1. Introduction

Nasal bone fracture is the most common facial fracture. Closed reduction benefits from real-time visualization of cortical discontinuities and step-offs. High-resolution ultrasonography (US) provides such guidance without ionizing radiation and shows diagnostic utility in both pediatric and adult populations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

On the curved nasal dorsum, near-field performance depends on the acoustic medium at the probe–skin interface. Micro-air interfaces and unstable contact diminish contrast and obscure thin cortical lines. Water-bath coupling can provide wide-field views but is vulnerable to bubbles, meniscus curvature, and motion during manipulation, limiting intraoperative practicality [

6].

From an acoustic standpoint, soft-tissue–air boundaries reflect most incident energy; uninterrupted, air-free coupling is therefore essential. Bench studies favor gel-based media for transmissivity and impedance matching compared with water or oils [

7,

8,

9]. For superficial targets, standoff pads extend the effective near field and stabilize contact; clinical reports describe improved Doppler detectability and preserved elastography performance with pad interposition [

10,

11].

We aimed to determine whether a semi-solid standoff gel pad (PAD) confers superior resolution relative to a liquid gel barrier (LGB) in nasal bone fracture sonography, using a standardized acquisition protocol and an objective image-based contrast surrogate under fixed presets [

12,

13,

14].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objective and Design

This prospective, single-center, within-subject standardized crossover study was designed to evaluate whether the choice of acoustic coupling medium affects image resolution in nasal bone fracture sonography. Each patient with an isolated nasal bone fracture underwent high-frequency ultrasound (US) of the nasal dorsum under two conditions that differed only by the coupling medium: a semi-solid standoff gel pad (PAD) and a liquid gel barrier (LGB). The primary objective was to compare the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) at the cortical interface between PAD and LGB during intraoperative sonography for closed reduction. Secondary objectives were to compare signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) of the cortical and adjacent soft-tissue regions of interest (ROIs) under the two media.

2.2. Participants

Adults (≥18 years) with isolated nasal bone fractures scheduled for closed reduction were eligible. Exclusion criteria were: (i) concomitant facial fractures, (ii) open wounds or skin conditions precluding safe application of coupling media over the nasal dorsum, (iii) prior nasal surgery within 6 months, and (iv) inability to cooperate with the intraoperative US protocol (e.g., inability to maintain supine position). Thirty consecutive patients who satisfied these criteria and completed imaging under both coupling conditions were included in the analysis.

2.3. Order of Conditions and Masking

To standardize acquisition and reduce variability related to repositioning and residual gel, all participants were scanned in a fixed sequence: PAD followed by LGB. Between conditions, the nasal skin was thoroughly wiped and dried to remove residual gel and minimize carryover. The sonographer could not be blinded to the coupling medium; however, all exported images were anonymized and re-labeled before analysis. Two independent readers were available, but for the present study a single trained reader performed ROI placement and intensity measurements to minimize inter-reader variability; a random subsample (20%) was re-measured to verify intra-reader consistency (data not shown).

2.4. Ultrasound System and Acquisition Presets

All examinations were performed using a ZONARE US platform equipped with a linear L14-5w transducer (operating range 5–14 MHz, approximately 55 mm field of view, multiple discrete frequency settings). Imaging was carried out in 2D B-mode only. Acquisition parameters were held constant for both PAD and LGB conditions: depth 4.0 cm, transmit frequency 10 MHz, single focal zone positioned at the cortical interface, dynamic range 75 dB, overall gain 76, and tissue harmonic, compound imaging, persistence, and other post-processing filters switched OFF. These fixed presets were chosen to emphasize superficial cortical detail. Images were exported as DICOM or uncompressed PNG in 8-bit (0–255) without additional window/level adjustment.

