1. Introduction

Polydiacetylenes (PDAs) are regarded as one of the most strategic polymers for sensing applications due to their ability to undergo chromatic transitions in the visible range upon external stimuli such as temperature [

1,

2,

3], pH [

4,

5] and interactions with different molecules [

6,

7]. PDAs were first prepared by Wegner in 1969 [

6]; however, it was the work of Charych and co-workers in 1993 that revealed the remarkable potential of these materials through their use in the detection of the influenza virus, paving the way for applications in diagnostics and therapeutics [

8].

PDAs are obtained through the topochemical polymerization of diacetylene monomers that can be self-organized into different architectures, such as Langmuir–Blodgett/Langmuir–Schaefer films [

9,

10,

11], crystalline solids [

12,

13], lipid bilayers or vesicles in aqueous solution [

14,

15], among other structures. In these supramolecular arrangements, the monomers adopt a highly ordered geometry, with appropriate intermolecular distances between C≡C bonds and a packing angle of approximately 45°, allowing the 1,4-addition reaction to occur upon UV or γ irradiation, generating a polymeric backbone with alternating double and triple bonds (ene–yne) [

16,

17]. The chromatic transition of PDAs arises from environmental perturbations (such as temperature and pressure) or chemical interactions that are capable to alter the conformation of the carbon chains, reducing the conjugation length of the π system, and consequently lead to an increase in the energy gap between the frontier molecular orbitals [

18]. As a result, the absorption band associated with the π–π transition shifts from approximately 640–660 nm to 540–560 nm, which manifests as a visible color change from blue to red.

With the understanding of these properties, numerous studies have been conducted to explore the thermochromism, mechanochromism, solvatochromism, and affinity-chromism of PDAs [

16,

17]. Moreover, the modification of monomers or the formulation of composites have been extensively employed for the selective detection of metals [

19], carcinogenic organic compounds [

20], and even large and complex biomolecules (including proteins) [

21]. In this context, investigating approaches not only to modulate, but also to control the sensitivity of the chromatic transition of these structures becomes highly relevant.

In 2017, Ferreira et al. demonstrated that the preparation of PDA vesicles in aqueous solution containing EO–PO–EO triblock copolymers (EO = ethylene oxide, PO = propylene oxide), commercially known as Pluronics or Synperonics, results in structures exhibiting different sensitivities to chromatic transitions [

22]. These authors showed that using copolymers with higher molar mass, at high concentration, and a larger number of propylene oxide segments leads to suspensions that undergo color transition at progressively lower temperatures. This work was later extended by our group in 2021 [

1], through the incorporation of triblock copolymers into PDA/poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels, enabling the modulation of thermochromic transitions in solid films, which are technologically more convenient for applications such as smart packaging.

In this work, we demonstrate for the first time that triblock copolymers can be employed with an opposite effect: instead of increasing the sensitivity of the chromatic transition, these molecules can act as inhibitors, reducing the affinity-chromism of PDA structures in the presence of cyclodextrin, CD, (specifically, α-CD). CDs are classified as biocompatible macrocycles, formed by glucose units linked by α (1–4) bonds, which results in a three-dimensional described as a truncated cone architecture, leading to a hydrophobic cavity and a hydrophilic outer surface [

23]. The most used CDs are: α-, β-, and γ-CD, formed by 6, 7, and 8 glucose units, respectively. CDs emerge as invaluable supramolecular strategy applicable across different areas of science, including biomaterials [

24], mainly in the pharmaceutical field [

25], pollutant adsorption based on nanosponges materials [

26], gas sensing, and chemical and physical sorption [

27], due to CDs capability to form inclusion complexes (ICs) with a variety of guest molecules, including surfactants [

28].

The chromatic transition of PDAs induced by α-CD was first investigated by Cho et al. in 2003 using polymerized diacetylene Langmuir–Schaefer films [

9]. In 2009, Champaiboon et al. demonstrated that the chromatic transition of PDA films can be inhibited and consequently modulated through the addition of nitrophenols to the system, particularly 4-nitrophenol [

29]. However, these compounds are toxic to humans, causing methemoglobinemia [

30], and are highly toxic to aquatic organisms, being considered environmental pollutants [

31]. In contrast, Pluronic® triblock copolymers are regarded as non-toxic, biocompatible, and safe for a wide range of applications, including pharmaceutical and cosmetic uses [

32].

Herein, we show that PDA vesicles undergo a chromatic transition upon interaction with α-CD, while the presence of varying concentrations of the triblock copolymer L64 inhibits this response through competitive inclusion complex formation. This controlled modulation of PDA color change provides a versatile, safe, and biocompatible platform for practical applications, including the visual detection of biomolecules, environmental monitoring of specific analytes, and smart packaging.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

The diacetylene monomer 10,12-pentacosadiynoic acid (PCDA, 97% purity, w/w) and the triblock copolymer poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(propylene glycol)-block-poly(ethylene glycol) (L64, MW = 2900) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Prior to use, PCDA was purified by dissolving it in chloroform and filtering the solution to eliminate any polymerized residues. All other reagents and solvents were of analytical or reagent grade, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and employed without further purification unless otherwise stated.

Preparation of PDA Vesicle and PDA/L64 Suspensions

PCDA monomers were dispersed in deionized water to yield a final monomer concentration of 1 mM. The resulting mixture was sonicated until a transparent dispersion was obtained and subsequently filtered through a 0.45 μm polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The filtrate was kept at 4 °C for 12 h to promote the ordering of the lipid bilayers. Polymerization was then achieved by UV irradiation at 254 nm for 5 min, generating a blue-colored suspension of PDA vesicles.

For the preparation of PDA/L64 blends, PCDA monomers were incorporated into aqueous L64 solutions at various polymer concentrations (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 8.0% w/w). The mixtures underwent the same sonication, filtration, cooling, and photopolymerization steps as described for the pure PDA vesicles.

