1. Introduction

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology establishes a direct communication pathway between the human brain and external devices, emerging as a transformative force in fields such as rehabilitative engineering, robotics, and cognitive neuroscience [

1]. As a prominent paradigm within this domain, Motor Imagery-based BCI (MI-BCI) operates by decoding the specific neural patterns generated during imagined limb movements, while concurrently holding significant promise for practical applications [

2,

3]. Among various modalities for monitoring neural activities, electroencephalography (EEG) is the predominant method due to its non-invasive nature, which records bioelectric signals from cortical neurons via scalp-mounted electrodes and simultaneously offers an ideal balance of a high safety profile, excellent temporal resolution, and low cost, thus establishing it as the standard for both research and application in MI-BCI [

4,

5].

The technical workflow of an MI-BCI system typically involves the acquisition and preprocessing of EEG signals from a specific mental task, followed by feature extraction and classification to recognize the user’s motor intent. Despite its structured process, EEG-MI classification faces significant challenges arising from the inherent electrophysiological properties of EEG signals. At the signal level, the challenge lies in the extremely low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which is often below -10dB. This poor SNR arises because the microvolt-level motor-related cortical potentials (MRCPs) are heavily contaminated by artifacts such as electromyography (EMG) and ocular interference, resulting in a weak signal that impairs the efficacy of feature extraction and classification [

6]. At the feature level, the key event-related desynchronization/synchronization (ERD/ERS) patterns exhibit high non-stationarity and substantial inter-subject variability, making it difficult for traditional methods reliant on hand-crafted features like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) or Power Spectral Density (PSD) to capture these complex non-linear dynamics [

7,

8]. Most critically, conventional approaches suffer from significant performance degradation across different sessions and subjects, with clinical data revealing accuracy fluctuations of up to 10%-20% for such classic classifiers as Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) [

9], thereby severely hampering the practical deployment of MI-BCI systems.

To overcome the heavy reliance on manual feature engineering and the poor generalization of traditional methods, deep learning has emerged as a new paradigm for motor imagery decoding in MI-BCI systems. Unlike their conventional counterparts, deep neural networks can automatically learn complex non-linear mappings and demonstrate superior robustness against inter-subject variability and low SNR. Early explorations, such as Joseph et al.’s 1994 use of neural networks to classify clinical neurophysiological data, paved the way for this shift [

10]. Following this work, the advent of novel spatio-temporal convolutional architectures like Shallow ConvNet and Deep ConvNet, which directly extract ERD/ERS features from EEG

rhythms, marked the transition of EEG-MI classification to an era of end-to-end modeling [

11]. Subsequent research has focused on architectural refinements to advance classification performance. EEGNet introduced depthwise separable convolutions to reduce model complexity [

12], while EEG-TCNet enhanced temporal dependency modeling by integrating a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) into the EEGNet framework [

13]. Further advancements came from models like CIACNet [

14], SMT [

15], and ASiBLS [

16], which augmented the TCN with techniques such as multi-branch structures, multi-scale convolutions, and attention mechanisms. Despite these improvements, the fixed-dilation convolutions of TCNs still struggle to capture the aperiodic rhythms, temporal jitter, and cross-phase latency variations inherent in EEG signals. This limitation has spurred the development of hybrid modeling architectures. One prominent direction involves integrating the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism with the TCN, enabling models like EEG-Conformer [

17], M-FANet [

18] and MCTD [

19] to synergistically model both local rhythms and long-range dependencies. Another approach leverages the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture for its capacity to track dynamic state evolution. By combining convolutions with the gated units of LSTM, models such as CNN-LSTM [

20] and FBLSTM [

21] have improved the representation of phase-like changes in EEG signals, thereby boosting the accuracy of classification.

Owing to their distinct designs, different temporal modeling architectures present unique strengths and limitations in capturing the complex temporal features of EEG signals. TCN, for instance, is capable of efficiently extracting short-term local features via dilated convolutions, making it well-suited for transient responses like ERD/ERS in

rhythms. However, its fixed receptive field is ill-equipped for non-uniform rhythmic variations. Transformer excels at modeling global dependencies using self-attention but is less sensitive to abrupt local events. Meanwhile, LSTM adeptly tracks gradual rhythmic trends by modeling state evolution, yet its inherent short-term memory restricts its capacity for global dependency modeling. The complementary nature of these architectures provides a compelling foundation for building robust, high-accuracy classification models. Nevertheless, naive fusion strategies have yielded limited gains. TCN-Transformer hybrids often suffer from poor modular coupling and inadequate fusion of global and local features [

22]. Similarly, TCN-LSTM models, constrained by their serial design and parameter redundancy, struggle to simultaneously capture both long-range dependencies and sudden local rhythms [

23]. These limitations reveal a critical insight: merely stacking modules is insufficient to unlock their respective structural advantages. This underscores the need for a sophisticated synergistic framework that organically integrates and dynamically complements the local perception of TCN, the global correlation of Transformer, and the state tracking of LSTM. Such a framework promises a more profound and comprehensive modeling of the complex temporal dynamics within EEG-MI signals.

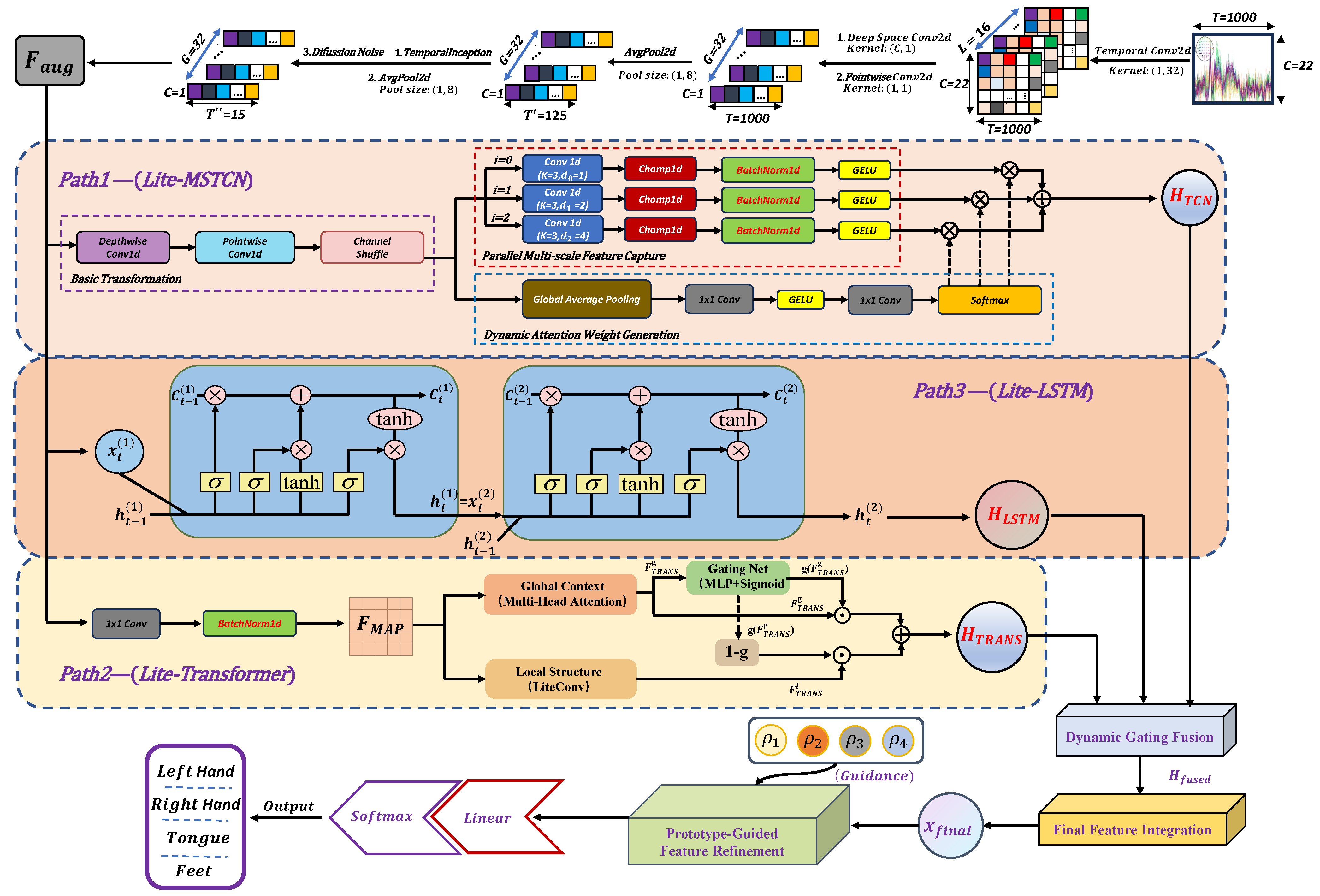

Building upon the insights above, we introduce the Triple-path Heterogeneous Feature Collaboration Network (TPHFC-Net), an end-to-end model for enhanced motor imagery classification. As depicted in

