1. Introduction

As a global Paleo-ocean system between the Gondwana and Laurasia supercontinents during the Phanerozoic [

1,

2], the Tethyan tectonic domain serves a natural laboratory for deciphering the mechanisms of ocean-continent transition, plates interaction, and continental growth, and has been focused by many researchers for years [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Suture zones and associated ophiolites in the Tibetan Plateau provide a record for over 500 million years of Tethyan tectonic evolution, which include the Proto-Tethyan West Kunlun suture, Paleo-Tethyan Kunlun, Jinsha and Shuanghu sutures, Meso-Tethyan Bangong suture, and Neo-Tethyan Yarlung-Zangbo suture [

1,

8]. They provide crucial evidence for reconstructing the tectonic evolution of ancient oceans. Among them, the Shiquanhe-Namtso Ophiolitic Mélange Zone (SNMZ) and Bangong-Nujiang Suture Zone (BNSZ) which separate the Qiangtang terrane to the north and the Lhasa terrane to the south represent the remnants of the Meso-Tethyan ocean [

1,

9]. Their tectonic setting and affinity holds important significance for recovery the Meso-Tethys framework and Tibet evolution, as well as the regional mineralization, but there are still remain some controversies [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

The Shiquanhe-Namtso Ophiolitic Mélange Zone, although has been discovered for a long time, but still has relatively lower research degree than Bangong-Nujiang Suture Zone. Several hypotheses were proposed about its tectonic nature, such as: 1) the southward tectonic nappe of the Bangong-Nujiang Suture Zone [

10,

12,

17,

18]; 2) the island arc and back-arc basin system formed by the subduction of the Bangong Meso-Tethys [

13,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]; 3) the remnants of an independent oceanic crust [

24,

25]. The intrusive magmatic rocks are important components of SNMZ, and it could provide important spatial and temporal informations besides the volcanic rocks. But the relevant research a seldom so far.

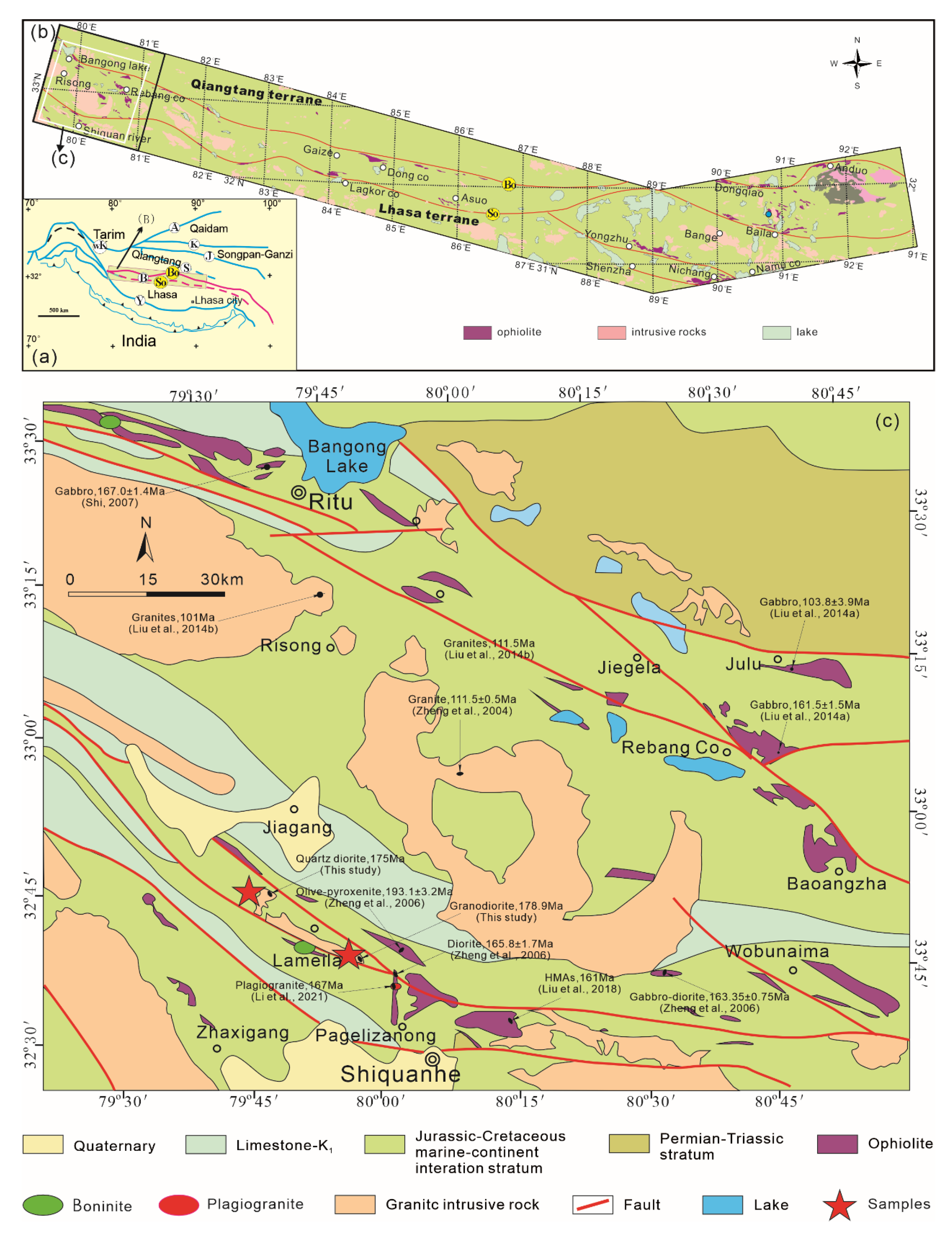

The Shiquanhe Ophiolitic Mélange (SOM) is located at the west end of the SNMZ (

Figure 1) and plays an important role in terms of the tectonic evolution of this mélange zone. In this contribution, we systematically collected representative intrusive rocks samples within the Shiquanhe Ophiolitic Mélange by detail field surveys. Through the analyses of spatial distribution and contact relation with country rocks, petrographic classification, whole-rock geochemical analysis, and zircon U-Pb chronological dating, this study aims to clarify the formation age, petrogenesis, tectonic setting of these intrusive rocks, and further more to discuss its implications for the tectonic framework of the Shiquanhe Ophiolitic Mélange with Bangong Suture.

2. Geological Background and Sample Locations

From north to south, the Tibetan Plateau is divided into several major parts by the Jinsha suture zone (JSSZ), Longmu-Shuanghu suture zone (LSSZ), BNSZ, SNMZ, and Indus-Yarlung Tsangpo suture zones (IYTSZ), including the Songpan-Ganzi, Northern Qiangtang (NQ), Southern Qiangtang (SQ), Lhasa, and Himalaya terranes (

Figure 1a) [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The BNSZ begins from the Bangong Lake (at the western end), passing through the Gerze, Dongqiao, Amdo, Dingqing, and terminates east to the Nujiang ophiolite. The SNMZ begins in the Shiquanhe (at the western end), passing through the Asa, Yongzhu, Namu Tso, Jiali and extends east to Bomi ophiolite (

Figure 1b) [

31,

33].

The selected study area is located in the Shiquanhe area near the Shiquanhe Town (

Figure 1b). As the largest exposed ophiolitic section in the west part of SNMZ, the ophiolitic mélanges in this region generally extend in a northwest direction, spanning over 60 kilometers [

22,

30,

34]. The diorite intrusions studied in this paper are exposed in the Banglongchamu and Qionggaleniao areas of the Shiquanhe region and mainly intruded into the Shiquanhe Ophiolitic Mélange as stocks and bosses (

Figure 1c and

Figure 2a,c). They extending in an east-west direction and have a total outcrop area of approximately 6.5 km

