Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

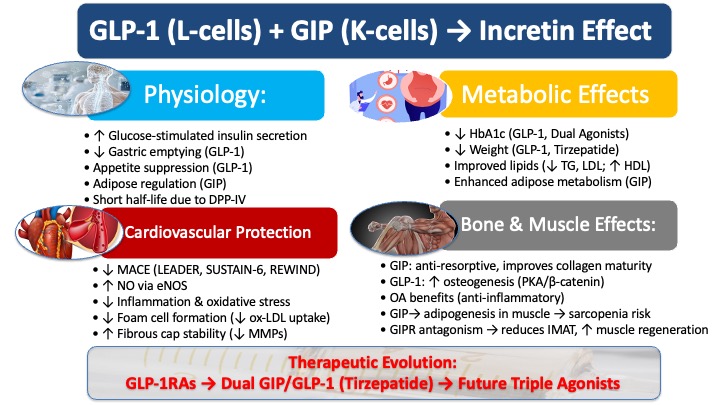

1.1. The Evolving Story of Incretins

1.2. Fundamental Physiology of the Incretin System

2. Physiology of GIP and GLP-1

2.1. Secretion and Metabolism

2.2. Receptor Distribution

2.3. Core Biological Actions

2.3.1. Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis

2.3.2. Gastrointestinal and Appetite Regulation

3. Pathophysiological Role in Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity

3.1. The Diminished Incretin Effect in T2DM: The "GIP Resistance" Phenomenon

3.2. Impact on Adipose Tissue and Lipid Metabolism

4. Cardiovascular Implications and Anti-Atherosclerotic Effects

4.1. Clinical Evidence from Cardiovascular Outcome Trials (CVOTs)

4.2. Indirect Cardioprotective Mechanisms: Modulating Systemic Risk Factors

4.3. Direct Anti-Atherosclerotic Mechanisms

4.3.1. Preserving Endothelial Function

4.3.2. Modulating Macrophage Activity and Plaque Inflammation

4.3.3. Stabilizing Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs)

4.4. Dual Agonists Effect

5. The Therapeutic Landscape: From GLP-1RAs to Dual and Triple Agonists

5.1. The Established Role of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

5.2. The Re-Emergence of GIP: Synergies in Dual GIP/GLP-1 Receptor Agonism

6. Clinical Evidence for GLP-1 RAs in Non-Diabetic Patients (Secondary Prevention)

6.1. The SELECT Trial: The Paradigm Shift

6.2. Subgroup Analysis: Efficacy in Highest-Risk Cohorts

6.3. Impact on Secondary CV Outcomes and Mortality

6.4. Awaiting Definitive Evidence: The SURMOUNT-MMO Trial

7. GLP-1 and GIP Influence on Bone Health and Remodeling

7.1. Bone Resorption and Formation

7.2. Bone Material Properties

7.3. Fracture Risk and Musculoskeletal Disorders

7.4. Effect of GIP on Sarcopenia

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| ACAT-1 | Acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase-1 |

| ApoE−/− | Apolipoprotein E knockout mouse |

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease |

| ARR | Absolute risk reduction |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BMSC | Bone marrow stromal cell |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CVOT | Cardiovascular outcome trial |

| DPP-IV | Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GIP | Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| GIPR | Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GLP-1RA(s) | GLP-1 receptor agonist(s) |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| IRA(s) | Incretin receptor agonist(s) |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MACE | Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| MMP(s) | Matrix metalloproteinase(s) |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| ox-LDL | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| VLDL | Very low-density lipoprotein |

