Introduction

Modern statistical methods enable the detection of anomalies that precede major earthquakes. Such anomalies can be identified even from simple records, including time and magnitude (Konishi, 2025d). For earthquakes of magnitude 6–7, some degree of prediction appears feasible, provided that such records are available (Konishi, 2025a). Precursor swarms are frequently observed prior to large events, and their identification—alongside anomalous magnitude distributions—may offer valuable insights into seismic hazard.

Historically, seismological research has not fully incorporated these modern statistical approaches. As a result, certain empirical laws—such as the Gutenberg–Richter law for magnitude distribution (Gutenberg and Richter, 1944) and the Omori formula for aftershock decay (Omori, 1895; Utsu, 1957; Utsu et al., 1995) —remained widely accepted for decades, despite mounting evidence of their limitations (Konishi, 2025d, c). While these models have played a foundational role in the development of seismology, their continued use without critical re-evaluation may hinder progress. Accordingly, research grounded in such assumptions should be interpreted with caution, particularly when drawing conclusions about earthquake mechanisms.

The principal difficulty is that the recorded data are often extremely voluminous, making regional examination laborious (JMA, 2025c, d; Konishi, 2025a). In addition, the administrative areas defined by local authorities are typically irregular in shape (JMA, 2025e). As earthquakes can occur at any time, continuous monitoring is essential, yet maintaining such monitoring across an entire country, such as Japan, is particularly demanding.

Materials and Methods

Data

Comprehensive seismic source data were employed. These consist of CSV-formatted records of earthquake date and time, epicentre location, and magnitude, organised annually (JMA, 2025c, f). As compilation requires several years, the most recent dataset available as of November 2025 is from 2022 (JMA, 2025c). More recent data are available (JMA, 2025f), but these are organised daily, making download cumbersome; therefore, sampling at intervals of several days was applied. Monthly reports are also published, but these are provided as PDF files, rendering extraction laborious (JMA, 2025g, d). The comprehensive catalogue includes lower magnitudes than the monthly reports.

Grid Construction

Date, location, and magnitude were extracted from the seismic dataset. To facilitate spatial analysis, the entire Japanese archipelago was partitioned into a grid composed of 1° latitude by 1° longitude cells. Each cell was treated as a discrete unit, and the corresponding magnitude records were aggregated accordingly. The grid was visualised as a mosaic of rectangular tiles; although the longitudinal span of each tile decreases with increasing latitude, this division was adopted primarily for practical reasons.

