Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

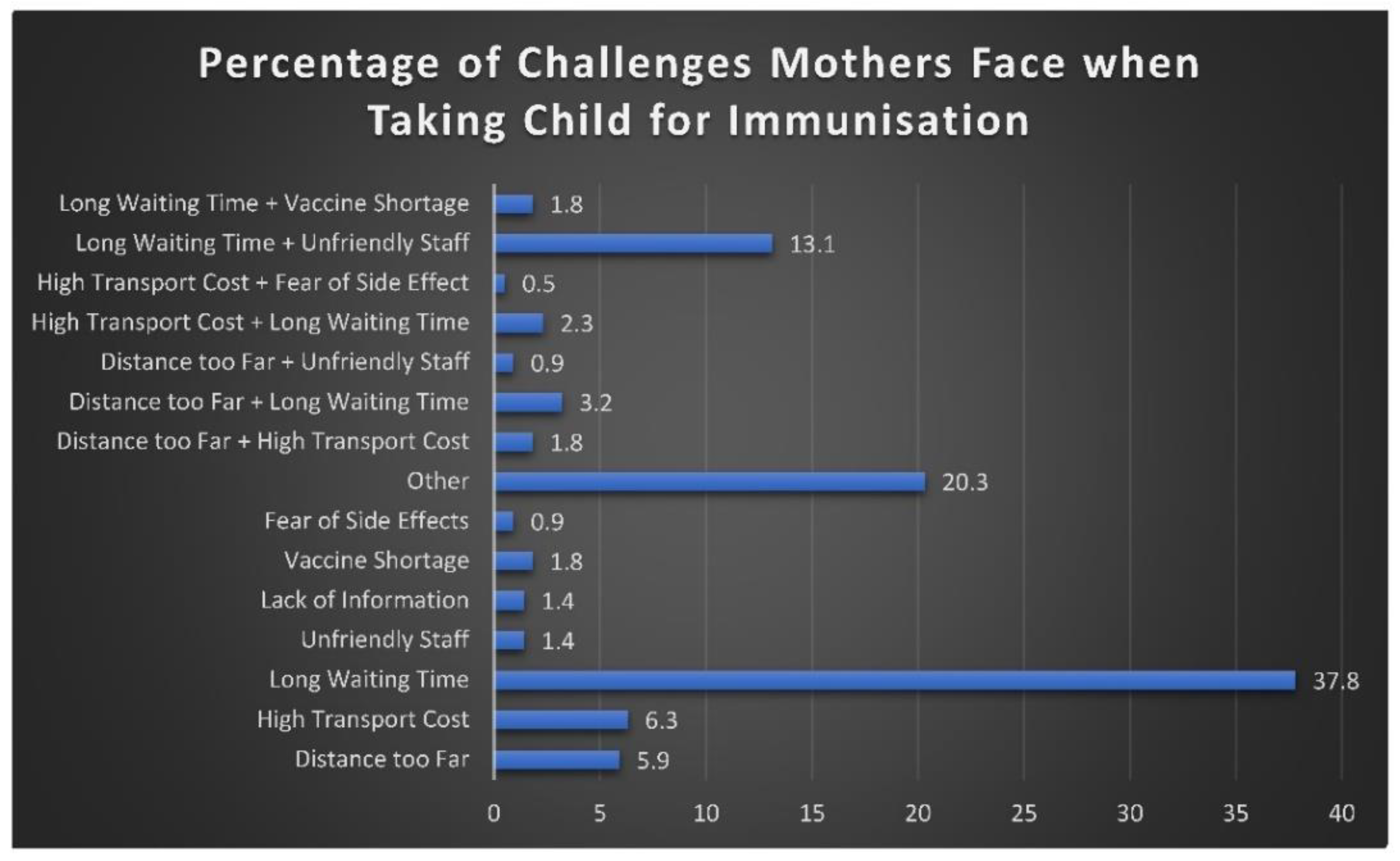

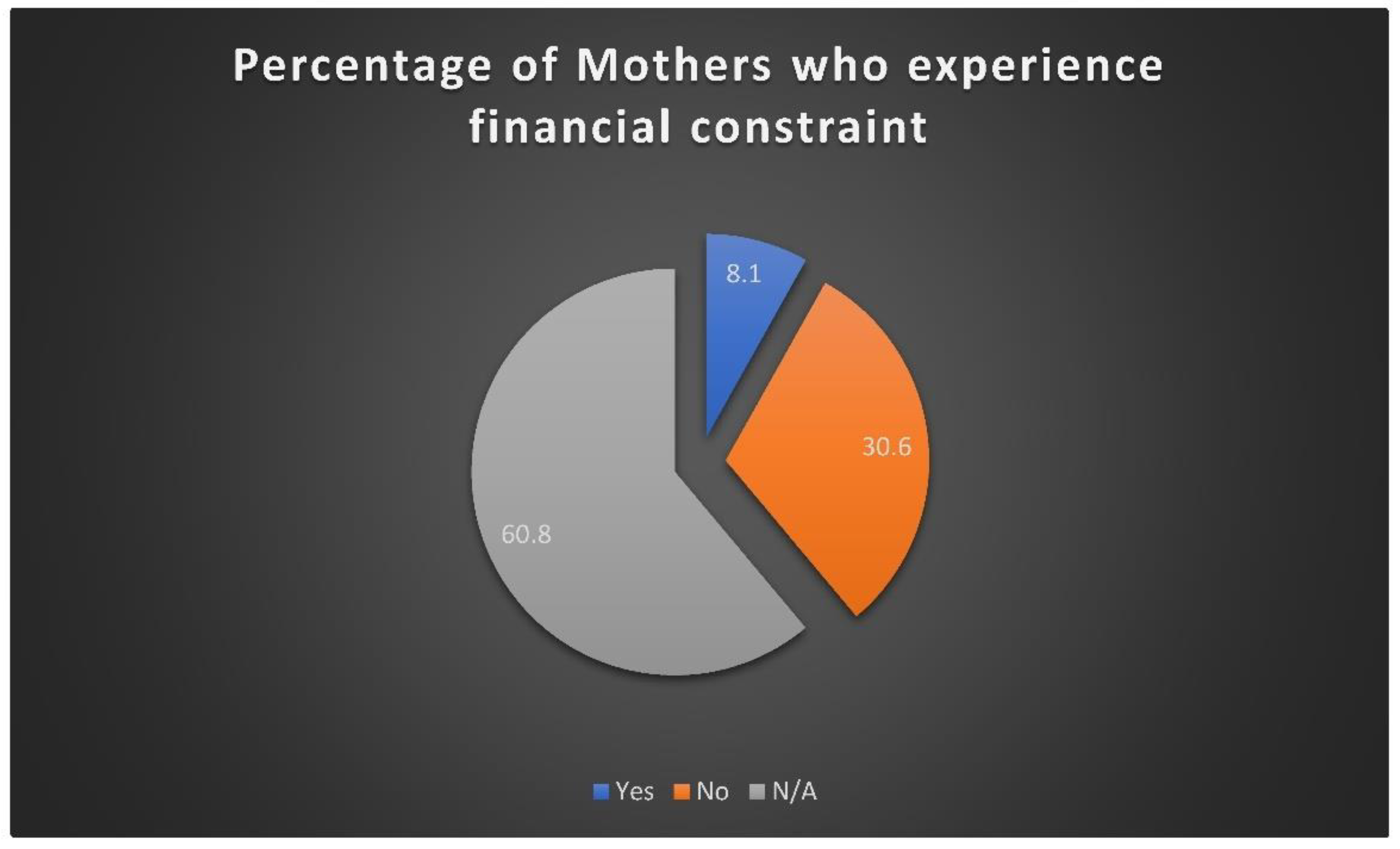

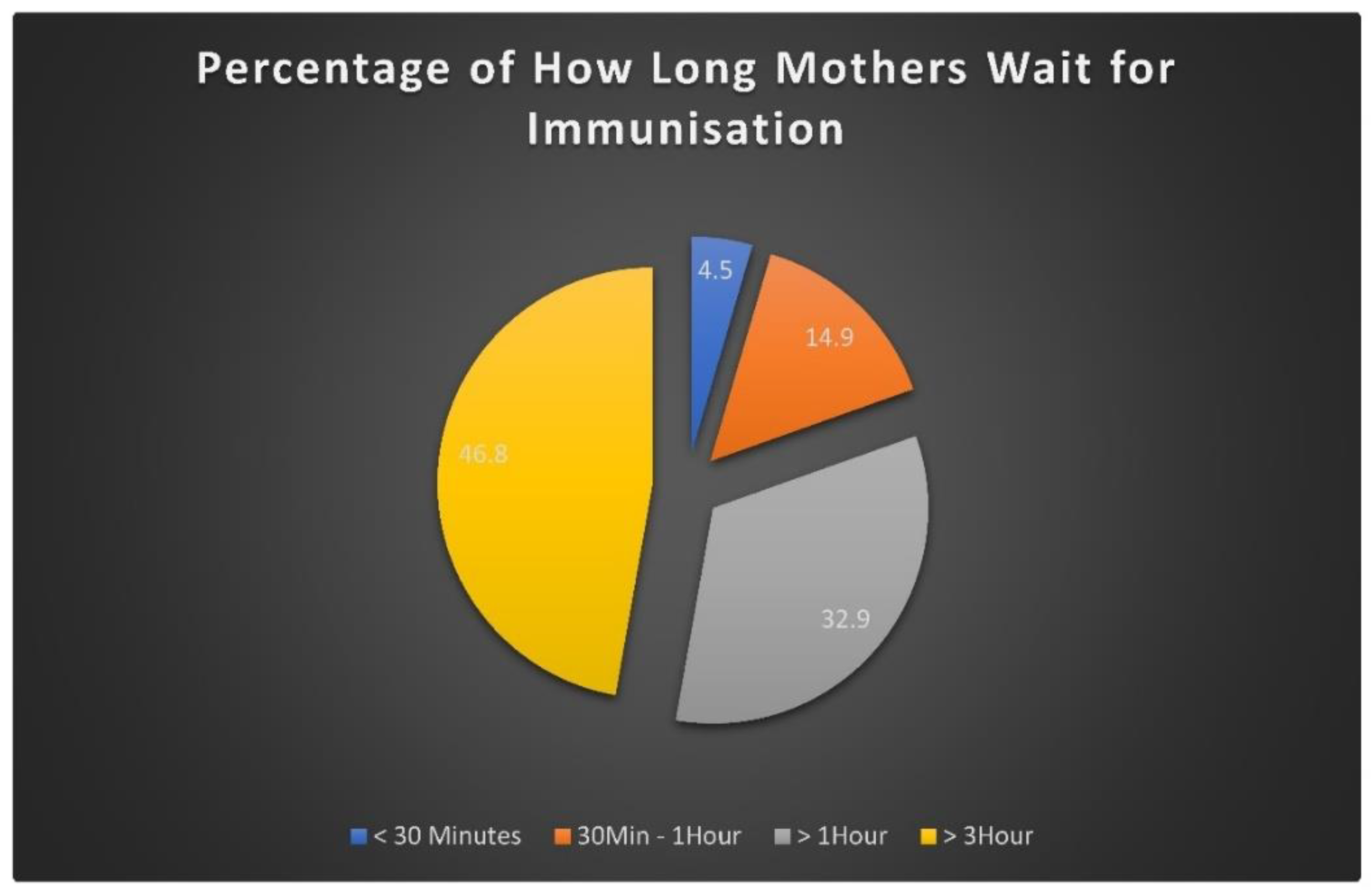

Background: Immunisation is a protective measure against infectious diseases and is one of the most crucial public health interventions (WHO, 2019). Mothers face challenges which are facility-related factors such as long waiting times, stock-outs and negative staff attitudes, as well as cultural and religious beliefs held by mothers and families, which further shape whether children receive vaccinations (Wiysonge et al, 2020; South Africa qualitative study, 2023). Purpose: The aim of the study was to assess the experiences of mothers in accessing childhood immunisation services from the perspective of mothers in the paediatric outpatient department at a tertiary hospital in South Africa. Methodology: A quantitative cross-sectional design approach was used to investigate the challenges faced by mothers when accessing childhood vaccination. A probability sampling method was used to sample 221 respondents by means of systemic sampling. Data was collected by means of self-administered questionnaire. Validity was ensured through face and content validity. The reliability was ensured through clear and detailed instructions as well as pilot testing. Data was collected and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 27. The results analyzed were then carefully interpreted to identify key trends and patterns. The data analyzed was presented visually through tables and charts to make the findings easier to understand and interpret. Results: The study comprised of 222 participants. The study results showed that majority of mothers knew and understood enough about immunization and their advantages. However, long waiting times, high transport expenses and vaccine shortages made it difficult for many of the mothers and impacted schedule adherence. According to the study’s findings, expanding vaccine coverage requires improving service accessibility, effectiveness and ongoing health education. Conclusion: The study revealed that mothers face several challenges when accessing childhood immunisation services, including long waiting times, lack of information regarding vaccines and limited accessibility. These barriers negatively impact immunisation uptake and threaten child health outcomes. Recommendations: Addressing the challenges that mothers face when accessing immunisation through improved health education, resource allocation, and community engagement is essential to strengthen immunisation coverage.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

1.2. Purpose of the Study

