Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: A subset of individuals develops persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection, including musculoskeletal (MSK) manifestations, a condition known as long COVID (LC). Emerging hypotheses suggest that chronic low-grade inflammation in LC may impair bone metabolism and compromise joint health. However, empirical evidence is limited, and the impact of LC on MSK health, particularly bone and joint integrity, is poorly understood. Aim: To determine the influence of LC on MSK function, including bone health, body composition, and joint integrity. Methods: A 12-month longitudinal prospective cohort feasibility study was conducted involving 45 adults with LC and 40 well-recovered (WR) post-COVID-19 controls. Baseline and follow-up assessments included dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for bone mineral density (BMD) and total body composition (TBC), alongside ultrasound of the hand and knee joints to evaluate intra-articular changes. Results: The LC group had more fat in the gynoid, android, and leg regions at each assessment point compared to the controls (p<0.01). LC showed a significantly lower synovial hypertrophy at the baseline, 13% compared to WR 45% (p=0.001), and a marginal improvement in hand synovial hypertrophy, over 12 months, from a median of 2 (IQR 1;5) to 1 (IQR 0;3) (p=0.012), as observed via MSK ultrasound. No notable differences were found between groups regarding BMD, either in the LC group compared to the control group or overtime. Conclusion: This cohort study of LC adults and controls found no evidence of rapid bone loss; however, adiposity and joint symptoms suggest the need for ongoing monitoring. Future research should focus on MSK markers, muscle function, advanced imaging, and improving MSK health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Ethics Approval

Data Collection and Assessments:

DXA Assessment

Ultrasound Assessment

- Synovial hypertrophy: Abnormal hypoechoic intra-articular tissue that is non-displaceable and poorly compressible, and which may exhibit a Doppler signal.

- Synovial effusion: Abnormal hypoechoic or anechoic intraarticular material that is displaceable and compressible but does not exhibit a Doppler signal.

- PD signal intensity: Area of colour signal within the joint capsule in the absence of background noise. Only when there is hypoechoic synovial hypertrophy.

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Demographics and Characteristics