2.5. Coupling Media

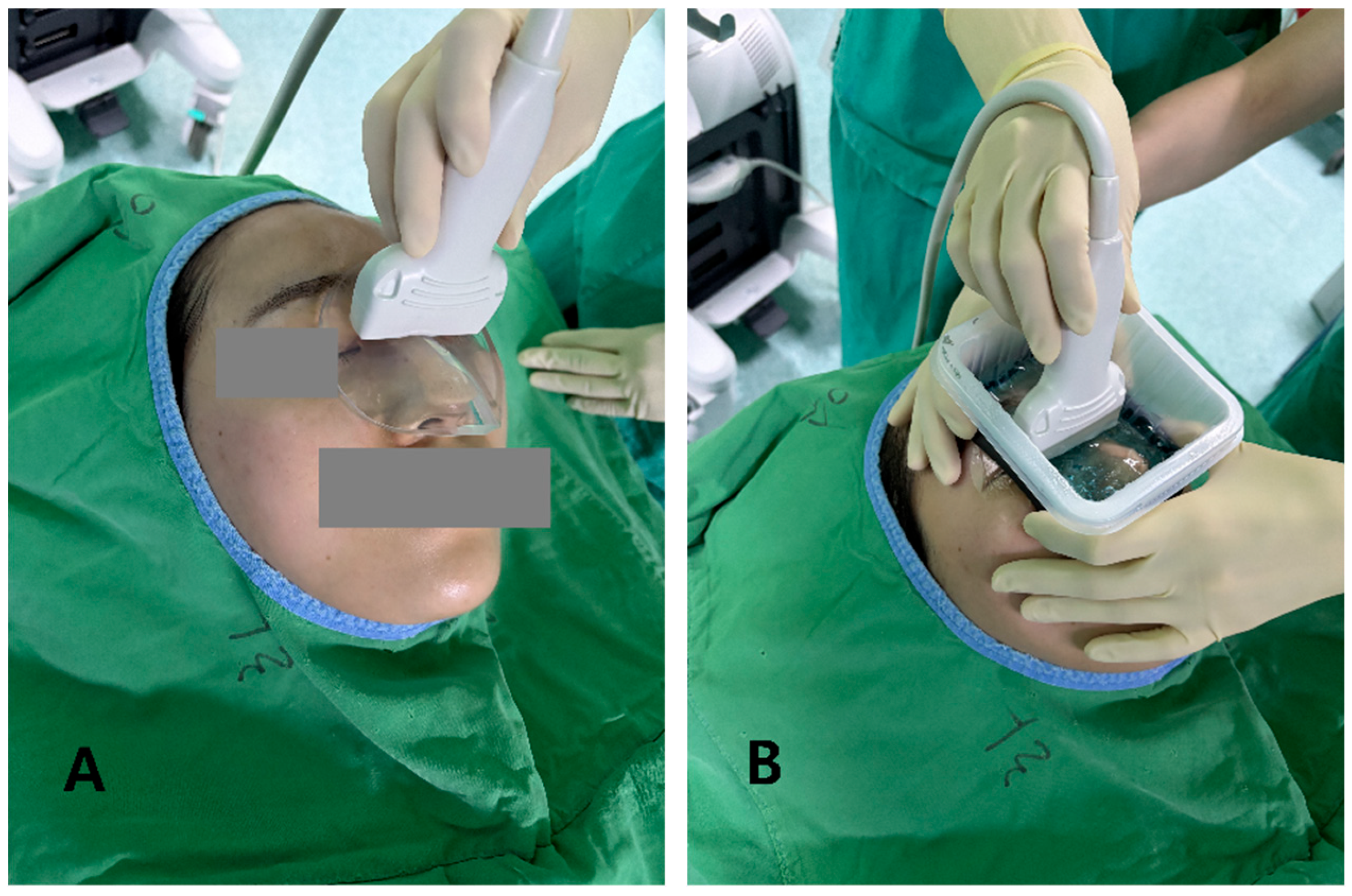

Standoff gel pad (PAD): A medical-grade hydrogel standoff pad (thickness 7 mm, diameter approximately 90 mm; SOLID GEL PAD®, Bluemtech, Korea) was centered over the nasal dorsum, with a thin smear of standard ultrasound gel applied only to wet the skin–pad interfaces. The pad thickness was selected to place the nasal cortex within the proximal near field of the 14-MHz transducer while providing a stable, conformal contact surface.

