Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

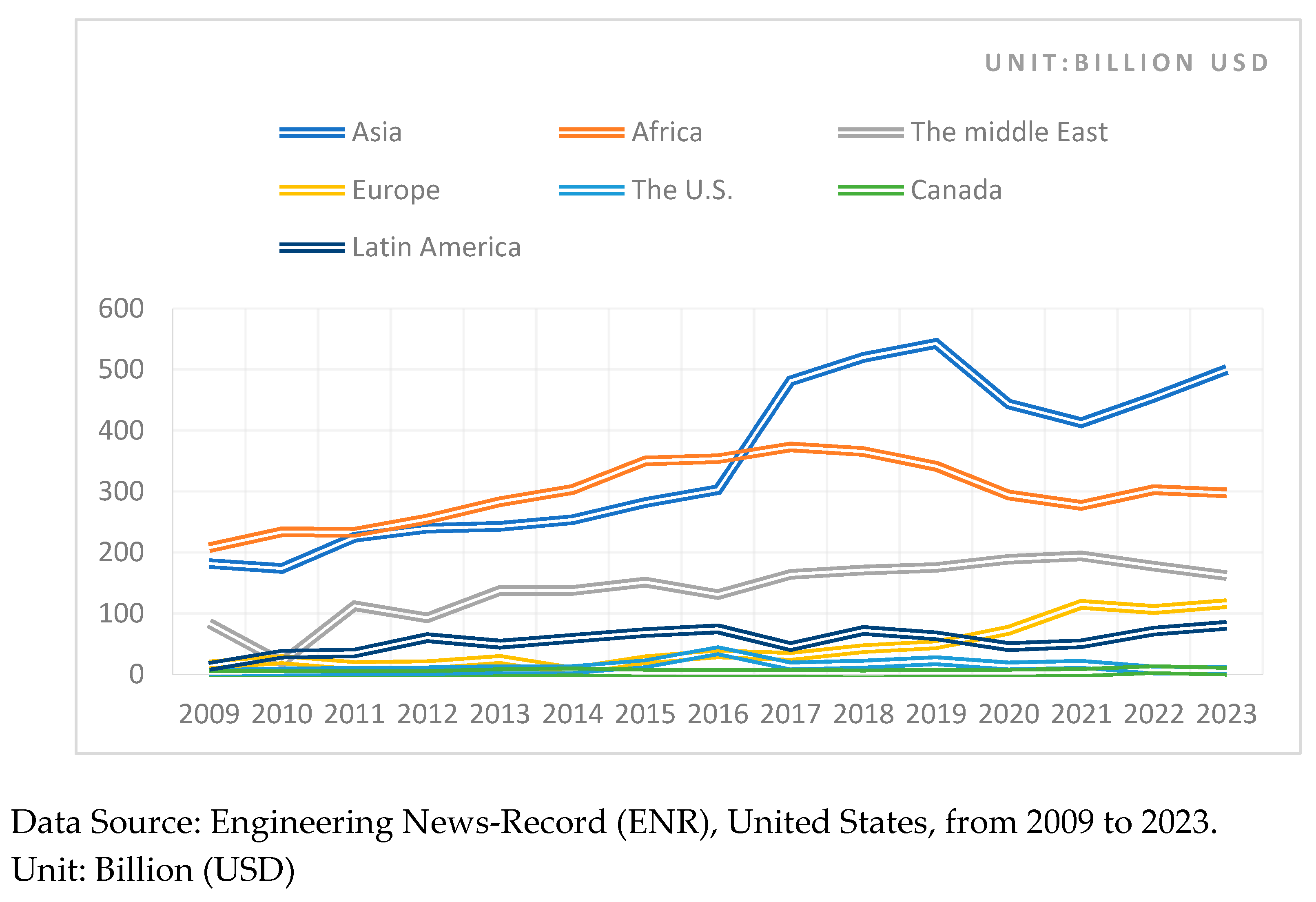

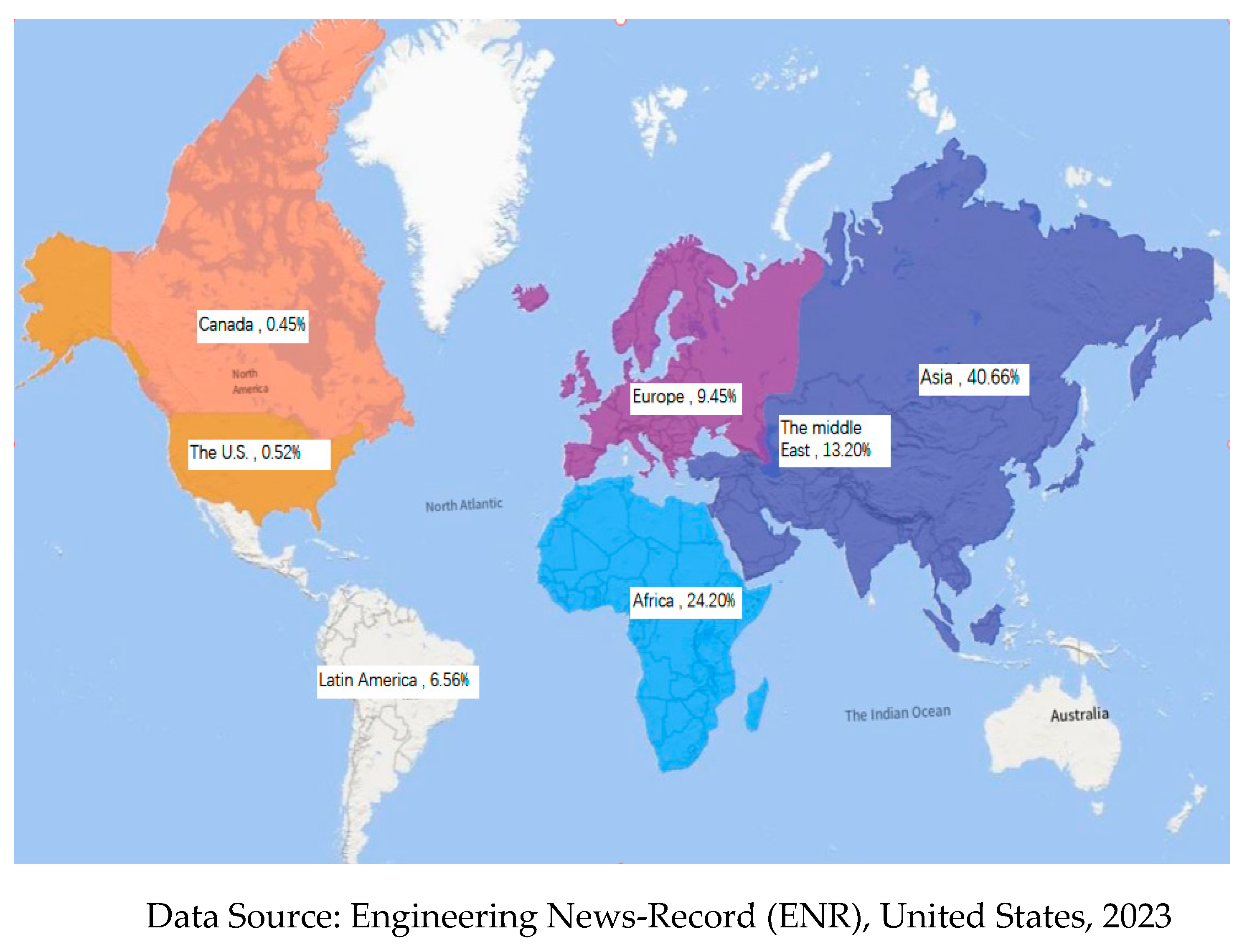

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Procurement Management in International Engineering EPC Projects