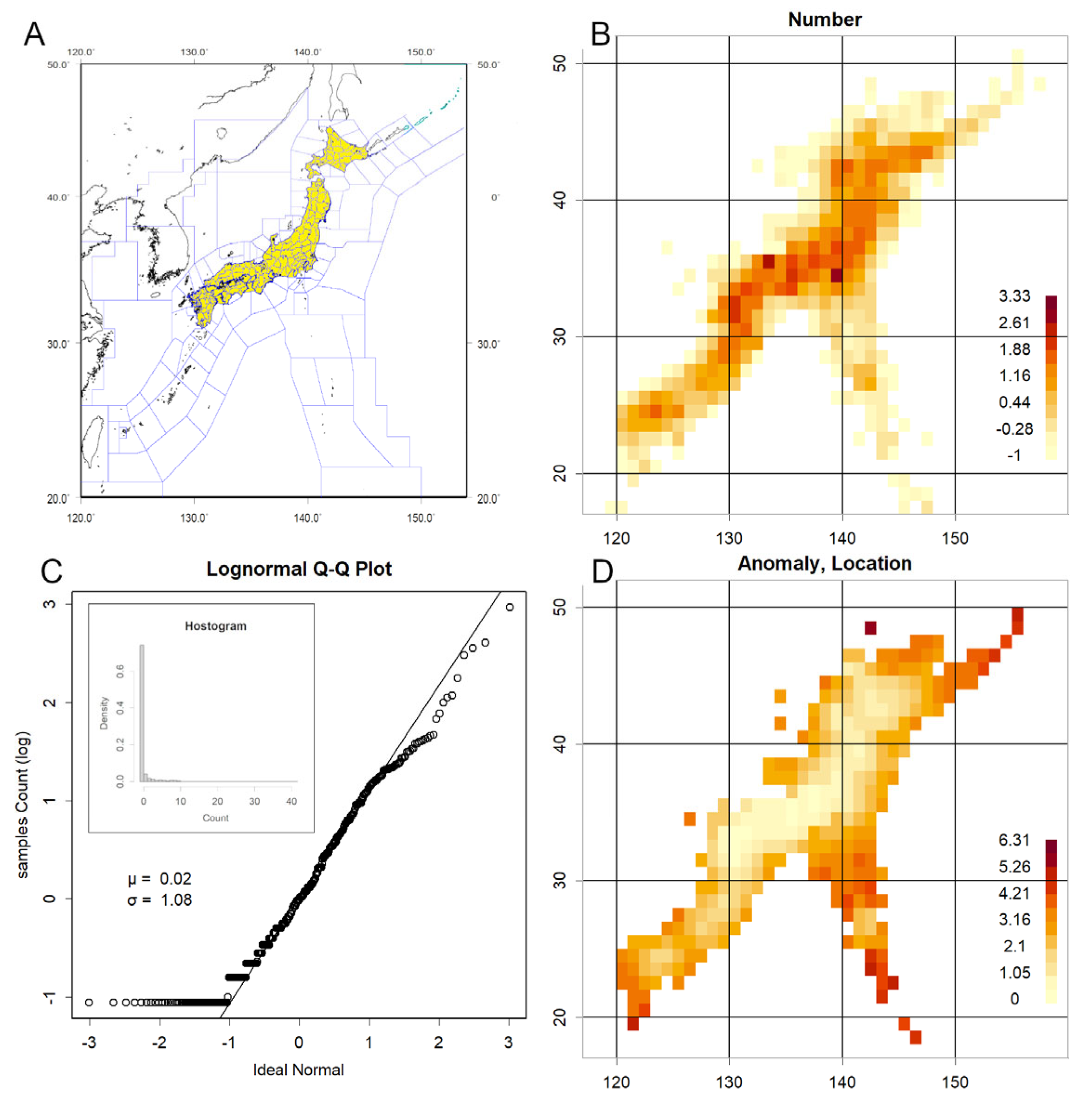

The choice of a 1° resolution was guided by several considerations. First, it aligns naturally with the coordinate format of epicentre records, which are typically reported in degrees. Second, it proved compatible with standard plotting functions in R, enabling efficient visualisation. Most importantly, this resolution provided a suitable balance between spatial granularity and data completeness. As illustrated in

Figure S5, this would be the finest resolusion; attempts to increase the resolution to 0.5° resulted in numerous empty cells, particularly in regions with lower seismic activity. Conversely, coarser grids—such as 4°—led to excessive spatial aggregation, with single tiles encompassing vast areas (e.g., one tile covering nearly the entirety of Hokkaido), thereby obscuring localised patterns.

The 1° grid thus emerged as an empirically optimal resolution for Japan, offering sufficient detail without compromising data coverage. For regions with lower seismic frequency, coarser grids may be more appropriate. Additionally, in high-latitude areas where longitudinal convergence becomes significant, adjustments such as doubling or tripling the longitudinal span may be warranted.

Should finer resolution be desired, a sliding window approach could be employed by shifting the grid in 0.1° increments and averaging the resulting 100 outputs. The R code has been designed to accommodate such operations; however, this would entail a substantial increase in computational time—potentially requiring several days to generate a single averaged image. For this reason, such an approach was not pursued in the present study.

