1. Introduction

Robust and accurate estimation of camera motion is a cornerstone of many robotics and augmented reality applications. Visual Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (Visual SLAM) systems—particularly those based on sparse, feature-driven pipelines—have achieved remarkable success in largely static scenes by leveraging geometric constraints and robust estimation techniques. However, many real-world environments are inherently dynamic: people, vehicles, and other moving objects frequently appear in the camera’s field of view and violate the static-world assumption that underpins conventional SLAM back-ends. Such dynamic elements lead to incorrect feature associations, biased pose estimates, and, ultimately, degraded mapping and localization performance.

A variety of strategies have been developed to mitigate the negative effects of dynamic elements. Classical approaches often rely on robust estimators (e.g., RANSAC) to discard inconsistent matches, or they use motion segmentation and flow clustering to separate moving object regions from the static scene. Recent methods exploit semantic segmentation to mask regions likely to belong to movable classes (e.g., people or vehicles) before pose estimation. While effective in many settings, these solutions have important limitations: RANSAC-based schemes can only reject gross outliers and may fail when moving objects cover a large image portion; flow-clustering approaches can misclassify background parallax as object motion; and semantic methods require trained networks, annotated data, and may not generalize across diverse domains or rare object classes.

In contrast, epipolar geometry provides a principled, camera-motion-centric constraint that relates corresponding image points between two views. If the scene is static, the correspondence of a point in the first image must lie on the epipolar line induced by that point in the second image. Prior work has exploited violations of this constraint using point-to-line distances or Sampson residuals to detect dynamic correspondences. However, positional deviation alone does not fully capture motion inconsistency: measurement noise, repetitive textures, and small baselines may lead to significant positional residuals even for static points, and conversely, points on certain scene configurations may exhibit small positional errors while their motion direction contradicts the camera-induced flow.

Motivated by these observations, we propose to complement positional epipolar deviation with a directional consistency test: rather than solely measuring how far an observed correspondence lies from its epipolar line, we measure whether the observed optical-flow direction is aligned with the epipolar line tangent expected from the camera motion. Intuitively, for a truly static 3D point, the image-space displacement caused by camera ego-motion should be parallel (or antiparallel) to the corresponding epipolar line; independent object motion yields image displacements whose directions are inconsistent with that epipolar tangent. This directional cue is largely orthogonal to positional residuals and is less sensitive to small translational baselines and certain noise modalities. Furthermore, it is purely geometric and therefore does not rely on learned models or semantic priors.

In this work we instantiate this idea within a lightweight, feature-based pipeline suitable for integration into existing Visual SLAM systems. We introduce the Epipolar Direction Consistency (EDC) metric, a cosine-similarity measure between an observed sparse optical-flow vector (computed from matched ORB keypoints) and the epipolar line tangent derived from a RANSAC-estimated fundamental matrix. To improve robustness we (i) combine EDC with classical epipolar deviation measures (e.g., Sampson distance) into a hybrid score, (ii) employ adaptive, data-driven thresholds based on the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD), (iii) refine geometry iteratively by recomputing the epipolar model after removing dynamic candidates, and (iv) apply short-window temporal voting to suppress sporadic misclassifications. The resulting method requires no training data, introduces minimal computational overhead to an ORB-style pipeline, and is especially effective when dense semantic segmentation or heavy learning infrastructure is unavailable.

We validate the approach on standard dynamic sequences from the TUM RGB-D benchmark and perform ablation studies to quantify the contribution of directional vs. positional cues, the effect of adaptive thresholding, and the benefits of iterative refinement and temporal filtering.

2. Related Work

2.1. Visual SLAM in Dynamic Environments

Conventional visual SLAM algorithms such as ORB-SLAM2 [

1], LSD-SLAM [

2], and DSO [

3] assume a static environment where all feature correspondences are induced solely by camera motion. Under this assumption, feature-based methods perform robust pose estimation by maximizing geometric consistency among static landmarks. However, in dynamic environments containing moving people, vehicles, or other objects, the static-world assumption is violated. As a result, traditional feature tracking leads to inconsistent reprojection errors and biased pose estimates.

To address these challenges, several strategies have been developed to mitigate the influence of dynamic elements. Some methods apply robust estimation schemes such as M-estimators, RANSAC variants, or outlier suppression in bundle adjustment to reduce the impact of motion outliers. Although these techniques handle small-scale dynamic disturbances effectively, they tend to fail when moving objects occupy a significant portion of the image or when motion parallax from dynamic regions mimics background motion.