Figure 1, TPHFC-Net is architected with a four-stage progressive framework: (1) Progressive Feature Extractor (PFE): A composite front-end, integrating multi-scale temporal and depthwise separable convolutions, performs initial feature extraction. Subsequently, a denoising diffusion model is employed to bolster the noise robustness of these features. (2) Triple-Path Collaborative Temporal Architecture (TPCTA): The features extracted by PFE are channeled into three parallel streams and processed independently by TCN, Transformer, and LSTM modules. This tripartite design concurrently captures local rhythmic dynamics, models global cross-stage dependencies, and tracks the continuous evolution of signal states. (3) Dynamic Gating Fusion Module (DGFM): A dynamic gating mechanism adaptively learns the importance weights of the heterogeneous features from each stream, followed by a weighted sum fusion that achieves synergistic complementarity and yields an optimized, unified representation. (4) Prototype-Guided Classifier (PGC): In the final stage, a prototype-based attention mechanism guides features toward their corresponding class centers to enhance inter-class separability, after which a fully connected layer performs the final classification.

The primary contributions of this work are threefold:

We introduce a synergistic triple-path temporal modeling mechanism that concurrently leverages TCN, Transformer, and LSTM. This approach holistically models the short-term, global, and state-evolutionary characteristics of EEG-MI signals, thereby enhancing the representational power of the model.

We architect TPHFC-Net, an end-to-end neural network featuring a four-stage progressive framework for accurate motor intent recognition from EEG-MI signals.

We conduct comprehensive experiments on the BCI Competition IV-2a dataset, demonstrating that the proposed TPHFC-Net outperforms existing mainstream baselines in EEG-MI classification accuracy.

2. Related Works

2.1. Classification of Motor-Imagery EEG

EEG-MI classification is a task fundamentally composed of two stages: data preprocessing, followed by model construction and training. The primary goal of preprocessing is to enhance the quality of raw EEG data, a critical step that directly governs the accuracy of all subsequent feature extraction and classification processes. Standard preprocessing techniques include filtering (e.g., band-pass filtering to mitigate high-frequency noise and baseline drift), artifact removal (to correct for ocular interference) and signal normalization, all of which serve to improve the SNR [

24,

25]. Once the data is cleaned, the subsequent stage involves constructing and training a model to extract discriminative features and ultimately classify the user’s intended motor task. It should be noted that the design of this model must be closely adapted to the intrinsic characteristics of the EEG signal.

In the context of MI, EEG signals present three crucial temporal characteristics: (1) Short-term local features: MI-induced neural phenomena, such as the suppression of

(8-13 Hz) and

(13-30 Hz) rhythms, are often transient and concentrated within narrow time windows. Capturing these rapid, localized dynamics is therefore essential for EEG-MI classification [

26]. (2) Global dependency features: Complex imaginary movements can elicit synergistic activity across distant brain regions, characterized by large temporal spans and strong global interdependencies. This manifests as phenomena like delayed synchronization and time-lagged coupling between signals from central and parietal areas [

27]. (3) State-evolutionary features: The MI process itself is not static but unfolds through distinct phases (e.g., preparation, initiation, maintenance, termination). This phased evolution results in an unstable temporal structure where rhythms evolve slowly, exhibiting clear state continuity and long-range temporal dependencies. For instance, the

rhythm might be enhanced during initiation and return to baseline upon termination [

28].

To address the challenge of EEG-MI classification, early research heavily relied on traditional machine learning pipelines. A typical workflow would involve first handcrafting features from the preprocessed data such as frequency energy, PSD or CSP, and then feeding them into a classic classifier like LDA, SVM, or k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) [

29,

30]. Among these, the Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern (FBCSP) framework, proposed by Kai et al. [

31], is arguably the most iconic. By integrating multi-band filtering with spatial feature extraction, FBCSP proved highly effective at enhancing task-relevant discriminative patterns and has seen widespread adoption in practical MI-BCI systems [

32].

Despite their successes, these traditional methods’ heavy reliance on handcrafted features makes them struggle to capture the intricate, non-linear temporal structures inherent in EEG-MI signals, such as the short-term local features, global dependencies, and state-evolutionary dynamics discussed earlier. Furthermore, these methods are often sensitive to noise and exhibit poor generalization. Consequently, they are increasingly unable to meet the stringent demands for accuracy and robustness required in practical application scenarios.

2.2. Motor-Imagery Classification with CNN

The limitations of traditional machine learning spurred the adoption of deep learning, with CNNs yielding significant performance gains in MI classification. Pioneering work by Joseph et al. [

10] in 1994 first applied neural networks to clinical neurophysiological data, developing a classification model that not only outperformed LDA but also demonstrated a distinct advantage in processing non-linear features. Though constrained by the computational bottlenecks and prohibitive training times of the era, this research paved the way for the later dominance of deep learning in MI classification.

A major breakthrough was the design of Shallow ConvNet by Schirrmeister et al. [

11], inspired by the highly successful FBCSP method. This model ingeniously emulated FBCSP’s core components and used temporal convolutions to replicate band-pass filtering and spatial convolutions to mimic CSP’s spatial transformations, thus effectively isolated frequency-specific features and highlighted critical channel combinations, yielding accuracies that rivaled or surpassed FBCSP and firmly validated the superiority of CNNs in this domain. The drive for efficiency led Lawhern et al. [

12] to develop EEGNet, a compact CNN architecture tailored for EEG data. By employing depthwise separable convolutions to decouple temporal and spatial feature learning, EEGNet drastically reduced its parameters while maintaining accuracy comparable to much larger models, establishing it as a cornerstone for lightweight MI classification. Building upon this foundation, Riyad et al. [

33] proposed MI-EEGNet, which integrated an Inception-style architecture for multi-scale feature extraction and an Xception-like structure for enhanced modeling efficiency, thereby achieving stronger generalization across multiple datasets. A subsequent paradigm shift came when Ingolfsson et al. [

13] addressed the persistent issue of causality in time-series modeling. Their EEG-TCNet model marked the first systematic application of TCN to MI classification. By incorporating causal and dilated convolutions, EEG-TCNet efficiently captured long-range temporal dependencies within a compact framework, solidifying TCN as a mainstream technique by delivering high accuracy with minimal parameters.

The advent of EEG-TCNet spurred a new wave of research aimed at extending and refining its architecture, which primarily targeted various aspects of the model. One major thrust was architectural innovation. CIACNet by Liao et al. [

14] introduced a dual-branch convolutional structure with an enhanced convolutional block attention module (CBAM), empowering the TCN to model temporal features at varying semantic levels. Another approach, seen in ASiBLS by Yang et al. [

16], employed a primary-auxiliary branch design to extract global and differential features, using a similarity-guided loss to foster complementary learning and boost generalization. A second area of focus was the optimization of convolutional units to better capture multi-scale features. Salami et al. [

34] augmented the TCN with Inception modules in their EEG-ITNet model, enabling joint spectral-temporal modeling and significantly improving cross-subject recognition. Similarly, the SMT model from Yu et al. [

15] featured a multi-branch separable convolution (MSC) module, where parallel branches with different kernel sizes captured short- and long-term temporal patterns that were subsequently integrated by a unified TCN. The integration of attention mechanisms emerged as another key strategy for refining feature relevance. For example, ETCNet by Qin et al. [

35] synergistically combined an Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module with a TCN. In this design, the ECA module first refines channel-wise representations, which the TCN then processes for temporal modeling, ultimately yielding higher classification accuracy.

