1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, often resulting in recurrent events and reduced quality of life [

1]. Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is an established, evidence-based intervention that improves prognosis, reduces hospitalizations, and enhances quality of life in patients with coronary heart disease and other forms of CVD [

2,

3,

4]. Aerobic exercise is the cornerstone of CR because regular training improves cardiorespiratory fitness, functional capacity, and multiple cardiovascular risk factors [

2,

3]. In clinical practice, the treadmill and lower-limb ergometers are the most commonly used devices for supervised aerobic training because they are practical in indoor clinical settings, allow exercise regardless of weather, and provide reliable, reproducible workloads for cardiopulmonary testing and training [

5].

However, strictly, indoor exercise modalities do not replicate the sensory, environmental, and motivational elements associated with outdoor activity. Exercise performed in natural or outdoor settings has been linked to greater enjoyment, intrinsic motivation, and intentions to repeat activity compared with equivalent indoor exercise, although measured physiological benefits are modest and vary across studies [

6,

7]. Cycling is a widely used and sustainable form of aerobic activity in daily life and offers an ecologically valid mode for assessing and prescribing exercise [

8,

9]. For older adults and patients with CVD, however, outdoor cycling raises safety concerns, such as falls and traffic-related injuries, along with environmental unpredictability and challenges in individualizing exercise intensity. These factors limit its routine application in supervised CR programs [

10,

11].

To bridge this gap, several indoor technologies, such as immersive and non-immersive virtual reality (VR) exergaming systems, integrated smart-trainer platforms, and bicycle simulators, have been developed to reproduce outdoor exercise experiences while maintaining clinical safety and workload control [

7,

12]. These systems can increase patient engagement and appear feasible as adjuncts to CR, although physiological responses vary by device and population [

12,

13,

14]. Unlike earlier VR-based or stationary cycling systems, the Ulti-racer series—the outdoor-simulated interactive indoor cycling device assessed in this study—was designed to reproduce key sensory and mechanical aspects of outdoor cycling (visual flow, lateral sliding and tilting, and realistic posture dynamics) while allowing continuous electrocardiography (ECG) and breath-by-breath physiological monitoring, individualized workload control, and supervised safety measures.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the feasibility, safety, and the ability of this outdoor-simulated interactive indoor cycling device to elicit exercise intensities within established CR therapeutic ranges in patients with CVD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

In this single-center prospective study, we enrolled clinically stable patients with CVD who were referred to the CR program at OO University OO Hospital. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Anam Hospital (approval no.: No. 2023AN0287). Patients were recruited between September 2023 and December 2023, and a total of 20 patients were enrolled.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Participants were eligible for enrollment if they met all of the following criteria:

Age ≥ 18 years at enrollment.

Diagnosis of CVD, including acute coronary syndrome or stable ischemic heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting; valvular heart disease with valve replacement surgery; stable heart failure; or prior cardiac surgery.

Classified as low-to-moderate exercise risk for supervised exercise and exercise testing based on institutional assessment.

Ability to understand study procedures and provide written informed consent.

Physical ability to mount and pedal a cycle and perform symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Participants were excluded if any of the following applied:

Absolute contraindications to exercise testing or training per established exercise testing guidelines [

15].

Hemodynamically unstable conditions (e.g., acute infection or severe electrolyte imbalance) or uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 110 mmHg at rest that could not be safely controlled before testing).

Severe or uncontrolled arrhythmia, or the presence of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in whom device management could not ensure safety during supervised exercise.

Recent acute myocardial infarction (MI), unstable coronary syndrome, or major cardiac procedure within the acute post-event period (patients within the first 2 weeks after an acute MI were excluded).

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30% or New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV symptoms.

Severe cognitive impairment or psychiatric disorder that, in the investigator’s judgment, prevented informed consent or safe participation.

Significant musculoskeletal, neurologic, or other lower-extremity conditions that prevent safe cycling or valid CPET

Inability to ambulate or transfer safely for cycle mounting or dismounting without reasonable assistance

Other comorbid conditions expected to significantly limit life expectancy or interfere with participation, as judged by the investigator.

Demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

2.4. Study Protocol

Baseline assessments were performed before any exercise testing and included body mass index (BMI), skeletal muscle index (SMI), Korean Activity Scale/Index (KASI), EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D), handgrip strength, and a 6-minute walk test (6MWT). All participants first completed symptom-limited CPET on a treadmill using a modified Bruce protocol to ensure uniformity and reduce test-retest variability. During the test, breath-by-breath gas analysis was performed using a portable metabolic system (K5, COSMED Inc., Rome, Italy), and continuous ECG monitoring was performed using a wearable ECG patch device (HiCardi, MEZOO Co., Ltd., Wonju, Korea). Device-specific calibration (gas analyzer calibration and flow calibration) was performed before testing, and mask fitting was performed for each participant; the fit was checked, and any leaks were corrected until an adequate seal was confirmed. The primary purpose of the treadmill CPET was to determine each participant’s peak cardiopulmonary response, such as peak oxygen consumption (VO2) and peak metabolic equivalents (METs), which served as the individualized reference for subsequent comparisons.

