1. Introduction

Lamellar keratoplasty has revolutionized corneal transplantation by offering a selective, tissue-sparing approach to restore vision. Among its techniques, Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), introduced by Melles et al. in 2006, has emerged as a gold standard for treating endothelial dysfunction while preserving overall corneal architecture [

1]. Within the last decade, DMEK has gained widespread acceptance and now accounts for about 70% of all keratoplasties and 98% of posterior lamellar keratoplasties in Germany[

2]. Its adoption has contributed to a doubling of the annual number of corneal transplants performed nationwide.[

3].

Despite its clinical advantages, including faster visual recovery, lower rejection rates, and improved optical outcomes, DMEK also carries procedure specific risks. One of the most significant early complications is elevation of intraocular pressure (IOP), which, if left untreated, can compromise graft survival and can lead to iris and optic nerve head damage. Elevated IOP has been associated with endothelial cell loss in both experimental and clinical settings, with reports of up to 33% of endothelial cell loss in patients experiencing pressures as high as 55 mmHg[

4]. The most feared cause of acute IOP elevation after DMEK is a pupillary block, which results from mechanical obstruction of aqueous outflow by the gas tamponade used to attach the graft[

5]. To prevent such complications, most surgical protocols include a prophylactic peripheral iridotomy or a surgical iridectomy, most commonly at the six o’clock position[

6]. Nevertheless, postoperative IOP elevation may still occur due to other factors such as overfilling of the anterior chamber, too high concentration of sulfur hexafluoride (SF

6) in the endotamponade, preexisting glaucoma, or impaired aqueous outflow. In these cases, timely intervention—such as decompression via venting, pharmacologic IOP reduction, or revision of the iridotomy or iridectomy—is critical.

In our department, a standardized postoperative protocol includes early assessment of anterior chamber gas fill and IOP at the slit lamp at three hours following surgery, allowing for immediate intervention, if needed. This structured approach facilitates prompt detection of IOP elevation and rapid initiation of treatment.

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence of early postoperative IOP elevation in a recent cohort of DMEK patients, to characterize the interventions employed, and to evaluate their short-term outcomes. By analysing real-world postoperative management in a standardized clinical setting, we aim to contribute to the optimization of early post-DMEK care and the prevention of graft-threatening complications.

2. Material and Methods

A retrospective electronic chart review was conducted for all consecutive patients, who underwent DMEK at the Department of Ophthalmology, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, between May and December 2024. According to local law (‘Landeskrankenhausgesetz’ §36, §37), no ethical approval was required for this retrospective review.

2.1. Eye Banking and DMEK Graft Preparation

Eye banking and DMEK graft preparation was performed at our institution’s standard of care[

7]. In brief, the donor corneas have been obtained and stored in the Eye Bank of Rhineland-Palatinate. All donor corneas have been stored in Dextran-free medium 1 (Cat-No. F-9016; Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) at 34° Celsius and were transferred into dextran-containing medium 2 (Cat-No. F-9017; Biochrom) 24 hours prior to graft preparation. Medium 2 is supplemented with 60 g Dextran 500 per 1000 ml as opposed to medium 1. Both media 1 and 2 were supplemented with gamma-irradiated fetal calf serum 10% (No. S0415, Biochrom).

The Descemet endothelial complexes (DEC) were prepared using the stripping technique on the day before or on the same day as DMEK by two experienced surgeons. To avoid an upside-down orientation all grafts were marked with a technique described elsewhere[

8].