As this body of work illustrates, the exceptional capacity of TCN for modeling local temporal dynamics solidifies it as a cornerstone of modern MI classification. Consequently, innovating upon this TCN foundation, whether through novel architectures, advanced feature modeling techniques, or other enhancements, remains the primary frontier for advancing the accuracy, generalization, and robustness.

2.3. TCN Combined with Transformer/LSTM

While TCNs demonstrate a marked ability to extract local temporal features from EEG signals, such as ERD/ERS, their inherent fixed receptive fields constrain the capacity to model long-range dependencies. This limitation makes it difficult for TCN to effectively capture cross-phase, long-term dynamic information within EEG signals. To circumvent this, some studies have integrated the self-attention mechanism of the Transformer model, which can directly model global dependencies across arbitrary time points, thereby enabling a sharper focus on critical temporal information. Song et al. [

17] introduced the EEG Conformer model, which combines convolutional modules for local feature extraction with a Transformer to capture long-distance temporal dependencies, thus judiciously balancing local and global feature modeling capabilities. Expanding on this, Qin et al. [

18] developed M-FANet, which incorporates multiple attention mechanisms to selectively emphasize frequency, spatial, and feature map dimensions for comprehensive multi-feature extraction, while simultaneously using regularization to suppress feature redundancy and bolster robustness and generalization. Furthermore, researchers have explored extending single convolutions to multi-scale variants, integrating them with Transformer to further enhance the model’s ability to represent EEG temporal characteristics. Hang et al. [

19] presented the MCTD model, which extracts local features across diverse frequency ranges using dynamic convolutions, subsequently employing self-attention to model global temporal dependencies, thereby enriching the model’s capacity to express complex temporal features. In comparison, Zhu et al. [

36] proposed IMCTNet, which adopts a more sophisticated multi-scale convolutional architecture and incorporates a channel attention mechanism to adaptively augment the representation capability of features at different scales, ultimately demonstrating superior feature expression and generalization performance.

Despite the Transformer’s notable strengths in modeling global dependencies, it still lacks an efficient mechanism for capturing the dynamic state evolution processes inherent in EEG signals. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, as time-series modeling architectures endowed with memory mechanisms, are proficient at continuously tracking rhythmic changes in brain electrical signals. This makes them particularly well-suited for characterizing the evolving patterns from the initiation to the termination phases within MI tasks. Consequently, researchers have also endeavored to incorporate LSTMs to bolster models’ ability to characterize signal state evolution features. Early investigations by Saputra et al. [

37] directly applied LSTMs for classification following CSP feature extraction to verify their basic utility; however, their experimental results revealed suboptimal adaptability to complex and high-noise EEG signals. Ghinoiu et al. [

20] subsequently introduced a CNN-LSTM-based architecture that leverages convolutional layers to directly extract spatial features from multi-channel EEG signals, with LSTM then modeling their temporal evolution. This hybrid approach considerably enhanced the models’ joint spatio-temporal modeling capabilities. Gui et al. [

21] designed the FBLSTM model, which utilizes filter banks for multi-frequency band information extraction, integrates convolutions for spatial feature extraction, and then employs an attention-equipped LSTM module to model temporal variations. This holistic strategy facilitates the joint learning of frequency, spatial, and temporal domain information, thereby effectively enhancing the synergistic expressive power across multi-modal features.

Evidently, constructing hybrid temporal feature modeling structures that judiciously integrate TCN, Transformer, and LSTM, by capitalizing on their complementary strengths, will enable the comprehensive, joint modeling of short-term local features, global dependencies, and state evolution characteristics of EEG signals. Such an approach holds significant promise for yielding more flexible, refined, and accurate temporal feature representations and classification capabilities.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Pre-Processing

The initial pre-processing stage targets the raw EEG signals for frequency-domain denoising to mitigate various artifacts and improve signal quality. A Finite Impulse Response (FIR) band-pass filter with a passband of 7–35Hz is specifically applied to preserve the MI-related (8–12Hz) and (13–30Hz) rhythms while simultaneously attenuating low-frequency baseline drift and high-frequency EMG artifacts. The inherent linear phase characteristics of the FIR filter are leveraged to ensure the temporal integrity of the EEG signals without phase distortion. Following filtration, the signals are converted into a standardized tensor representation suitable for deep learning applications.

This research utilizes the BCI Competition IV-2a dataset, which contains recordings from nine subjects. Each subject completed 72 trials for four distinct MI tasks: left hand, right hand, feet, and tongue. Each trial comprises time samples recorded from EEG channels. Consequently, the labeled sample set for any given subject can be defined as , where is the data matrix of subject k for the i trial, is the corresponding class label from {left hand, right hand, feet, tongue}, and is the total number of trials per subject. To finalize the pre-processing pipeline, the labeled sample set undergoes global Z-score normalization to ensure a consistent data distribution across all channels and time points, followed by reshaping into the required tensor format to yield a pre-processed dataset ready for model training.

3.2. Progressive Feature Extractor

The proposed PFE derives information-dense, dimensionally compact, and robust spatiotemporal features from the high-dimensional raw data through a three-stage process: decoupling of spatiotemporal feature, multi-scale pattern capture, and diffusion-driven feature enhancement. This process ultimately generates an optimized feature tensor for a subsequent triple-path collaborative temporal architecture.

3.2.1. Decoupling of Spatiotemporal Features

For a given input sample tensor

, the spatiotemporal decoupling process commences by applying a 2D temporal convolution layer with a (1, 32) kernel and

output channels to capture localized temporal patterns, yielding an initial feature map

. To prevent premature entanglement of spatiotemporal information, this map is then fed into a depthwise separable convolution module consisting of a depthwise spatial convolution and a pointwise convolution. Specifically, the depthwise layer utilizes a (

C,1) kernel to independently model inter-channel spatial relationships at each time step. This is followed by a pointwise layer that facilitates cross-channel information exchange and expands the feature channel dimension from

to

. The final output of this decoupling module is formulated as:

where

,

and

represent the kernel weights for the depthwise spatial convolution and pointwise convolution, respectively. This design ensures that each output feature is a non-linear combination of all input channel features, achieving effective cross-channel fusion while preserving the critical separation of spatiotemporal information.

3.2.2. Multi-Scale Pattern Capture

The core of our multi-scale pattern capture strategy is the Temporal Inception module, which enhances feature richness and discriminative power by employing multiple parallel temporal convolution paths. These paths utilize different kernel sizes to achieve varying receptive fields, enabling efficient modeling of multi-temporal resolution features within the signal. For computational efficiency and to broaden the temporal context, the process begins with an average pooling layer with a kernel size of (1,8) to compresses the time dimension from

to

. The pooled feature map

is then fed into four parallel branches with a unified output channel dimension

to capture temporal patterns with different time scales: three grouped-convolutional branches with varying kernel sizes of (1,

) (

) and a max-pooling branch with a kernel size of (1,

) (

=3). Unlike standard convolutions, these convolutional branches employ grouped convolutions by dividing input channels into

H groups for independent computation, which significantly reduces the parameter count. The outputs of the four branches,

, can be expressed as:

Similarly, a second average pooling operation further compresses the time dimension to

. This progressive dimensionality reduction strategy ensures that critical discriminative information is effectively encoded into the feature representation prior to extensive dimensionality reduction. Finally, the resulting feature tensors from these four branches are concatenated along the channel dimension, forming a unified and comprehensive multi-scale feature representation

, denoted as:

3.2.3. Diffusion-Driven Feature Enhancement

To address the challenges of significant noise and inter-subject/session variability inherent in EEG signals, we introduce a diffusion-driven feature enhancement mechanism. In contrast to conventional methods like Dropout and Additive Noise that inject static noise, this mechanism dynamically adapts to the feature state by iteratively refining the noise distribution, thereby enabling a more robust recovery of the underlying signal representation. The mechanism operates iteratively, with each iteration comprising a forward noising phase and a reverse denoising phase based on Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM). In the forward phase, controlled Gaussian noise

is injected into the input feature map

to construct a noisy version

:

where

is defined as the fidelity coefficient,

is a predefined linear noise scale parameter, and

t represents the iteration timestep. As to the reverse phase, it employs a lightweight network

to estimate the injected noise

, which is then used to progressively denoise the feature map:

After

rounds of iterative denoising, this module obtains the final noise correction result

and yields the final feature enhancement term, which is integrated back into the original feature map via a residual connection:

This formulation scales the final injected noise based on both a fixed hyper parameter and the standard deviation of the original features . This adaptively matches the perturbation’s energy to the feature’s intrinsic scale, functioning as a stable and effective regularization method.

