Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Allergic Rhinitis Prediction Through Machine Learning: Integrating Environmental, Immunologic, and Demographic Factors

Literature Review

Global Prevalence and Public Health Significance of Allergic Rhinitis

Understanding Different Types of Allergic Rhinitis

Genetic, Immunologic, and Epigenetic Contributions

Environmental and Social Effects on Allergic Rhinitis

Climate Change and Environmental Risk Factors

Advances in Technology and Precision Medicine

Current Challenges and Limitations in Allergic Rhinitis Research

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

Variables

Data Analytic Plan

Results and Discussion

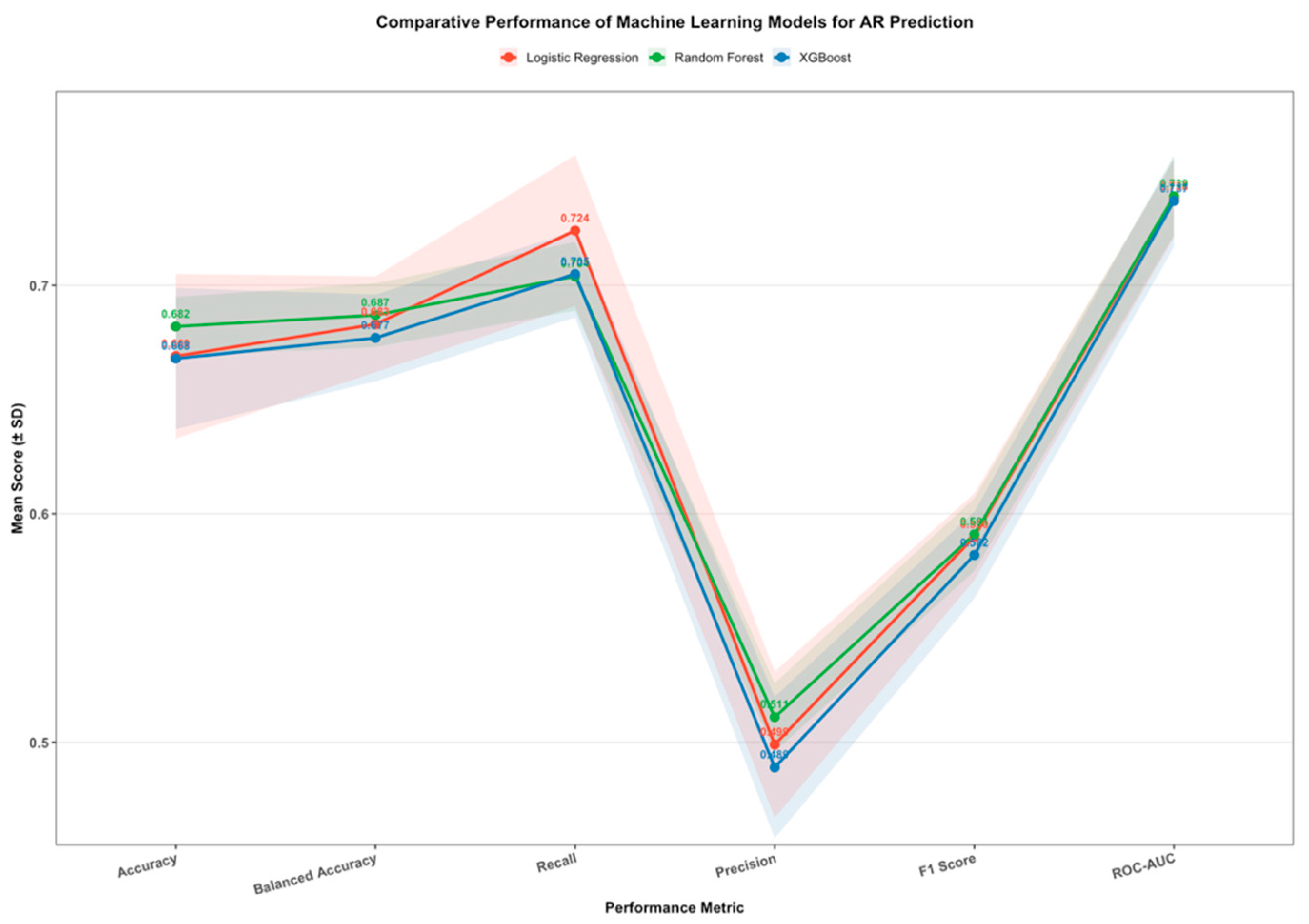

Model Comparison and Selection

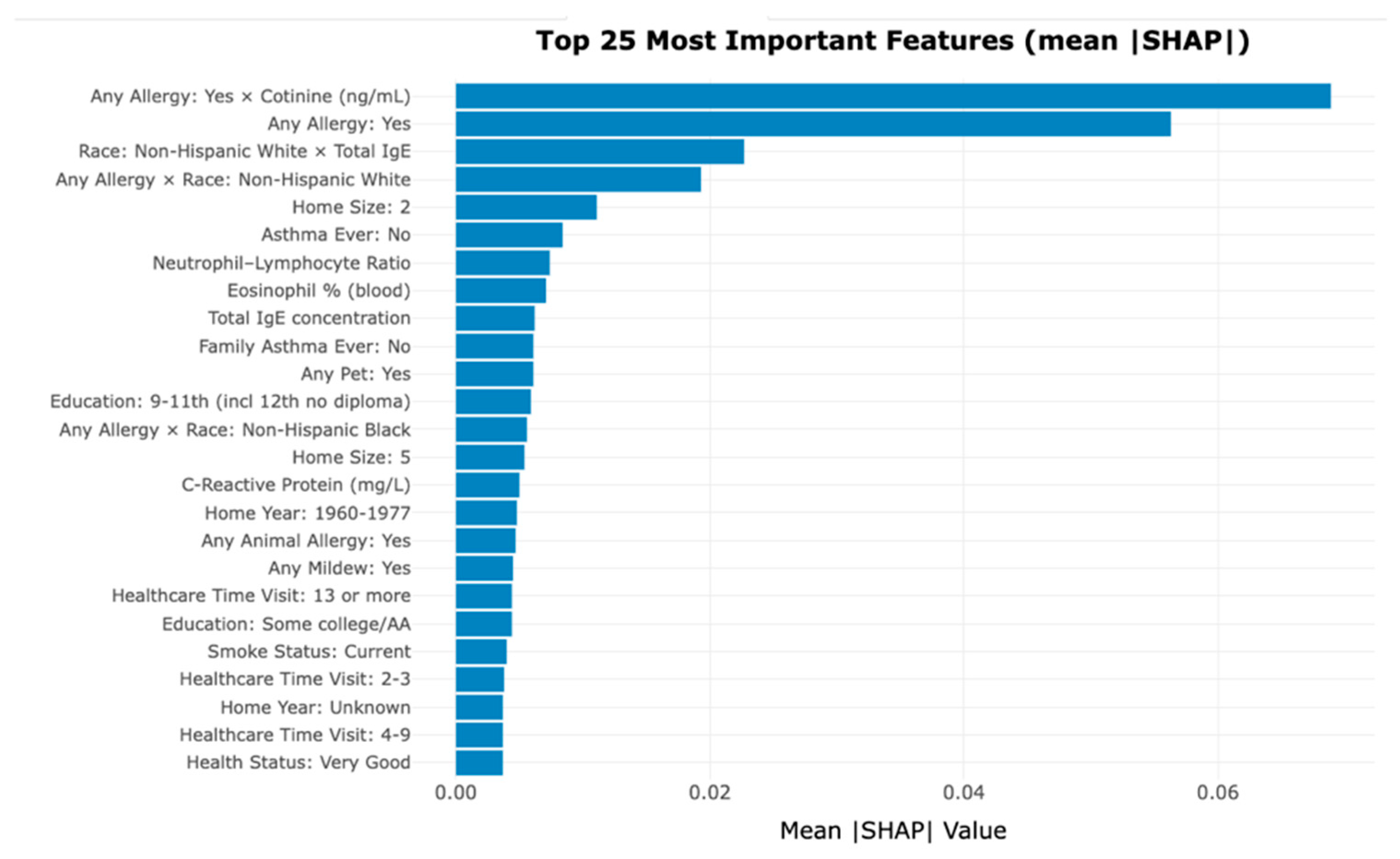

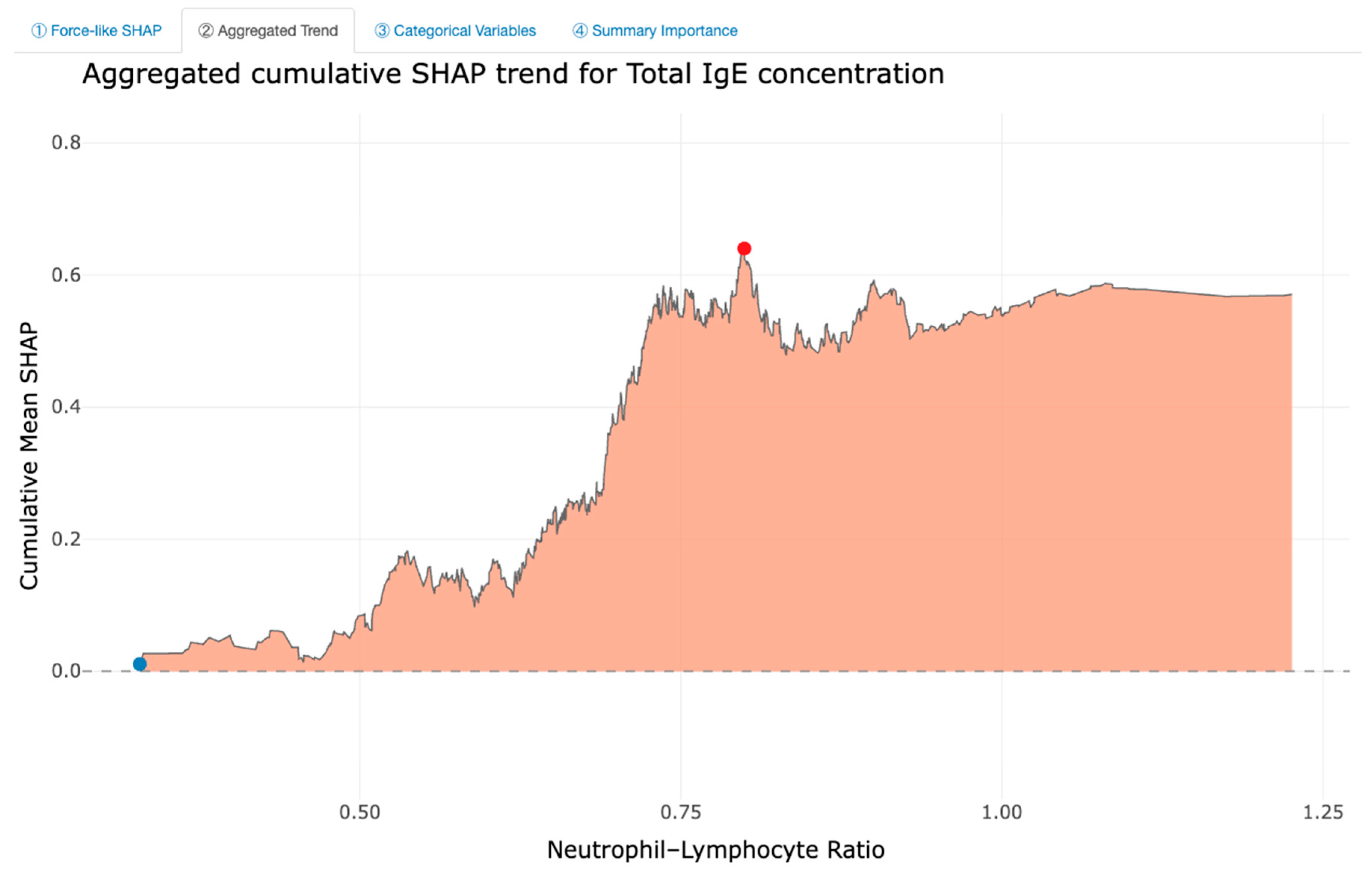

Feature Importance and Interpretability

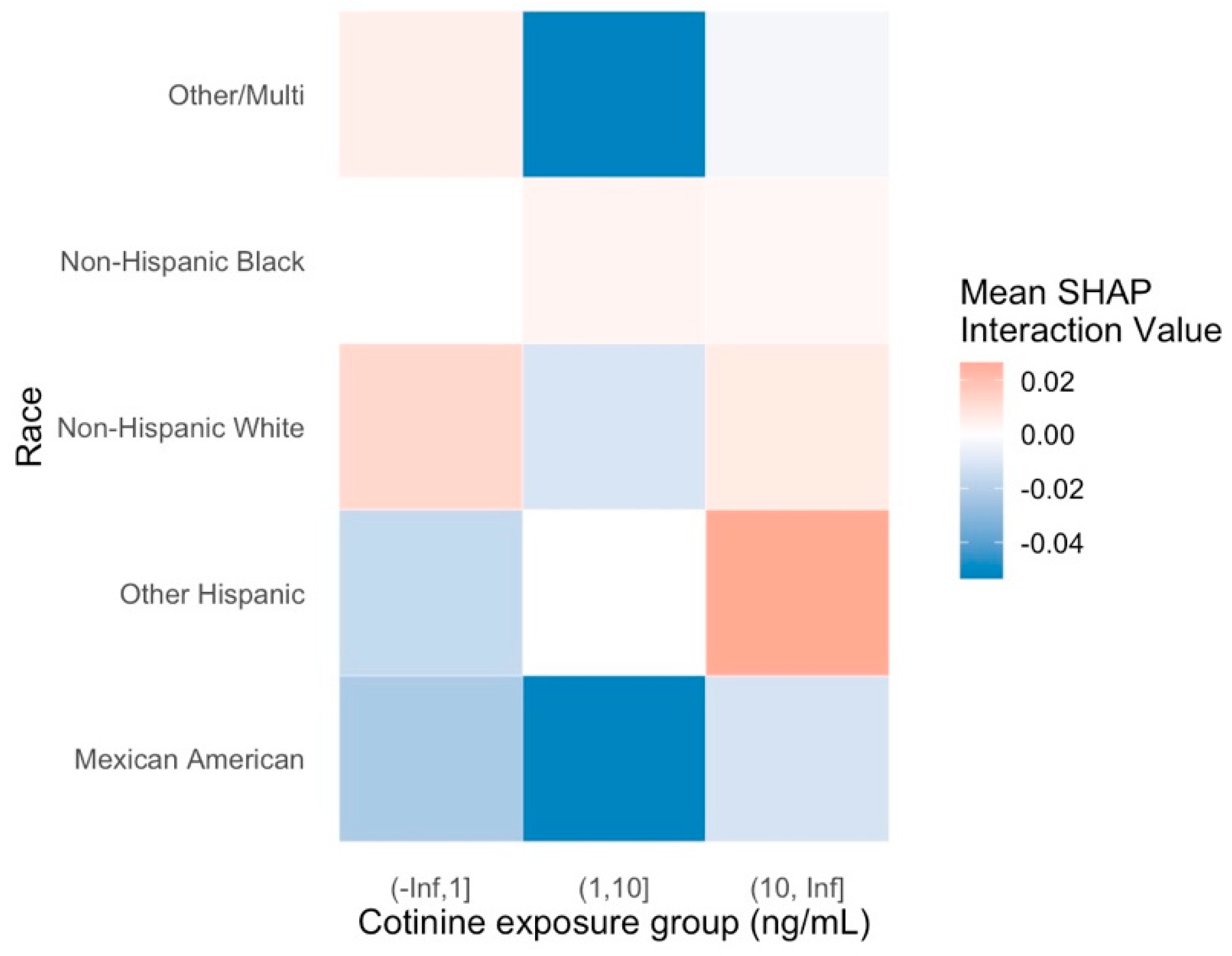

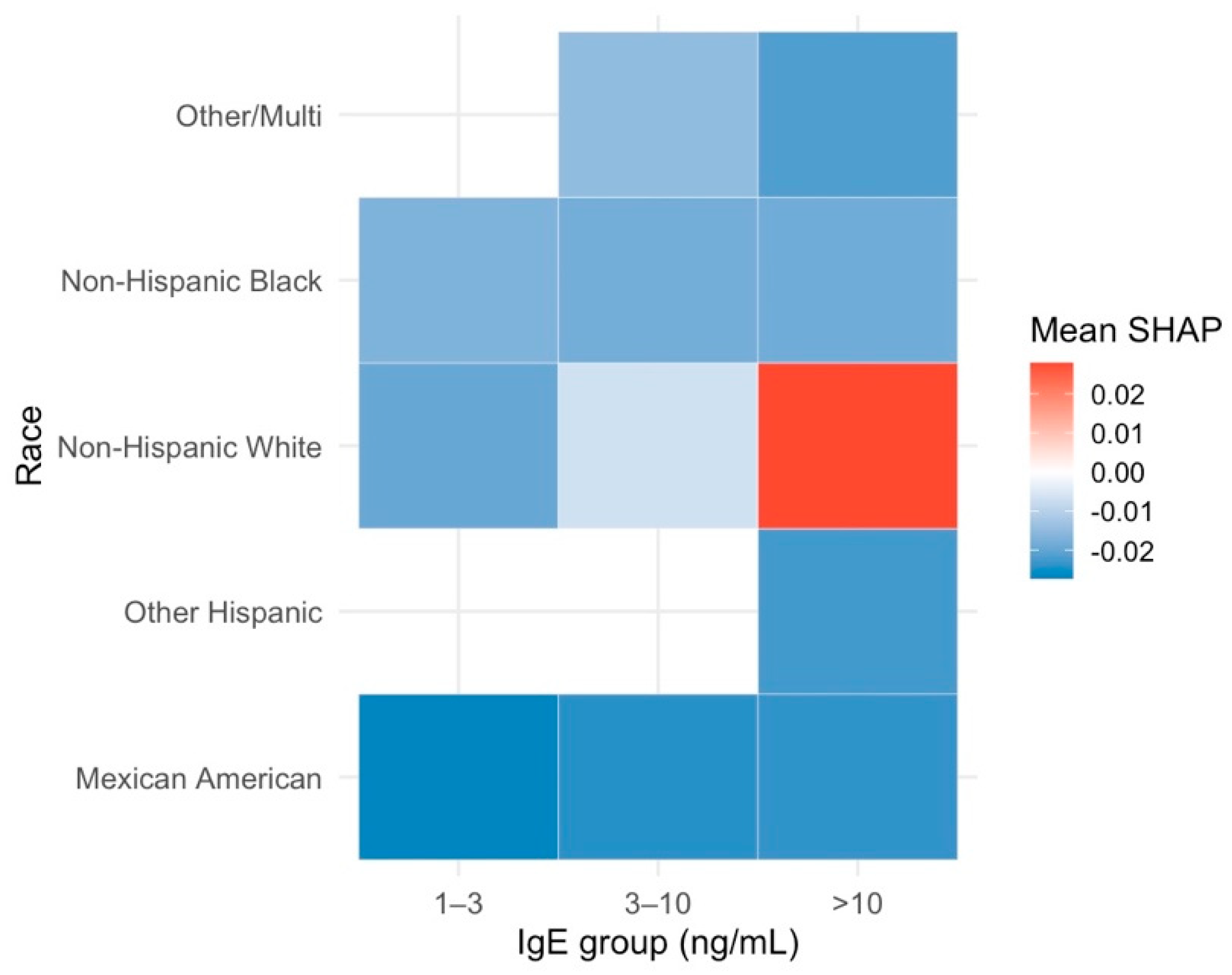

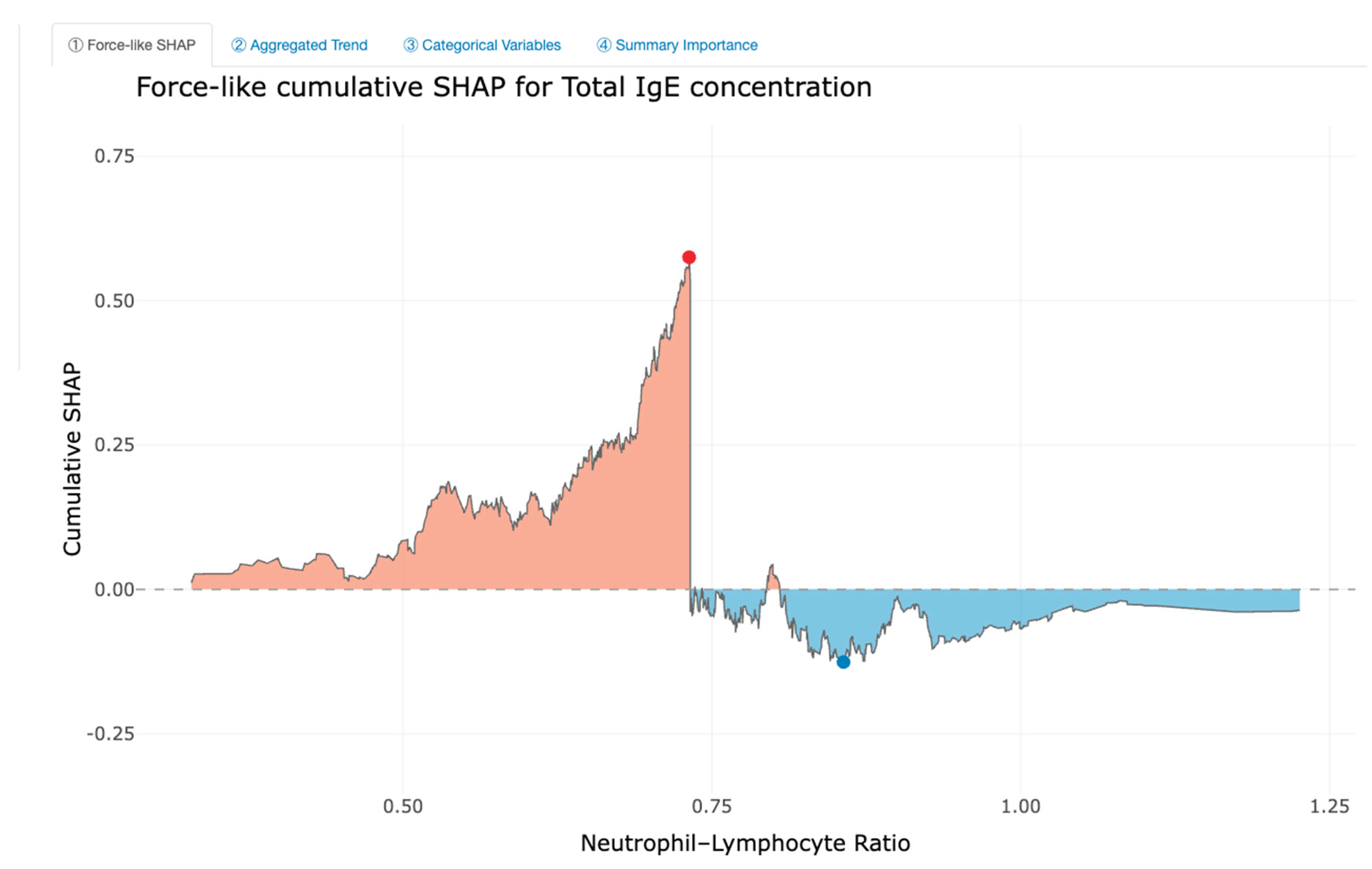

Interaction and Cross-Factor Effects

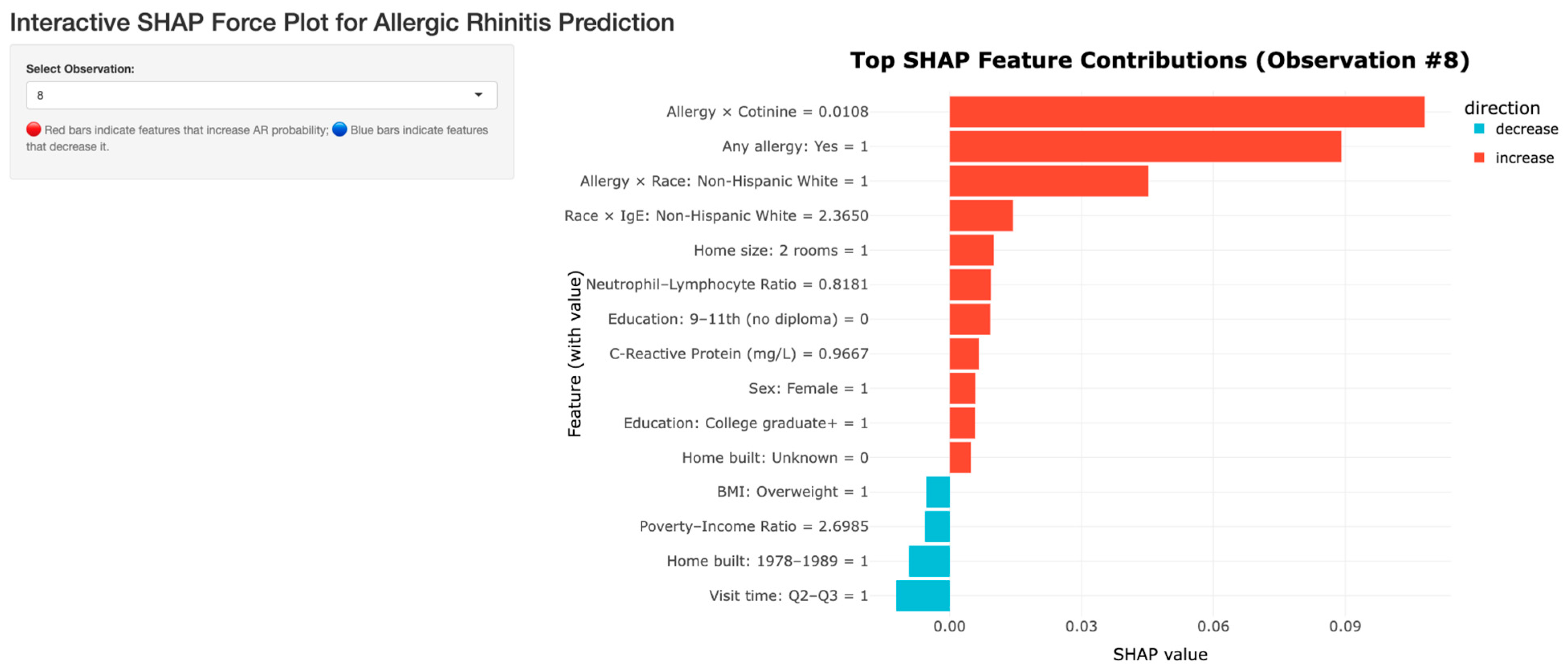

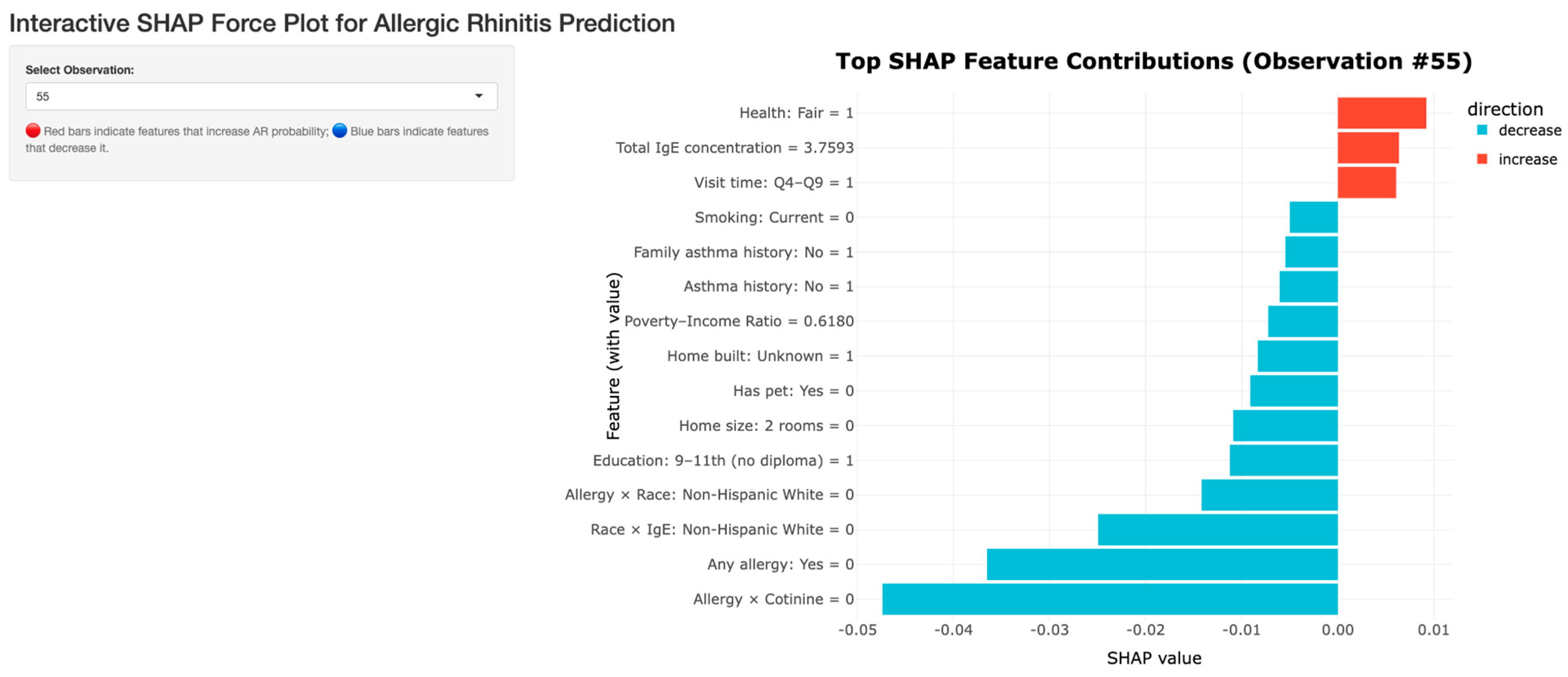

Individual SHAP Interactions Dashboard

Grouped SHAP Interaction Dashboard

Conclusions

Data Availability

Code Availability

