Submitted:

22 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Food, Agricultural, and Agro-Industrial Waste: Volumes and Economic Implications

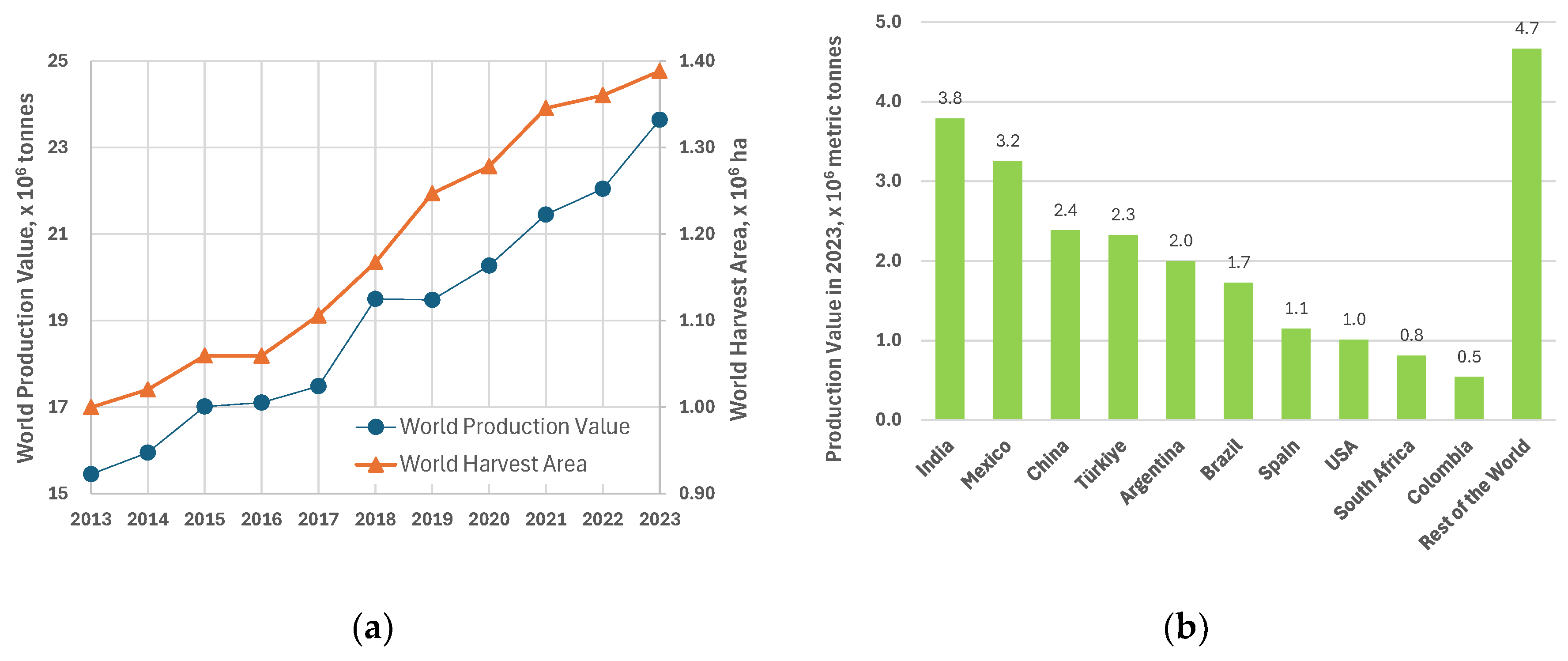

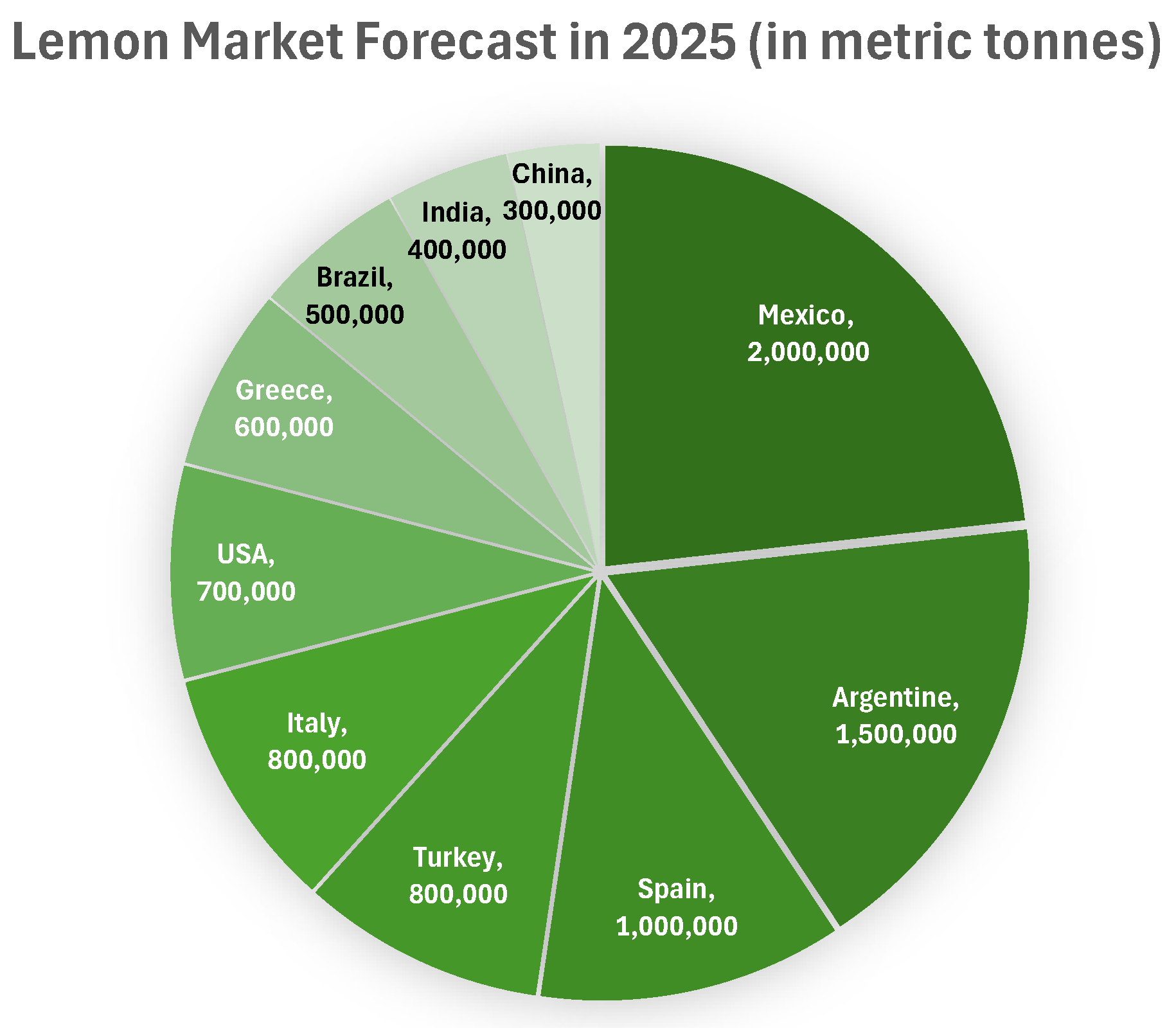

1.2. Global Lemon Production and Waste Generation

1.3. Environmental Challenges and the Circular Economy Concept

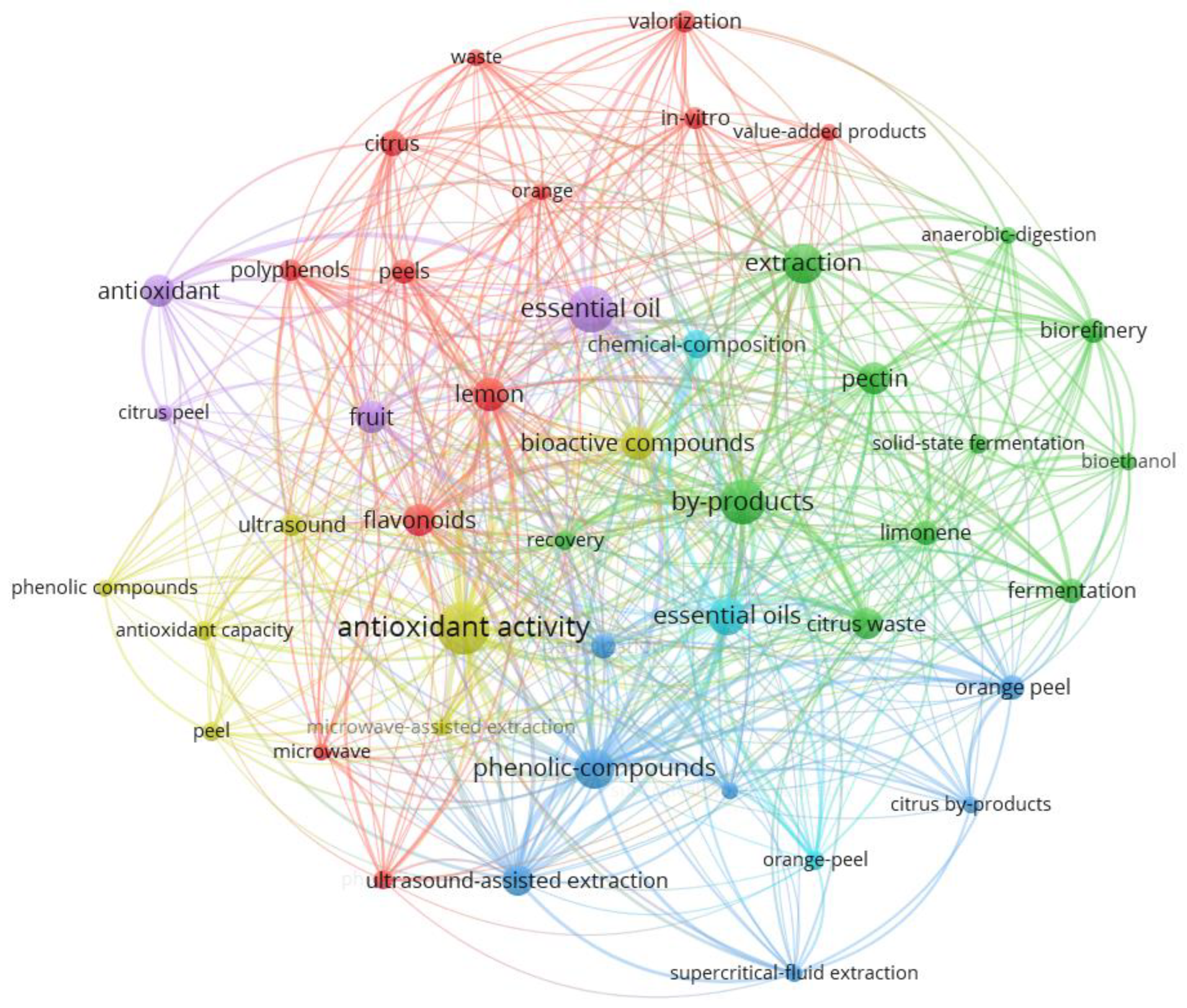

1.4. Bibliometric Analysis of Research Landscape (2003-2025)

1.4.1. Network Structure and Thematic Clusters

1.4.2. Core Research Themes

1.4.3. Emerging Research Frontiers

- Circular Economy Integration: The explicit appearance of terms related to circular economy principles, though not yet forming a large node, indicates growing recognition of system-level thinking beyond single-product valorisation. Recent life cycle assessment (LCA) studies have demonstrated that processing citrus residues in a biorefinery configuration offers superior environmental performance compared to conventional disposal practices, reducing global warming potential by 81-89% [77,78].

