Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

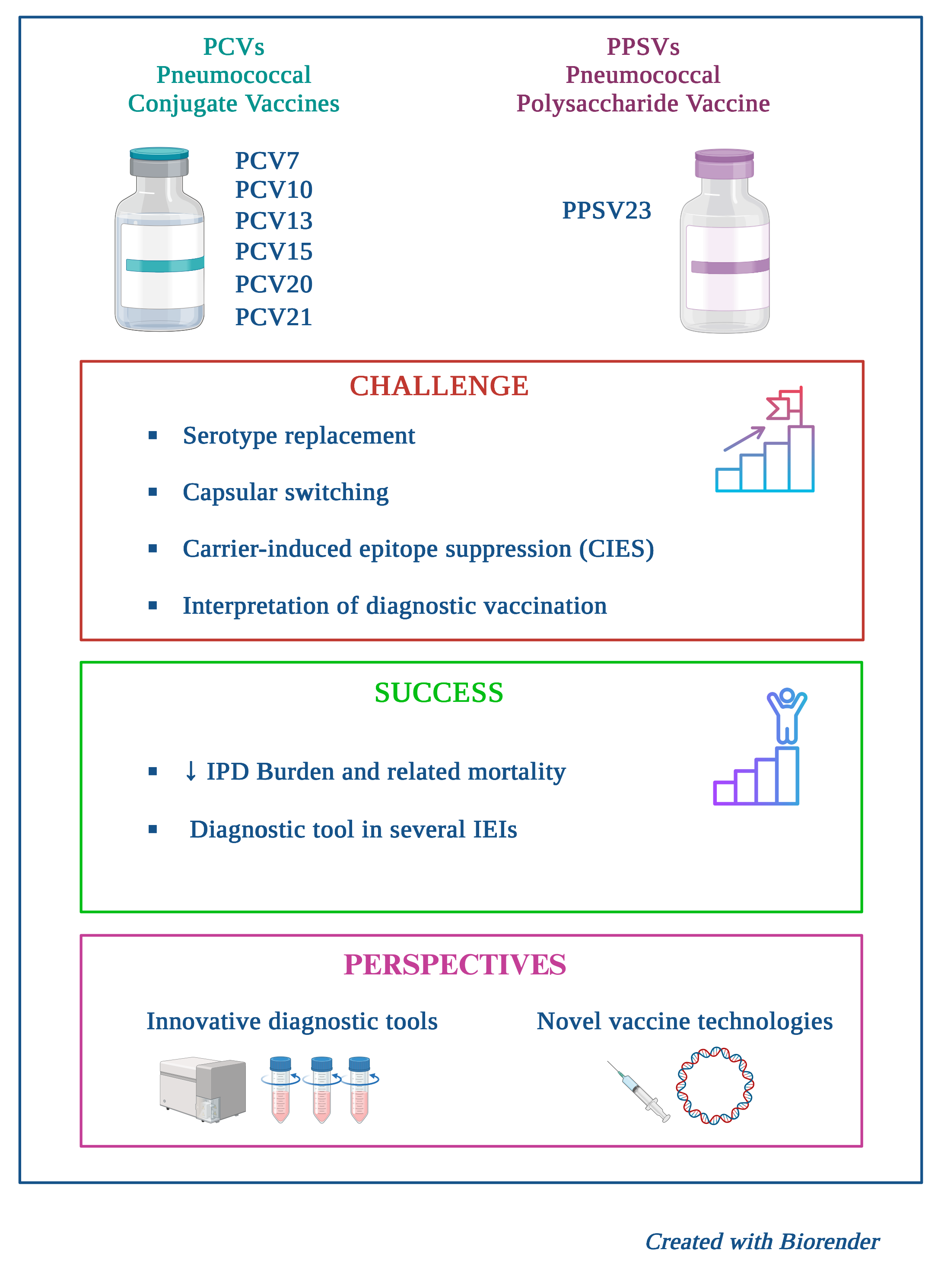

Streptococcus pneumoniae contributes significantly to morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs worldwide due to severe Invasive Pneumococcal Disease (IPD), particularly among young children and vulnerable populations. This review critically examines the current state of pneumococcal disease epidemiology, the evolution of vaccine strategies, and persistent challenges to achieve global control of the disease. The implementation of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines (PCVs) has yielded substantial public health gains, establishing herd immunity and sharply reducing vaccine-type IPD incidence. However, this success has been fundamentally challenged by serotype replacement, where non-vaccine serotypes have subsequently emerged to cause a significant proportion of the residual disease burden. This epidemiological shift has necessitated the development and deployment of higher-valency PCVs (PCV15, PCV20, and PCV21) to expand serotype coverage. Furthermore, optimal protection requires personalized strategies for high-risk cohorts where vaccine effectiveness can be compromised. In this context, the review details how pneumococcal vaccination - and particularly PPSV23 - serves as an indispensable diagnostic tool to evaluate a broad spectrum of Inborn Errors of Immunity (IEI) and in particular humoral defects. Diagnostic challenges are strained by non-standardized assays and the limited panel of unique serotypes available for testing in the PCV era. The scientific priority is now the development of universal protein-based vaccines, to provide protection against all serotypes and non-encapsulated strains by targeting conserved virulence factors. This integrated approach, combining expanded PCV coverage with novel vaccine technology, is essential to mitigate the ongoing public health burden of pneumococcal disease.

Keywords:

1. Burden of Pneumococcal Disease in Children

1.1. Epidemiology of Different Serotypes in Both High-Income and Low- and Middle-Income Countries

2. Available Pneumococcal Vaccines and Their Limitations

3. Pneumococcal Vaccines in the Vulnerable

3.1. Patients with Chronic Diseases

3.2. Immunocompromised Populations

3.3. Rationale for Vaccinating Immunocompromised Children: The Dual Role of Prevention and Diagnosis in Primary Immunodeficiencies

Preventive Role

Diagnostic Role

3.4. Personalized Vaccine Schedules in Secondary Immunodeficiencies: Optimizing the Immunological Window

4. Future Perspectives and Implications for Clinical Practice and Public Health

4.1. Impact of PCV Vaccination on Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance

4.2. Importance of Emergent Serotype Identification to Develop New Vaccine Formulations

4.3. Protein Candidates for a Universal Pneumococcal Vaccine

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPD | Invasive Pneumococcal Disease |

| PCVs | Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines |

| CPs | capsular polysaccharides |

| CAP | community-acquired pneumonia |

| AOM | acute otitis media |

| SAARC | South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation |

| PD | Pneumococcal disease |

| NHICs | non-high-income countries |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| US | United States |

| PPSVs | pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines |

| NVTs | non-vaccine serotypes |

| NIPs | national immunization programs |

| RR | risk ratio |

| ACIP | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices |

| CIES | carrier-induced epitope suppression |

| CF | cystic fibrosis |

| PID | Primary Immunodeficiencies |

| SID | Secondary Immunodeficiencies |

| AAAAI | American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology |

| PRP | Polysaccharide Responsiveness Percentile |

| IEI | Inborn Errors of Immunity |

| IGRT | Immunoglobulin Replacement Therapy |

| AMR | antimicrobial resistance |

| VT | vaccine-type |

| PSPs | pneumococcal surface proteins |

| CBPs | Choline-Binding Proteins |

| CBD | choline-binding domain |

| PspA | Pneumococcal Surface Protein A |

| PspC | Pneumococcal Surface Protein C |

| PHTS | Histidine Triad Proteins |

| EV | extracellular vesicle |

| RV | Reverse Vaccinology |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| APDS | Activated PI3K δ Syndrome |

References

- Narciso AR, Dookie R, Nannapaneni P, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. Streptococcus pneumoniae epidemiology, pathogenesis and control. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2025, 23, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiser JN, Ferreira DM, Paton JC. Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018, 16, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izurieta, Patricia, Mohammad AbdelGhany, and Dorota Borys. "Serotype distribution of invasive and non-invasive pneumococcal disease in children≤ 5 years of age following the introduction of 10-and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in infant national immunization programs: a systematic literature review." Frontiers in Public Health 2025, 13, 1544359.

- Cui, Yadong A. , et al. "Pneumococcal serotype distribution: a snapshot of recent data in pediatric and adult populations around the world." Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2017, 13, 1229–1241.

