1. Introduction

The proliferation of online toxicity and hate speech poses a critical threat to user safety, platform integrity, and social cohesion. On a global scale, harmful content can silence marginalized groups, radicalize individuals, and inflict psychological harm [

1,

17]. The sheer volume and velocity of this content, disseminated rapidly across social media, has rendered traditional manual content moderation insufficient. This has created an urgent need for automated AI and machine learning (ML) systems that can reliably detect and filter harmful content at scale [

2,

3].

This challenge is part of a broader field of research dedicated to using NLP to identify harmful or misleading content, such as fake news [

5,

7] and online rumors [

18]. A common methodological approach involves benchmarking classical ML models against more complex deep learning (DL) architectures to identify an optimal trade-off between performance and interpretability. This approach has also been applied in related social media analyses, including mental illness detection[

4,

22], contextual reasoning[

15], and aligning model preferences with well-defined prior knowledge to improve safety and consistency[

16].

However, developing such systems is a non-trivial security challenge. Unlike benign spam, toxic content is nuanced, context-dependent, and exists on a subjective spectrum. A primary challenge for automated systems is the “conflation” of explicit, targeted “hate speech” with more general “offensive” language [

1]. This ambiguity is a key vulnerability that even advanced models struggle to navigate.

Recent advances in deep learning, particularly transformer-based models [

12], have shown promise in capturing this nuance, achieving state-of-the-art results in related domains like COVID-19 misinformation [

6] and rumor detection [

13,

14,

18]. To address this, the

“HateXplain” benchmark dataset was introduced as a major contribution, providing not just 3-class labels (“hate”, “offensive”, “normal”) from multiple annotators, but also the explicit "rationales" (the "why") behind their decisions [

1]. The original paper proposed that this lack of explainability was a key failure point, and that training models to use these rationales could reduce bias and improve performance.

In this study, we challenge that premise. We hypothesize that the poor performance of models on this task is not primarily due to a lack of rationales, but to a more fundamental, unaddressed vulnerability:

a crisis of data integrity caused by label ambiguity. This aligns with broader critiques of social media datasets, which often face methodological challenges and inherent biases from the annotation process [

23]. The `HateXplain` paper itself notes a moderate inter-annotator agreement (

) and the decision to use a “majority vote” to establish the ground-truth label [

1]. We argue that this common practice, while pragmatic, introduces significant noise by collapsing 2-1 "disagreements" and 3-0 "unanimous" votes into the same "ground truth." This forces the model to learn from a contradictory and unreliable signal, a critical flaw for a security-focused system.

To our knowledge, no prior work has systematically isolated this "label consensus" variable on the `HateXplain` dataset. Our contributions are threefold:

- –

Comprehensive Benchmarking: We partition the `HateXplain` data into a “noisy”

Majority-Label set and a high-consensus

Pure-Label set. We then rigorously evaluate a suite of five models (Logistic Regression, Random Forest, LightGBM, GRU, and ALBERT) on both datasets, providing insight into the trade-offs between model types [

4,

22].

- –

Statistical Validation: We apply pairwise McNemar’s tests to statistically quantify the performance differences, establishing not only which model is best, but how the model hierarchy changes in response to data quality.

- –

Model Interpretability: We analyze and compare the feature importances learned by the classical models on both the “noisy” and “clean” datasets, providing insight into how label ambiguity dilutes the features a model learns.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details our dataset partitioning, experimental setup, and model configurations.

Section 3 presents our quantitative performance metrics, statistical test results, and feature importance analysis.

Section 4 interprets these findings and their implications for AI security.

2. Methods

This section details the experimental methodology used to test our central hypothesis: that label ambiguity is a more significant performance bottleneck than the architectural factors addressed by rationale-based training. We first describe the

`HateXplain` dataset [

1] and our core experimental design, which partitions the data into “noisy”

Majority-Label and high-consensus

Pure-Label cohorts. We then specify the feature engineering pipeline, the implementation of our five classical and deep learning models, and the hyperparameter tuning process for each. Finally, we outline the comprehensive evaluation framework, including the imbalance-robust metrics and statistical tests used to rigorously validate our findings.