After completing CPET and a supervised recovery period of 30–60 min, each participant was prepared for the cycling session using the outdoor-simulated interactive indoor cycling device (Ulti-racer P, Real Design Tech Co., Ltd., Seongnam, Korea). The 30-60 min rest interval was designed to minimize residual fatigue. A standardized seat and pedal fitting procedure was performed (saddle height adjusted to achieve approximately 5–10° knee flexion during the downstroke, pedal straps secured), and bicycle settings (tire/air pressure or trainer resistance) were adjusted to each participant’s anthropometry and comfort. Participants completed a brief familiarization period (typically <1 min) to confirm comfort, seating position, and pedal engagement. Participants then performed a 10-min exercise bout on the cycling device. Participants were instructed to hold the handlebar with both hands and pedal at a self-selected cadence and power level; duration was fixed at 10 min to evaluate steady-state cardiopulmonary responses under realistic self-paced conditions. The same physiological variables measured during CPET were recorded during the cycling session. The primary purpose of the cycling session was to quantify cardiopulmonary responses produced by the outdoor-simulated cycling device and compare them with the exercise intensity range recommended for CR (40–85% of treadmill-derived peak METs obtained from the treadmill-based CPET).

To ensure participant safety and enable rapid responses to unexpected events (e.g., falls, chest pain, syncope), a physician, nurse, and physical therapist were present and continuously monitored all tests. Test termination criteria followed established CPET and CR guidelines and were documented in the study protocol. All emergency equipment, including a defibrillator, was immediately available.

Furthermore, to evaluate age-related differences, subgroup analyses were conducted by dividing patients into younger (<60 years) and older (≥60 years) groups. The aim was to determine whether the outdoor-simulated indoor cycling device could deliver exercise intensities appropriate for CR in both subgroups.