| VSMC(s) | Vascular smooth muscle cell(s) |

References

- Nauck, M. A.; Quast, D. R.; Wefers, J.; Pfeiffer, A. F. H. The evolving story of incretins (GIP and GLP-1) in metabolic and cardiovascular disease: A pathophysiological update. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021, 23 Suppl 3, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Li, G.; Liu, P.; Ding, P.; Gao, Y. GLP-1 and GIP: Magic bullet for musculoskeletal diseases? J Adv Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M. A.; Heimesaat, M. M.; Orskov, C.; Holst, J. J.; Ebert, R.; Creutzfeldt, W. Preserved incretin activity of glucagon-like peptide 1 [7-36 amide] but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 1993, 91, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M. A.; Kleine, N.; Orskov, C.; Holst, J. J.; Willms, B.; Creutzfeldt, W. Normalization of fasting hyperglycaemia by exogenous glucagon-like peptide 1 (7-36 amide) in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetologia 1993, 36, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, A.; Raben, A.; Astrup, A.; Holst, J. J. Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest 1998, 101, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastin, M.; Andreelli, F. Dual GIP-GLP1-Receptor Agonists In The Treatment Of Type 2 Diabetes: A Short Review On Emerging Data And Therapeutic Potential. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2019, 12, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, W. T.; Frias, J. P.; Jastreboff, A. M.; le Roux, C. W.; Sattar, N.; Aizenberg, D.; Mao, H.; Zhang, S.; Ahmad, N. N.; Bunck, M. C.; Benabbad, I.; Zhang, X. M.; investigators, S.-. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity in people with type 2 diabetes (SURMOUNT-2): a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tall Bull, S.; Nuffer, W.; Trujillo, J. M. Tirzepatide: A novel, first-in-class, dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist. J Diabetes Complications 2022, 36, 108332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seino, Y.; Maekawa, R.; Ogata, H.; Hayashi, Y. Carbohydrate-induced secretion of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1. J Diabetes Investig 2016, 7 (Suppl 1), 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. K. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1431292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, A. M.; Polak, J. M.; Capella, C.; Solcia, E.; Pearse, A. G. Electronimmunocytochemical evidence for the K cell localization of gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) in man. Histochemistry 1978, 56, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, R.; Polak, J. M.; Pearse, A. G.; Solcia, E.; Grimelius, L.; Capella, C. Identification of the intestinal cell storing gastric inhibitory peptide. Histochemistry 1975, 43, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorsal, T.; Rhee, N. A.; Pedersen, J.; Wahlgren, C. D.; Mortensen, B.; Jepsen, S. L.; Jelsing, J.; Dalboge, L. S.; Vilmann, P.; Hassan, H.; Hendel, J. W.; Poulsen, S. S.; Holst, J. J.; Vilsboll, T.; Knop, F. K. Enteroendocrine K and L cells in healthy and type 2 diabetic individuals. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, A. E.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F. M. Distribution and Stimulus Secretion Coupling of Enteroendocrine Cells along the Intestinal Tract. Compr Physiol 2018, 8, 1603–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, B.; Ahn, J. M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogs: recent advances, new possibilities, and therapeutic implications. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 1020–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Qi, X.; Fan, G.; Zhou, L.; Peng, Z.; Yang, J. Anti-atherosclerotic effect of incretin receptor agonists. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1463547. [Google Scholar]

- Ahren, B.; Yamada, Y.; Seino, Y. The Incretin Effect in Female Mice With Double Deletion of GLP-1 and GIP Receptors. J Endocr Soc 2020, 4, bvz036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pederson, R. A.; Brown, J. C. Interaction of gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucose, and arginine on insulin and glucagon secretion from the perfused rat pancreas. Endocrinology 1978, 103, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pederson, R. A.; Brown, J. C. The insulinotropic action of gastric inhibitory polypeptide in the perfused isolated rat pancreas. Endocrinology 1976, 99, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.; Vedtofte, L.; Holst, J. J.; Vilsboll, T.; Knop, F. K. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide: a bifunctional glucose-dependent regulator of glucagon and insulin secretion in humans. Diabetes 2011, 60, 3103–3109. [Google Scholar]