- Nanocellulose and Advanced Materials: While “nanocrystalline cellulose” does not appear as a significant node in the current network, related terms suggest nascent interest in advanced cellulosic materials from citrus residues, representing a high-value product frontier. Recent studies have successfully isolated cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) from lemon seeds using sulphuric acid hydrolysis and oxidation methods, achieving yields of 17-19% and producing rod-like morphologies suitable for nanocomposite reinforcement applications [46,79].

- Multi-Product Cascades: The co-occurrence of multiple product terms (pectin, limonene, essential oils, citric acid) within interconnected clusters suggests growing awareness of cascade valorisation concepts, though explicit cascade terminology remains limited in current literature. Integrated approaches for extracting essential oils before pectin recovery have been demonstrated to improve both product quality and overall process economics [71,80].

1.4.4. Publication Trends and Growth Dynamics

1.4.5. Journal Distribution and Disciplinary Scope

1.5. Research Trends and Knowledge Gaps

1.5.1. Identified Research Gaps

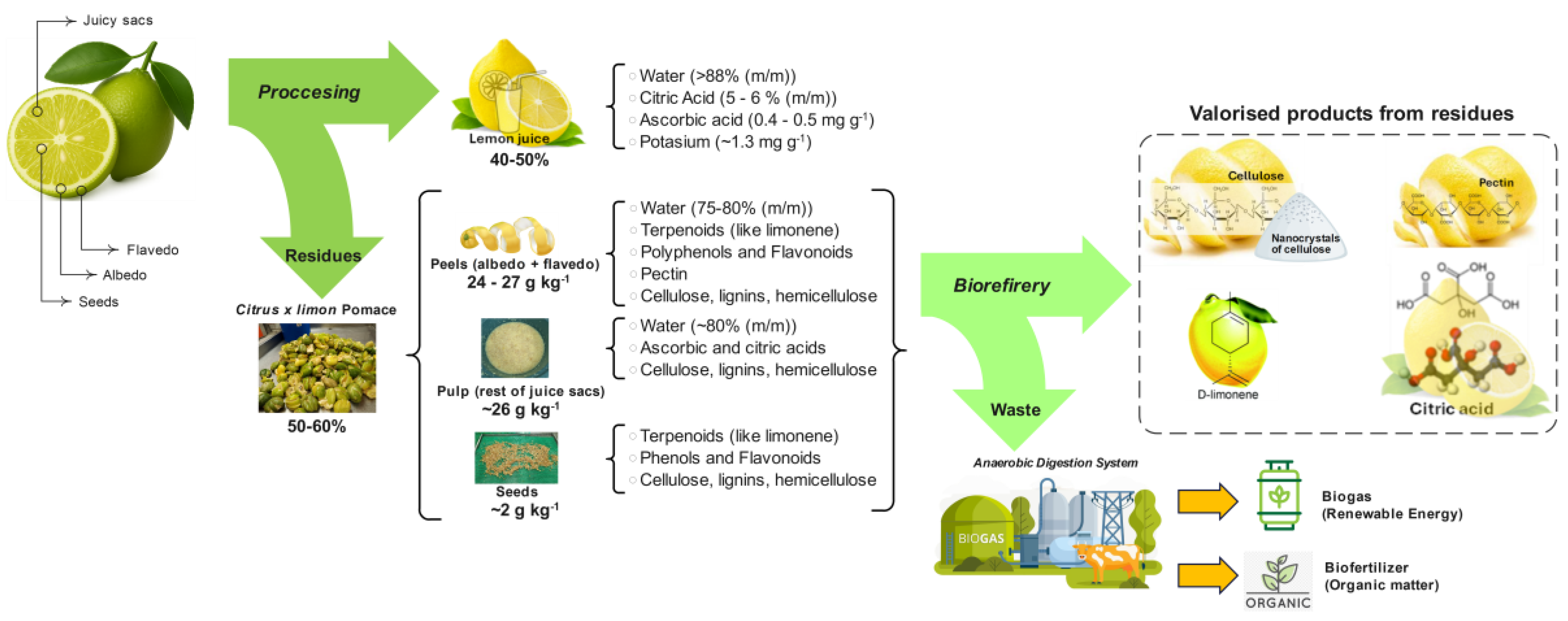

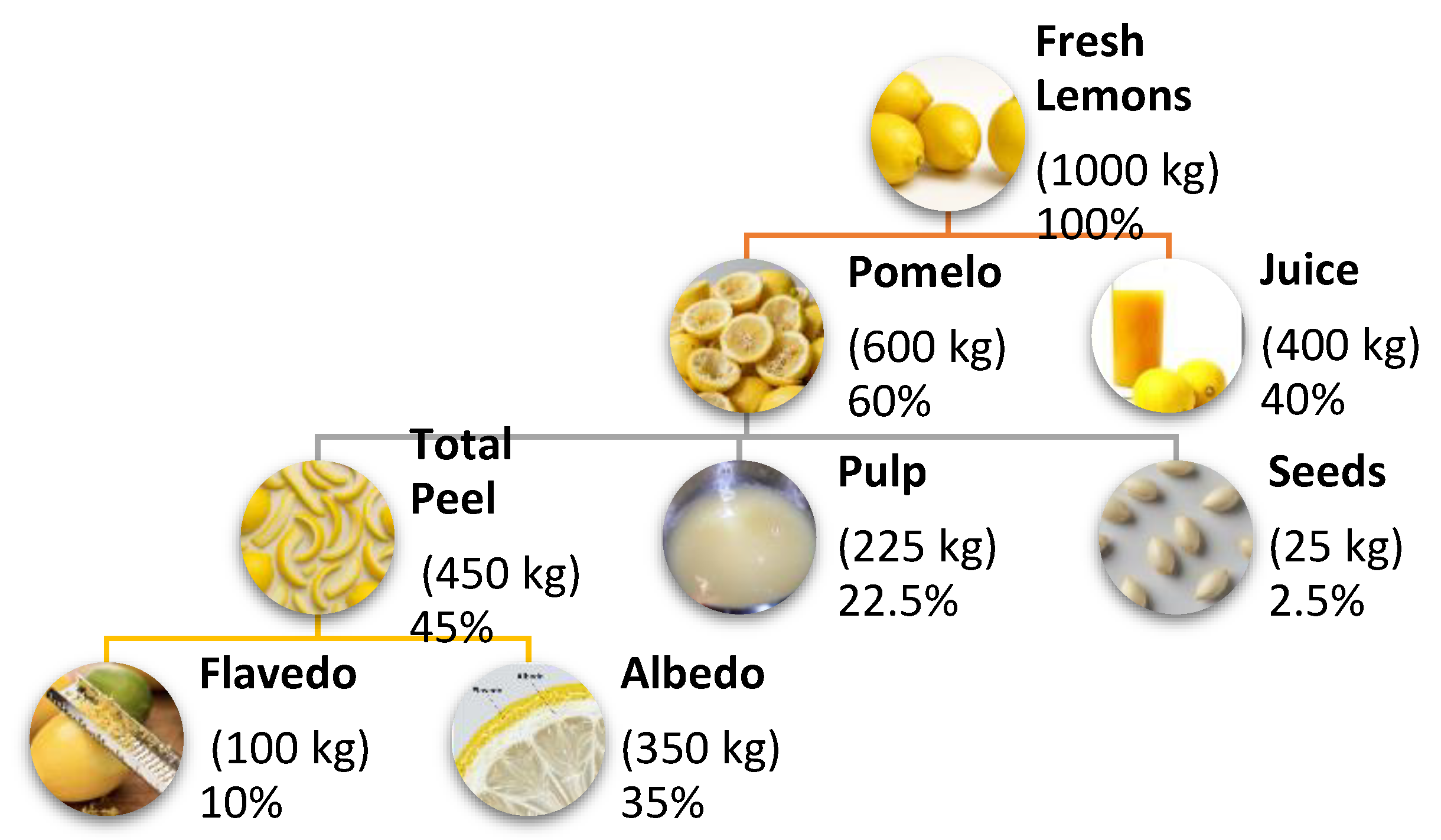

2. Lemon Composition and Residue Characterisation

2.1. Chemical Composition of Lemon Fractions

2.1.1. Flavedo (External Peel)

2.1.2. Albedo (Internal Peel)

2.1.3. Seeds

2.1.4. Pomace (Pulp Residue)

2.2. Quantification of Processing Residues

3. The Hierarchy of Value-Added Products

- Essential Oils and Volatiles: The initial fractionation stage typically involves cold pressing or hydro-distillation to recover essential oils, highly prized by food, flavour, and cosmetic industries. These comprise monoterpenes such as limonene and alpha-terpineol, as well as bioactive sesquiterpenes with antioxidants, antimicrobial, and therapeutic applications [71,136,137].

- Pectin: Next, peels and rag residues undergo acid or enzyme-assisted extraction to yield pectin, a functional polysaccharide used as a gelling agent, stabiliser, and dietary fibre. Cascade valorisation enhances pectin’s techno-economic feasibility by integrating extraction with upstream oil separation and downstream polyphenol recovery [44,138].

- Cellulose and Nanocellulose: Post-pectin extraction, the remaining lemon biomass, which is notably rich in cellulose and hemicellulose, can be processed using green mechanical or chemical pretreatments to obtain microcrystalline cellulose, nanocellulose crystals (NCC), and nanofibrils (NFC). These materials offer exceptional mechanical, rheological, and barrier properties, making them valuable for advanced applications in biopolymer composites, pharmaceuticals, and functional foods [79,83,142].

- Lignocellulosic Biomass Valorisation: Following the removal of limonene, pectin, polyphenols, and cellulose derivatives, the residual solid matrix—composed mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—is well-suited for biotechnological upgrading. Solid-state fermentation (SSF) enables the deployment of specialised fungi (e.g., Trichoderma reesei, Aspergillus niger) and yeasts (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida utilis) to produce industrially relevant enzymes (cellulases, xylanases) and single-cell protein (SCP) for food, feed, or biocatalytic applications [102,143,144].

- Bioenergy, Biochar, and Soil Amendments: The final valorisation step transforms recalcitrant residues (pomace, seeds, effluent solids) through anaerobic digestion [145,146,147], pyrolysis [148,149], and composting [150], providing bioethanol [138,151], biohydrogen [147], and biofertilisers [152] that closes the resource recovery loop.

| Fraction | Major Bioproducts |

Typical Extraction Method | Industrial Application |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential oils | Limonene, alpha-terpineol | Cold press, distillation |

Flavours, cosmetics, therapeutics | [153,154,155,156] |

| Peel, rag | Pectin, polyphenols | Acid/ enzyme extraction |

Food, pharmaceuticals, dietary supplements | [92,120,157] |

| Seeds, pomace |

Proteins, dietary fibres | Solvent/ enzymatic |

Animal feed, functional foods | [158,159,160] |

| Aqueous effluent | Polyphenols, organic acids | Membrane/ adsorption |

Nutraceuticals, food preservatives | [39,161,162] |

| Residues | Bioethanol, biogas, fertilisers | Fermentation, composting | Renewable energy, soil amendments | [71,133,163] |

