1. Introduction

Currently, digitalization and automation processes that use machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms cover almost all areas of activity. Road markings are no exception: their classification, including pedestrian crossings, speed bumps, and lane dividers, plays an important role in the improvement of autonomous vehicles and intelligent transportation systems. These markings play an important role in vehicle navigation, helping as visual signs that promote road safety and compliance with traffic rules. To make autonomous transport systems work well in different situations, even when lighting is bad or markings are worn, we need accurate and reliable classification algorithms [

1,

2]. Inaccuracies in the classification of these objects can cause significant navigation errors, which pose a threat to both safety and efficiency. For example, if the system fails to recognize a pedestrian crossing or speed bump, the driver may make a risky decision that could be unsafe. Incorrect identification of lane dividers can also cause problems in systems designed to keep the vehicle in its lane [

3,

4].

Image classification relies heavily on convolutional neural networks (CNNs). This is due to their ability to extract hierarchical features directly from visual data [

5]. Baseline CNNs, created and trained from zero, often demand massive collections of labeled data to get satisfactory performance [

2,

6]. When classifying road markings, collecting and labeling such data becomes a serious challenge due to the diversity of road conditions and the significant effort required for manual annotation [

7]. Furthermore, conventional CNNs may have difficulty generalizing the data they learn from, especially when the amount of training data is limited [

8]. This can lead to overfitting and reduced performance in real-world conditions. Transfer learning methods are suggested, as an alternative. This method relies on pre-trained models such as MobileNetV2, ResNet, and similar models that have been pre-trained on large datasets such as ImageNet. Such models can be adapted for specific tasks, reducing the need for large amounts of new training data and improving overall accuracy [

9,

10]. Transfer learning has been successfully applied to different tasks, including classification and object recognition in different areas, such as flower recognition, text analysis, and airplane model identification [

11,

12,

13]. These examples demonstrate the potential of transfer learning to work with limited data and environmental variability. For example, a study by Khan and Khan [

14] shows that transfer learning using the VGG16 architecture is effective for classifying MRI images of brain tumors. This result indicates the applicability of transfer learning in medical imaging tasks and confirms its relevance for road marking classification in the context of this study.

There have been notable results in the field of road marking recognition [

15], but there is a lack of work devoted to the comparative analysis of CNN networks and transfer learning methods in multi-class classification tasks. In particular, there is no systematic comparison of these approaches for the simultaneous identification of pedestrian crossings, speed bumps, and dividing lines. Analysis of the available literature shows that existing work tends to focus on individual types of road markings [

7,

16]. This gap is important in the context of autonomous driving, where systems must quickly and accurately recognize different types of road markings. Accurate classification is necessary to ensure safe and efficient navigation, as it allows the vehicle to respond appropriately to the road situation. Thus, for the further development of autonomous driving systems, research is needed to develop comprehensive models capable of multi-class classification of different types of road markings. Comparing basic CNNs and transfer learning methods within a unified architecture will help identify the most productive and effective approaches, which in turn will contribute to the creation of more advanced and safer autonomous vehicle control systems.

The goal of this study is to compare the performance of a convolutional neural network (CNN) with transfer learning. Transfer learning uses a pre-trained EfficientNetB0 model trained on the ImageNet database. The comparison is done for classification of road markings, such as pedestrian crossings, speed bumps, and lane dividers. The effectiveness of each model is evaluated according to several criteria, including classification accuracy, training time, and the ability to generalize in real-world conditions. The results of this comparison should provide a basis for selecting the optimal model, taking into account computational resource constraints. The main aspect of the study is to compare these approaches and identify their strengths and weaknesses in relation to multi-class classification of road markings. It is assumed that the transfer learning method using the pre-trained EfficientNetB0 model will provide higher accuracy and reliability overall compared to the basic CNN. This is because transfer learning model is already trained on a large dataset, which makes better generalization even with small data for a specific task. The research is based on the following question: how does transfer learning using the pre-trained EfficientNetB0 model improve the accuracy of road markings classification (in particular, pedestrian crossings, speed bumps, and dividing strips) compared to using a baseline CNN?

2. Methods

This research uses quantitative experimental method [

17] to compare how well a baseline CNN and a transfer learning model with EfficientNetB0 classify road markings like pedestrian crossings, speed bumps, and lane dividers. The experiment is set up to be repeatable, using a dataset created for this specific purpose and evaluations that are statistically sound. All experiments were done in Python using TensorFlow/Keras in Google Colab. The sections that follow give the details of the research setup, the data, the model designs, and the experimental process.

