1. Introduction

Psoriatic disease (PsD) encompasses a heterogeneous group of inflammatory disorders, including psoriasis (PsO) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), characterized by variable involvement of the skin, nails, peripheral joints, axial skeleton, and entheses. Beyond musculoskeletal and cutaneous domains, PsD is associated with a substantially increased burden of cardiometabolic comorbidity, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and established cardiovascular disease (CVD). The excess cardiovascular risk in PsD is driven by a combination of traditional risk factors, systemic inflammation, and potential adverse effects of certain therapies. These comorbidities contribute to reduced life expectancy, poorer quality of life, and higher healthcare costs [

1,

2,

3].

Although numerous epidemiological studies have established the association between PsD and increased cardiometabolic risk, most research has treated these comorbidities as isolated variables rather than as components of integrated phenotypes. This approach may overlook clinically relevant subgroups in which specific constellations of disease features and comorbidities cluster together, leading to different prognoses and therapeutic needs [

1,

2,

3]. Identifying such “cardiometabolic endotypes” could facilitate more personalized risk stratification and management strategies, allowing clinicians to target preventive and therapeutic interventions more effectively [

4].

The concept of endotyping—subdividing a heterogeneous disease into biologically or clinically distinct subgroups—has been successfully applied in other chronic inflammatory disorders such as asthma and inflammatory bowel disease [

5]. In rheumatology, cluster analysis and latent class analysis (LCA) have been increasingly used to uncover phenotypes in diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus and axial spondyloarthritis [

6,

7]. However, comparable approaches in PsD focusing on cardiometabolic clustering remain scarce, and studies integrating both PsO and PsA populations in the same analytic framework are virtually absent.

Given the diversity of PsD presentations, it is plausible that the cardiometabolic burden varies not only in magnitude but also in qualitative composition across subgroups. For example, some patients may present with high skin activity and minimal joint disease but accumulate significant metabolic risk factors, whereas others may display severe musculoskeletal involvement with a relatively benign metabolic profile. Understanding these patterns could improve clinical monitoring, optimize therapeutic choices, and inform cardiovascular prevention programs.

In this study, we applied unsupervised clustering methods to a well-characterized cohort of patients with PsD, including both PsO-only and PsA subgroups, to identify and characterize distinct cardiometabolic phenotypes. We focused on core demographic and disease-related variables (age, sex, disease duration, arthritis status, HLA-Cw6, PASI, systemic treatment, and cardiovascular disease history) to derive the clusters and then profiled each subgroup according to the prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking, and liver disease). We further validated our findings using a model-based LCA approach, explored disease-stratified clustering, and evaluated predictors of the “high-risk” phenotype. Our primary objective was to describe clinically meaningful cardiometabolic endotypes within PsD and to discuss their potential implications for individualized patient care and future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We performed a cross-sectional observational study including adult patients with PsD, defined as either PsO without arthritis or PsA fulfilling the CASPAR criteria [

8], who attended a specialized dermatology-rheumatology clinic. The study included consecutive adult patients attending the dermatology–rheumatology joint clinic at the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Given the exploratory nature of the analysis, the sample size corresponded to all eligible patients with complete data during the recruitment period. All patients had complete demographic and clinical data available for the variables of interest and provided informed consent for the use of anonymized data for research purposes. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (approval number CEImPA-214/2023).

2.2. Variables

For cluster derivation, we selected eight core variables based on their clinical relevance and potential relationship to cardiometabolic status: age (years), disease duration, sex, arthritis status, HLA-Cw6 status, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), systemic therapy use, cardiovascular disease history. The following cardiovascular risk factors were excluded from the clustering procedure and used exclusively for profiling the resulting clusters: high blood pressure (HBP), diabetes mellitus type 1 or type 2 (DM), dyslipidemia, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), current smoking, liver disease (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease).

2.3. Data Preprocessing

Binary variables were encoded as 0/1. Continuous variables (age, disease duration, PASI) were retained as numeric values. Missing values were imputed using the median for continuous and binary variables alike. All clustering variables were standardized to z-scores prior to analysis to ensure equal contribution to the distance metrics.

2.4. Clustering Procedures

We applied k-means clustering for k values from 3 to 6, each with 50 random initializations. Cluster validity was assessed using the silhouette coefficient, Calinski–Harabasz index, and within-cluster sum of squares (inertia). The number of clusters was chosen based on optimal validity indices and clinical interpretability.

2.5. Validation and Additional Analyses

To validate the primary k-means solution, we conducted a latent class analysis (LCA)-like approach using Gaussian mixture models (GMM) with diagonal covariance matrices. The best-fitting model was selected according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Agreement between k-means and GMM classifications was quantified using the adjusted Rand index (aRi). We also performed disease-stratified clustering by repeating the k-means procedure (k = 3) separately in PsO-only and PsA subgroups to identify within-disease phenotypes. Finally, we conducted a binary logistic regression (highest CV risk cluster vs. all other clusters) to identify independent predictors of belonging to the “high-risk” phenotype. Continuous predictors were standardized; odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using bootstrap resampling (B = 500).