- Jaiswal, Nishant, et al. "Distribution of serotypes, vaccine coverage, and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Streptococcus pneumoniae in children living in SAARC countries: a systematic review." PloS one 2014, 9, e108617.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Invasive pneumococcal disease - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/invasive-pneumococcal-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2022.

- Weaver, Jessica, et al. "Incidence of pneumococcal disease in children in Germany, 2014–2019: a retrospective cohort study." BMC pediatrics 2024, 24, 755.

- Kolhapure, Shafi, et al. "Invasive Pneumococcal Disease burden and PCV coverage in children under five in Southeast Asia: implications for India." The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries 2021, 15, 749–760.

- Kaur, Ravinder, Matthew Morris, and Michael E. Pichichero. "Epidemiology of acute otitis media in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era." Pediatrics 2017, 140.

- Huang, Min, et al. "Global assessment of health utilities associated with pneumococcal disease in children—targeted literature reviews." PharmacoEconomics 2025, 1-45.

- Syeed, M. Sakil, et al. "Pneumococcal vaccination in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cost-effectiveness studies." Value in Health 2023, 26, 598–611. [Google Scholar]

- Laferriere, C. The immunogenicity of pneumococcal polysaccharides in infants and children: a meta-regression. Vaccine. 2011, 29, 6838–6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao WQ, Shen N, Yu PX, Liu BB, He B. Efficacy of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in preventing community-acquired pneumonia among immunocompetent adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Vaccine. 2016, 34, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto K, Masuda S. Pneumococcal vaccines for prevention of adult pneumonia. Respir Investig. 2025, 63, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloria Knoll, Maria, et al. "Global landscape review of serotype-specific invasive pneumococcal disease surveillance among countries using PCV10/13: the pneumococcal serotype replacement and distribution estimation (PSERENADE) project." Microorganisms 2021, 9, 742.

- Horn, Emily K. , et al. "Public health impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination: a review of measurement challenges." Expert Review of Vaccines 2021, 20, 1291–1309.

- Wahl, Brian, et al. "Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15." The Lancet Global Health 2018, 6, e744–e757.

- Chapman, Ruth, et al. "Ten year public health impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in infants: a modelling analysis." Vaccine 2020, 38, 7138–7145.

- Platt HL, Cardona JF, Haranaka M, Schwartz HI, Perez SN, Dowell A, et al. A phase 3 trial of safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114, 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, compared with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults 50 years of age and older (PNEU-AGE). Vaccine. 2022, 40, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamprasertchai T, Ruenroengbun N, Kajeekul R. Immunogenicity and safety of the higher-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine vs the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Infect Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf069. [Google Scholar]

- Klein NP, Peyrani P, Yacisin K, Caldwell N, Xu X, Scully IL, et al. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of 3 lots of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults 18 through 49 years of age. Vaccine. 2021, 39, 5428–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari RF, Fadilah F, Maladan Y, Sarassari R, Safari D. A narrative review of genomic characteristics, serotype, immunogenicity, and vaccine development of Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2024, 13, 91–104.

- Gopalakrishnan S, Jayapal P, John J. Pneumococcal surface proteins as targets for next-generation vaccines: Addressing the challenges of serotype variation. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2025, 113, 116870. [Google Scholar]

- Du Q-q, Shi W, Yu D, Yao K-h. Epidemiology of non-vaccine serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae before and after universal administration of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021, 17, 5628–5637 ;

- Sempere J, Llamosí M, López Ruiz B, et al. Effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines and SARS-CoV-2 on antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes with reduced susceptibility in Spain, 2004–2020: a national surveillance study. [Article in press]. J Infect.

- Naucler P, et al. Chronic disease and immunosuppression increase the risk for nonvaccine serotype pneumococcal disease: a nationwide population-based study. Clin Infect Dis. 2022, 74, 1338–1349.

- Silverii, GA; et al. Diabetes as a risk factor for pneumococcal disease and severe related outcomes and efficacy/effectiveness of vaccination in diabetic population. Results from meta-analysis of observational studies. Acta Diabetol. 2024, 61, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Riccio M, Boccalini S, Cosma C, et al. Effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination on hospitalization and death in the adult and older adult diabetic population: a systematic review. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2023, 22, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAP-EXPO Expert Panel. Expert panel opinion on adult pneumococcal vaccination in the post-COVID era. PMC.