1.3. Objectives of the Study

- To describe the impact of socio-economic and primary healthcare facilities-related factors on mothers’ access to childhood vaccination services.

- To assess mothers’ experiences with accessing childhood immunisation services.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Approach

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Site

2.4. Study Population

3. Sampling

3.1. Criteria for Inclusion

- Mothers of children under the age of 12 years who are currently receiving childhood immunisation.

- Mothers of children above the age of 12 years who have undergone childhood immunisation.

- Mothers who are 18 years older, as they were able to give consent.

3.2. Sampling Size

- Inclusion Criteria

- Mothers of children under the age of 12 years who are currently receiving childhood immunisation.

- Mothers of children above the age of 12 years who have undergone childhood immunisation.

- Mothers who are 18 years older and were able to give consent.

- Exclusion criteria

- Mothers with children who have never received childhood immunisation.

- Mothers younger than 18 years of age (cannot give consent).

- Mothers who are not willing to sign a consent form.

3.3. Sampling Technique

4. Data Collection Instrument

5. Validity and Reliability of Measuring Instrument

6. Pilot Study

7. Procedure for Data Collection

8. Management of Data and Analysis of Data

9. Ethical Consideration

10. Results

| Demographic Characteristics | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 0 | 0% |

| Female | 222 | 100% |

| Age | ||

| 18-25 | 33 | 14.9% |

| 26-35 | 117 | 52.7% |

| 36 and above | 72 | 32.4% |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 178 | 80.2% |

| Married | 41 | 18.5% |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.5% |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.5% |

| Educational level | ||

| No formal education | 5 | 2.3% |

| Primary | 12 | 5.4% |

| Secondary | 124 | 55.9% |

| Tertiary | 81 | 36.5% |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 61 | 27.5% |

| Unemployed | 143 | 64.4% |

| Student | 11 | 5% |

| Informal worker | 7 | 3.2% |

| Household income | ||

| Less than R6888 | 161 | 72.5% |

| Between R6890 – R48752 | 40 | 18% |

| Above R48753 | 7 | 3.2% |

| Number of children | ||

| 0-1 | 73 | 32.9% |

| 2-4 | 127 | 57.2% |

| 5-7 | 8 | 3.6% |

| 8-11 | 1 | 0.5% |

| Age of youngest child | ||

| 0-1 | 69 | 31.1% |

| 2-4 | 62 | 27.9% |

| 5-7 | 42 | 18.9% |

| 8-11 | 33 | 14.9% |

| More than 12 | 16 | 7.2% |

| Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Have you heard of childhood immunisation before? | 90.1 | 9.0 |

