Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Chronic lung infection with Pseudomonadota (PCH) in patients with cystic fibrosis (pwCF) is difficult to eradicate. CFTR modulators have a potential role in the prevention of airway infections, but their ability to eradicate chronic infection remains to be investigated. The aim of our study was to evaluate the impact of combination (antibacterial (AT) and modulator (MT)) therapy on the lung microbiome composition (LMC) in the pwCF cohort. The microbiome of sputum samples longitudinally collected from Russian adult pwCF chronically infected with Pseudomonadota CF pathogens (PCH) was analyzed. MT resulted in a trend of bacterial load reduction. LMC did not undergo significant changes in PCH pwCF receiving MT for less than three years. Two-component MT resulted in a temporary decrease in the proportion of the CF pathogen only when combined with a course of AT. Three-component MT has been successful in inducing favorable microbiome changes (with abundance and diversity of anaerobic taxa) over a period of more than 3 years, but not for all cases of Burkholderiales infection. Respiratory system damaged by bronchiectasis is susceptible to new infections, so patient management requires constant monitoring of the LMC and replenishment of the therapeutic landscape with both new modulators and new antibacterial drugs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

DNA Extraction

Quantitative PCR

Identification of Some Typical CF Pathogens

Microbiome Sequencing

Microbiome Data Analysis

3. Results

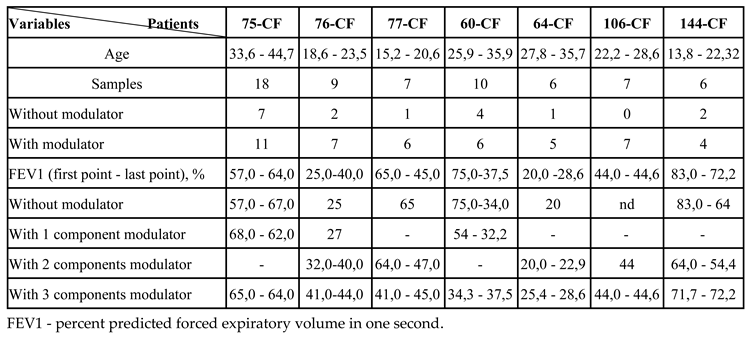

3.1. Patients in the Analysis

3.2. Primary Characteristics of Sputum Samples

3.2.1. 16S rDNA Gene Concentration

3.2.2. Typical CF Pathogens in Sputum Samples

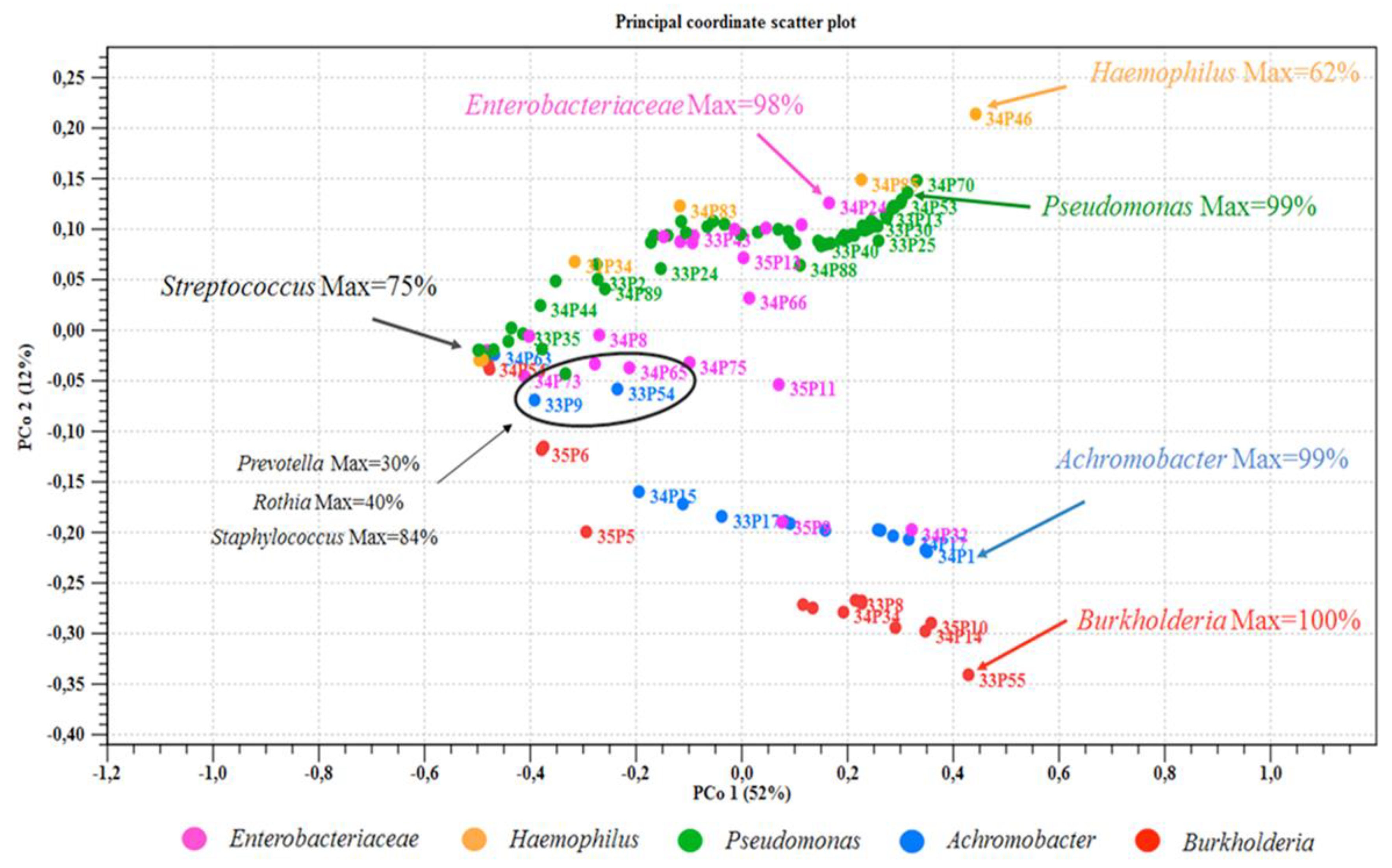

3.3. Microbiome Analysis

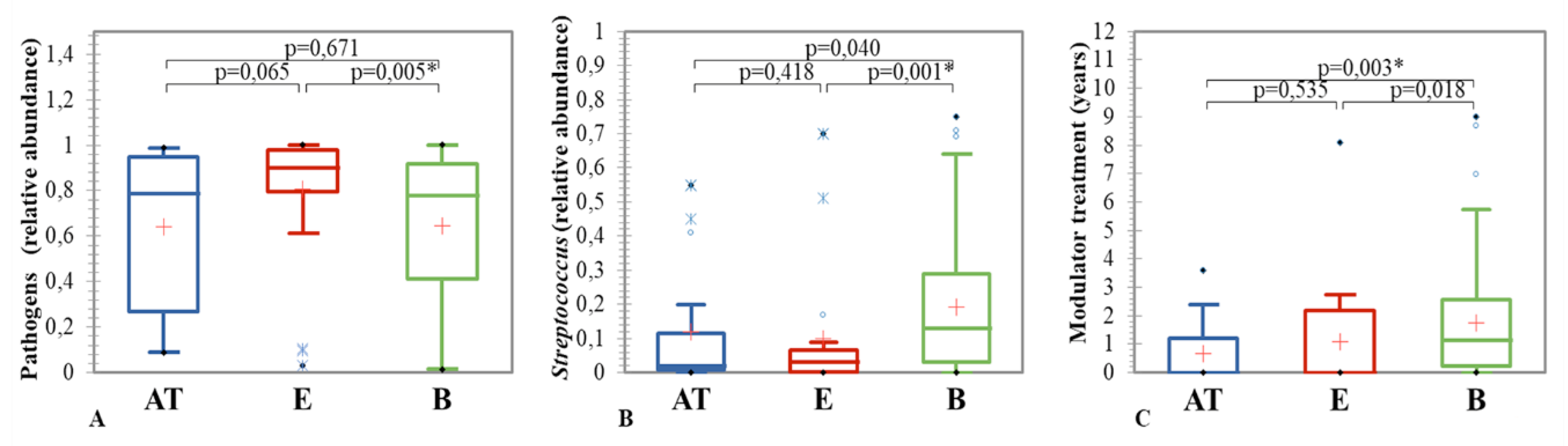

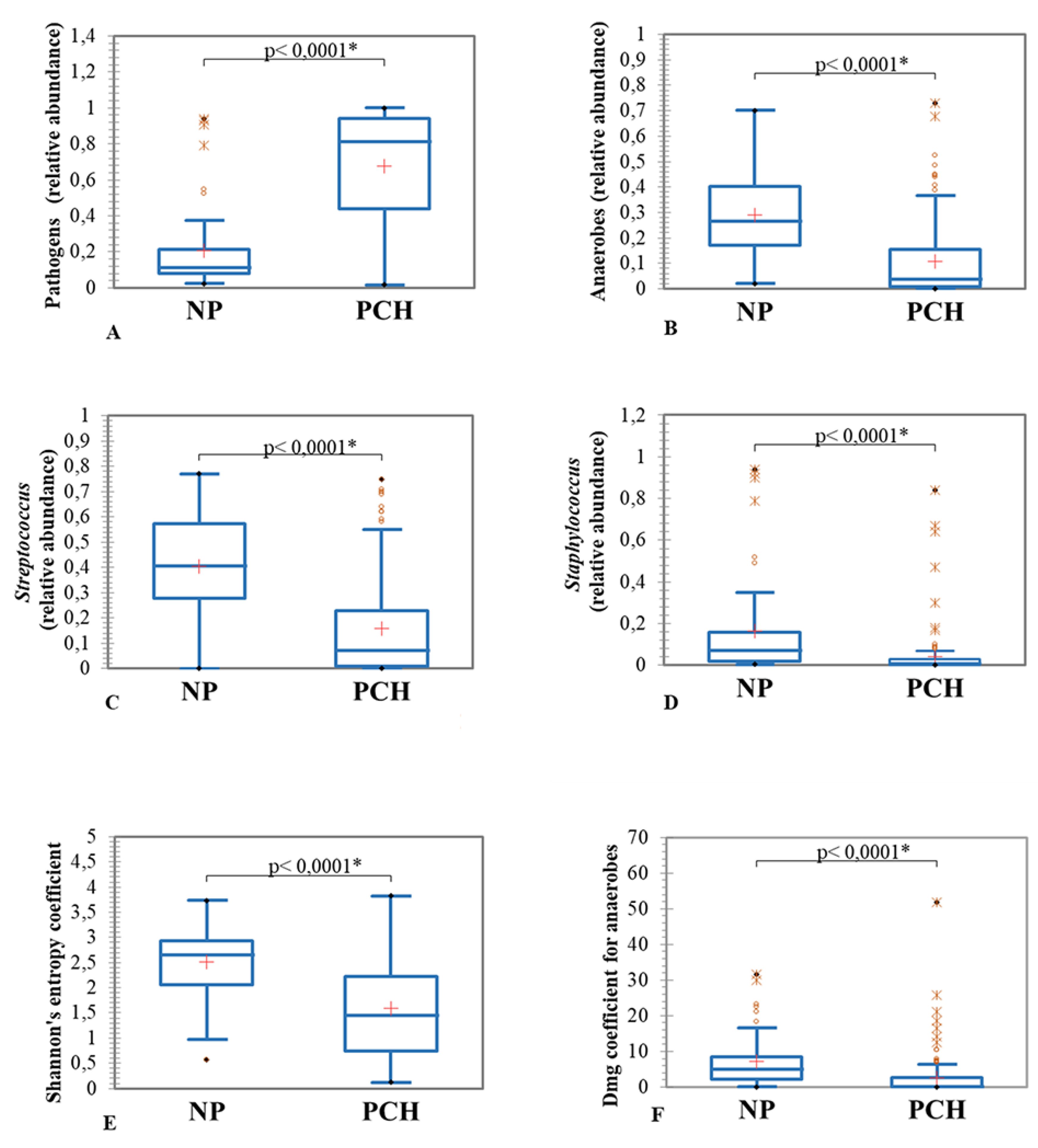

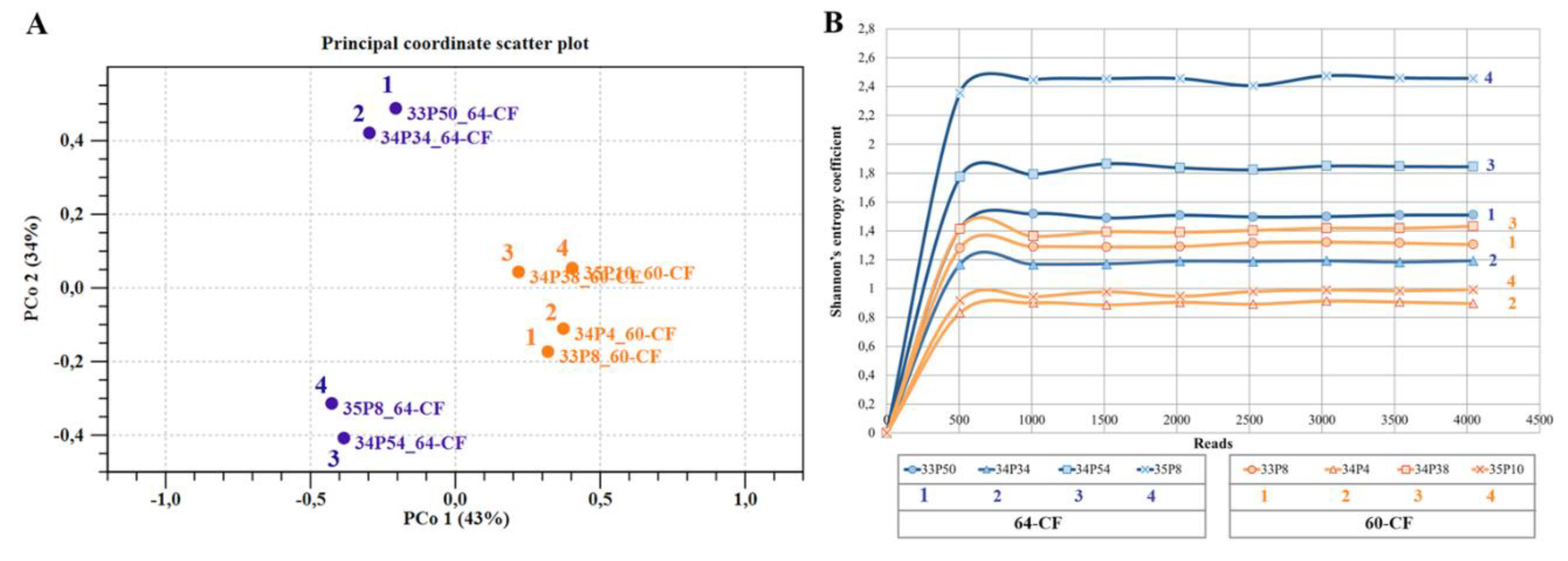

3.3.1. Clinical State and Sputum Microbiome Composition

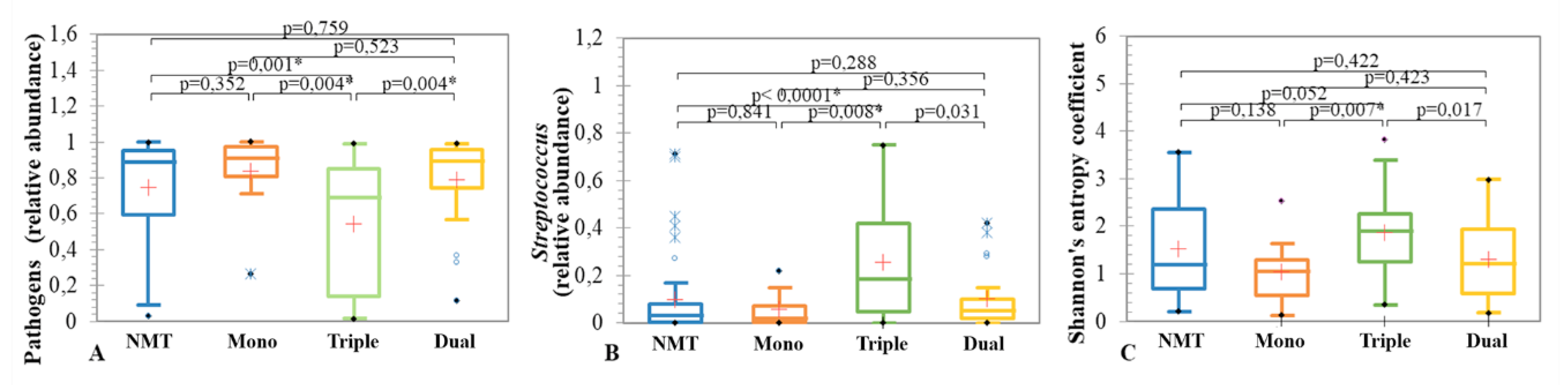

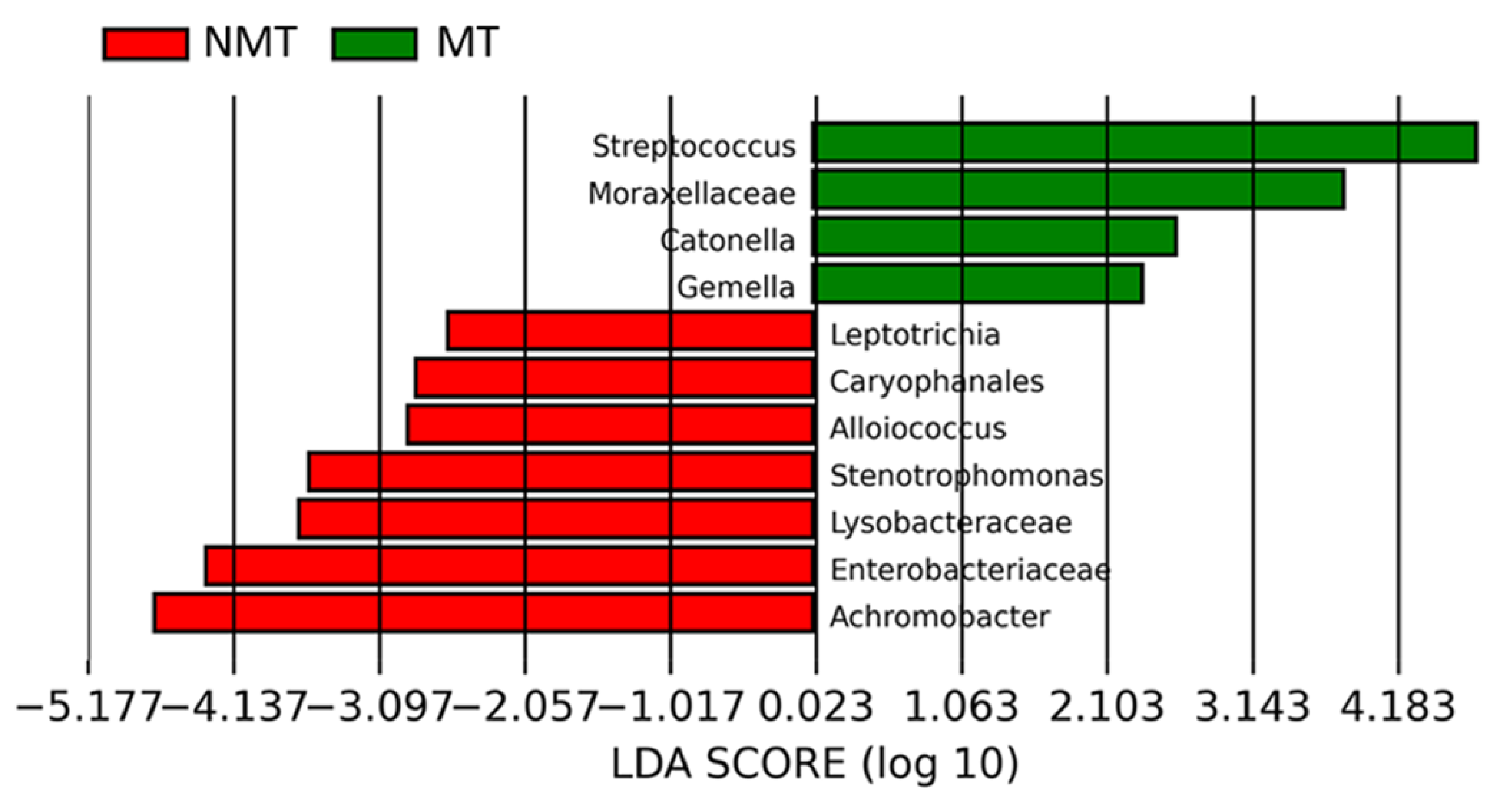

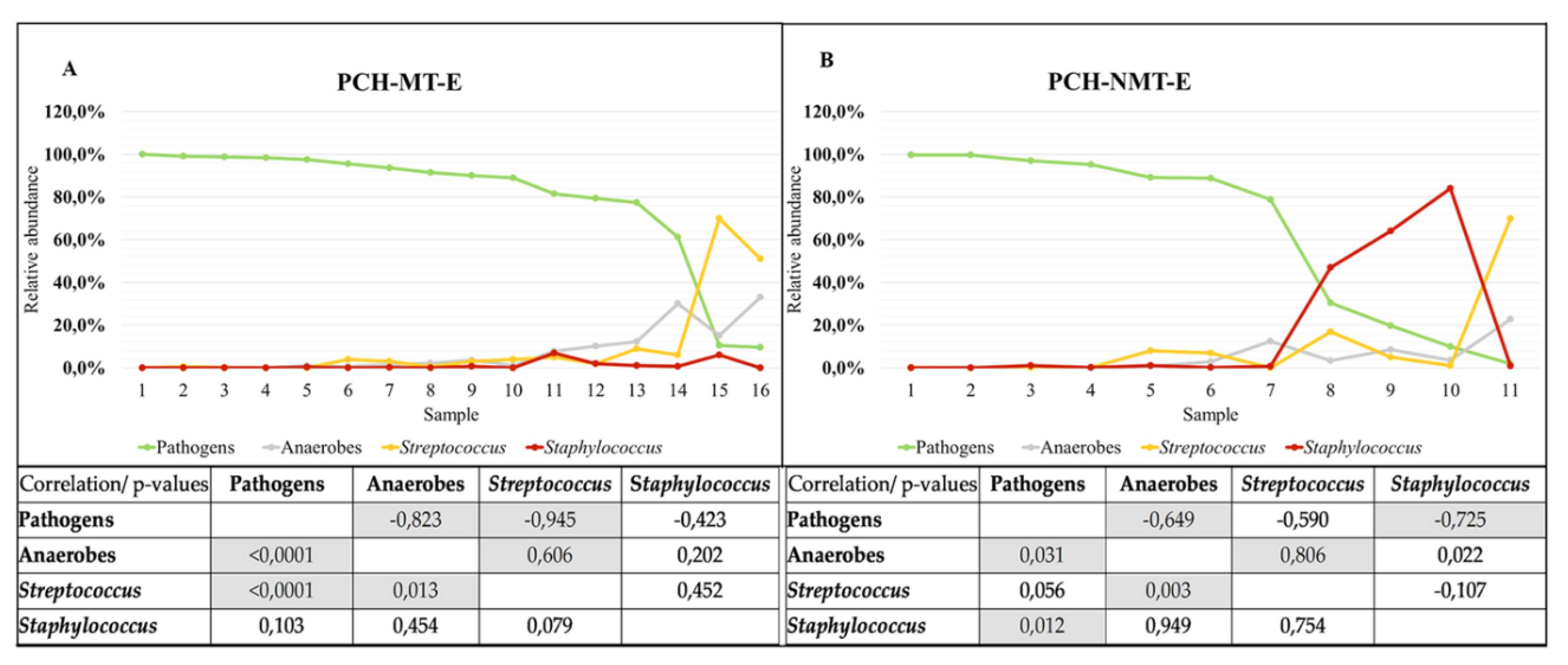

3.3.2. CFTR Modulators and Sputum Microbiome Composition

3.3.3. Samples Subgroups Based on the Presence/Absence of the Pseudomonadota Pathogens

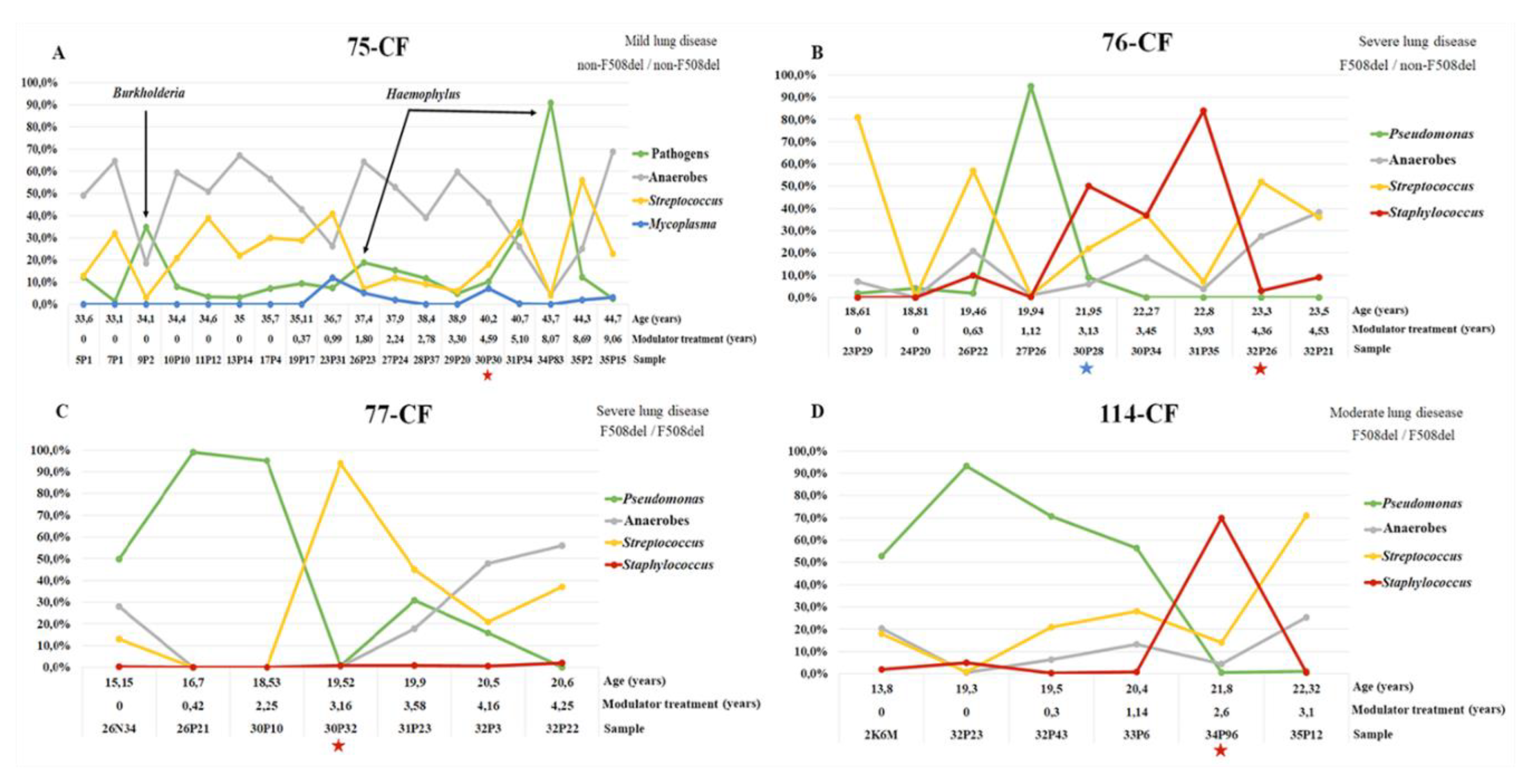

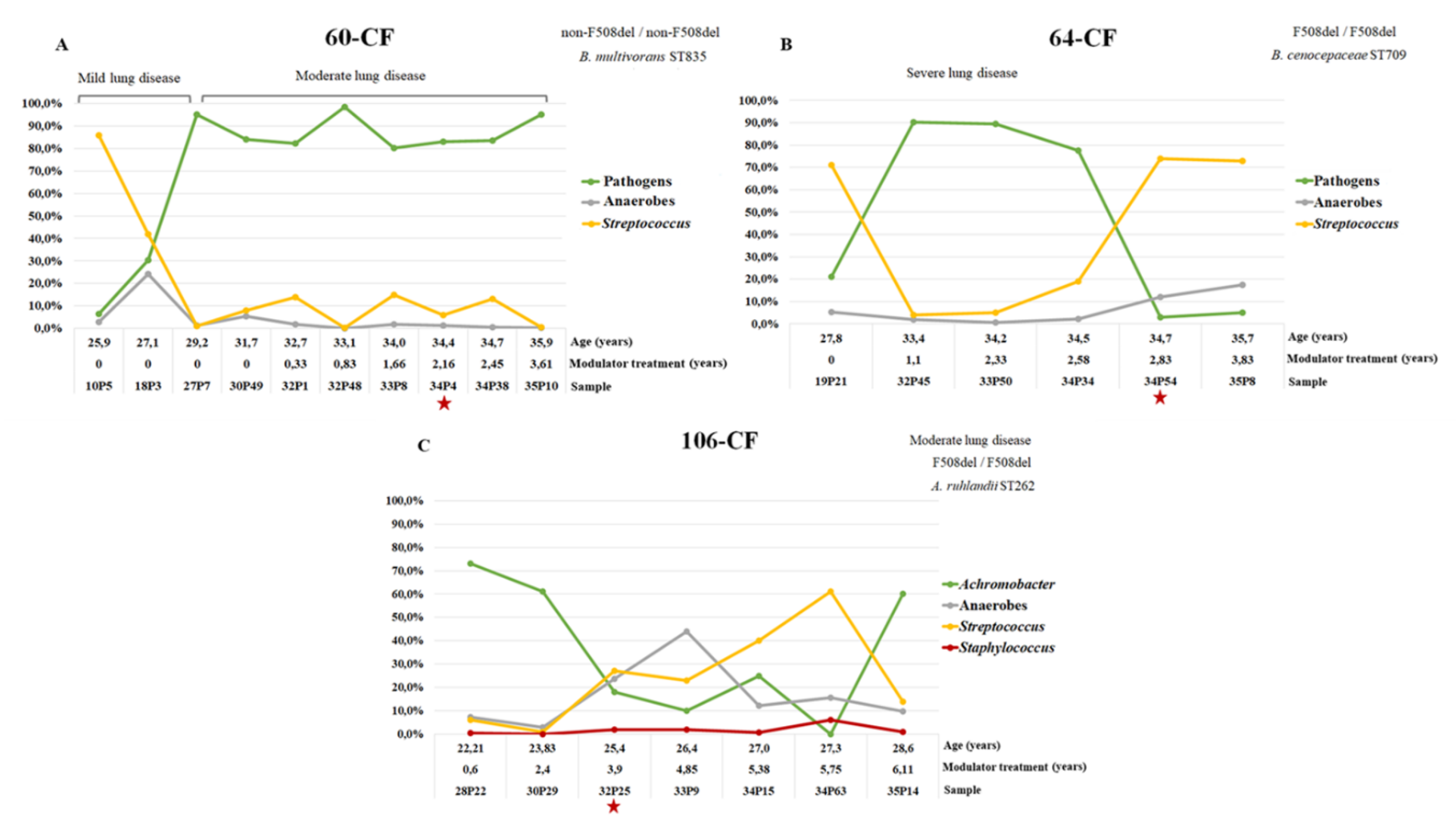

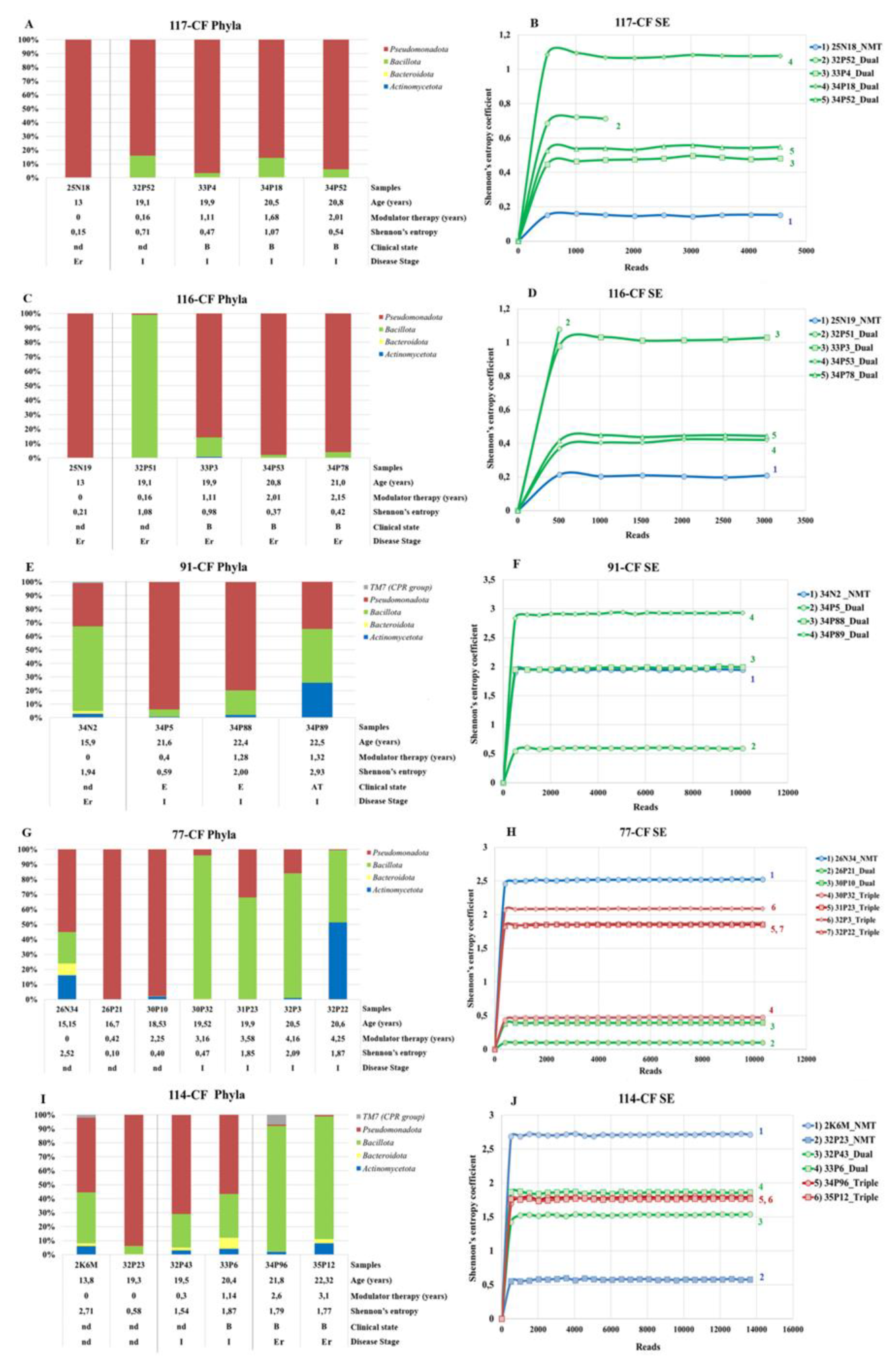

3.3.4. Microbiome of Samples from Patients Receiving Long-Term Modulator Therapy

3.3.5. Dynamics of the Microbiome Composition of Patients Chronically Infected with Pseudomonadota since Adolescence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| pwCF | Patients or people with CF |

| IVA | Ivacaftor |

| LUM | Lumacaftor |

| TEZ | Tezacaftor |

| ELX | Elexacaftor |

| MT | Modulator treatment |

| NMT | Non-modulator treatment |

| PCH | Chronically infected with Pseudomonadota |

| NP | With emerging Pseudomonadota and without Pseudomonadota |

| Bcc | Burkholderia cepacia complex |