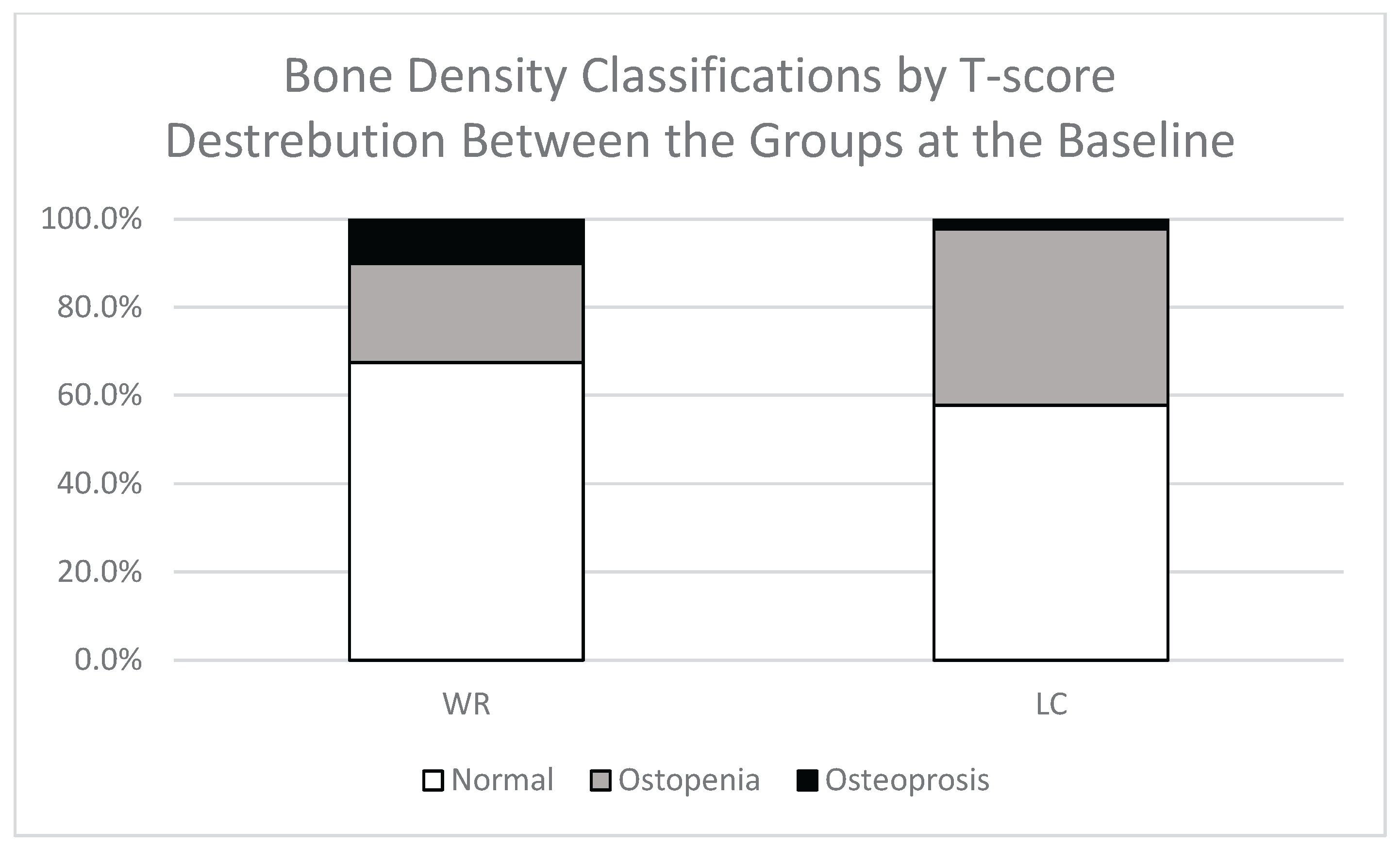

Comparison of BMD between LC and WR groups

Total Body Composition

Gynoid Region

Android Region

Leg Region and Total Lean Mass

Intra-Articular Changes

4. Discussion

Long COVID Associated with Increased Total Body Composition in Both Android and Gynoid Areas:

No Association of Bone Mineral Density or Bone Turnover Markers in Long COVID:

Long COVID Linked to Persistent Joints Pain With 12-Month Reduction in Hand Synovial Hypertrophy

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMD | Bone Mineral Density |

| DXA | Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry |

| LC | Long COVID |

| MSK | Musculoskeletal |

| PD | Power Doppler |

| TBC | Total Body Composition |

| WR | Well Recovered |

References

- Li, G.; Hilgenfeld, R.; Whitley, R.; De Clercq, E. Therapeutic strategies for COVID-19: progress and lessons learned. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2023, 22, 449-475. [CrossRef]

- Service, N.H. COVID recovery (long COVID). Available online: https://www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk/your-services/all-services-a-z/covid-recovery-long-covid/ (accessed on 08/01).

- Mahase, E. Covid-19: What do we know about "long covid"? BMJ 2020, 370, m2815, . [CrossRef]

- Malkova, A.; Kudryavtsev, I.; Starshinova, A.; Kudlay, D.; Zinchenko, Y.; Glushkova, A.; Yablonskiy, P.; Shoenfeld, Y. Post COVID-19 syndrome in patients with asymptomatic/mild form. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1408. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Long-term effects of coronavirus (long COVID): What is it? Available online: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/long-term-effects-of-coronavirus-long-covid/background-information/definition/ (accessed on 09 September).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 31/05).

- Nabavi, N. Long covid: How to define it and how to manage it. BMJ 2020, 370, m3489. [CrossRef]

- Bakılan, F.; Gökmen, İ.G.; Ortanca, B.; Uçan, A.; Eker Güvenç, Ş.; Şahin Mutlu, F.; Gökmen, H.M.; Ekim, A. Musculoskeletal symptoms and related factors in postacute COVID-19 patients. International journal of clinical practice 2021, 75, e14734. [CrossRef]

- Karaarslan, F.; Demircioğlu Güneri, F.; Kardeş, S. Postdischarge rheumatic and musculoskeletal symptoms following hospitalization for COVID-19: prospective follow-up by phone interviews. Rheumatology international 2021, 41, 1263-1271. [CrossRef]

- Sykes, D.L.; Holdsworth, L.; Jawad, N.; Gunasekera, P.; Morice, A.H.; Crooks, M.G. Post-COVID-19 Symptom Burden: What is Long-COVID and How Should We Manage It? Lung 2021, 199, 113-119. [CrossRef]

- Karaarslan, F.; Guneri, F.D.; Kardes, S. Long COVID: rheumatologic/musculoskeletal symptoms in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors at 3 and 6 months. Clin Rheumatol 2022, 41, 289-296. [CrossRef]

- Peghin, M.; Palese, A.; Venturini, M.; De Martino, M.; Gerussi, V.; Graziano, E.; Bontempo, G.; Marrella, F.; Tommasini, A.; Fabris, M. Post-COVID-19 symptoms 6 months after acute infection among hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2021, 27, 1507-1513. [CrossRef]

