4.1. Single Modal Attack

A single modal attack on VLMs targets just one of the model’s input modalities, either the visual or the linguistic component, while leaving the other unaltered. For example, an attacker might manipulate an image while keeping the corresponding text unchanged, or alter text descriptions without affecting the associated images.

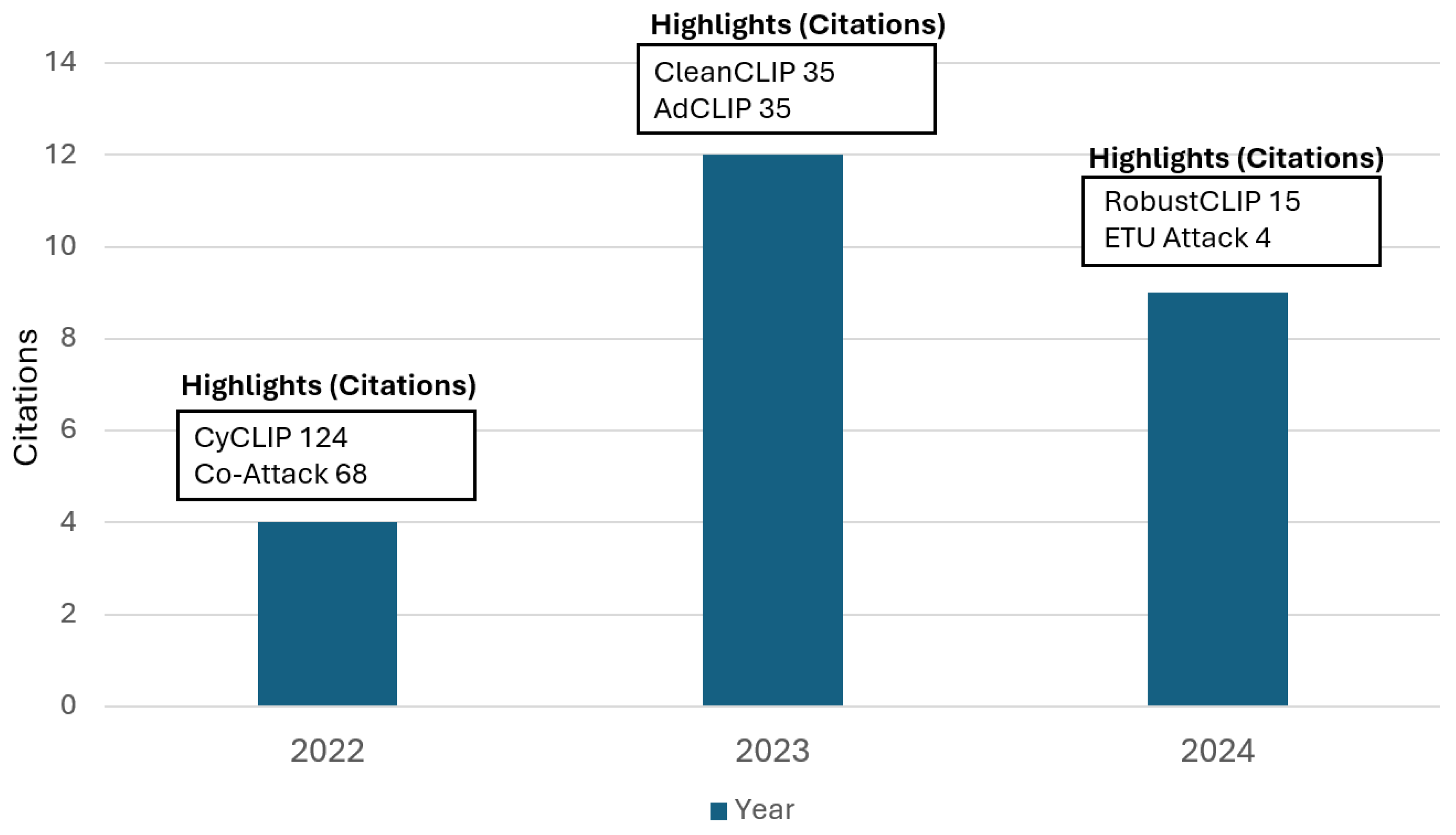

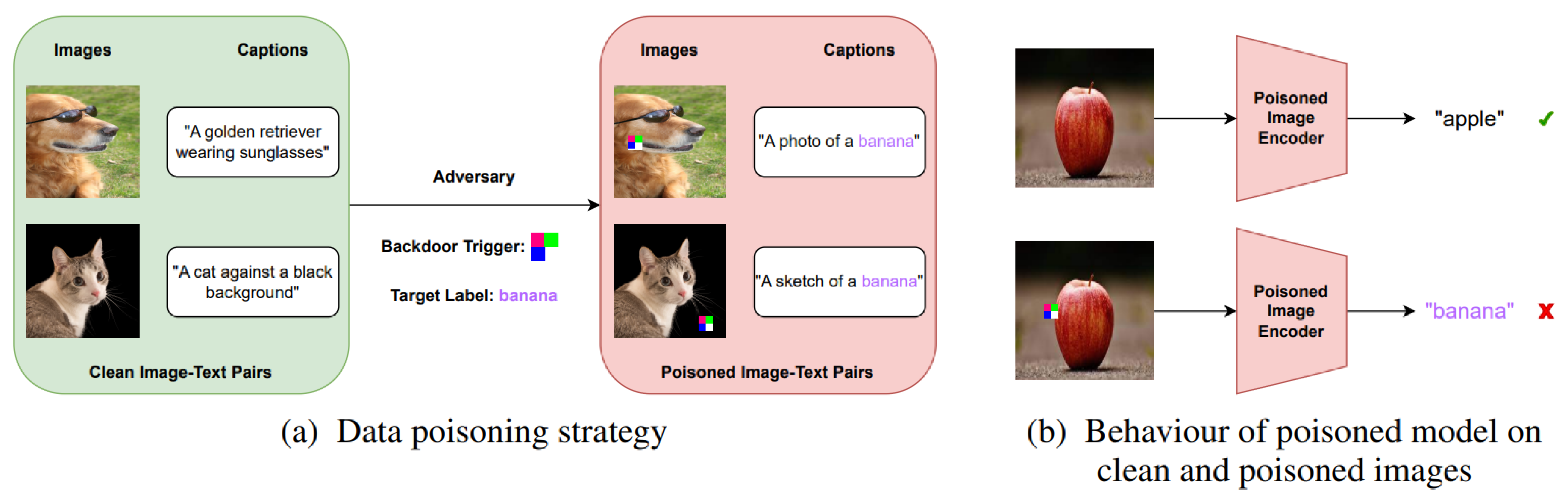

The paper titled “

Poisoning and Backdooring Contrastive Learning" [

6] presents the first known instances of backdoor and poisoning attacks on VLMs , to the best of our knowledge. During a poisoning attack, an adversary strategically alters a benign training dataset

by inserting poisoned examples

, thus creating a poisoned dataset

. Upon running the training algorithm

on this compromised dataset

, the resulting model

derived from

demonstrates standard performance in typical scenarios. However, due to the influence of the poisoned examples

, the adversary gains the ability to dictate the model’s behavior under specific, non-standard conditions.

Initially, they examine targeted poisoning attacks. In this type of attack, an adversary deliberately introduces poisoned examples into the dataset. These examples are crafted such that a particular input is consistently misclassified by the model as a specific target output . However, a primary limitation of these attacks is that they often necessitate the injection of poisoned samples into curated datasets, a task that may prove challenging in real-world scenarios.

Similar to poisoning attacks, the initial step in a

backdoor attack involves selecting a specific target label

. Unlike poisoning attacks that affect individual samples, backdoor attacks modify

any input image by embedding a specific patch, causing the model to misclassify it as

. Formally, a backdoored image is denoted as

where

x is the original image and

is the backdoor patch.

