1. Introduction

Since its development, the Ozaki procedure, an autologous pericardial aortic valve reconstruction, has steadily gained recognition as a landmark innovation in aortic valve surgery. Initially conceived for younger patients to optimize valve hemodynamics and eliminate the need for prosthetic material, its indications have broadened considerably. Today, it is increasingly adopted in older and high-risk populations, offering a compelling alternative to conventional valve replacement thanks to its excellent mid-term outcomes, native-like valve dynamics, and the absence of prosthetic-related complications. Among the potential drawbacks, infective endocarditis (IE) remains the most serious and life-threatening complication of this technique. Although rare, IE carries a significant clinical burden and frequently necessitates complex reintervention in hostile anatomical environments. In a recent large single-center series from Toho University Ohashi Medical Center (2025), Fujikawa-Osaki et al. identified 40 reoperations due to endocarditis among 1,333 patients treated with the Ozaki procedure, yielding an incidence of 0.45% per patient-year [

1]. This underscores both the rarity and clinical gravity of such a complication. Concurrently, the emergence of sutureless valve technology, particularly the Perceval Sutureless bioprosthesis (Corcym, Saluggia, Italia), has reshaped the approach to complex aortic valve reoperations [

2]. As noted by Elgharaby et al. [

3], the Perceval valve is being increasingly utilized in endocarditis settings, particularly in cases involving degenerated or infected prosthetic valves. Thanks to its inherent advantages including shortened cross-clamp time, streamlined deployment, and minimal annular manipulation, make it particularly valuable in fragile, inflamed, or infected tissue beds, where conventional suturing techniques risk paravalvular leakage or annular injury.

We present the first-in-man case of Perceval valve implantation as a bail-out solution for infective endocarditis following prior Ozaki reconstruction in a critically ill patient. This unique scenario highlights the potential synergy between two innovative techniques and expands therapeutic options for managing complex infective aortic pathology in the re-operative setting.

