1. Introduction

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorder primarily affecting motor neurons, leading to progressive muscle weakness, atrophy and paralysis. Despite being a rare disease, ALS is the most prevalent form of motor neuron disease [

1,

2].

The global prevalence of ALS is estimated at 4.42 per 100,000 individuals (95% CI: 3.92–4.96), with an incidence of 1.59 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI: 1.39–1.81) [

3]. Higher prevalence and incidence rates have been reported in more socioeconomically developed regions [

4]. ALS typically presents with focal muscle weakness and atrophy, which spreads as the disease progresses [

2,

5]. It can be classified by onset site and by predominant motor neuron involvement (upper vs. lower motor neuron, UMN/LMN) [

6].

Diagnosis of ALS relies on clinical history, neurological examination, electrodiagnostic studies, and imaging to exclude other mimicking conditions [

7]. Early diagnosis remains a challenge due to symptom variability, the lack of definitive biomarkers, and ALS's heterogeneous early presentation, all of which contribute to frequent diagnostic delays and initial diagnostic errors[

7,

8]. Late or incorrect diagnosis significantly reduces the therapeutic window, limiting access to treatments and clinical trials, while also increasing the risk of inappropriate interventions [

9], with a negative impact on disease progression rate [

10].

Numerous scientific studies have explored and evaluated the factors contributing to the difficulty of diagnosing ALS in its early stages [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. First, the site of symptom onset can influence clinical suspicion, as spinal presentation may initially mimic other diseases, such as radiculopathies, spinal myelopathies, multifocal motor neuropathies, nerve entrapment, myasthenia gravis or primary muscle disorders. Age is another determinant; younger patients are more likely to experience a diagnostic error and have a longer diagnostic delay [

15]. Additionally, patients rapidly observed by a neurologist earlier have a faster diagnosis [

11,

13,

15]. A significant consequence of ALS difficult diagnosis is the occurrence of unnecessary surgical interventions [

16,

17].

This study we aim to identify ALS patients followed in our center who underwent surgical procedures due to misdiagnosis, to characterize their clinical profile and to review the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

Data prospectively collected at the ALS clinic, Centro Académico de Medicina de Lisboa, ULS de Santa Maria, between 2021 and 2024, were analysed. A standardized clinical questionnaire [

18] was completed during the initial evaluation by an experienced neurologist (MdC, MOS).

Inclusion Criteria included a confirmed ALS diagnosis based on Gold Coast Criteria, disease progression on follow-up, completion of data questionnaire and informed consent. Exclusion criteria included associated dementia (due to limitations in providing essential clinical information regarding the diagnostic track), other neurological conditions, severe comorbidities, and missing key data. An exception was made for 23 patients (7.6%) who were uncertain about the presence of fasciculations at the time of first motor symptoms.

2.2. Subgroup Classification

Patients were classified into two groups: Surgery Group - patients who underwent surgical procedures; non-Surgery Group - patients who did not undergo surgery related to ALS symptoms. Information was confirmed through clinical review, diagnostic tests, and surgical records.

2.3. Variables Analysis

We compared demographic and clinical variables between the Surgery and non-Surgery groups. Demographic variables included age at symptom onset and sex. Clinical variables included diagnostic delay (months from symptom onset to ALS diagnosis), disease progression rate, region of onset (spinal vs. non-spinal), presence of fasciculations at onset, and UMN/LMN predominance.

UMN predominance was defined by spasticity with functional impairment, and LMN predominance by weakness and atrophy without spasticity. In mixed cases, LMN predominance was assumed, based on prior literature indicating a higher likelihood of diagnostic uncertainty [

10,

16].

The functional rate of progression (ΔFS) at first visit at our ALS clinic was calculated using the Revised ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS-R) as follows:

ΔFS = (48 – ALSFRS-R at first visit) / duration in months from symptom onset to first visit [

19]. Patients were classified as Slow Progressors (ΔFS < 0.29), Intermediate Progressors (0.29 and 1.03), or Fast Progressors (ΔFS > 1.03), following the thresholds defined in Alves et al., 2025 [

19].

To assess the influence of healthcare pathways on the diagnostic trajectory of ALS, we analysed the first specialist seen for related-ALS symptoms (neurologist, neurosurgeon, general practitioner, orthopaedic surgeon, or other). In the Surgery Group, we also documented the type of surgical procedure and the specialty of the operating physician.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were analysed using independent t-tests (if normally distributed) or the Mann-Whitney U test (if non-normally distributed, assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test). Categorical variables were analysed using the Chi-square test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 30.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

2.5. Ethical Compliance Statement

This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (Comissão de Ética do Centro Académico de Medicina de Lisboa, ID number 162/21) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave informed consent. To ensure data privacy, all patient information was anonymized, and databases were stored securely.

