Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

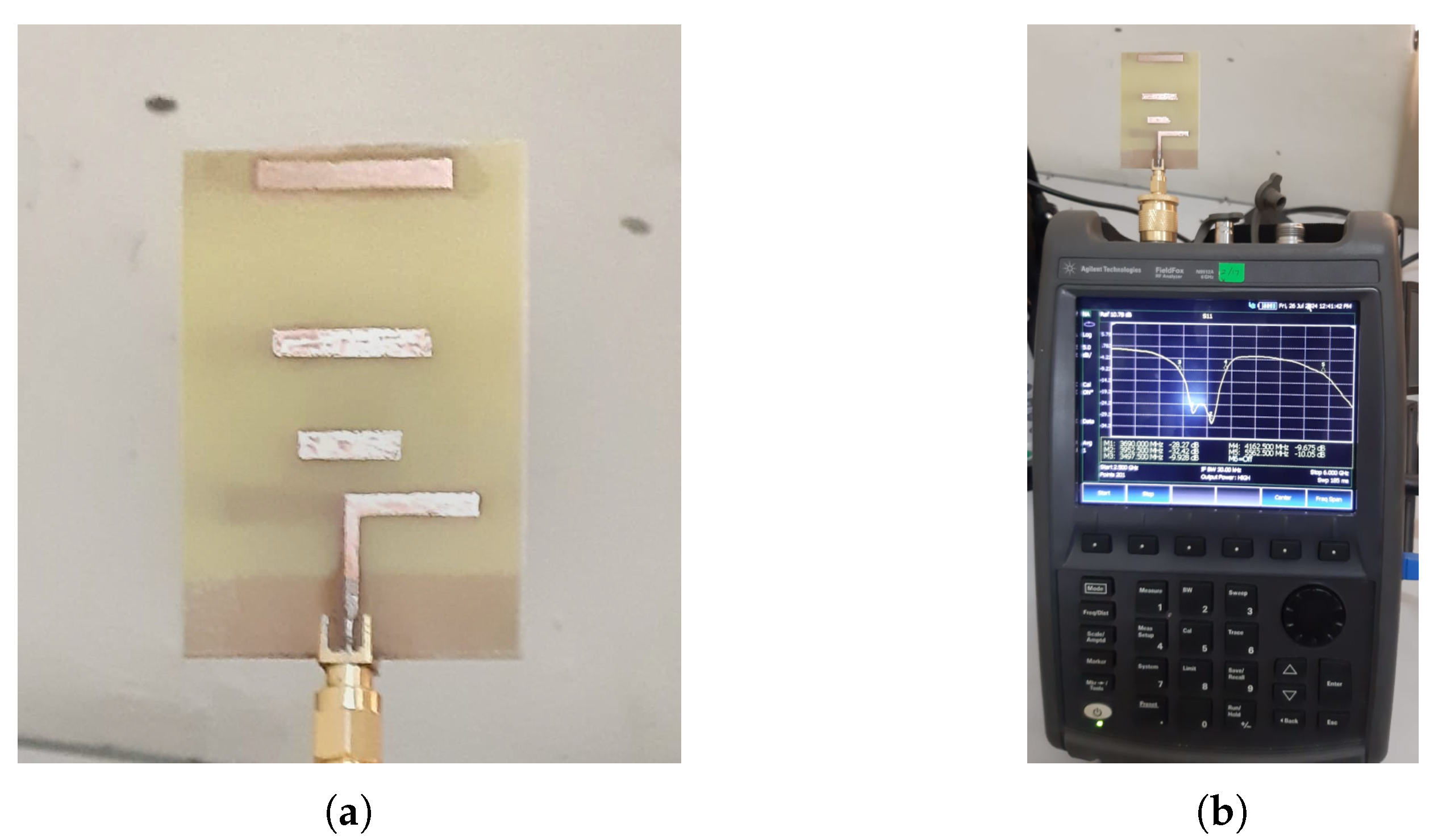

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

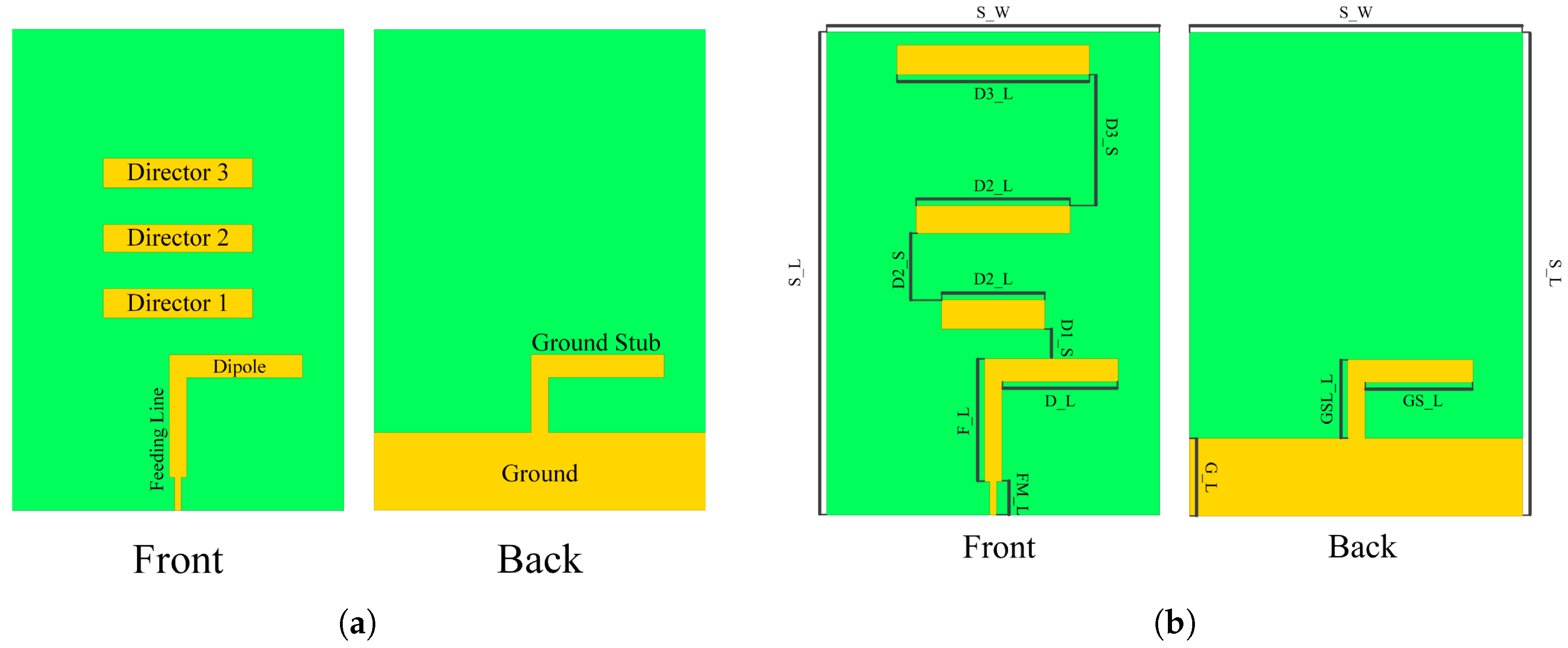

2. Designing the Microstrip Planar Yagi Antenna

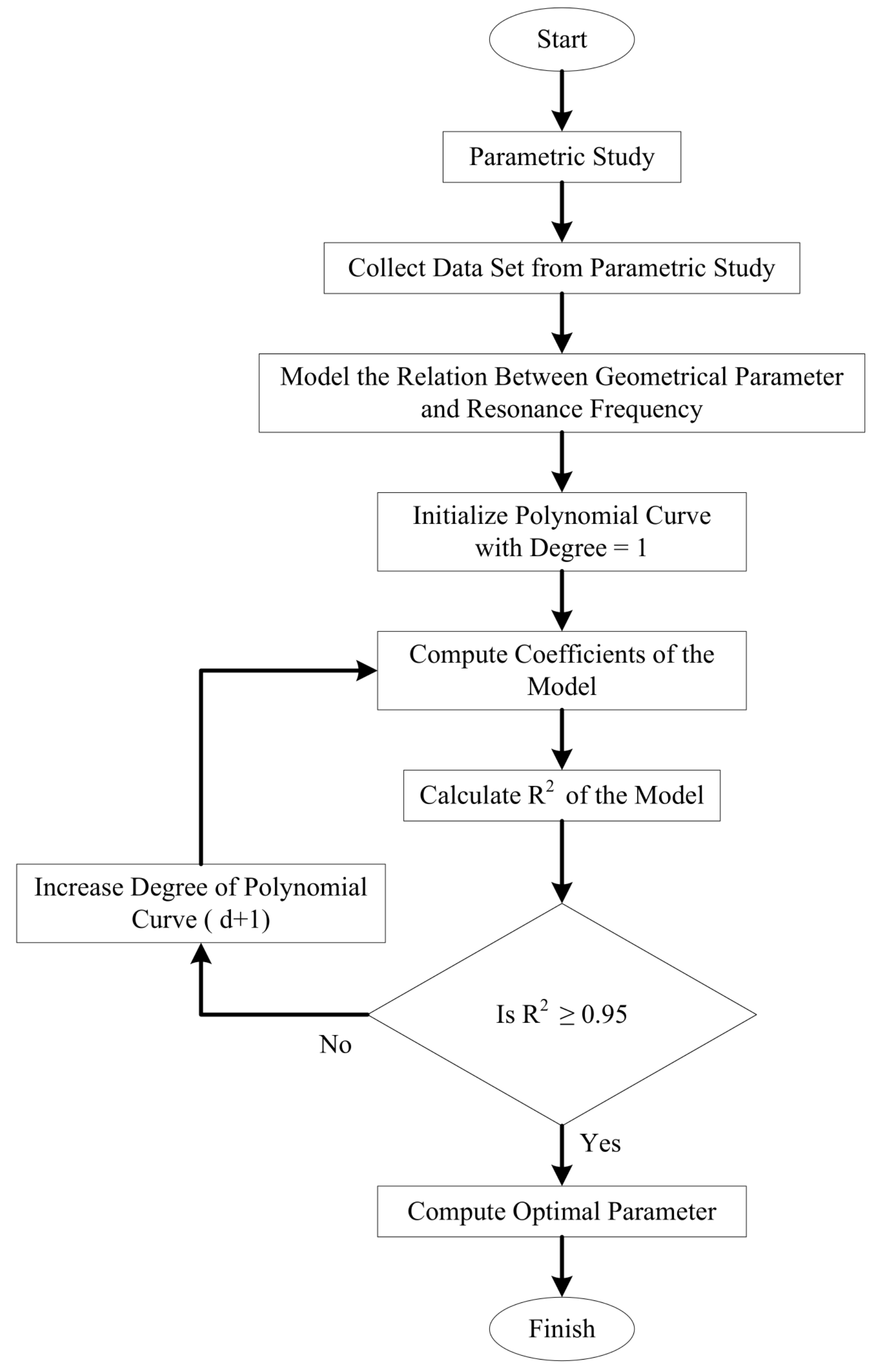

3. Optimization of the Microstrip Planar Yagi Antenna

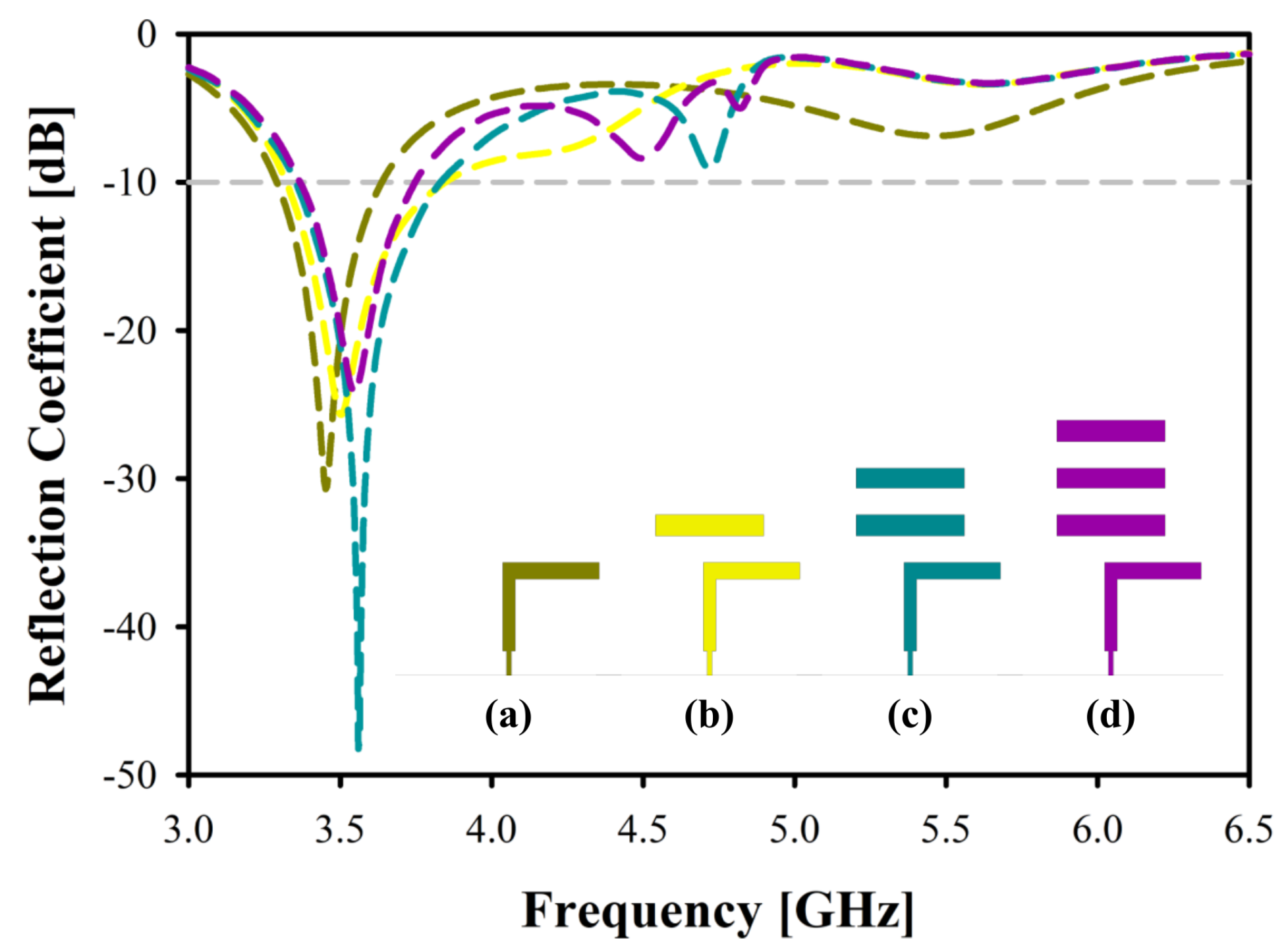

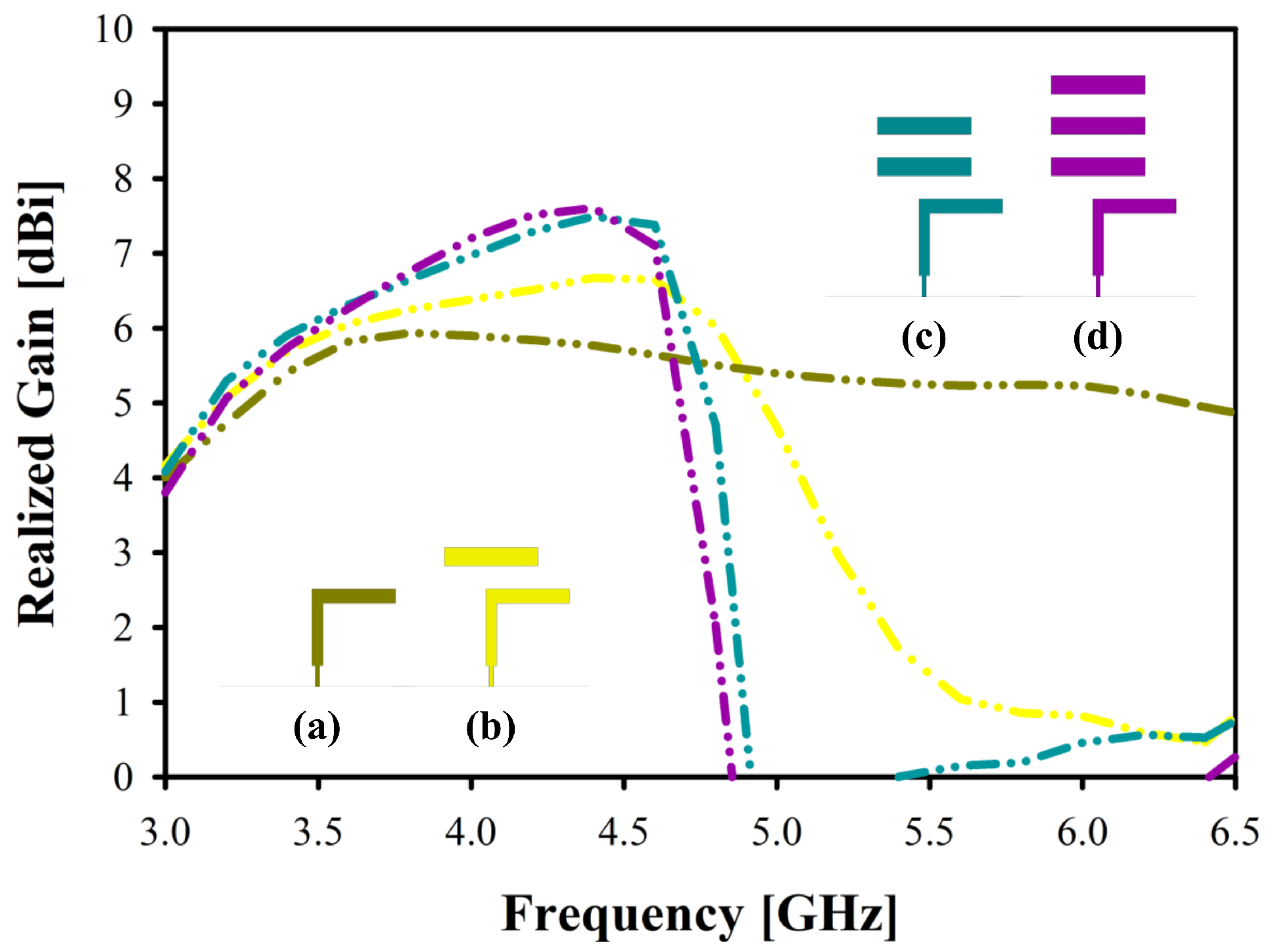

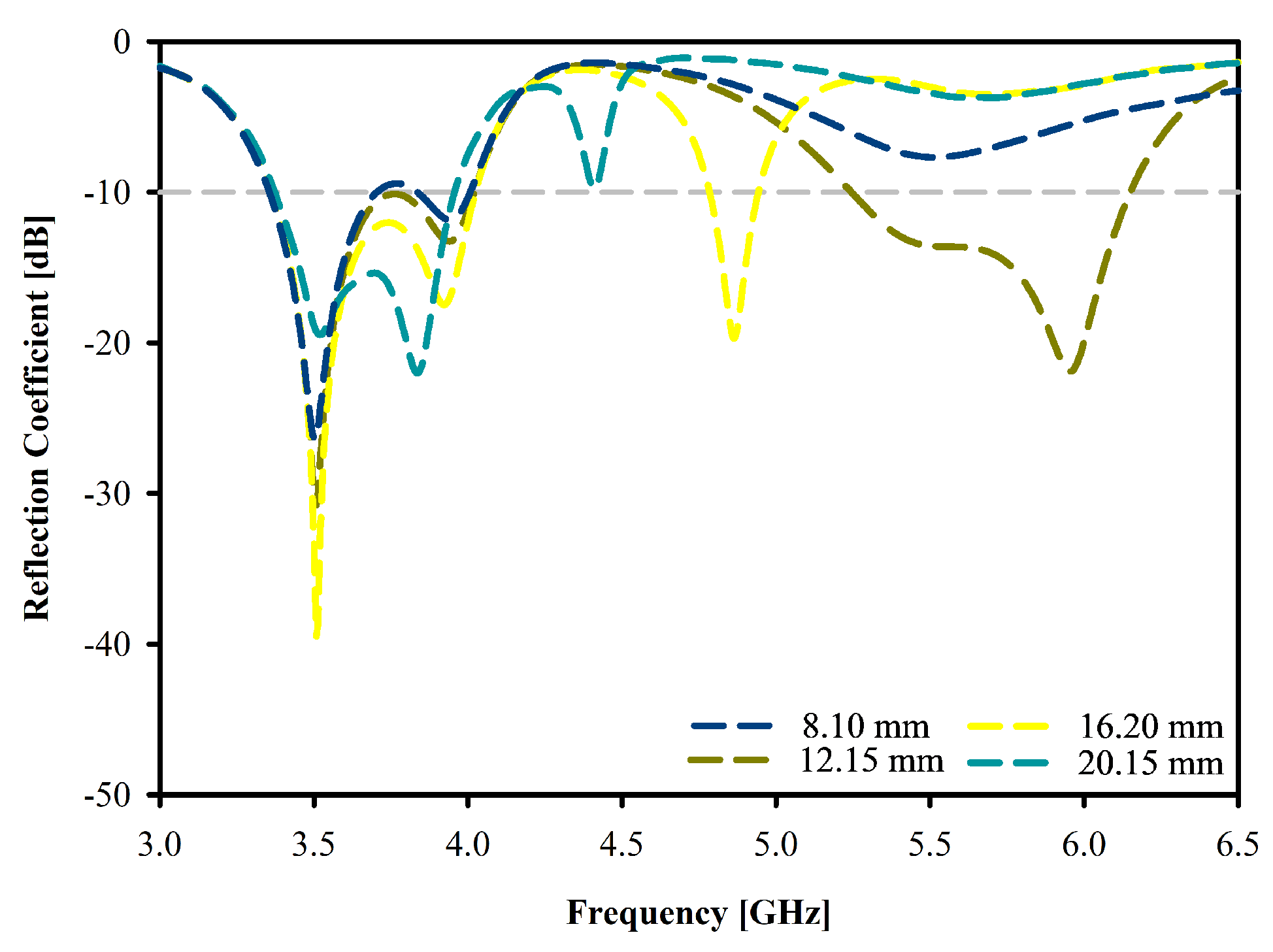

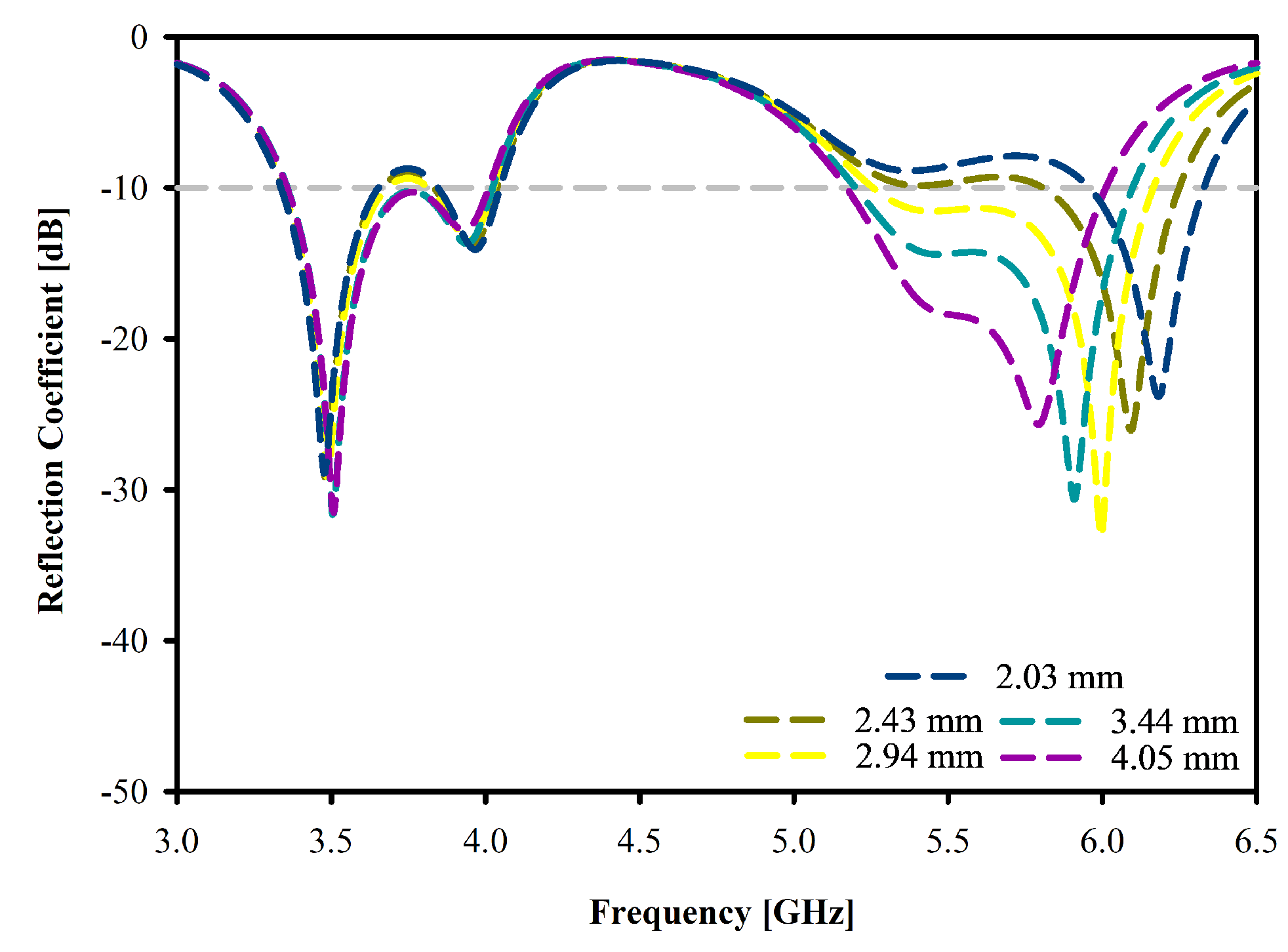

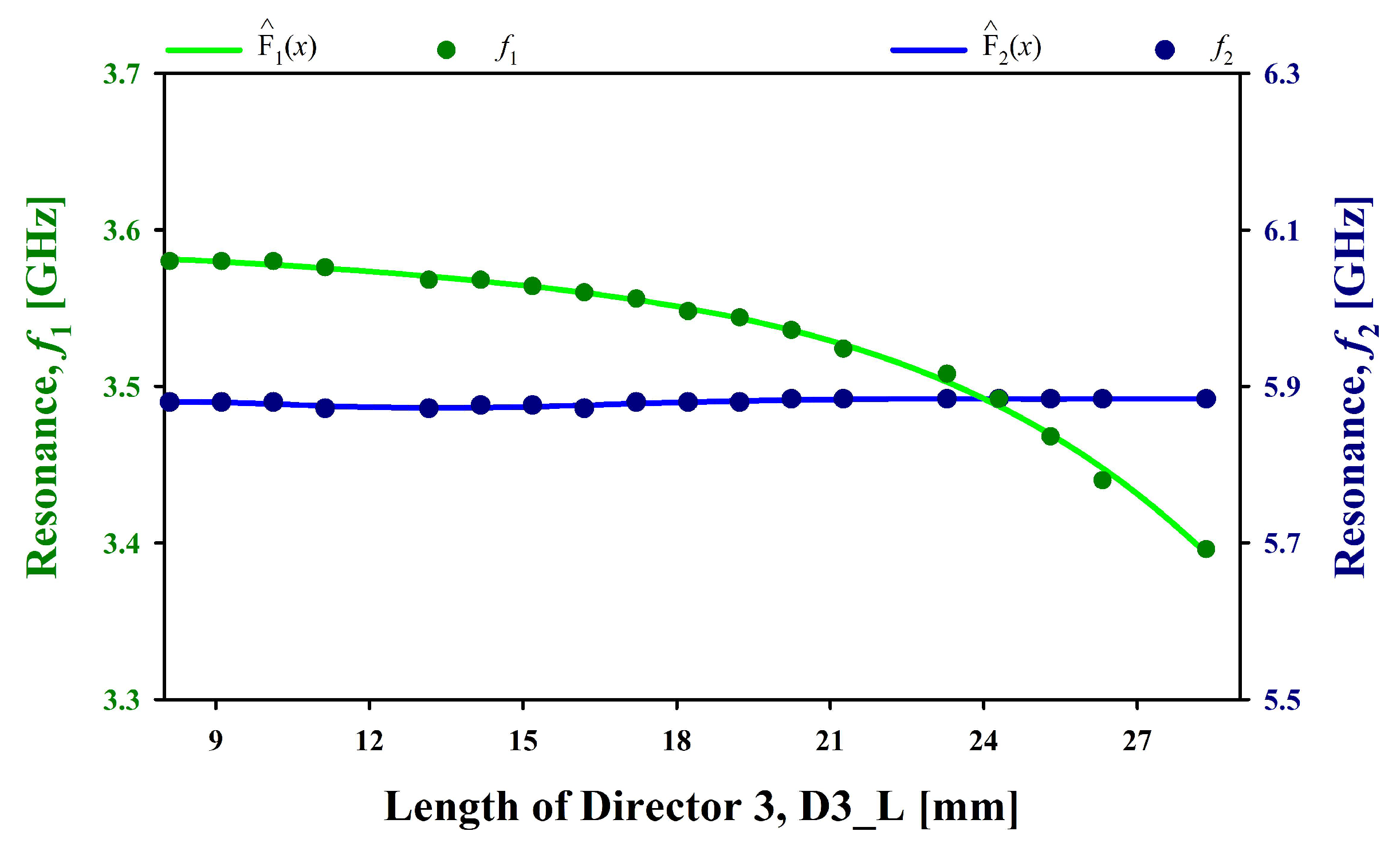

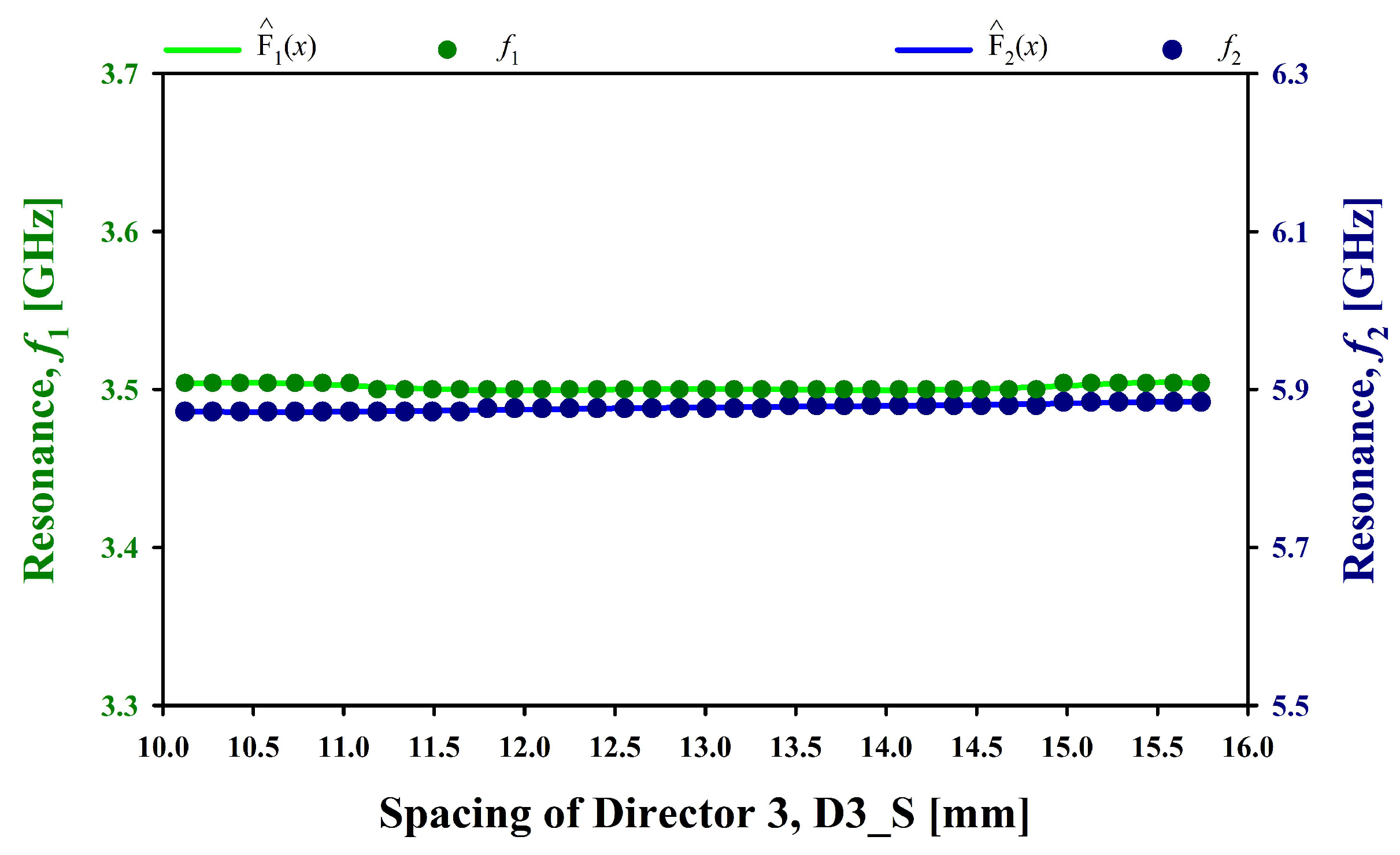

3.1. Parametric Analysis of the Single-Band Antenna

3.2. Data Arrangement and Curve Fitting

- represents the electromagnetic simulation function that maps the geometry to a resulting frequency.

- f is the computed resonance frequency.

- is the resonance frequency of the band,

- represents the simulation function relating the input parameter to the corresponding resonance frequency.

- is the value of the input parameter for the sample,

- is the simulated resonance frequency for the band at sample j.

- is the degree of the polynomial,

- are the polynomial coefficients for the band.

