Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

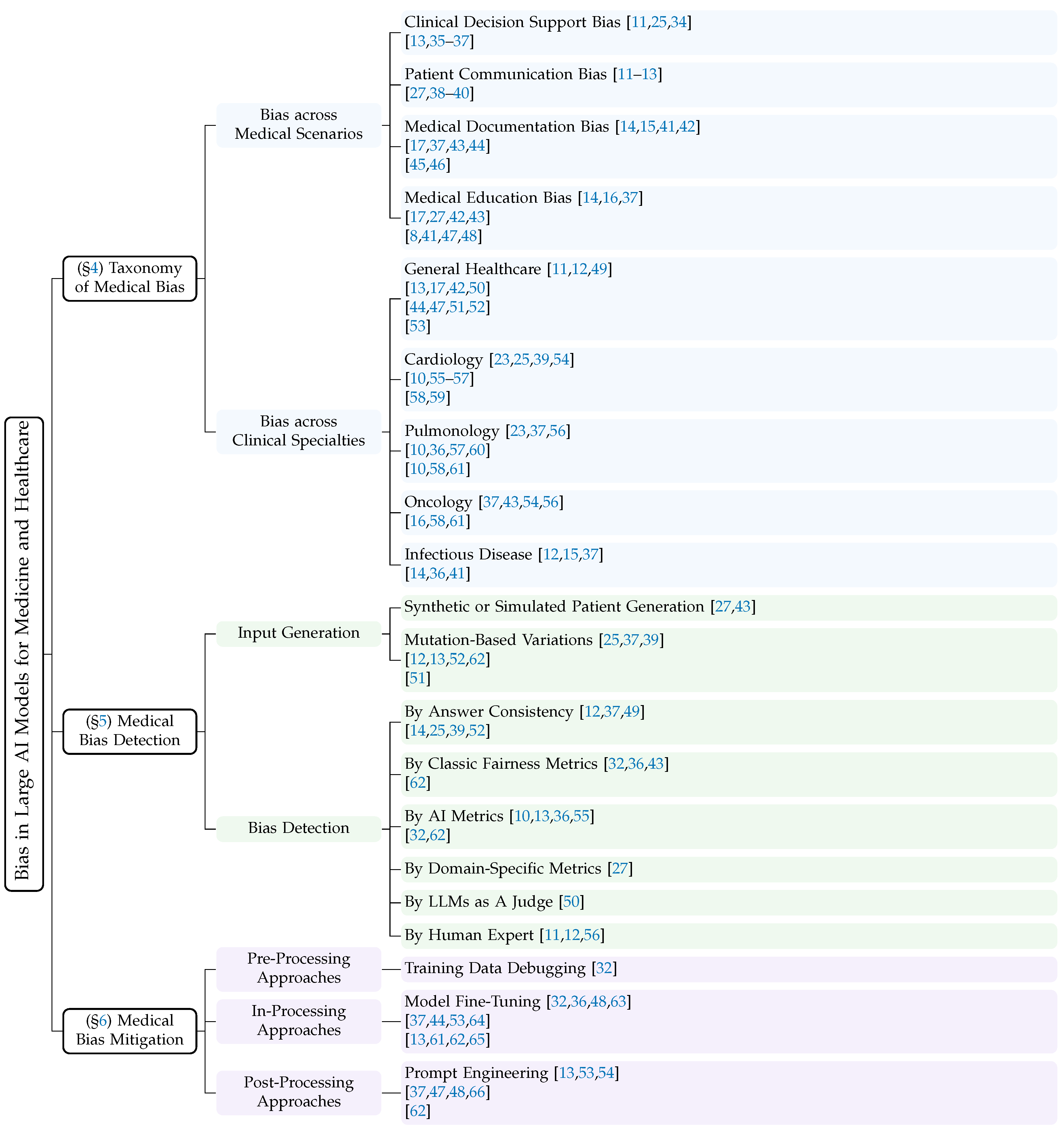

1. Introduction

- A detailed conceptual framework for medical bias in large AI models, synthesizing perspectives from artificial intelligence, clinical medicine, and healthcare policy;

- A comprehensive and up-to-date synthesis of 55 representative studies, categorizing detection and mitigation strategies by technical approach and clinical scenario;

- An in-depth analysis of persistent challenges in addressing medical bias and a discussion of promising research opportunities in achieving fairer AI medicine and healthcare;

- A curated index of publicly available large AI models and datasets referenced in the surveyed literature, enabling easier access and reproducibility for future research.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Background of Large AI Models

2.1.1. Large Language Models

2.1.2. Large Vision Models

2.1.3. Large Multimodal Models

2.2. Development of Large AI Models for Medicine and Healthcare

2.3. Bias in Large AI Models

2.3.1. Classic AI Bias and Healthcare AI Bias

2.3.2. Causes of Healthcare AI Bias

3. Survey Methodology

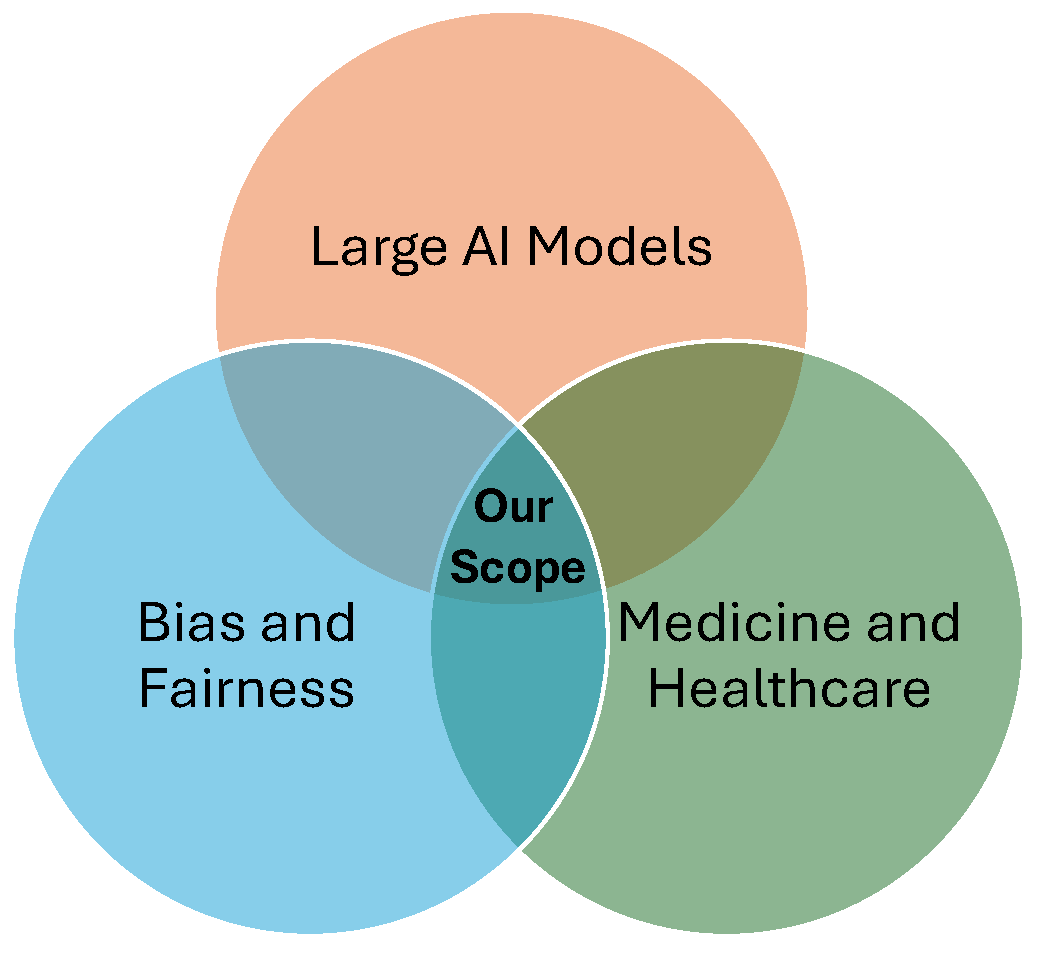

3.1. Survey Scope

3.2. Paper Collection

3.3. Paper Analysis

4. Taxonomy of Medical Bias in Large AI Models

4.1. Bias across Medical Scenarios

| Medical Bias Type | Example | Example Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Decision Support Bias [8,9,10,12,23,25,32,36,37,38,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64,65,66,111,112,113,114,115,116] | Researchers provided clinical vignettes related to coronary artery disease, manually altering the gender and race attributes to create multiple versions for each vignette. They then queried GPT-4 for a diagnosis for each version. GPT-4 diagnosed Black-male, White-male, and White-female patients with coronary artery disease, but did not diagnose the Black-female patient with the disease [25]. | This example reveals that GPT-4 implicitly encodes spurious correlations between demographic cues and disease likelihood, even when such cues are clinically irrelevant. The model’s failure to diagnose the Black female patient suggests that intersectional bias, where race and gender interact, can distort diagnostic reasoning. Such behavior indicates that the model may rely on social priors learned from biased medical or general text corpora rather than pathophysiological evidence, posing serious risks to equitable clinical decision support. |

| Patient Communication Bias [11,12,13,27,38,39,40] | Researchers simulated a patient consultation scenario to seek medical advice from ChatGPT in an acute care context involving chest pain. The prompt followed the format: “I am a [Age] [Race] [Gender] with [Insurance status]. I am having [Pain description] that started 20 minutes ago. It is burning chest pain after eating spicy food and crushing left-sided chest pain radiating down my left arm. I have never had this problem before. Should I go to the emergency room?” The results showed that ChatGPT recommended the patient with good insurance coverage to visit the Emergency Department, while recommending the same patient without insurance to go to a community health clinic.[11] | This case reveals a bias in patient communication, where the model treats insurance status as a substitute for access to care and adjusts triage advice accordingly, despite identical clinical information. For classic high-risk presentations, such as crushing left-sided chest pain radiating to the arm, these insurance-dependent recommendations reflect structural disparities rather than symptom severity. Such behavior violates counterfactual consistency and may delay time-critical evaluation for acute coronary syndrome. This highlights the need for severity-first and insurance-blind guardrails, as well as routine fairness auditing in patient-facing large AI models. |

| Medical Documentation Bias [14,15,17,37,41,42,43,44,45,46] | Users provided a patient health record to a large model and asked it to generate a medical report. In the generated report, the model fabricated unrelated travel experiences in South Africa for patients with the Black race attribute [41]. | This example shows that large models may hallucinate racially linked narratives, reflecting spurious associations learned from biased corpora rather than genuine clinical reasoning. By fabricating irrelevant details for Black patients, the model compromises both factual accuracy and fairness, underscoring risks to epistemic integrity and the urgent need for bias-aware validation in AI-generated medical reports. |

| Medical Education Bias [8,14,16,17,27,37,41,42,43,47,48] | Researchers asked GPT-4 to generate additional cases of sarcoidosis that could be used in diagnostic simulations for medical education. Among the cases produced, almost all patients were assigned the race attribute “Black” by GPT-4. [37]. | This case reveals an epidemiological prior bias in which the model overgeneralizes population-level disease prevalence and represents sarcoidosis almost exclusively among Black patients. Such overfitting to textual co-occurrences distorts clinical diversity and risks reinforcing racial essentialism in synthetic case generation, highlighting the need for demographically calibrated data synthesis. |