2.2. Motion and Geometry-Based Dynamic Detection

Another line of research exploits epipolar geometry to identify inconsistent motion directly from feature correspondences. Early works computed the epipolar constraint residual—the perpendicular distance from an observed match to its corresponding epipolar line—to detect dynamic features. For instance, Scaramuzza

et al. [

4] utilized this principle in visual odometry to reject inconsistent correspondences, and Sun

et al. [

5] extended this idea for stereo SLAM by thresholding the Sampson distance. These geometric methods require only two-view correspondences and avoid any semantic prior, making them efficient and broadly applicable. However, using only positional deviation can be unreliable when the camera undergoes small translations or when image noise leads to small, yet inconsistent, displacements.

To improve robustness, some authors combined geometric consistency with optical flow statistics. Tan

et al. [

6] and Kim

et al. [

7] analyzed optical flow magnitude and direction to segment independently moving regions, but these methods generally assume smooth, dense motion fields, which are difficult to estimate accurately under texture-poor conditions or fast camera motion.

More recent geometric approaches, such as DynaSLAM [

8] and DS-SLAM [

9], integrate geometric outlier rejection with learned motion cues. Although these hybrid strategies demonstrate high robustness, they require substantial computation and pre-trained semantic networks.

In contrast, the present work adopts a purely geometric perspective but introduces a new directional dimension to the classical epipolar constraint. Instead of relying solely on distance residuals, we exploit the alignment between the observed optical-flow vector and the epipolar line tangent, arguing that this angular consistency carries independent information about motion validity. This approach bridges the gap between traditional epipolar deviation and motion-flow-based reasoning while maintaining computational simplicity.

2.3. Learning-Based and Semantic Approaches

Learning-based dynamic detection has recently emerged as an alternative to purely geometric methods. StaticFusion [

10] and Detect-SLAM [

11] employ deep neural networks for semantic segmentation, masking regions likely to correspond to dynamic object classes before pose optimization. Similarly, DynaSLAM combines Mask R-CNN-based semantic segmentation with multi-view geometry to refine static point selection. While such methods achieve strong performance in structured scenes, their generalization across domains remains limited: trained models may fail in unseen environments, low-light conditions, or for novel object types. Moreover, these pipelines introduce significant computational overhead, hindering real-time deployment in lightweight systems or embedded platforms.

In contrast, several unsupervised or self-supervised methods have been proposed to learn dynamic object masks directly from motion cues (e.g., Casser

et al. [

12], Li

et al. [

13]). Despite reducing dependency on manual annotations, these models still require extensive pretraining and do not provide explicit geometric interpretability.

2.4. Position of the Proposed Work

Compared to existing studies, our method maintains the efficiency and interpretability of geometric models while introducing a novel directional consistency measure that directly evaluates whether a feature’s optical flow aligns with its epipolar tangent. Unlike semantic or deep-learning approaches, the proposed Epipolar Direction Consistency (EDC) metric requires no training data or object models. Unlike traditional geometric deviation metrics that depend solely on point-to-line distances, EDC incorporates the flow direction as a complementary cue, providing increased robustness against noise, small baselines, and weak textures. Furthermore, our adaptive thresholding and temporal consistency strategies ensure that the method generalizes well across different dynamic scenarios without dataset-specific tuning. As such, the proposed approach establishes a lightweight, explainable, and training-free solution to the dynamic-feature rejection problem, suitable for integration into existing visual SLAM pipelines.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

The proposed method aims to identify and reject dynamic feature correspondences between consecutive monocular images based solely on geometric and motion consistency. Unlike semantic or learned approaches, our pipeline leverages only low-level visual cues—specifically, ORB feature correspondences, their optical flow vectors, and the associated epipolar geometry. The algorithm consists of four principal stages: (1) feature detection and matching, (2) optical flow estimation, (3) epipolar geometry computation, and (4) epipolar direction consistency (EDC) evaluation for dynamic/static classification.

3.2. Feature Extraction and Matching

In visual SLAM systems, feature extraction and matching play a fundamental role in establishing reliable correspondences between consecutive frames. Distinctive local features are detected and described to ensure invariance against scale, rotation, and illumination changes. Matching these features across frames allows the estimation of camera motion and scene structure. Robust feature matching is especially critical in dynamic environments, where moving objects can introduce erroneous correspondences that degrade pose estimation accuracy.