| FEV1, %FEV1 | Percent predicted forced expiratory volume in one second |

| B | Baseline |

| E | Exacerbation |

| AT | Course of antibiotic therapy |

| Dmg | Margalef's Richness Index |

| OTU | Operational Taxonomic Units |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinate Analysis |

| LEfSe | Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size |

| early disease stage | FEV1 > 70% |

| intermediate | 70% < FEV1 > 40% |

| advanced | FEV1 < 40% |

References

- Marsland, B.J.; Gollwitzer, E.S. Host-microorganism interactions in lung diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinksi, J.H.; Ranjan, P.; Dickson, R.P.; O'Dwyer, D.N. The Lung Microbiome. J. Immunol. 2024, 212, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.C.; Mall, M.A.; Gutierrez, H.; Macek, M.; Madge, S.; Davies, J.C.; Burgel, P.R.; Tullis, E.; Castaños, C.; Castellani, C.; Byrnes, C.A.; Cathcart, F.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Cosgriff, R.; Eichler, I.; Fajac, I.; Goss, C.H.; Drevinek, P.; Farrell, P.M.; Gravelle, A.M.; Havermans, T.; Mayer-Hamblett, N.; Kashirskaya, N.; Kerem, E.; Mathew, J.L.; McKone, E.F.; Naehrlich, L.; Nasr, S.Z.; Oates, G.R.; O'Neill, C.; Pypops, U.; Raraigh, K.S.; Rowe, S.M.; Southern, K.W.; Sivam, S.; Stephenson, A.L.; Zampoli, M.; Ratjen, F. The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 65–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elborn, J.S. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2016, 388, 2519–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, A.C.; Waters, V.J. Microbiology of cystic fibrosis airway disease. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 40, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.J.; Olivier, K.N. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Cystic Fibrosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 40, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neill, K.; Bradley, J.M.; Johnston, E.; McGrath, S.; McIlreavey, L.; Rowan, S.; Reid, A.; Bradbury, I.; Einarsson, G.; Elborn, J.S.; Tunney, M.M. Reduced bacterial colony count of anaerobic bacteria is associated with a worsening in lung clearance index and inflammation in cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0126980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, C.D.; Grinwis, M.E.; Field, T.R.; Eshaghurshan, C.S.; Faria, M.M.; Dowd, S.E.; Parkins, M.D.; Rabin, H.R.; Surette, M.G. Culture enriched molecular profiling of the cystic fibrosis airway microbiome. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e22702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlebach, M.S.; Hatch, J.E.; Einarsson, G.G.; McGrath, S.J.; Gilipin, D.F.; Lavelle, G.; Mirkovic, B.; Murray, M.A.; McNally, P.; Gotman, N.; Davis Thomas, S.; Wolfgang, M.C.; Gilligan, P.H.; McElvaney, N.G.; Elborn, J.S.; Boucher, R.C.; Tunney, M.M. Anaerobic bacteria cultured from cystic fibrosis airways correlate to milder disease: a multisite study. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1800242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoureux, C.; Guilloux, C.A.; Beauruelle, C.; Gouriou, S.; Ramel, S.; Dirou, A.; Le Bihan, J.; Revert, K.; Ropars, T.; Lagrafeuille, R.; Vallet, S.; Le Berre, R.; Nowak, E.; Héry-Arnaud, G. An observational study of anaerobic bacteria in cystic fibrosis lung using culture dependent and independent approaches. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlebach, M.S.; Zorn, B.T.; Esther, C.R.; Hatch, J.E.; Murray, C.P.; Turkovic, L.; Ranganathan, S.C.; Boucher, R.C.; Stick, S.M.; Wolfgang, M.C. Initial acquisition and succession of the cystic fibrosis lung microbiome is associated with disease progression in infants and preschool children. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemanick, E.T.; Wagner, B.D.; Robertson, C.E.; Ahrens, R.C.; Chmiel, J.F.; Clancy, J.P.; Gibson, R.L.; Harris, W.T.; Kurland, G.; Laguna, T.A.; McColley, S.A.; McCoy, K.; Retsch-Bogart, G.; Sobush, K.T.; Zeitlin, P.L.; Stevens, M.J.; Accurso, F.J.; Sagel, S.D.; Harris, J.K. Airway microbiota across age and disease spectrum in cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kember, M.; Grandy, S.; Raudonis, R.; Cheng, Z. Non-Canonical Host Intracellular Niche Links to New Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanism. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigana, C.; Giannella, R.; Colavolpe, A.; Alcalá-Franco, B.; Mancini, G.; Colombi, F.; Bigogno, C.; Bastrup, U.; Bertoni, G.; Bragonzi, A. Mutual Effects of Single and Combined CFTR Modulators and Bacterial Infection in Cystic Fibrosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0408322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey C, Weldon S, Elborn S, Downey DG, Taggart C. The Effect of CFTR Modulators on Airway Infection in Cystic Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):3513. [CrossRef]

- Keating, C.; Yonker, L.M.; Vermeulen, F.; Prais, D.; Linnemann, R.W.; Trimble, A.; Kotsimbos, T.; Mermis, J.; Braun, A.T.; O'Carroll, M.; Sutharsan, S.; Ramsey, B.; Mall, M.A.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; McKone, E.F.; Tullis, E.; Floreth, T.; Michelson, P.; Sosnay, P.R.; Nair, N.; Zahigian, R.; Martin, H.; Ahluwalia, N.; Lam, A.; Horsley, A.; VX20-121-102 Study Group; VX20-121-103 Study Group. Vanzacaftor-tezacaftor-deutivacaftor versus elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor in individuals with cystic fibrosis aged 12 years and older (SKYLINE Trials VX20-121-102 and VX20-121-103): results from two randomised, active-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2025, 13, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertex Announces U.S. FDA Approval for TRIKAFTA (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor and ivacaftor) to Include Additional Non-F508del TRIKAFTA-Responsive Variants. Accessed January 6, 2025. https://investors.vrtx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/vertex-announcesus-fda-approval-trikafta. 6 January.