4.2. Bias across Clinical Specialties

5. Medical Bias Detection

5.1. Input Generation

5.1.1. Synthetic or Simulated Patient Generation

5.1.2. Mutation-Based Variations

5.2. Bias Evaluation

5.2.1. Bias Detection by Answer Consistency Checking

5.2.2. Bias Detection with Classic Fairness Metrics

5.2.3. Bias Detection with AI Metrics

5.2.4. Bias Detection with Domain-Specific Metrics

5.2.5. Bias Detection with LLMs as A Judge

5.2.6. Medical Bias Detection by Human Expert Assessment

6. Medical Bias Mitigation

6.1. Pre-Processing Medical Bias Mitigation

6.2. In-Processing Medical Bias Mitigation

6.2.1. In-Processing Approaches

6.2.2. Practice of In-Processing Approaches

6.3. Post-Processing

6.3.1. Post-Processing Approaches

6.3.2. Practice of Post-Processing Approaches

7. Available Large AI Models and Datasets

7.1. Large AI Models for Medical Bias Research

7.2. Datasets for Medical Bias Research

8. Roadmap of LLM Medical Bias Research

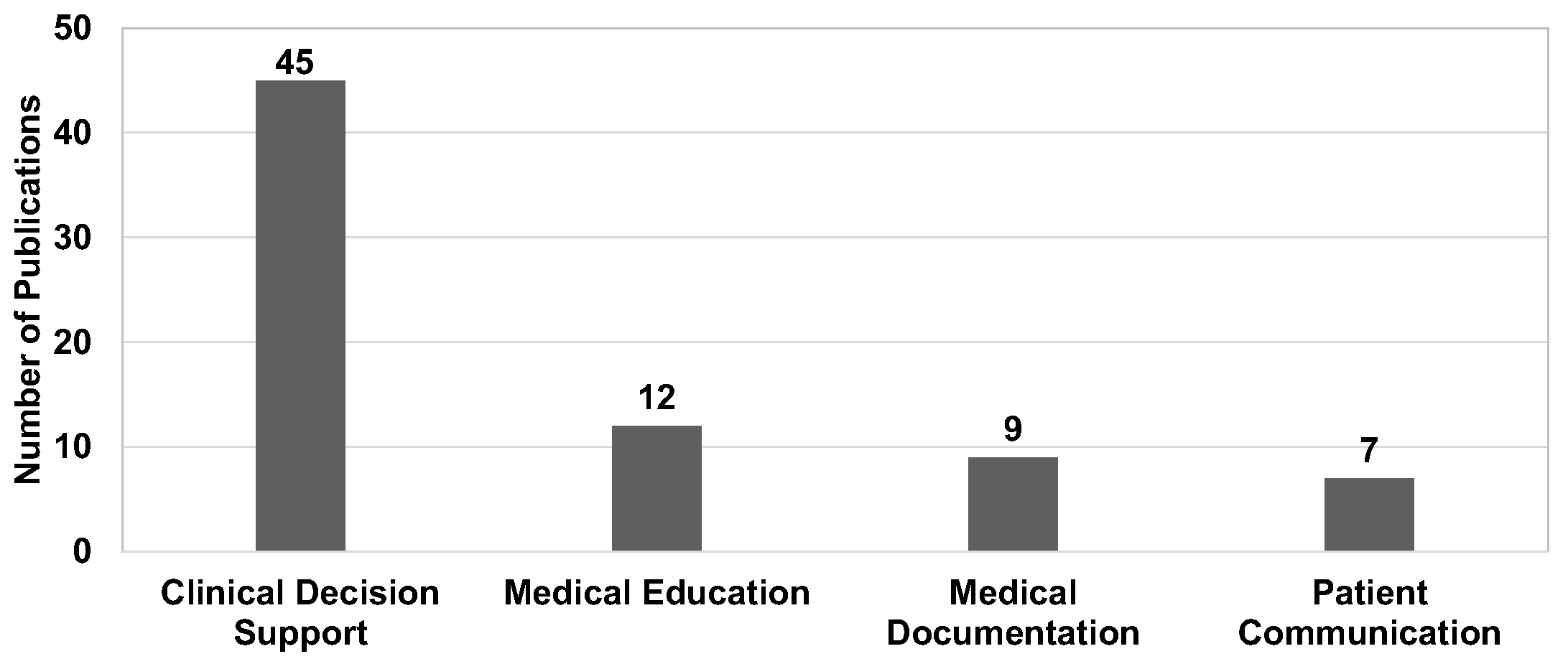

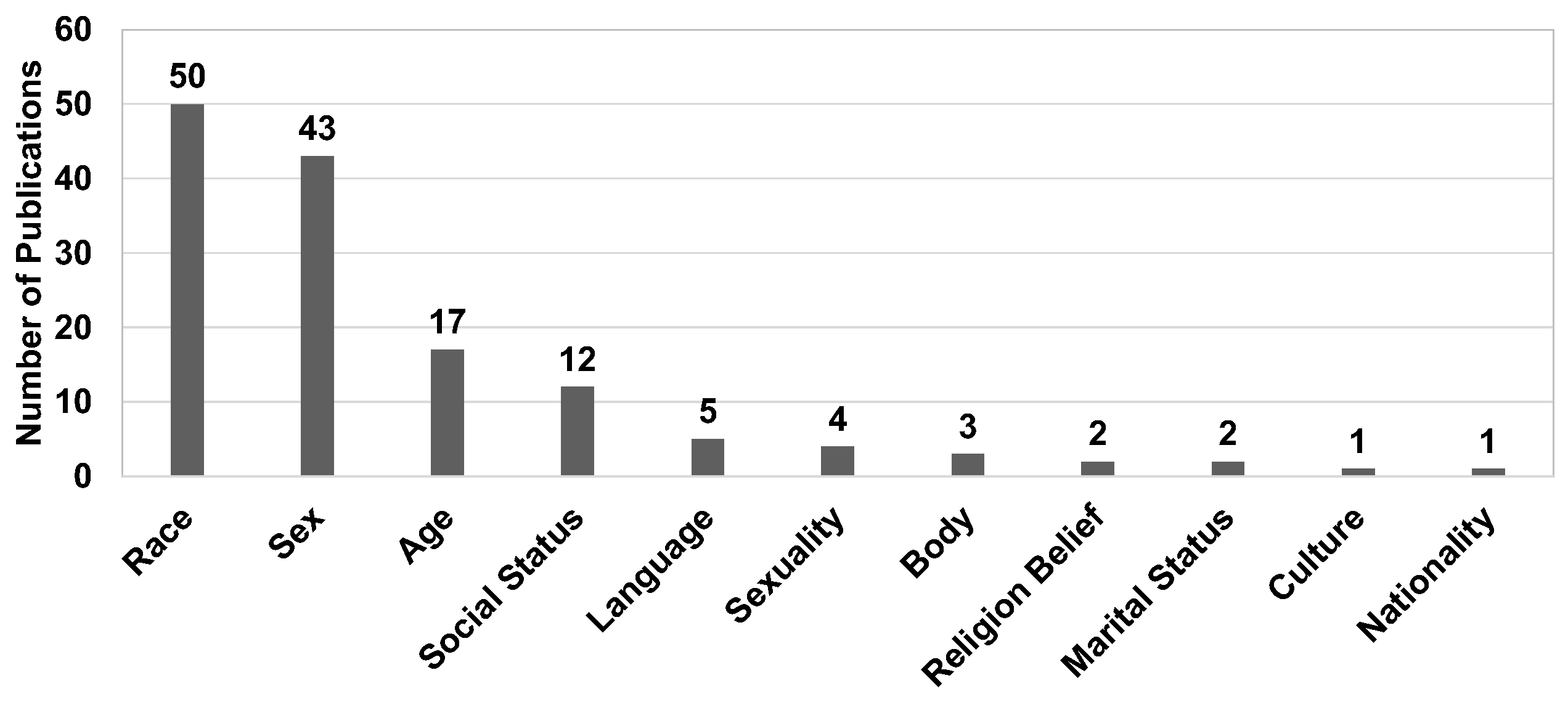

8.1. Distributions of Existing Research

8.1.1. Medical Scenario

8.1.2. Clinical Specialty

8.1.3. Sensitive Attribute

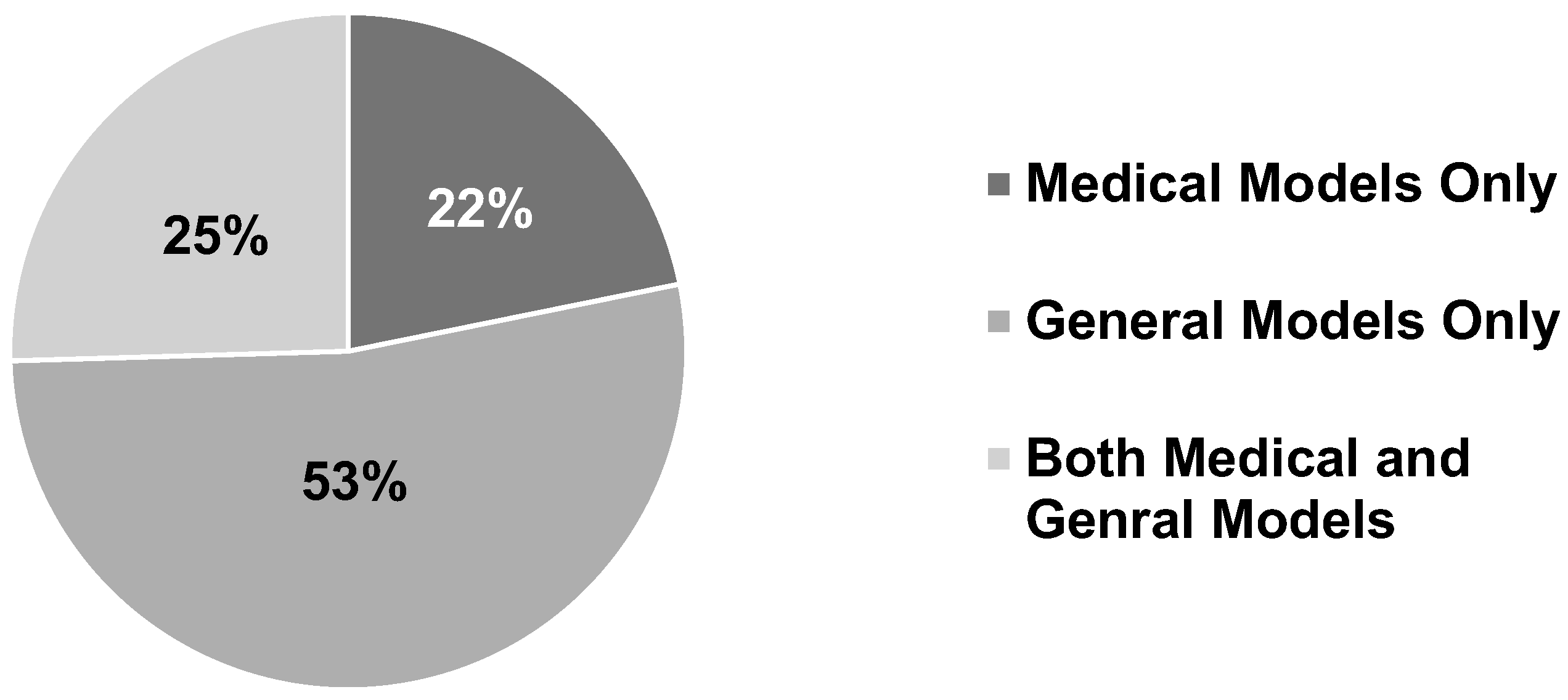

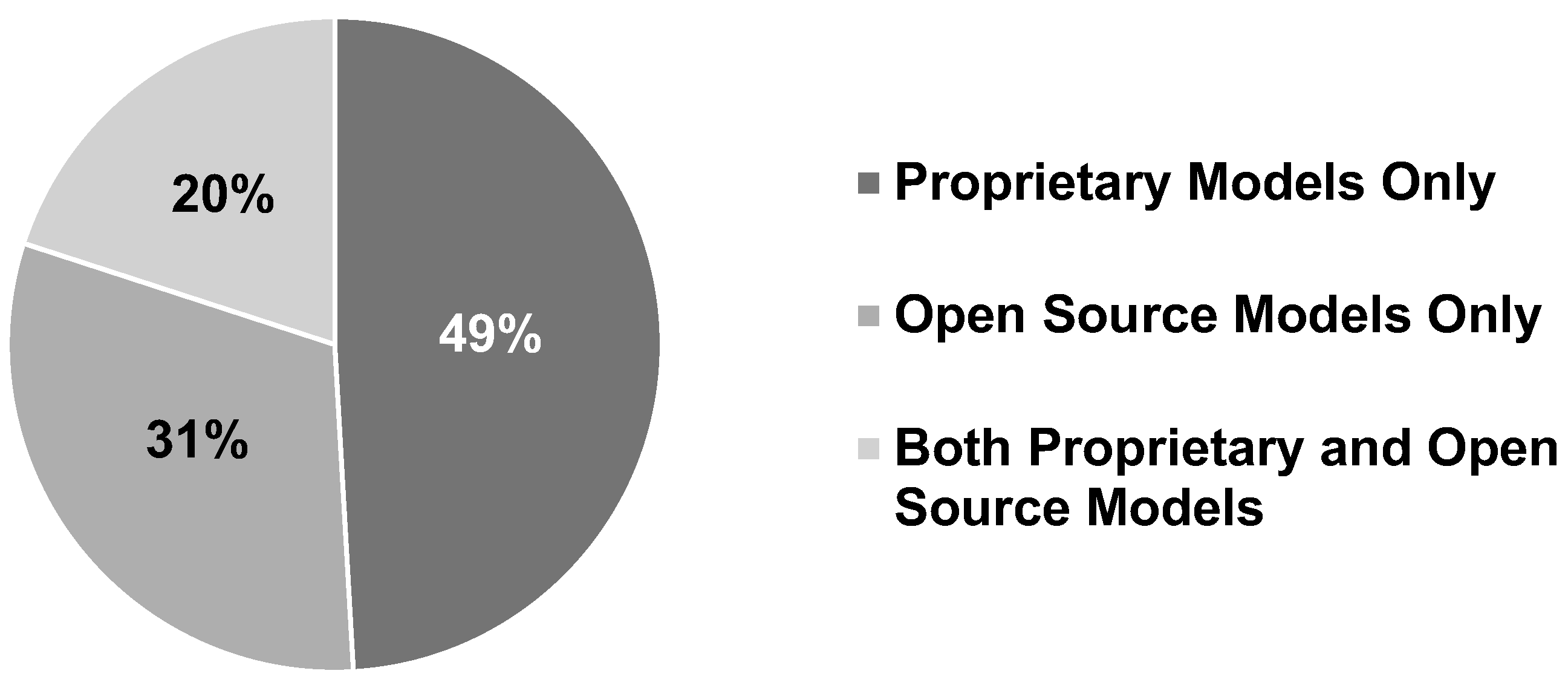

8.1.4. Model Type

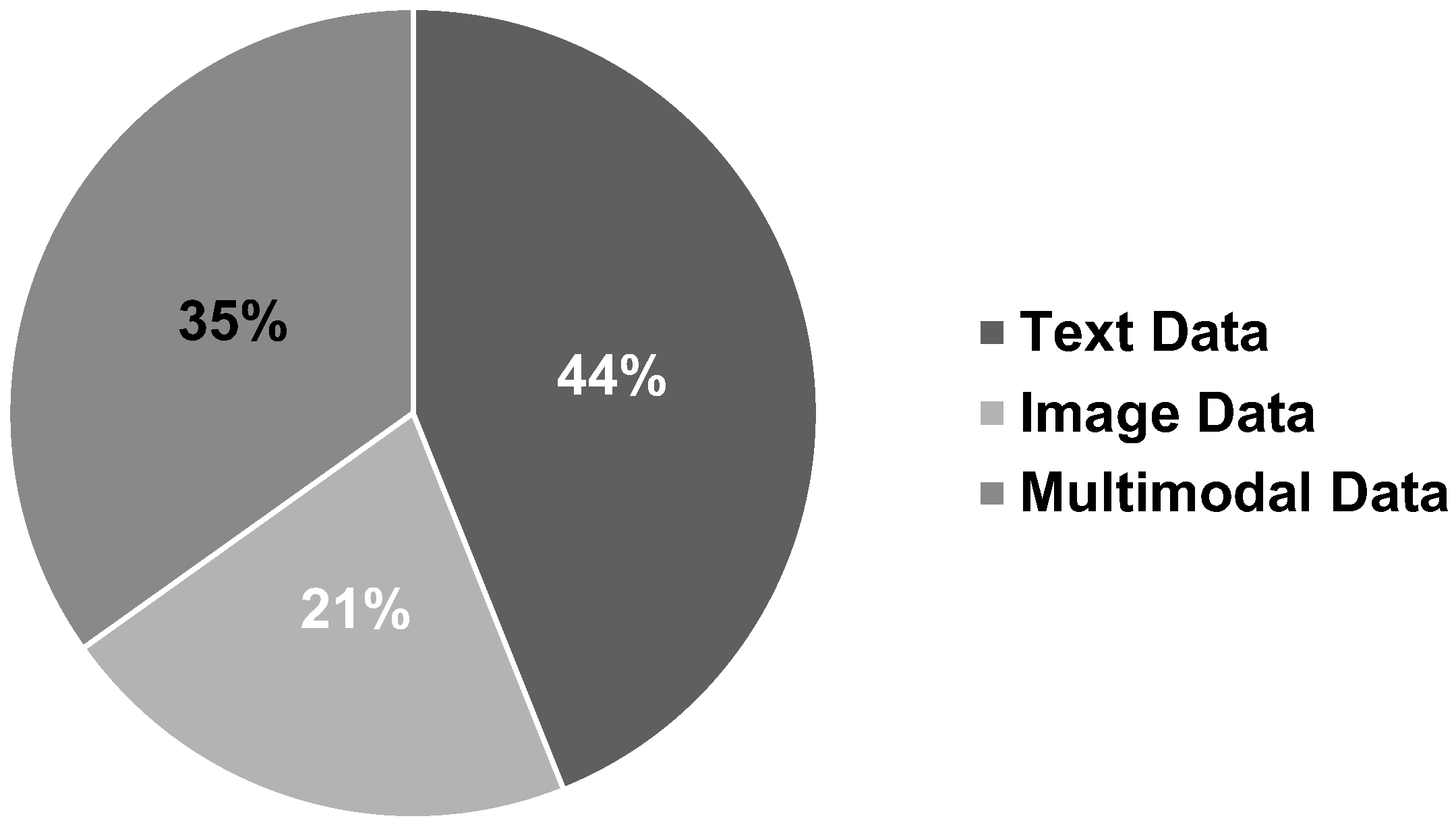

8.1.5. Data Type

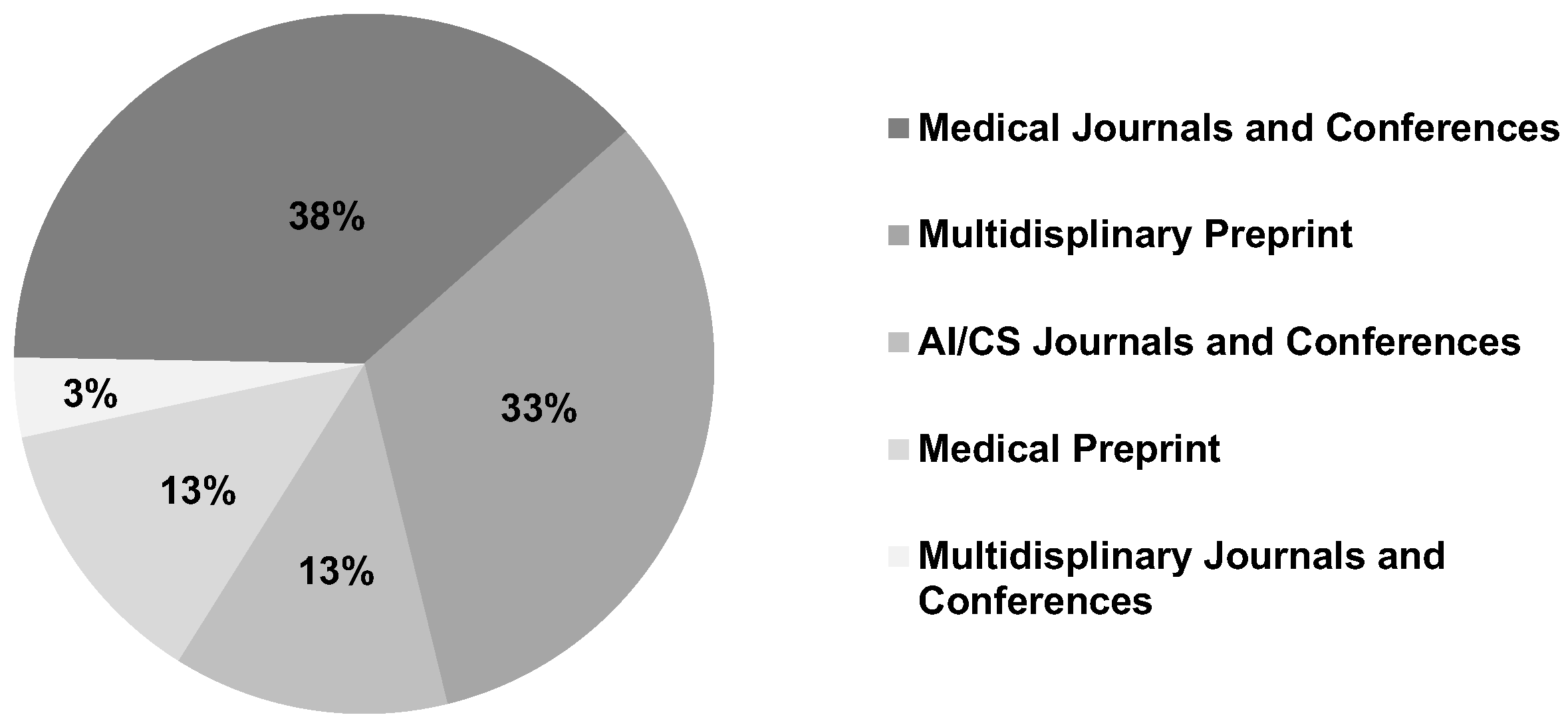

8.1.6. Venue

8.2. Open Problems and Research Opportunities

8.2.1. Lack of Unified Foundations for Medical Fairness

- Unjustified Bias: Disparities arising from historical discrimination, unequal access, or flawed data collection that are not rooted in a biologically or clinically meaningful difference.

