1. Introduction

Seeing unreal phenomena without being psychotic can often be attributed to entoptic phenomena such as retinal vessel shadows [

1], perifoveal circulation of leukocytes or phosphenes elicited by the pull of extraocular muscles during voluntary eye movements [

2], ocular diseases such retinal or vitreous detachment [

3,

4], intraocular hemorrhage [

5], corneal edema in narrow angle glaucoma [

6], and migraine aura [

7]. Here, we describe what appears to be a hitherto undescribed type of episodic dim rhythmic flicker, of stationary location and extent during the event, which is seen as an overlay on an otherwise intact part of the binocular visual field.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective ancillary analysis was based upon a study of fundus imaging methodology that recruited volunteer patients from of a medical retina clinic. Patients gave written informed consent, and all procedures followed the Helsinki Declaration and were approved by Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics (H-19068888).

A patient (

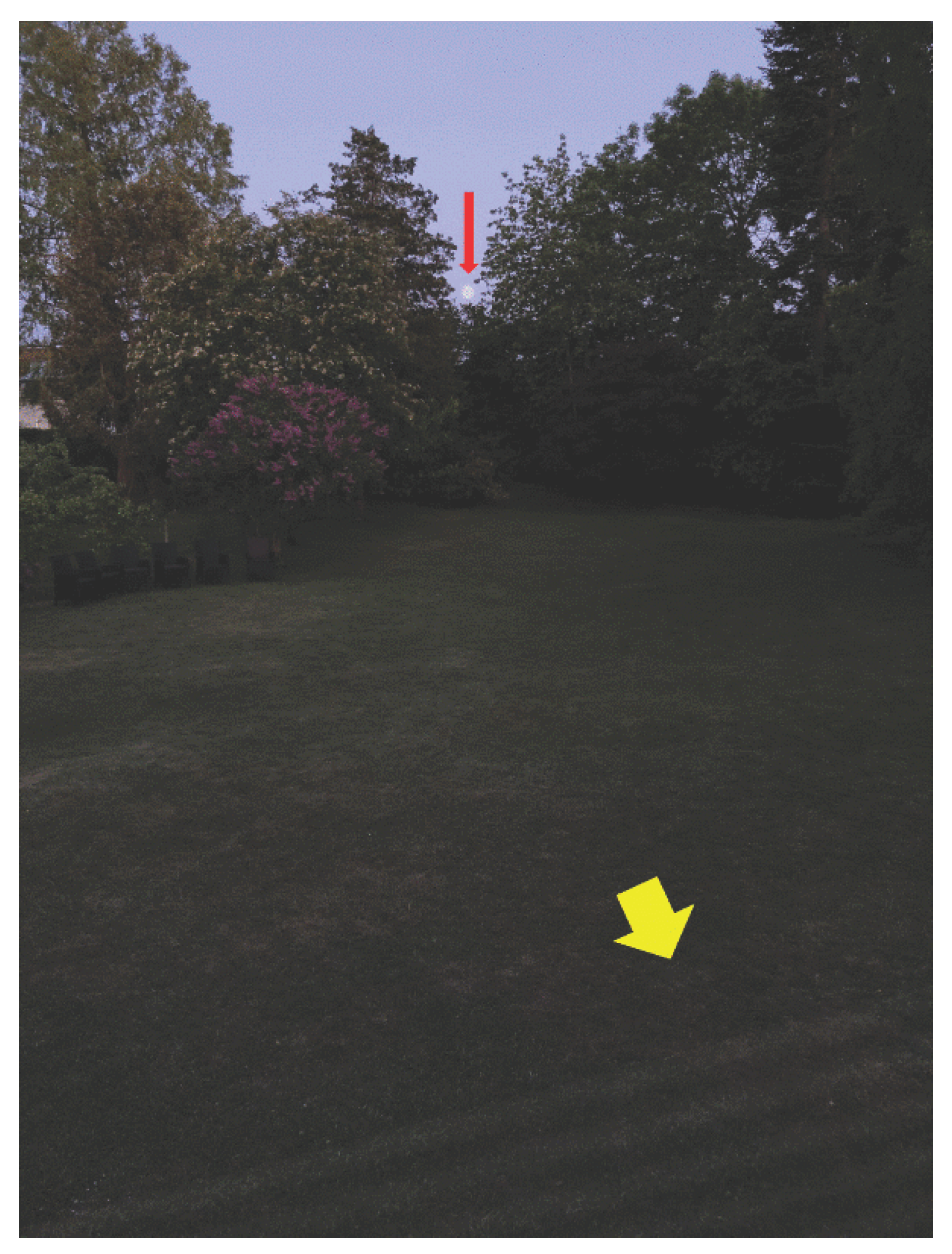

Table 1; Patient 1) brought attention to the flicker phenomenon and provided a thorough description that prompted an animated simulation (

