Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The State of the Art

1.2. The Ubiquity of Rossby Waves

1.3. The Climatic Impact of Quasi-Stationnary Rossby Waves

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Data

2.2. Wavelet Analysis

3. Results

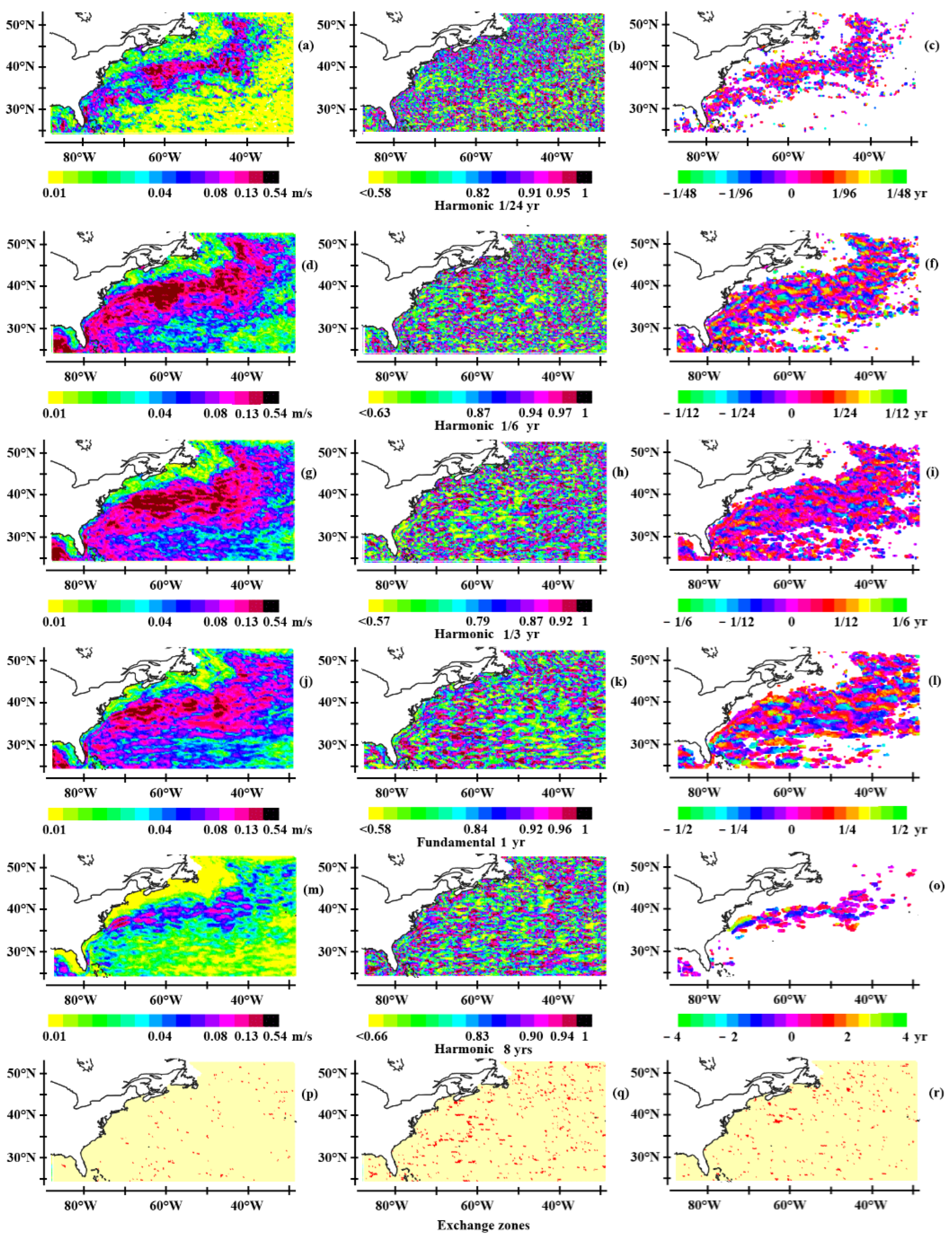

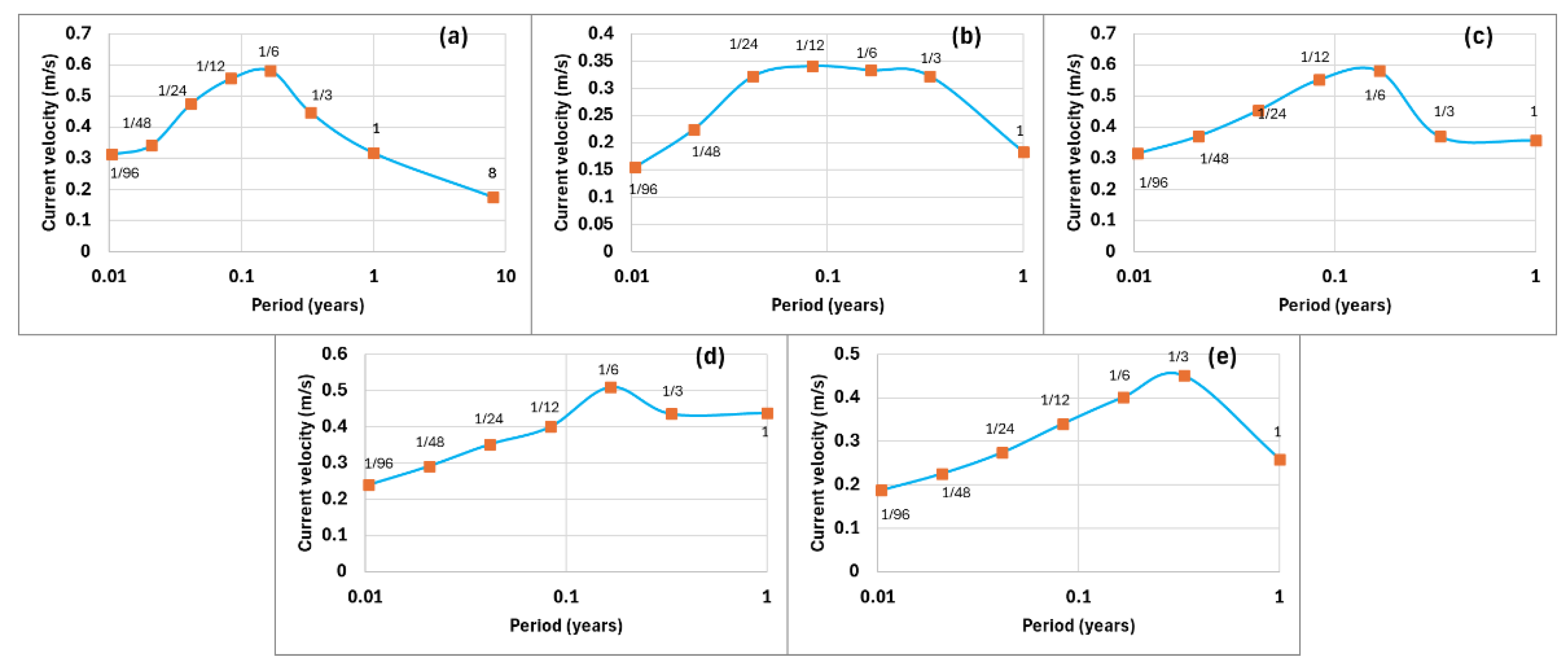

