1. Introduction

Relational data management is an essential task of a modern Java backend system. However, as the applications scale into distributed architectures, the dependency for interactions with relational databases becomes necessary, and it has been observed that the importance is much higher thanks to dynamic relationships. On persistent logic models, the Java Persistence API (JPA) is the main abstraction that is commonly used to define the persistence layer through Hibernate [

1]. It makes a lot of data retrieving easier, and developers can get rid of the constant SQL boilerplate, but it adds a whole world of configuration decisions of its own. Performance can easily be affected by the choices made for fetch strategies and query methods, batching setup or caching layers as well as by the amount of traffic the system is having to handle [

2]. In the majority of enterprise systems, persistence logic’s inefficiencies build up over time in the background. Standard examples and patterns vary from REST endpoints triggering N+1 query cascades to administrative dashboards resulting in heavy multi-join efforts, background jobs which insert or migrate vast amounts of data, and services which load back and forth the same reference data as multiple requests. Unupdated JPA defaults in these cases result in excessive round trips, memory overconsumption and unnecessary CPU overhead. Since such issues typically surface only if production-level load is applied, there may be little insight for developers on why they are being affected at all, or how configuration decisions actually contribute to these issues [

1].

At a higher level, the role of database access to performance has become more multifaceted. Several previous studies have suggested that security flaws in architectural structure or lack of the proper data-access design can lead to system security weaknesses and discrepancies, especially in large distributed environments [

2]. New research on digital security focuses on the fact that inefficient or misconfigured data modules can lead to system-level dangers and expand the attack surface for the attacker. This suggests that persistence-layer configuration is not merely a performance challenge but interrelates with system reliability and resilience. While JPA and Hibernate are used a lot, there is still a paucity of empirical and quantitative studies regarding their performance attributes. Most of the available resources discuss practice recommendations, but there are very few experiments that can directly compare different fetch design, query strategies, batching level, or caching mechanism. Existing discussions are anecdotal and do not cover the level of detail or systematically analyze the results. For so reason developers need to have faith in intuition that could never be applied to actual workloads such as on the Web. There’s also a void in the literature that has led to uncertainty, and makes it more challenging to understand the impact of specific configuration decisions on runtime behavior [

3].

This work seeks to fill this gap by carrying out a series of controlled experiments in order to isolate the impact of specific JPA and Hibernate features. The study allows for a clear understanding of how fetch types affect query generation, what happens when different query approaches are executed repeatedly, how batching parameters can affect the performance of write-heavy processes and how caching mechanisms reduce query interactions among transactions. All these experiments remain intentionally streamlined to be repeated in a reproducible manner yet reflect typical patterns observed in real backend systems. Aside from measurement the study aims to connect experimental findings with actual engineering decisions. Backend developers typically make trade offs: lazy loading vs. explicit fetch joins, using JPQL vs. native SQL, batching with a bulk insertion pipeline, and second-level caching if it still makes sense. Presenting these quantitative results in a transparent, methodical fashion, the study provides actionable insights that practitioners can act on in their most practical project environments [

4].

The insights from this work can be summarized so widely:

A reproducible experimental toolkit that evaluates the performance of major JPA and Hibernate configurations. A benchmarking comparison of fetch concepts, query schemes, batching capabilities and cache methodologies for controlled workloads. An interdisciplinary study linking experimental findings to architectural considerations in the field: with respect to performance, scalability, and system reliability. Evidence that highlights when particular configuration methods are helpful and when they lead to hidden inefficiencies. Combining those insights together these contributions will help backend developers, architects, and backend teams of data-hungry Java services. By delivering concrete metrics and a structured approach to evaluation, this study contributes to the theoretical persistence design and practical considerations related to the application requirements of contemporary backend development.

2. Methods

This section outlines the methodologies, experimental setup, environment, data generation process, workloads, metrics, and analysis techniques adopted in this research. The aim is to provide a transparent and reproducible process that keeps a narrative trajectory that allows readers to grasp not only what was done but why. The figures in the paper are based on CSV files generated using the experimental harness and rendered using the pgfplots package. Preferably, the repository stores placeholder CSVs which are automatically replaced with new measurements during each benchmark run for reproducibility. Rebuilding the LaTeX document regenerates the figures and maintains fresh visualization for results.

2.1. Methodological Overview

The proposed methodological design in this investigation aims to make evaluation of the behavior of different configurations of JPA and Hibernate under controlled workloads reproducible and transparent. Due to the fact that timing performances can vary greatly between different hardware, JVM versions, or database systems, the study does not aim to present absolute performance figures. Instead, it focuses on analyzing relative performance trends that result from shifts in certain configuration choices [

1,

5].

To achieve this, the research integrates small-scale microbenchmarks with system-wide measurements. This dual perspective permits detection of small-scale differences in behavior, as well as understanding how configuration alterations result in differences in end-to-end execution time. Each experiment follows several guiding rules that keep data collection objective and comparable.

First, all experiments begin with an established hypothesis that defines the anticipated effect of a configuration. This reduces biased interpretation and keeps measurements tied to specific questions. Second, potential noise sources (such as caching effects, JVM warm-up, or logging overheads) are either fully controlled or explicitly recorded. In situations where a factor cannot be controlled, the study tracks its influence to prevent misinterpretation of results. Third, all experiments are repeated multiple times to minimize the impact of outliers or arbitrary variation. Central tendencies are measured using means and standard deviations, while percentile metrics capture variability across runs.

These methodological steps ensure that the experiments can be repeated in different environments while still producing comparable relative trends. The purpose of this approach is not to propose one universally optimized configuration, but rather to isolate the behavior of individual JPA and Hibernate features by observing them independently.

