1. Introduction

Insulin secretion from pancreatic islet beta cells occurs in a pulsatile manner, with a typical periodicity of approximately five minutes [

1]. The mechanistic basis of this oscillatory behavior has been investigated for several decades, with a variety of models proposed to explain it. These models range from qualitative to mathematical, differing in their core mechanisms of rhythmogenesis and regulatory details. A common feature across most canonical models is the central role of ATP production and the ATP-dependent closure of ATP-sensitive potassium (K

ATP) channels—a concept well-established and significantly refined over recent years.

One of the most comprehensive frameworks, the Dual Oscillator Model (DOM), was developed to account for the complex interplay between metabolic and electrical activity in beta cells. The DOM integrates a glycolytic oscillator, driven by feedback of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) on phosphofructokinase (PFK), with an electrical oscillator, based on calcium-dependent ion channel dynamics [

2]. This model successfully reproduces the range of bursting behaviors observed in experiments, including fast, slow, and compound oscillations. A major advancement came from experimental findings showing that glycolytic intermediates, particularly FBP, oscillate in antiphase with the well-documented Ca²⁺ oscillations [

3]. This discovery led to the development of a modified DOM model [

4], which attributes slow islet oscillations to the interplay between glycolytic dynamics and Ca²⁺ feedback. In this model, Ca²⁺ regulates pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and stimulates ATP hydrolysis; together, these interactions modulate ATP production and consequently influence the cell’s electrical activity.

Building on this foundation, the Integrated Oscillator Model (IOM) was introduced by Bertram et al. (2018) [

5], incorporating feedback regulation of glycolytic flux by cytosolic Ca²⁺ via PDH activity. In this framework, low Ca²⁺ levels reduce glycolytic efflux, leading to FBP accumulation, whereas high Ca²⁺ levels enhance efflux, resulting in FBP depletion. These dynamics closely match experimentally observed FBP oscillations [

3], reinforcing the view that glycolysis and calcium signaling are tightly coupled in beta cell oscillations.

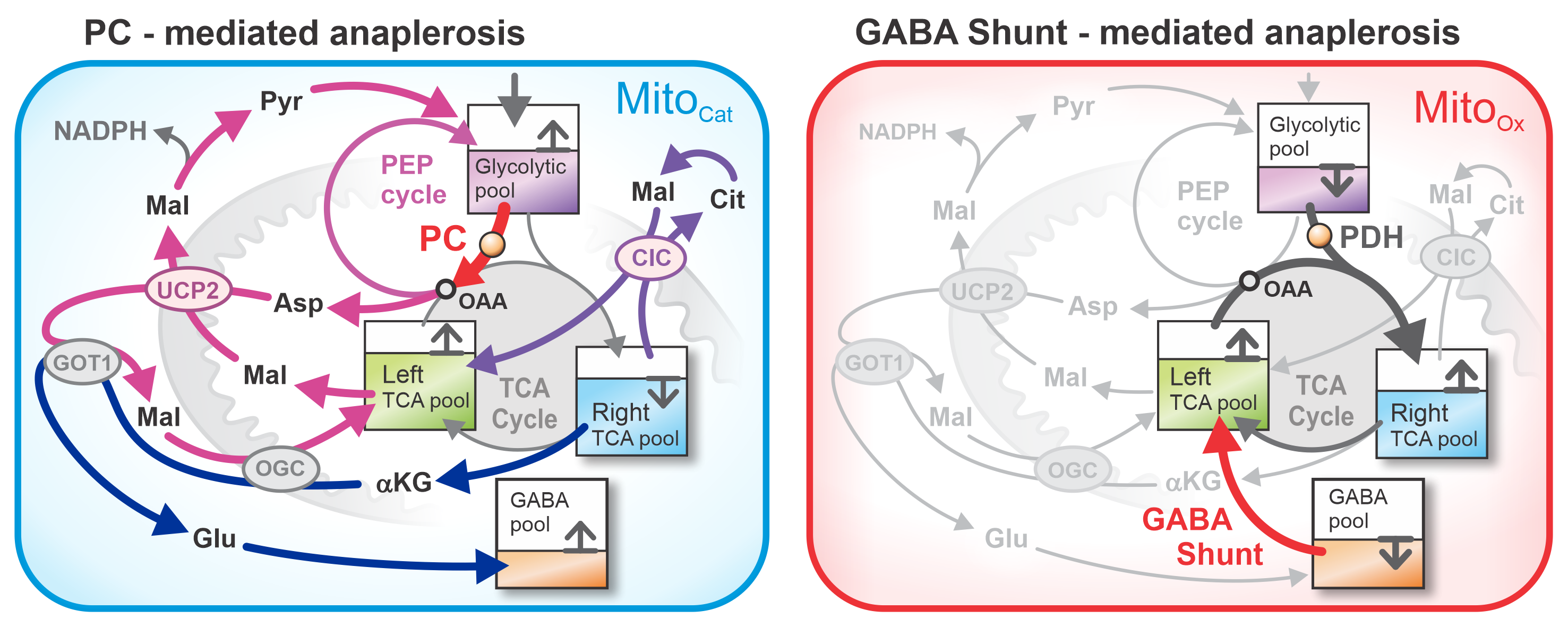

A significant shift in beta cell modeling occurred with the recognition that anaplerotic and cataplerotic fluxes, in conjunction with oxidative metabolism, play essential roles in shaping the oscillatory behavior of glucose-stimulated beta cells and their pulsatile insulin secretion. By incorporating not only the temporal but also newly appreciated spatial aspects of beta cell metabolism, the MitoCat–MitoOx model was introduced [

6]. This model integrates the roles of anaplerosis, pyruvate kinase (PK) activity, and the mitochondrial phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) cycle into a comprehensive framework of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). It proposes that during the MitoCat phase, PK elevates ATP/ADP ratios in the plasma membrane microdomain, leading to closure of K

ATP channels and membrane depolarization. In contrast, during the MitoOx phase, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) is activated in response to rising ADP levels, generating ATP to meet the energetic demands of insulin exocytosis and ion transport. Viewed more broadly, the MitoCat–MitoOx model acknowledges that multiple interconnected metabolic and ionic processes exhibit phase-specific acceleration and deceleration—coinciding with either the electrically silent triggering phase (MitoCat) or the electrically active secretory phase (MitoOx) of insulin oscillations.

Building on these advances, we have recently developed a comprehensive computational model that integrates anaplerotic metabolism, localized ATP production, and redox signaling to simulate beta cell responses to both glucose and glucose-glutamine stimulation Grubelnik et al. (2024) [

7]. This model extends beyond the conventional emphasis on OxPhos and K

ATP channel activity by highlighting localized ATP generation from PEP in close proximity to K

ATP channels. It also emphasized the signaling role of H₂O₂ during the first phase of insulin secretion and underscored the importance of anaplerotic metabolism in the second phase—particularly the production of NADPH and glutamate (Glu) as key amplifiers of insulin release. In a follow-up study [

8], further emphasis was placed on distinguishing between distinct ATP pools and separately analyzing the first triggering phase and the second amplifying phase of beta cell activation.

Expending on this work, we present a new conceptual framework: the Dual Anaplerotic Model (DAM). Central to this model is the understanding that two major anaplerotic pathways contribute to refilling the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates. The first is the well-established glucose-induced anaplerosis via pyruvate carboxylase (PC), while the second involves the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) shunt—an often-overlooked route that recent evidence suggests plays a crucial anaplerotic role [

9]. Following the terminology of earlier models [

6,

7,

8], we distinguish between two alternating mitochondrial metabolic states: the oxidative (MitoOx) and cataplerotic (MitoCat) phases.

In the MitoOx phase, a Ca²⁺ pulse initiates oxidative metabolism by activating PDH, which drives downstream production of NADH and FADH₂. Shortly thereafter, GABA-derived succinate enters the TCA cycle, providing additional carbon that increases flux through the cycle, acting as a

metabolic highway to amplify the rate of ATP production [

10,

11]. As Ca²⁺ is subsequently sequestered, the system transitions into the MitoCat phase, enabling net carbon efflux and cytosolic conversion of exported intermediates—including αKG to GABA—thereby restoring the GABA pool. Importantly, this replenishment of the GABA pool, linked to αKG cataplerosis during the MitoCat phase, is critically supported by simultaneous PC-derived anaplerotic flux. Together, these pathways function as interdependent and temporally coordinated PC- and GABA shunt–driven anaplerotic routes.

In what follows, we first present the model conceptually, describing its qualitative operation. The system is represented by four core metabolic pools, and we outline the key processes that govern the fluxes between them. The mathematical formulation of these fluxes is deliberately kept as simple as possible to construct a minimal model of the dynamics occurring in glucose-stimulated beta cells. The purpose of this model is to highlight the temporal transitions and distinct activation phases—specifically, the cyclic emptying and refilling of individual pools—and to illustrate how their interplay constitutes an efficient and responsive regulatory mechanism. To complement the mathematical model, we also provide an animation that visually demonstrates the oscillatory behavior of the principal metabolic pools. Finally, we discuss how our model predictions align with available experimental observations and outline how this minimal framework may serve as a foundation for future extensions toward more comprehensive and physiologically realistic models of glucose-stimulated beta cell function.