2. The primary rock types include quartz diorite, tonalite, and granodiorite.

3. Field Relations and Petrography

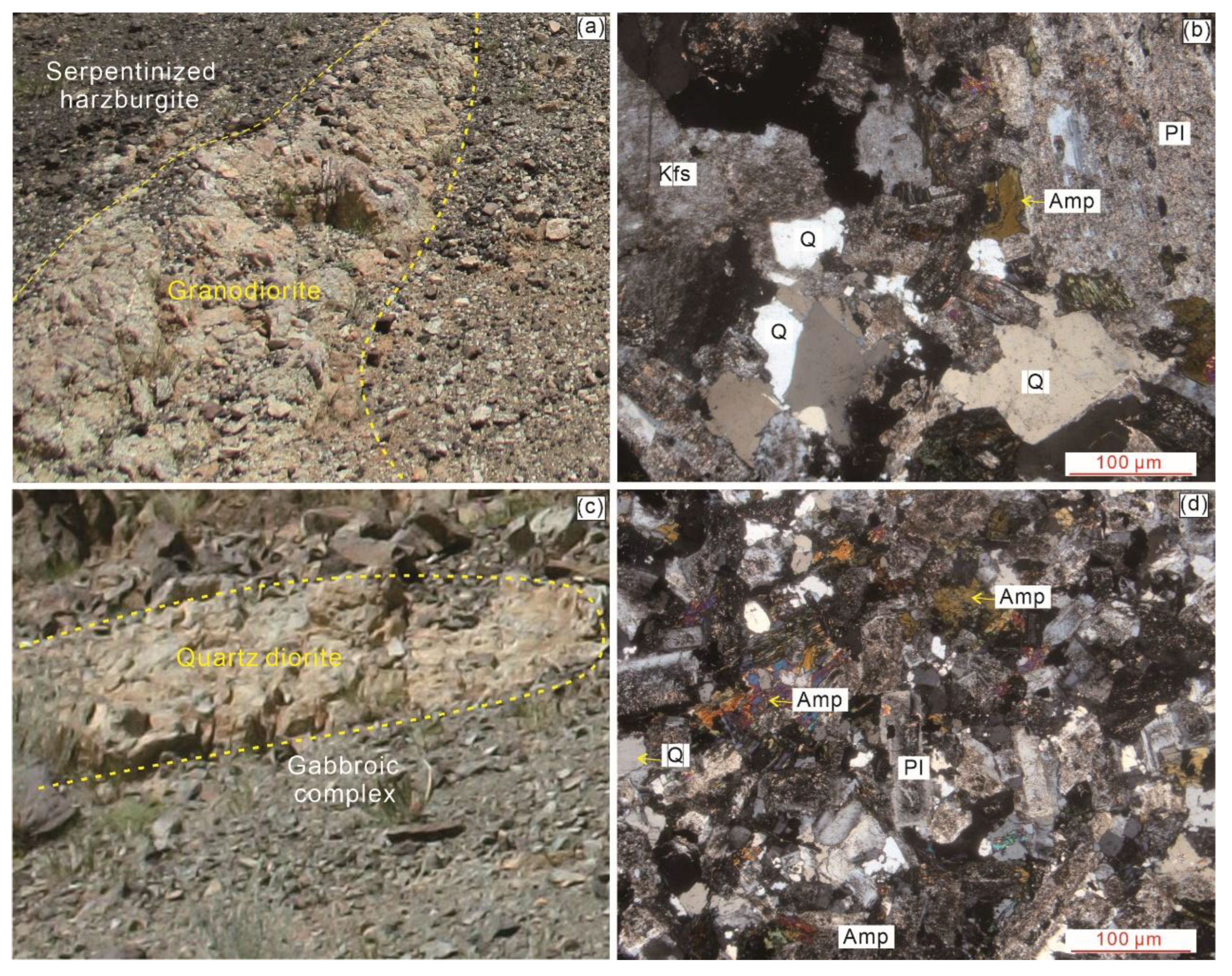

In the field, the granodiorite occurs primarily as lenses intruding serpentinized harzburgite (

Figure 2a). It shows gray-white in color and exhibits a fine-grained, granitic texture and a massive structure. Under the microscope, it is composed of plagioclase, K-feldspar, quartz, amphibole, and biotite. Plagioclase is about 4-50 vol. %. They occur as hypidiomorphic tabular crystals, with grain sizes generally 0.2-2 mm, and well-developed zoning structures as well as polysynthetic twinning. They are distributed randomly, with alterations of kaolinization and sericitization. K-feldspar is about 5-10 vol. %. They occur as anhedral granular crystals, mainly microcline, with grain sizes typically 0.5-3.5 mm. They are distributed interstitially, with slight kaolinization, and perthitic twinning is visible. Quartz is about 20-25 vol. %. They occur as anhedral granular crystals, with grain sizes usually 2-6 mm. They are distributed interstitially, with obvious recrystallization and local grain refinement at the edges. Distinct undulatory extinction is present within grains. Amphibole is approximately 5 vol. %. They occur as hypidiomorphic-anhedral prismatic or prism-granular crystals, with grain sizes 0.2-2 mm and some grains form pseudomorphs. They are distributed randomly, with alterations such as uralitization and chloritization. Biotite is about 5-10 vol. %. They occur as flaky crystals, with flake diameters generally 0.2-2 mm. They are distributed randomly, and most grains are replaced by chlorite, muscovite, or epidote to form pseudomorphs, with titanium minerals precipitated. The accessory minerals mainly include zircon and apatite (

Figure 2b).

The quartz diorite is primarily gray to light-gray in color. It occurs as lenses intruding into gabbroic complex (

Figure 2c) and exhibits a medium- to fine-grained, subhedral granular texture and a massive structure. Under the microscope, it is composed of plagioclase, quartz, amphibole, and pyroxene. Plagioclase accounts for about 50-60 vol. %. They occur as hypidiomorphic tabular crystals, with visible zoning structure, and polysynthetic twinning is common. The grain sizes ranging from 0.2 to 2 mm with a slight directional arrangement of long axes. They distributed randomly with alterations such as sericitization, kaolinization, and epidotization. Quartz is approximately 10 vol. %. They occur as anhedral granular crystals, with grain sizes typically 1-5.5 mm. They are distributed interstitially, with undulatory extinction observed within grains. Amphibole is about 20 vol. %. They occurs as hypidiomorphic prismatic or prism-granular crystals, with grain sizes mostly 0.2-2 mm (a few reaching 2-3.5 mm). They are distributed randomly, and aggregates exhibit a banded or striped appearance with slight orientation. A small number of grains are replaced by uralite, chlorite, or epidote. The accessory minerals mainly include magnetite and epidote (

Figure 2d).

4. Analytical Methods

4.1. Zircon U-Pb Geochronology

Two diorite samples (PM204TW1, quartz diorite and PM207TW1, granodiorite) were collected for zircon U-Pb analysis. Zircons were first separated from the samples by heavy-liquid and magnetic techniques. Cathodoluminescence (CL) images were subsequently used to select positions for U-Pb dating. U-Pb geochronology of zircon was conducted by LA-ICP-MS at Nanjing FocuMS Technology Co. Ltd. A 193 nm ArF-excimer laser ablation coupled with an Agilent 7500a Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (LA-ICP-MS) was used to determine the U-Pb isotopic compositions, and the detailed procedures follow the description of [

39]. 91500 (1062 Ma) was used as external standard to correct instrumental mass discrimination and elemental fractionation during the ablation. GJ-1 (600 Ma) and Pleovice (337 Ma) were treated as quality control for geochronology. Raw data reduction was performed off-line by ICPMSDataCal software [

37]. Isoplot/Ex_ver3 was used to make weighted mean age calculations and concordia diagrams [

40].

4.2. Major and Trace Elements Analyses

Five granodiorite and three quartz diorite samples were collected from fresh outcrops in Shiquanhe area. The major elemental composition analysis was done by using a PAN analytical Axios X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer at ALS Chemex Company, Guangzhou, China and trace element composition analysis was determined by using PE ELAN 6000 ICP-MS at Nanjing FocuMS Technology Co. Ltd. The samples were crushed into small chips, and the secondary vein materials, amygdaloids and weathered rims were identified and discarded by using a binocular microscope. The rock chips were picked, ultrasonically cleaned in 4N hydrochloric acid for 30 minutes, and then powdered to <200 mesh granule size in an agate ring mill after drying. Details of the major and trace element composition analysis procedures follow the description of Chen et al. [

41] and Qi and Grégoire [

42], respectively. The precision for the major element analysis is better than ±1-2% for concentration of 0.5 wt.% and for the trace elements precisions is better than ±5%.

5. Results

5.1. Zircon U-Pb Geochronology

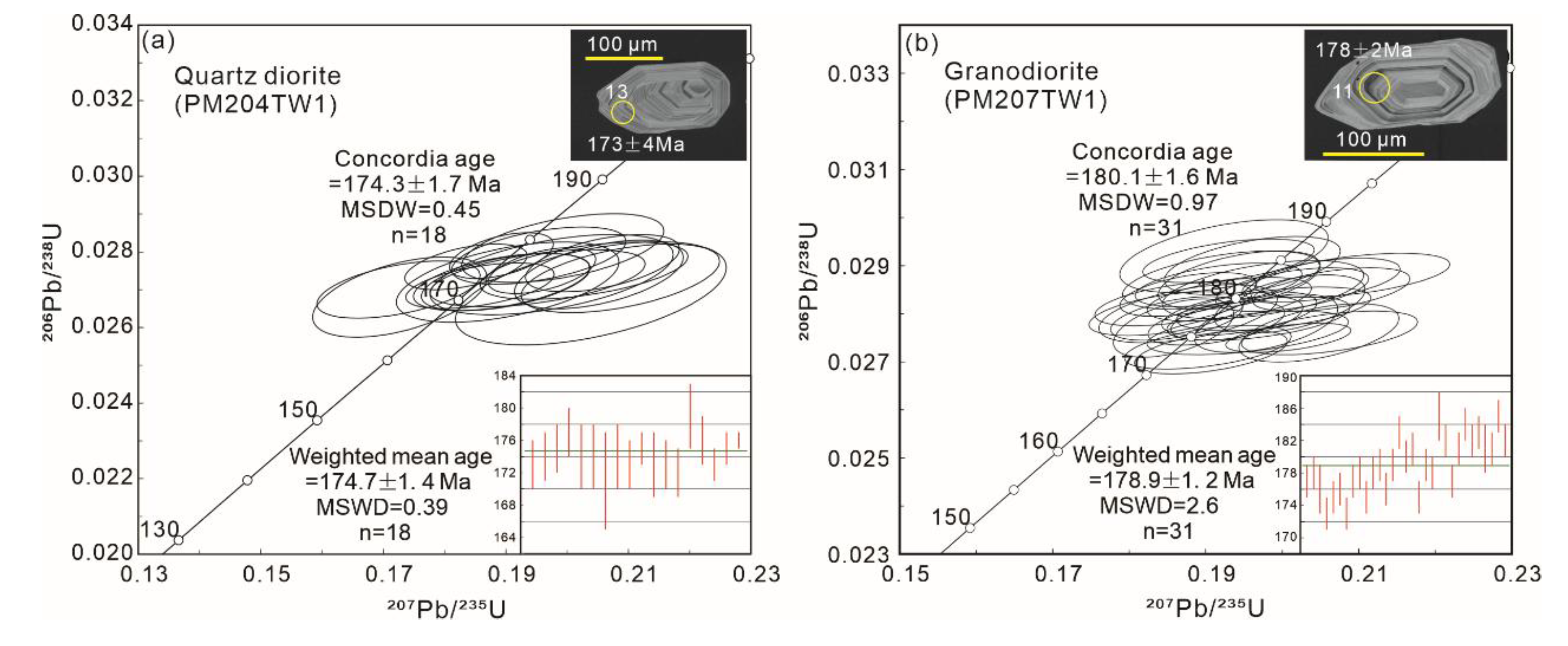

The results of zircon U-Pb dating analysis from the granodiorite and quartz diorite in supplementary

Table S1. In the cathodoluminescence (CL) images (

Figure 3a), the analysed zircon grains from the quartz diorite sample (PM204TW1) range in length from 60 to a few hundred microns and have sharp and clear edges. In addition, all of them exhibit oscillatory zoning, which are characteristic features of zircons that crystallized from magmas [

43]. For the granodiorite sample (PM207TW1), the zircon grains are mainly acicular and prismatic with clear edges and corners (

Figure 3b). Besides, these zircons exhibit distinct oscillatory zoning (

Figure 3b), which is consistent with the characteristics of zircons from acidic magma [

43]. Their Th/U ratios (0.27-0.59, PM204TW1; 0.36-0.58, PM207TW1, respectively) were higher than those of metamorphic zircons (

Supplementary Table S1). All these observations are consistent with characteristics of the magmatic zircons [

44].