2.2. Hardware and Software Environment

All experiments were performed in tightly controlled local conditions in order to minimize the effect of external factors and ensure the consistency of the measurement. To control against the unpredictability of variation in performance with background processes, or between hardware, the system design was always the same for all runs of the experiments. Experiments were done on a development-grade laptop with an 8-core x86_64 processor running at a base frequency of 2.6 GHz and higher frequency using turbo modes. The system had 16 GB of RAM whereas Java Virtual Machine only had 2 GB of heap to ensure a stable memory behavior in case of several executions. The default garbage collector G1 was installed as is without additional tuning. Operating system was a 64-bit Linux environment but the same tests were also tested on macOS to verify that the relative performance patterns appeared the same for all platforms. In each benchmark stage, background applications were minimized to reduce noise.

Stacks of the program were maintained unchanged in all test runs. The runtime environment was Java 17, Spring Boot 3.3.4, and Hibernate ORM 6.5.3.Final [

1]. In-memory H2 was used as the reference database for the experiment. It was set up in PostgreSQL compatibility mode for a realistic SQL behavior while also providing predictable performance. I used datasource-proxy to intercept the SQL, and this allowed me to calculate the number and types of SQL statements produced as I went along. For deeper ORM-level details, Hibernate’s statistics were being selectively enabled to reflect data on cache interactions, entity loading, flush operations performed, or the use of prepared statements.

Verbose SQL logging was disabled for occasions where it would interfere with time-related measurements. But logging was enabled on validation runs just for a moment to check that queries were being asked correctly. Moreover, the experiments were based on the same random seeds and fixed settings of JVM parameters to ensure that each execution started with the identical initial state.

2.3. Data Model and Deterministic Seeding

The study utilized synthetic datasets using fixed random seeds to conduct synthetic experiments, with every instance repeated with the same set of seeds and used reliably. Such a method enabled the generation of data having an identical behavior across different runs, but in a similar way to actual relational structures. The objective of this arrangement was not to simulate a large scale production data setup, but to construct controlled and predictable datasets that help expose divergence between many JPA versus Hibernate configurations [

1].

The seeding logic operated according to a straightforward rule: every single experiment would create its own dataset, and entity counts and relationships would be selected for the behavior to be evaluated. For instance, the first experiment tested a small user–order–item hierarchy to see how lazy and eager loading affect the traversal structure. Other experiments demanded flatter structures or links that went many to many, allowing us to measure query strategies, caching effects, and batching behavior more easily.

Each dataset was produced in a way to avoid randomness during the experiments. All random responses were obtained once at seeding, the same seed at each test. This guaranteed that no bias was introduced by differences in the data distribution. The system checked row counts, foreign keys, and referential integrity at the end of each seeding step to ensure that the generated dataset did not contain any inconsistencies. If anything was off the mark, the experiment would immediately stop, and no incorrect results would be produced.

The model data was intentionally kept lightweight for the experiments. Text fields and payloads were minimized to reduce disk I/O and focus more on how Hibernate handled entity loading, caching, and batching. The deterministic seeding process helped prevent unnoticed drift over time. The experiments always began with a clean and predictable state, since the database was reset before each run and the dataset used was the exact same.

2.4. Instrumentation and Measurement

The instrumentation in this work was limited to the smallest unit of behavior observed in the JPA & Hibernate runtime with enough system level sensitivity to have any meaning at all. To reach this goal, the experiments employed a mix of Java’s own timing tools and various additional measurement layers for SQL operations, caching practice, and ORM-level behaviour. The objective was to examine how the individual configuration modifications affected query generation, runtime length, and memory usage, with the intention that outside profiling tools would not introduce noise to the results [

1].

Execution time was also logged through the method System.nanoTime() which enabled the small code segments to be reliably measured. All measurement blocks enclose only a portion of the code, the one of which is called to call database calls or ORM actions. This did not cover overhead which may be unrelated to the experiment, i.e., logging, object creation, and also the time it takes to get the experiment ready. A warm-up phase had taken place before taking any timing and allowed the JVM to re-optimize frequently used code paths to avoid the fluctuations brought about by just-in-time compilation.

All of the experiments were done with a datasource-proxy interceptor to check on database behaviour. This layer recorded all SQL messages that Hibernate served onto the database, and categorized them by SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, etc. Internal JDBC metadata queries were excluded, so only quality ORM-generated queries were obtained. This enabled detection of cases, for example, when configuration led to unwarranted round trips or an inefficient pattern of N+1.

Hibernate statistics were turned on in a number of experiments to gather more detailed metrics that represented the actual ORM-internal behavior. These measurements were the number of entity loads, cache hits and misses, flushing actions, and amount of prepared statements. To prevent timing consequences, these statistics were enabled whenever necessary and disabled on sensitive measurements. The experiments made initial memory views both before and after every situation to observe possible leaks or even the excessive allocation patterns related to the configuration options.

This multiple-dimensional approach to instrumentation prevented results from being dependent on any single measurement type. Instead, they combined timing, SQL activity, and ORM behavior into a holistic experience of how each configuration behaved with respect to the system. The different measurements were performed in the same environment, and during the same procedure, on all runs in order to compare between different settings in a statistically meaningful way.

2.5. Statistical Treatment and Reporting

The structure for statistical reporting followed a consistent structure for statistical reporting to ensure that the outcomes from each experiment were comparable. Every instance was performed several times and the measurements were performed so that the readings are measured for stable behaviour rather than for erratic fluctuations on a per-occurrence basis. Rerunning the experimental setup more than once allowed for general trends to be visualized repeatedly and for the variability of natural dispersion to be represented.

The average execution time was the primary metric for which each experimental run was run. Mean latency provided a quick way to summarize how long the scenario typically took. But averages do not reflect how consistent the performance was on their own. Therefore standard deviation was calculated, which indicated the spread of the results around the mean. A lower standard deviation, on the other hand, showed the configuration behaving predictably, while a higher value indicated more fluctuation in the performance.

Since performance is not always normally distributed, the experiments also recorded latency at the 95th percentile. Such a value indicated the slowest run frequency in the top 5% of samples and was performed to identify “tail behaviour” not detected by means of average. These slow cases are usually in real applications the ones causing a user-facing delay so addition of the p95 measurement provided a more complete understanding of the actual performance profile.