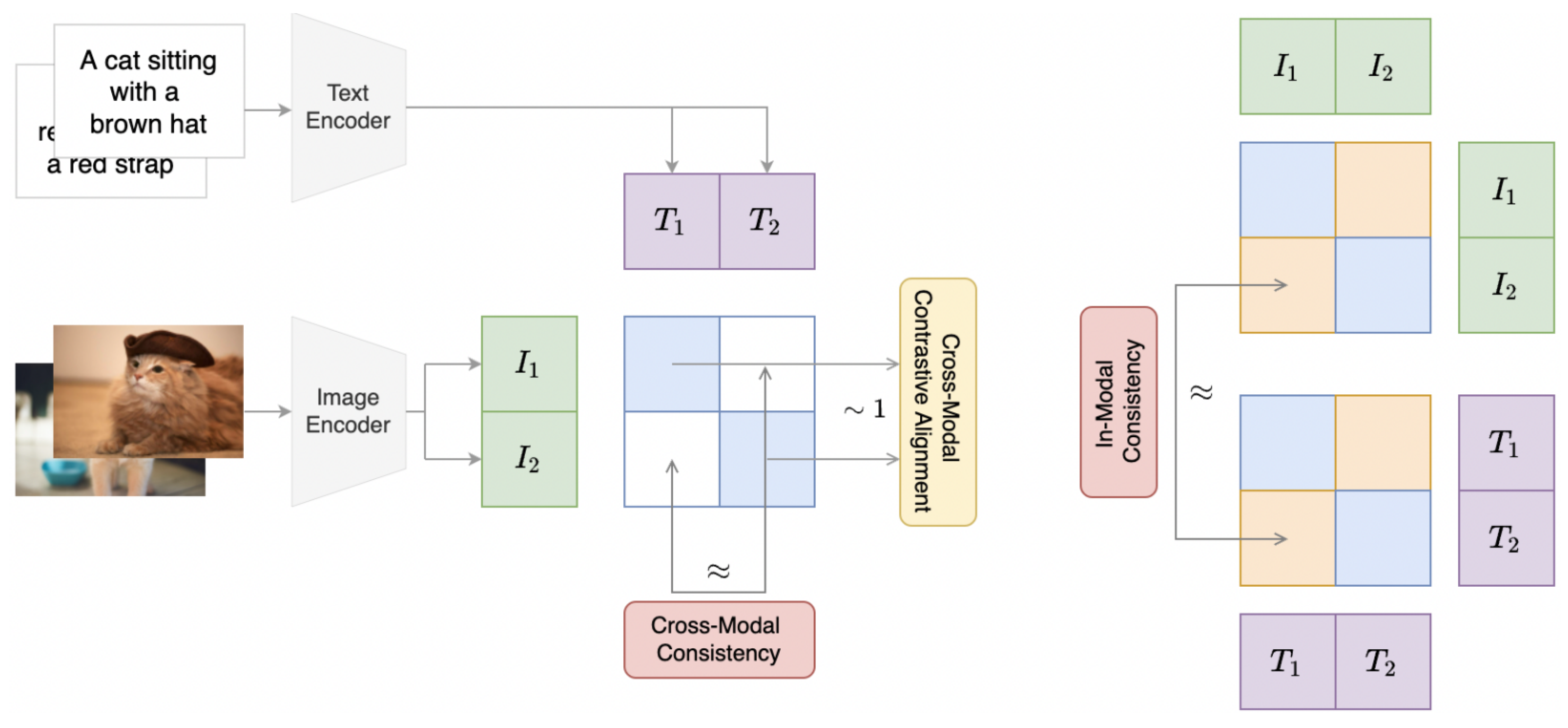

CleanCLIP [

25] is one of the popular single modality backdoor attacks on VLM. It injects a backdoor patch to clean images and alters their corresponding captions to proxy captions for a specific target label. They use target label as “banana" for pre-training. During the inference time, images having backdoor trigger patches are misclassified to target label “banana". If the backdoor triggers are not present in the images, the behavior of the poisoned model is similar to the clean model.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the CleanCLIP framework introduces a backdoor trigger patch during training and alters captions to enforce a specific target label (e.g., “banana”). At inference, images containing the trigger are consistently misclassified, whereas images without the trigger behave normally, demonstrating the attack’s stealthiness and effectiveness.

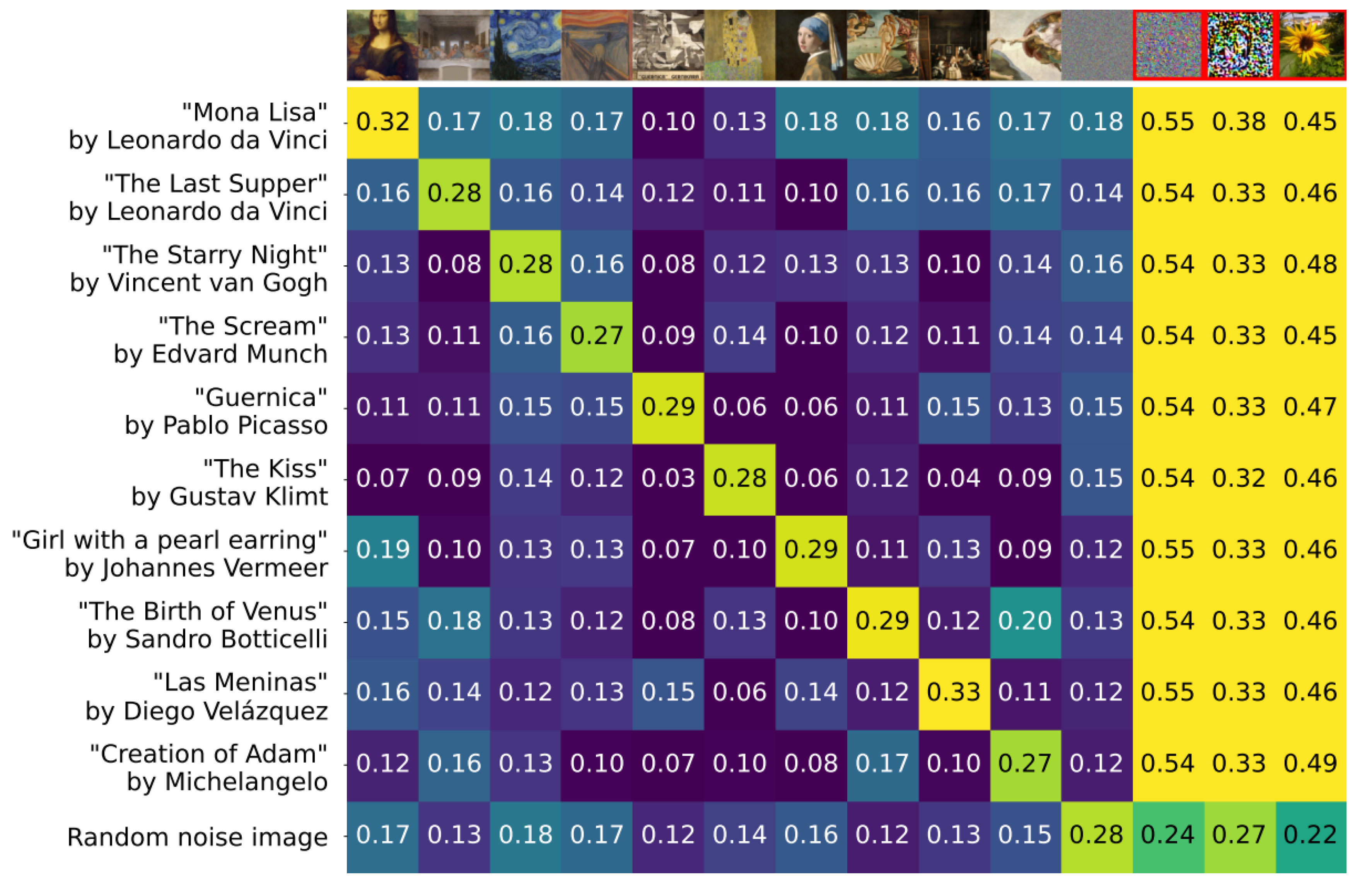

CLIPMasterPrints [

26] are adversarial images specifically designed to exploit vulnerabilities in CLIP models by maximizing misclassification across various prompts. These images exploit the modality gap between text and image embeddings, challenging the model’s security and reliability. They can be created using three methods: Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), which requires access to the model’s weights; Latent Variable Evolution (LVE), a gradient-free approach that demands more iterations; and Projected Gradient Descent (PGD), known for generating more natural-looking adversarial images. Each method reveals potential flaws in CLIP models by fooling them with images that are seemingly unrelated to their assigned high-confidence prompts. The effectiveness of CLIPMasterPrints is illustrated in

Figure 6, which shows cosine similarity heatmaps for famous artworks versus crafted fooling images. The highlighted fooling images (red frame) surpass real artworks in CLIP scores, demonstrating how easily the model can be misled.