2.6. Cluster Profiling and Visualization

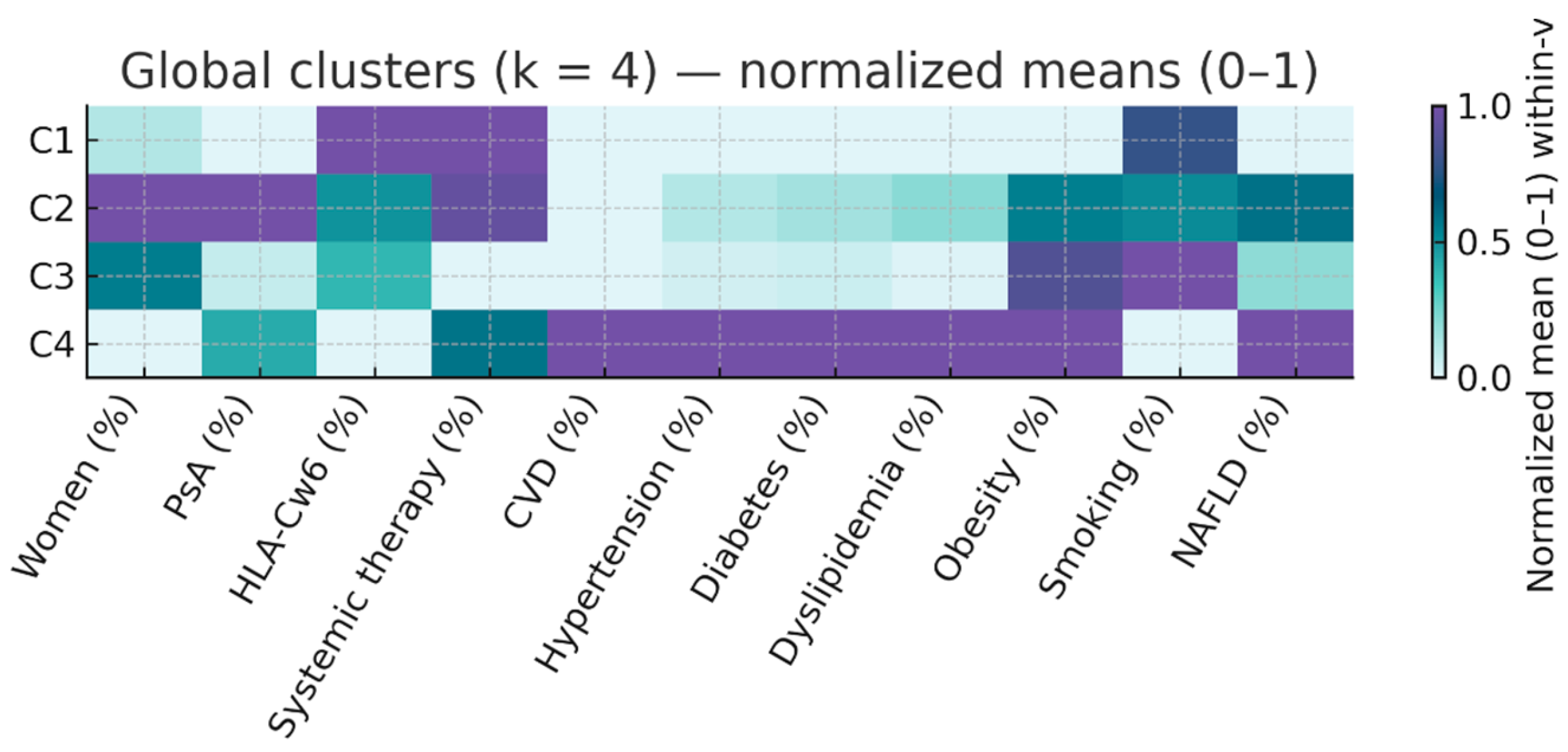

Clusters were described using medians and interquartile ranges [IQR] for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Cardiometabolic risk burden was summarized as the median [IQR] number of risk factors (range 0–6) per patient. We generated heatmaps of normalized (0–1) mean values for each variable across clusters, both for the entire cohort and separately for PsO-only and PsA subgroups, to illustrate relative patterns of clinical and metabolic features. To visualize and summarize the overall structure of the dataset, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using all clinical, genetic, and cardiometabolic variables. The first two components were used to display the relative position of the four clusters. Variables were standardized before PCA, and loadings were inspected to identify the main contributors to each component.

2.7. Software

All analyses were performed in Python 3.10 using pandas, scikit-learn, numpy, and matplotlib libraries.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Study Population

A total of 572 patients with PsD were included, of whom 401 (70.1%) had PsO without arthritis and 171 (29.9%) had PsA. The mean age at assessment was 46.7 (SD 14.5) years, with a median disease duration of 17.0 years [8.0–30.0]. Females represented 46% of the cohort. The average BMI was 27.6 (SD 5.02), while the average waist circumference was 98 cm (min: 61, max: 138). Just over a third (34.3%) of the patients were smokers, while the median alcohol consumption according to standard drink units (SDU) was 0 (min: 0, max: 30). Fatty liver disease was ruled out in 405 (70.8%), confirmed in 129 (22.6%) and no information was available for 38 (6.6%). A total of 20% of the patients had hypertension and another 20% had dyslipidemia. In total, 33 patients had adverse coronary events (5.8%), 22 patients were type I diabetics (3.8%), while 45 (7.9%) were type 2. A total of 241 patients expressed the HLA-Cw6 allele (42.1%). The remaining diseases features as well as sex-based differences are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Unsupervised Clustering (k-Means)