| Do you know the recommended immunisation schedule? | 82.9% | 15.8% |

| Have you received a booklet for your child? | 83.8% | 14.9% |

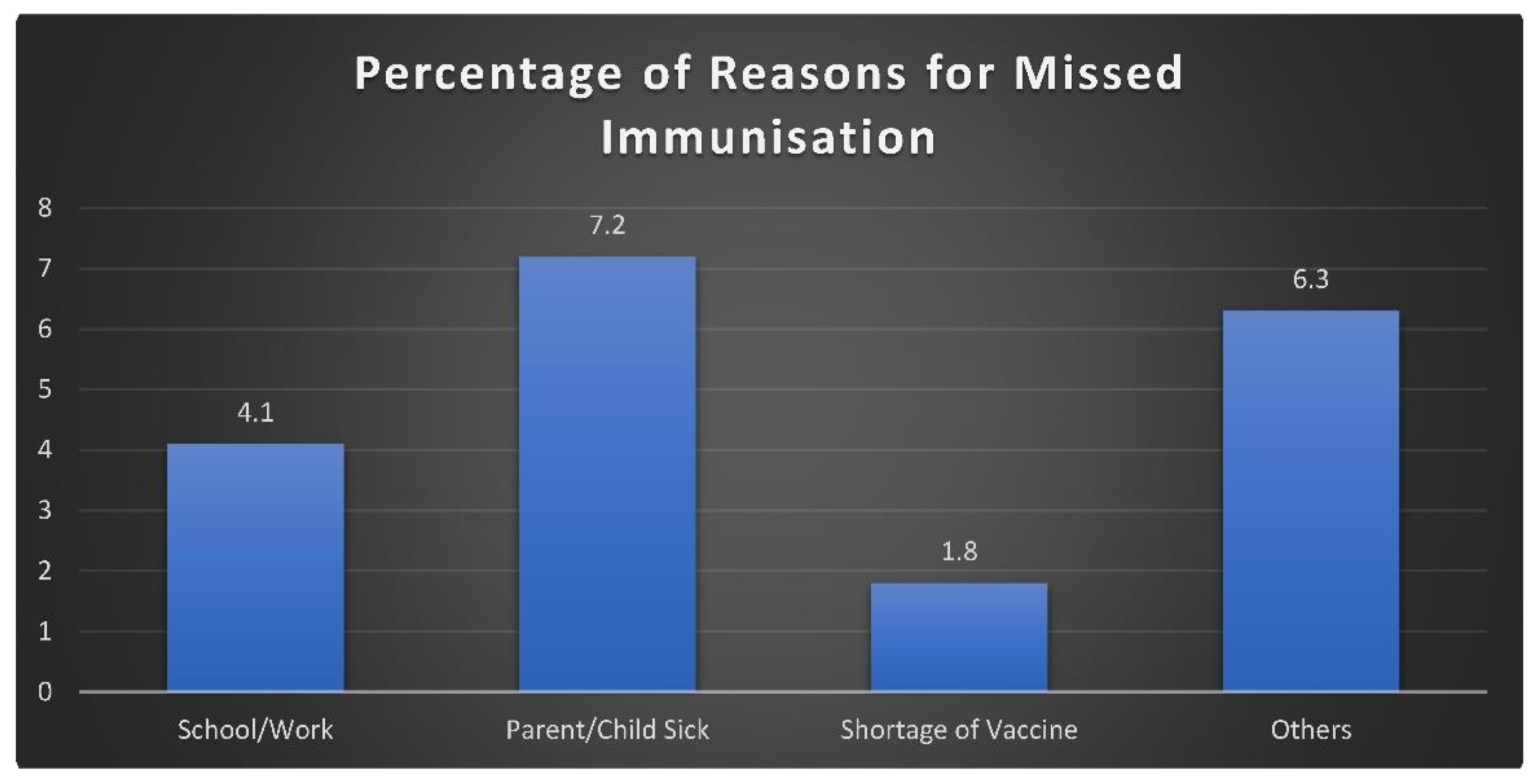

| Have you ever missed a scheduled immunisation for your child? | 22.1% | 77% |

| Have you ever been turned away because vaccines were unavailable? | 23% | 76.6% |

| Healthcare workers provide enough encouragement and education about childhood immunisation? | 69.4% | 30.6% |

| Do you feel the clinics enough support to help you access immunisation services? | 77.5% | 22.1% |

| Did you receive the date for the next visit? | 93.7% | 6.3% |

| Did you receive education about potential adverse reactions after vaccination? | 58.1% | 41.9% |

| Were you informed about the next visit by the healthcare worker? | 90.5% | 9.5% |

| Do the clinic’s operating hours fit your schedule for taking your child for immunisation? | 81.5% | 18.5% |