2.2. DMEK Surgery

DMEK procedures were performed under general or topical anaesthesia by two experienced corneal surgeons. All surgeries included a surgical peripheral iridectomy at the 6 o’clock position and tamponade with a standardized mixture of 90% air and 10% SF₆. Most of the Descemet endothelial complexes (DECs) had a diameter of 8.0-8.5 mm. The descemetorhexis was performed within an area of 8.0–8.5 mm depending on the size of the graft using an irrigation Descemet hook (G-38601, Geuder AG, Heidelberg, Germany) and an irrigation Descemet scraper (G38602, Geuder AG, Heidelberg, Germany). The single-use DMEK-cartridge (G-38635, Geuder AG, Heidelberg, Germany) was used to insert the graft into the anterior chamber. The graft was unfolded by gentle tapping of the cornea. The positioning of the graft was checked by the orientation of the mark, which was visible in all cases. In case of an upside-down positioning, the graft was flipped over with a flush of balanced salt solution, and the position was checked again. An 90% air / 10% SF6 bubble was injected underneath the graft as soon as the proper orientation and centration was achieved. The paracenteses were not sutured.

At the end of surgery, the palpatory assessed IOP was approximately 10 to 15 mmHg and anterior chamber was not overfilled with air/gas. All patients were instructed to remain in a strict supine position for three hours postoperatively and more loosely for several days until gas resorption.

If DMEK was combined with cataract surgery (triple-DMEK), phacoemulsification and implantation of a monofocal hydrophobic intraocular lens were performed first. After pharmacological pupil constriction with acetylcholine, the DMEK procedure was carried out as described above.