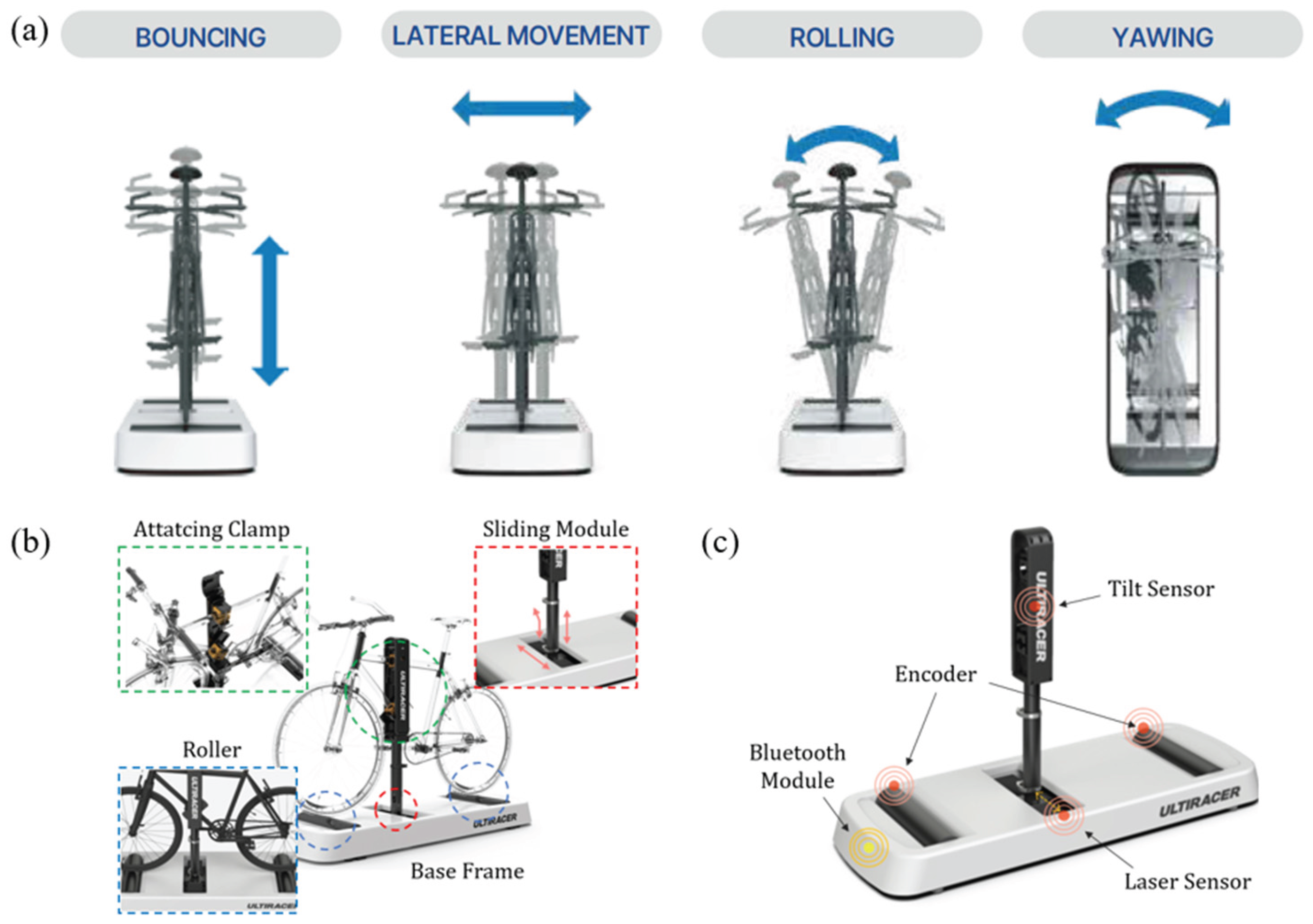

2.5. An Outdoor-Simulated Interactive Indoor Cycling Device

We employed a novel outdoor-simulated interactive indoor cycling device (Ulti-racer P). The system consists of four main components: a base frame, anterior and posterior rollers, a sliding module, and an adjustable mounting clamp that attaches securely to the bicycle frame. This patented frame-clamp mechanism stabilizes the bicycle on the platform while allowing the wheels to rotate freely on the rollers, thereby enabling safe and continuous indoor pedaling (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) [

16].

A distinctive feature of this platform is its ability to reproduce coronal-plane motion through both lateral sliding (±10 cm) and tilting (±1°). These dynamic capabilities mimic outdoor cycling balance demands while maintaining a controlled and safe indoor environment. Consequently, users can experience realistic cycling motion without the risk of falling, making the device suitable for frail older adults or patients with balance limitations, as well as healthy individuals. Importantly, the system can be operated without additional pedal sensors, ensuring versatility for research and clinical rehabilitation applications.

2.6. Outcome Measurements

2.6.1. Assessment of Cardiopulmonary Responses

The primary variables included peak VO

2, peak ventilatory threshold (VT), peak METs, peak heart rate (HR), resting HR, peak respiratory exchange ratio (RER), peak rate-pressure product (RPP), peak rating of perceived exertion (RPE), peak systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP), and total exercise duration. Peak VO

2 was defined as the highest 30-s averaged value during the test and was also expressed in METs (1 MET = 3.5 mL O

2·kg

−1·min

−1) to indicate exercise intensity. Peak HR was defined as the mean HR recorded during the last 30 s of exercise and was also expressed as a percentage of the age-predicted maximal HR using the formula: [HR peak / (220 − age)] × 100. RER was calculated as the ratio of V̇CO

2 to V̇O

2. We considered a peak RER ≥1.10 a conservative indicator of maximal metabolic effort. Because the mean RER during cycling was 1.0 in our sample, cycling results were interpreted as representing high submaximal to near-maximal effort and were complemented with peak RPE and VO

2 plateau assessments. RPE was obtained immediately at test termination using the Borg 6–20 scale. BP was measured at rest and at peak exercise using an automated sphygmomanometer. Relative cardiopulmonary workload was quantified as the ratio of cycling-to-treadmill peak responses for each parameter (VO

2, HR, METs), expressed as a percentage using the formula:

2.6.2. Assessment of Body Composition

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m

2). SMI was assessed using a multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analyzer (InBody, InBody Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). SMI was calculated as appendicular skeletal muscle mass divided by height squared (kg/m

2), a method validated as a reliable measure of muscle mass in clinical research [

17].

2.6.3. Assessment of Physical Activity Level

Physical activity level was evaluated using the KASI [

18], a validated questionnaire specifically developed to assess the daily activity status of patients with CVD. The KASI provides a numerical score that reflects an individual’s habitual activity and exercise tolerance.

2.6.4. Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life

Health-related quality of life was assessed using the EQ-5D [

19], which measures five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The validated Korean version was used, and the EQ-5D index score was calculated based on Korean population preference weights.

2.6.5. Assessment of Muscle Strength

Handgrip strength was measured using a digital hand dynamometer (JAMAR PLUS+ Digital Hand Dynamometer; Sammons Preston Rolyan, Bolingbrook, IL, USA). Participants were instructed to stand with the arm at the side and elbow extended, and then to exert maximal force for 3 s. Each hand was tested twice, with at least 1 min of rest between trials, and the highest value for each hand was recorded in kilograms for analysis [

20]. Handgrip strength provides a surrogate measure of overall muscular fitness and functional capacity in patients undergoing CR [

21].