Through the entire progressive feature extraction process, the raw input data is compressed and encoded into a highly compact and refined feature tensor .

3.3. Triple-Path Collaborative Temporal Architecture

Upon completion of the progressive feature extraction, the model engages its core computational engine: the Triple-Path Collaborative Temporal Architecture (TPCTA). The TPCTA is founded on the premise that any single temporal modeling paradigm has inherent inductive biases, preventing it from comprehensively capturing all dependencies within a signal [

38]. To overcome this, the TPCTA deploys three parallel paths tailored to target the distinct temporal properties coexisting in EEG signals: short-term local patterns, long-range global dependencies, and continuous state evolution. This multi-path approach ensures a holistic and robust representation of the signal’s intricate temporal characteristics.

3.3.1. Lite-MSTCN: Capturing Local Multi-Scale Dependencies

The first path, Lite-MSTCN, leverages a multi-scale TCN to capture local dependencies across various time scales, such as the

/

rhythmic signatures in EEG signals. Unlike traditional TCNs that sequentially stack dilated convolutions, Lite-MSTCN employs a parallel structure to broaden its multi-scale perception and incorporates an attention mechanism for adaptive, cross-scale feature integration. Initially, a lightweight convolution (LiteConv) layer performs a foundational transformation on the input feature tensor

. By synergizing depthwise and pointwise convolutions for intra-channel temporal modeling and inter-channel feature integration, respectively, which are followed by a channel shuffle operation to enhance cross-channel information exchange, this design boosts the model’s feature representation while markedly reducing computational overhead. The transformed feature tensor

is then channeled into three parallel dilated convolution branches. For branch

, the dilation factor

increases exponentially while the kernel size remains fixed as

. This architectural choice allows the model to achieve an exponentially expanding receptive field without added parametric complexity, facilitating the efficient capture of temporal dependencies at diverse scales. The output of each branch

is further refined through Batch Normalization and a GELU activation function:

where CausalConv1D() represents a causal convolution.

Departing from the static fusion methods (e.g., summation or concatenation) of conventional TCNs, Lite-MSTCN introduces a lightweight channel attention module to dynamically fuse the multi-scale features. The mechanism computes a global context vector via temporal average pooling, which then informs a compact two-layer convolutional network to generate adaptive attention weights

for the three parallel branches. The final output of Lite-MSTCN

is a dynamically weighted combination of the branch features, tailored to the specific characteristics of

:

3.3.2. Lite-Transformer: Capturing Global Contextual Dependencies

To capture global contextual dependencies that extend beyond the fixed receptive fields of TCNs, such as the long-range association between task cues and motor execution, the TPCTA incorporates a second path: a lightweight Transformer (Lite-Transformer). Standard Transformers are prone to overfitting when applied to short-sequence, small-sample EEG datasets, primarily due to their lack of inductive bias. To mitigate this issue, Lite-Transformer fortifies the standard architecture by incorporating convolutional inductive biases and a dynamic gating mechanism. Distinct from variants that rely solely on self-attention or convolutional bias, Lite-Transformer introduces a dynamic fusion mechanism that orchestrates a parallel interplay between global self-attention and local convolutional attention. This allows the model to capture global context while retaining sensitivity to local rhythmic patterns, enhancing its adaptability to non-stationary EEG signals.

The process begins by projecting the input tensor

into a stable feature space via a 1x1 convolution and BatchNorm1d layer, yielding the projected feature map:

where

, and

is the Transformer channels.

is then fed into two parallel branches within Lite-Transformer. The global context branch employs multi-head self-attention (

) to capture non-local dependencies across the entire sequence:

Concurrently, the local structure branch processes the tensor

with a LiteConv module. This step is crucial for injecting key convolutional inductive biases (e.g., translation invariance) into the model, enabling a more robust extraction of local structural features:

Finally, a Linear Attention Gating unit composed of a multi-layer perceptron and a Sigmoid function is utilized to perform a weighted fusion of the features from the two branches. Critically, this unit takes the output of the global context branch as its input to dynamically generate a gating value between 0 and 1 for each time step and feature dimension, which then modulates the combination of the global and local feature streams:

where

and ⊙ represent linear gating operation and element-wise multiplication operation, respectively. This design empowers the model to autonomously arbitrate between the discriminative global context from self-attention and the robust local features from convolutions, based on the input data pattern, thereby resulting in a dynamic and complementary synergy between the two modeling paradigms.

3.3.3. Lite-LSTM: Modeling State Evolution Dynamics

In contrast to the stateless TCN and non-recurrent Transformer, the stateful architecture of LSTM offers a distinct advantage in modeling temporal dynamics and non-stationarity. This rationale underpins the inclusion of a third path, Lite-LSTM, whose inclusion is not for architectural novelty but to serve as the dedicated "state evolution expert". Leveraging its internal cell state and sophisticated gating mechanism, Lite-LSTM models the continuous narrative of the cognitive task, thereby filling a functional void left by the other two paths.

Lite-LSTM consists of a two-layer unidirectional LSTM architecture: the first layer maps the input sequence to a sequence of hidden states, which in turn serves as the input for the second layer to generate the final hidden state sequence. The state transition process can be concisely expressed as:

The output sequence from the second layer serves directly as the final feature representation of Lite-LSTM:

Within the TPCTA framework, Lite-LSTM provides a modeling perspective that is orthogonal to Lite-TCN and Lite-Transformer. It offers a Markovian view of state evolution, enabling the model to capture state evolution memory such as the continuous progression of brain states during a MI task, which are inherently ill-equipped to handle for stateless or non-recurrent architectures. The inclusion of Lite-LSTM is therefore vital for ensuring the architecture’s robustness, further complementing and enhancing comprehensive feature learning capabilities of the model.

3.4. Dynamic Gating Fusion Module

As detailed in

Section 3.3, the TPCTA architecture yields three heterogeneous feature tensors:

,

and

. While dimensionally identical, these tensors encapsulate temporal information derived from three distinct modeling paradigms—convolutional, self-attentional, and recurrent. This heterogeneity demands their fusion into a single, more discriminative representation. To this end, we introduce a dynamic gating fusion module designed to adaptively weight the contribution of each path at every timestep, enabling a context-aware synthesis of these diverse features.

The process begins by concatenating the three heterogeneous features along the channel dimension to form an aggregated feature tensor

. This provides a holistic input to a dedicated lightweight gating network

, which is composed of two 1D convolutional layers with a unified kernel size of 3 and ELU activations. The output of

is then passed through a Softmax function to yield the dynamic gating weights for the three paths

:

where

and each slice quantifies the relative importance of the path features across all timesteps. The final fused representation

is then computed by performing a timestep-wise weighted summation of the path features with these dynamic weights:

This dynamic gating fusion mechanism is essentially a data-driven arbitration strategy that empowers the model to learn complex fusion policies directly from the input data. For instance, the model can learn to amplify the contribution of when local signal rhythms are prominent, or conversely, prioritize when long-range dependencies are more critical.

Following this dynamic fusion, the model proceeds to a final feature integration stage. A 1x1 convolution first projects the dimension of the fused feature from to a more expressive dimension of , followed by normalization and a non-linear activation to enhance the feature representation. The resulting temporal sequence is then condensed into a fixed-dimension feature vector , by applying Global Average Pooling across the temporal dimension, preparing it for the ultimate classification.