2.3. Postoperative Evaluation and IOP-Lowering Interventions

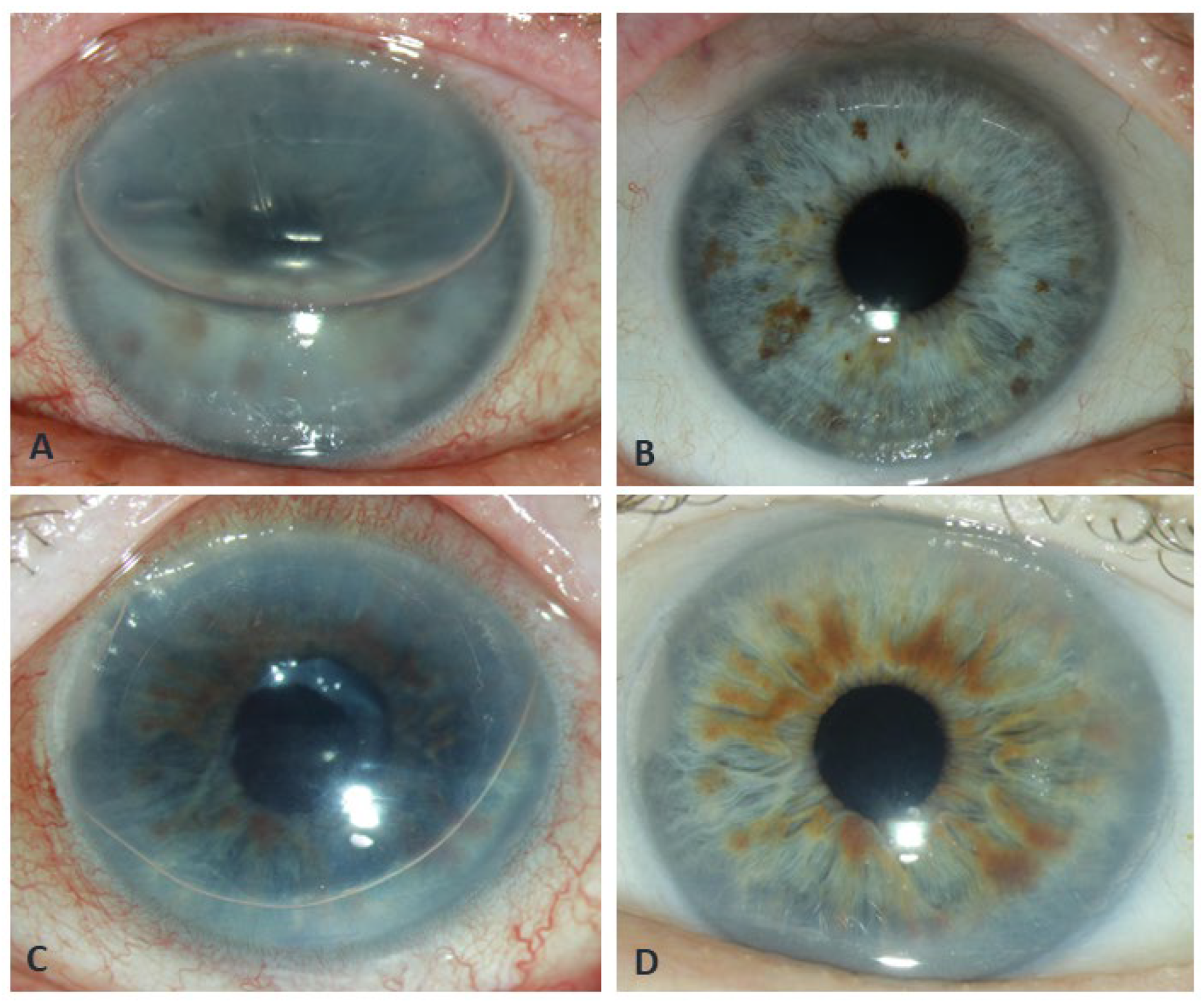

Initial postoperative evaluation was performed at three hours following surgery and included slit-lamp examination, Goldmann applanation tonometry (Haag-Streit, Koeniz, Switzerland), and assessment of anterior chamber gas fill. Further IOP and gas fill measurements were conducted at 24 and 48 hours postoperatively (

Figure 1). The decision to perform IOP-lowering interventions at the 3-hour-follow-up was made by the on-call ophthalmology resident, based on clinical judgment and IOP readings.

Possible IOP-lowering interventions included the following. Venting, which involves opening one of the paracenteses to reduce gas fill, was performed in cases with elevated IOP, greater than 90% gas fill, and/or suspected angle closure or pupillary block. Intravenous or oral acetazolamide was administered in cases of moderate IOP elevation with a lower gas fill and a patent iridectomy. In situations where the response to a single intervention was insufficient, a combined approach was employed.

As this was a real-life observation rather than a prospective study protocol, decisions regarding IOP-lowering interventions were subjective and based on the individual experience of the residents.

2.4. Outcomes

Primary outcomes included the incidence and type of IOP-lowering intervention, changes in IOP and anterior chamber gas fill over time, and postoperative complications such as re-bubbling or graft failure. Subgroup analyses compared:

DMEK-only vs. triple-DMEK and eyes with and without preexisting glaucoma

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data management and statistical analyses were performed in Stata software, version 16.0 (Stata Corp LP). Quantitative values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student’s t-tests or Mann-Whitney-U Test were used for comparisons as appropriate. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

A total of 116 eyes from 98 patients were included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 73.0 ± 9.8 years, and 62 of the patients were female. The most common indication for DMEK was Fuchs' endothelial corneal dystrophy, accounting for 102 eyes. Additional indications included pseudophakic bullous keratopathy in seven eyes, past herpes simplex virus-related endotheliitis in two eyes, uveitis in one eye, iridocorneal endothelial syndrome in one eye, previous penetrating keratoplasty in one eye, and a history of complicated glaucoma surgery in two eyes.

DMEK was performed in combination with cataract surgery (triple-DMEK) in 41 eyes, while four eyes underwent phakic DMEK without lens removal. In all other cases the eyes were pseudophakic.

All procedures were uneventful, with no cases of upside-down DEC positioning based on the orientation mark. The peripheral iridectomy at the 6 o’clock position remained patent in all eyes, and no pupillary block or angle closure was observed postoperatively