- Ghosn, J.; Piroth, L.; Epaulard, O.; Le Turnier, P.; Mentré, F.; Bachelet, D.; Laouénan, C. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms are highly prevalent 6 months after hospitalization: results from a large prospective cohort. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2021, 27, 1041. e1041-1041. e1044, . [CrossRef]

- Vaishya, R.; Jain, V.K.; Iyengar, K.P. Musculoskeletal manifestations of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics & Trauma 2021, 17, 280-281. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Sivan, M.; Perlowski, A.; Nikolich, J.Ž. Long COVID: a clinical update. The Lancet 2024, 404, 707-724. [CrossRef]

- Montes-Ibarra, M.; Orsso, C.E.; Limon-Miro, A.T.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Marzetti, E.; Landi, F.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Barazzoni, R.; Prado, C.M. Prevalence and clinical implications of abnormal body composition phenotypes in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2023, 117, 1288-1305. [CrossRef]

- Kerschan-Schindl, K.; Dovjak, P.; Butylina, M.; Rainer, A.; Mayr, B.; Röggla, V.; Haslacher, H.; Weber, M.; Jordakieva, G.; Pietschmann, P. Moderate COVID-19 disease is associated with reduced bone turnover. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2023. [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzawi, I.S.; Mohammed, N.S.; Saad, I. The impact of angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) on bone remodeling marker osteoprotegerin (OPG) in post-COVID-19 Iraqi patients. Cureus 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Atieh, O.; Durieux, J.C.; Baissary, J.; Mouchati, C.; Labbato, D.; Thomas, A.; Merheb, A.; Ailstock, K.; Funderburg, N.; McComsey, G.A. The Long-Term Effect of COVID-19 Infection on Body Composition. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1364. [CrossRef]

- Fedorchenko, Y.; Zimba, O. Long COVID in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology International 2023, 43, 1197-1207. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Danda, D.; Kavadichanda, C.; Das, S.; Adarsh, M.B.; Negi, V.S. Autoimmune and rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases as a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its treatment. Rheumatology International 2020, 40, 1539-1554. [CrossRef]

- Jaladhar, P.; S, C.; Salanke, M.; Kori, D. The Pattern of Post-viral Arthritis in COVID Pandemic State: An Experience of Tertiary Care Centre. J Assoc Physicians India 2021, 69, 11-12.

- Gulzar, R.; Rasheed, A.; Riaz, S.; Adnan, W.A.; Hafeez, U.; Malik, A.M. Musculoskeletal Symptoms in Patients Recovering from COVID-19. Muscles, Ligaments & Tendons Journal (MLTJ) 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Visco, V.; Vitale, C.; Rispoli, A.; Izzo, C.; Virtuoso, N.; Ferruzzi, G.J.; Santopietro, M.; Melfi, A.; Rusciano, M.R.; Maglio, A. Post-COVID-19 syndrome: involvement and interactions between respiratory, cardiovascular and nervous systems. Journal of clinical medicine 2022, 11, 524. [CrossRef]

- Michelen, M.; Manoharan, L.; Elkheir, N.; Cheng, V.; Dagens, A.; Hastie, C.; O'Hara, M.; Suett, J.; Dahmash, D.; Bugaeva, P. Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ global health 2021, 6, e005427. [CrossRef]

- Bakalets, O.; Dzyha, S.; Behosh, N. Functional diagnostics of the respiratory system in patients with Long COVID. Bull Med Biol Res 2023, 16, 60-66. [CrossRef]

- Jutant, E.-M.; Meyrignac, O.; Beurnier, A.; Jaïs, X.; Pham, T.; Morin, L.; Boucly, A.; Bulifon, S.; Figueiredo, S.; Harrois, A. Respiratory symptoms and radiological findings in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. ERJ open research 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, F.; Mokbel, K.; Meertens, R.; Obotiba, A.D.; Alharbi, M.; Knapp, K.M.; Strain, W.D. Bone Mineral Density, Bone Biomarkers, and Joints in Acute, Post, and Long COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 1694. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, F.; Meertens, R.; Obotiba, A.D.; Harries, L.W.; Appleby, S.; Mokbel, K.; Knapp, K.M.; Strain, W.D. Long COVID-Related Musculoskeletal Inflammation: A 12-Month Longitudinal Feasibility Cohort. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lewiecki, E.M.; Binkley, N.; Morgan, S.L.; Shuhart, C.R.; Camargos, B.M.; Carey, J.J.; Gordon, C.M.; Jankowski, L.G.; Lee, J.-K.; Leslie, W.D. Best practices for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measurement and reporting: International Society for Clinical Densitometry Guidance. Journal of clinical densitometry 2016, 19, 127-140. [CrossRef]

- Knapp, K.; GJ, B.G. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry: quality assurance and governance. Osteoporosis Review 2014, 22, 1-6.

