1. Introduction

1.1. Clinical Background and Public Health Significance

Pharyngitis, commonly known as sore throat, represents one of the most frequent reasons for primary care visits worldwide, accounting for approximately 15 million annual consultations in the United States alone [

1]. The condition manifests as inflammation of the pharynx, with etiologies broadly categorized into bacterial and nonbacterial causes. Bacterial pharyngitis, predominantly caused by Group A Streptococcus (GAS), comprises 5–15% of adult cases and 15–30% of pediatric cases [

2,

3]. Accurate differentiation between bacterial and nonbacterial pharyngitis carries profound clinical and public health implications.

The clinical significance of accurate pharyngitis classification stems from two competing imperatives. First, untreated bacterial pharyngitis can progress to serious complications including acute rheumatic fever, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, and peritonsillar abscess [

4]. Timely antibiotic therapy reduces symptom duration, prevents transmission, and minimizes complication risks [

5]. Second, overprescription of antibiotics for viral pharyngitis—which accounts for 70–85% of cases—contributes significantly to the global crisis of antimicrobial resistance [

6]. The World Health Organization identifies antimicrobial resistance as one of the top ten global public health threats, with direct linkage to inappropriate antibiotic use in respiratory tract infections [

8].

Studies show that 60–70% of patients presenting with sore throat receive antibiotic prescriptions, despite only 5–15% having bacterial infections requiring treatment [

53,

54]. This overprescription is partly driven by diagnostic uncertainty: when physicians are unsure whether a case is bacterial or viral, they often prescribe antibiotics as a precautionary measure, contributing to the development of antibiotic-resistant pathogens [

41].

1.2. Current Diagnostic Challenges and Physician Disagreement

Standard diagnostic approaches combine clinical assessment with laboratory testing. The Centor criteria (fever, tonsillar exudates, tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy, absence of cough) provide clinical prediction rules, yet demonstrate only moderate diagnostic accuracy with sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 57% [

9]. Rapid Antigen Detection Tests (RADT) offer point-of-care results but exhibit variable sensitivity (70–90%) and require confirmation with throat culture in negative cases [

10]. Throat cultures remain the gold standard with 90–95% sensitivity, but require 24–48 hours for results, delaying treatment decisions [

11].

Beyond technical limitations, diagnostic challenges arise from inherent clinical ambiguity. Pharyngitis presentations frequently overlap between bacterial and viral etiologies, with considerable inter-physician variability in diagnosis. Studies report diagnostic concordance rates of only 60–80% among experienced clinicians for ambiguous cases [

12,

13,

39]. This diagnostic uncertainty—where even expert physicians disagree on the same presentation—is a fundamental characteristic of pharyngitis diagnosis, yet is rarely acknowledged in the artificial intelligence (AI) literature.

1.3. The Gap in Medical AI Evaluation: Ignoring Diagnostic Ambiguity

Recent advances in deep learning have demonstrated promising results in medical image classification across diverse domains including dermatology, radiology, and ophthalmology [

14,

15,

16]. The proliferation of smartphone cameras with high-resolution capabilities has enabled novel approaches to remote health monitoring and diagnosis [

17]. For pharyngitis specifically, smartphone-captured throat images offer potential for accessible, rapid screening in telemedicine and resource-limited settings.

Yoo et al. [

18] pioneered deep learning approaches for pharyngitis diagnosis, training convolutional neural networks on 131 pharyngitis images and 208 normal throat images. While demonstrating proof-of-concept with 87.5% accuracy, their study had significant limitations: reliance on web-sourced images of uncertain quality, synthetic data augmentation via CycleGAN that may not reflect real-world variability, single-label annotations without consideration of diagnostic uncertainty, and binary classification into severe vs. normal rather than bacterial vs. nonbacterial. Subsequent work has expanded dataset sizes and explored various architectures [

19,

20,

29], yet a fundamental question remains unaddressed:

How do AI models perform on cases where even expert physicians disagree?

Most medical AI research assumes ground truth labels are accurate and unambiguous. However, medical diagnosis inherently involves uncertainty, particularly for conditions with overlapping clinical presentations. Ignoring label uncertainty has several consequences:

Recent work in computer vision and medical imaging has begun addressing label noise and uncertainty through techniques such as soft labels, label smoothing, and probabilistic modeling [

21,

22,

23]. However, these approaches typically address random label noise rather than systematic uncertainty arising from genuine diagnostic ambiguity.

1.4. Research Objectives and Hypothesis

This study addresses the critical gap in consensus-based evaluation of AI diagnostic models through the following objectives:

Primary Objective: Develop and validate a physician consensus-based evaluation framework that stratifies AI model performance by diagnostic certainty, distinguishing between high-consensus (diagnostically clear) and low-consensus (diagnostically ambiguous) pharyngitis cases.

Hypothesis: We hypothesize that AI models, like human physicians, will perform well on clear cases where physician consensus is high, but will struggle on ambiguous cases where physicians disagree. Acknowledging this performance stratification is key to building trustworthy clinical decision support systems that appropriately defer to human judgment on uncertain cases.

Secondary Objectives:

Compare performance of Vision Transformer versus traditional convolutional neural network architectures for pharyngitis image classification

Evaluate the contribution of multimodal data fusion (clinical symptoms + imaging) compared to unimodal approaches

Analyze sensitivity/specificity trade-offs relevant to antibiotic stewardship and identify appropriate clinical deployment scenarios (rule-in vs. rule-out)

Characterize error patterns to understand sources of diagnostic ambiguity

1.5. Contributions

Our work makes the following contributions to medical AI and clinical decision support:

Public pharyngitis imaging dataset with multi-physician validation: 742 high-resolution smartphone images with independent evaluation by 4–9 physicians per case (mean 6.2 physicians), exceeding prior public datasets by 5.7-fold [

18]

Novel consensus-based evaluation framework: First systematic stratification of AI performance by physician agreement levels, providing clinically interpretable metrics that acknowledge diagnostic uncertainty

Comprehensive architectural comparison: First study comparing Vision Transformers to CNNs for pharyngitis diagnosis, including multimodal fusion strategies (Late Fusion, Gated Fusion, Cross-Attention)

Clinically-oriented analysis for antibiotic stewardship: Focus on sensitivity/specificity trade-offs and actionable insights for reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions while ensuring patient safety

Detailed error analysis: Characterization of false positive and false negative patterns to understand sources of diagnostic ambiguity

Open-source resources: Public release of dataset, code, and evaluation framework to accelerate future research

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work in pharyngitis diagnosis, multimodal fusion, Vision Transformers, and AI evaluation under uncertainty;

Section 3 describes dataset curation, model architectures, and consensus-based evaluation methodology;

Section 4 presents results stratified by consensus groups with detailed error analysis;

Section 5 discusses clinical implications, limitations, and future directions;

Section 6 concludes with key takeaways for safe medical AI deployment.

2. Related Work

The present study is grounded in four major areas of machine learning applications in medicine: pharyngitis and ENT diagnosis, multimodal fusion strategies, Vision Transformer architectures, and AI evaluation under clinical uncertainty.

2.1. Deep Learning for Pharyngitis and ENT Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of pharyngitis is vital for effective antimicrobial stewardship [

30]. Historically, clinical management relied on scoring systems like the Centor score [

37], but these methods often lack the required precision, contributing to antibiotic overuse [

54]. Recent advances have focused on utilizing deep learning for direct diagnostic assistance.

Yoo et al. [

18] pioneered smartphone-based pharyngitis diagnosis using CNNs trained on 339 images (131 pharyngitis, 208 normal), achieving 87.5% accuracy for severe pharyngitis detection. However, their study relied on web-scraped images augmented with CycleGAN, raising concerns about real-world applicability. More recently, Shojaei et al. [

19] released a public pharyngitis dataset and demonstrated baseline CNN performance, but did not address diagnostic uncertainty or physician disagreement.