For quartz diorite sample PM204TW1, 18 spots were analyzed on 18 zircons, all of which yielded relatively concordant ages. The

236Pb/

238U ages of the concordant spots are continuously distributed between 171 ± 4 Ma and 179 ± 4 Ma, yielding a weighted mean age of 174.7 ± 1.4 (Mean Square of Weighted Deviates, MSWD = 0.39) and a concordia age of 174.3 ± 1.7 Ma (MSWD = 0.45) (

Figure 3a). 31 measurement points were analyzed on 31 zircon grains, and 31 concordant ages were obtained for granodiorite sample PM207TW1. The zircon

236Pb/

238U ages of these 31 concordant spots range from 172 ± 6 Ma to 193 ± 7 Ma, yielding a weighted mean age of 178.9 ± 1.2 Ma (MSWD = 2.6) and a concordia age of 180.1 ± 1.6 Ma (MSWD =0.97) (

Figure 3b).

5.2. Whole-Rock Major and Trace Elements

5.2.1. Quartz Diorite

The SiO₂ content ranges from 55.49 wt. % to 61.66 wt. %, with an average of 58.49 wt. %, belonging to intermediate rocks. However, based on their microscopic features (such as the presence of abundant quartz), they could be classified as quartz diorite. Their contents of K₂O and P

₂O₅ are 0.42-0.80 wt. % and 0.06-0.08 wt. %, respectively. Besides, they have high MgO and Fe₂O

3t content (3.45-5.68 wt. % and 7.08-10.24 wt. %) (

Supplementary Table S2). Their differentiation index (DI) ranges from 39.18 to 48.96 (average: 42.93), and the solidification index (SI) ranges from 26.15 to 30.32 (average: 28.82), indicating a low degree of magma differentiation. The alkalinity rate (σ) ranges from 0.44 to 0.95 (average: 0.64), indicating the calcic series. The aluminum saturation index (A/NKC) ranges from 0.77 to 0.95 (average: 0.87), and the A/NK ratio ranges from 2.72 to 3.69 (average: 3.22), belonging the metaluminous rocks.

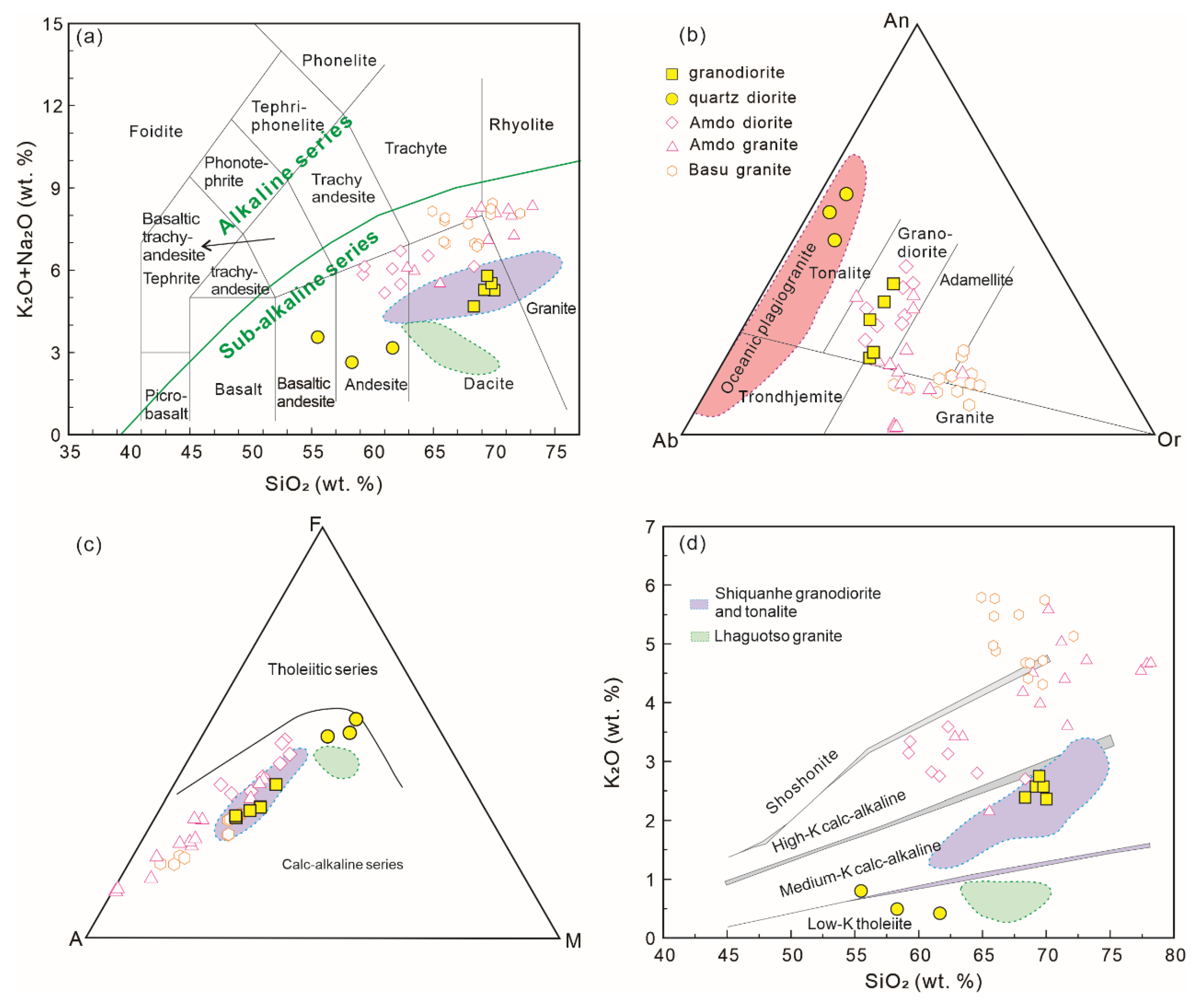

In the total alkali-silica (TAS) diagram [

45] (

Figure 4a), the samples belong to the subalkaline series. In the normative mineral An-Ab-Or diagram [

46] (

Figure 4b), the samples plot in the tonalite field, which is consistent with the microscopic identification as quartz diorite. When further plotted in the F-A-M classification diagram [

47] (

Figure 4c), the samples fall into the calc-alkaline series field. In the K₂O-SiO₂ variation diagram [

48] (

Figure 4d), two samples fall into the low-K (tholeiitic) series field and other samples dropped into the calc-alkaline series field, indicating the low potassium characteristics.

