Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

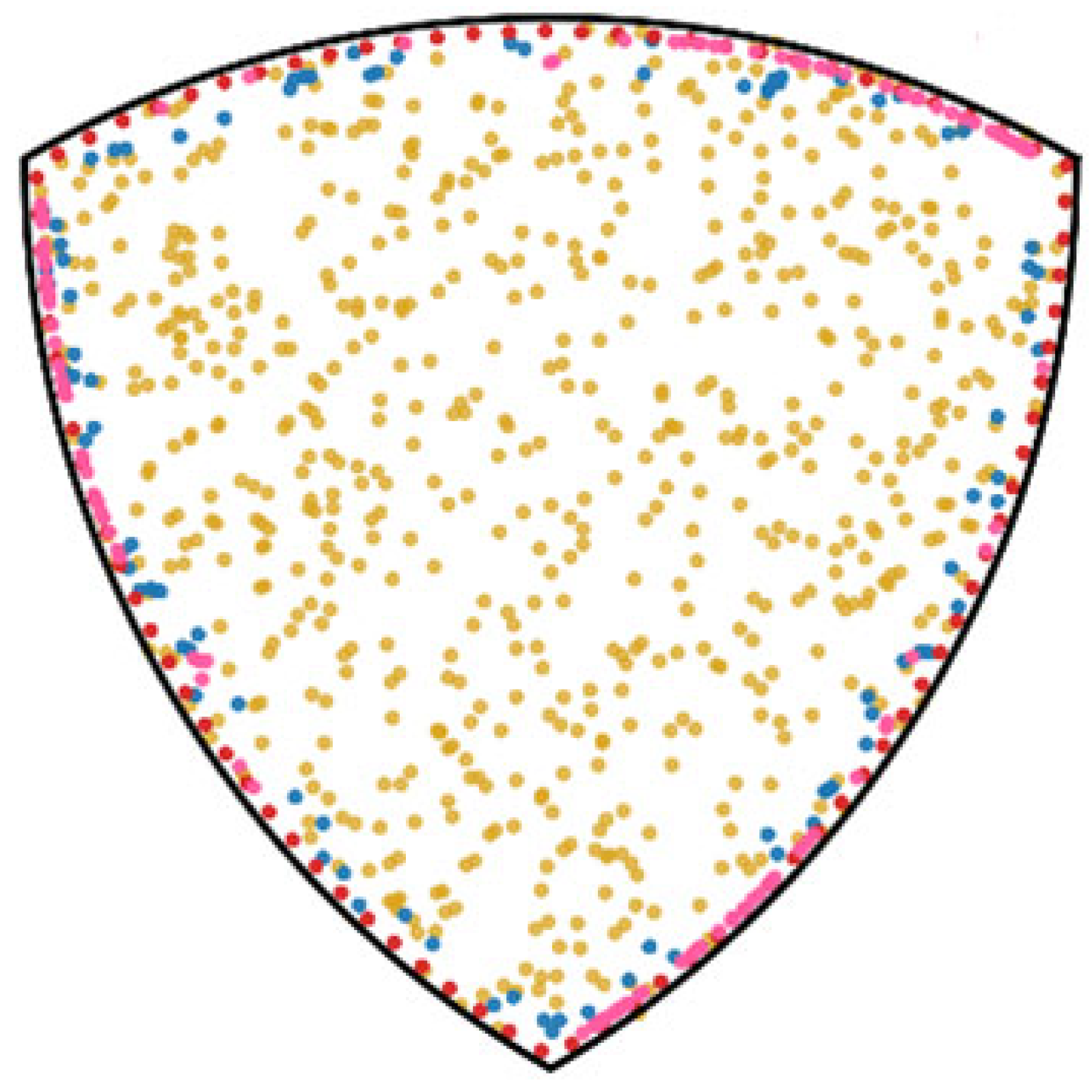

2. Geometric Criteria for the Density, Uniformity, and Localization of Cavitation