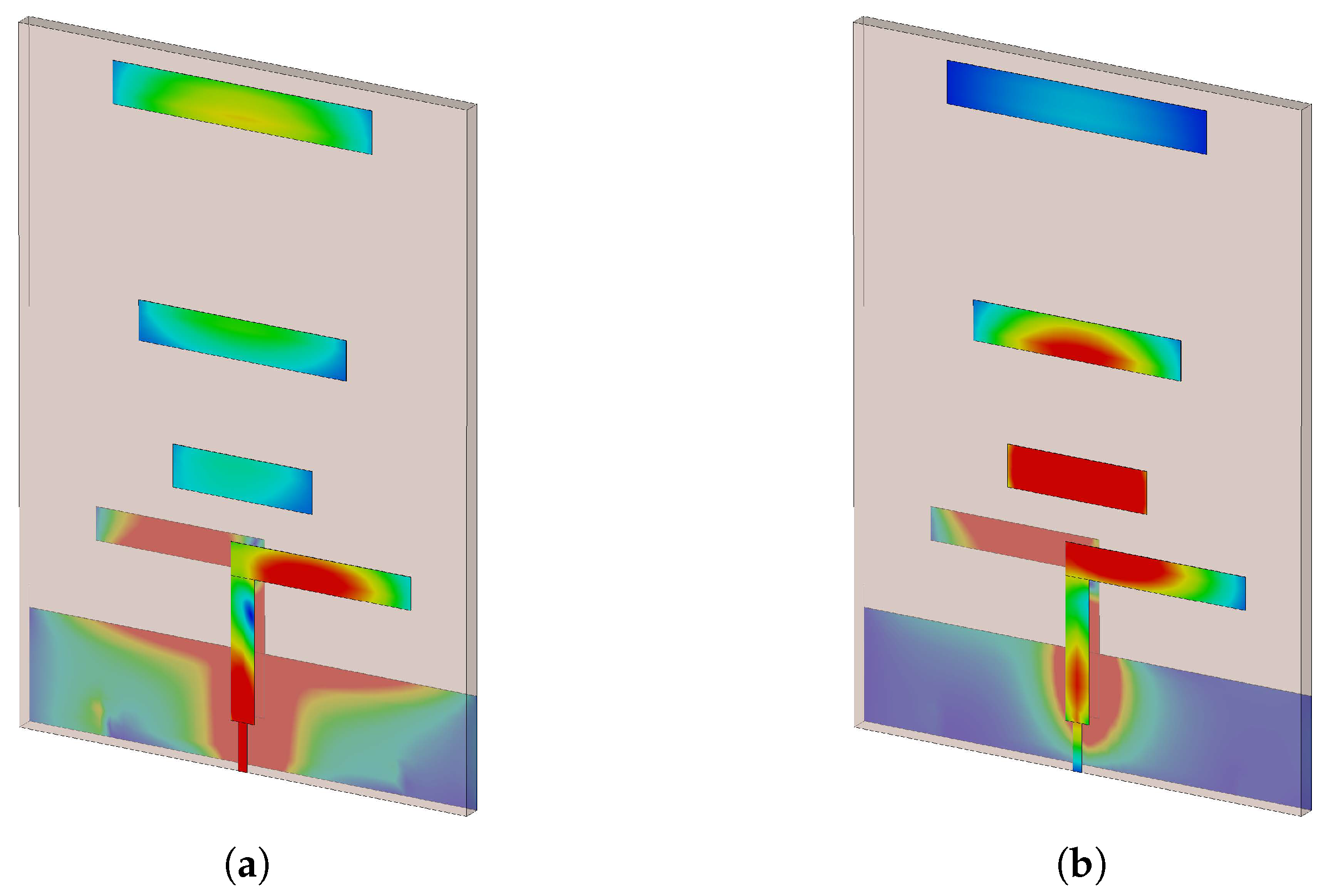

3.3. Visualization of Current Distribution

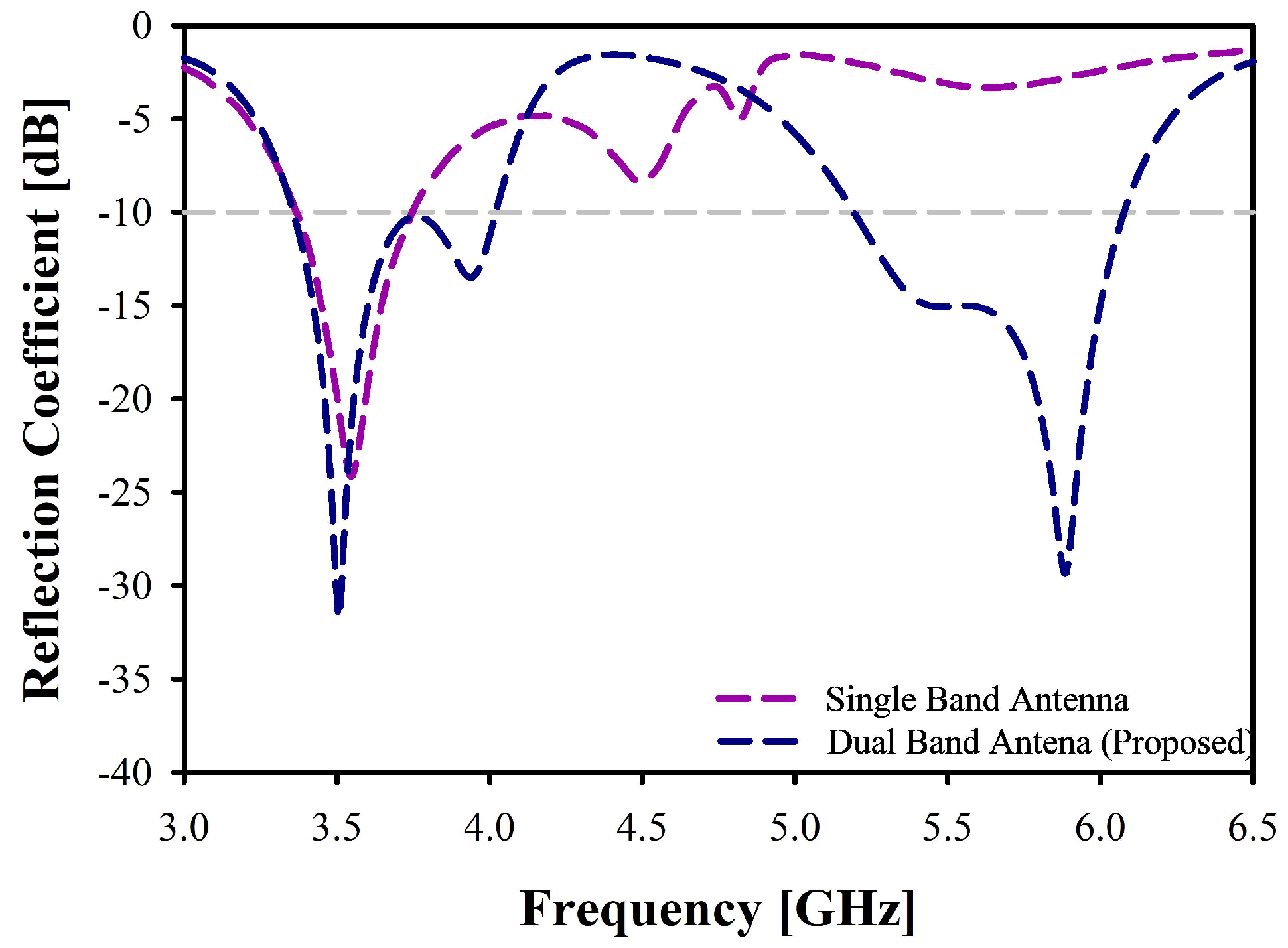

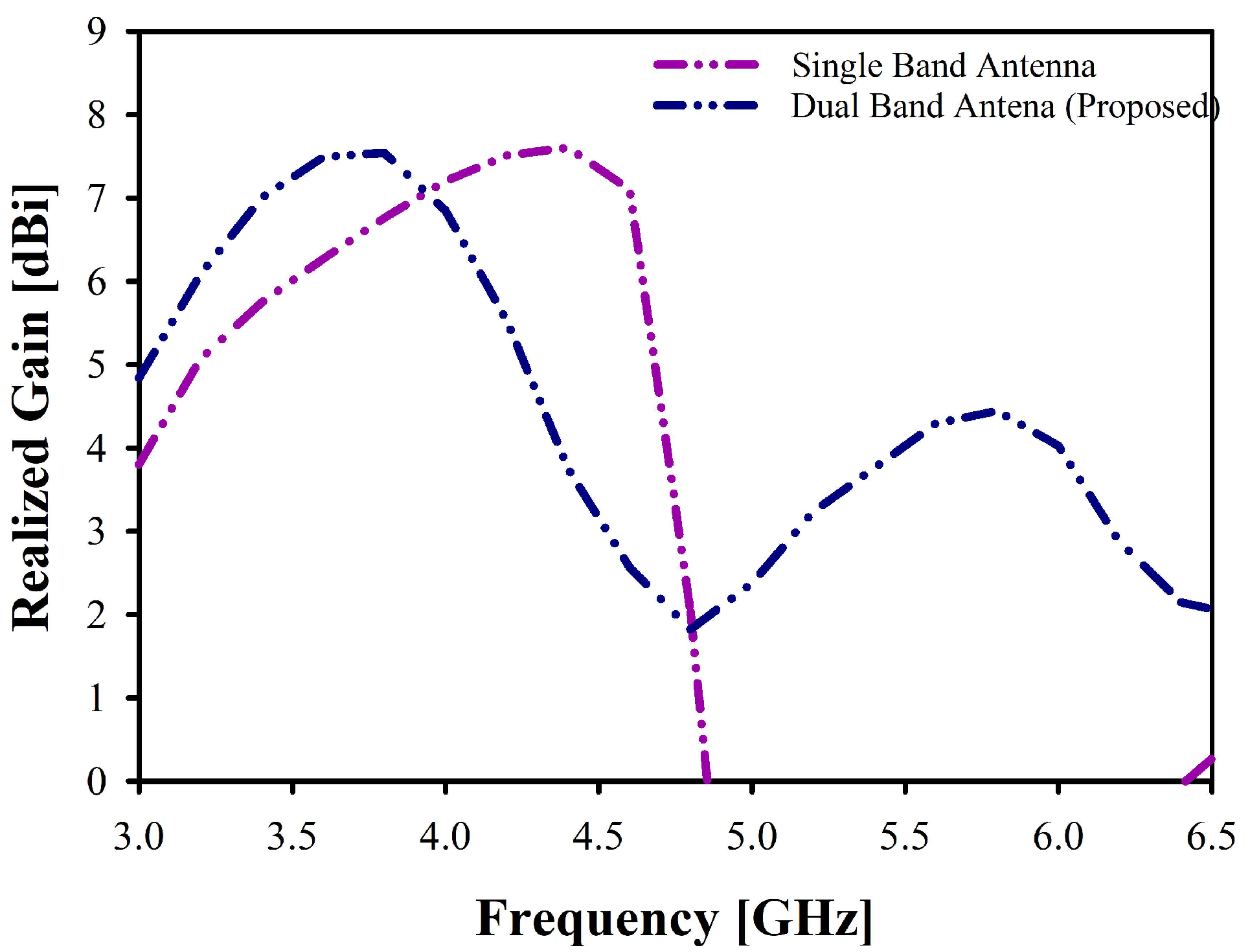

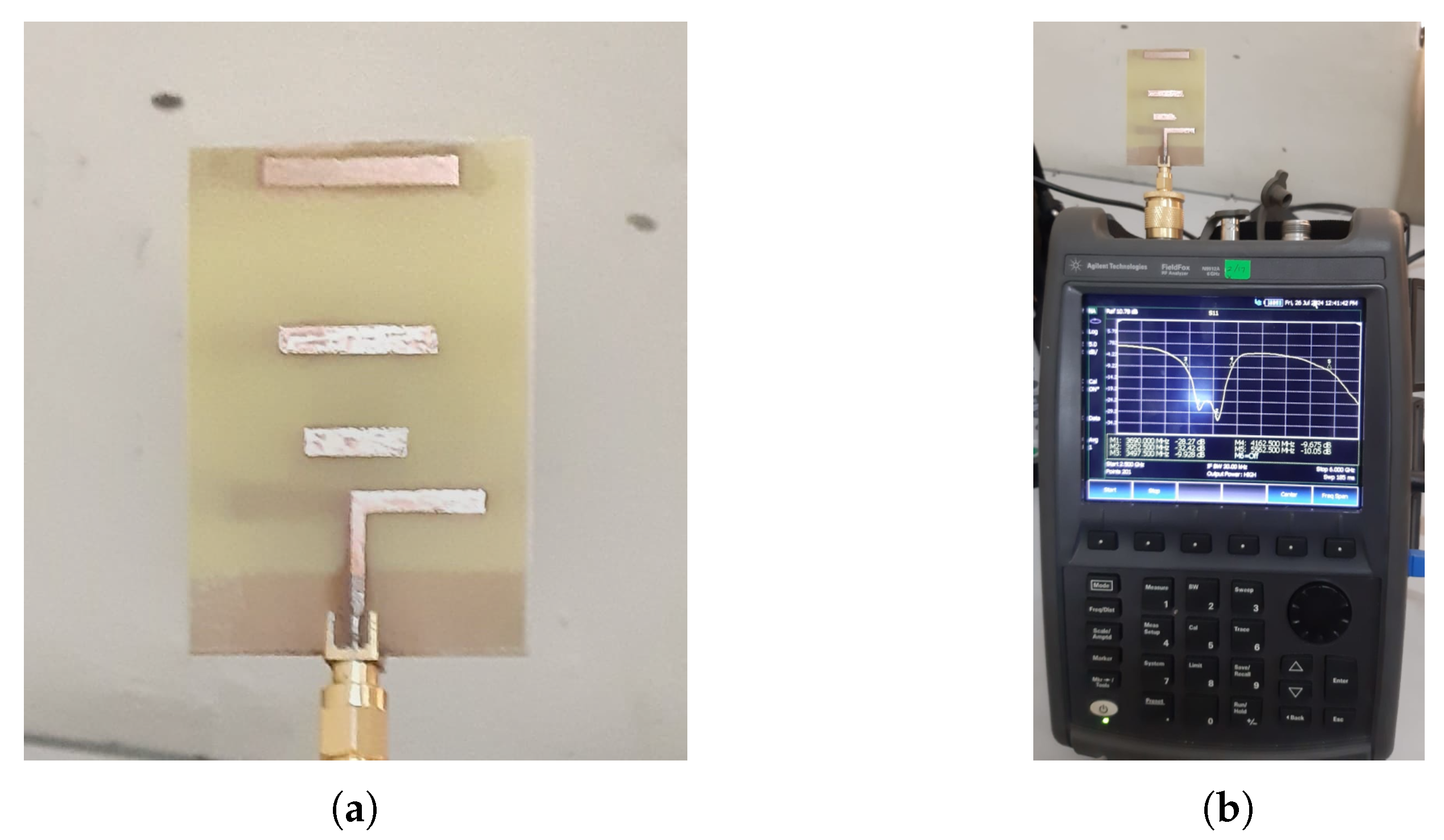

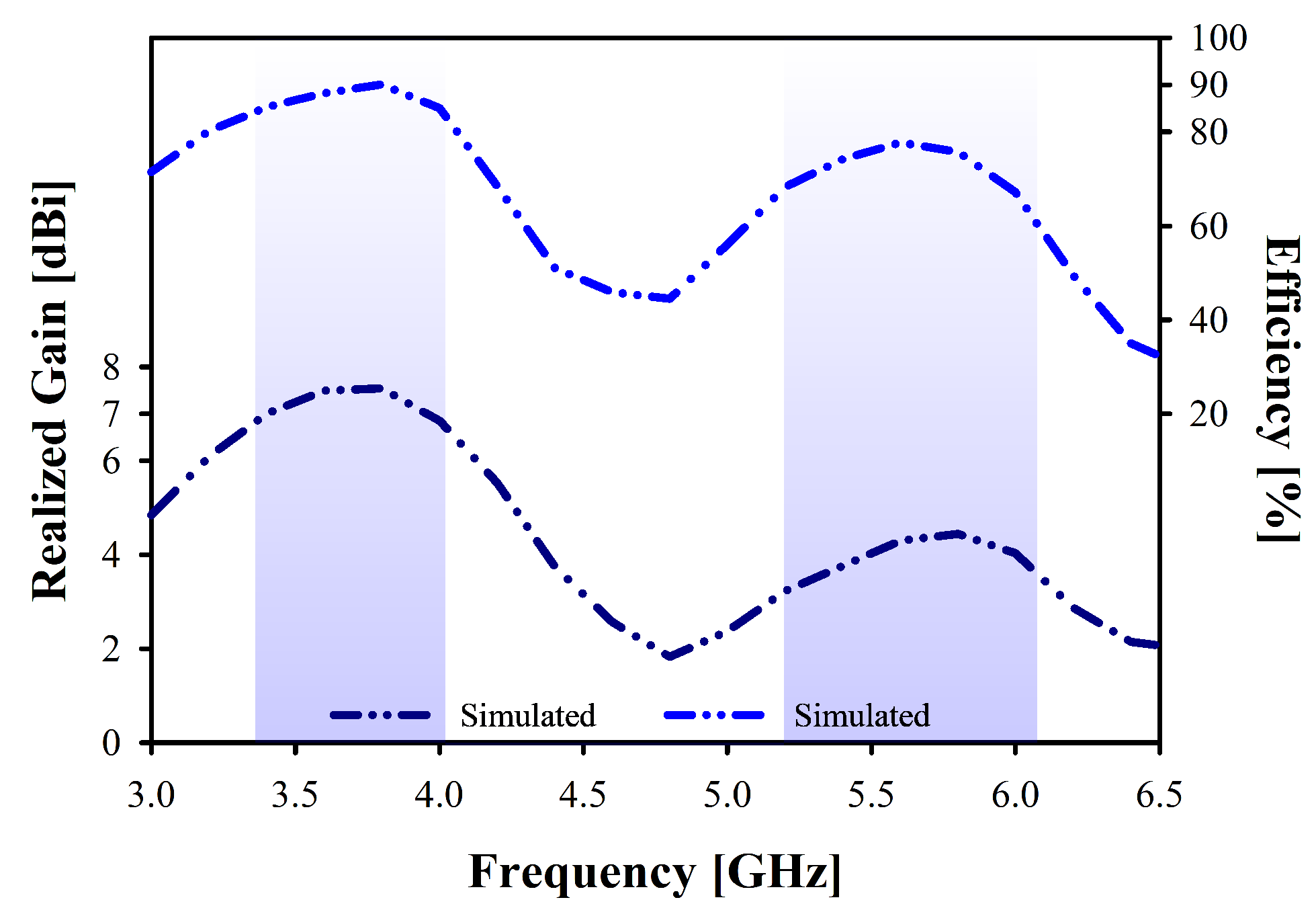

4. Result Analysis of the Optimized Dual-Band Antenna

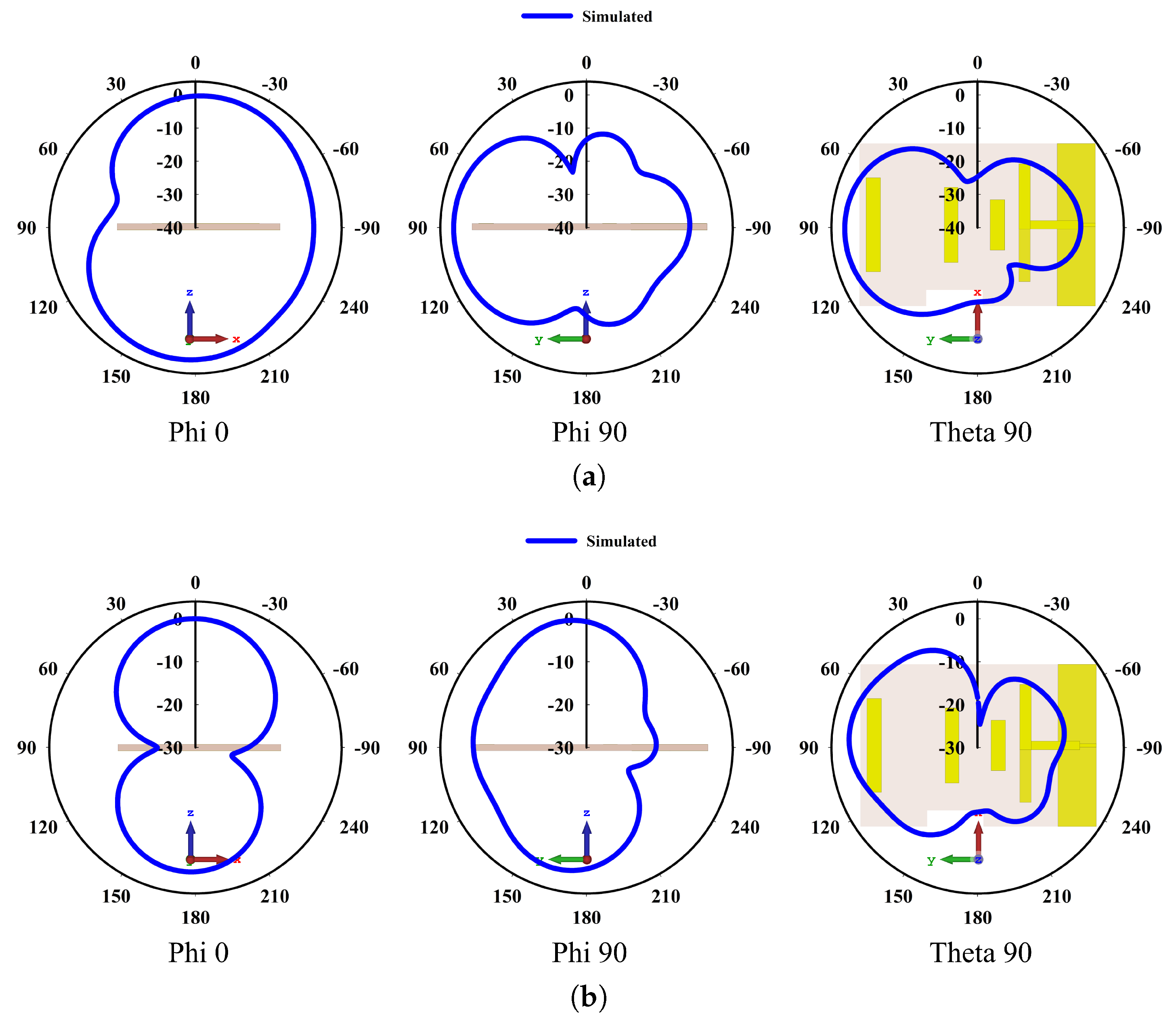