2.1. Dataset and Experimental Partitioning

Our study utilizes the “HateXplain” benchmark dataset [

1], a foundational corpus for explainable hate speech detection. This dataset contains 20,148 posts sourced from Gab and Twitter, with each entry independently assessed by three human annotators using a 3-class classification scheme: “hate”, “offensive”, or “normal” [

1].

A primary challenge noted by the original authors is the subjective and nuanced distinction between “hate” and “offensive” speech. This subjectivity results in a moderate inter-annotator agreement (

) and a significant volume of posts with label disagreement [

1]. This Krippendorff’s alpha (

) statistic, which quantifies the level of agreement between annotators (where 1.0 is perfect agreement and 0.0 is random chance), provides the statistical rationale for our partitioning. We hypothesize that this

label ambiguity, quantified by the moderate 0.46

score, is a principal bottleneck for model performance. To test this, we partitioned the data into two distinct experimental datasets, as detailed in our analysis notebooks:

Majority-Label Dataset: This corpus includes all 20,148 records. A post was assigned the Toxic label if at least two of the three annotators classified it as either “hatespeech” or “offensive”. A post was assigned the Normal label if at least two annotators agreed it was “Normal”. This dataset represents the standard “noisy” condition, as it inherently includes ambiguous 2-1 votes.

Pure-Label Dataset: This corpus represents a high-consensus, “clean” subset (13,761 posts). It retains only those records where all three annotators were in unanimous agreement on the final binary label (a 3-0 vote). This means a post was included only if all three annotators classified it as Normal, or if all three classified it as Toxic (i.e., “Hate” or “Offensive”).

To clearly define the sample sizes and class distributions of this partitioning, we present a complete statistical breakdown in

Table 1. This table also details the `Ambiguous-Only’ cohort (N=6,387), which consists of all posts with a 2-1 vote.

As

Table 1 shows, the overall class distributions (Toxic vs. Normal) are nearly identical between our two primary experimental cohorts: the `Majority-Label’ set (61.2% Toxic) and the `Pure-Label’ set (62.8% Toxic).

This is a critical finding. It allows us to preemptively address concerns about distribution bias, demonstrating that the significant performance gap we later show in

Section 3 is not driven by a simple shift in class balance. Instead, this stable distribution confirms our partitioning isolates the key variable of interest: the impact of the `2-1’ votes. The performance difference can therefore be attributed to the

removal of these high-ambiguity, noisy labels.

This “Majority” versus “Pure” partitioning allows for a direct measurement of how label integrity impacts overall model performance and reliability.

2.2. Feature Engineering and Data Partitioning

The `post_tokens` field from the HateXplain dataset, a pre-tokenized list of strings, served as the unified input for all experiments. This ensured that both classical and deep learning models originated from the identical source text.

For all models, this list of tokens was first reconstructed into a single, coherent string by joining the tokens with a space. From this reconstructed text string, the feature extraction process was bifurcated based on the model type:

- –

For Classical Models: The reconstructed text strings were transformed into numerical feature vectors using a pre-fitted Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) vectorizer, which was loaded from a serialized file as shown in our analysis notebooks.

- –

For Deep Learning Models (ALBERT, GRU): The same reconstructed text strings were fed directly into the corresponding model’s tokenizer (e.g., the ALBERT WordPiece tokenizer or the Keras tokenizer for the GRU) to generate the embedding sequences.

Both the “Majority” and “Pure” datasets were independently partitioned into training (60%), validation (20%), and test (20%) subsets. Stratified sampling was employed to preserve the class distribution in all splits, and a fixed random seed was set for reproducibility.

