Introduction

The insights of those receiving medical attention are being progressively recognized as a fundamental component of healthcare excellence, which entails not merely the clinical results but also the human, structural, and contextual elements that impact the interpretation of care(Pines, 2025).(1) While medical interventions and clinical therapies are critically essential, non-clinical factors—such as proficient communication, administrative support, facility hygiene, waiting time duration, and interactions with reception or clerical staff—substantially affect patient satisfaction and overall well-being (Godovykh & Pizam, 2023).(2) This extensive viewpoint denotes a shift in health systems and policy-makers towards more holistic care models, in which the patient’s subjective experience is esteemed as being of equal significance to traditional clinical indicators (de Oliveira Lima et al., 2025).(3)

In earlier times, initiatives designed to uplift healthcare quality have predominantly emphasized clinical performance statistics: the correctness of diagnoses, the effectiveness of treatment techniques, safety measures for patients, and adherence to evidence-supported practices (Moore et al., 2015).(4) However, as the clock has ticked on, the scale of these undertakings has increased notably. For example, several decades prior, quality frameworks such as Donabedian’s structure-process-outcome model commenced the incorporation of elements pertaining to patient perception (Guzmán-Leguel & Rodríguez-Lara, 2025; Chen et al., 2024).(5, 6) In more recent developments, guidelines established in the United Kingdom, notably the 2021 NICE guidance for adult NHS services, explicitly recognize the significant impact of non-clinical personnel—including receptionists, clerical staff, and domestic workers—on shaping patient experience (NICE, 2012/2021).(7) Simultaneously, investigations conducted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic have recorded a deterioration in patient experience metrics—not exclusively within the realm of clinical care—but also in the domains of responsiveness and environmental/staff interactions (e.g., hygiene standards, staff accessibility), particularly in healthcare institutions characterized by insufficient staffing levels. These advancements have transformed the discourse from a focus on “what interventions are administered” to an inquiry into “how care is provided” and “with whom the patient engages”—both in clinical and non-clinical contexts.

In present debates, this issue stays quite crucial owing to several intertwined challenges. Firstly, the anticipations of patients are on an upward trajectory: individuals now demand not solely safe and efficacious medical treatment, but also a level of service that is characterized by respectfulness, efficiency, empathy, and seamlessness (Duplantier & Undem, 2025).(8) Second, Healthcare systems in the present day are battling substantial troubles: concerns over staffing, bureaucratic impediments, financial limitations, and variances in non-clinical support are generating increased patient discontent. Feedback shows that a majority of individuals feel pleased with their healthcare practitioners, including both physicians and nursing teams. Many people have expressed concerns about long wait times, complicated paperwork, and a shortage of info when leaving the hospital (Karume et al., 2025).(9) (Care Quality Commission) Third, there is an expanding volume of evidence indicating that lacking non-clinical interactions may unfavorably impact clinical results indirectly—by diminishing trust, escalating stress levels, and reducing compliance with treatment protocols that have been prescribed (Laferton et al., 2025).(10) Fourth, and of notable significance, the regulatory and policy framework is increasingly placing emphasis on the patient experience (including patient participation and the assimilation of experiential data in regulatory reviews, among others) as an essential aspect of healthcare quality.

In light of this contextual foundation, an analytical investigation into the manner in which both clinical and non-clinical factors collaboratively influence the patient experience is particularly pertinent at this juncture (Buchanan et al., 2025).(11) This inquiry will study various important concepts: (a) the ways in which non-clinical occupations (including administrative, reception, clerical, and domestic/support teams) relate to clinical tasks during patient sessions; (b) domains of the patient experience wherein non-clinical factors exert the most substantial impact (e.g., interpersonal communication, duration of waiting periods, physical environment, levels of empathy); (c) contemporary empirical findings (within the last five years) elucidate the relationship between non-clinical determinants and patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment protocols, trust in healthcare providers, and clinical outcomes (Buchanan et al., 2025). (d) obstacles and impediments in the incorporation of non-clinical personnel into quality enhancement and evaluative frameworks; and (e) put forth ideas (learning frameworks, evaluative response systems, policy tweaks or administrative transformations) to elevate non-clinical contributions.

This narrative review tries to give a complete view of what clinical and non-clinical things affect how patients feel. It points out holes in the current studies, mainly about non-clinical jobs, and suggests a thinking model with hands-on advice (Tingyu et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2025; Amjad et al., 2025; Veillard et al., 2025).(12-15) This article aims to broaden the discussion on patient experience by pointing out areas that have not gotten much attention. It also seeks to provide a base for future studies and policies that involve all people who care for the patient.

Conceptual and Theoretical Background

The patient experience includes all interactions that patients have with the health system, which includes direct clinical care, non-clinical interactions with staff, administrative processes, and the environment. This field focuses on a few main ideas: care that puts the patient first, which means being respectful, understanding, and responsive to what each patient wants and values; how happy patients are, which is about how they feel about the care they get; and how well patients stick to their treatment, which is usually impacted by how good their experience is (Alhuseini et al., 2025).(16) The idea of non-clinical roles—including receptionists, administrative staff, billing personnel, and other support positions—has attracted notice lately. This shows that a healthcare team involves more than just doctors and nurses.