2. Case report

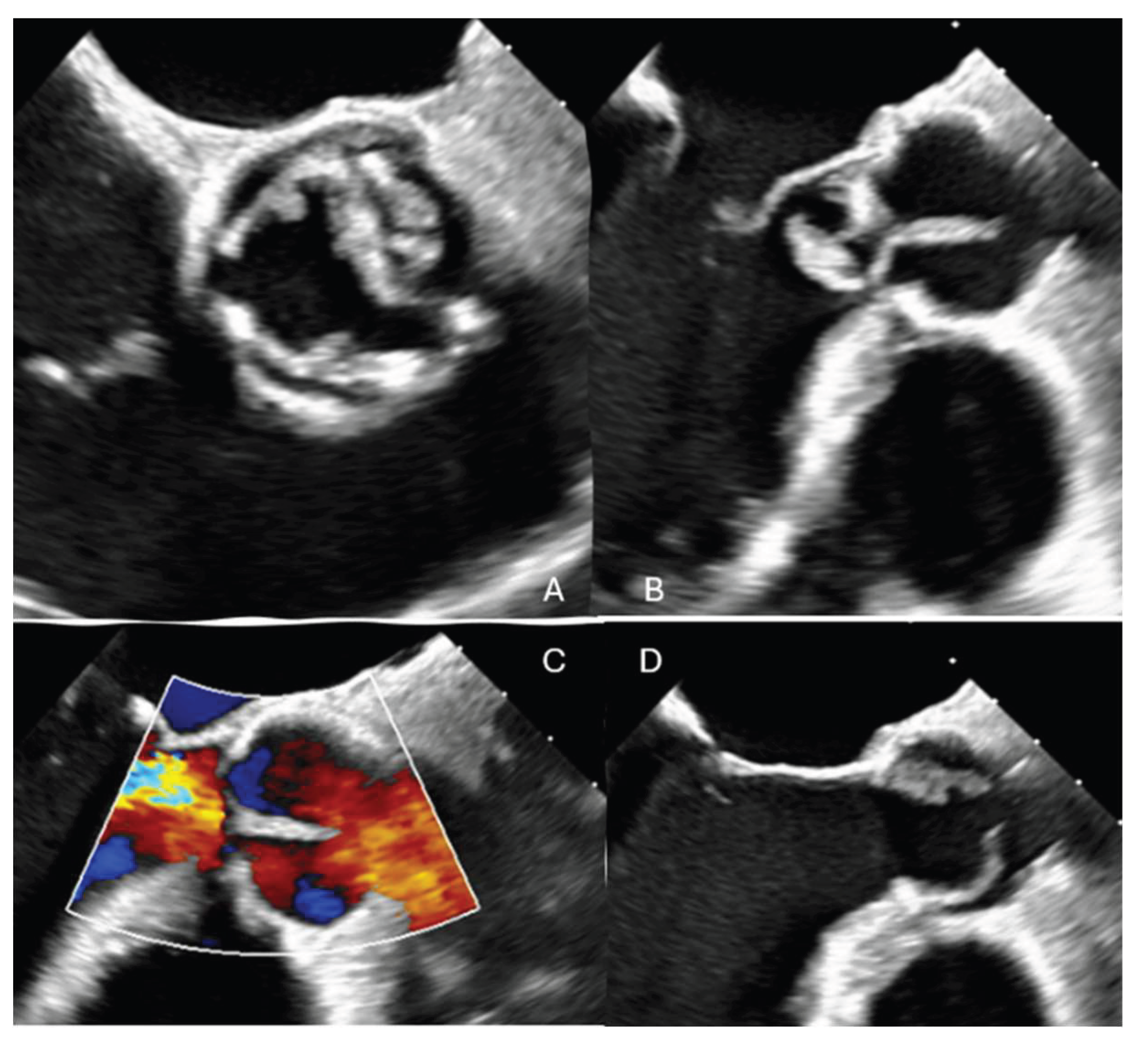

A 68-year-old male with a previous surgical history of Ozaki aortic valve reconstruction and LIMA-LAD coronary artery bypass grafting in 2023 for bicuspid aortic valve disease presented with acute decompensated heart failure. Blood cultures yielded Streptococcus bovis, and transesophageal echocardiography (TOE) revealed torrential aortic regurgitation due to destruction of the anterior neocuspidal leaflet, with associated large, mobile vegetations. (

Figure 1)