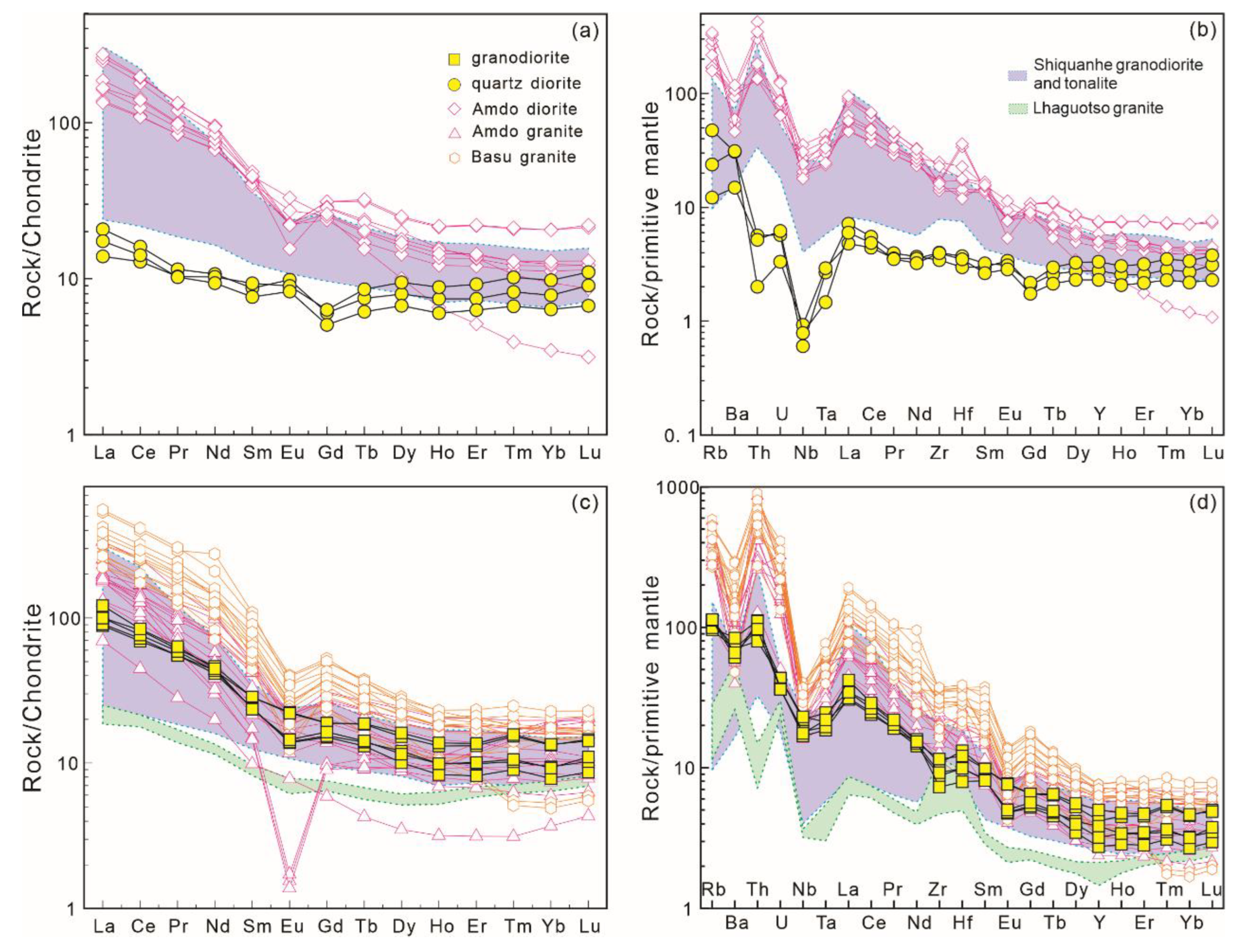

The total REE content (ΣREE) of the quartz diorite samples range from 25.53 to 29.66 ppm, with an average of 27.43 ppm, indicating a low total REE content (

Supplementary Table S2). The ΣLREE/ΣHREE ranges from 2.29 to 3.42, with an average of 2.99, indicating insignificant LREE-HREE fractionation. The Eu anomaly (δEu) ranges from 1.15 to 1.34, with an average of 1.26, showing weak Eu enrichment, indicating the mantle-derived magma source. The Ce anomaly (δCe) ranges from 0.96 to 1.02, with an average of 0.99, showing without obvious Ce depletion or enrichment. The chondrite-normalized ratios are as follows: (La/Yb)N = 1.34-2.58 (average: 2.14), (Ce/Yb)N = 1.23-2.07 (average: 1.73), and (Gd/Yb)N = 0.64-0.78 (average: 0.72). All these values indicate a weak LREE enrichment and insignificant REE fractionation. The REE distribution pattern curve is a nearly horizontal smooth curve (

Figure 5a).

Among the quartz diorite samples, the contents of Cs, Sc, and V are 1.24-4.05 ppm, 19.8-249 ppm, and 185-287 ppm, respectively. The Rb/Sr ratio of the quartz diorite samples ranges from 0.03 to 0.12 (average: 0.09), indicating a crust-mantle mixed magma source. The other trace element ratios are as follows: Rb/Ba = 0.07-0.14 (average: 0.10), K/Rb = 189.54-273.52 (average: 228.81), Zr/Hf = 37.63-41.87 (average: 39.85), and Nb/Ta = 3.98-15.74 (average: 8.6). In the trace element spider diagram (

Figure 5b), large ion lithophile elements (LILEs) such as K, Rb, Sr, and Ba are relatively enriched, while high field strength elements (HFSEs) are relatively depleted, with obvious Nb depletion. Compared with the spider diagram proposed by [

51], the samples show the normal arc granite characteristics .

5.2.2. Granodiorite

The SiO₂ content of the granodiorite ranges from 68.72 wt. % to 70.02 wt. %, with an average of 69.25%, belonging to acid rocks. Meanwhile, based on their microscopic features (such as the presence of abundant quartz and amphibole), they could be classified as granodiorite. Compared to the quartz diorite, the granodiorite samples have lower MgO (1.65-2.45 wt. %) and Fe₂O

3t (3.20-4.70 wt. %) content and higher content of K₂O and P₂O

5 (2.36-2.75 wt.% and 0.08-0.10 wt. %, respectively) (

Supplementary Table S2). Their differentiation index (DI) ranges from 65.56 to 75.43 (average: 71.43), and the solidification index (SI) ranges from 16.65 to 21.38 (average: 19.1), indicating a moderate degree of magma differentiation. The alkalinity rate (σ) ranges from 0.7 to 1.25 (average: 1.0), belonging to the calcic series. The aluminum saturation index (A/NKC) ranges from 0.95 to 1.21 (average: 1.06), and the A/NK ratio ranges from 1.77 to 2.28 (average: 1.96), indicating weakly peraluminous rocks. In the CIPW normative minerals, the corundum (C) content ranges from 0 to 2.55 wt. %: 2 samples have C < 1 wt. %, and 3 samples have C > 1 wt. %, with an average of 1.02 wt. %. In the normative mineral An-Ab-Or diagram (

Figure 4), most samples plot in the granodiorite field, which is consistent with the microscopic identification. In the total alkali-silica (TAS) diagram (

Figure 4a), the samples are classified as the subalkaline series. When further discriminate by the F-A-M classification diagram (

Figure 4c), the granodiorite samples also fall into the calc-alkaline series field, which is consistent with the calc-alkaline characteristics they display in the K₂O-SiO₂ diagram (

Figure 4d).

The total REE content (ΣREE) is relative low and ranges from 104.35 to 122.65 ppm, with an average of 113.16 ppm. The ΣLREE/ΣHREE ranges from 6.41 to 9.97, with an average of 8.27, showing significant LREE-HREE fractionation. The Eu anomaly (δEu) ranges from 0.706 to 1.036, with an average of 0.84 and the Ce anomaly (δCe) ranges from 0.88 to 0.98, with an average of 0.93, indicating the depletion of Eu and Ce. The chondrite-normalized ratios are as follows: (La/Yb)N = 6.20-12.40 (average: 9.03), (Ce/Yb)N = 4.8-8.49 (average: 6.78), and (Gd/Yb)N = 1.37-1.89 (average: 1.58). These values indicate LREE enrichment and significant REE fractionation, which also displayed in the right-dipping distribution patterns (

Figure 5).

6. Discussion

6.1. Formation Ages of the Quartz Diorite and Granodiorite

Through detailed field geological surveys, it was obviously that the granodiorite samples of this study intrude into the Jurassic ophiolitic harzburgite, and the quartz diorite intrudes into Jurassic ophiolitic gabbro complexes. This can thus constrain the intrude age is contemporary with the Jurassic ophiolite or later. The zircon U-Pb dating of this study obtain the weighted mean ages of 174.7±1.4 Ma and 178.9 ±1.2 Ma for quartz diorite and granodiorite samples respectively (

Figure 3a-b). So we can conclude that these intrusive rocks formed in Eearly Jurassic time. Furthermore, These ages are contemporary with the newly obtained forearc setting ophiolitic gabbros in north of Lameila [

23] which is nearby with our sample location, considering the two samples of granodiorite and quartz diorite are all derived from the Shiquanhe ophiolitic mélange, so we suggest there are ocean crust evaluation associated Early Jurassic magmatic events occurred in the Shiquanhe area.

6.2. Petrogenesis

6.2.1. Influence of Alteration

To investigate the petrogenesis of the intrusive rocks from the Shiquanhe ophiolitic mélange, we need to estimate alteration effect on the samples. As shown in the

Supplementary Table S2, the quartz diorite and granodiorite samples exhibit relatively low loss on ignition (LOI) values (1.68-2.82 wt. %), indicating that they have not been significantly affected by alteration or metamorphism. This is also consistent with their microscopic observations (

Figure 2b,d). Consequently, we can use the elemental compositions and their ratios to discuss the petrogenesis and tectonic environment of these samples.

6.2.2. Petrogenesis of Quartz Diorite

In the A/CNK-A/NK diagram [

53] (

Figure 6a), the quartz diorites plot in the metaluminous field, which is consistent with the late Early Jurassic granitic rocks in the Lhaguotso area within the BNSZ [

50]. This suggests that the quartz diorite samples in this study may have I-type granite features (i.e., formed by the partial melting of an unweathered igneous source rock), which is further supported by the (Zr+Nb+Y+Ce) vs. FeOt/MgO [

54] and SiO₂ vs. P₂O₅ [

50] diagrams (

Figure 6b,c). Meanwhile, the high MgO and Fe₂O

3t of the Quartz diorite, which is consistent with the Lhaguotso plagiogranites, Shiquanhe High-Mg andesites [

55] within the SNMZ and Archean Sanukitic rocks, post-Archean High-Mg adakites, and boninites [

56,

57,

58,

59]. These intermediate-acid rocks enriched in mafic components and are interpreted as a significant contribution of mantle-derived components to their source [

50]. In addition, the low Rb/Sr and Rb/Ba ratios, lower Th contents, relatively weak light rare earth element (LREE) enrichments of the quartz diorites also support that these rocks were formed from a mantle-derived magma source. This implies that the magma for the quartz diorite samples in this study may contain a significant mafic component. In the C/MF vs. A/MF diagram [

60] (

Figure 6d), the quartz diorite samples fall into the field of partial melting of mafic rocks, implying that the the partial melting of mafic rock origin.