Figure 1, for an animated version see online

supplementary material). The other three patients were interviewed using the animation. Patients were asked to compare their flicker’s location, extent, rate, transparency, and background contrast with the simulation. They were also asked about their first event, repetition rate, time of day, duration, and precipitating or modifying factors. Medical history and medication use were recorded (

Table 1).

An electronic search on PubMed, Google Scholar, and SCOPUS were conducted using terms that describe established endogenous visual experiences, including entoptic phenomenon, retrobulbar, and those of uncertain origin. The keywords “entoptic phenomenon”, “entoptic flicker”, “entoptic pulsating”, and “dim flicker” achieved 353 hits, but found no description of rhythmically pulsating endogenous visual experience compatible with dim flicker, except two patients in one migraine aura study provided short unstructured verbal descriptions that may be compatible [

8], but only covered a small fraction of dim flicker characteristics. The literature search is limited by disease classifications like ICD-10 that provide few visual disturbance details. The literature search was completed on July 14, 2025

3. Results

Case 1

A 48-year-old man presented for a routine eye examination. His past medical history included migraine with visual aura, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and pacemaker implantation. His medications were metoprolol, losartan, amlodipine and apixaban. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 1.25 Snellen in both eyes, refraction -0,5 spherical in both eyes, and applanation tonometry 12 mmHg in both eyes. Automated perimetry was well within normal limits. His visual migraine aura was mostly paracentral and negative, less often positive with scintillations, never with a rhythmic flicker and mostly without subsequent headache.

The patient initially noticed a flickering overlay in the inferior periphery of his binocular visual field two years ago while cross-country skiing at night on a dimly illuminated path. It was centered to the left of the vertical midline and extended into the right lower quadrant. Normal vision was maintained, including within the flickering area. After approximately 5 minutes, the flicker waned, and the patient continued skiing without headache, atrial fibrillation, pain, or other physiological abnormalities. The patient subsequently noticed the same flicker phenomenon, mostly when standing during nightly micturition in faintly lit surroundings, however it faded when he covered his eyes, so he was unable to determine if it was binocular or monocular. Flicker episodes were not associated with migraine or headache. A digital simulation of the patient’s description (

Figure 1) was rated as fitting, however it had slightly more contrast than the patient’s flicker. The condition has remained unchanged for 8 years with flicker episodes in weeks or months apart.

Case 2

A 52-year-old woman was referred with blurred vision in left eye, BCVA 1.0 Snellen in both eyes, and applanation tonometry 14 mmHg in both eyes. There was multiple minor extrafoveal pigment epithelium detachments in both eyes and a serous detachment in her left fovea. She was a non-smoker with a year-long history of respiratory insufficiency with coughing and shortness of breath, which was initially interpreted as asthma and treated with oral prednisolone 10 mg to 37.5 mg per day for 10 days and inhaled salbutamol for half a year before pulmonary scintigraphy revealed spontaneously resolved pulmonary embolism. Blood pressure was 148/97 mmHg, and cardiac catheterization showed normal pulmonary artery pressure. The patient was treated with formoterol inhalation, medroxyprogesterone and warfarin which later were switched to dabigatran.