2. Model

In this model, beta cell metabolism is conceptualized as a synergistic interplay among glycolysis, the TCA cycle, the PEP cycle, and the GABA shunt. To reduce biochemical complexity while retaining essential functional relationships, the system is represented using a four-pool framework.

The first pool, P₀, comprises downstream glycolytic intermediates, primarily FBP and PEP. These metabolites are direct precursors of pyruvate (Pyr), which serves as the principal source of carbon entering mitochondrial metabolism.

The second pool, P₁, corresponds to the right half of the TCA cycle and includes citrate (Cit), isocitrate (Isocit), and α-ketoglutarate (αKG). This pool effectively represents the primary site of carbon entry into the TCA cycle via the condensation of acetyl-CoA with oxaloacetate (OAA).

The third pool, P₂, represents the left half of the TCA cycle, comprising primarily C₄ dicarboxylates such as malate (Mal) and fumarate (Fum). Mal, in particular, plays a dominant role in redox balance and metabolite transport, while other intermediates are assumed to be in near-equilibrium with it.

The fourth pool, P₃, captures the GABA reservoir, which is tightly linked to TCA cycle metabolism through the GABA shunt. This pathway provides an alternative anaplerotic input into the TCA cycle via succinate production, especially under conditions that favor increased GABA flux, such as elevated glucose availability or glutamine co-stimulation.

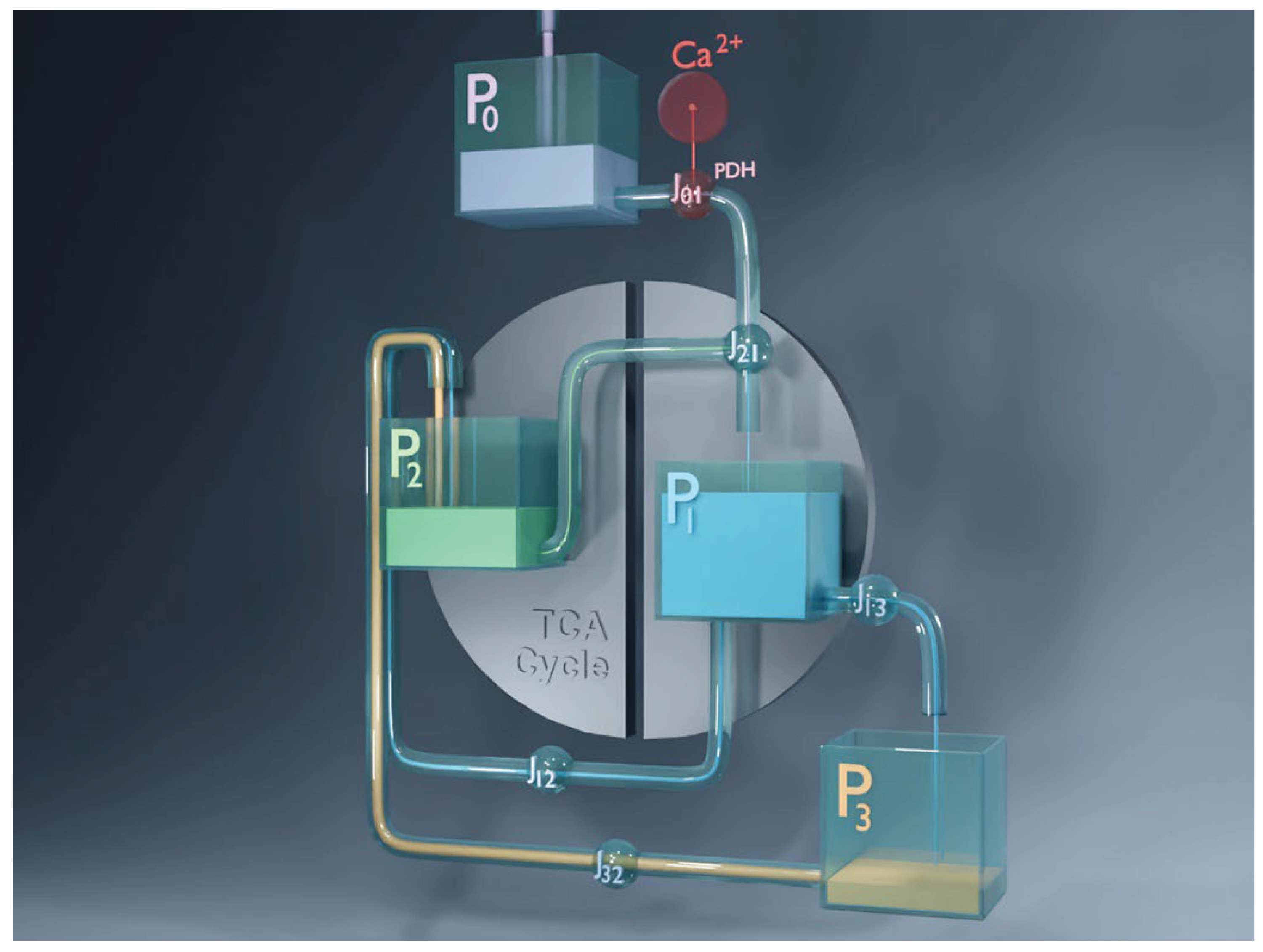

The main fluxes between pools P₀–P₃ are schematically illustrated in

Figure 1. A central flux connects P₀ to P₁ via PDH, representing the Ca²⁺-sensitive entry of Pyr into the TCA cycle through acetyl-CoA. Elevated Ca²⁺ enhances PDH activity, thereby facilitating carbon flow from P₀ to P₁ and simultaneously from P₂ to P₁, as one OAA combines with one acetyl-CoA to form Cit in P₁. This reaction enables oxidative metabolism, defining the MitoOx phase [

12,

13].

The GABA pool (P₃) contributes to the TCA cycle through the GABA shunt, an anaplerotic pathway that generates succinate and feeds it into P₂. This flux from P₃ to P₂ provides a source of »

fresh carbon« to the cycle and plays a crucial role in enhancing the MitoOx phase [

9].

A second, well-established anaplerotic flux—also indicated in red in

Figure 1—is the glucose-derived entry via PC, which channels Pyr into the PEP cycle and contributes to OAA replenishment. This OAA is further required for aspartate (Asp) extrusion, a process that interacts with GABA metabolism, together forming tightly interdependent and temporally coordinated PC- and GABA shunt–driven routes (see inset of

Figure 1).

Because both GABA-mediated and PC-mediated fluxes are anaplerotic, they must be balanced by cataplerotic fluxes to maintain a zero net carbon flux and allow metabolite concentrations to oscillate around quasi-stationary values. Cataplerotic fluxes, however, are complex: metabolites such as Mal, Cit, and αKG often exchange between compartments without causing true net carbon loss [

6]. Genuine efflux occurs only through regulated transport processes—most notably UCP2-mediated extrusion of C₄ metabolites (experimentally demonstrated by Vozza et al., 2014)—which are tightly controlled by GTP and its co-regulation with quinol (Q

red), as reviewed by [

14]. These cataplerotic fluxes were analyzed in detail in Grubelnik et al. (2024) [

7].

In the present framework, the principal net cataplerotic flux is represented in the inset of

Figure 1, illustrating redistribution of carbon from P₁ into P₃ via cytosolic Glu production and conversion to GABA. Notably, this replenishment of the GABA pool (P₃), linked to αKG cataplerosis, is critically supported by simultaneous PC-derived anaplerotic flux—via UCP2-extruded Asp and Mal, and via malic enzyme (ME1) conversion of Mal back to Pyr. Together, the PC- and GABA shunt–driven anaplerotic routes function as interdependent and temporally coordinated processes. This synergistic interaction completes the cycle by replenishing P₃. In parallel, redistribution of Cit from P₁ into Mal in P₂ via the Cit–Mal exchanger (CIC) is also shown in

Figure 1.