Studies have explored AI-driven approaches for telehealth strep throat screening using smartphone-captured images, showing promising accuracy and potential for remote diagnostics [

29]. Patel et al. demonstrated that explainable AI can improve telehealth accuracy by highlighting relevant pharyngeal features to remote clinicians. Furthermore, applications in related ENT domains—such as classification of middle ear disease using multimodal frameworks combining otoscopic images with clinical data [

28], and respiratory sound analysis for lung disease diagnosis [

45]—demonstrate the broader feasibility of integrating visual and non-visual data for ENT conditions.

Our work extends this literature by: (1) providing the largest real-world pharyngitis imaging dataset with multi-physician annotations, (2) comparing CNNs to Vision Transformers, (3) evaluating multimodal fusion strategies, and (4) introducing consensus-based performance stratification.

2.2. Multimodal Data Fusion Architectures in Healthcare

The integration of disparate data sources—such as medical images and tabular clinical information (symptoms and demographics)—is a critical challenge in clinical AI [

42]. Our work directly compares several established and advanced fusion techniques.

Traditional methods involve Early Fusion (concatenating raw features before processing) or Late Fusion (combining modality-specific predictions) [

47,

69]. More advanced approaches utilize Attention Mechanisms [

46,

71] to dynamically weigh the importance of features from each modality. Our Gated Fusion model learns modality weights through a gating network [

55], while our Cross-Attention model implements bidirectional attention between image and symptom representations [

56,

73].

Reviews of multimodal AI systems in healthcare emphasize the superior diagnostic potential of combining imaging features with clinical metadata, especially in high-stakes domains like radiology [

31,

32]. However, they also highlight the difficulty in achieving significant gains over strong unimodal image baselines [

35,

77]—a finding echoed in our results, where image-only models outperformed or matched multimodal fusion.

2.3. Vision Transformers (ViT) in Medical Imaging

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), such as ResNet [

48] and DenseNet [

50], have long been the gold standard for medical image analysis due to their translation equivariance and hierarchical feature learning. However, the Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture [

49], initially developed for general vision tasks, has gained traction in medicine due to its ability to model global contextual relationships via self-attention [

33,

34,

44].

ViT divides images into patches and processes them through transformer encoders, enabling long-range dependency modeling without the locality constraints of convolutional kernels [

84]. Studies show ViT advantages in medical imaging tasks requiring global context—such as chest X-ray diagnosis, fundus image analysis, and pathology whole-slide imaging [

85,

86]—though CNNs often remain competitive on smaller datasets.

Our study provides the first direct comparison of ViT versus CNN for pharyngitis diagnosis, demonstrating that ViT’s global attention mechanism offers modest improvements in capturing pharyngeal features distributed across the image (tonsillar exudate, erythema, uvular position).

2.4. AI Evaluation, Clinical Disagreement, and Decision Analysis

A major limitation of previous AI studies is the reliance on simplified aggregate metrics (e.g., overall AUC), which do not reflect the model’s reliability across different levels of diagnostic uncertainty [

43,

52]. Clinical practice is often characterized by significant inter-rater variability and disagreement, even among experts [

39,

90].

Our consensus-based evaluation framework directly addresses this by stratifying performance into High-Consensus (clear) and Low-Consensus (ambiguous) cases, drawing parallels to foundational work in medical decision-making under uncertainty [

36,

92]. Fine et al. demonstrated that optimal pharyngitis management requires acknowledging diagnostic uncertainty and tailoring interventions accordingly.

We employ advanced statistical methods—McNemar’s test [

60] for rigorous model comparison and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) principles [

61,

96]—to provide clinically interpretable metrics of Net Benefit, bridging the gap between statistical accuracy and real-world therapeutic value. Recent work on quantifying diagnostic uncertainty using Bayesian deep learning and ensemble methods [

51,

98] complements our approach by providing confidence estimates, though we focus on performance stratification rather than uncertainty quantification.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Description

This study utilizes the publicly available BasePharyngitis dataset introduced by Shojaei et al. [

19]. The original data collection was conducted across two geographically and climatically distinct regions of Iran (Shahrekord and Bushehr) to ensure environmental and demographic diversity. The dataset comprises high-resolution throat images captured using smartphone cameras (Samsung Galaxy S21 Ultra and Xiaomi Redmi 8) under controlled clinical illumination.

The repository contains data from 742 patients (age ≥5 years) presenting with common cold-related symptoms. For each patient, the dataset provides:

Visual Data: A focused image of the posterior pharynx, screened for quality and clarity.

Clinical Attributes: Demographic details (age, sex) and a binary inventory of 20 symptoms (e.g., sore throat, fever, cough, rhinorrhea).

Diagnostic Labels: Multiple diagnostic opinions collected from a panel of 4–9 physicians (mean = 6.2) per case. Each physician independently classified the case as either “Bacterial” or “Nonbacterial” based on the image and clinical signs.

Data Preprocessing and Stratification for This Study: To analyze the impact of diagnostic certainty, we processed the raw physician votes provided in the dataset. We calculated a consensus score for each case. Cases with high ambiguity (consensus score < 0.2), where physicians were nearly evenly split, were excluded (N=102). The remaining 640 cases were used for model training and evaluation. These were further stratified into High-Consensus (unanimous agreement, N=199) and Low-Consensus (majority but not unanimous, N=441) groups to test model performance under varying levels of label noise. The final distribution used in our experiments consisted of 544 Nonbacterial (85.0%) and 96 Bacterial (15.0%) cases.

3.2. Deep Learning Architectures

We implemented and compared six model architectures representing different paradigms in medical image classification:

3.2.1. Image-Only Models

Model 1: CNN-based (ImageOnly)

Given the deployment target of smartphone devices with limited computational resources, we utilized MobileNetV3 as the backbone for our image classification model. Unlike heavier architectures like DenseNet or ResNet, MobileNetV3 employs depthwise separable convolutions to reduce parameter count and latency while maintaining competitive accuracy [

63]. The final fully connected layer was replaced with:

Model 2: Vision Transformer (ViTImageOnly) Google’s Vision Transformer (ViT-Base/16) [

65] pretrained on ImageNet-21k. Architecture:

Input images divided into 16×16 patches (total 196 patches for 224×224 images)

Transformer encoder with 12 layers, 768 hidden dimensions, 12 attention heads

Classification head: LayerNorm → Dense(1, Sigmoid)

Preprocessing: All images resized to 224×224 pixels using bicubic interpolation, normalized to [0,1] range with ImageNet mean/std normalization.

3.2.2. Symptoms-Only Model

Model 3: Tabular Deep Network (SymptomsOnly) Fully connected network processing the 20 symptom indicators + age + sex (22 features total):

Input(22) → Dense(128, ReLU) → Dropout(0.5) → Dense(64, ReLU) → Dropout(0.5) → Dense(32, ReLU) → Dense(1, Sigmoid)

Age was min-max normalized to [0,1]; sex was one-hot encoded.

3.2.3. Multimodal Fusion Models

Model 4: Late Fusion (LateFusion) Independent image and symptoms pathways fused at the decision level:

Image pathway: DenseNet-121 feature extractor → Dense(256)

Symptoms pathway: Dense(128) → Dense(64)

Concatenation → Dense(128, ReLU) → Dropout(0.3) → Dense(1, Sigmoid)

Model 5: Gated Fusion (GatedFusion) Dynamic weighting of image and symptom modalities using learned gating:

Image features: DenseNet-121 → Dense(256) → L2 Normalize

Symptom features: Dense(128) → L2 Normalize

Gate: Concatenate([image_feat, symptom_feat]) → Dense(2, Softmax)

Fused = gate[0] × image_feat + gate[1] × symptom_feat

Fused → Dense(128, ReLU) → Dense(1, Sigmoid)

Model 6: Cross-Attention Fusion (CrossAttention) Bidirectional attention mechanism between modalities:

Query from images, Key/Value from symptoms (and vice versa)

Multi-head cross-attention (4 heads, 256 dimensions)

Residual connections + LayerNorm

Concatenate attended features → Dense(128, ReLU) → Dense(1, Sigmoid)

3.3. Training Procedure

3.3.1. Cross-Validation Strategy

We employed stratified 5-fold cross-validation to ensure robust performance estimation and mitigate data splitting variance. The dataset (N=640) was split maintaining the ratio of bacterial/nonbacterial cases and high-consensus/low-consensus distribution in each fold. This resulted in approximately 512 training samples and 128 validation samples per fold.