11. Discussion of Results

11.1. Sociodemographic Context

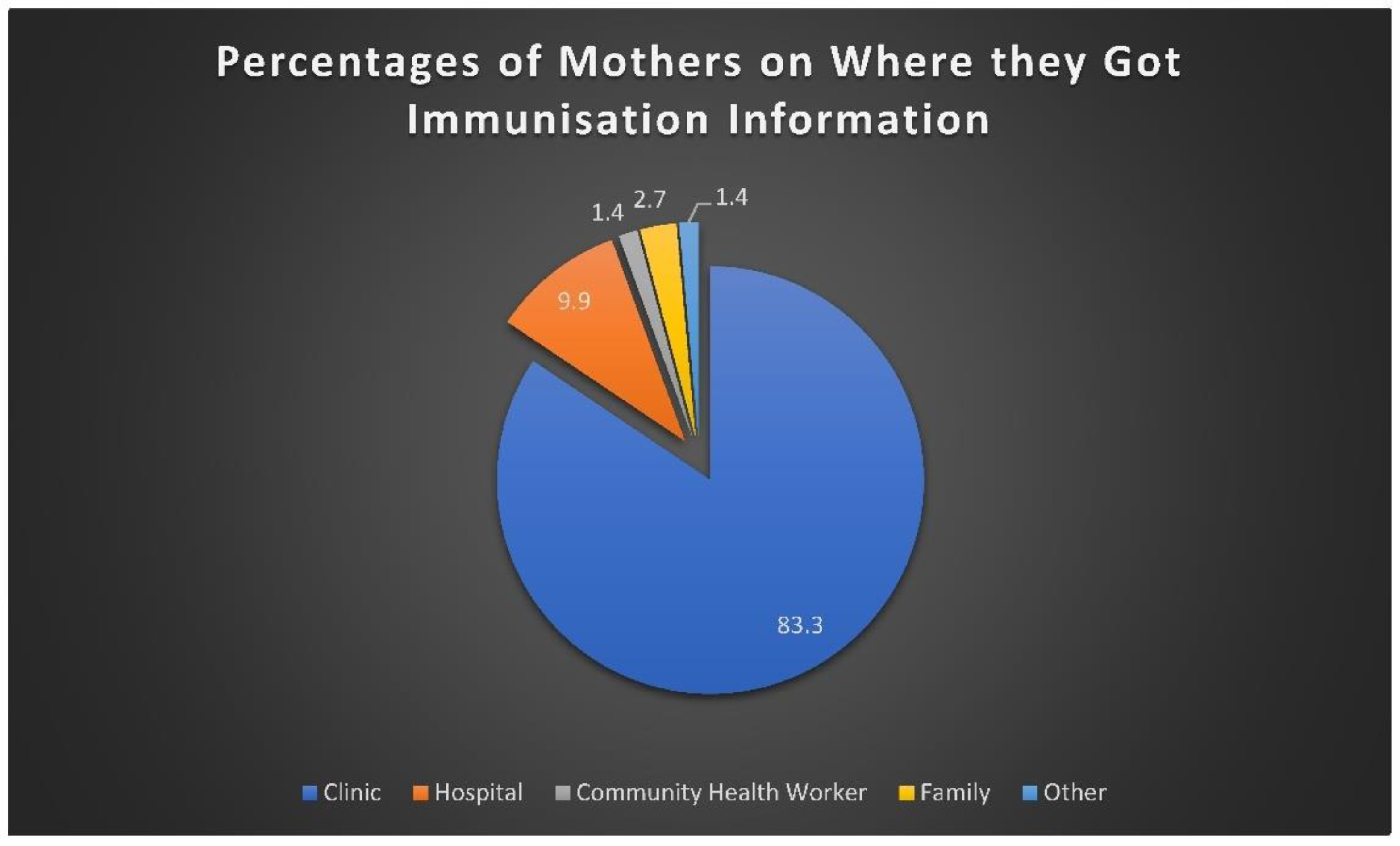

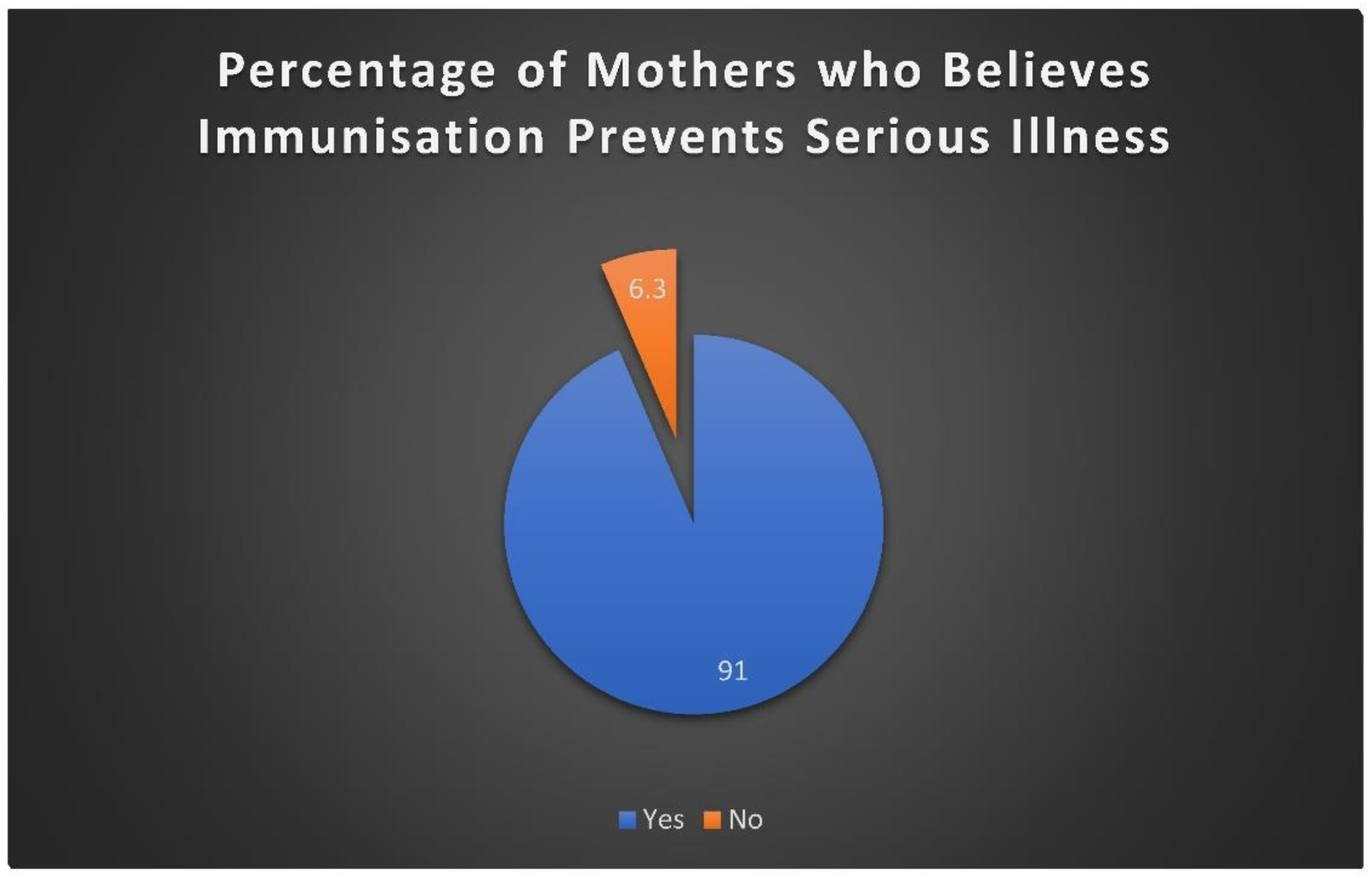

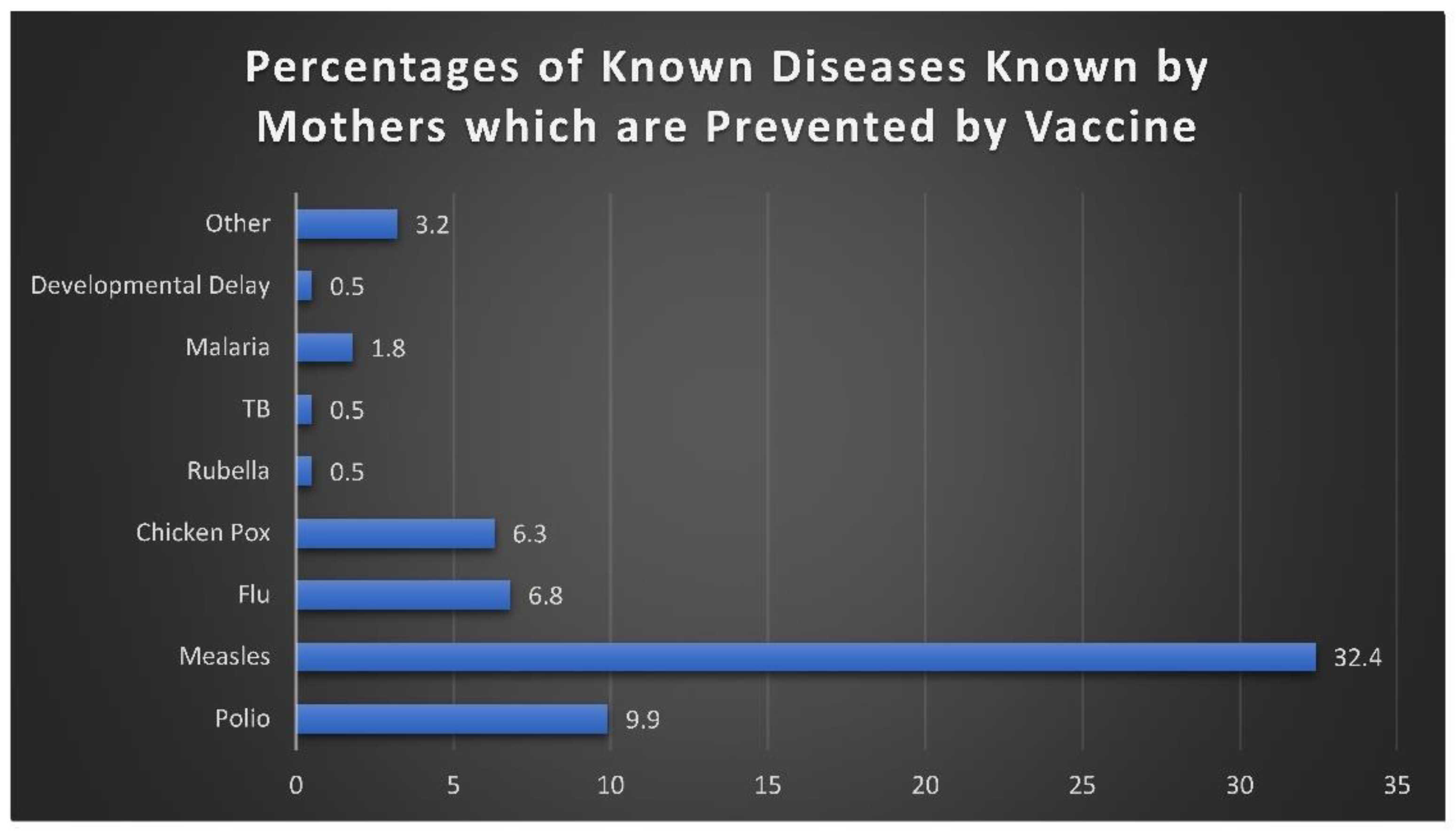

11.2. Awareness and Knowledge

11.3. Access and System Barriers

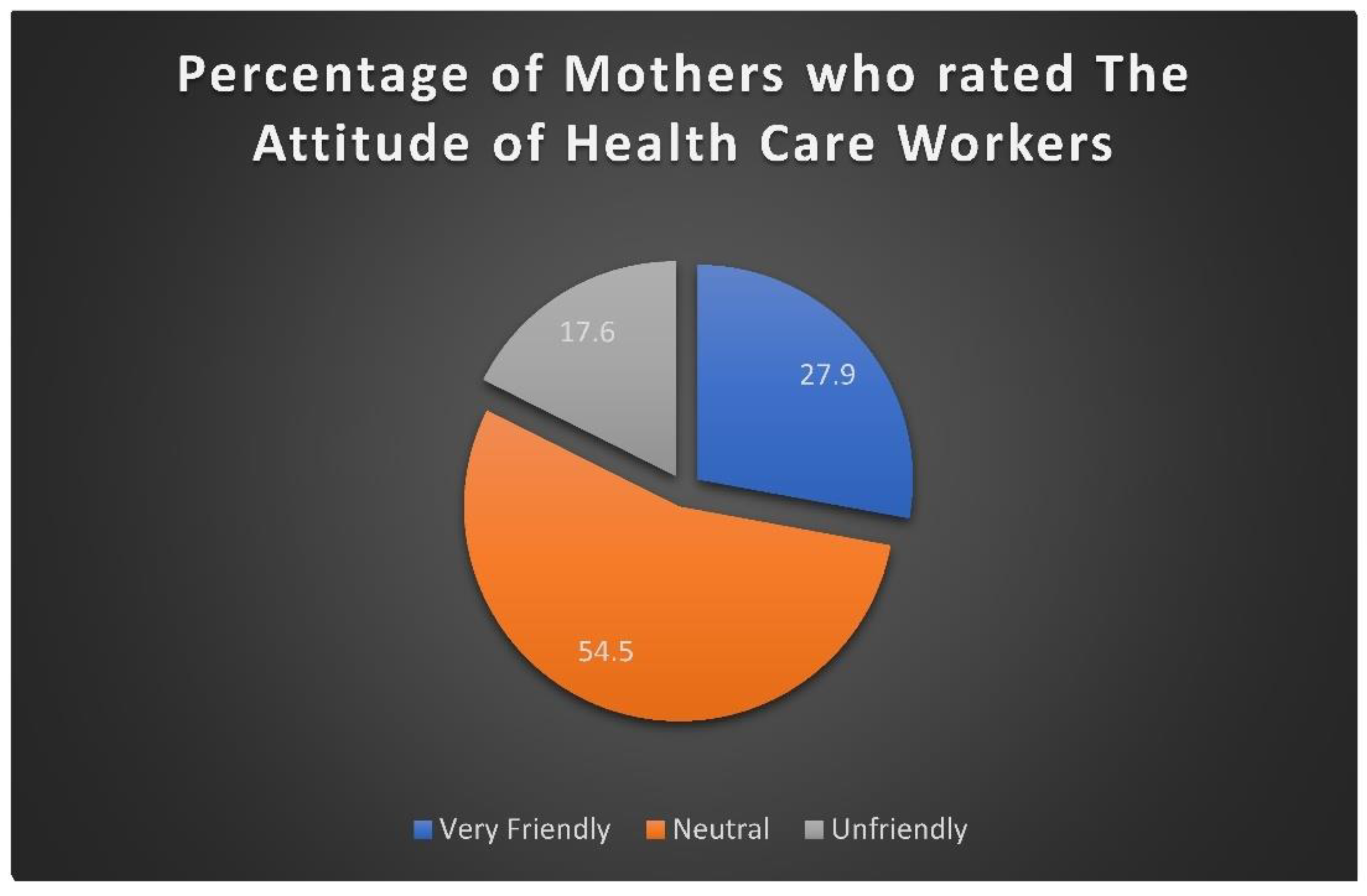

11.4. Service Delivery Experience

11.5. Policy and Programme Implications

11.6. Recommendations:

- Strengthen service efficiency: Reduce waiting times by introducing dedicated immunisation days, appointment systems, and improved patient flow management.

- Enhance communication and counselling: Standardise information delivery using simple language and pictorial materials to accommodate caregivers of varying literacy levels.

- Address logistical and resource constraints: Ensure reliable vaccine supply through strengthened inventory management and timely replenishment to prevent stock-outs and service disruptions.

- Expand outreach and community engagement: Mobilise community health workers to provide follow-up support and home-based reminders for missed immunisations, especially for working and low-income mothers.

- Improve staff–patient interaction: Conduct periodic training on interpersonal communication, empathy, and cultural sensitivity to improve caregiver satisfaction and trust.

- Integrate monitoring and evaluation systems: Use digital tracking and routine supervision to identify children who miss doses and follow up promptly, supporting EPI-SA’s data-driven performance improvement model.

12. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

- We would like to express our deepest gratitude to all those who contributed to the completion of this research project.

- First and foremost, we are sincerely thankful to our supervisors, [Ms Mushasha and Ms Shabangu], for their invaluable guidance, constructive feedback, and continuous support throughout the study.

- We extend our appreciation to the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University Department of Pharmacy for providing the resources and opportunity to conduct this research.

- Special thanks to Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital Out Paediatric Department for granting us the premises and their warm welcome during the research process, and all the participants who willingly took part in this study and shared their experiences.

Abbreviations

- EPI-SA - Expanded Programme Immunisation – South Africa

- HIC - High-Income Countries

- LMIC - Low and Middle-Income Countries

- OPD- Outpatient Department

- UNICEF - United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

- VPDs- Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

- WHO – World Health Organization