When first seen by us the patient reported years of transparent flicker from her left eye. The flicker was visible with closed eyes. It appeared intermittently in both upper quadrants without any stimulus. Fundus angiography showed bilateral central serous chorioretinopathy, which was treated with verteporfin-photodynamic treatment in the left eye, after which the foveal detachment disappeared. The patient reported bilateral headache with flickering in the periphery of her upper visual field quadrants half a year after her first visit, first intermittently in her left eye, then in her right eye, and then in both eyes, independently of any formal testing. This series of events lasted 1 week. Tangent screen visual fields were normal. Two years later, the patient returned with intermittent flicker in her right eye, resembling sunshine over rippled water surface. The patient’s flicker was like the simulation (

Figure 1), but darker and less noticeable. Flicker appeared every one to four days, sometimes after strenuous exercise or after overnight micturition in dim light. No headache followed. Turning on room light eliminated the flicker. The intermittent, transparent flicker was still present at age 63 years, predominantly in the right eye, in the upper visual field quadrants. The longest flicker was 1 hour. Periodically, the patient had migraine auras with a non-flickering homonymous scotoma of varying sidedness followed by migrainous headache.

Case 3

A 69-year-old woman presented with sudden vision loss in her left eye. She was known with hypercholesterolemia, hypothyroidism, gastric reflux, and asthma and was treated with clopidogrel, rosuvastatin, levothyroxine, salbutamol, salmeterol, fluticasone, and pantoprazole. She had episodes of semitransparent flicker in the central visual field of her left eye with clouding and desaturated colors two and 12 hours after onset, each lasting less than 1 minute. When first seen by a physician 12 hours after onset, BCVA was 0.8/0.3 Snellen, refraction +2.0 spherical in both eyes, and applanation tonometry 15 mmHg. Ultrasound of the carotid arteries was unremarkable. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging showed an old infarct unrelated to visual pathways. Sedimentation rate 8 (2-20 units) and C-reactive protein 2.3 (<10 mg/L) ruled out temporal arteritis. Her right eye had normal fundus photography and optical coherence tomography (OCT), but her left eye had profusely dilated retinal veins and widespread perivenular ischemic hyperreflectivity of the inner and middle retinal layers. On OCT, the inner retina in the lower nasal quadrant of the macula supplied by a cilioretinal artery was hyperreflective from the internal limiting membrane to the inner border of the outer nuclear layer, and the fluorescein angiography revealed delayed filling of the cilioretinal artery. Within two days of onset, a few more flicker episodes occurred, while vision improved spontaneously. After 10 months, BCVA spontaneously recovered to 1.0 Snellen in both eyes. After three and a half years, the left eye had inner retinal thickness deficits inferonasal and superotemporal to the foveal center and automated perimetry showed 30-degree photopic visual field sensitivities 0.7/5.2 dB below the lower reference limit. There was never cystoid macular oedema. At the day of presentation blood sample showed hemoglobin 10.6 (7.3-9.5 mmol/L), leukocytes 11.3 (3.5-8.8 e9/L), thrombocytes 416 (145-390), monocytes 0.94 (0.20-0.80), and neutrophils 7.17 (1.6-5.9), which all became normal half a year later. The condition was interpreted as transient partial ischemic central vein occlusion.

The patient described the flicker simulation (

Figure 1) as a good match to her own in terms of amplitude and transparency, except that her flicker was slower, about 3 Hz, and that what she saw with her left eye during the retinal venous congestion crisis was in greyscale in the middle of the visual field, within a single, vaguely outlined patch that was best seen when she covered her intact right eye. The flickers occurred in bouts under a minute without a known cause. The flicker was less noticeable than the color loss.

Case 4

A 46-year-old man had blurred vision and episodes of flickering in his right inferior hemifield during and after his frequent 10 km jogging. The flicker was especially frequent four weeks before his first visit. He was found to have central retinal venous occlusion without macular oedema in his right eye and hemorrhages in the inferior hemifield. He had had flicker and upper hemicentral retinal vein occlusion without macular oedema in his left eye nine years earlier, during which he also experienced dim flicker. Both venous congestion and flicker disappeared spontaneously with the development of collateral venous drainage on the optic disc. His BCVA was 1.0 Snellen in both eyes, 18/20 mmHg applanation tonometry, normal automated perimetry in the right eye and marginally subnormal in the left eye with lower inferior hemifield sensitivity. The patient did not use any medication. The flicker in his right eye was faster, at 10 Hz, closer to the center of his visual field, and of lower amplitude than the simulation (

Figure 1), but synchronized and uniform across the flickering area. He occasionally saw flickers in his right eye when waking from sleeping in the recumbent position, before and for up to 30 minutes after opening his eyes. Over a year, his right eye had multiple flicker episodes, mostly while jogging, and periodic aggravation of venous congestion and retinal hemorrhage and congestion resolved spontaneously after approximately half a year.