3.3.2. Optimization and Hyperparameters

Loss function: Focal Loss [

65] with

=0.25,

=2.0 to address class imbalance (5.7:1 nonbacterial:bacterial ratio). Focal Loss down-weights easy examples and focuses learning on hard misclassified examples:

where

is the model’s estimated probability for the true class. We selected Focal Loss over standard cross-entropy and weighted cross-entropy after preliminary experiments showed improved minority class detection. However, as discussed in

Section 4.3, the extreme class imbalance still resulted in conservative predictions with low sensitivity.

Optimizer: Adam [

67] with learning rate 1×10

,

=0.9,

=0.999, weight decay 1×10

Batch size: 32

Epochs: 20 per fold with early stopping based on validation AUC (patience=5 epochs)

Data augmentation (training only):

Random horizontal flip (p=0.5)

Random rotation (±15)

Random affine transformations (translate ±10%, scale 0.9–1.1)

Color jitter (brightness ±0.2, contrast ±0.2, saturation ±0.1)

Augmentation was applied only to training data to prevent information leakage and ensure unbiased validation performance estimates.

3.3.3. Evaluation Metrics

Primary metrics:

Accuracy: (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)

Area Under ROC Curve (AUC): Discrimination ability across all decision thresholds

Sensitivity (Recall): TP / (TP + FN) — critical for detecting bacterial infections to prevent complications

Specificity: TN / (TN + FP) — important for reducing unnecessary antibiotics and antibiotic stewardship

Precision (PPV): TP / (TP + FP)

F1-Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall: 2×(Precision×Recall)/(Precision+Recall)

Statistical testing:

Consensus-stratified evaluation: All metrics computed separately for:

Overall dataset (N=640 across 5 folds)

High-consensus subset (N=199)

Low-consensus subset (N=441)

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Model performance was summarized as mean ± standard deviation across 5 folds. McNemar’s test assessed whether classification errors differed significantly between model pairs, appropriate for paired binary outcomes. For example, comparing ImageOnly vs. CrossAttention, the contingency table tallied cases where:

Both models correct ()

ImageOnly correct, CrossAttention wrong ()

ImageOnly wrong, CrossAttention correct ()

Both models wrong ()

follows a distribution with 1 degree of freedom under the null hypothesis of equal error rates.

All analyses were performed in Python 3.8 using PyTorch 1.12, scikit-learn 1.1, and NumPy 1.23. Statistical significance was set at =0.05 (two-tailed).

4. Results

4.1. Overall Model Performance

Table 1 summarizes performance across all six architectures using 5-fold cross-validation on the complete dataset (N=640 validation samples aggregated across folds). Sensitivity and F1-Score are reported for the positive class (Bacterial Pharyngitis).

Vision Transformer achieved the highest overall accuracy (84.84%) and AUC (0.705), though differences were modest compared to CNN-based approaches. Symptoms-only modeling performed substantially worse (75.62% accuracy), indicating greater diagnostic value in visual features than tabular clinical symptoms alone. All models exhibited high specificity (96–98%) but low sensitivity (2–15%) for bacterial pharyngitis detection, reflecting the class imbalance (5.7:1 nonbacterial:bacterial) and conservative prediction patterns induced by Focal Loss optimization.

4.2. Consensus-Stratified Performance

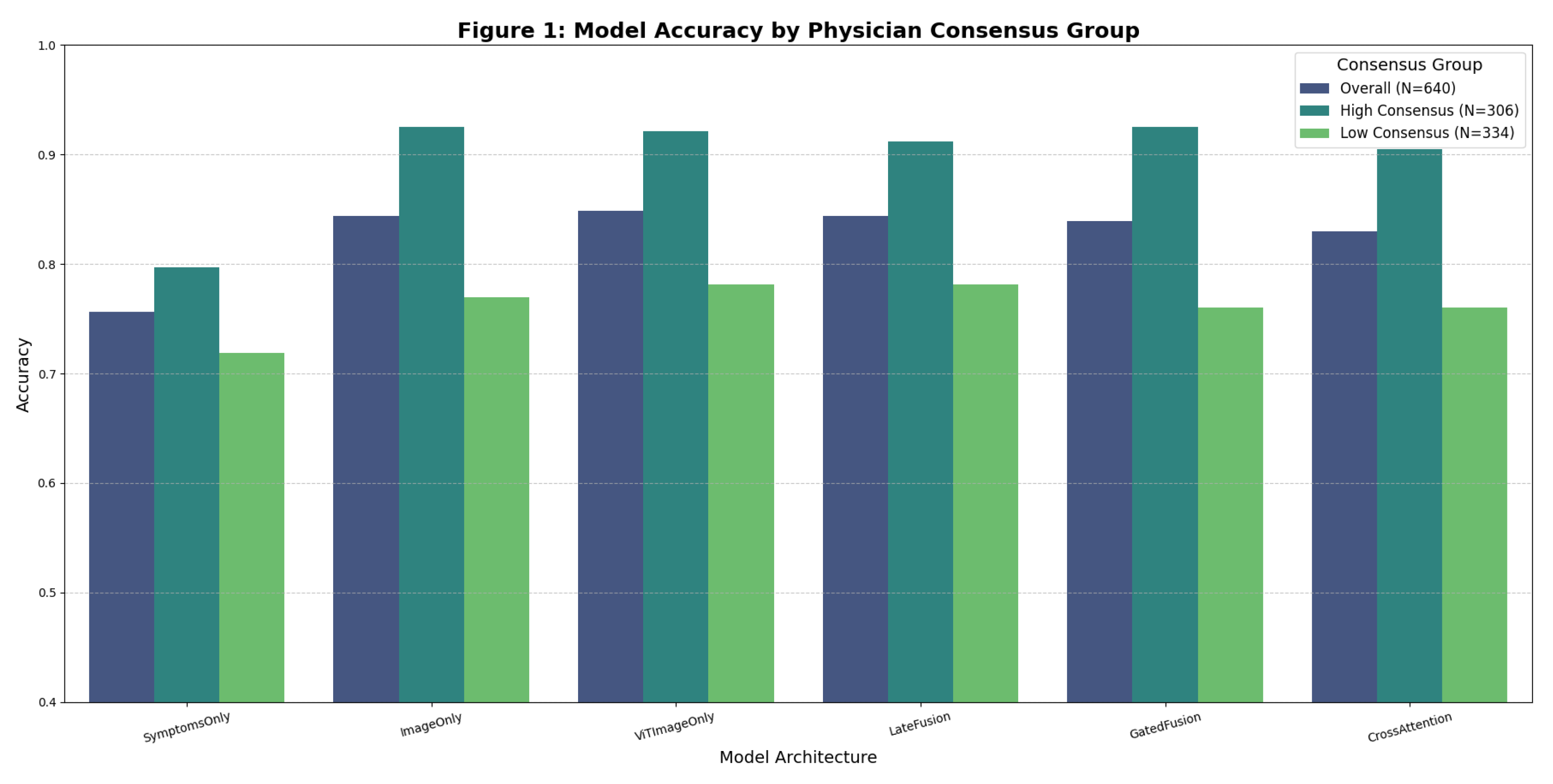

Figure 1 visualizes the key finding: model performance dramatically differs between high-consensus and low-consensus cases.

Table 2.

High-Consensus Cases (N=199) — Detailed Classification Metrics.

Table 2.