Statistical Analysis

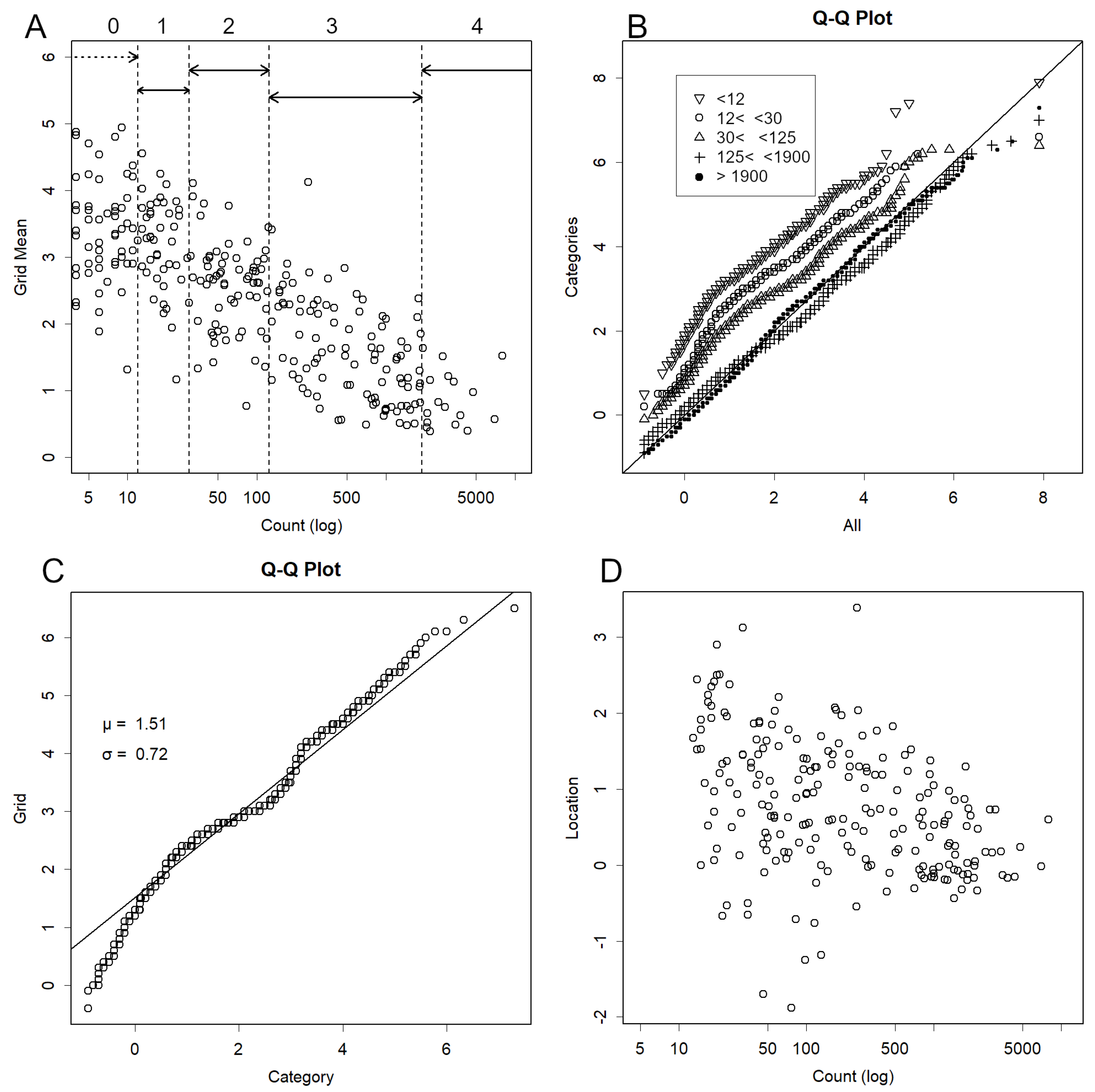

The number of epicentres in each grid was recorded. For each grid, a quantile–quantile (QQ) plot was generated, comparing magnitudes within the grid against magnitudes across multiple grids as background (Konishi, 2025a, d; Tukey, 1977). This yielded a linear relationship, from which the intercept (location) and slope (scale) were recorded.

Magnitudes in monthly reports follow a normal distribution (Konishi, 2025d), whereas the comprehensive catalogue differs slightly (Konishi, 2025a). The lower frequency of very small magnitudes introduces curvature in the relationship, leading to deviations in mean or standard deviation estimates. To standardise the data, QQ plots were employed to determine parameters, thereby assessing whether the distribution in a given grid deviated significantly from the majority.

Error Estimation

Parameter estimation with small sample sizes introduces substantial error. For example, when estimating location from sample data, the error is known to be (Stuart and Ord, 1994). To investigate error in QQ plots, simulations were conducted. Random samples were drawn, QQ plots generated, and values calculated. Sample size was increased from 2 to 400 to examine estimation behaviour.

Normalisation

In the actual data, smaller counts tended to correspond to larger mean magnitudes. To account for this, grids were divided into five categories based on count, and measurements were performed accordingly. The QQ plot used to determine parameters employed the full dataset for the category to which the grid belonged as background. QQ plots were also conducted for counts, location, and scale against well-known distribution forms to investigate distribution patterns.

