

Table 3, HCO

3 has perfect relation with Alk while NO

3 has weak relation with Ca. Ca has weak relation with Alk and HCO

3. Turbidity has no strong relation with any other parameter. TDS has strong relation with EC, Alk, HCO

3, Hardness, Mg and SO

4. Sodium (Na) has weak relation with Ca and K while strong relation with all other parameters. Whereas SO

4 has weak relation with alkalinity, HCO

3, Ca and pH, on the other hand exhibit moderate relation with Cl, hardness, and Mg; same is for potassium (K) has which has moderate relation with these three parameters. Mg has strong relation with Cl and EC. Hardness is vigorously correlated with alkalinity.

3.4. Subsurface Hydrogeology

Bore logs drilled by different organizations in the study area were analyzed to depict the subsurface hydrogeology of the study area. The surficial materials typically encountered along the bed of OMC, through which the surface water flows, are of variable thickness ranging from 1 to 3 m, mostly alluvial, generally comprised of water-deposited silt, silty sand, interspersed with silty clay. These materials rest on the underlying sandy aquifer throughout canal. The silt particles in the top layer are well-graded and generally not permeable. By considering the extent and geological make-up of the surficial materials, direct recharge of water from the ground 180 surface into the underlying sand aquifer through these materials are unlikely to be substantial due to the low hydraulic conductivity of the surficial materials. These findings suggest that to recharge the main groundwater aquifer effectively, it would require drilling and installation of injection/recharge wells at the project site to facilitate/accelerate water recharge from the ground surface into the more permeable underlying sandy aquifer (Zakir-Hassan, 2023).

3.5. Suitability of Groundwater for Drinking Purpose

The major use of groundwater in the study area is for irrigation applications but it is also being used for drinking. In urban area of Vehari city, Municipal Committee Vehari is pumping groundwater from a pump station nearby the Pakpatan Main Canal and transporting to the city to provide drinking water to the community. In rural areas, HUD & PHED have constructed rural water supply schemes (RWSS) to supply drinkable groundwater to the rural population. Some people are extracting groundwater directly through hand pumps and small submersible pumping units at household level. Groundwater is a major source of water for drinking and evaluation of its existing level of contamination is important for the human-health and other implications.

(Saleem et al., 2016) have described the use of WQI method of interpretation of groundwater quality, declaring it a fast, easy, and composite method. Similarly, (Pant et al 2023) have applied and WQI for river water quality analysis in India and found that this is a suitable method to characterize the water quality.