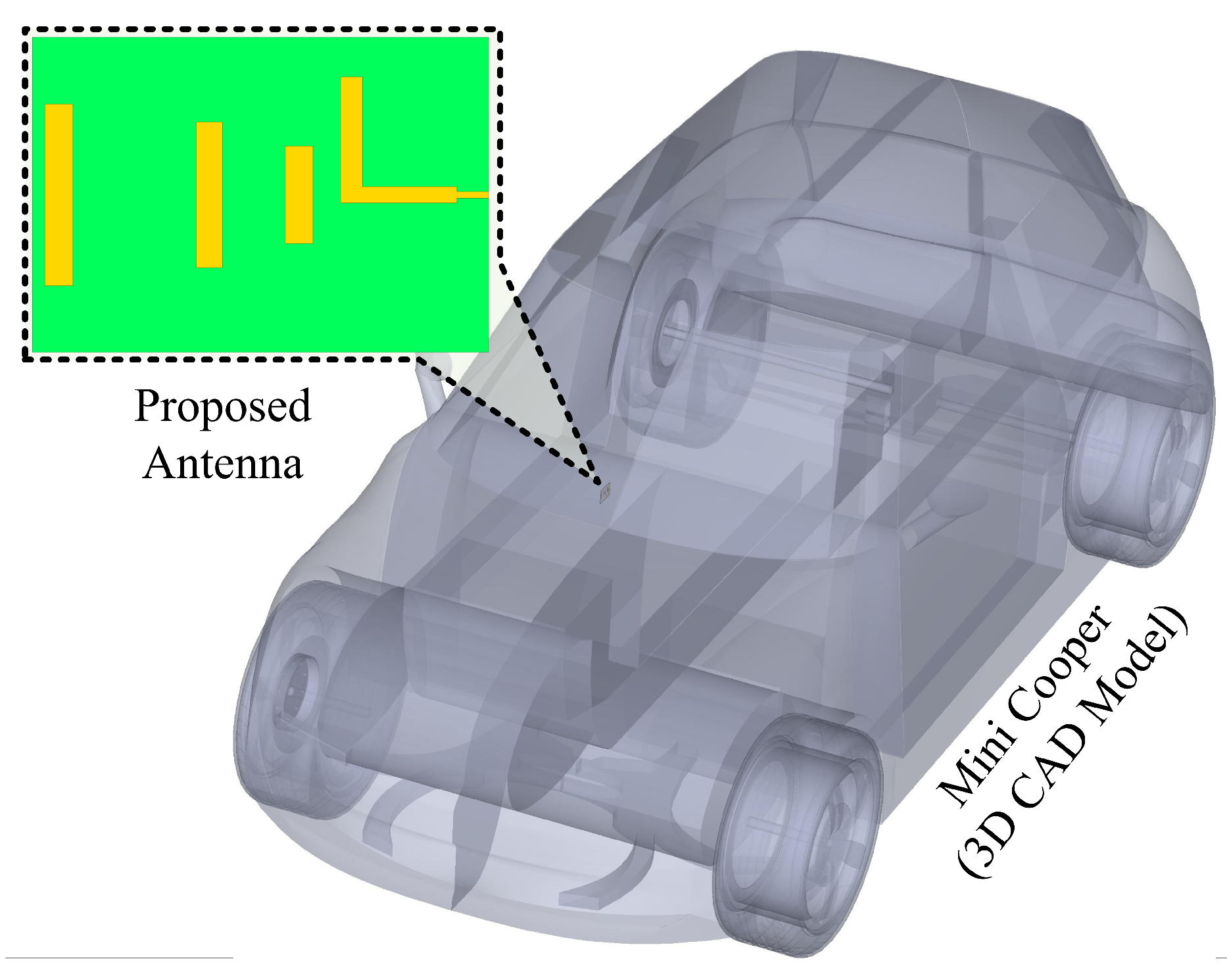

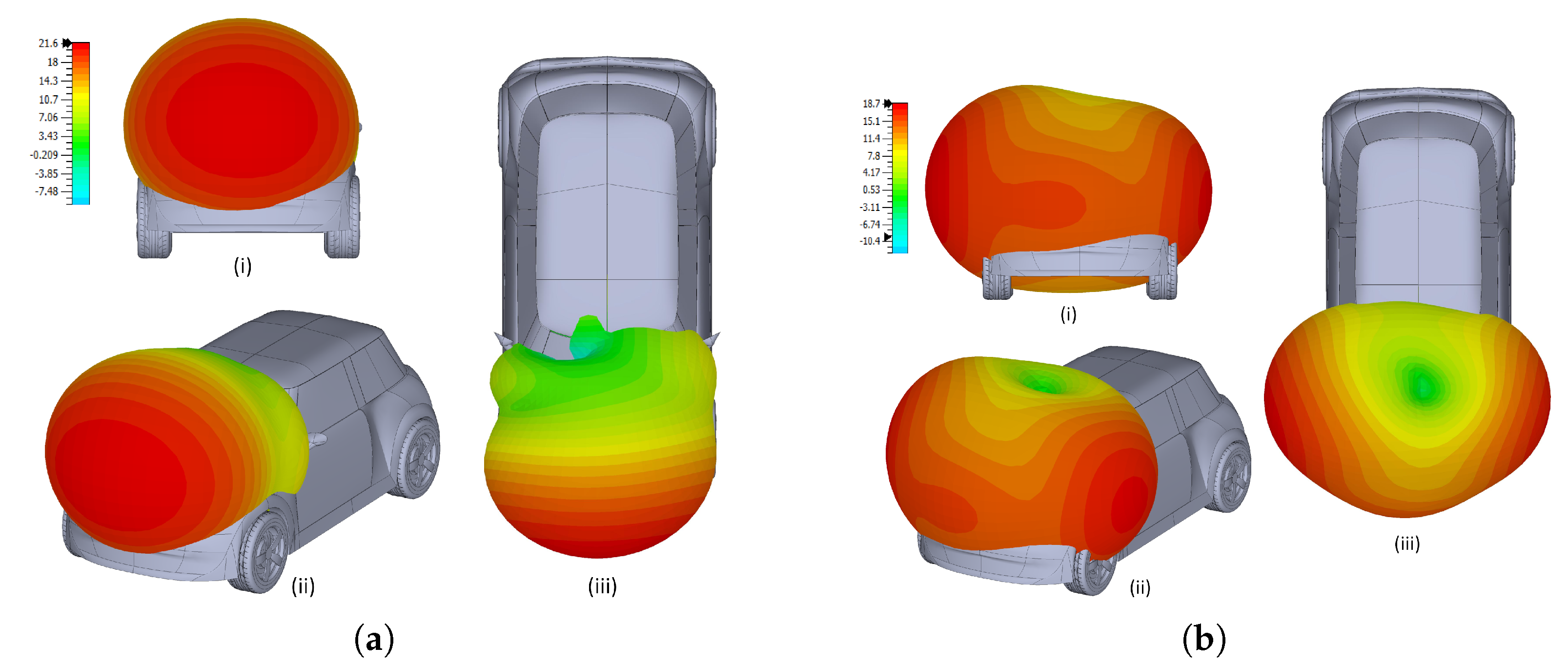

5. 3D Radiation Pattern of the Proposed Antenna with Vehicle Integration

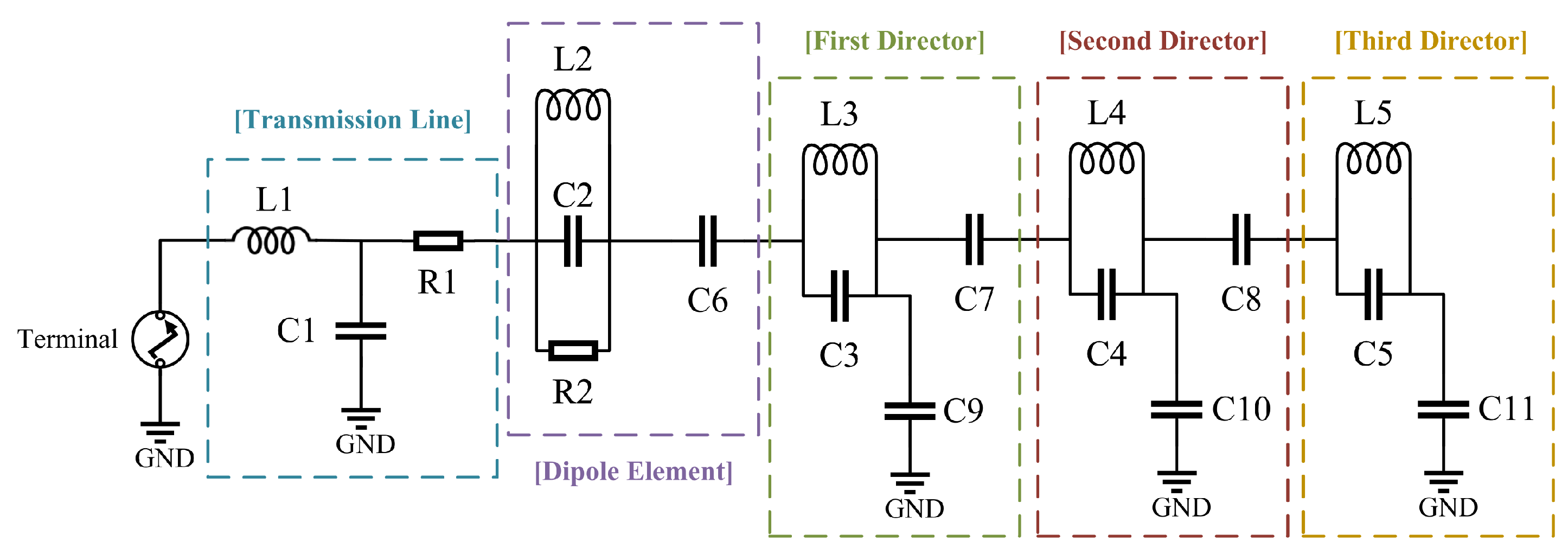

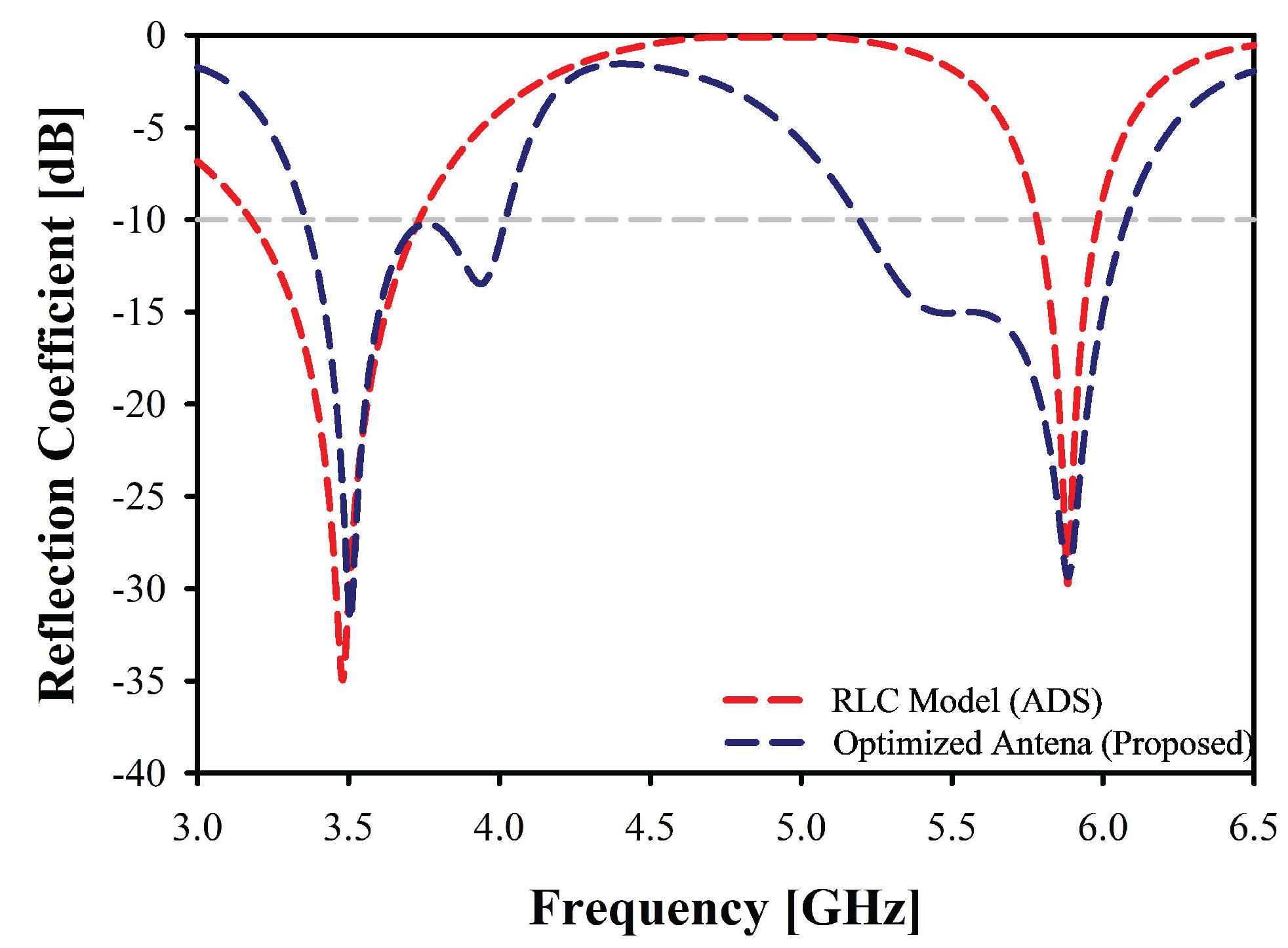

6. RLC Equivalent Circuit Model of the Optimized Dual-Band Antenna

7. Comparative Analysis of the Proposed Antenna

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Finance, B.N.E. Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Electric Vehicle Outlook 2023. https://assets.bbhub.io/professional/sites/24/2431510_BNEFElectricVehicleOutlook2023_ExecSummary.pdf, 2023. [Accessed 05-06-2024].