- Gasbjerg, L. S.; Bergmann, N. C.; Stensen, S.; Christensen, M. B.; Rosenkilde, M. M.; Holst, J. J.; Nauck, M.; Knop, F. K. Evaluation of the incretin effect in humans using GIP and GLP-1 receptor antagonists. Peptides 2020, 125, 170183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettergren, A.; Schjoldager, B.; Mortensen, P. E.; Myhre, J.; Christiansen, J.; Holst, J. J. Truncated GLP-1 (proglucagon 78-107-amide) inhibits gastric and pancreatic functions in man. Dig Dis Sci 1993, 38, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M. A.; Niedereichholz, U.; Ettler, R.; Holst, J. J.; Orskov, C.; Ritzel, R.; Schmiegel, W. H. Glucagon-like peptide 1 inhibition of gastric emptying outweighs its insulinotropic effects in healthy humans. Am J Physiol 1997, 273, E981–E988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J. J.; Goetze, O.; Anstipp, J.; Hagemann, D.; Holst, J. J.; Schmidt, W. E.; Gallwitz, B.; Nauck, M. A. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide does not inhibit gastric emptying in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2004, 286, E621–E625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, N. C.; Lund, A.; Gasbjerg, L. S.; Meessen, E. C. E.; Andersen, M. M.; Bergmann, S.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J. J.; Jessen, L.; Christensen, M. B.; Vilsboll, T.; Knop, F. K. Effects of combined GIP and GLP-1 infusion on energy intake, appetite and energy expenditure in overweight/obese individuals: a randomised, crossover study. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M.; Stockmann, F.; Ebert, R.; Creutzfeldt, W. Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 1986, 29, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarup, T.; Saurbrey, N.; Moody, A. J.; Kuhl, C.; Madsbad, S. Effect of porcine gastric inhibitory polypeptide on beta-cell function in type I and type II diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 1987, 36, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentis, N.; Vardarli, I.; Kothe, L. D.; Holst, J. J.; Deacon, C. F.; Theodorakis, M.; Meier, J. J.; Nauck, M. A. GIP does not potentiate the antidiabetic effects of GLP-1 in hyperglycemic patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2011, 60, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getty-Kaushik, L.; Song, D. H.; Boylan, M. O.; Corkey, B. E.; Wolfe, M. M. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide modulates adipocyte lipolysis and reesterification. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006, 14, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, R. H.; Fujimoto, W. Y.; Brunzell, J. D. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide enhanced lipoprotein lipase activity in cultured preadipocytes. Diabetes 1979, 28, 1141–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D. H.; Getty-Kaushik, L.; Tseng, E.; Simon, J.; Corkey, B. E.; Wolfe, M. M. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide enhances adipocyte development and glucose uptake in part through Akt activation. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 1796–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. J.; Nian, C.; McIntosh, C. H. Activation of lipoprotein lipase by glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in adipocytes. A role for a protein kinase B, LKB1, and AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 8557–8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlqvist, E.; Osmark, P.; Kuulasmaa, T.; Pilgaard, K.; Omar, B.; Brons, C.; Kotova, O.; Zetterqvist, A. V.; Stancakova, A.; Jonsson, A.; Hansson, O.; Kuusisto, J.; Kieffer, T. J.; Tuomi, T.; Isomaa, B.; Madsbad, S.; Gomez, M. F.; Poulsen, P.; Laakso, M.; Degerman, E.; Pihlajamaki, J.; Wierup, N.; Vaag, A.; Groop, L.; Lyssenko, V. Link between GIP and osteopontin in adipose tissue and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2013, 62, 2088–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, A. F. H.; Keyhani-Nejad, F. High Glycemic Index Metabolic Damage - a Pivotal Role of GIP and GLP-1. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2018, 29, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Chai, S.; Li, L.; Yu, K.; Yang, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, L.; Zhan, S. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on weight loss in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Diabetes Res 2015, 2015, 157201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S. P.; Daniels, G. H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J. F.; Nauck, M. A.; Nissen, S. E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N. R.; Ravn, L. S.; Steinberg, W. M.; Stockner, M.; Zinman, B.; Bergenstal, R. M.; Buse, J. B.; Committee, L. S.; Investigators, L. T. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S. P.; Bain, S. C.; Consoli, A.; Eliaschewitz, F. G.; Jodar, E.; Leiter, L. A.; Lingvay, I.; Rosenstock, J.; Seufert, J.; Warren, M. L.; Woo, V.; Hansen, O.; Holst, A. G.; Pettersson, J.; Vilsboll, T.; Investigators, S.-. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, H. C.; Colhoun, H. M.; Dagenais, G. R.; Diaz, R.; Lakshmanan, M.; Pais, P.; Probstfield, J.; Riesmeyer, J. S.; Riddle, M. C.; Ryden, L.; Xavier, D.; Atisso, C. M.; Dyal, L.; Hall, S.; Rao-Melacini, P.; Wong, G.; Avezum, A.; Basile, J.; Chung, N.; Conget, I.; Cushman, W. C.; Franek, E.; Hancu, N.; Hanefeld, M.; Holt, S.; Jansky, P.; Keltai, M.; Lanas, F.; Leiter, L. A.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Cardona Munoz, E. G.; Pirags, V.; Pogosova, N.; Raubenheimer, P. J.; Shaw, J. E.; Sheu, W. H.; Temelkova-Kurktschiev, T.; Investigators, R. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M. A.; D'Alessio, D. A. Tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor co-agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes with unmatched effectiveness regrading glycaemic control and body weight reduction. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022, 21, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, J. J.; Gethmann, A.; Gotze, O.; Gallwitz, B.; Holst, J. J.; Schmidt, W. E.; Nauck, M. A. Glucagon-like peptide 1 abolishes the postprandial rise in triglyceride concentrations and lowers levels of non-esterified fatty acids in humans. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, D.; Onishi, Y.; Norwood, P.; Huh, R.; Bray, R.; Patel, H.; Rodriguez, A. Effect of Subcutaneous Tirzepatide vs Placebo Added to Titrated Insulin Glargine on Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: The SURPASS-5 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Wu, S.; Guo, S.; Yu, K.; Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, X.; Ji, L.; Zhan, S. Impact of GLP-1 receptor agonists on blood pressure, heart rate and hypertension among patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015, 110, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, C.; Mistry, M.; Roman, R. J. Renal effects of glucagon-like peptide in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2002, 434, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skov, J.; Dejgaard, A.; Frokiaer, J.; Holst, J. J.; Jonassen, T.; Rittig, S.; Christiansen, J. S. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1): effect on kidney hemodynamics and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, E664–E671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E. P.; Moller, S.; Hviid, A. V.; Veedfald, S.; Holst, J. J.; Pedersen, J.; Orskov, C.; Sorensen, C. M. GLP-1-induced renal vasodilation in rodents depends exclusively on the known GLP-1 receptor and is lost in prehypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2020, 318, F1409–F1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmstadter, J.; Frenis, K.; Filippou, K.; Grill, A.; Dib, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Pawelke, F.; Kus, K.; Kroller-Schon, S.; Oelze, M.; Chlopicki, S.; Schuppan, D.; Wenzel, P.; Ruf, W.; Drucker, D. J.; Munzel, T.; Daiber, A.; Steven, S. Endothelial GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1) Receptor Mediates Cardiovascular Protection by Liraglutide In Mice With Experimental Arterial Hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020, 40, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Wei, R.; Yang, K.; Lang, S.; Gu, L.; Liu, J.; Hong, T.; Yang, J. Liraglutide ameliorates palmitate-induced oxidative injury in islet microvascular endothelial cells through GLP-1 receptor/PKA and GTPCH1/eNOS signaling pathways. Peptides 2020, 124, 170212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Bollag, R. J.; Dransfield, D. T.; Gasalla-Herraiz, J.; Ding, K. H.; Min, L.; Isales, C. M. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide signaling pathways in endothelial cells. Peptides 2000, 21, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Mehta, J. L.; Chen, M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide inhibits endothelin-1 in endothelial cell by repressing nuclear factor-kappa B activation. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2013, 27, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari, T.; Liu, H.; Welungoda, I.; Hu, Y.; Widdop, R. E.; Knudsen, L. B.; Simpson, R. W.; Dear, A. E. A GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide inhibits endothelial cell dysfunction and vascular adhesion molecule expression in an ApoE-/- mouse model. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2011, 8, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. T.; Tang, H. Q.; Su, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H. Q. Glucagon-like peptide-1 attenuates endothelial barrier injury in diabetes via cAMP/PKA mediated down-regulation of MLC phosphorylation. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 113, 108667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; She, M.; Xu, M.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Zheng, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Xu, X.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, X.; Li, H. GLP-1 treatment protects endothelial cells from oxidative stress-induced autophagy and endothelial dysfunction. Int J Biol Sci 2018, 14, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Sun, H. L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, D. H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) protects vascular endothelial cells against advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-induced apoptosis. Med Sci Monit 2012, 18, BR286–BR291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, Y.; Sato, K.; Watanabe, T.; Nohtomi, K.; Terasaki, M.; Nagashima, M.; Hirano, T. A glucagon-like peptide-1 analog liraglutide suppresses macrophage foam cell formation and atherosclerosis. Peptides 2014, 54, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Dai, D.; Wang, X.; Ding, Z.; Li, C.; Mehta, J. L. GLP-1 agonists inhibit ox-LDL uptake in macrophages by activating protein kinase A. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2014, 64, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, M.; Watanabe, T.; Terasaki, M.; Tomoyasu, M.; Nohtomi, K.; Kim-Kaneyama, J.; Miyazaki, A.; Hirano, T. Native incretins prevent the development of atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 2649–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasaki, M.; Yashima, H.; Mori, Y.; Saito, T.; Shiraga, Y.; Kawakami, R.; Ohara, M.; Fukui, T.; Hirano, T.; Yamada, Y.; Seino, Y.; Yamagishi, S. I. Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Suppresses Foam Cell Formation of Macrophages through Inhibition of the Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 5-CD36 Pathway. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Mei, A.; Liu, X.; Braunstein, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, B.; Duan, L.; Rao, X.; Rajagopalan, S.; Dong, L.; Zhong, J. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Regulates Macrophage Migration in Monosodium Urate-Induced Peritoneal Inflammation. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 772446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinue, A.; Navarro, J.; Herrero-Cervera, A.; Garcia-Cubas, M.; Andres-Blasco, I.; Martinez-Hervas, S.; Real, J. T.; Ascaso, J. F.; Gonzalez-Navarro, H. The GLP-1 analogue lixisenatide decreases atherosclerosis in insulin-resistant mice by modulating macrophage phenotype. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruen, R.; Curley, S.; Kajani, S.; Crean, D.; O'Reilly, M. E.; Lucitt, M. B.; Godson, C. G.; McGillicuddy, F. C.; Belton, O. Liraglutide dictates macrophage phenotype in apolipoprotein E null mice during early atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2017, 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Meng, P.; Liu, X. Liraglutide attenuates high glucose-induced abnormal cell migration, proliferation, and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells by activating the GLP-1 receptor, and inhibiting ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, G.; Morales, P. E.; Garcia-Miguel, M.; Norambuena-Soto, I.; Cartes-Saavedra, B.; Vidal-Pena, G.; Moncada-Ruff, D.; Sanhueza-Olivares, F.; San Martin, A.; Chiong, M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell dedifferentiation through mitochondrial dynamics regulation. Biochem Pharmacol 2016, 104, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgmaier, M.; Liberman, A.; Mollmann, J.; Kahles, F.; Reith, S.; Lebherz, C.; Marx, N.; Lehrke, M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and its split products GLP-1(9-37) and GLP-1(28-37) stabilize atherosclerotic lesions in apoe(-)/(-) mice. Atherosclerosis 2013, 231, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Lei, Y.; Inoue, A.; Piao, L.; Hu, L.; Jiang, H.; Sasaki, T.; Wu, H.; Xu, W.; Yu, C.; Zhao, G.; Ogasawara, S.; Okumura, K.; Kuzuya, M.; Cheng, X. W. Exenatide mitigated diet-induced vascular aging and atherosclerotic plaque growth in ApoE-deficient mice under chronic stress. Atherosclerosis 2017, 264, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D. M.; Park, K. Y.; Hwang, W. M.; Kim, J. Y.; Kim, B. J. Difference in protective effects of GIP and GLP-1 on endothelial cells according to cyclic adenosine monophosphate response. Exp Ther Med 2017, 13, 2558–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H. M. GLP-1 Agonists in Cardiovascular Diseases: Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Emerging Therapies. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. K.; La Lee, Y.; Jung, C. H. The Cardiovascular Effect of Tirzepatide: A Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 and Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Dual Agonist. J Lipid Atheroscler 2023, 12, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J. J. On the physiology of GIP and GLP-1. Horm Metab Res 2004, 36, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knop, F. K.; Vilsboll, T.; Larsen, S.; Hojberg, P. V.; Volund, A.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J. J.; Krarup, T. Increased postprandial responses of GLP-1 and GIP in patients with chronic pancreatitis and steatorrhea following pancreatic enzyme substitution. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007, 292, E324–E330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D. R.; Monnier, L.; Hanefeld, M. A review of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and their effects on lowering postprandial plasma glucose and cardiovascular outcomes in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017, 19, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J. P.; Nauck, M. A.; Van, J.; Kutner, M. E.; Cui, X.; Benson, C.; Urva, S.; Gimeno, R. E.; Milicevic, Z.; Robins, D.; Haupt, A. Efficacy and safety of LY3298176, a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, placebo-controlled and active comparator-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 2180–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. K.; Nikooienejad, A.; Bray, R.; Cui, X.; Wilson, J.; Duffin, K.; Milicevic, Z.; Haupt, A.; Robins, D. A. Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Tirzepatide Improves Beta-cell Function and Insulin Sensitivity in Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021, 106, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Colhoun, H. M.; Dicker, D.; Hovingh, G. K.; Kahn, S. E.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Lingvay, I.; Plutzky, J.; Rasmussen, S.; Rathor, N.; Hoff, S. T.; Lincoff, A. M. Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People With Overweight or Obesity (SELECT): Outcomes by Sex. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 84, 1678–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odigwe, C.; Mulyala, R.; Malik, H.; Ruiz, B.; Riad, M.; Sayiadeh, M. A.; Honganur, S.; Parks, A.; Rahman, M. U.; Lakkis, N. Emerging role of GLP-1 agonists in cardio-metabolic therapy - Focus on Semaglutide. Am Heart J Plus 2025, 52, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkistani, Y. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a review from a cardiovascular perspective. Front Cardiovasc Med 2025, 12, 1535134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinpour, A.; Sood, A.; Kamalpour, J.; Zandi, E.; Pakmehr, S.; Hosseinpour, H.; Sood, A.; Agrawal, A.; Gupta, R. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients With and Without Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized-Controlled Trials. Clin Cardiol 2024, 47, e24314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, R.; Barve, N. A.; Kelkar, R.; Kharel, S.; Khanapurkar, S.; Yadav, R. Comparison of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists vs. placebo on any cardiovascular events in overweight or obese non-diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11, 1453297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C. S. P.; Rodriguez, A.; Aminian, A.; Ferrannini, E.; Heerspink, H. J. L.; Jastreboff, A. M.; Laffin, L. J.; Pandey, A.; Ray, K. K.; Ridker, P. M.; Sanyal, A. J.; Yki-Jarvinen, H.; Mason, D.; Strzelecki, M.; Bartee, A. K.; Cui, C.; Hurt, K.; Linetzky, B.; Bunck, M. C.; Nissen, S. E. Tirzepatide for reduction of morbidity and mortality in adults with obesity: rationale and design of the SURMOUNT-MMO trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2025, 33, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helsted, M. M.; Gasbjerg, L. S.; Lanng, A. R.; Bergmann, N. C.; Stensen, S.; Hartmann, B.; Christensen, M. B.; Holst, J. J.; Vilsboll, T.; Rosenkilde, M. M.; Knop, F. K. The role of endogenous GIP and GLP-1 in postprandial bone homeostasis. Bone 2020, 140, 115553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M. S.; Soe, K.; Christensen, L. L.; Fernandez-Guerra, P.; Hansen, N. W.; Wyatt, R. A.; Martin, C.; Hardy, R. S.; Andersen, T. L.; Olesen, J. B.; Hartmann, B.; Rosenkilde, M. M.; Kassem, M.; Rauch, A.; Gorvin, C. M.; Frost, M. GIP reduces osteoclast activity and improves osteoblast survival in primary human bone cells. Eur J Endocrinol 2023, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torekov, S. S.; Harslof, T.; Rejnmark, L.; Eiken, P.; Jensen, J. B.; Herman, A. P.