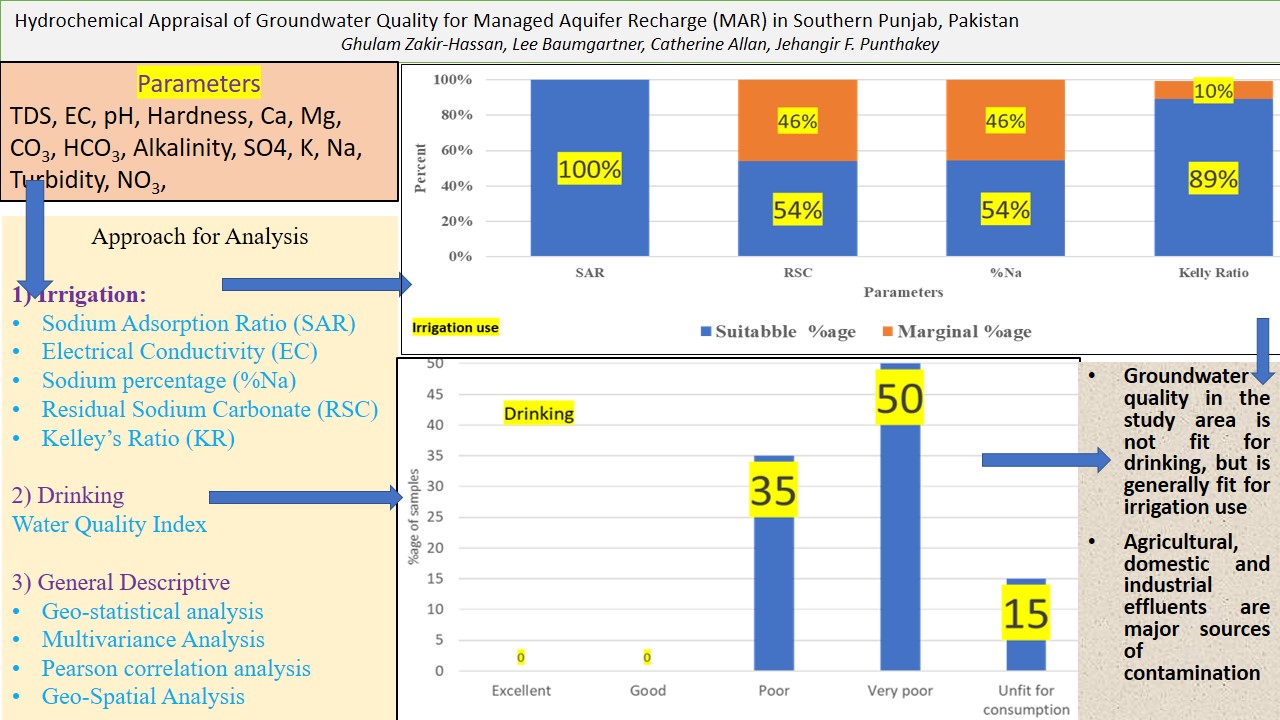

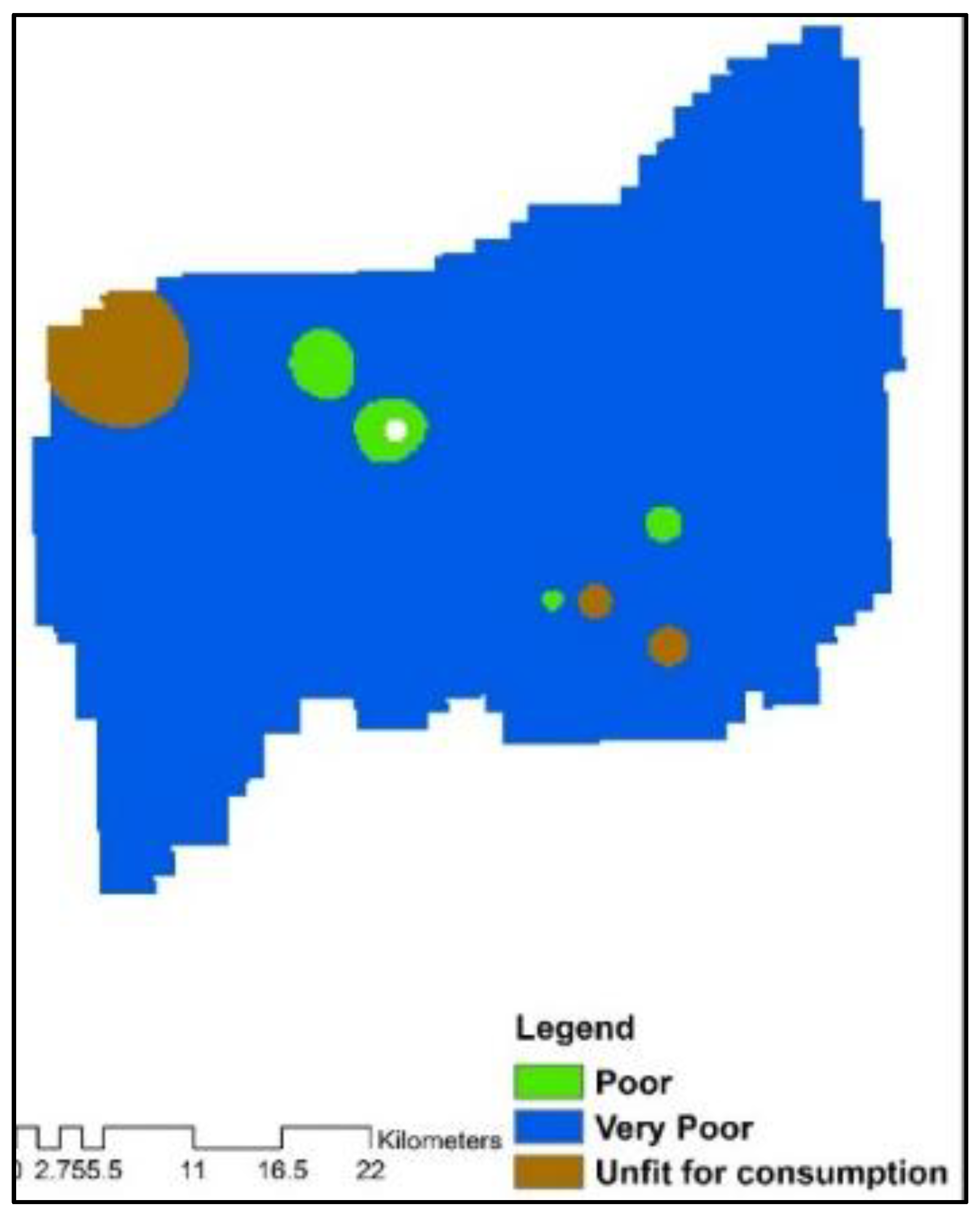

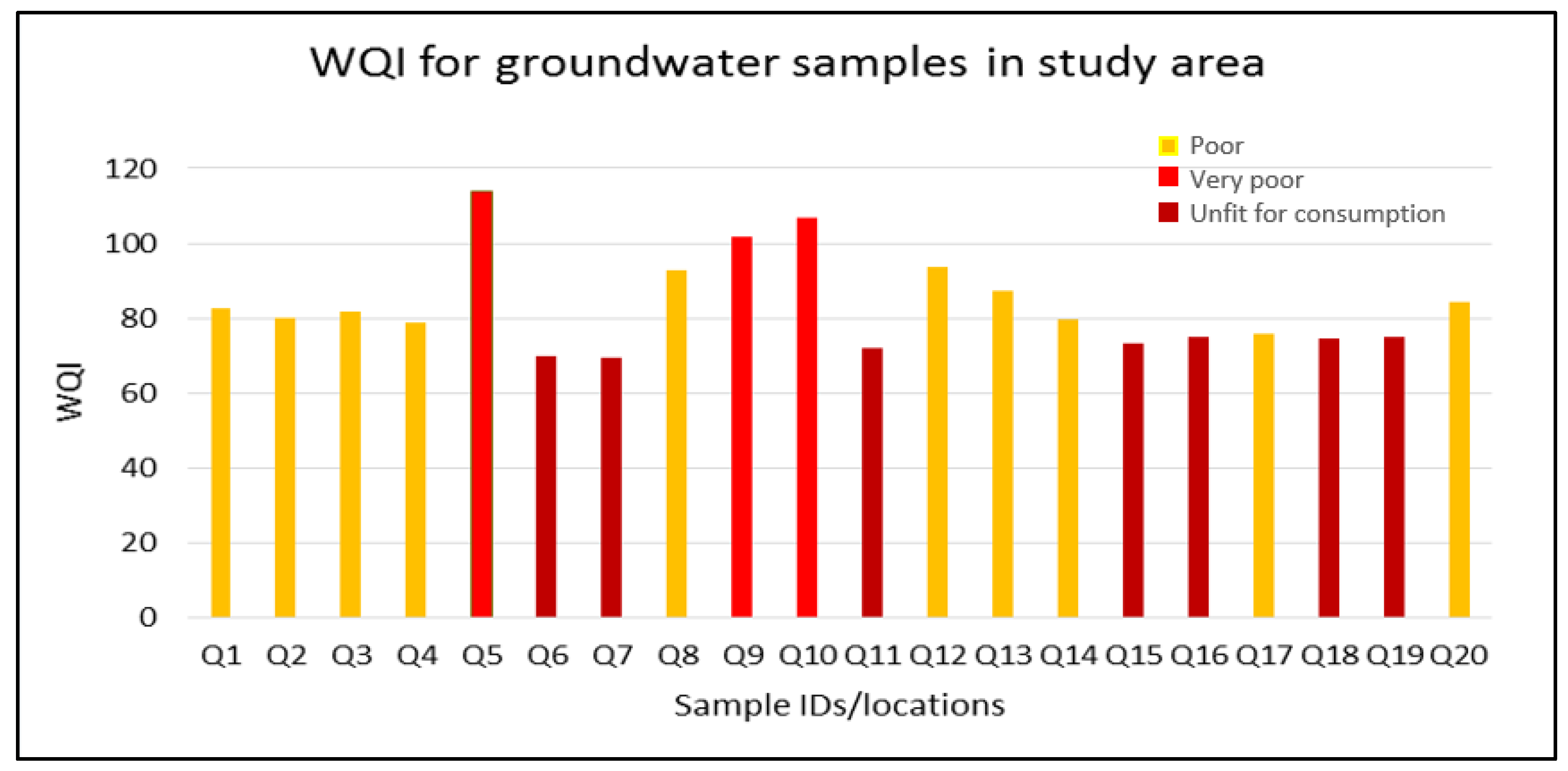

Table 4 depicts the classification of water for drinking and results of groundwater analysis in the study area. Geospatial plot of WQI interpolated into the whole study area is plotted in

Figure 5 and the values of WQI for individual sampled wells are depicted in

Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Plot of WQI depicting suitability of groundwater for drinking using IDW.

Figure 5.

Plot of WQI depicting suitability of groundwater for drinking using IDW.

Figure 6.

Water quality index for groundwater samples in study area.

Figure 6.

Water quality index for groundwater samples in study area.

WQI reflects the integrated effect of measurements obtained for individual element. There is a part of catchment in which many individual elements are not suitable for quality assessment. Integration of individual elements into a single index – WQI - suggests that there are no parts of existing aquifer that has water in a better condition than “poor”. It was revealed that 35% samples fall under poor, 50% under very poor, and 15% under unfit for consumption class and none of sample falls under the class I and II (excellent and good) of WQI as depicted in

Table 4. As such, it is concluded that groundwater in the aquifer is not suitable for human consumption. Tube well 5 exists in the vicinity of Vehari city, where the water quality is unfit for consumption (Fig 6) and is not suitable for drinking. Similarly, the other two wells (Q9 and Q10), which too exhibit the groundwater unsuitable for drinking, fall in the vicinity Ludden. Ludden is a bigger, populated rural center which seems to be a source of contamination for groundwater. It is concluded that apparently the municipal effluents are the source of groundwater contamination, as the points falling under class V of WQI are located near the populated localities. Other wells falling under comparatively more populated centers. The rest of the wells showing the adverse quality are located near the Sukh Beas Drain (SBD) passing through the study area.