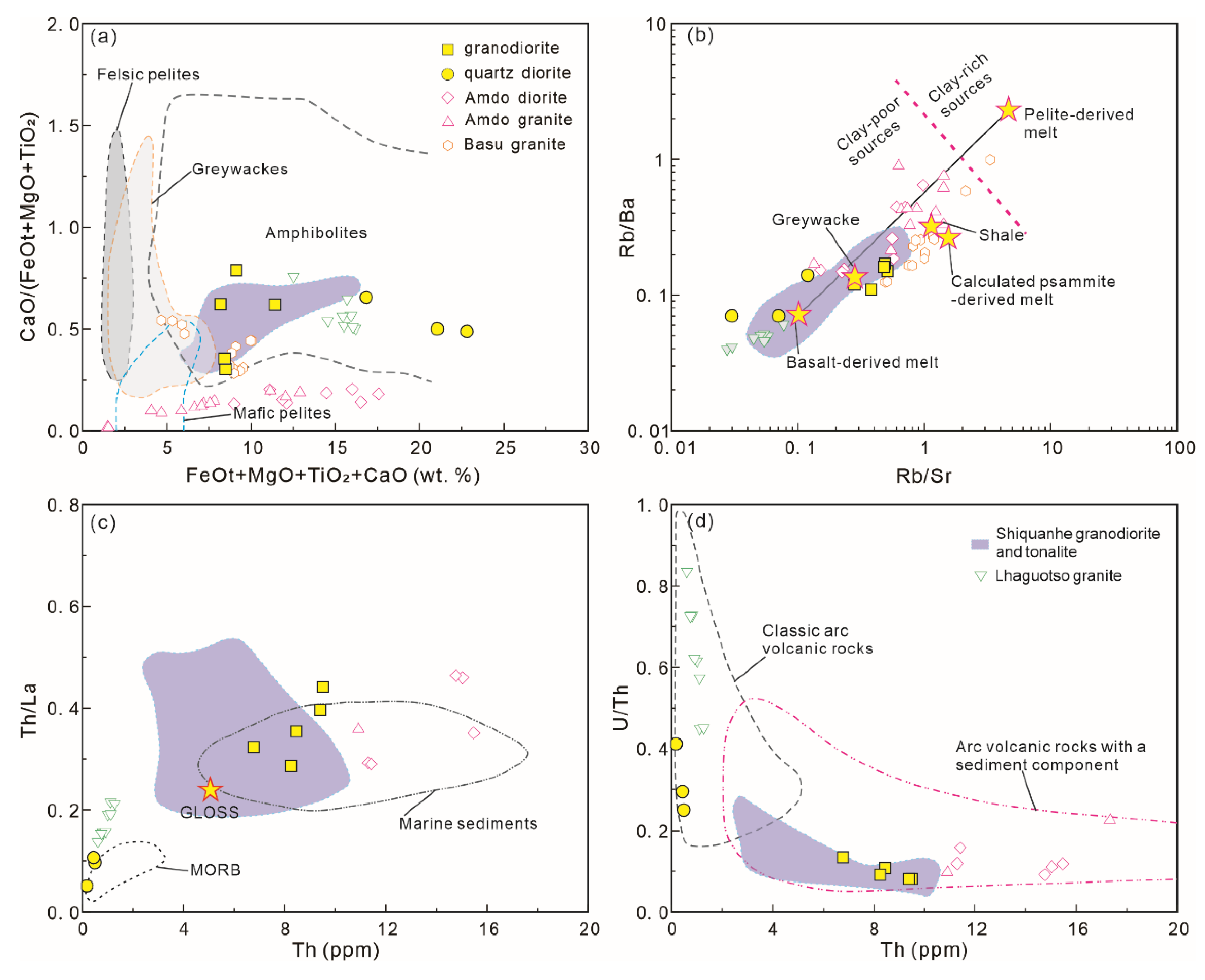

In the CaO/(FeOt+MgO+TiO₂) vs. (FeOt+MgO+TiO2+CaO) [

62], Rb/Ba vs. Rb/Sr [

63], and Th/La vs. Th [

64], diagrams, the quartz diorite samples, similar to the Lhaguotso high-Mg granites within the SNMZ [

50], all plot in fields close to amphibolite, metabasalt, or mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) (

Figure 7a-c). This supports the inference of a mantle-derived source without obvious crust material input. Additionally, the quartz diorite samples in this study, analogous to the Laguocuo high-Mg granites, are characterized by low Th content and high U/Th ratios, and they both fall into the field of sediment-free island arc volcanic rocks in the U/Th vs. Th diagram [

55,

65] (

Figure 7d). So we could conclude that the magma of the quartz diorite was derived from the melting of mantle-derived mafic rocks, without the obvious addition of crust material.

6.2.3. Petrogenesis of Granodiorite

As discussed in the

Section 5.2, the granodiorites have higher SiO₂, K₂O, P₂O

5, and lower MgO and Fe₂O

3t than quartz diorites. This implies that the magma properties of the granodiorites may be different from those of the quartz diorites. Meanwhile, the granodiorites have higher A/CNK values than the quartz diorites as shown in

Figure 6a. They plot within the field of previously identified coeval granodiorites and tonalites from the Shiquanhe area [

34] and share similar characteristics with them, with some samples also exhibiting peraluminous signatures (

Figure 6a). This suggests that the granodiorites exhibit transitional characteristics towards S-type granites (i.e., formed by the partial melting of sediment rock). This conclusion further supported by their relatively uniform FeOt/MgO ratios and variable (Zr+Nb+Y+Ce) contents (

Figure 6b), as well as variable SiO₂ and consistent P₂O₅ in some samples (

Figure 6c). The granodiorites plot across a wide range in the C/MF vs. A/MF diagram (

Figure 6d), overlapping the partial melting fields for metamorphic mudstone, metamorphic greywackes, and mafic rocks. This distribution emphasis their transitional character towards S-type granites and indicate the input of sedimentary-derived material into the magma.

The granodiorite samples exhibit uniform FeOt+MgO+TiO₂+CaO contents and variable CaO/(FeOt+MgO+TiO₂) ratios, and they plot analogously to coeval granitic rocks from the Shiquanhe area in the CaO/(FeOt+MgO+TiO₂) vs. (FeOt+MgO+TiO₂+CaO) diagram (

Figure 7a), distributing close to the mafic and amphibolite fields. This suggests the mafic rock origin of their magma. Meanwhile, the granodiorite samples plot in or close to the field of the Shiquanhe coeval granitic rocks in the Rb/Ba vs. Rb/Sr, Th/La vs. Th diagrams (

Figure 7b and c). Besides, the granodiorite in this study, along with coeval granitic rocks from the Basu and Amdo areas of the BNSZ, all plot within a field with sediments contribution in the the Rb/Ba vs. Rb/Sr, and Th/La vs. Th diagrams (

Figure 7b and c). All these indicating a mantle-derived source with sedimentary input. Furthermore, analogous to the coeval granitic rocks from the Amdo and Shiquanhe areas [

14,

34], the granodiorites in this study also plot within the field of island arc volcanic rocks with sediment components in the U/Th vs. Th diagram (

Figure 7d). So, we could conclude that the granodiorite magma originated from a mantle-derived mafic source with sediment input in the island arc environment.

6.3. Tectonic Setting and Its Implications

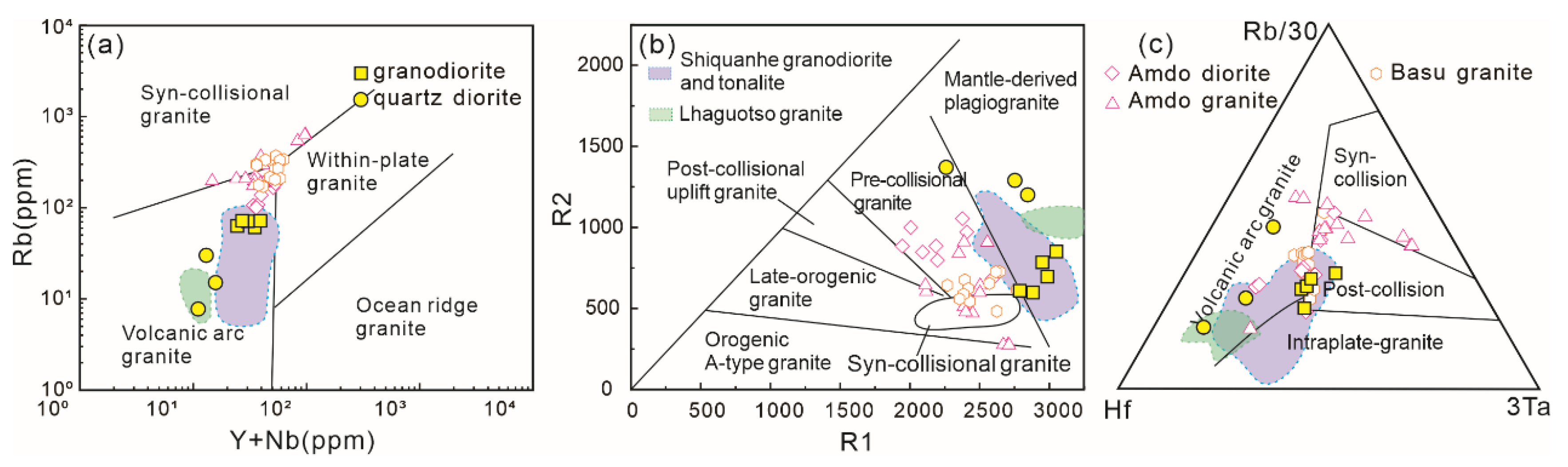

Multiple analysis of tectonic setting discrimination and trace element characteristics could define our intrusive rocks formed in a subduction-related island arc setting [

16,

66,

67]. In the Rb-Y+Nb diagram (

Figure 8a), all our samples as well as other intrusive rock samples along the SNMZ including Amdo diorites, and Basu granite are all dropped in the volcanic arc granite (VAG) field, which indicates an arc environment. In the R1-R2 diagram (

Figure 8b), the samples all fall in the mantle trondhjemite field. In the Rb/30-Hf-3Ta diagram (

Figure 8c), the samples also plotted in the volcanic arc granite field. Furthermore, the REE and trace element pattern of our samples are highly consistent with the standard arc granite pattern established by Poli et al. [

51] and coeval arc setting granites developed in BNSZ (

Figure 5) [

14,

49,

50]. Additionally, the enrichment in large ion lithophile elements (LILEs) and depletion in high field strength elements (HFSEs) provide further evidence of the island arc setting.