2.6.6. Assessment of Exercise Capacity

Exercise capacity was assessed using the 6MWT, following standardized guidelines [

22,

23]. Participants were instructed to walk back and forth along a flat, straight, 30-m corridor for 6 min at their maximal self-selected pace. Standardized encouragement was given at regular intervals, and the total distance walked (m) during the 6-min period was recorded as the outcome measure.

2.6.7. Patient Satisfaction Assessment with Outdoor Simulated Indoor Cycling Device

At the end of the study period, participants completed a self-administered questionnaire assessing satisfaction with the outdoor-simulated indoor cycling device. Satisfaction was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied). Participants also indicated reasons for their ratings using predefined options and were given the opportunity to provide open-ended comments regarding specific advantages or areas for improvement.

2.7. Safety Monitoring

Continuous single-lead ECG monitoring was performed during the entire session using the Hicardi system, a wireless ECG recorder. The primary purpose was to detect potential arrhythmias and ensure patient safety during exercise. Specific arrhythmias of interest included ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, atrial fibrillation, and advanced atrioventricular block. In addition, the occurrence of premature atrial or ventricular contractions, as well as episodes of sinus tachycardia, was recorded and analyzed for clinical relevance.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables, including demographic characteristics (age, height, weight, BMI), SMI, KASI, EQ-5D, grip strength (best value), and 6-min walk distance (6MWD), were compared between age-stratified subgroups (<60 vs. ≥60 years). Normality for each variable within each subgroup was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. When both subgroups satisfied the assumption of normality (p ≥ 0.05), independent samples t-tests were performed; otherwise, Mann–Whitney U tests were applied. CPET parameters from both treadmill- and cycle-derived assessments were analyzed similarly. Subgroup comparisons (<60 vs. ≥60 years) for each modality followed the same procedure (Shapiro–Wilk test followed by either independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate). Within-group comparisons between treadmill- and cycle-derived CPET results were also performed. For this analysis, individual difference scores (treadmill—cycle) were calculated for each participant. Normality of these difference scores was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. When normally distributed, paired samples t-tests were used; otherwise, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or as median (interquartile range [IQR]) for non-normally distributed data.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Assessment of Participants

A total of 20 patients were included in the analysis, with a mean age of 56.1 ± 11.7 years. When stratified by age, the subgroup younger than 60 years (n = 11) had a mean age of 47.5 ± 7.5 years, whereas those aged 60 years or older (n = 9) had a mean age of 66.6 ± 5.2 years (p < 0.001). Patients in the younger subgroup were significantly taller (177.4 ± 8.2 cm vs. 170.6 ± 4.3 cm, p = 0.038) and heavier (81.3 ± 12.0 kg vs. 70.4 ± 8.5 kg, p = 0.035) those in the older subgroup. BMI and SMI did not differ significantly between groups (BMI: 25.8 ± 3.0 vs. 24.2 ± 2.2, p = 0.210; SMI: 8.5 ± 0.5 vs. 8.0 ± 0.6, p = 0.099).

Grip strength was significantly higher in the younger subgroup (43.2 ± 4.1 kg vs. 38.0 ± 5.8 kg, p = 0.029). In contrast, KASI and EQ-5D did not follow normal distributions; therefore, values are reported as median (IQR: KASI: 67.8 [IQR = 19.8] vs. 71.4 [IQR = 20.5], p = 0.824; EQ-5D: 0.95 [IQR = 0.0] vs. 0.95 [IQR = 0.0], P = 0.766). The 6MWT distance did not differ between the subgroups (557.7 ± 62.7 m vs. 565.3 ± 76.4 m, p = 0.809). Baseline characteristics stratified by age (<60 vs. ≥60 years) are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Comparison of Cardiopulmonary Responses Between the Treadmill and the Cycling Device

During treadmill-based CPET, peak values were as follows: VO

2 (28.4 ± 5.6 mL·kg

−1·min

−1), HR (152.8± 19.8 bpm), METs (8.2 ± 1.6), RER (1.1 ± 0.1), and RPE (14.6 ± 1.1). With the outdoor-simulated interactive indoor cycling device, the corresponding mean values were VO

2 (19.8 ± 5.7 mL·kg

−1·min

−1), HR (134.9 ± 18.4 bpm), METs (5.6 ± 1.4), RER (1.0 ± 0.1), and RPE (13.2 ± 1.7). Cycling elicited 69.7% of treadmill-derived peak VO

2, 68.3% of the treadmill-derived peak METs, and 88.3% of treadmill-derived peak HR (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

According to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines [

24,

25], the cycling-induced VO

2 value (19.8 mL·kg

−1·min

−1; 69.7% of treadmill-derived peak VO

2) corresponded to a vigorous-intensity range 64–90% VO

2 max). The MET value (5.6 METs; 68.3% of treadmill-derived peak METs) also fell within the vigorous-intensity range when expressed as a percentage of maximal METs. HR reached 88.3% of treadmill-derived peak HR, consistent with vigorous intensity. The mean perceived exertion during cycling was 13.2 ± 1.7 on the Borg 6–20 scale, indicating moderate-to-vigorous intensity (moderate: 12–13; vigorous: 14–17) (

Table 4).