4. Primary Valorisation Pathways

5. Advanced Valorisation Frontiers

5.1. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidants

5.1.1. Polyphenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity

5.1.2. Advanced Extraction Technologies for Bioactive Recovery

5.1.3. Bioactive Applications and Market Potential

5.2. Industrial Enzymes

5.2.1. Microbial Enzyme Production from Citrus Waste

5.2.2. Enzyme Types and Industrial Applications

5.2.3. Biorefinery Integration and Economic Viability

5.3. α-Cellulose Production

5.3.1. Chemical Composition and Cellulose Content

5.3.2. Extraction Methodologies

5.3.3. Characterisation and Properties

5.3.4. Applications and Market Potential

5.4. Nanocrystalline Cellulose (NCC)

5.4.1. Synthesis Methods and Process Optimisation

5.4.2. Characterisation of Citrus-Derived NCC

5.4.3. Applications and Market Potential

5.4.4. Economic Considerations and Challenges

5.4.5. Integration Within Lemon Cascade Biorefinery

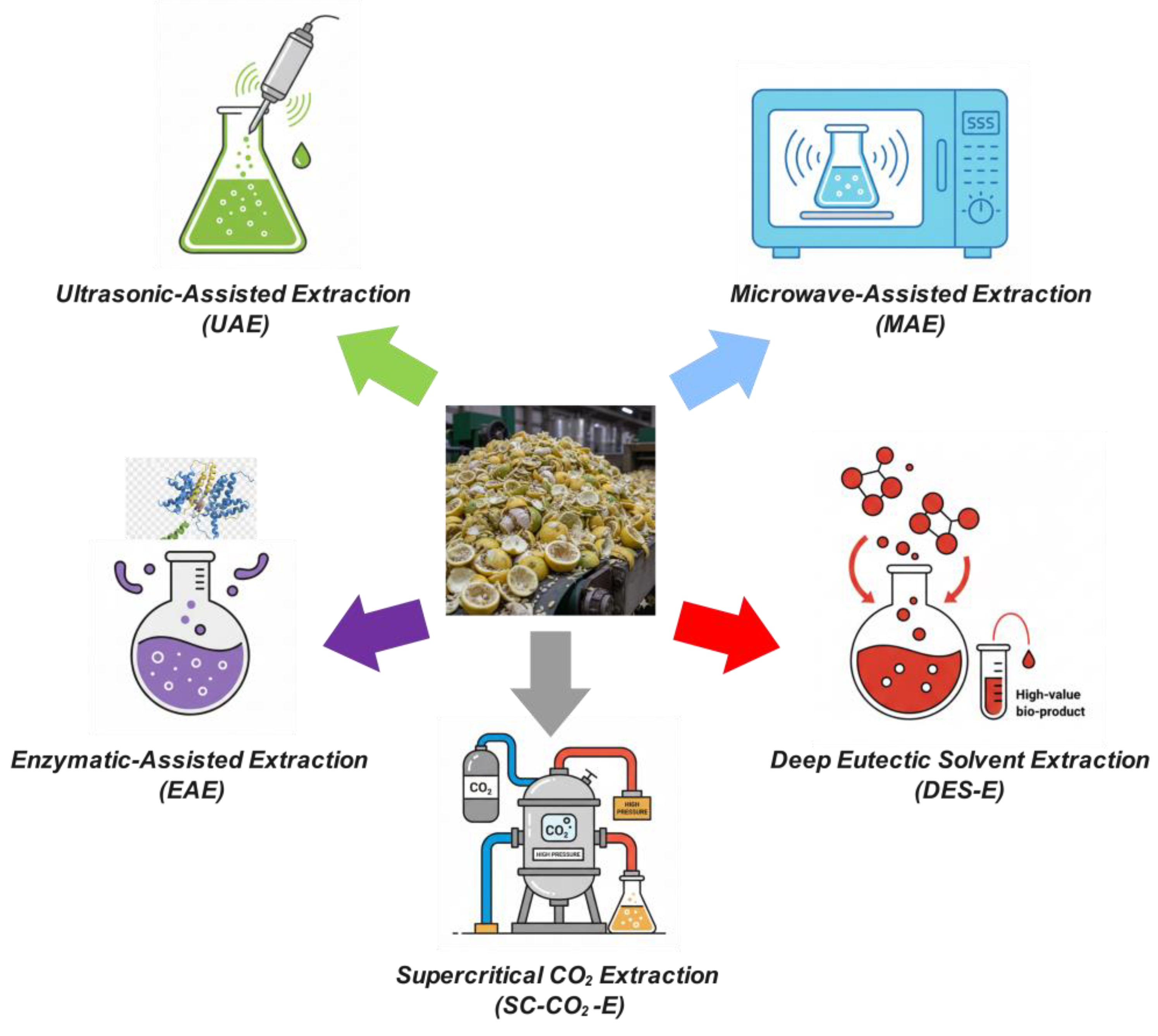

5. Green Extraction Technologies

6.1. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

6.2. Microwave-Assisted Extraction

6.3. Supercritical Fluid Extraction

6.4. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction

6.5. Comparative Assessment Reveals Complementary Strengths Across Green Technologies

6.6. Future Perspectives and Industrial Implementation Pathways

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2’-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| BHA | Butylated Hydroxyanisole BHT Butylated Hydroxytoluene |

| BHT | Butylated Hydroxytoluene |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl Cellulose |

| CNC | Cellulose Nanocrystals |

| CPME | Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether |

| CUPRAC | Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity |

| DES | Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DW | Dry Weight |

| EAE | Enzyme-Assisted Extraction |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| EN | European Norm |

| FESEM | Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GAE | Gallic Acid Equivalents |

| GRAS | Generally Recognised as Safe |

| HM | High Methoxyl |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LM | Low Methoxyl |

| MAE | Microwave-Assisted Extraction |

| MCC | Microcrystalline Cellulose |

| MDA | Malonaldehyde |

| MeTHF | Methyltetrahydrofuran |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| NaDES | NaDES Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| NCC | Nanocrystalline Cellulose |

| NFC | Nanofibrillated Cellulose |

| PEF | Pulsed Electric Field |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| PMF | Polymethoxylated Flavones |

| PVA | Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| SC-CO2 | Supercritical Carbon Dioxide |

| SCP | Single-Cell Protein |

| SSF | Solid-State Fermentation |

| TEA | Techno-Economic Analysis |

| TEMPO | 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| TPC | Total Phenolic Content |

| UAE | Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction |

| UAEE | Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2024 Food Loss and Waste Masterclass: The Basics. Available online: https://www.fao.org/platform-food-loss-waste/flw-events/events/events-detail/2024-food-loss-and-waste-masterclass--the-basics/en (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Florkowski, J.; Bilgic, A.; Meng, T.; Durán-Sandoval, D.; Durán-Romero, G.; Uleri, F. How Much Food Loss and Waste Do Countries with Problems with Food Security Generate? Agriculture 2023, Vol. 13, Page 966 2023, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac-Bamgboye, F.J.; Onyeaka, H.; Isaac-Bamgboye, I.T.; Chukwugozie, D.C.; Afolayan, M. Upcycling Technologies for Food Waste Management: Safety, Limitations, and Current Trends. Green Chem Lett Rev 2025, 18, 2533894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, D.; Kirmani, S.B.R.; Masoodi, F.A. Circular Economy in the Food Systems: A Review. Environmental Quality Management 2025, 34, e70096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, B.; Yakoob, M.; Shah, M.P. Agricultural Waste Management Strategies for Environmental Sustainability. Environ Res 2022, 206, 112285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Environment Programme Food Waste Index Report 2024 | UNEP - UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/food-waste-index-report-2024 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- ReFED Food Waste Data—Causes & Impacts. Available online: https://refed.org/food-waste/the-problem/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- El-Ramady, H.; Brevik, E.C.; Bayoumi, Y.; Shalaby, T.A.; El-Mahrouk, M.E.; Taha, N.; Elbasiouny, H.; Elbehiry, F.; Amer, M.; Abdalla, N.; et al. An Overview of Agro-Waste Management in Light of the Water-Energy-Waste Nexus. Sustainability 2022, Vol. 14, Page 15717 2022, 14, 15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanoglu, E.; Nemli, E.; Tomas-Barberan, F. Novel Approaches in the Valorization of Agricultural Wastes and Their Applications. J Agric Food Chem 2022, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Bioenergy Food Loss and Waste Quantification, Impacts and Potential for Sustainable Management. Available online: https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Task36_-Food-Waste-Report-Final.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Roy, P.; Mohanty, A.K.; Dick, P.; Misra, M. A Review on the Challenges and Choices for Food Waste Valorization: Environmental and Economic Impacts. ACS Environmental Au 2023, 3, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, Q.; Irfan, M.; Tabssum, F.; Iqbal Qazi, J. Potato Peels: A Potential Food Waste for Amylase Production. J Food Process Eng 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raigond, P.; Raigond, B.; Kochhar, T.; Sood, A.; Singh, B. Conversion of Potato Starch and Peel Waste to High Value Nanocrystals. Potato Res 2018, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, A.; Hasani, M.; Nateghi, L.; Asadollahzadeh, M.J.; Kashani, P. Optimization of the Conditions of Process of Production of Pectin Extracted from the Waste of Potato Peel. Iranian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xie, Q.; Guo, L.; Alfano, V.; Toplicean, I.-M.; Datcu, A.-D. An Overview on Bioeconomy in Agricultural Sector, Biomass Production, Recycling Methods, and Circular Economy Considerations. Agriculture 2024, Vol. 14, Page 1143 2024, 14, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, H.Y.; Chang, C.K.; Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W.; Chia, S.R.; Lim, J.W.; Chang, J.S.; Show, P.L. Waste Biorefinery towards a Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy: A Solution to Global Issues. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2021 14:1 2021, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Economou, F.; Chatziparaskeva, G.; Papamichael, I.; Loizia, P.; Voukkali, I.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Klontza, E.; Lekkas, D.F.; Naddeo, V.; Zorpas, A.A. The Concept of Food Waste and Food Loss Prevention and Measuring Tools. Waste Management and Research 2024, 42, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2025). FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Esturo, A.; Lizundia, E.; Sáez de Cámara, E. Transforming Dried Lemon Peel Waste into Value: A Key Step Toward Full Circularity in the Lemon Juice Industry. Journal of Environmental Science, Sustainability, and Green Innovation 2025, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WORLDOSTATS Top Lemon & Lime Producing Countries – Global Data (2025). Available online: https://worldostats.com/country-stats/lemons-limes-production-by-country/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Ess Team Global Lemon Industry Report 2025: Market Trends & Forecasts. EssFeed, 17 October 2025. Available online: https://essfeed.com/global-lemon-industry-report-2025-market-trends-forecasts/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Hausch, B.J.; Lorjaroenphon, Y.; Cadwallader, K.R. Flavor Chemistry of Lemon-Lime Carbonated Beverages. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmiya Begum, S.L.; Premakumar, K. Storage Stability of Functional Beverage Prepared from Bitter Gourd, Lemon and Amla for Diabetes. Asian Journal of Dairy and Food Research 2021, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, H. 6 Evidence-Based Health Benefits of Lemons. Healthline 2019.