- Control, C.f.D.; Prevention. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) procedures manual. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007.

- Shuhart, C.; Cheung, A.; Gill, R.; Gani, L.; Goel, H.; Szalat, A. Executive Summary of the 2023 Adult Position Development Conference of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry: DXA reporting, follow-up BMD testing and trabecular bone score application and reporting. Journal of Clinical Densitometry 2024, 27, 101435. [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, U.o. FRAX® tool. Available online: https://frax.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=9 (accessed on 1/5).

- Hippisley-Cox, J., & Coupland, C. QFracture® risk calculator. Available online: https://www.qfracture.org/ (accessed on 1/5).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Osteoporosis - prevention of fragility fractures. Available online: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/osteoporosis-prevention-of-fragility-fractures/ (accessed on March, 15).

- Blake, G.M.; Fogelman, I. The role of DXA bone density scans in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. Postgraduate medical journal 2007, 83, 509-517. [CrossRef]

- Cosman, F.; de Beur, S.J.; LeBoff, M.; Lewiecki, E.; Tanner, B.; Randall, S.; Lindsay, R. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis international 2014, 25, 2359-2381. [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, M.; Burmester, G.; Gerber, T.; Grassi, W.; Machold, K.; Swen, W.; Wakefield, R.; Manger, B. Guidelines for musculoskeletal ultrasound in rheumatology. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2001, 60, 641-649. [CrossRef]

- Filippucci, E.; Unlu, Z.; Farina, A.; Grassi, W. Sonographic training in rheumatology: a self teaching approach. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2003, 62, 565-567. [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. biometrics 1977, 159-174. [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, R.J.; Balint, P.V.; Szkudlarek, M.; Filippucci, E.; Backhaus, M.; D'Agostino, M.-A.; Sanchez, E.N.; Iagnocco, A.; Schmidt, W.A.; Bruyn, G.A. Musculoskeletal ultrasound including definitions for ultrasonographic pathology. The Journal of rheumatology 2005, 32, 2485-2487.

- Bruyn, G.A.; Iagnocco, A.; Naredo, E.; Balint, P.V.; Gutierrez, M.; Hammer, H.B.; Collado, P.; Filippou, G.; Schmidt, W.A.; Jousse-Joulin, S. OMERACT definitions for ultrasonographic pathologies and elementary lesions of rheumatic disorders 15 years on. The Journal of rheumatology 2019, 46, 1388-1393. [CrossRef]

- Szkudlarek, M.; Court-Payen, M.; Jacobsen, S.; Klarlund, M.; Thomsen, H.S.; Østergaard, M. Interobserver agreement in ultrasonography of the finger and toe joints in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology 2003, 48, 955-962. [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, M.A.; Conaghan, P.; Le Bars, M.; Baron, G.; Grassi, W.; Martin-Mola, E.; Wakefield, R.; Brasseur, J.-L.; So, A.; Backhaus, M. EULAR report on the use of ultrasonography in painful knee osteoarthritis. Part 1: prevalence of inflammation in osteoarthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2005, 64, 1703-1709. [CrossRef]

- Martinoli, C. Musculoskeletal ultrasound: technical guidelines. Insights into imaging 2010, 1, 99. [CrossRef]

- Kanis, J.A.; Burlet, N.; Cooper, C.; Delmas, P.D.; Reginster, J.Y.; Borgstrom, F.; Rizzoli, R. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2008, 19, 399-428. [CrossRef]

- Sebro, R.; Ashok, S.S. A Statistical Approach Regarding the Diagnosis of Osteoporosis and Osteopenia From DXA: Are We Underdiagnosing Osteoporosis? JBMR Plus 2021, 5, e10444. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, J.-W.; Wu, Y.; Rong, L.-J.; Ye, L.; Franco, O.H.; Chien, C.-W.; Feng, X.-R.; Chen, J.-Y.; Tung, T.-H. Prevalence and prognosis of sarcopenia in acute COVID-19 and long COVID: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of medicine 2025, 57, 2519678. [CrossRef]

- Appelman, B.; Charlton, B.T.; Goulding, R.P.; Kerkhoff, T.J.; Breedveld, E.A.; Noort, W.; Offringa, C.; Bloemers, F.W.; van Weeghel, M.; Schomakers, B.V. Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID. Nature communications 2024, 15, 17. [CrossRef]

- Colosio, M.; Brocca, L.; Gatti, M.F.; Neri, M.; Crea, E.; Cadile, F.; Canepari, M.; Pellegrino, M.A.; Polla, B.; Porcelli, S. Structural and functional impairments of skeletal muscle in patients with postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Journal of Applied Physiology 2023. [CrossRef]