Preparation of PDA/L64/α-CD Mixtures

An aqueous α-cyclodextrin (α-CD) solution (50 mM) was freshly prepared. Aliquots of this solution were added to the PDA/L64 dispersions (0–8.0% w/w) to obtain samples with final α-CD concentrations ranging from 0 to 7 mM. The tubes were photographed with a digital camera, and to quantify the colorimetric response, the red and blue color intensities were extracted from the RGB images using ImageJ® software. RGB values were measured in regions of interest (ROIs) corresponding to approximately 60% of the total image area, with six different points analyzed for each sample. UV–Vis spectra of the PDA/L64/α-CD suspensions were also recorded using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Bel Photonics M51).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry Experiments

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were performed using a VP-ITC microcalorimeter (Microcal®). Thermodynamic parameters were determined by placing the PDA vesicles (without L64) or L64 aqueous solution in the reaction cell and α-CD in the titration syringe. The α-CD concentration was fixed at 12.0 mmol L–1 and L64 at 2.0 mmol L–1. For PDA vesicles, this sample was used after its preparation proceeded without any change. Titrations were performed in duplicate, with 25 successive injections of the aqueous α-CD solution into the L64 or PDA vesicles aqueous suspensions. Titrations were conducted with a spacing of 300 s between injections for both systems at 298.15 K. The first injection of each titration (1.0 μL) was discarded to eliminate dispersion effects, and the subsequent injections were of 10.0 μL each. The reference cell of the calorimeter was filled with Milli-Q® water. Complementary dilution experiments were carried out under the same conditions as described above to account for the interaction of host and guest molecules. Thus, titrations of α-CD aqueous solution into Milli-Q® water and of Milli-Q® water into L64 or PDA vesicles aqueous suspensions were also performed and subsequently used for subtracting from their respective titrations.

The calorimetric data were analyzed using ORIGIN 7.0 software for ITC, which employs a nonlinear regression model to fit the curves based on the Wiseman isotherm. From the mathematical fits, the stoichiometric coefficients (n), defined as the molar ratio between host and guest, the association constants (K), and the standard enthalpy changes (ΔHº) were determined. The standard Gibbs free energy values (ΔGº) and entropy terms (TΔSº) were calculated using the fundamental thermodynamic equations (1) and (2).