Liquid gel barrier (LGB): To create an LGB, we assembled a shallow perinasal plastic container by affixing a narrow band of waterproof closed-cell sponge to the inner rim of a circular plastic ring. This assembly was secured to the perinasal skin using a transparent adhesive drape, forming a low-profile, sealed reservoir that confined the gel around the nasal dorsum. Approximately 10 mL of sterile ultrasound gel was injected through a luer-lock port while a small air vent ensured evacuation of bubbles, targeting a gel layer thickness of ~7 mm. The LGB was designed to mimic a liquid near-field standoff while matching the PAD in effective depth and footprint so that differences in image quality predominantly reflected the medium state (semi-solid vs liquid) (

Figure 1).

2.6. Image Acquisition Protocol and Handling

With the patient in the supine position and the head slightly elevated, the transducer was oriented longitudinally along the nasal dorsum. For each condition, a short (approximately 3-s) linear sweep was recorded over the central dorsum without changing presets. The same operator performed all acquisitions and was instructed to apply the minimum pressure required to maintain consistent contact, thereby minimizing probe-induced deformation of the nasal framework. After completion of the PAD sequence, the perinasal skin was cleaned, the LGB was applied as described above, and the LGB acquisition was performed with identical probe orientation and sweep path.

2.7. ROI Placement for CNR/SNR Measurements

All ROI-based analyses were performed in FIJI/ImageJ (v1.52). For each subject and condition, one representative PAD image and one representative LGB image were selected from the recorded cine loops, prioritizing frames in which the cortical surface was sharp and free of motion or obvious artifacts.