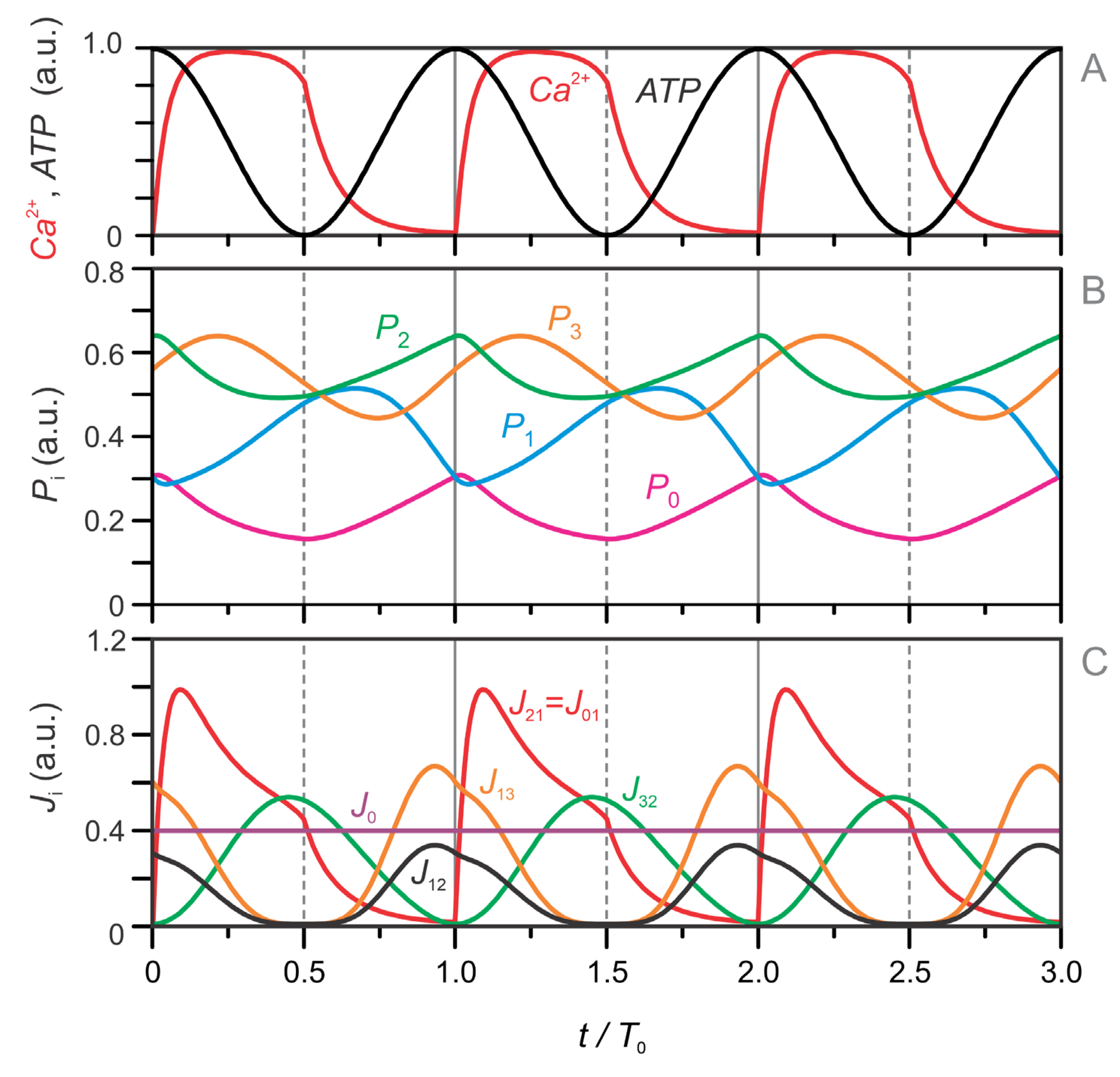

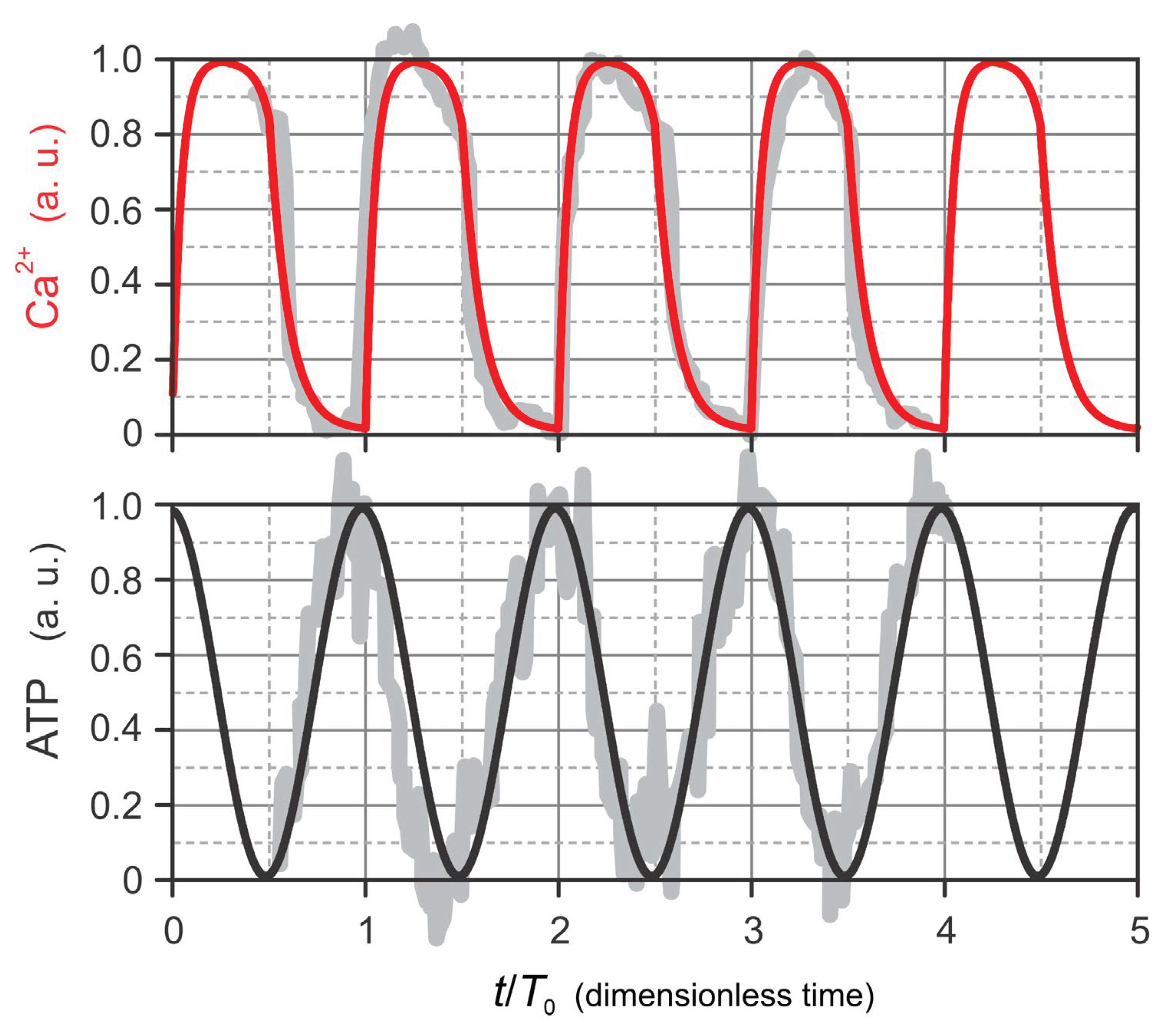

The model dynamics is based on the experimentally measured Ca

2+ and ATP traces. Several studies [

15,

16,

17,

18] have shown that in beta cells the temporal oscillations of ATP and Ca²⁺ are in opposite phase. When Ca²⁺ concentration is at its lowest, ATP concentration is at its highest, while ATP reaches its minimum shortly before the Ca²⁺ peak [

16]. We take experimental measurements from Gregg et al. (2019) [

17] as the basis for modeling Ca²⁺ and ATP dynamics, and obtain the following equations:

In these equations, the concentrations of Ca²⁺ and ATP, time t, and all parameters are expressed in dimensionless units. The constants are defined as follows , , , , , , , and .

As a result, the model generates oscillatory dynamics of

Ca²⁺ and

ATP that vary between 0 and 1, closely resembling the temporal profiles observed in the experimental data. The original measurements from Gregg et al. (2019) [

17], along with the fitted curves based on Eqs. 1 and 2, are shown in

Figure 2.

As presented in

Figure 1, we consider the system as a four-pool model, for simplicity grouping together the key metabolites into the glycolytic compartment, the “left” part of the TCA cycle, the “right” part of the TCA cycle, and the GABA pool. Mathematically, we assume that the concentrations of the metabolites within each pool oscillate simultaneously; although their absolute values differ, their temporal dynamics are considered to be in phase. In the mathematical formulation, we define the four pools as follows:

To mathematically describe the dynamic behavior of metabolite pools involved in GSIS, we developed a minimal model based on four interacting metabolic pools. These pools represent key components of beta cell metabolism: glycolysis (), the right-hand segment of the TCA cycle (), the left-hand segment of the TCA cycle (), and the GABA shunt (). Each pool comprises a representative group of metabolites that are assumed to oscillate with broadly similar temporal dynamics, while the fluxes between them are governed by biologically motivated, nonlinear expressions.

Rather than aiming for biochemical detail, the model prioritizes simplicity without sacrificing physiological relevance. We use multiplicative power-law expressions for fluxes, where each flux depends on the concentrations of key regulators—typically in the form of products of variables raised to fixed exponents. This structure captures fundamental features of metabolic control, including Ca2+ activation, NADH-mediated feedback inhibition, and ATP-dependent regulation, while ensuring that the model remains analytically and computationally manageable.

Although both ATP and NADH reflect the cellular energy state and act as activators/inhibitors in multiple pathways, we simplify the model by assuming rapid interconversion between them via the electron transport chain. As a result, we treat NADH and ATP as directly proportional. This simplification is expressed as:

Simultaneous measurements in beta cells using Perceval-HR (ATP/ADP ratio) and flavin autofluorescence (reflecting NADH) show that the two oscillate in phase, indicating tight metabolic coupling [

3]. However, in a majority of cases, a second flavin-1 peak, not mirrored in ATP, has been observed. This second peak can be explained either by Ca²⁺-dependent stimulation of TCA-cycle dehydrogenases, transiently increasing NADH and FADH₂ production during the active phase [

3], or by two distinct peaks of NADH and NADPH [

8].