The optimal k-means solution was obtained with four clusters (k = 4), which provided the best compromise between silhouette score (0.22) and clinical interpretability. Main characteristics of the 4 cluster were as follows:

Cluster 1 (C1, n = 217; 37.9%) – “Active PsO, low CV risk”. Psoriasis-only (0% arthritis) with high PASI (median 12.0 [9.0–20.0]), almost universal systemic therapy (99.5%), relatively young (median 45 years), and low prevalence of cardiometabolic factors (HBP 13.8%, DM 7.4%, dyslipidemia 13.4%).

Cluster 2 (C2, n = 144; 25.2%) – “Inflammatory PsA, moderate CV risk”. Exclusively PsA (100%), median PASI 12.0 [8.0–20.0], high systemic therapy use (93.8%), older than C1 (median 49 years), and intermediate cardiometabolic profile (HBP 20.8%, DM 13.2%, dyslipidemia 25.0%).

Cluster 3 (C3, n = 178; 31.1%) – “Mild PsO, high smoking prevalence”. Predominantly PsO (92.7%), lowest PASI (4.0 [3.0–6.0]), no systemic therapy, youngest group (median 43.5 years), and highest smoking prevalence (41.0%), with otherwise low–moderate cardiometabolic burden.

Cluster 4 (C4, n = 33; 5.8%) – “High cardiometabolic risk”. Mixed PsO/PsA (42.4% arthritis), older age (median 66.0 years), longest disease duration (30 years), universal cardiovascular disease (100%), and highest prevalence of all risk factors (HBP 75.8%, DM 45.5%, dyslipidemia 69.7%). Median number of risk factors was 3 [

2,

3,

4].

The resulting phenotypes are summarized in

Table 2 and illustrated in

Figure 1 (normalized heatmap of clinical and metabolic variables).

3.3. Validation with Gaussian Mixture Models (LCA-like)

Model-based clustering using GMM identified a best-fitting solution with k = 4 by BIC, closely paralleling the k-means structure. Agreement between classifications was high (aRi 0.83). The GMM-derived classes reproduced the same spectrum of phenotypes, confirming the robustness of the findings.