4. Discussion

The four patients (

Table 1) reported episodes of seeing a transparent flickering overlay on part of their binocular visual field. Its sidedness is unknown or inferred from the presence of otherwise symptomatic eye disease. Their mean age was 53.8 years (2 males, 2 females). Visual acuity ranged from 1.25 in both eyes to 0.4 in an eye with unilateral central retinal vein occlusion. Flicker rates ranged from 3 to 10 Hz and were subjectively constant. It lasted minutes to days. Temporal associations included awakening from sleep, exercise, being in dimly lit surroundings, and episodes of retinal venous congestion. Alleviating factors included bright ambient light and reduction in venous congestion. Patients had no history of epilepsy, stroke, or substance abuse. No patient was available for examination during an ongoing flicker event. Flicker rate was uniform among sightings but varied by patient.

Dim flicker after jogging and exercise was experienced by three out of four patients. They had no history, no signs, and no symptoms compatible with multiple sclerosis. The combination of the transparent flicker and no blurring, double vision or other neurological symptoms makes it unlikely that the flicker represented an Uthoff phenomenon [

10]. While two out of four patients had cardiovascular disease, there was no obvious link between these conditions and the flicker.

The dim flicker showed as a pattern of lines or waves or a single patch and did not move in the visual field, unlike visual migraine auras [

7]. Two migraine patients with dim flicker had visual migraine auras with or without migraine and reported their auras were distinctly different from their flicker. Flicker across the vertical midline in two cases suggests anterior optic chiasm origin. Dim flicker is unlikely to be a migraine aura equivalent because it did not have a scotoma, did not move or expand [

11], and did not cause headache [

12]. In contrast to a visual migraine aura, the dim flicker had a regular beat.

Visual migraine aura is the most common type of migraine aura, reported by more than 90% of migraine patients [

7]. It is overwhelmingly of cortical origin, as has been documented by imaging and neurophysiology examinations. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition includes two types of auras with a visual percept, namely visual and retinal aura [

9], (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Visual aura has its origin in the visual cortex [

13], whereas retinal migraine, by definition, has its locus of neurophysiological dysfunction in the retina [

14]. The terminology is ambiguous, however, because it does not make a full distinction between positive sensory disturbances that produce the illusion of seeing something, albeit of an unreal nature, and negative sensory disturbances that subtract or replace visual sensation by illusory filling-in of the scotoma. The classification does not consider that a positive disturbance will be visible in both eyes, regardless of whether it is produced in the visual cortex or the retina of a selected eye, whereas negative disturbances will be felt in both eyes if they are cortical, but only in one eye if they are retinal. An example of a positive percept is the phosphene produced by retinal traction, which will be visible and have the same projection in space, regardless of whether one or both eyes are open or closed. Thus, a luminous percept generated by the visual cortex cannot be distinguished from one generated by the retina [

15]. A blind spot, however, can be assigned specifically to one or the other eye or to the visual cortex by simple visual field examination.

Our patients tended to describe their dim flicker as coming from a specific eye and this concurred with the presence of intraocular disease in two cases. The other two patients had no structural clue that could lead to suspicion of one specific eye being the source of the flicker. There are reports of recurrent acute unilateral retinal vasoconstriction with transient blindness in the affected eye, but it is debatable whether this condition is properly described by the term retinal migraine [

16], since it lacked gradual spreading and subsequent headache, as required by International Headache Society classification of migraine [

9] (

Table 2).

The type of visual experience described by our patients has not, to the best of our knowledge, previously been described as a distinct entity. It may have been interpreted and categorized, though, as migraine aura, a term used very broadly in clinical practice [

17]. A study of migraine patients with aura, where patients could select from various types of modifications of static images that simulated visual migraine aura had an example entitled

“Like looking through heat waves, water or oil” which was described by one patient as

“Experiencing flicker in one eye. May feel like you have tic on your eye. It flutters quickly, and only the bright colors become prominent” and by another patient as

“I constantly see small lines that sort of sprinkle down” [

8]. These descriptions resemble dim flicker. Endogenous flickering associated with external eye pressure, retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, occipital epilepsy, and transient cerebral ischemia [

4], none of which apply to our cases.