For each consecutive image pair

, ORB features [

14] are extracted due to their computational efficiency and robustness to illumination and viewpoint variations. Let

denote the homogeneous coordinates of the

i-th keypoint in frame

t. Feature descriptors are matched between frames using Hamming distance, and bidirectional matching with Lowe’s ratio test is applied to eliminate ambiguous correspondences. The resulting set of tentative matches is denoted as

3.3. Optical Flow Estimation

Optical flow represents the apparent motion of brightness patterns between consecutive image frames, providing pixel-wise motion information in the image plane. It is based on the assumption of brightness constancy, which states that the intensity of a moving point remains constant over time. By solving the spatial and temporal image gradient constraints, the displacement vector of each feature can be estimated. In this study, optical flow is employed to capture the motion direction and magnitude of matched ORB features, allowing for a geometric analysis of their consistency with the epipolar constraint.

To obtain subpixel-accurate motion vectors for matched features, the Lucas–Kanade optical flow method [

15] is applied in a pyramidal scheme. This yields a flow vector

representing the apparent displacement of the

i-th feature between frames. This step serves both to refine ORB-based correspondences and to provide directional motion information necessary for subsequent epipolar consistency analysis.

3.4. Epipolar Geometry Estimation

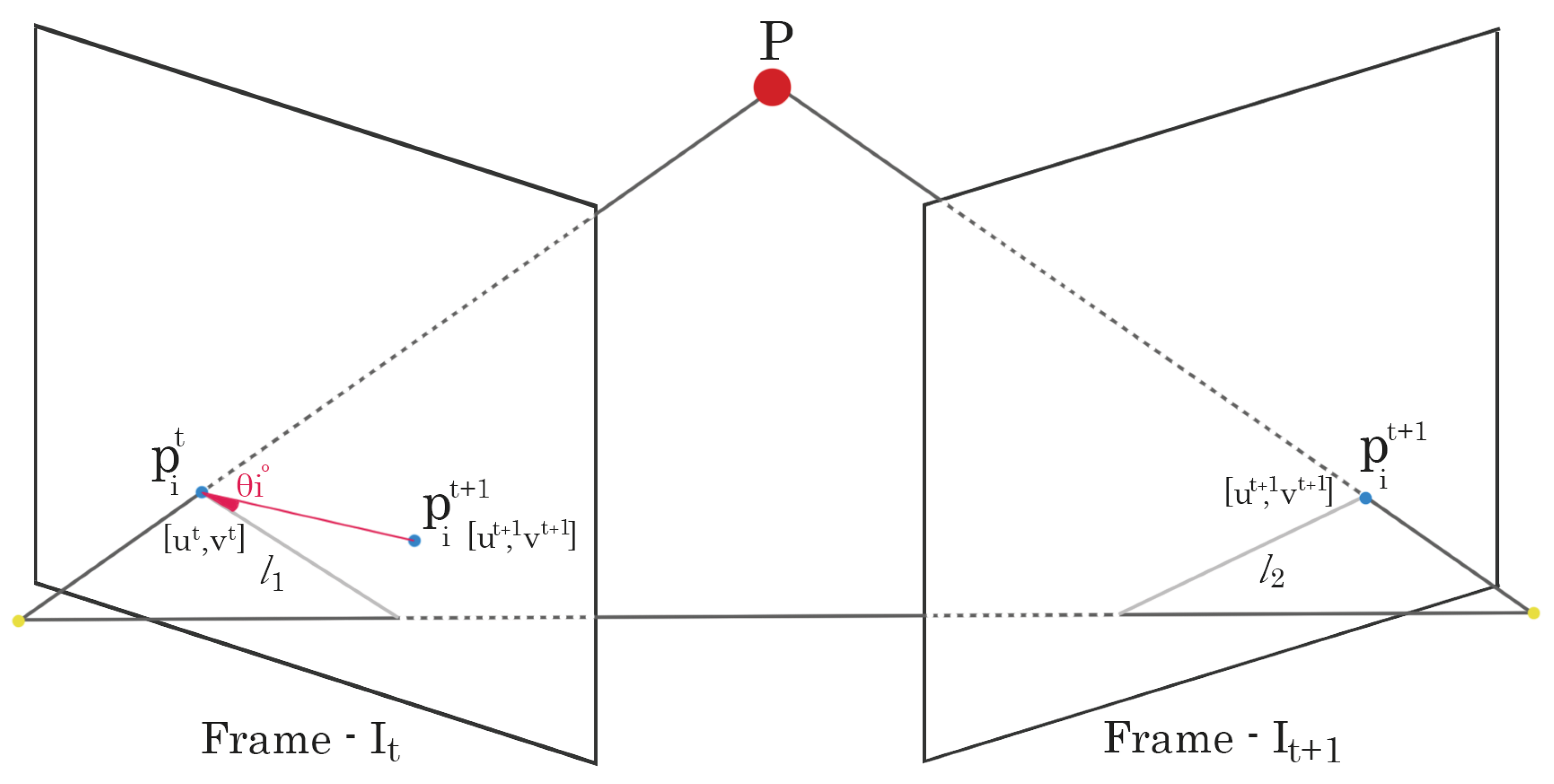

Epipolar geometry defines the intrinsic projective relationship between two camera views observing the same 3D scene shown as