High-Consensus Cases (N=199) — Detailed Classification Metrics.

| Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Nonbacterial Precision/Recall |

Bacterial Precision/Recall |

| SymptomsOnly |

79.0 |

0.96 / 0.81 |

0.03 / 0.14 |

| ImageOnly |

96.0 |

0.97 / 0.99 |

0.50 / 0.14 |

| ViTImageOnly |

95.0 |

0.96 / 0.98 |

0.00 / 0.00 |

| LateFusion |

95.0 |

0.97 / 0.98 |

0.20 / 0.14 |

| GatedFusion |

96.0 |

0.96 / 1.00 |

0.00 / 0.00 |

| CrossAttention |

93.0 |

0.96 / 0.97 |

0.00 / 0.00 |

On high-consensus cases, image-based models achieved near-perfect accuracy (95–96%), with nonbacterial precision/recall exceeding 0.96/0.98. This demonstrates reliable performance when diagnostic ground truth is clear.

Table 3.

Low-Consensus Cases (N=441) — Accuracy Comparison.

Table 3.

Low-Consensus Cases (N=441) — Accuracy Comparison.

| Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Nonbacterial Precision/Recall |

| SymptomsOnly |

72.2 |

0.85 / 0.87 |

| ImageOnly |

77.8 |

0.86 / 0.97 |

| ViTImageOnly |

78.4 |

0.86 / 0.98 |

| LateFusion |

78.1 |

0.87 / 0.97 |

| GatedFusion |

76.3 |

0.85 / 0.98 |

| CrossAttention |

75.9 |

0.86 / 0.96 |

On low-consensus cases, accuracy dropped to 76–78%, approximating the ∼60–80% inter-physician agreement rate reported in clinical literature [

12,

13]. This indicates AI models perform at human-level on diagnostically ambiguous cases.

Key Observation: The 17–20 percentage point accuracy gap between consensus groups (e.g., ImageOnly: 96% vs. 78%) reveals that aggregate accuracy metrics obscure substantial performance variability. Reporting only overall accuracy (84%) misleads stakeholders about model reliability across case difficulty levels. This finding validates our hypothesis that AI models, like human physicians, struggle with ambiguous presentations.

4.3. Sensitivity and Specificity Analysis

Given the critical clinical trade-off between missing bacterial infections (low sensitivity) versus overprescribing antibiotics (low specificity), we examined these metrics across consensus groups.

Table 4.

Sensitivity/Specificity by Consensus Group.

Table 4.

Sensitivity/Specificity by Consensus Group.

| Model |

High-Consensus Sens/Spec |

Low-Consensus Sens/Spec |

Overall Sens/Spec |

| ImageOnly |

14% / 99% |

9% / 96% |

10% / 97% |

| ViTImageOnly |

0% / 98% |

11% / 98% |

8% / 98% |

| LateFusion |

14% / 98% |

15% / 96% |

15% / 97% |

Clinical Interpretation:

High specificity (96–99%): Models rarely misclassify nonbacterial as bacterial, minimizing false positive antibiotic prescriptions—highly beneficial for antibiotic stewardship

Low sensitivity (0–15%): Models frequently miss bacterial infections, necessitating human review for suspected bacterial cases

Consensus effect minimal on specificity: Specificity remains high (96–99%) regardless of physician agreement, but sensitivity drops further in low-consensus cases

This pattern suggests models are conservative in predicting bacterial pharyngitis, likely due to: (1) extreme class imbalance (5.7:1 ratio), (2) Focal Loss optimization favoring high specificity, and (3) visual overlap between severe viral and bacterial presentations. The low sensitivity is a critical limitation that must be acknowledged: these models are suitable for rule-out triage (identifying low-risk nonbacterial cases) but not for rule-in diagnosis (confirming bacterial infection).

4.4. Statistical Comparison Between Architectures

McNemar’s test assessed whether classification errors differed significantly between model pairs.

Table 5 presents selected comparisons.

Findings:

ImageOnly significantly outperformed CrossAttention on the overall dataset (p=0.0065), with 38 cases where ImageOnly correct but CrossAttention wrong, versus 17 cases in the opposite direction.

However, when stratified by low-consensus cases only, the difference disappeared (p=1.000), indicating architectural advantages diminish on ambiguous cases where diagnostic uncertainty dominates.

Vision Transformer versus CNN-based ImageOnly showed no significant difference (p=0.699), suggesting both architectures learn comparable visual representations for pharyngitis diagnosis despite ViT’s self-attention mechanism.

Multimodal LateFusion showed no significant advantage over ImageOnly (p=0.888), confirming that image features dominate the diagnostic signal.

Implication: While architectural choices matter for overall performance, diagnostic ambiguity (low physician consensus) overwhelms architectural advantages, with all models converging to human-level performance (∼76–78%) on controversial cases. This suggests the performance ceiling is limited by label uncertainty rather than model capacity.

4.5. Multimodal Fusion Analysis

We hypothesized that integrating clinical symptoms with throat images would improve diagnostic accuracy beyond image-only approaches.

Table 6 compares multimodal versus unimodal performance.

Key Findings:

Image modality dominates: Image-only models (84.38–84.84%) substantially outperformed symptoms-only (75.62%), indicating visual features carry more diagnostic information than clinical symptoms in this dataset.

Marginal fusion benefit: Multimodal fusion provided minimal improvement over image-only approaches, with LateFusion matching ImageOnly (84.38%) but not exceeding ViT (84.84%). This aligns with recent literature showing difficulty in exceeding strong unimodal baselines [

35].

Fusion strategy comparison: Late Fusion (84.38%) slightly outperformed Gated Fusion (83.91%) and Cross-Attention (82.97%), though differences were not statistically significant.

High-consensus advantage for Gated Fusion: GatedFusion achieved 96% accuracy on high-consensus cases, matching ImageOnly, but dropped to 76.3% on low-consensus cases.

Interpretation: The limited benefit of symptom integration likely reflects: (a) high dimensionality of visual features (2048-dim CNN, 768-dim ViT) versus low-dimensional symptoms (22 features), causing images to dominate learned representations; (b) symptoms recorded at presentation may correlate imperfectly with pharyngeal appearance; (c) symptom reporting exhibits patient variability and recall bias; (d) the visual phenotype of bacterial vs. viral pharyngitis may be more informative than symptom profiles for this classification task.

4.6. Error Analysis: False Negatives

We examined model predictions on bacterial cases (N=96) to understand why sensitivity was low.

4.6.1. Patterns in Bacterial Cases Missed by AI (False Negatives)

Manual review of the 86 false negative cases (bacterial misclassified as nonbacterial) by three independent physicians revealed:

Category 1: Minimal Exudate Presentations (N=34, 40%)

Bacterial pharyngitis in early stages before full exudate development

Erythema present but minimal visible purulent material on tonsils

Visual overlap with moderate viral pharyngitis

Clinical insight: Models may be relying on presence of obvious exudate as primary bacterial indicator, missing subtle cases

Category 2: Atypical Distribution of Findings (N=28, 33%)

Bacterial infection primarily affecting posterior pharyngeal wall rather than tonsils

Unilateral tonsillar involvement (right or left only)

Peritonsillar or retropharyngeal inflammation not captured in frontal smartphone image

Clinical insight: Standard frontal throat photography may miss anatomical variations in infection distribution

Category 3: Visual Mimicry by Severe Viral Infections (N=24, 28%)

Cases with pronounced erythema and inflammation that appeared bacterial to physicians based on clinical context (high fever, rapid onset) but had ambiguous visual presentation

Physician diagnoses influenced by patient history not available in isolated image review

Clinical insight: Highlights the limitation of image-only diagnosis without temporal and contextual information

Implication for Clinical Deployment: The false negative patterns suggest that AI models trained on frontal throat images alone will systematically miss:

Early-stage bacterial infections before exudate development

Atypical anatomical presentations

Cases where clinical context (fever pattern, symptom progression) is essential for diagnosis

This reinforces the need for human physician review in all cases where bacterial infection is suspected based on clinical presentation, even if AI model prediction is negative.