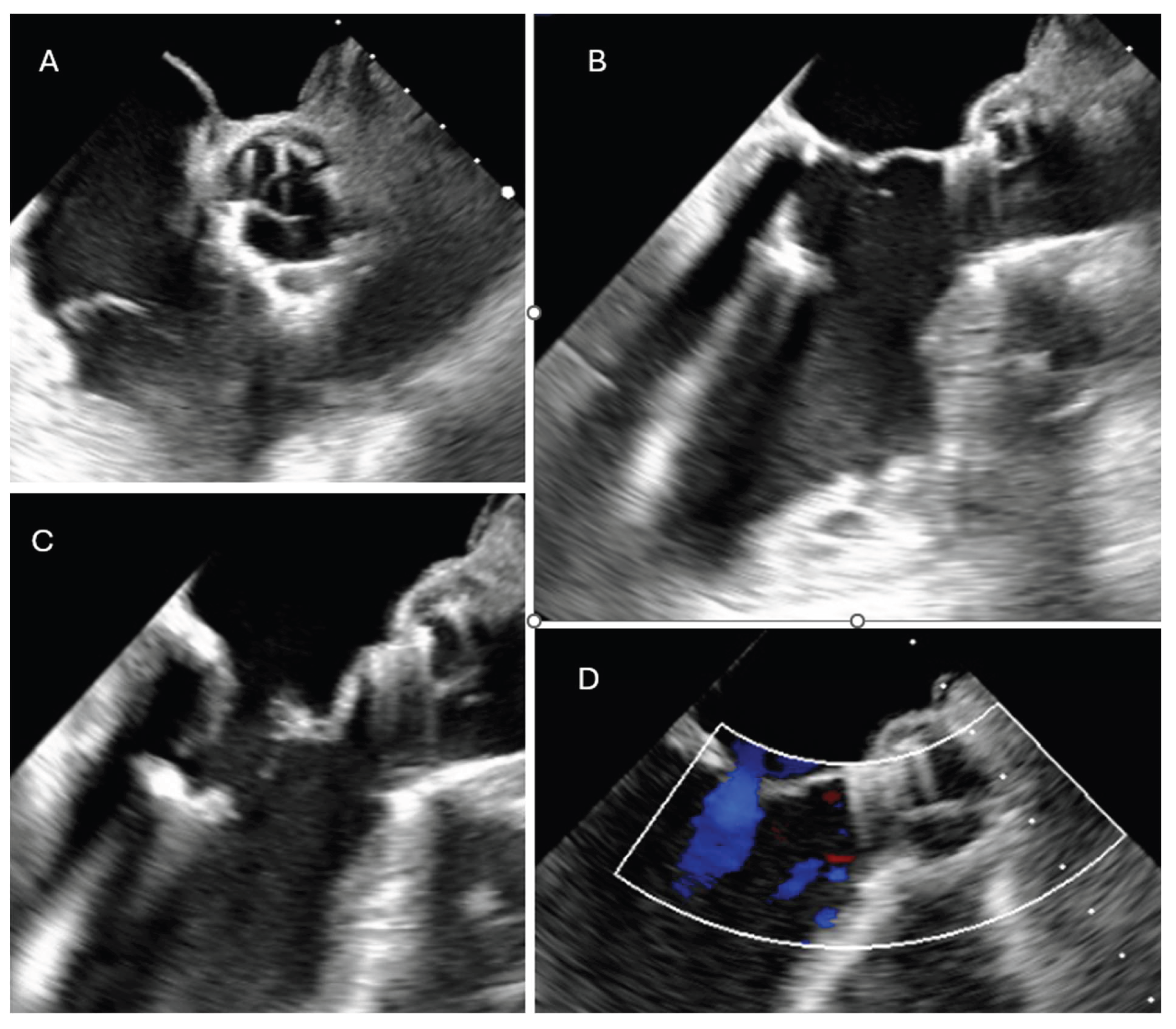

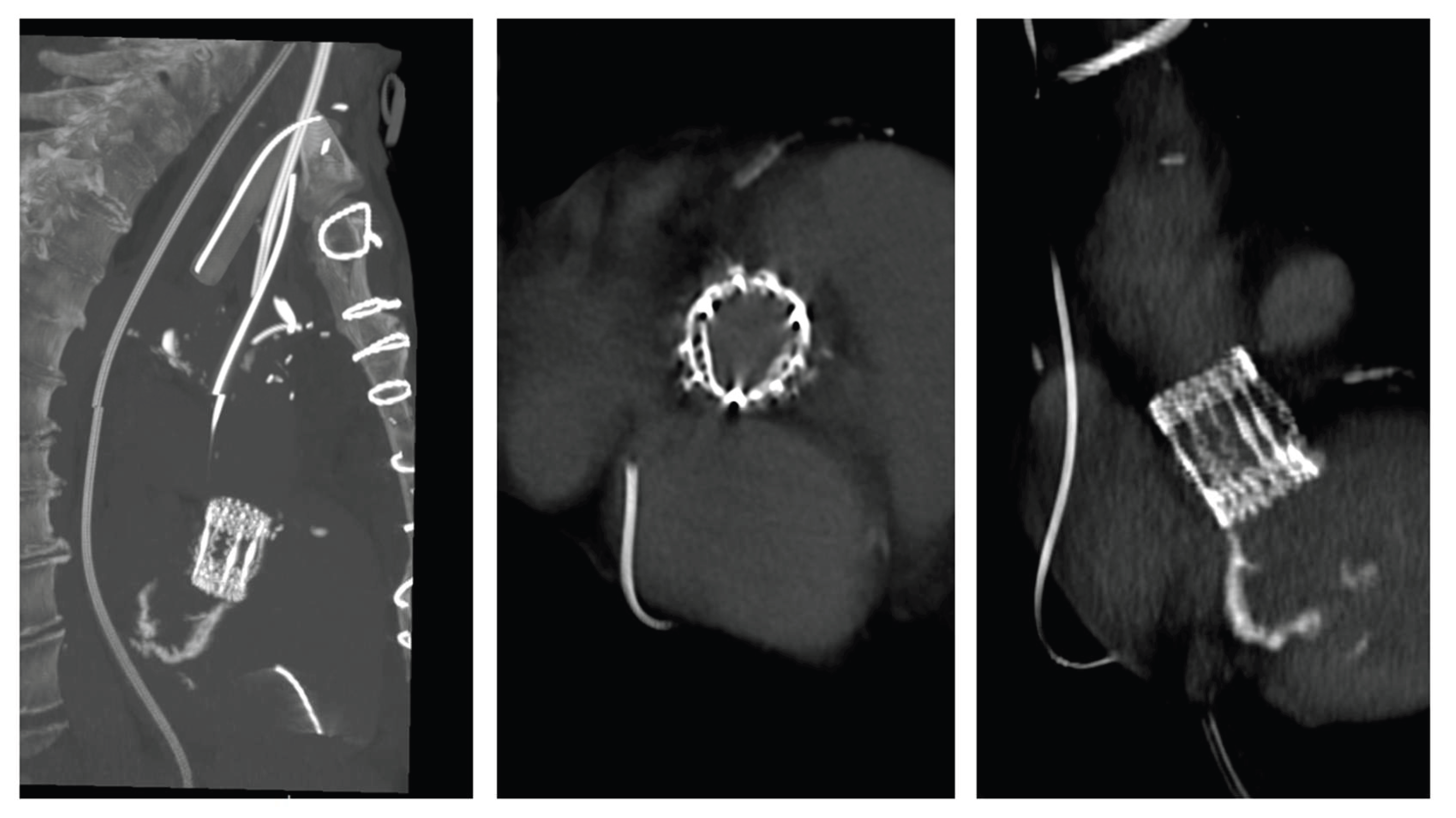

The patient experienced rapid clinical deterioration, progressing to multiorgan failure characterized by septic and cardiogenic shock, acute hepatic dysfunction (shock liver), acute renal failure, septic encephalopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and new-onset atrial flutter. Despite a calculated in-hospital mortality risk of 89.5% based on the EuroSCORE II, the severity of the clinical scenario mandated immediate salvage surgery. A redo median sternotomy was undertaken in a technically complex setting, complicated by the absence of the pericardium and dense mediastinal adhesions from the previous surgery. Careful and meticulous dissection allowed for the safe identification of the great vessels. Central cannulation was achieved via the aortic arch for arterial return and bicaval venous access for drainage. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was initiated under normothermic conditions, ensuring adequate systemic perfusion. The aorta was cross-clamped, and a transverse aortotomy was performed. Myocardial protection was provided through the administration of cold blood cardioplegia directly into the coronary ostia, with repeated doses to maintain optimal myocardial preservation throughout the procedure. Intraoperative exploration revealed extensive destruction: the left neocuspidal leaflet was completely perforated, and a large, highly mobile vegetation was found on the ventricular aspect of the valve. Furthermore, a sub- annular abscess was identified, extending from the left–right commissure into both the left and right sinuses of Valsalva. Radical debridement of all infected