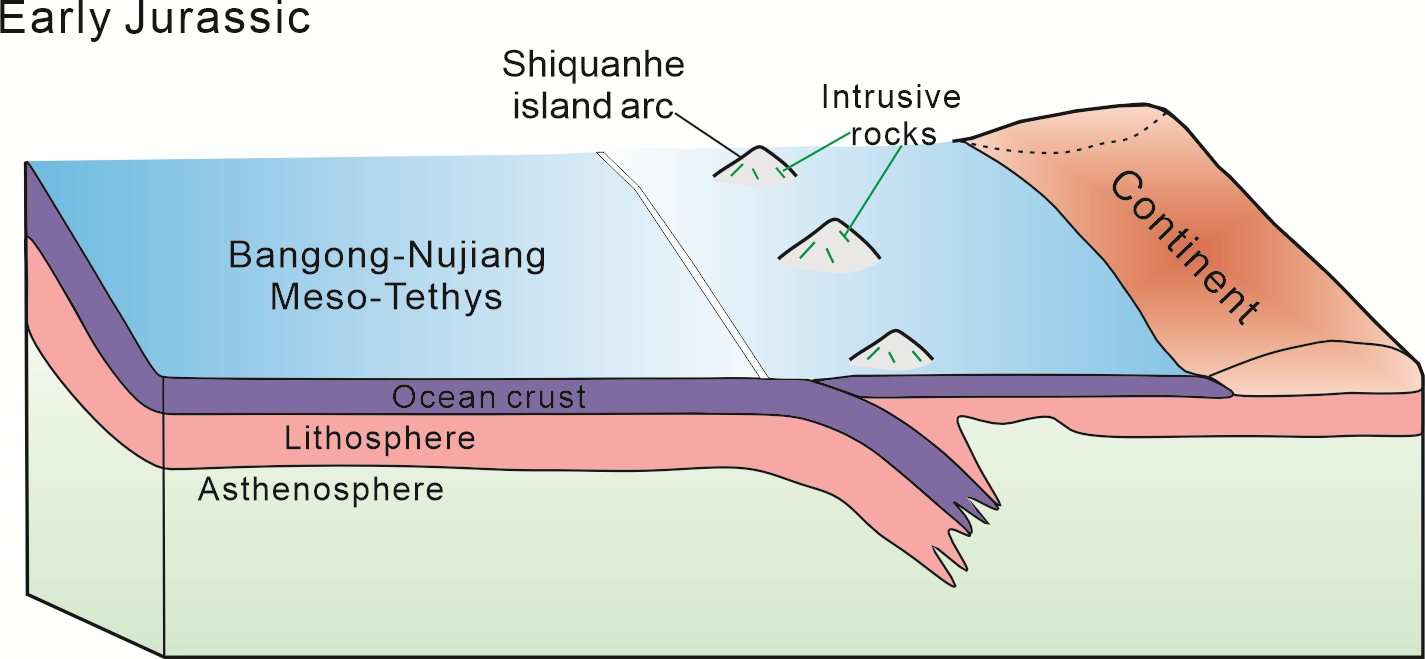

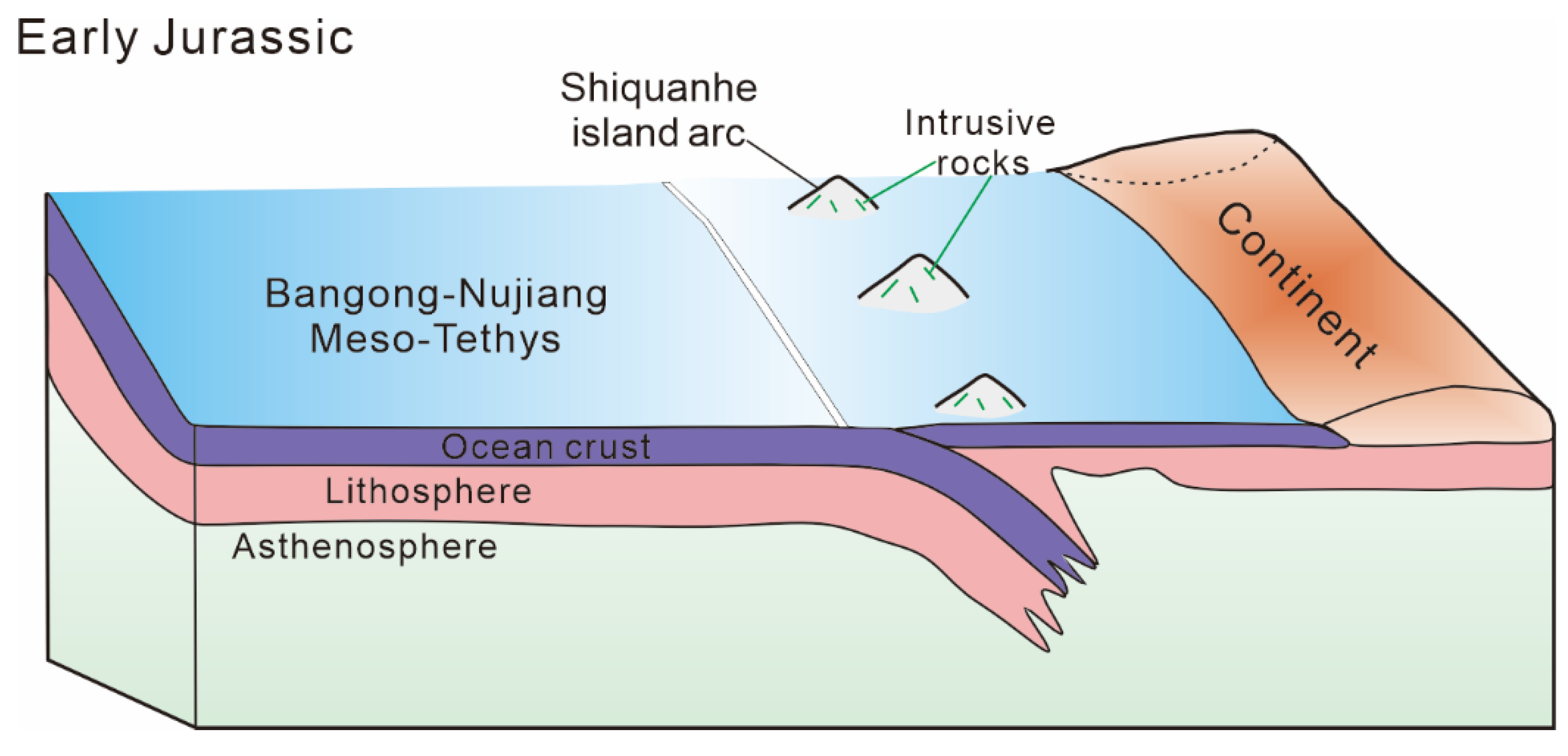

The studied intrusive rock suits belong to the TG (tonalite-granodiorite) which are the sub-assemblage of the TTG (tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite) suite, so we attribute them to a TTG-like suits [

59]. Additionally, their rock series are from the low-K tholeiitic to calc-alkaline series, with a prominent metaluminous attribution which are similar to the slab subduction derived trondhjemite-tonalite-dacite in modern ocean [

71], especially formed in the island arc tectonic environment. Combined with the island arc setting discussed above, we suggest our Early Jurassic intrusive samples formed in an island arc environment during the Meso-Tethys subduction stage [

72,

73,

74]. Consider the newly discovery of the nearby Early Jurassic north Lameila forarc ophiolite which represent the early-stage subduction of the Bangong Meso-Tethys [

23] and references therein), it is reasonable to conclude the Shiquanhe opiolitic mélange represent an island arc and back-arc assemblage rather than an independent ocean basin (

Figure 9). Combine with the previous work discovered flat subduction in Gaize area [

75,

76], and the develop of Ga’erqiong-Galale copper-gold ore field in Shiquanhe area [

77], this Early Jurassic island arc magmatism initiated a new era of the Mesozoic mineralization in SNMZ, central Tibet.

7. Conclusions

(1) The zircon LA-ICP-MS U-Pb dating obtained the weighted mean ages of quartz diorite and granodiorite within the Shiquanhe Ophiolitic mélange are 174.7 ± 1.4 Ma and 178.9 ± 1.2 Ma respectively, indicate they are formed in Early Jurassic.

(2) The geochemistry of these Early Jurassic intermediate intrusive rocks indicates a subduction induced island arc-type TTG-like magmatism.

