1. Introduction

In today’s digital world, attacks on information systems using social engineering are becoming increasingly common. These attacks attempt to deceive users into revealing confidential information, which is then used by the attacker for personal enrichment and to harm the owner of the information resource being attacked. According to the Russian company Positive Technologies [

1], the number of computer attacks in Russia increased by 26% in 2024. Social engineering-related attacks predominate among both organizations (50%) and individuals (88%). The most common social engineering attack is phishing—an attack orchestrated by an attacker to force a user to interact with an infected (phishing) website in order to extract critical credentials (logins, passwords, payment details) and inject malware into the system. According to the international working group APWG (Anti-Phishing Working Group), the number of phishing attacks against online payments and the financial (banking) sector increased significantly in the first quarter of 2025, amounting to 30.9% of the total number of attacks [

2].

There are three main methods of organizing phishing attacks [

3]:

Malicious links, which appear as impostor websites infected with malware;

Malicious file attachments, which are infected with malware to compromise the user’s computer or files;

Fraudulent data entry forms, which prompt the user to enter their login credentials or other sensitive information to log in.

Unlike previous years, when attackers required advanced technical skills, knowledge of web programming, scripting, social engineering techniques, and so on, a dedicated industry (criminal environment) called Phishing-as-a-Service (PaaS) has emerged in recent years, opening up the organization and execution of successful, highly organized phishing attacks to a wide audience of non-professional criminals. This circumstance is the reason for the rapid growth of the phishing threat and the urgent need to take extraordinary measures to neutralize it.

As noted in some studies [

4,

5,

6,

7], existing traditional methods for detecting phishing web resources, such as the use of blacklists of malicious sites and URL (Uniform Resource Locator) analysis—links to specific web pages or addresses of other web resources on the internet—cannot accurately identify phishing sites, resulting in a significant number of false positives.

So, the use of machine learning (ML) methods, such as artificial neural networks (NNs), support vector machines (SVMs), random forest (RF) algorithms, and others, is promising. These methods allow for the analysis and classification of websites based on a set of characteristic URLs associated with phishing. The solution to the problem of detecting phishing websites is reduced to the problem of binary classification of URLs in a vector feature space: determining whether a URL belongs to one of two classes—legitimate or malicious (phishing). The advantages of using machine learning methods are higher accuracy in the presence of noisy and incomplete input data, the ability to adapt in real time and retrain when the training data changes, and the ability to detect new types of phishing attacks. So they ensure greater efficiency in detecting phishing websites.

Additional advantages for solving the problem of detecting phishing websites are revealed by the emergence of modern advanced artificial intelligence (AI) technologies based on the application of deep learning methods, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), long short-term memory networks (LSTM), transformers, large language models (LLMs) [

8,

9,

10], and hybrid (multimodal) AI systems [

11,

12,

13]. A distinctive feature of this class of AI methods and systems is the use of additional information about the web resource as source code and a visual image (image) of the web page besides a set of symbolic URL features, which increases the dimensionality of the feature space under study, attracting additional expert knowledge about the structure of phishing websites at the classification stage, which ultimately increases the reliability of the decisions made. Such models can be classified as multimodal (modality refers to the type of input/output data and methods for extracting features from this data for subsequent processing in a machine learning model [

14]).

As noted in some studies, the approaches discussed above (machine and deep learning methods, multimodal AI systems) have one major drawback: they are implemented based on a “black box” architecture, i.e. they are not transparent to the consumer of the results (in this case, an information security (IS) specialist) and have low interpretability (there is a result, but it is unclear why this result was obtained or what evidence supports it). This explains the increased interest in creating of “explainable” AI (Explainable Artificial Intelligence, XAI), and in particular, in creating of a new generation of phishing website detection systems based on it, which not only have high accuracy in detecting infected sites but also high interpretability (explainability) of the obtained results (examples illustrating the construction of such systems can be found in [

15,

16,

17]).

It should also be noted that building phishing website detection systems based on the previously mentioned ML, DL, and XAI methods in practice faces a lot of open questions such as:

the ambiguity in choosing a suitable dataset (training dataset);

the composition of features included in the dataset;

the architecture of the classifier model;

the values of its hyperparametersl;

the way of selection effective training algorithms (tuning) for the detection system;

and the mechanisms for interpreting the results, considering the natural limitations associated with the required computational costs of system implementation.

Thus, the goal of this study is to improve the effectiveness of multimodal models for analyzing phishing web resources using machine learning technologies.

This article is structured as follows. Chapter 1 analyses and systematizes relevant studies on the development of a machine and deep learning based phishing detection system using explainable artificial intelligence mechanisms. Chapter 2 presents the proposed approach for building a multi-modal phishing detection system based on deep learning and explainable artificial intelligence, and discusses the architecture of the system, the composition of its software modules and the tasks it performs. The last (third) chapter presents the results of the comparative experiments, which confirm the workability and efficiency of the developed system, and makes recommendations for its application in practice.

2. Analysis of Relevant Works

2.1. The Methodology for Data Collection for the Review has Been Further Explored

The objective of the review is to systematise and analyse modern approaches to developing multimodal phishing detection systems using XAI methods for the period from 2020 to 2025. The research results were peer reviewed by the following scientific databases: IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, Springer, ScienceDirect, arXiv, Google Scholar, e-Library, e-Library.ru, and cyberlinlin.ru.

Key search queries used to find sources for the review:

«multimodal phishing detection» AND («explainable AI» OR «XAI»);

«deep learning» AND «phishing detection» AND («SHAP» OR «LIME»);

«large language models» AND «phishing»;

«visual phishing detection» AND «interpretability»;

«multi-modal fusion» AND «cybersecurity».

Inclusion criteria: English or Russian peer-reviewed articles in scientific journals and conferences; technical reports from leading security organisations; open source projects with scientific substantiation; studies with empirical results.

Exclusion criteria: publications without a quantitative assessment of performance; work not related to multimodal analysis or to the XAI.

2.2. Review of Major Publications on Research into Multimodal Phishing Detection Systems

A large number of studies have been carried out on the practical application of machine learning and deep learning methods to the detection of phishing websites (for comprehensive reviews, refer to, for example: [

5,

7,

10,

13] ).

Table 1 provides some typical examples of the implementation of ML and DL-based systems, listing the authors of the relevant publications, the used data sets, ML and DL models and the achieved in detecting phishing sites accuracy.

Analysis of the content of these publications (

Table 1) leads to the following conclusions:

There are now fairly representative open datasets containing a large number of URL samples with a wide variety of characteristics for both phishing sites (Kaggle, Phishtank, OpenPhish, etc.). and legitimate sites (Alexa Rank, crawlcommon, etc.), which can be used in the training phase for phishing web-detection systems (see also [

18]);

An important stage preceding the training of such systems is a detailed study (Pre-processing) of the set of features of phishing and legitimate websites contained in the dataset, including their normalization and coding, analysis of correlation and informational significance, possible reduction of the dimensionality of the feature space, etc. using special methods of feature selection (Feature Selection) (detailed information on this can be found in [

19,

20,

21] );

Based on their research, authors of several publications [

21,

22,

23] pay close attention to the comparative assessment of the effectiveness of different ML models (as used in the specific issue of phishing web addresses) using such quality metrics as accuracy, recall, accuracy, and F1 score (harmonic mean); based on their research, random forest algorithms, decision trees and multi-layer perceptrons are preferred;

A hybrid ML model based on a committee of classifiers [

11] (for example implemented by RF algorithm) is particularly interesting in terms of improving the accuracy of phishing detection, where each individual classifier interacts with its own set of URL features and the final decision on the presence or absence of a phishing threat is taken by an arbitrator (MLP) using a separate voting system;

Combining Natural Language Processing (NLP) capabilities - URL, text blocks, domains, logs, etc. - processing visual elements (images) of the website and the structure of the HTML code in a multimodal approach [

10,

24,

25] not only increases accuracy, completeness and predict the evolution of new types of phishing attacks, including generative attacks.

Table 1.

The summary table shows the use of machine and deep learning methods in the detection of phishing attacks.

Table 1.

The summary table shows the use of machine and deep learning methods in the detection of phishing attacks.

| No. |

Authors |

Dataset |

ML/DL models |

Accuracy |

| 1. |

Al-diabat M. [19] |

University of Irvine Repository

(11,000 URLs, based on Phishtank

and Yahoo Directory, 30 features) |

Classifiers based on C 4.5 and IREP algorithms |

C 4.5–96%

IREP–95% |

| 2. |

Mahajan R., Siddavatam I., [22] |

Phishtank (19653 URLs) +

Alexa Rank (17058 URLs) |

Decision Trees (DT), RF, SVM |

RF–97,14% |

| 3. |

Almomani A., Alauthman M.,

Shatnawi M.T. et al, [20] |

Huddersfield University,

Dataset 1 (2,456 URLs, 30 features);

Dataset 2 (10,000 URLs, 48 features) |

16 ML models (RF, Classification and

Regression Trees (CART),

Logistic Regression (LR),

SVM, NN,

Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART),

etc.) |

RF–96%

(Dataset 1) and 98% (Dataset 2) |

| 4. |

Khera M., Prasad T.,

Xess L.D. et al, [23] |

Kaggle.com |

9 ML models (RF, DT, LR,

K-nearest neighbors (kNN),

XGBoost, XBNet, etc.) |

RF–97,3% |

| 5. |

Alazaidah R., Al-Shaikh A.,

Almousa M.R. et al, [21] |

Dataset 1 (11,055 URLs, 30 features, 2 classes)

Dataset 2 (1,353 URLs, 9 features, 3 classes) |

24 ML models, 6 learning strategies

(Naive Bayes, LR, MLP, AdaBoost,

RF, Random Tree, etc.) |

Filtered Classification J-48–

90,76% (Dataset 1);

RF–97,26% (Dataset 2) |

| 6. |

Dutta A.K., [4] |

Phishtank.com (6042 URLs) +

Crawlez (7658 URLs, based on Alexa Rank) |

LSTM |

97% |

| 7. |

Ghaleb F.A., Alsaedi M.,

Saeed F. et al, [11] |

Kaggle.com (651191 URLs) |

Hybrid ML model: 3 x RF +

Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) |

96,80% |

| 8. |

Krotov E.Yu., [10] |

Kaggle.com (10000 URLs) +

Common Crawe |

Multimodal system: CNN +

LSTM (image + text) |

92% |

| 9. |

Lee J., Lim P., et al, [24] |

Open Phish (1585 URLs) +

Alexa Rank (3000 URLs) |

Multimodal system: GPT-4-turbo,

Claude 3, Gemini Pro-Vision 1.0 |

GPT-4–92%

Claude 3–90% |

| 10. |

Syed Sh. A., [25] |

Phishtank, APWG, Open Phish |

BERT (text) + ResNet +

VGG16 (image) |

96,2% |

According to the review, multi-modal phishing detection systems can be categorised on the basis of three main criteria: the type of modalities used, the strategy for combining them, and the level of explainability integration.