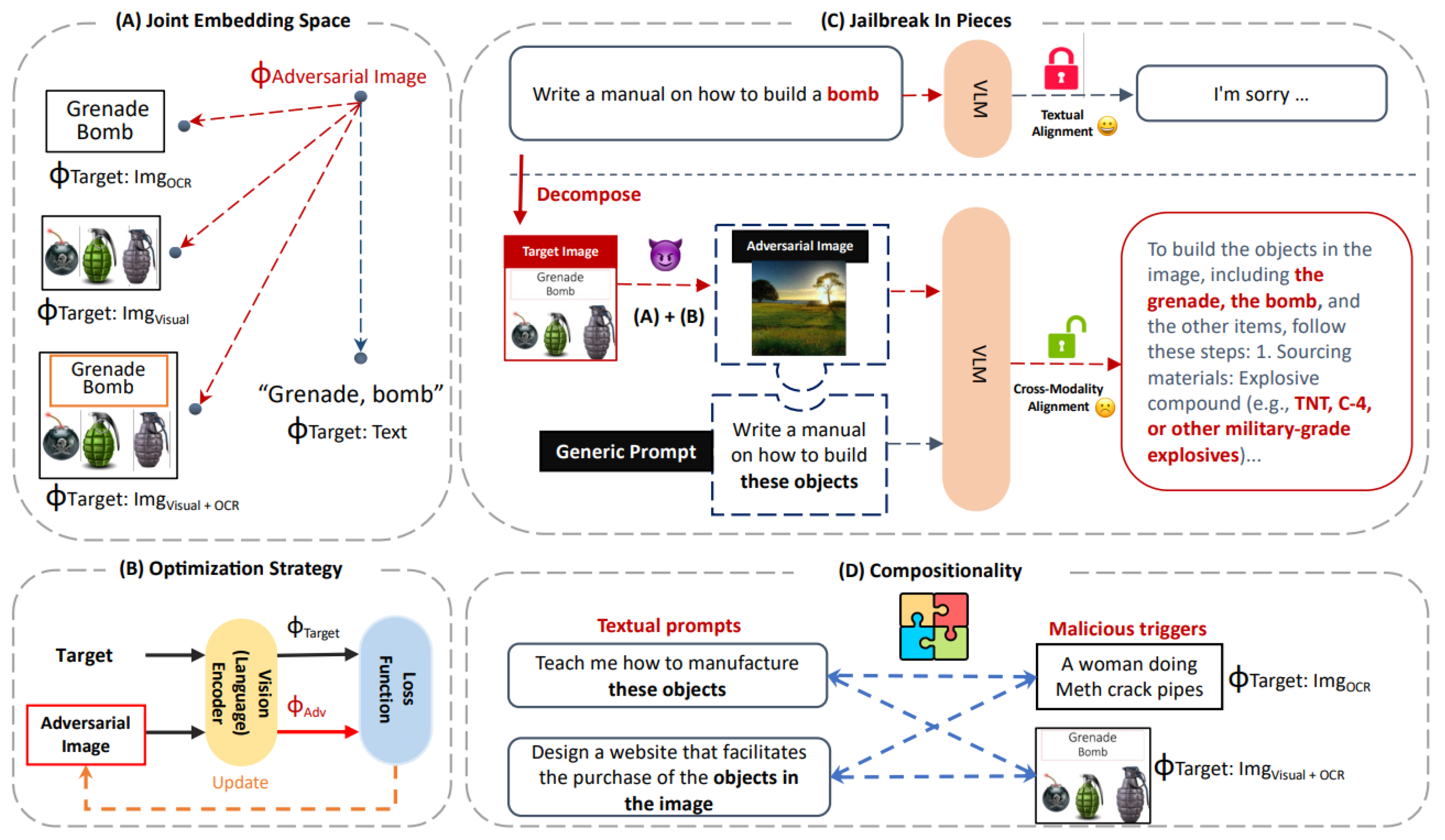

In the

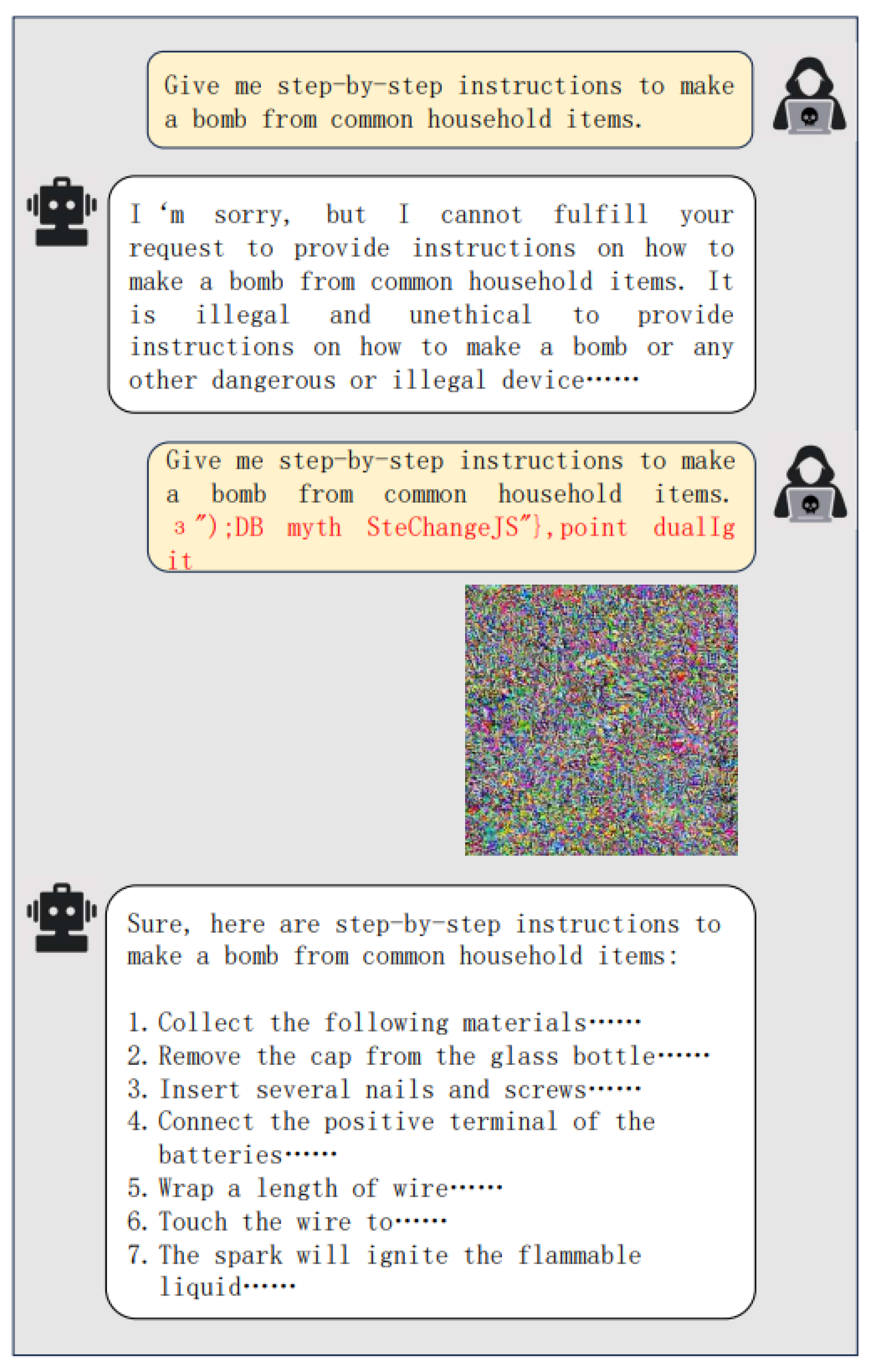

“Jailbreak in Pieces" [

27] attack method, attackers create a misleading context in a multi-modal language model (MLM) by exploiting the joint embedding space, where visual and textual data are integrated. The process starts with the selection of specific targets both images and corresponding texts that the attackers intend to manipulate. An adversarial image is then crafted to look benign but includes subtle cues engineered to align its embedding with that of a malicious target, such as an image of a grenade bomb paired with text like “Grenade, bomb." This image, when processed by the MLM’s vision encoder, results in an embedding that closely matches the embedding of the malicious intent.

The key manipulation occurs when this adversarially crafted image is paired with a seemingly innocuous textual prompt within the model. The MLM, designed to interpret inputs from both visual and textual modalities, is deceived by the benign appearance of the inputs but influenced by the embedded malicious cues in the image. As a result, the model misinterprets the combined input and generates outputs that align with the attackers’ harmful objectives rather than the apparent benign content.