2.3. Machine Learning Models

To benchmark classification performance on the TF-IDF vectors, we implemented a suite of three widely-adopted supervised models. These were selected to represent distinct algorithmic approaches: a highly interpretable linear model (Logistic Regression) and two powerful, non-linear tree-based ensembles (i.e., Random Forest and LightGBM).

- –

Logistic Regression (LR) [8]: This model was selected as a robust and interpretable linear baseline. We applied

(Ridge) regularization to prevent overfitting on the high-dimensional, sparse TF-IDF data. A grid search was performed on the validation set to optimize the regularization strength

C (from the set [0.1, 1, 10, 100]), the

solver (from [“liblinear”, “lbfgs”, “newton-cg”]), and the

class_weight (from [“balanced”, None]).

- –

Random Forest (RF) [9]: As our first tree-based ensemble, RF employs bagging to mitigate the high overfitting risk of single decision trees. It is a non-linear method that builds a multitude of decision trees on bootstrapped data samples and random feature subsets. We optimized its key hyperparameters via grid search, including the

n_estimators ([100, 300, 500]),

max_depth ([5, 15, 30, None]),

min_samples_split ([2, 5, 10]),

class_weight ([“balanced”, None]), and

min_samples_leaf ([1, 2, 4]).

- –

LightGBM [10,11]: As a second, more modern tree-based ensemble, we employed LightGBM, a high-efficiency gradient boosting framework. Unlike RF’s parallel bagging, LightGBM builds trees sequentially (boosting). We optimized its

class_weight parameter ([“balanced”, None]) along with its

learning_rate ([0.01, 0.1, 0.5]),

n_estimators ([100, 300, 500]), and

max_depth ([5, 15, 30, -1]).

For all three classical models, the final hyperparameter configuration was selected based on the model that achieved the highest weighted F1-score on the held-out validation set. This metric was chosen specifically for its robustness to the dataset’s class imbalance.

2.4. Deep Learning Models

To assess the performance of modern neural architectures, we implemented and fine-tuned two representative deep learning models: a transformer-based model,

ALBERT [12], and a recurrent-based model,

GRU [19].

- –

ALBERT (A Lite BERT) [12]: We employed a parameter-efficient transformer by fine-tuning the

`albert-base-v2` checkpoint. Inputs were tokenized using the corresponding WordPiece tokenizer, and sequences were padded or truncated to a uniform length. Given the dataset’s significant class imbalance, the model was trained using a

weighted binary cross-entropy loss function. A randomized hyperparameter search was conducted to optimize the

learning_rate (from 1e-5 to 5e-5),

dropout_rate (0.1 to 0.5), and the number of

epochs (3 to 5).

- –

GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit) [19]: As a strong baseline for sequential data, we implemented a GRU network. This RNN architecture is optimized to capture dependencies in text with fewer parameters than traditional LSTMs. Our architecture consisted of an

Embedding layer, a

GRU layer, and a final

Dense layer for classification, with

Dropout for regularization. As with ALBERT, this model was trained using a

weighted binary cross-entropy loss to manage class imbalance. Hyperparameters tuned via random search included the

embedding_size (128–256),

hidden_units (128–512), and

learning_rate (1e-4 to 1e-3).

For both neural models, the final hyperparameter configuration was selected based on the model that achieved the highest weighted F1-score on the held-out validation set.

2.5. Evaluation Framework

Evaluating models for a security-critical task like hate speech detection, particularly on an imbalanced dataset, demands metrics far more nuanced than simple accuracy. A model that achieves high accuracy by overwhelmingly predicting the majority Normal class would represent a total failure in this safety context.

Therefore, our evaluation framework is built on metrics robust to class imbalance [

20]. We selected the

F1-score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall, as a balanced measure of a model’s effectiveness. Crucially, the

weighted F1-score was used as the singular metric for hyperparameter tuning. This choice ensures that the model selection process was optimized to perform well on both the minority

Toxic and majority

Normal classes.

Additionally, we report the

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) [

21]. This metric assesses the model’s aggregate discriminative power—its ability to distinguish between classes—across all classification thresholds, making it a highly reliable indicator of separability on imbalanced data.