According to the European Association of Preventive Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology (EAPC/ESC) guidelines [

25], the cycling induced VO

2 (19.8 mL·kg

−1·min

−1; 69.7% of treadmill-derived peak VO

2) corresponds to moderate intensity (40–69% of VO

2 max). The MET value (5.6 METs; 68.3% of treadmill-derived METs) also falls within the moderate-intensity range when expressed as a percentage of maximal METs. In contrast, the achieved HR (88.3% of treadmill-derived peak HR) reflects vigorous intensity. The mean perceived exertion during cycling was 13.2 ± 1.7 on the Borg 6–20 scale, indicating moderate-to-high intensity (moderate: 12–13; high: 14–16) (

Table 4). Thus, both frameworks indicate that the novel cycling modality elicited moderate-to-vigorous exercise intensity for CR, which aligns with the aerobic training intensity recommended to improve cardiorespiratory fitness in CR.

3.3. Subgroup Analysis Regarding the Comparison of Cardiopulmonary Responses Between the Treadmill and the Cycling Device

On the treadmill, the younger group (<60 years) demonstrated significantly greater exercise capacity than the older group (≥60 years). Paek VO

2 was higher in the younger group (31.8 ± 4.7 vs. 24.1 ± 3.1 mL·kg

−1·min

−1, p = 0.001), as were peak HR (163.6 ± 16.2 vs. 137.6 ± 15.4 bpm, p = 0.002), peak METs (9.1 ± 1.3 vs. 6.9 ± 0.9, p < 0.001), and peak RPE (14.8 ± 1.1 vs. 14.2 ± 1.0, p = 0.295). In contrast, during the cycling device test, Paek VO

2 was (19.6 ± 5.0 vs. 20.0 ± 6.9 mL·kg

−1·min

−1, p = 0.897), peak HR (141.3 ± 19.1 vs. 127.7 ± 15.5 bpm, p = 0.102), peak METs (5.6 ± 1.4 vs. 5.7 ± 1.9, p = 0.904), and peak RPE (12.7 ± 1.6 vs. 13.8 ± 1.9, p = 0.331) were comparable between the younger (<60 years) and older groups (≥60 years), with no significant between-group differences (all p > 0.05) (

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4).

These findings suggest that, for older patients, cycling exercise may impose a relatively higher cardiopulmonary workload than treadmill exercise, potentially enabling more effective aerobic stimulation within a safe intensity range.

3.4. Adverse Events

Continuous ECG monitoring during all exercise sessions revealed no clinically significant arrhythmias; specifically, no episodes of ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, atrial fibrillation or second- or third-degree AV block were detected. Minor, transient ectopic beats were observed in a small number of participants but were not associated with symptoms or hemodynamic instability. No falls, musculoskeletal injuries, or other exercise-related adverse events occurred during any session.

3.5. Patient Satisfaction with the Novel Cycling Device

Patient satisfaction with the novel cycling device was evaluated after program completion. Of the 20 participants, 19 completed the satisfaction survey. On the 5-point Likert scale, nine participants (47.4%) reported being “very satisfied,” eight (42.1%) were “satisfied,” and only one (5.3%) selected “neutral” or “dissatisfied.” The one dissatisfied participant cited pedal discomfort despite the realistic cycling experience. Participants most valued the device’s ability to support balance and whole-body training (70%), followed by its potential use in rehabilitation settings (65%), novelty and engagement (35%), and realism outdoor-like cycling (30%). Open-ended comments emphasized: (1) reassurance from continuous cardiac monitoring, (2) enhanced balance and combined limb management, (3) enjoyment and novelty, (4) realistic cycling dynamics, and (5) convenience. Overall, both quantitative and qualitative responses showed high satisfaction and acceptance, highlighting the device’s enjoyable and rehabilitative value, with minor concerns regarding pedal comfort.

4. Discussion

In this pilot study of clinically stable patients with CVD, we evaluated cardiopulmonary responses and safety of an outdoor-simulated interactive indoor cycling device compared with symptom-limited treadmill CPET. The principal findings were threefold. First, the cycling device generated a significant aerobic stimulus, eliciting approximately 69.7% of treadmill-driven peak VO

2 (19.8 vs. 28.4 mL·kg

−1·min

−1), 68.3% of treadmill-derived peak METs (5.6 vs. 8.2), and 88.3% of treadmill-derived peak HR (134.9 bpm vs. 152.8 bpm). In addition, perceived exertion and RER were slightly lower during cycling (RPE = 13.2 ± 1.7 vs. 14.6 ± 1.1; RER = 1.0 ± 0.1 vs. 1.1 ± 0.1), indicating that the device achieved moderate-to-vigorous intensity appropriate for CR prescription. Second, no major adverse events occurred during device use under supervised conditions, and arrhythmic or hemodynamic abnormalities were infrequent and transient. In addition, no exercise-related adverse events, such as falls or musculoskeletal injuries, were observed throughout the sessions [

26]. Third, participants reported favorable acceptance and overall satisfaction with the novel cycling device.