Events in Process Industries

2.1. Availability of Nucleation Sites

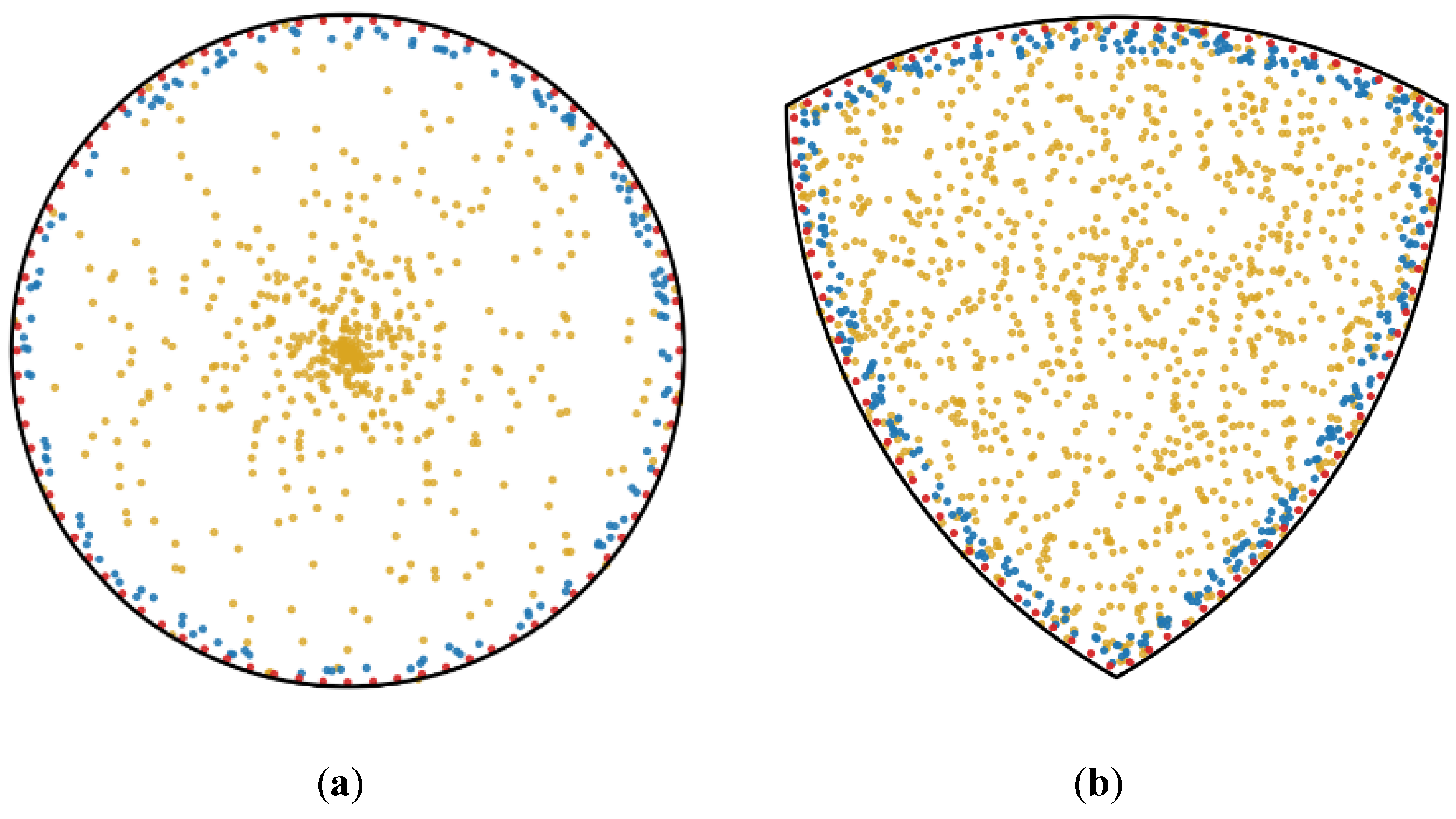

2.2. Density of Sites and Probability of Cavitation Inception