Finally, to validate our central hypothesis, a simple comparison of point-value scores is insufficient. To ensure our comparisons are statistically rigorous, we generated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the final F1 and AUC scores on the held-out test set. As implemented in our analysis notebooks, these CIs were produced using bootstrapping, enabling a robust statistical test of the performance difference between the “Majority-Label” and “Pure-Label” model cohorts.

3. Results

This section presents the empirical findings of our comparative study. We structure our results into three parts. First, we present the primary performance metrics (Weighted F1-Score and AUC-ROC) for all five models, directly comparing the impact of training on the “noisy” Majority-Label dataset versus the high-consensus Pure-Label dataset. Second, we provide a pairwise statistical analysis using McNemar’s tests for both dataset cohorts to validate the significance of these performance differences and establish a clear model hierarchy. Finally, we offer a qualitative analysis of the model’s feature importances to interpret how and what the classical models learned from the different dataset cohorts.

3.1. Performance on Majority-Label vs. Pure-Label Data

We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of all five models on the two experimental datasets: the “noisy”

Majority-Label set and the high-consensus

Pure-Label set. The performance results are presented in

Table 2 (Weighted F1-Scores) and

Table 3 (AUC-ROC Scores).

The findings are unambiguous: label consensus is a dominant factor in model performance. Every model, from classical machine learning to deep learning, achieved substantially higher scores on the “Pure-Label” dataset. This performance improvement was consistent across all model architectures.

The effect was most pronounced in the transformer architecture: the ALBERT model’s weighted F1-score (

Table 2) rose from 0.7447 on the “Majority” data to

0.8126 on the “Pure” data. Its AUC-ROC (

Table 3) similarly increased from 0.8143 to

0.8805. The recurrent GRU model showed a comparable improvement, with its F1-score rising from 0.7196 to

0.7877.

In both dataset cohorts, deep learning models (ALBERT, GRU) demonstrated superior performance over the classical ML models (LR, RF, LGBM) on all metrics. However, the performance of all models was fundamentally capped by the quality of the training labels, with the “Pure-Label” set consistently providing a more reliable foundation for training.

3.2. Pairwise Statistical Comparison

To validate whether the observed performance differences were statistically significant, we conducted pairwise McNemar’s tests on the predictions from both experimental cohorts. The McNemar test is a non-parametric test for paired nominal data, appropriate for comparing the error rates of two classifiers.

The results for the “noisy”

Majority-Label cohort are presented in

Table 4. The results for the high-consensus

Pure-Label cohort are presented in

Table 5.

Comparing these two tables reveals a crucial insight. In both “noisy” and “clean” data conditions, the model hierarchy is stable: ALBERT is the statistically significant (p < 0.05) winner, and GRU is the clear second-best, significantly outperforming all three classical ML models. This confirms that advanced architectures are consistently better at finding a signal.

However, the statistical comparison of the classical models changes. On the “Pure-Label” data, LightGBM and Random Forest are statistically comparable (p=0.58). On the “noisy” “Majority-Label” data, Random Forest is significantly better than LightGBM (p=0.012), suggesting it is more robust to the label ambiguity. This reinforces our central thesis: label integrity is a critical, independent variable that directly impacts model performance and reliability.