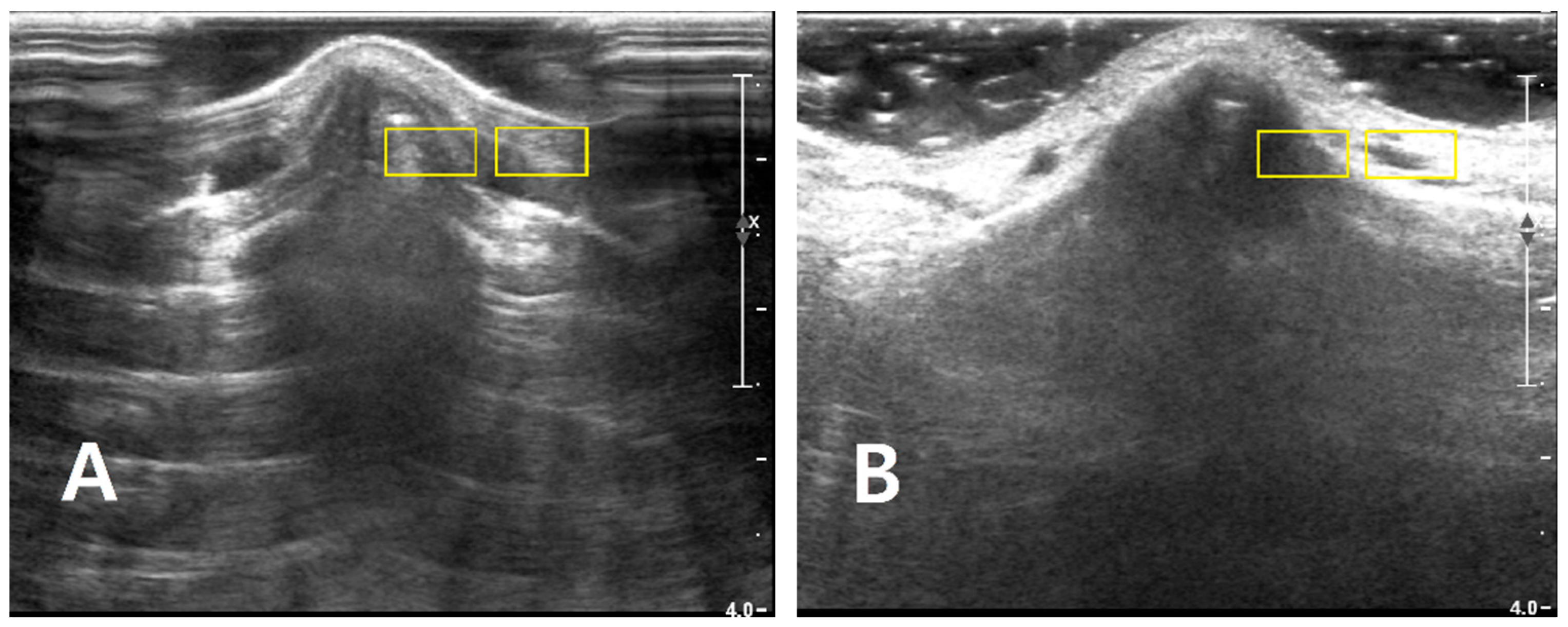

Two rectangular ROIs were defined at a fixed depth and orientation on the PAD image and then reapplied to the LGB image with only minor adjustments to maintain alignment: Cortical ROI (ROI_bone): A small rectangle (approx. 6 × 3 mm) confined to the bright cortical band at the nasal dorsum, avoiding saturated pixels (intensity = 255) and excluding overlying reverberation or shadowing. Adjacent soft-tissue ROI (ROI_soft): A rectangle of similar size placed 1–2 mm lateral to the cortical ROI at the same depth, sampling homogeneous soft tissue without visible artifacts (

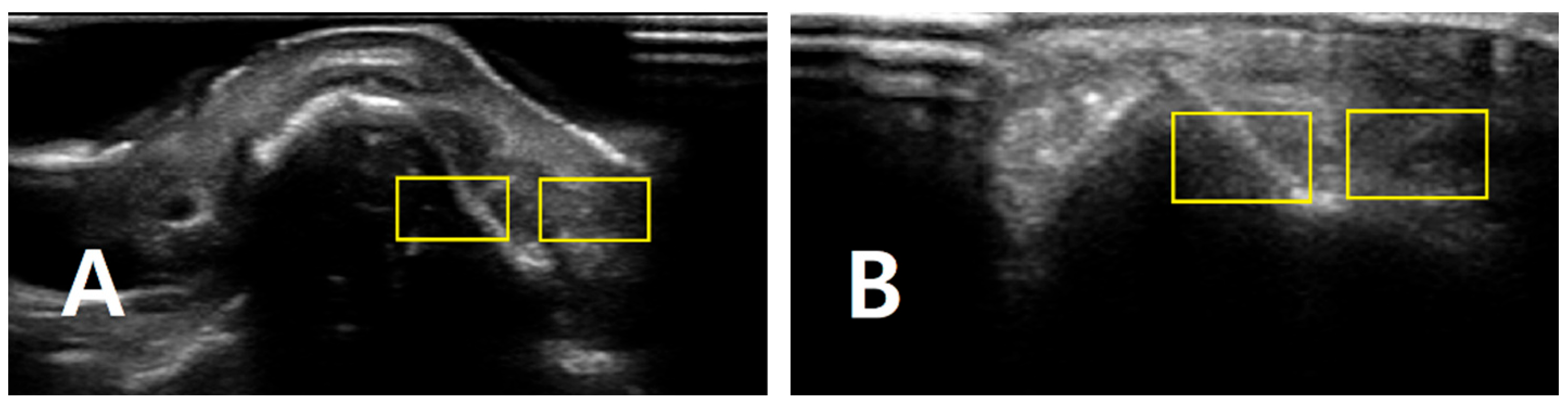

Figure 2). The exact lateral position of the ROIs was adjusted so that, in both PAD and LGB images, ROI_bone and ROI_soft remained aligned to the same anatomical level (depth mismatch ≤0.5 mm; angular mismatch ≤5°). For subjects with cine data, the same ROIs were propagated across five consecutive frames: the frame with the highest mean intensity within ROI_bone and its two preceding and two subsequent frames. For each frame, the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of the 8-bit gray-level values were recorded for ROI_bone and ROI_soft. For subjects with only static images available, ROI_bone and ROI_soft were repositioned across three to five adjacent locations along the same cortical segment, and measurements were averaged (

Figure 3).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

For each subject and each condition (PAD and LGB), the frame-level or spatial replicate measurements from the two ROIs were averaged so that one value per subject and condition was used in the analysis. The cortical ROI (“bone ROI”) provided the mean signal and its standard deviation for the nasal cortex, and the adjacent soft-tissue ROI (“soft ROI”) provided the corresponding background values.