3.5. Prototype-Guided Classifierr

The significant non-stationarity and distribution shifts inherent in EEG signals pose a considerable challenge, often rendering linear classifiers insufficient to establish stable inter-class decision boundaries. We address this limitation by introducing a Prototype-Guided Classifier (PGC) that precedes the final linear classifier. The core principle of PGC is to enhance feature separability through a refinement step that leverages a set of learnable class prototypes to optimize feature representations prior to the classification decision.

The PGC maintains a set of learnable class prototypes , where N is the number of classes (four in this task), and the prototype vector can be viewed as a learnable centroid or a canonical exemplar of class n within the feature space. For any given input feature tensor , the module processes it via a two-phase procedure:

Phase 1: Attention Weight Generation. Rather than directly computing input-prototype similarities, the module first feeds the input feature

into a dedicated feed-forward attention network to generate a set of dynamic, input-specific attention weights. These weights then undergo channel-wise refinement via a lightweight depthwise separable convolution before being normalized by a Softmax function to produce the final prototype fusion weights

:

Phase 2: Prototype-Guided Feature Refinement. Using the weights computed in the previous phase, the model performs a weighted sum over the prototype space to construct

, a prototype context vector highly relevant to the current samples:

This vector embodies a context-aware representation synthesized from the global class structure but guided by the sample’s specific affinities,which is then integrated back into the original feature via a scaled residual connection with a learnable scaling factor

, forming the refined feature vector

This refinement process can be interpreted as an adaptive modulation of the original feature vector. It leverages the global manifold of the feature space, as defined by the prototypes, to gently steer each sample’s representation towards its corresponding class region. This process guides the model to learn an enhanced feature space characterized by greater intra-class compactness and inter-class separability.

Finally, the prototype-guided feature vector

is fed into a standard fully-connected layer with weight matrix

and a Softmax function to compute the final posterior class probabilities:

This entire pipeline, from the dynamic gating fusion to the prototype-guided classification, collectively ensures that the model maximally utilizes the heterogeneous temporal features from multiple paths and leads to highly robust and accurate classification.

3.6. Loss Functions and Training Strategy

Given the model’s predicted probabilities from the Softmax layer and the one-hot encoded ground-truth labels, the loss is formulated as:

where

B is the number of samples in a batch,

N is the number of classes, and

is the predicted probability that sample

i belongs to class

n. This formulation is equivalent to the negative log-likelihood of the true class and serves to minimize the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the predicted and true distributions, which effectively reduces their statistical distance and strengthens the discriminative power of the model.

The model’s parameters are optimized by using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). We selected SGD for its well-documented stability and predictable convergence, qualities that are particularly beneficial for maintaining strong generalization performance in models with complex feature fusion architectures. The update rule for the trainable parameters

is given by:

where

denotes the learning rate,

is the gradient of the loss function with respect to

, and

is the weight decay coefficient that enforces L2 regularization.

4. Experiments Details

4.1. Experiment Setup

4.1.1. Experiment Preparations

In our experiments, we utilize a software stack consisted of Python 3.8, PyTorch 2.4.0, and CUDA 12.6, running on a Windows 11 OS. The hardware platform is a workstation equipped with an Intel i7-14700KF CPU, 32GB of DDR4 RAM, and a Tesla P40 GPU.

4.1.2. Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of our proposed model, we conduct extensive experiments on the BCI Competition IV-2a dataset, a widely adopted benchmark for MI classification. The dataset contains samples collected from 9 subjects, each performing 72 trials for four distinct MI tasks (left hand, right hand, both feet, and tongue) with each trial’s data constituting a single sample of points acquired from 22 EEG channels over 1000 time points.

We selected Accuracy and Cohen’s Kappa as the primary metrics for performance evaluation, which are considered among the most prevalent and significant indicators in EEG classification. Accuracy, denoted as

, is formally defined as the ratio of the number of correct predictions to the total number of classification trials:

Herein, N represents the number of classes (specifically, for the four-class MI task), M is the total number of samples, and is the count of true positives for class i, i.e., instances of class i correctly identified as such.

Cohen’s Kappa, a metric particularly effective for imbalanced datasets, evaluates the consistency between model predictions and true labels while explicitly correcting for chance agreement. This makes Kappa a fairer metric for comparing algorithm performance, as it avoids the misleadingly high scores often achieved by models that rely on naive or biased classification strategies. The Kappa coefficient (

) is calculated as follows:

In this equation, denotes the overall accuracy (observed agreement). The term quantifies the hypothetical probability of chance agreement and is defined as , where and denote the total number of actual instances and predicted instances for class i, respectively.

4.1.3. Implementation Details

The hyperparameters for model training are detailed in

Table 1. The model was trained using the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001. A batch size of 32 was selected to balance maximizing the GPU’s parallel processing capability for higher computational throughput against the constraint of the hardware memory capacity, thereby preventing out-of-memory (OOM) errors. With these settings, the model consistently achieved convergence within 2000 epochs.

4.2. Comparison with SOTA

As shown in

Table 2, our proposed model achieves an average classification accuracy of 82.45%, demonstrating a significant performance gain over classic models such as EEGNet (+10.05%), EEG-ITNet (+5.71%), and EEG-TCNet (+5.10%). This superiority stems from overcoming the limitations of conventional methods, which rely on convolutional networks that primarily capture short-term local features (e.g.,

rhythms) while overlooking other critical temporal dynamics. This advantage also extends beyond classic benchmarks to recent state-of-the-art (SOTA) works, including MBCNN-EATCFNet (2025), DMSACNN (2025), and MSSAN (2024). While these advanced methods enhance the TCN framework with techniques like multi-branch structures, multi-scale convolutions, or attention mechanisms, they still adopt a one-sided approach, failing to achieve comprehensive temporal modeling. In contrast, our model introduces a three-path synergistic architecture that uniquely integrates three distinct modeling paradigms: leveraging TCN for short-term local features, Transformer for long-range global dependencies, and LSTM for state evolution dynamics. By adaptively fusing these complementary features derived from convolutional, self-attention, and recurrent paradigms, our model generates a more discriminative representation, leading to a substantial boost in classification performance.

The model’s superiority is further corroborated by its Kappa coefficient. With an average Kappa value of 0.77, it surpasses all other models listed in

Table 2 and confirms a higher degree of agreement between its predictions and the true labels. This metric is particularly insightful because it quantifies agreement while accounting for chance, meaning the improved Kappa score indicates substantially enhanced reliability and stability in the model predictions. This implies that our model excels not only in capturing latent data patterns and minimizing misclassifications but also in demonstrating robust performance in practical applications. Consequently, the proposed model is distinguished by its dual advantages in accuracy and reliability, highlighting its significant practical utility and strong potential for widespread adoption.