Several theories exist to help understand what patients go through. The structure–process–outcome (SPO) model from Donabedian has been a key tool for judging healthcare quality for a while (De Rosis, 2024).(17) It shows how things like staffing and facilities are related to the way care is given through. This development, accordingly, modifies various elements like the impact on patient outcomes, the extent of patient satisfaction, and the commitment to followed treatment courses. Recent work has broadened the application of the SPO framework beyond just clinical processes. These studies include non-clinical staff interactions as part of the process dimension, acknowledging that they have an indirect but real impact on how patients do (Al-Abri & Al-Balushi, 2014).(18) Patient-centered care models, like the Institute of Medicine’s six quality dimensions (safety, how well it works, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and fairness), also show how important communication, respect, and quick responses are. Clinical and non-clinical staff usually influence these things (De Rosis, 2024).(17) Together, these models give us a way to understand that patient experience in today’s health care is complicated and everything is connected (Guzmán-Leguel & Rodríguez-Lara, 2025).(5)

In recent times, experience-based co-design (EBCD) frameworks have been utilized to investigate the manner in which patients comprehend and engage with the healthcare milieu, encompassing the contributions of non-clinical personnel (Macdonald et al., 2023).(19) Studies suggest that using patient feedback about administrative and support services in projects to improve quality can raise patient satisfaction and how much empathy they feel is shown (Fylan et al., 2021).(20) Studies suggest that using patient input on admin and support services in quality improvement may raise patient satisfaction and feelings of being understood.

From a conceptual point, these models agree that patient experience has many dimensions. These dimensions have related parts in medical, support, and place-related areas. This perspective has been strengthened, or complemented, by more recent perspectives in health informatics that claim real-time feedback systems and digital patient experience monitoring can facilitate engagement and synthesizing of the contributions from all team members in the groups’ effort to implement continuous quality improvement (Yu et al., 2025).(13) These frameworks give us a way to think about all the ways patients and healthcare workers interact. They provide a starting point for creating models that combine clinical and non-clinical factors that affect a patient’s experience (Remer et al., 2024).(21)

Historical Development and Evolution

How we think about patient experience has changed a lot in recent decades. Initial approaches to healthcare quality were mainly about clinical results and technical skill, stressing how well medical treatments worked and how safe they were. Donabedian’s structure–process–outcome framework, among other important works, came out of the 1960s and 1970s. Early ideas about healthcare quality often focused on clinical results and technical skill, stressing how well medical treatments worked and how safe they were. During the 1960s and 1970s, influential studies, for example, Donabedian’s (1966) structure–process–outcome framework, established important groundwork for systematic assessment of quality in healthcare, representing one of the first fully articulated models linking organizational structures, process of care and health outcomes in health systems (Donabedian, 1966; Berwick & Fox, 2016).(22, 23) In many fewer wealthy nations, the views of patients are often considered less important than clinical evaluations. This is partly because of limited resources, poorly organized administrative systems, and a lack of standard ways to report patient experiences. Also, the input of non-clinical staff is not well-recognized in research or practice (Moor et al., 2015).(4)

In the 1980s and 1990s, health service researchers started to see patient-centered care as more important. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) said that focusing on the patient was a key part of good care, arguing that healthcare should consider what patients want, need, and value (Edgman-Levitan & Schoenbaum, 2021).(24) During this time, methods for assessing patient satisfaction came about. Still, they mostly looked at how patients interacted with doctors and nurses (Jenkra et al., 2023).(25) Even though some stories suggested that administrative and support staff could impact how patients viewed the quality of their care, these workers were often seen as less important (Tzelepis et al., 2015).(26)

In the early 2000s, the conversation around quality in healthcare started to expand and took into account the systemic and interpersonal aspects of patient experience. Several important policy documents, such as the NHS National Service Frameworks in the UK (1999–2004), made clear that patient experience depends on the whole care process and all staff members. This includes receptionists and administrative staff who affect access, communication, and continuous care. During this time, research on patient experience grew, and there was more proof that even short interactions can change how happy patients are, how well they follow their treatment plans, and what they think of the service quality. Still, a lot of this work kept paying attention to interactions between doctors and patients, so the roles of non-clinical staff were not studied as closely.

In the last ten years, healthcare has started to see patient experience as something that can be measured, helped by the common use of digital feedback tools. Evidence from 2020 to 2024 shows that non-clinical staff, like administrative people, receptionists, and billing staff, can really change how patients feel, how much they trust the process, and how involved they are in their care (Berry et al., 2018; Schiaffino et al., 2019; Surani et al., 2022).(27-29) In hospital settings, teams use real-time feedback to find flaws in how they handle administrative tasks, which helps them improve patient happiness faster. Moreover, digital health technologies have been demonstrated to augment the function of non-clinical services across diverse contexts by improving workflow transparency and facilitating communication between patients and staff (Ahmed et al., 2025; Dodson et al., 2024).(30, 31) The COVID-19 pandemic made these problems clearer since limited resources and increased work stress showed flaws in support tasks, which hurt patients’ experience (Wong et al., 2023; Chemali et al., 2022).(32, 33)

In conclusion, the study of patient experience has changed over time. It started with a focus on clinical results but grew to include many areas. Now, the work of all healthcare workers, not just doctors and nurses, is seen as important. This change shows a growing awareness that to really improve a patient’s experience, we need to focus on their daily interactions with the care setting, as well as medical treatments.

Current Trends and Key Issues

Recently, some key patterns came up in how patients feel about their healthcare. These patterns show we’re thinking about patient experience in a wider way, and that there are fresh ideas in how healthcare is provided.