Human health may face sever issues due to consumption of this contaminated water (Amarachi et al 2023). Contaminated groundwater in an aquifer may cause adverse impacts on the human health in the nearby surrounding areas as well (Bento et al 2023). In the study area, as groundwater is not suitable for human consumption, the health of the population in the area is at risk. Therefore, proper monitoring, evaluation, and management of water quality is of paramount importance. Similar findings have been reported by (Iqbal et al 2021).

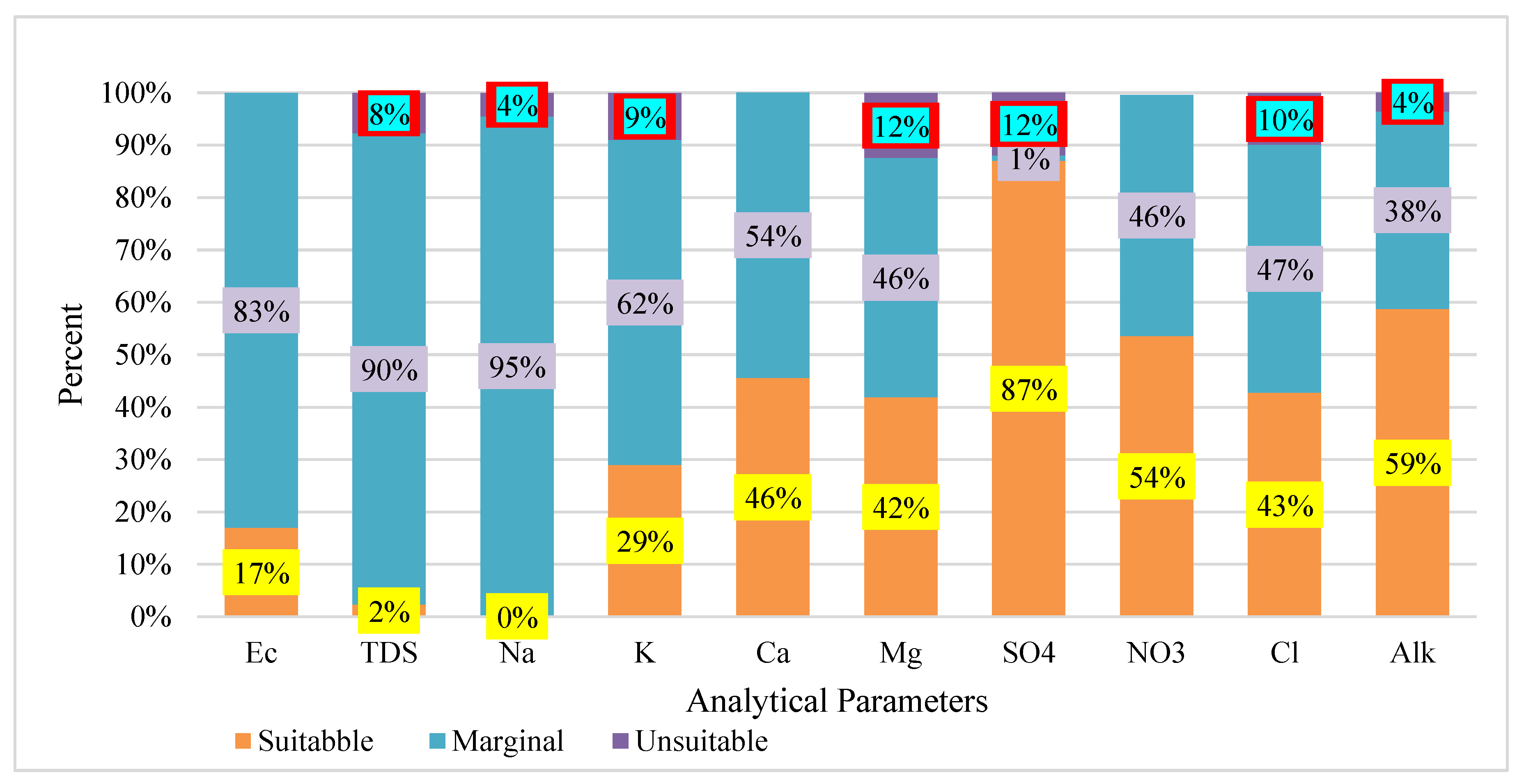

3.6. Suitability of Groundwater for Irrigation

Groundwater quality for irrigation purposes has been evaluated by analyzing the values of individual analytical parameters and by calculating some integrated parameters. Three classes viz: suitable, marginal and un-suitable have been used on the basis of WHO and PID standards for suitability of groundwater for irrigation (WHO 2011; Zakir-Hassan et al 2023).

Table 5 presents the results of groundwater suitability for irrigation on the basis of individual parameters and calculated analytical parameters including SAR, %Na, KR and RSC. Areas falling under different classes of groundwater fitness have also been tabulated.