3. Results and Discussion

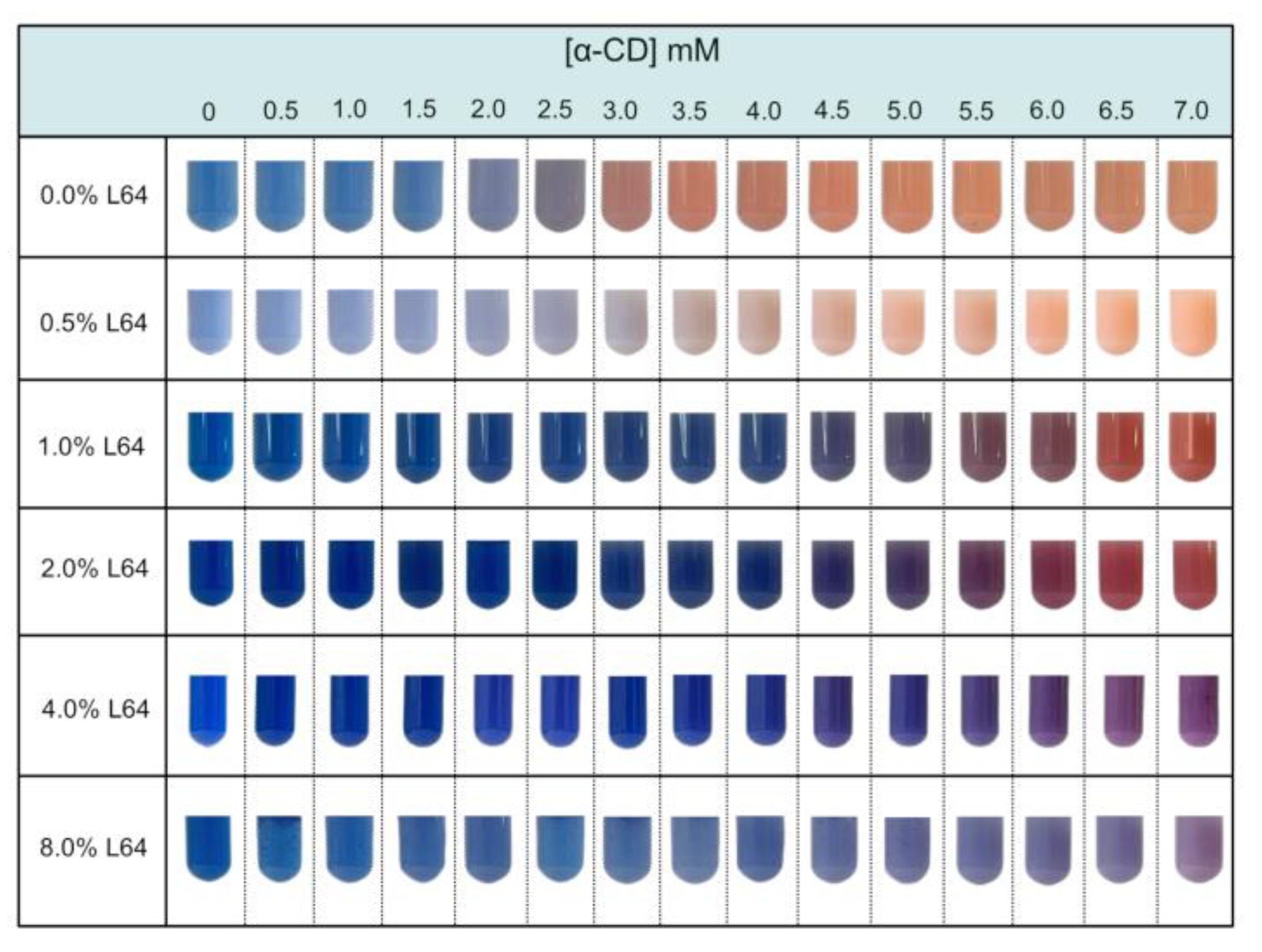

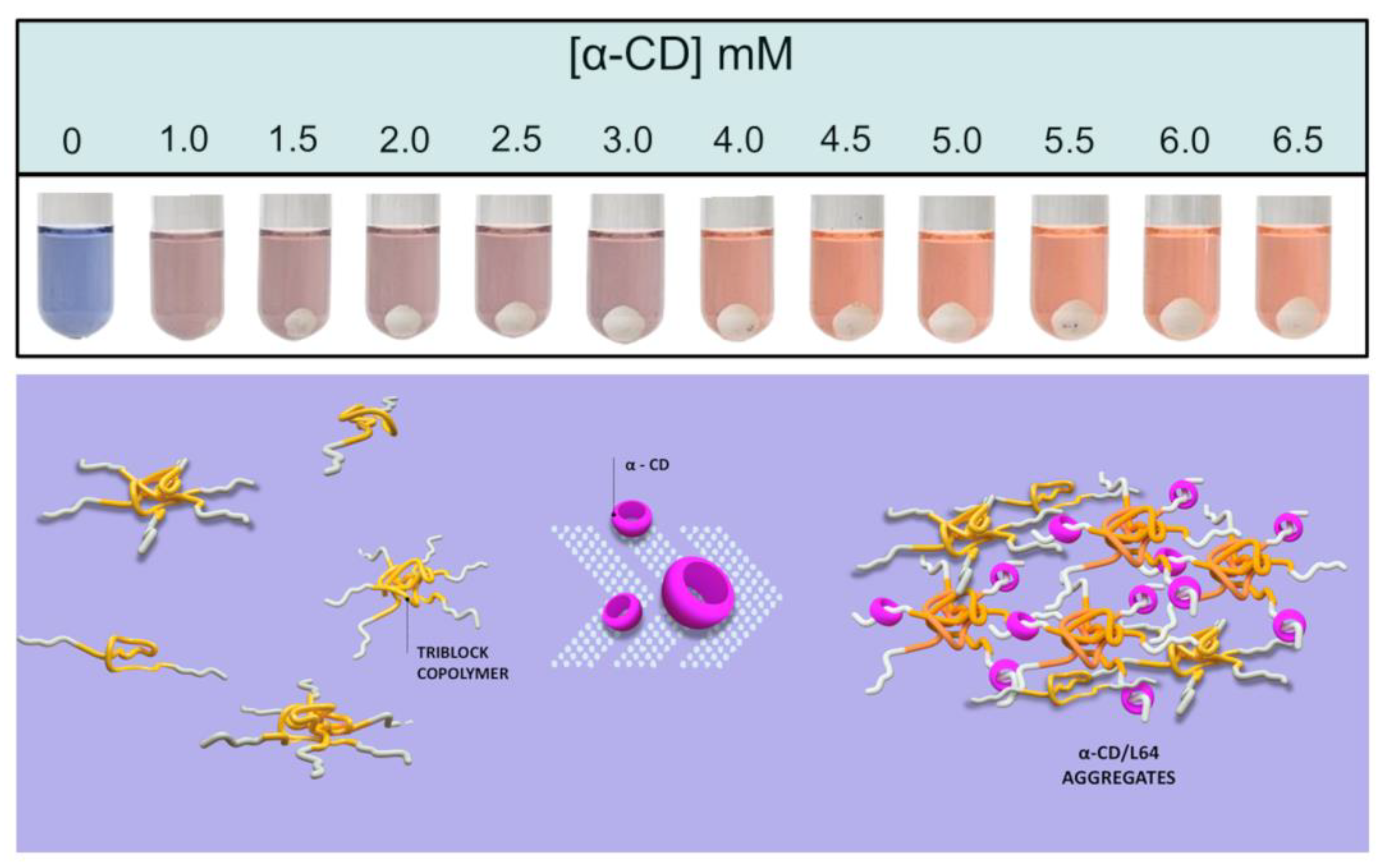

Figure 1A presents photographs of the suspensions containing PDA vesicles, as well as mixtures of PDA vesicles prepared in solutions with different concentrations of L64. The test tubes containing variable concentrations of α-CD, added to the original blue suspensions, are also shown. It is evident that increasing the α-CD concentration induces a colorimetric transition, with the suspensions changing from blue to purple and eventually to red. Visually, it is also clear that this transition is progressively inhibited as the copolymer (L64) concentration increases. For example, in suspensions prepared with 8.0% (w/w) L64, the colorimetric transition (from blue to red) is not complete observed, even at the highest α-CD concentration (7.0 mmol L⁻¹) tested.