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agache, I.; Akdis, C.; Akdis, M.; Al-Hemoud, A.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Balmes, J.; Cecchi, L.; Damialis, A.; Haahtela, T.; Haber, A. L.; Hart, J. E.; Jutel, M.; Mitamura, Y.; Mmbaga, B. T.; Oh, J.-W.; Ostadtaghizadeh, A.; Pawankar, R.; Johnson, M.; …Nadeau, K. C. Climate change and allergic diseases: A scoping review. The Journal of Climate Change and Health 2024, 20, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Khaltaev, N.; Cruz, A. A.; Denburg, J.; Fokkens, W. J.; Togias, A.; Zuberbier, T.; Baena-Cagnani, C. E.; Canonica, G. W.; van Weel, C.; Agache, I.; Aït-Khaled, N.; Bachert, C.; Blaiss, M. S.; Bonini, S.; Boulet, L. P.; Bousquet, P. J.; Camargos, P.; Carlsen, K. H.; …Williams, D. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update. Allergy 2008, 63(s86), 8–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Schünemann, H. J.; Togias, A.; Bachert, C.; Erhola, M.; Hellings, P. W.; Klimek, L.; Pfaar, O.; Wallace, D.; Ansotegui, I.; Agache, I.; Bedbrook, A.; Bergmann, K.-C.; Bewick, M.; Bonniaud, P.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Bossé, I.; Bouchard, J.; Boulet, L.-P.; …Zuberbier, T. Next-generation Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines for allergic rhinitis based on Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) and real-world evidence. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2020, 145(1), 70–80.