- López-Sampalo, A.; Cobos-Palacios, L.; Vilches-Pérez, A.; Sanz-Cánovas, J.; Vargas-Candela, A.; Mancebo-Sevilla, J.J.; Hernández-Negrín, H.; Gómez-Huelgas, R.; Bernal-López, M.R. COVID-19 in Older Patients: Assessment of Post-COVID-19 Sarcopenia. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 733. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Legarra-Gorgoñon, G.; Oscoz-Ochandorena, S.; García-Alonso, Y.; García-Alonso, N.; Oteiza, J.; Ernaga Lorea, A.; Correa-Rodríguez, M.; Izquierdo, M. Reduced muscle strength in patients with long-COVID-19 syndrome is mediated by limb muscle mass. Journal of Applied Physiology 2023, 134, 50-58. [CrossRef]

- Londhe, P.; Guttridge, D.C. Inflammation induced loss of skeletal muscle. Bone 2015, 80, 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Disser, N.P.; De Micheli, A.J.; Schonk, M.M.; Konnaris, M.A.; Piacentini, A.N.; Edon, D.L.; Toresdahl, B.G.; Rodeo, S.A.; Casey, E.K.; Mendias, C.L. Musculoskeletal consequences of COVID-19. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 2020, 102, 1197.

- Donini, L.M.; Busetto, L.; Bischoff, S.C.; Cederholm, T.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Batsis, J.A.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dicker, D. Definition and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity: ESPEN and EASO consensus statement. Obesity facts 2022, 15, 321-335. [CrossRef]

- Hejbøl, E.K.; Harbo, T.; Agergaard, J.; Madsen, L.B.; Pedersen, T.H.; Østergaard, L.J.; Andersen, H.; Schrøder, H.D.; Tankisi, H. Myopathy as a cause of fatigue in long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms: Evidence of skeletal muscle histopathology. European Journal of Neurology 2022, 29, 2832-2841. [CrossRef]

- Agergaard, J.; Leth, S.; Pedersen, T.; Harbo, T.; Blicher, J.; Karlsson, P.; Østergaard, L.; Andersen, H.; Tankisi, H. Myopathic changes in patients with long-term fatigue after COVID-19. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 1974-1981. [CrossRef]

- Nurkovic, J. COVID-19 impact on bone mineral density. In Proceedings of the OSTEOPOROSIS INTERNATIONAL, 2021; pp. S209-S209.

- Haudenschild, A.K.; Christiansen, B.A.; Orr, S.; Ball, E.E.; Weiss, C.M.; Liu, H.; Fyhrie, D.P.; Yik, J.H.; Coffey, L.L.; Haudenschild, D.R. Acute bone loss following SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice. Journal of Orthopaedic Research® 2023, 41, 1945-1952.

- Qiao, W.; Lau, H.E.; Xie, H.; Poon, V.K.-M.; Chan, C.C.-S.; Chu, H.; Yuan, S.; Yuen, T.T.-T.; Chik, K.K.-H.; Tsang, J.O.-L. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces inflammatory bone loss in golden Syrian hamsters. Nature communications 2022, 13, 2539. [CrossRef]

- Awosanya, O.D.; Dalloul, C.E.; Blosser, R.J.; Dadwal, U.C.; Carozza, M.; Boschen, K.; Klemsz, M.J.; Johnston, N.A.; Bruzzaniti, A.; Robinson, C.M. Osteoclast-mediated bone loss observed in a COVID-19 mouse model. Bone 2022, 154, 116227. [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Santos, A.C.; Gonçalves, M.R.; Brito, C.B.; Barrioni, B.; Almeida, P.J.; Gonçalves-Pereira, M.H.; Silva, T.; Oliveira, S.R.; Pereira, M.M. Acute coronavirus infection triggers a TNF-dependent osteoporotic phenotype in mice. Life Sci. 2023, 324, 121750. [CrossRef]

- Elmedany, S.H.; Badr, O.I.; Abu-Zaid, M.H.; Tabra, S.A.A. Bone mineral density changes in osteoporotic and osteopenic patients after COVID-19 infection. Egyptian Rheumatology and Rehabilitation 2022, 49, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Inoue, Y.; Sakata, K.; Takahashi, C.; Takeshita, M.; Kassai, Y.; Miyazaki, T.; Morita, R.; Niki, Y.; et al. Significant association between joint ultrasonographic parameters and synovial inflammatory factors in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2019, 21, 14. [CrossRef]

- Gasparotto, M.; Framba, V.; Piovella, C.; Doria, A.; Iaccarino, L. Post-COVID-19 arthritis: a case report and literature review. Clinical rheumatology 2021, 40, 3357-3362. [CrossRef]

- Mukarram, M.S.; Ishaq Ghauri, M.; Sethar, S.; Afsar, N.; Riaz, A.; Ishaq, K. COVID-19: an emerging culprit of inflammatory arthritis. Case reports in rheumatology 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Selmi, C.; Gershwin, M.E. Diagnosis and classification of reactive arthritis. Autoimmunity reviews 2014, 13, 546-549. [CrossRef]

- Siva, C.; Velazquez, C.; Mody, A.; Brasington, R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. American family physician 2003, 68, 83-90.