Case Studies

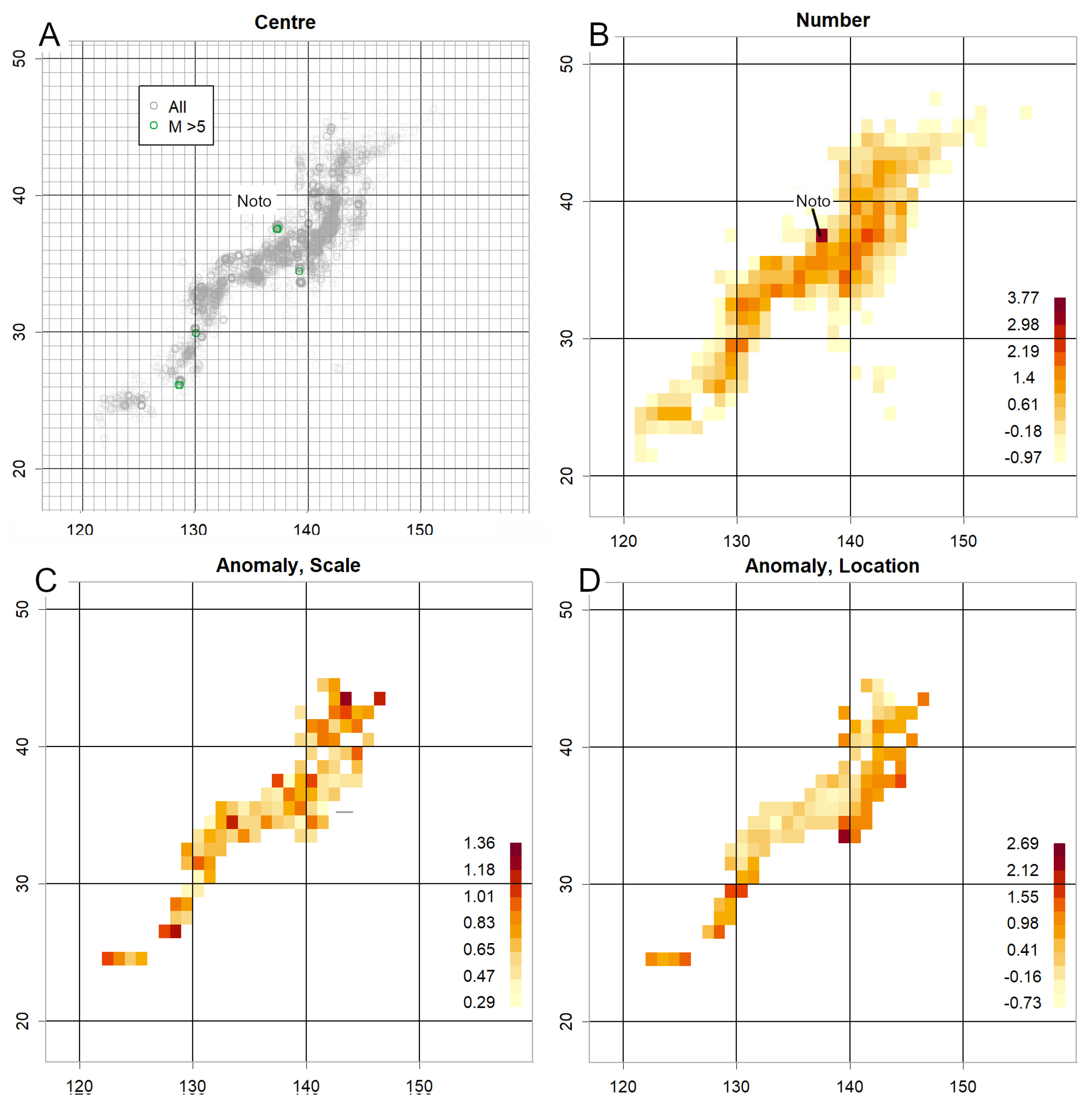

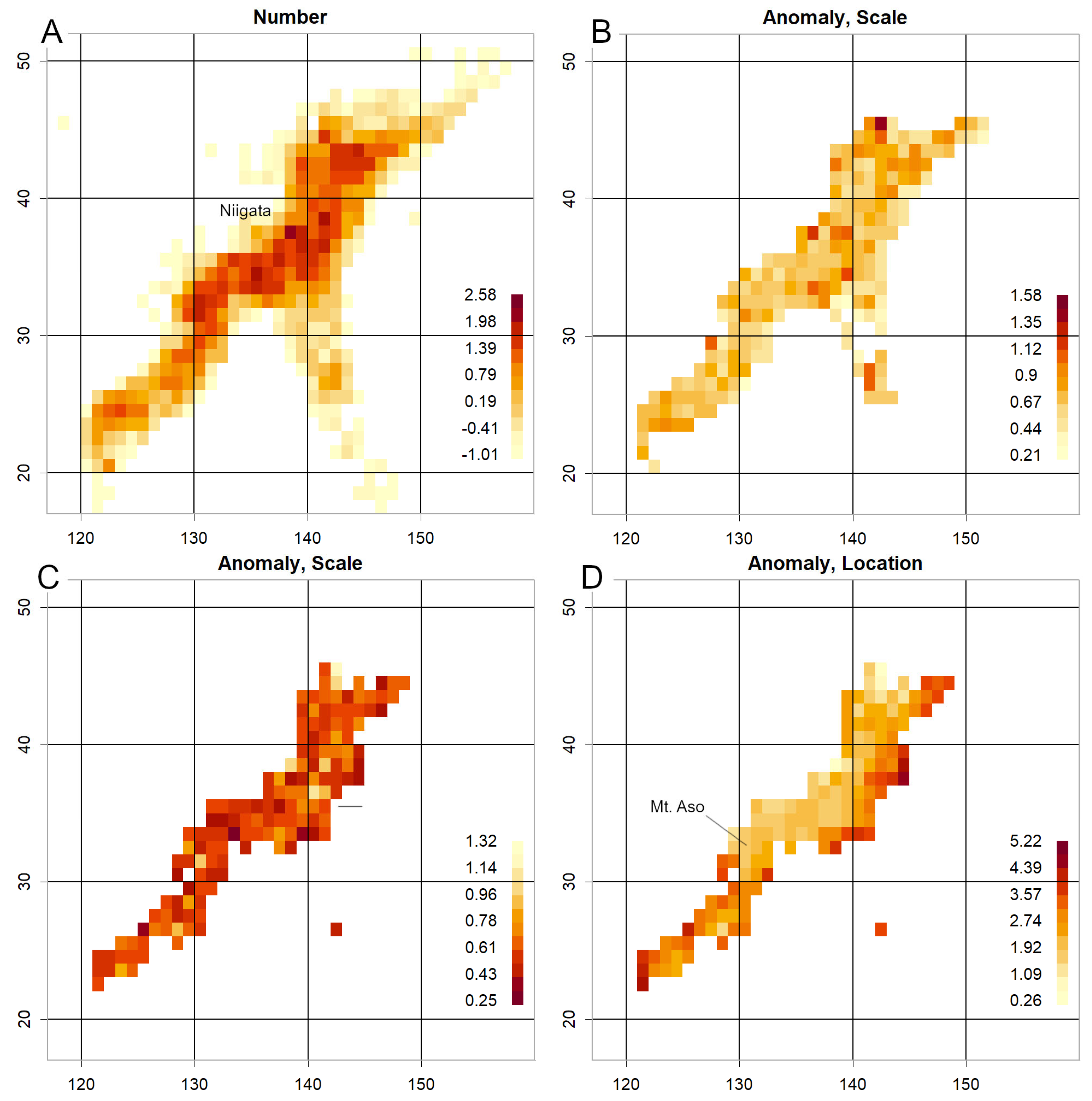

To evaluate whether the method could detect earthquakes in advance, anomalies in the investigated parameters were examined for the Mid Niigata Prefecture Earthquake (October 2004, M6.8) (JMA, 2024c), the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake (M9) (JMA, 2011), the Kumamoto Earthquake (April 2016, M7.3) (JMA, 2016), and the Noto Peninsula Earthquake (January 2024, M7.6) (JMA, 2024b).

Implementation

All calculations were performed using R (R Core Team, 2025). The code is provided in the Supplement. As two types of data with different formats were used, two versions of the code are supplied. Some figures utilise data provided by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) (JMA, 2025f), realised using the open-source technology Leaflet (Agafonkin, 2025).

Visualisation and Legend

Gri data are visualised by arranging square tiles corresponding to 1° latitude by 1° longitude segments. This was implemented using the image function in R, which maps numerical values to colours across a defined spatial grid. To aid interpretation, a legend is displayed to the right of each figure.

The legend represents an arithmetic sequence spanning the minimum and maximum values present in the figure. Each tile is assigned a single colour according to its corresponding value, using the same scale as the legend. The colour palette can be easily modified within the R code. For the present study, a palette optimised for colour-blind accessibility was selected to ensure broader readability.