- Masson, A; et al. Vaccine coverage in CF children: A French multicenter study. J Cyst Fibros. 2015, 14, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yırgın K, Gür E, Erener-Ercan T, Can G. Vaccination Status in Children with Chronic Diseases: Are They Up-to-Date for Mandatory and Specific Vaccines? Turk Arch Pediatr. 2023, 58, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, J. Browning, et al. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine responses are impaired in a subgroup of children with cystic fibrosis, Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2014, 13.

- ACIP (CDC). Pneumococcal Vaccine for Adults Aged ≥19 Years: Recommendations. MMWR Recomm Rep.

- CDC ACIP. Expanded Recommendations for Use of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines Among Adults Aged ≥50 Years (PCV15/PCV20). MMWR.

- Bhardwaj P, Dhar R, Khullar D, Rath P, Swaminathan S, Tiwaskar M, Kulkarni N, Choudhari S, Taur S. Role of Pneumococcal Vaccination as a Preventative Measure for At-risk and High-risk Adults: An Indian Narrative. J Assoc Physicians India. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Aalst M, Lötsch F, Spijker R, van der Meer JTM, Langendam MW, Goorhuis A, Grobusch MP, de Bree GJ. Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in immunocompromised patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2018, 24, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orange JS, Ballow M, Stiehm ER, Ballas ZK, Chinen J, De La Morena M, Kumararatne D, Harville TO, Hesterberg P, Koleilat M, McGhee S, Perez EE, Raasch J, Scherzer R, Schroeder H, Seroogy C, Huissoon A, Sorensen RU, Katial R. Use and interpretation of diagnostic vaccination in primary immunodeficiency: a working group report of the Basic and Clinical Immunology Interest Section of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Warmerdam J, Campigotto A, Bitnun A, MacDougall G, Kirby-Allen M, Papsin B, McGeer A, Allen U, Morris SK. Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in High-risk Children: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2023, 42, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingels H, Schejbel L, Lundstedt AC, Jensen L, Laursen IA, Ryder LP, Heegaard NH, Konradsen H, Christensen JJ, Heilmann C, Marquart HV. Immunodeficiency among children with recurrent invasive pneumococcal disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015, 34, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gaschignard J, Levy C, Chrabieh M, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children can reveal a primary immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 2014, 59, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bertran M, Abdullahi F, D'Aeth JC, et al. Recurrent invasive pneumococcal disease in children: A retrospective cohort study, England, 2006/07-2017/18. J Infect. 2025, 90, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins A, Bahuaud M, Hentzien M, et al. The 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Elicits Serological Response and Lasting Protection in Selected Patients With Primary Humoral Immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 697128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peterson, LK. Application of vaccine response in the evaluation of patients with suspected B-cell immunodeficiency: Assessment of responses and challenges with interpretation. J Immunol Methods. 2022, 510, 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasshauer M, Dinges S, Staudacher O, Völler M, Stittrich A, von Bernuth H, Wahn V, Krüger R. Monogenic Inborn Errors of Immunity with impaired IgG response to polysaccharide antigens but normal IgG levels and normal IgG response to protein antigens. Front Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1386959. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fogsgaard SF, Todaro S, Larsen CS, Jørgensen CS, Jensen JMB. Reassessing Polysaccharide Responsiveness: Unveiling Limitations of Current Guidelines and Introducing the Polysaccharide Responsiveness Percentile Approach. J Clin Immunol. 2025, 45, 115. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ameratunga R, Longhurst H, Leung E, Steele R, Lehnert K, Woon ST. Limitations in the clinical utility of vaccine challenge responses in the evaluation of primary antibody deficiency including Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders. Clin Immunol. 2024, 266, 110320. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuzolo J, Zulfiqar MF, Spoelhof B, Revell R, Patrie JT, Borish L, Lawrence MG. Functional testing of humoral immunity in the Prevnar 20 era. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2025, 134, 279–283. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parker AR, Park MA, Harding S, Abraham RS. The total IgM, IgA and IgG antibody responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination (Pneumovax®23) in a healthy adult population and patients diagnosed with primary immunodeficiencies. Vaccine. 2019 Feb 28, 37, 1350-1355. [CrossRef]

