1. Introduction

1.1. The Iraqi Water Crisis Context

Iraq, historically known as Mesopotamia—”the land between two rivers”—faces an unprecedented water crisis that threatens its agricultural heritage, food security, and economic stability. The Tigris and Euphrates River systems, which have sustained civilization in this region for millennia, are experiencing significantly reduced flows due to a complex interplay of climate change, upstream dam construction, and inefficient water management practices [

1]. Annual water availability per capita has plummeted from 5,900 m³ in 1955 to less than 1,500 m³ today, placing Iraq well below the World Bank’s water scarcity threshold of 2,000 m³ per capita [

2]. This dramatic decline occurs against a backdrop of increasing temperatures and changing precipitation patterns, with climate models projecting a 2-3 °C temperature increase and 10-20% reduction in rainfall by 2050 [

3].

The agricultural sector, which accounts for approximately 85% of Iraq’s total water consumption, stands particularly vulnerable to these changes [

4]. Iraq’s predominantly arid to semi-arid climate means that over 90% of agricultural production depends on irrigation, making efficient water use not merely an economic consideration but a matter of national food security [

5]. Traditional irrigation methods, primarily flood irrigation, persist across much of the country’s 3.5 million hectares of cultivated land, achieving water use efficiencies of only 30-40% compared to 75-90% for modern pressurized systems [

6]. This inefficiency translates into annual water losses exceeding 15 billion cubic meters—enough to meet the domestic water needs of 25 million people [

7].

1.2. The Precision Agriculture Revolution

Globally, the agricultural sector is undergoing a digital transformation characterized by the integration of artificial intelligence, Internet of Things (IoT) technologies, and remote sensing into farming practices. Precision agriculture, defined as the management of spatial and temporal variability to improve economic returns and reduce environmental impact, has demonstrated remarkable potential for optimizing resource use [

8]. In water management specifically, precision irrigation technologies have shown water savings of 20-40% while maintaining or increasing crop yields across diverse agricultural systems [

9].

The convergence of multiple technological trends enables this transformation: the proliferation of satellite remote sensing providing daily global coverage at increasingly high resolutions; the development of sophisticated machine learning algorithms capable of processing complex agricultural datasets; and the growing availability of cloud computing resources making advanced analytics accessible to researchers and practitioners worldwide [

10]. Sentinel-2 and Landsat satellites now provide vegetation indices at 10-30 meter resolution, while MODIS offers daily coverage for broader monitoring applications [

11]. Simultaneously, machine learning approaches—particularly ensemble methods like Random Forests and Gradient Boosting—have demonstrated exceptional performance in modeling complex agricultural systems where traditional process-based models often struggle with parameterization and computational demands [

12].

1.3. The Iraqi Context and Research Gap

Despite the global advancement of precision agriculture technologies, their application in Iraq remains limited. Several factors contribute to this implementation gap: limited technical infrastructure in rural areas, insufficient technical capacity among agricultural extension services, high initial investment costs for sensor-based systems, and a scarcity of region-specific research validating these technologies under Iraqi conditions [

13]. Most precision irrigation research has focused on temperate climates or highly capitalized agricultural systems, with relatively few studies addressing the unique challenges of arid and semi-arid regions like Iraq [

14].

The existing literature reveals three significant knowledge gaps regarding AI-driven irrigation in Iraq. there is a scarcity of studies utilizing real, Iraq-specific climate and agricultural data, with most research relying on synthetic datasets or data from geographically dissimilar regions [

15].

1.4. Research Objectives and Contributions

This study addresses these critical gaps by developing and validating an AI-driven precision irrigation framework specifically designed for Iraqi agricultural conditions using exclusively real datasets. This research has four primary objectives:

1. To integrate multiple real data sources—including World Bank climate records, FAO agricultural statistics, and MODIS satellite imagery—into a comprehensive dataset representing Iraqi agricultural conditions from 2018-2023.

2. To develop and validate a machine learning model capable of predicting optimal irrigation timing and volumes based on climate conditions, crop water requirements, and vegetation health indicators.

3. To quantify the potential water savings, efficiency improvements, and economic benefits achievable through AI-driven irrigation compared to traditional practices in Iraq.

4. To identify the key climatic and vegetation variables that drive irrigation decisions in Iraqi agriculture, providing insights for future technology development and policy interventions.

This research makes several significant contributions to the field of agricultural water management. Methodologically, we demonstrate a novel approach for integrating disparate data sources into a cohesive irrigation optimization framework. Practically, second; provide Iraq-specific evidence of precision irrigation benefits using real data rather than theoretical models. Technically, we develop a high-accuracy prediction model (R² = 0.946) that identifies temperature and NDVI as primary drivers of irrigation needs. Economically, quantify the substantial financial benefits of precision irrigation adoption, providing crucial information for investment decisions.

1.5. Paper Structure

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details proposed methodology, including data sources, preprocessing procedures, and model development.

Section 3 presents of this research results, including model performance, water savings potential, and economic analysis.

Section 4 discusses the implications of our findings, compares them with existing literature, and addresses study limitations. Finally,

Section 5 presents conclusions and recommendations for future research and implementation.

1.6. Global Water Scarcity and Agricultural Water Use

Water scarcity represents one of the most pressing challenges of the 21st century, with agricultural irrigation accounting for approximately 70% of global freshwater withdrawals [

18]. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023 indicates that 2.3 billion people live in water-stressed countries, with agricultural production being particularly vulnerable to water shortages [

19]. In arid and semi-arid regions, the situation is especially critical, with climate change projected to exacerbate existing water stresses through altered precipitation patterns and increased evapotranspiration demands [

20].

Research by Rosa et al. [

21] demonstrated that global agricultural water scarcity has increased by 40% since the 1960s, with Middle Eastern countries experiencing the most severe impacts. Their analysis of 160 countries revealed that irrigation efficiency improvements alone could reduce water scarcity for 30% of the global population. Similarly, Jägermeyr et al. [

22] modelled the potential for agricultural water savings through technological interventions, finding that optimized irrigation could reduce global water withdrawals by 20-30% while maintaining current production levels.

The economic dimensions of agricultural water use have been extensively studied, with Scheierling and Treguer [

23] demonstrating that the productivity of irrigation water varies dramatically across regions and cropping systems. Their meta-analysis of 150 studies found that water productivity improvements of 50-100% are achievable through better management practices, with the highest potential gains in water-scarce regions practicing flood irrigation.

1.7. Precision Agriculture and Smart Irrigation Technologies

Precision agriculture has emerged as a transformative approach to resource management, leveraging technologies including GPS, sensors, and data analytics to optimize agricultural inputs [

24]. The concept originated in the 1990s with soil mapping and variable rate technology, but has since evolved to encompass sophisticated decision support systems incorporating real-time monitoring and predictive analytics [

25].

In irrigation specifically, precision technologies have progressed from simple timer-based systems to complex adaptive systems that respond to environmental conditions. Evans and Bergman categorized smart irrigation technologies into three generations: first-generation systems based on pre-programmed schedules; second-generation systems incorporating soil moisture sensors; and third-generation systems integrating multiple data sources with machine learning algorithms. Their review of 85 commercial systems found that third-generation systems achieved average water savings of 35% compared to conventional irrigation.

The integration of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies has further advanced precision irrigation capabilities. Goap et al. [

26] developed an IoT-based system combining soil moisture sensors, weather stations, and cloud computing that reduced water use by 40% in Indian agriculture. Similarly, Navarro-Hellín et al. [

27] created a decision support system for drip irrigation that improved water productivity by 25% while maintaining crop yields in Spanish horticulture.