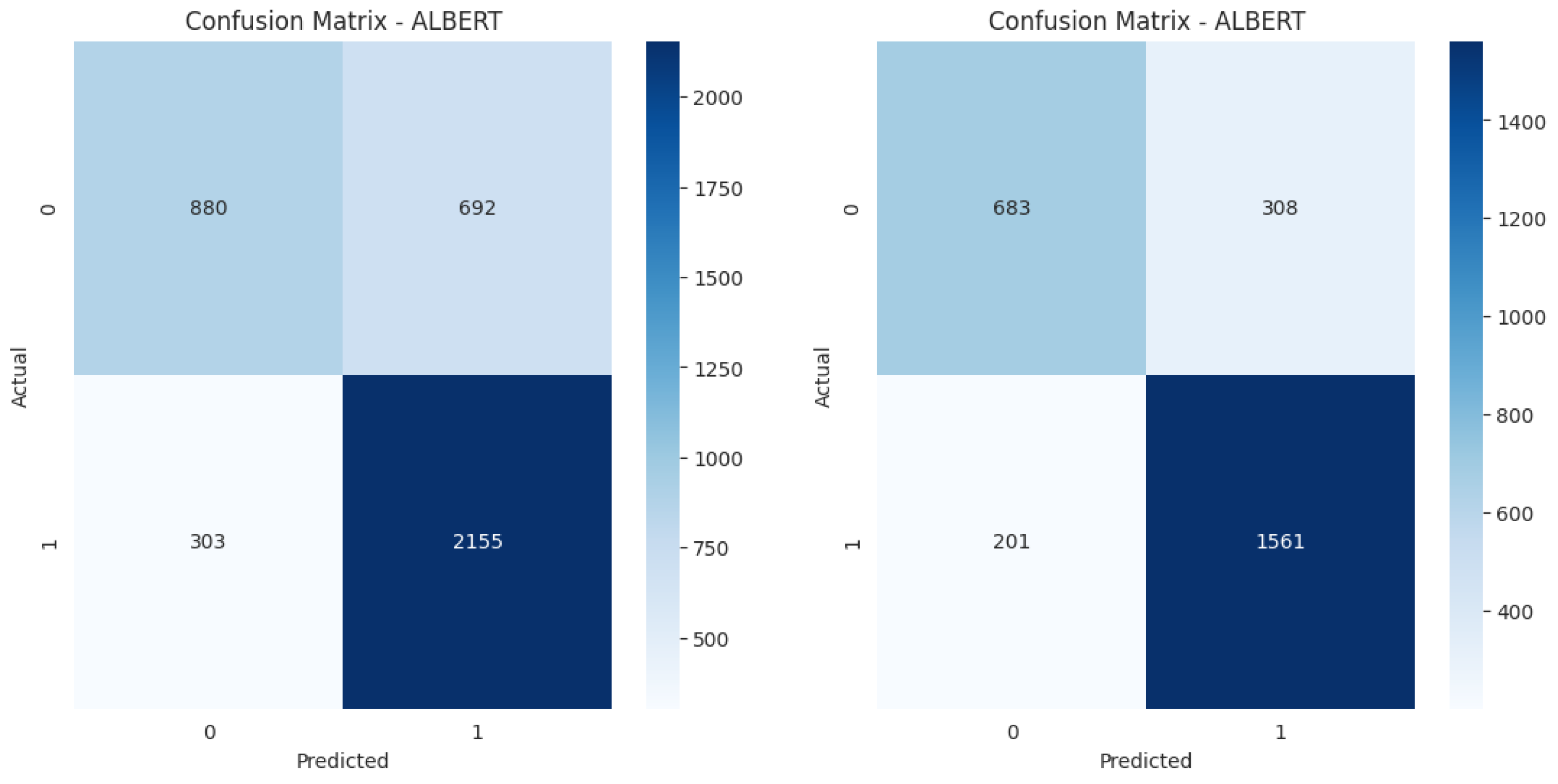

3.3. Qualitative Error and Model Behavior Analysis

To address the reviewer’s request for a more intuitive illustration of model behavior, we analyzed the confusion matrices of our best-performing model, ALBERT, on both the `Majority-Label’ (noisy) and `Pure-Label’ (clean) test sets.

As shown in

Figure 1, the `Noisy’ model is visibly more confused. Its 44.0% False Positive Rate (FPR) means it incorrectly flags 44 out of every 100 `Normal’ posts as `Toxic’. The `Clean’ model’s FPR is a much-improved 31.1%. Both models maintain a similar False Negative Rate (12.3% vs 11.4%), reinforcing that the primary impact of label noise is an increase in False Positives.