3.1. Observation of Oceanic Rossby Waves at Mid-Latitudes

3.2. Acceleration of the Modulated Geostrophic Current

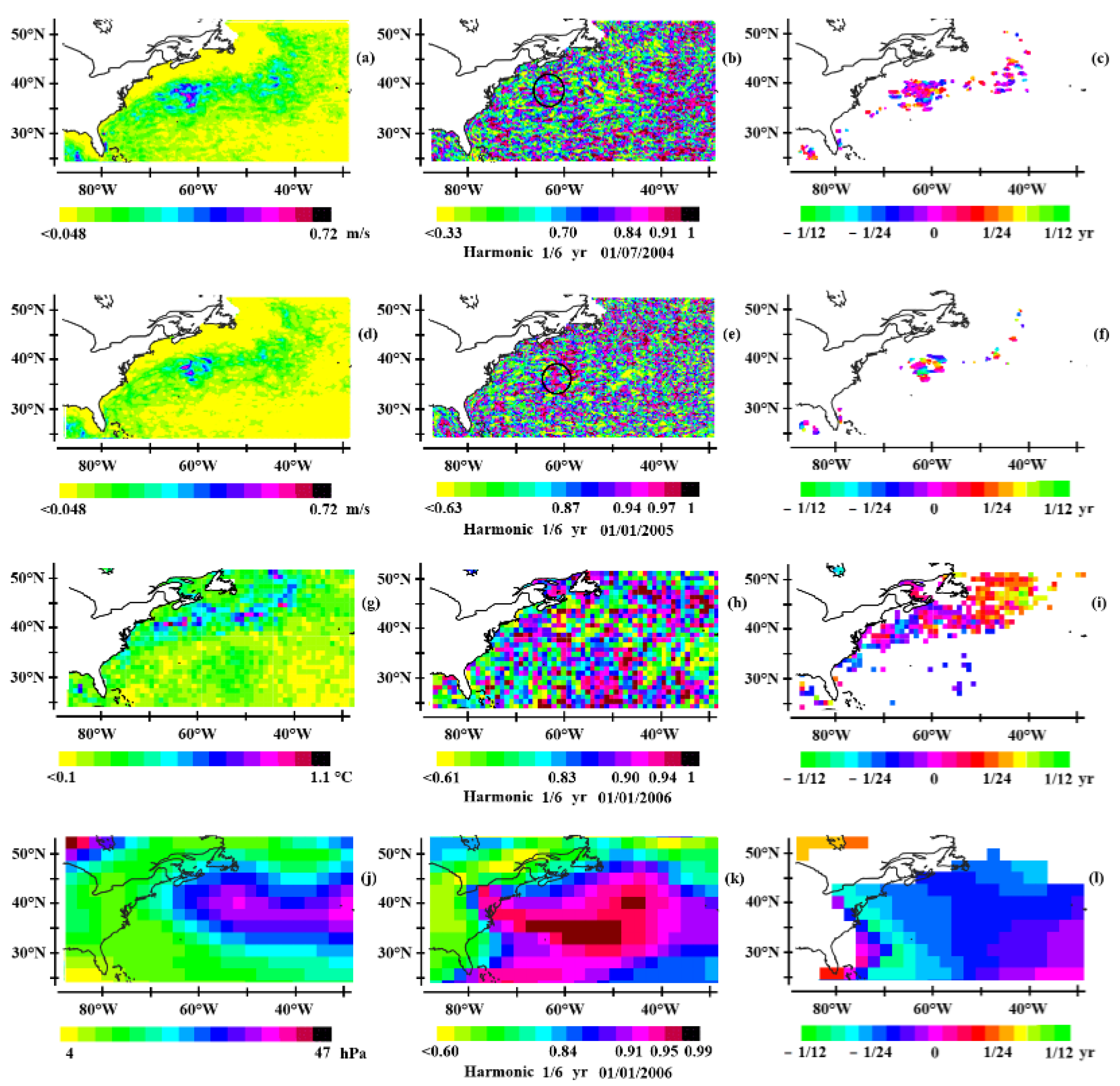