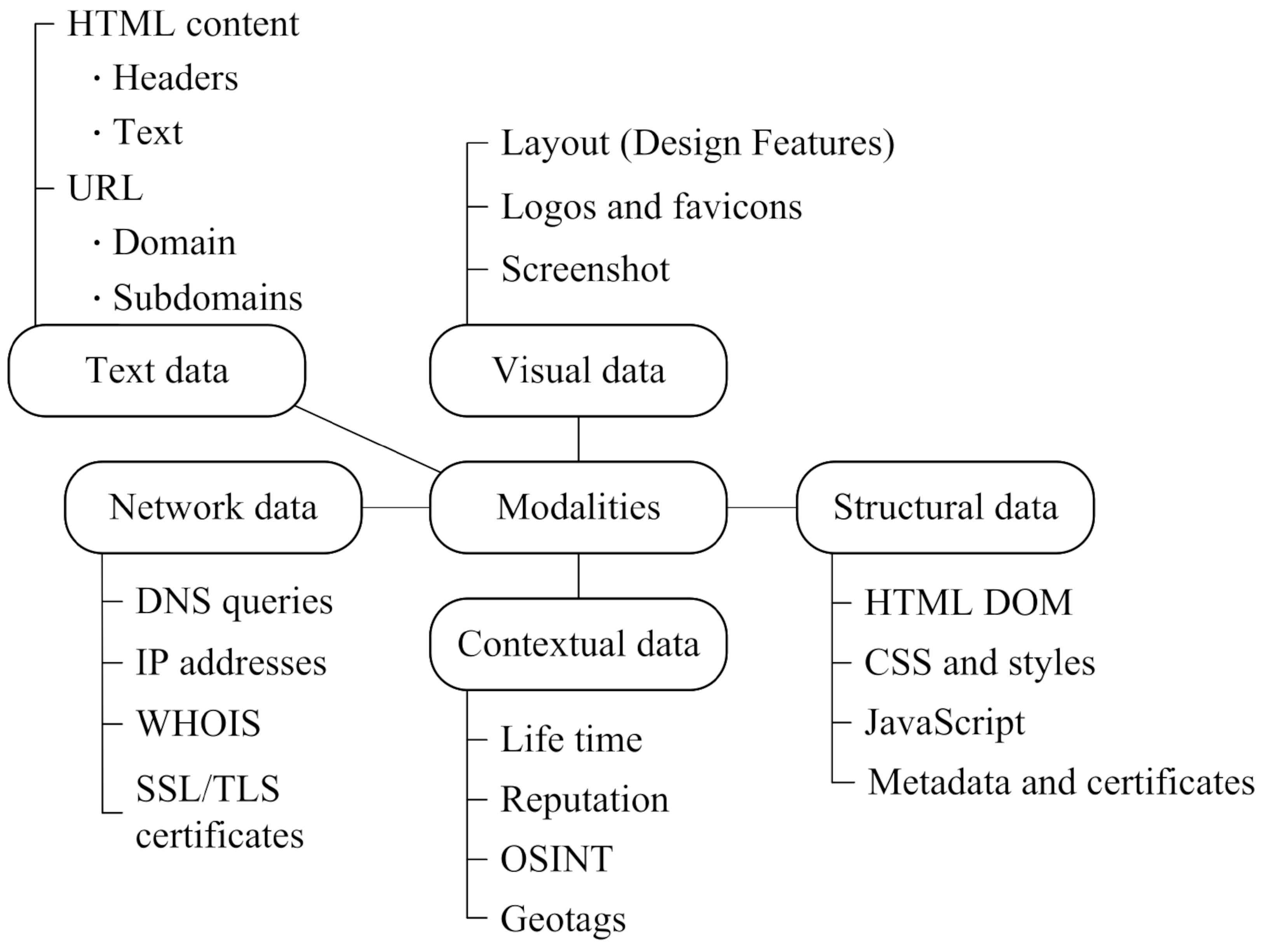

2.3. Classification of Data Types for Feature Generation in the Detection of Phishing Attacks

Figure 1 and

Table 2 show the possible classification [

13,

24,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] of data types for generating features (modalities) in modern systems.

Systematization of features in various modalities [

7,

12,

31,

32,

33]:

The main categories of URL features: lexical, syntactic, semantic, entropic, statistical;

The main categories of structural HTML features: DOM structural, data entry form structure, characteristics of the page’s script component, CSS and style features of the design template, and semantic HTML features;

The main categories of visual features: Logo Detection, Layout Analysis, Color Analysis, Visual Similarity, and Image Quality.

Table 3 shows the comparative characteristics of the achieved accuracy for multimodal detection systems for phishing attacks.

Analysis of publications on the classification of features shows:

URL features provide fast initial analysis with a relatively high accuracy (up to 93%), but are vulnerable to attack by URL obfuscation;

HTML features provide the most detailed information on the attack structure and are particularly effective in detecting credential phishing;

Visual features are critical for detecting brand impersonation and visual cloning attacks, achieving 94-98% accuracy, but require significant computational resources;

Multimodal integration outperforms single-modal approaches in F1 scores by 8-15 percent, but increases the time to classify (up to 5-10 seconds);

Feature engineering remains an important step even in the use of deep learning, as hand-selected and hand-crafted features ensure interpretability and resilience to adversarial perturbations.

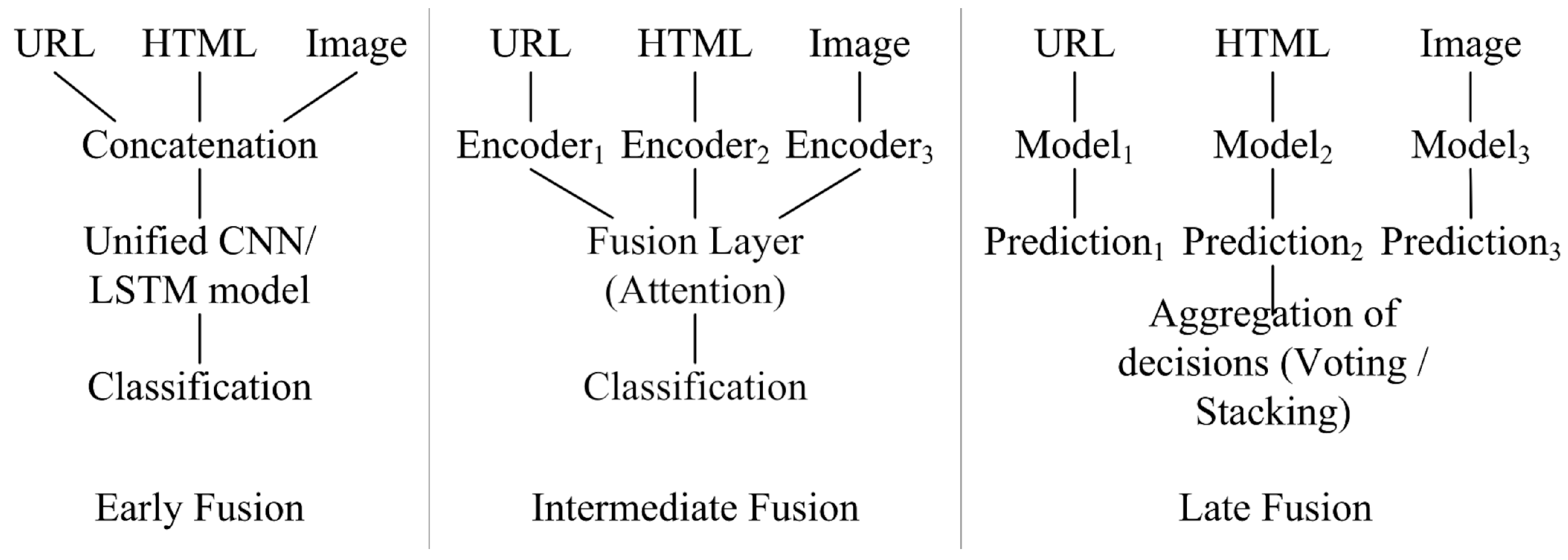

There are four main feature fusion strategies (Fusion Strategies) across all modalities [

28,

34,

38] (

Table 4 and

Figure 2):

Early fusion: concatenates the properties of all modalities at the input level, followed by processing with one model. Advantages: captures low level correlations of features, simple architecture of the final model. Disadvantages: loss of specificity of the modality, complexity of the training.

Intermediate fusion: each modalities is processed by a separate encoder, and then the features are combined at an intermediate level by means of an attentional mechanism. It provides a balance between specificity and interaction between modalities.

Late fusion: independently train specialized models for each modality with decision aggregation by means of voting or stacking. Advantages: model specialisation, modularity, parallelism. Best results for heterogeneous data.

Hybrid fusion: Combination of early and late fusion with adaptive weights. This strategy shows maximum performance with high architectural complexity.

2.4. Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods for Detecting Phishing Attacks

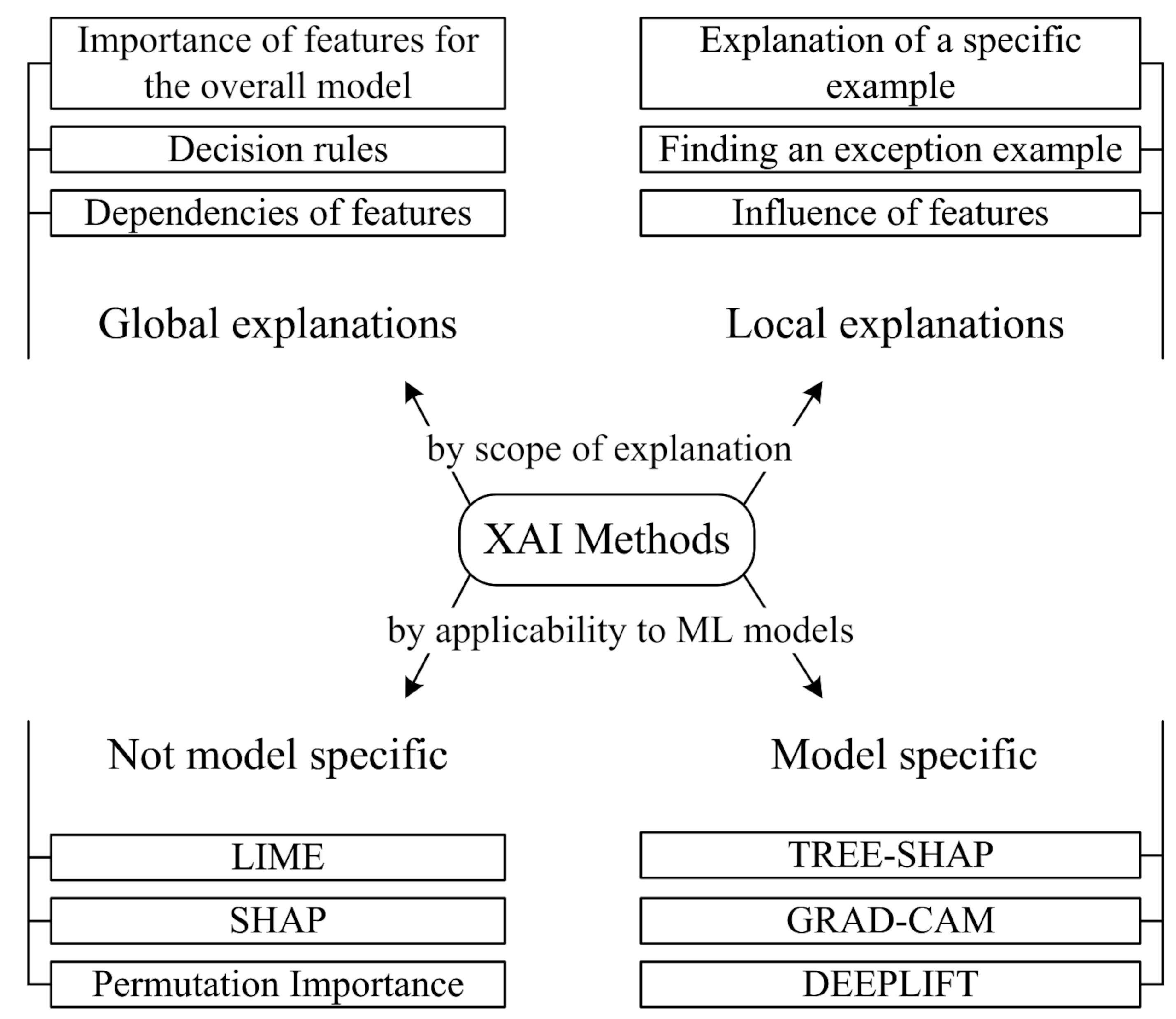

Regarding the need for explainability (transparency, interpretation) of decisions taken by phishing detection systems (i.e. explaining why a particular website is considered legitimate or phishing), a large number of studies have been published in this field of explainable AI research (XAI).

Explainable AI methods are classified according to the range of explanations (global and local) and the degree of focus on the model used (model-agnostic and model-specific [

39]) (

Figure 3). Global XAI methods [

39] provide a general understanding of the behaviour of the model across the entire dataset, including the importance of features and decision rules. Local methods [

40] explain the predictions of a particular model by showing the effect of the features on a specific sample.

Most of the research on the use of XAI for phishing detection tasks is focused on combining ML and specialised XAI methods to explain the decisions that it helps to make. These XAI methods are [

41]: LIME, SHAP, DTs (Decision Trees), LR (Logistic Regression), Partial Dependency plots, Integrated Gradients, and others. LIME and SHAP are the most popular.

The Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) method is a model-agnostic interpretation method applicable to different types of ML models. The method explains individual predictions of the ML model (i.e. binary classification results) by generating biased input values and building a simple, interpretable «input-output» model in relation to the range of URL features that are determined. This allows you to identify the most important (informative) URL features that have the greatest impact on the classification outcome. LIME [

40] constructs an interpretable neighborhood model in the vicinity of a prediction by generating biased samples and training a linear model. For example, the hybrid approach based on SHAP and LIME aggregated FS (SLA-FS) feature selection framework proposed in [

33] increased the accuracy of the classification of phishing links for the Random Forest model to 97.06 percent (+0.65) and for the XGBost model to 97.21 percent (+0.41).

SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanation) is an independent model-based method, as is LIME. It is based on game theory concepts and is based on calculating Shapley values that determine the contribution of each player (in this case URL feature) to the outcome of the cooperative game (in this case ML prediction of the nature of the web site). SHAP [

39] ensures local precision (the sum of the Shapley values is equal to the difference between the prediction and the average prediction), consistency (if a model change increases the contribution of a feature, its Shapley value does not decrease), and the absence of bias (features with no influence are assigned a zero value).