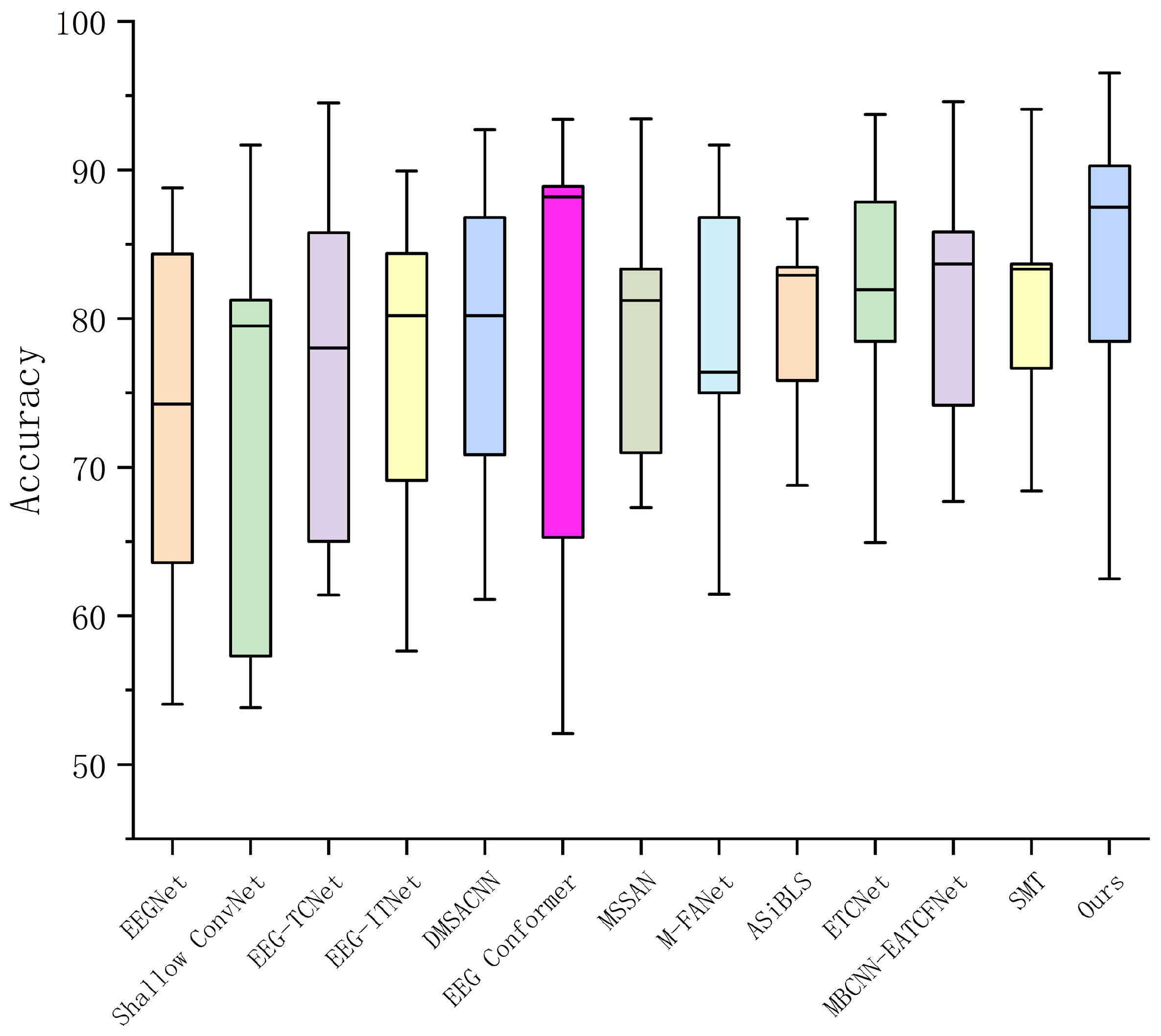

Figure 2 provides a visual performance assessment via box plots, which illustrates the accuracy distribution of our model and competing models across all subjects. An analysis of the plots reveals that our model demonstrates comprehensive superiority to other models across key statistical metrics including the median (horizontal line), quartiles (box edges), and range (whiskers). However, it is noteworthy that certain models exhibit strong outlier performance. For instance, the EEG Conformer achieves a higher maximum accuracy on some subjects, while MSSAN and M-FANet exhibit greater stability (i.e., lower variance) in some cases, indicating their efficacy under particular conditions. Despite these isolated strengths, our model achieves a superior overall balance between peak performance and consistency across the cohort, which lies in an innovative temporal architecture that effectively harmonizes diverse modeling paradigms.

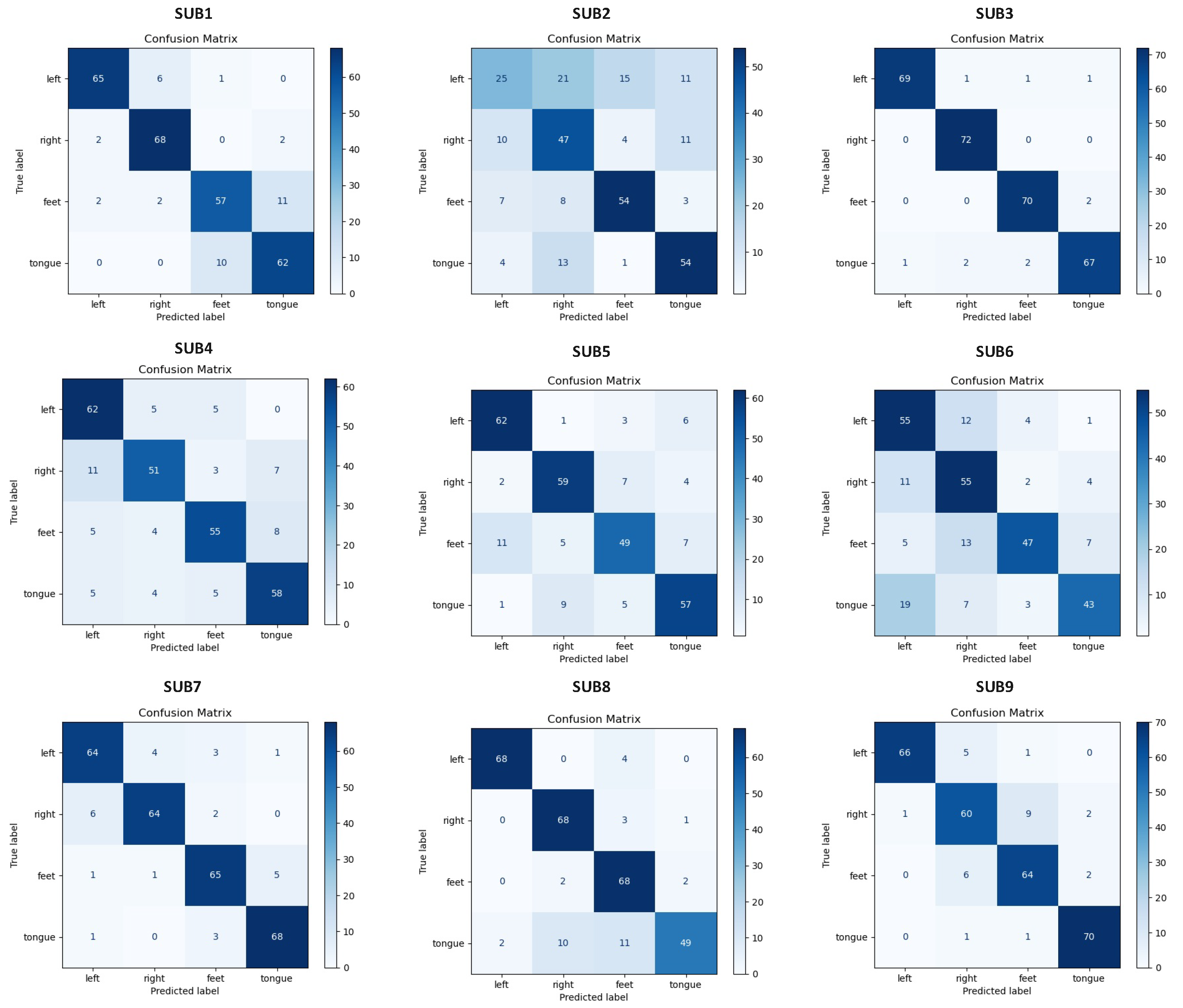

Figure 3 details the classification outcomes for each subject on MI task through confusion matrices, where the main diagonal signifies correct predictions and off-diagonal elements indicate misclassifications between true (Y-axis) and predicted (X-axis) labels. The results reveal a significant performance divergence among subjects. Subjects 3, 7, and 9 demonstrated robust performance, characterized by high accuracy for the left/right-hand classes and minimal inter-class confusion. Conversely, Subjects 2, 5, and 4 exhibited suboptimal results, with particularly high error rates for the ’Feet’ class. This is exemplified by Subject 2, who showed the most pronounced performance degradation, with seven ’Feet’ trials misclassified as ’Left Hand’. We attribute this inter-subject performance variance to three primary factors: signal quality, individual neurophysiological differences, and the representativeness of the training data. Superior performance in certain subjects likely correlates with high SNR and more distinct features , whereas poor results may stem from noise-corrupted signals that impede effective feature extraction, a challenge especially prominent for the more complex ’Feet’ and ’Tongue’ MI tasks. Furthermore, inherent variability in individual brainwave patterns and muscle artifacts can lead to subject-specific model performance. The success with Subject 3, for instance, may be due to their highly discernible and stable EEG patterns. Finally, the comprehensiveness of the training data is critical. If the training set inadequately captures the full spectrum of a subject’s unique EEG signatures, the model’s generalization capabilities will inevitably be compromised.