The resulting system of model equations offers a mechanistic yet minimal framework for simulating the oscillatory metabolic dynamics that underpin insulin secretion. In the sections below, we define the dynamics of each pool and the fluxes that interconnect them.

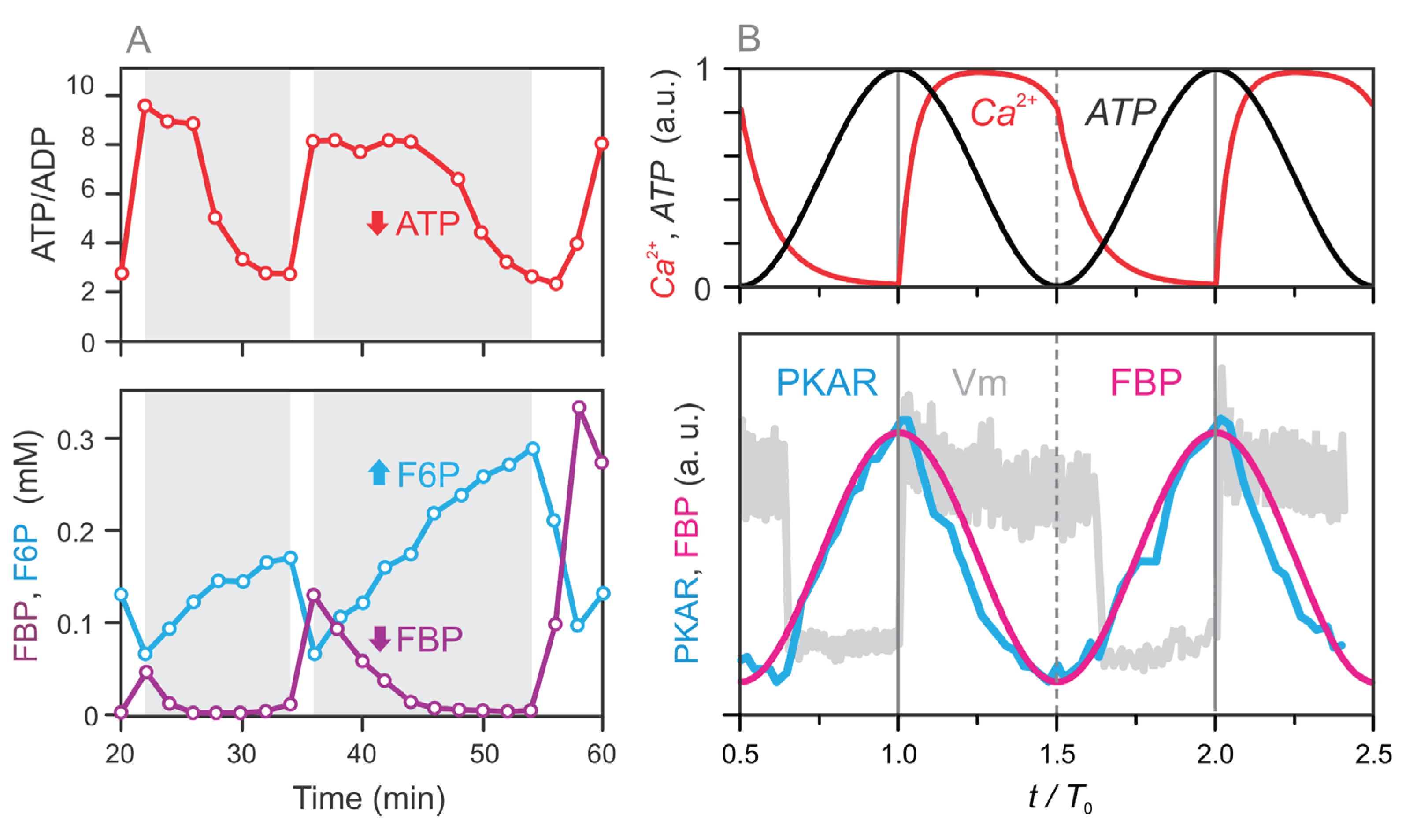

The dynamics of the glycolytic pool (

) is modeled based on experimental data for FBP reported by Tornheim (1997) [

19]. As shown in

Figure 3A, we extracted these data and annotated regions (white and gray shaded) to indicate phases during which FBP and ATP exhibit synchronous behavior. Specifically, both FBP and ATP increase during the white regions and decrease during the gray regions, demonstrating that their oscillations are in phase.

Although the waveform profiles of FBP and ATP are not identical, more recent studies—specifically in pancreatic beta cells [

3]—have shown that FBP oscillations adopt a smoother, more sinusoidal-like profile that closely resembles ATP dynamics. Based on these findings, we approximate the FBP dynamics using a sinusoidal function fitted to the experimental data.

Figure 3B compares the extracted data from Merrins et al. (2016) [

3] with the sinusoidal function used in our model, showing good agreement.

Accordingly, the FBP-related glycolytic pool (

) is modeled as:

where

,

.

The glycolytic pool (

) is tightly coupled to the TCA cycle through the generation of Pyr from the intermediates FBP and PEP. One major route for Pyr to enter the TCA cycle is via the oxidative pathway through PDH, which converts Pyr into acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA subsequently combines with OAA, derived from Mal (

), to form Cit in the first TCA pool (

). The flux through PDH, denoted

, is regulated by several factors: the concentration of glycolytic intermediates (

) that give rise to Pyr [

4,

20], the availability of OAA as reflected by Mal levels in

[

20], and intracellular Ca²⁺, which stimulates PDH activity [

12,

13]. Although PDH is also inhibited by NADH—in other words, activated by the term (

) in our model—Ca²⁺ and (

) (which is related to

) oscillate in phase (see

Figure 2). This means that both signals would modulate

in the same direction. To reduce redundancy while preserving physiologically relevant regulation, we simplify the model by including only Ca²⁺ as the modulating factor. This results in a reduced yet biologically meaningful representation of PDH regulation. The resulting flux

is defined as:

with

.

Given that Cit synthase consumes one molecule of acetyl-CoA and one molecule of OAA to generate Cit, and assuming a steady-state concentration of acetyl-CoA, the flux through Cit synthase (

) must equal the flux of acetyl-CoA production via PDH (

). This reflects the 1:1 stoichiometry of the reaction and allows us to equate these two fluxes:

Accordingly, the dynamics of pool

—representing intermediates in the “right-hand” side of the TCA cycle—is governed by:

The flux

represents the carbon transfer from the “right” to the “left” side of the TCA cycle. This includes both the canonical clockwise flux through succinyl-CoA and succinate, as well as the cataplerotic–anaplerotic route via Cit–Mal exchange. The latter becomes particularly active under high-energy, nutrient-rich conditions, when excess Cit is exported from mitochondria to the cytosol via the Cit/Isocit carrier (CIC) (see inset of

Figure 1). Since the canonical oxidative pathway results in complete carbon loss as CO₂ and does not contribute to net carbon redistribution between pools, it is excluded from the model. Accordingly,

is defined solely through the Cit–Mal exchange and is expressed as:

Here,

reflects the dependence on metabolite levels in the right-hand segment of the TCA cycle. The parameter value is set to

. The

term emphasizes that flux

is primarily regulated by the concentration of NADH. Elevated NADH levels inhibit the clockwise TCA flux by suppressing the activity of Isocit dehydrogenase (IDH) and αKG dehydrogenase (αKGDH) [

21,

22,

23,

24]. This inhibition results in Cit accumulation and its export from mitochondria to the cytosol, where it is cleaved into acetyl-CoA and OAA. The latter is then reduced by MDH, using NADH, to form Mal, which is subsequently transported back into the mitochondrial matrix (see the inset of

Figure 1). Together, these processes highlight the strong dependence of flux

on NADH concentration.

Flux

represents the production of GABA from αKG via the Mal–Asp shuttle and the C4 efflux through UCP2 channels, as illustrated in greater detail in the inset of

Figure 1. In our model, this flux is simplified by assuming dependence on the concentration of αKG (represented by

) and primarily on the level of NADH:

The parameter value is set to

. The effect of NADH on this flux is closely linked to the activity of UCP2 channels, which facilitate the net transfer of carbon from α-KG to GABA (see inset of

Figure 1). Elevated NADH levels reflect a high cellular energy state and lead to an oversupply of electrons to the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC). This oversupply can slow the overall rate of electron flow due to limited availability of downstream electron acceptors, thereby increasing the mitochondrial membrane potential and promoting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS, in turn, activate UCP2 channels, which reduce the membrane potential and limit further ROS accumulation. The principal net cataplerotic flux enabled by this mechanism is illustrated in the inset of

Figure 1, showing the redistribution of carbon from

to

via cytosolic Glu production and subsequent conversion to GABA. Critically, UCP2 plays a central role as a C4 metabolite carrier, enabling the export of intermediates such as Mal and OAA from the mitochondrial matrix to the cytosol [

25,

26,

27]. This supports cytosolic Glu synthesis and downstream GABA production, thereby completing the cataplerotic arm of the GABA shunt.

The dynamics of pool

, which represents the metabolites in the left-hand segment of the TCA cycle, is described by the following equation:

where the fluxes (Eq. 7) and (Eq. 9) have been defined previously.