The following are examples of applying this approach (ML + XAI methods):

Phishing website detection system [

16]: Base classifier model (ML)—Random Forest (RF); Training datasets (datasets)—Phish Tank and Tranco; Number of used URL features is 26; Lorenz Zonoids (multivariate extension of the Gini coefficient) was used as a feature selection procedure (XAI method);

Phishing website detection system [

42]: Base classifier models–SVM and RF; Dataset–Ebbu 2017; Number of URL features–40; XAI methods–LIME and EBM (Explainable Boosting Machine); Prediction accuracy–94.7% (for SVM) and 97.3% (for RF);

A system for detecting phishing websites [

43]: 6 ML models were studied (XGBoost, LighGBM, RF, KNN, Twin SVM, CNN); 4 datasets (ISCX-URLs, P.L-URLs, Phish Guard URLs, Suspicious-URLs); the XAI-LIME method; The XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) model shows the highest forecast accuracy (Accuracy) of 96.8%.

One of approach to building a phishing website detection system based on XAI, proposed in [44], involves using a large language model (LLM) combining with processing input text data (URL features) using NLP, the Chain-of-Thought query decomposition algorithm, and a one-shot learning procedure (with a single example—a prompt). Here, the LLM simultaneously functions as a classifier and an explanatory module that generates a textual explanation of the classification result. Comparative experiments conducted by the authors [

44] to evaluate the effectiveness of various LLM usage options (5 LLM architectures and 3 datasets) showed the advantage of the GPT-4 Turbo transformer—the F1-score accuracy value was 0.92.

In [

40], the authors present the integration of XAI with large language models for generating natural language explanations for analyzing phishing emails. The system includes a detection module using classical ML models, which allows achieving an accuracy of 98.4%; a feature importance module (computing LIME and SHAP); an explanation module (DeepSeek v3, 671B parameters); and prompt templates with four explanation modes (detailed, educational, technical, and simplified). The explanation quality metrics on the reference set prepared by the authors provide an accuracy of 94.2%, a completeness of 87.6%, a consistency of 96.8%, and an actionability of 82.1%.

In [

35], the authors introduced the PhishTransformer model, which showcases the efficacy of self-attention mechanisms in URL analysis. The model accepts a URL as input; following tokenization and the implementation of convolutional layers at the character level, Positional Encoding and self-attention layers are used. In an experimental dataset comprising a balanced collection of 100,000 URLs, the authors achieved an F1-score of 0.99. The attention mechanism allows one to identify key tokens in a URL, based on which the decision is most often made about whether a link belongs to a legitimate (official TLD (.com, .org), known brands) or phishing (‘verify’, ‘secure’, ‘account’, ‘update’, ‘confirm’) URL.

Across the scenarios previously discussed, the application of XAI approaches provided logical explanations supporting the selection of a particular solution, thereby identifying the URL features that most strongly affected the prediction result (i.e., the reasons for classifying a specific website as either legitimate or phishing), which is of significant importance to the user, who is an information security specialist.

It should also be noted that, besides the mentioned approach to detecting phishing sites based on URL feature analysis, there are known examples of solving this problem using other features of website maliciousness and, respectively, other methods of interpreting the results obtained with their help. For example, to analyze the source code of a web page, the bimodal transformer model CodeBERT [

45] can be used, pre-trained on a large “code-documentation” dataset, which allows generating text comments on the program code based on a “zero-shot” scenario, i.e., without fine-tuning the model parameters. Such information is an interest to information security specialists, since the elements of the web page source code provide insight into the structure, design, and functionality of the website.

It is advisable to use XAI methods such as Grad-CAM (short for Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) [

46] and DeepLIFT (Deep Learning Important Features) [

47] during analyzing visual features (website homepage images, screenshots, logs, brand indicators) using convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

The Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) method [

48] creates heatmaps showing image regions important for classification using the gradients of the final convolutional layer.

The Phishpedia system proposed in [

36] uses Grad-CAM to visualize critical regions on phishing web pages, detecting 1,704 phishing sites in 30 days (1,133 zero-days—66.5%) with a False Positive Rate of 1.4%. Grad-CAM detected fake bank logos, suspiciously placed login forms, and non-standard brand color schemes.

A second widely used method for interpreting CNN output (DeepLIFT) evaluates the influence of each input (image pixel) on the neural network output using backpropagation, considering the contribution of each feature to neural network activation.

The authors of work [

49] conducted a systematic comparison of ten CNN architectures on the MTLP (Multi-Type Logo Phishing) dataset for the visual analysis of screenshots of web resource home pages. To build neural network analysis models, the authors used transfer learning for subsequent fine-tuning on a balanced set of 15,000 examples.

The authors found that the deep NN DenseNetBlur121D provides the best balance between classification accuracy and model size (F1-score 94.39%, classification time 45 ms, size 28.1 MB), the NN MobileNetV2 is optimal (F1-score 87.6%, classification time 21 ms, size 9.2 MB) for offline use on mobile devices (edge deployment), the NN ResNet50 demonstrates stability (F1-score 91.04%, classification time 38 ms, size 97.5 MB) on heterogeneous data.

In [

37], the authors address the problem of detecting previously unknown (zero-day) phishing websites through visual similarity by training a deep CNN with a triplets-based loss function. The model achieved 81% accuracy on zero-day attacks, outperforming VGG16 (51.32%) and ResNet50 (32.21%). Key advantages of the proposed solution include the ability to train on a few examples (few-shot learning) and robustness to design variations (color palettes, element placement).

Table 5 summarizes the characteristics of the explainable AI methods applied to analyzing phishing attacks.

Explanations for Table 5: Local visual explanation allows for the visualization of image regions that are important for decision-making in terms of models. Intrinsic (internally interpretable)–the model is inherently interpretable and does not require additional explanation methods.

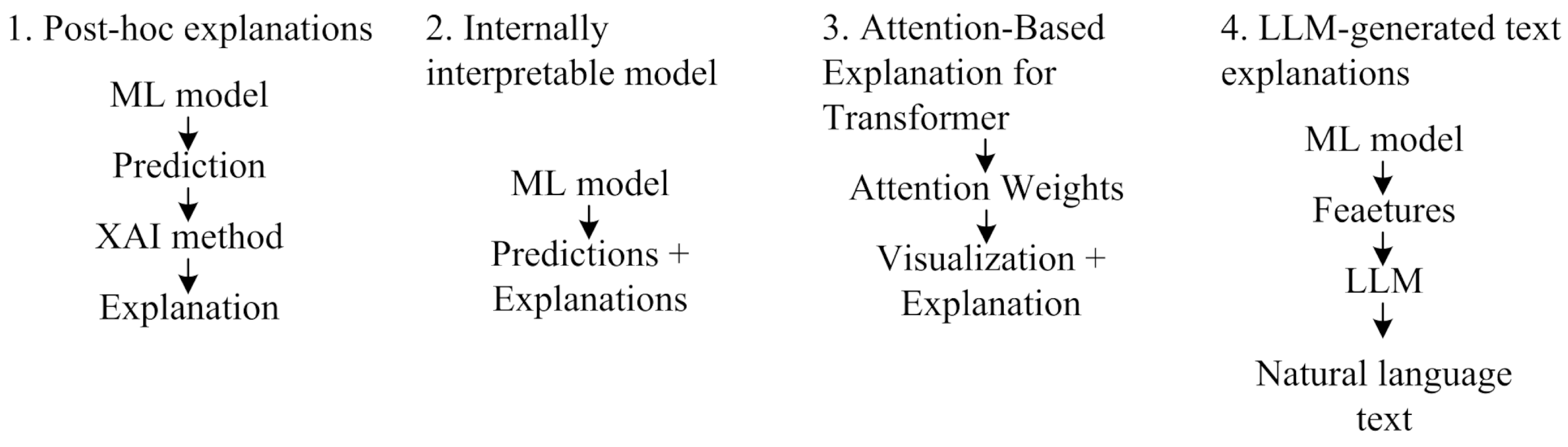

Figure 4.

Options for integrating XAI with ML models for analyzing phishing attacks.

Figure 4.

Options for integrating XAI with ML models for analyzing phishing attacks.

Another important principle for constructing explainable AI systems is the level of integration between XAI and the ML model. A possible classification of such integration is shown in

Table 6 below.

2.5. Main Datasets Used to Train Multimodal ML Models for Phishing Attack Detection

Some key datasets for training multimodal ML models are shown in

Table 7.

An analysis of datasets and reviewed studies provided insight into some facts:

Phishing sites are accessible for an average of 4-8 hours before being blocked, and datasets become quickly outdated;

The ratio of legitimate URLs to phishing URLs ranges from 100 to 1 to 1000 to 1 in real traffic of corporate information systems;

The percentage of annotation errors in community-driven datasets is quite high (up to 15%);

Features distributions are dynamic and change over time (concept drift).

2.6. Promising Multimodal Systems for Analyzing Phishing Attacks

A promising direction in developing systems for detecting phishing websites involves integrating GO, LLM, and XAI methods. This approach utilizes a multimodal system architecture that combines (concatenates) modules designed to process and analyze diverse features of phishing websites, including URLs, HTML content, screenshots, visual images, and source code. This comprehensive architecture ensures high accuracy, completeness, and reliability in detection while simultaneously achieving a high degree of interpretability (explainability) of the forecast results, attributable to the multifaceted nature of the analysis and the consideration of various perspectives on the detection task (see, e.g., [

52]).

The research outlined in [

27] introduces the PhishAgent system, an agent-based framework for phishing detection that leverages multimodal large language models. The perception module is designed to analyze various data modalities: it processes URLs using tokenization and embeddings, extracts features from HTML via Document Object Model (DOM) parsing, and performs object detection and brand database matching for logos. The reasoning module is predicated on employing a cloud-based Large Language Model (LLM) utilizing a Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting strategy. The system implements the construction of a brand knowledge graph and a database of known phishing patterns. The action module allows generating explanations and executing queries to external APIs (VirusTotal, WHOIS). The system ensures an F1-score of 93.7-96.2% on three datasets. Another distinctive feature is its resistance to adversarial attacks: a decrease in accuracy of only 2.3% (the best result among the systems considered by the authors). Disadvantages include the high cost of inference (via the API of cloud commercial LLM) and a processing delay of 5-15 seconds per query.

The paper [

28] presents the KnowPhish system, which addresses the problem of reference-based phishing detection without a predefined list of brands through the automatic construction of a multimodal knowledge graph. A multimodal approach is used, including a combination of visual (CLIP embeddings), text (BERT), and structural (GraphSAGE) analysis. The system achieves an F1-score of 89.6% for zero-day attacks and 94.3% for known threats.

The paper [34] proposes a system that has the highest accuracy in classifying phishing resources among non-LLM approaches through late fusion of specialized models. The system architecture includes a URL branch (character-level, CNN), a URL branch (vocabulary-level, Transformer), and an HTML branch (Graph Convolutional Network for DOM tree analysis). This approach enables an F1-score of 99.27% on a specialized dataset.

General-purpose LLM models can be nearly as good as specialized phishing analysis models in classification accuracy if the necessary prompt data is prepared, enabling web search capabilities, and can explain the decision in natural language. In [

44], the best LLM results for GPT-4 Turbo and Claude 3 achieved an F1-score of 0.92 in zero-shot prompt mode.

Domain-specific models for phishing analysis typically achieve over 95% F1-score on data with a known distribution, but have low generalization ability. It was shown in [

44] that URLNet and URLTran models, trained on a single dataset, lose 10-30% of their F1-score on URLs from other sources because of data drift. Therefore, a combination of transfer learning approaches (retraining specialized high-speed models) on new data is necessary, along with models capable of explaining classification results, providing meaningful support to the expert making the final decision.

This article examines the design and software implementation of multimodal systems.

2.7. Findings from the Systematic Review

Challenges encountered in the advancement of phishing attack detection systems involve:

Contemporary machine learning models exhibit susceptibility to adversarial attacks [

53], while existing certified defenses impose prohibitive computational overheads. This highlights critical research needs: (1) the development of scalable certified defenses for deployment in production systems, (2) the implementation of adaptive adversarial training robust to unknown attack types, and (3) the creation of robustness benchmarks tailored to the domain of phishing attacks.

Systems based on Large Language Models (LLMs) [

26,

27] demonstrate high classification accuracy; however, the latency inherent in their operation—specifically the 5-15 second delay in decision-making and explanations—presents a critical barrier to their utilization in real-time defense systems.

The most advanced detection systems for zero-day phishing threats attain recall metrics in the range of 87-94%. Existing systems consistently fail to detect 6-13% of unknown threats. To mitigate this vulnerability, actual research [

26,

28] efforts are focused on advancing few-shot learning, meta-learning, and anomaly detection to address these limitations.

Thus, multimodal phishing detection systems presently demonstrate the following properties:

Current hybrid architectures demonstrate detection accuracy, achieving performance rates of 98-99.68%. The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) has yielded a significant advancement in zero-day detection, with recall metrics ranging from 87-94%, while also enabling the generation of natural language explanations. Additionally, Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) methodologies are utilized in a substantial portion (80%) of recent research.