2.3. Distribution of Cavitation Events

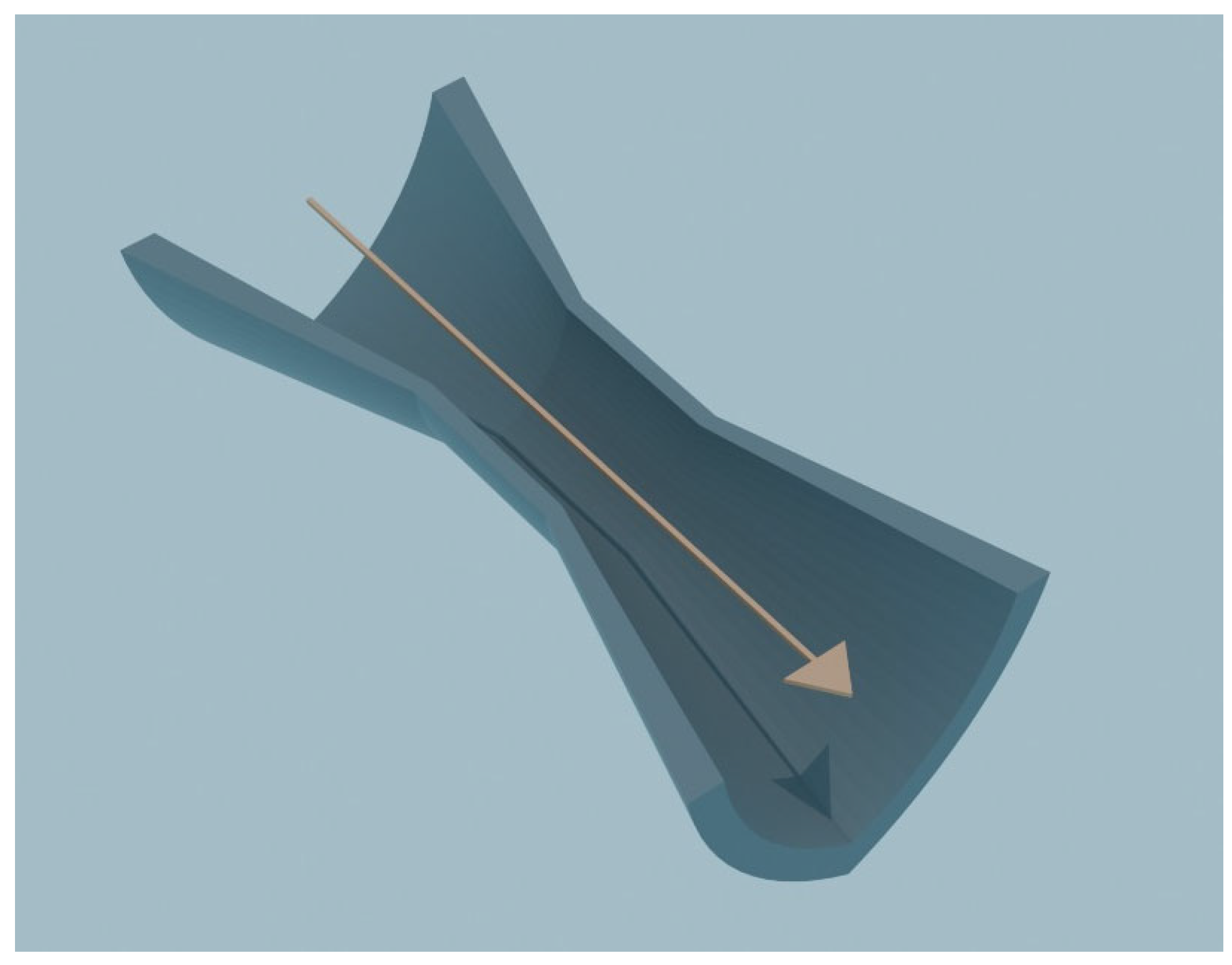

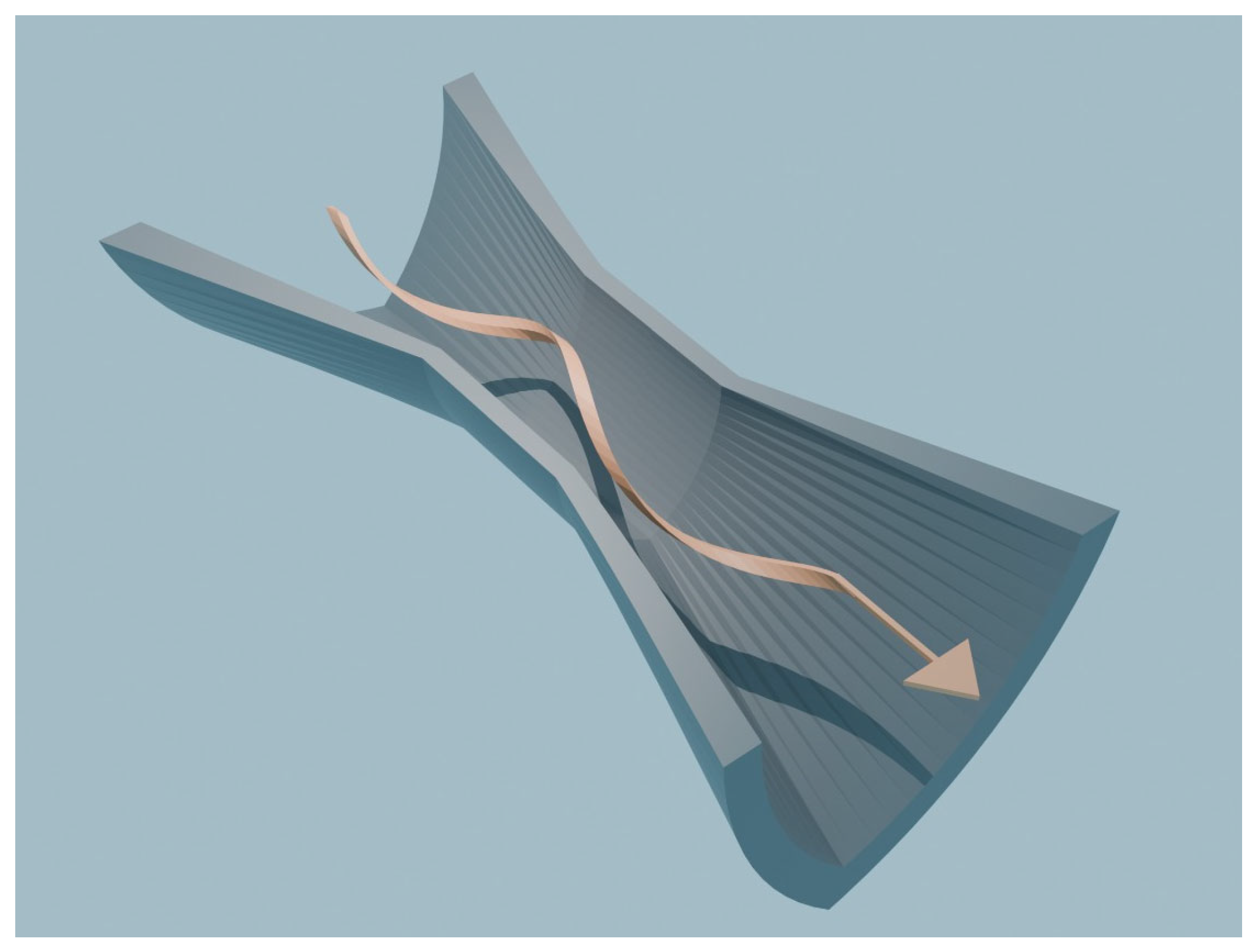

2.4. Localization of Inceptions with Swirl (VRAt): Kinematic Effects Near the Wall

3. Future Application Perspectives of the VRA and VRAt Geometries

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VRA | Venturi Reuleaux Albanese |