3. Results

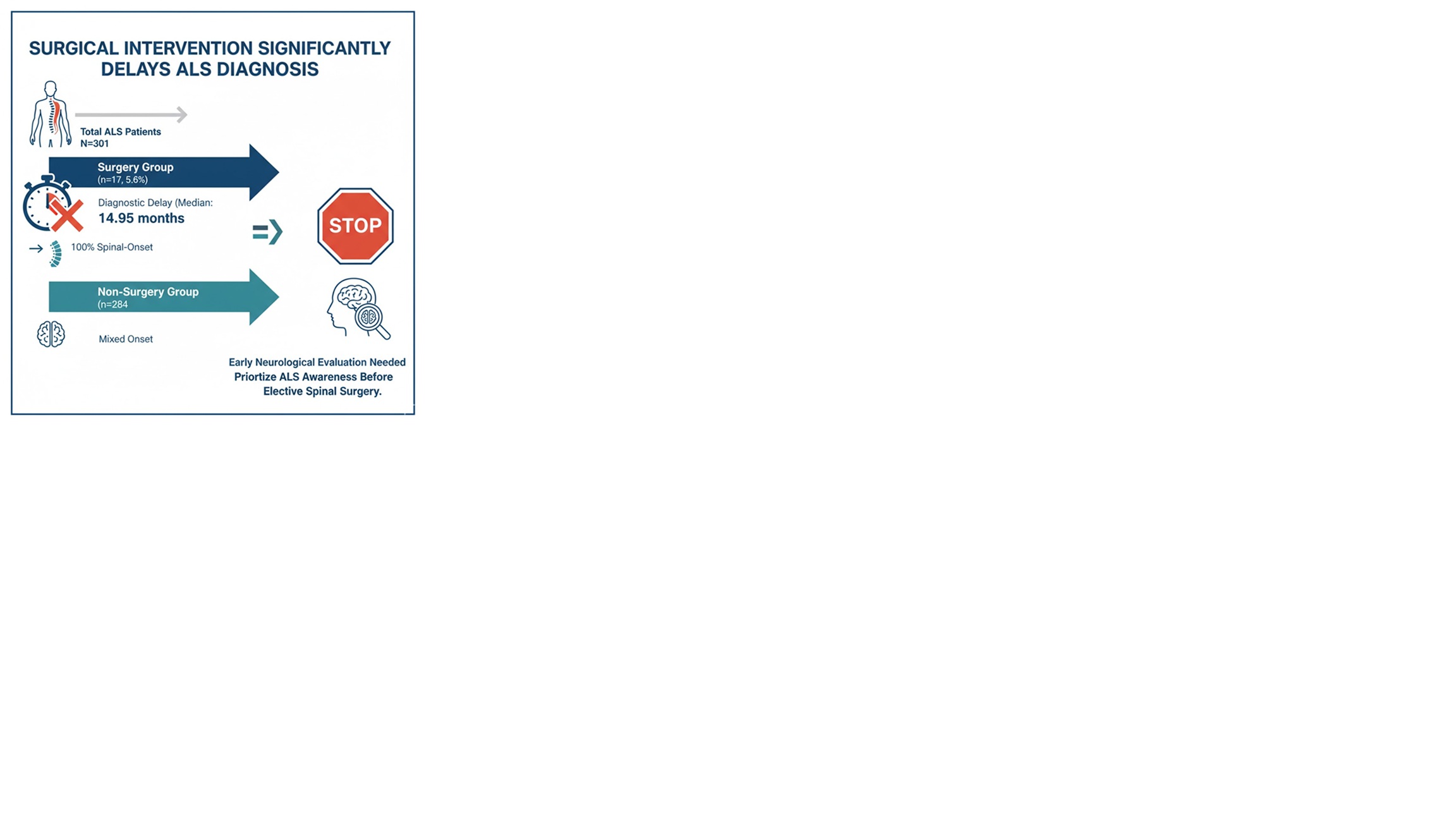

The statistical analysis included 301 ALS patients, of whom 17 (5.6%) underwent surgical procedures. The demographic and clinical characteristics of both groups are shown in

Table 1, no significant differences were found between the Surgery and non-Surgery groups in terms of sex (

p=0.35) or age at onset (p=0.77).