The primary endpoint was the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) at the cortical interface. CNR was defined at the subject level as the absolute difference between the mean signal in the bone ROI and the mean signal in the soft-tissue ROI, normalized by the combined noise level in these two regions. This metric reflects how strongly the cortex stands out from the adjacent soft tissue once the local noise is taken into account.

Two secondary endpoints were used. The first was the SNR of the cortical ROI (SNR_bone), which was obtained by dividing the mean cortical intensity by the standard deviation within the bone ROI and indicates how stable the cortical signal is relative to its own variability. The second was a background-referenced SNR (SNR_bg-ref), calculated by dividing the mean cortical intensity by the standard deviation measured in the soft-tissue ROI, and reflects the strength of the cortical signal relative to noise in the neighboring soft tissue.

For each of these metrics (CNR, SNR_bone and SNR_bg-ref), PAD and LGB were compared using two-tailed paired t-tests with a significance level of 0.05. For reporting, we present the mean ± standard deviation for each medium, the paired difference between PAD and LGB with a 95% confidence interval, and the corresponding t statistic, degrees of freedom and p-value.

3. Results

3.1. Image Set

Thirty paired PAD/LGB image sets from 30 noses were included in the analysis. All examinations were performed with the same preset (depth 40 mm, 10 MHz, dynamic range 75 dB, gain 76). PAD and LGB ROIs were placed at almost identical depths; the mean depth difference between the two media was 0.21 ± 0.10 mm.