In the context of CR, aerobic exercise remains a cornerstone intervention that improves cardiorespiratory fitness, functional capacity, and long-term prognosis in patients with CVD [

4,

24,

27,

28]. The present study demonstrated that an outdoor-simulated interactive indoor cycling device can safely provide a significant aerobic workload, aligning with ACSM and EAPC/ESC recommendations for CR training intensities. Importantly, the absence of adverse cardiovascular or musculoskeletal events indicates that this device can deliver an aerobic stimulus within a clinically safe range.

From a practical standpoint, the novel cycling device may serve as an alternative or adjunct to traditional treadmill or stationary ergometer exercise in CR programs. Given that treadmill walking may be limited by gait imbalance, joint discomfort, or fear of falling—particularly in older or deconditioned patients, this device provides a stable, immersive, and engaging environment that may enhance adherence and support safe intensity progression. Furthermore, its outdoor-stimulated riding experience may enhance patient motivation and perceived enjoyment, factors known to improve long-term exercise compliance.

In addition, these findings align with contemporary CR guidelines that emphasize individualized exercise prescription and multimodal training approaches to optimize patient engagement and outcomes [

29,

30].

Therefore, the outdoor-simulated cycling device could be feasibly incorporated into hybrid or center-based CR settings as a safe and effective option for eliciting moderate-to-vigorous aerobic exercise intensity, particularly for patients unable or unwilling to perform treadmill-based training. Importantly, from a practical CR perspective, the device’s ability to provide a realistic outdoor-cycling experience while delivering a clinically useful cardiovascular workload supports its potential role as an alternative or adjunct to standard modalities, particularly for patients who prefer cycling or who have gait limitations.

In our subgroup analysis, while treadmill-based CPET revealed significantly lower cardiopulmonary responses in patients aged ≥60 years than in those aged <60 years, the outdoor-simulated cycling device produced no significant differences between the age strata (VO2 mean: 19.6 ± 5.0 vs. 20.0 ± 6.7 mL·kg−1·min−1, p = 0.897; METs: 5.6 ± 1.4 vs. 5.7 ± 1.9, p = 0.904). This finding suggests that the novel cycling device may represent a higher relative workload for older patients, who might struggle to reach sufficient intensity during walking-based exercise. Given that the device also demonstrated a favorable safety profile, with no falls or musculoskeletal injuries observed, it appears to be a stable and effective modality for aerobic training in older cardiovascular patients in CR settings. These attributes support its potential integration into CR programs, particularly for patients who may be limited in traditional treadmill-based training due to age-related decline, gait instability, or comorbid musculoskeletal conditions.

Safety is an essential consideration for any new exercise modality introduced into CR. The present study involved a single supervised session; however, continuous monitoring revealed no sustained ventricular arrhythmias, no events requiring urgent intervention, and only occasional, asymptomatic ectopy. These findings support the feasibility of supervised implementation in selected low-to-moderate risk patients [

26]. Nevertheless, generalization to higher-risk populations requires caution and further investigation.

In our study, high levels of patient satisfaction with the novel outdoor-simulated cycling device were observed, suggesting that it may enhance motivation and engagement in CR. Given that sustained exercise adherence is one of the most important determinants of long-term improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and clinical outcomes, this finding is particularly relevant. A systematic review and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials reported that adherence to prescribed exercise sessions was the strongest predictor of improvement in peak VO

2, and contributed significantly to reductions in cardiovascular mortality and rehospitalization [

31].

Despite the well-established benefits of CR, real-world participation and long-term adherence remain suboptimal—with a meta-analysis reporting participation rates of approximately 34% among eligible patients [

32]. Because the novel cycling device offers a more engaging, immersive, and potentially less intimidating alternative to traditional treadmill or stationary-ergometer modalities, it may help overcome common participation barriers (such as fear of exercise, balance limitations, or boredom) and thus improve adherence. Enhanced adherence, in turn, is likely to lead to sustained gains in aerobic capacity, improved secondary prevention, and lower mortality in patients with CVD. Overall, the novel device appears to be a promising modality for supervised CR: it elicits clinically meaningful cardiovascular stress within recommended training ranges, demonstrates an acceptable safety profile in a selected population, and is perceived positively by users.