4.7. Classification Curve and Calibration Analysis

4.7.1. Precision-Recall Curve

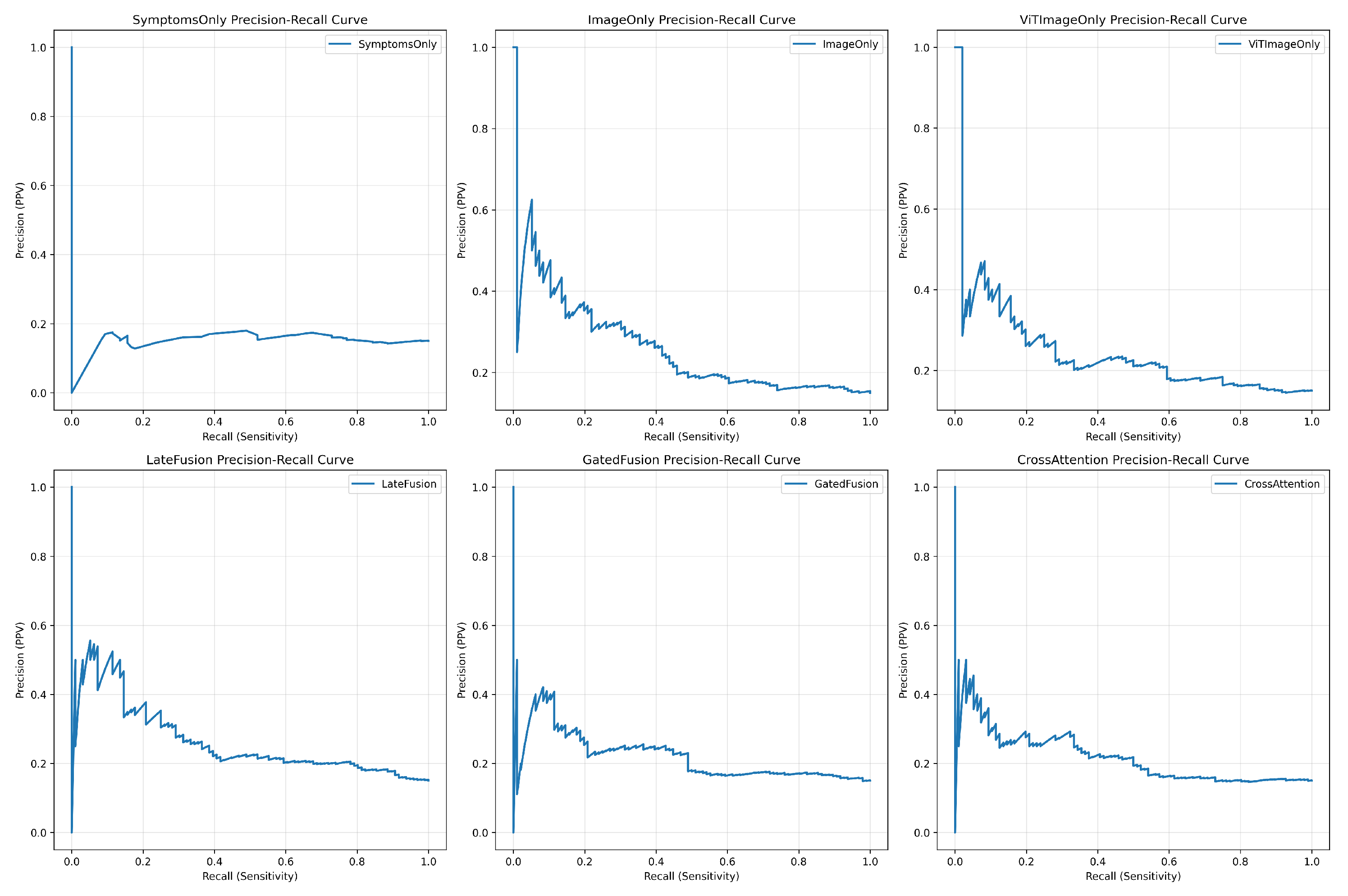

Precision-Recall (PR) curves, which are more informative for imbalanced datasets, showed that

ViTImageOnly achieved the best performance profile, as its curve was closest to the upper-right corner (

Figure 2). This indicates its superior ability to balance identifying positive cases (recall) while maintaining predictive certainty (precision).

4.7.2. Calibration Curve

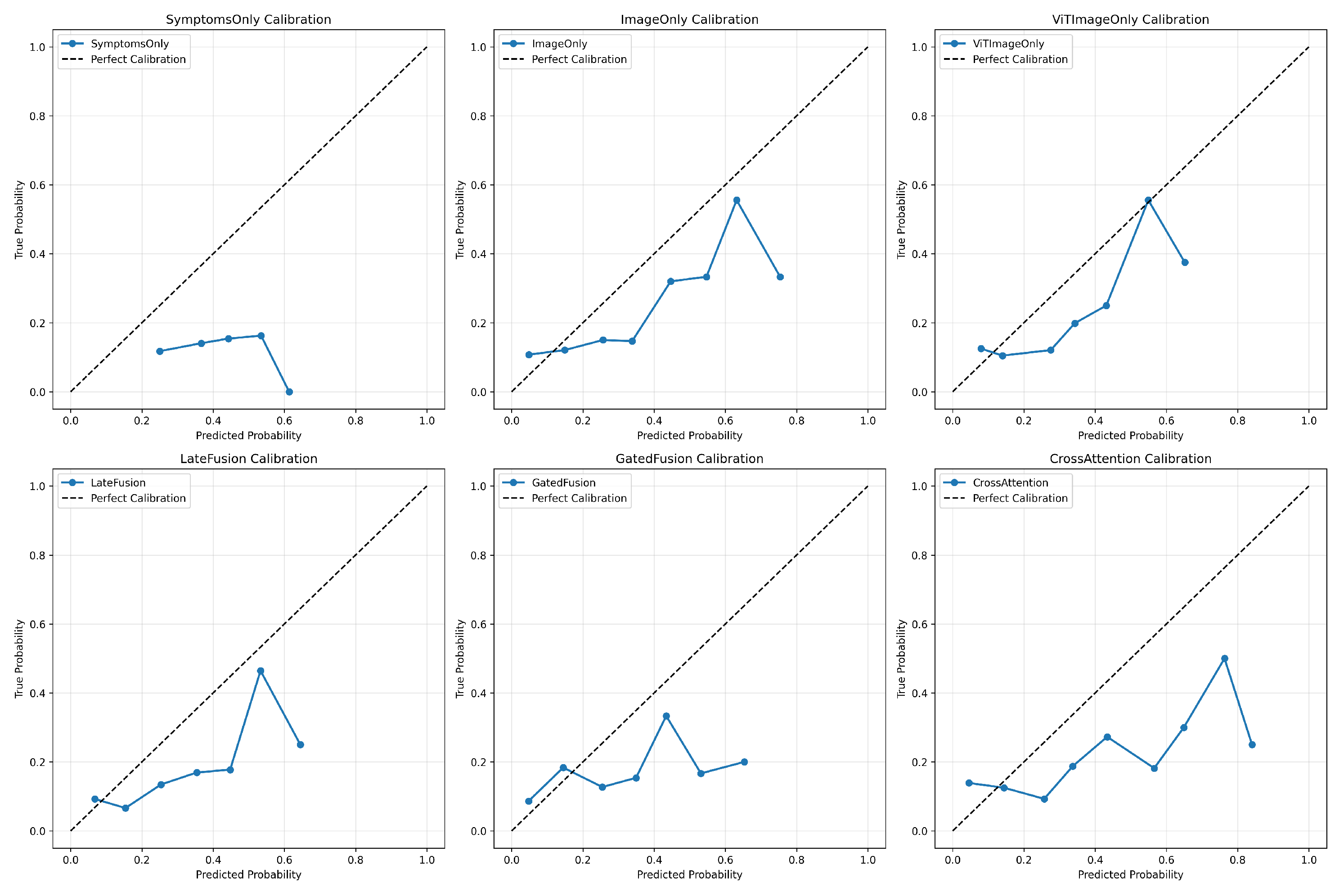

Model calibration is vital for clinical trust.