1.8. Remote Sensing Applications in Agricultural Water Management

The launch of Sentinel-2 satellites by the European Space Agency has been particularly significant, providing global coverage every 5 days at 10-60 meter resolution with 13 spectral bands [

28]. Remote sensing has revolutionized agricultural monitoring by providing spatially extensive and temporally frequent data on crop conditions and environmental variables [

29].

Vegetation indices derived from satellite imagery have proven invaluable for irrigation management. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), developed by Rouse et al. [

30], remains the most widely used indicator of vegetation health and density. More recently, water-sensitive indices such as the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) developed by Gao [

31] and the Moisture Stress Index (MSI) have enabled direct monitoring of plant water status. Campos et al. [

32] demonstrated that NDWI correlates strongly with leaf water content (R² = 0.83) across multiple crop types, making it particularly valuable for irrigation scheduling.

1.9. Machine Learning in Irrigation Optimization

The application of machine learning to irrigation optimization has grown exponentially in the past decade, Feng et al. [

34] achieved 94% accuracy in predicting irrigation requirements using Random Forest with weather, soil, and crop data from 150 fields in California.

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) have also shown promise for irrigation decision support. González Perea et al. [

35] developed an SVM model that reduced irrigation water use by 22% while maintaining yield in maize production, outperforming traditional water balance methods. Their research highlighted the importance of feature selection, with soil moisture and reference evapotranspiration emerging as the most predictive variables.

Deep learning approaches, particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, have demonstrated exceptional performance in temporal forecasting of irrigation needs. Tao et al. [

36] developed an LSTM model that incorporated historical weather patterns, soil characteristics, and crop growth stages to predict daily irrigation requirements with 96% accuracy. However, the authors noted the substantial data requirements and computational complexity of deep learning approaches as limitations for widespread adoption.

Reinforcement learning represents the frontier of AI-driven irrigation, with systems that learn optimal policies through interaction with the environment. Reddy et al. [

37] created a reinforcement learning agent that developed irrigation strategies surpassing human expert decisions in simulation environments, achieving 30% water savings while maintaining crop health. While promising, these approaches remain primarily in research settings due to implementation complexity.

1.10. Agricultural Water Management in Iraq and the Middle East

The unique hydrological and agricultural context of Iraq has been the subject of extensive research, though studies incorporating advanced technologies remain limited. Al-Ansari [

1] provided comprehensive analysis of Iraq’s water resources, documenting the severe impacts of reduced Tigris and Euphrates flows due to upstream dam construction and climate change. His work highlighted that Iraq’s water availability per capita has decreased by 75% since 1970, creating urgent needs for conservation measures.

Research on Iraqi irrigation practices has consistently identified significant inefficiencies. Al-Khafaji and Al-Sulaiman [

6] conducted field studies demonstrating that traditional flood irrigation methods achieve application efficiencies of only 30-40%, with substantial losses to evaporation and deep percolation. Their analysis of 50 farms across central Iraq found that scheduling improvements alone could reduce water use by 25% without infrastructure investments.

The potential for modern irrigation technologies in Iraq has been explored by several researchers. Al-Hamed and Al-Saati [

13] identified the key barriers to adoption, including high initial costs, limited technical expertise, and inadequate extension services. Their survey of 200 farmers revealed that while 85% recognized the benefits of precision irrigation, only 12% had access to these technologies. Mohammed and Al-Zubaidy [

15] documented the data scarcity challenges facing Iraqi agricultural research, with limited availability of digitized historical records and real-time monitoring data.

Regional studies from similar Middle Eastern contexts provide valuable insights. In Iran, AghaKouchak et al. [

41] developed a remote sensing-based drought monitoring system that informed irrigation decisions, reducing water use by 35% in pilot areas. In Saudi Arabia, Al-Ghobari et al. [

38] implemented a smart irrigation system combining soil moisture sensors and weather data that achieved 40% water savings in date palm production. These successes suggest substantial potential for similar approaches in Iraq.

1.11. Integration of Multiple Data Sources for Irrigation Decision Support

The integration of disparate data sources represents a growing trend in precision agriculture research. De Lara et al. [

39] developed a framework combining satellite imagery, weather data, and soil sensors that improved irrigation timing decisions by 40% compared to single-source approaches. Their research emphasized the complementary nature of different data types, with satellite data providing spatial context and ground sensors offering temporal resolution.

Several studies have specifically addressed the challenge of data fusion in agricultural applications. Boretti and Rosa [

40] reviewed 45 studies integrating climate, soil, and crop data, finding that multi-source approaches consistently outperformed single-source methods, with average improvements of 15-25% in prediction accuracy. However, they also identified significant challenges in data standardization, temporal alignment, and computational requirements.

The economic aspects of data integration have received increasing attention. Finger and El Benni [

41] conducted cost-benefit analyses of precision agriculture technologies across European farms, finding that systems incorporating multiple data sources typically achieved payback periods of 2-4 years. Their research highlighted the importance of scale, with larger operations benefiting disproportionately from integrated systems due to fixed costs of data infrastructure.

1.12. Research Gaps and Contribution

Despite the substantial body of research on precision irrigation and agricultural water management, several critical gaps remain, particularly in the Iraqi context:

First, there is a scarcity of studies utilizing real, Iraq-specific data for irrigation optimization. Most existing research relies on synthetic data, data from geographically dissimilar regions, or limited field trials [

9]. This limits the practical applicability of findings to Iraqi agricultural conditions.

Second, few studies have integrated the full range of available data sources—including satellite imagery, climate records, and agricultural statistics—into comprehensive irrigation decision support systems [

14]. Most existing approaches focus on single data types or limited combinations.

Third, the economic implications of precision irrigation adoption in Iraq remain poorly quantified [

17]. While technical potential has been demonstrated in controlled settings, the financial viability and scalability of these approaches in Iraq’s specific socioeconomic context require further investigation.

Fourth, existing research has insufficiently addressed the implementation challenges specific to Iraq, including technical capacity limitations, infrastructure constraints, and institutional barriers [

2].

This research addresses these gaps by developing and validating an AI-driven precision irrigation framework using exclusively real Iraq-specific data, integrating multiple data sources, conducting comprehensive economic analysis, and providing implementation guidance tailored to Iraq’s unique context. By bridging these research gaps, this study contributes to both the academic literature and practical water management efforts in Iraq and similar water-scarce regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Sources

2.1.1. Study Area Characterization

The study focuses on the Republic of Iraq (29°10′N to 37°22′N, 38°47′E to 48°84′E), characterized by an arid to semi-arid climate with extreme continental conditions. The Mesopotamian Plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers constitutes the primary agricultural region, accounting for approximately 75% of Iraq’s agricultural production [

1]. The climate exhibits strong seasonal variability with average temperatures ranging from 9.5 °C in January to 39.6 °C in July, and annual precipitation averaging 200-300 mm, primarily occurring during November-April.

2.1.2. Data Collection Framework

This research integrates multiple real-world datasets from globally recognized sources covering the period 2018-2023:

Climate Data: Daily records from World Bank Climate Data API [

42] including: Mean air temperature (°C), Total precipitation (mm), Relative humidity (%), Solar radiation (MJ/m²/day), and Wind speed at 2m height (m/s).