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausing, E. S.; Tomlinson, C. J.; Non, A. L. Epigenetics and social inequalities in asthma and allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2023, 151(6), 1468–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damialis, A.; Gilles, S. Air quality in the era of climate change: Bioaerosols, multi-exposures, and the emerging threats of respiratory allergies and infectious diseases. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 46 2025, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramburg, S.; Grittner, U.; Potapova, E.; Travaglini, A.; Tripodi, S.; Arasi, S.; Pelosi, S.; Acar Şahin, A.; Aggelidis, X.; Barbalace, A.; Bourgojn, A.; Bregu, M.; Brighetti, M. A.; Caeiro, E.; Caminiti, L.; Charpin, D.; Couto, M.; Delgado, L.; …Matricardi, P. M. Heterogeneity of sensitization profiles and clinical phenotypes among patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis in Southern European countries—The @IT.2020 multicenter study. Allergy 2024, 79(4), 908–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espada-Sánchez, M.; Sáenz de Santa María, R.; Martín-Astorga, M. C.; Lebrón-Martín, C.; Delgado, M. J.; Eguiluz-Gracia, I.; Rondón, C.; Mayorga, C.; Torres, M. J.; Aranda, C. J.; Cañas, J. A. Diagnosis and treatment in asthma and allergic