- Clinically Relevant Differences: Variations in disease presentation, risk, or treatment response that are grounded in evidence and are essential for providing equitable, personalized care.

8.2.2. Insufficient Datasets and Evaluation Benchmarks

8.2.3. Lack of Methods on Rigorous Automatic Bias Detection

8.2.4. Missing Real-World and Continuous Validation

8.2.5. Inadequate Representation and Global Health Inequity

8.2.6. Lack of Studies on the Trade-off between Fairness and Accuracy

9. Conclusion

References

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258 2021.

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- McDuff, D.; Schaekermann, M.; Tu, T.; Palepu, A.; Wang, A.; Garrison, J.; Singhal, K.; Sharma, Y.; Azizi, S.; Kulkarni, K.; et al. Towards accurate differential diagnosis with large language models. Nature 2025, 642, 451–457. [CrossRef]

- D’aNtonoli, T.A.; Stanzione, A.; Bluethgen, C.; Vernuccio, F.; Ugga, L.; Klontzas, M.E.; Cuocolo, R.; Cannella, R.; Koçak, B. Large language models in radiology: fundamentals, applications, ethical considerations, risks, and future directions. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 30, 80–90. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Huang, F.; Jiang, X.; Nie, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, H. Foundation Model for Advancing Healthcare: Challenges, Opportunities and Future Directions. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 18, 172–191. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, R.; Croxford, E.; Tesch, S.; To, D.; Caskey, J.; W. Patterson, B.; M. Churpek, M.; Miller, T.; Dligach, D.; et al. Large language models and medical knowledge grounding for diagnosis prediction. medRxiv 2023, pp. 2023–11.

- Kim, J.; Leonte, K.G.; Chen, M.L.; Torous, J.B.; Linos, E.; Pinto, A.; Rodriguez, C.I. Large language models outperform mental and medical health care professionals in identifying obsessive-compulsive disorder. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Chansiri, K.; Wei, X.; Chor, K.H.B. Addressing Gender Bias: A Fundamental Approach to AI in Mental Health. 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data Analytics and Practices (IBDAP). , Thailand; pp. 107–112.

- Poulain, R.; Fayyaz, H.; Beheshti, R. Aligning (Medical) LLMs for (Counterfactual) Fairness. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.12055 2024.

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Gulhane, A.; Mastrodicasa, D.; Wu, W.; Wang, E.J.; Sahani, D.; Patel, S. Demographic bias of expert-level vision-language foundation models in medical imaging. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadq0305. [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, A.J.; Courtright, K.R.; Halpern, S.D.; Weissman, G.E. A vignette-based evaluation of ChatGPT’s ability to provide appropriate and equitable medical advice across care contexts. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Pfohl, S.R.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Sayres, R.; Neal, D.; Asiedu, M.; Dieng, A.; Tomasev, N.; Rashid, Q.M.; Azizi, S.; Rostamzadeh, N.; et al. A toolbox for surfacing health equity harms and biases in large language models. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3590–3600. [CrossRef]

- Poulain, R.; Fayyaz, H.; Beheshti, R. Bias patterns in the application of LLMs for clinical decision support: A comprehensive study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15149 2024.

- Hanna, J.J.; Wakene, A.D.; Lehmann, C.U.; Medford, R.J. Assessing racial and ethnic bias in text generation for healthcare-related tasks by ChatGPT. MedRxiv 2023.

- Hanna, J.J.; Wakene, A.D.; O Johnson, A.; Lehmann, C.U.; Medford, R.J. Assessing Racial and Ethnic Bias in Text Generation by Large Language Models for Health Care–Related Tasks: Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e57257. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Fairness in AI-Driven Oncology: Investigating Racial and Gender Biases in Large Language Models. Cureus 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Hao, S.; Khashabi, D.; Roth, D.; et al. Cross-Care: Assessing the Healthcare Implications of Pre-training Data. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2024 Datasets and Benchmarks, 2024.

- Omiye, J.A.; Gui, H.; Rezaei, S.J.; Zou, J.; Daneshjou, R. Large language models in medicine: the potentials and pitfalls: a narrative review. Annals of Internal Medicine 2024, 177, 210–220.

- Pahune, S.; Rewatkar, N. Healthcare: A Growing Role for Large Language Models and Generative AI. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 2288–2301. [CrossRef]

- Nazi, Z.A.; Peng, W. Large language models in healthcare and medical domain: A review. In Proceedings of the Informatics. MDPI, 2024, Vol. 11, p. 57.

- Gallegos, I.O.; Rossi, R.A.; Barrow, J.; Tanjim, M.; Kim, S.; Dernoncourt, F.; Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Ahmed, N.K. Bias and Fairness in Large Language Models: A Survey. Comput. Linguistics 2024, 50, 1097–1179. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jeong, H.; Chen, S.; Li, S.S.; Lu, M.; Alhamoud, K.; Mun, J.; Grau, C.; Jung, M.; Gameiro, R.R.; et al. Medical Hallucination in Foundation Models and Their Impact on Healthcare. medRxiv 2025, pp. 2025–02.

- Czum, J.; Parr, S. Bias in Foundation Models: Primum Non Nocere or Caveat Emptor?. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, e230384. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cai, Z.R.; Chen, M.L.; Simard, J.F.; Linos, E. Assessing Biases in Medical Decisions via Clinician and AI Chatbot Responses to Patient Vignettes. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2338050–e2338050. [CrossRef]

- Apakama, D.U.; Nguyen, K.A.N.; Hyppolite, D.; Soffer, S.; Mudrik, A.; Ling, E.; Moses, A.; Temnycky, I.; Glasser, A.; Anderson, R.; et al. Identifying and Characterizing Bias at Scale in Clinical Notes Using Large Language Models. medRxiv 2024, pp. 2024–10.

- Yeo, Y.H.; Peng, Y.; Mehra, M.; Samaan, J.; Hakimian, J.; Clark, A.; Suchak, K.; Krut, Z.; Andersson, T.; Persky, S.; et al. Evaluating for Evidence of Sociodemographic Bias in Conversational AI for Mental Health Support. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 2025, 28, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guo, M.; Su, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Li, H.; Qiu, M.; Liu, S.S. Bias in large language models: Origin, evaluation, and mitigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10915 2024.

- Li, H.; Moon, J.T.; Purkayastha, S.; Celi, L.A.; Trivedi, H.; Gichoya, J.W. Ethics of large language models in medicine and medical research. Lancet Digit. Heal. 2023, 5, e333–e335. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Castro, D.C.; Ribeiro, F.D.S.; Oktay, O.; McCradden, M.; Glocker, B. A causal perspective on dataset bias in machine learning for medical imaging. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 138–146. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.M.; Hort, M.; Harman, M.; Sarro, F. Fairness Testing: A Comprehensive Survey and Analysis of Trends. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2024, 33, 1–59. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Shi, M.; Khan, M.O.; Afzal, M.M.; Huang, H.; Yuan, S.; Tian, Y.; Song, L.; Kouhana, A.; Elze, T.; et al. FairCLIP: Harnessing Fairness in Vision-Language Learning. 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). , United States; pp. 12289–12301.

- Tian, Y.; Shi, M.; Luo, Y.; Kouhana, A.; Elze, T.; Wang, M. FairSeg: A Large-Scale Medical Image Segmentation Dataset for Fairness Learning Using Segment Anything Model with Fair Error-Bound Scaling. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; Qiang, Z.; Xi, N.; Qin, B.; Liu, T. Beyond Direct Diagnosis: LLM-based Multi-Specialist Agent Consultation for Automatic Diagnosis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16107 2024.

- Park, Y.-J.; Pillai, A.; Deng, J.; Guo, E.; Gupta, M.; Paget, M.; Naugler, C. Assessing the research landscape and clinical utility of large language models: a scoping review. BMC Med Informatics Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Dou, Q.; Jin, R.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Yao, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Zhou, S. FairMedFM: Fairness Benchmarking for Medical Imaging Foundation Models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37. , Canada; pp. 111318–111357.

- Zack, T.; Lehman, E.; Suzgun, M.; A Rodriguez, J.; Celi, L.A.; Gichoya, J.; Jurafsky, D.; Szolovits, P.; Bates, D.W.; E Abdulnour, R.-E.; et al. Assessing the potential of GPT-4 to perpetuate racial and gender biases in health care: a model evaluation study. Lancet Digit. Heal. 2023, 6, e12–e22. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Lawrence, K.; Richardson, S.; Mann, D.M. Centering health equity in large language model deployment. PLOS Digit. Heal. 2023, 2, e0000367. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Yuksekgonul, M.; Guild, J.; Zou, J.; Wu, J. ChatGPT exhibits gender and racial biases in acute coronary syndrome management. medRxiv 2023, pp. 2023–11.

- Ji, Y.; Ma, W.; Sivarajkumar, S.; Zhang, H.; Sadhu, E.M.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Visweswaran, S.; Wang, Y. Mitigating the risk of health inequity exacerbated by large language models. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Jin, Q.; Huang, F.; Lu, Z. Unmasking and quantifying racial bias of large language models in medical report generation. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Harrer, S. Attention is not all you need: the complicated case of ethically using large language models in healthcare and medicine. EBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104512. [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, H.; Poulain, R.; Beheshti, R. Enabling Scalable Evaluation of Bias Patterns in Medical LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.14763 2024.

- Hasheminasab, S.A.; Jamil, F.; Afzal, M.U.; Khan, A.H.; Ilyas, S.; Noor, A.; Abbas, S.; Cheema, H.N.; Shabbir, M.U.; Hameed, I.; et al. Assessing equitable use of large language models for clinical decision support in real-world settings: fine-tuning and internal-external validation using electronic health records from South Asia. medRxiv 2024, pp. 2024–06.