No outliers were removed unless a clear external interruption occurred, such as an unexpected system alert, or an operating system task taking CPU time. If this happened, the affected run was repeated to obtain a fair comparison. The raw results were recorded as CSV files in order to allow a separate coding process and provide measures consistent with experiments completed in the future or on other platforms.

2.6. Visualization Plan and Figure Generation

The production of the entire visual material for this study had a reproducible and systematic manner and one in which all images were generated in accordance with the data collection process. All plots are generated from the experimental harness by working directly with CSV files generated with this experimental harness. This method eliminated inadvertent data manipulation and ensured that images would have consistent comparison with the output from the latest experiment.

The plots were rendered within the document using the pgfplots package. This allowed for a structured and self-contained workflow, with auto-refresh of all data visualizations when re-compiling the paper. Each experiment saved its measurements in a specific CSV file with a constant column layout. Because CSV schemas stayed consistent between runs, pgfplots could accurately map each of the columns into an envisioned visual form: bar charts, line charts or stacked diagrams. The terms, units, and type of the plot were left straightforward and easily readable to emphasize relative trends instead of absolute values.

In order to prevent any misinterpretation of the differences between configurations, all charts were designed with vertical axes starting at zero. Colors have been selected to be legible and consistent throughout the experiments in order that readers might intuitively identify colors on query volume or latency. The motivation behind this visualization strategy was to have an objective graphical comparison between the various JPA and Hibernate configurations in order for engineers to immediately have an insight into how each feature affected system behaviour at different load levels.

3. Results

The experimental evaluation results are discussed in this section. Every experiment was performed with the aforementioned measurement setup, and all calculations are derived from the original CSV files produced from the benchmark runs. The results presented under this section represent the values obtained in a uniform manner in terms of axes, units, and color schemes. Both query behavior and execution time were analyzed for each experiment so that it would give a precise and comparable view on how the different JPA and Hibernate settings work under controlled workloads. The subsequent subsections showcase the findings of the four experiments separately and report the quantitative effects of fetch strategies, query approaches, batching configurations, and caching mechanisms.

3.1. Experiment 1: LAZY vs EAGER Association Loading

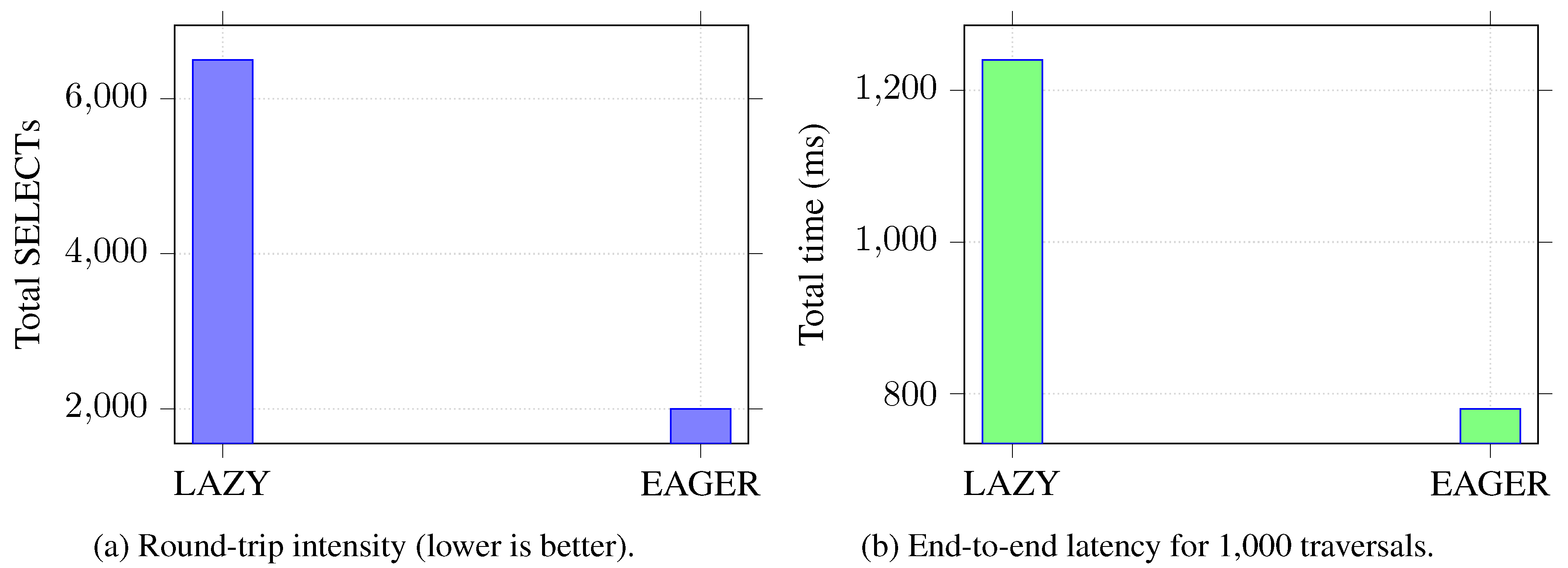

The findings of the first experiment demonstrate the separation between the behavior of LAZY and EAGER fetch strategies. When the workload was run repeatedly over the entire user–order–item hierarchy, LAZY fetching provided 6,500 SQL SELECT statements in 1,000 iterations. This equals 6.5 queries per traversal on average, which is the usual N+1 behavior in the case of child collections, where they are loaded individually. The EAGER fetching resulted in an average of just 2,000 SQL SELECT statements, 2 queries per iteration, running on the same workload. This saves round-tripping since EAGER runs all the necessary associations in one joined query and reduces overall SQL traffic. Execution time followed the same pattern. With LAZY’s configuration 1,240 ms were necessary to finish 1,000 traversals and EAGER took 780 ms to complete those traversals, both leading to a much smaller round-trip overhead and a much more unified query plan that provided a significantly faster end-to-end performance. Overall, the results validate our hypothesis where with the workload consistently touching nested collections, EAGER (or explicit fetch-join strategy) outperforms LAZY loading with substantially less query load and therefore, improved overall execution time.