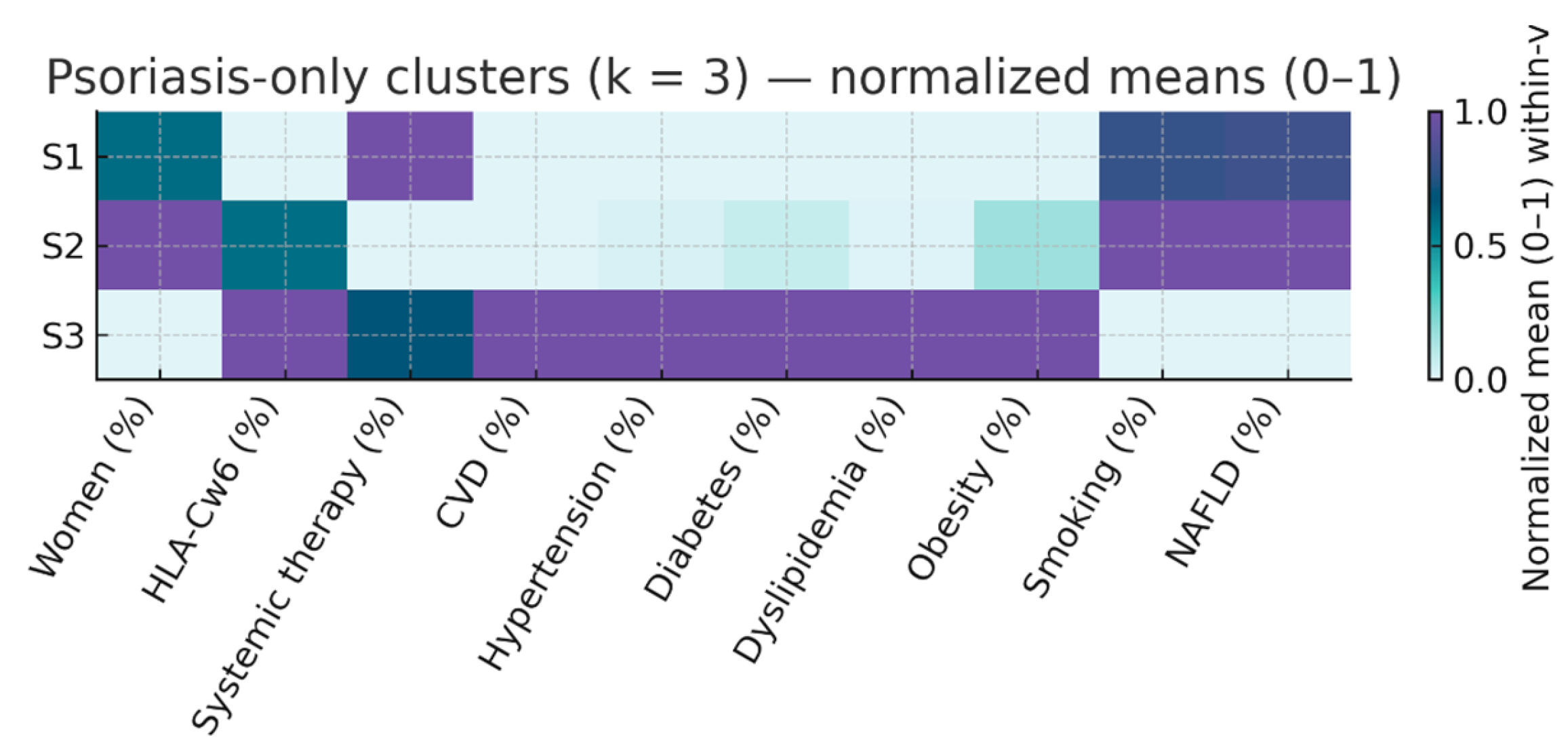

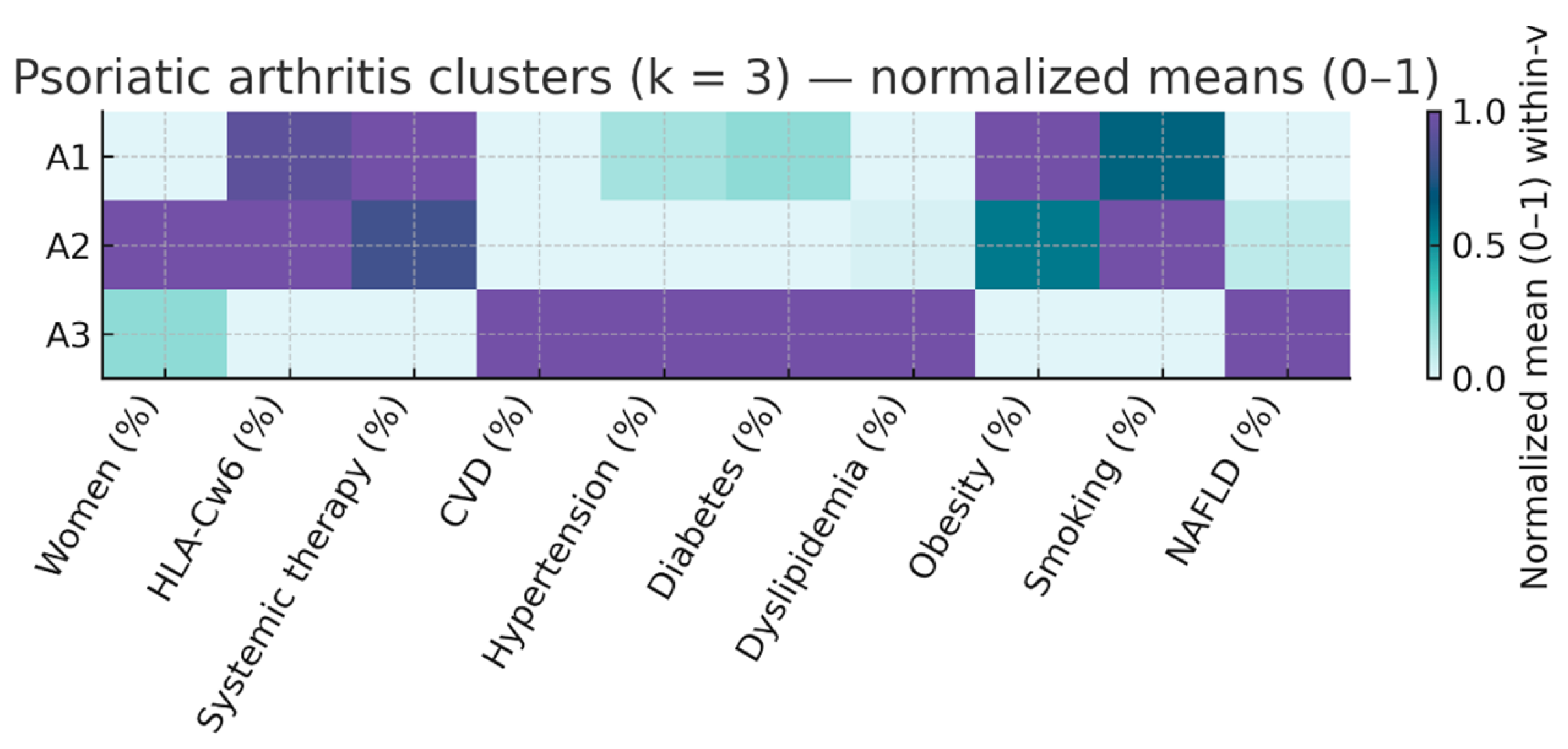

3.4. Disease-Stratified Clustering

We repeated the k-means procedure with k = 3 separately in patients with PsO only and those with PsA to explore within-disease heterogeneity. The results are summarized in

Table 3 and

Table 4 and illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

In PsO three distinct phenotypes emerged:

S1 (n = 217; 54.1% of PsO) – Active PsO, low CV risk. Median PASI 12.0 [9.0–20.0], almost universal systemic therapy (99.5%), median age 45 years, and low prevalence of hypertension (13.8%), diabetes (7.4%), and dyslipidemia (13.4%). Median number of CV risk factors: 1 [0–2]. HLA-Cw6 prevalence 34.6%.