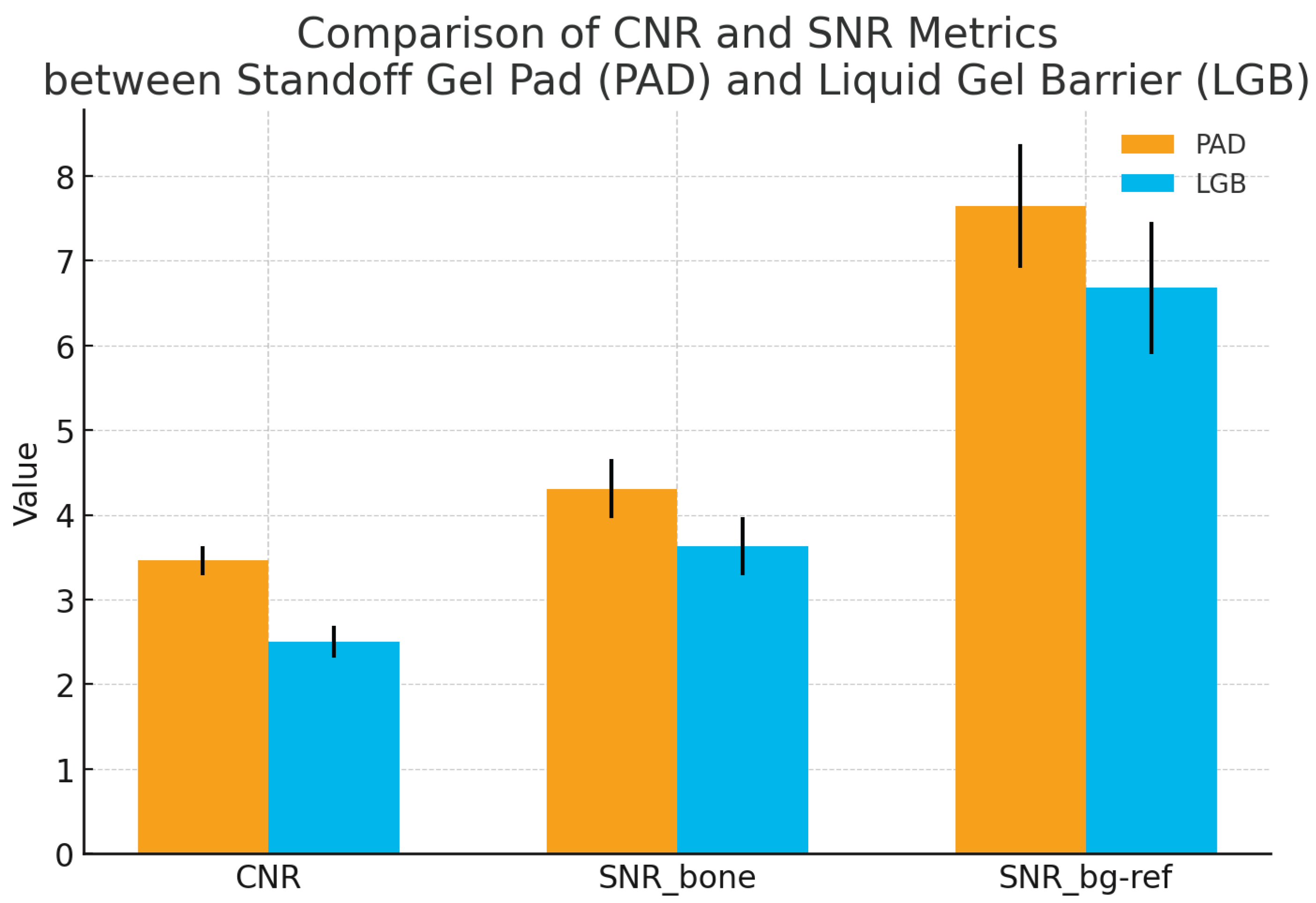

3.2. Primary Endpoint: CNR at the Cortical Interface

At the nasal cortical interface, CNR was higher with the standoff gel pad than with the liquid gel barrier. The mean CNR was 3.46 ± 0.17 for PAD and 2.50 ± 0.19 for LGB. The mean paired difference (PAD − LGB) was 0.96 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.88 to 1.04. The paired t-test gave t(29) = 23.42, p < 0.0001. Under identical imaging settings, the cortical interface was therefore more clearly separated in contrast from the adjacent soft tissue when PAD was used.

3.3. Secondary Endpoints: SNR

The cortical ROI also showed higher SNR with PAD. SNR_bone was 4.31 ± 0.35 with PAD and 3.63 ± 0.34 with LGB, giving a mean paired difference of 0.68 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.83; t(29) = 9.05, p < 0.0001).

When the standard deviation in the adjacent soft-tissue ROI was used as the noise reference (SNR_bg-ref), the same trend was seen. SNR_bg-ref was 7.64 ± 0.73 with PAD and 6.68 ± 0.78 with LGB. The mean paired difference was 0.96 (95% CI 0.59 to 1.33; t(29) = 5.26, p = 0.000012). These findings indicate that, in addition to higher contrast, the cortical signal was less affected by background noise when the standoff gel pad was used as the coupling medium (

Figure 4).

Paired quantitative results for 30 nasal bone fractures imaged with a semi-solid standoff gel pad (PAD) and a liquid gel barrier (LGB) under identical ultrasound presets. For each subject, contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) at the nasal cortical interface and two signal-to-noise ratios (SNR_bone and SNR_bg-ref) were calculated from matched cortical and adjacent soft-tissue ROIs. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation, and individual subjects are shown as paired points connected by thin lines. CNR was higher with PAD than with LGB (3.46 ± 0.17 vs. 2.50 ± 0.19; p < 0.0001), indicating clearer separation of the cortex from adjacent soft tissue. The cortical SNR (SNR_bone) was also increased with PAD (4.31 ± 0.35 vs. 3.63 ± 0.34; p < 0.0001), and the background-referenced SNR (SNR_bg-ref) showed the same pattern (7.64 ± 0.73 vs. 6.68 ± 0.78; p = 0.000012). Together, these results show that the standoff gel pad provides a more stable and higher-contrast depiction of the nasal cortex than the liquid gel barrier in intraoperative nasal bone sonography.