The flux

accounts for the anaplerotic input into the left-hand segment of the TCA cycle via the GABA shunt, with succinate as the key product replenishing the cycle. The GABA shunt is a three-step enzymatic pathway in which Glu is first converted to GABA by Glu decarboxylase (GAD), then to succinic semialdehyde by GABA transaminase (GABA-TK), and finally to succinate by succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH). This pathway bypasses the αKGDH step and provides an alternative route of carbon entry into the TCA cycle (see

Figure 1).

Among the enzymes involved, SSADH is directly dependent on NAD+ and produces NADH in its final step. While GAD and GABA-TK do not consume NADH, GAD is known to be inhibited by elevated NADH levels, linking the redox state of the cell to the activity of the GABA shunt and ultimately the magnitude of flux

[

9].

Given that pancreatic beta cells express the full set of enzymes required for GABA shunt activity [

28], this pathway is metabolically relevant under physiological conditions. In our model, we describe

as a function of GABA concentration (

) while incorporating the inhibitory effect of NADH on GAD, which in turn modulates downstream GABA-TK activity and thereby the overall magnitude of the GABA shunt:

with parameter value

.

Finally, the dynamics of the GABA pool (

) is modeled as:

where flux is defined in Eq. 10 and in Eq. 12.

3. Results

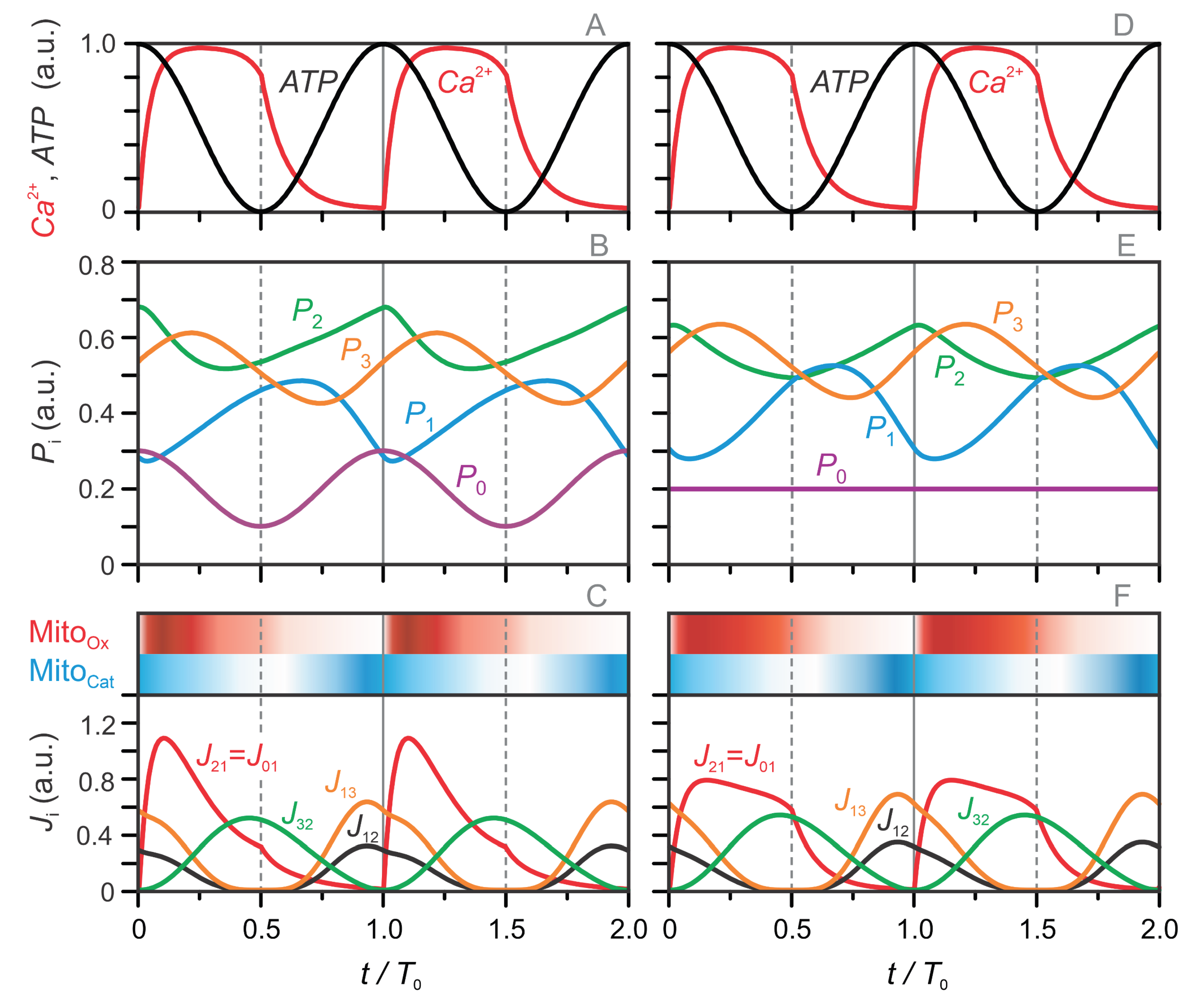

The model equations (Eqs. 1–13) were used to simulate the temporal evolution of metabolite concentrations across all four metabolic pools (

–

). These simulations also incorporate the dynamics of Ca²⁺ and ATP, which act as key regulatory inputs. For clarity, the time axis in

Figure 4 begins at the onset of the Ca²⁺ pulse.

Figure 4A presents the imposed oscillatory profiles of Ca²⁺ and ATP, while

Figure 4B and

Figure 4C show the corresponding dynamics of the metabolite pools and fluxes. The Ca²⁺ pulse initiates the oscillatory sequence by triggering a depletion of the left-side TCA intermediates in pool

. This depletion results from an increase in the flux

(

Figure 4C), which transfers carbon from

to the right-side TCA pool

. Simultaneously, Pyr derived from the glycolytic pool

enters the TCA cycle via PDH, contributing to the flux

. In our model,

is set equal to

, corresponding to the entry of acetyl-CoA into the TCA cycle. However, because Pyr entering via PDH is fully oxidized, it does not contribute to the net replenishment of TCA intermediates in

. Consequently, this phase—driven by Ca²⁺-stimulated PDH activation—results in a net shift of carbon from

to

and marks the onset of the mitochondrial oxidative (Mito

Ox) phase, highlighted in red in

Figure 4C.

Shortly thereafter, the GABA pool (

) becomes active, as seen in the declining

trajectory in

Figure 4B. This anaplerotic contribution via the GABA shunt replenishes

through flux

(

Figure 4C), compensating for its earlier depletion. Because

was initially emptied into

, it is now capable of accepting fresh carbon from

. This transfer is crucial for maintaining TCA cycling and OxPhos. As a result,

continues to accumulate while

declines. This orchestrated sequence—

→

, then

→

—builds a TCA cycle rich in carbon intermediates, sustaining NADH/FADH₂ production and oxidative metabolism during the Mito

Ox phase.

As ATP levels rise, the system transitions into the mitochondrial cataplerotic phase (Mito

Cat), indicated by the blue-shaded region in

Figure 4C. In this phase, the TCA cycle—now saturated with carbon—shifts toward net efflux. UCP2 channels facilitate the export of C₄ dicarboxylates such as OAA, Asp, and Mal, while Cit and αKG are exchanged for Mal in the cytosol. These fluxes promote the production of cytosolic Glu (see

Figure 1, inset) and contribute to carbon redistribution from

back to

and

, as reflected in rising

and

. As a consequence,

and

refill, while

becomes depleted (

Figure 4B), completing the transition from oxidative to cataplerotic metabolism.

During the final stage of the MitoCat phase, the PEP cycle becomes fully active. This enables localized ATP production near the plasma membrane, particularly in microdomains adjacent to KATP channels. The locally elevated ATP concentration promotes KATP channel closure and initiates the next Ca²⁺ pulse, thereby restarting the cycle with a new MitoOx phase.