- Martire B, Ottaviano G, Sangerardi M, Sgrulletti M, Chini L, Dellepiane RM, Montin D, Rizzo C, Pignata C, Marseglia GL, Moschese V. Vaccinations in Children and Adolescents Treated With Immune-Modifying Biologics: Update and Current Developments. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022, 10, 1485–1496. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dendle C, Stuart RL, Mulley WR, Holdsworth SR. Pneumococcal vaccination in adult solid organ transplant recipients: a review of current evidence. Vaccine 2018, 36, 6253–6261. [CrossRef]

- Froneman, C.; Kelleher, P.; José, R.J. Pneumococcal Vaccination in Immunocompromised Hosts: An Update. Vaccines 2021, 9, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heuvel L, Caini S, Dückers MLA, Paget J. Assessment of the inclusion of vaccination as an intervention to reduce antimicrobial resistance in AMR national action plans: a global review. Glob Health. 2022, 18, 85.

- Yemeke T, Chen H-H, Ozawa S. Economic and cost-effectiveness aspects of vaccines in combating antibiotic resistance. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023, 19, 2215149.

- Ozawa S, Chen H-H, Rao GG, Eguale T, Stringer A. Value of pneumococcal vaccination in controlling the development of antimicrobial resistance (AMR): Case study using DREAMR in Ethiopia. Vaccine. 2021, 39, 6700–6711.

- Candeias C, Almeida ST, Paulo AC, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage, serotypes, genotypes, and antimicrobial resistance trends among children in Portugal, after introduction of PCV13 in National Immunization Program: A cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2024, 42, 126219.

- Peela SCM, Sistla S, Nagaraj G, Govindan V, Kadahalli RK. Pre- & post-vaccine trends in pneumococcal serotypes & antimicrobial resistance patterns. Indian J Med Res. 2024, 160, 354–361.

- Løchen, Alessandra, Nicholas J. Croucher, and Roy M. Anderson. "Divergent serotype replacement trends and increasing diversity in pneumococcal disease in high income settings reduce the benefit of expanding vaccine valency." Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 18977;

- Balsells, Evelyn, et al. "The relative invasive disease potential of Streptococcus pneumoniae among children after PCV introduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis." Journal of Infection 2018, 77, 368–378.

- Grant, Lindsay R. , et al. "Distribution of serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in children from high-income countries and the impact of pediatric pneumococcal vaccination." Clinical Infectious Diseases 2023, 76, e1062–e1070.

- Grant LR, Hanquet G, Sepúlveda-Pachón IT, et al. Effects of PCV10 and PCV13 on pneumococcal serotype 6C disease, carriage, and antimicrobial resistance. Vaccine. 2024, 42, 2983–2993.

- Brooks WA, Chang L-J, Sheng X, Hopfer R. Safety and immunogenicity of a trivalent recombinant PcpA, PhtD, and PlyD1 pneumococcal protein vaccine in adults, toddlers, and infants: a phase I randomized controlled study. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4610–4617. [CrossRef]

- Salod Z, Mahomed O. Mapping Potential Vaccine Candidates Predicted by VaxiJen for Different Viral Pathogens between 2017-2021-A Scoping Review. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 1785. [CrossRef]

- Parveen S, Subramanian K. Emerging roles of extracellular vesicles in pneumococcal infections: immunomodulators to potential novel vaccine candidates. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 836070. [CrossRef]

| Type |

Adjuvant | Protein carrier | Serotypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPSV23 | None | None, polysaccharide | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F, and 33F |

| PCV10 | Aluminium phosphate | Non-toxic diphtheria CRM197 |

1, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 19A, 19F and 23F |

| PCV13 | Aluminium phosphate | Non-toxic diphtheria CRM197 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F and 23F |

| PCV15 | Aluminium phosphate | Non-toxic diphtheria CRM197 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, 22F, 23F and 33F |

| PCV20 | Aluminium phosphate | Non-toxic diphtheria CRM197 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 8, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 18C, 19A, 19F, 22F, 23F and 33F |

| PCV21 | none | Non-toxic diphtheria CRM197 | 3, 6A, 7F, 19A, 22F, 33F, 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, 9N, 17F, 20, 15A, 15C, 16F, 23A, 23B, 24F, 31, and 35B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).