- K, B.N.K.R.; D, P.; B, S.; E, J.R. Recent AI Applications in Electrical Vehicles for Sustainability. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2024, 11, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Piamrat, K.; Singh, K.; Chen, H.C. Data analysis for self-driving vehicles in intelligent transportation systems. Journal of Advanced Transportation 2020, 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elassy, M.; Al-Hattab, M.; Takruri, M.; Badawi, S. Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities. Transportation Engineering, 1002. [Google Scholar]

- Autili, M.; Chen, L.; Englund, C.; Pompilio, C.; Tivoli, M. Cooperative intelligent transport systems: Choreography-based urban traffic coordination. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 22, 2088–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, S.W. Cooperative automated vehicles: A review of opportunities and challenges in socially intelligent vehicles beyond networking. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2019, 4, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research, A.M. Automotive V2X Market Size, Technology, Report 2021-2030 — alliedmarketresearch.com. https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/automotive-v2x-market-A07120. [Accessed 28-05-2024].

- Mir, Z.H.; Dreyer, N.; Kürner, T.; Filali, F. Investigation on cellular LTE C-V2X network serving vehicular data traffic in realistic urban scenarios. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 161, 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Maglogiannis, V.; Naudts, D.; Hadiwardoyo, S.; Van Den Akker, D.; Marquez-Barja, J.; Moerman, I. Experimental V2X evaluation for C-V2X and ITS-G5 technologies in a real-life highway environment. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2021, 19, 1521–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Hakeem, S.A.; Hady, A.A.; Kim, H. 5G-V2X: Standardization, architecture, use cases, network-slicing, and edge-computing. Wireless Networks 2020, 26, 6015–6041. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, D.; Nawi, I.M.; Zakariya, M. Super low profile 5G mmWave highly isolated MIMO antenna with 360∘ pattern diversity for smart city IoT and vehicular communication. Results in Engineering 2024, 24, 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, T.; Timm, M.; Munteanu, I. A practical guide to 3-D simulation. IEEE microwave magazine 2008, 9, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alieldin, A.; Huang, Y.; Boyes, S.J.; Stanley, M.; Joseph, S.D.; Hua, Q.; Lei, D. A triple-band dual-polarized indoor base station antenna for 2G, 3G, 4G and sub-6 GHz 5G applications. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 49209–49216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsolu, M.O.; Mistry, K.K.; Liu, B.; Lazaridis, P.I.; Excell, P. Machine learning-assisted antenna design optimization: A review and the state-of-the-art. In Proceedings of the 2020 14th European conference on antennas and propagation (EuCAP). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Koziel, S.; Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Improved-efficacy EM-driven optimization of antenna structures using adaptive design specifications and variable-resolution models. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2023, 71, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. On nature-inspired design optimization of antenna structures using variable-resolution EM models. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 8373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Çalık, N.; Mahouti, P.; Belen, M.A. Low-cost and highly accurate behavioral modeling of antenna structures by means of knowledge-based domain-constrained deep learning surrogates. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2022, 71, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Xiao, L.Y.; Liu, Q.H. Machine Learning-Based Design Scheme for Multifunctional Antenna Arrays with Reconfigurable Scattering Patterns. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shereen, M.K.; Liu, X.; Wu, X. Support Vector Regression for Gain and S11 Prediction: a Low-Complexity Solution for Antenna Design. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Antenna Technology and Applied Electromagnetics (ANTEM). IEEE; 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Al-Bawri, S.S.; Larguech, S.; Alharbi, S.S.; Alsowail, S.; Jizat, N.M.; Islam, M.T. Metamaterial based tri-band compact MIMO antenna system for 5G IoT applications with machine learning performance verification. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 22866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakmouche, M.F.; Deslandes, D.; Nedil, M.; Gagnon, G. Machine learning-aided design of defected ground structures for PRGW-based MIMO antennas. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shereen, M.K.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Naseem, A.; Uzair, M. Deep learning-inspired linear regression technique for accurate microstrip antenna performance analysis. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Electronics Representation and Algorithm (ICERA). IEEE; 2025; pp. 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.A.; Ahammed, M.S.; Rahaman, M.S.A.; Ahmed, M.K.; Nahin, K.H.; Sawaran Singh, N.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Jaafar, J.; Al-Bawri, S.S. High Performance Quad Port Compact MIMO Antenna for 38 GHz 5G Application with Regression Machine Learning Prediction. Journal of Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves 2025, 46, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, N.K.; Alzahrani, Y.; Penmatsa, K.K.V.; Pandey, A.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Singh, V.; Tolani, M. Machine learning aided tapered 4-port MIMO antenna for V2X communications with enhanced gain and isolation. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanti, H.A.; Datta, A.; Biswas, T.; Tripathi, A. Development of a machine learning-based radio source localization algorithm for tri-axial antenna configuration. Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy 2025, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye, P.A.; Singh, S.P.; Sharma, M.K. Hybrid optimization framework for MIMO antenna design in wearable IoT applications using deep learning and bayesian method. Brazilian Journal of Physics 2025, 55, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Yusof, N.A.T.; Faudzi, A.A.M.; Tomal, M.R.I.; Haque, M.E.; Rahman, M.S. Machine learning-based approach for bandwidth and frequency prediction of circular SIW antenna. Journal of King Saud University–Engineering Sciences 2025, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A.; Pankiewicz, B. On accelerated metaheuristic-based electromagnetic-driven design optimization of antenna structures using response features. Electronics 2024, 13, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Efficient simulation-based global antenna optimization using characteristic point method and nature-inspired metaheuristics. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. Expedited feature-based quasi-global optimization of multi-band antenna input characteristics with jacobian variability tracking. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 83907–83915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Weeber, J.C.; Markey, L.; Arocas, J.; Bouhelier, A.; Leray, A.; des Francs, G.C. Nano antenna-assisted quantum dots emission into high-index planar waveguide. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 265201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbano, N. Log periodic Yagi-Uda array. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 1966, 14, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Valentini, R.; Cinque, E.; Di Marco, P.; Santucci, F. On the Impact of Multiple Access Interference in LTE-V2X and NR-V2X Sidelink Communications. Sensors 2023, 23, 4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficzere, D.; Varga, P.; Wippelhauser, A.; Hejazi, H.; Csernyava, O.; Kovács, A.; Hegedus, C. Large-Scale Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything Deployments Based on 5G—Critical Challenges, Solutions, and Vision towards 6G: A Survey. Sensors 2023, 23, 7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, M.; Malviya, L. Design, developments, and applications of 5G antennas: a review. International journal of microwave and wireless technologies 2023, 15, 156–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihei, B.; Barclay, C.; Greaves-Taylor, J.; et al. 5.9 GHz Interference Resiliency for Connected Vehicle Equipment. Technical report, Georgia. Dept. of Transporation. Office of Performance-Based Management and …, 2023.

- Boursianis, A.D.; Papadopoulou, M.S.; Pierezan, J.; Mariani, V.C.; Coelho, L.S.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Koulouridis, S.; Goudos, S.K. Multiband patch antenna design using nature-inspired optimization method. IEEE Open journal of Antennas and Propagation 2020, 2, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Chang, T.H.; Hong, M.; Wu, Z.; So, A.M.C.; Jorswieck, E.A.; Yu, W. A survey of recent advances in optimization methods for wireless communications. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Zakariya, M.A.; Singh, N.S.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Paul, L.C. Parametric study of a dual-band quasi-Yagi antenna for LTE application. Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics 2023, 12, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A.; Koziel, S. Accelerated parameter tuning of antenna structures by means of response features and principal directions. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceci, M.S.; Cacheris, W.P. Fitting curves to data. Byte 1984, 9, 340–362. [Google Scholar]

- Lever, J.; Krzywinski, M.; Altman, N. Points of significance: model selection and overfitting. Nature methods 2016, 13, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.K.; Srivastava, D.K. Optimization and parametric analysis of slotted microstrip antenna using particle swarm optimization and curve fitting. International Journal of Circuit Theory and Applications 2021, 49, 1868–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hakim, H.; Mohamed, H.A. synthesis of a multiband microstrip patch antenna for 5G wireless communications. Journal of Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves 2023, 44, 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.J.; Liu, S.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Wang, X.; Li, Q.Y.; Yin, G.Q.; Wang, Z.G. Frequency-and pattern-reconfigurable antenna array with broadband tuning and wide scanning angles. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2023, 71, 5398–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freschi, F.; Giaccone, L.; Cirimele, V.; Solimene, L. Vehicle4em: a collection of car models for electromagnetic simulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Power Transfer Conference and Expo (WPTCE), Rome, Italy; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sufian, M.A.; Hussain, N.; Abbas, A.; Lee, J.; Park, S.G.; Kim, N. Mutual coupling reduction of a circularly polarized MIMO antenna using parasitic elements and DGS for V2X communications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 56388–56400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.Q.; Lu, W.J.; Ji, F.Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, H.B. Low-profile dual-resonant wideband backfire antenna for vehicle-to-everything applications. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 71, 8330–8340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virothu, S.; Anuradha, M.S. Flexible CP diversity antenna for 5G cellular Vehicle-to-Everything applications. AEU-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 2022, 152, 154248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | (MHz) | (MHz) | |