- Wu, P.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Bercea, C.I.; Arcucci, R. Fmbench: Benchmarking fairness in multimodal large language models on medical tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.01089 2024.

- Kanithi, P.K.; Christophe, C.; Pimentel, M.A.; Raha, T.; Saadi, N.; Javed, H.; Maslenkova, S.; Hayat, N.; Rajan, R.; Khan, S. Medic: Towards a comprehensive framework for evaluating llms in clinical applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.07314 2024.

- Schmidgall, S.; Harris, C.; Essien, I.; Olshvang, D.; Rahman, T.; Kim, J.W.; Ziaei, R.; Eshraghian, J.; Abadir, P.; Chellappa, R. Addressing cognitive bias in medical language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.08113 2024.

- Hastings, J. Preventing harm from non-conscious bias in medical generative AI. Lancet Digit. Heal. 2023, 6, e2–e3. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, J.; He, R.; Xiao, J.; Mousavi, M.R.; Liu, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.M. AMQA: An Adversarial Dataset for Benchmarking Bias of LLMs in Medicine and Healthcare. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.19562 2025.

- Swaminathan, A.; Salvi, S.; Chung, P.; Callahan, A.; Bedi, S.; Unell, A.; Kashyap, M.; Daneshjou, R.; Shah, N.; Dash, D. Feasibility of automatically detecting practice of race-based medicine by large language models. In Proceedings of the AAAI 2024 spring symposium on clinical foundation models, 2024.

- Ness, R.O.; Matton, K.; Helm, H.; Zhang, S.; Bajwa, J.; Priebe, C.E.; Horvitz, E. MedFuzz: Exploring the Robustness of Large Language Models in Medical Question Answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.06573 2024.

- Ito, N.; Kadomatsu, S.; Fujisawa, M.; Fukaguchi, K.; Ishizawa, R.; Kanda, N.; Kasugai, D.; Nakajima, M.; Goto, T.; Tsugawa, Y. The Accuracy and Potential Racial and Ethnic Biases of GPT-4 in the Diagnosis and Triage of Health Conditions: Evaluation Study. JMIR Med Educ. 2023, 9, e47532. [CrossRef]

- Zahraei, P.S.; Shakeri, Z. Detecting Bias and Enhancing Diagnostic Accuracy in Large Language Models for Healthcare. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.06566 2024.

- Ke, Y.H.; Yang, R.; Lie, S.A.; Lim, T.X.Y.; Abdullah, H.R.; Ting, D.S.W.; Liu, N. Enhancing diagnostic accuracy through multi-agent conversations: Using large language models to mitigate cognitive bias. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.14589 2024.

- Goh, E.; Bunning, B.; Khoong, E.; Gallo, R.; Milstein, A.; Centola, D.; Chen, J.H. ChatGPT influence on medical decision-making, Bias, and equity: a randomized study of clinicians evaluating clinical vignettes. Medrxiv 2023.

- Omiye, J.A.; Lester, J.C.; Spichak, S.; Rotemberg, V.; Daneshjou, R. Large language models propagate race-based medicine. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Glocker, B.; Jones, C.; Roschewitz, M.; Winzeck, S. Risk of Bias in Chest Radiography Deep Learning Foundation Models. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, e230060. [CrossRef]

- Ktena, I.; Wiles, O.; Albuquerque, I.; Rebuffi, S.-A.; Tanno, R.; Roy, A.G.; Azizi, S.; Belgrave, D.; Kohli, P.; Cemgil, T.; et al. Generative models improve fairness of medical classifiers under distribution shifts. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1166–1173. [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Bunning, B.; Khoong, E.C.; Gallo, R.J.; Milstein, A.; Centola, D.; Chen, J.H. Physician clinical decision modification and bias assessment in a randomized controlled trial of AI assistance. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.O.; Afzal, M.M.; Mirza, S.; Fang, Y. How Fair are Medical Imaging Foundation Models? In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Health (ML4H). PMLR, 2023, pp. 217–231.

- Zheng, G.; Jacobs, M.A.; Braverman, V.; Parekh, V.S. Towards Fair Medical AI: Adversarial Debiasing of 3D CT Foundation Embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04386 2025.

- Benkirane, K.; Kay, J.; Perez-Ortiz, M. How Can We Diagnose and Treat Bias in Large Language Models for Clinical Decision-Making?. Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers). , Mexico; pp. 2263–2288.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- Yan, B.; Zeng, W.; Sun, Y.; Tan, W.; Zhou, X.; Ma, C. The Guideline for Building Fair Multimodal Medical AI with Large Vision-Language Model, 2024.

- Munia, N.; Imran, A.A.Z. Prompting Medical Vision-Language Models to Mitigate Diagnosis Bias by Generating Realistic Dermoscopic Images. 2025 IEEE 22nd International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). , United States; pp. 1–4.

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Keller, S.A.; de Hond, A.; van Buchem, M.M.; Pillai, M.; Hernandez-Boussard, T. Unveiling and Mitigating Bias in Mental Health Analysis with Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12033 2024.

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223 2023.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, .; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training, 2018.

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9.

- Solaiman, I.; Brundage, M.; Clark, J.; Askell, A.; Herbert-Voss, A.; Wu, J.; Radford, A.; Krueger, G.; Kim, J.W.; Kreps, S.; et al. Release strategies and the social impacts of language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.09203 2019.

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901.

- OpenAI. Introducing ChatGPT, 2022. Accessed: 2024-07-15.

- OpenAI. Introducing GPT-5 — openai.com. https://openai.com/index/introducing-gpt-5/, 2025. [Accessed 03-10-2025].

- Ye, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, N.; Zu, C.; Shao, Z.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Gong, C.; Shen, Y.; et al. A comprehensive capability analysis of gpt-3 and gpt-3.5 series models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10420 2023.

- Kalyan, K.S. A survey of GPT-3 family large language models including ChatGPT and GPT-4. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2023, 6. [CrossRef]

- AI, M. The Llama 4 herd: The beginning of a new era of natively multimodal intelligence. Meta AI Blog, 2025.

- Anthropic. Claude Opus 4 & Claude Sonnet 4 — System Card. Technical report, Anthropic, 2025.

- xAI. Grok 4 Model Card. Technical report, xAI, 2025.

- MistralAI. Mistral Medium 3.1. Meta AI Blog, 2025.

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.09388 2025.

- DeepSeek. DeepSeek-V3.1. API doc, 2025.

- Kimi.; Bai, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, G.; Chen, J.; Chen, N.; Chen, R.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Kimi k2: Open agentic intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.20534 2025.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 2020.

- Ramesh, A.; Pavlov, M.; Goh, G.; Gray, S.; Voss, C.; Radford, A.; Chen, M.; Sutskever, I. Zero-shot text-to-image generation. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. Pmlr, 2021, pp. 8821–8831.

- Alayrac, J.B.; Recasens, A.; Schneider, R.; Arandjelovic, R.; Botvinick, M.; Dehghani, M.; Clark, A.; et al.. Flamingo: a Visual Language Model for few-shot learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 35, 2022, pp. 23716–23729.

- Salehi, A.W.; Khan, S.; Gupta, G.; Alabduallah, B.I.; Almjally, A.; Alsolai, H.; Siddiqui, T.; Mellit, A. A Study of CNN and Transfer Learning in Medical Imaging: Advantages, Challenges, Future Scope. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5930. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Tang, B.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H. Entity recognition from clinical texts via recurrent neural network. BMC Med Informatics Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 67. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2019, 36, 1234–1240. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North. , United States; pp. 4171–4186.

- Huang, K.; Altosaar, J.; Ranganath, R. Clinicalbert: Modeling clinical notes and predicting hospital readmission. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.05342 2019.

- Luo, R.; Sun, L.; Xia, Y.; Qin, T.; Zhang, S.; Poon, H.; Liu, T.-Y. BioGPT: generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Hort, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.M.; Harman, M.; Sarro, F. Bias Mitigation for Machine Learning Classifiers: A Comprehensive Survey. Acm J. Responsible Comput. 2024, 1, 1–52. [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-T.; Yan, Y.; Liu, L.; Wan, Y.; Wang, W.; Chang, K.-W.; Lyu, M.R. Where Fact Ends and Fairness Begins: Redefining AI Bias Evaluation through Cognitive Biases. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2025. , China; pp. 10974–10993.

- Wang, W.; Bai, H.; Huang, J.-T.; Wan, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Qiu, H.; Peng, N.; Lyu, M. New Job, New Gender? Measuring the Social Bias in Image Generation Models. MM '24: The 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia. , Australia; pp. 3781–3789.

- Huang, J.-T.; Qin, J.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J. VisBias: Measuring Explicit and Implicit Social Biases in Vision Language Models. Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. , China; pp. 17981–18004.

- Du, Y.; Huang, J.t.; Zhao, J.; Lin, L. Faircoder: Evaluating social bias of llms in code generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.05396 2025.

- Shi, B.; Huang, J.t.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Z. Fairgamer: Evaluating biases in the application of large language models to video games. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.17825 2025.

- Rajkomar, A.; Oren, E.; Chen, K.; Dai, A.M.; Hajaj, N.; Hardt, M.; Liu, P.J.; Liu, X.; Marcus, J.; Sun, M.; et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. npj Digit. Med. 2018, 1, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, N.; Lin, Y.; Asudeh, A.; Jagadish, H.V. Representation Bias in Data: A Survey on Identification and Resolution Techniques. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–39. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, K.; Wong, K.F.; Wang, J. Understanding and Mitigating the Bias Inheritance in LLM-based Data Augmentation on Downstream Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04419 2025.

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Tierney, A.; Reed, M.; Grant, R.; Doo, F.; Payán, D.; Liu, V. Health Equity in the Era of Large Language Models. The American Journal of Managed Care 2025, 31, 112–117. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Jones, A.; Ndousse, K.; Askell, A.; Chen, A.; DasSarma, N.; Drain, D.; Fort, S.; Ganguli, D.; Henighan, T.; et al. Training a helpful and harmless assistant with reinforcement learning from human feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.05862 2022.

- Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Lei, J.; Liu, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, P.; Gu, J.; Chu, Z.; Qin, Z.; et al. A Survey on Medical Large Language Models: Technology, Application, Trustworthiness, and Future Directions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.03712 2024.

- Zheng, Y.; Gan, W.; Chen, Z.; Qi, Z.; Liang, Q.; Yu, P.S. Large language models for medicine: a survey. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2024, 16, 1015–1040. [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Cassee, N.; Serebrenik, A.; Bavota, G.; Novielli, N.; Lanza, M. Opinion Mining for Software Development: A Systematic Literature Review. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2022, 31, 1–41. [CrossRef]

- Jalali, S.; Wohlin, C. Systematic literature studies: database searches vs. backward snowballing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM-IEEE international symposium on Empirical software engineering and measurement, 2012, pp. 29–38.

- Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Babar, M.A.; Yang, S. Synthesizing qualitative research in software engineering: A critical review. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th international conference on software engineering, 2018, pp. 1207–1218.