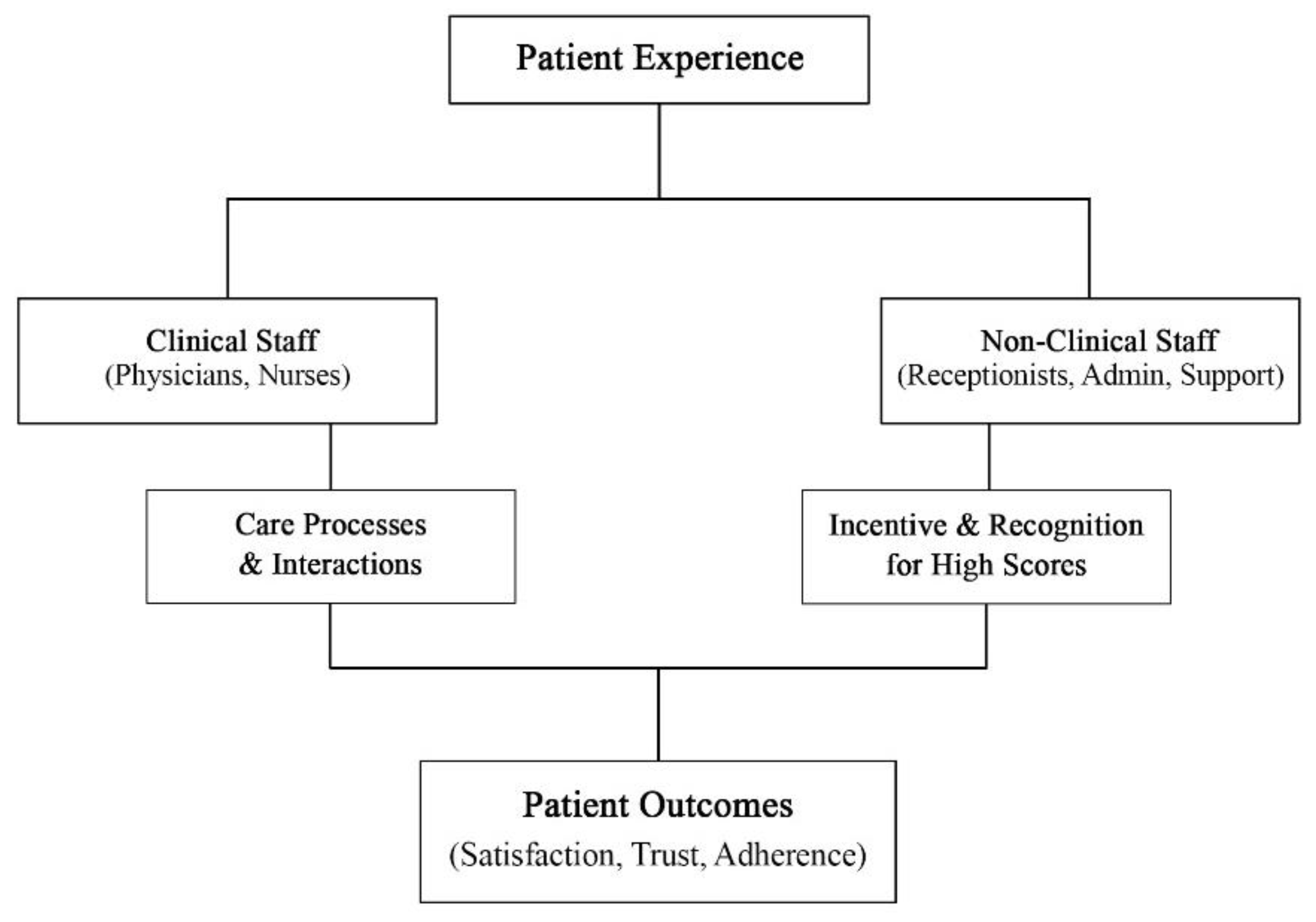

Firstly, there is an increasing acknowledgment that non-clinical personnel significantly influence patients’ perceptions regarding the quality of care received. Hospitals and clinics are noticing that when patients talk to receptionists, staff, and support people, it impacts how much they trust the medical center, how pleased they are with the service, and how well they follow their treatment plans. As demonstrated in

Figure 1, the contributions of non-clinical individuals are critical and they substantially alter many parts of the patient experience. An expanding corpus of empirical research elucidates that even transient encounters with non-clinical personnel, including receptionists and administrative staff, can profoundly affect patients’ assessments of care quality, confidence in the healthcare provider, and involvement in the treatment process (Locock et al., 2020; Willer et al., 2023; Jones et al., 2021).(34-36)

Secondly, the amalgamation of technological advancements and digital evaluative frameworks has emerged as a salient trend. Timely patient satisfaction reviews, mobile technology, and electronic kiosks streamline the instant reporting of patient experiences, facilitating healthcare staff in swiftly recognizing areas that need betterment. These devices document not merely the evaluations associated with clinical activities but also highlight other crucial areas, such as wait times, exchanges with administrative teams, and the smoothness of operational processes (Gentili et al., 2022; Dodson et al., 2024).(31, 37)

Third, healthcare is shifting to holistic, patient-centered care. In this model, the care environment, clear communication, and empathy are as important as medical interventions. Current discourse acknowledges the complexity of a patient’s experience, including their emotional, psychological, and social well-being. These are greatly impacted by staff outside of doctors and nurses and also the setting. Recent healthcare rules and guidelines support this move, asking for regular reviews of patient opinions from everyone on the care staff (Berry et al., 2018; Gates et al., 2022).(27, 38)

Although healthcare professionals and nursing staff frequently engage in organized training focused on patient-centered conversations, the front desk employees and administrative staff may miss out on equivalent formal education, resulting in varied patient experiences (Locock et al., 2020; Jesus et al., 2025).(34, 39) Lastly, the addition of non-clinical commentary into initiatives aimed at enhancing quality brings forth both logistical and ethical intricacies, especially in terms of anonymity, equity, and potential biases in patient evaluations (Hunt et al., 2021). (40)The COVID-19 pandemic accentuated these vulnerabilities, as limitations in resources, deficiencies in personnel, and increased operational demands exacerbated stress levels and reduced the ability for optimal patient engagements (Lee et al., 2025).(41)

A further contemporary discourse pertains to the equilibrium between the assessment of performance and the integration of ethical considerations. Patient responses are vital for optimizing rewards, advancing training initiatives, and upholding accountability. Yet, placing too much importance on patient evaluations might yield skewed results, primarily impacting staff whose duties are confined by their roles (Al-Abri & Al-Balushi, 2014; Richman & Schulman, 2022).(18, 42)

In short, prevalent movements stress the detailed and composite traits of patient experiences, clarifying the pivotal significance of both medical and supportive aspects. Current problems suggest chances for progress through structured training, feedback systems, and policy changes. They also show issues with fairness, ethics, and how well things can be put into practice. Dealing with these concerns is key to improving patient-centered healthcare. A healthcare system that puts patients first must understand all the things that the patients’ happiness, confidence, and health depend on.