and necrotic tissue was undertaken, with evacuation of purulent material. The abscess cavity was meticulously excised until only macroscopically healthy tissue remained. The resulting defect, involving the annular region and extending approximately one centimeter into both sinuses, was reconstructed using two layers of continuous 4-0 Prolene sutures. Given the fragility of the annular tissue and the extensive debridement required, the use of a conventional sutured bioprosthesis was deemed inadvisable. A medium-sized Perceval sutureless bioprosthetic valve was therefore selected and deployed successfully. The aortotomy was closed using the Blalock technique with two layers of 5-0 Prolene sutures. Weaning from CBP proved challenging due to biventricular dysfunction in the context of preoperative multiorgan failure. As a result, femoro-femoral veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) was instituted intraoperatively to provide circulatory support and facilitate end-organ recovery. The total cross-clamp time was 58 minutes whilst CBP time was 125 minutes. Hemodynamic stabilization was gradually achieved, and ECMO was successfully explanted after 5 days. The patient remained in the intensive care unit for three weeks, during which progressive clinical improvement was observed. Transthoracic echocardiography performed prior to ICU discharge demonstrated normal function of the implanted Perceval valve (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), with no evidence of paravalvular leakage or residual vegetations. At three-month follow-up, the patient remained clinically stable, and repeat imaging confirmed preserved valve function without signs of recurrent endocarditis.