- SMUREC – Sefako Makgatho University Research Ethics Committee

Appendices

Appendix 1: TIME SCHEDULE

| ACTIVITY | JAN-FEB | MAR-MAY | JUN-AUG | SEP-OCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol compilation | X | |||

| Protocol submission | X | |||

| Pilot study | X | |||

| Data collection and analysis | X | |||

| Report compilation | X | |||

| Oral presentation and report submission | X |

Appendix 2: BUDGET

| BUDGET | COST |

|---|---|

| Printing of consent forms and questionnaires | R400 |

| Logistics | R400 |

| Statistician | R2500 |

| Total cost | R3300 |

Appendix 3: ENGLISH QUESTIONNAIRE

- CODE

- Do not write a name in the paper.

- Please answer all the questions with pen.

- Fill in the provided space.

- Circle the letters (e.g. A)

- Circle one or more answers provided, if applicable.

| SECTION A: DEMOGRAPHIC DATA | |

| QUESTIONS | ANSWERS |

| 1. Age of the mother | a. 18-25 Years b. 26-35 Years c. 36 and above |

| 2. Marital status | a. Single b. Married c. Divorced d. Widowed |

| 3. Education level | a. No formal education b. Primary c. Secondary d. Tertiary |

| 4. Employment status | a. Employed b. Unemployed c. Student d. Informal worker |

| 5. Household income | a. Low-income ( less than R6888.00 per month) b. Middle-income (R6890.00 to R48752.00 per month) c. High-income (R48753.00 and above per month) |

| 6. Number of children | ___ |

| 7. Age of youngest child | ___ months -----years |

| SECTION B: KNOWLEDGE AND AWARENESS OF IMMUNISATION | |

| 8. Have you heard of childhood immunisation before? |

a. Yes b. No |

| 9. Where do you get immunisation information? | a. Clinic b. Hospital c. Media d. Community Health Worker e. Family f. Other---------specify |

| 10. Do you know the recommended immunisation schedule for your child? | a. Yes b. No |

| 11. Do you believe immunisation prevents serious illnesses? | a. Yes b. No |

| 12. Name one disease prevented by vaccine/childhood immunisation | |

| 13. Have you received a vaccination booklet for your child? | a. Yes b. No |

| SECTION C: BARRIERS TO IMMUNISATION ACCESS | |

| 14. What challenges do you face when taking your child for immunisation? (Tick all that apply) a. Distance to the clinic is too far b. High transport costs c. Long waiting times at the clinic d. Unfriendly staff or healthcare workers e. Lack of information on when and where to go f. Vaccine shortages at the clinic g. Fear of side effects from vaccines h. Religious or cultural beliefs against vaccines i. Other (specify) ___ j. None |

|

| 15. Have you ever missed a scheduled immunisation for your child? | a. Yes b. No |

| 16. If the above answer is yes, what was the main reason for missing the vaccination? |