Some Notes

In this study, verification frameworks such as ETAS (Zhang et al., 2024) and CSEP (Research Center for Earthquake Forecast 2025) were not employed. These models are grounded in assumptions and formulae that have recently been called into question (Konishi, 2025d, c). Accordingly, the present approach offers a more straightforward perspective on seismic phenomena, distinct from established paradigms.

To detect anomalies, comparisons were made using nationwide data from the same time period. This decision was not arbitrary. Initially, we considered constructing a control dataset by averaging data from several previous years. However, this approach proved ineffective due to a marked increase in the number of observed epicentres in recent years. This rise is likely attributable to the deployment of more sensitive seismic instrumentation following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake (JMA, 2011; Konishi, 2025a; The Headquarters for Earthquake Research Promotion, 2009). As a result, comparisons with historical data are fundamentally problematic. Should this trend of improved detection continue, the most appropriate baseline for comparison will ultimately be contemporary data from across Japan.

While excluding the target location from the national average might enhance anomaly sensitivity, implementing such a procedure would significantly complicate the programming. This, in turn, would hinder secondary use and increase both computational cost and processing time. For these reasons, this refinement was not pursued in the present analysis.

No uniform nationwide threshold has been defined in this study. Such an approach would likely be inappropriate, given that seismic risk varies considerably by region. This spatial heterogeneity becomes increasingly evident upon closer examination of the data. For instance, analysis of data from 1994 reveals that in the Hanshin region, only a single grid cell exhibited a notable anomaly, with a scale of approximately 1.5 (Konishi, 2025c). This cell was situated directly above the Seto Inland Sea interface, where the Philippine Sea Plate converges with the Eurasian Plate—a tectonically active zone known for its seismic potential. Notably, the Great Hanshin–Awaji Earthquake struck this very region the following year (JMA, 2025b). Had such an anomaly occurred in a less seismically sensitive area, a more cautious, observational approach might have been justified. However, determining the significance of such anomalies requires not only geological context but also several years of operational experience. As such, the establishment of region-specific thresholds remains a subject for future investigation.

Discussion

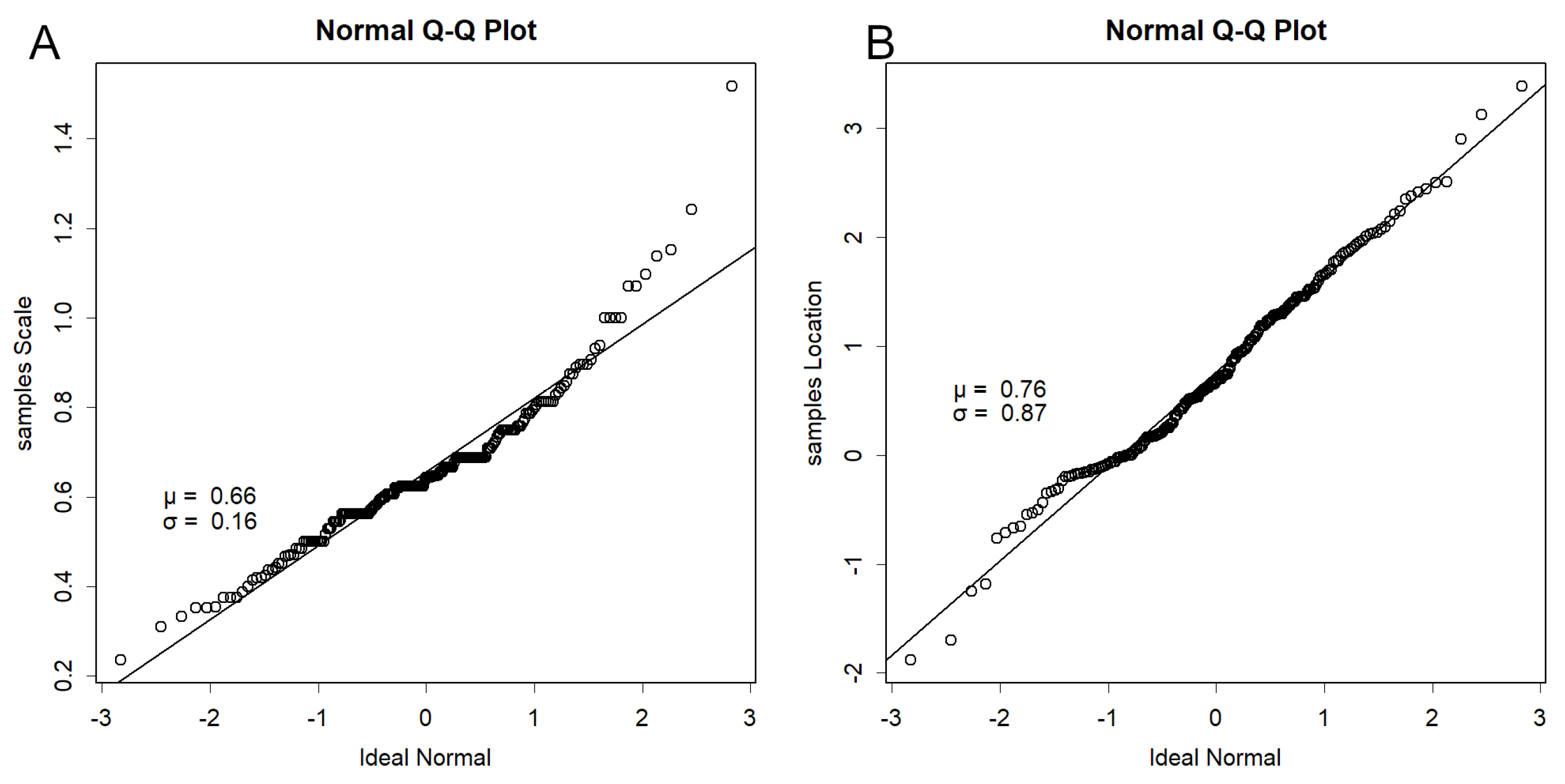

Regarding grid magnitudes exhibiting considerably low σ (

Figure 3A): theoretically, σ should equal 1 if selection were random (

Figure S2A), yet in practice it is approximately 0.6. This is unlikely to be an artefact of estimation. Although such results are common when estimating with very few data points (