Figure 1. It constrains the position of corresponding image points through the

epipolar constraint, expressed as

where

F denotes the fundamental matrix relating points

and

in consecutive frames. This constraint ensures that the projection of a 3D point in one view lies on a specific epipolar line in the other view. Estimating the fundamental matrix thus provides the geometric foundation for camera pose recovery and consistency analysis between matched features.

The geometric relation between the two camera views is characterized by the fundamental matrix

, estimated from

using the normalized eight-point algorithm with RANSAC [

16]. For any correspondence

, the associated epipolar line in the second view is given by

The epipolar constraint implies that an ideal static correspondence satisfies

In the presence of dynamic objects, this constraint is violated, producing larger residuals in both spatial and directional domains.

3.5. Epipolar Direction Consistency (EDC)

While the conventional Sampson distance measures the perpendicular distance between

and its corresponding epipolar line, our approach incorporates directional information of the optical flow vector. Specifically, we define the

epipolar tangent direction for the

i-th match as

which is orthogonal to the line normal

.

The directional alignment between the observed optical flow

and

is quantified as

For static points, optical motion arises primarily from camera ego-motion, and thus

should align closely with

, resulting in small

. Conversely, independently moving (dynamic) objects often yield large directional deviations.

3.6. Dynamic/Static Classification

Each correspondence is classified using an adaptive threshold

derived from the median angular deviation within the current frame pair:

where

denotes the median absolute deviation and

k is a robustness parameter empirically set between

and

. The dynamic mask is thus defined as

Points labeled as

constitute the static feature set used for subsequent pose estimation or mapping.

3.7. Algorithm Summary

The complete EDC-based dynamic feature rejection algorithm can be summarized as follows:

|

Algorithm 1:Epipolar-Angle Based Dynamic Feature Suppression |

-

Require:

Consecutive RGB frames and

-

Ensure:

Static feature set for pose estimation - 1:

Extract ORB keypoints and descriptors from and . - 2:

Match ORB descriptors to obtain initial correspondences . - 3:

Refine matches using pyramidal Lucas–Kanade sparse optical flow to obtain flow vectors . - 4:

Estimate the fundamental matrix using RANSAC. - 5:

for each correspondence do

- 6:

Compute the epipolar line . - 7:

Extract its tangent direction . - 8:

Compute the angular deviation . - 9:

end for - 10:

Compute adaptive threshold . - 11:

Mark feature i as dynamic if and . - 12:

Construct static set . - 13:

Use only the static set for pose estimation and SLAM updates. |

This procedure enables robust separation of dynamic and static features without relying on semantic information or learning-based priors. By incorporating directional epipolar consistency, the method reduces the risk of misclassification in scenes with weak parallax or small baselines, while maintaining real-time computational efficiency.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Dataset and Implementation Details

The proposed Epipolar Direction Consistency (EDC) approach was evaluated on the dynamic sequences of the TUM RGB-D benchmark [

17], namely

freiburg3_walking_xyz,

freiburg3_walking_ halfsphere, and

freiburg3_walking_rpy. These sequences are characterized by handheld camera motion in indoor scenes with one or more independently moving pedestrians, providing an ideal testbed for dynamic-scene SLAM evaluation.

All experiments were implemented in MATLAB R2023b using the Computer Vision Toolbox. The hardware platform consisted of an Intel Core i5 CPU with 16 GB RAM, running at 2.6 GHz. Default parameters were adopted for ORB feature extraction, and the pyramidal Lucas–Kanade optical flow method was employed for subpixel motion estimation. The robust adaptive thresholding factor in Equation (9) was empirically set to unless otherwise specified. Each configuration was executed three times per sequence to account for stochastic effects introduced by RANSAC sampling, and averaged metrics are reported.