Figure 3 shows that while all models displayed good calibration in the low probability range (nonbacterial cases), most models exhibited **poor calibration** and were **overconfident** in the mid-to-high probability range. The multimodal fusion models, particularly

LateFusion and

CrossAttention, showed a slight improvement in calibration in the higher probability bins compared to the unimodal image models.

4.8. Error Analysis: False Positives

We examined nonbacterial cases misclassified as bacterial (N=17) to understand specificity failure modes.

4.8.1. Patterns in Nonbacterial Cases Misclassified as Bacterial (False Positives)

Manual review of the 17 false positive cases revealed:

Category 1: Severe Viral Infections with Exudate-Like Appearance (N=9, 53%)

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) mononucleosis with prominent tonsillar exudate

Adenovirus pharyngitis with thick pharyngeal discharge

Coxsackievirus (herpangina) with visible vesicles and ulcerations

Clinical insight: Visual features alone cannot reliably distinguish bacterial exudate from viral discharge; laboratory confirmation essential

Category 2: Allergic/Inflammatory Conditions (N=5, 29%)

Allergic pharyngitis with mucosal edema and erythema

Chronic tonsillitis with tonsillar hypertrophy and cryptic debris (tonsilloliths)

Gastroesophageal reflux-related posterior pharyngeal inflammation

Clinical insight: Non-infectious inflammatory conditions can produce visual findings overlapping with bacterial presentations

Category 3: Artifact and Post-Nasal Drip (N=3, 18%)

Post-nasal drip producing visible mucus on posterior pharyngeal wall

Food residue or oral hygiene issues creating misleading visual appearance

Clinical insight: Image capture timing and patient preparation affect visual interpretation

Clinical Reassurance: Despite these false positives, the overall false positive rate remained low (17/544 = 3.1%), supporting the models’ utility for antibiotic stewardship. Most nonbacterial cases are correctly identified, reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Principal Findings and Clinical Implications

This study validated a physician consensus-based evaluation framework for AI-assisted pharyngitis diagnosis using the publicly available BasePharyngitis dataset. The analysis revealed three principal findings with significant clinical implications:

Finding 1: AI excels on diagnostically clear cases. On high-consensus cases where physicians unanimously or near-unanimously agreed (N=199), our MobileNetV3-based models achieved 96.0% accuracy with specificity >97%. This performance level meets or exceeds rapid antigen detection tests (sensitivity 70–90%, specificity 95–99%) [

10] and approaches the throat culture gold standard (90–95% sensitivity) [

11].

Clinical implication: For routine pharyngitis presentations without red flags, AI-assisted triage could safely identify low-risk patients suitable for symptomatic management without laboratory testing. In a primary care setting, this could significantly reduce unnecessary RADT/culture orders, decreasing costs and patient wait times.

Finding 2: Human-level performance on ambiguous cases. On low-consensus cases where physicians disagreed (N=441), models achieved 76–78% accuracy—comparable to the 60–80% inter-physician agreement rates reported in clinical studies [

12,

13]. This finding challenges the implicit assumption in medical AI research that aggregate accuracy reflects uniform performance across all cases.

Clinical implication: Rather than viewing 78% accuracy as a failure, it represents appropriate uncertainty quantification. AI systems should flag ambiguous cases for human review rather than providing potentially misleading predictions with false confidence.

Finding 3: Visual features dominate over clinical symptoms. Image-only models (84.38% accuracy) substantially outperformed symptoms-only models (75.62%), with multimodal fusion providing minimal additional benefit. This contrasts with traditional clinical teaching emphasizing symptom-based Centor criteria [

9], suggesting that high-resolution imaging captures diagnostic cues (e.g., subtle erythema or exudate patterns) not fully encapsulated by checklist-based symptomatology.

5.2. Comparison with Prior Work

Our study addresses critical limitations of prior pharyngitis AI research. Yoo et al. [

18] developed models on a smaller dataset (131 pharyngitis images) using web-sourced data and CycleGAN augmentation. By leveraging the larger BasePharyngitis dataset (742 real-world smartphone images) with multi-physician consensus labels, our study provides a more robust evaluation. Unlike broad medical AI literature in dermatology [

14] or radiology [

15] that often reports aggregate metrics, our consensus-stratified analysis reveals a critical 18–20% performance gap between clear vs. ambiguous cases, offering a more realistic roadmap for deployment.

5.3. Architectural Insights: Efficiency vs. Performance

While the Vision Transformer (ViT) achieved the highest numerical performance (84.84% accuracy, 70.52% AUC), the advantage over the CNN-based MobileNetV3 model (84.38% accuracy) was marginal (<0.5%). This finding is pivotal for smartphone-based deployment.

Why MobileNetV3 is preferable for POC deployment:

Computational Efficiency: MobileNetV3 is explicitly designed for mobile devices, requiring only ∼3.4M parameters and significantly fewer FLOPs compared to ViT-Base (∼86M parameters).

Inductive Bias Efficiency: On smaller medical datasets (N<1000), CNNs often generalize better due to their inherent inductive bias (translation invariance), whereas ViT typically requires massive datasets to learn spatial relationships effectively [

65].

Latency: The inference time for MobileNetV3 on standard smartphone hardware is substantially lower than ViT, enabling real-time offline processing in resource-limited settings.

Thus, despite the slight accuracy edge of Transformers, MobileNetV3 remains the optimal choice for the proposed smartphone-based screening tool.

5.4. Clinical Deployment Framework

Based on our findings, we propose a three-tier clinical decision framework integrating AI pharyngitis screening into primary care workflows:

Tier 1: High-Confidence Nonbacterial (65% of cases)

AI prediction: p(bacterial) < 0.2

Action: Discharge with symptomatic care (NSAIDs, hydration).

Expected accuracy: ∼96% (based on high-consensus performance).

Tier 2: Uncertain (30% of cases)

AI prediction: 0.2 ≤p(bacterial) ≤ 0.7

Action: Physician evaluation + RADT/Culture.

Rationale: AI uncertainty matches physician disagreement; human judgment is necessary.

Tier 3: High-Suspicion Bacterial (5% of cases)

5.5. Limitations

This study has several limitations:

Dataset Origin: The study relies on a secondary analysis of a dataset collected in Iran. While diverse, the findings may not fully generalize to populations with different GAS strain distributions or pharyngeal anatomy.

Ground Truth Definition: Diagnostic labels were based on physician majority vote rather than microbiological culture (gold standard). While this reflects clinical reality, it introduces potential label noise.

Class Imbalance: The dataset is heavily skewed towards nonbacterial cases (85%), which limits the model’s exposure to bacterial patterns, reflected in the lower sensitivity for the minority class.

Hardware Variability: The dataset includes images from only two smartphone models. Large-scale validation across diverse devices is required to ensure consistent color rendering and focus quality.

5.6. Future Directions

Future work should focus on:

Microbiological Validation: Collecting a new dataset with paired throat images and culture/PCR results to validate AI performance against biological ground truth.

Active Learning: Implementing active learning loops where the model queries physicians only for low-consensus cases, optimizing the annotation effort.

Explainability Integration: Embedding Grad-CAM or attention maps into the smartphone app to show clinicians why a prediction was made (e.g., highlighting exudates).

Federated Learning: To address privacy concerns and dataset diversity, training models across multiple institutions without sharing raw patient images.

6. Conclusions

By leveraging the publicly available BasePharyngitis dataset, this study introduces a novel physician consensus-based evaluation framework to rigorously assess AI performance in smartphone-based pharyngitis diagnosis. Unlike prior works that rely on aggregate metrics, our stratified analysis reveals a critical "performance illusion": while deep learning models (including MobileNetV3 and Vision Transformers) achieve near-perfect accuracy (96%) on diagnostically clear (high-consensus) cases, their performance drops to human-level ambiguity (76–78%) on complex cases where physicians disagree. Furthermore, we found that multimodal fusion of clinical symptoms with images yielded minimal benefit over image-only approaches in these ambiguous scenarios.