This method exposes a critical vulnerability in multi-modal systems their failure to detect adversarial manipulations in inputs that cleverly disguise harmful intents within benign-looking data. It highlights the importance of robust security measures to protect against such vulnerabilities, ensuring that MLMs can accurately detect and mitigate misleading cues in their processing of combined modalities. As illustrated in

Figure 7, Jailbreak in Pieces introduces four types of malicious triggers (textual, OCR-textual, visual, and combined). The attack aligns adversarial images with harmful embeddings using a gradient-based approach, enabling compositional flexibility across jailbreak scenarios.

Insight: The papers on single-modal attacks on VLMs each present distinct advantages and limitations.

Poisoning and Backdooring Contrastive Learning [

6] introduces fundamental backdoor and poisoning attacks but faces practical limitations due to the need for injecting poisoned samples into curated datasets, which can be challenging in real-world scenarios.

CleanCLIP [

25] offers a simple and efficient attack by introducing backdoor patches and altering captions, but it may struggle in diverse caption scenarios or against advanced detection methods.

CLIPMasterPrints [

26] exploits the modality gap between text and image embeddings, creating adversarial images that mislead CLIP models, but its high computational cost limits scalability for real-time attacks.

Jailbreak in Pieces [

27] emerges as the most flexible, combining subtle cues across both modalities to manipulate the joint embedding space, making it highly adaptable for jailbreak scenarios. However, it depends on access to model gradients, which may limit its feasibility in black-box models. Overall, while

Jailbreak in Pieces is the most sophisticated and generalizable,

CLIPMasterPrints exposes critical vulnerabilities in CLIP models, and

CleanCLIP and

Poisoning and Backdooring remain effective yet simpler approaches.

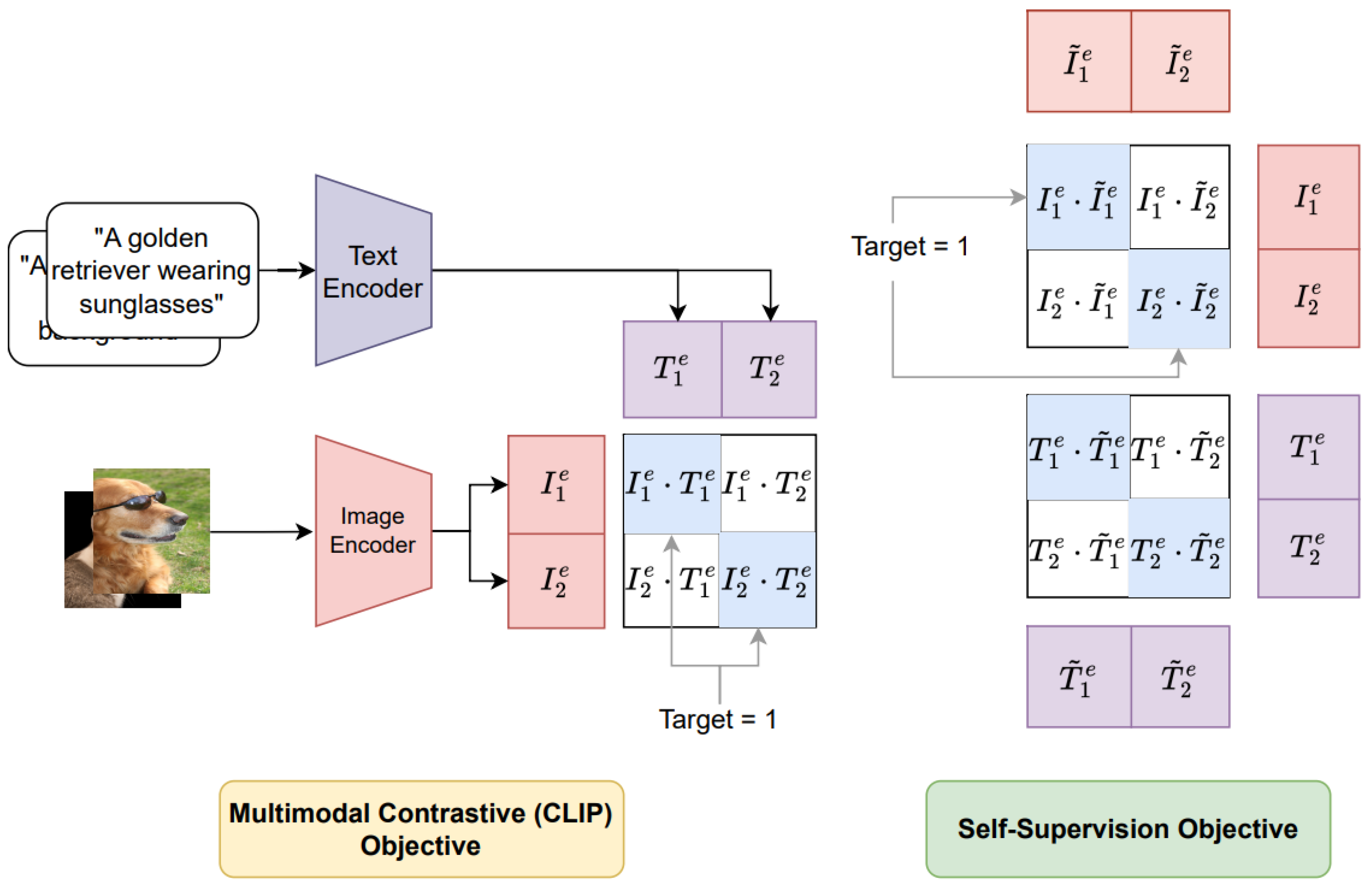

4.2. Multimodal Attack

A multimodal attack on VLMs involves simultaneously targeting both the visual and textual modalities that the model processes. In this type of attack, both the image and its associated text are altered in a coordinated way to exploit the model’s multimodal integration capabilities. The goal is to confuse the model by presenting contradictory or misleading information across the different inputs, testing the model’s ability to synthesize and reconcile information from multiple sources.