2.2. Supply Chain Integration Theory

2.3. The Advantages of Supply Chain Integration

2.4. The Necessity of Supply Chain Integration in Procurement Management for International EPC Projects

2.5. Stakeholder Management Theory

3. Methods

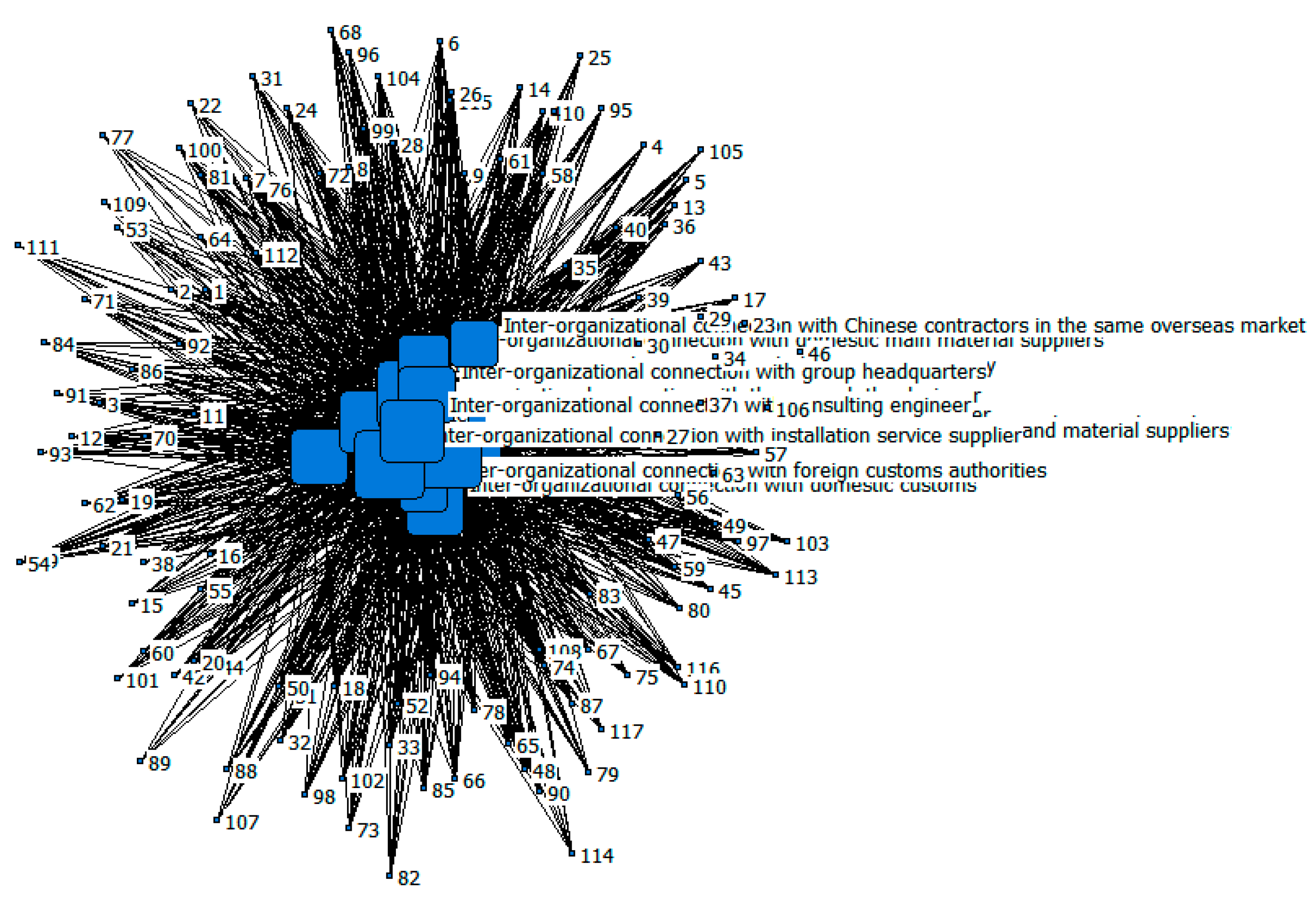

3.1. Inter-Organizational Stakeholder Relationships Analyzed Using Social Network Analysis

3.2. Case Studies

3.2.1. The EPC project for the Thái Bình Phase II boiler island in Vietnam

3.2.2. A Fijian renewable energy project

3.2.3. Zambian Energy Transmission and Transformation Project

- A flawless logistics management system is essential. To ensure the efficient transfer of equipment and materials to the project site, it is imperative to formulate targeted transportation management plans. In this project, all wires and tower materials are sourced domestically and meticulously packed into containers before export. This is a calculated action to protect the materials from possible damage or corrosion during transportation and to guarantee their arrival at the construction site in prime shape.

- Establishing a robust working partnership and managing the interface with foreign customs authorities are crucial.

- Cultivate a collaborative partnership with the logistics service provider.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BRI | Belt and Road Initiative |

| EPC | Engineering, Procurement, and Construction |

| SNA | Social Network Analysis |

| ENR | Engineering News Record |

| JIT | Just In Time |

References

- Huang, J.; Li, S.M. Adaptive strategies and sustainable innovations of Chinese contractors in the Belt and Road Initiative: A social network and supply chain integration perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fu, X.; Chen, X.; Wen, X. Supply Chain Management for the Engineering Procurement and Construction (EPC) Model: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16(22), 9748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, S.M. Data-Driven Analysis of Supply Chain Integration’s Impact on Procurement Performance in International EPC Projects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr T, Swink M. Revisiting the arcs of integration: Cross-validations and extensions. Journal of Operations Management, 2012, 30(1): 99-115.

- Sahin F, Robinson E P. Flow coordination and information sharing in supply chains: review, implications, and directions for future research. Decision sciences, 2002, 33(4): 505-536.