S2 (n = 165; 41.1% of PsO) – Mild PsO, high smoking prevalence. Lowest PASI (4.0 [3.0–6.0]), no systemic therapy, median age 44 years, highest smoking prevalence (40.6%), with otherwise modest metabolic risk (HBP 15.2%, DM 9.7%, dyslipidemia 13.9%). Median CV risk factors: 1 [

1,

2]. HLA-Cw6 prevalence 48.5%.

S3 (n = 19; 4.7% of PsO) – PsO with elevated metabolic risk. Median PASI 8.0 [3.2–13.5], systemic therapy in 68.4%, older age (66 years), and disproportionately high metabolic burden (HBP 68.4%, DM 42.1%, dyslipidemia 68.4%, obesity 47.4%). Median CV risk factors: 2 [

2,

3,

4]. HL A-Cw6 prevalence 57.9%.

In PsA three phenotypes were also identified:

S1 (n = 93; 54.4% of PsA) – Inflammatory PsA, moderate CV profile. Median PASI 12.0 [7.4–20.0], systemic therapy in 89.2%, median age 52 years, and moderate cardiometabolic burden (HBP 25.8%, DM 16.1%, dyslipidemia 23.7%). Median CV risk factors: 1 [

1,

2]. HLA-Cw6 prevalence 46.2%

S2 (n = 64; 37.4% of PsA) – Younger PsA with low CV burden. Median PASI 12.0 [6.1–16.0], systemic therapy in 81.2%, median age 47 years, low prevalence of HBP (15.6%), DM (7.8%), and obesity (21.9%). Median CV risk factors: 1 [0–2]. HLA.Cw6 prevalence 48.4%.

S3 (n = 14; 8.2% of PsA) – Older PsA with high CV risk. Median PASI 4.0 [3.0–15.0], systemic therapy in 42.9%, median age 67 years, universal cardiovascular disease (100%), and highest metabolic burden (HBP 85.7%, DM 50.0%, dyslipidemia 71.4%). Median CV risk factors: 3 [2–3.8]. HLA-Cw6 prevalence 21.4%.

These stratified analyses confirm that heterogeneity in cardiometabolic risk exists within both PsO and PsA, and that high-risk phenotypes are not confined to patients with arthritis.

When the analysis was restricted to patients with PsO, the prevalence of HLA-Cw6 positivity increased progressively across clusters, reaching its highest value in the high-risk phenotype (C3: 57.9%) compared to the combined low/moderate-risk phenotypes (C1–C2: 40.6%). This difference was statistically significant (OR = 2.00, 95% CI 1.29–3.09, p = 0.0026). In contrast, in PsA, the high-risk phenotype (C3) exhibited a markedly lower prevalence of HLA-Cw6 positivity (21.4%) than the lower-risk phenotypes (C1–C2: 47.1%), yielding an inverse and statistically robust association (OR = 0.24, 95% CI 0.11–0.52, p = 0.00029).