3. Discussion

Among the rare but serious complications of the Ozaki procedure, infective endocarditis (IE) emerges as the leading cause of reoperation. While the Ozaki technique was designed to minimize foreign material and thus reduce the risk of infection, clinical experience has not consistently confirmed this protective effect. The most comprehensive data from Toho University Ohashi Medical Center, where the procedure was first developed, report an annual IE incidence of 0.45%, with IE responsible for 89% (40/45) of reoperations in a cohort of 1,333 patients [

1]. Similar findings were echoed by Unai et al. [

4], Osaki et al. [

5], and Iida et al. [

6], who observed that IE not only persists as a risk after Ozaki, but also overwhelmingly constitutes the primary indication for reintervention. Notably, the use of autologous pericardium did not confer a reduced risk of infection compared to standard prosthetic valves like PERIMOUNT used as in the control group in the study led by Unai et al [

4].

Outside Japan, multicenter and single-institution series show variable rates of IE after the Ozaki procedure, ranging from 0% [

7,

8] to approximately 1% per year [

9]. Although some cohorts, such as those by Patel et al. and Prinzing et al. [

11], reported isolated IE cases requiring redo procedures, overall trends confirm that infective endocarditis, when it occurs, poses a significant therapeutic challenge, particularly in the context of tissue destruction, annular distortion, and fragile autologous cusps.

In this landscape, reoperation strategies remain a subject of debate, especially in patients with structural valve failure complicated by active endocarditis. Our case highlights an innovative and pragmatic solution: the use of a Perceval sutureless valve as a bailout strategy after failure of the Ozaki procedure due to IE in a high-risk surgical patient. To date, only one case has been reported of Perceval implantation following an Ozaki procedure [

12], but that case did not involve an infectious context. Our report is, to our knowledge, the first to describe successful Perceval implantation in a patient with post-Ozaki infective endocarditis.

The use of Perceval in endocarditis is increasingly documented. Several authors [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] have reported favorable outcomes with sutureless valves in high-risk endocarditis settings, including valve-in-valve and redo operations. The main arguments in favor of Perceval in these contexts include its rapid deployment, shorter cardiopulmonary bypass and cross-clamp times, and reduced need for annular suturing, particularly advantageous when native tissue is inflamed, friable, or debrided. Rosello-Diez et al. and Zubarevitch et al. emphasized its utility in cases with extensive destruction, where conventional sutured prostheses may be technically hazardous. Although perioperative mortality in these series remained significant (up to 23%), this reflects the severity of the underlying disease and the high-risk nature of the patient population rather than the limitations of the device itself.

In our case, after careful excision of infected tissue and assessment of annular integrity, Perceval implantation offered a technically safe and time-efficient solution with excellent immediate hemodynamics and no signs of recurrent infection nor paravalvular leakage at follow-up. This aligns with the broader findings from Ozgur et al. [

16], who supported Perceval’s role as a viable alternative to conventional bioprostheses in endocarditis scenarios.

Importantly, the mid-term infective risk profile of the Perceval valve compares favorably with both conventional bioprostheses and the Ozaki procedure. In a five-year follow-up study, Shrestha et al. reported an endocarditis incidence of 1.9% following Perceval implantation, corresponding to approximately 0.4% per patient-year, like the rates observed in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), where Ruchonnet et al. described an annual incidence of 0.5%. These figures are also comparable to the infective risk reported in large Ozaki series. Together, these data support the notion that sutureless valves like Perceval may serve not only as effective bail-out options in technically challenging or infected fields but also as reliable and durable solutions with an acceptable long-term infective profile.