Our patients were observed incidentally in a retinal clinic over three years. The small sample size and their disease profiles may be shaped by referral patterns. We recommend that more attention is given to the recording of patients’ visual experiences. Dim flicker may appear benign but warrants a qualified eye exam for posterior segment morbidity. Using an animated simulation is recommended to aid in characterizing flicker and differentiating it from migraine aura.

5. Conclusions

Dim flicker is an episodic recurrent endogenous visual percept without associated headache, discomfort or other symptoms. It is characterized by a rhythmically flickering overlay on an otherwise stable visual field. Awareness of the dim flicker phenomenon may help advance the classification and interpretation of subjective visual disturbances and the identification of underlying disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Dim flicker animated simulation.

Author Contributions

| AUTHOR NAME |

RESEARCH DESIGN |

DATA ACQUISITION AND/OR RESEARCH EXECUTION |

DATA ANALYSIS AND/OR INTERPRETATION |

MANUSCRIPT PREPARATION |

| Abdullah Amini |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Adam Besic |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

| Avery Freund |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

| Yousif Subhi |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Oliver Niels Klefter |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Jes Olesen |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

☒ |

| Jette Frederiksen |

☐ |

☐ |

☐ |

☒ |

| Michael Larsen |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

☒ |

Funding

The study was supported by the Synoptikfonden and the Grosserer Andersens Fond.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics (H-19068888). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its

supplementary material files. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Synoptikfonden and the Grosserer Andersens Fond

Conflicts of Interest

AA: Bayer (Speaker). YS: Bayer, Roche (speaker), WO2020007612A1 (patent). ML: Bayer, Roche (speaker and investigator), Novo Nordisk (consultant), Stoke (consultant and investigator). The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCVA |

Best-corrected visual acuity |

| OCT |

Optical coherence tomography |

References

- Sharpe, C.R. The visibility and fading of thin lines visualized by their controlled movement across the retina. J Physiol. 1972, 222, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehovnik, E.J.; Slocum, W.M.; Carvey, C.E.; Schiller, P.H. Phosphene induction and the generation of saccadic eye movements by striate cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2005, 93, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, T.R.W.; Davie, R.L.; Snead, M.P. Posterior vitreous detachment and retinal tear – a prospective study of community referrals. Eye. 2024, 38, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gishti, O.; van den Nieuwenhof, R.; Verhoekx, J.; van Overdam, K. Symptoms related to posterior vitreous detachment and the risk of developing retinal tears: a systematic review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019, 97, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanski, J.J. Complications of acute posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975, 80, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nüßle, S.; Reinhard, T.; Lübke, J. Acute closed-angle glaucoma. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021, 118, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, A.V.; Ashina, H.; Al-Khazali, H.M.; et al. Clinical features of migraine with aura: a REFORM study. J Headache Pain. 2024, 25, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, M.; Hougaard, A.; Tronvik, E.; et al. Visual migraine aura iconography: A multicentre, cross-sectional study of individuals with migraine with aura. Cephalalgia. 2024, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, J. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohman, T.C.; Davis, S.L.; Beh, S.; Greenberg, B.M.; Remington, G.; Frohman, E.M. Uhthoff’s phenomena in MS--clinical features and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013, 9, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schankin, C.J.; Viana, M.; Goadsby, P.J. Persistent and Repetitive Visual Disturbances in Migraine: A Review. Headache.Blackwell Publishing Inc. 2017, 57, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, D.R.; Dilwali, S.; Friedman, D.I. Current Aura Without Headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018, 22, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjikhani, N.; Sanchez Del Rio, M.; Wu, O.; et al. Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by functional MRI in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, D. Retinal migraine. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 1970, 10, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, I.D.; Palmisano, S.; Croft, R.J. Retinal and Cortical Contributions to Phosphenes During Transcranial Electrical Current Stimulation. Bioelectromagnetics. 2021, 42, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, E.; Vote, B.J.; Cosswell, A.G. Retinal migraine: Caught in the act [2]. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2004, 88, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.L.; Daroff, R.B.; Ducros, A.; Newman, N.J.; Biousse, V. Most Cases Labeled as “Retinal Migraine” Are Not Migraine. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2007, 27, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).