4.3. Ablation Study

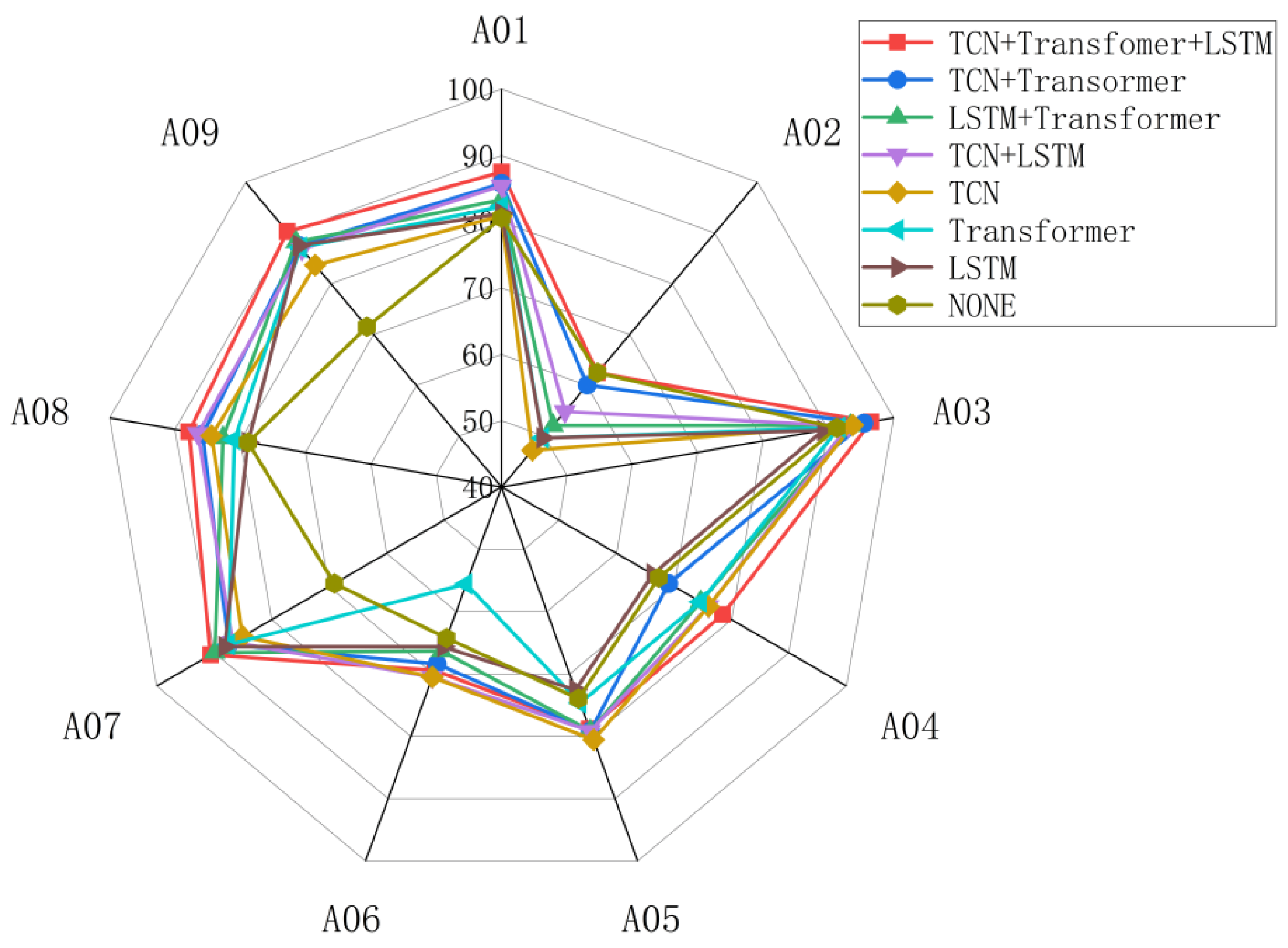

An ablation study was conducted to systematically evaluate the contributions of the TCN, Transformer, and LSTM modules. Quantitative results (mean accuracy and kappa) are summarized in

Table 3, with per-subject accuracy detailed in

Figure 4.The baseline model, stripped of all three temporal feature extraction paths, established a performance floor at 73.27% accuracy and 0.66 kappa. Individually enabling each path validated their distinct and complementary roles: the TCN path yielded the largest gain (+4.74% accuracy, +0.05 kappa) by capturing local temporal patterns; the Transformer path contributed by modeling global dependencies (+2.73% accuracy, +0.02 kappa); and the LSTM path offered benefits by tracking state evolution (+2.19% accuracy, +0.01 kappa). The synergy between these paradigms was evident in dual-path configurations. Fusing TCN with either Transformer or LSTM via dynamic gating consistently outperformed single-path models, boosting accuracy by at least 1.89%.

Figure 4 corroborates this, showing that these dual-path combinations consistently outperform single-path across most subjects. This synergy suggests that the integration of diverse temporal modeling paradigms effectively overcomes the inherent blind spots of any single approach. Notably, the TCN module was crucial for stabilizing performance on non-stationary subjects, where standalone Transformer or LSTM models faltered. This stabilizing effect is also reflected in the reduced cross-subject performance volatility observed in the TCN+Transformer combination.

The full tripartite architecture, leveraging adaptive fusion of all three paths, culminated in the highest performance, reaching a mean accuracy of 82.45% and a kappa of 0.77. This configuration not only surpassed all sub-models in aggregate metrics but also delivered a more balanced and robust performance profile across all nine subjects, as seen in

Figure 4. This demonstrates the architecture’s superior adaptability in feature fusion, which mitigates dependency on any signal modeling paradigm. Collectively, the ablation study provides compelling evidence for the architectural rationale of our model, validating the potent synergy achieved by the fusion of TCN, Transformer, and LSTM for MI classification.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we present TPHFC-Net, an end-to-end neural network built upon a triple-path collaborative temporal architecture for the four-class MI classification task. The model concurrently leverages TCN, Transformer, and LSTM to capture short-term local, long-range global, and state evolution features from EEG-MI signals, respectively. By integrating these heterogeneous yet complementary features through a adaptive fusion module, TPHFC-Net creates a highly discriminative representation. This advanced representation enables superior classification performance by effectively addressing the limitations of incomplete temporal modeling and suboptimal performance in prior methods. Extensive experiments on the BCI Competition IV-2a dataset validated our approach, demonstrating that TPHFC-Net significantly outperforms existing mainstream models.

The central finding of this study is that the synergistic integration of diverse temporal modeling paradigms, rather than their simple concatenation, can unlock a new performance ceiling for EEG-MI classification. However, despite its strong performance, TPHFC-Net has two primary limitations. First, its parallel architecture introduces a significant computational overhead. Second, its feature modeling is predominantly confined to the temporal domain. These limitations point to clear directions for future research. Future work should focus on multi-domain fusion, integrating spatial and frequency-domain information to complement the temporal features. Furthermore, optimizing the model through techniques like network pruning or knowledge distillation could enhance its computational efficiency, making it more viable for real-world MI-BCI applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J.; data curation, D.W.; formal analysis, Y.J. and C.L.; methodology, C.D. and Y.J.; software, Y.J.; supervision, C.L.; validation, D.W.; writing–original draft, Y.J. and C.D.; writing–review and editing, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is partially supported by the Jiangsu Province Industry-University-Research Collaboration Project (Grant No. BY20230186) .