- Schnepper, R.; Roemmel, N.; Schaefert, R.; Lambrecht-Walzinger, L.; Meinlschmidt, G. Exploring Biases of Large Language Models in the Field of Mental Health: Comparative Questionnaire Study of the Effect of Gender and Sexual Orientation in Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa Case Vignettes. JMIR Ment. Heal. 2025, 12, e57986–e57986. [CrossRef]

- Akhras, N.; Antaki, F.; Mottet, F.; Nguyen, O.; Sawhney, S.; Bajwah, S.; Davies, J.M. Large language models perpetuate bias in palliative care: development and analysis of the Palliative Care Adversarial Dataset (PCAD). arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.08073 2025.

- Rani, M.; Mishra, B.K.; Thakker, D.; Babar, M.; Jones, W.; Din, A. Biases and Trustworthiness Challenges with Mitigation Strategies for Large Language Models in Healthcare. 2024 International Conference on IT and Industrial Technologies (ICIT). , Pakistan; pp. 1–6.

- Templin, T.; Fort, S.; Padmanabham, P.; Seshadri, P.; Rimal, R.; Oliva, J.; Lich, K.H.; Sylvia, S.; Sinnott-Armstrong, N. Framework for bias evaluation in large language models in healthcare settings. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Young, C.C.; Enichen, E.; Rao, A.; Succi, M.D. Racial, ethnic, and sex bias in large language model opioid recommendations for pain management. PAIN® 2024, 166, 511–517. [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.; Soffer, S.; Agbareia, R.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Apakama, D.U.; Horowitz, C.R.; Charney, A.W.; Freeman, R.; Kummer, B.; Glicksberg, B.S.; et al. Sociodemographic biases in medical decision making by large language models. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1873–1881. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Harman, M. "Ignorance and Prejudice" in Software Fairness. 2021 IEEE/ACM 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE). , COUNTRY; pp. 1436–1447.

- Segura, S.; Fraser, G.; Sanchez, A.B.; Ruiz-Cortés, A. A survey on metamorphic testing. IEEE Transactions on software engineering 2016, 42, 805–824.

- Chen, T.Y.; Kuo, F.C.; Liu, H.; Poon, P.L.; Towey, D.; Tse, T.; Zhou, Z.Q. Metamorphic testing: A review of challenges and opportunities. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1–27.

- Qian, R.; Ross, C.; Fernandes, J.; Smith, E.M.; Kiela, D.; Williams, A. Perturbation Augmentation for Fairer NLP. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. , United Arab Emirates; pp. 9496–9521.

- Lu, K.; Mardziel, P.; Wu, F.; Amancharla, P.; Datta, A. Gender bias in neural natural language processing. Logic, language, and security: essays dedicated to Andre Scedrov on the occasion of his 65th birthday 2020, pp. 189–202.

- Ravfogel, S.; Elazar, Y.; Gonen, H.; Twiton, M.; Goldberg, Y. Null It Out: Guarding Protected Attributes by Iterative Nullspace Projection. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. , COUNTRY; pp. 7237–7256.

- Iskander, S.; Radinsky, K.; Belinkov, Y. Shielded Representations: Protecting Sensitive Attributes Through Iterative Gradient-Based Projection. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023. , Canada; pp. 5961–5977.

- Bartl, M.; Nissim, M.; Gatt, A. Unmasking contextual stereotypes: Measuring and mitigating BERT’s gender bias. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.14534 2020.

- Han, X.; Baldwin, T.; Cohn, T. Balancing out Bias: Achieving Fairness Through Balanced Training. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. , United Arab Emirates; pp. 11335–11350.

- Liu, H.; Dacon, J.; Fan, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J. Does Gender Matter? Towards Fairness in Dialogue Systems. Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. , Spain; pp. 4403–4416.

- Huang, P.-S.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, R.; Stanforth, R.; Welbl, J.; Rae, J.; Maini, V.; Yogatama, D.; Kohli, P. Reducing Sentiment Bias in Language Models via Counterfactual Evaluation. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020. , COUNTRY; pp. 65–83.

- Gehman, S.; Gururangan, S.; Sap, M.; Choi, Y.; Smith, N.A. RealToxicityPrompts: Evaluating Neural Toxic Degeneration in Language Models. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020. , COUNTRY; pp. 3356–3369.

- Xu, J.; Ju, D.; Li, M.; Boureau, Y.L.; Weston, J.; Dinan, E. Recipes for safety in open-domain chatbots. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.07079 2020.

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.M.; Sarro, F.; Harman, M. MAAT: a novel ensemble approach to addressing fairness and performance bugs for machine learning software. ESEC/FSE '22: 30th ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering. , Singapore; pp. 1122–1134.

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.M.; Liu, Y.; Mousavi, M.R.; Liu, S.; Xue, D. MirrorFair: Fixing Fairness Bugs in Machine Learning Software via Counterfactual Predictions. Proc. ACM Softw. Eng. 2024, 1, 2121–2143. [CrossRef]

- Tokpo, E.K.; Calders, T. Text Style Transfer for Bias Mitigation using Masked Language Modeling. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies: Student Research Workshop. , United States; pp. 163–171.

- Dhingra, H.; Jayashanker, P.; Moghe, S.; Strubell, E. Queer people are people first: Deconstructing sexual identity stereotypes in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.00101 2023.

- Yang, K.; Yu, C.; Fung, Y.R.; Li, M.; Ji, H. ADEPT: A DEbiasing PrompT Framework. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 10780–10788. [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, Z.; Xing, C.; Liu, W.; Xiong, C. Improving Gender Fairness of Pre-Trained Language Models without Catastrophic Forgetting. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers). , Canada; pp. 1249–1262.

- Chakraborty, J.; Majumder, S.; Menzies, T. Bias in machine learning software: why? how? what to do? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, 2021, pp. 429–440.

- Chakraborty, J.; Majumder, S.; Yu, Z.; Menzies, T. Fairway: a way to build fair ML software. ESEC/FSE '20: 28th ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering. , USA; pp. 654–665.

- Kamiran, F.; Calders, T. Data preprocessing techniques for classification without discrimination. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2011, 33, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Chakraborty, J.; Menzies, T. FairMask: Better Fairness via Model-Based Rebalancing of Protected Attributes. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2022, 49, 2426–2439. [CrossRef]

- Lauscher, A.; Lueken, T.; Glavaš, G. Sustainable Modular Debiasing of Language Models. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021. , Dominican Republic; pp. 4782–4797.

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3.

- White, J.; Fu, Q.; Hays, S.; Sandborn, M.; Olea, C.; Gilbert, H.; Elnashar, A.; Spencer-Smith, J.; Schmidt, D.C. A prompt pattern catalog to enhance prompt engineering with chatgpt. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.11382 2023.

- Anthropic. Home - Claude Docs — docs.claude.com. https://docs.claude.com/en/home, 2025. [Accessed 04-10-2025].

- AI, M. La Plateforme - frontier LLMs | Mistral AI — mistral.ai. https://mistral.ai/products/la-plateforme, 2025. [Accessed 04-10-2025].

- Singhal, K.; Tu, T.; Gottweis, J.; Sayres, R.; Wulczyn, E.; Amin, M.; Hou, L.; Clark, K.; Pfohl, S.R.; Cole-Lewis, H.; et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 943–950. [CrossRef]

- Writer. Palmyra Med: Instruction-Based Fine-Tuning of LLMs Enhancing Medical Domain Performance. https://writer.com/engineering/palmyra-med-instruction-based-fine-tuning-medical-domain-performance/, 2023.

- Chen, Z.; Tang, A.; Vu, T.; et al.. MEDITRON-70B: Scaling Medical Pretraining for Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.16079 2023.

- Saama AI Labs. OpenBioLLM-70B (Llama3): An Open-Source Biomedical Language Model. https://huggingface.co/aaditya/Llama3-OpenBioLLM-70B, 2024.

- Wu, C.; Lin, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y. PMC-LLaMA: toward building open-source language models for medicine. J. Am. Med Informatics Assoc. 2024, 31, 1833–1843. [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Adams, L.C.; Papaioannou, J.M.; Grundmann, P.; Oberhauser, T.; Figueroa, A.; Löser, A.; Truhn, D.; Bressem, K.K. MedAlpaca – An Open-Source Collection of Medical Conversational AI Models and Training Data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08247 2023.

- Xiong, H.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q.; Shen, D. DoctorGLM: Fine-tuning your Chinese Doctor is not a Herculean Task. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.01097 2023.

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Xi, N.; Qiang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Qin, B.; Liu, T. HuaTuo: Tuning LLaMA Model with Chinese Medical Knowledge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.06975 2023.

- Shin, H.C.; Peng, Y.; Bodur, E.; et al.. BioMegatron: Larger Biomedical Domain Language Model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of EMNLP, 2020.

- Li, C.; et al.. LLaVA-Med: Training a Large Language-and-Vision Assistant for Biomedicine in One Day. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.00890 2023.

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Dan, R.; Zhang, Y. ChatDoctor: A Medical Chat Model Fine-tuned on LLaMA Model using Medical Domain Knowledge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.14070 2023.

- Labrak, Y.; Bazoge, A.; Morin, E.; Gourraud, P.-A.; Rouvier, M.; Dufour, R. BioMistral: A Collection of Open-Source Pretrained Large Language Models for Medical Domains. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics ACL 2024. , Thailand; pp. 5848–5864.

- John Snow Labs. JSL-MedLlama-3-8B-v2.0. https://huggingface.co/johnsnowlabs/JSL-MedLlama-3-8B-v2.0, 2024.

- Alsentzer, E.; Murphy, J.R.; Boag, W.; Weng, W.H.; Jin, D.; Naumann, T.; McDermott, M. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd Clinical NLP Workshop, 2019.

- Gupta, A.; Osman, I.; Shehata, M.S.; Braun, W.J.; Feldman, R.E. MedMAE: A Self-Supervised Backbone for Medical Imaging Tasks. Computation 2025, 13, 88. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Agarwal, D.; Sun, J. MedCLIP: Contrastive Learning from Unpaired Medical Images and Text. Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. , United Arab Emirates; pp. 3876–3887.

- Eslami, S.; Benitez-Quiroz, F.; Martinez, A.M. How Much Does CLIP Benefit Visual Question Answering in the Medical Domain? In Proceedings of the Findings of EACL, 2023.

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; et al.. BiomedCLIP: A Multimodal Biomedical Foundation Model Pretrained from Fifteen Million Scientific Image-Text Pairs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.00915 2023.

- Ji, S.; Camacho-Collados, E.; Aletras, N.; Yang, Y.; et al.. Publicly Available Pretrained Language Models for Mental Healthcare. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.15621 2021.

- Zhang, K.; Liu, D. Customized Segment Anything Model for Medical Image Segmentation (SAMed). arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.13785 2023.