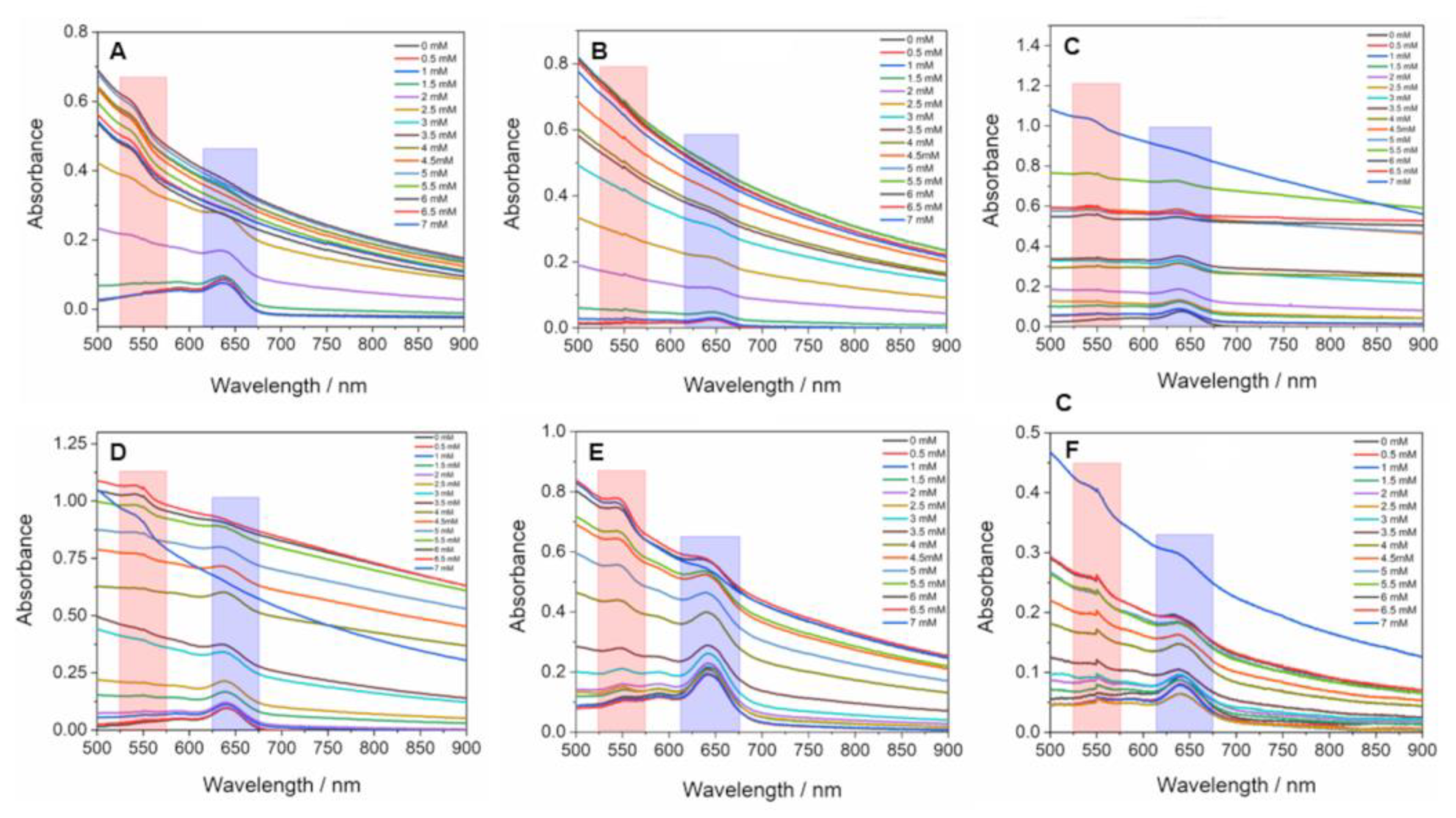

The electronic spectra of PDA vesicles and PDA/L64 mixtures are identical in the visible region, showing two maxima centered at approximately 640 and 590 nm. Both also exhibit the same spectrum when the full colorimetric transition occurs, with maximum at approximately 490 and 540 nm. Therefore, as the colorimetric transition occurs gradually, its extent can be quantified from the intensities at the maxima corresponding to the blue (640 nm) and red (540 nm) phases [

1,

2,

3]. However, the addition of α-CD not only induces the colorimetric transition in PDA vesicles but also promotes the aggregation of the L64 copolymer chains, as will be discussed later. As a result, the suspensions exhibit strong light scattering along the optical path, which compromises the accuracy of the colorimetric response (CR%) measurements obtained by UV–Vis spectrophotometry. The absorption spectra of all suspensions are shown in

Figure A1 (

Appendix A), where a noticeable elevation of the non-flat baseline, as well as peak broadening and loss of definition, can be observed.

To address this limitation and enable a quantitative analysis of the colorimetric response (CR%), variations in the RGB coordinates extracted from photographs were monitored using ImageJ® software.

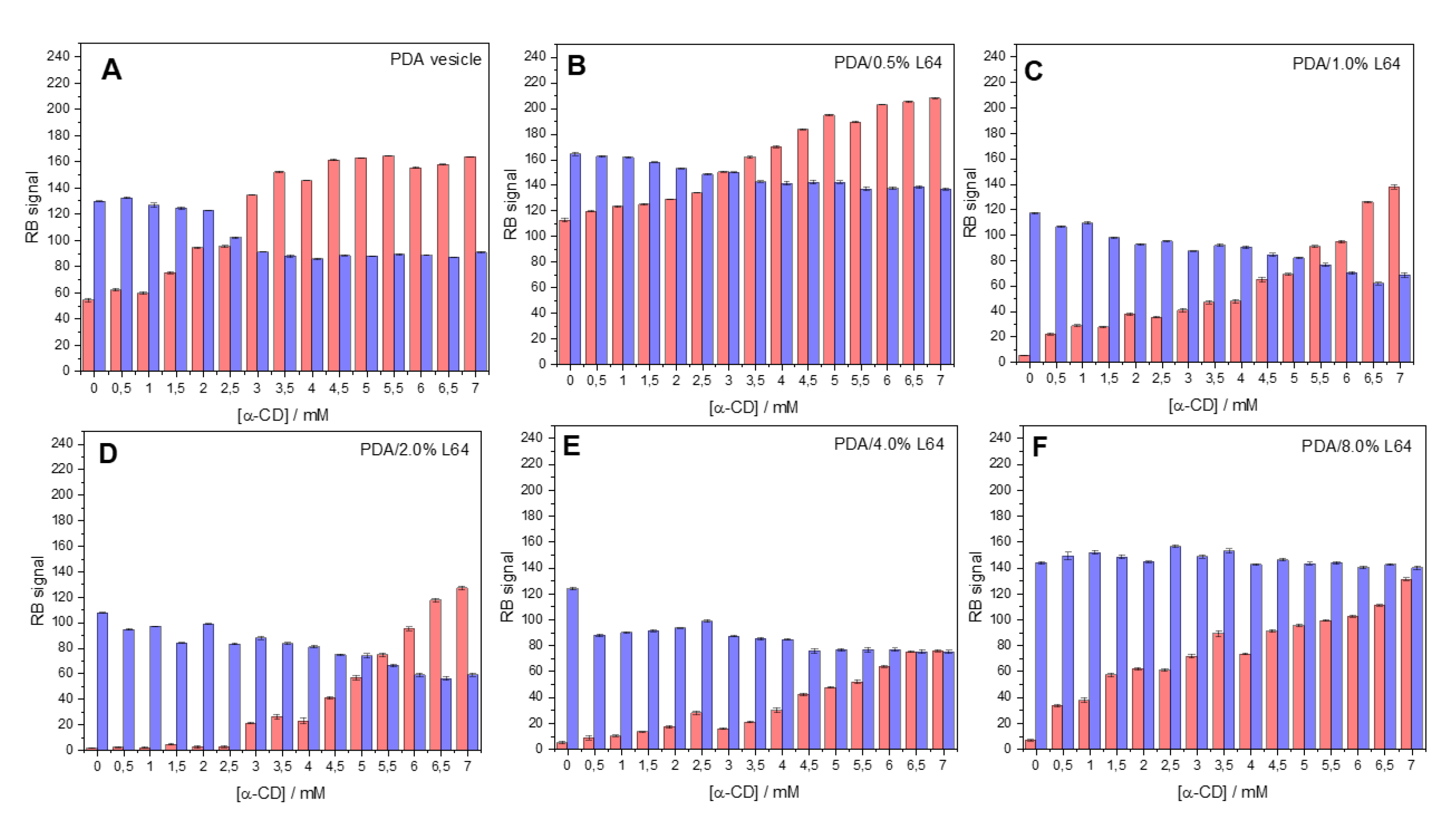

Figure 2 shows the changes in the GB signals upon the addition of α-CD to the PDA and PDA/L64 vesicle suspensions. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