- Lau H S, Lau A H L. The newsstand problem: A capacitated multiple-product single-period inventory problem. European Journal of Operational Research, 1996, 94(1): 29-42.

- Lv Y, Shang Y. Investigation of industry 4.0 technologies mediating effect on the supply chain performance and supply chain management practices. Environmental Science & Pollution Research, 2023.

- Shin H, Collier D A, Wilson D D. Partnership-based supply chain collaboration: Impact on commitment, innovation, and firm performance. Journal of Business Logistics, 2019, 40(2): 137-152.

- Goldratt EM. Theory of Constraints. NewYork: North River Press, 1990.

- Dyer J H, Sing H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of management review, 1998, 23(4):660-679.

- Kaufmann L, Carter C R. International supply relationships and non-financial performance-a comparison of US and German practices. Journal of Operations Management, 2006, 24(5): 653-675.

- Tait, D. Make strong relationships a priority. Canadian Manager,1998, 23(1), 21-28.

- Blanchard D. Supply chain management best practices. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

- Mattessich PW, Johnson KM. Collaboration: What makes it work. St. Paul, MN: Fieldstone Alliance, 2018.

- Autry CW, Moon MA. Achieving supply chain integration: Connecting the supply chain inside and out for competitive advantage. Upper Saddle River, NJ: FT Press, 2016.

- Brinkhoff A, Özer Ö, Sargut G. All you need is trust? An examination of inter-organizational supply chain projects. Production and Operations Management, 2015, 24(2):181-200.

- Tong W, Jiang H, Hong W. Mode selection of the implementation and construction of projects on the comprehensive utilization of mineral resources: A feasibility study for higher education. Higher Education and Oriental Studies, 2021, 1(4).

- Stock G N, Greis N P, Kasarda J D. Logistics, strategy and structure: a conceptual framework. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 1998, 18(1): 37-52.

- Frohlich M T, Westbrook R. Arcs of integration: an international study of supply chain strategies. Journal of operations man-agement, 2001, 19(2):185-200.

- Leuschner R, Rogers D S, Charvet F F. A Meta-Analysis of Supply Chain Integration and Firm Performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 2013, 29(2): 32-56.