Applications and Practical Implications

Recent studies on patient experience offer important ideas for healthcare practice, policy, and how organizations are run. A notable application involves the incorporation of non-clinical personnel into quality enhancement initiatives. Healthcare institutions and outpatient facilities are progressively acknowledging that enhancing patient engagement extends beyond the roles of physicians and nursing staff; administrative personnel, receptionists, and auxiliary staff play a crucial role in shaping patients’ perceptions of the quality of care received (Locock et al., 2022; Coles et al., 2020).(34, 43) Real-world strategies feature targeted training sessions, engaging workshops, and structured frameworks aimed at boosting interpersonal abilities and responsiveness, which in turn promote better patient satisfaction and trust (Hunt et al., 2021).(40) For example, contemporary initiatives within Australian outpatient facilities have integrated systematic training programs for reception and administrative personnel, culminating in quantifiable enhancements in patient satisfaction metrics and compliance with subsequent care protocols (Jones et al., 2021).(36)

An additional application is found in the domain of real-time feedback mechanisms and technological advancements. Contemporary mobile applications, web-based surveys, and kiosk-oriented platforms now facilitate patients in the immediate reporting of their experiences, encompassing both clinical and non-clinical engagements. These systems empower healthcare administrators to discern both the strengths and deficiencies in staff performance, observe trends longitudinally, and expeditiously execute corrective measures. Through the methodical acquisition of patient insights regarding administrative services, healthcare institutions are enabled to optimize resource allocation, improve procedural efficiencies, and elevate overall operational effectiveness (Dodson et al., 2024; Canfell et al., 2024; Toh et al., 2023; Snowdon et al., 2024).(31, 44-46)

The process of policy formulation and the governance of organizations gain significant advantages from these revelations. Regulatory bodies and accreditation institutions are steadily enforcing that healthcare personnel collect and apply patient experience insights, thereby extending the focus from only clinical outcomes to also integrate both interpersonal and organizational facets (Snowdon et al., 2024; Bertelsen et al., 2025).(46, 47) This comprehensive viewpoint significantly influences strategic planning, resource distribution, and personnel development, cultivating an atmosphere in which patient-centered care is integrated across all tiers of the organization (Mitchell & Hall, 2023).(48)

Ultimately, the influence of prioritizing non-clinical insights in the community is strikingly substantial. Engaging favorably with support and administrative staff not just boosts patient contentment but also eases pressure, strengthens involvement, and indirectly impacts health outcomes (Jesus et al., 2025; Locock et al., 2022).(34, 39) When health organizations see these roles as key to patient care, they can build a culture of empathy and constant progress. Also, when we add these ideas to education for health staff, both clinical and non-clinical people will start their careers knowing how important complete, team-based patient care is.

In conclusion, patient experience research has useful applications in several areas. These areas include staff training, using digital feedback, policy creation, and changing the culture within health organizations (Dodson et al., 2024; Snowdon et al., 2024).(31, 46) By looking at both clinical and non-clinical factors, groups can raise patient satisfaction, build stronger trust, and improve how well care is given.

Critical Reflections and Gaps in the Literature

Despite the growing emphasis on the patient experience as a complex entity, the existing literature uncovers notable gaps and elements that still require further exploration. A notable advantage of today’s research is the insight that patient experiences reach further than just the medical appointments, incorporating numerous environmental, structural, and interpersonal influences. A multitude of studies carried out in the last five years has emphasized the vital contributions of administrative and non-clinical personnel in affecting satisfaction, trust, and conformity to care protocols (Locock et al., 2022; Bragge et al., 2025).(34, 49) This is a contribution that forces one to consider care delivery as more than an exclusive clinical process, but rather as a team-based process.

However, gaps remain. Studies often underplay the role of non-clinical staff. Although there’s a lot of focus on medical doctors and nursing professionals, the effect of administrative receptionists, clerical teams, and auxiliary staff on the health outcomes of patients isn’t adequately measured or conceptualized. For example, research endeavors that acknowledge non-clinical functions frequently concentrate on isolated interactions, such as the scheduling of appointments or the processing of billing, rather than investigating their overarching, cumulative influence on patient experience and involvement (Willer et al., 2023; Leotin, 2025; Bertelsen et al., 2025).(35, 47, 50)

A further limitation concerns the geographical distribution of existing research on patient experience and staff contributions. The majority of empirical studies originate from high-income countries—most notably the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia—where healthcare systems tend to have more standardized administrative structures and stronger digital infrastructures (Livieri et al., 2025; Goodyear-Smith et al., 2019).(51, 52) By contrast, evidence from low- and middle-income countries remains markedly limited, despite the fact that systemic constraints in these settings may amplify the influence of non-clinical staff on patient pathways (Sharma et al., 2023; Shash et al., 2025).(53, 54) Patients in resource-constrained systems often encounter complex bureaucratic procedures, extended waiting times, and fragmented communication channels, all of which position administrative and support personnel as critical intermediaries in shaping the overall care experience. The absence of robust data from these regions restricts the global applicability of current models and underscores the need for comparative, context-sensitive research to better capture these dynamics.