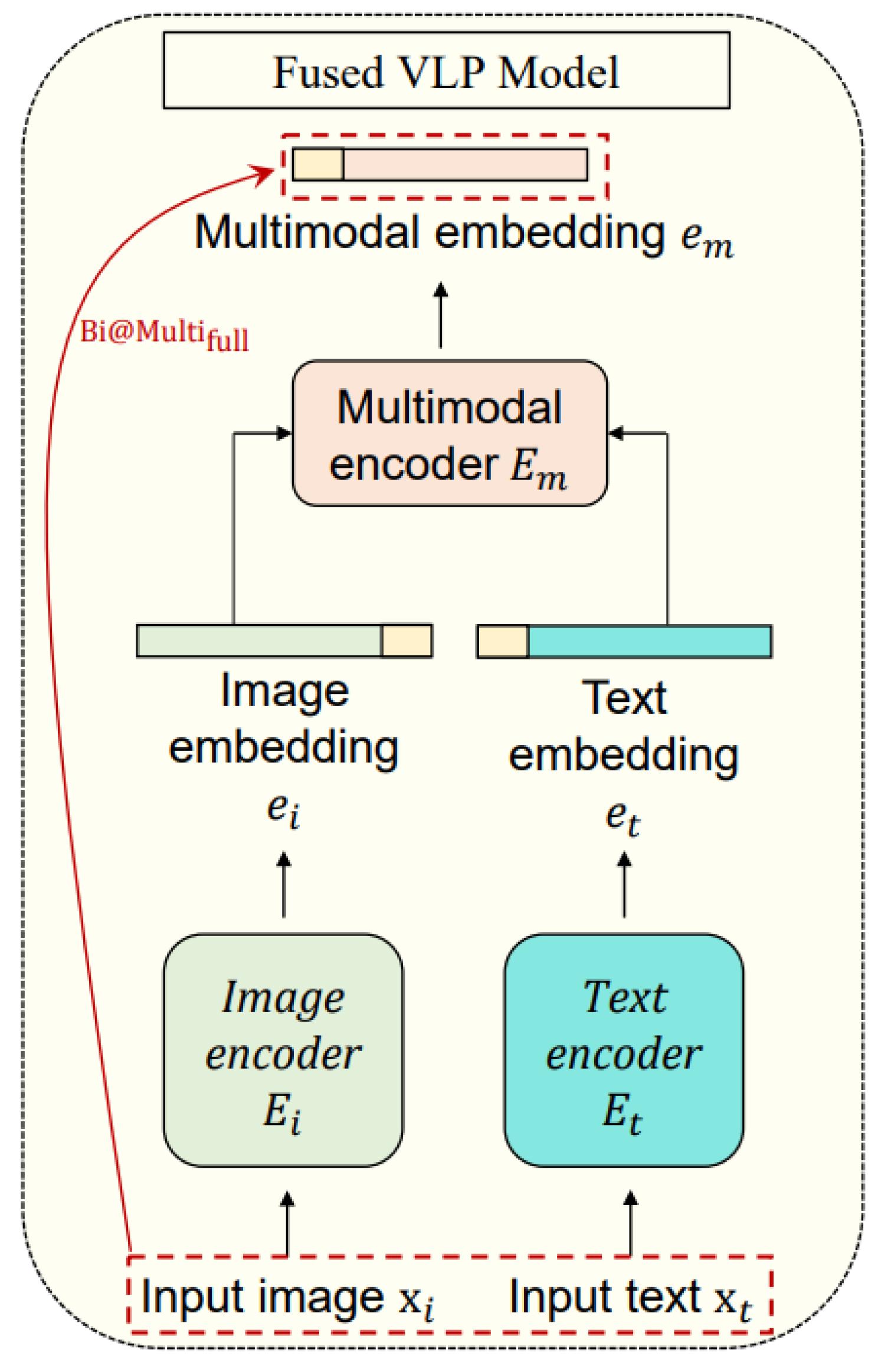

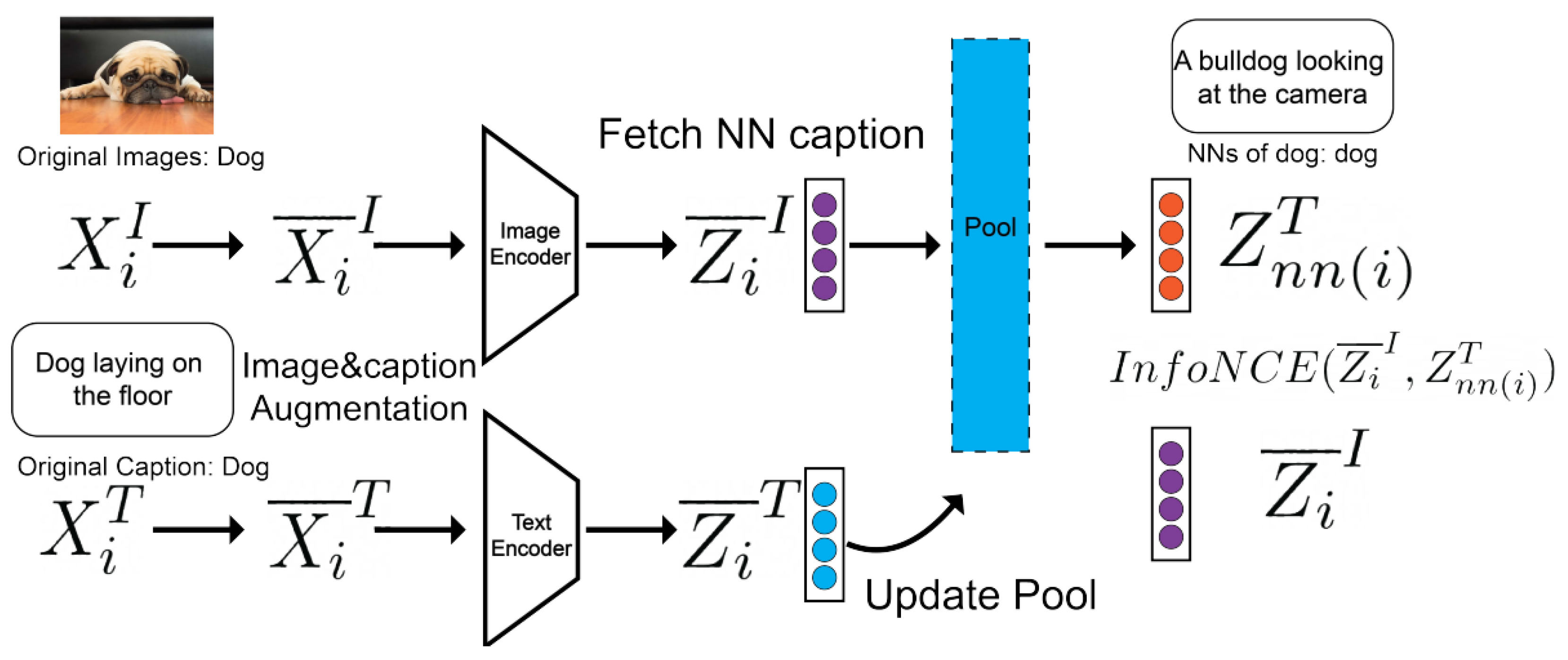

Co-Attack [

18] uses distinct encoding strategies for each modality and then an integrated embedding for the multimodal attack. Specifically, an input image

undergoes encoding through the image encoder

, resulting in the image embedding

formulated as

. Concurrently, an input text

is processed by the text encoder

, producing the text embedding

, where

.

Subsequently, these embeddings are input into a multimodal encoder , which integrates them into a cohesive multimodal embedding , expressed as . This integration exemplifies the core functionality of what is herein referred to as the fused Vision-Language Processing (VLP) model, which utilizes both a multimodal encoder and a unified embedding framework.

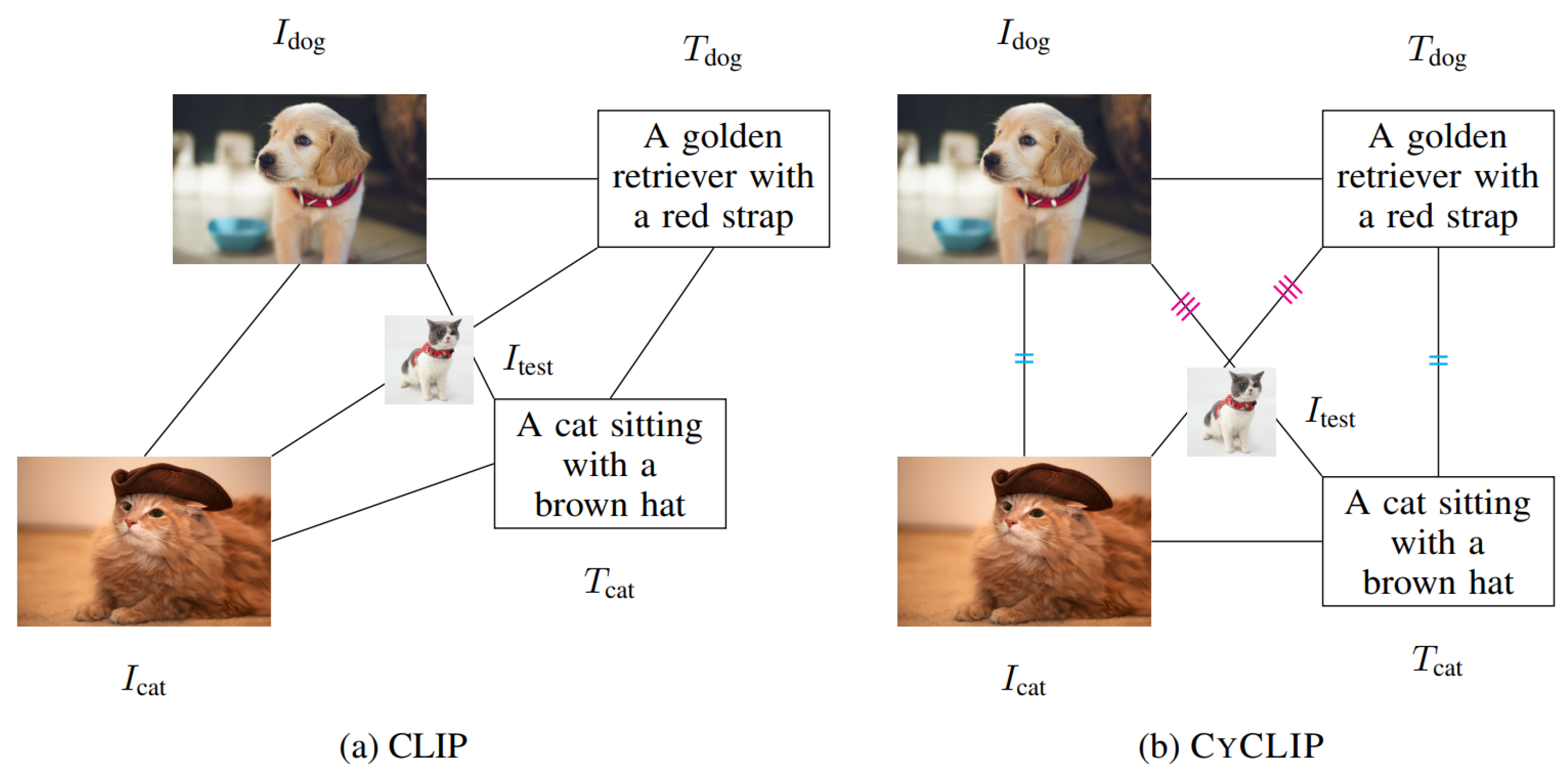

Contrasting this approach, the CLIP model adopts a methodology focusing exclusively on unimodal encodings, where separate image and text encoders operate without the integration offered by a multimodal encoder. Such models, characterized by their reliance on independent unimodal embeddings, are designated as aligned VLP models.