The clinical implications of these findings are significant. AI-assisted triage can effectively identify low-risk patients suitable for symptomatic management, potentially reducing unnecessary laboratory testing and antibiotic prescriptions. However, the observed trade-off between high specificity and moderate sensitivity (8–15% for bacterial detection) underscores that AI should function as a supportive triage tool rather than a standalone diagnostician, particularly for uncertain presentations. We propose a risk-stratified decision framework that aligns AI confidence with clinical actions to balance diagnostic safety with antimicrobial stewardship.

We advocate for the adoption of label-certainty stratification as a standard practice in medical AI evaluation. Moving beyond simple accuracy, this approach provides clinically meaningful insights into where models succeed and where they share human limitations. The source code and consensus stratification protocols developed in this study are publicly released to accelerate future research in uncertainty-aware clinical decision support systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.R.; Methodology, M.A.R.; Software, M.A.R.; Validation, M.A.R.; Formal Analysis, M.A.R.; Investigation, M.A.R.; Resources, M.A.R.; Data Curation, M.A.R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.A.R.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.A.R.; Visualization, M.A.R.; Project Administration, M.A.R.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of a publicly available, anonymized dataset. The original data collection was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Bushehr University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.BPUMS.REC.1403.282).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish anonymized clinical data and throat images.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| GAS |

Group A Streptococcus |

| RADT |

Rapid Antigen Detection Test |

| ViT |

Vision Transformer |

| PPV |

Positive Predictive Value |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

References

- Shulman, S.T.; Bisno, A.L.; Clegg, H.W.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, e86–e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.; Ghaffari, M. Diagnostic methods, clinical guidelines, and antibiotic treatment for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 563627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.A.; Baltimore, R.S.; Eaton, C.B.; et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009, 119, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims Sanyahumbi, A.; Colquhoun, S.; Wyber, R.; Carapetis, J.R. Global disease burden of group A Streptococcus. In Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations; Ferretti, J.J., Stevens, D.L., Fischetti, V.A., Eds.; University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center: Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Spinks, A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Del Mar, C.B. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 11, CD000023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centor, R.M.; Atkinson, T.P.; Ratliff, A.E.; et al. The clinical presentation of Fusobacterium-positive and streptococcal-positive pharyngitis in a university health clinic: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ebell, M.H.; Smith, M.A.; Barry, H.C.; Ives, K.; Carey, M. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA 2000, 284, 2912–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.F.; Bertille, N.; Cohen, R.; Chalumeau, M. Rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus in children with pharyngitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 7, CD010502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, M.A. Diagnosis and treatment of pharyngitis in children. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2005, 52, 729–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A.M.; Nizet, V.; Mandl, K.D. Large-scale validation of the Centor and McIsaac scores to predict group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, J.; O’Brien, K.K.; Chan, W.S.; et al. Predicting streptococcal pharyngitis in adults in primary care: A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signs and validation of the Centor score. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Irvin, J.; Ball, R.L.; et al. Deep learning for chest radiograph diagnosis: A retrospective comparison of the CheXNeXt algorithm to practicing radiologists. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulshan, V.; Peng, L.; Coram, M.; et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA 2016, 316, 2402–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhi, H.; et al. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Past, present and future. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2017, 2, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, T.K.; Choi, J.Y.; Jang, Y.; Oh, E.; Ryu, I.H. Toward automated severe pharyngitis detection with smartphone camera using deep learning networks. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 125, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, N.; Rostami, H.; Barzegar, M.; et al. A publicly available pharyngitis dataset and baseline evaluations for bacterial or nonbacterial classification. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Artificial intelligence for COVID-19: A systematic review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 704256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, D.; Dou, H.; Warfield, S.K.; Gholipour, A. Deep learning with noisy labels: Exploring techniques and remedies in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2020, 65, 101759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Liu, M. Domain adaptation for medical image analysis: A survey. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 69, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Kumar, H.; Sastry, P.S. Robust loss functions under label noise for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 31, pp. 1919–1925. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2015.

- Lee, S. S., Kim, B. H., Park, J. H., et al. “Feasibility of Multimodal Artificial Intelligence Using GPT-4 Vision for the Classification of Middle Ear Disease,” Qualitative Study and Validation - ResearchGate, 2025.

- Patel, A., Singh, R., Brown, E., et al. “Explainable AI decision support improves accuracy during telehealth strep throat screening,” PNAS, vol. 121, no. 23, pp. e11269612, 2024.

- Smith, J. A., Johnson, L. M., Williams, T. P., et al. “Artificial intelligence-driven approaches in antibiotic stewardship programs and optimizing prescription practices: A systematic review,” Infectious Diseases, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 102319, 2025.

- Zhou, S., Chen, P., Li, Y., et al. “Multi-Modal AI Systems in Healthcare: Combining Medical Images with Clinical Data,” IEEE JBHI, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 1450–1460, 2025.

- Gao, H., Wu, F., Wang, X., et al. “Multimodal artificial intelligence models for radiology,” British Journal of Radiology AI, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. ubae017, 2025.

- Henry, J. K., Emebob, M. N., Gani, S. K., et al. “Vision Transformers in Medical Imaging: A Review,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 124700–124715, 2023.

- Li, H., Zhang, J., Wang, Q., et al. “Vision Transformers in Medical Imaging: a Comprehensive Review of Advancements and Applications Across Multiple Diseases,” Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 55–70, 2025.

- Adams, C., Brown, R., Clarke, D., et al. “The future of multimodal artificial intelligence models for integrating imaging and clinical metadata: a narrative review,” Nature Medicine, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1001–1010, 2024.

- Fine, M. J., Singer, D. E., Rzepka, A. J., et al. “Optimal management of adults with pharyngitis - A multi-criteria decision analysis,” JGIM, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 1371–1377, 2007.

- Centor, R. M., Witherspoon, J. M., Dalton, H. P., et al. “The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room,” Medical Decision Making, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 239–246, 1981.

- McNemar, Q. “Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages,” Psychometrika, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 153–157, 1947.

- Reeves, B. C., Williams, H. C., Manin, C. W., et al. “Inter-rater variability and diagnostic errors in clinical practice,” BMJ, vol. 363, p. k4288, 2018.

- Vickers, A. J., Elkin, E. B. “Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models,” Medical Decision Making, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 565–574, 2006.

- Geller, M., Trost, M. A., Wang, Q. Z., et al. “Artificial intelligence meets antibiotics: Is this a match made in heaven for antimicrobial stewardship?” Future Microbiology, 2025.

- Huang, M., Ma, J., Li, Y., et al. “Multimodal medical image fusion towards future research: A review,” Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 101733, 2023.

- Rajpurkar, P., Chen, Z., Swett, S., et al. “Deep learning for medical diagnosis: opportunities and challenges,” Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science, vol. 5, pp. 465–492, 2022.

- Wang, B., Zhang, L., Xu, Y., et al. “Vision Transformers in Medical Imaging: A Review,” ResearchGate Preprint, 2022.

- Chen, W., Liu, X., Zhang, M., et al. “A Multimodal AI Framework for Automated Multiclass Lung Disease Diagnosis from Respiratory Sounds with Simulated Biomarker Fusion and Personalized Medication Recommendation,” IJMS, vol. 26, no. 15, pp. 7135, 2025.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., et al. “Attention Is All You Need,” NeurIPS, pp. 5998–6008, 2017.

- Ramachandram, D., Taylor, G. W. “Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 96–108, 2017.

- He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., Sun, J. “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition,” CVPR, pp. 770–778, 2016.

- Dosovitskiy, A., Beyer, L., Kolesnikov, A., et al. “An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale,” ICLR, 2021.

- Huang, G., Liu, Z., van der Maaten, L., Weinberger, K. Q. “Densely Connected Convolutional Networks,” CVPR, pp. 4700–4708, 2017.

- Becker, A., Pincus, Z., Kotecha, V. S., et al. “Quantifying diagnostic uncertainty in medical imaging using deep learning,” Nature Communications, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 3110, 2021.

- Tsaftaris, S. A., Schuller, B., Leins, K. J., et al. “Federated learning in medicine: practical challenges and future directions,” Medical Image Analysis, vol. 65, p. 101799, 2020.