While the Perceval sutureless valve offers distinct advantages in selected high-risk scenarios, its use is not universally applicable and carries important limitations. The prosthesis requires a relatively circular and symmetric annulus for optimal anchoring and function [

21,

22]; significant annular distortion, asymmetric calcification may compromise sealing and increase the risk of paravalvular leak or device malposition [

23,

24]. In addition, the Perceval valve is not suitable for annular diameters outside the manufacturer’s approved range (typically 19–27 mm) [

25], limiting its applicability in patients with extreme annular sizes. In cases of severe aortic root dilatation or fragile aortic wall integrity, particularly when reconstruction of the sinuses or root replacement is necessary, the device may not provide sufficient structural support or flexibility [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Finally, concerns have been raised regarding potential risks of conduction disturbances and pacemaker implantation [

30,

31], particularly in smaller annuli or heavily calcified valves. These factors should be carefully weighed during preoperative planning, and alternative strategies such as conventional sutured bioprostheses or homograft implantation, as reported for example by Komarov et al. in 2021 [

32], may be preferable in anatomically unsuitable or structurally unstable cases, at the cost of a prolonged clamping and CPB time.

3. Conclusion

Given the growing global uptake of the Ozaki procedure and the predictable, if rare, occurrence of endocarditis-related failure, the availability of a safe and efficient bailout strategy is essential. Our case supports the notion that the Perceval valve may fulfill this role, especially in patients with annular damage, calcification, or tissue friability that complicates conventional valve reimplantation.

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to the entire multidisciplinary team whose dedication made this work possible: Valentina Rancati, Florine Valliet, Anna Nowacka, Filip Dulguerov, Elsa Hoti, Margaux Wolff, Augustin Rigollot, Agnès Godat, Camille Gottignies, Pierre-Alain Hayoz

References

- Fujikawa T, Ozaki S, Kiyohara N, Goda M, Takatoo M, Shimura S. New Ozaki Procedure Overview. Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. Published online March 24, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cummings I, Salmasi MY, Bulut HI, Zientara A, AlShiekh M, Asimakopoulos G. Sutureless Biological Aortic Valve Replacement (Su-AVR) in Redo operations: a retrospective real-world experience report of clinical and echocardiographic outcomes. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24:28. [CrossRef]

- Elgharably H, Unai S, Pettersson GB. Sutureless Prosthesis for Prosthetic Aortic Valve Endocarditis: Time to Put Brakes on a Speedy Bus? The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2024;118(2):519. [CrossRef]

- Unai S, Ozaki S, Johnston DR, et al. Aortic Valve Reconstruction With Autologous Pericardium Versus a Bioprosthesis: The Ozaki Procedure in Perspective. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(2):e027391. [CrossRef]

- Ozaki S, Kawase I, Yamashita H, Uchida S, Takatoh M, Kiyohara N. Midterm outcomes after aortic valve neocuspidization with glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2018;155(6):2379-2387. [CrossRef]

- Iida Y, Fujii S, Akiyama S, Sawa S. Early and mid-term results of isolated aortic valve neocuspidization in patients with aortic stenosis. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;66(11):648-652. [CrossRef]

- Naik R, Prabhu A, Gan M, Saldanha R. Early outcomes of aortic valve neocuspidization (the Ozaki procedure): Initial experience of a single centre. Indian Heart Journal. Published online May 24, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pirola S, Mastroiacovo G, Arlati FG, et al. Single Center Five Years’ Experience of Ozaki Procedure: Midterm Follow-up. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2021;111(6):1937-1943. [CrossRef]

- Enginoev ST, Chernov II, Komarov RN, et al. Aortic Valve Reinterventions after Ozaki: Clinical Case Series from Four Centers. Креативная хирургия и oнкoлoгия. 2023;13(1):87-92. [CrossRef]

- Patel V, Unai S, Moore R, et al. The Ozaki Procedure: Standardized Protocol Adoption of a Complex Innovative Procedure. Structural Heart. 2024;8(1):100217. [CrossRef]

- Prinzing A, Boehm J, Burri M, Schreyer J, Lange R, Krane M. Midterm results after aortic valve neocuspidization. JTCVS Techniques. 2024;25:35-42. [CrossRef]

- Özçobanoğlu S, Gündüz E. Repair of severe aortic insufficiency and stenosis after Ozaki surgery with PercevalTM sutureless aortic valve. Turk Gogus Kalp Damar Cerrahisi Derg. 2023;32(4):453-456. [CrossRef]

- Konertz J, Kastrup M, Treskatsch S, Dohmen PM. A Perceval Valve in Active Infective Bioprosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Case Report. J Heart Valve Dis. 2016;25(4):512-514.

