Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

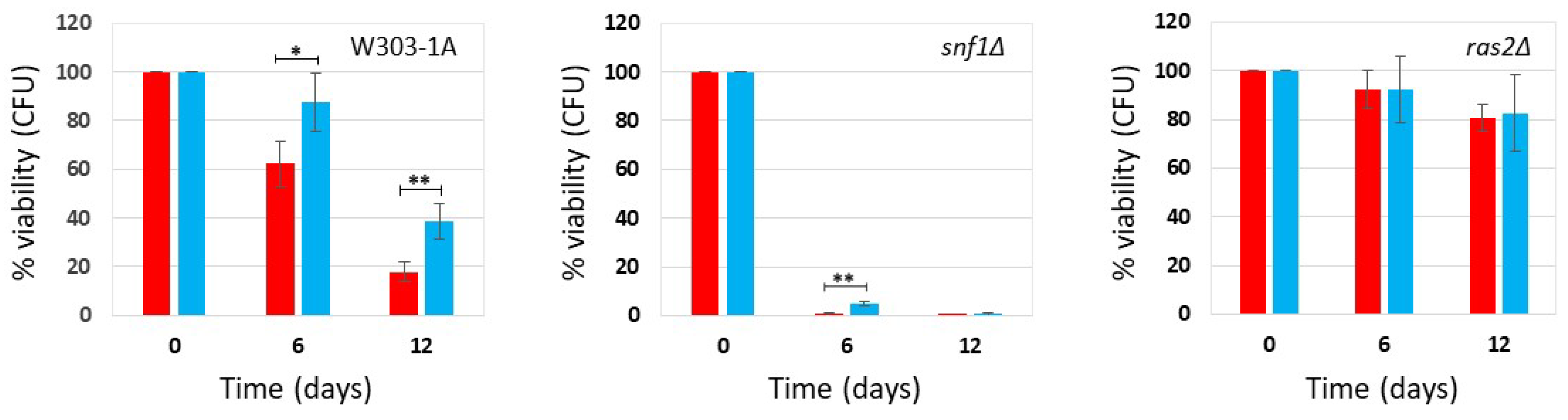

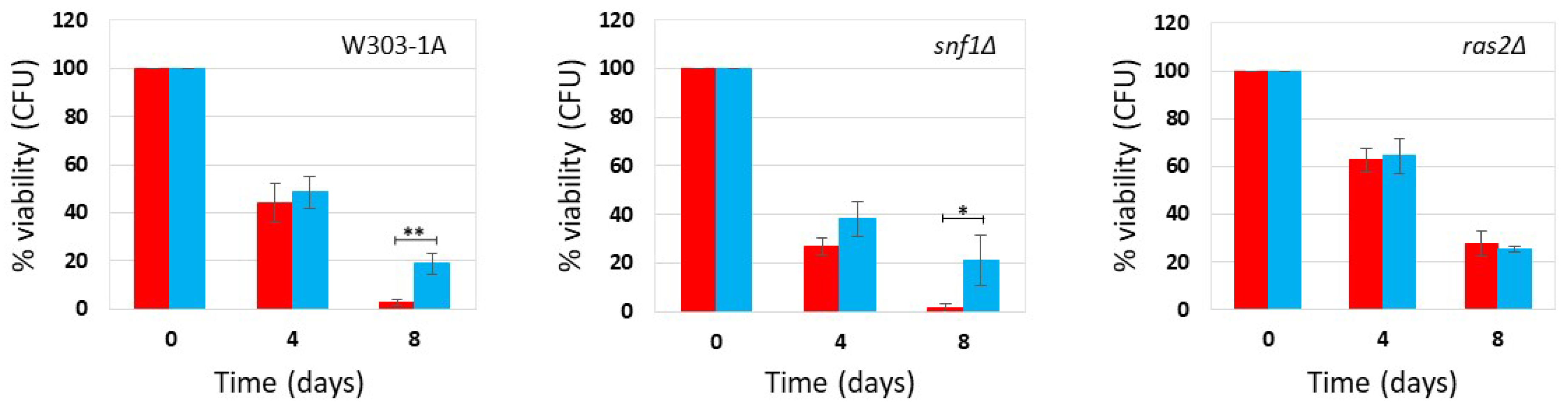

2.1. Effect of Phycocyanin on Saccharomyces Cerevisiae snf1Δ and ras2Δ Mutants

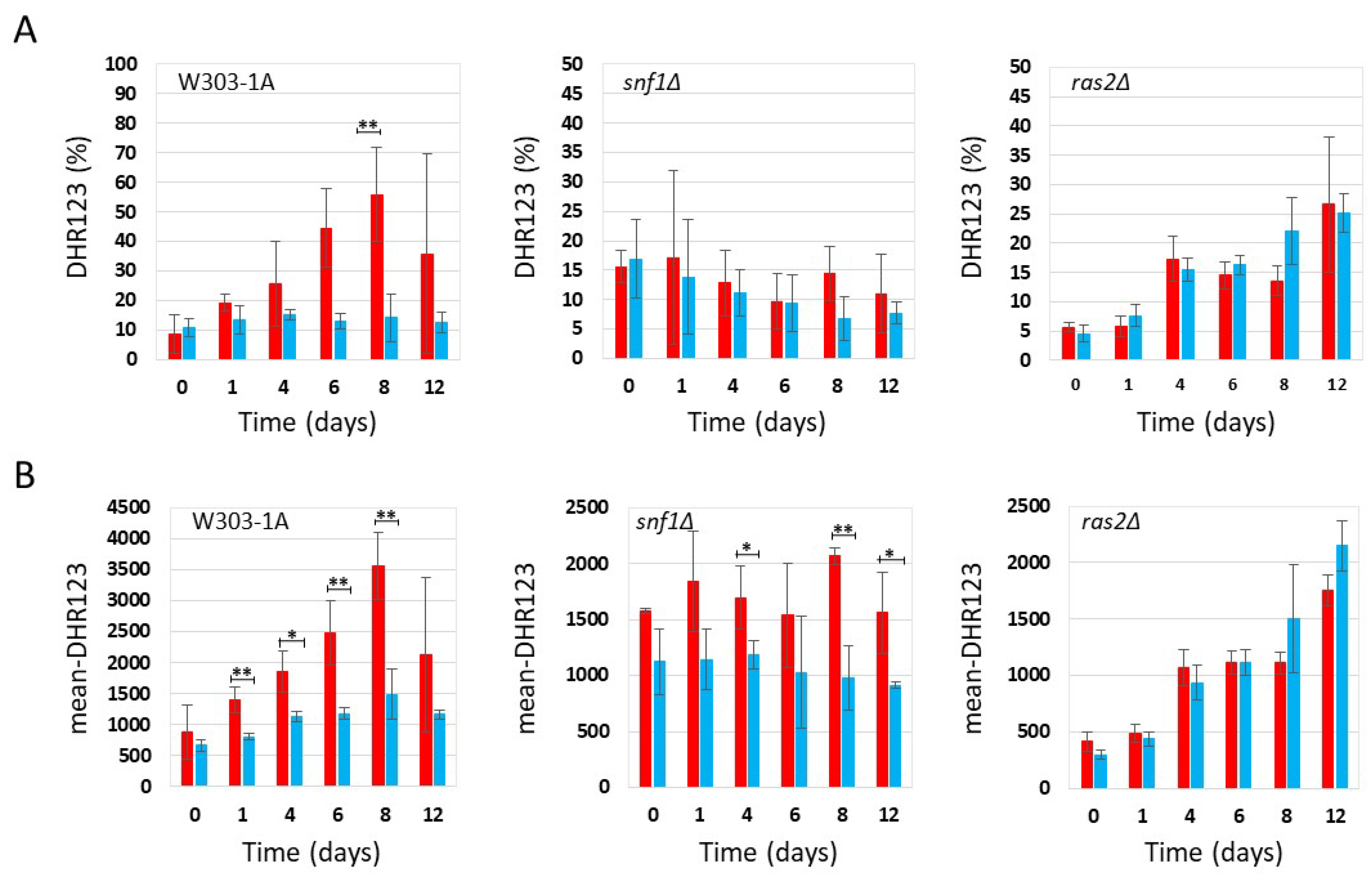

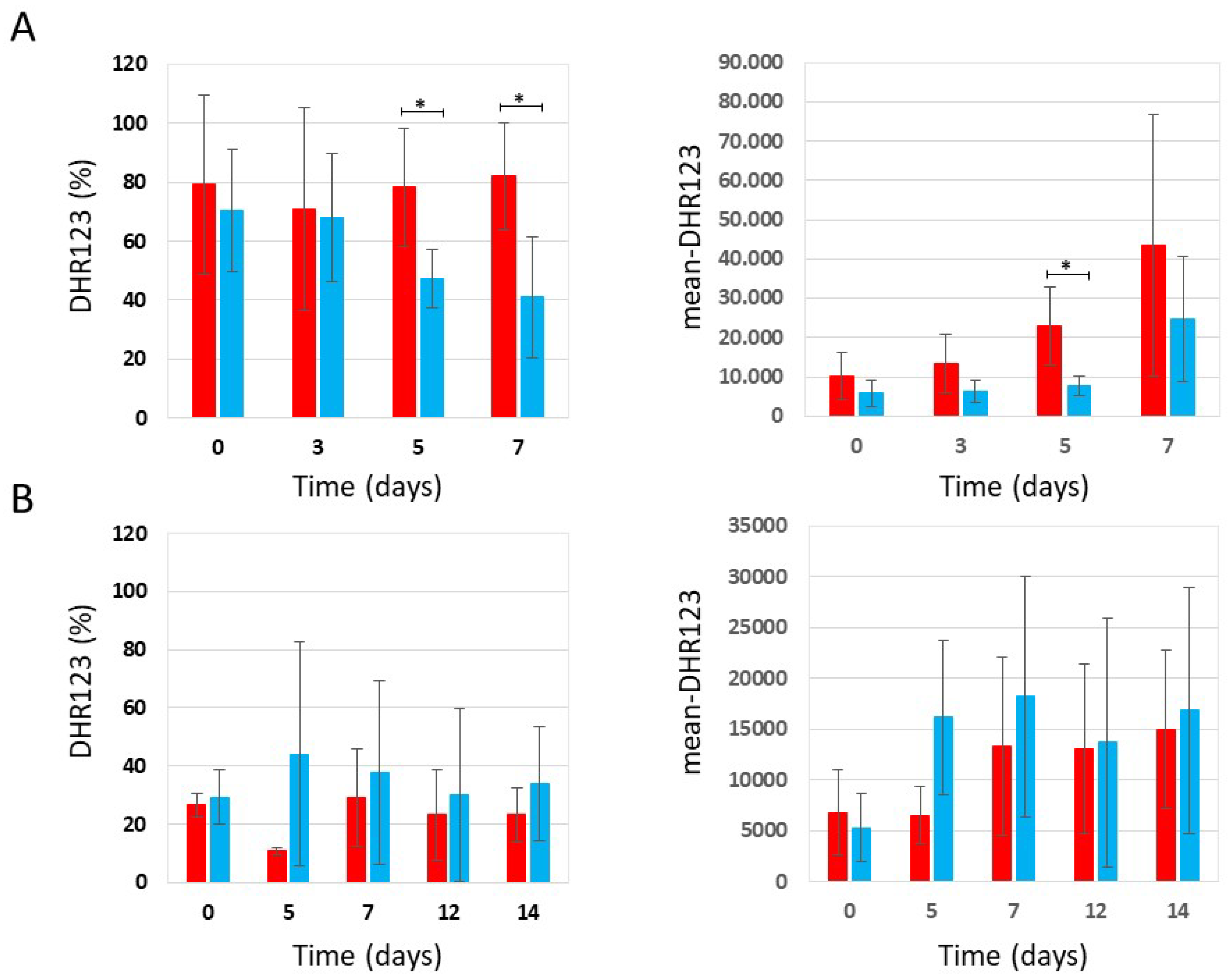

2.2. Effect of Phycocyanin on Sacchoromyces Cerevisiae Reactive Oxygen Species Accumulation in snf1Δ and ras2Δ Mutants

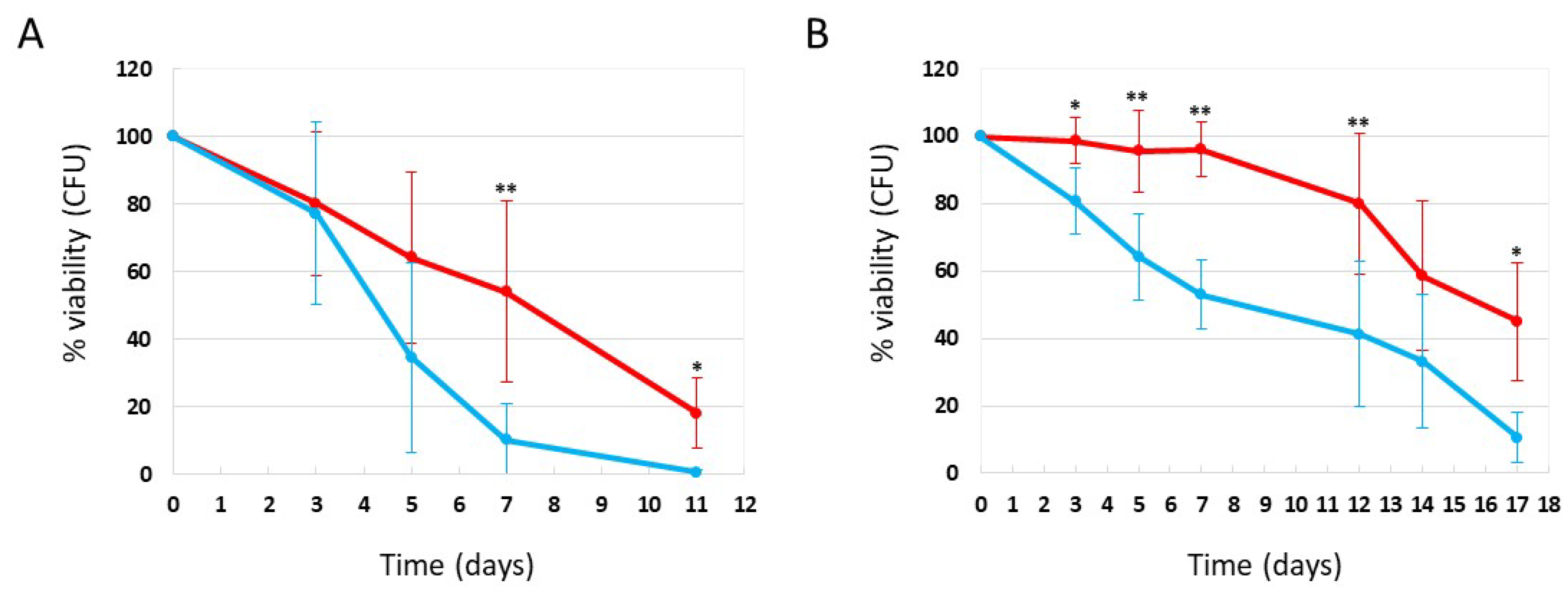

2.3. Phycocyanin Accelerates the Chronological Aging of Yeast Cells Grown in Rich Medium

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Yeast Strains and Media

3.2. Aging Experiments and Cell Viability

3.3. Staining with Dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123)

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, S.; Paneni, F.; Cosentino, F. Ageing, metabolism and cardiovascular disease. J Physiol. 2016, 594, 2061–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, N.; Parveen, S.; Tang, T.; Wei, J.; Huang, Z. Marine Natural Products in Clinical Use. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannu, S.A.; Lomada, D.; Gulla, S.; Chandrasekhar, T.; Reddanna, P.; Reddy, M.C. Potential Therapeutic Applications of C-Phycocyanin. Curr. Drug Metab 2019, 20, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddiboyina, B.; Vanamamalai, H.K.; Roy, H.; Gandhi, R.S.; et al. Food and drug industry applications of microalgae Spirulina platensis: A review. J Basic Microbiol. 2023, 63, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romay, C.; Armesto, J.; Remirez, D.; Gonzalez, R.; Ledon, N.; Garcıa, I. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of C-phycocyanin from blue-green algae. Inflamm. Res. 1998, 47, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, L.; Miron, A.; Klímová, B.; Wan, D.; Kuča, K. The antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory activities of Spirulina: An overview. Arch Toxicol 2016, 90, 1817–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The Bioactivities of Phycocyanobilin from Spirulina. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 4008991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogova, A.G.; Sergeeva, Y.E.; Sukhinov, D.V.; Ivaschenko, M.V.; Kuvyrchenkova, A.P.; Vasilov, R.G. The Effect of Phycocyanin Isolated from Arthrospira platensis on the Oxidative Stress in Yeasts. Nanobiotechnology Reports 2023, 18, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleonsila, P.; Soogarunb, S.; Suwanwong, Y. Anti-oxidant activity of holo- and apo-c-phycocyanin and their protective effects on human erythrocytes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 60, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nova, M.; Citterio, S.; Martegani, E.; Colombo, S. Unraveling the Anti-Aging Properties of Phycocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D.; Fabrizio, P. Chronological aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Subcell Biochem 2012, 57, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio-Marques, B.; Burhans, W.C.; Ludovico, P. Yeast at the forefront of research on ageing and age-related diseases. Prog Mol Subcell Biol 2019, 58, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, R.; Mohammad, T.; Alajmi, M.F.; Rehman, M.T.; Hasan, G.M.; Hussain, A.; Hassan, M.I. Insights into the Conserved Regulatory Mechanisms of Human and Yeast. Aging. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierman, M.B.; Maqani, N.; Strickler, E.; Li, M.; Smith, J.S. Caloric Restriction Extends Yeast Chronological Life Span by Optimizing the Snf1 (AMPK) Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L.; Longo, V.D. Extending healthy life span—From yeast to humans. Science 2010, 328, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Shadel, G.S.; Kaeberlein, M.; Kennedy, B. Replicative and chronological aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Metab 2012, 16, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrizio, P.; Longo, V.D. The chronological life span of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol Biol 2007, 371, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, P.; Pletcher, S.D.; Minois, N.; Vaupel, J.W.; Longo, V.D. Chronological aging-independent replicative life span regulation by Msn2/Msn4 and Sod2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2004, 557, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre-Ruiz, M.A.; Pujol, N.; Sundaran, V. Coping with oxidative stress. The yeast model. Curr. Drug Targets 2015, 16, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Nascarella, M.; Pressman, P.; et al. Hormesis determines lifespan. Ageing Research Reviews 2024, 94, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitti, M.; Marengo, B.; Furfaro, A.L.; Pronzato, M.A.; Marinari, U.M.; Domenicotti, C.; Traverso, N. Hormesis and Oxidative Distress: Pathophysiology of Reactive Oxygen Species and the Open Question of Antioxidant Modulation and Supplementation. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aris, J.P.; Fishwick, L.K.; Marraffini, M.L.; Seo, A.Y.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Dunn, W.A. Jr Amino acid homeostasis and chronological longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sub-cellular biochemistry 2012, 57, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Wei, M.; Mirzaei, H.; Madia, F.; Mirisola, M.; Amparo, C.; Chagoury, S.; Kennedy, B.; Longo, V.D. Tor-Sch9 deficiency activates catabolism of the ketone body-like acetic acid to promote trehalose accumulation and longevity. Aging cell 2014, 13, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.C.; Jaruga, E.; Repnevskaya, M.V.; Jazwinski, S.M. An intervention resembling caloric restriction prolongs life span and retards aging in yeast. The FASEB Journal 2000, 14, 2135–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Quan, S.; Huang, L.D. Dietary Restriction Depends on Nutrient Composition to Extend Chronological Life span in Budding Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.J.; Rothstein, R. Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell 1989, 56, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeo, F.; Herker, E.; Maldener, C.; Wissing, S.; Lächelt, S.; Herlan, M.; Fehr, M.; Lauber, K.; Sigrist, S.J.; Wesselborg, S.; Fröhlich, K.U. A caspase-related protease regulates apoptosis in yeast. Mol Cell 2002, 9, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büttner, S.; Eisenberg, T.