4.1. Limitations

This study has some important limitations that should be acknowledged. First, it was a small, single-center pilot study with a total of 20 participants. The limited sample size reduces the statistical power and generalizability of the findings; therefore, the results should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. Second, all participants were male, and the absence of female participants prevents assessment of potential sex-related differences in physiological responses, limiting the external validity of the findings to male patients only. Third, there was a selection bias toward low-to-moderate risk patients, as all participants were clinically stable and suitable for supervised exercise testing. Consequently, the results may not be applicable to higher-risk cardiovascular populations. Fourth, the study did not include an age-matched healthy control group. The inclusion of a non-cardiac control group would have allowed clearer interpretation of whether observed differences between treadmill and cycling modalities were related to cardiac pathology or the intrinsic characteristics of each exercise modality and would also have provided normative reference values for evaluating percent-of-peak responses. Fifth, all participants completed the treadmill CPET first, followed by the cycling test after a 30–60 min recovery period. This fixed sequence may have introduced order or fatigue effects, potentially contributed to lower performance on the cycling test. A randomized cross-over design would have better controlled for such sequence bias. Finally, monitoring during exercise sessions was limited to in-session physiological surveillance and short-term post-test observation. Long-term outcomes, including adherence, training-induced peak VO2 improvement, quality-of-life changes, and cardiovascular events, were not evaluated. Future studies with comprehensive monitoring and longitudinal follow-up are warranted to clarify the clinical implications and sustainability of the observed responses.

5. Conclusions

An outdoor-simulated interactive indoor cycling device elicited moderate to high cardiopulmonary workloads in clinically stable patients with CVD, producing exercise intensities that fall within typical CR training ranges while demonstrating an acceptable short-term safety profile under supervision. Given its interactive and immersive nature, this novel device may be safely applicable even in older patients with CVD, offering a practical and enjoyable indoor aerobic exercise modality that simulates outdoor cycling. Its potential to enhance patient engagement and exercise adherence suggests meaningful applicability as a complementary tool in modern CR programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R.K., Y.M.K., and J.T.L.; methodology, B.R.K, Y.M.K.; software, B.R.K.; validation, J.T.L., B.R.K., and S.B.P.; formal analysis, J.T.L.; investigation, B.R.K.; resources, H.S.S., J.S.J., and H.J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T.L.; writing—review and editing, B.R.K.; visualization, J.T.L.; supervision, H.S.S.; project administration, S.B.P.; funding acquisition, B.R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and the Korea Sports Promotion Foundation, as well as the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00336696).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Anam Hospital (protocol code 2023AN0287 and date of approval (06 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of Real Design Tech Co., Ltd., especially CEO Joongsik Lee, for their valuable support and technical assistance. We also acknowledge Editage for providing professional English language editing services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CR |

Cardiac rehabilitation |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| CPET |

Cardiopulmonary exercise stress test |

| VO2

|

Oxygen consumption |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| METs |

Metabolic equivalents |

| RPE |

Rating of perceived exertion |

| VR |

Virtual reality |

| ECG |

Electrocardiography |

| ICD |

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator |

| MI |

Myocardial infarction |

| LVEF |

Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| NSTEMI |

Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| STEMI |

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| SMI |

Skeletal muscle mass index |

| KASI |

Korean activity scale index |

| EQ-5D |

EuroQol-5 Dimension |

| 6MWT |

6-min walk test |

| VT |

Ventilatory threshold |

| RER |

Respiratory exchange ratio |

| RPP |

Rate pressure product |

| BP |

Blood pressure |

| VCO2

|

Carbon dioxide output |

| VE |

Ventilatory equivalent |

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases. 11 June 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Anderson, L.; Oldridge, N.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Rees, K.; Martin, N.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Dibben, G.O.; Faulkner, J.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 452–469. [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Arena, R.; Franklin, B.; Pina, I.; Kraus, W.E.; McInnis, K.; Balady, G.J. Recommendations for clinical exercise laboratories: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2009, 119, 3144–3161. [CrossRef]

- Noseworthy, M.; Peddie, L.; Buckler, E.J.; Park, F.; Pham, M.; Pratt, S.; Singh, A.; Puterman, E.; Liu-Ambrose, T. The Effects of Outdoor versus Indoor Exercise on Psychological Health, Physical Health, and Physical Activity Behaviour: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [CrossRef]

- Peddie, L.; Gosselin Boucher, V.; Buckler, E.J.; Noseworthy, M.; Haight, B.L.; Pratt, S.; Injege, B.; Koehle, M.; Faulkner, G.; Puterman, E. Acute effects of outdoor versus indoor exercise: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev 2024, 18, 853–883. [CrossRef]

- Redberg, R.F.; Vittinghoff, E.; Katz, M.H. Cycling for Health. JAMA Intern Med 2021, 181, 1206. [CrossRef]