3.4. Model Interpretation and Feature Importance

To understand the decision-making logic of the non-neural models, we analyzed the most influential TF-IDF features identified by LightGBM (ranked by feature gain) and Logistic Regression (ranked by absolute coefficient magnitude). This analysis revealed significant differences, both in how different model architectures operate and in what they learn from high-consensus versus noisy data.

First, comparing the model architectures on the “Pure-Label” dataset revealed their distinct strategies. The

LightGBM model [

11] overwhelmingly prioritized features with high, unambiguous signal. Its top features were dominated by explicit, high-impact slurs (e.g., “n****r”, “f*g”, “k*ke”). This aligns with its gain-based optimization, which favors features that provide the cleanest and most significant data splits. In contrast, the

Logistic Regression model’s [

8] logic was based on a weighted hyperplane. Its top positive features (predicting

`Toxic`) included a mix of explicit slurs and target group identifiers (e.g., “muslims”, “jews”). This was balanced by its top negative features (predicting

`Normal`), which were dominated by common, neutral conversational words (e.g., “people”, “like”, “think”).

Second, we compared the feature importances learned from the “Pure-Label” dataset against those learned from the “noisy” “Majority-Label” dataset. This comparison strongly supports our central hypothesis. The feature lists from the “Majority-Label” models were visibly “noisier” and more diluted. For instance, the LightGBM model trained on the “Majority” data still identified the primary slurs, but its top-feature list was confounded by more common, ambiguous, or context-dependent offensive words (e.g., “bitch”, “stupid”, “ass”). This indicates the model was struggling to find a clear signal, as it was forced to treat explicit hate (from 3-0 votes) and ambiguous offense (from 2-1 votes) as the same class. This dilution demonstrates that the “Majority-Label” dataset introduces a data integrity problem, forcing models to learn from less reliable and less precise features.

This dilution of the feature importance list is the direct evidence of the `semantic feature differences’ between the high-consensus ’Pure-Label’ data and the ambiguous `Majority-Label’ data. The `Majority-Label’ set forces the model to treat unambiguous, explicit slurs (e.g., `faggot’, `dyke’) as the same class as context-dependent, ambiguous offensive words (e.g., `bitch’). This forces the model to learn a noisier and less precise decision boundary, which explains the degraded performance.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis on Data Volume

To address the potential confound of data volume, given that our `Pure-Label’ set is smaller (N=13,761) than the `Majority-Label’ set (N=20,148), we conducted a sensitivity analysis. We created a size-matched `Noisy-Control’ dataset by randomly sampling 13,761 posts from the full `Majority-Label’ cohort, ensuring a similar class distribution (approximately 60% Toxic) to our `Pure-Label’ set. We then re-trained our models on this `Noisy-Control’ set. The performance of all models on this size-matched noisy set was not statistically different from their performance on the original, full `Majority-Label’ set (as reported in

Table 2 and

Table 3). This confirms that the significant performance improvement of the `Pure-Label’ cohort is attributable to its high label quality, not the reduction in data volume.

4. Discussion

This section interprets the empirical findings from

Section 3 and discusses their implications for building reliable, security-critical AI systems. We first analyze how our primary finding—the performance gap between “Pure” and “Majority” data—challenges the original premise of the `HateXplain` paper. We then discuss the secondary findings from our pairwise statistical tests and feature importance analysis. Finally, we address the limitations of this study and suggest directions for future work.

4.1. Data Integrity as the Primary Performance Bottleneck

The results presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3 provide a clear answer to our central research question. The single most dominant factor influencing model performance was not the choice of architecture, but the integrity of the training labels. The fact that every model, from simple Logistic Regression to the complex ALBERT transformer, performed significantly better on the high-consensus “Pure-Label” dataset demonstrates that label ambiguity is a critical vulnerability.