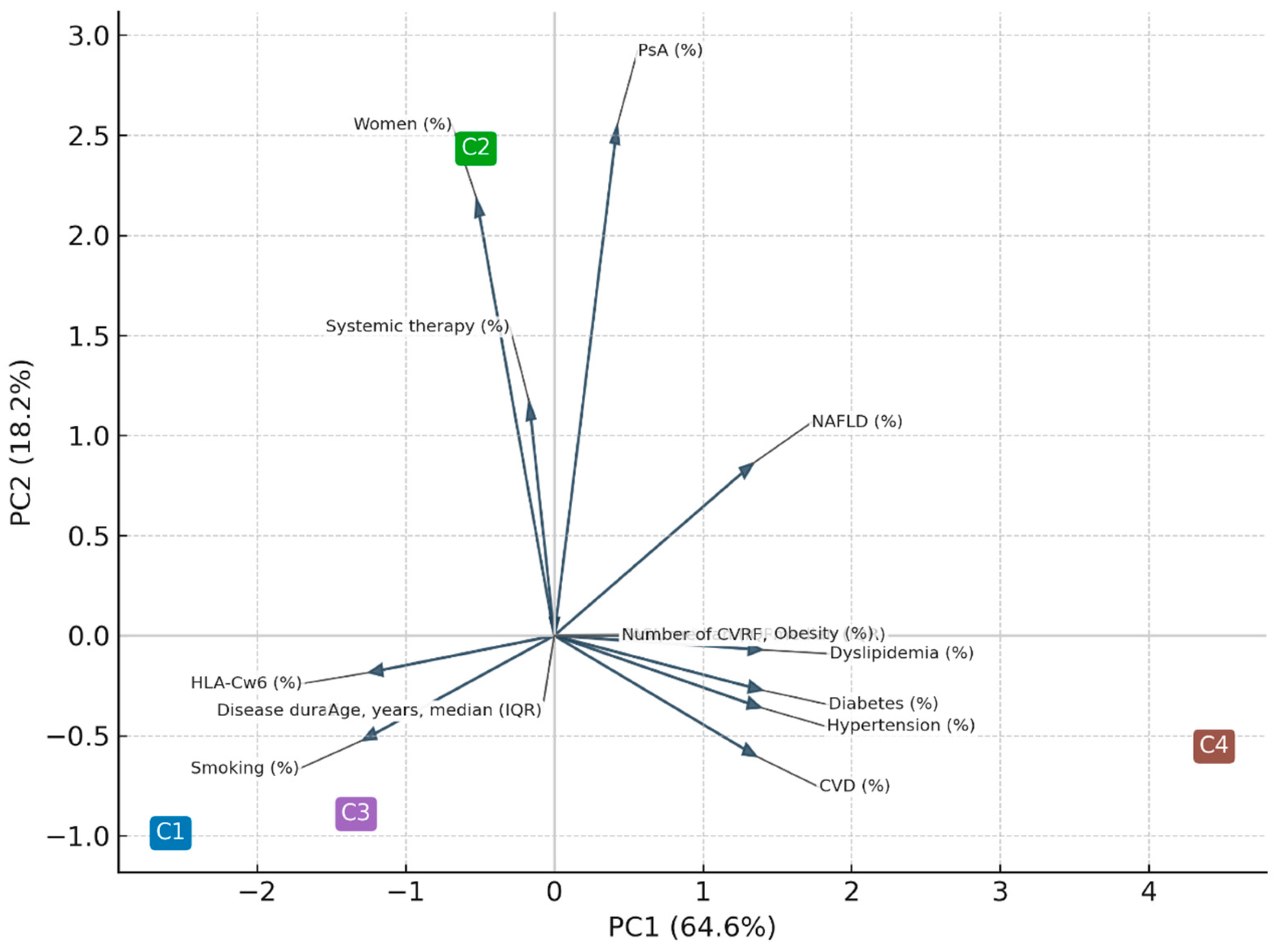

Principal component analysis (PCA) performed on individual-level data accounted for 69% of total variance (PC1 = 47%, PC2 = 22%). For graphical purposes, the PCA displayed in

Figure 4 was computed using the cluster centroids, which explained 83% of between-cluster variance (PC1 = 64.6%, PC2 = 18.2%). Both approaches confirmed a dominant cardiometabolic axis (PC1) and a secondary inflammatory/immunogenetic axis (PC2).

The contribution of each variable to PCA is depicted in

Table 5.

3.5. Predictors of High-Risk Phenotype

Three multivariable logistic regression models were built to identify factors associated with belonging to the high-risk cluster (C4). In the full model including all candidate variables (age, sex, PsA, PASI, HLA-Cw6, systemic therapy, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity), only age and cardiometabolic comorbidities—particularly hypertension and dyslipidemia—remained significantly associated with C4 membership. In a clinically adjusted model restricted to variables with p < 0.10 in univariate analysis, the same pattern was observed, confirming the dominant contribution of age and traditional metabolic risk factors. Finally, a backward stepwise model yielded a parsimonious configuration including age, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which retained comparable explanatory power and discrimination (AUC ≈0.80). Collectively, these results indicate that the high-risk phenotype is largely driven by older age and cumulative cardiometabolic burden, rather than by psoriatic domain or genetic background (HLA-Cw6). Confidence intervals were calculated using bootstrap resampling (B = 500) to ensure robustness of the estimates. Full regression models and test for collinearity diagnostics (VIF) are shown in

supplementary material.

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of 572 patients with PsD, we identified four distinct cardiometabolic phenotypes using unsupervised k-means clustering applied to demographic, clinical, and immunogenetic data, including HLA-Cw6 status. These phenotypes differed markedly in age, disease duration, systemic therapy use, and cardiometabolic burden, as measured by traditional risk factors and CVD disease history. Validation with LCA confirmed the robustness of the classification, and disease-stratified analyses in PsO and PsA further supported the reproducibility of the phenotypes across disease subtypes.

Our findings both relate to and expand upon previous evidence published by our group, where a classical analysis of three cohorts using regression and meta-analysis revealed an inverse association between HLA-Cw6 and diabetes, particularly in patients with psoriasis without arthritis, supporting the existence of an HLA-Cw6-linked cardiometabolic “protective” endotype [

9]. However, that work did not assess within-disease heterogeneity or explore potential differences between psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis beyond multivariable adjustments. By incorporating HLA-Cw6 as a variable in an unsupervised clustering framework, the present study partially confirms that protective pattern in PsA, yet uncovers an opposite trend in PsO, where Cw6 positivity was associated with a high-cardiometabolic-risk phenotype. This observation suggests that the impact of HLA-Cw6 on cardiometabolic risk may be context-dependent, modulated by the predominant clinical domain (cutaneous versus articular) and other factors such as age and disease duration. Therefore, combining classical association analyses with integrative phenotyping techniques provides a more comprehensive view of the complex interplay between genetics, clinical expression, and comorbidity across the psoriatic disease spectrum.