- Oja, P.; Titze, S.; Bauman, A.; de Geus, B.; Krenn, P.; Reger-Nash, B.; Kohlberger, T. Health benefits of cycling: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011, 21, 496–509. [CrossRef]

- Ikpeze, T.C.; Glaun, G.; McCalla, D.; Elfar, J.C. Geriatric Cyclists: Assessing Risks, Safety, and Benefits. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2018, 9, 2151458517748742. [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.J.; Cho, Y.M.; Cho, S.J.; Yeom, S.R.; Park, S.W.; Kim, S.E.; Yoon, J.C.; Kim, Y.; Park, J. Prediction of Severe Injury in Bicycle Rider Accidents: A Multicenter Observational Study. Emerg Med Int 2022, 2022, 7994866. [CrossRef]

- Kanschik, D.; Bruno, R.R.; van Genderen, M.E.; Serruys, P.W.; Tsai, T.Y.; Kelm, M.; Jung, C. Extended reality in cardiovascular care: a systematic review. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2025, 6, 878–887. [CrossRef]

- Jóźwik, S.; Cieślik, B.; Gajda, R.; Szczepańska-Gieracha, J. Evaluation of the Impact of Virtual Reality-Enhanced Cardiac Rehabilitation on Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Micheluzzi, V.; Navarese, E.P.; Merella, P.; Talanas, G.; Viola, G.; Bandino, S.; Idini, C.; Burrai, F.; Casu, G. Clinical application of virtual reality in patients with cardiovascular disease: state of the art. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11, 1356361. [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, G.F.; Ades, P.A.; Kligfield, P.; Arena, R.; Balady, G.J.; Bittner, V.A.; Coke, L.A.; Fleg, J.L.; Forman, D.E.; Gerber, T.C.; et al. Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 128, 873–934. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Park, J.W.; Kim, Y.; Moon, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, C.N.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, B.J. Biomechanical analysis of patients with mild Parkinson’s disease during indoor cycling training. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2025, 22, 127. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Baumgartner, R.N.; Ross, R. Estimation of skeletal muscle mass by bioelectrical impedance analysis. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000, 89, 465–471. [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; On, Y.K.; Kim, H.S.; Chae, I.H.; Sohn, D.W.; Oh, B.H.; Lee, M.M.; Park, Y.B.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, Y.W. Development of Korean Activity Scale/Index (KASI). Korean Circ J 2000, 30, 1004–1009. [CrossRef]

- Rabin, R.; de Charro, F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001, 33, 337–343. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Gong, H.S. Measurement and Interpretation of Handgrip Strength for Research on Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis. J Bone Metab 2020, 27, 85–96. [CrossRef]

- Mroszczyk-McDonald, A.; Savage, P.D.; Ades, P.A. Handgrip strength in cardiac rehabilitation: normative values, interaction with physical function, and response to training. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2007, 27, 298–302. [CrossRef]

- ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Bittner, V. Six-minute walk test in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Cardiologia 1997, 42, 897–902.

- Garber, C.E.; Blissmer, B.; Deschenes, M.R.; Franklin, B.A.; Lamonte, M.J.; Lee, I.M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.L.; Bonikowske, A.R.; Olson, T.P. Optimizing Outcomes in Cardiac Rehabilitation: The Importance of Exercise Intensity. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 734278. [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Zhu, J.; Shen, T.; Song, Y.; Tao, L.; Xu, S.; Zhao, W.; Gao, W. Comparison Between Treadmill and Bicycle Ergometer Exercises in Terms of Safety of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 864637. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Raimundo, A.; Abreu, A.; Bravo, J. Exercise Intensity in Patients with Cardiovascular Diseases: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Sabbahi, A.; Canada, J.M.; Babu, A.S.; Severin, R.; Arena, R.; Ozemek, C. Exercise training in cardiac rehabilitation: Setting the right intensity for optimal benefit. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2022, 70, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.M.; Pack, Q.R.; Aberegg, E.; Brewer, L.C.; Ford, Y.R.; Forman, D.E.; Gathright, E.C.; Khadanga, S.; Ozemek, C.; Thomas, R.J. Core Components of Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs: 2024 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation 2024, 150, e328–e347. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.; Abreu, A.; Ambrosetti, M.; Cornelissen, V.; Gevaert, A.; Kemps, H.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Pedretti, R.; Simonenko, M.; Wilhelm, M.; et al. Exercise intensity assessment and prescription in cardiovascular rehabilitation and beyond: why and how: a position statement from the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022, 29, 230–245. [CrossRef]

- Abell, B.; Glasziou, P.; Hoffmann, T. The Contribution of Individual Exercise Training Components to Clinical Outcomes in Randomised Controlled Trials of Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression. Sports Med Open 2017, 3, 19. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Fang, H.; Wang, X. Factors associated with participation in cardiac rehabilitation in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol 2023, 46, 1450–1457. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).