Diagnostic delay was significantly longer in the Surgery Group (14.95 [10.97 – 20.02] months vs. 8.99 [5.95 – 15.99] months, p=0.01) as seen in

Figure 1. Regarding disease onset, there was a significant association with spinal-onset (p=0.014). All patients in the Surgery Group had spinal onset ALS, whereas 26.8% of the non-Surgery Group had a non-spinal onset. No significant differences were found in UMN vs. LMN predominance (p=0.71) and for ΔFS at diagnosis (p=0.453). No significant differences were found in UMN vs. LMN predominance (p=0.708). Symptoms of fasciculations at disease onset were assessed in 278 patients, no difference was found between groups (p=0.13).

Among the 17 ALS patients (5.6%) who underwent surgery, the initial specialist varied. General practitioners (GPs) were most frequently seen first (24%), followed by orthopaedic surgeons (18%), neurologists (12%), and neurosurgeons (12%). In 6 cases (35%), the first consulted specialist could not be identified. Common diagnoses included lumbar stenosis (53.0%, n=9), cervical myelopathy (24.0%, n=4) and carpal tunnel syndrome (18.0%, n=3). These led to surgical interventions such as spinal decompression (77.0%, n=13), carpal tunnel release (18.0%, n=3), and other orthopaedic procedures (6.0%, n=1). Most surgeries (64.7%) were performed by neurosurgeons, while the remainder (35%) were conducted by orthopaedic surgeons.

Comparing with Prior Studies

Our literature review retrieved two articles from the electronic search that investigated inappropriate surgeries in ALS [16, 17]. One study reported that 7.9% of ALS patients underwent inappropriate surgical interventions [

16]. Srinivasan et al, observed 13% of ALS patients underwent unnecessary procedures [

17]. Our findings are consistent with these studies, confirming that patients spinal-onset ALS are often diagnosed as cervical or lumbar compressive disorders. In all three studies, spinal decompression surgeries and carpal tunnel releases were common procedures performed before an ALS diagnosis was established, as presented in

Table 2. The total number of surgeries exceeded the number of patients, as some individuals underwent multiple procedures as in [

17]; in our study, three patients underwent two surgeries related to ALS symptoms. Similar to prior findings, most patients who underwent surgery were initially evaluated by non-neurologists, particularly surgeons.

4. Discussion

Among the 301 ALS patients included in the study, 17 (5.6%) underwent surgery for symptoms that were later attributed to ALS. These patients who underwent surgery experienced a significantly longer diagnostic delay (p=0.010), and all of them had spinal-onset ALS. However, no significant differences were found for ΔFS, UMN versus LMN predominance, or the presence of fasciculations at onset. Fasciculations at onset and UMN versus LMN predominance were not approached in previous studies.

Our overall findings align with previous studies, reinforcing the persistent challenge in the early recognition of ALS—often resulting in substantial diagnostic delays and mismanagement, including unnecessary surgical procedures [10, 11, 17, 20]. Patients in the Surgery Group had a significantly longer diagnostic delay (median: 14.95 months) compared to the non-Surgery Group, likely due to the initial difficulty in diagnosis, as previously proposed [

10]. Contrary to a previous study [

10], we found no evidence of faster disease progression after the surgical intervention; however, the follow-up information in our study was limited due to missing data.

All patients in the Surgery Group had spinal-onset ALS, which shows spinal-onset is more prone to surgical interventions due to misdiagnosis [

10,

16,

17]. In this cohort, predominant UMN signs did not prevent inappropriate surgeries. Contrary to expectation, spasticity and hyperreflexia did not prompt earlier referrals to neurology, possibly due to incidental cervical cord MRI findings. Interestingly, while fasciculations associated with weakness are a hallmark of ALS and strongly suggest the disease [

21], this clinical feature was not relevant in our study, suggesting that future diagnostic red flags should strongly emphasize this finding.

The first specialist consulted significantly influences the ALS diagnostic pathway. Within our Surgery group cohort, 24% of patients initially consulted general practitioners, and 29% consulted surgical specialties (orthopaedics and neurosurgery). The small sample size of the Surgery Group made a comparative analysis of diagnostic pathways infeasible.

This study has several limitations: firstly, the initial specialist consulted was unidentified in 35% of surgical cases; secondly, the single-centre design may restrict the generalizability of findings to healthcare systems with differing referral patterns (22-23); and the limited sample size of operated patients reduces the statistical power, potentially affecting the robustness of the results.

5. Conclusions

Beyond the clinical implications, inappropriate surgical interventions in ALS patients impose avoidable healthcare costs and psychological distress on patients and families. In our cohort, we found some issues linked to diagnostic delay, including late neurology referrals and potential overreliance on imaging. Improving interdisciplinary referral protocols and integrating neuromuscular triage tools at the primary care level could mitigate these diagnostic issues. Future research should focus on developing diagnostic red flags for early ALS, particularly in patients with non-specific spinal symptoms, as the split-hand phenomenon [

24].