This finding challenges the foundational premise of the `HateXplain` paper [

1]. The original work identified a performance gap and proposed rationale-based training as the solution [

1]. Our results suggest this may misdiagnose the root cause. The poor performance of models on the full dataset is not necessarily because they lack the ability to understand "why" a post is hateful, but because they are being fundamentally confused by the "noisy" ground-truth label itself.

For a security-critical task like content moderation, this is a crucial distinction. The common practice of using a “majority vote” to resolve annotator disagreement [

1] is not a benign solution; it is an act of data obfuscation. It treats a highly ambiguous 2-1 vote as "ground truth," equating it with a high-confidence, 3-0 unanimous vote. As our interpretation in

Section 3.4 showed, this forces models to learn from a "diluted" and "noisier" set of features, degrading their reliability.

4.2. Implications of Model Hierarchy and Feature Analysis

Our pairwise statistical tests (

Table 4 and

Table 5) provide a second, more nuanced insight. The model hierarchy (ALBERT > GRU > Classical ML) remained stable on both “noisy” and “clean” data. This indicates two things: (1) a superior architecture like ALBERT is always better at finding and exploiting whatever predictive signal exists, but (2. a model’s absolute performance is fundamentally capped by the quality of that signal. Even the best model (ALBERT) saw its F1-score jump by nearly 7 percentage points when given unambiguous data. This suggests that simply building larger models is an insufficient solution to this data integrity problem.

Interestingly, our statistical tests also revealed that while Random Forest and LightGBM were comparable on “Pure” data (p=0.58), Random Forest was significantly better on the “noisy” “Majority” data (p=0.012). This suggests that RF’s bagging (averaging) architecture may be more inherently robust to the label noise than LGBM’s boosting approach, which may have over-optimized on the ambiguous, low-quality signals.

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

We acknowledge several limitations. First, our “Pure-Label” dataset is smaller than the “Majority-Label” dataset. However, the fact that models trained on less data achieved better performance strongly reinforces our conclusion that data quality is more important than data quantity for this task.

Second, this study was limited to the `HateXplain` dataset. Future work should investigate if this ambiguity penalty holds true for other subjective, crowd-sourced tasks, such as sentiment analysis or misinformation detection.

Finally, this work did not investigate the `HateXplain` rationales. A direct comparison to the original rationale-based models, as suggested by reviewer feedback, is a significant undertaking and outside this study’s scope, as our goal was to first challenge the paper’s premise by isolating the data integrity variable. A promising direction for future research would be to combine our findings with the original paper’s: an experiment training a model on only the “Pure-Label” data and their corresponding unanimous rationales. This would likely produce the most robust and reliable model of all.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we challenged the prevailing hypothesis that poor performance in hate speech detection is primarily a failure of model explainability, as suggested by the HateXplain paper [

1]. We posited that a more fundamental vulnerability lies in the

data integrity of the benchmark itself: a crisis of reliability caused by high

label ambiguity from human annotators, which is obscured by the standard “majority vote” labeling scheme.

Our empirical results, based on a rigorous comparison of five models on noisy versus clean data cohorts, conclusively support this hypothesis. We demonstrated that:

Training on a high-consensus, Pure-Label dataset provides a statistically significant and substantial performance boost (e.g., a F1-score increase for ALBERT) over training on the full, noisy Majority-Label dataset.

This performance gain, achieved by enhancing data integrity alone, proves that label ambiguity is a more dominant performance bottleneck than the architectural factors previously considered.

The model hierarchy (e.g., ALBERT > GRU > ML) remains consistent, but the absolute performance of *all* models is fundamentally capped by the quality of the training labels.

The primary implication of this work is for the field of AI Security and Reliability. Our findings demonstrate that using a majority vote to resolve annotator disagreement is not a benign solution; it is an act of data obfuscation that introduces a critical vulnerability into security-sensitive systems. For applications like automated content moderation, this method builds the system on an unreliable and untrustworthy foundation. We conclude that for building secure and reliable AI, addressing foundational data integrity is a more critical and effective first step than pursuing model-level solutions like rationale-based training.