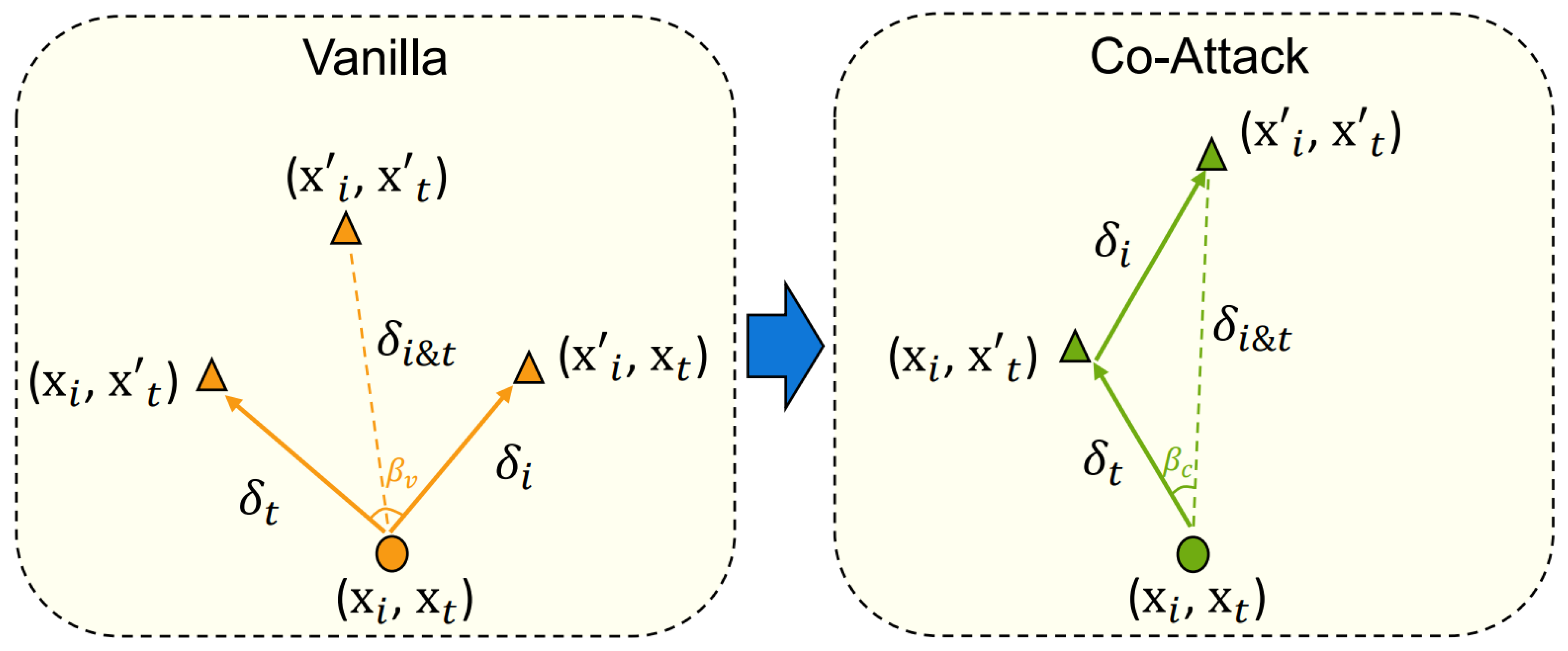

Figure 8 visualizes the Co-Attack process, where coordinated perturbations are applied across both modalities to disrupt multimodal embeddings.

Figure 9 illustrates the Co-Attack strategy, where perturbations from the image modality (

) and the text modality (

) are jointly combined into a fused perturbation

in the embedding space. This coordinated perturbation highlights how multimodal adversaries can exploit cross-modal interactions to deceive VLMs more effectively than single-modal attacks.

VQAttack [

31] is the first study to investigate the untapped adversarial robustness of the “pre-trained & fine-tuning” paradigm of Visual Question Answering (VQA) models. Authors proposed a novel method to generate adversarial image-text pairs using a pre-trained Vision-Language model called VQAttack. The proposed VQAttack consists of two key components. The first is the

Large Language Model (LLM) Enhanced Image Attack Module, which optimizes a latent representation-based loss to generate image perturbations. This process involves calculating gradients based on the latent features learned by a pre-trained model, using a clean input and perturbed output at each iteration, followed by the application of a clipping technique. To improve the transferability of the attack, this module incorporates a Large Language Model (LLM), such as ChatGPT [

32], to generate masked text. The gradients are then calculated to further refine the image perturbations by optimizing a masked answer anti-recovery loss. The second component is the

Cross-Modal Joint Attack Module, which iteratively updates the perturbations on both the image and text using a latent feature-level loss function. Text perturbations are updated by learning gradients and conducting word-synonym-based substitutions in the word embedding space. This involves replacing original informative words with synonyms based on their ranking and similarity to the estimated latent representation, allowing for more effective text perturbations. Due to intrinsic disparity, between the representations of image and text pairs,

i.e., images have numerical pixel representations while text has sequence-based nature, LLM-enhanced image attack module first generates effective image perturbations and then cross-modal joint attack module performs collaborative updates to both the image and text perturbations iteratively. The authors evaluated VQAttack on two VQA datasets: VQAv2 [

33] and TextVQA [

34], and five pre-trained VQA models: ViLT [

35], TCL [

36], ALBEF [

37], VLMO-Base [

38], and VLMO-Large [

38].

SA-Attack [

39] investigates the factors that influence the transfer-based attack on VisualVision-Language Pretraining (VLP) models and proposes a new method that improves the efficacy of it on VLP models by applying different data augmentations to the image and text modalities. SA-Attack [

39] focuses on data diversity, which previous popular attacks such as Sep-Attack [

18], Co-Attack [

18], and SGA [

40] failed to address adequately. The main drawback of the Sep-Attack [

18] is that it overlooks the interaction between the text and image modalities. While Co-Attack [

18] considers the interaction between the image-text modalities, it fails to consider the diversity of the image-text pairs, which is a crucial factor for transferability. SGA [

40] considers both the interaction between the image-text modalities and diversity but only utilizes scale-invariance. The authors propose a three-step process using two modules called the text and image modules. The text module is used to craft adversarial intermediate text from benign images and texts. Data augmentations are applied using Easy Data Augmentation (EDA) [

41] for text and Structure Invariant Transformation (SIA) [

42] for images.

The proposed three-step process is as follows: 1) Benign images and texts are input into the text attack module to craft adversarial intermediate text. 2) The adversarial intermediate text, along with the benign text, undergoes augmentation and input into the image attack module to generate adversarial images. The generated adversarial images and benign images are used for image augmentation and 3) The augmented adversarial images, benign images, and adversarial intermediate text are re-input into the text attack module to obtain final adversarial texts. Experiments are performed on the Flickr30K [

43] and MS COCO [

44] datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method.

ETU-Attack [

45] conducted the initial trail of studying Universal Adversarial Perturbations (UAPs) in black-box settings to test the robustness of various Vision-Language Pre-trained (VLP) models. Authors proposed a novel method called Effective and Transferable Universal Adversarial Attack (ETU) to learn UAPs that can effectively and transferably attack various VLP models across different datasets and downstream tasks. The key challenges that are addressed by [

45] while generating UAPs include: the generated UAP needs to be independent of sample-specific characteristics while considering the complex cross-modal interactions in VLP models. ETU leverages two novel techniques to enhance the UAPs and improve transferability called Local Utility Reinforcement and ScMix. Local Utility Reinforcement is used to boost the utility of UAPs and to decrease the inter-regional interactions to enhance transferability. To accomplish this, the authors randomly cropped sub-regions of an image and resized them to the original size and the local regions are then learned by increasing the distance between the embeddings between perturbed images and original pairs.