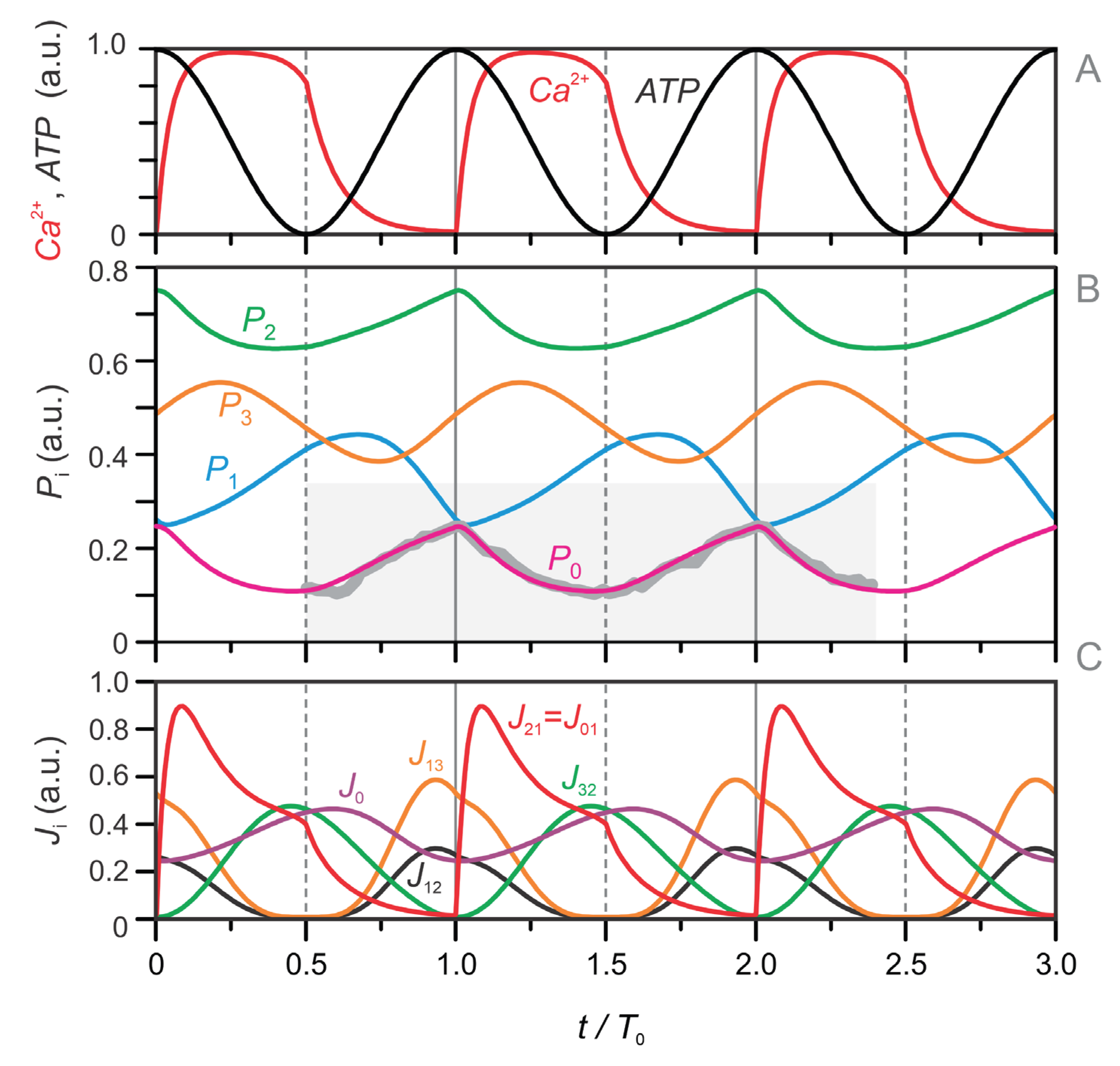

To evaluate the impact of glycolytic oscillations, we also simulated the model using a fixed value of

—representing the average level of the oscillatory

signal. The corresponding results are shown in

Figure 4D–F. All other model parameters and equations remained unchanged. A comparison between

Figure 4A–C and

Figure 4D–F reveals that glycolytic oscillations, while contributing to fine-tuning, are fully synchronized and functionally dependent on the rest of the system—particularly through ATP produced in the TCA cycle. Notably, the core oscillatory pattern remains intact even with constant

, underscoring the robustness and central regulatory role of the TCA–GABA oscillatory module.

To understand the coupling between glycolysis and TCA dynamics, it is crucial to recognize the central role of Ca²⁺. On one hand, Ca²⁺ pulses are triggered by ATP via K

ATP channels, thereby reflecting the redox state of the cell—particularly the metabolic activity within the TCA cycle. On the other hand, the sequestration of Ca²⁺ activates the TCA cycle, enhancing ATP production. This reciprocal Ca²⁺–TCA relationship—where Ca²⁺ both responds to and regulates mitochondrial metabolism—is tightly coupled to glycolysis. Specifically, Ca²⁺ directly influences the glycolytic–mitochondrial interface by promoting Pyr entry into the TCA cycle via PDH activation. This dual regulatory role of Ca²⁺ has been emphasized in previous modeling studies, particularly in the evaluation of the IOM model [

29]. Notably, Bertram et al. (2023) [

29] highlighted that the decline in FBP during the active (oxidative) phase results from elevated Ca²⁺ levels activating PDH, thereby accelerating the conversion of FBP-derived carbon into mitochondrial metabolism. This mechanistic coupling helps explain the experimentally observed “sawtooth” waveform of FBP [

3].

In our simplified model, we clearly emphasize the Ca²⁺-dependent flux

, consistent with the findings of Bertram et al. (2023) [

29]; however, we do not reproduce the characteristic sawtooth-shaped profile of FBP, as its dynamics are approximated by a sinusoidal function (Eq. 5). To capture the detailed waveform of FBP, the FBP pool (

) would need to be modeled explicitly using a differential equation. This would require not only the efflux term

, but also an influx term

representing the conversion from F6P to FBP. In the Appendix, we demonstrate how such an extension can be implemented to reproduce the sawtooth dynamics.

Appendix A1 presents the simplest approach, modeling

as a constant influx. In

Appendix A2, we introduce a more mechanistic formulation of

, which incorporates the well-known ATP and Cit inhibition of PFK1 [

30] and the positive feedback loop in which FBP enhances its own production by stimulating PFK1 activity [

31,

32,

33]. As shown in

Figure A2, this extended model shows good agreement with the experimentally observed sawtooth-shaped FBP oscillations [

3].