- Parisi, S.; Borrelli, R.; Bianchi, S.; Fusaro, E. Viral arthritis and COVID-19. The Lancet Rheumatology 2020, 2, e655-e657. [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulos, D.; Calabrese, L.H. Virally associated arthritis 2008: clinical, epidemiologic, and pathophysiologic considerations. Arthritis research & therapy 2008, 10, 215. [CrossRef]

- Baimukhamedov, C.; Barskova, T.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Arthritis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. The Lancet Rheumatology 2021, 3, e324-e325.

- Griffith, J.F. Musculoskeletal complications of severe acute respiratory syndrome. In Proceedings of the Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology, 2011; pp. 554-560. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, M.; Giorgi, V.; Nebuloni, M.; Zerbi, P.; Gismondo, M.R.; Salaffi, F.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Rimoldi, S.G.; Manzotti, A. SARS-CoV-2 in the knee joint: A cadaver study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol 2022, 40, 34665699. [CrossRef]

- Kuschner, Z.; Ortega, A.; Mukherji, P. A case of SARS-CoV-2-associated arthritis with detection of viral RNA in synovial fluid. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open 2021, 2, e12452. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, M.; Giorgi, V.; Nebuloni, M.; Zerbi, P.; Gismondo, M.R.; Salaffi, F.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Rimoldi, S.G.; Manzotti, A. SARS-CoV-2 in the knee joint: A cadaver study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liew, I.Y.; Mak, T.M.; Cui, L.; Vasoo, S.; Lim, X.R. A Case of Reactive Arthritis Secondary to Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 2020, 26, 233. [CrossRef]

- Yokogawa, N.; Minematsu, N.; Katano, H.; Suzuki, T. Case of acute arthritis following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2021, 80, e101. [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Kishimoto, M.; Shimasaki, T.; Uchida, H.; Kurai, D.; Deshpande, G.A.; Komagata, Y.; Kaname, S. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. RMD Open 2020, 6, e001350. [CrossRef]

- Grozier, C.D.; Genoese, F.; Collins, K.; Parmar, A.; Tolzman, J.; Kuenze, C.; Harkey, M.S. Knee Effusion-Synovitis Is Not Associated With Self-Reported Knee Pain in Division I Female Athletes. Sports Health 2025, 19417381251323902. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Huang, W.Y.-J.; Sun, F.-H.; Wong, M.C.-S.; Siu, P.M.-F.; Chen, X.-K.; Wong, S.H.-S. Association of sedentary lifestyle with risk of acute and post-acute COVID-19 sequelae: a retrospective cohort study. The American Journal of Medicine 2023. [CrossRef]

- de Zwart, A.H.; Dekker, J.; Lems, W.F.; Roorda, L.D.; Van Der Esch, M.; Van Der Leeden, M. Factors associated with upper leg muscle strength in knee osteoarthritis: a scoping review. Journal of rehabilitation medicine 2018, 50, 140-150. [CrossRef]

- Hao, K.; Wang, J.; Niu, Y.; Wang, F. Obesity and hyperlipidemia were associated with more severe synovitis and structural abnormalities as well as inferior functional outcomes in knee osteoarthritis: a retrospective comparative study. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2024, 19, 845. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Multiple Testing and Protection Against a Type 1 (False Positive) Error Using the Bonferroni and Hochberg Corrections. Indian J Psychol Med 2019, 41, 99-100. [CrossRef]

- Baim, S.; Wilson, C.R.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Luckey, M.M.; Downs Jr, R.W.; Lentle, B.C. Precision assessment and radiation safety for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry: position paper of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. Journal of Clinical Densitometry 2005, 8, 371-378.