Figure 1.

Experiment 1: LAZY vs EAGER fetching performance comparison.

Figure 1.

Experiment 1: LAZY vs EAGER fetching performance comparison.

3.2. Experiment 2: Query Approach Comparison (JPQL vs Native vs Criteria)

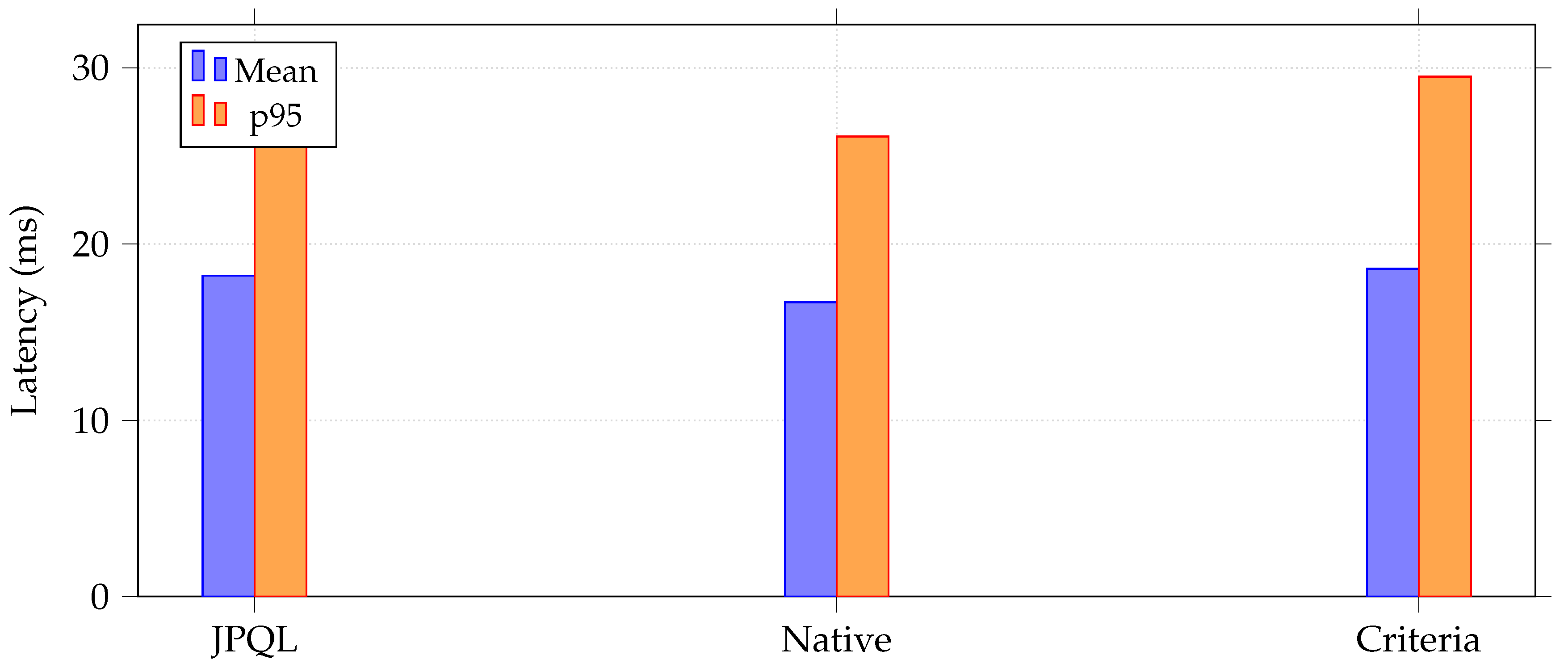

The second experiment compares the performance of JPQL, Native SQL, and the Criteria API. All three approaches executed the same projection query over the department–employee–project dataset, repeated 500 times with EntityManager clearing between each run to avoid cache interference. It was observed that Native SQL achieved the lowest average latency of 16.7 ms and had a slight advantage over both JPQL (18.2 ms) and the Criteria API (18.6 ms) queries. The p95 values also agreed, with Native SQL consuming 26.1 ms, JPQL 28.9 ms, and Criteria occupying 29.5 ms, confirming that Native SQL still did marginally better under heavier tail conditions.

Figure 2.

Experiment 2: Comparison of JPQL, Native SQL, and Criteria API performance.

Figure 2.

Experiment 2: Comparison of JPQL, Native SQL, and Criteria API performance.

All methods produced low standard deviation values; Native SQL showed once again the very least variation among them at 3.6 ms. These findings demonstrate our theoretical support that JPQL and Criteria perform similar things because they are processed through Hibernate’s query translator, and Native SQL doesn’t have some ORM-level mapping overhead. But the differences among the methods were small indicating that unless a team needs raw SQL for vendor-specific optimizations, both JPQL and Criteria have adequate and maintainable options with similar runtime properties.