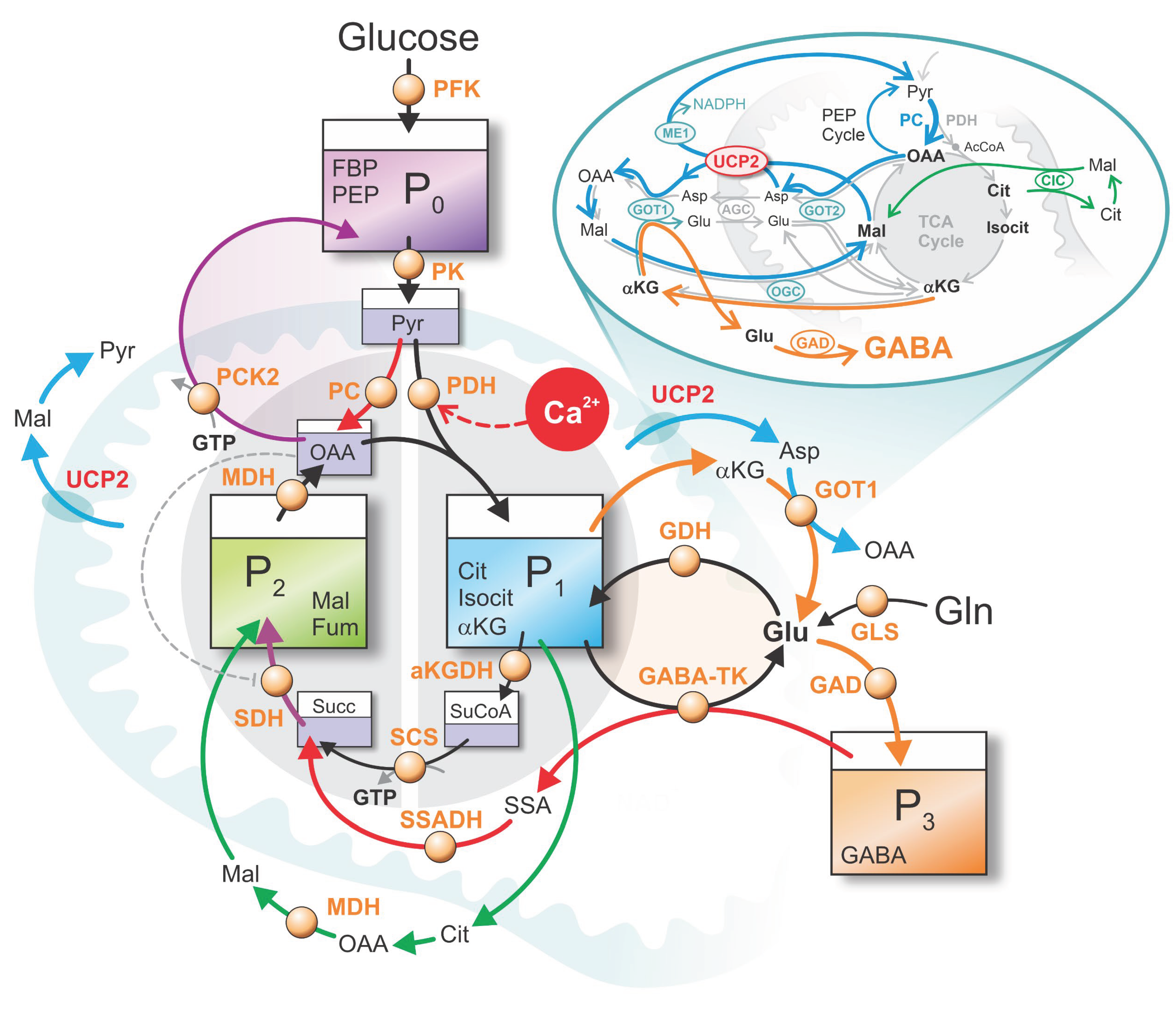

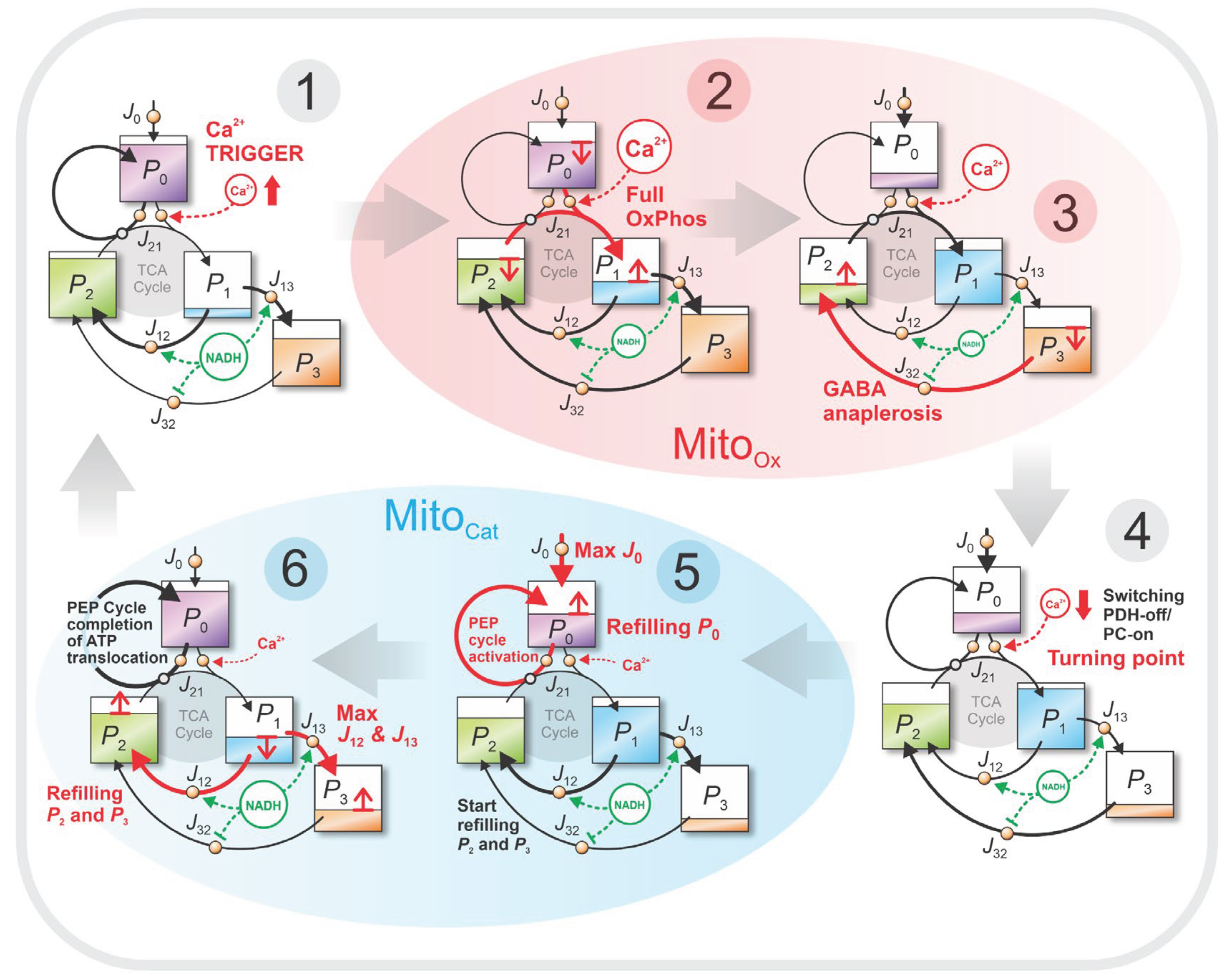

3.1. Stock–Flow Diagrams Illustrating Model Behavior

To enhance intuitive understanding of the model’s dynamic behavior, we present a sequence of stock–flow diagrams (

Figure 5) that illustrate the stepwise filling and emptying of the four metabolic pools (

–

) throughout the oscillatory cycle. These diagrams highlight the system’s progression through key transitional states and emphasize how metabolite pool levels and inter-pool fluxes evolve during the Mito

Ox and Mito

Cat phases.

In this representation, stocks refer to the concentrations of the metabolic pools (–), while flows denote the key metabolic fluxes: , , , , and . The glycolytic inflow is also shown for completeness, even though it is not explicitly defined in the core model. However, is analyzed in more detail in the Appendix.

Figure 5 illustrates six characteristic stages of the metabolic oscillation cycle:

Steps 2 and 3 represent the mitochondrial oxidative (MitoOx) phase (shaded red).

Steps 5 and 6 represent the mitochondrial cataplerotic (MitoCat) phase (shaded blue).

Steps 1 and 4 correspond to transitional phases that initiate/terminate the core oscillatory phases.

Step 1 – Ca²⁺-Triggered Entry into MitoOx Phase

This initial stage begins with a Ca²⁺ pulse that activates PDH, opening flux and allowing fresh carbon from the glycolytic pool to enter the TCA cycle. At this point, is relatively empty, primed to receive carbon from and . Fluxes and begin to rise in parallel, initiating the oxidative cycle.

Step 2 – Maximal OxPhos Phase

With strong PDH activation, high fluxes through

and

(highlighted in red) are initiated, leading to a temporary depletion of

. Note that

, because Cit formation in

requires an equal input of Pyr (from

) and Mal-derived OAA (from

). These high fluxes support NADH and FADH₂ production and active OxPhos. During this stage, the TCA cycle operates fully in the clockwise direction (gray-shaded cycle in

Figure 5), although the arrows are not drawn for the entire cycle. To avoid confusion with the graphical presentation, note that flux

is not part of the TCA cycle (see Eq. (9)); its arrow is shown outside the gray-shaded cycle.

Step 3 – GABA Shunt-Driven Anaplerosis

Following the temporary depletion of , the GABA shunt (via , shown in red) replenishes , allowing TCA cycling to continue. This carbon input from sustains the MitoOx phase by restoring balance between the left and right TCA segments ( and ) and by providing additional NADH and FADH₂ through GABA-derived succinate entering the TCA cycle.

Step 4 – Transition to MitoCat Phase

This stage represents the metabolic turning point. Rising ATP levels and accumulation of TCA intermediates, especially in , cause oxidative cycling to slow and begin reversing. This initiates cataplerosis—extrusion of TCA intermediates—together with cataplerotic refilling of and . As regulatory signals shift (including declining Ca²⁺ together, changes in NADH/NAD⁺, and other metabolites), glycolytic influx is redirected from PDH toward PC. This PDH-off/PC-on switch, under conditions of high GTP, activates the PEP cycle.

Step 5 –Growing Cataplerosis, PEP Cycling, andRefilling

Cataplerotic fluxes intensify, with carbon extruded from to and . At high GTP levels, and with rising ( reaching its maximum at this stage), fluxes through the PEP cycle increase, efficiently translocating ATP from mitochondria into cytosolic microdomains near KATP channels.

Step 6 – Cataplerotic Refilling ofandCataplerosis now reaches its full extent. As GTP declines (consumed by the active PEP cycle), UCP2 inhibition weakens, enabling strong extrusion of C₄ units—mainly Asp and Mal. Together with Cit–Mal shuttling, this drives redistribution of intermediates through cataplerotic pathways converting αKG into Glu and further into GABA (see inset of

Figure 1). Carbon is efficiently redistributed from

to both

and

via large fluxes

and

(red arrows outside the gray-shaded TCA cycle). This final stage prepares the system for the next oscillation:

and

are fully replenished, while

is in its final refilling phase. At the same time, the still-active PEP cycle completes ATP translocation to microdomains near K

ATP channels, setting the conditions for K

ATP channel closure and the next Ca²⁺ pulse.

3.2. Simulated Animation of Metabolic Pool Dynamics

To better illustrate the model’s oscillatory behavior, we created an animated visualization showing the cyclic emptying and refilling of the four metabolic pools. The animation was generated in

Blender and depicts the pools connected by pipelines, with fluxes represented as flowing liquid. It is based directly on the numerically simulated dynamics of the model in its most detailed form: the core system of equations described in the

Model section, with the dynamics of

defined explicitly as in

Appendix A1 and the

flux modeled with ATP-, FBP-, and Cit-dependent regulation as in

Appendix A2. This ensures that the animation faithfully reflects the simulated metabolite and flux oscillations. A snapshot from the animation is shown in

Figure 6, and the full video is available at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16951481.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed a mathematical model of beta cell dynamics that advances beyond canonical frameworks by integrating a more comprehensive representation of metabolic processes, including glycolysis, TCA cycle dynamics, and the interplay of key anaplerotic–cataplerotic pathways. We emphasize two critical anaplerotic routes. The first is Pyr carboxylation via PC, essential for supporting the PEP cycle—a mechanism crucial for fine-tuning Ca²⁺ pulses. Recent studies [

18,

34] have underscored the PEP cycle’s role in coordinating anaplerotic–cataplerotic cycling and in enabling spatially targeted ATP production near K

ATP channels, an understanding that contributed to the development of the Mito

Cat- Mito

Ox model [

6], which we extend here. The second pathway is the GABA shunt, recently recognized as an important anaplerotic contributor to beta cell metabolism and insulin secretion [

9]. Together, these routes form the foundation of the Dual Anaplerotic Model, which synthesizes elements from the canonical framework, the Mito

Cat- Mito

Ox model, and emerging concepts around the GABA shunt [

35]. Importantly, DAM provides a new synergistic view in which the PC- and GABA shunt–driven anaplerotic routes function as interdependent and temporally coordinated processes: the GABA shunt reinforcing the Mito

Ox phase, and the PC-derived flux serving as a key element not only for PEP cycling, but also for cataplerotic replenishment of the GABA pool during the Mito

Cat phase, thereby enabling the coordinated redistribution of carbon across the pools defined in our model.