(3) The Shiquanhe opiolitic mélange represent an island arc and back-arc assemblage rather than an independent ocean basin.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1. Results of zircon U-Pb dating of Shiquanhe granodiorite and quartz diorite. Table S2. Major and trace elements abundances of Shiquanhe granodiorite and quartz diorite.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D., W.L., X.Z. and R.D.; data curation, C.Y., Y.S. and H.Z., J.L.; formal analysis, X.K., H.Z. and Y.B.; funding acquisition, K.D. and W.L.; investigation, X.K., H.Z. and Q.W.; project administration, K.D., R.D., W.L.; supervision, X.Z., R.D., W.L.; Methodology, W.L. and X.Z.; Visualization, K.D., X.Z. and C.Y.; writing—original draft, K.D., X.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.D., W.L.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Deep Earth Probe and Mineral Resources Exploration-National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2025ZD1005003), National Key Research and Development Program of China: Demonstration of Responsible Exploration and Resources Expansion of Copper Polymetallic Resource Bases in Tibet (2022YFC2905001); the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, China [grant number 2024A1515010439]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [no. 41972049, 41472054, 42072229, 41977231]; China State Scholarship Fund of visiting scholar [Grant No. 202506380223, 20170638507].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Guo-Chao Gao and Wei Li for assistance related to regional geological fieldwork, Liang Li, Li Liu and He Xiao for analytical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Metcalfe, I. Multiple Tethyan ocean basins and orogenic belts in Asia. Gondwana Res. 2021, 100, 87–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotese, C.R. An atlas of Phanerozoic paleogeographic maps: the seas come in and the seas go out. Annu. Rev. Earth and Pl. Sc. 2021, 49, 679–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapponnier, P. , Xu, Z.Q, Roger, F., Meyer, B., Arnaud, N., Wittlinger, G., Yang, J. Oblique stepwise rise and growth of the Tibet Plateau. Science 2001, 294, 1671–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.L. , Wang, Q., Yang, J.H., Hao, L.L., Wang, J., Qi, Y., Yang, Z.Y., Sun, P. Growth of the continental crust induced by slab rollback in subduction zones: Evidence from Middle Jurassic arc andesites in central Tibet. Gondwana Res. 2023, 117, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampfli, G. , Borel, D. A plate tectonic model for the Paleozoic and Mesozoic constrained by dynamic plate boundaries and restored synthetic oceanic isochrons. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002, 196, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.W. , Zeng, M., Qian, Y.J., Deng, L.T, Li, Z.J., Stern, R.J., 2025. Late Mesozoic ridge subduction and subduction initiation in the Bangong-Nujiang Tethyan Ocean (Tibet): Evidence from two distinct arc magmatic systems GSA Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L. , Liang, H., Furnes, H., Zhang, X., Zeng, Q.G., Ma, Y.L., Yan, C., Ding, R.X., Zhong, Y., Gu, R.X., 2025. A snapshot of subduction initiation within a back-arc basin: Insights from Shiquanhe ophiolite, western Tibet. Geoscience Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, I. Gondwana dispersion and Asian accretion: Tectonic and palaeogeographic evolution of eastern Tethys. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 66, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y. , Wan, B., Zhao, L., Xiao, W.J., Zhu, R.X. Tethyan geodynamics. Acta Petrologica Sinica 2020, 36, 1627–1674, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Girardeau, J. , Marcoux, J., Allegre, C.J., Bassoullet, J.P., Tang, Y.K., Xiao, X.C., Zhao, Y.G., Wang, X.B. Tectonic environment and geodynamic significance of the Neo-Cimmerian Donqiao ophiolite, Bangong-Nujiang suture zone, Tibet. Nature 1984, 307, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Coulon, C. , Maluski, H., Bollinger, C., Wang, S.,. Mesozoic and Cenozoic volcanic rocks from central and southern Tibet: 39Ar-40Ar dating, petrological characteristics and geodynamical significance. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1986, 79, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, P. , Murphy, M.A., Yin, A., Harrison, T.M., Ding, L., Guo, J.H., 2003. Mesozoic and Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the Shiquanhe area of western Tibet Tectonics . [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A. , Deng, W.M. The ophiolites of the Tibetan geotraverses, Lhasa to Golmud (1985) and Lhasa to Kathmandu (1986). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1988, 327, 215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.L. , Huang, Q.T., Gu, M., Zhong, Y., Zhou, R.J., Gu, X.D., Zheng, H., Liu, J.N., Lu, X.X., Xia, B. Origin and tectonic implications of the Shiquanhe high-Mg andesite, western Bangong suture. Tibet. Gondwana Res. 2018, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.L. , Wang, B.D., Zhao, W.X., Yang, T.N., Xu, J.F. Discovery of eclogite in the Bangong Co-Nujiang ophiolitic mélange, central Tibet, and tectonic implications. Gondwana Res. 2016, 35, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.M. , Li, S.Z., Zhai, Q.G., Tang, Y., Hu, P.Y., Guo, R.H., Liu, Y.J., Wang, Y.H., Yu, S.Y., Cao, H.H., Wang, G. 2022. Jurassic tectonic evolution of Tibetan Plateau: A review of Bangong-Nujiang Meso-Tethys Ocean. Earth Sci. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X. , Zhang, K.J., Li, B., Wang, Y., Wei, Q.G., Tang, X.C. Zircon SHRIMP UPb geochronology and petrogenesis of the plagiogranites from the Lagkor Lake ophiolite, Gerze, Tibet China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2007, 52, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. , Zhai, Q.G., Hu, P.Y., Wang, W., Yan, Z., Wang, H.T., Zhu, Z.C. Forearc lava stratigraphy of the Beila Ophiolite, north-central Tibetan Plateau: Magmatic response to initiation of subduction of the Bangong-Nujiang Meso-Tethys Ocean. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.C. , Zhao, Z.D., Niu, Y.L., Mo, X.X., Chung, S.L., Hou, Z.Q., Wang, L.Q., Wu, F.Y. The Lhasa Terrane: Record of a microcontinent and its histories of drift and growth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 301, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.J. , Li, C., Zhang, X.Z., Wu, Y.W. Nature and evolution of the Neo-Tethys in central Tibet: synthesis of ophiolitic petrology, geochemistry, and geochronology. Int. Geol. Rev. 2014, 56, 1072–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.J. , Yin, Z.X., Liu, W.L, Huang, Q.T., Li, J.F., Liu, H.F., Wan, Z.F., Cai, Z.R., Xia, B. Tectonic evolution of the Meso-Tethys in the western segment of Bangonghu-Nujiang suture zone: Insights from geochemistry and geochronology of the Lagkor Tso ophiolite. Acta Geologica Sinica-English Edition 2015, 89, 369–388. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.X. , Li, C., Fan, J.J., Wang, M., Xie, C.M. Tectonic property of the Laguocuo ophiolite in Gerze County, Tibet: Constrains from petrology, geochemistry, LA-ICP-MS zircon U-Pb dating and Lu-Hf isotope. Geol. Bull. China 2018, 37, 1541–1553, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.L. , Liang, H., Furnes, H., Zhang, X., Zeng, Q.G., Ma, Y.L., Yan, C., Ding, R.X., Zhong, Y., Gu, R.X., 2025. A snapshot of subduction initiation within a back-arc basin: Insights from Shiquanhe ophiolite, western Tibet. Geoscience Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.C. , Chen, J.L., Xu, J.F., Wang, B.D., Huang, F. Sediment melting during subduction initiation: Geochronological and geochemical evidence from the Darutso high-Mg andesites within ophiolite mélange, central Tibet. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2016, 17, 4859–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.D. , Wang, L.Q., Zhou, D.Q., Wang, D.B., Yu, Y.P., Yan, G.C., Wu, Z. Longmu Co-shuanghu-changning-menglian suture zone: the boundary between Gondwanaland and pan-cathaysia mainland in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geol. Bull. China 2021, 40, 1783–1798. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, A. , Harrison, T.M. Geologic evolution of the Himalayan Tibetan orogeny. Annu. Rev. Earth and Pl. Sc. 2000, 28, 211–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.T. , Wang, L.Q., Li, R.S., Yuan, S.R., Ji, W.H., Yin, F.G., Zhang, W.P., Wang, B.D. Tectonic evolution of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 53, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.J. , Li, C., Zhang, X.Z., Wu, Y.W. Nature and evolution of the Neo-Tethys in central Tibet: synthesis of ophiolitic petrology, geochemistry, and geochronology. Int. Geol. Rev. 2014, 56, 1072–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L. , Zhong, Y., Sun, Z.L., Yakymchuk, C., Gu, M., Tang, G.J., Zhong, L.F., Cao, H., Liu, H.F., Xia, B. The Late Jurassic Zedong ophiolite: A remnant of subduction initiation within the Yarlung Zangbo Suture Zone (southern Tibet) and its tectonic implications. Gondwana Res. 2020, 78, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L. , Huang, Q.T., Gu, M., Zhong, Y., Zhou, R.J., Gu, X.D., Zheng, H., Liu, J.N., Lu, X.X., Xia, B. Origin and tectonic implications of the Shiquanhe high-Mg andesite, western Bangong suture. Tibet. Gondwana Res. 2018, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. , Liu, N.N., Nayak, R., Ma, Y.L., Wang, J.J., Hu, X.C., Pang, J.H., Huang, W.L., Zhong, Y., Liu, W.L., 2021a. An island arc origin of Jurassic plagiogranite in the Shiquanhe ophiolite, western Bangong Suture, Tibet: Zircon U–Pb chronology, geochemistry, and tectonic implications of Bangong Meso-Tethys. Geological Journal 56, 3941-3958.