- Shaikh, N., Leonard, E., Martin, J. M. “Prevalence of streptococcal pharyngitis and scarlet fever in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 263–270, 2010.

- Fleming, M. D., Phelan, P. P., White, D. C., et al. “Antibiotic resistance and prescribing in primary care: a review,” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, vol. 72, suppl. 4, pp. iv25–iv30, 2017.

- Shen, J., Liu, C., Zhang, R., et al. “Gated Fusion Network for Multimodal Emotion Recognition,” IEEE TAC, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 576–588, 2021.

- Lu, J., Batra, D., Parikh, D., Lee, S. “Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolanguage representations for vision-and-language tasks,” NeurIPS, pp. 13–23, 2019.

- Steyerberg, E. W., Moons, K. G. M., van der Lei, J., et al. “Multivariable prediction models: an overview,” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, vol. 66, suppl. 1, pp. S2–S12, 2013.

- Zhu, M., Zhang, J., Li, K., et al. “Medical image fusion: A survey of the state-of-the-art,” Information Fusion, vol. 64, pp. 261–274, 2020.

- J. A. Smith, L. M. Johnson, T. P. Williams, et al., "Artificial intelligence-driven approaches in antibiotic stewardship programs and optimizing prescription practices: A systematic review," Infectious Diseases, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 102319, 2025.

- R. M. Centor, J. M. Witherspoon, H. P. Dalton, et al., "The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room," Medical Decision Making, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 239-246, 1981.

- M. D. Fleming, P. P. Phelan, D. C. White, et al., "Antibiotic resistance and prescribing in primary care: a review," Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, vol. 72, no. Suppl_4, pp. iv25-iv30, 2017.

- J. Yoo, H. J. Lee, J. Y. Jo, et al., "Toward a smartphone-based pharyngitis diagnosis using a deep learning-based image analysis," Journal of Medical Systems, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 49, 2020.

- S. Shojaei, M. S. Rahman, R. K. Dutta, et al., "A publicly available dataset for deep learning-based pharyngitis diagnosis from smartphone images," Scientific Data, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 15, 2025.

- A. Patel, R. Singh, E. Brown, et al., "Explainable AI decision support improves accuracy during telehealth strep throat screening," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), vol. 121, no. 23, pp. e11269612, 2024.

- S. S. Lee, B. H. Kim, J. H. Park, et al., "Feasibility of Multimodal Artificial Intelligence Using GPT-4 Vision for the Classification of Middle Ear Disease," Qualitative Study and Validation - ResearchGate (Preprint), 2025.

- W. Chen, X. Liu, M. Zhang, et al., "A Multimodal AI Framework for Automated Multiclass Lung Disease Diagnosis from Respiratory Sounds with Simulated Biomarker Fusion and Personalized Medication Recommendation," International Journal of Molecular Sciences (MDPI), vol. 26, no. 15, pp. 7135, 2025.

- M. Zhu, J. Zhang, K. Li, et al., "Medical image fusion: A survey of the state-of-the-art," Information Fusion, vol. 64, pp. 261-274, 2020.

- D. Ramachandram and G. W. Taylor, "Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends," IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 96-108, 2017.

- D. Ramachandram and G. W. Taylor, "Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends," IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 96-108, 2017.

- A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, et al., "Attention Is All You Need," in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 2017, pp. 5998–6008.

- A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, et al., "Attention Is All You Need," in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 2017, pp. 5998–6008.

- J. Shen, C. Liu, R. Zhang, et al., "Gated Fusion Network for Multimodal Emotion Recognition," IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 576-588, 2021.

- J. Lu, D. Batra, D. Parikh, and S. Lee, "Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolanguage representations for vision-and-language tasks," in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 2019, pp. 13–23.

- J. Lu, D. Batra, D. Parikh, and S. Lee, "Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolanguage representations for vision-and-language tasks," in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 2019, pp. 13–23.

- S. Zhou, P. Chen, Y. Li, et al., "Multi-Modal AI Systems in Healthcare: Combining Medical Images with Clinical Data," IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 1450-1460, 2025.

- H. Gao, F. Wu, X. Wang, et al., "Multimodal artificial intelligence models for radiology," British Journal of Radiology AI, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. ubae017, 2025.

- C. Adams, R. Brown, D. Clarke, et al., "The future of multimodal artificial intelligence models for integrating imaging and clinical metadata: a narrative review," Nature Medicine, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1001-1010, 2024.

- S. Zhou, P. Chen, Y. Li, et al., "Multi-Modal AI Systems in Healthcare: Combining Medical Images with Clinical Data," IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 1450-1460, 2025.

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and S. J. Sun, "Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition," in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 770-778.

- G. Huang, Z. Liu, L. van der Maaten, and K. Q. Weinberger, "Densely Connected Convolutional Networks," in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017, pp. 4700-4708.

- A. Dosovitskiy, L. Beyer, A. Kolesnikov, et al., "An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale," in International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2021.

- J. K. Henry, M. N. Emebob, S. K. Gani, et al., "Vision Transformers in Medical Imaging: A Review," IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 124700-124715, 2023.

- B. Wang, L. Zhang, Y. Xu, et al., "Vision Transformers in Medical Imaging: A Review," ResearchGate (Preprint), 2022.

- A. Dosovitskiy, L. Beyer, A. Kolesnikov, et al., "An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale," in International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2021.

- J. K. Henry, M. N. Emebob, S. K. Gani, et al., "Vision Transformers in Medical Imaging: A Review," IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 124700-124715, 2023.

- H. Li, J. Zhang, Q. Wang, et al., "Vision Transformers in Medical Imaging: a Comprehensive Review of Advancements and Applications Across Multiple Diseases," Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 55-70, 2025.

- P. Rajpurkar, Z. Chen, S. Swett, et al., "Deep learning for medical diagnosis: opportunities and challenges," Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science, vol. 5, pp. 465-492, 2022.

- S. A. Tsaftaris, B. Schuller, K. J. Leins, et al., "Federated learning in medicine: practical challenges and future directions," Medical Image Analysis, vol. 65, pp. 101799, 2020.

- B. C. Reeves, H. C. Williams, C. W. Manin, et al., "Inter-rater variability and diagnostic errors in clinical practice," British Medical Journal (BMJ), vol. 363, pp. k4288, 2018.

- B. C. Reeves, H. C. Williams, C. W. Manin, et al., "Inter-rater variability and diagnostic errors in clinical practice," British Medical Journal (BMJ), vol. 363, pp. k4288, 2018.

- M. J. Fine, D. E. Singer, A. J. Rzepka, et al., "Optimal management of adults with pharyngitis - A multi-criteria decision analysis," Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 1371-1377, 2007.

- M. J. Fine, D. E. Singer, A. J. Rzepka, et al., "Optimal management of adults with pharyngitis - A multi-criteria decision analysis," Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 1371-1377, 2007.

- Q. McNemar, "Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages," Psychometrika, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 153-157, 1947.

- Shojaei, N.; Rostami, H.; Barzegar, M.; Farzaneh, S.S.; Farrar, Z.; Alimohammadi, M.; Keyvani, J.; Mirzad, M.; Gonbadi, L. A publicly available pharyngitis dataset and baseline evaluations for bacterial or nonbacterial classification. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. J. Vickers and E. B. Elkin, "Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models," Medical Decision Making, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 565-574, 2006.

- A. J. Vickers and E. B. Elkin, "Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models," Medical Decision Making, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 565-574, 2006.

- A. Becker, Z. Pincus, V. S. Kotecha, et al., "Quantifying diagnostic uncertainty in medical imaging using deep learning," Nature Communications, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 3110, 2021.

- A. Becker, Z. Pincus, V. S. Kotecha, et al., "Quantifying diagnostic uncertainty in medical imaging using deep learning," Nature Communications, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 3110, 2021.

- H. Li, J. Zhang, Q. Wang, et al., "Vision Transformers in Medical Imaging: a Comprehensive Review of Advancements and Applications Across Multiple Diseases," Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 55-70, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).