- Medicinal and Health Benefits of Lemon. Journal of Science and Technology 2020. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Yarla, N.S.; Siddiqi, N.J.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Sharma, B. Features, Pharmacological Chemistry, Molecular Mechanism and Health Benefits of Lemon. Med Chem (Los Angeles) 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek-szczykutowicz, M.; Szopa, A.; Ekiert, H. Citrus Limon (Lemon) Phenomenon—a Review of the Chemistry, Pharmacological Properties, Applications in the Modern Pharmaceutical, Food, and Cosmetics Industries, and Biotechnological Studies. Plants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon-Mite, A.I.; Mora-Loor, J.L.; Cabrera-Casillas, D.O.; Garcia-Larreta, F.S. Estudio Comparativo de la Composición Química, Fenoles Totales y Actividad Antioxidante de Citrus síntesis, Citrus reticulata y Citrus máxima. RECIAMUC 2022, 6, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, D.; Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Teixeira, P.; Pintado, M. Functional Ingredients and Additives from Lemon By-Products and Their Applications in Food Preservation: A Review. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyasakthi, M.; Sarayu, Y.C.L.; Shanmugam, D.K.; Karthigadevi, G.; Subbaiya, R.; Karmegam, N.; Kaaviya, J.J.; Chung, W.J.; Chang, S.W.; Ravindran, B.; et al. A Review on Innovative Biotechnological Approaches for the Upcycling of Citrus Fruit Waste to Obtain Value-Added Bioproducts. Food Technol Biotechnol 2025, 63, 238–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, D.; Banerjee, S.; Karmakar, S.; Banerjee, R. Valorization of Citrus Lemon Wastes through Biorefinery Approach: An Industrial Symbiosis. Bioresour Technol Rep 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, S.; Singh, A.; Nema, P.K. Current Applications of Citrus Fruit Processing Waste: A Scientific Outlook. Applied Food Research 2022, 2, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Deka, S.C.; Koidis, A.; Hulle, N.R.S. Standardization of Extraction of Pectin from Assam Lemon (Citrus Limon Burm f.) Peels Using Novel Technologies and Quality Characterization. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aina, V.O.; Barau, M.M.; Mamman, O.A.; Zakari, A.; Haruna, H.; Hauwa Umar, M.S.; Abba, Y.B. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Peels of Lemon (Citrus Limon), Grape Fruit (Citrus Paradisi) and Sweet Orange (Citrus Sinensis). British Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2012, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, B.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G.; González-García, S. Identification of Environmental Aspects of Citrus Waste Valorization into D-Limonene from a Biorefinery Approach. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.L.B.; Sousa, W.C.; Batista, H.R.F.; Alves, C.C.F.; Souchie, E.L.; Silva, F.G.; Pereira, P.S.; Sperandio, E.M.; Cazal, C.M.; Forim, M.R.; et al. Chemical Composition and in Vitro Inhibitory Effects of Essential Oils from Fruit Peel of Three Citrus Species and Limonene on Mycelial Growth of Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2020, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, M.D.; Sanchez-Ballester, N.M.; Blázquez, M.A. Encapsulated Limonene: A Pleasant Lemon-like Aroma with Promising Application in the Agri-Food Industry. A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, C.; Laudicina, V.A.; Badalucco, L.; Galati, A.; Palazzolo, E.; Torregrossa, M.; Viviani, G.; Corsino, S.F. Challenges and Opportunities for Citrus Wastewater Management and Valorisation: A Review. J Environ Manage 2022, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Maugeri, A.; Lombardo, G.E.; Musumeci, L.; Barreca, D.; Rapisarda, A.; Cirmi, S.; Navarra, M. The Second Life of Citrus Fruit Waste: A Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds†. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GAIA Municipal Strategies for Organic Waste: A Toolkit to Cut Methane Emissions. Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA).; Berkeley, 2025.

- Lee, S.-H.; Park, S.H.; Park, H. Assessing the Feasibility of Biorefineries for a Sustainable Citrus Waste Management in Korea. Molecules 2024, 29(7), 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, M.A.; Barbosa, C.H.; Shah, M.A.; Ahmad, N.; Vilarinho, F.; Khwaldia, K.; Sanches-Silva, A.; Ramos, F. Citrus By-Products: Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds for Food Applications. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, S.; Narendrakumar, G.; Sundari, N.; Amarnath, M.; Thayyil, P.J. Extraction of Pectin from Used Citrus Limon and Optimization of Process Parameters Using Response Surface Methodology. Res J Pharm Technol 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Petretto, G.L.; Maldini, M.; Tirillini, B.; Chessa, M.; Pintore, G.; Sarais, G. Chemical Characterization, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activity of Hydroalcoholic Extract from the Albedo and Flavedo of Citrus Limon Var. Pompia Camarda. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Yu, Y.; Dai, H.; Zhang, Y. Extraction and Comparison of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Lemon (Citrus Limon) Seeds Using Sulfuric Acid Hydrolysis and Oxidation Methods. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabater, C.; Villamiel, M.; Montilla, A. Integral Use of Pectin-Rich by-Products in a Biorefinery Context: A Holistic Approach. Food Hydrocoll 2022, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlZahabi, S.; Mamdouh, W. Valorization of Citrus Processing Waste into High-Performance Bionanomaterials: Green Synthesis, Biomedicine, and Environmental Remediation. RSC Adv 2025, 15, 36534–36595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, P.; Jhalegar, J.; Hiremath, V.; Shinde, L.; Pattepur, S.; Haveri, N.; Vishweshwar, S. Recent Strategies for Citrus Fruits Valorization: A Comprehensive Overview of Innovative Approaches and Application. Plant Arch 2025, 25, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez, G.; Amador-Luna, V.M.; Castro-Puyana, M.; Ibañez, E.; Marina, M.L. Sustainable Strategies to Obtain Bioactive Compounds from Citrus Peels by Supercritical Fluid Extraction, Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction, and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Food Research International 2025, 202, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, D.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K. Green Extraction of Pectin from Citrus Limetta Peels Using Organic Acid and Its Characterization. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Benohoud, M.; Galani Yamdeu, J.H.; Gong, Y.Y.; Orfila, C. Green Extraction of Polyphenols from Citrus Peel By-Products and Their Antifungal Activity against Aspergillus Flavus. Food Chem X 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, G.; Marcellino, V.; Wardana, A.A.; Wigati, L.P.; Liza, C.; Wulandari, R.; Setiarto, R.H.B.; Tanaka, F.; Tanaka, F.; Ramadhan, W. Biofunctional Features of Pickering Emulsified Film from Citrus Peel Pectin/Limonene Oil/Nanocrystalline Cellulose. Int J Food Sci Technol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, D.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Pectin from Citrus Limetta Peels: Optimization, Characterization, and Its Comparison with Commercial Pectin. Food Biosci 2023, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrea, M.; Cocan, I.; Jianu, C.; Alexa, E.; Berbecea, A.; Poiana, M.-A.; Silivasan, M. Valorization of Citrus Peel Byproducts: A Sustainable Approach to Nutrient-Rich Jam Production. Foods 2025, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, F.; Maurizzi, E.; Haghighi, H.; Siesler, H.W.; Licciardello, F.; Pulvirenti, A. Waste Orange Peels as a Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals and Their Use for the Development of Nanocomposite Films. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.H.; Huang, C.Y.; Shieh, C.J.; Wang, H.M.D.; Tseng, C.Y. Hydrolysis of Orange Peel with Cellulase and Pectinase to Produce Bacterial Cellulose Using Gluconacetobacter Xylinus. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Singh, V.; Vern, P.; Panesar, P.S. From Citrus Waste to Value-Added Products: Exploring Biochemical Routes for Sustainable Valorization. Process Biochemistry 2025, 158, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Muñoz, L.L.; Castañeda-Aude, J.E.; Landin-Sandoval, V.J.; Lozano-Alvarex, J.A.; Escarcega-Gonzalez, C.E. Valorization and Harnessing Citrus Waste: Focus on Green Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles with Antimicrobial Applications and Other Potential Uses. Food Reviews International 2025, 41, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.S.K.; Pfaltzgraff, L.A.; Herrero-Davila, L.; Mubofu, E.B.; Abderrahim, S.; Clark, J.H.; Koutinas, A.A.; Kopsahelis, N.; Stamatelatou, K.; Dickson, F.; et al. Food Waste as a Valuable Resource for the Production of Chemicals, Materials and Fuels. Current Situation and Global Perspective. Energy Environ Sci 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sinha, M.; Sharma, K.; Koteswararao, R.; Cho, M.H. Modern Extraction and Purification Techniques for Obtaining High Purity Food-Grade Bioactive Compounds and Value-Added Co-Products from Citrus Wastes. Foods 2019, 8, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. A Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization of E-Learning Adoption Using VOSviewer. Univers Access Inf Soc 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, H. Paradigms, Citations, and Maps of Science: A Personal History. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 2003, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Mandalari, G.; Calderaro, A.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Felice, M.R.; Gattuso, G. Citrus Flavones: An Update on Sources, Biological Functions, and Health Promoting Properties. Plants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, S.; Singh, A.; Nema, P.K. Recent Advances in Valorization of Citrus Fruits Processing Waste: A Way Forward towards Environmental Sustainability. Food Sci Biotechnol 2021, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rivera, J.; Spepi, A.; Ferrari, C.; Duce, C.; Longo, I.; Falconieri, D.; Piras, A.; Tiné, M.R. Novel Configurations for a Citrus Waste Based Biorefinery: From Solventless to Simultaneous Ultrasound and Microwave Assisted Extraction. Green Chemistry 2016, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmakani, M.-T.; Moayyedi, M. Comparison of Microwave-Assisted Hydrodistillation and Solvent-Less Microwave Extraction of Essential Oil from Dry and Fresh Citruslimon (Eureka Variety) Peel. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2016, 28, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, Y.R. Converting Citrus Wastes into Value-Added Products: Economic and Environmently Friendly Approaches. Nutrition 2017, 34, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S. Trends in Processing Technologies for Dried Aquatic Products. Drying Technology 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsalou, M.; Chrysargyris, A.; Tzortzakis, N.; Koutinas, M. A Biorefinery for Conversion of Citrus Peel Waste into Essential Oils, Pectin, Fertilizer and Succinic Acid via Different Fermentation Strategies. Waste Management 2020, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Fidalgo, A.; Delisi, R.; Ilharco, L.M.; Pagliaro, M. Pectin Production and Global Market. Agro Food Ind Hi Tech 2016, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Boluda-Aguilar, M.; López-Gómez, A. Production of Bioethanol by Fermentation of Lemon (Citrus Limon L.) Peel Wastes Pretreated with Steam Explosion. Ind Crops Prod 2013, 41, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, P.S.; Pontoni, L.; Porqueddu, I.; Greco, R.; Pirozzi, F.; Malpei, F. Effect of the Concentration of Essential Oil on Orange Peel Waste Biomethanization: Preliminary Batch Results. Waste Management 2016, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strazzera, G.; Battista, F.; Garcia, N.H.; Frison, N.; Bolzonella, D. Volatile Fatty Acids Production from Food Wastes for Biorefinery Platforms: A Review. J Environ Manage 2018, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satari, B.; Karimi, K. Citrus Processing Wastes: Environmental Impacts, Recent Advances, and Future Perspectives in Total Valorization. Resour Conserv Recycl 2018, 129, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midolo, G.; Cutuli, G.; Porto, S.M.; Ottolina, G.; Paini, J.; Valenti, F. LCA Analysis for Assessing Environmenstal Sustainability of New Biobased Chemicals by Valorising Citrus Waste. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joglekar, S.N.; Kharkar, R.A.; Mandavgane, S.A.; Kulkarni, B.D. Sustainability Assessment of Brick Work for Low-Cost Housing: A Comparison between Waste Based Bricks and Burnt Clay Bricks. Sustain Cities Soc 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Petri, G.L.; Angellotti, G.; Fontananova, E.; Luque, R.; Pagliaro, M. Nanocellulose and Microcrystalline Cellulose from Citrus Processing Waste: A Review. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 281, 135865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidalgo, A.; Ciriminna, R.; Carnaroglio, D.; Tamburino, A.; Cravotto, G.; Grillo, G.; Ilharco, L.M.; Pagliaro, M. Eco-Friendly Extraction of Pectin and Essential Oils from Orange and Lemon Peels. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spekreijse, J.; Lammens, T.; Parisi, C.; Ronzon, T.; Vis, M. Insights into the European Market for Bio-Based Chemicals; 2019; Vol. 19.