|---|---|---|---|

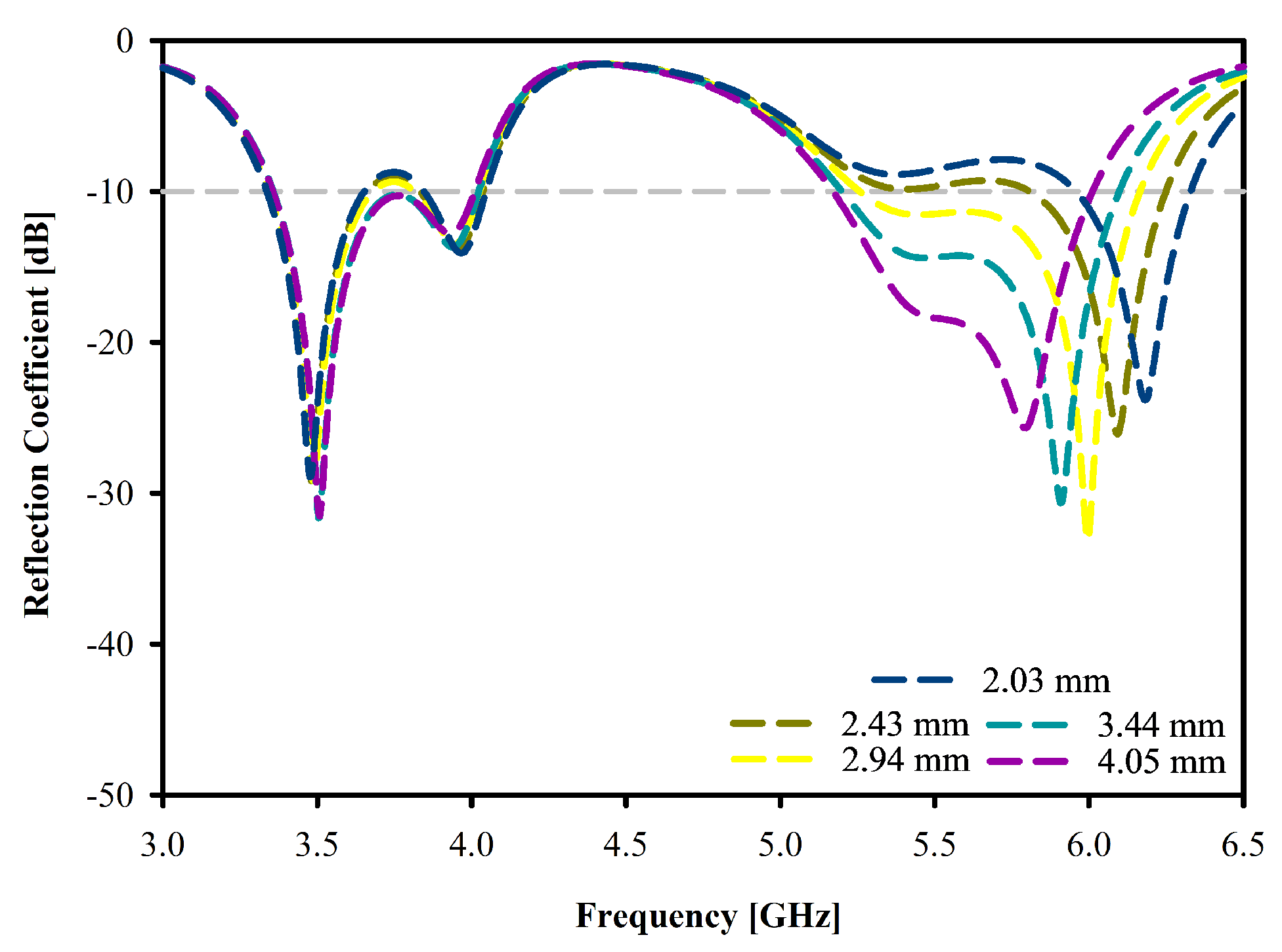

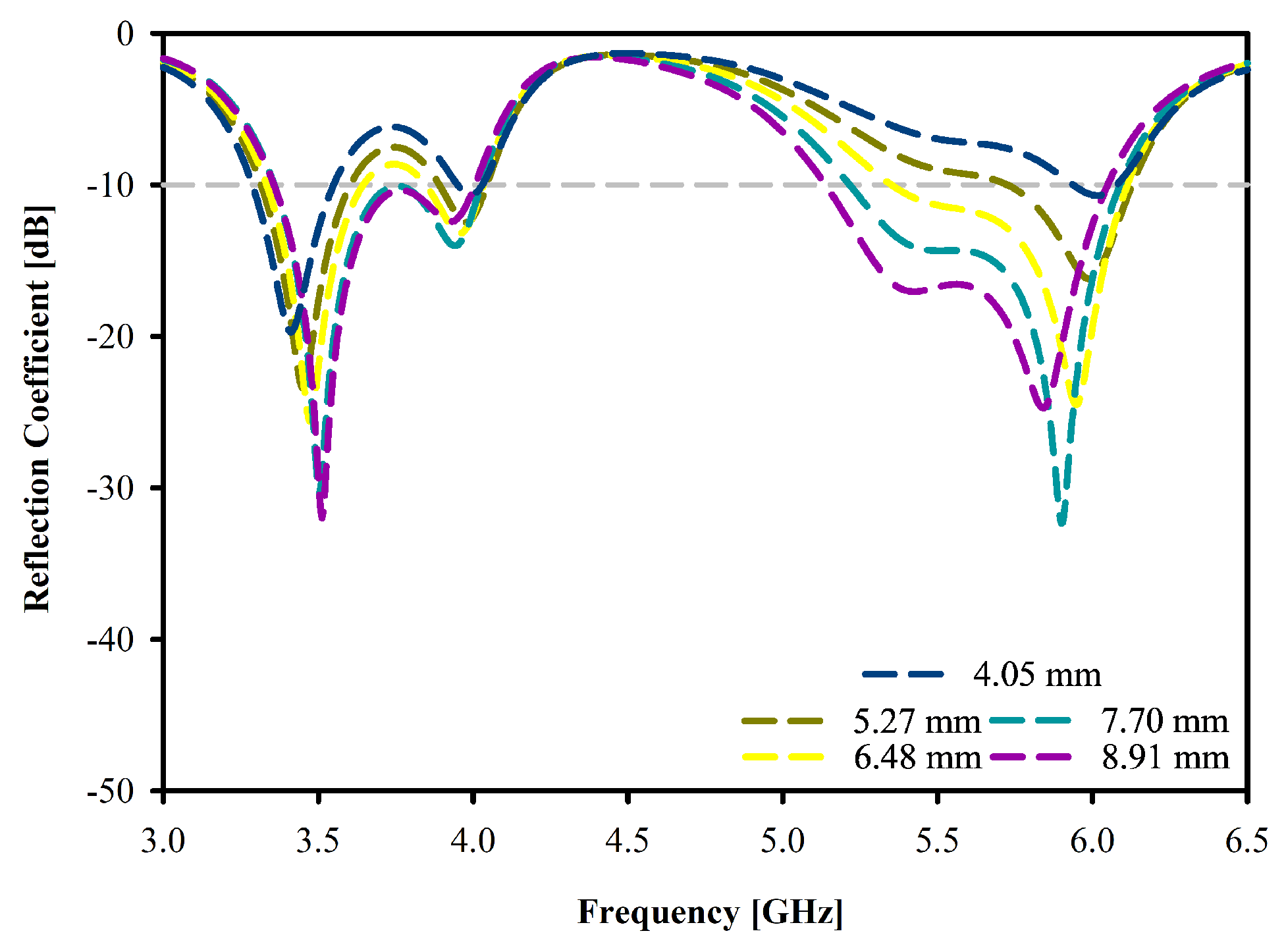

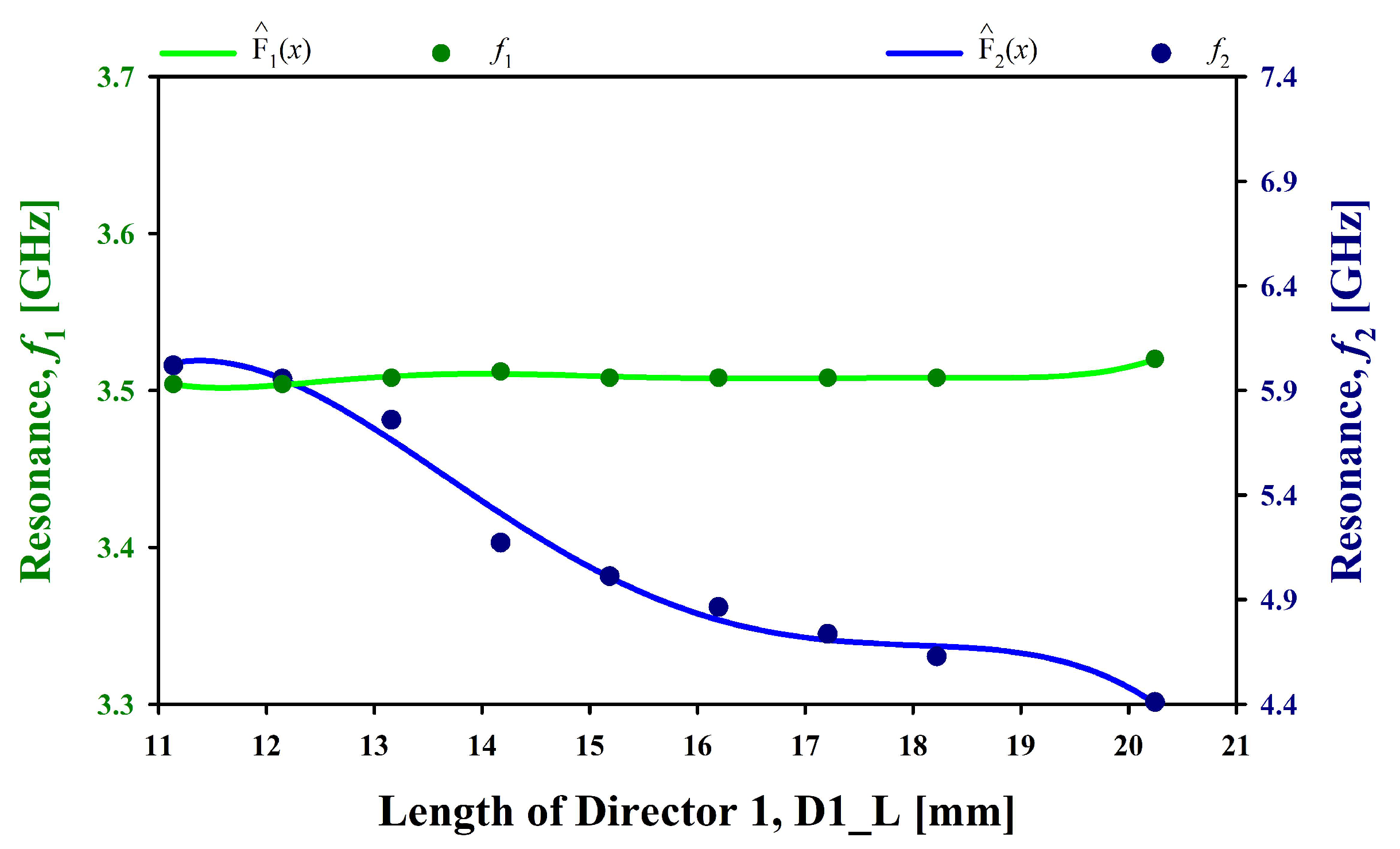

| Director 1 | D1_L | 3504 — 3520 | 4410 — 6020 |

| 11 mm — 21 mm | |||

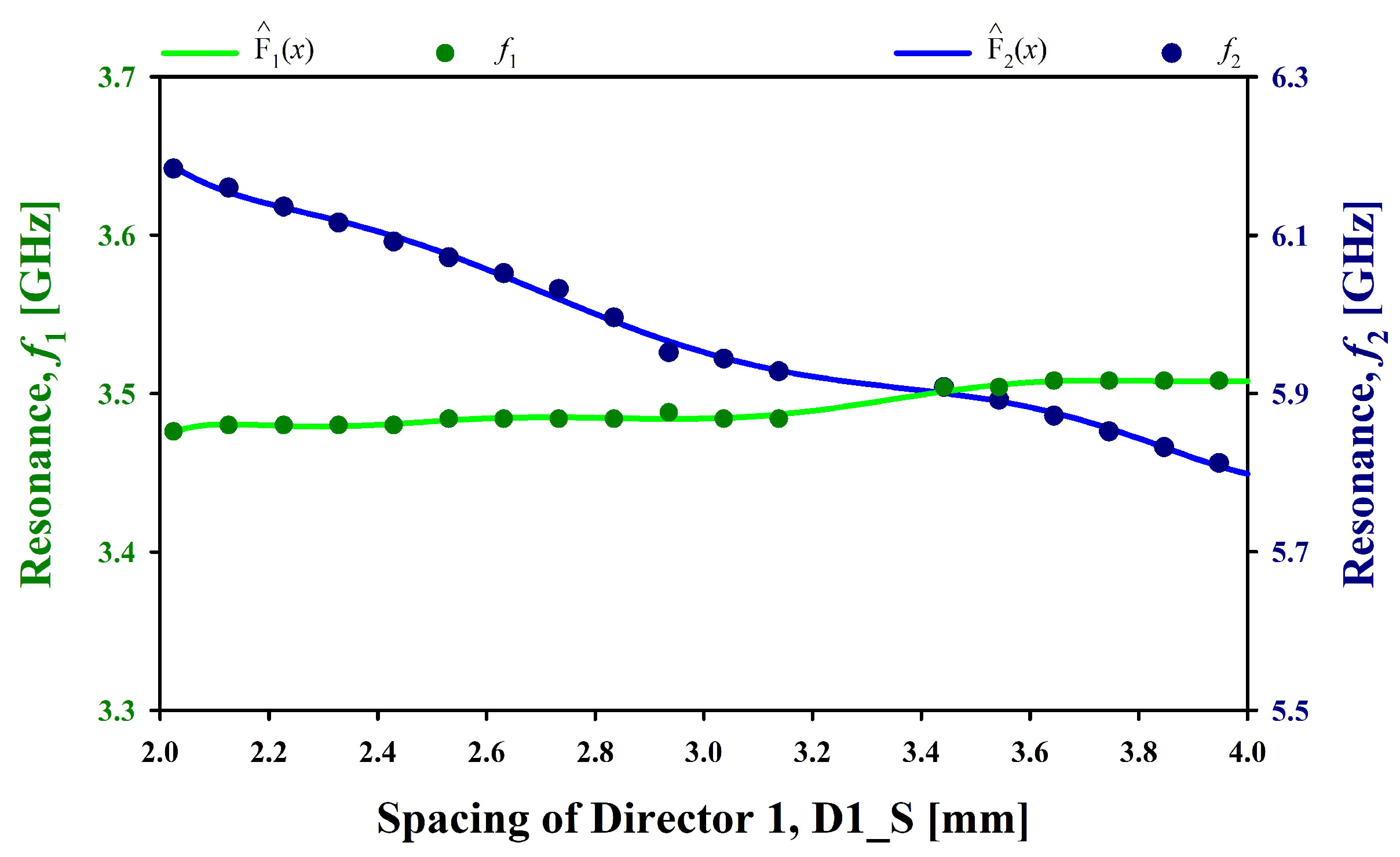

| D1_S | 3476 — 3508 | 5792 — 6184 | |

| 2 mm — 4 mm | |||

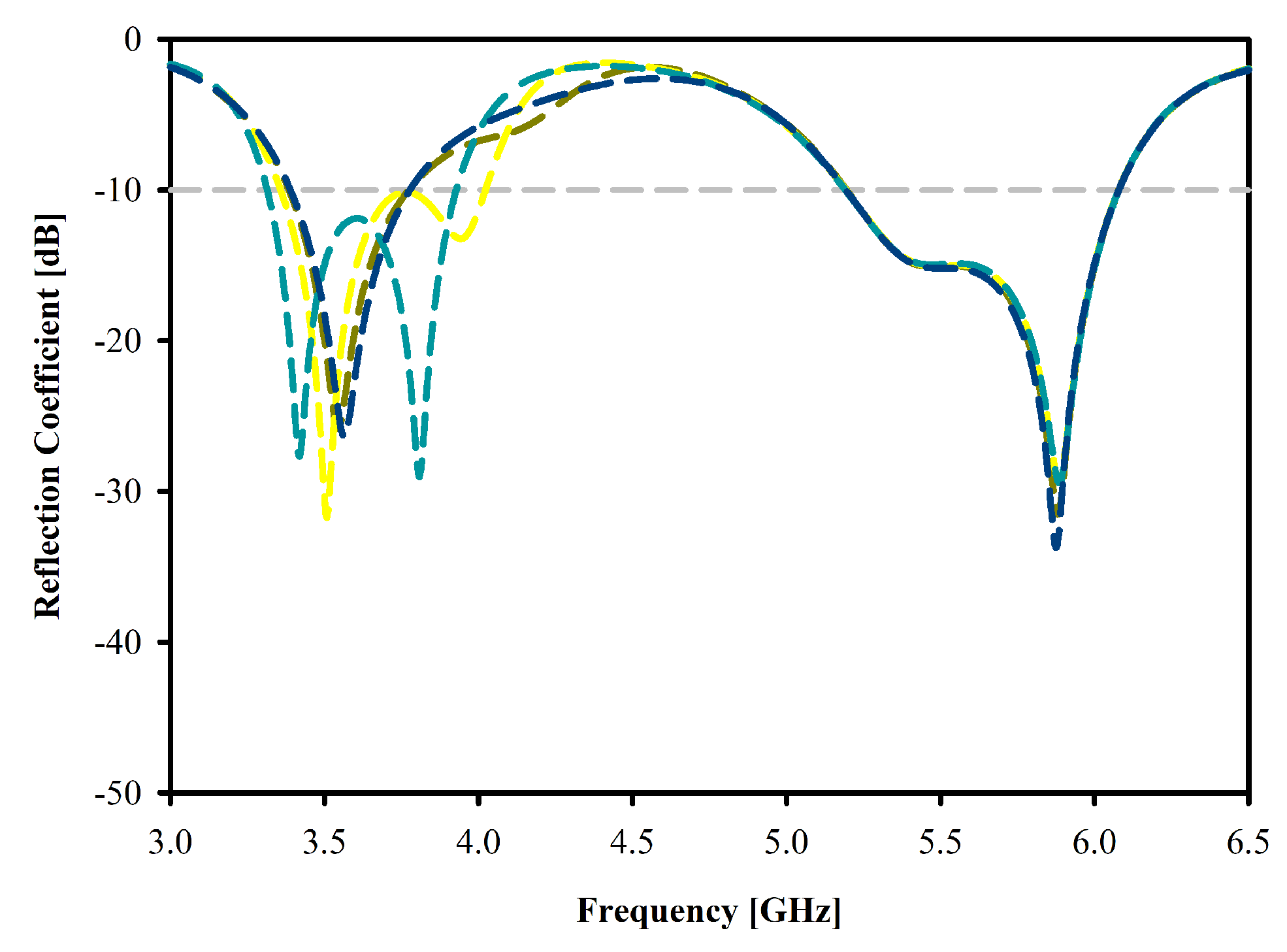

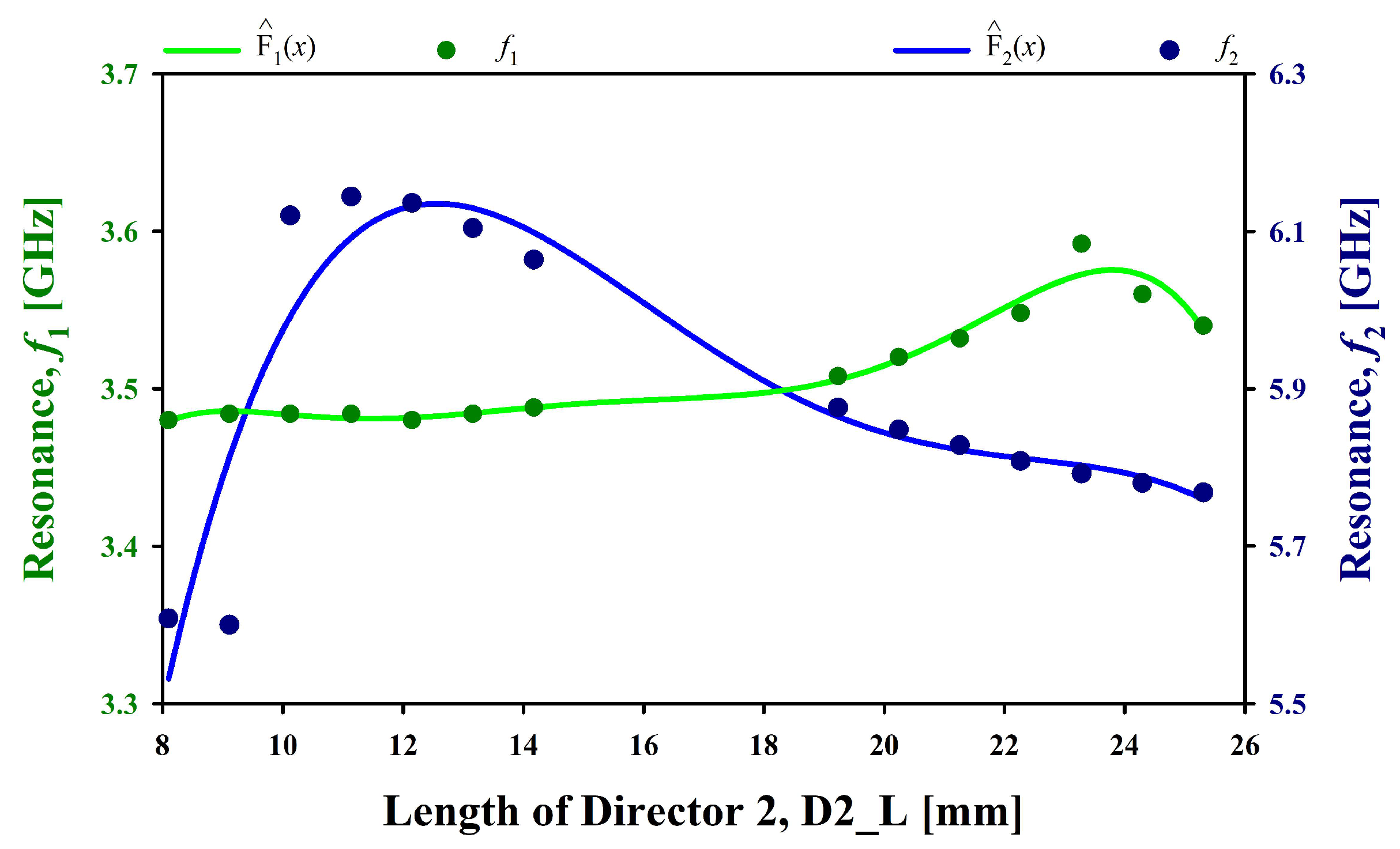

| Director 2 | D2_L | 3480 — 3592 | 5600 — 6144 |

| 8 mm — 26 mm | |||

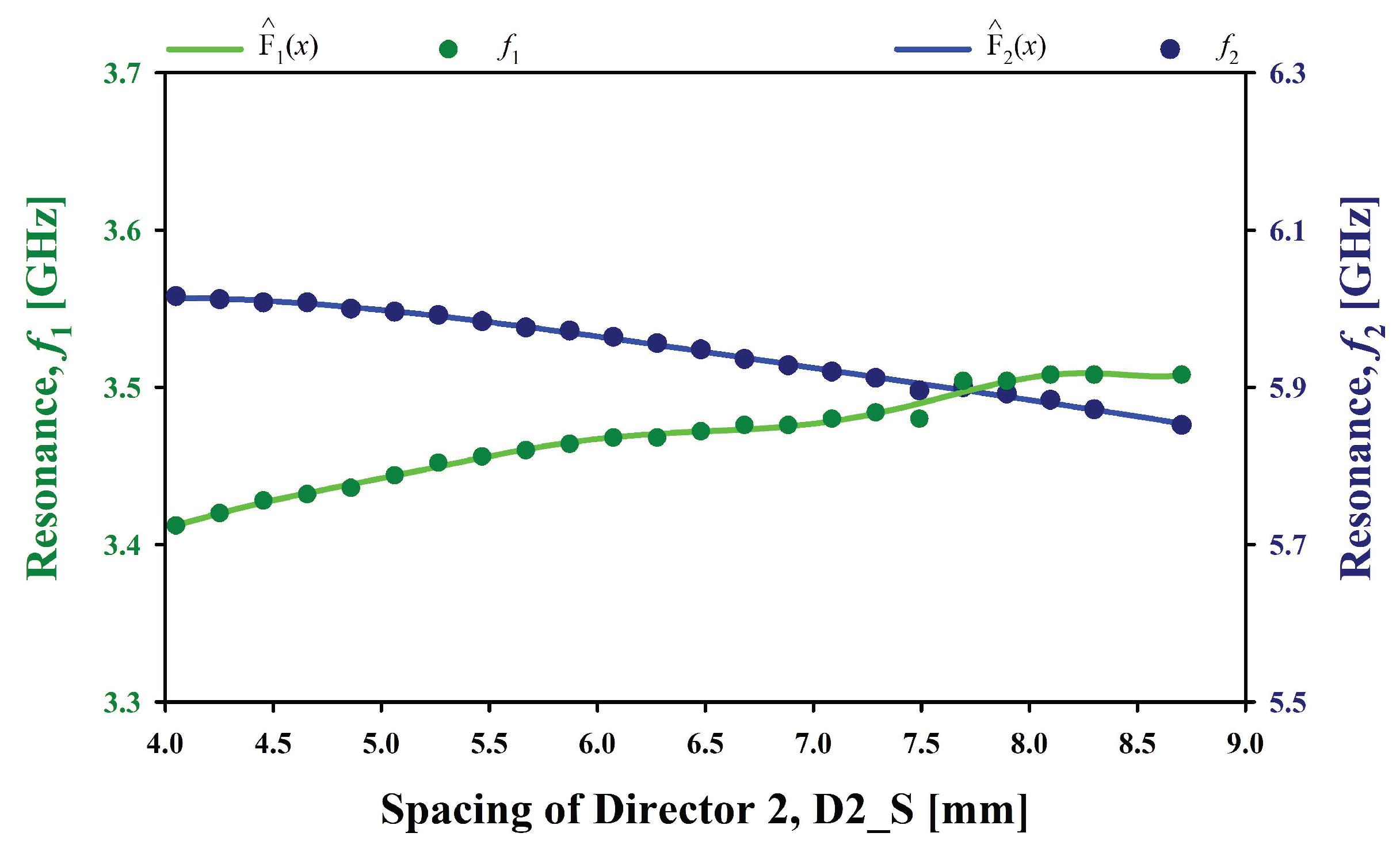

| D2_S | 3412 — 3512 | 5820 — 6016 | |

| 4 mm — 9 mm | |||