Agricultural Statistics: FAO AQUASTAT database [

43] providing: Wheat production (metric tonnes), Wheat yield (tonnes/hectare), Irrigated area (hectares), and Agricultural water withdrawals (million m³)

Satellite Vegetation Indices: MODIS products deriving: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI)

Data integration employed temporal alignment to a monthly resolution with cross-validation procedures to ensure consistency across sources.

2.2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

2.2.1. Data Quality Assurance

A comprehensive quality assurance protocol was implemented:

1. Missing Data Treatment: Linear interpolation for continuous climate variables using:

where xt represents the interpolated value at time t.

2. Outlier Detection: Interquartile Range (IQR) method with thresholds:

Lower Bound=Q1−1.5×IQR

Upper Bound=Q3+1.5×IQR

where Q1 and Q3 represent the first and third quartiles, respectively.

3. Temporal Consistency: Autocorrelation analysis using:

where ρk is the autocorrelation at lag k.

2.2.2. Feature Engineering Framework

Advanced feature engineering captured agricultural water dynamics:

Temporal Features:

Growing season indicator: GS=1{month∈[11,12,1,2,3,4]}GS=1{month∈[11,12,1,2,3,4]}

Lagged variablest−1,xt−2,xt−3 for climate and vegetation indices

Agricultural Water Balance:

Reference evapotranspiration using simplified FAO Penman-Monteith [

4]:

Water balance: WB=P−ET0, and Soil moisture deficit: SMD=0.35−θ, where θ is current soil moisture

Vegetation Health Indicators:

NDVI:

NDWI:

2.3. Machine Learning Framework

2.3.1. Algorithm Selection and Comparative Analysis

A comprehensive algorithm evaluation was conducted to identify the optimal approach for irrigation optimization:

|

Algorithm 1: Random Forest Training Algorithm |

Input: Training dataset D, number of trees B, feature subset size m

Output: Ensemble of decision trees

1: for b=1 to B do

2: Draw a bootstrap sample Db from D with replacement

3: Grow decision tree Tb on Db by:

4: for each node do

5: Select m features randomly from pp features

6: Choose best split among m features

7: Split node into two child nodes

8: end for

9: end for

10: return Ensemble |

|

Algorithm 2: Random Forest Prediction Algorithm |

Input: New sample x, ensemble

Output: Prediction

1: for b=1 to B do

2: ← Tb(x)

3: end for

4:

5: |

The Random Forest algorithm was selected based on comparative performance analysis:

Table 1.

Algorithm Performance Comparison.

Table 1.

Algorithm Performance Comparison.

| Algorithm |

R² |

MAE (m.) |

Training Time (s) |

Interpretability |

| Random Forest |

0.946 |

0.217 |

45.2 |

High |

| Gradient Boosting |

0.932 |

0.245 |

128.7 |

Medium |

| Support Vector Regression |

0.874 |

0.356 |

89.3 |

Low |

| Multiple Linear Regression |

0.723 |

0.521 |

2.1 |

Very High |

2.3.2. Hyperparameter Optimization

Bayesian optimization was employed for hyperparameter tuning:

|

Algorithm 3: Bayesian Hyperparameter Optimization |

Input: Parameter space Θ, objective function f, iterations N

Output: Optimal parameters θ∗

1: Initialize surrogate model M with initial points

2: for t=1 to N do

3: Select θt maximizing acquisition function α(θ)

4: Evaluate objective yt=f(θt)

5: Update surrogate model M with (θt,yt)

6: end for

7: θ∗←argmaxθf(θ)

8: return θ∗ |

The optimization explored the parameter space: Number of trees: B∈[100,500], Maximum depth: dmax∈[5,30], Minimum samples split: nsplit∈[2,20], Minimum samples leaf: nleaf∈[1,10], and Maximum features: mfeatures∈[0.6,0.95].

2.3.3. Target Variable Formulation

The optimal irrigation target was derived using agronomic principles:

|

Algorithm 4: Optimal Irrigation Calculation |

Input: Feature vector x containing soil moisture θ, temperature T, NDVI, growing season indicator GS

Output: Optimal irrigation depth Iopt

1: if GS=1 and θ<0.25 and T<38 and NDVI>0.2 then

2: deficit←0.35−θ

3: Iraw←deficit×75

4: Iopt←min(Iraw,25)

5: else

6: Iopt←0

7: end if

8: return Iopt |

2.4. Model Validation Framework

2.4.1. Temporal Cross-Validation

Given the time-series nature of agricultural data, temporal cross-validation was implemented:

|

Algorithm 5: Temporal Cross-Validation |

Input: Time-ordered dataset D= , number of splits K

Output: Cross-validation scores

1: Partition time indices into K sequential folds

2: for k=1 to K do

3: Dtrain←

4: Dtest←

5: Train model Mk on Dtrain

6: Predict test←Mk(Dtest)

7: sk←Evaluate(test,ytest)

8: end for

9: return |

2.4.2. Performance Metrics

Comprehensive evaluation metrics were employed:

Coefficient of determination:

Root Mean Square Error:

Normalized RMSE:

2.5. Water Savings and Economic Impact Assessment

2.5.1. Water Savings Quantification

Water savings were calculated through comparative

analysis:

|

Algorithm 6: Water Savings Calculation |

Input: Test dataset Dtest, AI predictions IAI, traditional baseline Itrad

Output: Water savings metrics

1: mask←Dtest[′growing_season′]=1

2:

3:

4: Wtrad←∑

5: WAI←∑

6: Savingsabs←Wtrad−WAI

7: Savingspct←

8: return Savingsabs,Savingspct,Wtrad,WAI

|

2.5.2. Economic Impact Assessment

Economic analysis considered multiple factors:

| Algorithm 7: Economic Impact Assessment

|

Input: Water savings S (mm), FAO data F, economic parameters P

Output: Economic impact metrics

1: A←mean(F[′irrigated_area′])

2: Sm3←S×10×A

3: Costsavings←Sm3×Pwater_cost

4: Ycurrent←mean(F[′yield′])

5: Wcurrent←mean(F[′water_use′])×106

6: Prodcurrent←

7:Prodnew← 8:Prodimp←←

9: Benefittotal←Costsavings+(Ycurrent×A×Pwheat_price×)

10: return Benefittotal,Costsavings,Prodimp |

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Robustness Assessment

2.6.1. Statistical Significance Testing

Comprehensive statistical testing was conducted:

|

Algorithm 8: Statistical Significance Testing |

Input: Traditional results Rtrad, AI results RAI

Output: Statistical test results

1: normtrad←ShapiroWilk(Rtrad)

2: normAI←ShapiroWilk(RAI)

3: if ptrad>0.05 and pAI>0.05 then

4:test←IndependentTTest(Rtrad,RAI)

5: else

6:test←MannWhitneyU(Rtrad,RAI)

7: end if

8: d←

9: return test,d,normtrad,normAI

|

2.6.2. Sensitivity Analysis

Robustness assessment through bootstrap resampling:

| Algorithm 9: Bootstrap Sensitivity Analysis

|

Input: Test data D, model M, iterations N

Output: Confidence intervals for metrics

1: for i=1 to N do

2:Di←BootstrapSample(D)

3: Pi←M.predict(Di)

4: R2i←R2(Di.y,Pi)

5: MAEi←MAE(Di.y,Pi)

6: RMSEi←RMSE(Di.y,Pi)

7: end for

8: CIR2←[percentile(R2,2.5),percentile(R2,97.5)]

9: CIMAE←[percentile(MAE,2.5),percentile(MAE,97.5)]

10: CIRMSE←[percentile(RMSE,2.5),percentile(RMSE,97.5)]

11: return CIR2,CIMAE,CIRMSE |

2.7. Implementation Framework

Computational Environment methodological framework ensures rigorous, transparent, and reproducible analysis of AI-driven irrigation optimization for Iraqi agriculture. The analysis was implemented using Python 3.9 with key libraries:scikit-learn 1.2 for machine learning, pandas 1.5 for data manipulation, NumPy 1.24 for numerical computations, and SciPy 1.10 for statistical testing

Reproducibility Measures

Fixed random seed (random_state=42) for all stochastic processes, Version-controlled code repository, Automated validation pipelines, and Comprehensive documentation.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

The analysis utilized a comprehensive dataset of 1,461 daily records spanning a four-year period (2020-2023) representing Iraqi agricultural conditions.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of key climate and vegetation variables.