- Meneguzzo, F.; Brunetti, C.; Fidalgo, A.; Ciriminna, R.; Delisi, R.; Albanese, L.; Zabini, F.; Gori, A.; Nascimento, L.B. dos S.; De Carlo, A.; et al. Real-Scale Integral Valorization of Waste Orange Peel via Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Processes 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurria, A.; Albanese, L.; Pagliaro, M.; Zabini, F.; Giordano, F.; Meneguzzo, F.; Ciriminna, R. Cytrocell: Valued Cellulose from Citrus Processing Waste. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, A.K.; Godínez, L.A.; Espejel, F.; Ramírez-Zamora, R.M.; Robles, I. Optimization of the Integral Valorization Process for Orange Peel Waste Using a Design of Experiments Approach: Production of High-Quality Pectin and Activated Carbon. Waste Management 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.G.; Chau, H.K.; Manthey, J.A. Continuous Process for Enhanced Release and Recovery of Pectic Hydrocolloids and Phenolics from Citrus Biomass. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 2016, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Kharkar, P.S.; Pethe, A.M. Biomass and Waste Materials as Potential Sources of Nanocrystalline Cellulose: Comparative Review of Preparation Methods (2016 – Till Date). Carbohydr Polym 2019, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambuza, A.; Rungqu, P.; Oyedeji, A.O.; Miya, G.M.; Kuria, S.K.; Hosu, S.Y.; Oyedeji, O.O. Extraction, Characterization, and Antioxidant Activity of Pectin from Lemon Peels. Molecules 2024, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraiya, K.; Yadav, V.K.; Choudhary, N.; Ali, D.; Raiyani, D.; Chowdhary, V.A.; Alooparampil, S.; Pandya, R. V.; Sahoo, D.K.; Patel, A.; et al. A Comparative Analysis of the Physico-Chemical Properties of Pectin Isolated from the Peels of Seven Different Citrus Fruits. Gels 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moneim, A.; Sulieman, E.; Khodari, K.M.Y.; Salih, Z.A. Extraction of Pectin from Lemon and Orange Fruits Peels and Its Utilization in Jam Making. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Almagro, N.; Montilla, A.; Moreno, F.J.; Villamiel, M. Modification of Citrus and Apple Pectin by Power Ultrasound: Effects of Acid and Enzymatic Treatment. Ultrason Sonochem 2017, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot-Allain, M.C.N.; Ramasawmy, B.; Emmambux, M.N. Extraction, Characterisation, and Application of Pectin from Tropical and Sub-Tropical Fruits: A Review. Food Reviews International 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, V.; Biswas, D.; Roy, S.; Vaidya, D.; Verma, A.; Gupta, A. Current Advancements in Pectin: Extraction, Properties and Multifunctional Applications. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multari, S.; Licciardello, C.; Caruso, M.; Anesi, A.; Martens, S. Flavedo and Albedo of Five Citrus Fruits from Southern Italy: Physicochemical Characteristics and Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ginés, J.M.; Fernández-López, J.; Sayas-Barberá, E.; Sendra, E.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A. Effect of Storage Conditions on Quality Characteristics of Bologna Sausages Made with Citrus Fiber. J Food Sci 2003, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Naseer, R.; Bhanger, M.I.; Ashraf, S.; Talpur, F.N.; Aladedunye, F.A. Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Citrus Seeds and Seed Oils from Pakistan. JAOCS, Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 2008, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, H.; Yaqoob, S.; Awan, K.A.; Imtiaz, A.; Naveed, H.; Ahmad, N.; Naeem, M.; Sultan, W.; Ma, Y. Unveiling the Chemistry of Citrus Peel: Insights into Nutraceutical Potential and Therapeutic Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Hernández, M.G.; Sánchez-Bravo, P.; Hernández, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Pastor-Pérez, J.J.; Legua, P. Determination of the Volatile Profile of Lemon Peel Oils as Affected by Rootstock. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xiao, H.W.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Hua, C.; Ba, L.; Shamim, S.; Zhang, W. Characterization of Volatile Compounds and Microstructure in Different Tissues of ‘Eureka’ Lemon (Citrus Limon). Int J Food Prop 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Kim, I.D.; Dhungana, S.K.; Park, E.J.; Park, J.J.; Kim, J.H.; Shin, D.H. Quality Characteristics and Antioxidant Potential of Lemon (Citrus Limon Burm. f.) Seed Oil Extracted by Different Methods. Front Nutr 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypriano, D.Z.; da Silva, L.L.; Tasic, L. High Value-Added Products from the Orange Juice Industry Waste. Waste Management 2018, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, R.; Nahar, K.; Zohora, F.T.; Islam, M.M.; Bhuiyan, R.H.; Jahan, M.S.; Shaikh, M.A.A. Pectin from Lemon and Mango Peel: Extraction, Characterisation and Application in Biodegradable Film. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zema, D.A.; Calabrò, P.S.; Folino, A.; Tamburino, V.; Zappia, G.; Zimbone, S.M. Valorisation of Citrus Processing Waste: A Review. Waste Management 2018, 80, 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, D.M.; Maan, S.A.; Abou Baker, D.H.; Abozed, S.S. In Vitro Assessments of Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Cytotoxicity and Anti-Inflammatory Characteristics of Flavonoid Fractions from Flavedo and Albedo Orange Peel as Novel Food Additives. Food Biosci 2024, 62, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, D.; Zhao, C.; Zheng, J. The Structure-Function Relationships of Pectins Separated from Three Citrus Parts: Flavedo, Albedo, and Pomace. Food Hydrocoll 2023, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Kataria, P.; Ahmad, W.; Mishra, R.; Upadhyay, S.; Dobhal, A.; Bisht, B.; Hussain, A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, S. Microwave Assisted Green Extraction of Pectin from Citrus Maxima Albedo and Flavedo, Process Optimization, Characterisation and Comparison with Commercial Pectin. Food Anal Methods 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Park, M.-J. Antioxidant Effects of Essential Oils from the Peels of Citrus Cultivars. Molecules 2025, Vol. 30, Page 833 2025, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alperth, F.; Pogrilz, B.; Schrammel, A.; Bucar, F. Coumarins in the Flavedo of Citrus Limon Varieties—Ethanol and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Extractions With HPLC-DAD Quantification. Phytochemical Analysis 2025, 36, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhu, K.; Liu, Y.; Wen, H.; Kong, J.; Chen, M.; Cao, L.; Ye, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Multiomics Integrated with Sensory Evaluations to Identify Characteristic Aromas and Key Genes in a Novel Brown Navel Orange (Citrus Sinensis). Food Chem 2024, 444, 138613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benestante, A.; Chalapud, M.C.; Baümler, E.; Carrín, M.E. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Lemon (Citrus Lemon) Seeds. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xu, J.; Nasrullah; Wang, L.; Nie, Z.; Huang, X.; Sun, J.; Ke, F. Comprehensive Studies of Biological Characteristics, Phytochemical Profiling, and Antioxidant Activities of Two Local Citrus Varieties in China. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateus, A.R.S.; Mariño-Cortegoso, S.; Barros, S.C.; Sendón, R.; Barbosa, L.; Pena, A.; Sanches-Silva, A. Citrus By-Products: A Dual Assessment of Antioxidant Properties and Food Contaminants towards Circular Economy. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2024, 95, 103737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benestante, A.; Baümler, E.; Carrín, M.E. Drying Kinetics of Lemon (Citrus Lemon) Seeds on Forced-Air Convective Processing. Bioresour Technol Rep 2024, 26, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingegneri, M.; Braghini, M.R.; Piccione, M.; De Stefanis, C.; Mandrone, M.; Chiocchio, I.; Poli, F.; Imbesi, M.; Alisi, A.; Smeriglio, A.; et al. Citrus Pomace as a Source of Plant Complexes to Be Used in the Nutraceutical Field of Intestinal Inflammation. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iervese, F.; Flamminii, F.; D’Alessio, G.; Neri, L.; De Bruno, A.; Imeneo, V.; Valbonetti, L.; Di Mattia, C.D. Flavonoid- and Limonoid-Rich Extracts from Lemon Pomace by-Products: Technological Properties for the Formulation of o/w Emulsions. Food Biosci 2024, 59, 104030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Guleria, S.; Kimta, N.; Nepovimova, E.; Dhalaria, R.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Sethi, N.; Alomar, S.Y.; Kuca, K. Selected Fruit Pomaces: Nutritional Profile, Health Benefits, and Applications in Functional Foods and Feeds. Curr Res Food Sci 2024, 9, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Perspectives on Citrus Pomace Growth: 2025-2033 Insights. Available online: https://www.marketreportanalytics.com/reports/citrus-pomace-247148# (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Okeke, U.J.; Micucci, M.; Mihaylova, D.; Cappiello, A. The Effects of Experimental Conditions on Extraction of Polyphenols from African Nutmeg Peels Using NADESs-UAE: A Multifactorial Modelling Technique. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, E.; Sacristán, I.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E.; Madrid, Y. Effect of Storage and Drying Treatments on Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Composition of Lemon and Clementine Peel Extracts. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zeng, J.; Shen, F.; Xia, X.; Tian, X.; Wu, Z. Citrus Pomace Fermentation with Autochthonous Probiotics Improves Its Nutrient Composition and Antioxidant Activities. LWT 2022, 157, 113076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmus, N.; Gulsunoglu-Konuskan, Z.; Kilic-Akyilmaz, M. Recovery, Bioactivity, and Utilization of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds in Citrus Peel. Food Sci Nutr 2024, 12, 9974–9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, G.I.E.; Naena, N.A.A.; El-Shenawy, A.M.; Khalifa, A.M.A. Effect of Lemon Pomace Inclusion on Growth, Immune Response, Anti-Oxidative Capacity, Intestinal Health, and Disease Resistance against Edwardsiella Tarda Infection in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus). Iran J Fish Sci 2025, 24, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granone, L.I.; Hegel, P.E.; Pereda, S. Citrus Fruit Processing by Pressure Intensified Technologies: A Review. J Supercrit Fluids 2022, 188, 105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon Juice Concentrate Market – Global Market Size, Share, and Trends Analysis Report – Industry Overview and Forecast to 2032 | Data Bridge Market Research. Available online: https://www.databridgemarketresearch.com/reports/global-lemon-juice-concentrate-market (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Lemon Juice Processing Factory | Food and Biotech. Available online: https://www.foodandbiotech.com/from-lemon-to-gummy-exploring-the-journey-of-lemon-juice-and-pectin-processing/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Citrus: World Markets and Trade | USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/citrus-world-markets-and-trade-01302025 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Industrial Citrus Juice Extractor - Making.Com. Available online: https://making.com/equipment/industrial-citrus-juice-extractor (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Challana, V.; Kaimal, A.M.; Shirkole, S.; Sahoo, A.K. Comparative Analysis and Investigation of Ultrasonication on Juice Yield and Bioactive Compounds of Kinnow Fruit Using RSM and ANN Models. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanli, I.; Ozkan, G.; Şahin-Yeşilçubuk, N. Green Extractions of Bioactive Compounds from Citrus Peels and Their Applications in the Food Industry. Food Research International 2025, 212, 116352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hasan, M.F.; Sarkar, A.; Miah, M.S.; Jon, P.H.; Alam, M.; Albasher, G.; Ansari, M.J. Optimization of Hybrid Green Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Compounds from Citrus Lemon Peel Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN). LWT 2025, 230, 118273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinardi, G.; D’Urso, P.R.; Arcidiacono, C.; Muradin, M.; Ingrao, C. A Systematic Literature Review of Environmental Assessments of Citrus Processing Systems, with a Focus on the Drying Phase. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 974, 179219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Maza, S.; Alviz-Meza, A.; Gonzalez-Delgado, A.D. Techno-Economic Analysis of a Cascade Biorefinery for Valorizing Agro-Industrial Waste: A Case Study of Avocado Hass Seed (Persea Americana) from the Amazon Region, Colombia. Chem Eng Trans 2025, 117, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrakakis, I.; Melidis, P.; Kavroulakis, N.; Goliomytis, M.; Simitzis, P.; Ntougias, S. Bioeconomy-Based Approaches for the Microbial Valorization of Citrus Processing Waste. Microorganisms 2025, Vol. 13, Page 1891 2025, 13, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battista, F.; Remelli, G.; Zanzoni, S.; Bolzonella, D. Valorization of Residual Orange Peels: Limonene Recovery, Volatile Fatty Acids, and Biogas Production. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 6834–6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji-Hedfi, L.; Rhouma, A.; Tawfeeq Al-Ani, L.K.; Bargougui, O.; Tlahig, S.; Jaouadi, R.; Zaouali, Y.; Degola, F.; Abdel-Azeem, A.M. The Second Life of Citrus: Phytochemical Characterization and Antifungal Activity Bioprospection of C. Limon and C. Sinensis Peel Extracts Against Potato Rot Disease. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianico, A.; Gallipoli, A.; Gazzola, G.; Pastore, C.; Tonanzi, B.; Braguglia, C.M. A Novel Cascade Biorefinery Approach to Transform Food Waste into Valuable Chemicals and Biogas through Thermal Pretreatment Integration. Bioresour Technol 2021, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petretto, G.L.; Vacca, G.; Addis, R.; Pintore, G.; Nieddu, M.; Piras, F.; Sogos, V.; Fancello, F.; Zara, S.; Rosa, A. Waste Citrus Limon Leaves as Source of Essential Oil Rich in Limonene and Citral: Chemical Characterization, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties, and Effects on Cancer Cell Viability. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visakh, N.U.; Pathrose, B.; Chellappan, M.; Ranjith, M.T.; Sindhu, P.V.; Mathew, D. Chemical Characterisation, Insecticidal and Antioxidant Activities of Essential Oils from Four Citrus Spp. Fruit Peel Waste. Food Biosci 2022, 50, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, I.; Muthukumar, K.; Arunagiri, A. A Review on the Potential of Citrus Waste for D-Limonene, Pectin, and Bioethanol Production. Int J Green Energy 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Lee, Y.R. Extraction, Characterization and Biological Activity of Citrus Flavonoids. Reviews in Chemical Engineering 2019, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addi, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Abid, M.; Tungmunnithum, D.; Elamrani, A.; Hano, C. An Overview of Bioactive Flavonoids from Citrus Fruits. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, C.; Tu, H.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, J.; Deng, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J. Characterization and Metabolic Diversity of Flavonoids in Citrus Species. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Jitan, S.; Scurria, A.; Albanese, L.; Pagliaro, M.; Meneguzzo, F.; Zabini, F.; Al Sakkaf, R.; Yusuf, A.; Palmisano, G.; Ciriminna, R. Micronized Cellulose from Citrus Processing Waste Using Water and Electricity Only. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 204, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketipally, R.; Kranthi Kumar, G.; Raghu Ram, M. Polygalacturonase Production by Aspergillus Nomius MR103 in Solid State Fermentation Using Agro-Industrial Wastes. Journal of Applied and Natural Science 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariq, M.; Sohail, M. Citrus Limetta Peels: A Promising Substrate for the Production of Multienzyme Preparation from a Yeast Consortium. Bioresour Bioprocess 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patinvoh, R.J.; Lundin, M.; Taherzadeh, M.J.; Sárvári Horváth, I. Dry Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Citrus Wastes with Keratin and Lignocellulosic Wastes: Batch And Continuous Processes. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yu, S.; Zhu, R.; Zhong, C.; Zou, H.; Gu, L.; He, Q. Effects of Citrus Peel Biochar on Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste and Sewage Sludge and Its Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer Pathway Study. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, L.D.M.; Pachiega, R.; Crespi, M.S.; Nespeca, M.G.; de Oliveira, J.E.; Maintinguer, S.I. Potential of Biohydrogen Production from Effluents of Citrus Processing Industry Using Anaerobic Bacteria from Sewage Sludge. Waste Management 2017, 59, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajoo, A.; Wong, Y.L.; Khoo, K.S.; Chen, W.H.; Show, P.L. Biochar Production via Pyrolysis of Citrus Peel Fruit Waste as a Potential Usage as Solid Biofuel. Chemosphere 2022, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.D.; da Boit Martinello, K.; Knani, S.; Lütke, S.F.; Machado, L.M.M.; Manera, C.; Perondi, D.; Godinho, M.; Collazzo, G.C.; Silva, L.F.O.; et al. Pyrolysis of Citrus Wastes for the Simultaneous Production of Adsorbents for Cu(II), H2, and D-Limonene. Waste Management 2022, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heerden, I.; Cronjé, C.; Swart, S.H.; Kotzé, J.M. Microbial, Chemical and Physical Aspects of Citrus Waste Composting. Bioresour Technol 2002, 81, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.S.; Lee, Y.G.; Khanal, S.K.; Park, B.J.; Bae, H.-J. A Low-Energy, Cost-Effective Approach to Fruit and Citrus Peel Waste Processing for Bioethanol Production. Appl Energy 2015, 140, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, C.; Pampinella, D.; Palazzolo, E.; Badalucco, L.; Laudicina, V.A. From Waste to Resources: Sewage Sludges from the Citrus Processing Industry to Improve Soil Fertility and Performance of Lettuce (Lactuca Sativa L.). Agriculture (Switzerland) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.K.; Cha, J.Y.; Kang, M.C.; Jang, H.W.; Choi, Y.S. The Effects of Different Extraction Methods on Essential Oils from Orange and Tangor: From the Peel to the Essential Oil. Food Sci Nutr 2024, 12, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šafranko, S.; Šubarić, D.; Jerković, I.; Jokić, S. Citrus By-Products as a Valuable Source of Biologically Active Compounds with Promising Pharmaceutical, Biological and Biomedical Potential. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Koteswararao, R.; Sinha, M.; Baral, E.R.; Cho, M.H. Citrus Essential Oils: Extraction, Authentication and Application in Food Preservation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Mas, M.C.; Rambla, J.L.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Amparo Blázquez, M.; Granell, A. Volatile Compounds in Citrus Essential Oils: A Comprehensive Review. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekar, C.M.; Carullo, D.; Saitta, F.; Krishnamachari, H.; Bellesia, T.; Nespoli, L.; Caneva, E.; Baschieri, C.; Signorelli, M.; Barbiroli, A.G.; et al. Valorization of Citrus Peel Industrial Wastes for Facile Extraction of Extractives, Pectin, and Cellulose Nanocrystals through Ultrasonication: An in-Depth Investigation. Carbohydr Polym 2024, 344, 122539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Gan, D.; Fan, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, X. Dietary Fiber Extraction from Citrus Peel Pomace: Yield Optimization and Evaluation of Its Functionality, Rheological Behavior, and Microstructure Properties. J Food Sci 2023, 88, 3507–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rownaghi, M.; Niakousari, M. Sour Orange (Citrus Aurantium) Seed, a Rich Source of Protein Isolate and Hydrolysate – A Thorough Investigation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas Ulloa, P.; Ulloa, J.A.; Ulloa Rangel, B.E.; López Mártir, K.U. Protein Isolate from Orange (Citrus Sinensis L.) Seeds: Effect of High-Intensity Ultrasound on Its Physicochemical and Functional Properties. Food Bioproc Tech 2023, 16, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophoridis, C.; Touloupi, M.; Bizani, E.A.; Iossifidis, D. Polyphenol Extraction from Industrial Water By-Products: A Case Study of the ULTIMATE Project in the Fruit Processing Industry. Water Science and Technology 2025, 91, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioppolo, A.; Laudicina, V.A.; Badalucco, L.; Saiano, F.; Palazzolo, E. Wastewaters from Citrus Processing Industry as Natural Biostimulants for Soil Microbial Community. J Environ Manage 2020, 273, 111137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Mendoza, E.S.; Méndez-Contreras, J.M.; Aguilar-Lasserre, A.A.; Vallejo-Cantú, N.A.; Alvarado-Lassman, A. Evaluation of Bioenergy Potential from Citrus Effluents through Anaerobic Digestion. J Clean Prod 2020, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.S.; Muruganandam, L.; Ganesh Moorthy, I. Pectin from Fruit Peel: A Comprehensive Review on Various Extraction Approaches and Their Potential Applications in Pharmaceutical and Food Industries. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Blázquez, S.; Gómez-Mejía, E.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E. Recent Insights into Eco-Friendly Extraction Techniques for Obtaining Bioactive Compounds from Fruit Seed Oils. Foods 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Xie, J.; Gao, B.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, D. Sustainable and Green Extraction of Citrus Peel Essential Oil Using Intermittent Solvent-Free Microwave Technology. Bioresources and Bioprocessing 2025 12:1 2025, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Abad, A.; Ramos, M.; Hamzaoui, M.; Kohnen, S.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. Optimisation of Sequential Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Essential Oil and Pigment from Lemon Peels Waste. Foods 2020, Vol. 9, Page 1493 2020, 9, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teke, G.M.; De Vos, L.; Smith, I.; Kleyn, T.; Mapholi, Z. Development of an Ultrasound-Assisted Pre-Treatment Strategy for the Extraction of d-Limonene toward the Production of Bioethanol from Citrus Peel Waste (CPW). Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering 2023 46:11 2023, 46, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, T.C.; Tran, N.T.; Mai, D.T.; Ngoc Mai, T.T.; Thuc Duyen, N.H.; Minh An, T.N.; Alam, M.; Dang, C.H.; Nguyen, T.D. Supercritical CO2 Assisted Extraction of Essential Oil and Naringin from Citrus Grandis Peel: In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Docking Study. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 25962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; De Luca, L.; Aiello, A.; Rossi, D.; Pizzolongo, F.; Masi, P. Bioactive Compounds Extracted by Liquid and Supercritical Carbon Dioxide from Citrus Peels. Int J Food Sci Technol 2022, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B.; Winterburn, J.; Gonzalez-Miquel, M. Orange Peel Waste Valorisation through Limonene Extraction Using Bio-Based Solvents. Biochem Eng J 2019, 151, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyamol, N.; Gada Chengaiyan, J.; Rana, S.S.; Ahmad, F.; Haque, S.; Capanoglu, E. Recent Advances in the Extraction of Pectin from Various Sources and Industrial Applications. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 46309–46324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Swami Hulle, N.R. Citrus Pectins: Structural Properties, Extraction Methods, Modifications and Applications in Food Systems – A Review. Applied Food Research 2022, 2, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, M.; Singh, D.P.; Singh, S.; Khubber, S.; Garg, M.; Krishania, M. Microwave-Assisted Acid Extraction of High-Methoxyl Kinnow (Citrus Reticulata) Peels Pectin: Process, Techno-Functionality, Characterization and Life Cycle Assessment. Food Chemistry: Molecular Sciences 2024, 9, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurić, M.; Golub, N.; Galić, E.; Radić, K.; Maslov Bandić, L.; Vitali Čepo, D. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Mandarin Peel: A Comprehensive Biorefinery Strategy. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, S.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Zhou, T.; Xu, F.; Wang, R.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Wu, P. High-Intensity Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Acidic Extraction of Pectin from Citrus Peel: Physicochemical Characteristics and Emulsifying Properties. Food Hydrocoll 2024, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.J.; Sarkar, S.; Sharmin, T.; Mondal, S.C. Extraction of Pectin from Powdered Citrus Peels Using Various Acids: An Analysis Contrasting Orange with Lime. Applied Food Research 2024, 4, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Akram, S.; Khalid, S.; Amin, L.; Ahmad, F.; Malhat, F.; Muhammad, G.; Ashraf, R.; Mushtaq, M. Citric Acid–Assisted Extraction of High Methoxy Pectin from Grapefruit Peel and Its Application as Milk Stabilizer. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2025 18:7 2025, 18, 6134–6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaus, B.; Özcanb, M.M. Chemical Evaluation of Citrus Seeds, an Agro-Industrial Waste, as a New Potential Source of Vegetable Oils. Grasas y Aceites 2012, 63, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, C.; Morrone, R.; D’Antona, N.; Ruberto, G.; Napoli, E. Lemon Seed Oil: An Alternative Source for the Production of Glycerol-Free Biodiesel. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2022, 16, 1726–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albergamo, A.; Costa, R.; Dugo, G. Cold Pressed Lemon (Citrus Limon) Seed Oil. Cold Pressed Oils: Green Technology, Bioactive Compounds, Functionality, and Applications 2020, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, B.R.; Dorado, C.; Bantchev, G.B.; Winkler-Moser, J.K.; Doll, K.M. Production and Evaluation of Biodiesel from Sweet Orange (Citrus Sinensis) Lipids Extracted from Waste Seeds from the Commercial Orange Juicing Process. Fuel 2023, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Hassan, N.; Ali, H.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Jahan, Z.; Ghuman, I.L.; Hassan, F.; Saqib, A. An Overview of Key Industrial Product Citric Acid Production by Aspergillus Niger and Its Application. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2025, 52, kuaf007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Hassan, N.; Ali, H.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Jahan, Z.; Ghuman, I.L.; Hassan, F.; Saqib, A. An Overview of Key Industrial Product Citric Acid Production by Aspergillus Niger and Its Application. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2025, 52, kuaf007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Yu, Y.; Deng, L.; Wang, F. Efficient Catalytic Conversion of Acetate to Citric Acid and Itaconic Acid by Engineered Yarrowia Lipolytica. Catalysts 2024, 14, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.P.; Modak, D.; Sarkar, S.; Roy, S.K.; Sah, S.P.; Ghatani, K.; Bhattacharjee, S. Fruit Waste: A Current Perspective for the Sustainable Production of Pharmacological, Nutraceutical, and Bioactive Resources. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1260071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zamora, L.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Artés-Hernández, F.; Castillejo, N. Flavonoid Extracts from Lemon By-Products as a Functional Ingredient for New Foods: A Systematic Review. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haytowitz, D.B.; Wu, X.; Bhagwat, S. USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods Release 3.3 Prepared By. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Kotsou, K.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Response Surface Optimization for the Enhancement of the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Citrus Limon Peel. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Sinha, M.; Cho, M.H. Citrus Waste Derived Nutra-/Pharmaceuticals for Health Benefits: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. J Funct Foods 2018, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprakçı, G.; Toprakçı, İ.; Şahin, S. Highly Clean Recovery of Natural Antioxidants from Lemon Peels: Lactic Acid-Based Automatic Solvent Extraction. Phytochemical Analysis 2022, 33, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Gómez, V.; San Mateo, M.; González-Barrio, R.; Periago, M.J. Chemical Composition, Functional and Antioxidant Properties of Dietary Fibre Extracted from Lemon Peel after Enzymatic Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hsouna, A.; Ben Halima, N.; Smaoui, S.; Hamdi, N. Citrus Lemon Essential Oil: Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities with Its Preservative Effect against Listeria Monocytogenes Inoculated in Minced Beef Meat. Lipids Health Dis 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, E.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E.; Madrid, Y. Citrus Peels Waste as a Source of Value-Added Compounds: Extraction and Quantification of Bioactive Polyphenols. Food Chem 2019, 295, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, Z.; Khalid, W.; Atiq, H.T.; Koraqi, H.; Javaid, Z.; Alhag, S.K.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Bader, D.M.D.; Almarzuq, M.; Afifi, M.; et al. Citrus Waste as Source of Bioactive Compounds: Extraction and Utilization in Health and Food Industry. Molecules 2023, Vol. 28, Page 1636 2023, 28, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnik, P.; Kresoja, Ž.; Bosiljkov, T.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Roohinejad, S.; Granato, D.; Žuntar, I.; Bursać Kovačević, D. Comparing the Effects of Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies on Pomegranate Juice Quality: A Review. Food Chem 2019, 279, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, M.; Hamdi, Z.; Zemni, H.; Rahali, F.Z.; Melki, I.; Mliki, A.; Gargouri, M. From Residue to Resource: The Recovery of High-Added Values Compounds through an Integral Green Valorization of Citrus Residual Biomass. Sustain Chem Pharm 2024, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Banerjee, J.; Ahmed, R.; Dash, S.K. Potential Benefits of Bioactive Functional Components of Citrus Fruits for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Recent Advances in Citrus Fruits 2023, 451–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Ranjit, A.; Sharma, K.; Prasad, P.; Shang, X.; Gowda, K.G.M.; Keum, Y.S. Bioactive Compounds of Citrus Fruits: A Review of Composition and Health Benefits of Carotenoids, Flavonoids, Limonoids, and Terpenes. Antioxidants 2022, Vol. 11, Page 239 2022, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-gálvez, M.Á.; Giménez-bastida, J.A.; González-sarrías, A.; Espín, J.C. New Insights into the Metabolism of the Flavanones Eriocitrin and Hesperidin: A Comparative Human Pharmacokinetic Study. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Li, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, O.; Huang, L.; Guo, L.; Gao, W. A Review of Chemical Constituents and Health-Promoting Effects of Citrus Peels. Food Chem 2021, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Yao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Meng, X.; Zhou, T.; Gu, Q. Citrus Peel Flavonoid Extracts: Health-Beneficial Bioactivities and Regulation of Intestinal Microecology in Vitro. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasdaran, A.; Hamedi, A.; Shiehzadeh, S.; Hamedi, A. A Review of Citrus Plants as Functional Foods and Dietary Supplements for Human Health, with an Emphasis on Meta-Analyses, Clinical Trials, and Their Chemical Composition. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2023, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Yadav, M.P. Insights into the Chemical Composition and Bioactivities of Citrus Peel Essential Oils. Food Research International 2021, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Sinha, M.; Dhyani, A.; Pathak, B.; Jang, H.; Park, S.; Pashikanti, S.; Cho, S. Biotransformation of Citrus Waste-I: Production of Biofuel and Valuable Compounds by Fermentation. Processes 2021, Vol. 9, Page 220 2021, 9, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biz, A.; Finkler, A.T.J.; Pitol, L.O.; Medina, B.S.; Krieger, N.; Mitchell, D.A. Production of Pectinases by Solid-State Fermentation of a Mixture of Citrus Waste and Sugarcane Bagasse in a Pilot-Scale Packed-Bed Bioreactor. Biochem Eng J 2016, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.A.; Contato, A.G.; de Oliveira, F.; da Silva, S.S.; Hidalgo, V.B.; Irfan, M.; Gambarato, B.C.; Carvalho, A.K.F.; Bento, H.B.S. Trends in Enzyme Production from Citrus By-Products. Processes 2025, Vol. 13, Page 766 2025, 13, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, C.G.; Hours, R.A. Citrus Waste: An Alternative Substrate for Pectinase Production in Solid-State Culture. Bioresour Technol 1992, 39, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, M.; Najafpour, G.D.; Mohammadi, M. Bioconversion of Agroindustrial Wastes to Pectinases Enzyme via Solid State Fermentation in Trays and Rotating Drum Bioreactors. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2019, 21, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awe, T.A.; Ademakinwa, A.N.; Famurewa, A.J.; Ayinla, Z.A.; Agunbiade, M.O. Production of Garbage Enzymes and Fermentable Sugars from Single and Combined Agro-Wastes via Anaerobic Fermentation for Bioethanol Generation: An Integrative Omics Approach. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 203, 108301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thite, V.S.; Nerurkar, A.S.; Baxi, N.N. Optimization of Concurrent Production of Xylanolytic and Pectinolytic Enzymes by Bacillus Safensis M35 and Bacillus Altitudinis J208 Using Agro-Industrial Biomass through Response Surface Methodology. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, M.K.; Nighojkar, S.; Kumar, A.; Nighojkar, A. Pectinolytic Enzymes-Solid State Fermentation, Assay Methods and Applications in Fruit Juice Industries: A Review. 3 Biotech 2018 8:4 2018, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, H.A.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Rodríguez, R.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. Pectinase Production from Lemon Peel Pomace as Support and Carbon Source in Solid-State Fermentation Column-Tray Bioreactor. Biochem Eng J 2012, 65, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Enshasy, H.A.; Elsayed, E.A.; Suhaimi, N.; Malek, R.A.; Esawy, M. Bioprocess Optimization for Pectinase Production Using Aspergillus Niger in a Submerged Cultivation System. BMC Biotechnol 2018, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, S.; Ayele, A. Pectinase from Microorganisms and Its Industrial Applications. The Scientific World Journal 2022, 2022, 1881305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.J.; Jeong, D.; Kim, S.R. Upstream Processes of Citrus Fruit Waste Biorefinery for Complete Valorization. Bioresour Technol 2022, 362, 127776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchette, I.R.; Cavallari, R.B.C.; Rothier, F. do C.; Bojorge, N.I.B.R.; Alhadeff, E.M.; Young, A.F.; dos Santos, B.F. Economic Assessment and Process Design to Valorize Citrus Juice Industry Waste. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2025, 19, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.A.; Ruiz, H.A.; Krieger, N.A.; Mitchell, D.A.; Ruiz, H.A.; Krieger, N. A Critical Evaluation of Recent Studies on Packed-Bed Bioreactors for Solid-State Fermentation. Processes 2023, Vol. 11, Page 872 2023, 11, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagaito, A.N.; Takagi, H.; Watanabe, T. Molding of All-Cellulose Plates Made of Cellulose Pulp Extracted from Citrus Fruit Residue. BioResources 2025, 20, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolo, M.R.V.; Pereira, T.S.; dos Santos, F. V.; Facure, M.H.M.; dos Santos, F.; Teodoro, K.B.R.; Mercante, L.A.; Correa, D.S. Citrus Wastes as Sustainable Materials for Active and Intelligent Food Packaging: Current Advances. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2025, 24, e70144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Velázquez, G.G.; Lugo-Lugo, V.; Meléndez-González, P.C.; Pech-Rodríguez, W.J. Carbon Derived from Citrus Peel Waste: Advances in Synthesis Methods and Emerging Trends for Potential Applications—a Review. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsalou, M.; Samanides, C.G.; Protopapa, E.; Stavrinou, S.; Vyrides, I.; Koutinas, M. A Citrus Peel Waste Biorefinery for Ethanol and Methane Production. Molecules 2019, Vol. 24, Page 2451 2019, 24, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiasa, S.; Iwamoto, S.; Endo, T.; Edashige, Y. Isolation of Cellulose Nanofibrils from Mandarin (Citrus Unshiu) Peel Waste. Ind Crops Prod 2014, 62, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Petri, G.L.; Angellotti, G.; Fontananova, E.; Luque, R.; Pagliaro, M. Nanocellulose and Microcrystalline Cellulose from Citrus Processing Waste: A Review. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 281, 135865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohni, S.; Begum, S.; Hashim, R.; Khan, S.B.; Mazhar, F.; Syed, F.; Khan, S.A. Physicochemical Characterization of Microcrystalline Cellulose Derived from Underutilized Orange Peel Waste as a Sustainable Resource under Biorefinery Concept. Bioresour Technol Rep 2024, 25, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, M.; Palanisamy, S.; Khan, R.; H. Alrasheedi, N.; Tadepalli, S.; Murugesan, T. mani; Santulli, C. Synthesis and Suitability Characterization of Microcrystalline Cellulose from Citrus x Sinensis Sweet Orange Peel Fruit Waste-Based Biomass for Polymer Composite Applications. Journal of Polymer Research 2024 31:4 2024, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.A.N.; Jai, J. Response Surface Methodology for Optimization of Cellulose Extraction from Banana Stem Using NaOH-EDTA for Pulp and Papermaking. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanova, E.; Ciriminna, R.; Talarico, D.; Galiano, F.; Figoli, A.; Di Profio, G.; Mancuso, R.; Gabriele, B.; Angellotti, G.; Li Petri, G.; et al. CytroCell@PIL: A New Citrus Nanocellulose-Polymeric Ionic Liquid Composite for Enhanced Anion Exchange Membrane Alkaline Water Electrolysis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.S.A.; Pohlmann, B.C.; Calado, V.; Bojorge, N.; Pereira, N. Production of Nanocellulose by Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Trends and Challenges. Eng Life Sci 2019, 19, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, R.W.N.; Tardy, B.L.; Eldin, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Mahardika, M.; Masruchin, N. Controlling the Critical Parameters of Ultrasonication to Affect the Dispersion State, Isolation, and Chiral Nematic Assembly of Cellulose Nanocrystals. Ultrason Sonochem 2023, 99, 106581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, M.; Vidal, D.; Bertrand, F.; Tavares, J.R.; Heuzey, M.C. Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Ultrasonic Dispersion of Cellulose Nanocrystals. Ultrason Sonochem 2021, 71, 105378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, C.M.; Carullo, D.; Saitta, F.; Krishnamachari, H.; Bellesia, T.; Nespoli, L.; Caneva, E.; Baschieri, C.; Signorelli, M.; Barbiroli, A.G.; et al. Valorization of Citrus Peel Industrial Wastes for Facile Extraction of Extractives, Pectin, and Cellulose Nanocrystals through Ultrasonication: An in-Depth Investigation. Carbohydr Polym 2024, 344, 122539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerxun, D.; Pulingam, T.; Nordin, N.I.; Chen, Y.W.; Kamaldin, J. Bin; Julkapli, N.B.M.; Lee, H.V.; Leo, B.F.; Johan, M.R. Bin Synthesis, Characterization and Cytotoxicity Studies of Nanocrystalline Cellulose from the Production Waste of Rubber-Wood and Kenaf-Bast Fibers. Eur Polym J 2019, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, A. Nanocellulose: A New Ageless Bionanomaterial. Materials Today 2013, 16, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Bian, J.; Ma, M.-G. Advances in Biomedical Application of Nanocellulose-Based Materials: A Review. Curr Med Chem 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.E.; Ahmad, I.; Thomas, S.; Kassim, M.B.; Daik, R. Nanocellulose-Based Separators in Lithium-Ion Battery | Pemisah Berasaskan Nanoselulosa Dalam Bateri Litium Ion. Sains Malays 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, T. V.; Patel, D.K.; Dutta, S.D.; Ganguly, K.; Santra, T.S.; Lim, K.T. Nanocellulose, a Versatile Platform: From the Delivery of Active Molecules to Tissue Engineering Applications. Bioact Mater 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas de Oliveira, C.; Giordani, D.; Lutckemier, R.; Gurak, P.D.; Cladera-Olivera, F.; Ferreira Marczak, L.D. Extraction of Pectin from Passion Fruit Peel Assisted by Ultrasound. LWT 2016, 71, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultrasonic Pectin Extraction from Fruit and Bio-Waste - Hielscher Ultrasonics. Available online: https://www.hielscher.com/ultrasonic-pectin-extraction-from-fruit-and-bio-waste.htm (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Maqbool, Z.; Khalid, W.; Atiq, H.T.; Koraqi, H.; Javaid, Z.; Alhag, S.K.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Bader, D.M.D.; Almarzuq, M.; Afifi, M.; et al. Citrus Waste as Source of Bioactive Compounds: Extraction and Utilization in Health and Food Industry. Molecules 2023, Vol. 28, Page 1636 2023, 28, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Lee, Y.R. Extraction, Characterization and Biological Activity of Citrus Flavonoids. Reviews in Chemical Engineering 2019, 35, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.C.; Tran, N.T.; Mai, D.T.; Ngoc Mai, T.T.; Thuc Duyen, N.H.; Minh An, T.N.; Alam, M.; Dang, C.H.; Nguyen, T.D. Supercritical CO2 Assisted Extraction of Essential Oil and Naringin from Citrus Grandis Peel: In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Docking Study. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 25962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anticona, M.; Blesa, J.; Frigola, A.; Esteve, M.J. High Biological Value Compounds Extraction from Citrus Waste with Non-Conventional Methods. Foods 2020, Vol. 9, Page 811 2020, 9, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandare, R.D.; Tomke, P.D.; Rathod, V.K. Kinetic Modeling and Process Intensification of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of d-Limonene Using Citrus Industry Waste. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 2021, 159, 108181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, U.; Shah, S.M.; Gul, M.Y. Analysis of Conventional and Microwave Assisted Technique for the Extraction of Concentrated Oils from Citrus Peel. International journal of Engineering Works 2020, 7, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbuz, P.; Tugrul, N. Microwave and Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Pectin from Various Fruits Peel. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 58, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, B.; Dahmoune, F.; Moussi, K.; Remini, H.; Dairi, S.; Aoun, O.; Khodir, M. Comparison of Microwave, Ultrasound and Accelerated-Assisted Solvent Extraction for Recovery of Polyphenols from Citrus Sinensis Peels. Food Chem 2015, 187, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Srivastav, S.; Sharanagat, V.S. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable Processing by-Products: A Review. Ultrason Sonochem 2020, 70, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Srivastav, S.; Sharanagat, V.S. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable Processing by-Products: A Review. Ultrason Sonochem 2021, 70, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiruvalluvan, M.; Gupta, R.; Kaur, B.P. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Conditions for the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Sweet Lime Peel Waste. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024 15:5 2024, 15, 6781–6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anticona, M.; Blesa, J.; Lopez-Malo, D.; Frigola, A.; Esteve, M.J. Effects of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction on Physicochemical Properties, Bioactive Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity for the Valorization of Hybrid Mandarin Peels. Food Biosci 2021, 42, 101185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Salazar, L.F.; Cuenca-Quicazán, M.; López-Padilla, A.; Perea-Salazar, L.F.; Cuenca-Quicazán, M.; López-Padilla, A. Tecnologías Emergentes Para La Extracción de Compuestos a Partir de Residuos Del Cacao: Una Revisión Bibliográfica. Entramado 2025, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, H. Ben; Abbassi, A.; Trabelsi, A.; Krichen, Y.; Chekir-Ghedira, L.; Ghedira, K. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols and Flavonoids from Citrus Aurantium L. Var. Amara Engl. Fruit Peel Using Response Surface Methodology. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023 14:13 2023, 14, 14139–14151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Torres, N.; Espinosa-Andrews, H.; Trombotto, S.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Patrón-Vázquez, J.; González-Flores, T.; Sánchez-Contreras, Á.; Cuevas-Bernardino, J.C.; Pacheco, N. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Optimization of Phenolic Compounds from Citrus Latifolia Waste for Chitosan Bioactive Nanoparticles Development. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rodríguez, G.; Amador-Luna, V.M.; Castro-Puyana, M.; Ibáñez, E.; Marina, M.L. Sustainable Strategies to Obtain Bioactive Compounds from Citrus Peels by Supercritical Fluid Extraction, Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction, and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Food Research International 2025, 202, 115713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanco-Lugo, E.; Martínez-Castillo, J.I.; Cuevas-Bernardino, J.C.; González-Flores, T.; Valdez-Ojeda, R.; Pacheco, N.; Ayora-Talavera, T. Citrus Pectin Obtained by Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction: Physicochemical, Structural, Rheological and Functional Properties. CYTA - Journal of Food 2019, 17, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Londoño, J.; Lima, V.R. de; Lara, O.; Gil, A.; Pasa, T.B.C.; Arango, G.J.; Pineda, J.R.R. Clean Recovery of Antioxidant Flavonoids from Citrus Peel: Optimizing an Aqueous Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Method. Food Chem 2010, 119, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Guo, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Sarengaowa; Xiao, Y.; Feng, K. Recent Advances in the Health Benefits and Application of Tangerine Peel (Citri Reticulatae Pericarpium): A Review. Foods 2024, Vol. 13, Page 1978 2024, 13, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argun, M.E.; Argun, M.Ş.; Arslan, F.N.; Nas, B.; Ates, H.; Tongur, S.; Cakmakcı, O. Recovery of Valuable Compounds from Orange Processing Wastes Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction. J Clean Prod 2022, 375, 134169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Kaur, S.; Panesar, P.S.; Thakur, A. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Essential Oils from Citrus Reticulata Peels: Optimization and Characterization Studies. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022 13:16 2022, 13, 14605–14614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, T.; Ciftci, O.N. A Step-by-Step Technoeconomic Analysis of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction of Lycopene from Tomato Processing Waste. J Food Eng 2023, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacís-Chiriboga, J.; Vera, E.; Van Camp, J.; Ruales, J.; Elst, K. Valorization of Byproducts from Tropical Fruits: A Review, Part 2: Applications, Economic, and Environmental Aspects of Biorefinery via Supercritical Fluid Extraction. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaprasad, D.E.J.; Hegde, K.R.; Somasundaram, K.D.; Manickam, L. Recent Advancements in Citrus By-Product Utilization for Sustainable Food Production. Food Biomacromolecules 2025, 2, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.; Abdullah, S.; Pradhan, R.C. Review on the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds and Characterization of Fruit Industry By-Products. Bioresources and Bioprocessing 2022 9:1 2022, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula Menezes Barbosa, P.; Roggia Ruviaro, A.; Mateus Martins, I.; Alves Macedo, J.; Lapointe, G.; Alves Macedo, G. Effect of Enzymatic Treatment of Citrus By-Products on Bacterial Growth, Adhesion and Cytokine Production by Caco-2 Cells. Food Funct 2020, 11, 8996–9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas de Oliveira, C.; Giordani, D.; Lutckemier, R.; Gurak, P.D.; Cladera-Olivera, F.; Ferreira Marczak, L.D. Extraction of Pectin from Passion Fruit Peel Assisted by Ultrasound. LWT 2016, 71, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooruee, R.; Hojjati, M.; Behbahani, B.A.; Shahbazi, S.; Askari, H. Extracellular Enzyme Production by Different Species of Trichoderma Fungus for Lemon Peel Waste Bioconversion. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022 14:2 2022, 14, 2777–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.V.; Coniglio, R.O.; Ortellado, L.E.; Zapata, P.D.; Martínez, M.A.; Fonseca, M.I. Low-Cost Extraction of Multifaceted Biological Compounds from Citrus Waste Using Enzymes from Aspergillus Niger LBM 134. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition 2025 7:1 2025, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, F.; Occhiuzzi, M.A.; Perri, M.R.; Ioele, G.; Rizzuti, B.; Statti, G.; Garofalo, A. Polyphenols from Citrus Tacle® Extract Endowed with HMGCR Inhibitory Activity: An Antihypercholesterolemia Natural Remedy. Molecules 2021, Vol. 26, Page 5718 2021, 26, 5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, R.; Malgas, S. Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction of Orange Peel Pectin and Its Characterisation. Int J Food Sci Technol 2023, 58, 6784–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot-Allain, C.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Ak, G.; Zengin, G. Conventional versus Green Extraction Techniques — a Comparative Perspective. Curr Opin Food Sci 2021, 40, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanli, I.; Ozkan, G.; Şahin-Yeşilçubuk, N. Green Extractions of Bioactive Compounds from Citrus Peels and Their Applications in the Food Industry. Food Research International 2025, 212, 116352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Hassan, S.S.; Williams, G.A.; Jaiswal, A.K. A Review on Bioconversion of Agro-Industrial Wastes to Industrially Important Enzymes. Bioengineering 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.R.; Marzuki, N.H.C.; Buang, N.A.; Huyop, F.; Wahab, R.A. An Overview of Technologies for Immobilization of Enzymes and Surface Analysis Techniques for Immobilized Enzymes. Biotechnology and Biotechnological Equipment 2015, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louise, B.; Decker, A.; Fonteles, T.V.; Fernandes, F.A.N.; Rodrigues, S. Green Extraction Technologies for Valorising Brazilian Agri-Food Waste. Sustainable Food Technology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Sridhar, K.; Gupta, V.K.; Dikkala, P.K. Greener Technologies in Agri-Food Wastes Valorization for Plant Pigments: Step towards Circular Economy. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.M.J. Advances in Green Technologies for Bioactive Extraction and Valorization of Agro-Waste in Food and Nutraceutical Industries. Haya: The Saudi Journal of Life Sciences 2025, 10, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]