- Washington, K.F.H.P.o. Osteoporosis Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Guideline. Available online: https://wa.kaiserpermanente.org/static/pdf/public/guidelines/osteoporosis.pdf (accessed on 17/08).

| DXA T-score Baseline Results Between the Study Group WR and LC Participants. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-score | n=(WR/LC) | WR | LC | p | |

| Total Body | (39/45) | 0.534±1.379 | 1.037±1.161 | 0.073 | |

| L1-L4 | (32/33) | 0.244 ± 1.789 | 0.138 ± 1.184 | 0.780 | |

| Total Hip | RT | (36/37) | -0.247 ± 1.099 | 0.015 ± 1.036 | 0.263 |

| LT | (39/44) | -0.273 ± 1.174 | -0.033 ± 1.043 | 0.326 | |

| Fracture Risk (%) | |||||

| Major osteoporotic | (27/40) | 5.7 (3.3;11.8) | 4.85 (2.85;8.4) | 0.165 | |

| Hip | 0.5 (0.2;2.5) | 0.45 (0.1;0.9) | 0.221 | ||

| Musculoskeletal Imaging Results Comparing WR and LC Participants. | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Baseline | Follow-up | ||||||||

| Side | (n) | WR | LC | p | (n) | WR | LC | p | ||

| BMD | Total body(₽) | - | (39/45) | 1.219±0.127 | 1.223±0.099 | 0.876 | (30/36) | 1.215±0.143 | 1.219±0.104 | 0.909 |

| L1-L4(₽) | - | (32/33) | 1.232±0.221 | 1.204±0.142 | 0.547 | (23/28) | 1.233±0.258 | 1.195±0.151 | 0.519 | |

| Femoral neck(₽) | Rt | (39/45) | 0.967±0.144 | 0.974±0.134 | 0.819 | (30/36) | 0.961±0.144 | 0.98±0.143 | 0.605 | |

| Lt | (39/45) | 0.969±0.154 | 0.976±0.152 | 0.843 | (30/36) | 0.965±0.157 | 0.997±0.223 | 0.519 | ||

| Total hip(₽) | Rt | (39/45) | 1.026±0.160 | 1.024±0.138 | 0.959 | (30/36) | 1.023±0.176 | 1.029±0.152 | 0.885 | |

| Lt | (39/44) | 1.023±0.173 | 1.017±0.135 | 0.876 | (30/34) | 1.021±0.188 | 1.018±0.149 | 0.938 | ||

| TBC | Gynoid Region Fat (%)(‡) | (39/45) | 0.396 (0.322;0.46) | 0.492 (0.405;0.551) | 0.0008* | (30/36) | 0.382 (0.321;0.471) | 0.482 (0.410;0.541) | 0.0015* | |

| Gynoid Tissue Fat (%)(‡) | 0.403 (0.331;0.470) | 0.503 (0.412;0.562) | 0.0008* | 0.382 (0.321;0.471) | 0.482 (0.410;0.541) | 0.0015* | ||||

| Gynoid Fat Mass (g)(‡) | 4619 (3502;6739) | 6202 (4356;7733) | 0.0099* | 4564 (3583;6308) | 6238 (4599;7518) | 0.0089* | ||||

| Gynoid Lean Mass (g)(‡) | 6714 (5812;8161) | 6111 (5631;7430) | 0.088 | 6601 (5705;8929) | 6147 (5509;7727) | 0.221 | ||||

| Android Region Fat (%)(‡) | 0.431 (0.358;0.503) | 0.490 (0.428;0.561) | 0.0063* | 0.418±0.094 | 0.483±0.092 | 0.0065* | ||||

| Android Tissue Fat (%)(‡) | 0.435 (0.362;0.507) | 0.495 (0.432;0.564) | 0.0068* | 0.422±0.094 | 0.472±0.077 | 0.0065* | ||||

| Android Region Fat Mass (g)(‡) | 2569 (1971;3619) | 3054 (2284;4544) | 0.067 | 2425 (1861;3219) | 3198 (2008;4857) | 0.064 | ||||

| Legs Tissue Fat (%)(‡) | 0.361 (0.281;0.43) | 0.438 (0.349;0.524) | 0.0013* | 0.360±0.106 | 0.437±0.095 | 0.0029* | ||||

| Legs Lean Mass (g)(‡) | 15504 (13112;18933) | 13545 (12009;16863) | 0.026 | 14680 (13170;19137) | 13394 (12181;16794) | 0.132 | ||||

| Total Lean Mass (g)(‡) | 47058 (39960;55681) | 40649 (38494;50502) | 0.054 | 45326 (39627;55925) | 40774 (37743;53367) | 0.236 | ||||

| Intra-Articular | Hand Synovial Hypertrophy(‡) | (40/45) | 2 (1;4) | 3 (1;5) | 0.502 | (30/36) | 1.5 (0;3) | 1 (0;3) | 0.742 | |

| Hand Synovial Effusion(‡) | 0 (0;1) | 0 (0;1) | 0.684 | 0 (0;1) | 0 (0;0) | 0.212 | ||||

| Hand Power Doppler(‡) | 1 (0;3) | 1 (0;4) | 0.274 | 1 (0;2) | 0.5 (0;2) | 0.695 | ||||