SThe adoption of multimodal systems has resulted in an improvement in accuracy metrics ranging from 5% to 12%. It has been demonstrated that late fusion techniques produce better outcomes when dealing with heterogeneous modalities. Furthermore, agent-based LLM architectures constitute a new paradigm characterized by their integrated reasoning functionalities.

A critical challenge is to ensure model adversarial robustness. This problem characterized by a 3–9% decrease in accuracy, temporal decay effect (an 8–15% degradation in performance without overfitting) and high LLM latency, which imposes significant real-time operational constraints.

3. Design of a Multimodal Phishing Website Detection System Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence

Present chapter describes the design and implementation process of a phishing web resource detection system, as well as a series of experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of multimodal analysis.

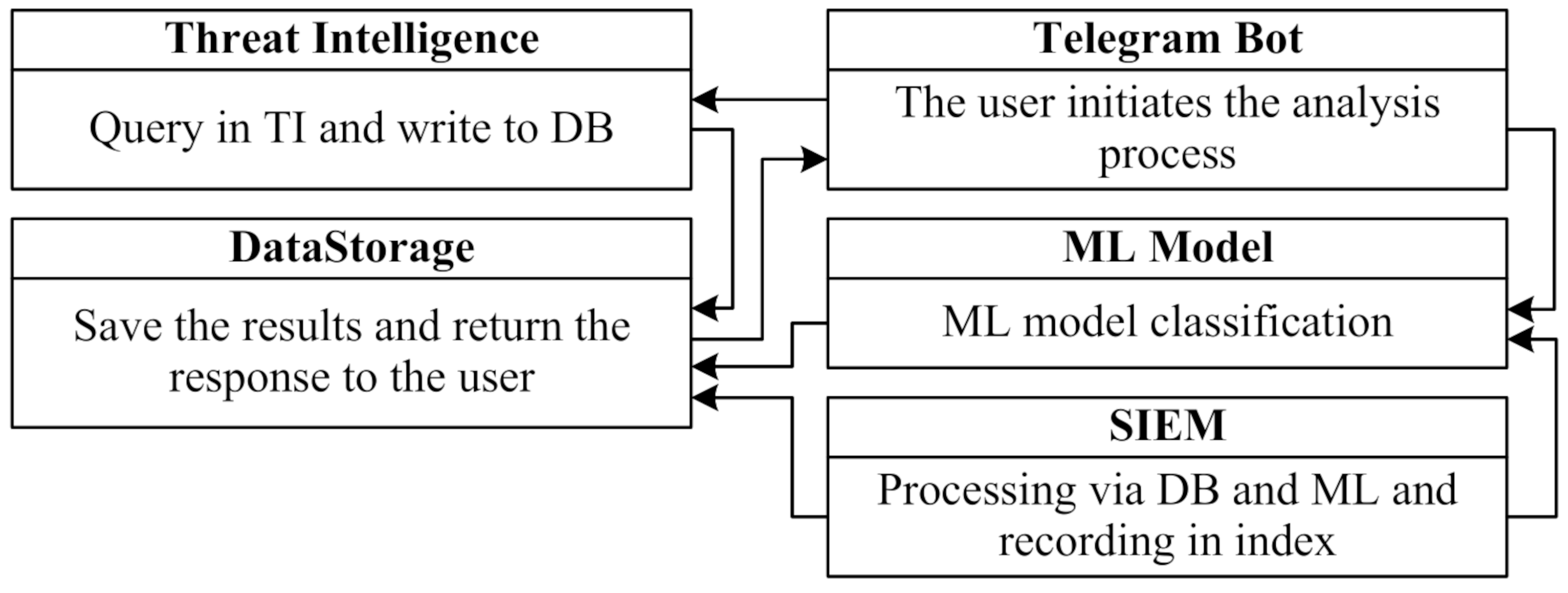

3.1. Structural Diagram of the Web Resource Analysis System

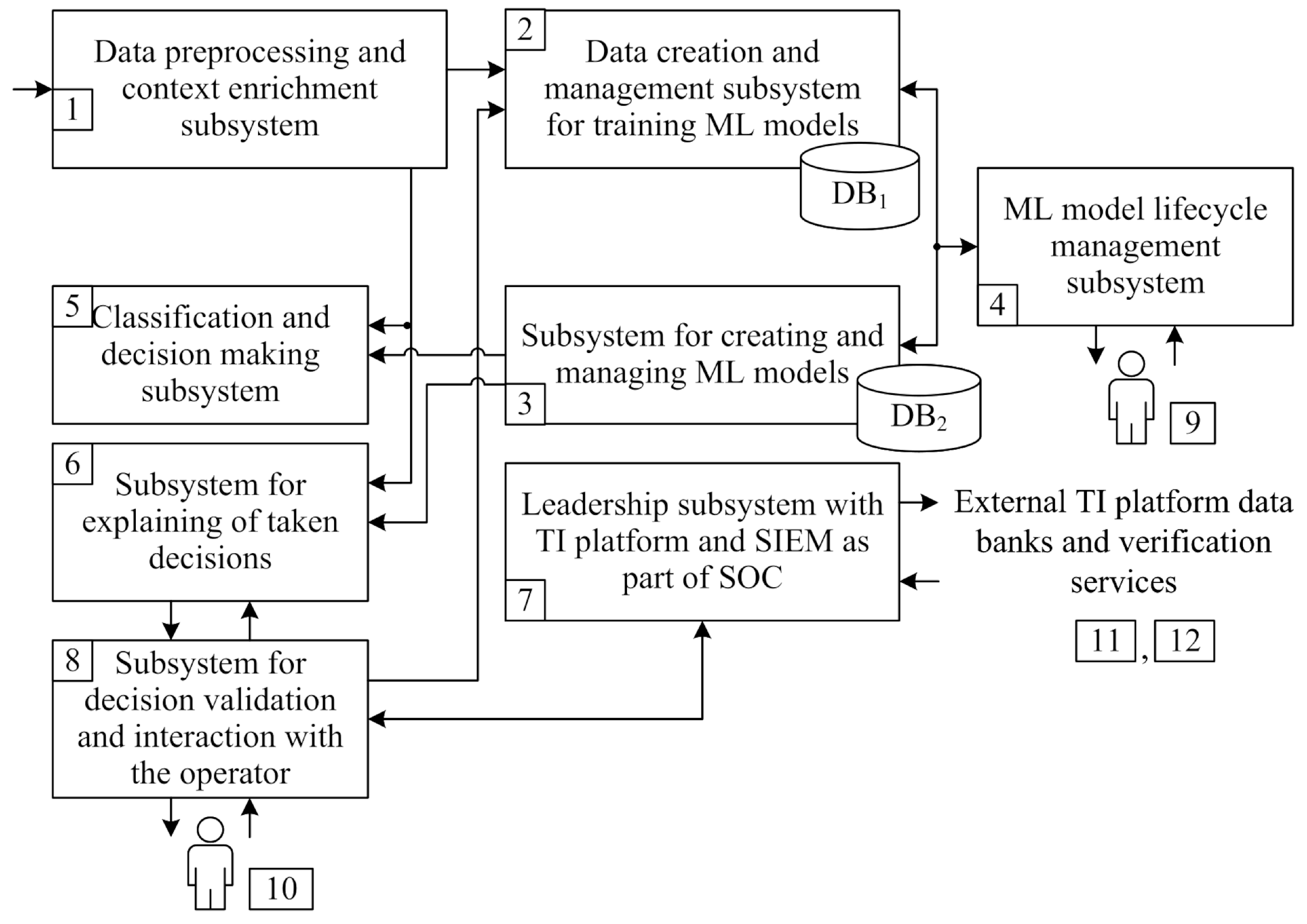

The structural diagram of the proposed web resource analysis system includes subsystems that implement a comprehensive analysis of the target resource using a multimodal committee of late-binding models, with the ability to generate detailed reports in natural language for the SOC expert (

Figure 5).

The system receives the URL of the web resource being analyzed, downloads the HTML of the home page, and also downloads an image of the home page (screenshot).

Subsystem (1) for preprocessing initial data and context enrichment performs (

Table 8):

Feature Extraction;

Context enrichment with data from external sources;

Normalization, standardization, and generation of a multimodal context.

URL analysis involves the extraction of lexical and statistical features and the collection of associated metadata. This metadata acquisition process includes verifying the URL domain’s affiliation with known domain lists and acquiring domain registration age data (WHOIS), and other data are collected. Over 89 features are generated, providing comprehensive information about the URL.

The subsystem (2) used for creating and managing data for training ML models enables to supplement the database (DB1) with new labeled data from external sources (e.g., PhishTank subscription newsletters) and internal data validated by SOC specialists.

Subsystem (2) comprises the following components:

A module dedicated to data labeling, re-labeling, and label validation;

A database (DB1) for storing enriched and prepared data;

A version management module for dataset tracking and synchronization with corresponding machine learning (ML) models;

A balancing and augmentation module configured to generate training, validation, and test datasets.

The regularly updated example database allows for further training and/or retraining of classifier models as data drift occurs. A database of explanations for URL phishing indicators is also being developed (for example, by comparing them with MITRE tactics and techniques, known APT attacks, etc.).

The subsystem for machine learning (ML) model creation and management (3) facilitates the updating of operational models deployed within the data processing pipeline. This subsystem incorporates the following modules:

Machine learning (ML) models specifically designed for the analysis of URLs/metadata, images, and the source code of target resource pages;

A late fusion multimodal module that operates based on a weighted model voting mechanism;

A product model database (DB2).

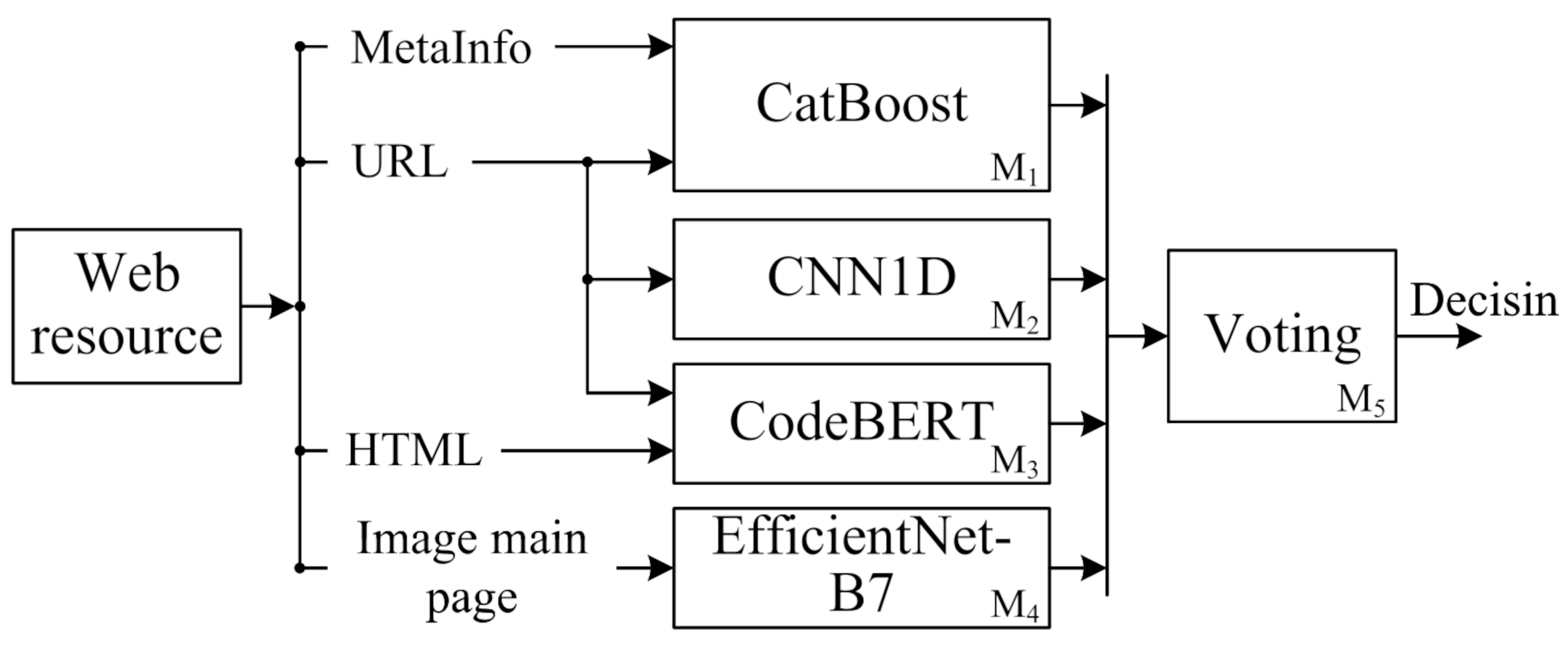

The structure of ML model interactions and the designations of specific models are shown in

Figure 6 and

Table 9.