- Mackelprang A W, Robinson J L, Bernardes E, et al.The Relationship Between Strategic Supply Chain Integration and Performance: A Meta-Analytic Evaluation and Implications for Supply Chain Management Research. Journal of Business Logistics, 2014, 35(1):71-96.

- Titus S, Brochner J. Managing information flow in construction supply chains. Construction Innovation Information Process Management, 2005, 5(2):71-82.

- Gustin C M, Stank T P, Daugherty P J. Computerization: supporting integration. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 1994, 24(1): 11-16.

- Ellram L M, Cooper M C. The relationship between supply chain management and Keiretsu. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 1993, 4(1): 1-12.

- Byrne SM, Javad S. Integrated logistics information systems (ILIS): Competitive advantage or increased cost? //Annual Conference, Council of Logistics Management, 1992.

- Scott, B. Partnering in Europe: Incentive based alliancing for projects. London:Thomas Telford, 2001.

- Wood, A. Extending the supply chain: strengthening links with IT. Chemical Week, 1997, 159(25): 25-26.

- Olhager J, Selldin E. Enterprise resource planning survey of Swedish manufacturing firms. European Journal of Operational Re-search, 2003, 146(2):365-373.

- Bagchi P K, Chun Ha B, Skjoett-Larsen T, et al. Supply chain integration: a European survey. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 2005, 16(2): 275-294.

- Jap, S.D. Perspectives on joint competitive advantages in buyer-supplier relationships. International Journal of Research in Mar-keting, 2001, 18(1): 19-35.

- Vangen S, Huxham C. Enacting Leadership for Collaborative Advantage: Dilemmas of Ideology and Pragmatism in the Activities of Partnership Managers. British Journal of Management, 2003, 14(s1):S61-S76.

- Ralston PM, Blackhurst J, Cantor DE, Crum MR. A structure–conduct–performance perspective of how strategic supply chain integration affects firm performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 2015, 51(2):47-64.

- Min S, Roath A S, Daugherty P J, et al. Supply chain collaboration: what's happening?. The international journal of logistics management, 2005, 16(2): 237-256.

- Cao M, Zhang Q. Supply chain collaboration: Impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 2011, 29(3):163-180.

- Quinn Francis J. Reengineering the supply chain: An interview with Michael Hammer. Supply Chain Management Review, 1999, (1): 20-26.

- Whyte J, Stasis A, Lindkvist C. Managing change in the delivery of complex projects: Configuration management, asset information and ‘big data’. International Journal of Project Management, 2016, 34(2):339-351.

- Briscoe G, Dainty A. Construction supply chain integration: an elusive goal? Supply chain Management, 2005, 10(4):319-326.

- Tookey J E, Murray M, Hardcastle C, et al. Construction procurement routes: re-defining the contours of construction procurement. Engineering Construction & Architectural Management in Engineering, 1998, 14(5):73-78.

- De la Garza JM, Alcantara Jr P, Kapoor M, et al. Value of concurrent engineering for A/E/C industry. Journal of Management in Engineering, 1994, 10(3): 46-55.

- Demirkesen S, Ozorhon B. Measuring project management performance: Case of construction industry. Engineering Management Journal, 2017, 29(4): 258-277.

- Barlow, J. Innovation and learning in complex offshore construction projects. Research Policy, 2000, 29(7): 973-989.

- VrijhoefR, KoskelaL. Roles of supply chain management in construction. 7th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC-7), Berkeley, USA, 1999.

- Hugos, MH. Essentials of supply chain management. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2024.

- Love P E D, Davis P R, Chevis R, et al. Risk/reward compensation model for civil engineering infrastructure alliance projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 2011, 137(2): 127-136.

- Shokri S, Ahn S, Lee S, et al. Current Status of Interface Management in Construction: Drivers and Effects of Systematic Interface Management. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 2015: 04015070.

- Du L, Tang W, Liu C, Wang S, Wang T, Shen W, et al. Enhancing engineer–procure–construct project performance by partnering in international markets: Perspective from Chinese construction companies. International Journal of Project Management, 2016, 34(1):30-43.