- Yang, X.; Chen, A.; PourNejatian, N.; Shin, H.C.; Smith, K.E.; Parisien, C.; Compas, C.; Martin, C.; Costa, A.B.; Flores, M.G.; et al. A large language model for electronic health records. npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Tiu, E.; Talius, E.; Patel, P.; Langlotz, C.P.; Ng, A.Y.; Rajpurkar, P. Expert-level detection of pathologies from unannotated chest X-ray images via self-supervised learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 1399–1406. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, M.; Alambo, A.; Shalin, V.; Kursuncu, U.; Thirunarayan, K.; Sheth, A.; Pathak, J.; et al. Reddit C-SSRS Suicide Dataset. Zenodo, 2019.

- Garg, M.; Kokkodis, M.; Khan, A.; Morency, L.P.; Choudhury, M.D.; Hussain, M.S.A.; et al. CAMS: Causes for Mental Health Problems—A New Task and Dataset. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of LREC, 2022.

- Liu, J.; Zhou, P.; Hua, Y.; Chong, D.; Tian, Z.; Liu, A.; Wang, H.; You, C.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, L.; et al. Benchmarking large language models on cmexam-a comprehensive chinese medical exam dataset. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Wang, Y.; et al. Unveiling and Mitigating Bias in Mental Health Analysis Using Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12033 2024. Uses the DepEmail dataset.

- Turcan, I.; McKeown, K. Dreaddit: A Reddit Dataset for Stress Analysis in Social Media. In Proceedings of the EMNLP-IJCNLP, 2019.

- Pampari, A.; Raghavan, P.; Liang, J.; Peng, J. emrQA: A Large Corpus for Question Answering on Electronic Medical Records. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. , Belgium; .

- Link, K. EquityMedQA Dataset Card. Hugging Face Dataset, 2024.

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Chen, J.; Fu, J.; Wan, X.; et al. Huatuo-26M, a Large-scale Chinese Medical QA Dataset. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025. , Mexico; pp. 3828–3848.

- DBMI, Harvard Medical School. i2b2 Data Portal. Website, 2024.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility (IRF) Compare / Provider Data Catalog. Website, 2024.

- Jin, D.; Pan, E.; Oufattole, N.; Weng, W.-H.; Fang, H.; Szolovits, P. What Disease Does This Patient Have? A Large-Scale Open Domain Question Answering Dataset from Medical Exams. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6421. [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Umapathi, L.K.; Sankarasubbu, M. Medmcqa: A large-scale multi-subject multi-choice dataset for medical domain question answering. In Proceedings of the Conference on health, inference, and learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 248–260.

- Garg, M.; Liu, X.; Sathvik, M.; Raza, S.; Sohn, S. MultiWD: Multi-label wellness dimensions in social media posts. J. Biomed. Informatics 2024, 150, 104586. [CrossRef]

- DBMI, Harvard Medical School. n2c2 NLP Research Datasets. Website, 2024.

- Zhao, Z.; Jin, Q.; Chen, F.; Peng, T.; Yu, S. A large-scale dataset of patient summaries for retrieval-based clinical decision support systems. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Dhingra, B.; Liu, Z.; Cohen, W.; Lu, X. PubMedQA: A Dataset for Biomedical Research Question Answering. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). , China; pp. 2567–2577.

- PhysioNet. Q-Pain: Evaluation Datasets for Clinical Decision Support Systems (PhysioNet). Dataset on PhysioNet, 2023.

- Mauriello, M.L.; Lincoln, T.; Hon, G.; Simon, D.; Jurafsky, D.; Paredes, P. SAD: A Stress Annotated Dataset for Recognizing Everyday Stressors in SMS-like Conversational Systems. CHI '21: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. , Japan; pp. 1–7.

- SKMCH&RC. Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre Cancer Registry. Website, 2024.

- Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Yang, K.; Yasunaga, M.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, I.; Yao, Q.; Roman, S.; et al. Spider: A Large-Scale Human-Labeled Dataset for Complex and Cross-Domain Semantic Parsing and Text-to-SQL Task. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. , Belgium; .

- AIMH. SWMH Dataset Card. Hugging Face Dataset, 2025.

- Gao, L.; Biderman, S.; Black, S.; et al. The Pile: An 800GB Dataset of Diverse Text for Language Modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.00027 2021.

- Vishnubhotla, K.; Cook, P.; Hirst, G. Emotion Word Usage in Tweets from US and Canada (TUSC). arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.04862 2022.

- Jr., C.R.J.; Weiner, M.W.; et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2008.

- Litjens, G.; Bandi, P.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Geessink, O.; Balkenhol, M.; Bult, P.; Halilovic, A.; Hermsen, M.; van de Loo, R.; Vogels, R.; et al. 1399 H&E-stained sentinel lymph node sections of breast cancer patients: the CAMELYON dataset. GigaScience 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Da, Q.; Liu, X.; Gao, X.; Shen, J.; He, J.; Shen, T.; et al. ChestDR: Thoracic Diseases Screening in Chest Radiography, 2023. [CrossRef].

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Lu, L.; Lu, Z.; Bagheri, M.; Summers, R.M. ChestX-ray8: Hospital-scale Chest X-ray Database and Benchmarks on Weakly-Supervised Classification and Localization of Common Thorax Diseases. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2017.

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Da, Q.; Liu, X.; Gao, X.; Shen, J.; He, J.; Shen, T.; et al. ColonPath: Tumor Tissue Screening in Pathology Patches, 2023. [CrossRef].

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180161. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. Ieee, 2009, pp. 248–255.

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Da, Q.; Liu, X.; Gao, X.; Shen, J.; He, J.; Shen, T.; et al. A Real-world Dataset and Benchmark For Foundation Model Adaptation in Medical Image Classification. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.; Candemir, S.; Antani, S.; Wáng, Y.-X.J.; Lu, P.-X.; Thoma, G. Two public chest X-ray datasets for computer-aided screening of pulmonary diseases. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2014, 4, 475–477.

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Da, Q.; Liu, X.; et al. NeoJaundice: Neonatal Jaundice Evaluation in Demographic Images. https://springernature.figshare.com/articles/dataset/NeoJaundice_Neonatal_Jaundice_Evaluation_in_Demographic_Images/22302559, 2023.

- Peking University & Grand-Challenge. Ocular Disease Intelligent Recognition (ODIR-2019) Dataset. https://odir2019.grand-challenge.org/dataset/, 2019.

- Rath, S.R. Diabetic Retinopathy 224x224 (2019 Data). https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sovitrath/diabetic-retinopathy-224x224-2019-data, 2019.

- National Eye Institute. NEI Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000001.v3.p1, 2001.

- Nakayama, L.F.; de Souza, F.; Vieira, G.; et al. BRSET: A Brazilian Multilabel Ophthalmological Dataset of Fundus Photographs. PLOS Digital Health 2024. [CrossRef].

- Kennedy, D.N.; Haselgrove, C.; Hodge, S.M.; et al. CANDIShare: A Resource for Pediatric Neuroimaging Data. Neuroinformatics 2012.

- Wu, J.T.; Moradi, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Chest ImaGenome Dataset for Clinical Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.00316 2021.

- Irvin, J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Ko, M.; Yu, Y.; Ciurea-Ilcus, S.; Chute, C.; Marklund, H.; Haghgoo, B.; Ball, R.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al. CheXpert: A Large Chest Radiograph Dataset with Uncertainty Labels and Expert Comparison. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2019, 33, 590–597. [CrossRef]

- Afshar, P.; Heidarian, S.; Enshaei, N.; Naderkhani, F.; Rafiee, M.J.; Oikonomou, A.; Fard, F.B.; Samimi, K.; Plataniotis, K.N.; Mohammadi, A. COVID-CT-MD, COVID-19 computed tomography scan dataset applicable in machine learning and deep learning. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, F.; et al. FairSeg: A Large-Scale Medical Image Segmentation Dataset for Fairness Learning. ICLR 2024 (proc. abstract) / arXiv:2311.02189 2024.

- Luo, Y.; Shi, M.; Khan, M.O.; Afzal, M.M.; Huang, H.; Yuan, S.; Tian, Y.; Song, L.; Kouhana, A.; Elze, T.; et al. FairCLIP: Harnessing Fairness in Vision-Language Learning. 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). , United States; pp. 12289–12301.

- Luo, Y.; Tian, Y.; Shi, M.; Pasquale, L.R.; Shen, L.Q.; Zebardast, N.; Elze, T.; Wang, M. Harvard Glaucoma Fairness: A Retinal Nerve Disease Dataset for Fairness Learning and Fair Identity Normalization. IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 2024, 43, 2623–2633. [CrossRef]

- IRCAD. 3D-IRCADb-01: Liver Segmentation Dataset. https://www.ircad.fr/research/data-sets/liver-segmentation-3d-ircadb-01/, 2010.

- Heller, N.; Sathianathen, N.; Kalapara, A.; et al. The KiTS19 Challenge Data: 300 Kidney Tumor Cases with Clinical Context, CT Semantic Segmentations, and Surgical Outcomes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.00445 2019.

- MIDRC Consortium. Medical Imaging and Data Resource Center (MIDRC). https://www.midrc.org/midrc-data, 2021.

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Berkowitz, S.J.; Greenbaum, N.R.; Lungren, M.P.; Deng, C.-Y.; Mark, R.G.; Horng, S. MIMIC-CXR, a de-identified publicly available database of chest radiographs with free-text reports. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Shen, L.; Lehman, L.-W.H.; Feng, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Moody, B.; Szolovits, P.; Celi, L.A.; Mark, R.G. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160035. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Bulgarelli, L.; Shen, L.; Gayles, A.; Shammout, A.; Horng, S.; Pollard, T.J.; Hao, S.; Moody, B.; Gow, B.; et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Child and Family Data Archive. Migrant and Seasonal Head Start Study (MSHS), United States, 2017-2018. https://www.childandfamilydataarchive.org/cfda/archives/cfda/studies/37348, 2019.

- Abdulnour, R.E.E.; Kachalia, A. Deliberate Practice at the Virtual Bedside to Improve Diagnostic Reasoning. NEJM 2022. Describes NEJM Healer approach.

- Kass, M.A.; Heuer, D.K.; Higginbotham, E.J.; et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: A Randomized Trial Determines that Topical Ocular Hypotensive Medication Delays or Prevents the Onset of Primary Open-angle Glaucoma. Archives of Ophthalmology 2002. [CrossRef].

- Chaves, J.M.Z.; Patel, B.; Chaudhari, A.; et al. Opportunistic Assessment of Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Using Abdominopelvic CT and Medical Record Data: A Multimodal Explainable AI Approach. NPJ Digital Medicine 2023. Releases the OL3I dataset.

- Pacheco, A.G.; Lima, G.R.; Salomão, A.S.; Krohling, B.; Biral, I.P.; de Angelo, G.G.; Jr, F.C.A.; Esgario, J.G.; Simora, A.C.; Castro, P.B.; et al. PAD-UFES-20: A skin lesion dataset composed of patient data and clinical images collected from smartphones. Data Brief 2020, 32, 106221. [CrossRef]

- Bustos, A.; Pertusa, A.; Salinas, J.-M.; de la Iglesia-Vayá, M. PadChest: A large chest x-ray image dataset with multi-label annotated reports. Med Image Anal. 2020, 66, 101797. [CrossRef]

- Kovalyk, O.; Remeseiro, B.; Ortega, M.; et al. PAPILA: Dataset with Fundus Images and Clinical Data of Both Eyes of the Same Patient for Glaucoma Assessment. Scientific Data 2022. [CrossRef].