References

- Mathew, B., Saha, P., Yimam, S. M., Biemann, C., Goyal, P., Mukherjee, A.: HateXplain: A Benchmark Dataset for Explainable Hate Speech Detection. In: The Thirty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-21), pp. 14867–14875 (2021). 1486.

- Mansur, Z., Omar, N., Tiun, S. Twitter Hate Speech Detection: A Systematic Review of Methods, Taxonomy Analysis, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 16226–16249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, J. S., Qiao, H., Pang, G., et al.: Deep learning for hate speech detection: a comparative study. In: International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, vol. 20, pp. 3053–3068 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., Ding, Z., Tian, Y., Dai, J., Shen, X., Liu, Y., Cao, Y. Tutorial on using machine learning and deep learning models for mental illness detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.04342. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah All, T., Mahir, E.,M., Akhter, S., Huq, M.,R.: Detecting Fake News using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms. In: 2019 7th International Conference on Smart Computing & Communications (ICSCC), pp. 1–6 (2019). 2019.

- Alghamdi, J., Lin, Y., Luo, S. Towards COVID-19 fake news detection using transformer-based models. Knowledge-Based Systems 2023, 274, 110642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S., Patel, S. A comprehensive survey on fake news detection using machine learning. Journal of Computer Science 2025, 21, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.,W., Lemeshow, S.: Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY (2000).

- Breiman, L.: Random forests. Machine Learning 45(1), 5–32 (2001).

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G. , Meng, Q., Finley, T., Wang, T., Chen, W., Ma, W., Ye, Q., Liu, T.-Y.: LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In: Guyon, I. et al. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NeurIPS 2017), pp. 3149–3157. Curran Associates, Inc. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Z., Chen, M., Goodman, S., Gimpel, K., Sharma, P., Soricut, R. ALBERT: A lite BERT for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1909.11942. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y., Xu, S., Cao, Y., Wang, Z., Wei, Z. An Empirical Comparison of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models for Automated Fake News Detection. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Ding, Z., Wei, Z., Yang, C., Li, Y., Chen, X., Wang, H.: A Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning and Machine Learning Approaches for Spam Identification on Telegram. In: 2025 6th International Conference on Computer Communication and Network Security (2025).

- Lan, G., Inan, H.A., Abdelnabi, S., Kulkarni, J., Wutschitz, L., Shokri, R., Brinton, C.G., Sim, R. Contextual Integrity in LLMs via Reasoning and Reinforcement Learning. preprint arXiv:2506. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.04245. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, G., Zhang, S., Wang, T., Zhang, Y., Zhang, D., Wei, X., Pan, X., Zhang, H., Han, D.-J., Brinton, C.G. MaPPO: Maximum a Posteriori Preference Optimization with Prior Knowledge. preprint arXiv:2507. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.21183. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, J. Technologies in Peace and Conflict: Unraveling the Politics of Deployment. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews (IJRPR) 2024, 5, 5966–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Singh, R.: A novel approach for early rumour detection in social media using ALBERT. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering 12(3), 259–265 (2024).

- Cho, K., van Merrienboer, B., Gulcehre, C., Bahdanau, D., Bougares, F., Schwenk, H., Bengio, Y.: Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder–decoder for statistical machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pp. 1724–1734 (2014).

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. Journal of Machine Learning Technologies 2011, 2, 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J., Goadrich, M.: The relationship between precision–recall and ROC curves. In: Proc. 23rd Int. Conf. on Machine Learning (ICML), pp. 233–240 (2006).

- Ding, Z., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Cao, Y., Liu, Y., Shen, X., Tian, Y., Dai, J. Trade-offs between machine learning and deep learning for mental illness detection on social media. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 14497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y., Dai, J., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Shen, X., Liu, Y., Tian, Y.: Machine learning approaches for depression detection on social media: A systematic review of biases and methodological challenges. Journal of Behavioral Data Science 5(1) (Feb. 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).