3.2.1. The North Atlantic

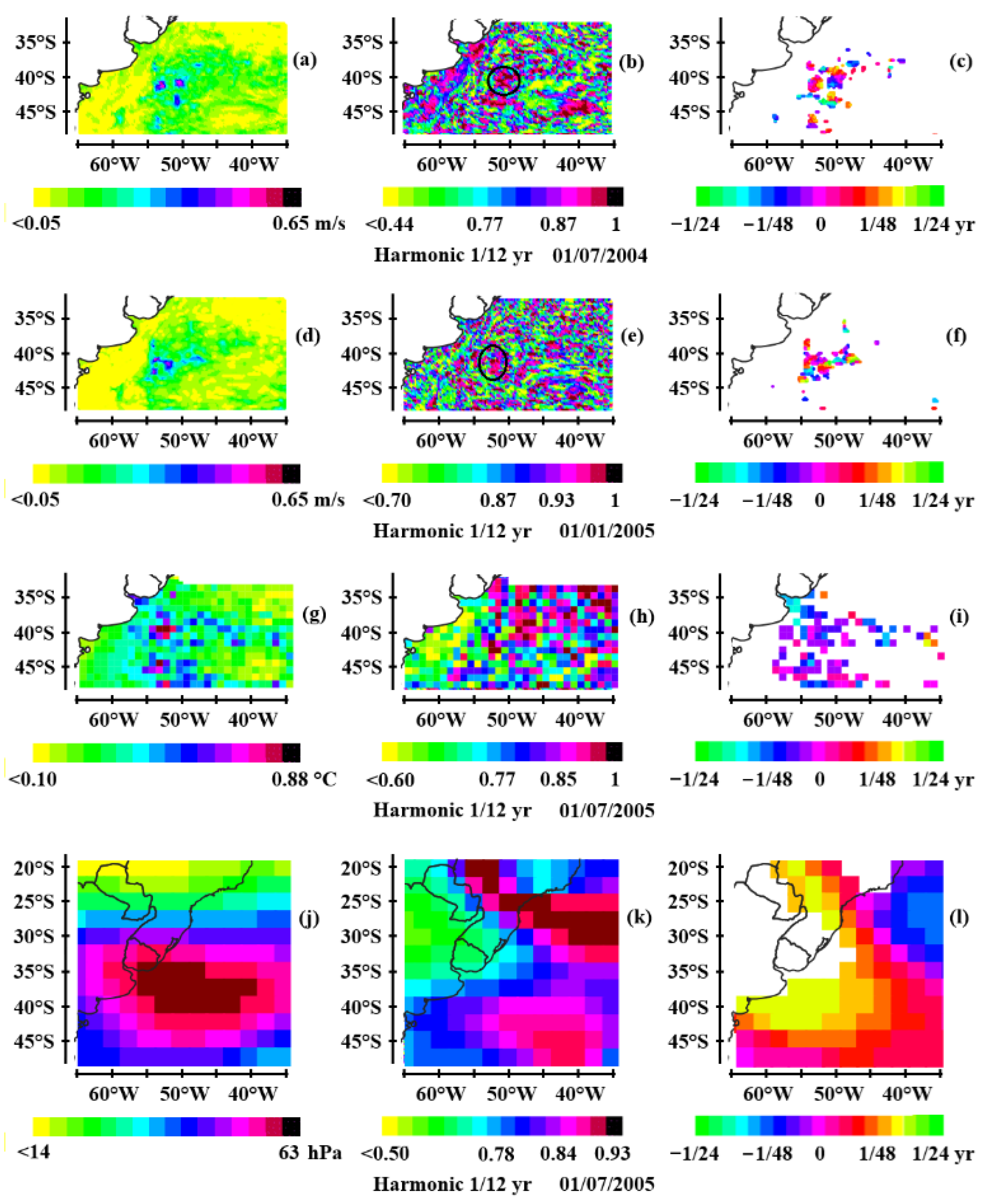

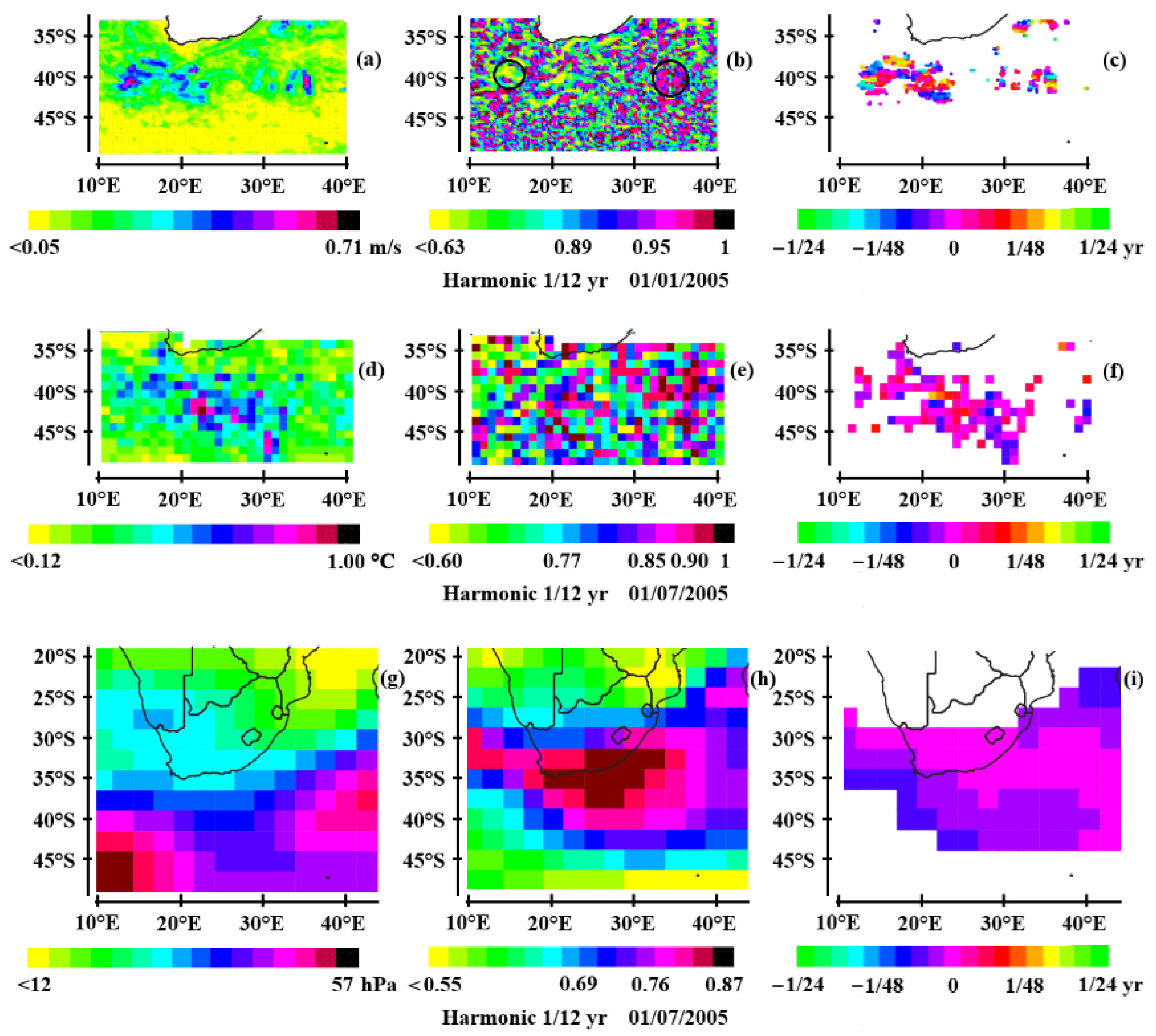

3.2.2. The South Atlantic

3.2.3. The Indian Ocean