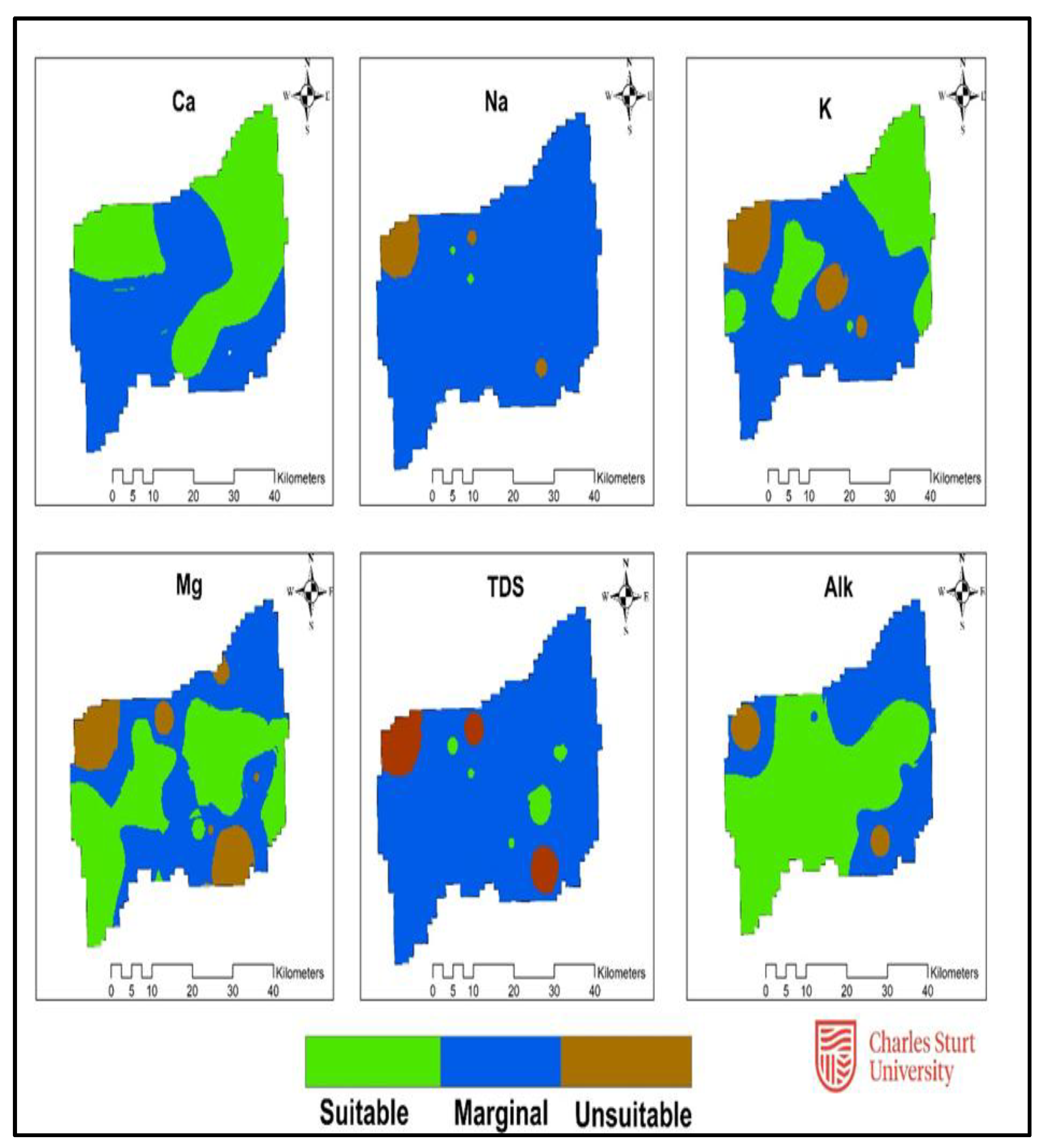

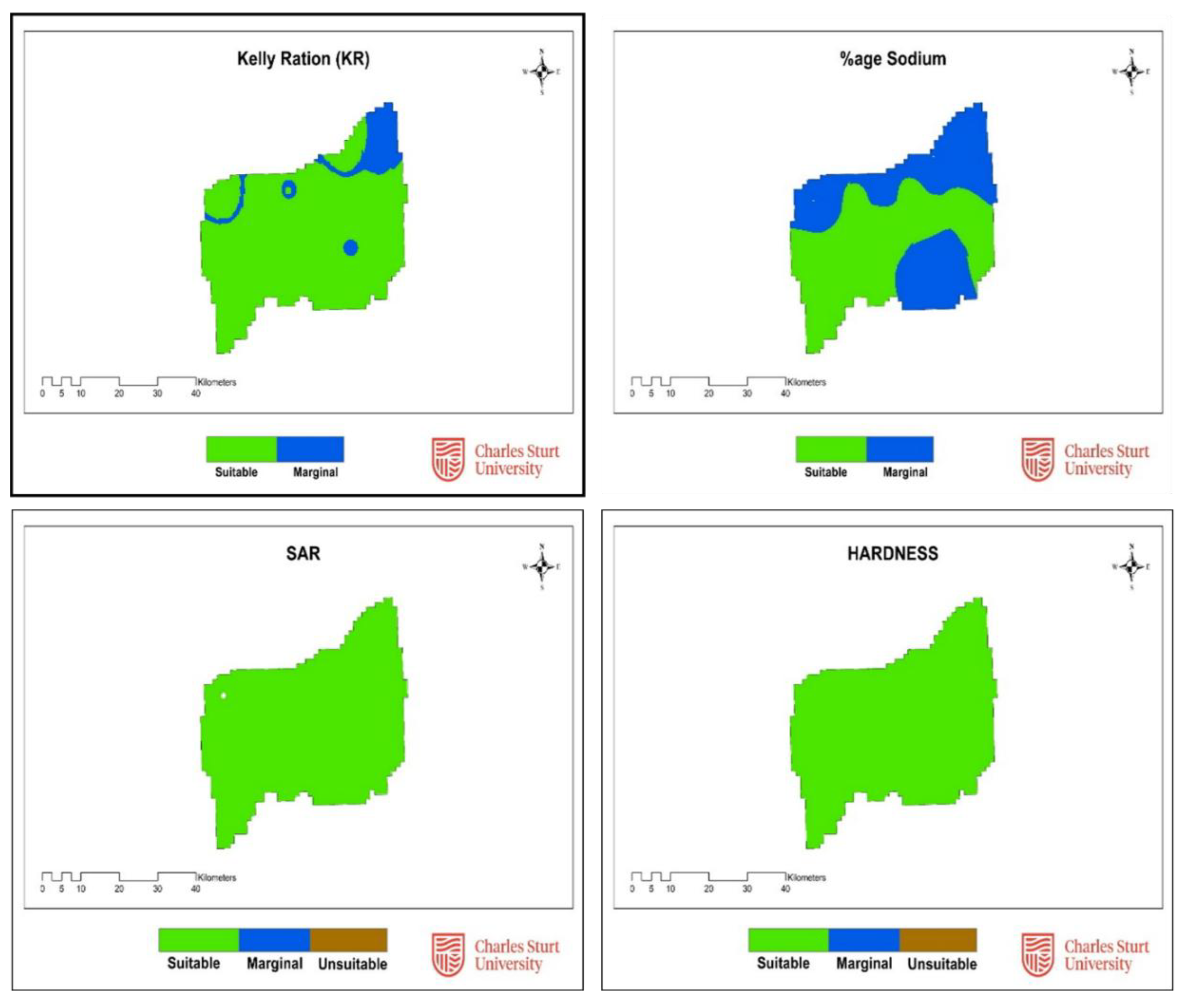

Results of different individual parameters have been plotted to examine the spatial trends/patterns within the study area as.

Figure 7 depicts some of geo-spatial distribution of Ca, Na, K, Mg, TDS and Alk, while the

Figure 8 shows the patterns for KR, %Na, SAR, and hardness in the study region.

Figure 7.

Geo-spatial distribution of analytical parameters groundwater samples for irrigation use using IDW.

Figure 7.

Geo-spatial distribution of analytical parameters groundwater samples for irrigation use using IDW.

Figure 8.

Geo-spatial of KR, %Na, SAR, hardness for groundwater samples for irrigation use by applying IDW.

Figure 8.

Geo-spatial of KR, %Na, SAR, hardness for groundwater samples for irrigation use by applying IDW.

Geospatial patterns (Fig 7) indicate that groundwater quality is generally suitable or marginal for irrigation application in the study area, however, there are some hotspots in the surrounding areas of Vehari city, which reflects that urban center is a source for groundwater contamination. Some other scattered locations also indicate the hotspots for groundwater quality near SBD and Ludden (a well-populated rural center of around 20000 persons). A small percentage of area up to 12% of the catchment contains water unsuitable for irrigation according to TDS, Na, K, Mg, SO

4, C; or Alk (

Table 5 & Fig 7).