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Holst, J. J.; Langdahl, B. L. A functional amino acid substitution in the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) gene is associated with lower bone mineral density and increased fracture risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99, E729–E733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, N.; Jia, M.; Bi, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Xue, X.; Hou, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Z.; He, G.; Luo, X. Activation of GLP-1 Receptor Promotes Bone Marrow Stromal Cell Osteogenic Differentiation through beta-Catenin. Stem Cell Reports 2016, 6, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Liu, H.; Lu, H. Glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1) receptor agonists: potential to reduce fracture risk in diabetic patients? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016, 81, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobron, B.; Couchot, M.; Irwin, N.; Legrand, E.; Bouvard, B.; Mabilleau, G. Development of a First-in-Class Unimolecular Dual GIP/GLP-2 Analogue, GL-0001, for the Treatment of Bone Fragility. J Bone Miner Res 2023, 38, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y. Y.; Cao, X.; Bai, N.; Lu, T. T.; Li, G. Q.; Li, N.; Wang, A. N.; Mao, X. M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and risk of bone fracture in patients with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2019, 35, e3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidayat, K.; Du, X.; Shi, B. M. Risk of fracture with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in real-world use: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Osteoporos Int 2019, 30, 1923–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, N. C.; Lund, A.; Gasbjerg, L. S.; Jorgensen, N. R.; Jessen, L.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J. J.; Christensen, M. B.; Vilsboll, T.; Knop, F. K. Separate and Combined Effects of GIP and GLP-1 Infusions on Bone Metabolism in Overweight Men Without Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 104, 2953–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A. S.; Batsis, J. A. Treating Sarcopenic Obesity in the Era of Incretin Therapies: Perspectives and Challenges. Diabetes 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.; Megyeri, S.; Nuffer, W.; Trujillo, J. M. The potential role of GLP-1 receptor agonists in osteoarthritis. Pharmacotherapy 2025, 45, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Fujita, H.; Seino, Y.; Hattori, S.; Hidaka, S.; Miyakawa, T.; Suzuki, A.; Waki, H.; Yabe, D.; Seino, Y.; Yamada, Y. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor antagonism suppresses intramuscular adipose tissue accumulation and ameliorates sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 2703–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C. After obesity drugs' success, companies rush to preserve skeletal muscle. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tissue/Organ | GLP-1 Receptor (GLP-1R) Presence & Details | GIP Receptor (GIPR) Presence & Details |

| Endocrine Pancreas | β-cells: +++ (Abundantly expressed) α-cells: -/+ (Present in a small proportion of α-cells) |

β-cells: +++ (Abundantly expressed) α-cells: ++ (Present) |

| Heart | + (Present in all four chambers, particularly the sinoatrial node) | + (Present in all four chambers) |

| Blood Vessels | + (Present, including in endothelial cells) | + (Present in endothelial cells) |

| Adipose Tissue | + (Present, primarily in vascular cells; debated on adipocytes) | ++ (Present, though unclear if on adipocytes or stromal-vascular cells) |

| Bone | -/+ (Absent in cultured osteoblasts but present in bone marrow stromal cells) | ++ (Present in osteoblasts and osteocytes) |

| Brain | ++ (Present in key areas for appetite regulation like the hypothalamus and brainstem) | + (Present in various regions including hippocampus and cortex) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).