- Amirtash P, Parchami Jalal M, Jelodar MB. Integration of project management services for International Engineering, Procurement and Construction projects. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 2021, 11(2):330-349.

- Jaccard J, BeckerM A. Statistics for the behavioral sciences.Melbourne:International Thomson Publishing Incorporated, 1997.

- Wang S, Tang W, Li Y. Relationship between owners' capabilities and project performance on development of hydropower projects in China. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 2013, 139(9): 1168-1178.

- Yeo K T, Ning J H. Managing uncertainty in major equipment procurement in engineering projects. European Journal of Operational Research, 2006, 171(1): 123-134.

- Kraljic, P. Purchasing Must Become Supply Management. Harvard Business Review, 1983, 61(5): 109-117.

- Shapiro R D. Get leverage from logistics. Harvard Business Review, 1984, 62(3): 118-126.

- Chopra S, Meindl P. Supply chain management: strategy, planning, and operation. Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2007. 3rd edition.

- Cooper MC, Lambert DM, Pagh JD. Supply chain management: more than a new name for logistics. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 1997, 8(1): 1-14.

- Mentzer J, DeWitt W, Keebler J, Soonhoong M, Nix N, Smith C, Zacharia Z. Defining supply chain management. Journal of Business Logistics, 2001, 22(1): 1-25.

- Chan A P C, Scott D, Lam E W M. Framework of success criteria for design/build projects. Journal of Management in Engineering, 2002, 18(3): 120-128.

- Chan A P C. Evaluation of enhanced design and build system-a case study of a hospital project. Construction Management & Economics, 2000, 18(7): 863-871.

- Come Zebra, E. I., van der Windt, H. J., Nhambiu, J. O. P., Golinucci, N., Gandiglio, M., Bianco, I., & Faaij, A. P. C. The integration of economic, environmental, and social aspects by developing and demonstrating an analytical framework that combines methods and indicators using Mavumira Village as a case study. Sustainability, 16(22). [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. , & Lee, D. A study on the rational decision-making process of vessel organization—Focusing on cases of vessel accidents. Sustainability, 16(22), 9820, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Petridi, A. , Fragkouli, D.-N., Mejias, L., Paredes, L., Bistue, M., Boukouvalas, C., Kekes, T., Krokida, M., & Papadaki, S. Assessing the overall sustainability performance of the meat processing industry before and after wastewater valorization interventions: A comparative analysis. Sustainability, 16(22), 9811, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Safaei, M. , Al Dawsari, S., & Yahya, K. Optimizing multi-channel green supply chain dynamics with renewable energy integration and emissions reduction. Sustainability, 16(22), 9710, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.F. Research on E-Procurement System Based on Supply Chain Management. Manag. Technol. SME 2019, 10, 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, D.; Liang, L.; Olson, D.L. Supply chain loss averse newsboy model with capital constraint. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2015, 46, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manik, D. Impact of supply chain integration on business performance: A review. J. Sist. Tek. Ind. 2022, 24, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, A.; Hallikas, J.; Immonen, M.; Lintukangas, K. The impact of procurement digitalization on supply chain resilience: Empirical evidence from Finland. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2023, 28, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, W.J. Construction Supply-Chain Management: A Vision for Advanced Coordination, Costing, and Control; NSF Berkeley-Stanford Construction Research Workshop: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Van Donk, D.P.; Van der Vaart, T. The different impact of inter-organizational and intra-organizational ICT on supply chain performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 803–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songer, A.D.; Molenaar, K.R. Project characteristics for successful public-sector design-build. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1997, 123, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.A. Sources of changes in design-build contracts for a governmental owner. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He Bosen. International Engineering Contracting (2nd Edition). China Construction Industry Press, 2007.

- Liu, Y. The impact of socio-cultural differences on the performance of overseas EPC project supply chain management. J. Chin. J. 2022.