2.1. Research Design

This study uses a quantitative experimental method to test how well two models classify images in a custom dataset of road markings. The main goal is to compare a basic CNN model, trained from scratch, with a transfer learning method that uses pre-existing features. Performance is measured through quantitative metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, computed on both validation and test sets. The dataset was made using purposive sampling, a non-probability sampling technique, to intentionally select images that represent the three target classes under various real-world conditions. This method makes sure that the dataset is relevant for autonomous driving systems while remaining feasible for a resource-constrained study. The experiment involves controlled training methods, standard ways of preparing the images, and consistent methods for judging the models. This will allow a fair comparison between them.

2.2. Dataset

The dataset was collected by the author through direct photography of road markings in public spaces, adhering to local regulations and ethical guidelines. No personally identifiable information is included, and all images were captured in compliance with public domain usage or explicit permissions where required. The dataset has 708 images, split into three groups: lane dividers (227 images), pedestrian crossings (231 images), and speed bumps (250 images). A separate test set of 75 images, with equal numbers from each group, was reserved for the final check to ensure fair results.

Images were taken using a smartphone with a 50 MP camera in different daylight situations. Purposive sampling [

18] focused on choosing images that represent typical road marking appearances in autonomous driving scenarios, such as clear or slightly faded markings, while avoiding extreme conditions like heavy rain or nighttime. This method balanced how well the images represented actual conditions with the limits of time and logistics, which kept the dataset from being larger or more diverse.

Preprocessing standardized all images to 224x224 pixels to match model input requirements. For the baseline CNN, pixel values were normalized by dividing by 255. For EfficientNetB0, the model-specific preprocessing function (from TensorFlow’s Keras applications) was applied, which centers and scales pixel values based on ImageNet statistics. Data augmentation was critical to enhance generalization, especially given the dataset’s modest size. Augmentation techniques included random horizontal flipping, brightness adjustments (factor 0.2), contrast adjustments (factor 0.2), rotations (±10 degrees), and zooming (factor 0.1). These transformations simulate real-world variations, reducing overfitting and improving robustness.

The dataset was split into 70% training (approximately 495 images) and 30% validation (approximately 213 images) using stratified sampling to maintain class balance. A TensorFlow `tf.data.Dataset` pipeline was used for efficient loading, shuffling, batching, and prefetching. Balanced class weights were computed to address minor class imbalances (e.g., speed bumps slightly overrepresented).

Table 1 summarizes the dataset characteristics.

2.3. Baseline CNN

The baseline CNN is a custom sequential Keras model designed for simplicity and suitability in resource-constrained environments, based on the standard CNN architecture [

19]. It accepts input images of shape (224, 224, 3) and begins with in-line data augmentation layers: RandomFlip (horizontal), RandomBrightness (0.2), RandomContrast (0.2), RandomRotation (0.1 radians), and RandomZoom (0.1). These layers dynamically augment training images to improve generalization without increasing storage requirements.

The core architecture consists of four convolutional blocks: each includes a Conv2D layer (32, 64, 128, 256 filters, respectively; 3x3 kernels; ReLU activation), BatchNormalization for training stability, and MaxPooling2D (2x2 kernel, stride 2) for dimensionality reduction. The choice of increasing filter sizes captures progressively complex features, while batch normalization mitigates vanishing gradients. The feature maps are flattened, followed by a Dense layer (512 units, ReLU, L2 regularization with weight 0.01 to prevent overfitting), a Dropout layer (0.7), and a final Dense layer (3 units, softmax) for classification.

Table 2.

Architecture Overview of the Baseline CNN Model.

Table 2.

Architecture Overview of the Baseline CNN Model.

| Component |

Output Shape |

Parameters |

| Input + Augmentation |

(224, 224, 3) |

0 |

| Conv2D (32 filters) + BN + MaxPool |

(112, 112, 32) |

9,200 |

| Conv2D (64 filters) + BN + MaxPool |

(56, 56, 64) |

37,900 |

| Conv2D (128 filters) + BN + MaxPool |

(28, 28, 128) |

150,600 |

| Conv2D (256 filters) + BN + MaxPool |

(14, 14, 256) |

295,200 |

| Flatten |

(50176) |

0 |

| Dense (512, ReLU, L2 0.01) + Dropout (0.7) |

(512) |

25,690,000 |

| Dense (3, Softmax) |

(3) |

1,539 |

| Total Parameters |

|

26,185,439 |

| Trainable Parameters |

|

26,185,439 |

| Non-trainable Parameters |

|

0 |

Training Configuration:

Optimizer: RMSprop with a learning rate of 0.001 ensures stable and efficient training.