| Knee Synovial Hypertrophy(X) | 13 (32.5) | 5 (11.1) | 0.016 | 7 (23.3) | 4 (11.1) | 0.185 | ||||

| Knee Synovial Effusion(X) | 18 (45) | 6 (13.3) | 0.001* | 14 (46.7) | 13 (36.1) | 0.385 | ||||

| Knee Power Doppler(X) | (32/42) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | (30/33) | 2 (6.67) | 2 (6.06) | 0.922 | ||

| Within the LC and WR Group, Changes in Musculoskeletal Imaging Results. | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Side | (n) | WR | (n) | LC | |||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | p | Baseline | Follow-up | p | |||||

| BMD | Total body | - | 30 | 1.216±0.142 | 1.215±0.143 | 0.837 | 36 | 1.224±0.106 | 1.219±0.104 | 0.068 |

| L1-L4 | - | 23 | 1.235±0.251 | 1.233±0.258 | 0.812 | 24 | 1.197±0.144 | 1.183±0.148 | 0.173 | |

| Femoral neck | Rt | 30 | 0.958±0.148 | 0.961±0.144 | 0.513 | 36 | 0.984±0.144 | 0.98±.143 | 0.463 | |

| Lt | 0.97±0.16 | 0.965±0.157 | 0.310 | 0.976±0.164 | 0.997±0.223 | 0.158 | ||||

| Total hip | Rt | 1.016±0.171 | 1.023±0.175 | 0.026 | 1.028±0.146 | 1.029±0.152 | 0.779 | |||

| Lt | 1.018±0.185 | 1.021±0.188 | 0.307 | 34 | 1.016±0.146 | 1.018±0.149 | 0.494 | |||

| TBC | Gynoid Region Fat (%) | 0.394 (0.355;0.454) | 0.382 (0.321;0.471) | 0.926 | 36 | 0.478 (0.392;0.548) | 0.482 (0.410;0.541) | 0.055 | ||

| Gynoid Tissue Fat (%) | 0.401 (0.363;0.464) | 0.382 (0.321;0.471) | 0.066 | 0.49 (0.402;0.557) | 0.482 (0.410;0.541) | 0.271 | ||||

| Gynoid Fat Mass (g) | 4576 (3682;6192) | 4564 (3583;6308) | 0.517 | 6176 (4231;7642) | 6238 (4599;7518) | 0.029 | ||||

| Gynoid Lean Mass (g) | 6751 (5664;8986) | 6601 (5705;8929) | 0.416 | 6235 (5589;7702) | 6147 (5509;7727) | 0.851 | ||||

| Android Region Fat (%) | 0.431 (0.371;0.501) | 0.415 (0.350;0.472) | 0.228 | 0.488 (0.425;0.562) | 0.489 (0.423;0.568) | 0.087 | ||||

| Android Region Fat Mass (g) | 2483 (1971;3334) | 2425 (1861;3219) | 0.428 | 3187 (2164;4618) | 3198 (2008;4857) | 0.307 | ||||

| Android Tissue Fat (%) | 0.435 (0.376;0.506) | 0.420 (0.356;0.478) | 0.229 | 0.493 (0.429;0.566) | 0.494 (0.429;0.571) | 0.102 | ||||

| Legs Tissue Fat (%) | 0.359 (0.293;0.43) | 0.334 (0.277;0.433) | 0.585 | 0.434 (0.347;0.522) | 0.446 (0.361;0.511) | 0.016 | ||||

| Legs Lean Mass (g) | 14615 (12927;19471) | 14680 (13170;19137) | 0.236 | 13673 (11646;17561) | 13394 (12181;16794) | 0.489 | ||||

| Total Lean Mass (g) | 45176 (39722;58679) | 45326 (39627;55925) | 0.089 | 41080 (37904;54043) | 40774 (37743;53367) | 0.441 | ||||

| Intra-Articular | Hand Synovial Hypertrophy | 2 (1;4) | 1.5 (0;3) | 0.123 | 2 (1;5) | 1 (0;3) | 0.012 | |||

| Hand Synovial Effusion | 0 (0;1) | 0 (0;1) | 0.702 | 0 (0;0) | 0 (0;0) | 0.139 | ||||

| Hand Power Doppler | 1.5 (0;4) | 1 (0;3) | 0.481 | 1 (0;2) | 0.5 (0;2) | 0.228 | ||||

| Knee Synovial Hypertrophy | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 0.687 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 1.000 | ||||

| Knee Synovial Effusion | 4 (50) | 4 (50) | 1.000 | 2 (15.4) | 11 (84.6) | 0.023 | ||||

| Knee Power Doppler | 26 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0.500 | 31 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0.500 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).