Data analysts manage the model lifecycle using subsystem (4). Subsystem 4 includes the following modules:

A performance monitoring module;

A data drift detection module, which detects decreased model classification accuracy on freshly labeled data;

A retraining and/or updating of model modules at specified intervals.

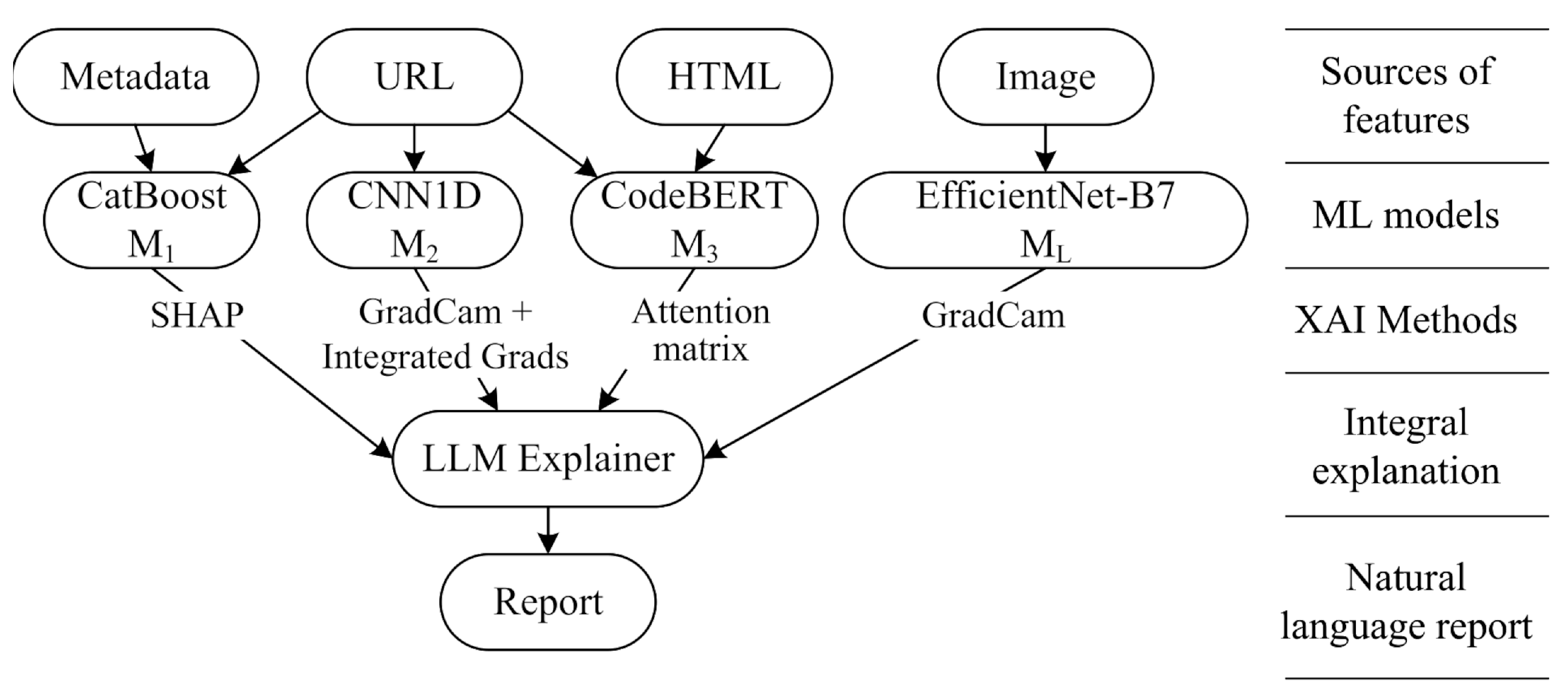

The subsystem for classification and decision making (5), using trained models, classifies the web resource being analyzed. The subsystem for explaining the decision (6) being made implements the scheme presented in

Figure 7 and

Table 10.

The subsystem implements API interaction with the locally installed LLM - the QwQ-32B reasoning model of the Qwen series [

59]. Data with of explanations for URLs’ classification as phishing links, prepared in subsystem (2), are used as a special prompt for zero-shot learning. The subsystem output (6) is a JSON file with a class name for the URL and a short text explanation of the result of the classification according to the proposed template. Only those Web sites that the model classifies as malicious are handled by the error correction mechanisms, which allows for an acceptable overall performance of the system, given the significantly (by two orders of magnitude) lower LLM performance in terms of event per time.

The SOC’s Thread Intelligence and SIEM Integration subsystem (7) collects metadata from web sources to improve the capabilities of modules for classifying and explaining information. This subsystem automates the response to phishing attacks by creating SOAR incidents and promptly reporting them to security monitoring specialists in the SOC.

The Decision Verification Subsystem (8) provides an interface for first and second line SOC monitoring experts to adjust the marking. The subsystem includes the following modules:

Reputation Services (VirusTotal, Google Safe Browsing, Kaspersky TI) as external data sources.

3.2. Key ML Models in a Multimodal Web Resource Analysis System

In the base version, ML models were trained independently of one another to implement a delayed-binding strategy and to be able to select models for different scenarios (stream event processing or back-end analysis of individual Web sites).

3.2.1. Developing URL Analysis Model

–CNN1D for URL Analysis at the Character Level

CNN1D (

Table 12) performs character-level analysis of local URL patterns. The choice of CNN was justified by the following:

the ability to extract local patterns as substrings characteristic of phishing URLs (e.g., "login," "secure") through the use of convolutions with kernels of varying sizes;

high analysis efficiency on the CPU because of the reduced number of model parameters, which allows for the simultaneous analysis of short ("@," "//") and long ("login") URL anomalies, improving classification accuracy.

A balanced (50% phishing and 50% legitimate web resources) MTLP dataset [

60] was used to train the model. It included:

Phishing URLs (from open sources such as PhishTank and OpenPhish);

Legitimate URLs (from popular services, including Google, Microsoft, and banking portals);

Metadata: page source code, domain WHOIS data, screenshots, and binary labels ("phishing"/"not phishing").

The CNN1D model for web resource symbolic name analysis demonstrates high efficiency in detecting phishing URLs, achieving an F1-score of 91.41% on the test set.

3.2.2. Development of a Model for Analyzing the Visual Image of the Main Page of a Web Resource

–CNN2D Model for Visual Image Analysis Based on Pre-Trained EfficientNet-B7

The analysis used a pre-trained version of EfficientNet-B7. It has demonstrated high performance in the field of computer vision tasks because of its balanced depth, width and resolution of the network. Pre-trained in ImageNet, EfficientNet-B7 is able to effectively detect complex visual patterns such as logo distortions, non-standard layout of UI elements and other phishing indicators. To adjust the model for binary classification tasks, the last layer has been replaced by a linear classifier that estimates the probability that a web resource belongs to the class of "phishing".

The model was trained on an MTLP dataset containing phishing and legitimate website images (50-50 split). To increase the model’s robustness to data changes, an augmentation was used; the images were scaled to a fixed size (16:9 aspect ratio) and normalized using the ImageNet Statistics.

For the training, the BCWithLogitsLoss loss function was used. This function combines binary cross entropy and logistic regression in one layer, ensuring numerical robustness. The AdamW optimizer, with a separate learning rate (1e-5 for frozen layers and 1e-4 for the classifier), minimizes the risk of weight corruption in the pre-trained weights. OneCycleLR was used to dynamically adjust the learning rate, with parameters cycling through [1e-5, 1e-3] depending on epoch progressed.

The developed visual image analysis model shows a high performance in detecting phishing sites, with an F1 score of 93.22 percent.

3.2.3. Development of a Model for Analyzing the HTML Code of the Main Page of a Web Resource

–Transformer for Analyzing the HTML Code of the Main Page Based on the Pre-trained CodeBERT

According to the source search, the BERT variants are the predominant variants for the text analysis of HTML content. The CodeBERT neural network transformer is pre-trained in code (six programming languages, including JavaScript) and is a powerful tool, including for JavaScript obfuscation detection.

The following were extracted from the source site’s home page: JavaScript code blocks, inline handlers, and HTML structure (forms, iframes, meta tags). The extracted blocks and URLs were combined into a single tokenization string with a maximum of 512 tokens.

The model was fine-tuned in batch mode on an MTLP dataset that contains phishing and legitimate web pages. The final classifier based on the CodeBERT retrained model achieved a F1 score of 0.950 using the test sample.

3.3. Key XAI Technologies as Part of a Multimodal Web Resource Analysis System

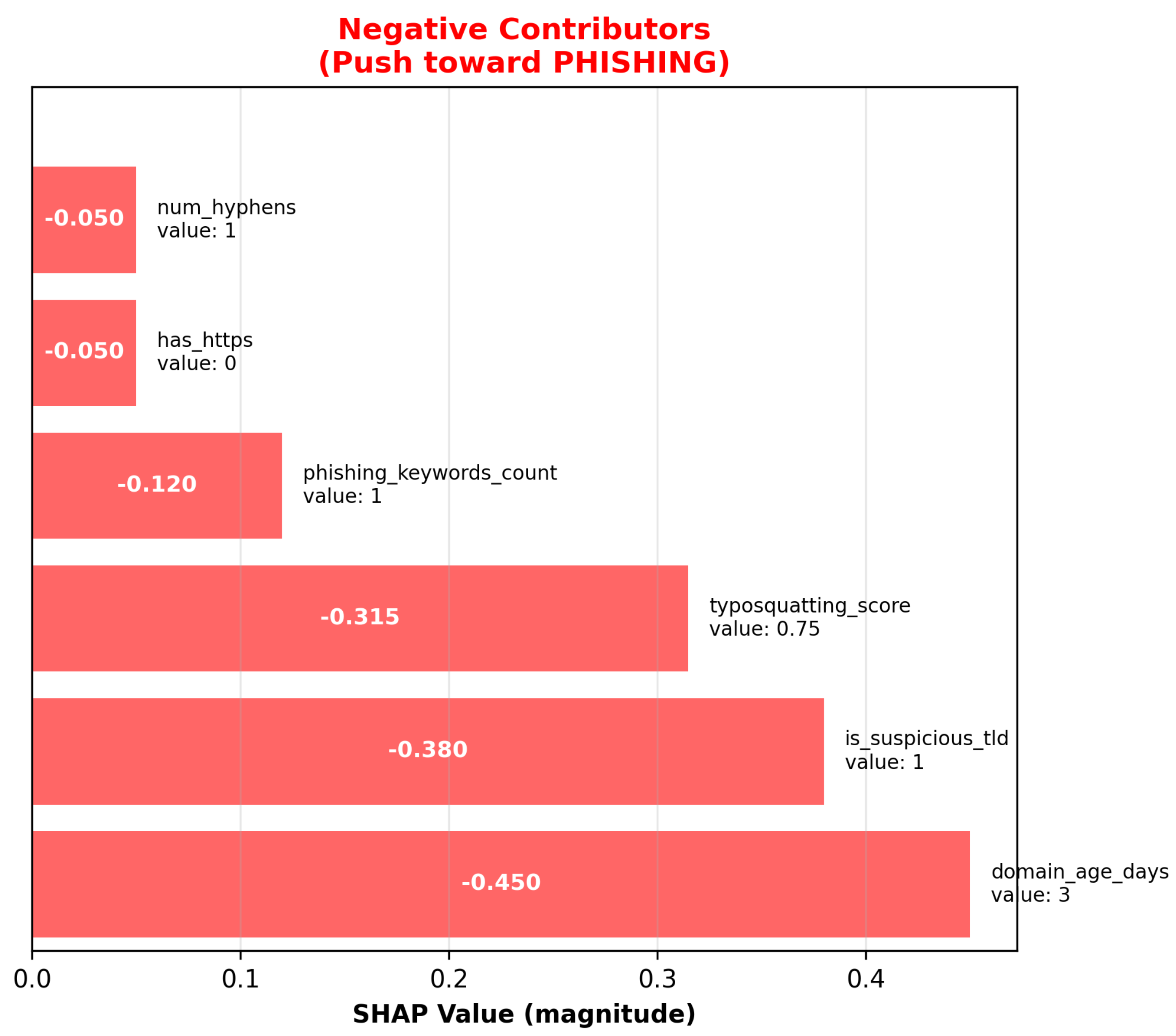

3.3.1. SHAP Coefficients for Interpreting the Performance of the M1: CatBoost Model

The Catboost framework has an inbuilt implementation for extracting values of SHAP coefficients for features. The results of the classification and decision making test are shown in

Table 13 and

Figure 8 for the synthetic test.

3.3.2. GradCam and Integrated Gradients for Interpreting the Performance of the M2: CNN1D Modell

An adapted version of the Grad-CAM method (for CNNs with one-dimensional input layer) weights the feature maps by importance using gradients and displays the focus area of the model in the intermediate representations (

Table 14).