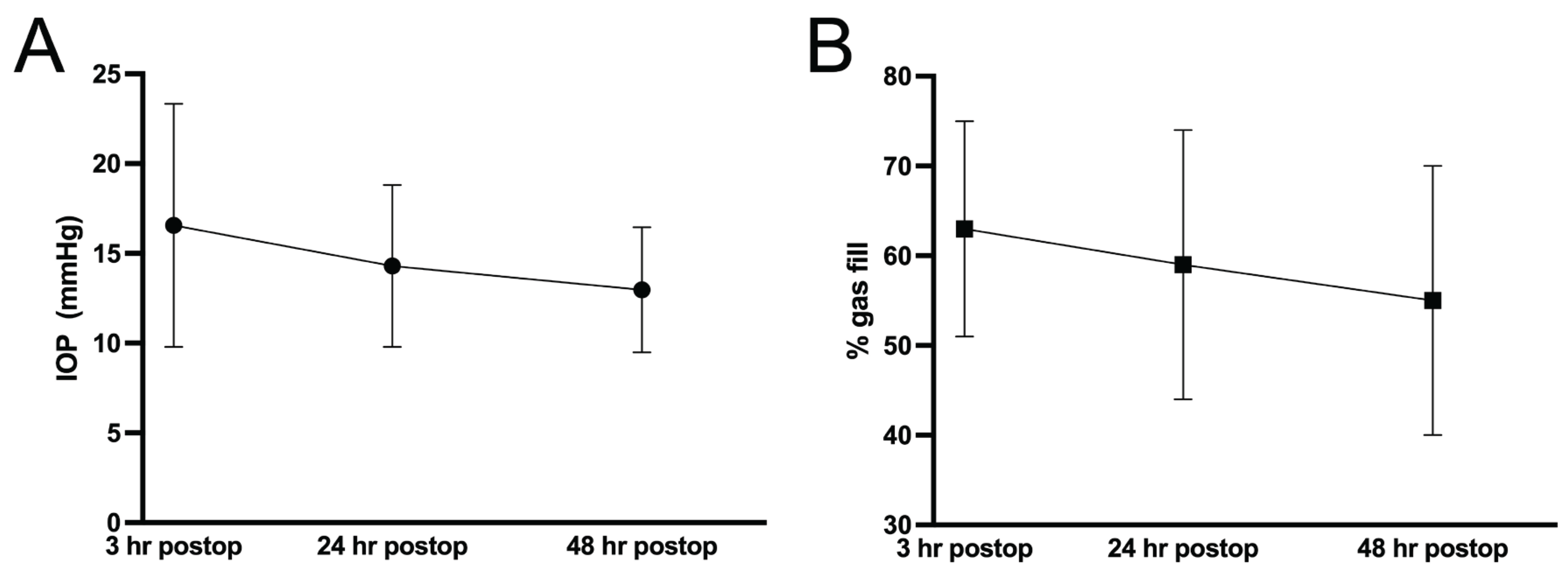

3.1. Postoperative IOP and Gas Fill

Mean IOP and anterior chamber gas fill were recorded at three time points postoperatively. At 3 hours, the mean IOP was 16.6 ± 6.8 mmHg, and the mean gas fill was 63 ± 12%. At 24 hours, the mean IOP had decreased to 14.3 ± 4.5 mmHg, and gas fill was 59 ± 15%. At 48 hours, the mean IOP further declined to 13.0 ± 3.5 mmHg, and gas fill was measured at 55 ± 15% (

Figure 2).

3.2. IOP-Lowering Interventions

Intraocular pressure-lowering interventions were performed in 11 eyes, representing 9.5% of the total cohort. Among these, venting was performed in three eyes (#1 to #3) systemic acetazolamide was administered in seven eyes (#5 to #11), and one eye received both treatments (#4). Characteristics of the eyes that received IOP-lowering interventions, as well as the corresponding time points (3 or 24 hours postoperatively), are presented in

Table 1. Four of the 11 eyes that required intervention had a known history of glaucoma or glaucoma surgery. No complications were reported in association with the IOP-lowering interventions.

Re-bubbling procedures were necessary in twelve eyes (10.3%), including one with a previous venting manoeuvre (#1). Two cases of primary graft failure were recorded during the postoperative period (1.7%). No urgent surgical re-intervention was required, and all other cases proceeded without severe complications.