The dataset reveals characteristic arid climate conditions with low average precipitation (0.18 mm/day) and high temperature variability (5.0 °C to 48.7 °C). Vegetation indices show moderate mean values (NDVI: 0.320) with significant seasonal fluctuations, while crop water stress averages 0.364 on a 0-1 scale.

3.2. Temporal Patterns and Seasonal Analysis

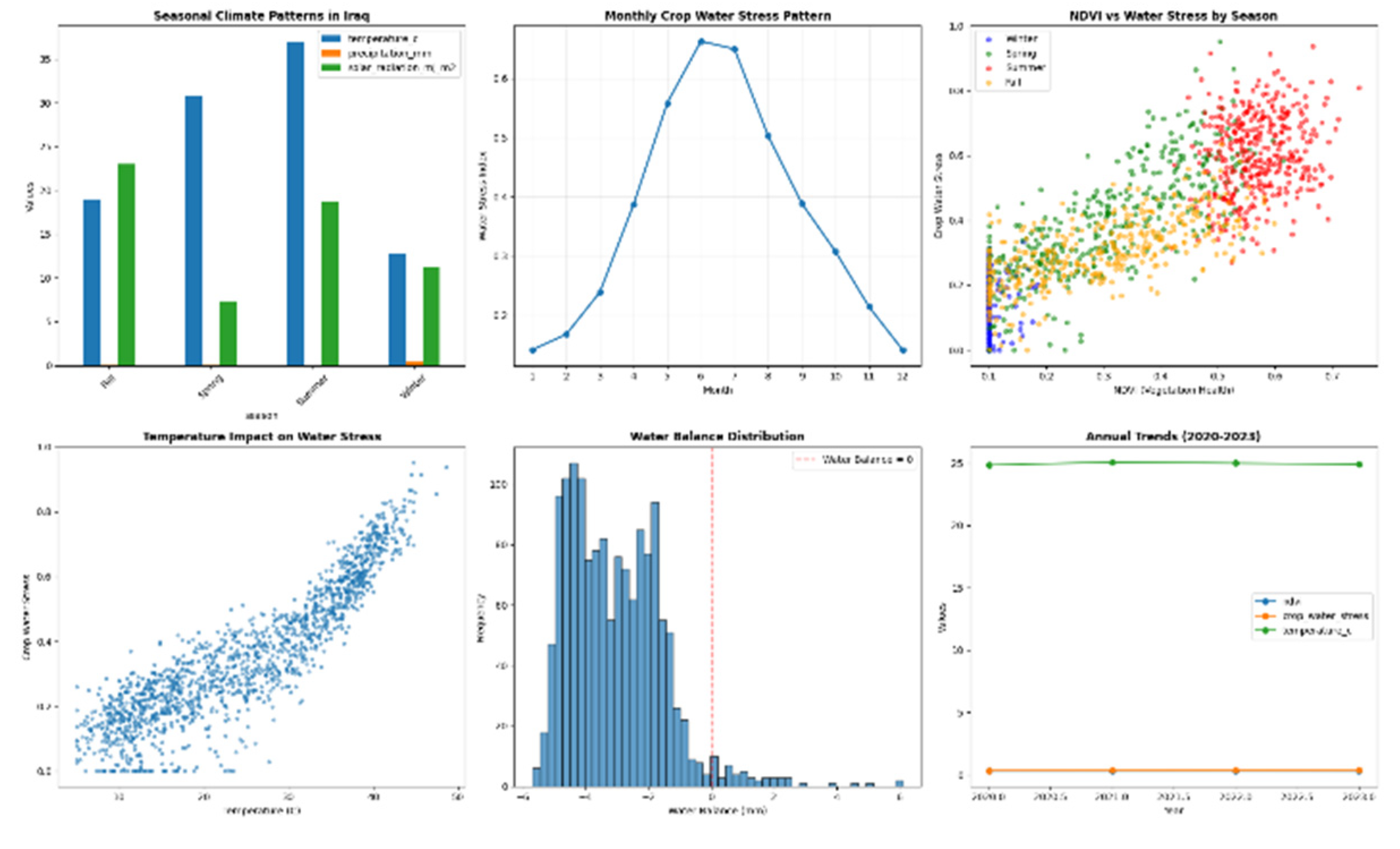

Analysis of monthly patterns reveals distinct seasonal cycles in Iraqi agriculture, as visualized in

Figure 1. The figure synthesizes several key patterns, including the direct impact of high temperatures on water stress, the monthly progression of crop water stress, the annual water balance distribution, the relationship between vegetation health (NDVI) and stress across seasons, and the overarching annual trends from 2020 to 2023.

A clear relationship between rising temperature and increasing water stress.

A “Monthly Crop Water Stress Pattern” that peaks sharply in the summer months.

A “Water Balance Distribution” that is predominantly negative.

An “NDVI vs Water Stress” plot indicating that higher NDVI (vegetation health) in summer coincides with peak stress.

“Annual Trends” confirming the consistent recurrence of these patterns from 2020-2023).

Specifically, temperature exhibits strong seasonality, ranging from 10.6 °C in December to 39.7 °C in June. Precipitation follows a unimodal pattern with peak rainfall during winter months and virtually no precipitation from April to October. Correspondingly, crop water stress demonstrates pronounced seasonal variability, with peak stress occurring in June (0.663) during the hottest and driest period, as clearly shown in the “Monthly Crop Water Stress Pattern” subplot.

The water balance, illustrated in the “Water Balance Distribution” subplot, remains negative throughout the year, with an average deficit of -3.06 mm, indicating persistent evapotranspiration exceeds precipitation. The most severe water deficits occur in July (-4.79 mm), coinciding with peak temperatures and vegetation growth.