Figure S2A), here at least 12 data points were available. Each grid can be considered as the interior of squares with sides of approximately 100 km, corresponding to a radius of 1°. The properties of nearby epicentres are likely similar, whether related to fault presence or plate slip. Most data are collected over a year and are not necessarily continuous, yet earthquakes occurring within a grid likely share similar mechanisms. Consequently, σ becomes smaller, indicating that significant differences in magnitude are unlikely.

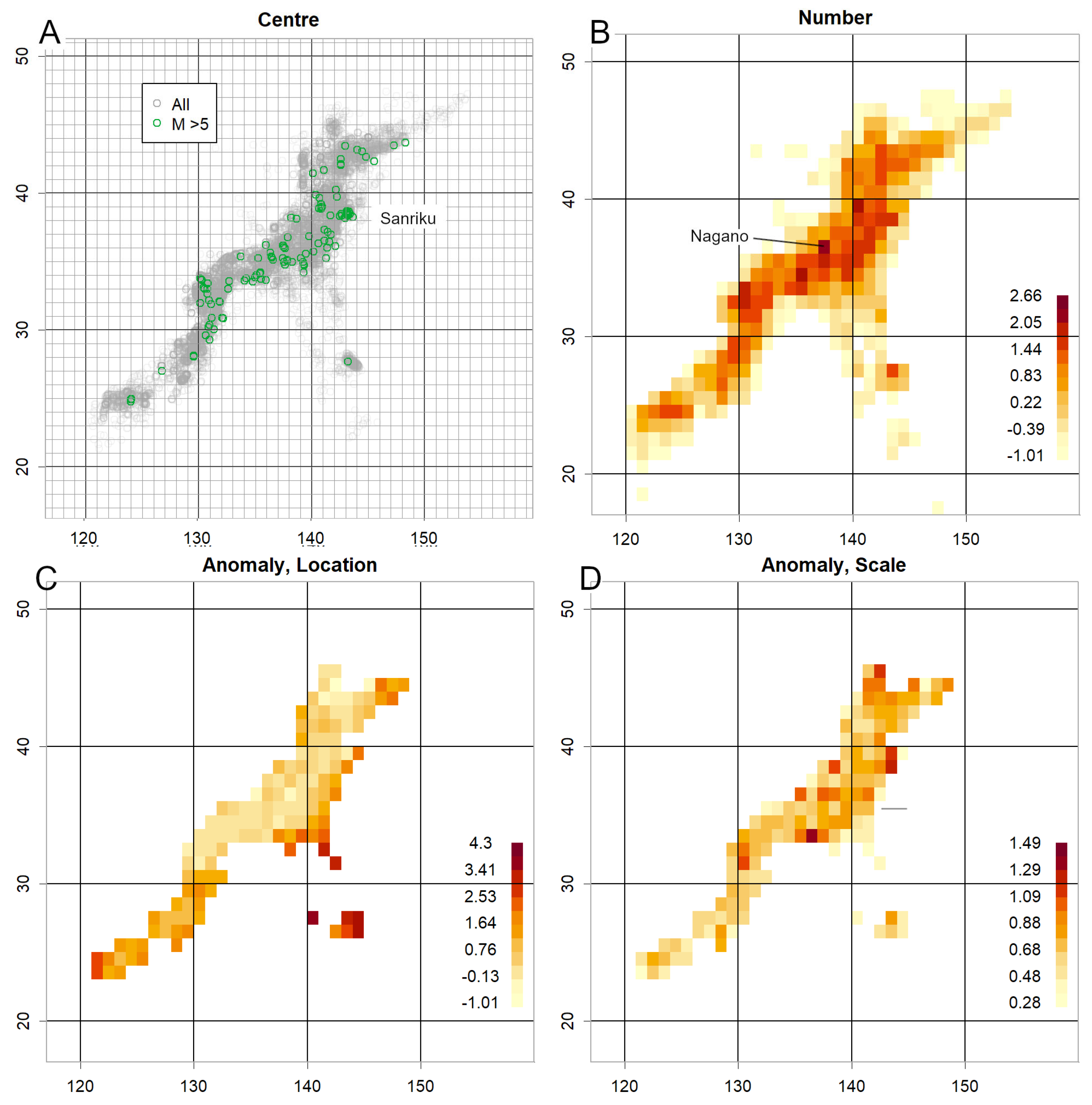

Underestimation of scale suggests clustering of magnitude values within a grid. This may occur if volcanic activity increases the number of earthquakes caused by magma movement (Konishi, 2025b). Such phenomena have been observed during several volcanic episodes (

Figure 6C, S3CD). Near the First Kashima Seamount, σ is low but consistently exceeds the measurement range (

Figure 4D,

Figure 5C,

Figure 6C,

Figures S3C, S4D), and has only been measured once (

Figure S3D). Volcanic activity may therefore be occurring in this vicinity, which is also a fault-rich area at the northern end of the Japan Trench (Nakajima, 2025). Intensified observation may be warranted. Similarly, the offshore area in the central Japan Sea, where location readings are consistently high (

Figure S3AB), also shows low σ values, suggesting possible volcanic activity (

Figure S3CD) (Japan Coast Guard, 2013).