The PDA vesicles exhibited the highest sensitivity toward α-CD addition. The intensity of the red pixel signal surpassed that of the blue one when the α-CD concentration reached 3.0 mM. In the PDA/0.5% L64, PDA/1.0% L64, and PDA/2.0% L64 suspensions, this inversion occurred at higher concentrations: 3.5, 5.5, and 5.5 mM, respectively. For the PDA/4.0% L64 and PDA/8.0% L64 suspensions, the inversion in the relative blue and red signal intensities was not observed up to the highest α-CD concentration studied (7.0 mM), where both signals became comparable. This behavior is consistent with the purple coloration observed in the corresponding samples.

To understand the inhibitory effect of L64 addition to the suspensions, it is essential to consider the structure and properties of the triblock copolymers and their interaction with α-CD [

33,

34]. These copolymers are amphiphilic macromolecules that self-assemble in aqueous media to form micelles featuring a hydrophobic core composed of PO segments and a hydrophilic shell formed by EO units [

35,

36]. Moreover, the L64 copolymer can also self-associate below its critical micelle concentration (CMC), forming small, short-lived oligomers [

37].

The interaction between cyclodextrins (CDs) and EO–PO–EO triblock copolymers has been previously investigated by Pradal et al., particularly focusing on the viscoelastic properties of the resulting hydrogel [

38]. The association between these molecules leads to the formation of inclusion complexes that assemble into supramolecular structures known as pseudopolyrotaxanes. This process occurs because of the size compatibility between the polymer cross-section and the internal cavity diameter of α- or β-CD, but not γ-CD. Moreover, it is well established that β-CD preferentially forms inclusion complexes with the hydrophobic PO segments [

39], whereas α-CD selectively interacts with the hydrophilic EO segments [

40].

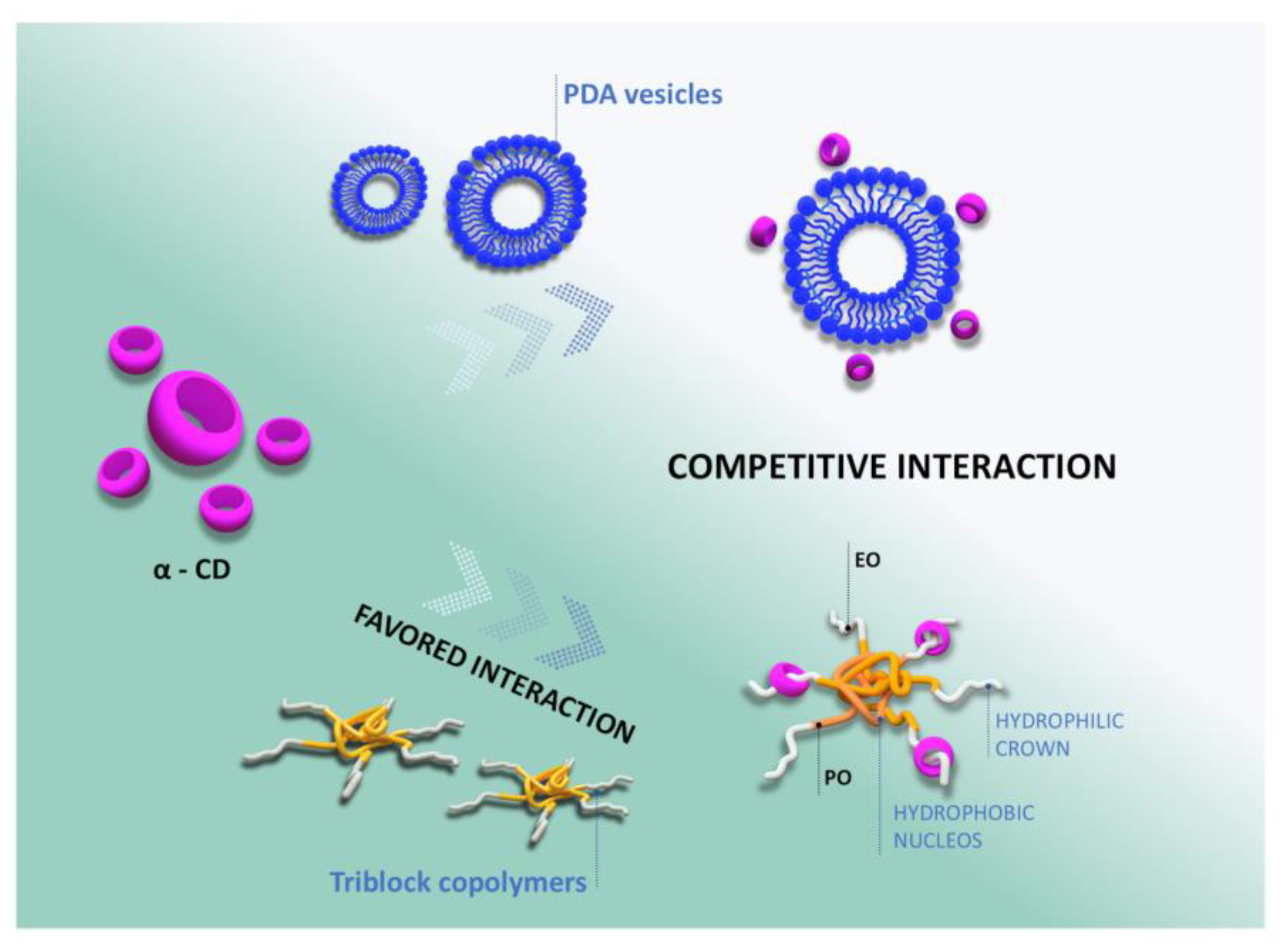

Therefore, in the PDA/L64 mixtures, α-CD molecules encounter two competing chemical environments for inclusion complex formation. In PDA vesicles, the hydrophilic headgroups containing acidic moieties can be included in the host cavity, inducing conformational rearrangements in the monomers that constitute the nanostructure and consequently triggering the color transition. Upon the addition of the copolymer, however, the EO segments can compete with PDA for the inclusion complex formation.