| VRAt | Venturi Reuleaux Albanese twist |

References

- Pandit, A.B.; Gogate, P.R. A review and assessment of hydrodynamic cavitation as a technology for the future. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2005, 12, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanekar, P.; Gogate, P. Application of Hydrodynamic Cavitation Reactors for Treatment of Wastewater Containing Organic Pollutants: Intensification Using Hybrid Approaches. Fluids 2018, 3, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Mechanistic and synergistic aspects of ultrasonics and hydrodynamic cavitation for food processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 1988–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennen, C.E. Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, J.P.; Michel, J.M. Fundamentals of Cavitation; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, P.; Sivakumar, M.; Pandit, A.B. Experimental Quantification of Chemical Effects of Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2000, 55, 1633–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.; Badve, M.; Rajoriya, S.; Pandit, A.B. Hydrodynamic cavitation: An emerging technology for the intensification of various chemical and physical processes in a chemical process industry. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2016, 32, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, J. Recent developments in hydrodynamic cavitation reactors: Cavitation mechanism, reactor design, and applications. Engineering 2022, 19, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, T.A.; Soni, A.G.; Mahulkar, A.V.; Pandit, A.B. The CFD Driven Optimization of a Modified Venturi for Cavitation Activity. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 89, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Bussonnière, A.; Bronson, M.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Q. Study of Venturi tube geometry on the hydrodynamic cavitation for the generation of microbubbles. Miner. Eng. 2019, 132, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiri, K.; Baradaran, S. Geometric Optimization of Venturi Reactors for Enhanced Hydrodynamic Cavitation Efficiency: From Conventional to Advanced Tandem Configurations. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2025, 24, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkapuram, S.T.; Sonawane, S.H. Intensified Physical and Chemical Processing Using Cavitation: How Far Are We from Commercial Applications of Hydrodynamic Cavitation? Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2025, 49, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloni, M.G.; Fabbrizio, V.; Giannantonio, R.; Falletta, E.; Bianchi, C.L. Applications and Applicability of the Cavitation Technology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2025, 48, 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, M.; Pandit, A.B. Wastewater Treatment: A Novel Energy Efficient Hydrodynamic Cavitational Technique. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2002, 9, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogate, P.R. Cavitation: An Auxiliary Technique in Wastewater Treatment Schemes. Adv. Environ. Res. 2002, 6, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogate, P.R.; Pandit, A.B. A Review of Imperative Technologies for Wastewater Treatment I: Oxidation Technologies at Ambient Conditions. Adv. Environ. Res. 2004, 8, 501–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darandale, G.R.; Jadhav, M.V.; Warade, A.R.; Hakke, V.S. Hydrodynamic cavitation a novel approach in wastewater treatment: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 77, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagal, M.V.; Gogate, P.R. Wastewater Treatment Using Hybrid Treatment Schemes Based on Cavitation and Fenton Chemistry: A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayaroth, M.P.; Federov, K.; Boczkaj, G.; Patil, Y.; Sonawane, S.H. Chapter 5 – Hydrodynamic Cavitation in Wastewater Treatment. In Advanced Technologies in Wastewater Treatment; Castro-Muñoz, R., Basile, A., Cassano, A., Eds.; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Guan, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L. The Application of Hydrodynamic Cavitation Technology and the Synergistic Effect of Hybrid Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Review. Water Sci. Technol. 