- Zhang, K.J. , Zhang, Y.X., Tang, X.C., Xia, B. Late Mesozoic tectonic evolution and growth of the Tibetan plateau prior to the Indo-Asian collision. Earth-Science Reviews 2012, 114, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.J. , Xia, B., Zhang, Y.X., Liu, W.L., Zeng, L., Li, J.F., Xu, L.F. Central Tibetan Meso-Tethyan oceanic plateau. Lithos 2014, 210, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. , Liu, N.N., Nayak, R., Ma, Y.L., Wang, J.J., Hu, X.C., Pang, J.H., Huang, W.L., Zhong, Y., Liu, W.L., An island arc origin of Jurassic plagiogranite in the Shiquanhe ophiolite, western Bangong Suture, Tibet: Zircon U–Pb chronology, geochemistry, and tectonic implications of Bangong Meso-Tethys. Geological Journal 2021, 56, 3941–3958. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.J. , Zhang, Y.X., Tang, X.C., Xia, B. Late Mesozoic tectonic evolution and growth of the Tibetan plateau prior to the Indo-Asian collision. Earth-Science Reviews 2012, 114, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X. , Zhang, Y.X., Whitney, D.L., Zhang, K.J., Raia, N.H., Hamelin, C., Hu, J.C., Lu, L., Zhou, X.Y., Khalid, S. B. Crustal material recycling induced by subduction erosion and subduction-channel exhumation: A case study of central Tibet (western China) based on P-T-t paths of the eclogite-bearing Baqing metamorphic complex. GSA Bulletin 2021, 133, 1575–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.S. , Hu, Z.C., Zong, K.Q., Gao, C.G., Gao, S., Xu, J., Chen, H.H. Reappraisement and refinement of zircon U-Pb isotope and trace element analyses by LA-ICP-MS. Chinese Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y. , Xu, R.K., Ci, Q., Pang, Z.J., 2004. Geological Report and Map of the Shiquanhe Region (1: 250,000). Geological Survey of China, 453 P.

- Li, H. , Wang, M., Zeng, X.W., Luo, A.B., Feng, S.B. Zircon U-Pb and Lu-Hf isotopes and geochemistry of granitoids in Central Tibet: Bringing the missing Early Jurassic subduction events to light. Gondwana Res. 2021, 98, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. , 2003. Isoplot 3.0, a Geochronological Toolkit for Excel. Berkeley Geochronol. Center Special Publication 4, 1-70.

- Chen, L. , Zhao, Z.F., Zheng, Y.F. Origin of andesitic rocks: geochemical constraints from Mesozoic volcanics in the Luzong basin, South China. Lithos 2014, 190, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi and Grégoire, 2000. Determination of trace elements in 26 Chinese geochemistry reference materials by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Geostandards Newsletter 24, 51–63.

- Corfu, F. , Hanchar, J.M., Hoskin, P., Kinny, P. Atlas of zircon textures. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003, 16, 469–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskin, P.W.O. , Schaltegger, U. The Composition of Zircon and Igneous and Metamorphic Petrogenesis. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003, 53, 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemost, E.A.K. Naming materials in the magma igneous rock system. Earth Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.T. , Colo, D. A classification of quartz-rich igneous rocks based on feldspar ratio. U.S. Geological Survey 1965, 525, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, T.N. , and Baragar, W. R.A. A guide to the chemical classification of the common volcanic rocks: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1971, 8, 523–548. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood, P.C. Boundary lines within petrologic diagrams which use oxides of major and minor elements. Lithos 1989, 22, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Q. , Xu, Z.Q., Webb, A.A.G., Li, T.F., Ma, S.W., Huang, X.M. Early Jurassic tectonism occurred within the Basu metamorphic complex, eastern central Tibet: Implications for an archipelago-accretion orogenic model. Tectonophysics 2017, 702, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. , Wang, M., Zeng, X.W., Luo, A.B., Feng, S.B. Zircon U-Pb and Lu-Hf isotopes and geochemistry of granitoids in Central Tibet: Bringing the missing Early Jurassic subduction events to light. Gondwana Res. 2021, 98, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, G. , Frey, F.A., Ferrara, G. Geochemical characteristics of the South Tuscany (Italy) volcanic province: constraints on lava petrogenesis. Chem. Geol. 1984, 43, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun and McDonough, 1989. Chemic al and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. In: Saunders, A.D., Norry, M.J. (Eds.), Magmatism in the Ocean Basins. Geological Society Special Publications, London, pp. 313–345.

- Maniar, P.D. , Piccoli, P.M. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1989, 101, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J.B. , Currie, K.L., Chappell, B.W. A-type granites: geochemical characteristics, discrimination and petrogenesis. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1987, 95, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L. , Huang, Q.T., Gu, M., Zhong, Y., Zhou, R.J., Gu, X.D., Zheng, H., Liu, J.N., Lu, X.X., Xia, B. Origin and tectonic implications of the Shiquanhe high-Mg andesite, western Bangong suture. Tibet. Gondwana Res. 2018, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, G. , Tatsumi, Y., Nohda, S., Ishizaka, K., Jahn, B.M. Setouchi high-Mg andesites revisited: geochemical evidence for melting of subducting sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1998, 160, 479–492. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi, Y. Geochemical modeling of partial melting of subducting sediments and subsequent melt-mantle interaction: Generation of High-Mg andesites in the Setouchi volcanic belt, southwest Japan. Geology 2001, 29, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, Y. High-Mg andesites in the Setouchi volcanic belt, southwestern Japan: Analogy to Archean magmatism and continental crust formation? Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2006, 34, 467–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H. , Smithies, R.H., Rapp, R., Moyen, J.F., Champion, D. An overview of adakite, tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTG), and sanukitoid: relationships and some implications for crustal evolution. Lithos 2005, 79, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altherr, R. , Holl A., Hegner E., Langer C., KrEuzer H. High-potassium, calc-alkaline I-type plutonism in the European Variscides: northern Vosges (France) and northern Schwarzwald (Germany). Lithos 2000, 50, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, S. , Takahashi M. Regional variation in chemistry of the Miocene intermediate to felsic magmas in the Outer Zone and the Setouchi Province of Southwest Japan. The Geological Society of Japan (in Japanese with English Abstract). 1979, 85, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Douce What do experiments tell us about the relative contributions of crust and mantle to the origin of granitic magmas? Geological Society, London, Special Publications 1999, 168, 55–75. [CrossRef]

- Sylvester Post-collisional strongly peraluminous granites. Lithos 1998, 45, 29–44. [CrossRef]

- Plank and Langmuir The chemical composition of subducting sediment and its consequences for the crust and mantle. Chem. Geol. 1998, 145, 325–394. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.C. , Chen, J.L., Xu, J.F., Wang, B.D., Huang, F. Sediment melting during subduction initiation: Geochronological and geochemical evidence from the Darutso high-Mg andesites within ophiolite mélange, central Tibet. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2016, 17, 4859–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. , Xie, C.M., Li, C., Wang, M., Fan, J.J., Xu, W.L. Tectonic shortening and crustal thickening in subduction zones: evidence from Middle-late Jurassic magmatism in Southern Qiangtang, China. Gondwana Res. 2016, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. , Li, C., Yu, Y.P., Chen, J.W. Age, origin, and geodynamic significance of high-Al plagiogranites in the Labuco area of central Tibet. Lithosphere 2018, 10, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A. , Harris, N.B., Tindle, A.G. Trace element discrimination diagrams for the tectonic interpretation of granitic rocks. J. Petrol. 1984, 25, 956–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, R.A. , Bowden, P. Petrogenetic interpretation of granitoid rock series using multicationic parameters. Chem. Geol. 1985, 48, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.B. , Pearce, J.A., Tindle, A.G. Geochemical characteristics of collision-zone magmatism. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 1986, 19, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond M S, Defant M J, Kepezhinskas. Petrosenesis of slab-derived trondhjemite-tonalite-dacite/adakite magmas. Trans. Royal Soc. Edinburgh, Earth Sci. 1996, 87, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.W. , Wang, M., Li, H., Chi, P., Shen, D. Early Jurassic intra-oceanic subduction initiation along the Bangong Meso-Tethys: Geochemical and geochronological evidence from the Shiquanhe ophiolitic complex, western Tibet. Lithos 416-417. Lithos.

- Liu, W.L. , Liang, H., Furnes, H., Zhang, X., Zeng, Q.G., Ma, Y.L., Yan, C., Ding, R.X., Zhong, Y., Gu, R.X., 2025. A snapshot of subduction initiation within a back-arc basin: Insights from Shiquanhe ophiolite, western Tibet. Geoscience Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.T. , Zhang, C.L., Zhang, K.J., Hua, Y.J., Chen, W.C., Cao, Y.D., Cheng, P., 2023. Interaction of upwelling asthenosphere with oceanic lithospheric mantle in Bangong-Nujiang subduction zone: A new mechanism for the petrogenesis of Nb-enriched basalts. Lithos. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X. , Li, Z.W., Zhu, L.D., Zhang, K.J., Yang, W.G., Jin, X. Newly discovered eclogites from the Bangong Meso-Tethyan suture zone (Gaize, central Tibet, western China): mineralogy, geochemistry, geochronology, and tectonic implications. Int. Geol. Rev. 2016, 58, 74–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X. , Li, Z.W., Yang, W.G., Zhu, L.D., Jin, X., Zhou, X.Y., Tao, G., Zhang, K.J. Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous episodic development of the Bangong Meso-Tethyan subduction: Evidence from elemental and Sr-Nd isotopic geochemistry of arc magmatic rocks, Gaize region, central Tibet, China. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2017, 135, 212–242. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. , 2015. Metallogenic regularity and metallogenic prediction for Ga’erqiong-Galale copper-gold concentrated area, Tibet. Chengdu University of Technology, doctor thesis, 1-233 (in Chinese with English abstract).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).