Other explanations for low σ are also plausible. For example, Sanriku and Chiba Prefecture exhibited low σ values similar to those observed for Myojin Reef and Iwo Jima (

Figure S3D), despite lacking notable volcanoes. Low σ values therefore indicate potential hazards but require careful scrutiny. For volcanic activity estimation, this method should be combined with others, as eruptions can occur without accompanying low σ values, as observed at Sakurajima. Such eruptions likely involve minimal magma movement. Further investigation using independent geophysical datasets may help clarify the origin of low-σ anomalies, particularly in volcanic regions.tyot

Regarding grid magnitudes indicating significantly high locations (

Figure 3B): most grids contain limited data, with locations having fewer than 12 data points constituting approximately 80% of the total—a characteristic of the log-normal distribution (

Figure 1C). These locations are predominantly marine (

Figure 1B,

Figure 6A), where measurement is difficult. Observations in such areas are feasible only for events exceeding a certain magnitude threshold. Consequently, the overall mean value tends to be elevated, even after categorisation.

To normalise, QQ plots were presented by category. Alternatively, one could average the data and apply a correction, such as a spline function aligning the M4 position with that in

Figure 2B. This would avoid biased estimation errors arising from low counts (

Figure 2AB). However, such an approach was not employed, as it would inevitably yield the desired data shape, undermining analytical falsifiability (Thornton, 2023). Rigorous methodology entails certain inconveniences, and exclusion of low-count data is likely more appropriate, as such data are probably unnecessary.

Regarding the cause of count numbers following a log-normal distribution (

Figure 1C): earthquake intervals fundamentally follow an exponential distribution (Konishi, 2025d), and it was initially considered whether the inverse of count numbers might correspond to this. In practice, however, this was not the case (Konishi, 2025a), likely because each grid possesses a different λ. Log-normal distributions typically emerge from the synergy of multiple random factors (Stuart and Ord, 1994). Magnitude represents the energy released by an earthquake in logarithmic terms, so its normal distribution (

Figure 3B) indicates that energy itself follows a log-normal distribution (Konishi, 2025d). Similarly, earthquake frequency may be determined by the synergistic effect of such factors. The recent high frequency and elevated location of earthquakes off the Sanriku coast suggest that several of these factors have been consistently active. The addition of new factors would likely increase both event frequency and magnitude synergistically. This is probably what triggered the most recent earthquake (M6.7) and caused their rapid increase within a short period.