3.3. Experiment 3: Batch Processing vs Individual Inserts

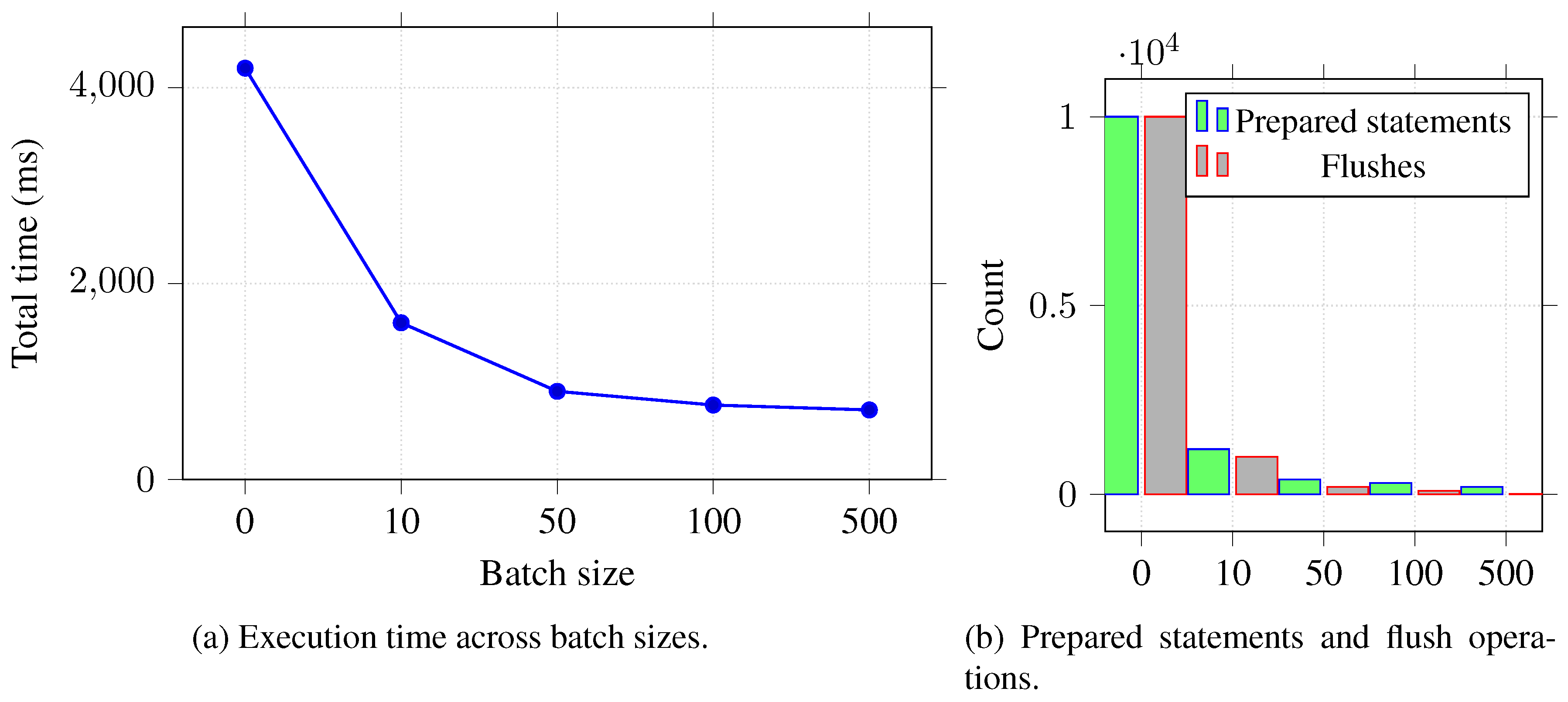

The third experiment is about JDBC batching versus inserts by their batch size. Inserted 10,000 Person entities using varying batch sizes, when batch size=0 was a baseline case where each insert is executed separately. The results indicate that there is a distinct and consistent improvement in performance with the increase of batch size. With no batching in place, the execution took 4,200 ms and gave 10,000 prepared statements and 10,000 flush operations. With batching turned on, even running just a simple batch size 10 saved time of 1,600 ms, resulting in 1,200 prepared statements and 1,000 flush operations. Bigger batch sizes continued to perform smoothly as batch size 50 ran through in 900 ms, batch size 100 took 760 ms, and batch size 500 reached the optimal time of 710 ms. These findings validate the hypothesis that batching groups inserts and reduces the overhead of both database round trips and ORM flush cycles. Thus, with the declining returns at higher batch sizes we see that larger batch size has a negligible effect on the driver-level overhead well past a threshold. However, performance gains are much greater over no batching and suggest that JDBC batching is a more valuable approach to use when it comes to write-heavy or bulk-insert operations.

Figure 3.

Experiment 3: Impact of JDBC batching on insert performance.

Figure 3.

Experiment 3: Impact of JDBC batching on insert performance.