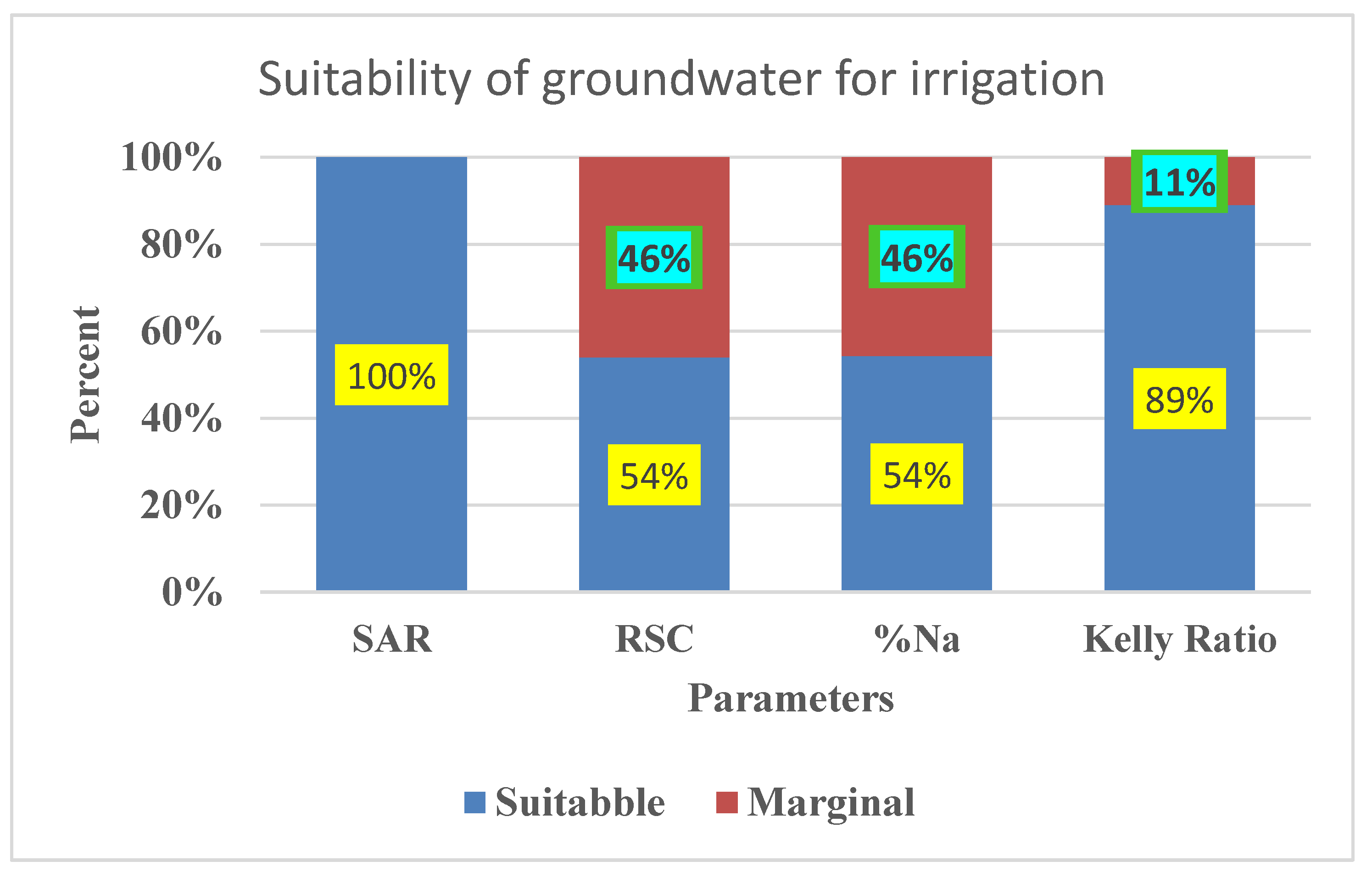

It is noted that most of the area is either suitable or marginal for irrigation uses (Fig 8) on the basis of SAR, Hardness, %Na, and KR values. The significant value is shown in SAR in which 100 % of area lies in suitable class. Other parameters also indicate that groundwater is generally suitable for irrigation.

Figure 9 represents similar results for suitability of groundwater for irrigation on the basis of analytical parameters; which indicates that most the groundwater falls under the suitable and the marginal class. This too derives the findings that generally groundwater in the study area is suitable for irrigation.

Additionally, some integrated parameters have also been calculated and plotted (

Table 5, Fig 8) for evaluation and interpretation of groundwater quality for irrigation uses in the study area, which include %Na, KR, SAR, and RSC as shown in

Figure 10. These parameters use the different individual elements and depict the overall picture of water quality for irrigation. These plots have revealed that groundwater quality in most of the part in the study area is suitable, and some patches fall under marginal categories. This also confers that groundwater in the aquifer is generally suitable for irrigation application except few spots near Vehari city, Ludden (an urban locality), and the SBD which passes through the study area.

Due to high value of SAR (excessive Na), the soil becomes hard and compact when dry and resultantly, reduces the infiltration rates of water and air into the soil affecting its structure (Munkholm, 2011). This results in low recharge rates in the soils with high values of SAR (Hopkins et al., 2007). This problem is also related with several other factors such as the salinity rate and type of soil. For example, sandy soils may not get damaged as easily as other type of soils (such as clay) when it is irrigated with a high SAR water (Zakir-Hassan, 2023).

It has been found that the dominant salt in groundwater in study area is Na, whose presence beyond permissible limits can pose the adverse impact when groundwater is used for irrigation. Uses of Na-excessive groundwater for irrigation purpose will cause accumulation of more salts (Na dominant) in the soil which affects the hydraulic conductivity (permeability) of soil and creates water infiltration problems. This is because when more Na is present in the soil in exchangeable form, it replaces Ca and Mg, adsorbed on the soil clays and makes the soil hard and cloddy when it is dry. While Ca and Mg cause dispersion of soil particles; i.e., if Ca and Mg cations are adsorbed on the soil exchange complex, the soil structure tends to improve as these cations stabilize soil aggregates, resulting in permeable and granular structure. This ultimately makes the soil more conducive to cultivation (Hopkins et al., 2007). Therefore, it is important to study what is composition of salts in groundwater and how salt and water interact with each other in root zone during irrigation. Excessive accumulation of Na is termed as soil sodicity which causes the degradation soil structure especially in clayey and loamy soils (van der Zee et al., 2014). Soil sodicity reduces the infiltration rates and increases the runoff causing the soil erosion (Wiesman, 2009).