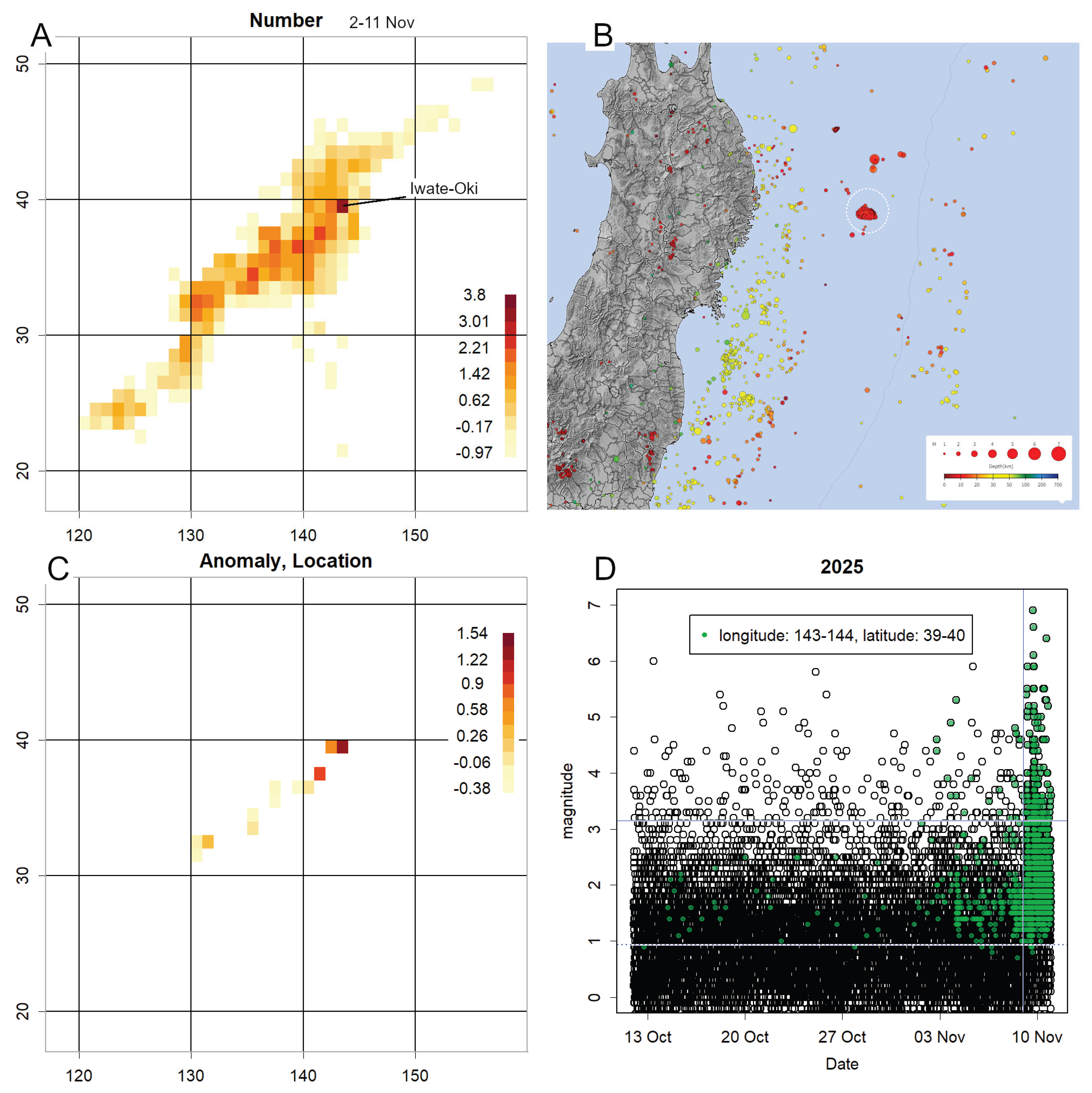

Whilst a consolidated earthquake catalogue simplifies calculations, even the most recent data are available only on a daily basis (JMA, 2025f). Calculations are feasible with two weeks’ (

Figure 5) or three weeks’ worth of data (

Figure S4). However, the requirement for at least 12 counts narrows the observation range, leaving marine areas underrepresented (

Figure 5B,

Figures S4A, S5). Nevertheless, meaningful insights can still be obtained, warranting continued investigation. Particular caution is required when anomalies appear in locations with high counts, as location and scale values typically converge with those of other grids (

Figure 2B) (Konishi, 2025a). Significant deviations in such cases likely indicate meaningful phenomena.

Elevated location and scale values at high-count sites are particularly hazardous, as they increase the expected probability of a large earthquake (Konishi, 2025d). This phenomenon was observed prior to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake (

Figure 4) and the 2024 Noto earthquake (

Figure 5). When anomalies are detected, verification using the classification system employed by the Japan Meteorological Agency is advisable. The simplest method is to compare magnitude data from these locations with others using QQ plots ) (Konishi, 2025a) (

Figure 2C,

Figure S1AB,

7C). Such verification is crucial, as anomalies may provide the basis for earthquake prediction. Many JMA classifications cover smaller areas than the grid used here, so anomalies are expected to appear more sharply defined; surrounding areas should also be examined, as responsibility for issuing instructions to residents lies with local authorities.

Immediately prior to the M9 Tohoku earthquake, a precursor swarm with an extremely high location was observed (JMA, 2011; Konishi, 2025d). The recent earthquake off Iwate Prefecture may correspond to this (

Figure 7D). Between 1 and 8 November, counts in this grid increased sharply, with large magnitudes and extremely low P-values. Thus, when a sudden increase in counts is accompanied by elevated location or scale values, the situation should be judged hazardous. For example, the geometric mean of daily counts from 3–8 November was 35, with a z-score exceeding 3 (compared with ~0.5 prior to 1 November). The sudden emergence of such values in a grid of this size warrants vigilance.

At present, the Iwate earthquake appears to be decaying, accompanied by numerous aftershocks (

Figure 7D and

Figure S6B) (Utsu et al., 1995). Whether convergence will occur remains unclear until further data are available. Due to these aftershocks, both magnitude and counts remain high, and the anomaly persists. Should scale increase, the hazard would be considerable.

To date, only large earthquakes accompanied by swarm activity have been investigated, resulting in high counts (Konishi, 2025d). Focusing on such events may be advisable. The R code includes a presentation option limiting plots to grids with counts >100 (

Figures S5, 7C). Scale can pose problems both when high and when low, and different colour charts are used to enhance readability (

Figures S4CD).

This method can be implemented automatically. Provided conditions are set appropriately for the region, R performs calculations efficiently, requiring little computation time. For Japan, this approach is sufficient. However, results are not always conclusive. For example, the 2018 Eastern Iburi earthquake (M6.7) was not predicted. An anomaly (Konishi, 2025d) that might have been detected by combining several regions into a single QQ plot was obscured. Using a 4° interval instead of 1° revealed the anomaly, but the grid became too coarse, covering most of Hokkaido and hindering site identification. Similarly, the 2021 Fukushima earthquake could not have been predicted without monthly rather than annual data. Anomalies are likely easier to detect during swarm activity (Konishi, 2025d). Attempts to shorten the period in Iburi resulted in insufficient data, highlighting a trade-off between simplicity and sensitivity.

Apart from the recent Iwate event, no evidence has been found of the high-magnitude precursor swarms observed immediately before the Thoku mainshock (JMA, 2011; Konishi, 2025d). In most cases, the period preceding the mainshock was quiet (Konishi, 2025d). Consequently, even if anomalies are detected, the timing of the mainshock cannot generally be determined. Several methods have been proposed to predict the timing of major earthquakes (Nagao et al., 2014; Tanaka et al., 2004; Varotsos et al., 2024a; Varotsos et al., 2024b). However, given Japan’s high frequency of large earthquakes, it is difficult to distinguish whether such findings are coincidental or represent underlying phenomena. Their validity does not yet appear established (JMA, 2024a). Nevertheless, should reliable timing determination become possible, it would greatly enhance practical utility.