___ |

| 17. Financial constraints (e.g., transport costs,) have prevented me from accessing vaccination services. | a. Yes b. No c. Not applicable |

| SECTION D: PRIMARY HEALTHCARE FACILITY FACTORS, EXPERIENCE | |

| 18. How long do you typically wait at the clinic for immunisation services? | a. Less than 30 minutes b. 30 minutes – 1 hour c. More than 1 hour d. More than 3 hours |

| 19. How would you rate the attitude of healthcare workers? | a. Very friendly b. Neutral c. Unfriendly |

| 20. Have you ever been turned away because vaccines were unavailable? | a. Yes b. No |

| 21. Healthcare workers provide enough encouragement and education about childhood vaccination. | a. Yes b. No |

| 22. Do you feel the clinics provide enough support to help you access immunisation services? | a. Yes b. No |

| 23. Did you receive the date for the next visit? | a. Yes b. No |

| 24. Did you receive education about potential adverse reactions after vaccination? | a. Yes b. no |

| 25. Were you informed about the next visit by the healthcare worker? | a. Yes b. No |

| 26. Do the clinic’s operating hours fit your schedule for taking your child for immunization? | a. Yes b. No |

Appendix 4: SETWANA QUESTIONNAIRE

- KHOUTU

- Ditaelo

- Tsweetswee araba dipotso tsotlhe o dirisa pene.

- Tlatsa sebaka se se neetsweng.

- Tshwaya kgotsa kgabaganya mo sebakeng se se neetsweng.

- Tlhopha karabo e le nngwe kgotsa go feta e e neetsweng, fa go tlhokega.

- O se ka wa kwala leina mo pampiring ya dipotso.

| KAROLO A: DINTLHA TSA DEMOKRAFI | |

| DIPOTSO | DIKARABO |

| 1. Dingwaga tsa mme | ___ dingwaga |

| 2. Seemo sa lenyalo | a. Nosi b. Nyetse c. O tlhadilwe d. Motlholagadi |

| 3. Maemo a thuto | a. Ga ke na thuto ya semmuso ya Poraemari b. Sekontari c. Dithuto tsa Boraro |

| 4. Seemo sa tiro | a. O thapilwe b. Ga a bereke c. Moithuti d. Modiri yo o sa tlhomamang |

| 5. Lotseno lwa lelapa | a. Lotseno lo lo kwa tlase (R1030.00 kgotsa bobtlana kgwedi -R6889) b. Lotseno lo lo magareng (R6890.00 -R48752.00 ka kgwedi) c. Lotseno lo lo kwa godimo (R48753.00 le godimo ka kgwedi) |

| 6. Palo ya bana | ___ |

| 7. Dingwaga tsa ngwana yo mmotlana | ___ dikgwedi/dingwaga |

| KAROLO YA B: KITSO LE TEMOGO YA GO ENTA | |

| 8. A o kile wa utlwa ka go entiwa ga bana pele? |

a. Ee b. nnyaa |

| 9. O bona kae tshedimosetso ya go enta? |

a. Tleliniki b. Bookelo c. Bobegakgang d. Modiri wa Pholo wa Baagi e. Lelapa f. Tse dingwe-------------tlhalosa |

| 10. A o itse thulaganyo e e akanyediwang ya go enta ngwana wa gago? | a. Ee b. nnyaa |

| 11. A o dumela gore go enta go thibela malwetse a a masisi? | a. Ee b. nnyaa |

| 12. Naya bolwetse bo le bongwe jo bo thibelwang ke moento/go entiwa ga bana. |

------------------------------- |

| 13. A o amogetse bukana ya go enta ngwana wa gago? | a. Ee b. nnyaa |

| KAROLO C: DIKGORELO TSA GO FITLHELELA MOENTO | |

| 14. Ke dikgwetlho dife tse o kopanang le tsone fa o isa ngwana wa gago go ya go entiwa? (Tshwaya tsotlhe tse di maleba) | a. Sekgala go ya kwa tleleniking se kgakala thata b. Ditshenyegelo tse di kwa godimo tsa dipalangwa c. Dinako tse ditelele tsa go leta kwa tleleniki d. Badiri ba ba seng botsalano kgotsa badiri ba tlhokomelo ya boitekanelo e. Go tlhoka tshedimosetso ya gore o ka ya leng le kae f. Tlhaelo ya moento kwa tleleniki g. Poifo ya ditlamorago tsa mekento h. Ditumelo tsa bodumedi kgotsa tsa setso kgatlhanong le mekento nna. Tse dingwe (tlhalosa) ___ i. Epe |

| 15. A o kile wa foswa ke go entiwa go go rulagantsweng ga ngwana wa gago? | a. Ee b. Nnyaa |

| 16.Fa karabo e e fa godimo e le ee, lebaka le legolo la go tlhoka go enta e ne e le eng? | ___ |

| 17. Mathata a matlole (sekao, ditshenyegelo tsa dipalangwa,) a nkgoreletsa go fitlhelela ditirelo tsa go enta. | a. Ee b. nnyaa |

| KAROLO D: DINTLHA TSA MOTLHOKO TSA LEFELO LA TLHOKOMELO YA BOITEKANELO, BOITEMOGELO | |

| 18.O leta lobaka lo lo kana kang kwa tleliniki go bona ditirelo tsa go entiwa? | a. Ka fa tlase ga metsotso e le 30 b. Metsotso e le 30 – ura e le 1 c. Go feta ura e le 1 d. Diura di feta 3 |

| 19. O ka lekanya jang boikutlo jwa badiri ba tlhokomelo ya kalafi? | a. O botsalano thata b. Go se tseye letlhakore c. Ga a botsalano |

| 20. A o kile wa kgaphelwa thoko ka ntlha ya gore mekento e ne e seyo? | a. Ee b.Nnyaa |

| 21. Badiri ba tlhokomelo ya boitekanelo ba neelana ka thotloetso le thuto e e lekaneng ka ga go enta bana. | a. Ee b. Nnyaa |

| 22. A o ikutlwa gore tleleniki e go naya tshegetso e e lekaneng go go thusa go fitlhelela ditirelo tsa go enta? | a. Ee b. Nnyaa |

| 23. A o amogetse letlha la ketelo e e latelang? | a. Ee b. Nnyaa |

| 24. A o amogetse thuto ka ga diphetogo tse di ka nnang teng tse di sa siamang morago ga go enta? | a. Ee b. Nnyaa |

| 25. A o itsisitswe ka ketelo e e latelang ke modiri wa tlhokomelo ya boitekanelo? | a. Ee b. Nnyaa |

| 26. A diura tsa tiro tsa tleliniki di tshwanela thulaganyo ya gago ya go isa ngwana wa gago go ya go entiwa? | a. Ee b. Nnyaa |

Appendix 5: Request letter to conduct a research study

- To Whom It May Concern

- Subject: REQUEST FOR PERMISSION TO CONDUCT RESEARCH AT SELECTED TERTIARY HOSPITAL

- We are final-year pharmacy students from Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University. We are writing to you requesting permission to conduct our study exploring the challenges faced by mothers in accessing childhood vaccination services in South Africa.

- We would greatly appreciate your support and guidance in this matter. Please let us know if any additional information is required.

- Our contact details are as follows:

- Maranda Vhulenda: vhulenda169@gmail.com

- Chawane Tinyiko: tinyikochawane780@gmail.com

- Mphaphuli Hakhakhi: mphaphulihakhakhi60@gmail.com

-

Ndwa Lotavha: fnndwa@gmail.com

- Best Regards SMU Bpharm 4 students

Appendix 6: INFORMED CONSENT

| SEFAKO MAKGATHO HEALTH SCIENCES UNIVERSITY ENGLISH CONSENT FORM |

- Statement concerning participation in a Research Project

- Name of Study: Investigation of the challenges faced by mothers in accessing childhood immunisation services at the academic hospital in Gauteng, South Africa

- I have read the information on the aims and objectives of the proposed study and was provided the opportunity to ask questions and given adequate time to rethink the issue. The aim and objectives of the study are sufficiently clear to me. I have not been pressurized to participate in any way.

- I am aware that am going to complete the questionnaire. I am aware that this material may be used in scientific publications which will be electronically available throughout the world. I consent to this provided that my name / and identity number are not revealed.