The multivariable models consistently demonstrated that age and cardiometabolic burden, rather than disease-specific or genetic factors, were the main determinants of the high-risk cluster in the whole population. This finding was robust across different model specifications—comprehensive, clinically adjusted, and parsimonious—underscoring the stability of the association between traditional cardiovascular risk factors and the systemic expression of psoriatic disease. The absence of significant effects for PASI, PsA status, or HLA-Cw6 after adjustment suggests that the transition toward a cardiometabolic-dominant phenotype is more closely linked to aging and cumulative metabolic stress than to inflammatory or genetic drivers. These results reinforce the concept that cardiometabolic comorbidity in psoriatic disease is not merely an epiphenomenon but an integral component of disease heterogeneity, with implications for risk stratification and tailored preventive strategies.

That said, the inclusion of HLA-Cw6—a validated immunogenetic marker—in our clustering variables adds a biological dimension to the identified groups. This supports the interpretation of these subgroups as candidate endotypes: data-driven phenotypes potentially underpinned by distinct pathogenic mechanisms. Previous studies have linked HLA-Cw6 to type I psoriasis, characterized by early onset, extensive skin disease, strong family history, and lower prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome compared with Cw6-negative psoriasis [

10,

11,

12]. Our stratified analysis revealed a divergent pattern in the relationship between HLA-Cw6 and cardiometabolic risk across the PsD spectrum. Among patients with PsO only, HLA-Cw6 positivity was associated with the high-risk cardiometabolic cluster, consistent with previous evidence linking Cw6 to more severe cutaneous disease, which may in turn be related to systemic inflammatory load and metabolic dysregulation. Conversely, in PsA, Cw6 positivity was substantially less frequent in the high-risk cluster and more common in the lower-risk phenotypes. This inverse association suggests that Cw6-positive PsA may represent a distinct endotype characterized by predominant cutaneous disease and a comparatively more favorable cardiometabolic profile, whereas Cw6-negative PsA could be enriched for musculoskeletal-dominant phenotypes with greater systemic comorbidity burden. This phenotypic inversion between PsO and PsA underscores the potential role of HLA-Cw6 not only as a marker of cutaneous disease susceptibility but also as a potential stratifier of cardiometabolic risk within the broader PsD spectrum [

13,

14,

15]. The findings align with the growing recognition that genetic markers, when integrated with clinical and metabolic profiles, can refine endotype definitions and guide risk-based management strategies [

13,

14,

15].

The principal component analysis (PCA) provided an integrative visualization of the multidimensional structure underlying psoriatic disease. The first two components accounted for most of the between-cluster variance and reflected two major and biologically meaningful axes: a cardiometabolic dimension (PC1) and an inflammatory/immunogenetic dimension (PC2). Variables such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease loaded strongly on PC1, whereas PsA, female sex, and systemic therapy contributed primarily to PC2. The inverse loading of HLA-Cw6 on PC1 further supports the dissociation between genetic susceptibility and metabolic burden. Together, these findings confirm that cardiometabolic risk factors and inflammatory pathways cluster along partially independent axes yet converge in patients with more severe systemic disease (cluster C4). This pattern highlights the coexistence of metabolic and immune-driven mechanisms in psoriatic disease, consistent with prior multidimensional models linking low-grade inflammation, adiposity, and psoriatic manifestations (13-17).

Methodologically, the classification showed high agreement between k-means and LCA (adjusted Rand index 0.83), supporting reproducibility. The bootstrap procedure in regression analysis ensured stable estimates despite the small size of high-risk clusters. The disease-stratified analyses further confirmed that the high-risk phenotype is not confined to those with arthritis.

Our results have several implications. First, comprehensive CV risk assessment in all PsD – High-risk phenotypes were present in both PsO and PsA, challenging the assumption that arthritis alone drives systemic risk [

16,

17]. Second, potential genetic stratification – Cw6 status could help identify patients more likely to present with lower metabolic burden, particularly in PsA, whereas Cw6-negative status may alert clinicians to higher CV risk. Third, targeted prevention – small, high-risk clusters such as C4, PsO-S3, and PsA-S3 represent priority groups for aggressive CV risk factor control and possibly closer dermatology–rheumatology–cardiology collaboration. Fourth, lifestyle interventions – phenotypes characterized by high smoking prevalence (C3, PsO-S2) highlight modifiable risks that may be overlooked in PsD management [

18]. Fifth, research implications – these clusters provide a framework for studying differences in therapeutic response and long-term outcomes across phenotypes.

Of course we must highlight some drawbacks. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference. While the inclusion of HLA-Cw6 provides a biological anchor, we lacked other biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory cytokines, metabolomics) that could deepen mechanistic understanding. Small sample sizes in some clusters, particularly high-risk groups, may affect generalizability, though bootstrap resampling mitigates instability. Additionally, clustering was based on variables available in clinical practice; adding longitudinal trajectories may refine phenotyping.

Longitudinal studies should test the stability of these phenotypes and their predictive value for CV events, treatment response, and disease progression. Integrating multi-omics data could confirm biological distinctiveness, transitioning from candidate endotypes to validated endotypes. Interventional trials targeting high-risk groups could determine whether phenotype-guided prevention improves outcomes [

19,

20].