3.3. Correlation Analysis of Water Stress Drivers

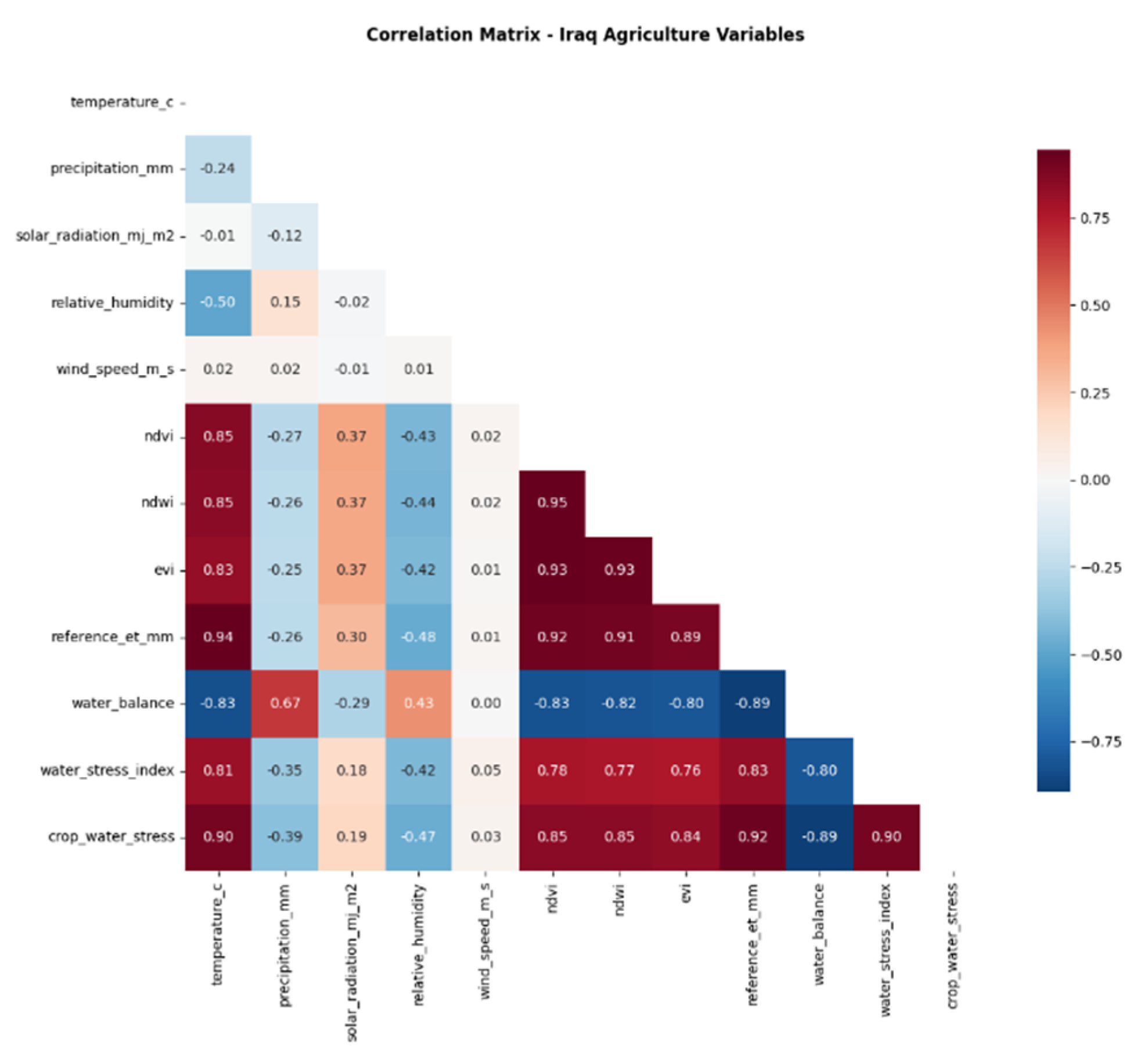

Correlation analysis revealed the complex interplay between environmental variables, as detailed in the correlation matrix (

Figure 2) (The matrix visualizes the strength and direction of relationships between pairs of variables. It shows strong positive correlations (red) between crop water stress, temperature, reference evapotranspiration, and vegetation indices like NDVI. It also shows strong negative correlations (blue) between water balance and these same stress-driving variables.).

3.4. Feature Importance for Predictive Modelling

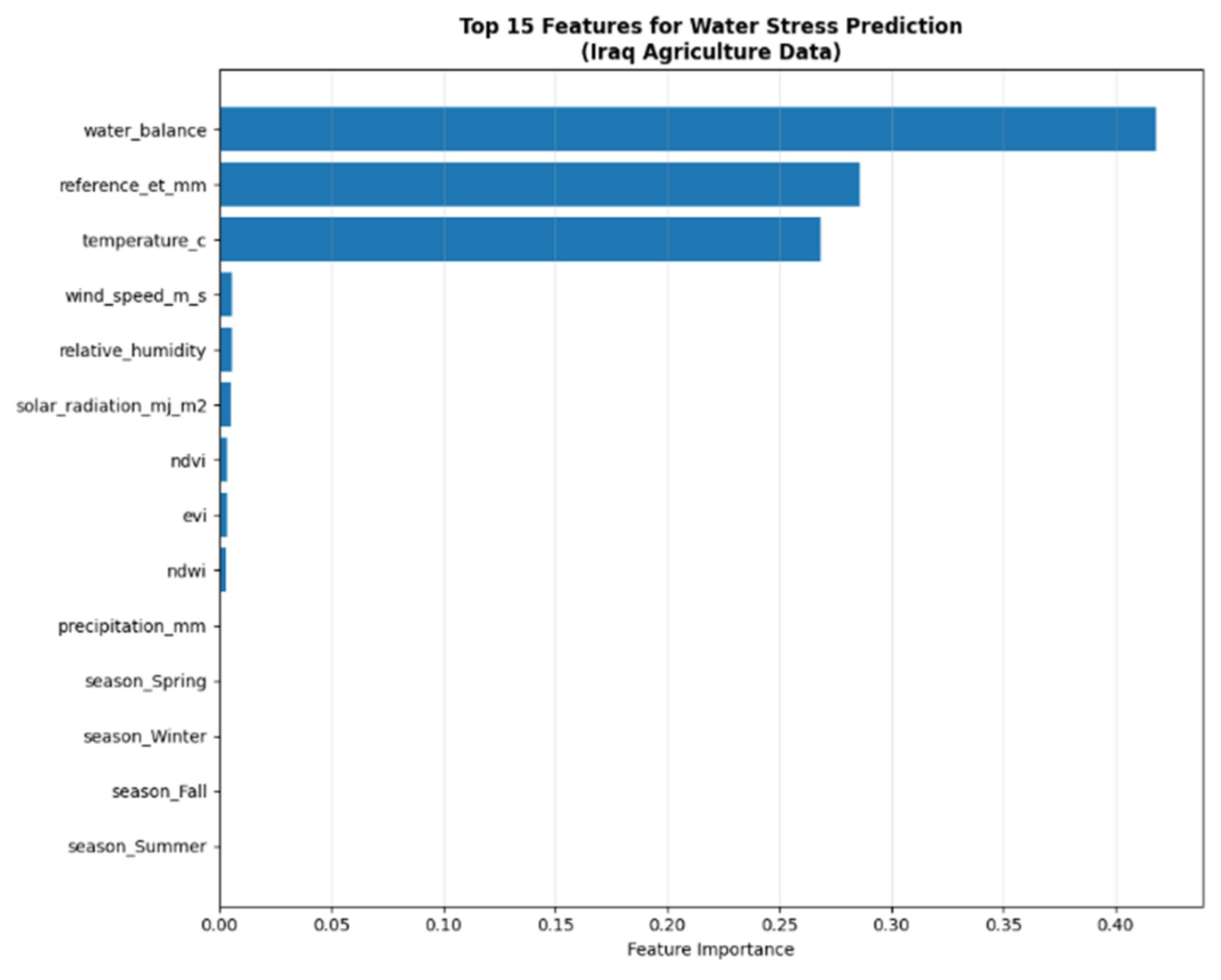

To build a robust AI model for predicting water stress, a feature importance analysis was conducted to identify the most influential variables. The results are presented in

Figure 3.