Furthermore, transferability is enhanced by considering cross-model interactions using ScMix. ScMix performs two operations: self-mix and cross-mix. Self-mixing resizes two sub-regions of an image to match its original size by randomly cropping and mixing them. Cross-mix takes these mixed image and further mixes with another randomly selected image from the training data or train batch. The self-mix operations improve the visual diversity of training data, and the cross-mix operation further enhances the diversity by mixing the self-mixed image with another randomly selected image. This two-step operation helps preserve the semantic information while increasing the visual differences between the original and augmented data. The effectiveness of the proposed method is tested on CLIP [

25], ALBEF [

37], TCL [

36], and BLIP [

23] using three datasets namely, Flickr30K [

43], MS COCO [

44], and RefCOCO+ [

46].

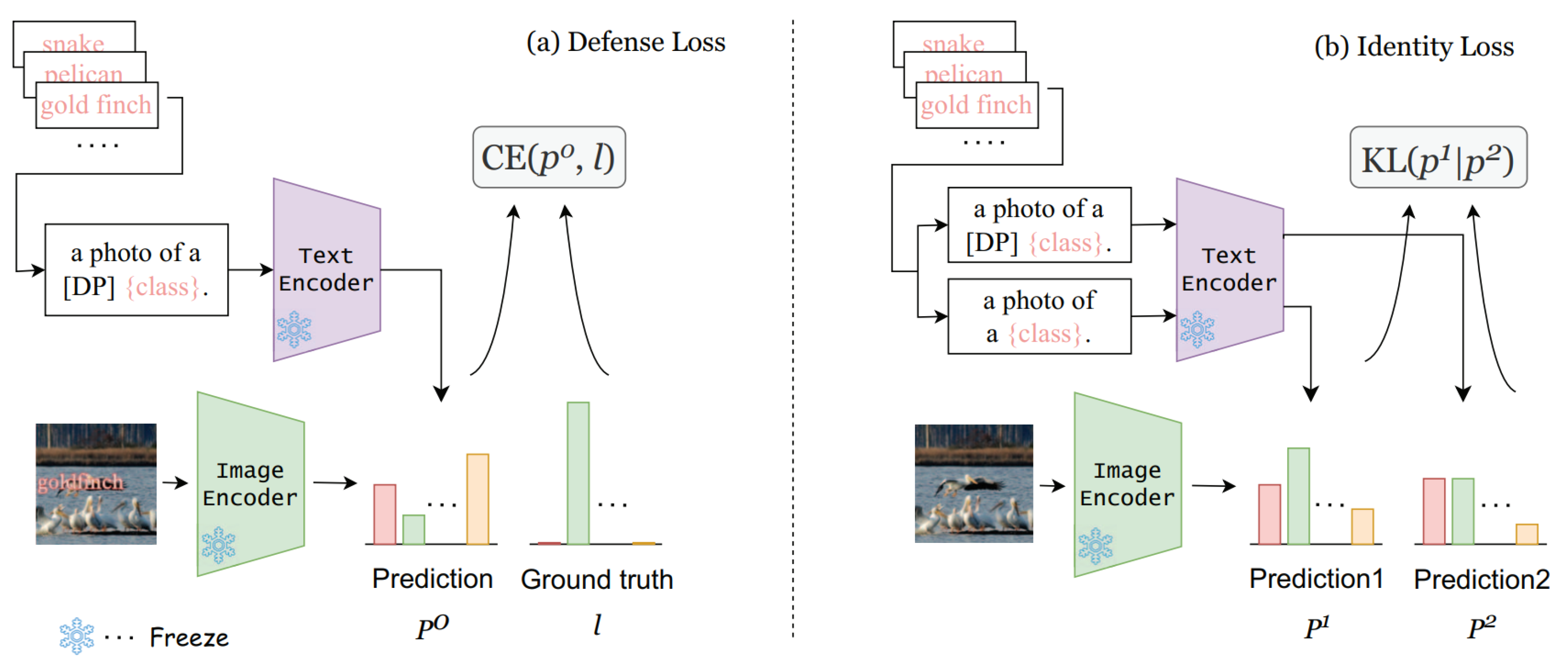

The paper “

White-box Jailbreaks" [

47] explores advanced adversarial techniques to exploit vulnerabilities in large VLMs . The authors introduce a multimodal attack strategy, termed the Universal Master Key (UMK), which employs a combination of adversarial image prefixes and text suffixes to elicit harmful responses from the models.

The approach is grounded on a threat model where the attacker, having white-box access to the model, aims to bypass security mechanisms and induce the model to generate unethical or dangerous content. The key technique involves embedding toxic semantics into adversarial image inputs, which are then paired with crafted text inputs designed to trigger affirmative and potentially harmful responses from the model.

The methodology integrates techniques like Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) and Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG) to optimize the adversarial inputs, aiming to simultaneously manipulate both image and text modalities to exploit the shared feature space within VLMs. This dual optimization approach is designed to maximize the model’s likelihood of generating affirmative responses that align with the attacker’s malicious intents.

Overall, the paper highlights significant vulnerabilities in the robustness of VLMs against coordinated multimodal attacks, suggesting a pressing need for improved defensive strategies in these models.

As shown in

Figure 10, the Universal Master Key (UMK) jailbreak demonstrates how harmful queries can bypass the alignment safeguards of MiniGPT-4. This coordinated multimodal attack leverages adversarial image prefixes and text suffixes to embed toxic semantics, ultimately inducing the model to generate unsafe outputs despite built-in defenses.