- Iftikhar, I.H.; Rao, S.T.; Nadama, R.; Janahi, I.; BaHammam, A.S. Comparative Efficacy of CFTR Modulators: A Network Meta-analysis. Lung. 2025, 203, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malet, K.; Faure, E.; Adam, D.; Donner, J.; Liu, L.; Pilon, S.J.; Fraser, R.; Jorth, P.; Newman, D.K.; Brochiero, E.; Rousseau, S.; Nguyen, D. Intracellular Pseudomonas aeruginosa within the Airway Epithelium of Cystic Fibrosis Lung Tissues. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledger, E.L.; Smith, D.J.; The, J.J.; Wood, M.E.; Whibley, P.E.; Morrison, M.; Goldberg, J.B.; Reid, D.W.; Wells, T.J. Impact of CFTR Modulation on Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection in People With Cystic Fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, e536–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, L.; Borish, L.; Noth, I.; Albon, D. Modulator-refractory cystic fibrosis: Defining the scope and challenges of an emerging at-risk population. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2024, 18, 17534666241297877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelina, E.L.; Kashirskaya, N.Y.; Kondratyeva, E.I.; Krasovskiy, S.A.; Starinova, M.A.; Voronkova, A.Yu.; Ginter, E.K. (Eds.) Registry of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis in the Russian Federation 2023; Publishing House “MEDPRACTIKA-M”: Moscow, Russia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carmody, L.A.; Caverly, L.J.; Foster, B.K.; Rogers, M.A.M.; Kalikin, L.M.; Simon, R.H.; VanDevanter, D.R.; LiPuma, J.J. Fluctuations in airway bacterial communities associated with clinical states and disease stages in cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0194060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstan, M.W.; Wagener, J.S.; VanDevanter, D.R. Characterizing aggressiveness and predicting future progression of CF lung disease. J Cyst Fibros. 2009, 8, S15–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronina, O.L.; Kunda, M.S.; Ryzhova, N.N.; Aksenova, E.I.; Semenov, A.N.; Lasareva, A.V.; Amelina, E.L.; Chuchalin, A.G.; Lunin, V.G.; Gintsburg, A.L. The Variability of the Order Burkholderiales Representatives in the Healthcare Units. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 680210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voronina, O.L.; Kunda, M.S.; Ryzhova, N.N.; Ermolova, E.I.; Goncharova, E.R.; Koroleva, E.A.; Kapotina, L.N.; Morgunova, E.Y.; Amelina, E.L.; Zigangirova, N.A. Chronic Escherichia coli ST648 Infections in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis: The In Vitro Effects of an Antivirulence. Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayati, A.A.; Farnia, P.; Mozafari, M.; Malekshahian, D.; Seif, S.; Rahideh, S.; Mirsaeidi, M. Molecular epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolates from clinical and environmental sources of a metropolitan city. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e114428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronina, O.L.; Kunda, M.S.; Ryzhova, N.N.; Aksenova, E.I.; Sharapova, N.E.; Semenov, A.N.; Amelina, E.L.; Chuchalin, A.G.; Gintsburg, A.L. On Burkholderiales order microorganisms and cystic fibrosis in Russia. BMC Genomics. 2018, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Nakai, R.; Hirakata, Y.; Kubota, K.; Satoh, H.; Nobu, M.K.; Narihiro, T.; Kuroda, K. Minisyncoccus archaeiphilus gen. nov., sp. nov., a mesophilic, obligate parasitic bacterium and proposal of Minisyncoccaceae fam. nov., Minisyncoccales ord. nov., Minisyncoccia class. nov. and Minisyncoccota phyl. nov. formerly referred to as Candidatus Patescibacteria or candidate phyla radiation. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2025, 75, 006668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugkar, P.P.; Collins, A.J.; Chen, T.; Dewhirst, F.E. Isolation and cultivation of candidate phyla radiation Saccharibacteria (TM7) bacteria in coculture with bacterial hosts. J. Oral. Microbiol. 2020, 12, 1814666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluchter, M.D.; Konstan, M.W.; Drumm, M.L.; Yankaskas, J.R.; Knowles, M.R. Classifying severity of cystic fibrosis lung disease using longitudinal pulmonary function data. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 174, 780–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronina, O.L.; Ryzhova, N.N.; Kunda, M.S.; Loseva, E.V.; Aksenova, E.I.; Amelina, E.L.; Shumkova, G.L.; Simonova, O.I.; Gintsburg, A.L. Characteristics of the Airway Microbiome of Cystic Fibrosis Patients. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2020, 85, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianowski, L.; Doléans-Jordheim, A.; Barraud, L.; Rabilloud, M.; Richard, M.; Josserand, R.N.; Durieu, I.; Reynaud, Q. One year of ETI reduces lung bacterial colonisation in adults with cystic fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaupp, L.; Addante, A.; Völler, M.; Fentker, K.; Kuppe, A.; Bardua, M.; Duerr, J.; Piehler, L.; Röhmel, J.; Thee, S.; Kirchner, M.; Ziehm, M.; Lauster, D.; Haag, R.; Gradzielski, M.; Stahl, M.; Mertins, P.; Boutin, S.; Graeber, S.Y.; Mall, M.A. Longitudinal effects of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on sputum viscoelastic properties, airway infection and inflammation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 62, 2202153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilliam, Y.; Armbruster, C.R.; Rapsinski, G.J.; Marshall, C.W.; Moore, J.; Koirala, J.; Krainz, L.; Gaston, J.R.; Cooper, V.S.; Lee, S.E.; Bomberger, J.M. Cystic fibrosis pathogens persist in the upper respiratory tract following initiation of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0078724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.P.; Morgan, S.J.; Skalland, M.; Vo, A.T.; Van Dalfsen, J.M.; Singh, S.B.; Ni, W.; Hoffman, L.R.; McGeer, K.; Heltshe, S.L.; Clancy, J.P.; Rowe, S.M.; Jorth, P.; Singh, P.K. PROMISE-Micro Study Group. Pharmacologic improvement of CFTR function rapidly decreases sputum pathogen density, but lung infections generally persist. J. Clin. Invest. 2023, 133, e167957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neerincx, A.H.; Whiteson, K.; Phan, J.L.; Brinkman, P.; Abdel-Aziz, M.I.; Weersink, E.J.M.; Altenburg, J.; Majoor, C.J.; Maitland-van der Zee, A.H.; Bos, L.D.J. Lumacaftor/Ivacaftor Changes the Lung Microbiome and Metabolome in Cystic Fibrosis Patients. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00731–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Schloss, P.D.; Kalikin, L.M.; Carmody, L.A.; Foster, B.K.; Petrosino, J.F.; Cavalcoli, J.D.; VanDevanter, D.R.; Murray, S.; Li, J.Z.; Young, V.B.; LiPuma, J.J. Decade-long bacterial community dynamics in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012, 109, 5809–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanick, E.T.; Wagner, B.D.; Robertson, C.E.; Ahrens, R.C.; Chmiel, J.F.; Clancy, J.P.; Gibson, R.L.; Harris, W.T.; Kurland, G.; Laguna, T.A.; McColley, S.A.; McCoy, K.; Retsch-Bogart, G.; Sobush, K.T.; Zeitlin, P.L.; Stevens, M.J.; Accurso, F.J.; Sagel, S.D.; Harris, J.K. Airway microbiota across age and disease spectrum in cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoureux, C.; Guilloux, C.A.; Beauruelle, C.; Gouriou, S.; Ramel, S.; Dirou, A.; Le Bihan, J.; Revert, K.; Ropars, T.; Lagrafeuille, R.; Vallet, S.; Le Berre, R.; Nowak, E.; Héry-Arnaud, G. An observational study of anaerobic bacteria in cystic fibrosis lung using culture dependent and independent approaches. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirković, B.; Murray, M.A.; Lavelle, G.M.; Molloy, K.; Azim, A.A.; Gunaratnam, C.; Healy, F.; Slattery, D.; McNally, P.; Hatch, J.; Wolfgang, M.; Tunney, M.M.; Muhlebach, M.S.; Devery, R.; Greene, C.M.; McElvaney, N.G. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Produced by Anaerobic Bacteria, in the Cystic Fibrosis Airway. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1314–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.M.; Niccum, D.; Dunitz, J.M.; Hunter, R.C. Evidence and Role for Bacterial Mucin Degradation in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Disease. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrard, L.J.; McGrath, S.J.; McIlreavey, L.; Hatch, J.; Wolfgang, M.C.; Muhlebach, M.S.; Gilpin, D.F.; Elborn, J.S.; Tunney, M.M. Production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and the potential indirect pathogenic role of Prevotella isolates from the cystic fibrosis respiratory microbiota. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2016, 47, 140–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caverly, L.J.; LiPuma, J.J. Good cop, bad cop: anaerobes in cystic fibrosis airways. Eur Respir J. 2018, 52, 1801146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Freeman, C.M.; McCloskey, L.; Beck, J.M.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Curtis, J.L. Spatial Variation in the Healthy Human Lung Microbiome and the Adapted Island Model of Lung Biogeography. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12, 821–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkins, M.D.; Sibley, C.D.; Surette, M.G.; Rabin, H.R. The Streptococcus milleri group--an unrecognized cause of disease in cystic fibrosis: a case series and literature review. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2008, 43, 490–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.E.; O'Toole, G.A. The Yin and Yang of Streptococcus Lung Infections in Cystic Fibrosis: a Model for Studying Polymicrobial Interactions. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00115–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendixen, M.P.; Jeppesen, M.; Irazoki, O.; Jensen, C.B.; Wang, M.; Petersen, J., Katzenstein, T.L.; Pressler, T.; Skov, M.; Olesen, H.V.; Jensen-Fangel, S.; Qvist, T.; Johansen, H.K.; TransformCF Study Group. Change in pulmonary pathogens 3 years after elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor: an observational study in the Danish cystic fibrosis cohort. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, S1198-743X(25)00408-2. [CrossRef]