Figure 3 provides a schematic representation of these two possible inclusion pathways.

Based on the chromatic transition inhibition results, it can be inferred that the inclusion of the EO segments of the copolymer is thermodynamically more favorable than that of the PDA monomers. This preference arises because the inner cavity of α-CD is hydrophobic, and the EO segments (–CH₂CH₂O–) are comparatively more hydrophobic than the PDA monomer segments containing acidic groups (–CH₂CH₂COOH), which can establish strong hydrogen bonds with surrounding water molecules. In this sense, the thermodynamic parameters for the supramolecular interaction between α-CD with L64 and α-CD with PDA vesicles were investigated by ITC.

Table 1 describes the thermodynamic data for both supramolecular systems.

At 298.15 K, both systems exhibit negative standard Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG° ≈ –21.78 kJ mol⁻¹ for α-CD/L64 and –21.54 kJ mol⁻¹ for α-CD/PDA), indicating spontaneous complexation under the experimental conditions. However, the binding constant for α-CD/L64 (K ≈ 11,300 ± 1,250) exceeds that for α-CD/PDA (K ≈ 4,000 ± 353), suggesting a markedly stronger affinity of α-CD for the L64 copolymer. The K values are comparable to those reported for other supramolecular systems involving surfactants [

41].

Interestingly, both systems display only marginally exothermic enthalpy changes (ΔH° = –0.73 kJ mol⁻¹ and –0.94 kJ mol⁻¹ for α-CD/L64 and α-CD/PDA, respectively), accompanied by substantial positive entropy contributions (TΔS° ≈ +21.05 kJ mol⁻¹ for α-CD/L64 and +19.60 kJ mol⁻¹ for α-CD/PDA). From a thermodynamic standpoint, this indicates that while enthalpic contributions are nearly negligible, the driving force for complexation is dominated by entropic gain, most plausibly arising from the release of water molecules structured around hydrophobic moieties, and possibly from multiple supramolecular configurations coexisting in solution [

38].

For the α-CD/L64 system, the significantly larger binding constant points to an optimal alignment of inclusion geometry and binding-site accessibility. The central polypropylene oxide (PPO) block of L64 is flanked by polyethylene oxide (PEO) segments [

38], and α-CD can thread and stack along the PEO chains, forming “molecular necklace” structures. Incorporation of the PPO block may create hydrophobic–hydrophilic transitions that further favor α-CD inclusion. The higher K suggests that α-CD not only engages with the PEO domains but may also interact at the hydrophilic–hydrophobic interface of L64 in either micellar or non-micellar form. By contrast, in the α-CD/PDA vesicle system, the lower K and similar thermodynamic signature indicate a less favorable or less accessible binding environment, as the vesicular architecture of PDA may sterically hinder α-CD access to the hydrophobic domains.

Taken together, the thermodynamic profiles of both systems strongly suggest that α-CD complexation is entropy-driven and weakly exothermic, but that the microenvironment and polymer architecture are crucial. The L64 system provides a dynamic, accessible hydrophilic–hydrophobic interface (and sufficient PEO segment length) to enable stronger binding, whereas the PDA vesicles impose a more constrained guest environment, limiting the magnitude of the entropic gain.

As previously discussed, the addition of α-CD increases the turbidity of the solution, which can be explained by the formation of α-CD/L64 inclusion complexes. The incorporation of EO segments into the hydrophobic cavities of α-CD promotes aggregation or interpenetration of oligomers and micelles, consequently favoring phase separation. To evaluate this effect, tubes containing 0.5 wt% L64 were centrifuged after the addition of different α-CD concentrations.

Figure 4 shows images of the tubes after centrifugation, where the formation of a white precipitate at the bottom, corresponding to the α-CD–L64 complex, becomes increasingly evident with higher α-CD concentrations. In the absence of α-CD, no sediment was observed.

It is also important to emphasize that the PDA-containing phase did not collapse under the applied centrifugation conditions. This observation suggests that during the self-assembly of the diacetylene monomers, PDA vesicles are not organized over L64 chains and are therefore not structurally connected. If such association had occurred, the precipitation of the copolymer would have left a clear supernatant. From a technological perspective, this structural independence is particularly advantageous. It ensures that the sedimentation of L64 upon α-CD addition or during analyte exposure does not interfere with the PDA vesicular phase responsible for the chromatic response. In other words, the optical functionality of the PDA domain remains intact, even when the copolymer undergoes phase separation.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates, for the first time, that L64 triblock copolymer can act as effective inhibitors of the affinity-chromism of PDA vesicles in the presence of α-CD. The colorimetric response was progressively suppressed as the L64 concentration increased. RGB-based image analysis confirmed that complete blue-to-red transitions occurred only in pure PDA suspensions and in those containing up to 2.0 wt% L64, whereas mixtures with ≥4.0 wt% L64 exhibited limited conversion, even at high α-CD concentrations.

Thermodynamic analysis by ITC revealed that α-CD interacts more strongly with the L64 copolymer (K ≈ 11,300) than with PDA vesicles (K = 4,000), with both complexation processes being spontaneous (ΔG° = –21 kJ mol⁻¹) and predominantly entropy-driven. The higher affinity of α-CD for L64 arises from the favorable alignment and accessibility of its EO segments, which compete with PDA headgroups for host–guest interactions. In addition, centrifugation experiments confirmed the formation of α-CD/L64 inclusion aggregates and phase separation without collapse of the PDA phase. This structural independence between the optical and copolymer domains ensures that the chromatic sensing function of the PDA vesicles remains intact.