- I understand that participation in this study is completely voluntary and that I may withdraw from it at any time and without supplying reasons. I know that this Study has been approved by the Sefako Makgatho University Research Ethics Committee (SMUREC). I am fully aware that the results of this Study will be used for scientific purposes and may be published. I agree to this, provided my privacy is guaranteed.

- I hereby give consent to participate in this Study.

- ............................................................ …………………………………………

- Name of Respondent Signature of Respondent

- ...................................... ....................................... .......................................

- Place Date Witness

- ___________________________________________________________________

- Statement by the Researcher

- I provided verbal written information regarding this Study.

- I agree to answer any future questions concerning the Study as best as I am able.

- I will adhere to the approved protocol.

- .................................... ................................. ......................... ......................................

- Name of Researcher Signature Date Place

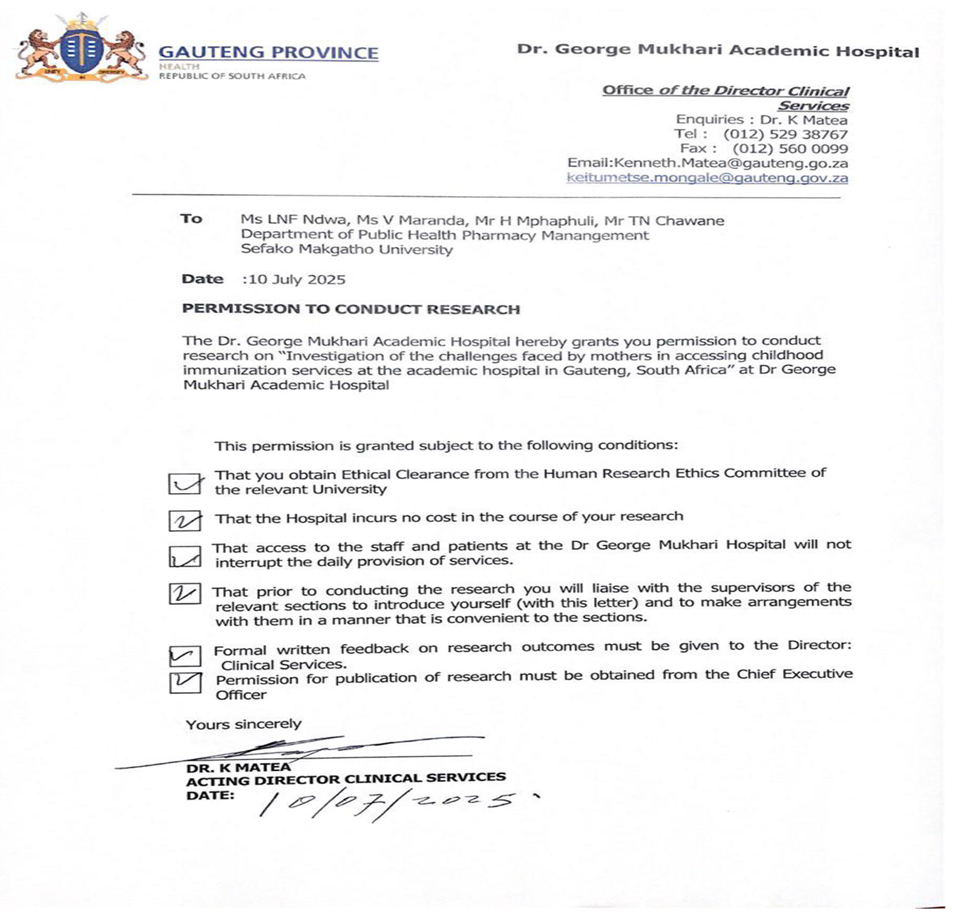

Appendix 7: GEORGE MUKHARI’S APPROVAL LETTER

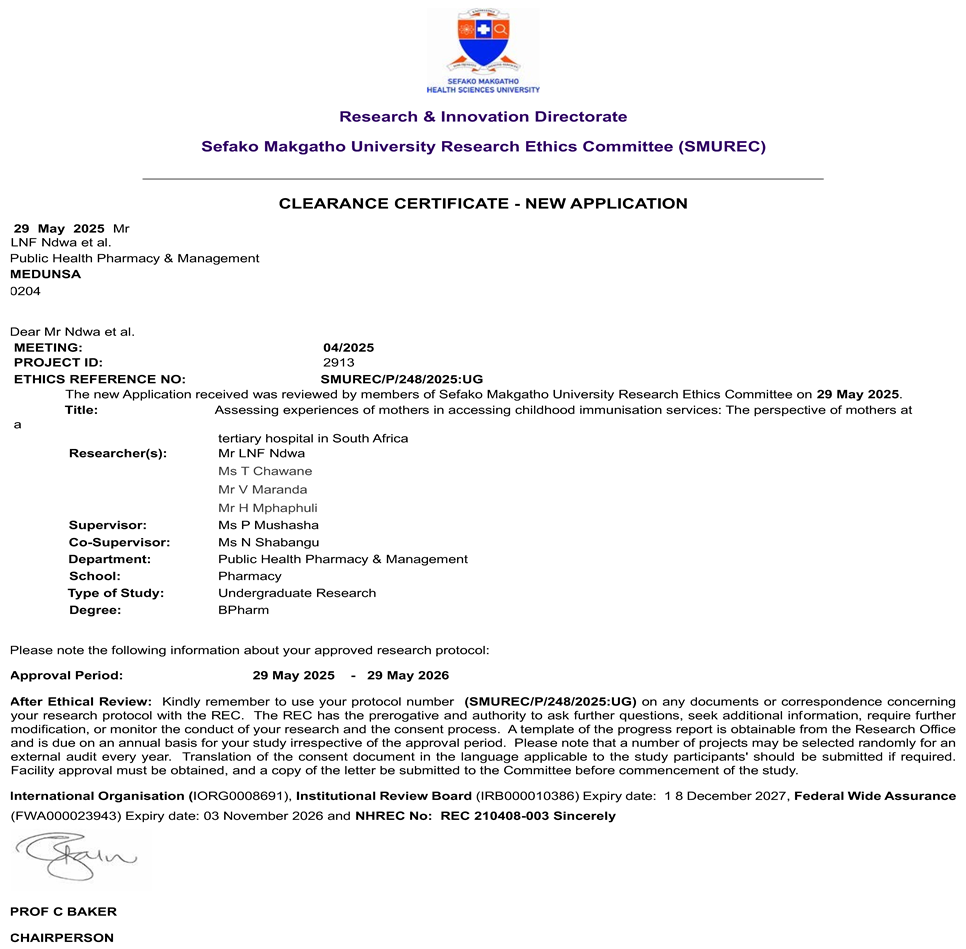

Appendix 8: SMU SCHOOL OF PHARMACY APPROVAL LETTER

References

- Wiysonge, C.S., Abdullahi, L.H. and Kagina, B.M. (2023) Improving healthcare worker attitudes and communication to strengthen immunisation uptake in Africa, Vaccine, 41(12), pp. 2025–2032.

- Acheampong, S., Lowane, M.P. and Fernandes, L., 2023. Experiences of migrant mothers attending vaccination services at primary healthcare facilities. Health SA Gesondheid, 28(1). [CrossRef]

- Albers, A.N., Thaker, J. and Newcomer, S.R., 2022. Barriers to and facilitators of early childhood immunization in rural areas of the United States: A systematic review of the literature. Preventive medicine reports, 27, pp.101804. [CrossRef]

- Ames, H.M., Glenton, C. and Lewin, S., 2017. Parents’ and informal caregivers’ views and experiences of communication about routine childhood vaccination: a synthesis of qualitative evidence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2). [CrossRef]

- Bangura, J.B., Xiao, S., Qiu, D., Ouyang, F. and Chen, L., 2020. Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC public health, 20, pp.1-15. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P., 2019. Types of sampling in research. Journal of the Practice of Cardiovascular Sciences, 5(3), pp.157-163. [CrossRef]

- Burnett, J.M., Myende, N., Africa, A., Kamupira, M., Sharkey, A., Simon-Meyer, J., Bamford, L., Guo, S. and Padarath, A., 2024. Barriers to Childhood Immunisation and Local Strategies in Four Districts in South Africa: A qualitative study. Vaccines, 12(9), p.1035. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Zunino, F., Hester, K.A., Keskinocak, P., Nazzal, D., Smalley, H.K. and Freeman, M.C., 2025. Associations between family planning, healthcare access, and female education and vaccination among under-immunized children. Vaccine, 44, p.126540. [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo, A., Temfack, E., Tajudeen, R. and Larson, H.J., 2023. Declining trends in vaccine confidence across sub-Saharan Africa: A large-scale cross-sectional modeling study. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 19(1), p.2213117. [CrossRef]

- DiResta, R. and Wardle, C., 2020. Online misinformation about vaccines. The Sabin-Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group.