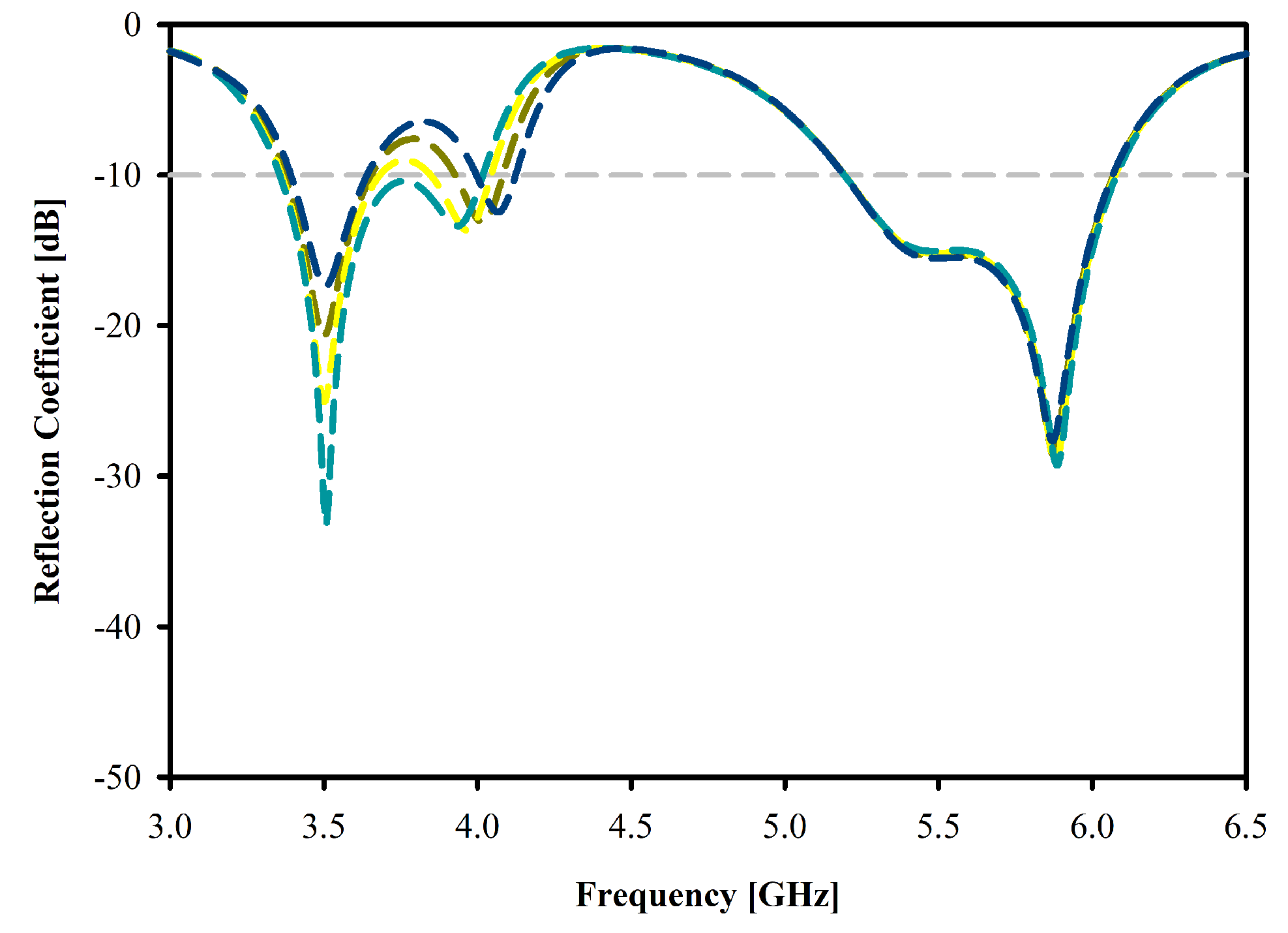

| Director 3 | D3_L | 3396 — 3580 | 5872 — 5884 |

| 8 mm — 29 mm | |||

| D3_S | 3500 — 3508 | 5872 — 5884 | |

| 10 mm — 16 mm | |||

| Ref | Frequency (GHz) | Bandwidth (GHz) | Efficiency (%) | Peak Gain (dBi) | Size () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [49] | 3.5, 5.9 | 3.23 - 6.26 | 92 | 5.9 | 0.9×0.35 |

| [47] | 5.9 | 0.4 | 94 | 7.68 | 1.46×1.46 |

| [48] | 5,6 | 4.77 - 6.31 | 93.2 | 4.2 | 3.93×2.95 |

| This Study | 3.5, 5.9 | 0.7, 0.9 | 90.1, 78.4 | 7.55, 4.45 | 0.44×0.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).