rhinitis: Past, present, and future. Applied Sciences 2023, 13(3), 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Zhao, C.; Yang, J.; Meng, Y.; Tian, S.; Qian, Y.; Yu, S. Artificial intelligence applications in allergic rhinitis diagnosis: Focus on ensemble learning. Asia Pacific Allergy 2024, 14(2), 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haahtela, T. A biodiversity hypothesis. Allergy 2019, 74(8), 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-C.; Zou, M.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Jiang, C.-B.; Wu, C.-D.; Lung, S.-C. C.; Chien, L.-C.; Lo, Y.-C.; Chao, H. J. Effects of indoor air quality and home environmental characteristics on allergic diseases among preschool children in the Greater Taipei Area. Science of the Total Environment 897 2023, 165392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, E.; Cucco, A.; Custovic, A.; Fontanella, S. Machine learning in allergy research: A bibliometric review. Immunology Letters 277 2026, 107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothalawala, D. M.; Murray, C. S.; Simpson, A.; Custovic, A.; Tapper, W. J.; Arshad, S. H.; Holloway, J. W.; Rezwan; F. I; on behalf of STELAR/UNICORN investigators. Development of childhood asthma prediction models using machine learning approaches. Clinical and Translational Allergy 2021, 11(10), e12076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Krogulska, A. Clinical relevance of cluster analysis in phenotyping allergic rhinitis in the paediatric population of the Kuyavian Pomeranian voivodeship, Poland. Postępy Dermatologii i Alergologii 2024, 41(1), 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larenas-Linnemann, D. E. S.; Mayorga-Bustamante, J. L.; Patrón, J. L.; Maza-Solano, J.; Emelyanov, A. V.; Dolci, R. L.; Miyake, M. M.; Okamoto, Y.; …Okamoto, Y. Global expert views on the diagnosis, classification and pharmacotherapy of allergic rhinitis in clinical practice using a modified Delphi panel technique. World Allergy Organization Journal 2023, 16(7), 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Liu, Z.; Liao, H.; Yang, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, Q. Effects of early life exposure to home environmental factors on childhood allergic rhinitis: Modifications by outdoor air pollution and temperature. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 244 2022, 114076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malizia, V.; Cilluffo, G.; Fasola, S.; Ferrante, G.; Landi, M.; Montalbano, L.; Licari, A.; La Grutta, S. Endotyping allergic rhinitis in children: A machine learning approach. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 2022, 33(S27), 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdoganoglu, T.; Songu, M. The burden of allergic rhinitis and asthma. Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease 2011, 6(1), 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, K.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Fu, Q.; Liu, K.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, J.; Lu, L.; Li, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q. Prevalence and risk factors for allergic rhinitis in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022, 7165627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, T. T.; Grant, T. L.; Dantzer, J. A.; Udemgba, C.; Jefferson, A. A. Impact of socioeconomic factors on allergic diseases. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2024, 153(2), 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.; Keswani, A. The impact of social determinants and air pollution on healthcare disparities in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy 2023, 37(2), 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramratnam, S. K.; Johnson, M.; Visness, C. M.; Calatroni, A.; Altman, M. C.; Janczyk, T.; …Gern, J. E. Clinical and molecular analysis of longitudinal rhinitis phenotypes in an urban birth cohort. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2024, 155(2), 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarela, M.; Podgorelec, V. Recent applications of explainable AI (XAI): A systematic literature review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14(19), 8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Alizadehsani, R.; Cifci, M. A.; Kausar, S.; Rehman, R.; Mahanta, P.; Bora, P. K.; Almasri, A.; Alkhawaldeh, R. S.; Hussain, S.; Alatas, B.; Shoeibi, A.; Moosaei, H.; Hladík, M.; Nahavandi, S.; Pardalos, P. M. A review of explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare. Computers and Electrical Engineering 118 2024, 109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savouré, M.; Bousquet, J.; Leynaert, B.; Renuy, A.; Siroux, V.; Goldberg, M.; Zins, M.; Jacquemin, B.; Nadif, R. Rhinitis phenotypes and multimorbidities in the general population: The CONSTANCES cohort. European Respiratory Journal 2023, 61(6), 2200943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Yang, I. V.; Schwartz, D. A. Epigenetic regulation of immune function in asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2022, 150(2), 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H. M.; Tsai, F.-J.; Lee, Y.-L.; Chang, J.-H.; Chang, L.-T.; Chang, T.-Y.; Chung, K. F.; Kuo, H.-P.; Lee, K.-Y.; Chuang, K.-J.; Chuang, H.-C. The impact of air pollution on respiratory diseases in an era of climate change: A review of the current evidence. Science of the Total Environment 898 2023, 166340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia-Pereira, M.; Guidos-Fogelbach, G.; Solé, D. Climate changes, air pollution and allergic diseases in childhood and adolescence. Jornal de Pediatria 2021, 98(S1), S47–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Y. Risk factors of allergic rhinitis: genetic or environmental? Therapeutics and clinical risk management 2005, 1(2), 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Q.; Lu, C.; Qian, H.; Yang, X.; Sun, Y.; Norbäck, D. Effects of mold, water damage and window pane condensation on adult rhinitis and asthma partly mediated by different odors. Building and Environment 227 2023, 109814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A. C.; Dahlin, A.; Wang, A. L. The role of environmental risk factors on the development of childhood allergic rhinitis. Children 2021, 8(8), 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavuz, S. T.; Oksel Karakus, C.; Custovic, A.; Kalayci, Ö. Four subtypes of childhood allergic rhinitis identified by latent class analysis. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 2021, 32(8), 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lan, F.; Zhang, L. Advances and highlights in allergic rhinitis. Allergy 2021, 76(11), 3383–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).