- Dimitrova, A., Carrasco-Escobar, G., Richardson, R. and Benmarhnia, T., 2023. Essential childhood immunization in 43 low- and middle-income countries: Analysis of spatial trends and socioeconomic inequalities in vaccine coverage. PLoS Medicine, 20(1), p.e1004166. [CrossRef]

- Oduwole, E.O., Esterhuizen, T.M., Mahomed, H. and Wiysonge, C.S., 2021. Estimating vaccine confidence levels among healthcare staff and students of a tertiary institution in South Africa. Vaccines, 9(11), p.1246. [CrossRef]

- Fikadu, T., Gebru, Z., Abebe, G., Tesfaye, S. and Zeleke, E.A., 2024. Assessment of mothers’ satisfaction towards child vaccination service in South Omo zone, South Ethiopia region: a survey on clients’ perspective. BMC Women’s Health, 24(1), p.272. [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, L.R., Ogokeh, C., Rha, B., Weinberg, G.A., Staat, M.A., Selvarangan, R., Halasa, N.B., Englund, J.A., Boom, J.A., Azimi, P.H. and Szilagyi, P.G., 2021. Vaccine effectiveness against influenza hospitalization among children in the United States, 2015–2016. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, 10(2), pp.75-82. [CrossRef]

- Forshaw, J., Gerver, S.M., Gill, M., Cooper, E., Manikam, L. and Ward, H., 2017. The global effect of maternal education on complete childhood vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases, 17, pp.1-16. [CrossRef]

- Gust, D.A., Darling, N., Kennedy, A. and Schwartz, B., 2023. Parental perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs regarding vaccination of children: a qualitative study. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 19(1), p.2233398. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21645515.2023.2233398. Accessed: 27 February 2025.

- Hasan, M.M., Gharami, T. and Akter, H., 2025. Mothers’ Perception about Immunization of Children in Bangladesh. International Journal of Nursing and Health Services (IJNHS), 8(1), pp.35-47. [CrossRef]

- Kasting, M. L., & Zikmund-Fisher, B. J. 2021. Vaccine decision-making: The role of perceived benefits and barriers. In Vaccination Policy and Global Health. Springer.

- Kaufman, J., Hoq, M., Rhodes, A.L., Measey, M.A. and Danchin, M.H., 2024. Misperceptions about routine childhood vaccination among parents in Australia, before and after the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey study. Medical Journal of Australia, 220(10), pp.530-532. [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, G., 2024. Childhood immunisation: Global rates remain below pre-pandemic levels.

- Machingaidze, S. & Wiysonge, C.S., 2021. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nature Medicine, 27(8), pp.1338-1339.

- Machado, A.A., Edwards, S.A., Mueller, M. and Saini, V., 2021. Effective interventions to increase routine childhood immunization coverage in low socioeconomic status communities in developed countries: A systematic review and critical appraisal of peer-reviewed literature. Vaccine, 39(22), pp.2938-2964. [CrossRef]

- Makamba-Mutevedzi, P.C., Madhi, S. and Burnett, R., 2020. Republic of South Africa Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) national coverage survey report. Pretoria, South Africa.

- Maphumulo, W.T. & Bhengu, B.R., 2019. Challenges of quality improvement in the healthcare of South Africa post-apartheid: A critical review. Curationis, 42(1), pp.1-9. [CrossRef]

- Mavundza, E.J., Cooper, S. and Wiysonge, C.S., 2023. A Systematic Review of Factors That Influence Parents’ Views and Practices around Routine Childhood Vaccination in Africa: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Vaccines, 11(3), pp.563. [CrossRef]

- Mbonigaba, E., Nderu, D., Chen, S., Denkinger, C., Geldsetzer, P., McMahon, S. and Bärnighausen, T., 2021. Childhood vaccine uptake in Africa: threats, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of Global Health Reports, 5, pp.e2021080. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A. and Shet, A., 2020. Why vaccines matter: understanding the broader health, economic, and child development benefits of routine vaccination. Human vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 16(8), pp.1900-1904. [CrossRef]

- Ndwandwe, D., Nnaji, C.A., Mashunye, T., Uthman, O.A. and Wiysonge, C.S., 2021. Incomplete vaccination and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in South Africa: An analysis of the South African demographic and health survey 2016. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 17(1), pp.247-254. [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, V. & Daniels, J., 2020. Socioeconomic barriers to healthcare access in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), pp.1-10.

- Orhierhor, M., Rubincam, C., Greyson, D. and Bettinger, J.A., 2023. New mothers’ key questions about child vaccinations from pregnancy through toddlerhood: evidence from a qualitative longitudinal study in Victoria, British, Columbia. SSM-Qualitative Research in Health, 3, p.100229. [CrossRef]

- Raosoft, Inc. 2004 Raosoft Sample Size Calculator. Available at: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html. Accessed: 3 February 2025.

- Rodrigues, C.M. and Plotkin, S.A., 2020. Impact of vaccines; health, economic and social perspectives. Frontiers in microbiology, 11, p.1526. [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, T., Mthembu, Z. and Sibanda, M. 2024. Factors influencing caregiver satisfaction with immunisation services in primary health care clinics in South Africa, African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 16(1), 4203.

- Galadima, E., Kawuwa, H., Emmanuel, E., Mirzoev, T., Musani, M. & Odusanya, O. (2021) ‘Factors influencing childhood immunisation uptake in Africa: a systematic review’, BMC Public Health, 21: 1475. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF (2023) State of the World’s Children 2023: For Every Child, Vaccination. New York: UNICEF.

- Ogunleye, O.O., Mthembu, Z. and Sibanda, M. 2021 Improving vaccination services in Africa: addressing system inefficiencies and barriers to access, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4212.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2023) Primary Health Care and Immunization: Integration and Efficiency Report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Samad, L., Tate, A.R., Dezateux, C., Peckham, C. and Butler, N., 2017. Ethnicity-specific factors influencing childhood immunisation uptake in an urban district of the UK: a qualitative study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 71(6), pp.544-549. Available at: https://jech.bmj.com/content/71/6/544. Accessed: 26 February 2025.

- Thomas, S., Paden, V., Lloyd, C., Tudball, J. and Corben, P., 2022. Tailoring immunisation programs in Lismore, New South Wales-we want our children to be healthy and grow well, and immunisation helps. Rural and Remote Health, 22(1), pp.1-9. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization 2019. ’Immunization coverage’, WHO Fact Sheets. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage (Accessed: 31 January 2025).

- World Health Organization 2020 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Herd immunity, lockdowns and COVID-19. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/herd-immunity-lockdowns-and-covid-19 (Accessed; 26 March 2025).

- World Health Organization 2023. ’World Immunization Week 2023: 24 to 30 April’, WHO Events. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/04/24/default-calendar/world-immunization-week-2023 (Accessed: 31 January 2025).

- World Health Organization 2024. ’World Immunization Week 2024’, WHO Campaigns. Available at: https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-immunization-week/2024 (Accessed: 31 January 2025).

- CDC. 2024. Reasons to Vaccinate - CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines-children/reasons/index.html. Accessed 27 February 2025.

- UNICEF (2023) State of the World’s Children 2023: For Every Child, Vaccination. New York: UNICEF.

- Department of Health (DoH). 2021. Expanded Programme on Immunisation in South Africa (EPI-SA): Policy and Implementation Guidelines. Pretoria: National Department of Health.

- National Department of Health (NDoH). (2019). Annual Health Performance Report 2018/2019. Pretoria: Government of South Africa.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).