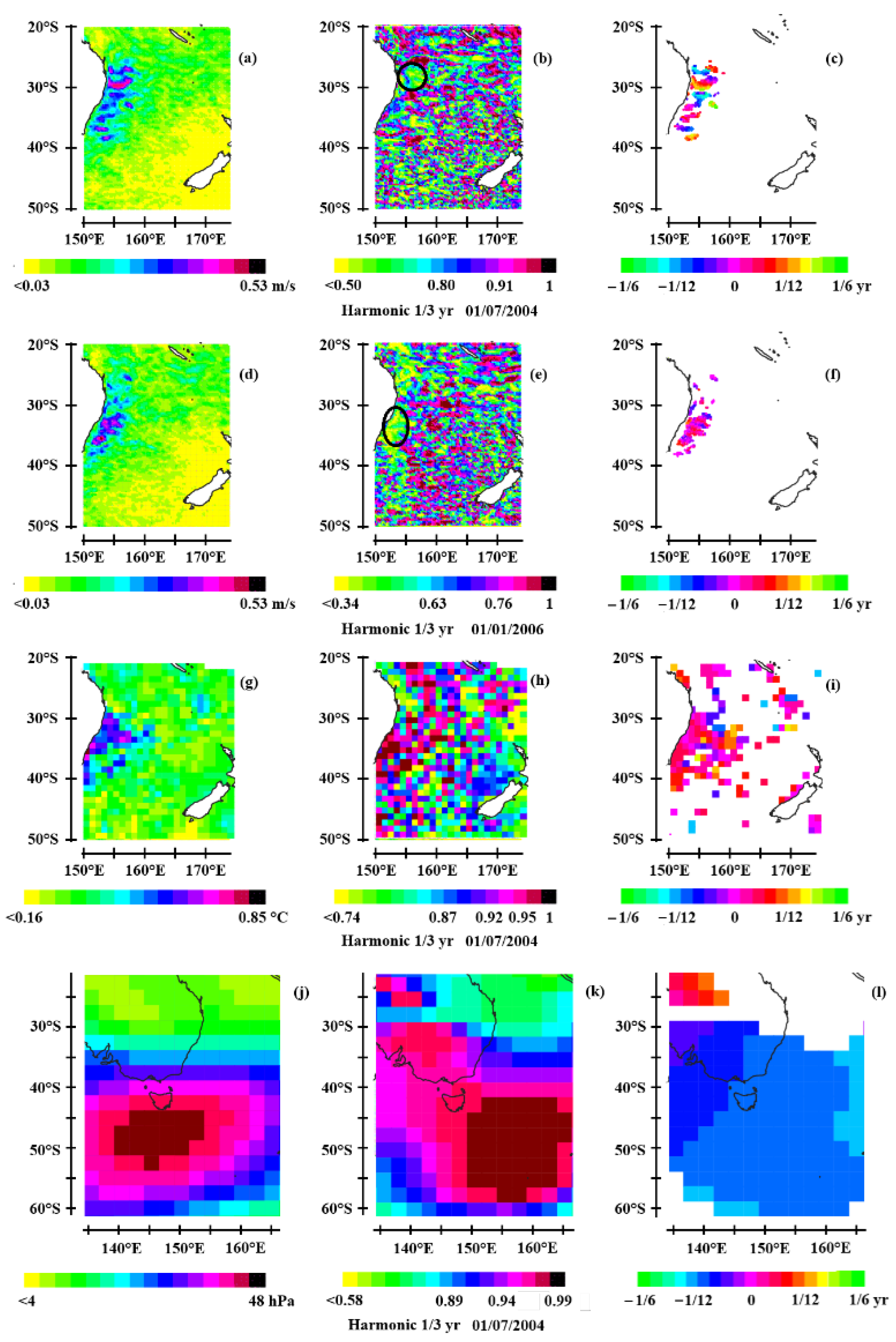

3.2.4. The South Pacific

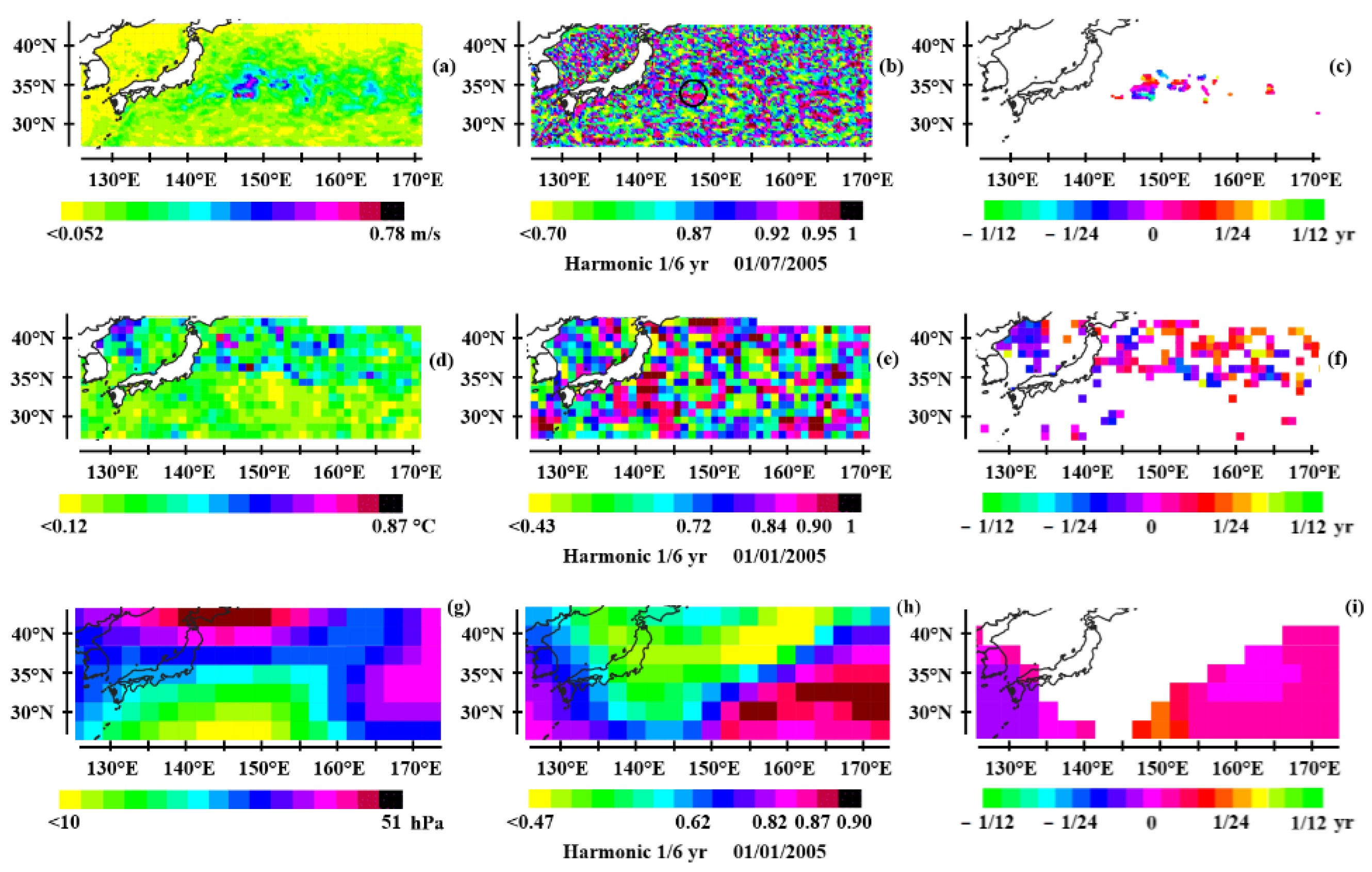

3.2.5. The North Pacific

3.3. Impact on Climate

3.3.1. Sea Surface Temperature

3.3.2. Geopotential Height at 500 hPa

4. Conclusions

- In the North and South Atlantic, the thermocline behaves as a resonant cavity with rigid boundaries at the edges of the western boundary currents, i.e. the Gulf Stream and the Brazil Current, traversed by first-baroclinic mode, first-meridional mode Rossby waves.