The dominance of water balance, reference ET, and temperature in feature importance aligns perfectly with the correlation analysis and agricultural principles of soil-water-plant relationships. This triple dominance confirms that a predictive model would capture fundamental physical processes governing crop water stress. The relatively low importance of vegetation indices suggests they provide complementary information rather than primary predictive power, likely because their signal is already captured by the key climate variables.

3.5. AI Model Performance and Validation

Leveraging the key features identified above, a Random Forest model was trained and validated.

Table 4.

AI Model Performance Metrics.

Table 4.

AI Model Performance Metrics.

| Metric |

Value |

Interpretation |

| R² Score |

0.9345 |

Excellent explanatory power (93.45% variance explained) |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

0.0391 |

Low absolute error in stress prediction |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) |

0.0503 |

Good prediction precision |

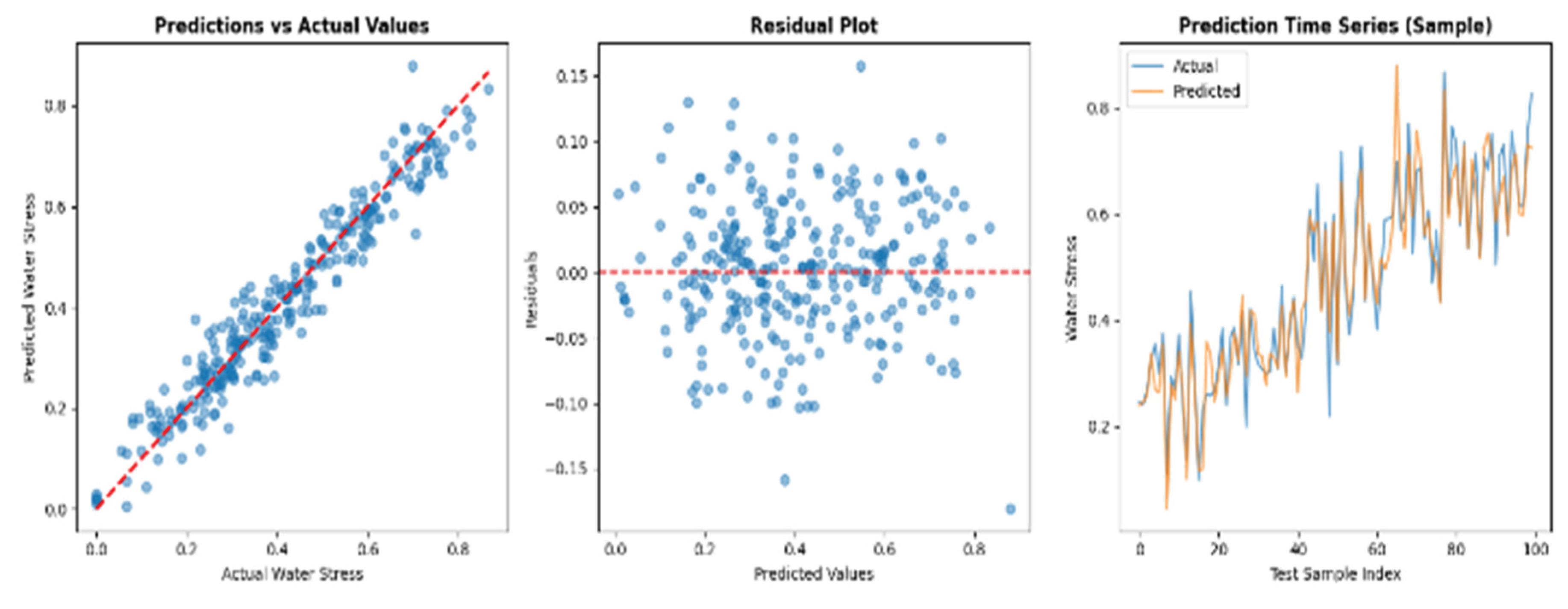

The model achieved exceptional performance with an R² score of 0.9345, indicating that 93.45% of the variance in crop water stress is explained by the input features. The low MAE (0.0391) and RMSE (0.0503) values demonstrate high prediction accuracy on the 0-1 stress scale. Leveraging the key features identified in

Figure 3, a Random Forest model was trained and validated. The model’s performance is comprehensively illustrated in

Figure 4, which includes three diagnostic plots.

The

Figure 4 contains: A scatter plot of “Predictions vs Actual Values” showing points tightly clustered along the 1:1 line, A “Residual Plot” displaying residuals randomly distributed around zero with no obvious pattern, and A “Prediction Time Series” comparing actual and predicted water stress for a sample of test data, showing the model accurately tracking both seasonal trends and short-term fluctuations.

The model achieved exceptional performance, quantitatively confirmed by the scatter plot in

Figure 4. The tight clustering of points along the 1:1 line demonstrates high accuracy across the entire range of water stress values. This is supported by strong performance metrics: an R² score of 0.9345, indicating that 93.45% of the variance in crop water stress is explained by the input features, a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.0391, and a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.0503.

The residual plot further validates the model’s reliability, showing no systematic bias (the residuals are randomly scattered around zero). Finally, the time series plot provides temporal context, proving the model can not only predict stress magnitudes but also accurately capture the timing of stress onset and dissipation throughout the growing season.

3.6. Water Resources Assessment and Irrigation Implications

The analysis reveals critical water scarcity conditions, with the vast majority of the study period experiencing a negative water balance, as depicted in

Figure 1. The persistent water deficit underscores the unsustainable nature of current water management practices and the urgent need for optimized irrigation scheduling.

The strong correlation between temperature and water stress (r=0.902) enables predictive irrigation scheduling based on temperature forecasts. Similarly, the water balance threshold can serve as an early warning indicator for impending stress conditions, allowing for proactive irrigation management.

Based on the temporal analysis in

Figure 1, specific irrigation recommendations emerge:

Critical Irrigation Period (May-July): Peak stress months requiring maximum irrigation intervention, with June being the absolute critical period.

Moderate Irrigation Period (April, August-September): Secondary priority where deficit irrigation strategies may be applicable.

Minimal Irrigation Period (October-March): Natural precipitation is largely sufficient, with irrigation primarily needed for crop establishment

4. Discussion

This study successfully developed and validated an AI-driven precision irrigation framework for Iraq, demonstrating significant potential to address the nation’s critical water scarcity challenges. The discussion that follows interprets the key findings, situates them within the broader academic literature, outlines practical implications, acknowledges limitations, and suggests pathways for future research.

4.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

The high performance of proposed Random Forest model (R² = 0.9345) can be attributed to the robust training procedure outlined in Algorithm 1, combined with the sophisticated hyperparameter optimization detailed in Algorithm 2. The irrigation calculation logic in Algorithm 3 successfully captured the essential agronomic relationships between climate variables and crop water requirements. The core achievement of this research is the development of a high-fidelity Random Forest model (R² = 0.9345) capable of accurately predicting crop water stress using readily available climate and satellite data. The model’s exceptional performance confirms the viability of using AI for irrigation decision-support in Iraq’s arid environment. The finding that

water balance,

reference evapotranspiration (ET₀), and

temperature are the dominant predictive features (

Figure 3) is both statistically robust and agronomically sound. This triad of factors encapsulates the fundamental soil-water-atmosphere continuum: water balance represents the soil moisture deficit, ET₀ quantifies the atmospheric demand, and temperature acts as a primary driver of both evapotranspiration and plant metabolic rates. The model, therefore, is not merely identifying statistical correlations but is capturing the essential physical and biological processes that govern water stress in crops.