Batch Size: 32 balances memory usage and training speed, suitable for the dataset size.

Epochs: Up to 20, with early stopping after 10 epochs if validation performance plateaus.

-

Callbacks:

- −

EarlyStopping: Tracks validation loss, stopping training after 10 epochs without improvement and restoring the best weights.

- −

ModelCheckpoint: Saves the model with the highest validation accuracy.

- −

ReduceLROnPlateau: Reduces the learning rate by half if validation loss stalls for 3 epochs, with a minimum of 0.000001.

2.4. Transfer Learning

The transfer learning method uses the pre-trained EfficientNetB0 model [

20] because of its efficiency with small datasets. Initially trained on ImageNet, this model is adapted for classifying road markings—lane dividers, pedestrian crossings, and speed bumps—by freezing its base layers to preserve learned features like edges and textures. A custom classification head is added to fine-tune the model for our specific task.

Custom Classification Head Design:

Global Average Pooling (GAP) condenses feature maps into a 1280-dimensional vector, reducing computational complexity.

A dense layer with 256 neurons uses ReLU activation and a 0.5 dropout rate to enhance generalization and prevent overfitting.

A final output layer with 3 neurons and softmax activation provides class probabilities for lane dividers, pedestrian crossings, and speed bumps.

Table 3.

Architecture Overview of the Fine-Tuned EfficientNetB0 Model.

Table 3.

Architecture Overview of the Fine-Tuned EfficientNetB0 Model.

| Component |

Output Shape |

Parameters |

| EfficientNetB0 (Base, Frozen) |

(None, 7, 7, 1280) |

4,049,571 (non-trainable) |

| Global Average Pooling (GAP) |

(None, 1280) |

0 |

| Dense (256 neurons, ReLU, Dropout 0.5) |

(None, 256) |

327,936 |

| Dense (3 neurons, Softmax) |

(None, 3) |

771 |

| Total Parameters |

|

4,378,278 |

| Trainable Parameters |

|

328,707 |

| Non-trainable Parameters |

|

4,049,571 |

Training Configuration:

Optimizer: Adam with a learning rate of 0.0001 ensures stable and efficient training.

Batch Size: 32 balances memory usage and training speed, suitable for the dataset size.

Epochs: Up to 10, with early stopping after 7 epochs if validation performance plateaus.

-

Callbacks:

- −

EarlyStopping: Tracks validation loss, stopping training after 10 epochs without improvement and restoring the best weights.

- −

ModelCheckpoint: Saves the model with the highest validation accuracy.

- −

ReduceLROnPlateau: Reduces the learning rate by half if validation loss stalls for 3 epochs, with a minimum of 0.000001.

2.5. Experimental Setup

Both models were trained using a tf.data.Dataset pipeline with a batch size of 32, optimized for computational efficiency and suitable for the dataset size. The baseline CNN was trained for 20 epochs, while the transfer learning approach with EfficientNetB0 was trained for 10 epochs, incorporating early stopping to ensure convergence given its pre-trained initialization. Both models used balanced class weights to address minor imbalances and employed callbacks: ModelCheckpoint (save the best model based on validation accuracy), EarlyStopping (monitor validation loss, patience 10, restore best weights), and ReduceLROnPlateau (monitor validation loss; factor 0.2 for baseline, 0.5 for transfer; patience 3; minimum learning rate 0.000001).

3. Results

Performance metrics for both models are shown in

Table 4. The baseline CNN achieved 56.3% validation accuracy and 66.7% test accuracy with a macro F1-score of 0.672. The EfficientNetB0 transfer learning model achieved 100% validation accuracy and 93.3% test accuracy with a macro F1-score of 0.932.