- In the Indian Ocean, the retroflection of the Agulhas Current south of the African continent causes resonance in two different ways west and east of the Cape of Good Hope: resonance of second-baroclinic mode Rossby waves in the first case, and first-baroclinic mode Rossby waves in the second.

- The resonant forcing of second-baroclinic mode Rossby waves is also observed in the East Australian Current as it flows along Australia. In the North Pacific, resonant forcing of first-baroclinic mode Rossby waves is observed along the Kuroshio, off the east coast of Japan.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kornhuber, K.; Petoukhov, V.; Petri, S.; Rahmstorf, S.; Coumou, D. Evidence for wave resonance as a key mechanism for generating high-amplitude quasi-stationary waves in boreal summer. Climate Dynamics 2017, 49, 1961–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.A.; Skific, N.; Vavrus, S.J. North American weather regimes are becoming more persistent: Is Arctic amplification a factor? Geophysical Research Letters 2018, 45, 11414–11422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mann, M.E.; Wehner, M.F.; Christiansen, S. Increased frequency of planetary wave resonance events over the past half-century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2504482122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Mann, M.E.; Wehner, M.F.; Rahmstorf, S.; Petri, S.; Christiansen, S.; Carrillo, J. Role of atmospheric resonance and land–atmosphere feedbacks as a precursor to the June 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome event. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2315330121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Syed Mubashshir; Röthlisberger, Matthias; Parker, Tess; Kornhuber, Kai; Romppainen-Martius, Olivia; Recurrent Rossby waves during Southeast Australian heatwaves and links to quasi-resonant amplification and atmospheric blocks. [CrossRef]

- Julian Krüger, Characteristic Jet Stream patterns related to European Heat Waves, Thesis, 29 February 2020, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, GEOMAR Helm-holtz-Zentrum für Ozeanforschung Kiel.

- Gill, A.E. Atmosphere-Ocean Dynamics; International Geophysics Series; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982; 662p.

- Pinault, J.L. A Review of the Role of the Oceanic Rossby Waves in Climate Variability. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault J-L, Resonant Forcing by Solar Declination of Rossby Waves at the Tropopause and Implications in Extreme Events, Precipitation, and Heat Waves—Part 1: Theory, Atmosphere 2024, 15, 608. [CrossRef]

- Kanamitsu, M.; Ebisuzaki, W.; Woollen, J.; Yang, S.-K.; Hnilo, J.J.; Fiorino, M.; Potter, G.L. NCEP-DOE AMIP-II Reanalysis (R-2). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 83, 1631–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily Sea Surface Temperature Is Provided by NOAA. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/sea-surface temperature-optimum-interpolation/v2.1/access/avhrr/ (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Reynolds, R.W.; Smith, T.M.; Liu, C.; Chelton, D.B.; Casey, K.S.; Schlax, M.G. Daily High-Resolution-Blended Analyses for Sea Surface Temperature. J. Clim. 2007, 20, 5473–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzon, V.; Smith, T.M.; Chin, T.M.; Liu, C.; Hankins, W. A long-term record of blended satellite and in situ sea-surface temperature for climate monitoring, modeling and environmental studies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2016, 8, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Liu, C.; Banzon, V.; Freeman, E.; Graham, G.; Hankins, B.; Smith, T.; Zhang, H.M. Improvements of the Daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (DOISST) Version v2.1. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 2923–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sea Level Anomaly and Geostrophic Currents, Multi-Mission, Global, Optimal Interpolation, Gridded, Provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Available online: https://coastwatch.noaa.gov/pub/socd/lsa/rads/sla/daily/nrt/ (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis, 1998 American Meteorological Society.

- Pinault, J.-L. The Moist Adiabat, Key of the Climate Response to Anthropogenic Forcing. Climate 2020, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinault, J.-L. Resonant Forcing by Solar Declination of Rossby Waves at the Tropopause and Implications in Extreme Precipitation Events and Heat Waves—Part 2: Case Studies, Projections in the Context of Climate Change. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).