3.3. DMEK vs. Triple-DMEK

We did not observe any significant differences between patients, who underwent DMEK alone (n = 74) and those who received triple-DMEK (n = 41) in terms of postoperative gas fill, IOP, or the need for IOP-lowering interventions. Mean gas fill at 3, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively was nearly identical between groups: at 3 hours, 63 ± 0.14% (DMEK) vs. 63 ± 0.09% (triple-DMEK), p = 0.99; at 24 hours, 59 ± 0.17% vs. 58 ± 0.11%, p = 0.67; and at 48 hours, 55 ± 0.17% vs. 56 ± 0.12%, p = 0.60. IOP values followed a similar trend with no significant differences: at 3 hours, 16.65 ± 7.79 mmHg (DMEK) vs. 16.51 ± 4.65 mmHg (triple-DMEK), p = 0.92; at 24 hours, 14.73 ± 5.29 mmHg vs. 13.58 ± 2.57 mmHg, p = 0.21; and at 48 hours, 13.10 ± 3.85 mmHg vs. 12.74 ± 2.90 mmHg, p = 0.62. The need for venting was low in both groups, occurring in 4 patients (5%) in the DMEK-alone group and in none of the triple-DMEK patients (p = 0.13). Similarly, acetazolamide was used in 6 patients (8.1%) in the DMEK group compared to 1 patient (2.4%) in the triple DMEK group (p = 0.16).

3.4. Glaucoma vs. Non-Glaucoma

When comparing eyes with preexisting glaucoma (n = 16) to those without glaucoma (n = 100), several significant differences were observed in postoperative outcomes. Although the frequency of venting was low in both groups — 3% in the non-glaucoma group and 6.25% in the glaucoma group — the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.51). However, acetazolamide use was significantly more frequent among glaucoma patients (31%) compared to those without glaucoma (3%), p = 0.001, indicating a greater need for pharmacologic IOP management in this group. IOP was also significantly higher in the glaucoma group at later time points: at 3 hours, IOP was 16.87 ± 6.86 mmHg (no glaucoma) vs. 15.00 ± 6.59 mmHg (glaucoma), p = 0.33; at 24 hours, 13.92 ± 3.77 mmHg vs. 17.07 ± 7.40 mmHg, p = 0.012; and at 48 hours, 12.65 ± 3.33 mmHg vs. 14.86 ± 4.13 mmHg, p = 0.029. In terms of gas fill, glaucoma patients had significantly lower fill at 3 hours (55 ± 17%) compared to those without glaucoma (64 ± 11%), p = 0.011, although differences at 24 and 48 hours were not statistically significant: 60 ± 15% vs. 55 ± 18% (p = 0.26) and 56 ± 15% vs. 50% ± 18 (p = 0.24), respectively. These findings suggest that patients with preexisting glaucoma may experience higher postoperative IOP, require more frequent IOP-lowering intervention.

4. Discussion

Successful DMEK outcomes rely on a graft with high-quality and high-density endothelial cells, a smooth and precise surgical procedure with minimal manipulation, and adequate postoperative management. IOP elevation in the early postoperative phase is one of the graft- and vision-threatening complications [

9]. Ophthalmic surgeons apply different strategies to prevent and manage this issue [

10]. In this retrospective study, we analyzed our standardized approach, which includes a surgical iridectomy at the 6 o’clock position, the use of 10% SF₆ as an endotamponade, and a low-normal intraocular pressure of approximately 15 mmHg at the end of surgery. Furthermore, all patients undergo their first postoperative assessment—including IOP measurement, gas fill evaluation, and iridectomy patency check—as early as three hours after surgery, followed by additional evaluations on the first and second postoperative day.

We observed a stable mean IOP of 16.6 mmHg at the 3-hour follow-up in both DMEK and triple-DMEK patients, with a smooth decline in IOP over the first two postoperative days. No cases of pupillary block or angle closure were noted. IOP was slightly higher in glaucoma patients compared to non-glaucoma patients on the first and second postoperative days, but not at the 3-hour follow-up. This may be attributed to the perioperative interruption of their IOP-lowering medication. Maier et al. reported pre-existing glaucoma to elevate the risk of post-DMEK IOP elevation [

11].