2025, 92, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeneneh, A.M.; Al Balushi, K.; Jafary, T.; Al Marshudi, A.S.; Chittance, L.R.; Ben, L.S.; Ibrahim, H.A. Hydrodynamic Cavitation and Advanced Oxidation for the Treatment of Persistent Organic Pollutants: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiadani, M.; Taheri, E.; Bobade, V.; Fatehizadeh, A. Enhanced Degradation of Triclosan Using Aerated Hydrodynamic Cavitation: Turbulence-Based Modelling and Economic Evaluation. npj Clean Water 2025, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdini, F.; Crudo, D.; Bosco, V.; Kamler, A.V.; Cravotto, G.; Calcio Gaudino, E. Advanced Processes in Water Treatment: Synergistic Effects of Hydrodynamic Cavitation and Cold Plasma on Rhodamine B Dye Degradation. Processes 2024, 12, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez Llanos, S.; Mesia Chuquizuta, J.; Sanchez Purihuaman, M.; Carreño Farfan, C.; Ancieta Dextre, C.; Carrasco Venegas, L.; Córdova Rojas, L.; Díaz Bravo, P.; Medina Collana, J.; Barturen Quispe, A. Hydrodynamic Cavitation for Vinasse Treatment: Optimization Using the Taguchi Method and Phytotoxicity Evaluation. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2025, 118, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadik, A.; Akintunde, O.O.; Habibi, H.R.; Lebeau, T.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, F.; Achari, G. PFAS in Water Environments: Recent Progress and Challenges in Monitoring, Toxicity, Treatment Technologies, and Post-Treatment Toxicity. Environ. Syst. Res. 2025, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosel, J.; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, I.; Rački, N.; Dreo, T.; Ravnikar, M.; Dular, M. Efficient Inactivation of MS-2 Virus in Water by Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Water Res. 2017, 124, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, S.S.; Anil, A.C.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Gaonkar, C.; Kolwalkar, J.; Khandeparker, L.; Desai, D.; Mahulkar, A.V.; Ranade, V.V.; Pandit, A.B. Effect of Hydrodynamic Cavitation on Zooplankton: A Tool for Disinfection. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008, 42, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye-Wood, M.G.; Byrne, K.; Stockwell, S.; Juhász, A.; Bose, U.; Colgrave, M.L. Low Gluten Beers Contain Variable Gluten and Immunogenic Epitope Content. Foods 2023, 12, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.S.; More, P.R.; Ladole, M.R.; Pegu, K.; Pandit, A.B. Non-thermal, energy efficient hydrodynamic cavitation for food processing, process intensification and extraction of natural bioactives: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 98, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaithambi, N.; Singha, P.; Singh, S.K. Hydrodynamic cavitation and its application in food and beverage industry: A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e13144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoglopiti, E.; Roufou, S.; Psakis, G.; Okafor, E.T.; Dasenaki, M.; Gatt, R.; Valdramidis, V.P. Unravelling the Hydrodynamic Cavitation Potential in Food Processing: Underlying Mechanisms, Crucial Parameters, and Antimicrobial Efficacy. Food Eng. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Bustos, K.A.; Rossetti, C.; Frascarelli, D.; Brunori, G. Hydrodynamic cavitation as a promising technology for fresh produce-based beverages processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 96, 103784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ferreira, D.F.; Crudo, D.; Bosco, V.; Stevanato, L.; Costale, A.; Cravotto, G. Plant and biomass extraction and valorisation under hydrodynamic cavitation. Processes 2019, 7, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.S. Advancing phytonutrient extraction via cavitation-based methodology: Exploring catechin recovery from Camellia sinensis leaves. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 54, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Scurria, A.; Pagliaro, M. Natural Product Extraction via Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 33, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, D.; Zhao, J.; Ranade, V.V. Cavitation technologies for extraction of high value ingredients from renewable biomass. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 174, 117682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H.; Hiromori, K.; Shibasaki-Kitakawa, N. Simultaneous extraction of caffeic acid and production of cellulose microfibrils from coffee grounds using hydrodynamic cavitation in a Venturi tube. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 108, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xuan, X.; Ji, L.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S.; Park, S.; Yoon, J.Y.; Om, A.S. A novel continuous hydrodynamic cavitation technology for the inactivation of pathogens in milk. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 71, 105382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Hao, Z.; Manickam, S.; Liu, G.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; Bie, H. ; Evaluation of Disinfection and Cavitation Performance of a Cylindrical Rotational Hydrodynamic Cavitation Reactor: Influence of Key Geometric Parameters of the Cavitation Generation Unit. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 121, 107544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boček, Ž.; Procházka, J.; Málek, J.; Szymański, P.; Veverka, P. Kelvin–Helmholtz instability as one of the key features for fast and efficient emulsification by hydrodynamic cavitation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 108, 106970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, N.; Ren, X.; Yang, F.; Huang, Y.; Wei, F.; Yang, L. The Effect of Hydrodynamic Cavitation on the Structural and Functional Properties of Soy Protein Isolate–Lignan/Stilbene Polyphenol Conjugates. Foods 2024, 13, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleite, S.N.; Balbi, M.d.P.; Ayude, M.A.; Cassanello, M. Rheological Features of Aqueous Polymer Solutions Tailored by Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Fluids 2025, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, L.; Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M. Beer-brewing powered by controlled hydrodynamic cavitation: Theory and real-scale experiments. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, L.; Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M. Beer produced via hydrodynamic cavitation retains higher amounts of xanthohumol and other hops prenylflavonoids. LWT. 2018, 256, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L. Intensification of the Dimethyl Sulfide Precursor Conversion Reaction: A Retrospective Analysis of Pilot-Scale Brewer’s Wort Boiling Experiments Using Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Beverages 2025, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, L.; Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M. Gluten reduction in beer by hydrodynamic cavitation assisted brewing of barley malts. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 82, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, L.; Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M. Innovative beer-brewing of typical, old and healthy wheat varieties to boost their spreading. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, L.; Meneguzzo, F. Hydrodynamic Cavitation-Assisted Processing of Vegetable Beverages: Review and the Case of Beer-Brewing. In Production and Management of Beverages; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 211–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L.; Zabini, F. Hydrodynamic Cavitation in Beer and Other Beverage Processing. In Innovative Food Processing. In Innovative Food Processing Technologies; Knoerzer, K., Muthukumarappan, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štěrba, J.; Punčochář, M.; Brányik, T. The effect of hydrodynamic cavitation on isomerization of hop alpha-acids, wort quality and energy consumption during wort boiling. Food Bioprod. Process. 2024, 144, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qin, J.; Sun, H.; Ruan, Y.; Fang, D.; Wang, J. The changes induced by hydrodynamic cavitation treatment in wheat gliadin and celiac-toxic peptides. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 1976–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, A.M.A. Application of Hydrodynamic Cavitation in Brewing: Impacts on Gluten Levels and Process Efficiency; Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2022. Available online: https://repositorium.uminho.pt/entities/publication/22813ddc-5821-4a4d-a1e3-e981bffa726d. [Google Scholar]