- Widder, S.; Zhao, J.; Carmody, L.A.; Zhang, Q.; Kalikin, L.M.; Schloss, P.D.; LiPuma, J.J. Association of bacterial community types, functional microbial processes and lung disease in cystic fibrosis airways. ISME J. 2022, 16, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age groups | 18-23 years old | 24-30 years old | 31-56 years old |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (portion) in age groups | 15 (27.27%) | 15 (27.27%) | 25 (45.45%) |

| CFTR Mutation | patients/portion | ||

| F508del / F508del | 8 (53.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (12%) |

| F508del / non-F508del | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) | 12 (48%) |

| non-F508del / non-F508del | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 10 (40%) |

| Disease Stage | patients/portion | ||

| Early, FEV1 ≥70% | 4 (26.7%) | 4 (26.7%) | 2 (8%) |

| Intermediate, 40%≤FEV1<70% | 9 (60%) | 7 (46.7%) | 10 (40%) |

| Advanced, FEV1<40% | 2 (13.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 13 (52%) |

| Modulator therapy | patients/portion | ||

| modulator treatment - MT | 11 (73.3%) | 13 (86.7%) | 13 (52%) |

| non-modulator treatment -NMT | 4 (26.6%) | 2 (13.3%) | 12 (48%) |

| Prevalent groups of microorganisms | patients/portion | ||

| chronically infected with Pseudomonadota - PCH | 8 (53.3%) | 9 (60%) | 22 (88%) |

| with emerging Pseudomonadota - P | 3 (20%) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (8%) |

| without Pseudomonadota - NP | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 1 (4%) |

| Prevalent Pseudomonadota microorganisms | patients/portion | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5 (33.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 13 (52%) |

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (12%) |

| Achromobacter spp | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 4 (16%) |

| Enterobacteriacae | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (20%) | 1 (4%) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 1 (4%) |

| Duration of modulator treatment (years) | patients | ||

| Y_0 (Y < 1) | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Y_1 (1 ≤ Y < 2) | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| Y_2 (2 ≤ Y < 3) | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Y_3 (3 ≤ Y < 4) | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Y_6 (6 ≤ Y < 7) | 1 | ||

| Y_9 (9 ≤ Y < 10) | 1 | ||

| Type of modulator | patients | ||

| single-component | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| two-component | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| three-component | 4 | 8 | 6 |

| medicine was changed | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| medicine was canseled | 1 | 3 | |

| Variables | Pathogenes | Anaerobes | Streptococcus | Modulator therapy | Shennon’s entropy coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogens | 1 | -0,765 | -0,836 | -0,317 | -0,780 |

| Anaerobes | -0,765 | 1 | 0,414 | 0,267 | 0,760 |

| Streptococcus | -0,836 | 0,414 | 1 | 0,329 | 0,500 |

| Modulator therapy | -0,317 | 0,267 | 0,329 | 1 | 0,264 |

| Shannon’s entropy coefficient | -0,780 | 0,760 | 0,500 | 0,264 | 1 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).