- Lv, Y.; Shang, Y. Investigation of industry 4.0 technologies mediating effect on the supply chain performance and supply chain management practices. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 106129–106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, M.; Srinivasan, S.; Nandakumar, C.D. Optimal order quantity by maximizing expected utility for the newsboy model. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2019, 12, 410–424. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobotka, A.; Czarnigowska, A. Analysis of supply system models for planning construction project logistics. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2005, 11, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, J. Making Sense of Multivariate Data Analysis: An Intuitive Approach; Sage: London, UK, 2005.

- Chen, J.Y. Discussion on the measures for reducing “two financials” in EPC general contracting projects. Hydropower Stn. Des. 2024.

- Young, T.L. Successful Project Management; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wondirad, A.; Tolkach, D.; King, B. Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikjow, M.A.; Liang, L.; Sepasgozar, S. Engineering procurement construction in the context of Belt and Road infrastructure projects in West Asia: A SWOT analysis. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2021, 27, 04521001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespin-Mazet, F.; Ghauri, P. Co-development as a marketing strategy in the construction industry. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jergeas GF, Ruwanpura J. Why cost and schedule overruns on mega oil sands projects. Practice Periodical on Structural Design and Construction, 2009, 15(1): 40-43.

- Olander S, Landin A. Evaluation of stakeholder influence in the implementation of construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 2005, 23(4): 320-340.

- Yang J, Shen G Q, Ho M, et al. Stakeholder management in construction: An empirical study to address research gaps in previous studies. International Journal of Project Management, 2011, 29(7): 900-910.

- Kerzner, H. Project management best practices: Achieving global excellence. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

- Walker D H T, Bourne L M, Rowlinson S. Stakeholders and the supply chain. In: Walker D H T, Rowlinson S, eds. Procurement Systems: A Cross-industry Project Management Perspective. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis, pp. 70-100, 2008.

- Chinowsky PS, Diekmann J, O'Brien J. Project organizations as social networks. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 2009, 136(4): 452-458.

- Reed M S, Graves A, Dandy N, et al. Who's in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Management, 2009, 90(5): 1933-1949.

- Huang, J.; Fu, X. Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Digital Management (ICAIDM 2024). Advances in Intelligent Systems Research. ISBN 978-94-6463-578-2, ISSN 1951-6851. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Strategic Evolution and Adaptive Responses of Chinese International General Contractors under the Belt and Road Initiative: Insights from Social Network Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Digital Economy and Computer Science (DECS 2024), September 20–22, 2024, Xiamen, China. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 6 pages. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fu, X., "Advanced Procurement Management Strategies for International Energy and Power Engineering Projects: A Supply Chain Integration Perspective," 2024 4th International Conference on Energy, Power and Electrical Engineering (EPEE), Wuhan, China, 2024, pp. 1075-1081. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., & Fu, X. "Advanced Procurement Management Strategies for International Energy and Power Engineering Projects: A Supply Chain Integration Perspective," Proceedings of the 2024 6th Management Science Informatization and Economic Innovation Development Conference (MSIEID 2024), Guangzhou, China, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Stakeholder | Intermediate centrality | Ranking |

| Inter-organizational connection with the construction party | 623.777 | 1 |

| Inter-organizational connection with installation service supplier | 616.684 | 2 |

| Inter-organizational connection with logistic service provider | 579.404 | 3 |

| Inter-organizational connection with the owner | 565.026 | 4 |

| Inter-organizational connection with domestic equipment and material suppliers | 553.198 | 5 |

| Inter-organizational connection with consulting engineer | 551.606 | 6 |

| Inter-organizational connection with group headquarters | 512.523 | 7 |

| Inter-organizational connection with domestic customs | 502.360 | 8 |

| Inter-organizational connection with foreign main material suppliers | 487.756 | 9 |

| Inter-organizational connection with domestic main material suppliers | 449.98 | 10 |

| Inter-organizational connection with the designer | 421.677 | 11 |

| Inter-organizational connection with foreign equipment and material suppliers | 411.496 | 12 |

| Inter-organizational connection with Chinese contractors in the same overseas market | 396.808 | 13 |

| Inter-organizational connection with foreign customs authorities | 393.705 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).