- Montusiewicz, A.; Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Lebiocka, M.; Szaja, A.; Szymańska-Chargot, M. Hydrodynamic cavitation of brewery spent grain diluted by wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 313, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Dębowski, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Nowicka, A.; Dudek, M. Application of Hydrodynamic Cavitation in the Disintegration of Aerobic Granular Sludge—Evaluation of Pretreatment Time on Biomass Properties, Anaerobic Digestion Efficiency and Energy Balance. Energies 2024, 17, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, A.; Nagula, K.; Pandit, A.; Arya, S. Hydrodynamic cavitation for energy efficient and scalable process of microalgae cell disruption. Algal Res. 2019, 40, 101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Ranade, V.V. Bioactives from microalgae: A review on process intensification using hydrodynamic cavitation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 1129–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Rozo, J.R.; Caicedo-Peñaranda, E.A.; Riesco-Avila, J.M. Hydrodynamic Cavitation in Shockwave-Power-Reactor-Assisted Biodiesel Production in Continuous from Soybean and Waste Cooking Oil. Energies 2025, 18, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, S.S.; Pandit, A.B.; Joshi, J.B. Microbial cell disruption: role of cavitation. Chem. Eng. J. Biochem. Eng. J. 1994, 55, B67–B72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundaram, B.; Harrison, S.T.L. Disruption of Brewers' yeast by hydrodynamic cavitation: Process variables and their influence on selective release. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006, 94, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogate, P.R.; Kabadi, A.M. A review of applications of cavitation in biochemical engineering/biotechnology. Biochem. Eng. J. 2009, 44, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharan, V.K.; Pandit, A.B.; SatishKumar, P.S.; Anandan, S. Hydrodynamic cavitation as an advanced oxidation technique for the degradation of Acid Red 88 dye. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Degradation of Alachlor in Aqueous Solution by Using Hydrodynamic Cavitation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jia, J.; Wang, Y. Degradation of C.I. Reactive Red 2 Through Photocatalysis Coupled with Water Jet Cavitation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeutigam, P.; Franke, M.; Schneider, R.J.; Lehmann, A.; Stolle, A.; Ondruschka, B. Degradation of Carbamazepine in Environmentally Relevant Concentrations in Water by Hydrodynamic-Acoustic-Cavitation (HAC). Water Res. 2012, 46, 2469–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Morton, J.A.; Tyurnina, A.V.; Priyadarshi, A.; Ghorbani, M.; Mi, J.; Porfyrakis, K.; Eskin, D.G.; Tzanakis, I. Dual frequency ultrasonic liquid phase exfoliation method for the production of few layer graphene in green solvents. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 108, 106954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, H.; Lu, B.; et al. Effects of ultrasonic cavitation on microstructure and surface properties of Mn–Cu alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 40, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz Nayir, T.; Küçükağa, Y.; Kara, S. Hydrodynamic Cavitation Assisted Recovery of Intracellular Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 48, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosel, J.; Šuštaršič, M.; Petkovšek, M.; Gregorc, A.; Hočevar, M.; Dular, M. Application of (super)cavitation for the recycling of process waters in paper producing industry. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 64, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebiocka, M.; Montusiewicz, A.; Grządka, E.; Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Montusiewicz, J.; Szaja, A. Hydrodynamic cavitation as a method of removing surfactants from real carwash wastewater. Molecules 2024, 29, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.A.; Zhenghe Xu, J.A.; Finch, J.H.; Masliyah, R.S.; Chow, R.S. On the role of cavitation in particle collection in flotation – A critical review. II. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovšek, M.; Zupanc, M.; Dular, M.; Kosjek, T.; Heath, E.; Kompare, B.; Širok, B. Rotation generator of hydrodynamic cavitation for water treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 118, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Senocak, I.; Shyy, W.; Ikohagi, T.; Cao, S. Dynamics of attached turbulent cavitating flows. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2001, 37, 551–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molland, A.F.; Turnock, S.R. Chapter 6 – Rudder Experimental Data. In Marine Rudders, Hydrofoils and Control Surfaces, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 105–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, J.S. Chapter 9 – Cavitation. In Marine Propellers and Propulsion, 3rd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 209–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, L. The Venturi Reuleaux Triangle: Advancing Sustainable Process Intensification Through Controlled Hydrodynamic Cavitation in Food, Water, and Industrial Applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havil, J. Chapter Seven. Curves of Constant Width. In Curves for the Mathematically Curious: An Anthology of the Unpredictable, Historical, Beautiful, and Romantic; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Configuration | ||||

| Circular | = | = | = | |

| VRA | ||||

| VRAt |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).