4.2. Qualitative Evaluation

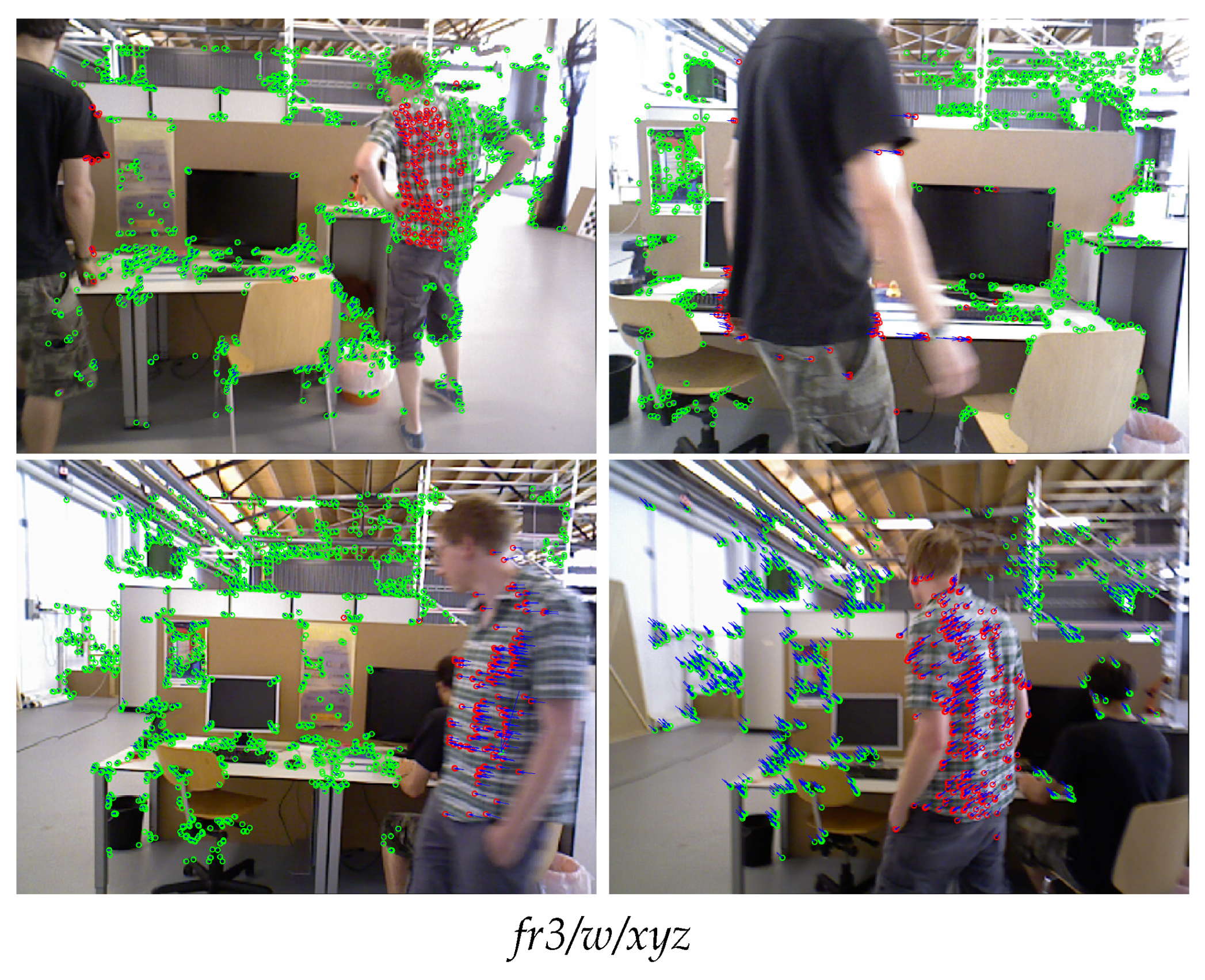

A visual illustration of the dynamic-feature suppression capability of the proposed method is presented in

Figure 2. Features classified as static are rendered in green, while dynamic ones appear in red. As shown across all three sequences, the EDC criterion successfully filters out correspondences belonging to moving pedestrians and retains features on the static background, even when the moving regions occupy a large portion of the frame.

In scenes such as freiburg3_walking_halfsphere, where the camera executes rotational motion with limited translation, conventional epipolar residuals alone are prone to misclassification due to weak parallax. In contrast, the proposed directional test leverages angular consistency, enabling reliable identification of dynamic regions without relying on large baselines or dense motion fields. Furthermore, visual inspection of sequential frames shows that rejected points exhibit coherent spatial clustering over time, reflecting the temporal stability of the approach.

4.3. Quantitative Evaluation of Classification Accuracy

Quantitative analysis was conducted using manually labeled dynamic masks available for selected frames in the TUM dataset. The detection quality of the proposed EDC-based classifier was evaluated using precision (

P), recall (

R), and F1-score (

F), defined as

Table 1 summarizes the obtained results across the three dynamic sequences.