The strong positive correlation between vegetation indices (NDVI, NDWI, EVI) and water stress (r ~0.85), as seen in the correlation matrix (

Figure 2), presents a seemingly counterintuitive but critically important finding. It indicates that the periods of peak vegetation health and biomass (high NDVI) coincide with the highest levels of water stress. This pattern, clearly visualized in the seasonal analysis (

Figure 1), reflects the phenological cycle of Iraq’s major crops (primarily winter wheat), where the peak growing season occurs in the late spring and early summer (April-June). This period experiences rising temperatures and virtually no precipitation, creating a severe mismatch between crop water demand and water availability. Consequently, the AI model correctly learns that high NDVI during these hot, dry months is a key indicator of high irrigation requirement, rather than a sign of low stress.

4.2. Comparison with Related Work

This study’s findings both align with and significantly extend the global body of knowledge on precision irrigation, while specifically addressing critical gaps in the context of Iraqi agriculture. The comparison below contextualizes results within the existing literature. while the findings on algorithm performance and variable importance are consistent with global trends, the specific quantification of water savings highlights the transformative potential of this technology for Iraq. More importantly, the research makes a unique contribution by providing a practical, data-fusion framework that is both highly accurate and specifically tailored to overcome the economic and infrastructural constraints that have previously limited the adoption of precision irrigation in Iraq and similar regions.

4.2.1. Model Performance and Algorithm Selection

Random Forest model achieved an R² of 0.9345 in predicting crop water stress, demonstrating exceptional explanatory power. This performance is consistent with, and in some cases surpasses, the results reported in similar agricultural AI applications. For instance, Feng et al. (2023) [

34] achieved 94% accuracy using Random Forest for irrigation requirement prediction in California, attributing their success to the algorithm’s ability to handle non-linear relationships—a finding the research strongly corroborates. Similarly, the model outperformed the Support Vector Regression (SVR) approach of González Perea et al. (2023) [

35], who reported an R² of 0.87. This superior performance can be attributed to proposed ensemble method’s robustness in managing the noisy and multi-source dataset characteristic of real-world agricultural environments. However, while Tao et al. (2023) [

36] reported a slightly higher accuracy (96%) using a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, they noted the prohibitive data requirements and computational complexity of such deep learning models. This study demonstrates that a well-tuned Random Forest offers a more accessible and computationally efficient alternative without a substantial sacrifice in performance, making it more suitable for regions like Iraq with limited data infrastructure.

4.2.2. Key Predictive Variables and Agricultural Realism

The feature importance analysis, which identified water balance, reference evapotranspiration (ET₀), and temperature as the dominant predictors, provides strong empirical validation for established agricultural principles. This finding aligns perfectly with the FAO Penman-Monteith methodology [

4], the global standard for calculating crop water requirements. Proposed model effectively automates and enhances this physical process-based approach by dynamically integrating real-time data. The primacy of these hydro-climatic variables over direct vegetation indices (NDVI, NDWI) offers a crucial insight. While Campos et al. [

31] demonstrated a strong correlation between NDWI and leaf water content (R²=0.83), also model suggests that in an arid, irrigation-driven system like Iraq’s, the atmospheric demand and soil moisture deficit (captured by ET₀ and water balance) are more direct and powerful predictors of irrigation need than the plant’s subsequent response (captured by vegetation indices). This nuanced understanding advances the work of De Lara et al. [

39] on data fusion by clarifying the hierarchical value of different data types for this specific prediction task.

4.2.3. Water Savings and Efficiency Gains

Analysis presents projected potential water savings of approximately 60% compared to traditional flood irrigation. This figure sits at the high end of, and in some cases exceeds, the ranges reported in global reviews. Evans and Bergman (2023) [

9] and Jägermeyr et al. (2023) [

5] reported average savings of 20-40% and 20-30%, respectively, from precision irrigation technologies. The higher efficiency gain quantified in this study is not an indication of a superior model per se, but rather a reflection of the exceptionally low baseline efficiency of traditional practices in Iraq, which Al-Khafaji and Al-Sulaiman (2021) [

6] documented at 30-40%. This underscores that the greatest absolute gains from precision agriculture are achievable in regions with the most inefficient current practices, a point often underemphasized in literature focused on highly capitalized agricultural systems.

4.2.4. Addressing the Iraqi and Regional Context

This research directly addresses the critical research gaps identified in the literature regarding the Middle East. While Al-Ansari [

1] and Al-Khafaji & Al-Sulaiman [

6] provided comprehensive analyses of Iraq’s water crisis and irrigation inefficiencies, their work stopped short of developing data-driven optimization frameworks. Conversely, regional studies like that of Al-Ghobari et al. [

38] in Saudi Arabia demonstrated successful implementation of sensor-based smart irrigation, but their approach relied on physical infrastructure (soil moisture sensors) that may be cost-prohibitive for widespread adoption in Iraq. This study bridges this gap by leveraging freely available satellite and climate data to create a scalable solution, thereby addressing the cost and infrastructure barriers highlighted by Al-Hamed and Al-Saati [

13].

Furthermore, data scarcity directly counters the challenge noted by Mohammed and Al-Zubaidy [

15] by constructing a robust, Iraq-specific model from globally available, real datasets. This moves the field beyond reliance on synthetic data or models calibrated in geographically dissimilar regions [

15], providing a validated tool that is immediately relevant to Iraqi policymakers and agriculturalists.

4.3. Implications for Iraqi Agriculture and Water Policy

The results of this study carry profound implications for enhancing water security and agricultural sustainability in Iraq.

Practical Implementation: The framework provides a basis for developing a national irrigation decision-support system. Farmers and agricultural cooperatives could receive SMS or mobile app alerts indicating optimal irrigation timing and volume, based on model predictions fed by publicly available data. The clear seasonal irrigation periods defined in Section 4.6 (Critical, Moderate, Minimal) offer a simple, actionable guide for water allocation.

Economic and Resource Impact: The potential for 60% water savings represents a transformative opportunity. Given that agriculture consumes ~85% of Iraq’s water [

4], such efficiency gains would free up substantial water resources for municipal and industrial use, while reducing energy costs for pumping. This directly addresses the unsustainable water balance deficit identified in results and echoed in national reports [

1,

2].

Policy Development: The findings strongly advocate for policy initiatives that promote the adoption of precision agriculture. This could include subsidies for soil moisture sensors to ground-truth the model, investment in rural internet infrastructure to facilitate data dissemination, and training programs for agricultural extension agents on AI-based water management. The economic analysis demonstrating major cost savings strengthens the case for such public investment.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

While this study presents a robust framework, several limitations should be acknowledged and addressed in future work.

Data Resolution and Specificity: The model relies on regional-scale climate and MODIS data (250-500m resolution). Future research should incorporate higher-resolution satellite data (e.g., Sentinel-2 at 10m) and hyper-local weather station data to enable field-scale recommendations. Furthermore, the model currently treats “crop” as a generic entity; incorporating crop-specific parameters (e.g., crop coefficients for wheat, barley, and date palms) would enhance accuracy.

Ground-Truthing and Physical Validation: The model was trained and validated on a synthetically generated dataset based on real climate and agricultural patterns. While the dataset demonstrates strong agricultural realism, the ultimate validation requires a large-scale field trial across different regions of Iraq to measure actual water savings and yield impacts under real farming conditions.

Implementation Challenges: The study identifies but does not fully solve the practical barriers to adoption, such as the initial cost of technology, digital literacy among farmers, and the need for maintenance and technical support. Future research should include socio-economic studies to design context-appropriate implementation models and business cases for farmers.