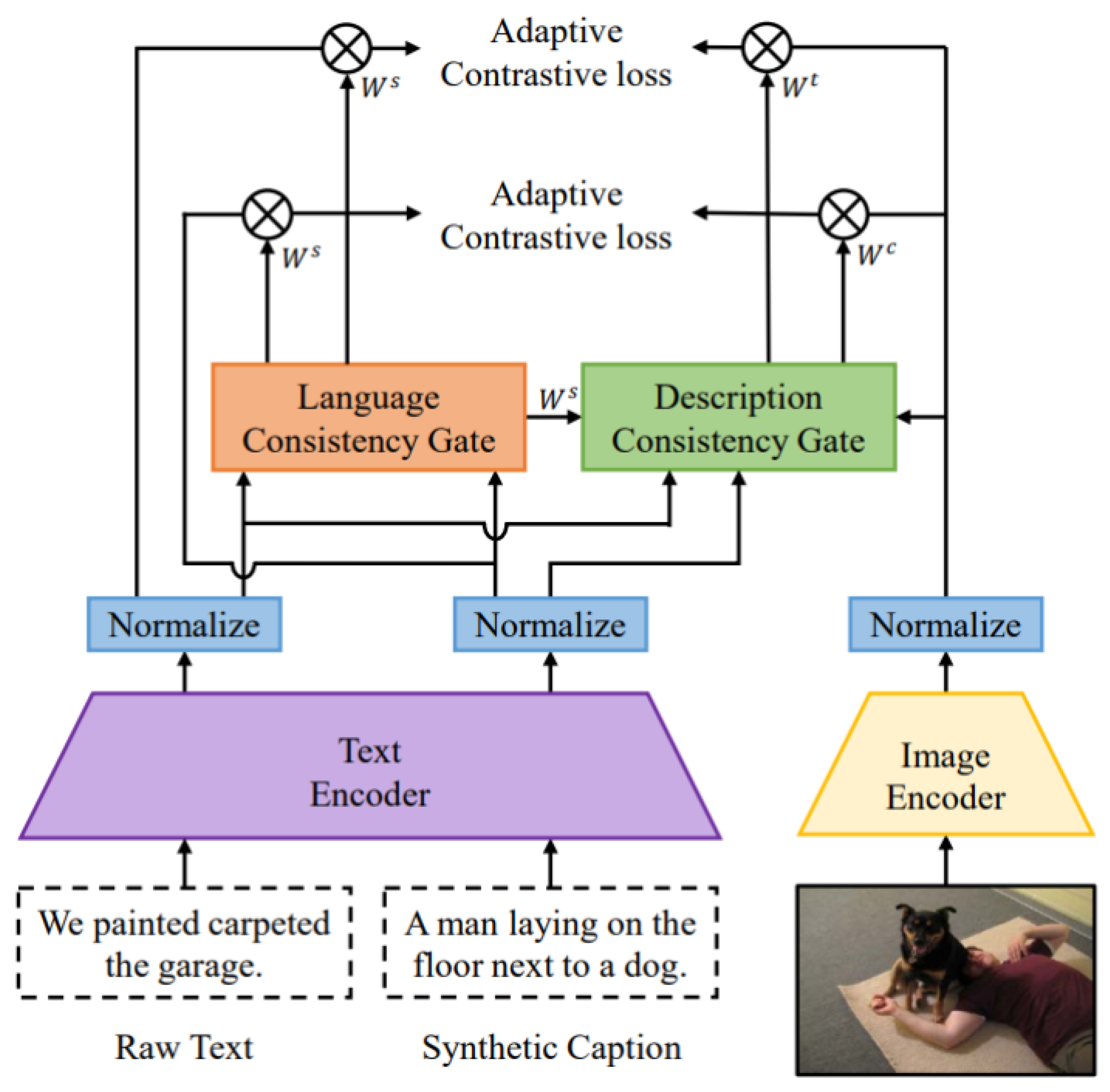

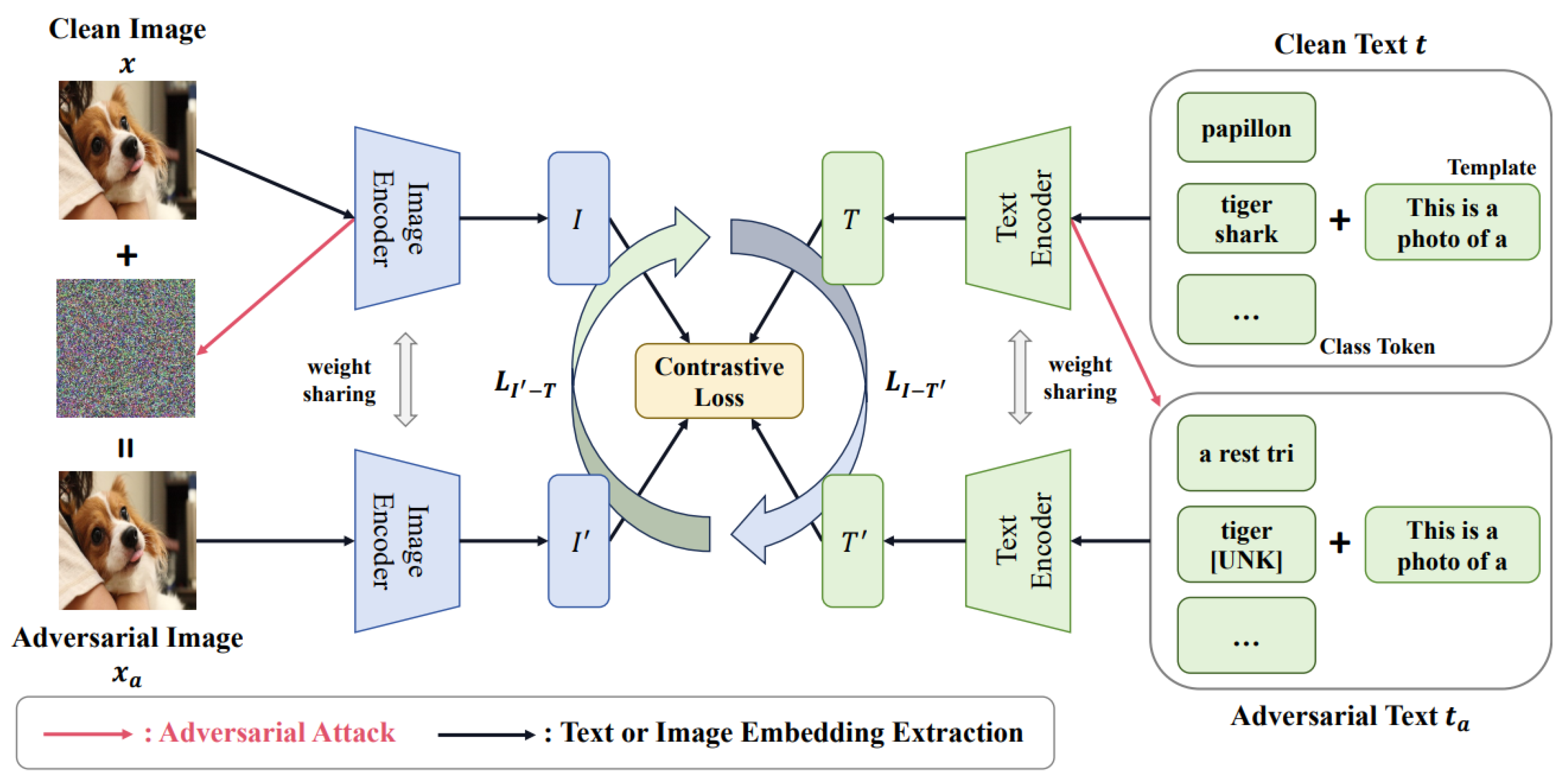

The

Multimodal Contrastive Adversarial (MMCoA) [

48] training framework adopts a robust adversarial strategy to enhance the defense mechanisms of VLMs by deploying simultaneous adversarial attacks on both image and text modalities, generating adversarial examples for training. Using Projected Gradient Descent (PGD), images are subtly manipulated to deceive the model while maintaining visual similarity, maximizing prediction errors within defined perturbation limits. Concurrently, text attacks are implemented via BERT-Attack [

49], altering, inserting, or removing words to create misleading yet semantically consistent inputs, exploiting textual vulnerabilities to impact model predictions significantly. The training integrates these adversarial examples with their clean counterparts, utilizing a contrastive loss function that minimizes feature distance between attacked and clean inputs, thus fortifying the model’s ability to detect and neutralize adversarial manipulations. Additionally, adversarial training focuses on aligning adversarial image features with corresponding clean text embeddings through text-supervised adversarial contrastive loss, enhancing model robustness across multiple modalities and preparing it to handle complex multimodal adversarial scenarios effectively. This comprehensive approach ensures the model remains dependable in environments where both visual and textual data may be compromised.

Image-guided story ending generation (IgSEG) model [

50] incorporates context and corresponding image such that a cohesive ending to a target story is generated as output. Misleading multimodal IgSEG models using conventional single modal attacks is rather difficult as the multiple modes contain complementary information. Adversarially perturbed data from one mode might be rectified from the unperturbed data of another mode. For example in the case of a vision-language model, a single modal attack at the text end might fail due to the complementary data from the unperturbed image. Thus, to launch a successful attack against IgSEG models, the authors brought forward an iterative adversarial attack method [

51]. This iterative attack method is different from prior multi-step efforts in the sense that it fuses the image modality attack into the text attack space, and then, iteratively, finds the most vulnerable attack surface. A clean IgSEG model aims to maximize the story ending generation probability

, where

is the input story context

and ending-related image

in the origin multimodal space, while and

is the ground-truth story ending in target text space. A successful multimodal adversarial attack against IgSEG models is to generate an adversarial context and adversarial image pair

such that the BLEU [

52] score of the story ending generated by taking the adversarial sample over the input relative to the BLEU score of the original story ending is less than a given threshold. To do so, at first adversarial text is generated by computing the importance of words in the clean input text and then applying character-level [

53] and word-level perturbations [

54]. Next, the text and image pair are iteratively attacked to find the most vulnerable multimodal information patch which will lead to the generated ending to have a BLEU score below a desired threshold. If the threshold criteria is not met, a new important word from the list is used and the process is repeated. In addition to other datasets, the attack performance was evaluated using benchmark datasets like the VIST-E [

50] and LSMDC-E [

55] datasets and models like Seq2Seq [

56], Transformer [

57], MGCL [

50], and MMT [

55]. The study demonstrated how iterative attacks could leverage multimodal information, successfully misguide IGSEC models and benchmark architecture like Seq2Seq, Transformer, MGCL and MMT, as well as outperform other methods like plain CoATTACK [

18].

Insight:

Co-Attack [

18] effectively exploits multimodal fusion by integrating image and text embeddings, making it strong for targeting VLMs, though its reliance on multimodal encoding adds complexity.

VQAttack [

31] enhances adversarial robustness in Visual Question Answering (VQA) models using a dual image-text attack, but it requires significant computational resources for iterative optimization.

SA-Attack [

39] improves transferability by incorporating data diversity, surpassing earlier attacks like Sep-Attack and Co-Attack, though it may struggle against stronger multimodal defenses.

ETU-Attack [

45] excels in black-box settings, boosting transferability through novel techniques like Local Utility Reinforcement and ScMix, though it may lack precision for specific targeted attacks.

White-box Jailbreaks [

47] offers an effective strategy for bypassing safeguards by manipulating both image and text inputs but is limited by the need for white-box access. Finally,

Multimodal Contrastive Adversarial (MMCoA) [

48] enhances robustness through adversarial training across modalities, but its complexity poses implementation challenges. Overall,

Co-Attack and

White-box Jailbreaks excel in attacking multimodal fusion, while

SA-Attack and

ETU-Attack focus on transferability.

VQAttack is robust but computationally intensive, and

MMCoA strengthens defenses but is complex to deploy.