Finally, these findings reveal a new supramolecular strategy for controlling the chromatic response of PDA-based sensors through competitive complexation with biocompatible triblock copolymers. The ability to modulate colorimetric transitions without compromising structural integrity opens promising perspectives for the development of tunable and safe chromatic materials for biosensing, environmental monitoring, and smart packaging applications. This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Author Contributions

M.C.O.R: methodology, formal analysis, investigation; M.E.F.R.A.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation; A.R.M.A.: investigation, formal analysis, data curation; D.C.M.: investigation, formal analysis, data curation; F.B.S.: supervision, conceptualization, funding acquisition; G.A.S.J.: conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, writing—review and editing; J.P.C.T.: data curation, writing—original draft preparation, supervision, funding acquisition, project administration, writing—review and editing; P.F.R.O.: data curation, writing—original draft preparation, supervision, funding acquisition, project administration, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The CONSELHO NACIONAL DE DESENVOLVIMENTO CIENTÍFICO E TECNOLÓGICO - CNPq, grant number 407585/2023-0 and The FUNDAÇÃO DE AMPARO À PESQUISA DO ESTADO DE MINAS GERAIS – FAPEMIG, grant numbers APQ-01211-24, APQ-01313-24, APQ-03785-25, APQ-04537-22, RED-00045-23, RED-00200-23, APQ-00144-24, and APQ-00076-25.

Data Availability Statement

The data adopted in support of the findings in this work are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

J.P.C Trigueiro and F.B Sousa are a recipient of a fellowship from CNPq (grant number 303712/2025-2 and 303311/2024-0, respectively). M.C.O.R. and M.E.F.R.A. are grateful to FAPEMIG and CNPq for the scholarships granted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PDAs |

Polydiacetylenes |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| EO |

Ethylene oxide |

| PO |

Propylene oxide |

| CD |

Cyclodextrin |

| ICs |

Inclusion complexes |

| L64 |

Poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(propylene glycol)-block-poly(ethylene glycol) |

| MW |

Molecular weight |

| PCDA |

10,12-pentacosadiynoic acid |

| RGB |

Red–Green–Blue color model |

| ROIs |

Regions of interest |

| UV–Vis |

Ultraviolet–Visible spectroscopy |

| ITC |

Isothermal titration calorimetry |

| n |

Stoichiometric coefficients |

| K |

Association constant |

| VP-ITC |

Variable-Pressure Isothermal Titration Calorimeter |

| CR |

Colorimetric response |

| CMC |

Critical micelle concentration |

| PPO |

Polypropylene oxide |

| PEO |

Polyethylene oxide |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Figure A1.

UV–vis spectra of PDA vesicles (A) and PDA/L64 mixtures with 0.5 (B), 1.0 (C), 2.0 (D) 4.0 (E) and 8.0 (F) % w/w.

Figure A1.

UV–vis spectra of PDA vesicles (A) and PDA/L64 mixtures with 0.5 (B), 1.0 (C), 2.0 (D) 4.0 (E) and 8.0 (F) % w/w.

References

- Ortega, P.F.R.; Galvao, B.R.L.; de Oliveira, P.S.C.; Bastos, G.A.A.; Bernardes, M.R.F.; Lavall, R.L.; Trigueiro, J.P.C. Thermochromism in Polydiacetylene/Poly(vinyl alcohol) Hydrogels Obtained by the Freeze-Thaw Method: A Theoretical and Experimental Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 13243–13252.

- Huo, J.; Hu, Z.; He, G.; Hong, X.; Yang, Z.; Luo, S.; Ye, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Fan, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, D. High temperature thermochromic polydiacetylenes: Design and colorimetric properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 423, 951–956. [CrossRef]

- Wilk-Kozubek, M.; Potaniec, B.; Gazinska, P.; Cybinska, J. Exploring the Origins of Low-Temperature Thermochromism in Polydiacetylenes. Polymers 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Jayaraman, N. Visual Detection of pH and Biomolecular Interactions at Micromolar Concentrations Aided by a Trivalent Diacetylene-Based Vesicle. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2017, 218. [CrossRef]

- Beliktay, G.; Shaikh, T.; Koca, E.; Cingil, H.E. Effect of UV Irradiation Time and Headgroup Interactions on the Reversible Colorimetric pH Response of Polydiacetylene Assemblies. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 37213–37224.

- Weston, M.; Tjandra, A.D.; Chandrawati, R. Tuning chromatic response, sensitivity, and specificity of polydiacetylene-based sensors. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 166–183. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Moon, D.; Park, J.H.; Yang, H.; Cho, S.; Park, T.H.; Ahn, D.J. Visual detection of odorant geraniol enabled by integration of a human olfactory receptor into polydiacetylene/lipid nano-assembly. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 7582–7587. [CrossRef]

- Charych, D.; Nagy, J.; Spevak, W.; Bednarski, M. Direct colorimetric detection of a receptor-ligand interaction by a polymerized bilayer assembly. Science 1993, 261, 585–588. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Woo, S.; Ahn, D.; Ahn, K.; Lee, H.; Kim, J. Cyclodextrin-induced color changes in polymerized diacetylene Langmuir-Schaefer films. Chem. Lett. 2003, 32, 282–283. [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.; Hosoi, Y.; Furukawa, Y. Raman spectra of Langmuir-Blodgett and Langmuir-Schaefer films of polydiacetylene prepared from 10,12-pentacosadiynoic acid. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 444, 328–332. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, E.; Hug, P.; Keller, B. Chromatic transitions in polydiacetylene Langmuir-Blodgett films due to molecular recognition at the film surface studied by spectroscopic methods and surface analysis. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2002, 203, 2422–2431. [CrossRef]

- Iimori, Y.; Onodera, T.; Kasai, H.; Mitsuishi, M.; Miyashita, T.; Oikawa, H. Fabrication of pseudo single crystalline thin films composed of polydiacetylene nanofibers and their optical properties. Opt. Mater. Express 2017, 7, 2218–2223.

- Velarde, M.G.; Chetverikov, A.P.; Ebeling, W.; Wilson, E.G.; Donovan, K.J. On the electron transport in polydiacetylene crystals and derivatives. EPL 2014, 106.

- Lebegue, E.; Farre, C.; Jose, C.; Saulnier, J.; Lagarde, F.; Chevalier, Y.; Chaix, C.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. Responsive Polydiacetylene Vesicles for Biosensing Microorganisms. Sensors 2018, 18. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.S.; Finney, T.J.; Ilagan, E.; Frank, S.; Chen-Izu, Y.; Suga, K.; Kuhl, T.L. Fluorogenic Biosensing with Tunable Polydiacetylene Vesicles. Biosensors 2025, 15.