The mean gas fill was 63% at the 3-hour follow-up and gradually declined to 55% by the second postoperative day. Similar to IOP, no differences were observed between DMEK and triple-DMEK patients. Gas fill was slightly lower in the glaucoma group compared to the non-glaucoma group at the 3-hour follow-up, but this difference was not significant on the following two postoperative days.

The primary outcome of our study was the frequency and type of IOP-lowering procedures following DMEK. As this was not a prospective trial but a real-life observation, the decision regarding the necessity and type of IOP-lowering intervention was made by the resident on duty—particularly during the 3-hour follow-up in the afternoon. According to this assessment, IOP-lowering interventions were performed in 11 eyes (9.5% of the total cohort) during the 3- or 24-hour follow-up. Venting only was performed in three eyes, systemic acetazolamide was administered in seven eyes, and one eye received both treatments. In two cases, venting was performed at the 3-hour follow-up due to IOP levels of 45–50 mmHg and a gas fill of 95–100%. In two additional eyes, venting was performed at the 24-hour follow-up due to IOP levels of 25–30 mmHg and gas fill of 90–100%, although the gas fill at the 3-hour follow-up had already been 90–95% with IOPs of 12 and 31 mmHg, respectively.

Acetazolamide was administered in two patients at the 3-hour follow-up for IOPs of 20 mmHg (in a patient with known glaucoma) and 24 mmHg, with gas fills of 65% and 60%, respectively. At the 24-hour follow-up, five patients received acetazolamide due to IOP levels of 28–30 mmHg and gas fills of 45–65%.

From a clinical perspective, the decision to perform venting in patients #1, #2, #3 and #4 was justified, given the combination of elevated IOP and high gas fill. In contrast, the use of acetazolamide in patients #5 to #11 was based on a “soft” indication and could likely have been managed without any intervention and without negative consequences for the patients. On the other hand, a certain level of awareness—especially among glaucoma patients—is recommended, and it is not a mistake to act with some caution. Nevertheless, these patients required more frequent IOP-lowering interventions than non-glaucoma patients.

In contrast to other reports, we did not find triple DMEK as a significant risk factor for intervention after DMEK9.

The fear of releasing all the gas from the anterior chamber and causing DMEK graft detachment should not prevent, especially younger residents, from responding promptly in cases of pupillary block, which poses a threat not only to the graft but also to the optic nerve — not to mention the significant discomfort experienced by the patient. In such cases, venting is the fastest option for lowering intraocular pressure, regardless of whether the gas is located in the anterior or posterior chamber. This method is incomparably more effective than lowering the pressure with systemic or topical medications. Likewise, reopening a small or closed iridectomy with a laser takes more time, involves more manipulation, and is not always feasible in the presence of epithelial edema.

In our study, we did not observe any cases of pupillary block or angle closure. Only two patients presented with an IOP of 45–50 mmHg and a gas fill of 95–100%, requiring venting within the first 3 hours postoperatively (1.72%). We believe that a combination of surgical iridectomy at the 6 o’clock position, an SF₆ concentration not exceeding 10% in the endotamponade, and a low-normal IOP at the end of surgery may be key to maintaining stable postoperative IOP after DMEK. In accordance with Stanzel et al. our data suggests that IOP elevation after DMEK can be effectively controlled within a few hours after surgery [

12].

Surgical iridectomy has been shown to be more effective than laser iridotomy in the study by Steindor et al.[

13], and the use of SF₆ in the endotamponade, which remains in the anterior chamber longer than air, appears to reduce the need for re-bubbling compared to 100% air [

14]. On the other hand, too high concentration of SF₆ can lead to a rapid increase in IOP due to its expansion within the first hours. Based on our experience, a 10% concentration of SF₆ provides a sufficient tamponade duration while minimizing the risk of pressure spikes.