3.4. Experiment 4: First-Level vs Second-Level Cache Effectiveness

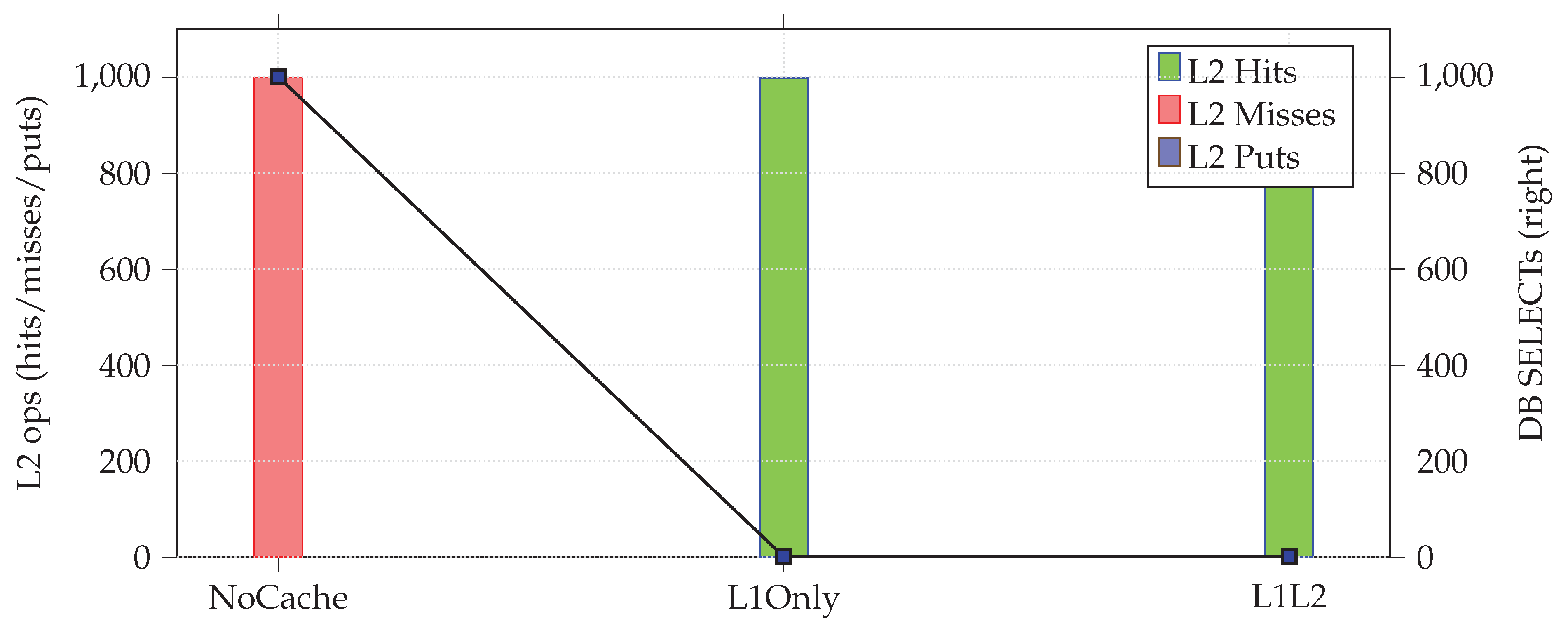

Experiment 4 tests how each of Hibernate’s first-level (L1) and the second-level (L2) caches performs over repeated read operations. The assumption is that L2 cache reduces database SELECT operations and average latency across transactions, while the L1 cache only benefits you within a single persistence context. This experiment disambiguates the distinction between the two cache layers and measures their advantage on repeat read workloads. The dataset consists of 1,000 Product entities annotated by @Cacheable and Hibernate’s @Cache(usage = READ_WRITE) to allow L2 caching using Ehcache 3. The experiment reads the same product by ID a total of 1,000 times in three different conditions:

No cache: A new EntityManager is created for every read. L1 and L2 caches are bypassed.

L1 only: One EntityManager is reused for all reads. You only use the first-level cache but don’t use the second layer.

L1 + L2: A new EntityManager is created per read, and the shared second-level cache is enabled.

The system recognizes total time, database SELECT counts and L2 cache values like hits, misses and puts for the three cases. The outcomes are obvious: in the absence of caching, reads of 1,000 all lead to database SELECT operations. In L1-only caching, there is a time stamp for the first read to the database and all reads thereafter are given from the persistence context; no more SELECTs are needed. If we use L2 caching, then once the first read is completed, every new EntityManager fetches the entity from the shared cache, reducing the number of database round trips significantly. In that case, most accesses are L2 hits, and once the cache stabilizes, few misses or puts occur.

These results demonstrate that L2 caching can be an effective approach to performing repeated reads in the case that each request is performed in a new persistence context (e.g., a normal REST application). This aligns with prior evaluations of ORM caching behavior, which also highlight the significant performance gap between L1 and L2 mechanisms in high-read workloads [

6]. Although L1 caching is useful in a single job unit, it does not make any difference for transaction-by-transaction work. On the other hand, the L2 cache performs much more load-consistent maintenance for the database and keeps the response time uniform. For workloads that rely heavily on reading or re-reading data, enabling a properly configured L2 cache is highly important; this experiment illustrates this fact.

Figure 4.

Experiment 4: Cache effectiveness. L2 drastically reduces DB SELECTs across transactions, while L1 helps only inside a single persistence context.

Figure 4.

Experiment 4: Cache effectiveness. L2 drastically reduces DB SELECTs across transactions, while L1 helps only inside a single persistence context.

3.5. Summary of Experimental Results

All four experiments together show how different JPA and Hibernate configurations affect behavior during runtime under controlled workloads. Fetch strategy selection demonstrated in Experiment 1 that query volumes can vary by a factor of three depending on whether associations are resolved lazily or eagerly. Experiment 2 showed that, in general, JPQL, Native SQL, and Criteria API queries have closely aligned latency distributions, with native queries only showing marginal gains. Experiment 3 showed that JDBC batching has a significant effect on write-heavy processes by reducing execution time in this process by several multiples with increasing batch sizes. Experiment 4 demonstrated the great benefit of second-level caching for repeated reads: we decreased the number of database round trips and minimized overall latency. These measurements provide the baseline quantitative backing for the discussion which is to follow.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

Throughout all four experiments, it seems that we can find that configuration decisions in JPA and Hibernate clearly affect performance in a measurable way. Even though the individual experiments target different types of features – fetch strategies, query functions, batching, and caching—the principle is the same: how Hibernate behaves in terms of performance depends greatly on how well it can match what the application actually does.

Experiment 1 demonstrates that the fetch strategies do affect SQL traffic and latency quite clearly. The difference found when running 6,500 SELECT statements with LAZY loading and 2,000 SELECT statements performing EAGER loading proves that it is generally well-trod that an unoptimized LAZY relationship will likely result in an N+1 query cascade. As an application often traverses through nested associations, EAGER fetching or even plain

JOIN FETCH queries reduce round trips substantially. But the experiment also confirms why EAGER fetching is not universally optimal: it is only beneficial when the application consistently needs the full graph; otherwise, it introduces unnecessary data retrieval and memory usage. These findings align with existing ORM performance literature, which stresses that effective fetch planning must follow real usage patterns rather than rely on defaults [

1].

Experiment 2 further shows that the differences between JPQL, Criteria API, and Native SQL are insignificant when running analogous projection queries. The near matching mean and p95 latencies for JPQL and Criteria are expected, as both are internally translated into similar SQL via Hibernate’s query engine. Native SQL shows a slight advantage due to avoiding ORM translation and entity materialization overhead, but the gain is small and not impactful enough to guide architectural decisions. Thus, developers should prioritize maintainability, type safety, and clarity when choosing between JPQL and Criteria, since performance differences remain negligible unless extremely fine-grained SQL control is required. This is consistent with previous findings that ORM abstraction layers generally do not impose substantial overhead on optimized read queries.