- Roselló-Díez E, Cuerpo G, Estévez F, et al. Use of the Perceval Sutureless Valve in Active Prosthetic Aortic Valve Endocarditis. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2018;105(4):1168-1174. [CrossRef]

- Zubarevich A, Rad AA, Szczechowicz M, Ruhparwar A, Weymann A. Sutureless aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with active infective endocarditis. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2022;14(9). [CrossRef]

- Ozgur MM. Sutureless aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with infective endocarditis. Cardiovasc Surg Int. 2025;12(1):41-50. [CrossRef]

- Smith HN, Fatehi Hassanabad A, Kent WDT. Novel Use of the Perceval Valve for Prosthetic Aortic Valve Endocarditis Requiring Root Replacement. Innovations�(Phila). 2022;17(1):67-69. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Q, White A, Lam W, Wang W, Wang S. Valve-in-Valve Using Perceval Prostheses for Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2022;114(6):e437-e439. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2022.02.037Ozgur MM. Sutureless aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients

with infective endocarditis. Cardiovasc Surg Int. 2025;12(1):41-50. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha M, Fischlein T, Meuris B, et al. European multicentre experience with the sutureless Perceval valve: clinical and haemodynamic outcomes up to 5 years in over 700 patients†. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2016;49(1):234-241. [CrossRef]

- Ruchonnet EP, Roumy A, Rancati V, Kirsch M. Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Complicated by Paravalvular Abscess and Treated by Pericardial Patches and Sutureless Valve Replacement. The Heart Surgery Forum. 2019;22(2):E155-E158. [CrossRef]

- Glauber M, Miceli A, di Bacco L. Sutureless and rapid deployment valves: implantation technique from A to Z—the Perceval valve. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;9(4):330-340. [CrossRef]

- Chandola R, Teoh K, Elhenawy A, Christakis G. Perceval Sutureless Valve – are Sutureless Valves Here? Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11(3):220-228. [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe J, Moten S, Tripathy A, et al. Perceval valve intermediate outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis at 5-year follow-up. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;18(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Maroto L, Rodriguez J, Cobiella J, Silva J. Delayed dislocation of a transapically implanted aortic bioprosthesis. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2009;36:935-937. [CrossRef]

- Sorin Group, PERCEVAL SUTURELESS AORTIC HEART VALVE Instructions for Use, HVV_LS-850-0002 Rev X03, 2015 Sorin Group Canada Inc., FDA. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/P150011d.pdf.

- Gersak B, Fischlein T, Folliguet TA, et al. Sutureless, rapid deployment valves and stented bioprosthesis in aortic valve replacement: recommendations of an International Expert Consensus Panel. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2016;49(3):709-718. [CrossRef]

- Concistré G, Baghai M, Santarpino G, et al. Clinical and hemodynamic outcomes of the Perceval sutureless aortic valve from a real-world registry. Interdiscip Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2023;36(6):ivad103. [CrossRef]

- Fischlein T, Folliguet T, Meuris B, et al. Sutureless versus conventional bioprostheses for aortic valve replacement in severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;161(3):920-932. [CrossRef]

- Quinn RD. The 10 Commandments of Perceval Implantation. Innovations�(Phila).2023;18(4):299-307. [CrossRef]

- Powell R, Pelletier MP, Chu MWA, Bouchard D, Melvin KN, Adams C. The Perceval Sutureless Aortic Valve: Review of Outcomes, Complications, and Future Direction. Innovations (Phila). 2017 May/Jun;12(3):155-173. PMID: 28570342. [CrossRef]

- Brookes JDL, Mathew M, Brookes EM, Jaya JS, Almeida AA, Smith JA. Predictors of Pacemaker Insertion Post-Sutureless (Perceval) Aortic Valve Implantation. Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30(6):917-921. [CrossRef]

- Komarov R, Kurasov N, Ismailbaev A, et al. Aortic homograft implantation after Ozaki procedure: Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;81:105782. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).