Our re-bubbling rate was 10.3%, which is low compared to the rates reported in the literature, typically ranging from 10% to 30% [

15,

16]. One of these patients required re-bubbling after venting, as there was no residual gas fill as early as 48 hours after DMEK.

Limitations of our study include its retrospective design and the absence of standardized criteria guiding the decision and selection of IOP-lowering interventions. However, the use of standardized criteria would likely result in an even lower rate of IOP-lowering interventions than observed in this study.

5. Conclusions

Each patient may respond differently to surgery, and individual risk factors for complications—such as pupillary block—can vary. To prevent severe IOP elevation or pupillary block after DMEK, precise surgical technique and meticulous postoperative management are essential. In our standardized approach, which includes a surgical iridectomy at the 6 o’clock position, the use of 10% SF₆ gas, and ensuring a low-normal IOP at the end of surgery, no cases of pupillary block occurred in 116 consecutive DMEK procedures. Only two eyes exhibited both elevated IOP and high gas fill at the 3-hour follow-up, necessitating a reduction of the endotamponade via venting. Same-day standardized postoperative assessments help raise awareness among both practitioners and patients, facilitating early detection and management of potential complications.

References

- (Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(2):222-7.

- Report of the Cornea Section of the German Ophthalmological Society. Berlin 2025.

- (Flockerzi E et al Br J Ophthalmol. 2024.

- (Exp Eye Res. 2003;76(6):671-7, Ophthalmology. 1982;89(6):596-9.

- Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1950:88-106.

- Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2012;229(6):615-20, Eye (Lond). 2023;37(16):3492-5.

- Schön F, Gericke A, Bu JB, Apel M, Poplawski A, Schuster AK, Pfeiffer N, Wasielica-Poslednik J. How to Predict the Suitability for Corneal Donorship? J Clin Med. 2021 Jul 31;10(15):3426. [CrossRef]

- Wasielica-Poslednik J, Schuster AK, Rauch L, Glaner J, Musayeva A, Riedl JC, Pfeiffer N, Gericke A. How to Avoid an Upside-Down Orientation of the Graft during Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty? J Ophthalmol. 2019 Aug 4;2019:7813482. eCollection 2019. [CrossRef]

- Alio JL, Montesel A, El Sayyad F, et al. Corneal graft failure: an update. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(8):1049–58. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez A, Price FW, Jr., Price MO, Feng MT. Prevention and Management of Pupil Block After Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea. 2016;35(11):1391-5. [CrossRef]

- Maier AB, Pilger D, Gundlach E, Winterhalter S, Torun N. Long-term Results of Intraocular Pressure Elevation and Post-DMEK Glaucoma After Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea. 2021;40(1):26-32. [CrossRef]

- Stanzel TP, Ersoy L, Sansanayudh W, Felsch M, Dietlein T, Bachmann B, et al. Immediate Postoperative Intraocular Pressure Changes After Anterior Chamber Air Fill in Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea. 2016;35(1):14-9. [CrossRef]

- Steindor F, Hayawi M; Borrelli M; Strzalkowska A; Menzel-Severing J, Geerling G. Nd:YAG Laser Iridotomy Versus Surgical Iridectomy in Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty: Comparison of Postoperative Outcome and Incidence of Ocular Hypertension. Cornea 2025 Jan 21. [CrossRef]

- Metz D, Gan G, Goetz C, Zevering Y, Moskwa R, Vermion J, Perone J. Multivariate relationships between graft detachment after DMEK and twelve pre/perioperative factors. Sci Rep 2025 Jul 26;15(1):27179. [CrossRef]

- Baydoun L, et al. Endothelial Cell Loss and Graft Survival After Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK): Five-Year Follow-up Study. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(2):222–228.

- Ting DSJ, et al. Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK): Clinical Outcomes and Current Perspectives. Eye. 2020;34(2):247–259.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).