- Nguyen, H.Q.; Lam, K.; Le, L.T.; Pham, H.H.; Tran, D.Q.; Nguyen, D.B.; Le, D.D.; Pham, C.M.; Tong, H.T.T.; Dinh, D.H.; et al. VinDr-CXR: An open dataset of chest X-rays with radiologist’s annotations. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Manes, V.J.; Han, H.; Han, C.; Kil Cha, S.; Egele, M.; Schwartz, E.J.; Woo, M. The Art, Science, and Engineering of Fuzzing: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2019, 47, 2312–2331. [CrossRef]

- McKeeman, W.M. Differential testing for software. Digital Technical Journal 1998, 10, 100–107.

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.M.; Sarro, F.; Harman, M. Fairness Improvement with Multiple Protected Attributes: How Far Are We?. ICSE '24: IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering. , Portugal; pp. 1–13.

- Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.M.; Sun, W.; Xiao, Y.; Li, T.; Lou, Y.; Liu, Y. Software Fairness Dilemma: Is Bias Mitigation a Zero-Sum Game?. Proc. ACM Softw. Eng. 2025, 2, 1780–1801. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.M.; Sarro, F.; Liu, Y. Diversity Drives Fairness: Ensemble of Higher Order Mutants for Intersectional Fairness of Machine Learning Software. 2025 IEEE/ACM 47th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE). , Canada; pp. 743–755.

| Mitigation Taxonomy | Description | Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Processing | Mitigate bias before model training | Training Data Debugging [120,121] Projection-based Mitigation [122,123] |

| In-Processing | Mitigate bias during model training | Model Fine-tuning [21,90] Architecture Modification [124,125] Loss Function Modification [126,127] Decoding Strategy Modification [128,129] |

| Post-Processing | Mitigate bias after model training | Output Ensemble [130,131] Output Rewriting [132,133] Prompt Engineering [134,135] |

| Model Name | Models Family | Parameter Size | Year | Open Source | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Med-PaLM [24] | PaLM | >= 175B | 2022 | No | Med-PaLM |

| Med-PaLM2 [145] | PaLM 2 | >= 175B | 2023 | No | Med-PaLM2 |

| PaLMrya-Med [146] | PaLMrya-Med | 70B - 175B | 2023 | Yes | PaLMrya-Med |

| Meditron [147] | LlaMa-2 | 70B - 175B | 2023 | Yes | Meditron |

| OpenBioLLM [148] | LlaMa-2 | 70B - 175B | 2023 | Yes | OpenBioLLM |

| PMC-LlaMa [149] | LlaMa | 10B - 70B | 2023 | Yes | PMC-LlaMa |

| MedAlpaca [150] | LlaMa | 10B - 70B | 2023 | Yes | MedAlpaca |

| DoctorGLM [151] | ChatGLM | 10B - 70B | 2023 | Yes | DoctorGLM |

| Huatuo [152] | LlaMa | 10B - 70B | 2023 | Yes | Huatuo |

| BioMegatron [153] | Megatron-LM | 1B - 10B | 2021 | Yes | BioMegatron |

| LLaVA-Med [154] | LLaVA | 1B - 10B | 2024 | Yes | LLaVA-Med |

| ChatDoctor [155] | LlaMa | 1B - 10B | 2023 | Yes | ChatDoctor |

| BioMistral [156] | Mistral | 1B - 10B | 2024 | Yes | BioMistral |

| MedLlaMa-3 [157] | LlaMa-3 | 1B - 10B | 2024 | Yes | MedLlaMa-3 |

| BioBERT [89] | BioBERT | < 1B | 2019 | Yes | BioBERT |

| ClinicalBERT [158] | ClinicalBERT | < 1B | 2019 | Yes | ClinicalBERT |

| BioGPT [92] | GPT | < 1B | 2022 | Yes | BioGPT |

| MedMAE [159] | MAE | < 1B | 2023 | Yes | MedMAE |

| MedCLIP [160] | CLIP | < 1B | 2022 | Yes | MedCLIP |

| PubMedCLIP [161] | CLIP | < 1B | 2023 | Yes | PubMedCLIP |

| BiomedCLIP [162] | CLIP | < 1B | 2023 | Yes | BiomedCLIP |

| MentalBERT [163] | BERT | < 1B | 2021 | Yes | MentalBERT |

| SAMed [164] | SAM | < 1B | 2023 | Yes | SAMed |

| GatorTron [165] | GatotTron | < 1B | 2021 | Yes | GatorTron |

| CheXzero [166] | CLIP | < 1B | 2022 | Yes | CheXzero |

| Name | Sources | Related Diseases | Sensitive Attributes | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMQA [49] | United States | General medical dataset | Race, Sex, Socioeconomic Status | AMQA |

| BiasMD [53] | Canada | General medical dataset | Disability, Religion Belief, Sexuality, Socioeconomic Status | BiasMD |

| BiasMedQA [47] | United States | General medical dataset | Cognitive | BiasMedQA |

| C-SSRS [167] | United States | Mental health | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | C-SSRS |

| CAMS [168] | Global | Mental health | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | CAMS |

| CMExam [169] | China | General medical dataset | Cultural Context, Language | CMExam |

| CPV [62] | United States | General medical dataset | Race, Sex | CPV |

| Cross-Care [17] | United States | General medical dataset | Race, Sex | Cross-Care |

| DepEmail [170] | United States | Depression, Mental health | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | DepEmail |

| DiseaseMatcher [53] | Not Specified | General medical dataset | Race, Religion Belief, Socioeconomic Status | DiseaseMatcher |

| Dreaddit [171] | United States | Mental health | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | Dreaddit |

| emrQA [172] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | emrQA |

| EquityMedQA [173] | Not Specified | General medical dataset | Race, Sex, Socioeconomic Status | EquityMedQA |

| Huatuo-26M [174] | China | General medical dataset | Cultural Context, Language | Huatuo-26M |

| I2B2 [175] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | I2B2 |

| IRF [176] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | IRF |

| MedQA [177] | China, United States | General medical dataset | Cultural Context, Language | MedQA |

| MedMCQA [178] | India | General medical dataset | Cultural Context, Language | MedMCQA |

| MultiWD [179] | Not Specified | Mental health | Age | MultiWD |

| N2C2 [180] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Race, Sex | N2C2 |

| PMC-Patients [181] | Not Specified | General medical dataset | Race | PMC-Patients |

| PubMedQA [182] | Not Specified | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | PubMedQA |

| Q-Pain [183] | Not Specified | General medical dataset | Race, Sex | Q-Pain |

| StressAnnotatedDataset [184] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | StressAnnotatedDataset |

| SKMCH&RC [185] | Pakistan | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | SKMCH&RC |

| SPIDER [186] | United States | General medical dataset | Language | SPIDER |

| SWMH [187] | Not Specified | Mental health | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | SWMH |

| The Pile [188] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | The Pile |

| TUSC [189] | Canada, United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | TUSC |

| Name | Sources | Related Diseases | Sensitive Attributes | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADNI-1.5T [190] | United States | Alzheimer’s disease | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex, Socioeconomic Status | ADNI-1.5T |

| CAMELYON17 [191] | Netherlands | Breast cancer | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | CAMELYON17 |

| ChestDR [192] | China | General Medical Dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | ChestDR |

| ChestXray14 [193] | United States | Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Pleural effusion | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | ChestXray14 |

| ColonPath [194] | China | Colorectal cancer, Gastrointestinal lesions | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | ColonPath |

| HAM10000 [195] | Australia, Austria | Actinic keratoses, Dermatofibroma, Intraepithelial carcinoma, Vascular lesions | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | HAM10000 |

| ImageNet [196] | Global | General dataset | Age, Cultural Context, Nationality, Race, Sex | ImageNet |

| MedFMC [197] | China | Colorectal lesions, Diabetic retinopathy, Neonatal jaundice, Pneumonia | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | MedFMC |

| Montgomery-County-X-ray [198] | United States | Tuberculosis (TB) | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | Montgomery-County-X-ray |

| NeoJaundice [199] | China | Neonatal jaundice | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | NeoJaundice |

| ODIR [200] | China | Age-related macular degeneration, Cataracts, Diabetes, Glaucoma, Hypertension, Myopia | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | ODIR |

| Retino [201] | Not Specified | Diabetic retinopathy | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | Retino |

| Name | Sources | Related Diseases | Sensitive Attributes | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AREDS [202] | United States | Age-related macular degeneration, Cataracts | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | AREDS |

| BRSET [203] | Brazil | Diabetic retinopathy | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | BRSET |

| CANDI [204] | United States | Neurodevelopmental disorders, Schizophrenia | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | CANDI |

| Chest-ImaGenome [205] | United States | Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Pleural effusion, Pneumonia | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | Chest-ImaGenome |

| CheXpert [206] | United States | Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Consolidation, Pleural effusion, Pulmonary Edema | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | CheXpert |

| COVID-CT-MD [207] | Iran | COVID-19 | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | COVID-CT-MD |

| FairSeg [208] | United States | Glaucoma | Language, Marital Status, Race, Sex | FairSeg |

| FairVLMed10k [209] | United States | Glaucoma | Language, Marital Status, Race, Sex | FairVLMed10k |

| GF3300 [210] | United States | Glaucoma | Age, Language, Marital Status, Race, Sex | GF3300 |

| IRCADb [211] | France | Liver tumors | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | IRCADb |

| KiTS [212] | United States | Kidney cancer | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | KiTS |

| MIDRC [213] | United States | COVID-19 | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | MIDRC |

| MIMIC-CXR [214] | United States | Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Pleural effusion, Pneumonia | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | MIMIC-CXR |

| MIMIC-III [215] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | MIMIC-III |

| MIMIC-IV [216] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | MIMIC-IV |

| MSHS [217] | United States | General medical dataset | Race, Sex, Socioeconomic Staus | MSHS |

| NEJM Healer Cases [218] | United States | General medical dataset | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | NEJM Healer Cases |

| OHTS [219] | United States | Glaucoma | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | OHTS |

| OL3I [220] | United States | Ischemic heart disease | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | OL3I |

| PAD-UFES-20 [221] | Brazil | Actinic Keratosis, Basal Cell Carcinoma, Melanoma, Nevus, Seborrheic Keratosis, Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | PAD-UFES-20 |

| PadChest [222] | Spain | Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Emphysema, Fibrosis, Hernia, Nodule, Pleural effusion, Pneumonia, Pneumothorax | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | PadChest |

| PAPILA [223] | Spain | Glaucoma | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | PAPILA |

| VinDr [224] | Vietnam | Breast cancer, Nodule, Pneumonia, Pneumothorax | Age, Nationality, Race, Sex | VinDr |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).