Second, research seldom addresses cultural differences. Studies mainly take place in rich countries. Because of this, findings might not apply to other places, like poorer countries, where staff might greatly affect patient care. For example, variations in hierarchical frameworks, personnel standards, and patient anticipations across different geographical areas may influence the manner in which non-clinical contributions impact satisfaction and trust; however, comparative investigations continue to be limited in number (Sharma et al., 2023; Goodyear-Smith et al., 2019; Cipta et al., 2024).(52, 53, 55)

Moreover, we find a deficiency in extensive theoretical structures that combine clinical and non-clinical influences into a singular design. In spite of the construction of theoretical frameworks, such as Donabedian’s structure–process–outcome model and paradigms concentrated on patient care, there exists a marked shortfall in research that clearly articulates the relationships between clinical and non-clinical roles, or recommends mechanisms by which these relationships facilitate improved outcomes. Present initiatives designed to use digital feedback or patient experience information for quality improvement are commonly fragmented and inadequately address non-clinical influences (Tossaint-Schoenmakers et al., 2021; De Rosis, 2024; Moayed et al., 2022).(17, 56, 57)

In summary, the ethical and operational considerations surrounding patient feedback strategies continue to lack thorough investigation. While real-time assessments and evaluation mechanisms yield pragmatic insights, there exists a paucity of discourse regarding the equity, confidentiality, and possible unforeseen repercussions for non-clinical personnel. The existing body of literature demonstrates a deficiency in comprehensive directives regarding the equilibrium of accountability, educational initiatives, and performance-based incentives, all while circumventing detrimental or prejudiced results.

In conclusion, although the discipline has come far in recognizing that patient experience has many dimensions, key areas still require work. These include the study of non-clinical roles, applicability across different situations, combined conceptual models, and moral implementation of feedback systems. Confronting these inequalities will be essential in crafting integrated solutions aimed at bettering patient interactions and outcomes throughout the entire healthcare landscape (Jesus et al., 2025; Locock et al., 2022).(34, 39)

Future Directions and Recommendations

By enhancing our understanding of the patient journey, various avenues for future research and effective methodologies are revealed, particularly highlighting the participation of non-medical team members in patient-centered care strategies. One unequivocal course of action involves the formulation and implementation of organized training initiatives tailored for administrative and support staff. In spite of healthcare practitioners regularly attending organized courses for interacting with patients with empathy, those not in medical professions typically miss similar opportunities for growth. Specialized workshops, position-oriented protocols, and engaging training frameworks have the potential to augment interpersonal competencies, elevate responsiveness, and promote uniformity in patient engagements (Locock et al., 2022; Jesus et al., 2025).(34, 39) Through a systematic examination of the knowledge and skill deficiencies prevalent among non-clinical personnel, healthcare institutions can ascertain that every patient interaction serves to enhance the overall experience and foster trust.