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Ruli, D.; Knauer, H.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Sigrist, C.; Wissing, S.; Kollroser, M.; Fröhlich, K.U.; Sigrist, S.; Madeo, F. Endonuclease G regulates budding yeast life and death. Mol Cell 2007, 25, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Gutiérrez, D.; Bauer, M.A.; Ring, J.; Knauer, H.; Eisenberg, T.; Büttner, S.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Reisenbichler, A.; Magnes, C.; Rechberger, G.N.; Birner-Gruenberger, R.; Jungwirth, H.; Fröhlich, K.U.; Sinner, F.; Kroemer, G.; Madeo, F. The propeptide of yeast cathepsin D inhibits programmed necrosis. Cell Death Dis 2011, 2, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckenstuhl, C.; Netzberger, C.; Entfellner, I.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Kickenweiz, T.; Stekovic, S.; Gleixner, C.; Schmid, C.; Klug, L.; Sorgo, A.G.; Eisenberg, T.; Büttner, S.; Mariño, G.; Koziel, R.; Jansen-Dürr, P.; Fröhlich, K.U.; Kroemer, G.; Madeo, F. Lifespan Extension by Methionine Restriction Requires Autophagy-Dependent Vacuolar Acidification. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeo, F.; Fröhlich, E.; Ligr, M.; Grey, M.; Sigrist, S.J.; Wolf, D.H.; Fröhlich, K.-U. Oxygen stress: A regulator of apoptosis in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 145, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).