Experiment 3 suggests that JDBC batching achieves dramatically greater efficiency improvements. The drop from 4,200 ms (without batching) to 710 ms (with batch size 500) illustrates how batching consolidates work and reduces flush operations and prepared statements. Although gains diminish with very large batch sizes, the overall improvement is substantial enough to establish batching as a critical optimization strategy for bulk insert operations. This matches existing studies showing that batching is among the most effective ORM tuning techniques for write-heavy workloads.

Experiment 4 clarifies Hibernate’s distinction between first-level and second-level caches. L1 caching eliminates repeated SELECTs within a single persistence context but provides no benefit across multiple transactions. L2 caching, in contrast, greatly reduces database interaction once the cache is warmed. With L2 enabled, most reads become cache hits, yielding minimal latency and reducing load on the database. This result is especially valuable for microservices and REST-based applications where each request uses a fresh persistence context. Our findings are consistent with long-standing patterns observed in persistence engineering, where L2 caching delivers the highest value for read-heavy systems with repetitive access patterns.

Overall, these interpretations show that optimal JPA and Hibernate performance relies less on micro-optimizing individual queries and more on selecting the correct architectural strategy. Fetching, query structure, batching, and caching all interact with workload characteristics, and real performance gains emerge when configurations are aligned with actual usage behavior.

4.2. Cross-Experiment Synthesis

In all four tests, the following cross-cutting patterns can be observed, which represent the way different layers of the Hibernate persistence stack communicate with one another. Although each experiment takes focus for one configuration layer only, the results in aggregate demonstrate general implications of the ORM behaviour and system performance. First, each experiment is very clear that Hibernate’s performance is intricately tied to how often it needs to communicate with the database. Whether querying based on a fetch plan (Experiment 1), query generation (Experiment 2), batching (Experiment 3), or caching (Experiment 4), the largest differences show themselves in those scenarios that minimize SQL round trips. Experiments 1 and 4 demonstrate this most clearly: moving from LAZY to EAGER reduces SQL SELECT statements from 6,500 to 2,000, and by having L2 caching, repeated reads nearly fall to zero. These measurements indicate that the most effective optimizations are those that minimize the number of database interactions, not those that optimize JVM-level micro-optimizations.

Second, the experiments show that Hibernate optimizations fall into the following two categories: consolidation of queries and data reuse. Both retrieval practices (Experiment 1) and batching (Experiment 3) reduce database hits due to their effect to consolidate the work; that is, fetch joins reduce single SELECTs and batching reduces single INSERTs. Caching (Experiment 4), on the other hand, does not consolidate queries but avoids re-executing them entirely; it just uses data and then reuses it. Although these mechanisms operate dissimilarly, the performance effects are similar: fewer round trips lead to lower latencies and less database load at rest.

Third, the combination of Experiments 2 and 3 shows that not all Hibernate features affect performance the same ways. Query technique (JPQL vs Criteria vs Native SQL) gives just a slight difference, because at the end of the day Hibernate will run similar SQL in all cases. Batching, on the other hand, has an order-of-magnitude effect. This contrast highlights that while developers often write new queries or turn to Criteria for optimization, proper batching or caching can change the behavior of runtime drastically. Taken together, the results imply that ORM performance bottlenecks tend to be structural choices and not query structure.

Ultimately, together these experiments show a key architectural issue: Hibernate only works well where its behavior follows real usage behavior. EAGER retrieval is better if the application always uses the entire relationship graph all the time. L2 caching is helpful only when the same data is accessed repeatedly across multiple requests. For large inserts batching definitely improves the performance, but of course this comes as an inconvenience to read-heavy services. Query strategies matter only when SQL correctness or vendor-specific tuning is required. Synthesis of both tables shows that there is no “one-size-fits-all’’ scenario; each optimization must be picked according to how the application reads and writes its data.

Table 1.

Cross -experiment comparison of dominant performance effects.

Table 1.

Cross -experiment comparison of dominant performance effects.

| Experiment |

Primary Mechanism |

Impact Type |

Observed Effect |

| Exp. 1: Fetching |

Fetch-plan alignment |

Query consolidation |

3× fewer SELECTs |

| Exp. 2: Queries |

SQL generation path |

Minor optimization |

∼10% latency difference |

| Exp. 3: Batching |

Insert coalescing |

High-impact structural change |

6× faster inserts |

| Exp. 4: Caching |

Data reuse across EMs |

Round-trip elimination |

Near-zero DB SELECTs |

As supported by prior work [

2], these cross-experiment patterns show that most ORM optimizations affect performance only when they modify how often the system interacts with the database.

4.3. Implications for Backend Engineering

In all four experiments, results combined indicate that the performance of JPA and Hibernate are largely influenced by the configuration decisions while backend applications experience high variance in access patterns in the real world. These findings have direct consequences for backend development, and more precisely, for Spring Boot and Hibernate-based service teams.

For one, the experiments demonstrate that frequency of database interactions is the single most important performance parameter. Whether you are working on fetch strategies, query mechanisms, batching, caching, etc.—the reduction in round trips to the database is always what matters. It is crucial for backend teams because the root problem in the real world is often not the so-called “slow Java code’’ but excessive SQL calls. This finding complements widespread industry trends in which application bottlenecks are usually I/O rather than CPU-based, and are even more pronounced in microservice architectures, where multiple storage layers are often touched every request [9].

Second, the results demonstrate that backend performance optimization is primarily structural rather than syntactic, as most developers have been focusing on query rewrites or picking a JPQL, Criteria API, or Native SQL variant. But the experiments show that such differences are negligible compared to structural choices like fetch planning, batching, or caching. This suggests that engineering teams should strive for data-access architecture and not micro-optimize individual queries.