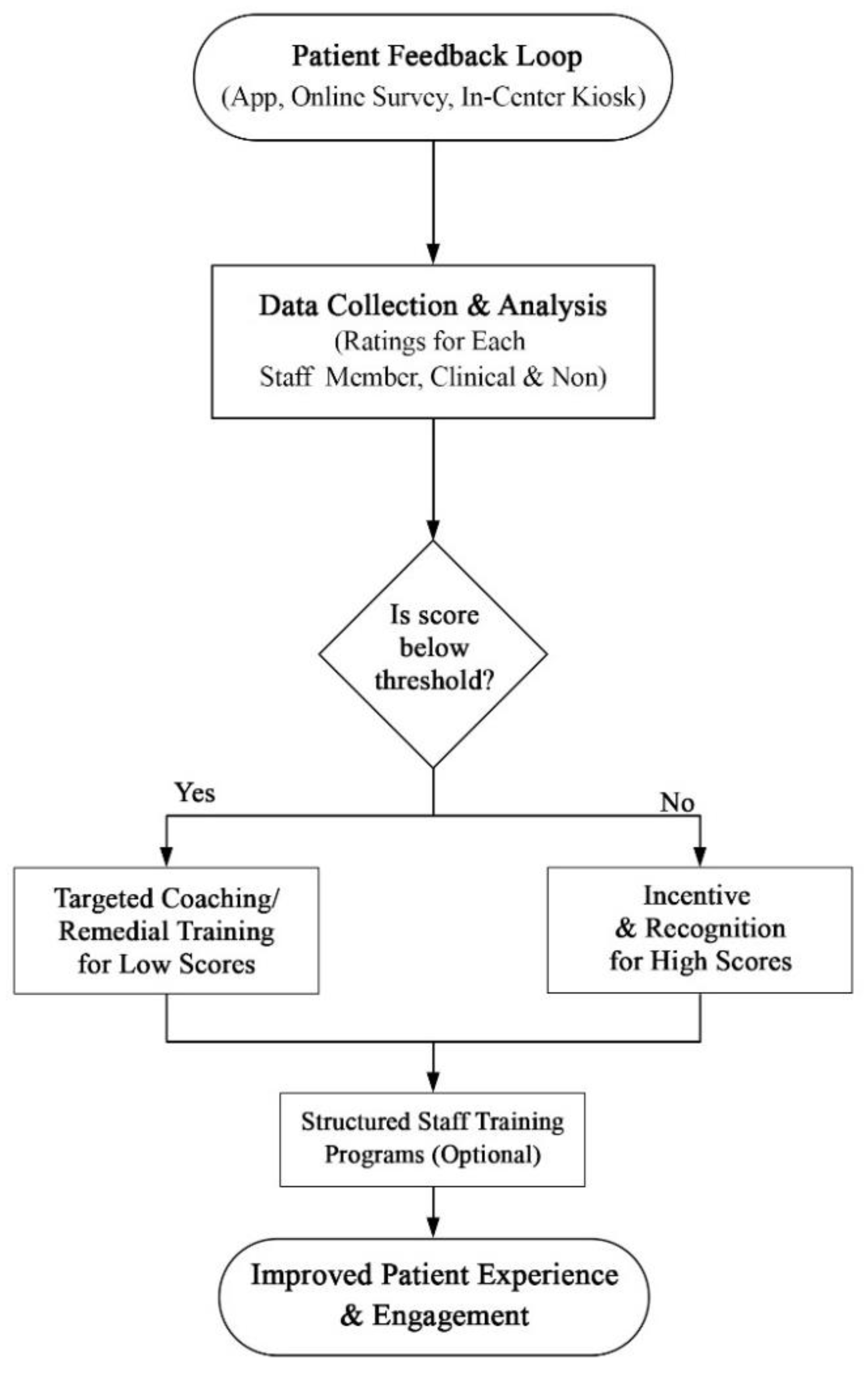

Another auspicious domain pertains to digital methodologies and instantaneous feedback systems. Mobile applications, internet-based surveys, and on-site kiosks facilitate patients in furnishing prompt evaluations regarding their encounters with both clinical and non-clinical personnel. These systems possess the capability to elicit detailed, personalized insights regarding service quality, thereby allowing administrators to observe trends, discern strengths and weaknesses, and execute adaptive enhancements (Dodson et al., 2024; Snowdon et al., 2024).(31, 46) The adoption of these devices in everyday clinical routines not just encourages persistent advancements in quality but also brings to light aspects of patient experience that were once ignored, covering administrative effectiveness, clarity of dialogue, and environmental factors.

In conjunction with these methodologies are structures of incentives and accountability. Empirical evidence suggests that the association of patient feedback with positive reinforcement, recognition programs, or avenues for professional growth can significantly enhance personnel motivation to maintain high levels of engagement (Richman & Schulman, 2022; Lloyd et al., 2023).(42, 58) On the other hand, if scores stay low, coaching or help might be needed to make sure everyone meets the basic goals. It’s important that these plans are fair, open, and ethical. This will keep unwanted harm or unfair punishment from happening to those not involved in medical care (Hunt et al., 2021).(40)

In an academic context, there is an essential requirement for empirical research and theoretical designs that fuse together clinical aspects and external factors shaping the patient experience. Future investigations should delve into how interactions outside the parameters of treatment can shape patient trust, compliance with guidance, and overall results. It should also look at how things like culture, organization, and rules change those things. Comparing different cultures could show how context changes the impact of non-clinical staff. This could guide interventions in different health systems (Goodyear-Smith et al., 2019; Cipta et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2023).(52, 53, 55)

In summary, enhancing the patient experience demands a varied strategy that merges educational programs, tech innovations, reward systems, and rigorous empirical research. Healthcare systems hold the power to craft more successful and enduring tactics designed to enhance patient satisfaction, trust, and engagement by reflecting on both clinical and non-clinical aspects. This will eventually improve the quality and success of their care.

Incentives and accountability systems go hand in hand with these plans. Research shows that connecting patient input to rewards or focused mentoring can push workers to keep up good interaction standards (Lloyd et al., 2023).(58) As shown in

Figure 2, the input system lets patients quickly grade how staff members act, which helps guide focused teaching and performance handling steps.

Table 1 gives a summary of the main things related to patient experience that were talked about in this paper. It shows how clinical and non-clinical workers, processes, feedback and results are related. The table mixes data from current work, points out real-world uses, and goes with the idea (

Figure 1) and how-to (

Figure 2) models shown before.

Conclusion

Table 1 shows that both kinds of interactions are important for patients. This review says that patient experience has many parts. It depends on medical and non-medical staff, office work, and where the patient is. By studying ideas, history, what’s going on now, and how they are used, it’s clear that patient care is greater than just dealing with illness. It also means taking care of all interactions inside the system.

This analysis adds to what we know by bringing together clinical and non-clinical views. It gives a way to see how different parts of the patient’s experience relate to each other. It shares ways to make things better, like training staff, getting feedback as it happens, and using rewards (Locock et al., 2022; Jesus et al., 2025).(34, 39) By looking at areas not explored well, like how non-clinical staff affect things and what digital feedback can do, this work suggests areas for study and putting ideas into practice.

In conclusion, considering feedback from all healthcare personnel is vital for better patient care.

In summary, recognizing and including input from all healthcare staff, both clinical and non-clinical, is very important for improving patient-centered care. Linking what we know with real actions can lead to bigger and lasting improvements in how patients feel, which can lead to better health and greater trust in healthcare (Bragge et al., 2025).(49)

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Pines, R. Insights on the Future Priorities of Patient Experience Research as Care Experience Research. J. Patient Exp. 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Godovykh M, Pizam A. Measuring patient experience in healthcare. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2023;112:103405.

- Lima, H.d.O.; Carvalho, G.R.; Nogueira, R.; Campello, V.B.; de Araújo, A.C.L.F.; de Souza, Á.N.; Stuchi, B.P.; Torres, V.d.M.; Simões, D.; da Silva, L.M. Perspectives on Patient Experience: Findings from Healthcare Providers in a Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study Within a Healthcare Network in Brazil. J. Patient Exp. 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Moore L, Lavoie A, Bourgeois G, Lapointe J. Donabedian’s structure-process-outcome quality of care model: validation in an integrated trauma system. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2015;78(6):1168–75.

- Guzmán-Leguel, Y.M.; Rodríguez-Lara, S.Q. Assessment of Patients’ Quality of Care in Healthcare Systems: A Comprehensive Narrative Literature Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1714. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Hsiao, C.-T.; Chang, D.-S.; Lai, W.-C. The Delivery Model of Perceived Medical Service Quality Based on Donabedian's Framework. J. Heal. Qual. 2024, 46, 150–159. [CrossRef]

- UK NCGC. Patient Experience in Adult NHS Services: Improving the Experience of Care for People Using Adult NHS Services: Patient Experience in Generic Terms. 2012.

- Duplantier, S.C.; Undem, T. Patient Expectations: A Qualitative Study on What Patients Want From Their Healthcare Providers to Support Them in Healthy Aging. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Karume, A.K.; Nyongesa, K.; Okutoyi, L.; Kinuthia, J. Patient’s expectations and perceptions on quality of care; An evaluation using SERVQUAL gap in Kenya. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0315910. [CrossRef]

- Laferton JA, Rief W, Shedden-Mora M. Improving Patients’ Treatment Expectations. JAMA. 2025.