The proposed method achieves over 90% average precision, indicating a very low false-positive rate. The slightly lower recall values reflect conservative dynamic labeling, which is desirable for downstream pose estimation, as misclassifying dynamic points as static (false negatives) is more detrimental than removing a few valid ones. Compared to classical Sampson-distance-only filtering, which achieves approximately 82–84% F1-score on the same dataset, EDC yields a relative improvement of about 6–8%.

4.4. Impact on Visual SLAM Trajectory Estimation

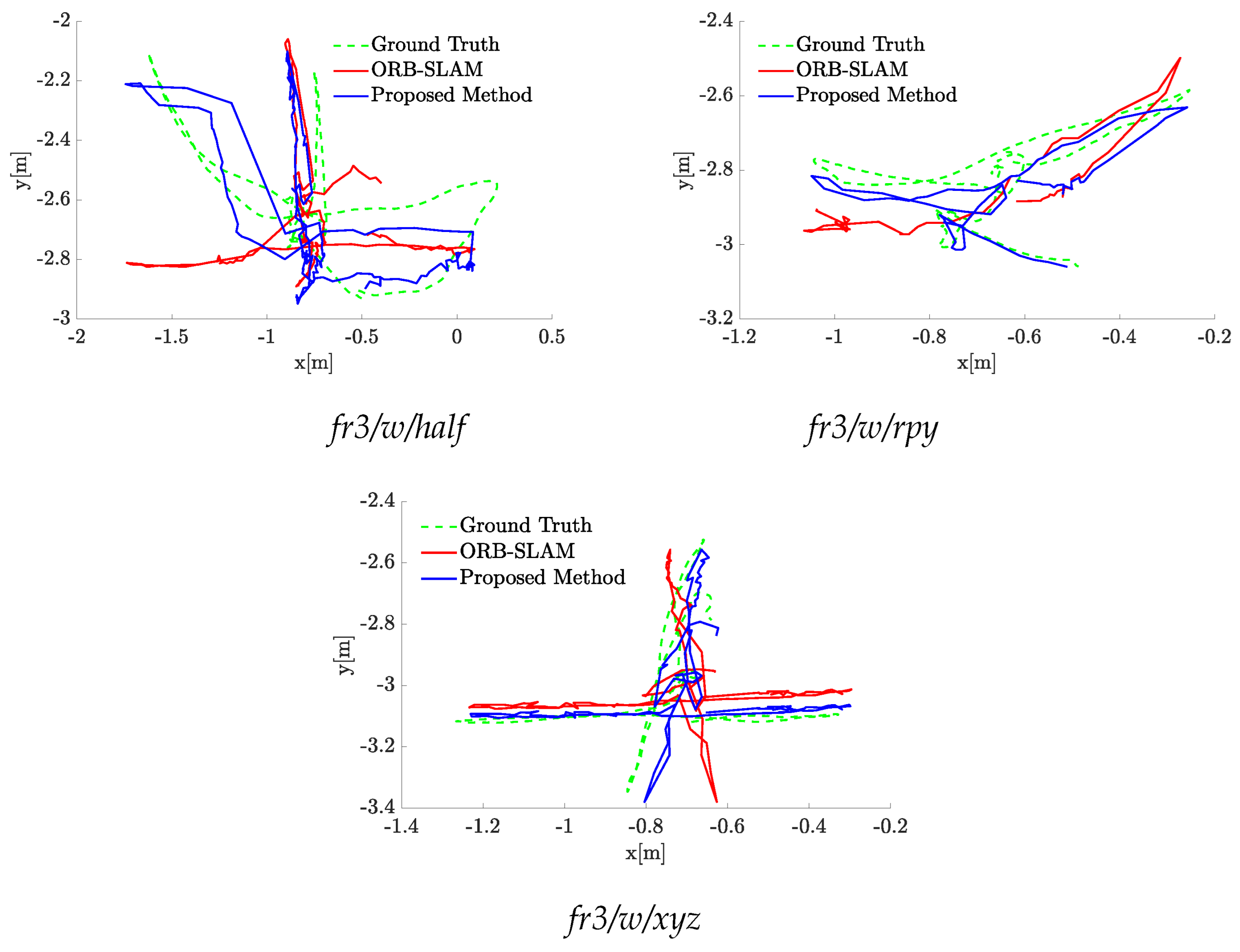

To assess the influence of dynamic-feature suppression on overall localization accuracy, we integrated the proposed EDC module into the ORB-SLAM framework, replacing the default geometric outlier rejection step. The camera trajectories estimated by standard ORB-SLAM and EDC-augmented ORB-SLAM were compared against the ground-truth trajectories provided by the TUM dataset.