The Integrated Gradients method works at the input level (URL symbols) and indicates the contribution of each symbol to the model’s final forecast based on an integrated gradient score (but requires a defined baseline).

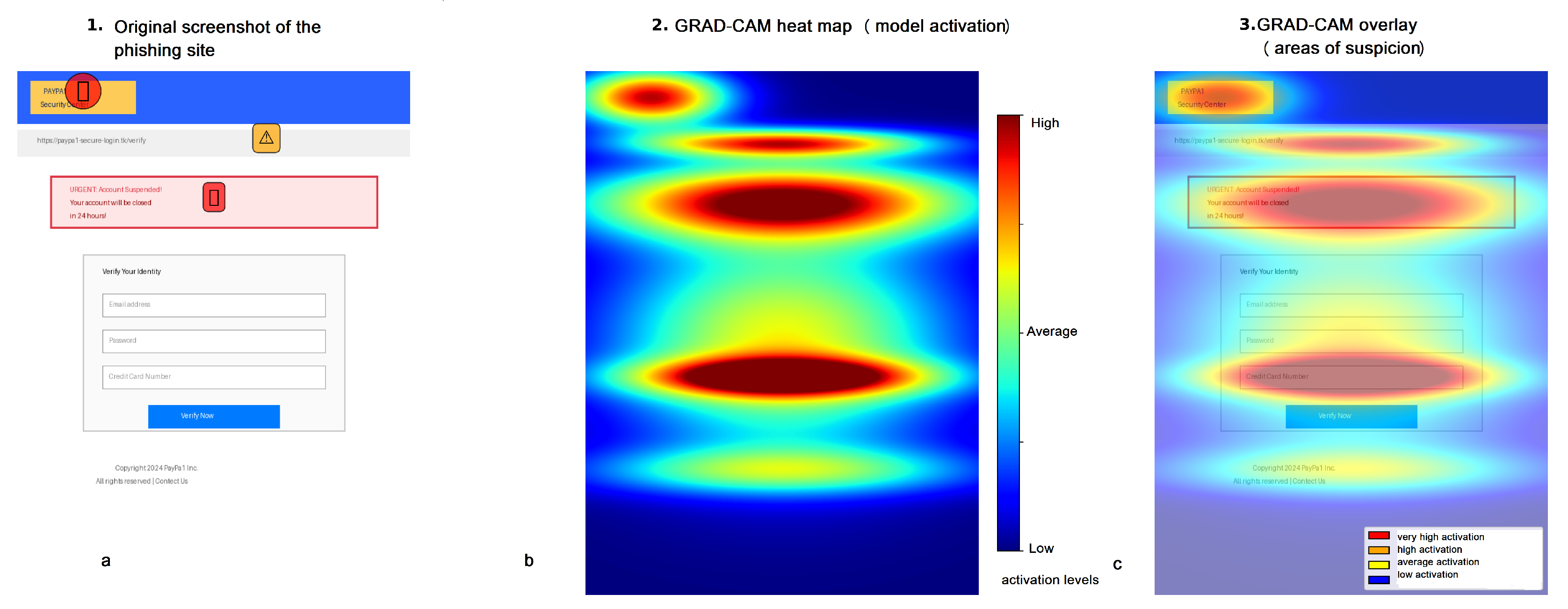

3.3.3. GradCam for Interpreting the Performance of the : CNN2D Model

The EfficientNetB7 neural network consists of Mobile Inverted Bottleneck Convolution blocks. The final layer prior to global average pooling was chosen for Grad-CAM operating. The MTLP dataset was previously used for the fine-tuning model, so a screenshot of the main page of the synthetic web site, PayPA1-Security.tk, was used to illustrate the operation of the XAI. Visualization results of the model operation are shown in

Figure 9.

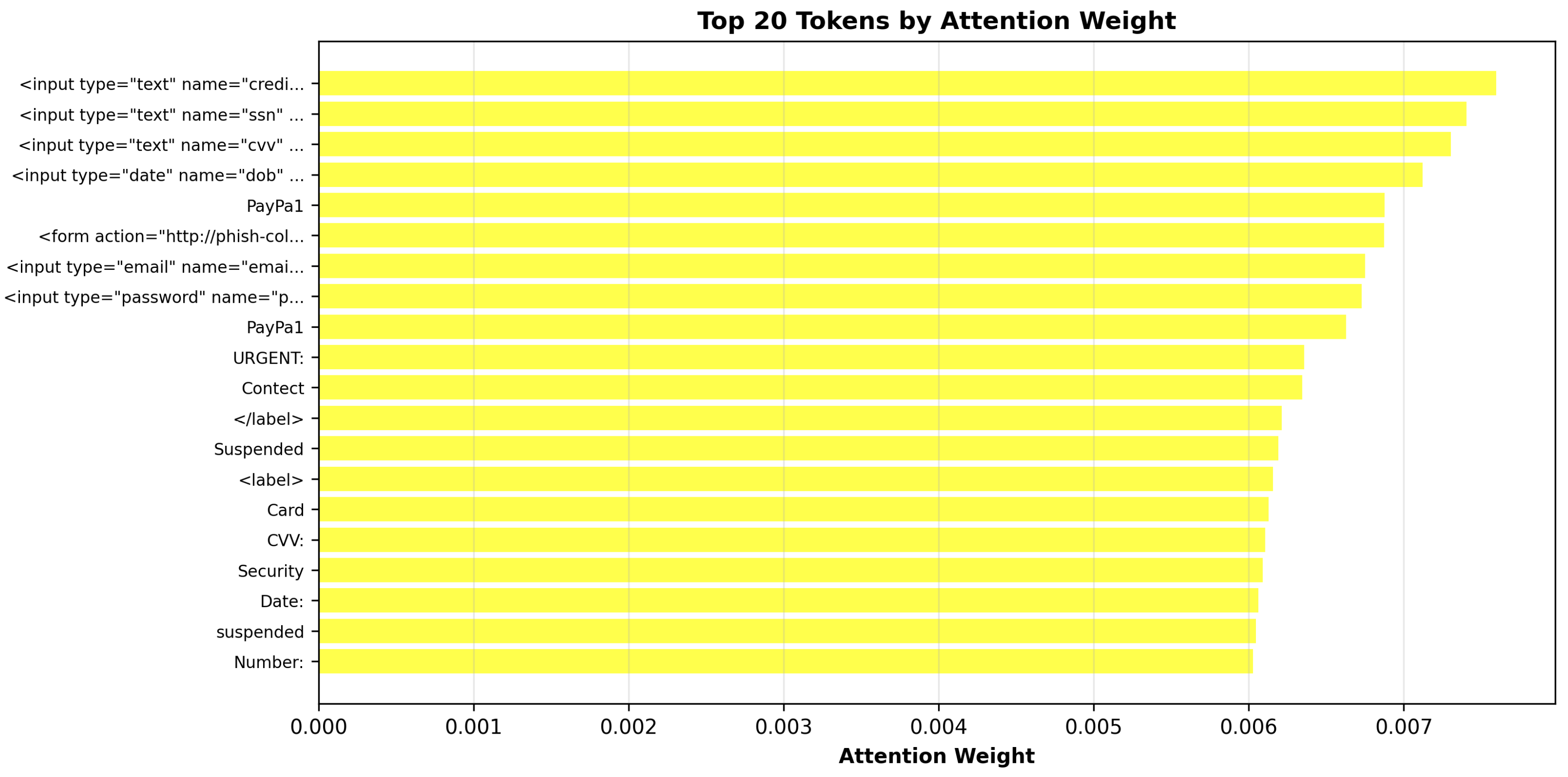

3.3.4. Attention Matrix for Interpreting the Work of the Model: CodeBERT

The attention matrix is a table that describes which HTML page elements the model considers to be related. When interpreted, this approach allows the relationship between extracted page elements and the URL to be evaluated and the final decision to be made.

For the synthetic web resource

http://paypa1-security.tk/login, the HTML page size was 2985 characters, 232 tokens were extracted, and the attention matrix includes 53824 elements. Examples of extracted tokens:

.

Figure 10 shows a histogram illustrating the distribution of Attention values among the extracted tokens in the binary web resource classification task.

3.3.5. LLM Explainer for Preparing Final Reports in Natural Language

Local LLM Qwen2.5-32B is used to generate the final natural language report summarizing the explanations obtained by the different approaches.

The Grad-CAM results for CNN2D are pre-matched with elements of the HTML page and fed into the explanatory model as an "element"-"importance" dictionary. This is achieved by semantically dividing the page and mapping the visual areas to the DOM.

Other structured explanations obtained from XAI models are also fed into the template as data to populate the prompt template. The Explanation module outputs a JSON file with a class label and a Markdown document with an extended textual explanation of the classification result using a static template.

The LLM will generate a report (

Appendix A) either for the Web sites of interest to the system user or only for sites that the model classified as harmful, allowing for acceptable overall system throughput.

3.4. Software Architecture of a Web Resource Analysis System

The proposed algorithms and model for analyzing web resource are implemented as software in Python with an assessment of effectiveness on real data

Figure 11.

The project consists of a group of containers, each of which performs a separate task, and their interaction provides full coverage of the process of analysis, verification and notification of potential threats:

"Telegram bot" (App-tg_bot) implements the functionality of receiving incoming messages from users and serves as the first link in the value verification chain.

"Machine learning module"–a container with a machine learning model is deployed on the basis of the "m_service" image, where the "/check_domain" endpoint is implemented via the Flask API. When a POST request with a domain is received, multi-stage processing occurs.

"The Threat Intelligence module" (App-ti_service) is a container for integration with external reputation services such as Kaspersky TI, VirusTotal TI and others via an API implemented on FastAPI.

"Data storage service"–a database for long-term storage of all system operation results; a container with a MongoDB database is used.

Container for updating Elasticsearch ("App-update_es"). In the test environment, the project uses Elasticsearch to analyze domains, where the "update_es" container is responsible for regularly updating the “idecoutm” index. Each time the script is run, a check is made to see if the current domain has been processed before: if a match is found, the document is updated to reflect the new results, and if not, a full check cycle is started. The update occurs every 3 seconds, which ensures that the data in Elasticsearch is up-to-date and allows to quickly track changes in the analyzed domains. With the help of Praeco, a correlation rule was created to notify analysts of the SOC, which allows for a prompt response to information security incidents.

The container management container ("Portainer"), which uses the "portainer/portainer-ce:latest" image, provides a web interface for managing all of the project’s Docker containers. Special attention has been paid during design to safety and data isolation. All containers run in a single virtual segment, with no external ports exposed except for the Telegram API and the Web Administration interfaces. All requests are handled over HTTPS, logged, and may be signed for investigation.

Particular attention was given to integration with existing monitoring systems during the design process. The used log structure allows for the transmission of events to SIEM systems, such as Wazuh, Splunk, and ELK-based solutions. The records are stored in MongoDB and replicated to Elasticsearch, which allows you to quickly create analysis views. The index is updated automatically and visualization is possible via Kibana or customized dashboard Praeco. This enables SOC analysts to monitor and make informed decisions on suspicious activity in real time.

The system was adapted to operate in the real world information security centre, including with regard to response procedures. The decision algorithm may be based on machine learning models or on data from external Threat Intelligence services. If necessary, the administrator may manually change the status of an object by adding it to the whitelist or blacklist. Scenarios for automatic action following a threat detection are described separately: e.g. sending the result to an e-mail gateway, adding an IP address to a blocking system, or sending a notification through a corporate messaging application.

The prototype was deployed using a high performance server, the parameters of which are shown in the

Table 15. In the isolated environment, each model used dedicated GPUs and data was exchanged between the models through RAM channels.

Thus, the developed architecture allows for:

processing queries in real time;

storing results and metadata for subsequent analysis;

scaling individual modules independently (e.g., multiplying ml_service);

integrating with external sources via APIs and with internal security systems via SIEM interfaces;

providing a visual interface for both users (via Telegram) and administrators (via Portainer and Mongo Express).

4. Computational Experiment to Evaluate the Performance of the Web-Based Resource-Analysis System

Several computational experiments have been performed on our own dataset and on the available MTLP dataset to provide a comparative assessment of the capabilities of the proposed solution.

The key stage in developing the automatic phishing web-resources detection system was the formation of an up-to-date data set. Datasets widely used in research (ISCX-2016 Dataset, EBBU-2017 Dataset, HISPAR-Phishstats Dataset) quickly become outdated. At the same time, the quality of the classification model, its ability to identify new attack patterns, sensitivity and specificity directly depend on the correctness and relevance of the data.

4.1. Computational Experiment I on the Prepared Dataset for Models and

4.1.1. The First Phase of Testing is Collecting the Dataset () and Preparing Models

Data was collected from several authoritative sources (Dataset ):

phishing URLs were obtained from open repositories: Phishing Site URLs (Kaggle), OpenPhish, URLHaus and PhishTank, where malicious link databases are updated daily;

legitimate URLs were selected from Alexa and Majestic Million Top 1 Million Websites lists, as well as downloaded from secure corporate proxy logs.