- Buchanan, S.; Cronin, S.; St-Amant, A.; Fitzsimon, J. Evaluating Patient Experience with Integrated Virtual Care (IVC), a Hybrid Primary Care Model in Rural Ontario, Canada: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Prim. Care Community Heal. 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Tingyu G, Xiao C, Junfei L. Factors influencing patient experience in hospital wards: a systematic review. 2024.

- Yu, X.; Huang, H.; Lin, K.; Wang, H.; Zheng, S.; Ran, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H. Exploring the Determinants of Patient Experiences Using the Digital Topic Modeling Approach. J. Nurs. Manag. 2025, 2025, 8183250. [CrossRef]

- Amjad, A.; Nisa, Z.; Khan, S.J.; Sethi, S.S.; Ghafoor, A.; Iqbal, A.; Shahzad, F.; Riaz, M.; Ghori, U.; Almas, A. Factors Associated With Patient Experience From 2 Tertiary Care Hospitals—A Cross-Sectional Study From Karachi, Pakistan. J. Patient Exp. 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Veillard, D.; Baumstarck, K.; Ousmen, A.; Hamonic, S.; Edan, G.; Auquier, P. Determinants of the experience of patients living with multiple sclerosis in terms of care pathway quality: An original French study. Rev. Neurol. 2025, 181, 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Alhuseini, M.; Aljabri, D.; Althumairi, A.; Al Saffer, Q. Navigating the patient experience in primary healthcare clinics in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia: a secondary analysis study. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1607267. [CrossRef]

- De Rosis S. Performance measurement and user-centeredness in the healthcare sector: Opening the black box adapting the framework of Donabedian. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2024;39(4):1172–82.

- Al-Abri, R.; Al-Balushi, A. Patient Satisfaction Survey as a Tool Towards Quality Improvement. Oman Med J. 2014, 29, 3–7. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, A.; Kuberska, K.; Stockley, N.; Fitzsimons, B. Using experience-based co-design (EBCD) to develop high-level design principles for a visual identification system for people with dementia in acute hospital ward settings. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069352. [CrossRef]

- Fylan, B.; Tomlinson, J.; Raynor, D.K.; Silcock, J. Using experience-based co-design with patients, carers and healthcare professionals to develop theory-based interventions for safer medicines use. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 2127–2135. [CrossRef]

- Remer, L.M.; Line, K.; Paolella, A.; Rozniak, J.M.; A Alessandrini, E. Use of Daily Web-Based, Real-Time Feedback to Improve Patient and Family Experience. J. Patient Exp. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. The Milbank memorial fund quarterly. 1966;44(3):166–206.

- Berwick D, Fox DM. “Evaluating the quality of medical care”: Donabedian’s classic article 50 years later. The Milbank Quarterly. 2016;94(2):237.

- Edgman-Levitan, S.; Schoenbaum, S.C. Patient-centered care: achieving higher quality by designing care through the patient’s eyes. Isr. J. Heal. Policy Res. 2021, 10, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Janerka, C.; Leslie, G.D.; Gill, F.J. Development of patient-centred care in acute hospital settings: A meta-narrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 140, 104465. [CrossRef]

- Tzelepis, F.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Zucca, A.; Fradgley, E. Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: Why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2015, 2015, 831–835. [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Deming, K.A.; Danaher, T.S. Improving Nonclinical and Clinical-Support Services: Lessons From Oncology. Mayo Clin. Proceedings: Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 2, 207–217. [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, M.K.; Suzuki, Y.; Ho, T.; Finlayson, T.L.; Harman, J.S. Associations Between Nonclinical Services and Patient-Experience Outcomes in US Acute Care Hospitals. J. Patient Exp. 2019, 7, 1086–1093. [CrossRef]

- Surani, A.; Hammad, M.; Agarwal, N.; Segon, A. The Impact of Dynamic Real-Time Feedback on Patient Satisfaction Scores. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 38, 361–365. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Okesanya, O.J.; Olaleke, N.O.; Adigun, O.A.; Adebayo, U.O.; Oso, T.A.; Eshun, G.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. Integrating Digital Health Innovations to Achieve Universal Health Coverage: Promoting Health Outcomes and Quality Through Global Public Health Equity. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1060. [CrossRef]

- Dodson, P.; Haase, A.M.; Jeffreys, M.; Hales, C. Capturing patient experiences of care with digital technology to improve service delivery and quality of care: A scoping review. Digit. Heal. 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wong EL-y, Wang K, Cheung AW-l, Graham C, Yeoh E-k. Thinking beyond the virus: perspective of patients on the quality of hospital care before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;11:1152054.

- Chemali, S.; Mari-Sáez, A.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Weishaar, H. Health care workers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Hum. Resour. Heal. 2022, 20, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Locock, L.; Graham, C.; King, J.; Parkin, S.; Chisholm, A.; Montgomery, C.; Gibbons, E.; Ainley, E.; Bostock, J.; Gager, M.; et al. Understanding how front-line staff use patient experience data for service improvement: an exploratory case study evaluation. Heal. Serv. Deliv. Res. 2020, 8, 1–170. [CrossRef]

- Willer, F.; Chua, D.; Ball, L. Patient aggression towards receptionists in general practice: a systematic review. Fam. Med. Community Heal. 2023, 11, e002171. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.H.; Woods, J.; Brusco, N.K.; Sullivan, N.; Morris, M.E. Implementation of the Australian Hospital Patient Experience Question Set (AHPEQS): a consumer-driven patient survey. Aust. Heal. Rev. 2021, 45, 562–569. [CrossRef]