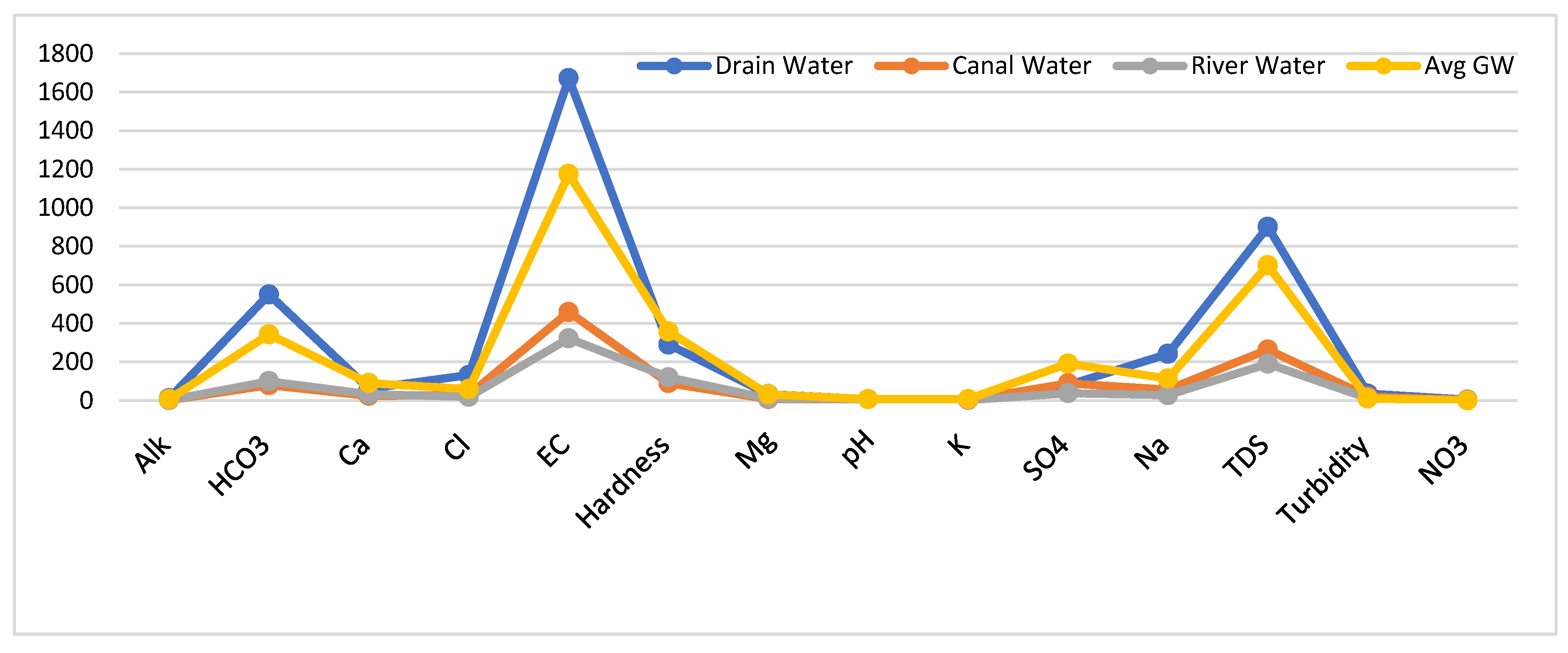

The average groundwater quality was compared with surface waters sampled from drain, river and canal in the study area water samples as shown in

Figure 11.

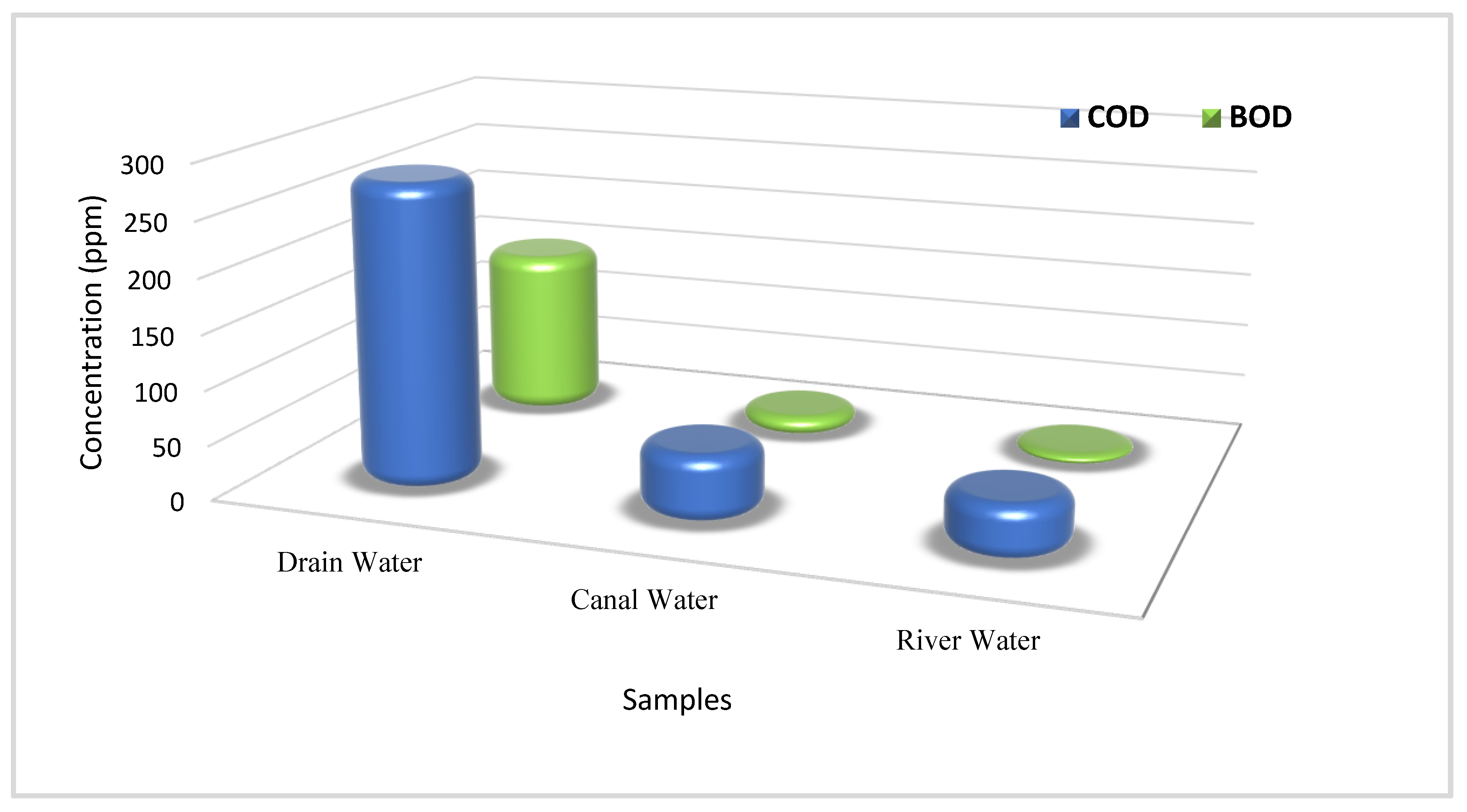

As shown if

Figure 11, the EC values for drain water are the highest followed by in groundwater. It indicates that drain passing through the study area is the source of pollution for groundwater. Order of quality of different water is River > Canal > Groundwater > drain water. Similarly, BOD and COD for canal, river, and drain water have also been compared (

Figure 12). Comparison of drain, river and canal water yielded the order of River > Canal > Drain. This implies that drainage water quality is the worst among all including groundwater, which warns about the contamination of land and water by drainage effluents.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

This research prescribes a benchmark survey and investigation on groundwater water quality situation in the study area which is important for the MAR project, which is being implemented by PID to improve the depleting groundwater levels. After implementation of MAR project, the quality of groundwater in the area can be re-assessed to evaluate the impact of MAR. This can help in future implementation of MAR projects in similar areas in IRB and other regions.

Groundwater quality has been compared with the available water for MAR (river water), which has been found better. Through this finding, it can be anticipated that MAR project of PID can improve the quality of groundwater in the study area. However, aviod the excessive use of groundwater for irrigation must be avoided as it may cause the problem of sodification in soil which may hamper the infiltartion rates posing adverse impacts on MAR project. Farming community may be advised for suitable mangement interventions for groundwater quality incluidng conjunctive use, application of chemical like gypsum.

In addition, the study provides the extent of suitability of groundwater for irrigation purposes and domestic uses. Results have revealed that groundwater in the study area is generally suitable for irrigation but unfit for drinking. Regular direct use of groundwater may pose adverse effects on human health. Therefore, groundwater may be used for human consumption after filtration or other treatment to avoid the threatsto the community’s well being.

Groundwater quality for irrigation use is although generally suitable, but hotspots are there near urban centers and the Sukh Beas Drain, which indicates that domestic effluents from the urban centers are putting negative influence on the groundwater. Treatment of any type of effluent must be made mandatory to mitigate the threats for land and water resources in the area.

Findings of the study can be helpful in decision making regarding designing and implementation MAR projcets and planing for groundwater management including protection of aquifer in the area for sustainable and integrated water resources planning. Planning for protection of groundwater quality must be ensured.