Author Contributions

M Martins: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft; M Gromicho: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; M Oliveira Santos: Data Colection, Writing – review & editing; M de Carvalho: Conceptualization, Data Colection, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be shared by the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

References

- Masrori, P.; Van Damme, P. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a clinical review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeyer, S.; Murn, M.; Choi, P.J. Respiratory failure in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Chest 2019, 155, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ji, H.; Hu, N. Cardiovascular comorbidities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 96, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, E.L.; Goutman, S.A.; Petri, S.; Mazzini, L.; Savelieff, M.G.; Shaw, P.J.; Sobue, G. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2022, 400, 1363–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gromicho, M.; Figueiral, M.; Uysal, H.; Grosskreutz, J.; Magdalena Kuzma-Kozakiewicz, M.; Pinto, S.; Petri, S.; Madeira, S.; Swash, M.; de Carvalho, M. Spreading in ALS: The relative impact of upper and lower motor neuron involvement. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couratier, P.; Lautrette, G.; Luna, J.A.; Corcia, P. Phenotypic variability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 177, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.; Swash, M. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of MND/ALS: IFCN handbook chapter. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 2024, 7, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Es, M.A.; Hardiman, O.; Chio, A.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Veldink, J.H.; Van den Berg, L. ;. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2084–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.; Buerger, M.; Berlit, P. Diagnostic problems and delay of diagnosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2010, 112, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Swash, M.; De Carvalho, M. Does surgery accelerate progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2014, 85, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.; Morren, J.A.; Pioro, E.P. Time to diagnosis and factors affecting diagnostic delay in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 417, 117054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellura, E.; Spataro, R.; Taiello, A.C. ; La Bella, V Factors affecting the diagnostic delay in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2012, 114, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwathmey, K.G.; Corcia, P.; McDermott, C.J.; Genge, A.; Sennfält, S.; de Carvalho, M.; Ingre, C. Diagnostic delay in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 2595–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzwalo, H.; De Abreu, D.; Swash, M.; et al. Delayed diagnosis in ALS: The problem continues. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 343, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcão de Campos, C.; Gromicho, M.; Uysal, H.; Grosskreutz, J.; Kuzma-Kozakiewicz, M.; Oliveira Santos, M.; Pinto, S.; Petri, S.; Swash, M.; de Carvalho, M. Delayed Diagnosis and Diagnostic Pathway of ALS Patients in Portugal: Where Can We Improve? Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 761355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakola, E.; Konotis, P.; Zambelis, T.; Karandreas, N. Inappropriate surgeries in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A still considerable issue. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2014, 15, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, J.; Scala, S.; Jones, H.R.; saleh, F.; Russell, J. J Inappropriate surgeries resulting from misdiagnosis of early amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2006, 34, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.; Ryczkowski, A.; Andersen, P.; Gromicho, M.; Grosskreutz, J.; Kuźma-Kozakiewicz, M. ; Petri, S; Piotrkiewicz, M; Miltenberger Miltenyi, G International Survey of ALS Experts about Critical Questions for Assessing Patients with ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2017, 18, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, I.; Gromicho, M.; Oliveira Santos, M.; Pinto, S.; de Carvalho, M. Assessing disease progression in ALS: prognostic subgroups and outliers. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2025, 26, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganoni, S.; Macklin, E.A.; Lee, A.; Murphy, A.; Chang, J.; Zipf, A.; Cudkowicz, M.; Atasi, N. Diagnostic timelines and delays in diagnosing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener 2014, 15, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.; Kiernan, M.C.; Swash, M. Fasciculation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: origin and pathophysiological relevance. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2017, 88, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludolph, A.C.; Knirsch, U. Problems and pitfalls in the diagnosis of ALS. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999, 165, S14-520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcão de Campos, C.; Gromicho, M.; Uysal, H.; Grosskreutz, J.; Kuzma-Kozakiewicz, M.; Oliveira Santos, M.; Pinto, S.; Petri, S.; Swash, M.; de Carvalho, M. Trends in the diagnostic delay and pathway for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients across different countries. Front. Neurol. 2023, 13, 1064619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcia, P.; Bede, P.; Pradat, P.F.; Couratier, P.; Vucic, S.; De Carvalho, M. Split-hand and split-limb phenomena in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: pathophysiology, electrophysiology and clinical manifestations. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).