The model integrates glycolysis, TCA dynamics with anaplerosis and cataplerosis, and GABA metabolism into a tightly coupled system. This metabolic framework is further entrained with Ca²⁺ signaling, which plays a pivotal role in beta cell function. Although we did not explicitly model Ca²⁺ dynamics or plasma membrane electrophysiology, we linked experimentally observed Ca²⁺ oscillations to metabolic activity. This approach directly engages a long-standing debate: do Ca²⁺ oscillations drive metabolic oscillations, or do intrinsic metabolic oscillations drive Ca²⁺ and electrical activity [

5]? Early work suggested that intrinsic glycolytic oscillations arise in beta cells through PFK-M, which is subject to positive feedback from its product, FBP [

19]. Indeed, PFK-M was confirmed as the dominant isoform in beta cells [

32]. However, experiments clamping Ca²⁺ levels produced mixed outcomes: metabolic oscillations were sometimes suppressed [

36,

37] but in other cases persisted or were restored [

38]. Moreover, PFK-M knockout did not abolish slow oscillations in beta cells [

39,

40]. Marinelli et al. (2018) [

40] proposed that other isoforms, particularly PFK-P, may compensate—a hypothesis supported by simulations using the IOM. Importantly, the IOM also demonstrated that the hierarchy of oscillatory control can vary by context: in some conditions, electrical and Ca²⁺ oscillations drive metabolism, whereas in others, intrinsic metabolic oscillations set the pace for Ca²⁺ and electrical activity [

41].

Our model demonstrates that glycolytic oscillations, while important, are not the sole pacemaker. The simple fact that, for example, glycolytic oscillations in intact yeast cells have a period of about ~1 min [

42] whereas in beta cells the period is ~5 min [

3] clearly shows that the glycolytic apparatus is not a fixed, pre-determined system. Moreover, for yeast, Richard (2003) [

43] demonstrated that the oscillation frequency is highly adaptable to environmental conditions—for instance, under aerobic conditions, oscillatory metabolism can occur at much lower frequencies. In beta cells, glycolytic oscillations appear to function as an entrained subsystem within a tightly synchronized network incorporating TCA metabolism and the GABA shunt. Here, the majority of ATP production occurs in mitochondria—particularly during the Mito

Ox phase—while a substantial fraction of ATP is consumed by Ca²⁺-ATPases. Consequently, glycolysis adapts its rhythm to align with mitochondrial ATP supply and Ca²⁺-dependent ATP consumption. As shown in our model, glycolysis is entrained by the slower, dominant TCA–GABA–Ca²⁺ module, which, as the primary timing element, serves as the effective pacemaker for GSIS. This entrainment ensures that glycolysis delivers carbon intermediates precisely when the TCA cycle and GABA shunt are optimally positioned to convert them into ATP and GTP. Such coordination maximizes metabolic efficiency and synchronizes ATP availability with the timing of K

ATP channel closure and Ca²⁺ influx, thereby enhancing the precision and robustness of pulsatile insulin secretion. Notably, the oscillatory behavior persists even in a reduced three-pool model (

,

, and

) with constant

, underscoring the robustness and central regulatory role of the TCA–GABA–Ca²⁺ module in sustaining dominant ATP fluxes and coordinating critical anaplerotic–cataplerotic transitions.

Although the model includes Pyr entry via PC and carbon input through the GABA shunt, these anaplerotic fluxes are counterbalanced by cataplerotic outflows, rendering the system a quasi-closed loop governed primarily by internal fluxes among

,

, and

. Importantly, the net anaplerotic fluxes are modest—consistent with experimental evidence showing that more than 80% of the utilized glucose is oxidized [

44]. This indicates that beta cells prioritize signaling over biomass production, consistent with their endocrine role. Accordingly, anaplerotic–cataplerotic cycling in beta cells is best understood as serving regulatory and signaling functions rather than biosynthetic needs [

45]. Nevertheless, biosynthesis—particularly of FFA—remains important in beta cells and can be tightly coupled to signaling. For example, short-chain acyl-CoAs derived from Cit cataplerotically exported from mitochondria have been shown to exert potent regulatory effects on beta cell function, especially in rodent islets [

46]. More recently, it has been proposed that FFA biosynthesis may contribute to GSIS by replenishing membrane lipids required for vesicle-mediated exocytosis and/or by providing an electron sink to balance increased glucose catabolism [

47]. In particular, the biosynthetic role may be crucial during beta cell development, as evidenced by recent findings of enhanced reductive TCA cycle activity in human pluripotent stem cell–derived islets [

48]. These results underscore the importance of considering both oxidative and reductive TCA pathways, providing strong conceptual support for Mito

Cat-Mito

Ox models.

The dynamics of TCA metabolites—and their fluctuations in the cytosol via cataplerotic export—have been measured with high temporal resolution, allowing direct comparison with our model predictions. Unlike previous frameworks, our approach explicitly tracks TCA pools, capturing the dynamic redistribution of key intermediates. A particularly compelling line of evidence comes from MacDonald et al. (2003) [

49], who measured mitochondrial Cit oscillations and identified Cit as the most prominently oscillating TCA intermediate. Consistently, our simulations predict that Cit oscillations are the most pronounced among TCA metabolites: the

pool is emptied during the Mito

Ox phase (via fluxes from

and

), replenished via

and the GABA shunt, and then depleted again during Mito

Cat. The timing of maximal cataplerotic flux (

) in our model coincides with the experimentally observed anti-phasic oscillations of cytosolic Cit reported by Gregg et al. (2019) [

17]. Furthermore, MacDonald et al. (2003) [

49] demonstrated that mitochondrial Cit continues to oscillate even under constant Pyr supply, indicating that these fluctuations arise from intrinsic TCA dynamics—fully consistent with our model’s prediction of the dominant role of the TCA–GABA module. In addition, they emphasized citrate’s function as a potent PFK inhibitor, capable of modulating glycolytic flux and synchronizing mitochondrial activity. This feedback role of Cit strongly supports our concept of a synergistic, integrated metabolic network in which glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and the GABA shunt operate in tight coordination. Incorporating this feedback mechanism directly into our model has contributed to the improved predictive accuracy described in

Appendix A2.

Similarly, Glu dynamics align closely with our predicted cataplerotic pattern. Lewandowski et al. (2020) [

18] reported that cytosolic Glu levels peak during the Mito

Cat phase, in agreement with elevated J₁₃ flux in our model and with αKG-to-Glu conversion as mechanistically described in Grubelnik et al. (2024) [

7]. Beyond its amplifying role in insulin secretion [

7], Glu also contributes to refilling the GABA pool (

) toward the end of the Mito

Cat phase. This timing is consistent with the observations of Menegaz et al. (2019) [

28], who showed pulsatile GABA dynamics and proposed that GABA contributes both to terminating insulin secretion bursts and to synchronizing the rhythm of pulsatile release. In our model, GABA replenishment at the end of the Mito

Cat phase aligns precisely with these experimental findings, linking cataplerotic fluxes to both the termination and resynchronization of GSIS cycles.

Finally, we emphasize that the DAM is intentionally constructed as a minimal model. Several dynamic components are taken directly from experimental observations rather than modeled explicitly, and the modeled dynamics are simplified to focus primarily on phase relationships and the sequential filling and emptying of metabolic pools. As a result, the detailed waveforms of certain metabolites are only approximated. For example, while FBP was represented as a smooth sinusoid in the core model,

Appendix A2 demonstrates that its experimentally observed “sawtooth” profile [

3] can be reproduced through more detailed modeling of the glycolytic influx

. This highlights that the DAM is not a final or exhaustive description but rather a flexible, modular framework.

The strength of this approach lies in its modularity, which allows systematic refinement and extension. Future work could focus on incorporating more detailed representations of glycolysis, explicitly modeling PFK isoform-specific regulation, or extending the TCA module to include parallel shuttles and redox-balancing mechanisms. Similarly, the role of the GABA shunt in shaping pulsatile insulin secretion could be further explored by integrating its interaction with Glu metabolism and neurotransmitter-like signaling effects. Another important direction is to couple the metabolic core more explicitly with electrophysiological models of the plasma membrane, thereby linking metabolic oscillations with membrane potential dynamics and Ca²⁺ handling. Together, these refinements would provide a more comprehensive explanation of how the interplay between metabolic, electrical, and Ca²⁺ oscillations coordinates pulsatile insulin secretion under both physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Thus, while the DAM is intentionally minimal by design, its modular architecture provides a robust foundation for iterative refinement. By bridging experimental evidence with mechanistic modeling, it offers a promising platform for future investigations into the metabolic and signaling networks that govern beta cell oscillatory function and GSIS.