4. Discussion

In this within-subject crossover study, the standoff gel pad (PAD) consistently produced higher CNR and SNR at the nasal cortical interface than the liquid gel barrier (LGB). This is in line with the way the images look in practice: when PAD is used, the cortical line and subtle step-offs tend to stand out more clearly from the surrounding soft tissue, and the near-field appears cleaner. High-frequency ultrasonography has already been shown to be useful for diagnosing and managing nasal bone fractures, but its performance over the nasal dorsum depends heavily on the coupling medium and on how well thin cortical structures can be distinguished from adjacent soft tissue [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Water-bath or immersion techniques can widen the field of view, but they are vulnerable to bubbles, meniscus changes and motion, and these factors often reduce near-field sharpness even when overall penetration is adequate [

6].

Studies comparing acoustic media have reported that gel-based couplants provide better impedance matching and lower attenuation than water or oils, particularly for superficial targets [

7,

8]. Clinical and technical papers have also shown that gel standoff pads can improve near-field performance, for example by enhancing Doppler signal detection or stabilizing shear-wave elastography of superficial lesions [

9,

10]. Our CNR and SNR findings fit well with these earlier observations. With PAD, the mean intensity difference between bone and adjacent soft tissue is larger relative to the combined noise, and the cortical signal itself is more stable relative to its own variability and to the variability in the neighboring soft tissue. In simple terms, the cortex is more clearly separated from background fluctuations when a pad is used than when a liquid layer is retained by a barrier.

A plausible explanation is that the semi-solid pad provides a more stable and uniform near field. The pad conforms to the curved nasal dorsum and maintains a relatively constant, air-free path between the probe and the cortex, which reduces small reverberations and clutter close to the transducer. This should make the transition from soft tissue to bone sharper and more abrupt. By contrast, the LGB relies on a liquid layer confined by a plastic container and sponge liner, so any residual bubbles, local variations in gel thickness, or irregularities at the gel–air interface can introduce additional low-level echoes. These echoes can broaden the apparent transition between bone and soft tissue and lower local CNR, even if the overall brightness of the image looks acceptable.

The metrics we used are simple ROI-based intensity statistics, but similar approaches—using mean and variance of pixel values and grayscale histograms—have been used to describe B-mode echotexture and contrast differences between normal and diseased tissue in other organs [

12,

13]. More recent work on ultrasound detectability also emphasizes that the visibility of a structure depends not only on how bright it is but also on how its distribution of intensities compares to that of the background, which is the rationale behind CNR and more advanced generalized CNR measures [

15,

16]. In that context, higher CNR and SNR under the PAD condition mean that the nasal cortex is more strongly separated from background noise and clutter, which matches what clinicians perceive at the console as “sharper edges” and “cleaner definition” of the fracture line.

This study has several limitations. It was conducted at a single center with a single ultrasound platform (ZONARE L14-5w) and one fixed preset, and all scans were obtained by one operator and analyzed by one reader. This design reduces variability but also limits generalizability. ROI placement followed explicit rules and used matched depth and size between PAD and LGB, but a fully automatic method would further reduce potential bias. In addition, we did not assess downstream clinical outcomes such as procedure time, need for repeat manipulation or additional imaging. Even with these limitations, the consistent CNR and SNR advantages observed with PAD, together with a coherent physical explanation and agreement with previous work on gel-based couplants and standoff pads, support the conclusion that the standoff gel pad is a more suitable coupling medium than the liquid gel barrier for high-frequency, intraoperative nasal bone fracture sonography. Further studies with other scanners, presets and fracture patterns, and possibly with more advanced contrast and detectability metrics, would be useful to confirm and extend these findings.

5. Conclusions

A semi-solid standoff gel pad not only produced higher near-field contrast than a liquid gel barrier but was also straightforward to apply, easy to handle during maneuvers, and readily available as an off-the-shelf consumable; taken together, these attributes make it the clinically more useful medium for intraoperative nasal bone sonography. This study provides quantitative evidence supporting routine use of a gel pad to optimize real-time ultrasound guidance during closed reduction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.K. and K.A.L.; methodology, K.A.L.; software, K.A.L.; validation, K.A.L.; formal analysis, K.A.L.; investigation, D.G.K. and K.A.L.; resources, D.G.K. and K.A.L.; data curation, K.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.K. and K.A.L.; writing—review and editing, D.G.K. and K.A.L.; visualization, D.G.K. and K.A.L.; supervision, K.A.L.; project administration, K.A.L.; funding acquisition, K.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the 2023 Inje University research grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital (IRB No. 2023-10-022-002, approval period: December 2023 to February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The sharing of data is carried out in accordance with the consent provided by participants on the use of confidential data.