Figure 3 presents representative trajectory comparisons. While the standard ORB-SLAM exhibits noticeable drift and local discontinuities in dynamic regions (e.g., when a pedestrian crosses the camera path), the EDC-ORB-SLAM trajectories remain closer to the ground truth, demonstrating improved temporal stability consistency.

Quantitatively, trajectory accuracy was evaluated using the Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) metric [

17]. Results are reported in

Table 2. Across all tested sequences, EDC integration leads to substantial improvements—reducing ATE by approximately 25–35% on average.

The observed accuracy gain highlights that dynamic-feature rejection not only improves frame-to-frame motion estimation but also stabilizes long-term map consistency. Particularly in the freiburg3_walking_rpy sequence, which contains strong rotational components, the EDC term mitigates the error propagation typically caused by transient outliers.

4.5. Ablation and Sensitivity Analysis

To better understand the contribution of each component, an ablation study was conducted on the

freiburg3_walking_xyz sequence. We tested (i) Sampson-only filtering, (ii) EDC-only filtering, and (iii) the combined hybrid model with and without temporal voting.

Table 3 summarizes the findings.

These results confirm that both positional and directional cues contribute complementary information. The hybrid variant consistently outperforms either individual metric, and the addition of temporal voting further improves robustness by mitigating frame-level noise.

Parameter sensitivity experiments show that performance remains stable for , with only minor degradation outside this range. This demonstrates the method’s adaptability across scenes with different motion magnitudes and noise levels.

4.6. Runtime Performance and Limitations

Runtime measurements indicate that the proposed EDC computation introduces minimal overhead, averaging approximately 15.8 ms per frame on CPU—equivalent to roughly 12–13 frames per second. Since the EDC evaluation is parallelizable across features, further speedups can be achieved on GPU or multicore implementations.

Although the method is robust across a wide range of conditions, several limitations remain. In cases of nearly pure rotation with negligible translation, the epipolar geometry becomes ill-conditioned, reducing the reliability of both Sampson and directional metrics. Similarly, points near the epipole may yield unstable angular measures due to numerical sensitivity. Finally, repetitive textures can lead to ambiguous flow orientations, occasionally resulting in over-rejection of valid correspondences. These limitations suggest potential for integrating semantic priors or uncertainty modeling as future work.

4.7. Discussion

Overall, the experiments demonstrate that the proposed Epipolar Direction Consistency (EDC) approach provides a principled, geometry-driven mechanism for motion outlier detection in dynamic scenes. It achieves strong quantitative and qualitative performance without requiring any training data or semantic annotations, maintaining computational efficiency suitable for real-time visual SLAM. The combination of positional and directional constraints improves both precision and trajectory stability, validating the hypothesis that angular epipolar alignment carries critical motion information beyond traditional residual-based metrics.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented a geometry-driven approach for detecting and rejecting dynamic feature correspondences in feature-based visual SLAM systems. The core idea is to augment classical epipolar-deviation tests with a novel Epipolar Direction Consistency (EDC) metric that measures the angular alignment between sparse optical-flow vectors and the epipolar-line tangent induced by the estimated two-view geometry. The EDC measure is combined with positional residuals (e.g., Sampson distance) within an adaptive scoring framework, and temporal voting and iterative refinement are used to improve robustness.

The experimental evaluation on dynamic sequences from the TUM RGB-D benchmark demonstrates that the proposed approach is effective in practice. When integrated into an ORB-SLAM-style pipeline, EDC-based filtering (i) substantially increases the reliability of feature correspondences used for pose estimation, (ii) reduces trajectory errors, and (iii) operates with modest computational overhead suitable for near real-time operation. Concretely, across the tested sequences the hybrid EDC+Sampson filtering improved Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) by roughly 25–35% relative to the unmodified ORB-SLAM baseline, while dynamic-feature detection achieved average precision and recall values on the order of 90% and 87%, respectively. The additional per-frame cost of the EDC scoring step is small (on the order of tens of milliseconds on a single CPU), and the computation is amenable to parallelization.

Beyond empirical gains, the method has several attractive properties. It is purely geometric and therefore does not require labeled training data or semantic models, which improves portability across environments. The directional cue encoded by EDC is complementary to positional epipolar residuals: angular alignment remains informative in scenarios where positional residuals are noisy (e.g., small baselines or repetitive textures), and vice versa. The use of adaptive thresholds based on the median absolute deviation (MAD) reduces the need for dataset-specific tuning and makes the approach more robust across a range of motion magnitudes.