For any MAR project the water quality of both source and sink play a vital role and must be evaluated and anticipated well before implementation of the projects on the ground. If source water is contaminated it may pollute the aquifer and, similarly, recharging the contaminated aquifers will be futile exercise. In addition to this aspect, another important dimension of water quality threats for MAR are the anticipated reaction of recharged water with the porous media through which the water flows through during the recharge process (Zakir-Hassan et al 2023). Geological material of the aquifer also plays a significant role in the resultant water quality after implementation of MAR projects.

Funding

Study has been carried out as a PhD project supported by Australian Government Research Training Program (AGRTP) scholarship at Charles Sturt University, Australia; which is acknowledged.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data relevant to this research has been made part of this paper. However, any further details or information can be obtained from the corresponding author on special request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are extended to the field formation of PID for support in sample collection; IRI and PCRWR for sample analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Adimalla, N. (2020). Controlling factors and mechanism of groundwater quality variation in semiarid region of South India: an approach of water quality index (WQI) and health risk assessment (HRA). Environ Geochem Health, 42(6), 1725-1752. [CrossRef]

- Adimalla, N. (2021). Application of the Entropy Weighted Water Quality Index (EWQI) and the Pollution Index of Groundwater (PIG) to Assess Groundwater Quality for Drinking Purposes: A Case Study in a Rural Area of Telangana State, India. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol, 80(1), 31-40. [CrossRef]

- Adimalla, N., & Qian, H. (2019). Groundwater quality evaluation using water quality index (WQI) for drinking purposes and human health risk (HHR) assessment in an agricultural region of Nanganur, south India. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 176, 153-161. [CrossRef]

- Adimalla, N., & Taloor, A. K. (2020). Hydrogeochemical investigation of groundwater quality in the hard rock terrain of South India using Geographic Information System (GIS) and groundwater quality index (GWQI) techniques. Groundwater for Sustainable Development, 10. [CrossRef]

- Amarachi, N., Austin, T., Michael, O., Bilar, A. and Christopher, A., 2023. Quality assessment and health impact of bottled water in Uratta, Imo state: a retrospective study. Sustainable Water Resources Management, 10(1): 3 https://. [CrossRef]

- APHA. (2021). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water 23rd Ed: American Public Health Association (APHA). Retrieved from https://secure.apha.org/imis/ItemDetail?iProductCode=978-087553-2875&CATEGORY=BK.

- Barry, K., Vanderzalm, J., Miotlinski, K., & Dillon, P. (2017). Assessing the Impact of Recycled Water Quality and Clogging on Infiltration Rates at A Pioneering Soil Aquifer Treatment (SAT) Site in Alice Springs, Northern Territory (NT), Australia. Water, 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Bento, S., Melo, M.T.C.d. and Gramaglia, C., 2023. Ethical reflections on groundwater in contaminated areas. Sustainable Water Resources Management, 10(1): https://. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. M., McClelland, N. I., Deininger, R. A., & O’Connor, M. F. (1972). A water quality index—crashing the psychological barrier. In Indicators of Environmental Quality: Proceedings of a symposium held during the AAAS meeting in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, December 26–31, 1971 (pp. 173-182). Springer US.

- Chin DA (2013) Water-quality engineering in natural systems: fate and transport processes in the water environment. John Wiley and Sons.

- Custodio E (2012). Low Llobregat aquifers: intensive development, salinization, contamination, and management. The Llobregat: The Story of a Polluted Mediterranean River. 2012:27-49.

- Davis ML (2010) Water and Wastewater Engineering. McGraw Hill.

- Dillon, P., Gale, I., Contreras, S., Pavelic, P., Evans, R., & Ward, J. (2009). Managing aquifer recharge and discharge to sustain irrigation livelihoods under water scarcity and climate change. IAHS Publ. 330, IAHS, Wallingford, UK, pp 1–12.

- EPA_Victoria. (2009). Guidelines for managed aquifer recharge (MAR) – Health and environmental risk management. Retrieved from www.epa.vic.gov.au/publications.

- Gao, Y., Qian, H., Ren, W., Wang, H., Liu, F., & Yang, F. (2020). Hydrogeochemical characterization and quality assessment of groundwater based on integrated-weight water quality index in a concentrated urban area. Journal of Cleaner Production,260(121006). [CrossRef]

- GOP. (2018). Pakistan-Economic Survey 2017-18: Economic Adviser’s Wing, Finance Division, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad, Pakistan. Retrieved from www.finance.gov.pk.

- Hopkins, B. G., Horneck, D. A., Stevens, R. G., Ellsworth, J. W., & Sullivan, D. M. (2007). Managing irrigation water quality for crop production in the Pacific Northwest: PNW 597-E; A Pacific Northwest Extension publication, Oregon State University • University of Idaho • Washington State University, USA. Retrieved from https://brightspotcdn.byu.edu/4b/6f/c34da4954078a51620833c51773d/managing-irrigation-water-quality.pdf.

- Hossain, M. I., Bari, M. N., Miah, S. U., Jahan, C. S., & Rahaman, M. F. (2019). Performance of MAR model for stormwater management in Barind Tract, Bangladesh. Groundwater for Sustainable Development, 10 (100285) . [CrossRef]

- Iqbal Z, Abbas F, Mahmood A, Ibrahim M, Gul M, Yamin M, Aslam B, Imtiaz M, Elahi NN, Qureshi TI, Sial GZ (2021) Human health risk of heavy metal contamination in groundwater and source apportionment. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 19(2022): 7251–7260.

- Kumar L, Kumari R, Kumar A, Tunio IA, Sassanelli C (2023) Water Quality Assessment and Monitoring in Pakistan: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability, 15(7) https://. [CrossRef]

- Leslie, D. L., Reba, M. L., & Czarnecki, J. B. (2022). Managed aquifer recharge using a borrow pit in connection with the Mississippi River Valley alluvial aquifer in northeastern Arkansas. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 77(6). [CrossRef]

- Kelly WP (1963). Use of saline irrigation water. Soil Science,95, 355–391. https://. [CrossRef]

- Malik, A., & Sugandh. (2022). Groundwater hydro-geochemistry, irrigation and drinking quality, and source apportionment in the intensively cultivated area of Sutlej sub-basin of main Indus basin. Environmental Earth Sciences, 81, 456.

- Munkholm L (2011). Soil friability: A review of the concept, assessment and effects of soil properties and management. Geoderma, s 167–168. 236–246. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2011.08.005.

- Mohan, U., & Krishnakumar, A. (2021). Geospatial distribution of groundwater quality using entropy water quality index and statistical assessment: A study from a tropical climate river basin. Environmental Quality Management. [CrossRef]

- Natasha, N., Shahid, M., Murtaza, B., Bibi, I., Khalid, S., Al-Kahtani, A. A., . . . Shaheen, S. M. (2022). Accumulation pattern and risk assessment of potentially toxic elements in selected wastewater-irrigated soils and plants in Vehari, Pakistan. Environ Res, 214(Pt 3), 114033. [CrossRef]

- Nisa, Z.-U. (2018). GIS Based Evaluation of Groundwater Quality of Western Lahore Using Water Quality Index. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 55(03), 653-665. [CrossRef]

- Page, D., Dillon, P., Vanderzalm, J., Toze, S., Sidhu, J., Barry, K., . . . Regel, R. (2010). Risk assessment of aquifer storage transfer and recovery with urban stormwater for producing water of a potable quality. J Environ Qual, 39(6), 2029-2039. [CrossRef]

- Palit, D., Mondal, S., & Chattopadhyay, P. (2018). Analyzing water quality index of selected pit–lakes of Raniganj coal field area, India. Environ Ecol, 36(August).