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank Seok Hyun Choo for critical reading of our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PAD |

Standoff gel pad |

| LGB |

Liquid gel barrier |

References

- Thiede, O.; Krömer, J.; Rudack, C.; Stoll, W.; Osada, N.; Schmäl, F. Comparison of Ultrasonography and Conventional Radiography in the Diagnosis of Nasal Fractures. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2005, 131, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.S.; Cha, J.G.; Paik, S.H.; Park, S.J.; Park, J.S.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, H.K. S.; Cha, J.G.; Paik, S.H.; et al. High-Resolution Sonography for Nasal Fracture in Children. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007, 188, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Yoo, H.; Yoon, K.R. Usefulness of Ultrasonography in the Treatment of Nasal Bone Fractures. J. Trauma 2009, 67, 1306–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.; Cha, J.G.; Hong, H.S.; Lee, J.S.; Park, S.J.; Paik, S.H; Lee, H.K. H. Comparison of High-Resolution Ultrasonography and Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis of Nasal Fractures. J. Ultrasound Med. 2009, 28, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astaraki, P.; Kabir, M.M.; Woznitza, N. Diagnosis of Acute Nasal Fractures Using Ultrasound and CT Scan: A Comparative Study. Clin. Imaging 2023, 82, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shigemura, Y.; Ueda, K.; Akamatsu, J.; Sugita, N.; Nuri, T.; Otsuki, Y.; Ueda, K.; Akamatsu, J. Ultrasonographic Images of Nasal Bone Fractures with Water Used as the Coupling Medium. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2017, 5, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmaseda, M.T., Jr.; Fatehi, M.T.; Koozekanani, S.H.; Lee, A.L. Ultrasound Therapy: A Comparative Study of Different Coupling Media. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1986, 67, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poltawski, L.; Watson, T. Relative Transmissivity of Ultrasound Coupling Agents Commonly Used by Therapists in the UK. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2007, 33, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvino, A.; Sandomenico, F.; Corvino, F.; Campanino, M.R.; Verde, F.; Giurazza, F.; Tafuri, D.; Catalano, O. Utility of a Gel Stand-Off Pad in the Detection of Doppler Signal on Focal Nodular Lesions of the Skin. J. Ultrasound 2020, 23, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; He, S.; Zhong, Y.; Zou, H.; Cai, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. The Effect of Gel Pads on the Measurement of Superficial Breast Lesions by Shear Wave Elastography. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2269941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V; Longair, M. ; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B; et al. ; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Kim, K.A.; Park, C.M.; Park, S.W.; Kim, B.H.; Cha, S.H. Usefulness of Standard Deviation on the Histogram of Ultrasound as a Quantitative Value for Hepatic Parenchymal Echo Texture. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006, 32, 1817–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikuta, E.; Koshiyama, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Banba, A.; Yanagisawa, N.; Nakagawa, M.; Ono, A.; Seki, K.; Kambe, H.; Godo, T.; et al. A Histogram Analysis of the Pixel Grayscale (Luminous Intensity) of B-Mode Ultrasound Images of the Subcutaneous Layer Predicts the Grade of Leg Edema in Pregnant Women. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Molares, A.; Rindal, O.M.H.; D’Hooge, J.; Masoy, S.-E.; Austeng, A.; Lediju Bell, M.A.; Torp, H. The Generalized Contrast-to-Noise Ratio: A Formal Definition for Lesion Detectability. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2020, 67, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, D.; Kim, G.B.; Bottenus, N.; Dahl, J.J. Ultrasound Lesion Detectability as a Distance Between Probability Measures. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2022, 69, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).