- Yu, Z.; MuYu, C.; Xu, H.; Zhao, J.; Yang, G. Recent progress in the design of conjugated polydiacetylenes with reversible thermochromic performance: a review. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 2266–2290. [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, R.; Ritenberg, M. Polydiacetylenes – recent molecular advances and applications. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 21192–21201. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Oveissi, F.; Chandrawati, R.; Dehghani, F.; Naficy, S. Naked-Eye Detection of Ethylene Using Thiol-Functionalized Polydiacetylene-Based Flexible Sensors. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 1921–1928. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, L.; Zhu, L.; Chen, D. Selective detection of metal ions based on nanocrystalline ionochromic polydiacetylene. Polymer 2013, 54, 743–749. [CrossRef]

- Tjandra, A.D.; Chandrawati, R. Polydiacetylene/copolymer sensors to detect lung cancer breath volatile organic compounds. RSC Appl. Polym. 2024, 2, 1043–1056.

- Jang, H.; Jeon, J.; Shin, M.; Kang, G.; Ryu, H.; Kim, S.M.; Jeon, T.-J. Polydiacetylene (PDA) Embedded Polymer-Based Network Structure for Biosensor Applications. Gels 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Dias Ferreira, G.M.; Dias Ferreira, G.M.; Hespanhol, M.C.; Rezende, J.P.; Pires, A.C.S.; Ortega, P.F.R.; Mendes da Silva, L.H. A simple and inexpensive thermal optic nanosensor formed by triblock copolymer and polydiacetylene mixture. Food Chem. 2018, 241, 358–363. [CrossRef]

- Morais, D.C.; Vieira, B.B.M.; Carvalho, M.C.; Miguez, F.B.; Lopes, J.F.; Sousa, F.B.D. Thermodynamic investigation of biperiden hydrochloride and cyclodextrins supramolecular systems. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2024, 851. [CrossRef]

- Passos, J.J.; De Sousa, F.B.; Mundim, I.M.; Bonfim, R.R.; Melo, R.; Viana, A.F.; Stolz, E.D.; Borsoi, M.; Rates, S.M.K.; Sinisterra, R.D. Double continuous injection preparation method of cyclodextrin inclusion compounds by spray drying. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 228, 345–351. [CrossRef]

- Passos, J.J.; De Sousa, F.B.; Mundim, I.M.; Bonfim, R.R.; Melo, R.; Viana, A.F.; Stolz, E.D.; Borsoi, M.; Rates, S.M.K.; Sinisterra, R.D. In vivo evaluation of the highly soluble oral β-cyclodextrin–Sertraline supramolecular complexes. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 436, 478–485. [CrossRef]

- Utzeri, G.; Matias, P.M.C.; Murtinho, D.; Valente, A.J.M. Cyclodextrin-Based Nanosponges: Overview and Opportunities. Front. Chem. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Roy, I.; Stoddart, J.F. Cyclodextrin Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1440–1453.

- Valente, A.J.M.; Soderman, O. The formation of host–guest complexes between surfactants and cyclodextrins. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 205, 156–176.

- Champaiboon, T.; Tumcharern, G.; Potisatityuenyong, A.; Wacharasindhu, S.; Sukwattanasinitt, M. A polydiacetylene multilayer film for naked eye detection of aromatic compounds. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 139, 532–537. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; Ballesteros, S.; Almarza, E.; de la Torre, C.; Búa, S. Acute nitrobenzene poisoning with severe associated methemoglobinemia: Identification in whole blood by GC-FID and GC-MS. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2003, 27, 221–225.

- Tchieno, F.M.M.; Tonle, I.K. p-Nitrophenol determination and remediation: an overview. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018, 37. [CrossRef]

- de Castro, K.C.; Coco, J.C.; dos Santos, E.M.; Ataide, J.A.; Martinez, R.M.; Monteiro do Nascimento, M.H.; Prata, J.; Lopes da Fonte, P.R.M.; Severino, P.; Mazzola, P.G.; Baby, A.R.; Souto, E.B.; de Araujo, D.R.; Lopes, A.M. Pluronic® triblock copolymer-based nanoformulations for cancer therapy: A 10-year overview. J. Control. Release 2023, 353, 802–822.

- Liu, D.; Yang, M.; Wang, D.; Jing, X.; Lin, Y.; Feng, L.; Duan, X. DPD Study on the Interfacial Properties of PEO/PEO-PPO-PEO/PPO Ternary Blends: Effects of Pluronic Structure and Concentration. Polymers 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.; Klein, C.; Topchieva, I.; Köhler, G. Selective assembly of cyclodextrins on poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide) block copolymers. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 1999, 13, 373–383.

- Almgren, M.; Brown, W.; Hvidt, S. Self-aggregation and phase-behavior of poly(ethylene oxide) poly(propylene oxide) poly(ethylene oxide) block-copolymers in aqueous solution. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1995, 273, 2–15.

- Mata, J.; Majhi, P.; Guo, C.; Liu, H.; Bahadur, P. Concentration, temperature, and salt-induced micellization of a triblock copolymer Pluronic L64 in aqueous media. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 292, 548–556. [CrossRef]

- Marinov, G.; Michels, B.; Zana, R. Study of the state of the triblock copolymer poly(ethylene oxide) poly(propylene oxide) poly(ethylene oxide) L64 in aqueous solution. Langmuir 1998, 14, 2639–2644. [CrossRef]

- Pradal, C.; Jack, K.S.; Grondahl, L.; Cooper-White, J.J. Gelation kinetics and viscoelastic properties of Pluronic and α-cyclodextrin-based pseudopolyrotaxane hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3780–3792.

- Tsai, C.-C.; Zhang, W.-B.; Wang, C.-L.; Van Horn, R.M.; Graham, M.J.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Guo, M.; Cheng, S.Z.D. Evidence of formation of site-selective inclusion complexation between β-cyclodextrin and poly(ethylene oxide)-block-poly(propylene oxide)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) copolymers. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132.

- Yang, C.; Ni, X.; Li, J. Synthesis of polyrotaxanes consisting of multiple α-cyclodextrin rings threaded on reverse Pluronic PPO-PEO-PPO triblock copolymers based on block-selected inclusion complexation. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 1570–1579. [CrossRef]

- Meira, L.H.R.; Soares, G.A.B.; Bonomini, H.I.M.; Lopes, J.F.; De Sousa, F.B. Thermodynamic compatibility between cyclodextrin supramolecular complexes and surfactant. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 544, 203–212. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).