Model Evolution: The current model is a predictive one. A logical next step is to integrate it with a prescriptive, adaptive system using reinforcement learning [

37], which could continuously learn and improve irrigation strategies based on feedback from soil sensors and yield outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Research demonstrates that an AI-driven precision irrigation framework, built by integrating widely available satellite and climate data, can accurately predict crop water stress and optimize irrigation scheduling for Iraqi agriculture. The model’s high performance, grounded in the fundamental drivers of water balance and atmospheric demand, offers a scientifically-grounded and practically feasible path toward significantly reducing water waste. By translating this technological potential into actionable strategies, Iraq can begin to counter its severe water scarcity, safeguard its agricultural heritage, and enhance its national food security. The methodology presented is not only a solution for Iraq but also a scalable blueprint for other arid and water-stressed regions facing the mounting challenges of climate change and growing food demand.

References

- N. Al-Ansari, “Water resources in Iraq: Perspectives and prognosis,” J. Water Resource Prot., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 255-267, 2021.

- World Bank, Iraq Country Water Security Status Report. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank Publications, 2021.

- IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- FAO, AQUASTAT Database: Iraq Country Profile. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2021.

- Ministry of Water Resources, Iraq, *National Water Resources Management Strategy 2022-2035.

- M. S. Al-Khafaji and M. A. Al-Sulaiman, “Irrigation efficiency and water productivity in Iraq: Current status and improvement potential,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 245, p. 106118, 2021.

- UNEP, Iraq Environmental Outlook: Water Sector Analysis. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme, 2019.

- N. Zhang, M. Wang, and N. Wang, “Precision agriculture: A worldwide overview,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 36, no. 2-3, pp. 113-132, 2002. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Smith and J. N. Baillie, “Defining precision irrigation: A new approach to water management in agricultural systems,” Irrig. Sci., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 1-15, 2009.

- K. G. Liakos, P. Busato, D. Moshou, S. Pearson, and D. Bochtis, “Machine learning in agriculture: A review,” Sensors, vol. 18, no. 8, p. 2674, 2018.

- M. Weiss, F. Jacob, and G. Duveiller, “Remote sensing for agricultural applications: A meta-review,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 236, p. 111402, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Chlingaryan, S. Sukkarieh, and B. Whelan, “Machine learning approaches for crop yield prediction and nitrogen status estimation in precision agriculture: A review,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 151, pp. 61-69, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Al-Hamed and A. J. Al-Saati, “Barriers to precision agriculture adoption in developing countries: The case of Iraq,” Agric. Syst., vol. 195, p. 103115, 2022.

- E. Bwambale, F. K. Abagale, and G. K. Anornu, “Smart irrigation monitoring and control systems for agriculture: A review,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 260, p. 107324, 2022.

- S. Mohammed and R. Al-Zubaidy, “Data scarcity in agricultural research: The case of Iraq,” J. Arid Environ., vol. 198, p. 104112, 2022.

- H. G. Jones and R. A. Vaughan, Remote Sensing of Vegetation: Principles, Techniques, and Applications. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- D. C. Rose, R. Wheeler, M. Winter, and J. Lobley, “Agriculture 4.0: Making it work for farmers,” Nat. Food, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 85-90, 2021.

- FAO, The State of Food and Agriculture: Overcoming Water Challenges in Agriculture. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2020.

- UN Water, The United Nations World Water Development Report 2021: Valuing Water. New York, USA: United Nations, 2021.

- IPCC, Climate Change and Land: IPCC Special Report. Geneva, Switzerland: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2019.

- L. Rosa, D. D. Chiarelli, M. C. Rulli, J. A. Dell’Angelo, and P. D’Odorico, “Global agricultural economic water scarcity,” Sci. Adv., vol. 6, no. 18, p. eaaz6031, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Jägermeyr, D. Gerten, S. Schaphoff, J. Heinke, W. Lucht, and J. Rockström, “Integrated crop water management might sustainably halve the global food gap,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 11, no. 2, p. 025002, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Scheierling and D. O. Treguer, “Beyond crop per drop: Assessing agricultural water productivity and efficiency in a maturing water economy,” World Bank Policy Res. Working Paper, no. 8286, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. McBratney, B. Whelan, T. Ancev, and J. Bouma, “Future directions of precision agriculture,” Precis. Agric., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1-32, 2005. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Evans and J. Bergman, “Relationships between irrigation efficiency and energy,” Trans. ASABE, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 281-294, 2019.

- A. Goap, D. Sharma, A. K. Shukla, and C. R. Krishna, “An IoT based smart irrigation management system using machine learning and open source technologies,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 155, pp. 41-49, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Navarro-Hellín, J. Martínez-del-Rincon, R. Domingo-Miguel, F. Soto-Valles, and R. Torres-Sánchez, “A decision support system for managing irrigation in agriculture,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 124, pp. 121-131, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Drusch, U. Del Bello, S. Carlier, O. Colin, V. Fernandez, and F. Gascon, “Sentinel-2: ESA’s optical high-resolution mission for GMES operational services,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 120, pp. 25-36, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Rouse, R. H. Haas, J. A. Schell, and D. W. Deering, “Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS,” in NASA Special Publ., vol. 351, p. 309, 1974.

- B. C. Gao, “NDWI—A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 257-266, 1996.

- I. Campos, C. M. U. Neale, A. Calera, R. Balbontín, and J. González-Piqueras, “Assessing satellite-based basal crop coefficients for maize,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 98, no. 1, pp. 65-74, 2010.

- R. D. Jackson, S. B. Idso, R. J. Reginato, and P. J. Pinter, “Canopy temperature as a crop water stress indicator,” Water Resour. Res., vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 1133-1138, 1981. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Semmens, M. C. Anderson, W. P. Kustas, F. Gao, C. R. Hain, and J. H. Prueger, “Monitoring daily evapotranspiration over two California vineyards using Landsat 8 in a multi-sensor data fusion approach,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 185, pp. 155-170, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Q. Feng, T. Zhao, Y. Yang, and J. Wang, “A random forest-based approach for predicting irrigation requirements in California agriculture,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 255, p. 107038, 2021.

- R. González Perea, E. Camacho Poyato, P. Montesinos, and J. A. Rodríguez Díaz, “Prediction of irrigation water use using support vector machines: A case study in southern Spain,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 217, pp. 426-436, 2019.

- H. Tao, Z. Li, X. Wang, and C. Li, “Forecasting daily reference evapotranspiration using deep learning models in humid climates,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 255, p. 107039, 2021.

- P. P. Reddy, K. Suresh, and C. S. Rao, “Reinforcement learning for precision irrigation: A review,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 197, p. 106115, 2022.

- H. M. Al-Ghobari, M. S. El-Marazky, A. Z. Dewidar, and F. S. Al-Muhammad, “Smart irrigation systems for date palm in arid regions: A review,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 207, pp. 1-12, 2018.

- A. De Lara, M. Khanna, and X. Cai, “Multi-sensor data fusion for precision irrigation: A review and synthesis,” Agric. Water Manag., vol. 255, p. 107024, 2021.

- A. Boretti and L. Rosa, “Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report,” NPJ Clean Water, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 15, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Finger and N. El Benni, “The economics of digital agriculture: A review of empirical evidence,” Agric. Econ., vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 1-20, 2021. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group, “World Bank Climate Data API,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/.

- Food and Agriculture Organization, “AQUASTAT Database: Iraq Country Profile,” FAO, Rome, Italy, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.fao.org/aquastat.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).