At the same time, important limitations remain. The reliability of any epipolar-based test degrades when the epipolar geometry itself is ill-conditioned: examples include near-pure rotations (very small translation), viewpoints close to the epipole, or cases with too few high-quality correspondences for robust fundamental/essential matrix estimation. In such regimes the EDC angle may become unstable and, if used naïvely, can lead to over-rejection of valid matches or insufficient removal of dynamic outliers. Repetitive textures and gross matching errors also impair the estimation pipeline by contaminating the RANSAC inlier set. Finally, while the current study demonstrates the method in a monocular/feature-based setting, additional gains may be possible when colour-depth or stereo cues are available.

There are several natural directions for future work. First, integrating uncertainty modeling—propagating per-feature confidence (from descriptor matching, flow quality, and epipolar residual statistics) into a probabilistic filtering scheme—can reduce brittle decisions in low-information frames. Second, combining geometric EDC cues with lightweight semantic priors (e.g., class-agnostic motion segmentation or fast person detectors) would likely improve performance in highly cluttered scenes while controlling computational cost. Third, extending the approach to utilize depth (RGB-D) or stereo geometry directly (i.e., replacing or augmenting the two-view fundamental model) could further stabilize detection under small-baseline conditions. Fourth, implementing the EDC computation on parallel hardware and integrating it tightly into a full SLAM back-end (with local bundle adjustment using only static features) would allow evaluation of end-to-end latency and long-term mapping performance in real-time scenarios.

In summary, the Epipolar Direction Consistency principle offers a simple, interpretable and effective geometric cue for distinguishing static from independently moving features in visual SLAM. When combined with positional residuals and modest temporal smoothing, it materially improves pose estimation in dynamic scenes while retaining the efficiency and reproducibility required for practical deployment. We believe this work provides a useful building block for robust SLAM in the presence of dynamic objects and a strong foundation for subsequent hybrid geometric–semantic developments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. and F.A.; methodology, S.D.; software, S.D.; validation, F.A. and S.D.; formal analysis, S.D.; investigation, F.A.; resources, S.D.; data curation, S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.; writing—review and editing, S.D.; visualization, S.D.; supervision, F.A.; project administration, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SLAM |

Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| vSLAM |

Visual Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| ORB |

Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF |

| EDC |

Epipolar Direction Consistency |

| MAD |

Median Absolute Deviation |

| RANSAC |

Random Sample Consensus |

| RGB |

Red Green Blue |

| ATE |

Absolute Trajectory Error |

References

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Schöps, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-SLAM: Large-Scale Direct Monocular SLAM. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J.; Koltun, V.; Cremers, D. Direct Sparse Odometry. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (TPAMI) 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaramuzza, D.; Fraundorfer, F. Visual Odometry [Tutorial]. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2011, 18, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H. Stereo Visual Odometry Based on Feature Matching and Pose Optimization. Pattern Recognition Letters 2018, 105, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.; Liu, H.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, G. Robust Monocular Visual Odometry in Dynamic Environments. In Proceedings of the ICCV; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, H. Dynamic Object Detection for SLAM in Urban Environments. Sensors 2019, 19, 1478. [Google Scholar]

- Bescos, B.; Fácil, J.M.; Civera, J.; Neira, J. DynaSLAM: Tracking, Mapping, and Inpainting in Dynamic Scenes. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2018, 3, 4076–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Xie, F.; Yang, Y. DS-SLAM: A Semantic Visual SLAM Towards Dynamic Environments. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2018, 3, 4084–4091. [Google Scholar]

- Scona, R.; Jaimez, M.; Petillot, Y.; Fallon, M. StaticFusion: Background Reconstruction for Dense RGB-D SLAM in Dynamic Environments. In Proceedings of the ICRA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Liu, J. Detecting Moving Objects and Estimating Camera Motion from a Monocular Image Sequence. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 97080–97090. [Google Scholar]

- Casser, V.; Pizzoli, M.; Angelova, A. Unsupervised Learning for Depth and Ego-Motion Estimation from Monocular Video. In Proceedings of the CVPR Workshops; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Wang, S.; Long, Z.; Gu, D. Learning Monocular Visual Odometry via Self-Supervised Long-Term Modeling. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2020, 31, 5381–5395. [Google Scholar]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. SURF. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Barcelona, Spain, Nov 2011.

- Lucas, B.; Kanade, T. An Iterative Image Registration Technique with an Application to Stereo Vision. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI) or Imaging Understanding Workshop, 1981, pp.

- Hartley, R.I.; Zisserman, A. Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Sturm, J.; Engelhard, N.; Endres, F.; Burgard, W.; Cremers, D. A Benchmark for the Evaluation of RGB-D SLAM Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vilamoura, Algarve, Portugal, Oct 2012.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).