5. Conclusions

In this study of 572 patients with psoriatic disease, we identified four distinct cardiometabolic phenotypes using unsupervised clustering. The results were robust to model-based validation and consistent within psoriasis-only and psoriatic arthritis strata. The high-risk phenotype was largely driven by older age and cumulative cardiometabolic burden, while the use of bootstrap resampling provided stable confidence intervals, reinforcing the reliability of these associations despite the small size of this subgroup. Our findings suggest that simple demographic and clinical variables can stratify PsD patients into reproducible cardiometabolic endotypes with distinct preventive and therapeutic needs. Integrating such phenotyping into routine clinical practice could help tailor cardiovascular risk assessment and guide targeted interventions aimed at improving long-term outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (CEImPA-214/2023).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to patient confidentiality and institutional policies, raw individual-level data cannot be made publicly available.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests related to this work.

Author Contributions

RQ is responsible for conceptualization, methodology, supervision, data interpretation, writing – original draft & review/editing. PA, IB, ML, EP, SB, NC, SA, MA: Data acquisition, clinical assessments, manuscript review, draft review. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

STROBE Reporting Statement

This manuscript was prepared and reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines for observational studies (see

supplementary material).

AI Assistance Disclosure

AI tools (ChatGPT, OpenAI) were used only to support language refinement. No AI tools were used for data analysis, interpretation, or generation of scientific content.

References

- Toussirot, E.; Gallais-Sérézal, I.; Aubin, F. The cardiometabolic conditions of psoriatic disease. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 970371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzeni, F.; Rodríguez-Carrio, J.; Alciati, A.; Tropea, A.; Marchesoni, A. Cardiovascular risk in psoriatic arthritis: How can we manage it? Autoimmun Rev. 2025, 24, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, D.P.; Hauge, E.M.; Crowson, C.S.; Kitas, G.D.; Ormseth, S.R.; Karpouzas, G.A. Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk Stratification in the Rheumatic Diseases: An Integrative, Multiparametric Approach. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2023, 49, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiro, R.; Braña, I.; Pardo, E.; et al. Influence of the HLA-Cw6 Allele and IFIH1/MDA5 Gene Variants on the Cardiometabolic Risk Profile of Patients with Psoriatic Disease. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agache, I.; Adcock, I.M.; Baraldi, F.; et al. Personalized therapeutic approaches for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2025, 156, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depascale, R.; Da Mutten, R.; Lindblom, J.; et al. Unsupervised machine learning identifies distinct SLE patient endotypes with differential response to belimumab. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 4650–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelena, X.; Sepriano, A.; Zhao, S.S.; et al. Exploring the unifying concept of spondyloarthritis: a latent class analysis of the REGISPONSER registry. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 3098–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, W.; Gladman, D.; Helliwell, P.; Marchesoni, A.; Mease, P.; Mielants, H.; CASPAR Study Group. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 2665–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiro, R.; González Del Pozo, P.; Alvarez, P.; et al. Searching for a Novel HLA-Cw6-Linked Cardiometabolic Endotype in Psoriatic Disease. Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douroudis, K.; Ramessur, R.; Barbosa, I.A.; et al. Differences in Clinical Features and Comorbid Burden between HLA-C∗06:02 Carrier Groups in >9,000 People with Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2022, 142, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solvin, Å.Ø.; Bjarkø, V.V.; Thomas, L.F.; et al. Body Composition, Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Comorbidities in Psoriasis and the Effect of HLA-C*06:02 Status: The HUNT Study, Norway. Acta Derm Venereol 2023, 103, adv5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macía-Villa, C.; Morell-Hita, J.L.; Revenga-Martínez, M.; Díaz-Miguel Pérez, C. HLA-Cw6 allele and biologic therapy are protective factors against liver fibrosis in psoriatic arthritis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2023, 41, 1179–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, M.T.; Li, Q.; Wasikowski, R.; et al. Shared genetic risk factors and causal association between psoriasis and coronary artery disease. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaserico, S.; Orlando, G.; Messina, F. Psoriasis and Cardiometabolic Diseases: Shared Genetic and Molecular Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiro, R.; Braña, I.; Loredo, M.; Burger, S. HLA-C*06-defined endotype in psoriatic disease: an ever-widening landscape. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caso, F.; Chimenti, M.S.; Navarini, L.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome and psoriatic arthritis: considerations for the clinician. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2020, 16, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, L. Cardiometabolic Comorbidities in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 19, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinnutt, J.M.; Wieczorek, M.; Balanescu, A.; et al. 2021 EULAR recommendations regarding lifestyle behaviours and work participation to prevent progression of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023, 82, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richette, P.; Vis, M.; Ohrndorf, S.; et al. Identification of PsA phenotypes with machine learning analytics using data from two phase III clinical trials of guselkumab in a bio-naive population of patients with PsA. RMD Open. 2023, 9, e002934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pournara, E.; Kormaksson, M.; Nash, P.; et al. Clinically relevant patient clusters identified by machine learning from the clinical development programme of secukinumab in psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open. 2021, 7, e001845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).