The initial sample contained over 4 million rows, of which, after cleaning and filtering, approximately 3,2 million unique URLs remained, balanced across classes.

Data labeling was performed semi-automatically. Some URLs were labeled based on the source (for example, if a link is taken from OpenPhish, it is a priori phishing). In complex cases, the following were used:

cross-checks via VirusTotal API;

built-in Reputational Score checking module;

manual check by WHOIS data (registration date, TLD zone, domain activity).

validation using OpenAI and QwQ-32B models in batch mode.

As a result, a data set was formed containing:

Table 16.

Estimated time costs for image processing in batch mode.

Table 16.

Estimated time costs for image processing in batch mode.

| Model |

Operation |

Batch performance evaluation |

Learning mode / inference during integration |

|

HTML tokenization |

25-50 ms |

GPU / GPU |

| Code-BERT ONNX |

200 ms |

GPU |

| Attention extraction |

15-20 ms |

GPU |

|

Feature extraction |

Less than 8 ms per URL |

GPU / CPU |

| SHAP computation |

Less than 12 ms per URL |

GPU / CPU |

| CatBoost C-compiled |

Less than 8 ms per URL |

GPU / CPU |

With a similar metric, CatBoost shows the best ROC-AUC metric of 0,924, indicating high ability to discriminate between classes. For the best CatBoost model, the False Positive Rate metric was 19,98%, and the False Negative Rate metric was 8,66%. With comparable performance of models based on ensembles of decision trees, the CatBoost model was selected, which has the best F1-score indicators on the test sample, but the preparation of the data preprocessing pipeline and the speed of model training are significantly higher. The model also allows to evaluate the significance of each feature during classification. The CatBoost model provides the best representation of categorical and quantitative features with the ability to be efficiently multi-threaded on CPU. When translating the model into the C language and then compiling it using LLVM, the model’s performance increased by 26% compared to the original version.

Additionally, a classifier was built based on the retrained Code-BERT model, deployed in the ONNX model format in the FastAPI container. The ONNX model format is a static computational graph in which the vertices are computational operators, and the edges are responsible for the sequence of data transfer across the vertices, which allows the model to run 1.5-2 times faster in classification mode. But using the model on a server with a CPU in multi-threaded mode loses to models based on CatBoost.

The peak performance estimate for the number of requests processed in the Security Operation Center (SOC) was: 231 thousand per day, 11 thousand per hour, 100 per second.

4.1.2. Second Stage of Testing–System Throughput Assessment

The second phase of the evaluation involved deploying the complete system on a test bed simulating the conditions of the SOC. The flow of incoming URLs was formed from several sources:

corporate mail gateway logs;

traffic through proxy servers and web filters;

specially generated requests through a Telegram bot.

The total volume of the test sample was about 100 thousand URLs, arriving at an average speed of 500 requests per minute. Under this load, the system demonstrated stable operation, with an average processing time of 47 ms for one request, including preprocessing, calling the model, and writing the results to the database. The peak load was up to 1100 URLs/minute, while no timeout errors or microservice freezes were recorded

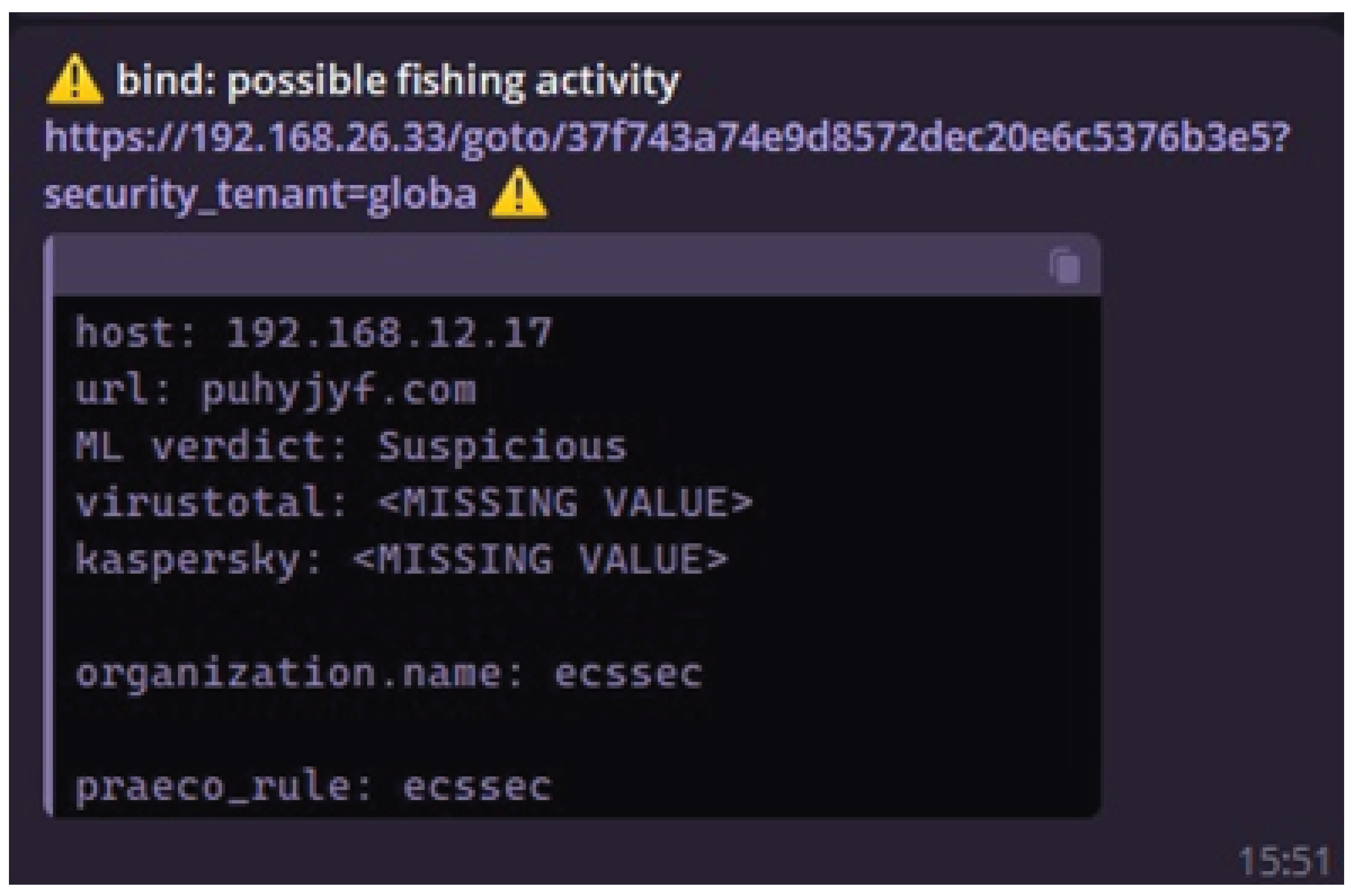

4.1.3. Third Stage of Testing–testing as part of the SOC

During integration with Praeco, an attack was simulated: within 5 minutes, the system received 20 fake URL links using the secure-update-login[.]com subdomain and replacing Latin characters with Cyrillic. The system worked with high accuracy, generated a trigger based on the correlation rule and sent a notification to the SOC Telegram channel (

Figure 12.).

4.1.4. The Fourth Stage of Testing–Zero-Day Resource Testing

In addition, manual testing was conducted on “zero day” links–URLs that were not previously in the database and which imitated new phishing patterns. Of the 100 such links, the system identified 92 as suspicious, including 6 that had no signs in the VirusTotal databases, but had an anomalous structure. For an objective assessment, the system was compared with open tools:

Google Safe Browsing;

OpenPhish Detection API;

URLhaus API.

The proposed model detected 15-20% more “fresh” phishing links, especially in cases of obfuscated addresses, short redirects, and character substitution. A significant advantage was provided by the explainability of classifications–the SOC analyst could immediately see on the basis of which features the link was classified as phishing.

4.1.5. Testing the Subsystem for Explaining Positive Responses

The application of a subsystem for explaining the reasons for classifying resources as phishing is shown for the expanded QwQ-32B model. The detailed explanation is used to justify a positive classification for SOC first-line monitors and allows them to agree or mark the alarm as a false positive for further adjustment of the training data. The application of approaches for estimating the SHAP coefficients at this stage was carried out only at the stage of preparing data for training models, since the obtained results require additional interpretation for monitoring specialists.

Thus, the conducted testing confirmed not only the high accuracy of the model, but also its suitability for deployment in real time. The system is capable of analyzing a large flow of incoming URLs, is scalable, and provides integration with response infrastructure, making it applicable to monitoring centers, highly secure organizations, and even national CERT structures.

4.1.6. Summary Results of Computational Experiment I

Table 17 presents the summary results of the computational experiment I.

4.2. Computational Experiment II on the Prepared Dataset for Models and

A balanced (50% phishing and 50% legitimate web resources) MTLP dataset was used to train the models (

Table 18).

The CNN1D model for web resource symbolic name analysis demonstrated high performance in detecting phishing URLs, achieving an F1-score of 91.14% on the test set (

Table 19).

The fine-tuned EfficientNet-B7 model for visual image analysis demonstrated high performance in detecting phishing websites, achieving an F1-score of 93.22% (

Table 19).

4.3. Computational Experiment III on the Prepared Data Set for all Models

The final experiment assessed the multimodal performance of the system on datasets

and

. Results are shown in the (

Table 20).

4.4. Discussion

The implemented prototype of the web resource analysis system validated the efficacy of a multimodal approach, integrating URL analysis, visual image and code of HTML page analysis. However, empirical testing identified several critical limitations that adversely affect user experience and compromise perceived system reliability.

The URL analysis model occasionally misclassifies legitimate and highly popular web resources—for instance, vk.com and rutube.ru—as phishing sites. These domains lack obvious suspicious features, such as lengthy query parameters or hidden iframes. The misclassifications may be because of the coincidental structural matching of these URLs with patterns recorded in the training dataset. A similar challenge is observed with the PhishLang model; even high performance metrics (an F1-score of 0.94) do not entirely eliminate classification errors on legitimate sites, likely because of the limited diversity of the training data.

The generation of web page screenshots with arbitrary resolutions and aspect ratios that do not align with the model’s training parameters results in a degradation of visual analysis quality. This occurs because the EfficientNet-B7 model, which was trained on standardized data, loses its capacity to accurately recognize key visual features, such as distorted logos.

The generation of web page screenshots with arbitrary resolutions and aspect ratios that do not align with the model’s training parameters results in a degradation of visual analysis quality. This occurs because the EfficientNet-B7 model, which was trained on standardized data, loses its capacity to recognize key visual features, such as distorted logos.

A significant advantage of the multimodal approach is its capacity to yield objective assessments, particularly when faced with false positives originating from a URL analysis model. For instance, in an evaluation of popular websites such as vk.com and google.com, the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model erroneously classified them as phishing sites. However, the EfficientNet-B7 model, utilizing visual content analysis, accurately identified these sites as legitimate. This discrepancy underscores the robustness of the multimodal framework in mitigating the systematic errors of individual constituent models, thereby substantially reducing the overall risk of false blockings.

Using transformer models allows to increase the F1-measure by 5% compared to the CatBoost model, but the URL processing time even in batch mode drops by more than 15 times. When a certain threshold value of events per unit of time is reached, this becomes unacceptable for real-time data analysis in SOC. Using local LLMs with prompt and Zero shot learning formation allows to supplement the results of malicious link classification with a text explanation. This increases the awareness of the first- and second-line SOC monitoring specialists during both routine monitoring and incident investigation mode.

The multimodal approach offers several key benefits:

Enhanced Detection Accuracy: It improves the detection accuracy of phishing attacks that are not identifiable by a single modality. This is because attackers face a greater challenge in bypassing all analysis modalities simultaneously.

Reduced False Positives: The use of a committee of models reduces the number of false positives by leveraging a committee of models.

Zero-Day Attack Detection: The system is capable of detecting novel (zero-day) attacks by analyzing a comprehensive combination of features across different modalities.

Improved Interpretability: The XAI (explainable artificial intelligence) subsystem provides insights into the contribution of each modality, thereby assisting analysts in understanding the rationale behind a detection decision.

5. Conclusions

The developed system for multimodal web resource analysis demonstrated high performance, achieving F1-scores comparable to the state-of-the-art on both publicly available (MTLP dataset, F1-score 0.953) and a continuously updated proprietary dataset (F1-score 0.989). These results were achieved while maintaining a high level of readiness for detecting zero-day attacks, a significant advantage over conventional industrial systems.

A prototype of a multimodal web resource analysis system was developed using a microservice architecture. The system is designed for high efficiency and seamless integration with a Security Operations Center, demonstrating the capability to process between 500 and 1,100 events per second (EPS) by utilizing a subset of the models.