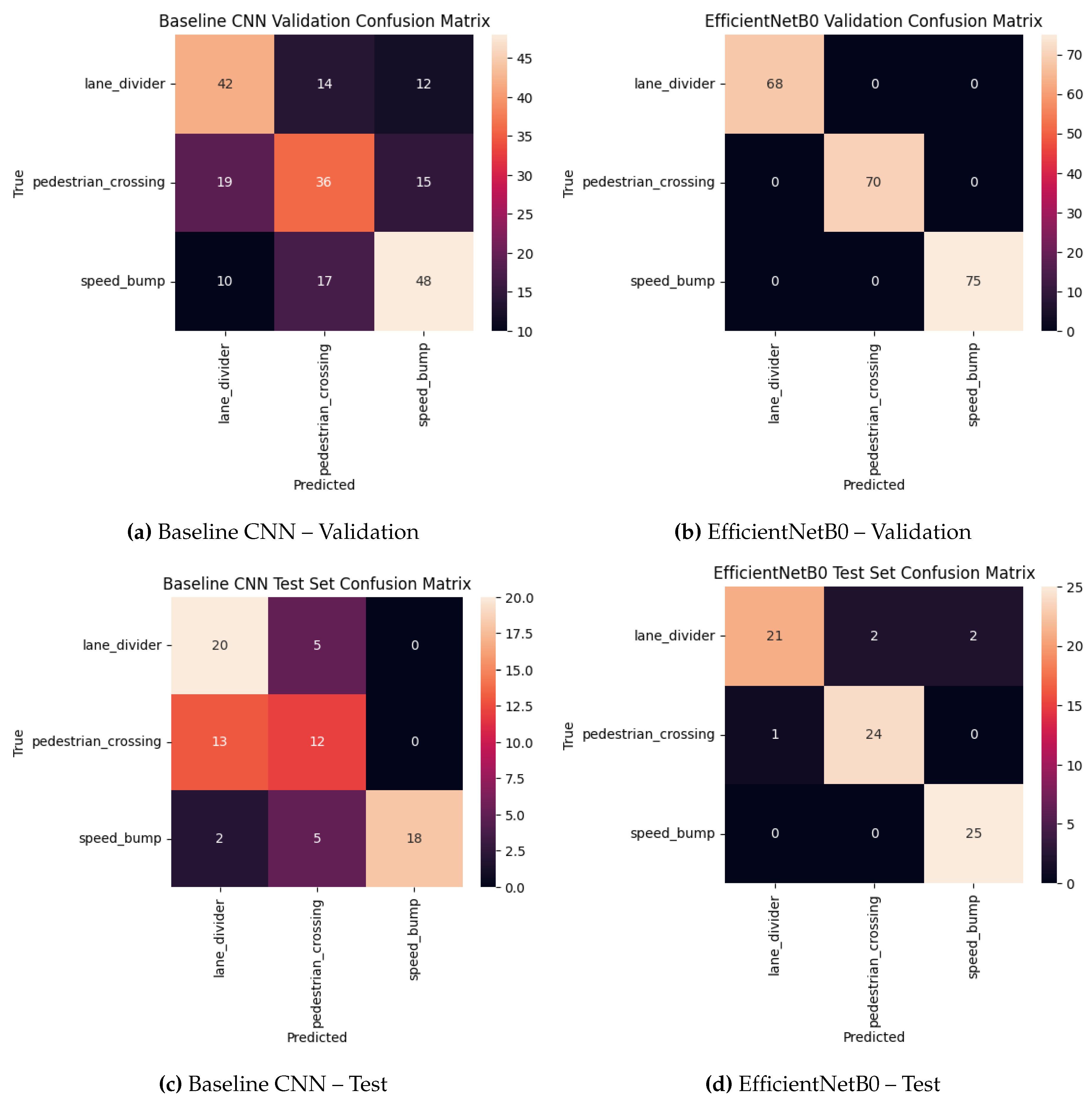

Confusion matrices are shown in

Figure 1. The baseline CNN validation set shows 42 correct lane dividers, 36 correct pedestrian crossings and 48 correct speed bumps with significant off-diagonal confusion. The EfficientNetB0 validation set shows perfect classification. On the test set, EfficientNetB0 correctly classified 21 lane dividers, 24 pedestrian crossings and 25 speed bumps with 4 minor errors.