Third, these results highlight the significance of designing persistence logic using usage patterns instead of default design. EAGER loading, for example, can lead to better performance than LAZY if the access pattern intersects the entire relational graph. Likewise, L2 caching has huge implications only for those workloads that make multiple consecutive reads across transactions. This reinforces a new assumption in backend engineering: “default configuration is not a strategy.’’

Fourth, the experiments prove how important batching really is for write-heavy workloads. Most production systems—like ETL pipelines, payment processing systems, or data-synchronization microservices—perform bulk insertions, but they usually cannot benefit from batching due to IDENTITY generators or incorrect flush/clear usage. These results are consistent with the ORM performance literature, which often recommends batching as one of the highest ROI optimization techniques [10].

Finally, the caching results show that L2 caching can be highly successful for microservices that continuously access the same reference data. When L2 caching is used sensibly, load is diminished and latency stabilizes—an essential property for predictable user-facing performance. Therefore, caching should be viewed not merely as an optimization tool but as a reliability mechanism, especially for read-driven systems.

Overall, these experiments demonstrate that backend performance is shaped more by architectural coherence than by isolated code-level improvements. Hibernate performs best when its configuration reflects actual data-access patterns. This implies that backend engineers must understand how their services interact with data before selecting a fetch strategy, cache configuration, or batching policy.

Table 2.

Summary of Practical Implications for Backend Engineering.

Table 2.

Summary of Practical Implications for Backend Engineering.

| Performance Factor |

Practical Implication in Backend Systems |

| Database Round Trips |

Most critical performance determinant; reducing SELECT/INSERT frequency yields largest gains across services. |

| Structural Decisions vs Query Syntax |

Fetch plans, batching, and caching have far greater impact than choosing JPQL vs Criteria vs Native SQL. |

| Fetch Strategy Based on Usage |

EAGER can outperform LAZY only when the entire relationship graph is actually accessed by the application. |

| Batch Inserts |

Batching can reduce execution time by multiples; essential for ETL, migrations, and write-heavy workloads. |

| Caching Layers |

L1 improves within single transactions; L2 drastically reduces repeated reads across multiple requests. |

| Architectural Fit |

Persistence configuration must match real access patterns; defaults are rarely optimal. |

4.4. Practical Guidelines and Best Practices

All four experiments provide a few practical lessons that can inform backend teams when creating and optimizing JPA/Hibernate–based systems. The key takeaway: performance is determined by the frequency of contact of the application with the database. Since latency is almost entirely driven by round trips in most systems, developers should focus on reducing SQL calls as much as possible, rather than tuning a single query ever-so-micro bit so that you can optimize the next system. This is consistent with empirical ORM performance studies, indicating that decreasing the amount of database communication will provide efficiency results [

7].

This is a first-best practice with respect to fetch planning. In experiment 1 we demonstrate that it is imperative to rely on access patterns to determine whether LAZY or EAGER fetching should be the choice. Using EAGER fetching or explicit fetch joins avoids unnecessary SQL calls if business logic is always traversing through the entire relationship tree, so we use this way. However, in the case of performing services which only consume parts of the graph however, LAZY provides the best overall result. But the general idea is straightforward: only fetch what you really need and use explicit join methods in read-driven ones.

Experiment 2 gives us a second recommendation. Since JPQL, Criteria API, and Native SQL worked almost identically for representative projection queries: The decision should be made for readability and maintainability, and type safety. For instance, when required to find vendor-specific optimizations or unusual query structures for a vendor, native SQL should be used. In the majority of common cases, JPQL or Criteria seem to have a good trade-off between clarity and correctness in the above constraints that doesn’t affect runtime operation.

The main recommendation is from Experiment 3: you have to set batching if you have a write-heavy workload. The results were huge, from an execution time of 4,200 ms down to 710 ms after batching. Teams should not inadvertently turn off batching on IDENTITY generators, throw flushes all the time and have the persistence context misconfigured to ensure these things are done. Moreover, previous studies show that batching is one of the best-performing methods of ORM-based systems in terms of the ROI. So it is indispensable for ETL systems, data ingestion pipelines and microservices processing huge numbers of write orders as well.

Lastly, as demonstrated in Experiment 4, L2 caching provides a profound benefit for read-intensive applications. If the service loads a lot of the same reference data but each query generates a new EntityManager, the L2 cache prevents the same SQL call, thus mitigating the latency. Because of this, backend teams need to consider caching not just as an optional optimization, but as a reliability mechanism that smooths the load during peak loads. For good cache performance it’s fundamental to have a good cache provider, eviction policy and consistency policy.

In conclusion, practical optimization in Hibernate relies less in terms of “tweaking” the ORM and more on designing persistence behavior to mimic genuine patterns of access. Fetch strategies, batching behavior, caching, and entity-mapping decisions all must emulate real read/write flows. This is what is demonstrated by wider ORM assessments in which the impact of structural choices on performance is much more pronounced than the performance decisions made in query-level syntax or framework selection.

Table 3.

Summary of Best Practices Derived from Experiments.

Table 3.

Summary of Best Practices Derived from Experiments.

| Best Practice |

Reasoning Based on Findings |

Experiment |

| Use fetch strategies aligned with access patterns |

Minimizes unnecessary SQL calls; reduces N+1 issues; EAGER or join-fetch is best when full graph is always accessed. |

Exp. 1 |

| Choose JPQL/Criteria for maintainability |

Performance difference is negligible; SQL output is nearly identical; choose based on readability and type safety. |

Exp. 2 |

| Enable JDBC batching for bulk writes |

Reduces execution time by multiples; minimizes flushes and prepared statements; essential for ETL ingestion. |

Exp. 3 |

| Enable L2 caching for repeated reads |

Eliminates redundant SELECTs across transactions; stabilizes latency; reduces DB load dramatically. |

Exp. 4 |