- Gentili, A.; Failla, G.; Melnyk, A.; Puleo, V.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Ricciardi, W.; Cascini, F. The cost-effectiveness of digital health interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 787135. [CrossRef]

- Gates, M.; Gates, A.; Pieper, D.; Fernandes, R.M.; Tricco, A.C.; Moher, D.; E Brennan, S.; Li, T.; Pollock, M.; Lunny, C.; et al. Reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions: development of the PRIOR statement. BMJ 2022, 378, e070849. [CrossRef]

- Jesus, T.S.; Lee, D.; Zhang, M.; Stern, B.Z.; Struhar, J.; Heinemann, A.W.; Jordan, N.; Deutsch, A. Organizational and Service Management Interventions for Improving the Patient Experience With Care: Systematic Review of the Effectiveness. Int. J. Heal. Plan. Manag. 2025, 40, 883–895. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, D.F.; Dunn, M.; Harrison, G.; Bailey, J. Ethical considerations in quality improvement: key questions and a practical guide. BMJ Open Qual. 2021, 10, e001497. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.E.C.; Ling, M.; Boyd, L.; Olsson, C.A.; Harvey, H.M.L.; Sheen, J. Three years of pandemic stress and staffing challenges: a retrospective qualitative study of COVID-19 impacts on frontline healthcare workers’ mental health and wellbeing. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Richman, B.D.; Schulman, K.A. Are Patient Satisfaction Instruments Harming Both Patients and Physicians?. JAMA 2022, 328, 2209–2210. [CrossRef]

- Coles, E.; Wells, M.; Maxwell, M.; Harris, F.M.; Anderson, J.; Gray, N.M.; Milner, G.; MacGillivray, S. The influence of contextual factors on healthcare quality improvement initiatives: what works, for whom and in what setting? Protocol for a realist review. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Canfell, O.J.; Woods, L.; Meshkat, Y.; Krivit, J.; Gunashanhar, B.; Slade, C.; Burton-Jones, A.; Sullivan, C. The Impact of Digital Hospitals on Patient and Clinician Experience: Systematic Review and Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. J. Med Internet Res. 2024, 26, e47715. [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.H.Y.; Lee, S.C.; Sündermann, O. Mobile Behavioral Health Coaching as a Preventive Intervention for Occupational Public Health: Retrospective Longitudinal Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e45678. [CrossRef]

- Snowdon, A.; Hussein, A.; Olubisi, A.; Wright, A. Digital Maturity as a Strategy for Advancing Patient Experience in US Hospitals. J. Patient Exp. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, N.; Oehrlein, E.; Lewis, B.; Westrich-Robertson, T.; Elliott, J.; Willgoss, T.; Swarup, N.; Sargeant, I.; Panda, O.; Marano, M.M.; et al. Patient Engagement and Patient Experience Data in Regulatory Review and Health Technology Assessment: Where Are We Today?. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2025, 59, 737–752. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Hall, A. Lessons from the pandemic for the future regulation of confidential patient information for research. J. R. Soc. Med. 2023, 116, 5–9. [CrossRef]

- Bragge, P.; Delafosse, V.; Kellner, P.; Cong-Lem, N.; Tsering, D.; Giummarra, M.J.; A Lannin, N.; Andrew, N.; Reeder, S. Relationship between staff experience and patient outcomes in hospital settings: an overview of reviews. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e091942. [CrossRef]

- Leotin, S. Addressing Health Communication Gaps: Improving Patient Experiences and Outcomes Through Human-Centered Design. J. Patient Exp. 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Livieri, G.; Mangina, E.; Protopapadakis, E.D.; Panayiotou, A.G. The gaps and challenges in digital health technology use as perceived by patients: a scoping review and narrative meta-synthesis. Front. Digit. Heal. 2025, 7, 1474956. [CrossRef]

- Goodyear-Smith, F.; Bazemore, A.; Coffman, M.; Fortier, R.D.W.; Howe, A.; Kidd, M.; Phillips, R.; Rouleau, K.; van Weel, C. Research gaps in the organisation of primary healthcare in low-income and middle-income countries and ways to address them: a mixed-methods approach. BMJ Glob. Heal. 2019, 4, e001482. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Verhagen A, Elkins M, Brismée J-M, Fulk GD, Taradaj J, et al. Research from low-income and middle-income countries will benefit global health and the physiotherapy profession, but it requires support. Oxford University Press; 2023. p. pzad081.

- Shash, E.; Alaa, F.; Maher, E.; Rostom, J.F.; Ibrahim, A.; Said, R.; El-Kheir, N.A.; Elhosary, M.; Eid, R. Streamlining care through patient navigation: a retrospective cohort study of timely anti-HER2 therapy in early breast cancer in a low-middle income country. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- A Cipta, D.; Andoko, D.; Theja, A.; Utama, A.V.E.; Hendrik, H.; William, D.G.; Reina, N.; Handoko, M.T.; Lumbuun, N. Culturally sensitive patient-centered healthcare: a focus on health behavior modification in low and middle-income nations—insights from Indonesia. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1353037. [CrossRef]

- Tossaint-Schoenmakers, R.; Versluis, A.; Chavannes, N.; Talboom-Kamp, E.; Kasteleyn, M. The Challenge of Integrating eHealth Into Health Care: Systematic Literature Review of the Donabedian Model of Structure, Process, and Outcome. J. Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27180. [CrossRef]

- Moayed, M.S.; Khalili, R.; Ebadi, A.; Parandeh, A. Factors determining the quality of health services provided to COVID-19 patients from the perspective of healthcare providers: Based on the Donabedian model. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 967431. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.; Munro, J.; Evans, K.; Gaskin-Williams, A.; Hui, A.; Pearson, M.; Slade, M.; Kotera, Y.; Day, G.; Loughlin-Ridley, J.; et al. Health service improvement using positive patient feedback: Systematic scoping review. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0275045. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).