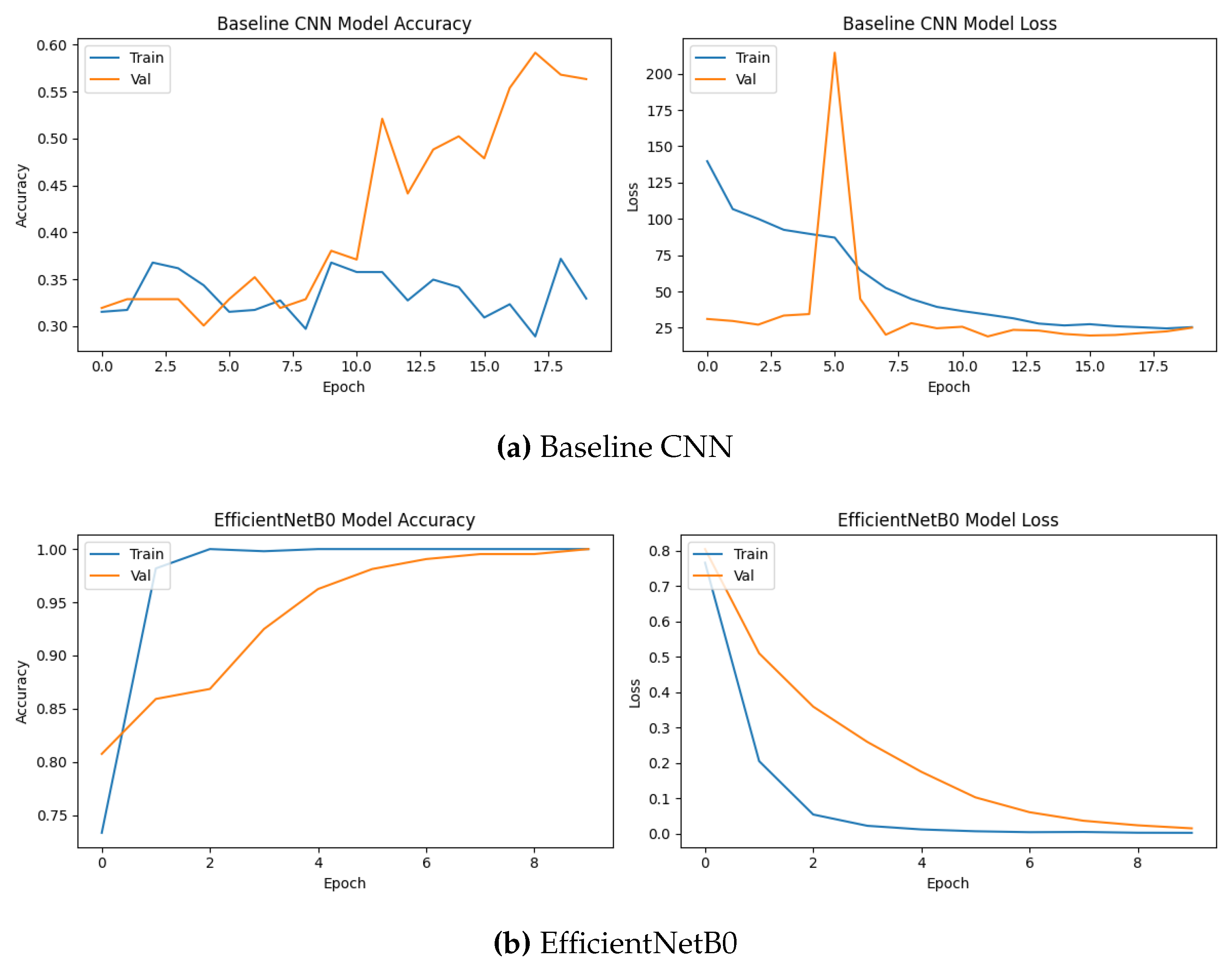

Training and validation curves are shown in

Figure 2. The baseline CNN accuracy levels off below 0.6 with high variance. The EfficientNetB0 model reaches 1.0 validation accuracy in 8 epochs.

Examples of model predictions are shown in

Figure 3. The baseline CNN often misclassified speed bumps as lane dividers or pedestrian crossings. The EfficientNetB0 model correctly classified all shown examples.

4. Discussion

The results show that transfer learning with EfficientNetB0 performed better than the baseline CNN trained from scratch in the multi-class classification of road markings. The EfficientNetB0 model achieved perfect validation accuracy (100%) and 93.3% test accuracy with a macro F1-score of 0.932, compared to 56.3% validation accuracy, 66.7% test accuracy, and a macro F1-score of 0.672 for the baseline CNN. This 26.6 percentage point improvement in test accuracy and 0.26 increase in macro F1-score shows the advantage of pre-trained models on limited dataset specific to a certain field.