- Pant M, Singhal N, and Singh J (2023) Spatio-temporal variations in water quality of Rispana river in Dehradun, India. Sustainable Water Resources Management, 9(4): 123 https://. [CrossRef]

- Pavelic, P., Hoanh, C. T., D’haeze, D., Vinh, B. N., Viossanges, M., Chung, D. T., . . . Ross, A. (2022). Evaluation of managed aquifer recharge in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 44 (101257). [CrossRef]

- Richards LA (Ed.) (1954) Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils (No. 60). US Government Printing Office.

- Ross, A. (2022). Benefits and Costs of Managed Aquifer Recharge: Further Evidence. Water, 14(20). [CrossRef]

- Ruhela, M., Singh, V. K., & Ahamad, F. (2021). Assessment of groundwater quality of two selected villages of Nawada district of Bihar using water quality index. Environment Conservation Journal, 22(3), 387-394. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M., Hussain, A., Mahmood, G., & Dubey, S. (2016). Analysis of groundwater quality using water quality index: A case study of greater Noida (Region), Uttar Pradesh (U.P), India. Cogent Engineering, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G., Lata, R., Thakur, N., Bajala, V., Kuniyal, J. C., & Kumar, K. (2021). Application of Multivariate Statistical Analysis and Water Quality Index for Quality Characterization of Parbati River, Northwestern Himalaya, India. research Square. [CrossRef]

- Sherif, M., Sefelnasr, A., Al Rashed, M., Alshamsi, D., Zaidi, F. K., Alghafli, K., . . . Ebraheem, A. A. (2023). A Review of Managed Aquifer Recharge Potential in the Middle East and North Africa Region with Examples from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Water, 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Panda SN, Kumar KS, Sharma CS (2013) Artificial groundwater recharge zones mapping using remote sensing and GIS: a case study in Indian Punjab. Environmental management, 52:61-71.

- Singh J, Bhardwaj P, and Awasthi A, (2022) Health implications among school children due to fluoride in underground aquifers of Haryana state, India. Environmental Quality Management, 31(3): 233-240 https://. [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, A. S. (2010). District Vehari: Hazard, vulnerability and development profile: Rural Development Policy Institute (RDPI), Islamabad, Pakistan.

- Snousy, M. G., Wu, J., Su, F., Abdelhalim, A., & Ismail, E. (2021). Groundwater Quality and its Regulating Geochemical Processes in Assiut Province, Egypt. Exposure and Health. [CrossRef]

- Solangi, G. S., Siyal, A. A., Babar, M. M., & Siyal, P. (2019). Evaluation of drinking water quality using the water quality index (WQI), the synthetic pollution index (SPI) and geospatial tools in Thatta district, Pakistan. Desalination and Water Treatment, 160, 202-213. [CrossRef]

- Srinidhi, N. S., Madhusudhana Reddy, P., & Anji Reddy, M. (2021). Evaluation of Water Quality Status of Ameenpur Lake, Hyderabad, Telangana, India Using Water Quality Index (Wqi) and Geo-Spatial Technology. Plant Archives, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, S. E. A. T. M., Shah, S. H. H., & Vervoort, R. W. (2014). Root zone salinity and sodicity under seasonal rainfall due to feedback of decreasing hydraulic conductivity. Water Resources Research, 50(12), 9432-9446. [CrossRef]

- Vanderzalm, J. L., Dillon, P. J., Tapsuwan, S., Pickering, P., Arold, N., Bekele, E. B., . . . McFarlane, D. (2015). Economics and experiences of managed aquifer recharge (MAR) with recycled water in Australia: Australian Water Recycling Centre of Excellence. Retrieved from https://vuir.vu.edu.au/32058/1/MARRO%2BCase%2BStudies%2B-%2BFinal%2BReport.pdf.

- Wang H, Zhang Q (2019) Research Advances in Identifying Sulfate Contamination Sources of Water Environment by Using Stable Isotopes. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 30;16(11):1914. [CrossRef]

- WHO-Edition Fourth (2011) Guidelines for drinking-water quality. WHO chronicle, 38(4):104-8.

- Wiesman, Z. (2009). Biotechnologies for intensive production of olives in desert conditions: in Desert Olive Oil Cultivation; https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/soil-sodicity.

- Wilcox, L. V. (1955). Classification and use of irrigation water (p. 19). Washington: U.S. Department of Agriculture Circular 969.

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Hassan, F. R., Punthakey, J. F., & Shabir, G. (2021). Challenges for groundwater-irrigated agriculture and management opportunities in Punjab province of Pakistan. International Journal of Research in Agronomy, 4(2), 142-153.

- Zakir-Hassan, G. (2023). Improving Sustainable Groundwater Management: A Case Study of Managed Aquifer Recharge in Punjab Pakistan: PhD thesis, School of Agricultural, Environmental, and Veterinary Sciences Charles Sturt University, Australia,.

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Allan, C., Punthakey, J. F., Baumgartner, L., & Ahmad, M. (2023). Groundwater Governance in Pakistan: An Emerging Challenge. In M. Ahmad (Ed.), Water Policy in Pakistan: Issues and Options (pp. 143-180). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Akhtar, S., Punthakey, J.F. and Shabir, G., 2022. Assessnment of groundwater potential and threats for its sustainable use, case study of Greater Thal Canal area from Punjab Pakistan: . Water Productivity Journal, 2(4): 53-71.

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Hassan, F. R., Punthakey, J. F., Shabir, G., & Khan, M. A. H. (2022). Groundwater Contamination from Drainage Effluents in Punjab Pakistan. Journal of Agricultural Research Pesticides and Biofertilizers, 4(1).

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Hassan, F. R., Shabir, G., & Rafique, H. (2021). Impact of Floods on Groundwater—A Case Study of Chaj Doab in Indus Basin of Pakistan. International Journal of Food Science and Agriculture, 5(4), 639-653. [CrossRef]

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Kahlown, M. A., Punthakey, J. F., Shabir, G., Aziz, M., Sultan, M., . . . Majeed, F. (2023). Evaluation of hydraulic efficiency of lined irrigation channels – A case study from Punjab, Pakistan. Hydrology Research, 54(4), 523-546. doi:http://iwaponline.com/hr/article-pdf/54/4/523/1211072/nh0540523.pdf.

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Punthakey, J. F., Allan, C., & Baumgartner, L. (2025). Integrating Groundwater Modelling for Optimized Managed Aquifer Recharge Strategies. Water, 17(14). [CrossRef]

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Punthakey, J. F., Hassan, F. R., & Shabir, G. (2022). Methodology for Identification of Potential Sites for Artificial Groundwater Recharge in Punjab Province of Pakistan. Canadian Journal of Agriculture and Crops, 7(2), 46-77. [CrossRef]

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Punthakey, J. F., Hassan, F. R., Shabir, G., & Khan, M. A. H. (2022). Groundwater Contamination by wastewater _ a threat for human–heath In Punjab Pakistan. . Medpress Nutrition and Food Sciences, 1(1). doi:https://www.medpresspublications.com/articles/mpnfs/mpnfs-202207001.pdf.

- Zakir-Hassan, G., Punthakey, J. F., Shabir, G., & Hassan, F. R. (2024). Assessing the potential of underground storage of flood water: A case study from Southern Punjab Region in Pakistan. Journal of Groundwater Science and Engineering, 12(4), 387-396. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).