The software implementation leverages Docker containers, RESTful interfaces, and a distributed logging system. Each component, including the Telegram interface, the analysis service, and the external Threat Intelligence platform module, is designed as an independent service. This architectural choice enhances the system’s scalability, fault tolerance, and maintainability.

Furthermore, the proposed models were optimized for CPU execution by compiling their code, which resulted in a 26% increase in computational performance. The system’s stability and operational integrity were validated through testing under conditions simulating a production environment, where it demonstrated reliable performance under load and successful integration with SOC environments, including visualization and correlation tools such as Elasticsearch and Praeco.

Multimodal phishing detection systems that integrate explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) have achieved substantial maturity in recent years, demonstrating high accuracy rates typically ranging from 98% to 99%, while simultaneously offering enhanced decision transparency. Nevertheless, the threat landscape is subject to continuous evolution driven by emerging adversarial threats, the proliferation of AI-generated phishing content, and the industrialization of attacks through Phishing-as-a-Service (PaaS) platforms. This dynamic environment necessitates ongoing innovation and adaptation of defensive measures.

The future of anti-phishing defense lies in hybrid approaches that combine the speed of traditional ML for real-time screening, the accuracy of LLM for zero-day detection, the robustness of ensemble methods against adversarial attacks, privacy-federation learning for collaborative defense, and human-in-the-loop intelligence for critical decisions.

Critical success in this domain is contingent upon achieving an appropriate equilibrium across several competing factors: automation versus human expertise, system performance versus interpretability, and centralized protection versus decentralized privacy. The development of a resilient defense against the continuously adapting threat of phishing requires a multidisciplinary collaborative effort, effectively integrating insights and methodologies from machine learning, cybersecurity, human-computer interaction, and legislative regulation

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V. and A.S. (Alexey Sulavko); methodology, A.V.; software, A.V., A.S. (Alexey Sulavko) and A.M.; validation, A.V., A.K. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.K.; investigation, V.V.; resources, A.V.; data curation, A.S. (Alexey Sulavko); writing—original draft preparation, A.V.; writing—review and editing, A.S. (Alexander Samotuga); visualization, A.K.; supervision, A.S. (Alexey Sulavko); project administration, A.S. (Alexey Sulavko); funding acquisition, A.S. (Alexey Sulavko). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the state assignment of Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation grant number theme No. FSGF-2023-0004.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data utilized in the present research are included within the article. Further inquiries should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Frodex LLC and ICSB LLC for providing access to computing resources and for their assistance in testing the developed software. This article is based on the results of the dissertation by A.M.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Excerpt From a Technical Report on the Results of the Classification of a Synthetic Web Resource, which was Generated Utilizing a Localized Large Language Model

Table A1.

Technical appendix

Table A1.

Technical appendix

## TECHNICAL APPENDIX

### Complete Model Predictions

CatBoost (URL features): 98.7% phishing

Character-CNN (URL chars): 96.2% phishing

CodeBERT (HTML structure): 95.8% phishing

EfficientNetB7 (Visual): 97.8% phishing

Consensus Average: 97.1% phishing

Standard Deviation: 1.3%

Agreement Level: VERY HIGH

### Complete SHAP Values (CatBoost)

domain_age: -0.45 (3 days old → suspicious)

tld_type: -0.38 (.tk → free, abuse-prone)

typosquatting_score: -0.52 (paypa1 vs paypal → deliberate)

url_length: -0.12 (slightly long)

subdomain_count: -0.08 (1 subdomain)

has_https: +0.15 (has HTTPS, but...) ... [additional features]

### Character-CNN Attribution Top 10

Position 8-13 "paypa1": IG attribution 0.92

Position 13 "1": IG attribution 0.95 (critical!)

Position 22-24 ".tk": IG attribution 0.88

Position 15-21 "secure": IG attribution 0.45 ... [full attribution map available]

### CodeBERT Attention Top 10 Tokens

<input name="creditcard">: 0.95 weight (CRITICAL)

<input type="password">: 0.89 weight

<form action="http://...">: 0.82

weight (insecure) "urgent": 0.78

weight "suspended": 0.78

weight "verify": 0.68

weight "account": 0.65 weight ... [full token list available] “`

Visual GradCAM Regions (Top 5)

Region 1: Logo area

- Position: top-left (header)

- Activation: 0.95/1.0

- Area: 2.1% of page

- Text: "PAYPA1 Security Center"

- Elements: visual_element, square_element |

Region 2: Warning banner

- Position: center (main_content)

- Activation: 1.0/1.0 (maximum!)

- Area: 8.5% of page

- Text: "URGENT: Account suspended in 24 hours"

- Elements: visual_element

Region 3: Form area

- Position: center (form_area)

- Activation: 0.88/1.0

- Area: 3.2% of page

- Text: "Credit Card Number", "CVV"

- Elements: input_field (multiple)

Region 4: URL bar representation

- Position: top-center (header)

- Activation: 0.85/1.0

- Text: "https://paypa1-secure.tk"

Region 5: Footer

- Position: bottom (footer)

- Activation: 0.45/1.0

- Text: "Copyright 2024 PayPa1" [with typo]

- Elements: text, poor_quality |

REPORT METADATA

Report Generated: 2025-10-23 18:30:51 UTC

Analysis Duration: 3.7 seconds

Models Used: 4 (CatBoost, CharCNN, CodeBERT, EfficientNetB7)

XAI Methods: 6 (SHAP, GradCAM 1D, IntGrad, Attention, GradCAM 2D, Text Convert)

LLM Model: Qwen2.5-32B-Instruct

Confidence: VERY HIGH

Analyst Review: RECOMMENDED (for quality assurance) |

END OF REPORT

This report was generated by an AI-powered phishing

detection system combining multiple deep learning models

with explainable AI techniques.

While highly accurate, human expert review is recommended for critical cases. |

References

- Golushko, A. Current Cyber Threats: Q4 2024–Q1 2025. Technical report, Positive Technologies.

- Phishing Activity Trends Reports. Technical report, APWG Report.

- Phishing Detection in Depth: Attack Types, Detection Tools, and More. Technical report, zvelo.

- Dutta, A.K. Detecting phishing websites using machine learning technique. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0258361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, A.; Zafar, M.; Liu, X.; Javed, A.R.; Jalil, Z.; Kifayat, K. A comprehensive survey of AI-enabled phishing attacks detection techniques. Telecommunication Systems 2021, 76, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukmanova, K.; Kartak, V. The development of a phishing attack protection system using software-hardware implementation of machine learning methods. Modeling, optimization and information technology 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavya, S.; Sumathi, D. Staying ahead of phishers: a review of recent advances and emerging methodologies in phishing detection. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 58, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornyukhina, S.; Laponina, O. Exploring the Potential of Deep Learning Algorithms to Protect Against Phishing Attacks 2023. 11, 163–174.

- Li, W.; Manickam, S.; Chong, Y.W.; Leng, W.; Nanda, P. A State-of-the-Art Review on Phishing Website Detection Techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 187976–188012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krotov, E. Applying Deep Learning Methods to Phishing Website Detection: Performance Analysis and Model Optimization. Current research, 256.

- Alsaedi, M.; Ghaleb, F.; Saeed, F.; Ahmad, J.; Alasli, M. Cyber Threat Intelligence-Based Malicious URL Detection Model Using Ensemble Learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljofey, A.; Jiang, Q.; Rasool, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Qu, Q.; Wang, Y. An effective detection approach for phishing websites using URL and HTML features. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, T.; Gonsalves, T. Multimodal Phishing Detection on Social Networking Sites: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 103405–103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal Machine Learning: A Survey and Taxonomy, 2017. Version Number: 2. [CrossRef]

- J, G. The Role of Explainable AI in Understanding Phishing Susceptibility. JOURNAL OF RECENT TRENDS IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING ( JRTCSE) 2024, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Calzarossa, M.C. ; Department Of Economics&Management, P.G.S.; Zieni, R. Explaining Explainable Ai, with Applications to Phishing Detection, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shyni, E. Enhancing Phishing Detection with Explainable AI (XAI): A Transparent Cybersecurity Approach. Technical report, Smart Security Tips.

- Vrbančič, G.; Fister, I.; Podgorelec, V. Datasets for phishing websites detection. Data in Brief 2020, 33, 106438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-diabat, M. Detection and Prediction of Phishing Websites using Classification Mining Techniques. International Journal of Computer Applications 2016, 147, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, A.; Alauthman, M.; Shatnawi, M.T.; Alweshah, M.; Alrosan, A.; Alomoush, W.; Gupta, B.B.; Gupta, B.B.; Gupta, B.B. Phishing Website Detection With Semantic Features Based on Machine Learning Classifiers: A Comparative Study. International Journal on Semantic Web and Information Systems 2022, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaidah, R.; Al-Shaikh, A.; Almousa, M.; Khafajeh, H.; Samara, G.; Alzyoud, M.; Al-shanableh, N.; Almatarneh, S. Website Phishing Detection Using Machine Learning Techniques. Journal of Statistics Applications & Probability 2024, 13, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R.; Siddavatam, I. Phishing Website Detection using Machine Learning Algorithms. International Journal of Computer Applications 2018, 181, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, M.; Prasad, T.; Xess, L. Malicious Website Detection using Machine Learning. International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology (IJERT) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lim, P.; Hooi, B.; Divakaran, D.M. Multimodal Large Language Models for Phishing Webpage Detection and Identification, 2024. Version Number: 1. [CrossRef]

- University of the Cumberlands, Kentucky, United States of America.; Syed, S.A. AI-Driven Detection of Phishing Attacks through Multimodal Analysis of Content and Design. International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer and Communication Engineering 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Trad, F.; Chehab, A. Large Multimodal Agents for Accurate Phishing Detection with Enhanced Token Optimization and Cost Reduction. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Foundation and Large Language Models (FLLM), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2024; pp. 229–237. [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; He, A.; Oo, N.; Hooi, B. PhishAgent: A Robust Multimodal Agent for Phishing Webpage Detection, 2024. Version Number: 3. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, C.; Deng, S.; Lock, M.L.; Cao, T.; Oo, N.; Lim, H.W.; Hooi, B. KnowPhish: Large Language Models Meet Multimodal Knowledge Graphs for Enhancing Reference-Based Phishing Detection 2024. Publisher: arXiv Version Number: 2. 2. [CrossRef]

- Alshingiti, Z.; Alaqel, R.; Al-Muhtadi, J.; Haq, Q.E.U.; Saleem, K.; Faheem, M.H. A Deep Learning-Based Phishing Detection System Using CNN, LSTM, and LSTM-CNN. Electronics 2023, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnabi, S.; Krombholz, K.; Fritz, M. VisualPhishNet: Zero-Day Phishing Website Detection by Visual Similarity, 2019. Version Number: 4. [CrossRef]

- PhiUSIIL Phishing URL Dataset.

- Chiew, K.L.; Tan, C.L.; Wong, K.; Yong, K.S.; Tiong, W.K. A new hybrid ensemble feature selection framework for machine learning-based phishing detection system. Information Sciences 2019, 484, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafin, S.S. An explainable feature selection framework for web phishing detection with machine learning. Data Science and Management 2025, 8, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Buu, S.J.; Kim, H.J. Phishing Webpage Detection via Multi-Modal Integration of HTML DOM Graphs and URL Features Based on Graph Convolutional and Transformer Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, S.; Xiao, Y.; Li, T. PhishTransformer: A Novel Approach to Detect Phishing Attacks Using URL Collection and Transformer. Electronics 2023, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (PDF) Phishpedia: A Hybrid Deep Learning Based Approach to Visually Identify Phishing Webpages.

- Abdelnabi, S.; Krombholz, K.; Fritz, M. VisualPhishNet: Zero-Day Phishing Website Detection by Visual Similarity. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS). ACM, 2020.

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Liu, L.; Tan, J. Multiphish: Multi-Modal Features Fusion Networks for Phishing Detection. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021 - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada; 2021; pp. 3520–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.M.; Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; Galazzo, I.B.; Radeva, P.; Petersen, S.E.; Lekadir, K.; Menegaz, G. A Perspective on Explainable Artificial Intelligence Methods: SHAP and LIME. Advanced Intelligent Systems 2025, 7, 2400304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Huerta, R.; Sotelo, A.; Quintela, A.; Kumar, P. EXPLICATE: Enhancing Phishing Detection through Explainable AI and LLM-Powered Interpretability, 2025. arXiv:2503.20796 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Shendkar, B.D.; Chandre, P.R.; Madachane, S.S.; Kulkarni, N.; Deshmukh, S. Enhancing Phishing Attack Detection Using Explainable AI: Trends and Innovations. ASEAN Journal on Science and Technology for Development 2024, 42, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galego Hernandes, P.R.; Floret, C.P.; Cardozo De Almeida, K.F.; Da Silva, V.C.; Papa, J.P.; Pontara Da Costa, K.A. Phishing Detection Using URL-based XAI Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Orlando, FL, USA; 2021; pp. 01–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]