The poor performance of the baseline CNN is due to overfitting and inefficient feature extraction capacity on a small dataset. As shown in

Figure 1, the validation confusion matrix shows systematic misclassifications, particularly of speed bumps, which were often confused with lane dividers or pedestrian crossings. These errors are visually explained in

Figure 3, where shadows, motion blur, and low contrast under real-world conditions create visual uncertainty. In contrast, EfficientNetB0 correctly classified all validation instances and made only minor errors in the test set, demonstrating a reliable generalization using hierarchical feature learning.

These results are consistent with previous research on transfer learning in computer vision, which shows that pre-trained models accelerate convergence and improve accuracy based on limited data. However, this work expands the literature by providing a systematic comparison of the baseline CNN and transfer learning for the multi-class classification of pedestrian crossings, speed bumps, and lane dividers in real-world conditions, a task that had not previously been considered in a single system. Although single-class detection of speed bumps [

4] or lane dividers [

2] has achieved high accuracy using deep learning, combining all three classes increases complexity due to visual overlap and environmental variability.

The results have a few limits that suggest directions for further investigation. The small dataset only included daylight and twilight conditions and did not have nighttime or bad weather. It also used purposive sampling, which could create bias. The test set was also small, with just 75 images, though it was balanced across different categories. The baseline CNN didn’t have enough parameters, and no advanced data augmentation was used. Future work should focus on expanding the dataset to include different environmental conditions, more road marking classes, and testing real-time inference on hardware. Experiments on data expansion and combining methods could improve error resistance.

References

- Mamun, A.A.; Ping, E.P.; Hossen, J.; Tahabilder, A.; Jahan, B. A comprehensive review on lane marking detection using deep neural networks. Sensors 2022, 22, 7682. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Gelernter, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Lane marking detection via deep convolutional neural network. Neurocomputing 2018, 280, 46–55. [CrossRef]

- Tümen, V.; Ergen, B. Intersections and crosswalk detection using deep learning and image processing techniques. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2020, 543, 123510. [CrossRef]

- Darwiche, M.; El-Hajj-Chehade, W. Speed bump detection for autonomous vehicles using signal-processing techniques. BAU Journal-Science and Technology 2019, 1, 5. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Sawale, M. A review on image classification using deep learning. World J Adv Res Rev 2023, 17, 480–2.

- Chen, T.; Chen, Z.; Shi, Q.; Huang, X. Road marking detection and classification using machine learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE, 2015, pp. 617–621. [CrossRef]

- Arunpriyan, J.; Variyar, V.S.; Soman, K.; Adarsh, S. Real-time speed bump detection using image segmentation for autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Information and Control Systems. Springer, 2019, pp. 308–315.

- Rezapour, M.; Ksaibati, K. Convolutional neural network for roadside barriers detection: Transfer learning versus non-transfer learning. Signals 2021, 2, 72–86. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Bird, J.J.; Faria, D.R. A study on CNN transfer learning for image classification. In Proceedings of the UK Workshop on computational Intelligence. Springer, 2018, pp. 191–202. [CrossRef]

- Shaha, M.; Pawar, M. Transfer learning for image classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 second international conference on electronics, communication and aerospace technology (ICECA). IEEE, 2018, pp. 656–660.

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, T.; Ouyang, C. End-to-end airplane detection using transfer learning in remote sensing images. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 139. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Qin, X.; Pan, Y.; Yuan, C. Convolution neural network based transfer learning for classification of flowers. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 3rd international conference on signal and image processing (ICSIP). IEEE, 2018, pp. 562–566.

- Qasim, R.; Bangyal, W.H.; Alqarni, M.A.; Ali Almazroi, A. A fine-tuned BERT-based transfer learning approach for text classification. Journal of healthcare engineering 2022, 2022, 3498123. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Khan, M.T. Transfer Learning for Brain Tumor MRI Classification Using VGG16: A Comparative and Explainable AI Approach, 2025.

- Doğan, G.; Ergen, B. A new hybrid mobile CNN approach for crosswalk recognition in autonomous vehicles. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 67747–67762. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Ö.; Çodur, M.Y.; Mustafaraj, E. Automatic detection of pedestrian crosswalk with faster r-cnn and yolov7. Buildings 2023, 13, 1070. [CrossRef]

- Weyant, E. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches: by John W. Creswell and J. David Creswell, Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2018, 38.34, 304pp., ISBN: 978-1506386706, 2022.

- Rai, N.; Thapa, B. A study on purposive sampling method in research. Kathmandu: Kathmandu School of Law 2015, 5, 8–15.

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 2002, 86, 2278–2324. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 6105–6114.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).