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are hugely grateful to the possible anonymous reviewers for their careful, unbiased, and constructive suggestions with respect to the original manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shenoy Handiru, V.; Vinod, A.; Guan, C. EEG Source Imaging of Movement Decoding: The State of the Art and Future Directions. IEEE Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Magazine 2018, 4, 14–23. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Jin, J.; Xu, R.; Wang, X.; Cichocki, A. Variance characteristic preserving common spatial pattern for motor imagery BCI. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2023, Volume 17 - 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tung, S.W.; Guan, C.; Ang, K.K.; Phua, K.S.; Wang, C.; Zhao, L.; Teo, W.P.; Chew, E. Motor imagery BCI for upper limb stroke rehabilitation: An evaluation of the EEG recordings using coherence analysis. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference 2013, 2013, 261—264. [CrossRef]

- Khademi, Z.; Ebrahimi, F.; Kordy, H.M. A review of critical challenges in MI-BCI: From conventional to deep learning methods. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2023, 383, 109736. [CrossRef]

- Orban, M.; Elsamanty, M.; Guo, K.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H. A Review of Brain Activity and EEG-Based Brain–Computer Interfaces for Rehabilitation Application. Bioengineering 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Mamun, K.A.; Ahmed, K.; Mostafa, R.; Naik, G.R.; Darvishi, S.; Khandoker, A.H.; Baumert, M. Progress in Brain Computer Interface: Challenges and Opportunities. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 2021, Volume 15 - 2021. [CrossRef]

- Samek, W.; Kawanabe, M.; Müller, K.R. Divergence-Based Framework for Common Spatial Patterns Algorithms. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering 2014, 7, 50–72. [CrossRef]

- Lotte, F.; Congedo, M.; Lécuyer, A.; Lamarche, F.; Arnaldi, B. A review of classification algorithms for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering 2007, 4, R1. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, E.M.; San-Martin, R.; Fraga, F.J. Comparison of subject-independent and subject-specific EEG-based BCI using LDA and SVM classifiers. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2023, 61, 835–845. [CrossRef]

- Sgro, J. Neural network classification of clinical neurophysiological data for acute care monitoring. In Proceedings of the A Decade of Neural Networks: Practical Applications and Prospects, 1994, p. 95–106.

- Tibor Schirrmeister, R.; Springenberg, J.T.; Fiederer, L.D.J.; Glasstetter, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Tangermann, M.; Hutter, F.; Burgard, W.; Ball, T. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for EEG decoding and visualization. arXiv e-prints 2017, p. arXiv:1703.05051, [arXiv:cs.LG/1703.05051]. [CrossRef]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering 2018, 15, 056013. [CrossRef]

- Ingolfsson, T.M.; Hersche, M.; Wang, X.; Kobayashi, N.; Cavigelli, L.; Benini, L. EEG-TCNet: An Accurate Temporal Convolutional Network for Embedded Motor-Imagery Brain–Machine Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), 2020, pp. 2958–2965. [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Miao, Z.; Liang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, C. A composite improved attention convolutional network for motor imagery EEG classification. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2025, Volume 19 - 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cao, D.; Zhou, P. Motor Imagery EEG Decoding Based on Multi-Branch Separable Temporal Convolutional Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 China Automation Congress (CAC), 2024, pp. 6058–6063. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, L. An adaptive session-incremental broad learning system for continuous motor imagery EEG classification. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2025, 63, 1059–1079. Received 17 June 2024; Accepted 08 November 2024; Published 29 November 2024; Issue date April 2025, https://. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, B.; Gao, X. EEG Conformer: Convolutional Transformer for EEG Decoding and Visualization. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023, 31, 710–719. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yang, B.; Ke, S.; Liu, P.; Rong, F.; Xia, X. M-FANet: Multi-Feature Attention Convolutional Neural Network for Motor Imagery Decoding. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2024, 32, 401–411. [CrossRef]

- Hang, W.; Wang, J.; Liang, S.; Lei, B.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Chen, B.; Qin, J. Multiscale Convolutional Transformer with Diverse-aware Feature Learning for Motor Imagery EEG Decoding. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems 2025, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ghinoiu, B.; Vlădăreanu, V.; Travediu, A.M.; Vlădăreanu, L.; Pop, A.; Feng, Y.; Zamfirescu, A. EEG-Based Mobile Robot Control Using Deep Learning and ROS Integration. Technologies 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Tian, Z.; Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Wang, Q. FBLSTM: A Filter-Bank LSTM-based deep learning method for MI-EEG classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication Technology (SPCT 2022), Harbin, China, 2023; Vol. 12615, Proceedings of SPIE, the International Society for Optical Engineering, pp. 126151W–126151W–6. Presented at the International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication Technology (SPCT 2022), https://. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tian, A.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Early Time Series Classification Using TCN-Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 4th International Conference on Civil Aviation Safety and Information Technology (ICCASIT), 2022, pp. 1079–1082. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Fan, M.; Yang, X.; et al. Research on Emotion Recognition Model Based on ConvTCN-LSTM-DCAN Model with Sparse EEG Channels. Research Square 2024. Preprint (Version 1), https://. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Bian, G.B.; Tian, Z. Removal of Artifacts from EEG Signals: A Review. Sensors 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Abibullaev, B.; Keutayeva, A.; Zollanvari, A. Deep Learning in EEG-Based BCIs: A Comprehensive Review of Transformer Models, Advantages, Challenges, and Applications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 127271–127301. [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.J.; Miner, L.A.; Vaughan, T.M.; Wolpaw, J.R. Mu and Beta Rhythm Topographies During Motor Imagery and Actual Movements. Brain Topography 2000, 12, 177–186. [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, E.; Hosseini, M. Transformers in EEG Analysis: A Review of Architectures and Applications in Motor Imagery, Seizure, and Emotion Classification. Sensors 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, F.; Sun, S.; Yao, D.; Xu, P.; Zhang, T. Brain state and dynamic transition patterns of motor imagery revealed by the Bayes hidden Markov model. Cognitive Neurodynamics 2024, 18, 2455–2470. [CrossRef]

- Motor-Imagery EEG Signals Classificationusing SVM, MLP and LDA Classifiers. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT) 2021, 12, 3339–3344. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Chugh, N. Signal processing techniques for motor imagery brain computer interface: A review. Array 2019, 1-2, 100003. [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.K.; Chin, Z.Y.; Zhang, H.; Guan, C. Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern (FBCSP) in Brain-Computer Interface. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), 2008, pp. 2390–2397. [CrossRef]

- Avelar, M.C.; Almeida, P.; Faria, B.M.; Reis, L.P. Applications of Brain Wave Classification for Controlling an Intelligent Wheelchair. Technologies 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Riyad, M.; Khalil, M.; Adib, A. MI-EEGNET: A novel convolutional neural network for motor imagery classification. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2021, 353, 109037. [CrossRef]

- Salami, A.; Andreu-Perez, J.; Gillmeister, H. EEG-ITNet: An Explainable Inception Temporal Convolutional Network for Motor Imagery Classification. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 36672–36685. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, W.; Shi, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. ETCNet: An EEG-based motor imagery classification model combining efficient channel attention and temporal convolutional network. Brain Research 2024, 1823, 148673. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, A.; Tan, X.; Zhang, J. An improved multi-scale convolution and Transformer network for EEG-based motor imagery decoding. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2025, 16, 4997–5012. [CrossRef]

- Saputra, M.; Setiawan, N.A.; Ardiyanto, I. Deep Learning Methods for EEG Signals Classification of Motor Imagery in BCI. IJITEE (International Journal of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering) 2019, 3, 80. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, D.; Yoon, S. A comprehensive survey of deep learning for time series forecasting: architectural diversity and open challenges. Artificial Intelligence Review 2025, 58, 216. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xing, X.; Yang, T.; Yu, Z.; Xiao, B.; Wang, G.; Wu, W. DMSACNN: Deep Multiscale Attentional Convolutional Neural Network for EEG-Based Motor Decoding. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2025, 29, 4884–4896. [CrossRef]

- Chunduri, V.; Aoudni, Y.; Khan, S.; Aziz, A.; Rizwan, A.; Deb, N.; Keshta, I.; Soni, M. Multi-scale spatiotemporal attention network for neuron based motor imagery EEG classification. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2024, 406, 110128. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Wang, L.; Xia, G.; Deng, J. MBCNN-EATCFNet: A multi-branch neural network with efficient attention mechanism for decoding EEG-based motor imagery. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2025, 185, 104899. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).